Abstract

Examination of adipose tissue biology may provide important insight into mechanistic links for the observed association between higher body fat and risk of several types of cancer, in particular colorectal and breast cancer. We tested two different methods of obtaining adipose tissue from healthy individuals.

Methods

Ten overweight or obese (BMI 25–40 kg/m2), postmenopausal women were recruited. Two subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue samples were obtained per individual (i.e. right and left of lower abdominal region) using two distinct methods (Method A; 14 gauge needle with incision versus Method B; 16 gauge needle without incision). Gene expression was examined at the mRNA level for leptin, adiponectin, aromatase, IL-6 and TNF-α in flash frozen tissue and at the protein level for leptin, adiponectin, IL-6 and TNF-α following short term culture.

Results

Participants preferred biopsy Method A and few participants reported any of the usual minor side effects. Gene expression was detectable for leptin, adiponectin and aromatase, but was below detectable limits for IL-6 and TNF-α . For detectable genes, relative gene expression in adipose tissue obtained by Method A and B was similar for adiponectin (r=.64, p=0.06) and leptin (r=.80, p = 0.01), but not for aromatase (r=.37, p=0.34). Protein levels in tissue culture supernatant exhibited good intra-assay agreement (CV=1–10%), with less agreement for intra-individual (CV=17–29%) and reproducibility, following one freeze-thaw cycle, (CV > 14%).

Conclusion

Subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsies from healthy, overweight individuals provides adequate amounts of tissue for RNA extraction, gene expression and other possible uses.

Keywords: adipose tissue, inflammation, adipokines, gene expression, obesity, cancer

Introduction

Higher levels of physical activity and lower body weight or body fat are associated with a decreased risk of several types of cancer, in particular colorectal and breast cancer (1, 2). Possible mechanisms for reducing cancer risk via changes in body composition involve inflammatory factors, steroid hormones, insulin-like growth factors and insulin resistance (3–5). These mechanisms have been investigated to a limited degree in blood, yet even less so directly in adipose tissue.

Adipose tissue plays a critical role in energy homeostasis, contributing to the regulation of metabolism, energy intake, and fat storage (6). In addition to adipocytes, which account for most of adipose tissue mass, adipose tissue also contains pre-adipocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, leukocytes, and macrophages (7). Adipose tissue secretes adipokines (i.e. leptin, adiponectin and resistin), as well as cytokines (i.e. interleukin (IL)-1, -6, -10 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α )), that can act in an autocrine, paracrine, or endocrine manner to impact metabolic functions (8) and initiation and progression of cancer (9, 10). Adipose tissue is also important for the conversion of androgens to estrogens by aromatase, which provides a mechanistic basis for the associations between adiposity and risk of estrogen-related cancers (11, 12).

We are interested in examining the impact of lifestyle changes on adipose tissue biology to clarify the link between adipose tissue, cancer risk, exercise and diet. The effect of change in energy balance on adipose tissue biology has been primarily examined in the short-term, in response to consuming very-low calorie diets (13–16) and to a lesser degree in exercise interventions (17–19). Nonetheless, these studies provide intriguing initial evidence that such interventions may affect mRNA expression of cytokines and adipokines, particularly IL-6 and leptin (13–16). Subcutaneous biopsies have been used to examine adipose tissue biology in a number of fields, such as obesity (20–22), lipoatrophy with antirectroviral therapy in HIV infection (23, 24) and dietary fatty acid intake (25, 26). Typically samples are gathered either during an unrelated surgical procedure, which allows for collection of both visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue and greater yield (15, 21, 27, 28) or by needle biopsy, which is used with intervention or longitudinal analyses (13, 14, 16, 22, 23). Here we investigate the use of a minimally invasive biopsy technique in healthy volunteers to determine the appropriate analysis methods for adipose tissue that have relevance to cancer biomarker studies.

With this pilot study we aimed to (a) compare two subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsy methods for participant preference and sample yield, (b) examine mRNA expression of IL-6 (IL6), TNF-α (TNF), leptin (LEP), adiponectin (ADIPOQ) and aromatase (CYP19A1) and (c) develop tissue-culture methods to examine the levels of proteins of interest, namely leptin, adiponectin, IL-6 and TNF-α in supernatant. The results will inform methods that can be used to examine the effects of lifestyle or genetics on biomarkers of cancer risk related to adipose tissue biology.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Ten overweight and obese (BMI 25–40 kg/m2), postmenopausal women, aged 50–75 years, were recruited to participate in this pilot study from women who had been deemed ineligible (i.e. too physically active, time commitment) following screening for a large randomized-controlled trial of physical activity and/or diet and breast cancer biomarkers.

Biopsy method

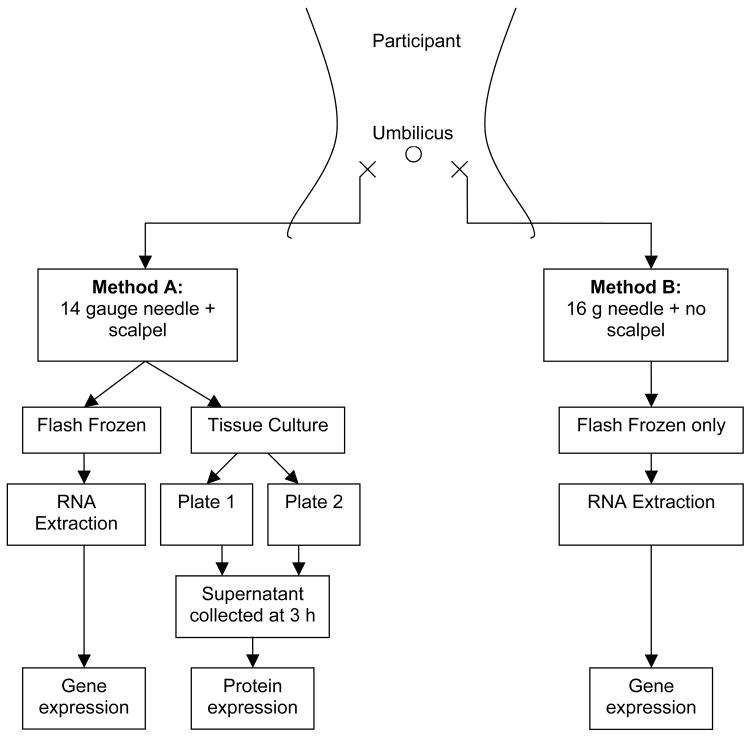

Participants completed an 8-hour fast prior to the biopsy procedure. Subcutaneous abdominal adipose samples were obtained by the same trained physician (KFS) from superficial abdominal adipose tissue. The biopsy methods and sample processing steps are outlined in Figure 1. A sample was collected from an area in the lower quadrant (10–12 cm from the umbilicus) by one method and repeated on the contralateral side in succession, using the second method. Which method (i.e. A or B) and location (i.e. right or left) was done first was alternated and recorded. Method A used a 14 gauge needle and required a <0.5 cm scalpel incision, while Method B used a 16 gauge needle without incision. In both cases, the Yale needle was attached to a 20 mL syringe filled with sterile saline and was passed through the subcutaneous fat several times while applying negative pressure. The collected adipose tissue was processed immediately following sampling. From Method A, approximately half the sample was flash frozen on dry ice, while the remainder was processed for tissue culture. From Method B, the entire sample was flash frozen on dry ice.

Figure 1.

Biopsy methods and sample processing

Subjects provided informed consent and the study was approved by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Institutional Review Board. Potential side effects were reviewed by participants and included: some discomfort, small risk of bleeding, mild bruising and a small risk of infection. Participants reported method preference, extent of side effects and any unanticipated symptoms in a follow-up phone call (7–10 days after procedure) by one of the investigators (KC). This scripted interview asked about the presence and extent of potential side effects and also biopsy method preference, namely the sample done on the right or left.

Tissue Yield

Tissue mass for RNA isolation was determined by weighing the tube containing the flash frozen tissue on an analytical balance and subtracting out the mass of the pre-weighed tube. Similarly, tissue mass for in vitro culture experiments was determined using an analytical balance to weigh the tissue culture plate containing the harvested and washed tissue immediately before culture and subtracting out the weight of the plate. The total yield per biopsy method was calculated by adding together the total net tissue mass for all aliquots of tissue obtained from that biopsy.

RNA analysis of gene expression

Total RNA was extracted from the flash frozen tissues using the Absolutely RNA miniprep kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and stored at −80°C. RNA was quantitated using the Ribogreen RNA Quantitation assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Expression of mRNA was determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) using the Taqman 1 step RT-PCR master mix and inventoried gene expression assays for IL-6 (IL6), TNF-α (TNF), leptin (LEP) adiponectin (ADIPOQ), aromatase (CYP19A1) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a housekeeping gene (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). GAPDH expression was measured as a housekeeping gene, for normalization across samples. 50 ng of RNA was loaded per well. Samples were batched together and run in triplicate on an ABI 7900HT sequence detection system. Relative expression levels were calculated using the ddCt method (Applied Biosystems).

Tissue culture

Adipose tissue for culture was immediately placed in10ml sterile PBS with 1% BSA after biopsy. Samples were incubated for 30–60 min on ice with occasional mixing to wash away blood and then centrifuged at 250xg for 5 min to pellet debris. In a sterile tissue culture hood, the upper floating layer of tissue was harvested with sterile forceps, split into two separate pre-weighed 24 well tissue culture plates and weighed on an analytical balance. An average of 140mg of tissue was cultured per well in sterile DMEM with 1% BSA. Culture conditions were normalized across samples by adjusting the amount of media added to obtain 100 mg adipose tissue/ml of media based on the net weight of the tissue. Cultures are incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 3 hours. Following incubation, supernatant is harvested in aliquots and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Protein analysis

Analysis of human adipocyte IL-6, TNF-α , leptin, and adiponectin protein expression was measured in the supernatant of the adipose tissue explant culture. Proteins were detected using the custom multiplex SearchLight ® Assay System (Pierce/Endogen, Woburn, MA). Samples from each culture were shipped on dry ice to the Searchlight Sample Testing Service, who performed the assays. This method of protein quantification is based on a traditional sandwich ELISA technique and integrates plate-based antibody arrays with chemiluminescent detection. All samples are run in duplicate and the assays are validated to ensure optimal sensitivity, specificity, linearity of dilution and dynamic range.

Statistical Analysis

Sample yield by biopsy method were compared with paired sample t-test and reported as means and standard deviation. Tissue culture protein expression was examined for agreement by determining coefficients of variations (CV). Intra-assay CV was calculated by comparing two aliquots harvested from one plate in the same assay run. Intra-individual CV was determined by comparing aliquots from each duplicate plate for each individual in the same assay run. A reproducibility CV was determined by repeating the analysis of supernatant samples following one freeze/thaw cycle and comparing results to the first run. Pearson correlations were used to examine the association between relative mRNA expression from two sites and also between protein levels and relative mRNA expression for a particular gene. Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 14 (SPSS Inc., Evanston, IL).

Results

Biopsy Method Comparison

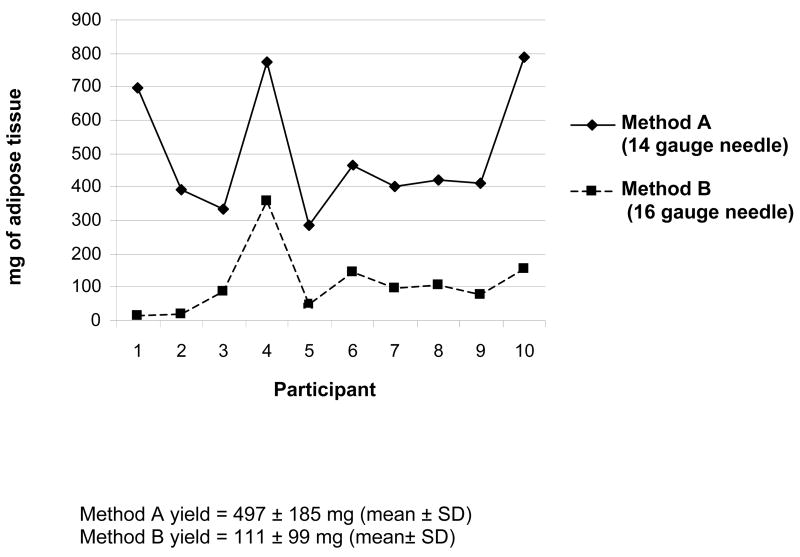

Participants were 60.4 ± 5.1 years and weighed 77.1 ± 7.9 kg (BMI 30.0 ± 4.9 kg/m2). The yield of adipose tissue is outlined in Figure 2 and mean yield was greater for Method A than Method B (497 ± 185 mg versus 111 ± 99 mg, p <0.001). Five participants preferred Method A, while three preferred Method B and two had no preference. At the follow up phone call, few participants reported experiencing any side effects; specifically, minor bleeding from the biopsy site resolving within 12 hours (n=1; Method A), moderate bruising (up to 10 cm diameter) resolving within 10–14 days (n=1; Method A) or discomfort with contact to the biopsy site resolving within 2–3 days (n=1; Method B). These three participants received an additional call 7 days later to follow up on their symptoms and reported that these side effects had resolved. There was no pattern in participant preference or sample yield across the duration of the pilot (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Tissue yield per participant by biopsy method

Gene expression

RNA yield per mg of tissue was equivalent for Method A and B (14.2 ± 7.8 versus 16.2 ± 8.3 ng RNA per mg of tissue, respectively, p=0.95) and RNA quality was good for both methods (data not shown). Gene expression data was not available for one participant due to GAPDH failure. Gene expression was detectable for ADIPOQ, LEP and CYP 19A1, but below detectable limits for IL6 and TNF (Table 1). For detectable genes, relative gene expression in adipose tissue obtained by Method A and B (i.e. different abdominal sites) was similar for ADIPOQ (r=.64, p=0.06) and LEP (r=.80, p = 0.01), but not for CYP 19A1 (r=.37, p=0.34).

Table 1.

Gene and protein expression from tissue culture (mean ± SD), including agreement in gene expression between the two methods and percent coefficients of variation (CV) for tissue culture supernatant protein expression.

| Gene Expression (N=9) | Protein Secretion (N=10) for Method A only | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative to GAPDH | Coefficient of variation (CV)1 | |||||

| Method A | Method B | pg/ml | Intra-assay | Intra-individual | Reproducibility | |

| Adiponectin | 1.15±0.5 | 1.28±0.6 | 12670±9472 | 3% | 18% | 50% |

| Leptin | 1.38±0.6 | 1.23±0.5 | 201±85 | 1% | 17% | 14% |

| IL-6 | NA | NA | 14.3±15.2 | 10% | 29% | 103% |

| Aromatase | 3.48±2.7 | 5.29±7.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Intra-assay – duplicated samples in a single assay run (variability due to multiplex assay); Intra-individual - splitting one tissue sample into two equal amounts for culture and comparing samples in a single assay run (variability between two tissue culture wells from the same biopsy sample); Reproducibility - repeating samples following one freeze/thaw cycle (variability due to freeze-thaw cycle).

Protein Production

Table 1 also shows the protein-expression results from the tissue culture and CVs. TNF-α was below the level of quantitation in 7 of 10 samples; thus results are not reported. Searchlight also provided assay precision data for the assay. For adiponectin, leptin and IL-6, the intra-assay CV was 9.4, 8.6 and 11.7 percent, respectively and the inter-assay CV was 10.5, 16.6 and 10.4 percent, respectively. Agreement between relative gene expression and protein levels was examined for leptin (r=−.30, p=0.44) and adiponectin (r=−.40, p=0.29), where both gene expression and protein levels were available.

Discussion

Subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsies are feasible in a population of overweight, postmenopausal women who are interested in lifestyle intervention research on breast cancer biomarkers. We found that not only did participants agreed to the procedure, but they also preferred the method which we initially viewed as more invasive (Method A), and overall reported few side effects. In addition, Method A is advantageous from the standpoint of providing greater amount of tissues for analyses. The skill and experience of the individual obtaining the biopsy could play a role in both participant preference and sample yield. All of our samples were collected by one individual and we did not observe a trend across time for preference and sample yield. We acknowledge that there are a number of other possible technique comparisons that could have been done, such as additional biopsies at other sites, use of a larger cannulae or use of a larger incision with a punch biopsy to gather more tissue. However, our main goal was to develop a technique that was acceptable to participants in future intervention trials that otherwise do not include invasive procedures to maximize participant retention.

We chose to examine genes that have relevance for both energy balance and cancer risk, specifically the role of adipose tissue in energy signaling (i.e. leptin and adiponectin), aromatization to form estrogens (i.e. aromatase) and systemic inflammation (i.e. IL-6, TNF-α ). Gene expression was detectable in adipose tissue samples for some (i.e. ADIPOQ, LEP, CYP 19A1) but not all genes of interest (i.e. IL6 and TNF). There was good agreement in gene expression from two different subcutaneous abdominal sites within individuals for ADIPOQ, LEP, but not for CYP 19A1, which suggests that examining relative gene expression for certain genes using mRNA may be a feasible way to monitor changes over time in adipose tissue biology in an intervention study. However, our findings are inconsistent with several studies investigating adipose tissue gene expression, where mRNA for both IL-6 and TNF-α , has been quantified (17, 18, 29, 30) using similar methods for both collection, which yielded similar amounts of adipose tissue, and analysis. Further optimization of our detection methods may improve sensitivity, allowing measurement of these cytokines. The issue of selecting appropriate house keeping genes for quantification of RNA expression in human adipose tissue is receiving attention (31). In addition, Dolinkova et al. (28), recently examined the differences in gene expression profile of obese versus normal weight subjects for both visceral versus subcutaneous adipose tissue and whole adipose tissue versus isolated adipocytes. This study provides a list of candidate gene targets for future studies examining the role of body composition and lifestyle interventions on adipose tissue biology.

Several other groups have used adipose tissue collected by needle aspiration biopsy to analyze the concentration of secreted proteins such as leptin, adiponectin or IL-6(32–35). It has been suggested that more representative data are collected with a short incubation time and minimal manipulation of the adipose sample, especially for IL-6 and TNF- α (32). We sought to assess whether this is a feasible approach that could yield meaningful results. There was good agreement in the protein levels of duplicate supernatant samples run in the same assay, however, TNF-α was not at detectable levels in the majority of samples using a multiplex assay. When we split the sample into equal amounts for tissue culture the intra-individual CV was high, suggesting that we may have not divided the tissue evenly between the two replicate cultures. This could have resulted from inaccurate weighing or heterogeneity of the tissue, where protein-secreting cells were not evenly distributed between the two samples. These findings suggest that measuring the concentration of proteins secreted from explanted tissue is highly variable, and that such data should be interpreted with great caution. In addition, variation in our measure of reproducability was high when sample analysis was repeated following one freeze-thaw cycle, which suggests that sample handling is an important variable to consider when examining cytokines and adipokines. Comparison of results obtained from samples run at different times should be done with caution and ideally samples to be directly compared should be run in parallel.

There was no agreement between relative gene expression and protein levels for leptin and adiponectin, the two biomarkers where both levels were available. This indicates that the protein levels in tissue culture are not closely correlated with the mRNA levels present at the time of tissue harvest. This is not necessarily surprising as the former reflects protein secretion accumulated over time while the latter represents a steady state measurement. In addition, there is evidence for post transcriptional regulation of both of these genes (36–38), suggesting that measuring both mRNA and protein may provide non-redundant information about the expression and regulation of these genes.

Examining whole tissue protein levels and mRNA expression does not account for the heterogeneous cellular composition of adipose tissue. The number of macrophages increases in adipose tissue with overall body fat mass (39), which appear to be the main source of TNF-α and IL-6 (7). Therefore, quantification of macrophage content may be a proxy measure of altered adipose biology in intervention studies. Further processing (i.e. collagenase digestion) to separate out the different constituents of adipose tissue has also been used (32), however are time and labor intensive.

In the future we plan to examine RNA expression following 6-months of lifestyle change (either dietary weight loss, aerobic exercise or combined diet and exercise and control) following exploratory microarray analysis. Currently, we have refined our sample collection process slightly to reduce possible contamination of blood in the adipose sample by first placing the sample on a sterile absorbent non-stick tefla pad. The serous fluid is trapped in the pad and the adipose sample is then processed.

In summary, our pilot study suggests subcutaneous adipose tissue biopsies from healthy, overweight individuals who were recruited to cancer prevention studies provides adequate tissue for RNA extraction, gene expression analysis, and other possible uses. However, at this time we question the utility of examining protein expression derived from tissue culture due to the high variability observed.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Drs. Scott Weigle and Richard Pratley for their advice on the sampling method and to the study participants for their time. This study was funded through the National Cancer Institute R01 CA 77572-01 and U54 CA116847 Transdisciplinary Research on Energetics and Cancer (TREC) Pilot Project. KL Campbell is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship.

References

- 1.Vainio H, Bianchini F, editors. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. Weight Control and Physical Activity. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedenreich CM. Review of anthropometric factors and breast cancer risk. European J Cancer Prev. 2001;10:15–32. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200102000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedenreich CM, Cust AE. Physical Activity and Breast Cancer Risk: Impact of Timing, Type and Dose of Activity and Population Sub-group Effects. Br J Sports Med. 2008 doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.029132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McTiernan A, Ulrich C, Slate S, Potter J. Physical activity and cancer etiology: associations and mechanisms. Cancer Causes & Control. 1998;9:487–509. doi: 10.1023/a:1008853601471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers CJ, Colbert LH, Greiner JW, Perkins SN, Hursting SD. Physical activity and cancer prevention: pathways and targets for intervention. Sports Med. 2008;38:271–96. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. Adipocytes as regulators of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Nature. 2006;444:847–53. doi: 10.1038/nature05483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Adipocytokines: mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:772–83. doi: 10.1038/nri1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Obesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:461S–465S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.461S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vona-Davis L, Rose DP. Adipokines as endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine factors in breast cancer risk and progression. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2007;14:189–206. doi: 10.1677/ERC-06-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hursting SD, Nunez NP, Varticovski L, Vinson C. The obesity-cancer link: lessons learned from a fatless mouse. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2391–3. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein L. Epidemiology of endocrine-related risk factors for breast cancer. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2002;7:3–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1015714305420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaaks R, Lukanova A, Kurzer MS. Obesity, endogenous hormones, and endometrial cancer risk: a synthetic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:1531–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arvidsson E, Viguerie N, Andersson I, et al. Effects of different hypocaloric diets on protein secretion from adipose tissue of obese women. Diabetes. 2004;53:1966–71. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bastard JP, Hainque B, Dusserre E, et al. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma, leptin and tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA expression during very low calorie diet in subcutaneous adipose tissue in obese women. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 1999;15:92–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-7560(199903/04)15:2<92::aid-dmrr21>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clement K, Viguerie N, Poitou C, et al. Weight loss regulates inflammation-related genes in white adipose tissue of obese subjects. Faseb J. 2004;18:1657–69. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2204com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viguerie N, Vidal H, Arner P, et al. Adipose tissue gene expression in obese subjects during low-fat and high-fat hypocaloric diets. Diabetologia. 2005;48:123–31. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1618-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruun JM, Helge JW, Richelsen B, Stallknecht B. Diet and exercise reduce low-grade inflammation and macrophage infiltration in adipose tissue but not in skeletal muscle in severely obese subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E961–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00506.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klimcakova E, Polak J, Moro C, et al. Dynamic strength training improves insulin sensitivity without altering plasma levels and gene expression of adipokines in subcutaneous adipose tissue in obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:5107–12. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polak J, Moro C, Klimcakova E, et al. Dynamic strength training improves insulin sensitivity and functional balance between adrenergic alpha 2A and beta pathways in subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese subjects. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2631–40. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim MJ, Maachi M, Debard C, et al. Increased adiponectin receptor-1 expression in adipose tissue of impaired glucose-tolerant obese subjects during weight loss. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155:161–5. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacLaren R, Cui W, Simard S, Cianflone K. Influence of obesity and insulin sensitivity on insulin signaling genes in human omental and subcutaneous adipose tissue. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:308–23. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700199-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maachi M, Pieroni L, Bruckert E, et al. Systemic low-grade inflammation is related to both circulating and adipose tissue TNFalpha, leptin and IL-6 levels in obese women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:993–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kratz M, Purnell JQ, Breen PA, et al. Reduced adipogenic gene expression in thigh adipose tissue precedes human immunodeficiency virus-associated lipoatrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:959–66. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bastard JP, Caron M, Vidal H, et al. Association between altered expression of adipogenic factor SREBP1 in lipoatrophic adipose tissue from HIV-1-infected patients and abnormal adipocyte differentiation and insulin resistance. Lancet. 2002;359:1026–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kark JD, Kaufmann NA, Binka F, Goldberger N, Berry EM. Adipose tissue n-6 fatty acids and acute myocardial infarction in a population consuming a diet high in polyunsaturated fatty acids. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:796–802. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.4.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baylin A, Kabagambe EK, Siles X, Campos H. Adipose tissue biomarkers of fatty acid intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:750–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.4.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker GE, Verti B, Marzullo P, et al. Deep subcutaneous adipose tissue: a distinct abdominal adipose depot. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:1933–43. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolinkova M, Dostalova I, Lacinova Z, et al. The endocrine profile of subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue of obese patients. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastard JP, Jardel C, Bruckert E, et al. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 are reduced in serum and subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese women after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3338–42. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polak J, Klimcakova E, Moro C, et al. Effect of aerobic training on plasma levels and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue gene expression of adiponectin, leptin, interleukin 6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha in obese women. Metabolism. 2006;55:1375–81. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Catalan V, Gomez-Ambrosi J, Rotellar F, et al. Validation of endogenous control genes in human adipose tissue: relevance to obesity and obesity-associated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39:495–500. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-982502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fain JN, Madan AK. Regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) release by explants of human visceral adipose tissue. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:1299–307. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fried SK, Bunkin DA, Greenberg AS. Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese subjects release interleukin-6: depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:847–50. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kern PA, Ranganathan S, Li C, Wood L, Ranganathan G. Adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 expression in human obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;280:E745–51. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.5.E745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kern PA, Di Gregorio GB, Lu T, Rassouli N, Ranganathan G. Adiponectin expression from human adipose tissue: relation to obesity, insulin resistance, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression. Diabetes. 2003;52:1779–85. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee MJ, Yang RZ, Gong DW, Fried SK. Feeding and insulin increase leptin translation. Importance of the leptin mRNA untranslated regions. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:72–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609518200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee MJ, Fried SK. Multilevel regulation of leptin storage, turnover, and secretion by feeding and insulin in rat adipose tissue. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1984–93. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600065-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clasen R, Schupp M, Foryst-Ludwig A, et al. PPARgamma-activating angiotensin type-1 receptor blockers induce adiponectin. Hypertension. 2005;46:137–43. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000168046.19884.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cancello R, Henegar C, Viguerie N, et al. Reduction of macrophage infiltration and chemoattractant gene expression changes in white adipose tissue of morbidly obese subjects after surgery-induced weight loss. Diabetes. 2005;54:2277–2286. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]