Abstract

Objective

Little is known about whether economic crises widen health inequalities. Japan experienced more than 10 years of economic recession beginning in the 1990s. The question of whether socioeconomic-based inequality in self-rated health widened after the economic crisis was examined.

Design, setting and participants

Repeated cross-sectional survey design. Two pooled datasets from 1986 and 1989 and from 1998 and 2001 were analysed separately, and temporal change was examined. The study took place in Japan among the working-age population (20–60 years old). The two surveys consisted of 168 801 and 150 016 people, respectively, with about an 80% response rate.

Results

The absolute percentages of people reporting poor health declined across all socioeconomic statuses following the crisis. However, after controlling for confounding factors, the odds ratio (OR) for poor self-rated health (95% confidence intervals) among middle-class non-manual workers (clerical/sales/service workers) compared with the highest class workers (managers/administrators) was 1.02 (0.92 to 1.14) before the crisis but increased to 1.14 (1.02 to 1.29) after the crisis (p for temporal change = 0.02). The association was stronger among males. The adjusted ORs among professional workers and young female homemakers also marginally increased over time. Unemployed people were twice as likely to report poor health compared with the highest class workers throughout the period. Self-rated health of people with middle to higher incomes deteriorated in relative terms following the crisis compared with that of lower income people.

Conclusions

Self-rated health improved in absolute terms for all occupational groups even after the economic recession. However, the relative disparity increased between the top and middle occupational groups in men.

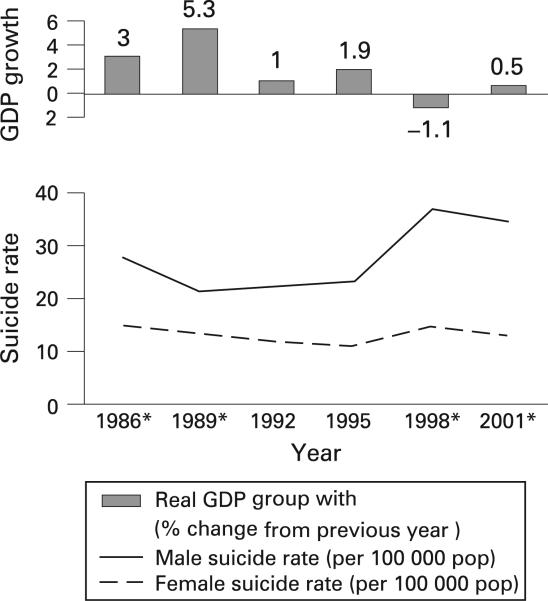

Japan has been a focus of frequent attention because of its achievement in population health as well as its egalitarian social security system including universal healthcare coverage and mandatory pension system since the 1960s.1 2 However, the country currently has serious concerns about rising inequality. In the early 1990s, Japan experienced an economic crisis, the so-called collapse of the bubble economy, which was followed by more than a decade of economic recession. Economists argue that this recession is linked to Japan's recent increase in socioeconomic inequality.3 In 1998, Japan's economy encountered the first negative growth since World War II. In the same year, the rate of suicide rose sharply (age-adjusted suicide mortality per 100 000 population rose from 18.8 in 1997 to 25.2 in 1998) and has remained at record high levels since. This suicide “epidemic” has been specifically shown in working-age males (fig 1).4 It is believed that the epidemic is due to rapid changes in industrial structure and working environments following the economic recession.5 6 These rapid changes may also have adversely affected working-age males’ lifestyle. A national survey reported that the prevalence of coronary risk factors has risen in this population during the recession.7–9

Figure 1.

Economic growth and suicide ratio for 1986–2001. *The years of data used in this study. Japan's economic recession began in the early 1990s and, in 1998, the country experienced the first negative growth after World War II when the male suicide rate increased sharply (a 40% increase over the previous year).

The 1997–8 Asian financial crisis led to a dramatic increase in suicide deaths among Korean males aged 35–64 years and widened education-based health inequalities, whereas transport accident deaths decreased because of reduced traffic as a result of skyrocketing oil prices.10 11 The crisis also affected other Asian countries.12 Similar studies have also been conducted in Europe.13 14 Studies in Britain and in Spain suggest an adverse impact of economic crises on health inequalities, but a study in Finland (which has stronger safety nets) reported rather smaller health disparities following a crisis.15

In Japan, an ecological study indicated that inequalities in mortality narrowed until 1995 but widened thereafter, coinciding with the economic crisis.16 However, convincing evidence based on individual-level analysis is still lacking.

We hypothesised that Japan's socioeconomic disparity in health widened after the economic recession, and that working-age males—the main target of corporate restructuring within a sluggish economy—were especially vulnerable to ill-health due to the crisis. In this study, we examine these hypotheses by comparing the cross-sectional association of perceived health with occupation or income within two datasets before and after the economic crisis.

METHODS

Data source

Data on perceived health status, occupation, income and demographic factors were derived from the 1986, 1989, 1998 and 2001 Comprehensive Survey of the Living Conditions of People on Health and Welfare (CSLC) conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. This survey interviewed all household members within census tracts that were randomly selected from all prefectures in the nation. For example, the 2001 survey was conducted across 5240 census tracts including 247 278 households (response rate of 87.4%), of which 31 871 households were randomly selected and surveyed regarding income and savings (response rate of 79.5%).

To increase statistical power, we pooled data from 1986 and 1989 for analysis, as well as data from 1998 and 2001. The two periods are distinct in terms of economic growth, corresponding to the periods before and after the economic recession (fig 1). Because we focused on the working-age population, individuals aged between 20 and 60 years were used. Thus, a total of 168 801 and 150 016 respondents who completed the income and savings survey in the 1998/2001 and 1986/1989 data, respectively, were used for analysis.

Measurements

The CSLC elicited respondents’ perceived health with the single item: “What is your current health status: excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” From this question, we created a dichotomous outcome measure with poor perceived health if the respondent answered fair or poor.

We used occupation and income as socioeconomic status (SES) measures. Following recent studies, we categorised a broad range of 14 occupations, compatible with the classification by ISCO-88,17 as follows: (1) managerial or administrative workers; (2) professional workers, including professional and technical workers; (3) middle-class non-manual workers, including clerical, sales and service workers; (4) manual workers, including labourers, security officers and traffic, agricultural, forestry or fishery workers; and (5) other paid workers. We also considered economically inactive persons: (6) homemakers and (7) the unemployed.18 19 Annual household income before tax including benefits and inheritances adjusted for household size (equivalence elasticity = 0.5) was used. To maintain comparability with other studies, we divided the subjects equally into deciles of income in each survey.20–23

Demographic variables included age, gender and marital status. Marital status was categorised as married, never married, separated or divorced. We did not include behavioural risk factors such as smoking, alcohol drinking, exercise habits and health check-ups when modelling the association between SES and perceived health in order not to overadjust because we considered these variables as potential mediating variables.24

Statistical analysis

First, we calculated the absolute percentages of people reporting poor health according to SES, adjusted for sociodemographic factors. We then estimated the odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence intervals (CI) of reporting poor health among occupational classes using the highest class occupation as reference. To address the potential clustering of the data arising from the stratified sampling strategy, we used a multivariate generalised estimating equation with a logit link function (PROC GENMOD, the SAS statistical package version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). Census tracts were selected as cluster units (up to 392 people per cluster). Next, we created models separately for pooled data in 1986/1989 and 1998/2001. Interaction analysis tested whether the SES–health association changed significantly over time. Finally, we stratified the sample by gender as well as two age groups of 20–39 years and 40–60 years.18 20 In addition, the relative index of inequality (RII) for poor health was calculated across income deciles. The RII can be interpreted as the relative rate of reporting poor health for the hypothetically poorest compared with the hypothetically richest person in the population, assuming a linear association between income and self-rated health.25 All p values are two-tailed.

RESULTS

Descriptive data showed that more women reported poor health than men (11.4% vs. 9.4% in 1986/1989 and 10.9% vs. 8.9% in 1998/2001), as did the 40- to 60-year-old age group compared with the 20- to 39-year-old group (13.0% vs. 7.6% and 11.5% vs. 7.9%). There were no male homemakers in 1986/1989 and only 63 in 1998/2001. The prevalence of poor perceived health varied by marital status (range 7.2% to 17.3%). In the 1986/1989 data, 10.4% reported fair or poor health, which dropped to 9.9% in the 1998/2001 data (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the subjects in pooled data from 1986/1989 and 1998/2001; CSLC, Japan

| 1986/1989 |

1998/2001 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Number (%) | Fair/poor health (%) | Number (%) | Fair/poor health (%) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 20–39 | 80 966 (48.0) | 7.6 | 68 072 (45.4) | 7.9 | ||

| 40–60 | 87 835 (52.0) | 13.0 | 81 944 (54.6) | 11.5 | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 82 612 (48.9) | 9.4 | 74 033 (49.4) | 8.9 | ||

| Female | 86 189 (51.1) | 11.4 | 75 983 (50.7) | 10.9 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 127 447 (75.5) | 10.8 | 100 855 (67.2) | 10.4 | ||

| Never married | 33 696 (20.0) | 7.2 | 41 153 (27.4) | 7.9 | ||

| Separated | 3683 (2.2) | 16.8 | 2551 (1.7) | 12.8 | ||

| Divorced | 3963 (2.4) | 17.3 | 5439 (3.6) | 14.7 | ||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Managerial/administrative | 5601 (3.4) | 9.4 | 7097 (5.0) | 8.6 | ||

| Professional | 14 874 (9.0) | 9.0 | 21 150 (14.8) | 9.0 | ||

| Clerical/sales/service | 51 145 (30.9) | 8.9 | 45 261 (31.6) | 9.2 | ||

| Manual | 47 458 (28.7) | 9.8 | 32 022 (22.3) | 8.8 | ||

| Other paid job | 1733 (1.1) | 11.5 | 2358 (1.6) | 10.2 | ||

| Homemaker | 34 565 (20.9) | 12.5 | 24 292 (16.9) | 12.3 | ||

| Unemployed | 10 267 (6.2) | 16.5 | 11 189 (7.8) | 12.6 | ||

| Household income* (median in each year, 10 000 yen) | ||||||

| Decile 1 (lowest) | 87.7 | 94.0 | 14.5 | 116.0 | 99.3 | 12.8 |

| Decile 2 | 134.4 | 149.8 | 11.9 | 196.3 | 173.1 | 11.4 |

| Decile 3 | 171.0 | 189.6 | 10.5 | 250.4 | 227.5 | 10.2 |

| Decile 4 | 202.1 | 225.0 | 9.9 | 300.0 | 276.0 | 9.4 |

| Decile 5 | 234.3 | 260.0 | 10.1 | 352.2 | 325.0 | 9.6 |

| Decile 6 | 268.3 | 300.0 | 9.8 | 404.5 | 375.3 | 8.8 |

| Decile 7 | 305.5 | 345.5 | 9.6 | 466.5 | 434.7 | 9.4 |

| Decile 8 | 355.5 | 403.4 | 9.0 | 546.2 | 507.5 | 9.0 |

| Decile 9 | 431.5 | 489.9 | 9.6 | 658.0 | 612.0 | 9.6 |

| Decile 10 | 431.5 | 489.9 | 9.4 | 911.0 | 851.4 | 9.0 |

| Self-rated health | ||||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 148 295 (89.6) | 128 024 (90.1) | ||||

| Fair/poor | 17 199 (10.4) | 14 062 (9.9) | ||||

Adjusted for household size with equivalence elasticity = 0.5.

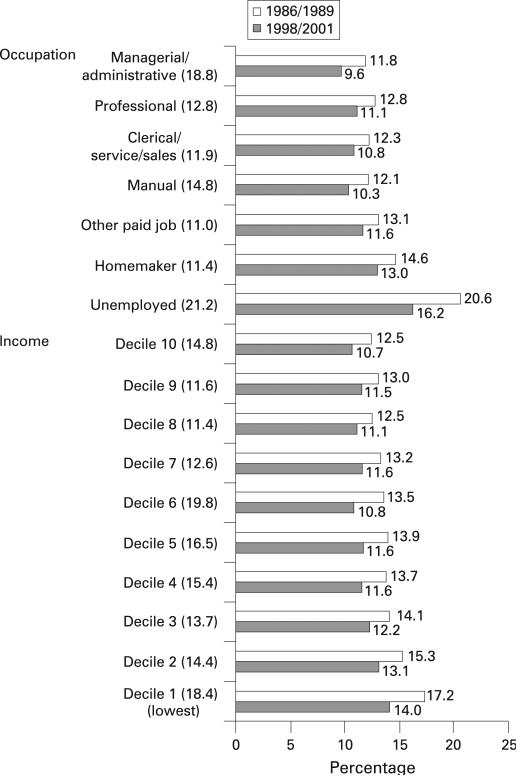

Occupation

After the crisis, the absolute percentages of people reporting poor health adjusted for sociodemographic factors declined across all SES categories. The reductions were largest among the unemployed (–21.2%) followed by managers or administrators (–18.8%) (fig 2).

Figure 2.

Adjusted percentages in reporting fair or poor health by socioeconomic position before (1986/1989) and after (1998/2001) the economic crisis and its percentage reduction (in parenthesis); CSLC, Japan. Percentages are adjusted for age, gender, marital status, survey year and either income or occupation.

Multivariate analysis showed no statistically significant associations between occupational status and self-rated health among economically active people before the economic crisis. However, after the crisis, middle-class non-manual workers (ie clerical, service and sales workers) were significantly more likely to report poor health: adjusted OR (95% CI) of reporting poor health compared with the highest class workers (ie managerial and administrative workers) increased from 1.02 (0.92 to 1.14) to 1.14 (1.02 to 1.29) (p for temporal change = 0.02). The adjusted ORs among professionals and homemakers increased marginally from 1.09 to 1.19 (p for temporal change = 0.08) and from 1.31 to 1.42 (p for temporal change = 0.10) respectively. The adjusted ORs were highest among professionals, followed by middle-class non-manual and manual workers. Unemployed people showed significantly higher ORs throughout the period: the adjusted ORs for this population were more than double (table 2).

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted ORs (95% CIs) for reporting poor health and relative index of inequality (RII) in income before* and after* the economic recession; CSLC, Japan

| Before | After | p for temporal change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation | |||

| Managerial/administrative | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Professional | 1.09 (0.96 to 1.23) | 1.19 (1.05 to 1.35) | 0.08 |

| Clerical/sales/service | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.14) | 1.14 (1.02 to 1.29) | 0.02 |

| Manual | 1.03 (0.92 to 1.14) | 1.09 (0.97 to 1.22) | 0.25 |

| Other paid job | 1.14 (0.92 to 1.43) | 1.26 (1.03 to 1.54) | 0.28 |

| Homemaker | 1.31 (1.17 to 1.47) | 1.42 (1.25 to 1.61) | 0.10 |

| Unemployed | 2.30 (2.04 to 2.61) | 2.06 (1.79 to 2.37) | 0.80 |

| Income | |||

| Lowest/highest decile | 1.60 (1.47 to 1.74) | 1.43 (1.29 to 1.60) | |

| p trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.06 |

| RII | 1.34 (1.28 to 1.41) | 1.27 (1.19 to 1.36) | 0.20 |

| Age: 40–60/20–39 years | 1.75 (1.68 to 1.83) | 1.50 (1.42 to 1.59) | |

| Gender: female/male | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.16) | 1.15 (1.09 to 1.21) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Never married | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.78) | 0.84 (0.78 to 0.90) | |

| Separated | 1.18 (1.06 to 1.31) | 1.05 (0.90 to 1.23) | |

| Divorced | 1.40 (1.27 to 1.56) | 1.32 (1.19 to 1.48) | |

| Survey year: 1986 or 1998† | 0.94 (0.90 to 0.98) | 1.09 (1.04 to 1.15) |

Before: pooled data from 1986 and 1989; after: pooled data from 1998 and 2001.

Base: 1989 or 2001 respectively.

Gender-stratified analysis demonstrated that the association between occupation and perceived health among middle-class non-manual workers was statistically significant only in males, and it increased significantly over time: the adjusted OR of poor health among male middle-class workers compared with the highest class workers changed from 1.00 to 1.16 (p for temporal change = 0.04). There was a marginal increase in the adjusted OR among female professionals (from 0.98 to 1.27, p for temporal change = 0.10). When stratified by age group (ie, 20–39 and 40–60 years old), analysis found only marginal increase in the adjusted ORs through the economic crisis among younger age professionals, homemakers and the unemployed (p for temporal change = 0.09 for all the groups) (table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) (95% confidence intervals) for reporting fair or poor health by occupation and relative index of inequality (RII) in income by gender or by age group before* and after* the economic recession; CSLC, Japan

| Before | After | p for temporal change | Before | After | p for temporal change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Managerial/administrative | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Professional | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.24) | 1.12 (0.97 to 1.28) | 0.53 | 0.98 (0.76 to 1.27) | 1.27 (0.94 to 1.71) | 0.10 |

| Clerical/sales/service | 1.00 (0.89 to 1.13) | 1.16 (1.02 to 1.32) | 0.04 | 0.91 (0.71 to 1.16) | 1.09 (0.82 to 1.46) | 0.23 |

| Manual | 1.06 (0.94 to 1.19) | 1.12 (0.99 to 1.28) | 0.31 | 0.87 (0.68 to 1.12) | 0.99 (0.74 to 1.32) | 0.51 |

| Other paid job | 1.16 (0.85 to 1.59) | 1.07 (0.81 to 1.43) | 0.90 | 0.99 (0.70 to 1.39) | 1.39 (0.98 to 1.98) | 0.13 |

| Homemaker | –† | 3.94 (1.87 to 8.30) | –† | 1.17 (0.92 to 1.49) | 1.40 (1.05 to 1.86) | 0.28 |

| Unemployed | 2.87 (2.48 to 3.32) | 2.18 (1.85 to 2.58) | 0.26 | 1.62 (1.26 to 2.09) | 1.87 (1.37 to 2.54) | 0.27 |

| Income | ||||||

| Lowest/highest decile | 1.66 (1.47 to 1.87) | 1.48 (1.28 to 1.73) | 1.52 (1.37 to 1.69) | 1.39 (1.21 to 1.59) | ||

| p trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.22 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.12 |

| RII | 1.36 (1.27 to 1.47) | 1.28 (1.17 to 1.41) | 0.32 | 1.32 (1.23 to 1.41) | 1.22 (1.12 to 1.33) | 0.68 |

| Age 20–39 years | Age 40–60 years | |||||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Managerial/administrative | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Professional | 0.85 (0.67 to 1.08) | 1.16 (0.85 to 1.59) | 0.09 | 1.11 (0.96 to 1.28) | 1.14 (0.99 to 1.32) | 0.75 |

| Clerical/sales/service | 0.83 (0.66 to 1.05) | 1.09 (0.80 to 1.48) | 0.11 | 1.03 (0.91 to 1.17) | 1.14 (1.00 to 1.29) | 0.24 |

| Manual | 0.80 (0.63 to 1.01) | 0.99 (0.72 to 1.36) | 0.25 | 1.09 (0.96 to 1.23) | 1.12 (0.98 to 1.27) | 0.73 |

| Other paid job | 0.90 (0.62 to 1.32) | 0.97 (0.63 to 1.50) | 0.69 | 1.19 (0.92 to 1.55) | 1.40 (1.11 to 1.76) | 0.28 |

| Homemaker | 0.83 (0.65 to 1.05) | 1.08 (0.79 to 1.48) | 0.09 | 1.56 (1.37 to 1.77) | 1.57 (1.37 to 1.81) | 0.89 |

| Unemployed | 1.24 (0.96 to 1.59) | 1.63 (1.17 to 2.25) | 0.09 | 3.19 (2.76 to 3.69) | 2.60 (2.20 to 3.08) | 0.08 |

| Income | ||||||

| Lowest/highest decile | 1.65 (1.41 to 1.93) | 1.44 (1.18 to 1.75) | 1.53 (1.38 to 1.69) | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.58) | ||

| p trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.41 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 |

| RII | 1.25 (1.15 to 1.35) | 1.42 (1.24 to 1.63) | 0.10 | 1.32 (1.24 to 1.40) | 1.20 (1.11 to 1.29) | 0.05 |

Before: pooled data from 1986 and 1989; after: pooled data from 1998 and 2001.

The dummy variable was excluded because of no subjects in this category. Models were adjusted for marital status, survey year, either gender or age and either occupation or income.

Income

The adjusted proportion of people reporting poor health ranged from 12.5% to 17.2% in the 1986/1989 dataset, with higher incomes associated with better self-rated health. The proportion decreased in the later years throughout income deciles, and the lower six deciles had larger decreases (–19.8% to –13.7%) compared with the higher deciles (–12.6% to –11.6%) except for the highest decile (–14.8%) (fig 2).

Despite our hypothesis, multivariate models indicated a marginal decline in the income gradient in self-rated health following the crisis (p for temporal change in income trend = 0.06) (table 2), while changes in RII from 1.34 to 1.27 over time were not statistically significant (p for temporal change = 0.20).

Males showed a slightly steeper income gradient in self-rated health. When models were separated by age group, the income gradient became significantly shallower after the crisis among the older age group: p values for temporal change in the income–health trend and the income RII in poor health were 0.01 and 0.05 respectively. However, the RII marginally increased among the younger age group (p for temporal change = 0.10) (table 3).

DISCUSSION

We found that, following the economic crisis in Japan, although absolute health status improved among all the SES categories, when relative disparities were examined, non-manual classes of workers were more likely to report poor health compared with the highest class workers (administrators or managers). These changes were pronounced among males. The likelihood of reporting poor health among unemployed people was twice as high as in the highest class workers irrespective of the crisis. However, we obtained only partial support for our hypothesis with regard to the effect of the economic crisis on the income–health gradient among younger working-age people. In contrast, the income–health gradient was shallower following the crisis among the older working-age people.

The improvement in absolute health status among all SES categories is consistent with Japan's vital statistics showing largely improved mortality and morbidity in the nation. For example, the reduction in cardiovascular mortality between 1985 and 2000 was by 45% in men and by 52% in women.4 The result is also consistent with studies in other countries showing overall improvement in population health despite the impact of the economic crisis.10 15

While overall absolute health status improved over time, we found that occupational disparities in health between the highest class and middle-class males widened after the crisis, which supports our hypothesis. Studies in other countries agree with this finding.11 13 14 For example, Mitchell and colleagues26 reported that the geographical mortality gap across socioeconomic positions in Britain widened following the economic crisis in the 1980s. Previous studies suggest that the adverse effects of economic crises tend to be concentrated among lower SES groups. In contrast to those findings, the results of our study suggest that the deleterious health impact of the economic crisis in Japan has been felt more among white-collar workers (at least in relative terms). This unique pattern is consistent with some Japanese studies, showing that in Japan manual workers do not necessarily have poorer health compared with a higher employment grade.18 27–29 Our study is also consistent with the trend in recent suicide statistics and increased prevalence of coronary risk factors among working-age males.7–9 Vital statistics indicate that the current suicide epidemic has been particularly prevalent among working-age males.4 30 Police reported that 47% of those who killed themselves were unemployed.6 A Japanese large cohort study (n = 15 597) found that perceived health strongly predicted the future incidence of suicide.31 Corporate downsizing not only creates unemployment but also increases job demand among the remaining employees. White-collar workers’ employment position, which was previously guaranteed by their companies, became insecure due to the end of lifetime job security and the collapse of the traditional seniority-based promotion system.32

The relative health status of young female homemakers worsened marginally after the recession. This may be attributable to reduced living standards, marital friction or multiple role occupancy stemming from their laid-off partners or their partners’ deteriorated working conditions.32–34

Contrary to our hypothesis, the income–health gradient became shallower over time at least among older working-age people, which may be due to the smaller improvement in absolute health (or relatively deteriorated health) among middle or higher income compared with lower income people (fig 2). A study in Finland similarly reported a reduction in income disparities in health following an economic crisis.15 The narrowing income–health gradient over time is in agreement with the relative worsening of health among middle or higher class occupations, together suggesting that Japan's economic crisis mainly affected middle or higher SES groups rather than the lower or the highest SES groups. Another potential explanation for the reduced income–health gradient is that formal social supports for the most economically deprived population might be improved.15 However, we were not able to find convincing evidence supporting this. Indeed, the number of households receiving social security benefits increased by 1.2 times from 1990 to 2001, but this fact can be rather considered as the result of increased inequality.35

In younger working-age people, health disparities between the unemployed, homemakers and managers/administrators as well as the overall income–health gradient appeared to increase after the crisis. Because younger people generally have lower wages, they may be more vulnerable to ill-health due to income inequality or economically inactive status.

This study has several strengths. Our national probability sample supports the generalisability of this study. We used comparable surveys across multiple time points, taking advantage of the “natural experiment” caused by the economic recession. On the other hand, some limitations should be noted. First, because of the cross-sectional rather than panel design, we could not tease out reverse causation, ie ill-health resulting in downward occupational mobility. Second, our data was lacking in individual-level information on job insecurity, work overload or pay cuts, so that we could not find how workers were affected by the recession. Third, our outcome was self-reported. However, self-rated health has been shown to be a strong predictor of mortality and other objective health indicators.31 36 37 Finally, despite the large sample size, the statistical significance of the temporal differences before and after the crisis was not sufficient to confirm the gap. This might be attributed to the study design, ie data in 1986 and 1989 may not have been the best choice for the comparison group against the post-crisis period. We also have to evaluate the time trend using a stronger design such as an individual-level panel study.

In sum, the present study provides important evidence that, despite the improved absolute health status throughout all social classes, in relative comparison, self-rated health among middle-class male workers might deteriorate following the economic recession, along with that of their spouses at home. Although this post-recession SES–health pattern is not concordant with that reported from other countries, our results are supported by the recent suicide epidemic and rising coronary risk profile among male Japanese workers.6 16 30 38 39 The persistent poor relative health status among unemployed people is also of concern. Although our findings on the effect of economic recession on health disparities warrant further confirmation, our study revealed clear health disparities by SES in Japan, as well as an adverse impact of the economic recession on relative SES disparities in health. A recent international ecological comparative study indicated a much shallower association between income and mortality in Japan compared with Britain around 1990.40 Our results suggest that it may be time to re-examine the impact of the decade-long economic recession on the health of the Japanese. Moreover, policies need to pay greater attention to SES as a social determinant of health in Japan, as well as to working conditions, which seem to have deteriorated particularly for white-collar workers during the post-recession period.16 41

What this study adds.

▶ The impact of economic recession on population health is debated. Some ecological studies suggest lower mortality rates during recession. Few individual-level studies have been reported.

▶ Japan underwent a prolonged economic recession in the 1990s. Using individual-level data, we find that self-rated health improved throughout the period for Japanese men and women. However, occupational class-based inequalities in poor health widened during the same period. Middle-class male workers and female homemakers were particularly adversely affected by the crisis, compared with the highest class workers, while unemployed people had persistently poor health throughout the period.

Policy implication.

Policies need to pay greater attention to SES as a social determinant of health in Japan, as well as to working conditions, which seem to have deteriorated particularly for white-collar workers during the post-recession period.

Acknowledgements

NK conceived the study, completed the analysis and wrote the draft. SVS assisted with statistical analysis and conceptualised ideas. IK supervised the study and helped to conceptualise ideas. YT and ZY contributed to data collection and project management. We gratefully appreciate the valuable comments of Michael Reich, Marc Mitchell and all fellows and scholars in the 2006–07 HSPH Takemi programme in international health.

Funding: NK is a recipient of the fellowship grant in Takemi Program in International Health at the Harvard School of Public Health, which was funded by the Japan Foundation for the Promotion of International Medical Research Cooperation. SVS is supported by the National Institutes of Health Career Development Award (NHLBI 1 K25 HL081275). This study was also supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, Japan.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO . The World Health Report 2000. World Health Organization; Boston, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmot MG, Smith GD. Why are the Japanese living longer? BMJ. 1989;299:1547–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6715.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tachibanaki T. Confronting income inequality in Japan: a comparative analysis of causes, consequences, and reform. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan . The vital statistics. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; Tokyo: 1955–2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inoue K, Matsumoto M. Karo jisatsu (suicide from overwork): a spreading occupational threat. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57:284–5. doi: 10.1136/oem.57.4.284a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamar J. Suicides in Japan reach a record high. BMJ. 2000;321:528. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7260.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . The national nutrition survey. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; Tokyo: 1986–2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . The fifth basic survey of cardiovascular diseases. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; Tokyo: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arai H, Yamamoto A, Matsuzawa Y, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the general Japanese population in 2000. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2006;13:202–8. doi: 10.5551/jat.13.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khang Y-H, Lynch JW, Kaplan GA. Impact of economic crisis on cause-specific mortality in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1291–301. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khang YH, Lynch JW, Yun S, et al. Trends in socioeconomic health inequalities in Korea: use of mortality and morbidity measures. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:308–14. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.012989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waters H, Saadah F, Pradhan M. The impact of the 1997–98 East Asian economic crisis on health and health care in Indonesia. Health Policy Plan. 2003;18:172–81. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czg022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anitua C, Esnaola S. Changes in social inequalities in health in the Basque Country. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:437–43. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.6.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell R, Dorling D, Shaw M. Inequalities in life and death. What if Britain were more equal? Policy Press; Bristol: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lahelma E, Rahkonen O, Huuhka M. Changes in the social patterning of health? The case of Finland 1986–1994. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:789–99. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukuda Y, Nakao H, Yahata Y, et al. Are health inequalities increasing in Japan? The trends of 1955 to 2000. BioSci Trend. 2007;1:38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ILO . International standard classification of occupations, ISCO-88. International Labour Organization; Geneva: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martikainen P, Lahelma E, Marmot M, et al. A comparison of socioeconomic differences in physical functioning and perceived health among male and female employees in Britain, Finland and Japan. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1287–95. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishi N, Makino K, Fukuda H, et al. Effects of socioeconomic indicators on coronary risk factors, self-rated health and psychological well-being among urban Japanese civil servants. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1159–70. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honjo K, Kawakami N, Takeshima T, et al. Social class inequalities in self-rated health and their gender and age group differences in Japan. J Epidemiol. 2006;16:223–32. doi: 10.2188/jea.16.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy BP, Kawachi I, Glass R, et al. Income distribution, socioeconomic status, and self rated health in the United States: multilevel analysis. BMJ. 1998;317:917–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7163.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shibuya K, Hashimoto H, Yano E. Individual income, income distribution, and self rated health in Japan: cross sectional analysis of nationally representative sample. BMJ. 2002;324:16–19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7328.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davey Smith G, Dorling D, Mitchell R, et al. Health inequalities in Britain: continuing increases up to the end of the 20th century. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:434–5. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.6.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyinch J, Kaplan C. Socioeconomic position. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Measuring the magnitude of socio-economic inequalities in health: an overview of available measures illustrated with two examples from Europe. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:757–71. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Appendix B . Evidence of a still-widening health gap. In: Mitchell R, Dorling D, Shaw M, editors. Inequalities in life and death. What if Britain were more equal? Policy Press; Bristol: 2000. pp. 62–3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takao S, Kawakami N, Ohtsu T. Occupational class and physical activity among Japanese employees. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:2281–9. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki T, Sugiura M, Furuna T, et al. Association of physical performance and falls among the community elderly in Japan in a five year follow-up study. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 1999;36:472–8. doi: 10.3143/geriatrics.36.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inaba A, Thoits PA, Ueno K, et al. Depression in the United States and Japan: gender, marital status, and SES patterns. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:2280–92. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiho Y, Tohru T, Shinji S, et al. Suicide in Japan: present condition and prevention measures. Crisis. 2005;26:12–19. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.26.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujino Y, Mizoue T, Tokui N, et al. Prospective cohort study of stress, life satisfaction, self-rated health, insomnia, and suicide death in Japan. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35:227–37. doi: 10.1521/suli.35.2.227.62876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crump A. Suicide in Japan. Lancet. 2006;367:1143. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68502-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takeda Y, Kawachi I, Yamagata Z, et al. Multigenerational family structure in Japanese society: impacts on stress and health behaviors among women and men. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeda Y, Kawachi I, Yamagata Z, et al. The impact of multiple role occupancy on health-related behaviours in Japan: Differences by gender and age. Public Health. 2006;120:966–75. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Statistics and Information Department . Operating report of social welfare administration. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; Tokyo: 1985–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferraro KF, Farmer MM, Wybraniec JA. Health trajectories: long-term dynamics among black and white adults. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:38–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCurry J. Japan promises to curb number of suicides. Lancet. 2006;367:383. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watts J. Japanese government offers guidelines for stressed workers. Lancet. 1999;354:1273. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)76050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakaya T, Dorling D. Geographical inequalities of mortality by income in two developed island countries: a cross-national comparison of Britain and Japan. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:2865–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Connor A. Poverty research and policy for post-welfare era. Annu Rev Sociol. 2000;26:547–62. [Google Scholar]