Abstract

Objective To assess whether receiving a negative test result at primary care based stepwise diabetes screening results in false reassurance.

Design Parallel group cohort study embedded in a randomised controlled trial.

Setting 15 practices (10 screening, 5 control) in the ADDITION (Cambridge) trial.

Participants 5334 adults (aged 40-69) in the top quarter for risk of having undiagnosed type 2 diabetes (964 controls and 4370 screening attenders).

Main outcome measures Perceived personal and comparative risk of diabetes, intentions for behavioural change, and self rated health measured after an initial random blood glucose test and at 3-6 and 12-15 months later (equivalent time points for controls).

Results A linear mixed effects model with control for clustering by practice found no significant differences between controls and people who screened negative for diabetes in perceived personal risk, behavioural intentions, or self rated health after the first appointment or at 3-6 months or 12-15 months later. After the initial test, people who screened negative reported significantly (but slightly) lower perceived comparative risk (mean difference −0.16, 95% confidence interval −0.30 to −0.02; P=0.04) than the control group at the equivalent time point; no differences were evident at 3-6 and 12-15 months.

Conclusions A negative test result at diabetes screening does not seem to promote false reassurance, whether this is expressed as lower perceived risk, lower intentions for health related behavioural change, or higher self rated health. Implementing a widespread programme of primary care based stepwise screening for type 2 diabetes is unlikely to cause an adverse shift in the population distribution of plasma glucose and cardiovascular risk resulting from an increase in unhealthy behaviours arising from false reassurance among people who screen negative.

Trial registration Current controlled trials ISRCTN99175498.

Introduction

A national screening programme for cardiovascular risk factors, including testing for type 2 diabetes, is now being implemented.1 Justification for screening programmes requires that the overall benefit of testing—resulting mainly from early intervention in people at risk—is greater than any possible harms of testing the population. Whether this criterion is met for screening for diabetes remains uncertain.2 3

Research evaluating the benefits of screening and early intervention among people at risk of diabetes has shown that stepwise screening identifies those with a raised and potentially modifiable risk of coronary heart disease.4 5 Studies have also examined the direct harms to people attending screening and shown limited evidence of adverse psychological effects associated with diabetes screening programmes in terms of increased anxiety and depression.6 7 8 9 In part, this may be because stepwise screening in the context of primary care offers an opportunity for psychological adjustment as participants progress through the screening programme.10

Research describing the potential harms of screening has focused on people who screen positive,11 12 and few studies have considered the potential indirect harms to people attending screening. In particular, research has yet to examine whether people with a negative test result at diabetes screening may be falsely reassured.13 14 This is important because the potential adverse effects of false reassurance include decreased intentions for behavioural change,3 13 justification of unhealthy behaviours through a “certificate of health” effect,15 16 and delays in seeking medical help.17

As the vast majority (90%) of people who take part in diabetes screening programmes test negative, even a small harm to those who test negative (for example, through a reduction in intentions to be physically active) may outweigh a large benefit to the few people who test positive. The population distribution of plasma glucose in the United Kingdom is approximately normal and shows a positive linear relation to cardiovascular risk.18 19 20 Consequently, if a substantial proportion of people who take part in screening for diabetes are falsely reassured and show a reduction in intentions to improve their diet or increase their level of physical activity as a result of screening, then the net effect of screening could be to move the population distribution of plasma glucose and cardiovascular risk in the wrong direction.

The potential problem of false reassurance in cardiovascular screening has been described as “an unintentional adverse effect of screening . . . evident when people erroneously conclude that their screening result means that they are at less risk than they actually are.”21 Some evidence shows false reassurance associated with screening for cardiovascular risk factors,16 22 but no studies to date have examined false reassurance when quantified as a reduction in intentions for behavioural change or a decrease in perceived risk in the context of diabetes screening.13 14 In particular, a need exists to assess false reassurance among people with risk factors for diabetes who receive a negative test result at screening.23 This is especially timely given the Department of Health’s decision to include screening for diabetes in the national vascular risk assessment programme.1

We aimed to investigate false reassurance in the short term (after the initial appointment) and the medium to long term (three to six months and 12-15 months later) among participants who test negative for diabetes in a primary care based stepwise screening programme. We hypothesised that those who test negative for diabetes would report lower perceived risk of developing diabetes, lower intentions for behavioural change, and higher self reported health than a (non-screening) control group.

Methods

Participants were registered at 15 primary care practices included in the Cambridge arm of the Anglo-Danish-Dutch Study of Intensive Treatment in People with Screen Detected Diabetes in Primary Care (the ADDITION trial). A comprehensive description of the screening procedure and recruitment methods for this study has been published.4 7 The ADDITION (Cambridge) trial aims to evaluate the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a stepwise screening strategy for type 2 diabetes and intensive multifactorial treatment for people with screen detected diabetes in primary care.4 The primary outcomes in this trial are modelled cardiovascular risk at one year and cardiovascular mortality and morbidity at five years after diagnosis of diabetes.

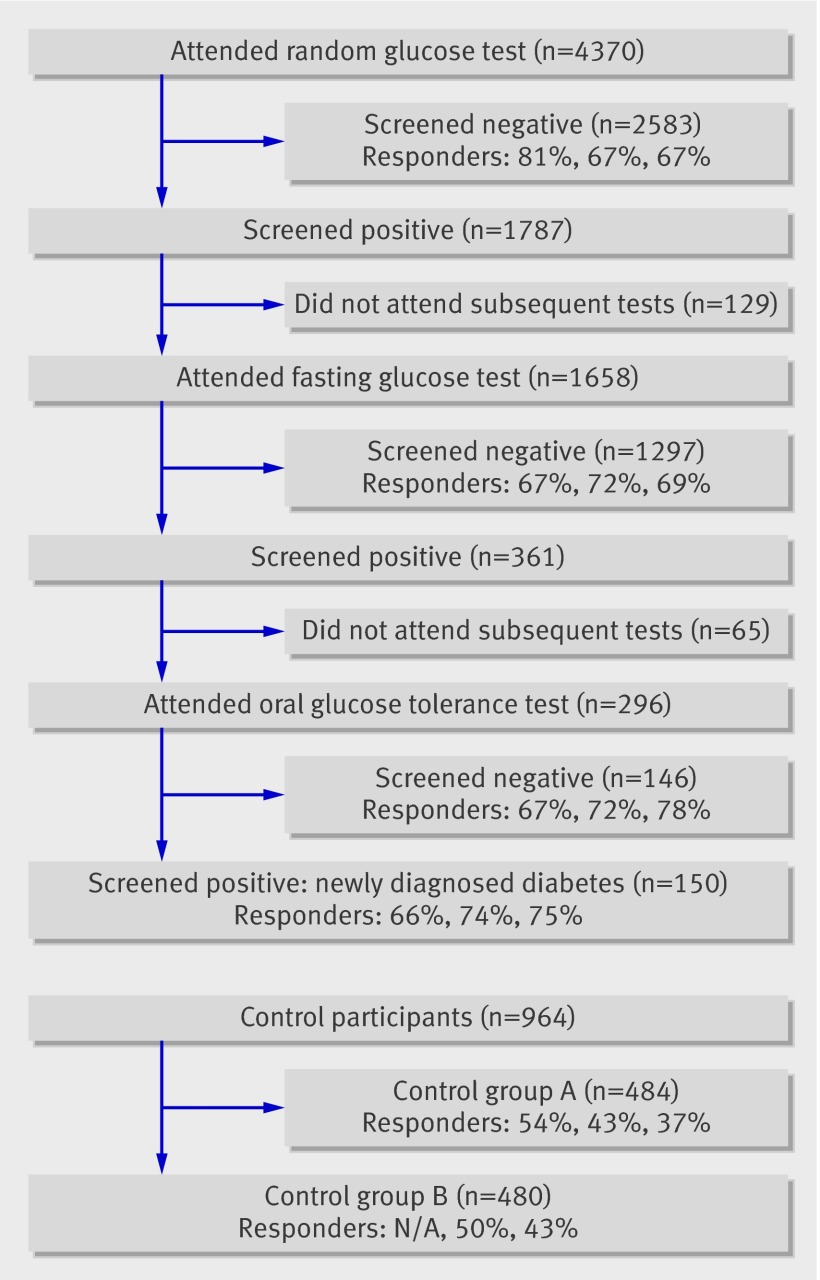

Embedded within the ADDITION (Cambridge) trial was a substudy that aimed to quantify the short term and long term psychological impact of primary care based stepwise screening for type 2 diabetes.7 Specifically, the psychological impact study aimed to examine the direct harms or benefits to screening attenders in terms of anxiety and depression,7 10 and to investigate the indirect harms caused by false reassurance (the focus of this paper). The psychological impact study was a controlled trial comparing screening attenders (n=4370) from 10 screening practices with controls (n=964) from five practices whose patients were not invited to screening; the primary comparison to test for false reassurance is between those who test negative for diabetes at screening and (non-screened) controls. The figure shows the design of this study and the flow of participants through the screening programme.

Flow of participants through screening programme, with questionnaire response rates at each time point (after initial appointment, 3-6 months later, 12-15 months later)

In the 10 screening practices, patients aged 40-69 years identified by the Cambridge diabetes risk score as being in the top quarter of risk of having undiagnosed diabetes (n=6416) were invited to attend a stepwise diabetes screening programme.24 The stepwise screening programme has been described previously.4 7 The invitation letter informed patients that “from the information in your medical records you have been identified as being at risk of having undiagnosed diabetes,” and invited them to attend a random capillary blood glucose test in general practice. People who tested positive at this initial test (n=1787) were told: “According to this test, you have about a 15-20% chance of having diabetes. In order to find out for certain whether you have diabetes or not, we need to do further tests.” Participants with a random blood glucose of 5.5 mmol/l or more were invited to return on a different day for a fasting capillary blood glucose test. People who tested positive at the fasting blood glucose test were told: “This test result does suggest that you have diabetes, but a diagnosis of diabetes is for life, so it is very important that we make absolutely sure that you have the condition. To confirm diagnosis of diabetes you will need to make an appointment for a blood test at a local hospital.” Those with either a fasting blood glucose of 6.1 mmol/l or above, a fasting blood glucose of 5.5-6.1 mmol/l and a glycated haemoglobin of 6.1% or more, or a random blood glucose of 11.1 mmol/l or above were invited to attend for a standard 75 g oral glucose tolerance test at an outpatient centre. Diagnosis of type 2 diabetes was made according to the World Health Organization’s criteria.25 Participants who tested negative for diabetes at any stage in the stepwise screening programme were told: “This test is normal; you do not have diabetes.”

In the screening practices, patients who attended for the initial test (n=4370) were given a questionnaire to complete and return by mail to the research centre. Questionnaire data from this time point (time 1) represent participants’ views after the initial test when they had been informed either that they did not have diabetes (screened negative) or that they needed further tests (screened positive). Follow-up questionnaires were sent three to six months (time 2) and 12-15 months (time 3) after the initial test.

In the five control practices, a 25% random sample of participants identified as being in the top quarter of risk (n=964) were randomly allocated to two groups (A and B). Group A (n=484) were sent questionnaires at three time points equivalent to those for participants in the screening practices, and group B (n=480) received questionnaires at times 2 and 3 only—for a substudy investigating measurement effects.26 The letter accompanying the questionnaire informed control participants that “some people of your age can have diabetes without realising it.”

Consent to participate in the questionnaire study was obtained during attendance at the initial test; control participants received an information sheet and consent form from their practice with their first questionnaire. At each time point, participants who had not returned a questionnaire after approximately three weeks were sent one reminder (including another copy of the questionnaire).

Outcome measures

Perceived personal risk—Participants were asked to estimate their chance of getting diabetes at some time in their life. Responses were given as a percentage score on an 11 point scale ranging from 0% to 100%.

Perceived comparative risk—Participants were asked to indicate their chance of getting diabetes, compared with other people of their age. Response options provided on a five point rating scale were (1) much lower, (2) a little lower, (3) about the same, (4) a little higher, and (5) much higher.27

Behavioural intention—Participants were asked to rate three statements of intention to be more physically active, to eat a lower fat diet, and to reduce the amount of dietary sugar in the next 12 months. Response options provided on a five point rating scale were (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) neither agree nor disagree, (4) agree, and (5) strongly agree.

Self rated health—A single item asked about the participant’s general health, with response options of (1) excellent, (2) very good, (3) good, (4) fair, and (5) poor.

Sample size

We determined the sample size in a previous substudy to quantify the effects of screening on anxiety and depression.7 The observed 95% confidence interval for the primary outcome, personal risk, in this study incorporates the observed clustering of the outcome by practice and provides the basis of an indicative post hoc calculation of detectable effect sizes. We would have 80% power to detect a difference between screened and control groups in mean personal risk of 6.5 scale units at baseline (standardised difference of 0.30 SD) and 5.75 units at later time points (equivalent to effect size differences of 0.3 SD and 0.27 SD).

Analyses

We first explored differences in the demographic and clinical characteristics of control group participants and screening attenders (and also those who screened negative) by using analysis of variance and χ2 tests. We used χ2 tests to assess differences between questionnaire responders and non-responders. Primary analyses used a linear mixed effects model to compare participants who screened negative for diabetes with controls on outcome measures at the initial time point and at three to six months and 12-15 months after screening. Because allocation of participants to groups for the controlled trial was practice based,4 7 we entered practice as a random effect in all multivariate models to account for potential clustering. We assessed hypotheses by using two sided tests at the 5% level of significance. Firstly, we assessed differences in perceived risk, behavioural intentions, and self rated health at time 1 between people who screened negative and controls. Secondly, we assessed differences in perceived risk, behavioural intentions, and self rated health between four screening subgroups and controls at times 2 and 3. To further examine the effect of progress through a stepwise screening programme, we used linear regression analysis to examine the relation between number of screening and diagnostic tests and perceived risk among people who screened negative for diabetes.

Results

Of 6416 people invited to screening, 68% (n=4370) attended the initial random capillary blood glucose test in general practice. Among the screening attenders, 82% (n=1465) of 1787 screen positives and 81% (n=2092) of 2583 screen negatives returned a completed questionnaire after their first appointment. Removal of 310 questionnaires from people who screened positive that were returned late (after the date of a follow-up fasting capillary blood glucose test or oral glucose tolerance test) gives an amended response rate of 65% (n=1162) for the screen positive group. Control group response rates were 54% (n=261) at the first contact point, 47% (n=454) at three to six months, and 40% (n=386) at 12-15 months. The figure shows the flow of participants through the screening programme and the questionnaire response rates at each time point.

We found no significant differences between controls and screening attenders in terms of age, sex, body mass index, diabetes risk score, or prescription of antihypertensive drugs at baseline (table 1). No significant differences in baseline data existed between controls and people who screened negative at the initial test (table 1). Overall, at time 1, self rated health was high and intentions to change behaviour were modest: 77% of participants rated their health as good, very good, or excellent; 61% intended to reduce their dietary fat; and 54% intended to increase their levels of physical activity.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of control group, screening attenders, and people who screened negative in initial test. Values are means (SD) unless stated otherwise

| Demographic and clinical variables | Control group (n=964) | Screening attenders (n=4370) | P values* for group differences† | Screened negative at initial test (n=2583) | P values* for group differences‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 58.6 (7.8) | 58.7 (7.6) | 0.76 | 58.1 (7.6) | 0.63 |

| No (%) female | 343 (36) | 1629 (37) | 0.42 | 993 (38) | 0.22 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.6 (4.9) (n=887) | 30.3 (4.5) (n=4027) | 0.38 | 30.3 (4.4) (n=2376) | 0.37 |

| Cambridge diabetes risk score | 0.41 (0.19) (n=886) | 0.41 (0.19) (n=4027) | 0.65 | 0.40 (0.19) (n=2376) | 0.19 |

| No (%) prescribed antihypertensive drugs | 472 (49) | 2141 (49) | 0.83 | 1201 (47) | 0.47 |

*χ2 tests and univariate (analysis of variance) tests for group differences.

†Comparing control group and screening attenders.

‡Comparing control group and people who screened negative at initial random blood glucose test.

Immediate impact of initial screening result

Planned comparisons showed no statistically significant differences in mean scores for the three behavioural intention variables, self rated health, or perceived personal risk between controls and people screening negative at time 1 (table 2). People who screened negative for diabetes at the initial test reported a slightly lower perceived comparative risk of developing diabetes in the future than did control participants (mean difference −0.16, 95% confidence interval −0.30 to −0.02; P=0.04) (table 2).

Table 2.

Differences in psychological variables between screening attenders and control participants at initial time point*. Values are means (SD) unless stated otherwise

| Psychological variables | Control group A, non-screening | Screened negative at initial (random blood glucose) test | Screened positive at initial test and referred for further testing | Difference† (95% CI); P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal risk | 31.5 (22.7) (n=251) | 29.9 (20.8) (n=1994) | 34.9 (22.2) (n=1079) | −1.58 (−4.79 to 1.65); 0.35 |

| Comparative risk | 2.92 (0.97) (n=254) | 2.76 (1.02) (n=2013) | 3.04 (0.95) (n=1106) | −0.16 (−0.30 to −0.02); 0.044 |

| Intention to reduce dietary fat | 3.63 (0.96) (n=260) | 3.67 (0.88) (n=2065) | 3.58 (0.89) (n=1140) | 0.04 (−0.08 to 0.17); 0.52 |

| Intention to reduce dietary sugar | 3.54 (1.01) (n=260) | 3.58 (0.92) (n=2058) | 3.52 (0.91) (n=1148) | 0.04 (−0.09 to 0.17); 0.54 |

| Intention to increase exercise | 3.48 (0.94) (n=261) | 3.58 (0.87) (n=2065) | 3.49 (0.87) (n=1138) | 0.10 (−0.02 to 0.21); 0.11 |

| Self rated health | 3.14 (0.85) (n=253) | 3.17 (0.87) (n=2056) | 2.97 (0.89) (n=1142) | 0.02 (−0.15 to 0.19); 0.83 |

*Immediately after initial (random blood glucose) test for screening attenders; first contact for control participants.

†Screen negative group minus control group.

Longer term impact of screening results

Planned comparisons between controls and people who screened negative showed no evidence of false reassurance. No differences existed between controls and people who screened negative for perceived risk or behavioural intention variables at three to six or 12-15 months after the initial screening appointment (table 3).

Table 3.

Differences in psychological variables between screening attenders and control participants after 3-6 months* and 12-15 months* of follow-up. Values are mean (SD) unless stated otherwise

| Psychological variables and time | Control (group A+B), non-screening | Screened negative | Difference† (95% CI); P value | Screened negative at random blood glucose test | Screened negative at fasting blood glucose test | Screened negative at oral glucose tolerance test | Screened positive at oral glucose tolerance test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal risk | |||||||

| 3-6 months | 31.7 (21.2) (n=418) | 31.5 (21.0) (n=2195) | −0.45 (−3.28 to 2.39); 0.76 | 30.9 (20.8) (n=1487) | 31.7 (20.4) (n=631) | 44.2 (25.9) (n=77) | NA‡ |

| 12-15 months | 32.8 (20.7) (n=362) | 32.2 (21.4) (n=2186) | −0.78 (−3.91 to 2.35); 0.63 | 31.6 (21.1) (n=1469) | 32.2 (21.0) (n=631) | 42.6 (26.5) (n=86) | NA‡ |

| Comparative risk | |||||||

| 3-6 months | 2.86 (0.94) (n=426) | 2.84 (0.95) (n=2238) | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.09); 0.74 | 2.83 (0.94) (n=1516) | 2.82 (0.93) (n=644) | 3.23 (1.18) (n=78) | NA‡ |

| 12-15 months | 2.95 (0.95) (n=369) | 2.85 (0.96) (n=2222) | −0.11 (−0.21 to 0); 0.068 | 2.80 (0.96) (n=1495) | 2.91 (0.94) (n=639) | 3.16 (1.03) (n=88) | NA‡ |

| Intention to reduce dietary fat | |||||||

| 3-6 months | 3.68 (0.84) (n=448) | 3.70 (0.87) (n=2294) | 0.01 (−0.07 to 0.10); 0.75 | 3.69 (0.85) (n=1551) | 3.68 (0.89) (n=661) | 3.95 (0.86) (n=82) | 4.10 (0.70) (n=80) |

| 12-15 months | 3.68 (0.85) (n=385) | 3.66 (0.86) (n=2292) | −0.01 (−0.10 to 0.08); 0.83 | 3.70 (0.86) (n=1541) | 3.59 (0.87) (n=662) | 3.72 (0.69) (n=89) | 4.03 (0.79) (n=78) |

| Intention to reduce dietary sugar | |||||||

| 3-6 months | 3.58 (0.91) (n=447) | 3.60 (0.91) (n=2284) | 0.02 (−0.07 to 0.12); 0.67 | 3.59 (0.90) (n=1543) | 3.60 (0.92) (n=659) | 3.83 (0.94) (n=82) | 4.28 (0.75) (n=80) |

| 12-15 months | 3.58 (0.88) (n=383) | 3.60 (0.92) (n=2291) | 0.02 (−0.08 to 0.12); 0.70 | 3.62 (0.92) (n=1542) | 3.54 (0.92) (n=661) | 3.72 (0.79) (n=88) | 4.19 (0.97) (n=78) |

| Intention to increase exercise | |||||||

| 3-6 months | 3.60 (0.81) (n=447) | 3.56 (0.82) (n=2288) | −0.04 (−0.14 to 0.06); 0.48 | 3.59 (0.82) (n=1550) | 3.49 (0.84) (n=656) | 3.65 (0.82) (n=82) | 3.81 (0.71) (n=80) |

| 12-15 months | 3.53 (0.87) (n=385) | 3.55 (0.84) (n=2293) | 0.03 (−0.08 to 0.14); 0.62 | 3.59 (0.84) (n=1541) | 3.48 (0.84) (n=663) | 3.49 (0.84) (n=89) | 3.56 (0.85) (n=78) |

| Self-rated health | |||||||

| 3-6 months | 3.14 (0.80) (n=443) | 3.14 (0.87) (n=2287) | 0.01 (−0.15 to 0.16); 0.94 | 3.17 (0.86) (n=1553) | 3.09 (0.88) (n=654) | 2.98 (0.93) (n=80) | 2.97 (0.85) (n=78) |

| 12-15 months | 3.21 (0.81) (n=383) | 3.16 (0.86) (n=2284) | −0.05 (−0.21 to 0.11); 0.53 | 3.19 (0.85) (n=1533) | 3.12 (0.87) (n=662) | 3.04 (0.84) (n=89) | 3.12 (0.82) (n=78) |

NA=not applicable.

*Time since initial random blood glucose test for screening groups; time since first contact for control group.

†Screen negative group minus control group.

‡Participants who screened positive at oral glucose tolerance test were not asked about their perceived risk of getting diabetes at follow-up time points.

Effect of progress through stepwise screening programme

Progress through the stepwise screening programme was associated with higher mean perceived personal and comparative risk of developing diabetes. We found a significant linear trend in mean scores for perceived personal risk at time 2 (P<0.001) and time 3 (P=0.001) and for perceived comparative risk at time 3 (<0.001) across the three screen negative subgroups (table 3).

Comparison of responders and non-responders

Non-responders to the initial questionnaire in both the screening and control groups were likely to be younger (mean age 56) than responders (mean age 59) and more likely to be male (70% v 61%) but were comparable for body mass index, diabetes risk score, and prescribed antihypertensive drugs. Sensitivity analyses to further investigate potential bias arising from non-response to the questionnaire showed that non-responders in the screen negative group would have had to report a mean perceived personal risk at least 10.5 units (on a scale from 0% to 100%) lower than their responding counterparts to affect the conclusions of our study in relation to false reassurance.

Discussion

Our results show very limited evidence of false reassurance among people who received a negative test result after attending screening for diabetes. In the short term, those who screened negative at the initial test did not report a lower perceived personal risk of developing diabetes or lower intentions for behavioural change than a non-screening control group. They reported a lower perceived comparative risk of developing diabetes, but the difference was very small. We found no evidence of false reassurance in the medium to long term; people who screened negative did not report a lower perceived risk of diabetes or lower intentions for behavioural change than the control group at three to six or 12-15 months after the initial test. The findings suggest that the process of attending a primary care based stepwise diabetes screening programme would be unlikely to lead to an adverse shift in the population distribution of plasma glucose and cardiovascular risk as a result of an increase in unhealthy behaviours arising from false reassurance among people who screen negative.

Variations in the process and context of a screening programme may influence perceptions of residual risk.10 In terms of the number of tests needed, an inadequate or ambiguous test result has been associated with psychological costs including increased anxiety in a cervical screening programme.28 Our findings show a linear trend of increasing perceived risk associated with progression through the different tests involved in the screening programme. However, this is mainly explained by the much higher perceived risk among people who tested negative at the final diagnostic test, compared with the two groups who screened negative at the earlier tests. This may be because the earlier practice based tests were done by a known practice nurse in familiar surroundings compared with the unfamiliarity of the hospital outpatient context of the final test.

Strengths and limitations

The large sample size in this study enabled examination of subgroups of participants who screened negative at different stages in the screening programme. The prospective research design allowed investigation of false reassurance in the short, medium, and longer term. Inclusion of a control group enabled investigation of the impact of a negative test result alone, as opposed to in comparison with a positive result. Embedding the study within the ADDITION trial provided a real world setting.

The study has some limitations. No operational definition of false reassurance has been agreed; in this paper we define the construct in terms of perceived risk, behavioural intentions, and self rated health. Room for improvement in assessing participants’ interpretation of their negative test result exists—in particular, how it will change their behaviour or be taken as “proof that they did not need to change their way of life.”16 As noted earlier, and previously,7 10 the stepwise nature of the screening programme is likely to evoke different psychological responses from other types of diabetes screening being considered,29 thus altering the generalisability of our findings.

We acknowledge the low relative response rates to the questionnaire survey among control participants (54%, 47%, and 40% at first contact point, three to six months, and 12-15 months) and possible selection bias among people who chose to respond to the invitation to screening as limitations in this study. However, little evidence of bias owing to non-response affecting the comparability of the control and screening groups exists; our results show no differences in terms of demographic or clinical characteristics at baseline between controls and screening attenders or between controls and people who screened negative at the initial random blood glucose test. Sensitivity analyses showed that if non-responders had reported lower perceived risk than questionnaire responders the effect would be to lower perceived risk in the control group and to further reduce the evidence in favour of false reassurance among those who test negative for diabetes. Non-responders in the screen negative group would have to report a mean perceived personal risk of diabetes at least 10% (10.5 units on a scale from 0% to 100%) lower than their responding counterparts to affect the conclusions of our study in relation to false reassurance.

Our finding that false reassurance among those who screen negative is minimal and dissipates with time concurs with evidence from a systematic review.14 It integrates previous findings by showing a short term effect, in common with other studies,17 28 but no long term effect, in keeping with research showing the diminished effects of false reassurance over time.30

Differences in the research design and the measurement of false reassurance may help to explain the variation across studies. For example, false reassurance seems most likely in cross sectional research and in studies that quantify false reassurance in terms of the patient’s understanding of a “normal” test result.17 30 31 As noted earlier, variations in the context of screening programmes may also influence whether patients are falsely reassured. A stepwise primary care based screening programme may minimise false reassurance because it offers multiple points of contact between the patient and health professionals and, therefore, ongoing opportunities to clarify the meaning of a negative test result both within the screening programme and in primary care after screening. False reassurance seems to be more common in certain types of screening programmes, such as those testing for cervical cancer,28 30 perhaps because a substantial proportion of screening attenders report that they do not understand the meaning of their test result.17

Participants’ interpretation of their screening test results is likely to be influenced by the explanation given by the healthcare professional doing the test.21 A qualitative paper that reports patients’ experiences of screening for type 2 diabetes in the ADDITION study indicates that many of those who test negative at diabetes screening seem to be unaware of their residual risk of diabetes10; this suggests that the explanation of the results of screening tests could be improved. To maximise the potential benefits of diabetes screening programmes, the explanation of a negative test result could convey both the residual risk of diabetes and that ways exist to reduce this risk through behavioural change.

Directions for future research:

Considering the limitations outlined, theoretical development is needed to generate a shared understanding of false reassurance—in terms of both the psychological and behavioural meanings and to whom it applies—and thus an agreed operational definition. Furthermore, a measure, preferably objective, of actual behaviour rather than intentions would enable future research to assess the behavioural consequences of false reassurance.

Targeted screening programmes such as ADDITION need to ensure that people who screen negative (at any stage in the series of tests) do not misunderstand the meaning of their test result. Screening negative does not mean no risk of diabetes; rather, for this group (those identified as having risk factors for developing diabetes by use of a risk score), it means “low risk” of having diabetes now but increased risk of developing diabetes and related adverse health outcomes in the future. Research into cervical screening found that 20% of women with an inadequate result followed by a normal repeat smear failed to appreciate their residual risk.30 We find it promising therefore that our study participants who progressed the furthest through the tests before screening negative perceived higher personal risk than those who screened negative at earlier tests. Research to establish the most effective ways of communicating screening test results and residual risks would be helpful.

Implications for population health

Although some studies have suggested that screening programmes could interfere with population strategies that aim to reduce heart disease,22 little evidence shows that implementing a primary care based stepwise screening programme for diabetes (based on the ADDITION (Cambridge) trial) would have a negative net effect on intentions to increase physical activity or to reduce dietary fat and sugar in the screened population.

Implications for diabetes screening

Screening for diabetes is now under way within the vascular risk assessment programme, but debate continues as to when and how to do this screening.2 3 23 29 A key criterion for the justification of screening programmes is that the overall benefit of testing the population is greater than any possible harms,3 so arguments for screening for diabetes should be evidence based and contextualised within a framework that weighs up the benefits versus harms of screening. Research shows limited evidence of harms to screening attenders, either from increased anxiety or depression or from false reassurance among those who receive a negative result at screening (this paper).7 8 9 Furthermore, evidence is growing of the benefits of screening; for example, stepwise screening identifies people with a raised and potentially modifiable risk of coronary heart disease.5 This study adds to accumulating evidence showing that the overall benefit of widespread testing is likely to be greater than the possible harms to the population, and this suggests that justification of screening for diabetes is becoming less “uncertain.”3 However, important questions still remain concerning the cost effectiveness of widespread screening.

What is already known on this topic

Screening for type 2 diabetes does not seem to have an adverse psychological impact in terms of increased anxiety and depression

The potential adverse effects of false reassurance among people who test negative for diabetes at screening are unknown; no evidence is available from controlled trials

What this study adds

A negative test result at diabetes screening does not seem to promote false reassurance

Primary care based stepwise screening for diabetes is unlikely to cause an adverse shift in risk perceptions, health related behaviours, or the population distribution of plasma glucose and cardiovascular risk

We are grateful to the patients and the practices for their participation. We thank the Cambridge ADDITION trial coordination team, in particular Kate Williams (trial manager), Nick Wareham (principal investigator), and the MRC field epidemiology team (leads: Susie Hennings and Paul Roberts).

Contributors: CAMP, HCE, SRS, and SJG conceived the idea for the paper. HCE coordinated the original study and cleaned the data. CAMP, ATP, and JV analysed the data. CAMP wrote the first draft of the manuscript with HCE, SJG, and SRS. All authors contributed to the final draft. CAMP is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by a project grant from the Wellcome Trust (reference number 071200/Z/03/Z). The Cambridge ADDITION trial was funded by the Wellcome Trust (reference number G0000753), the Medical Research Council, and NHS R&D support funding. A-LK and SJG are members of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research. SJG receives support from the Department of Health NIHR Programme Grant funding scheme (RP-PG-0606-1259). The General Practice and Primary Care Research Unit is supported by NIHR funds. CAMP is funded by an ESRC postdoctoral fellowship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: This substudy of the ADDITION (Cambridge) trial was approved by the Eastern MREC. All participants gave written informed consent.

Data sharing: Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from corresponding author at camp3@medschl.cam.ac.uk.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b4535

References

- 1.Department of Health. Putting prevention first—vascular checks: risk assessment and management. DH, 2008.

- 2.Wareham NJ, Griffin SJ. Should we screen for type 2 diabetes? Evaluation against National Screening Committee criteria. BMJ 2001;322:986-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waugh N, Scotland G, McNamee P, Gillett M, Brennan A, Goyder E, et al. Screening for type 2 diabetes: literature review and economic modelling. Health Technol Assess 2007;11(17):1-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Echouffo-Tcheugui J, Simmons R, Williams K, Barling R, Prevost AT, Kinmonth A, et al. The ADDITION-Cambridge trial protocol: a cluster-randomised controlled trial of screening for type 2 diabetes and intensive treatment for screen-detected patients. BMC Public Health 2009;9:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandbaek A, Griffin S, Rutten G, Davies M, Stolk R, Khunti K, et al. Stepwise screening for diabetes identifies people with high but modifiable coronary heart disease risk: the ADDITION study. Diabetologia 2008;51:1127-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adriaanse MC, Snoek FJ, Dekker JM, van der Ploeg HM, Heine RJ. Screening for type 2 diabetes: an exploration of subjects’ perceptions regarding diagnosis and procedure. Diabet Med 2002;19:406-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eborall HC, Griffin SJ, Prevost AT, Kinmonth A-L, French DP, Sutton S. Psychological impact of screening for type 2 diabetes: controlled trial and comparative study embedded in the ADDITION (Cambridge) randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007;335:486-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farmer AJ, Doll H, Levy JC, Salkovskis PM. The impact of screening for type 2 diabetes in siblings of patients with established diabetes. Diabet Med 2003;20:996-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skinner TC, Davies MJ, Farooqi AM, Jarvis J, Tringham JR, Khunti K. Diabetes screening anxiety and beliefs. Diabet Med 2005;22:1497-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eborall HC, Davies R, Kinmonth A-L, Griffin SJ, Lawton J. Patients’ experiences of screening for type 2 diabetes: prospective qualitative study embedded in the ADDITION (Cambridge) randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007;335:490-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thoolen BJ, de Ridder DT, Bensing JM, Gorter KJ, Rutten GE. Psychological outcomes of patients with screen-detected type 2 diabetes: the influence of time since diagnosis and treatment intensity. Diabetes Care 2006;29:2257-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adriaanse MC, Snoek FJ, Dekker JM, Spijkerman AMW, Nijpels G, Twisk JWR, et al. No substantial psychological impact of the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes following targeted population screening: the Hoorn screening study. Diabet Med 2004;21:992-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petticrew MP, Sowden AJ, Lister-Sharp D, Wright K. False-negative results in screening programmes: systematic review of impact and implications. Health Technol Assess 2000;4(5):1-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw C, Abrams K, Marteau TM. Psychological impact of predicting individuals’ risks of illness: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:1571-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adriaanse MC, Snoek FJ. The psychological impact of screening for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2006;22:20-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tymstra T, Bieleman B. The psychosocial impact of mass screening for cardiovascular risk factors. Fam Pract 1987;4:287-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maissi E, Marteau TM, Hankins M, Moss S, Legood R, Gray A. Psychological impact of human papillomavirus testing in women with borderline or mildly dyskaryotic cervical smear test results: cross sectional questionnaire study. BMJ 2004;328:1293-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams DR, Wareham NJ, Brown DC, Byrne CD, Clark PM, Cox BD, et al. Undiagnosed glucose intolerance in the community: the Isle of Ely diabetes project. Diabet Med 1995:12:30-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Coutinho M, Gerstein HC, Wang Y, Yusuf S. The relationship between glucose and incident cardiovascular events: a metaregression analysis of published data from 20 studies of 95,783 individuals followed for 12.4 years. Diabetes Care 1999;22:233-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khaw K-T, Wareham N, Bingham S, Luben R, Welch A, Day N. Association of hemoglobin A1c with cardiovascular disease and mortality in adults: the European prospective investigation into cancer in Norfolk. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:413-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marteau T, Kinmonth AL, Thompson S, Pyke S. The psychological impact of cardiovascular screening and intervention in primary care: a problem of false reassurance? Br J Gen Pract 1996;46:577-82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinlay S, Heller RF. Effectiveness and hazards of case finding for a high cholesterol concentration. BMJ 1990;300:1545-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goyder EC. Screening for and prevention of type 2 diabetes. BMJ 2008;336:1140-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffin SJ, Little PS, Hales CN, Kinmonth AL, Wareham NJ. Diabetes risk score: towards earlier detection of type 2 diabetes in general practice. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2000;16:164-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. WHO, 1999.

- 26.French DP, Eborall H, Griffin S, Kinmonth AL, Prevost AT, Sutton S. Completing a postal health questionnaire did not affect anxiety or related measures: randomized controlled trial. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:74-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein ND. Perceptions of personal susceptibility to harm. In: Mays VM, Albee GW, Schneider SF, eds. Primary prevention of AIDS: psychological approaches. Sage, 1989:142-67.

- 28.French DP, Maissi E, Marteau T. Psychological costs of inadequate cervical smear test results. Br J Cancer 2004;91:1887-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillies CL, Lambert PC, Abrams KR, Sutton AJ, Cooper NJ, Hsu RT, et al. Different strategies for screening and prevention of type 2 diabetes in adults: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ 2008;336:1180-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.French DP, Maissi E, Marteau TM. The psychological costs of inadequate cervical smear test results: three-month follow-up. Psycho-Oncology 2006;15:498-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marteau TM, Senior V, Sasieni P. Women’s understanding of a “normal smear test result”: experimental questionnaire based study. BMJ 2001;322:526-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]