Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of the oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and low dose leucovorin (LV) combination in patients with advanced colorectal cancer.

Materials and Methods

Patients with unresectable or recurrent colorectal carcinomas were prospectively accrued. Up to one prior chemotherapy regimen was allowed. Patients received oxaliplatin, 85 mg/m2, administered as a 2-hour infusion on day 1, followed by LV, 20 mg/m2, as a bolus and 5-FU, 1,500 mg/m2, via continuous infusion for 24 hours on days 1 and 2. Treatment was repeated every 2 weeks until disease progression or adverse effects prohibited further therapy.

Results

Between August 1999 and May 2004, 31 patients were enrolled in this study. Of the patients enrolled, 24 and 31 were evaluable for tumor response and survival analysis, respectively. The patients' characteristics included a median age of 59, with 6 (19%) having had prior chemotherapy. No patient achieved a complete response, but nine (38%) attained a partial response. Seven (29%) patients maintained a stable disease and 8 (33%) experienced increasing disease. The median duration of the response was 6 months. After a median follow-up of 9.6 months, the median time to progression was 3.8 months, with a median survival of 10.7 months. The hematological toxicities were mild to moderate, with no treatment-related mortality or infection. The major non-hematological toxicity was gastrointestinal toxicity.

Conclusion

The combination chemotherapy of oxaliplatin, low dose LV and continuous infusion of 5-FU is safe and has a cost-benefit, but is a moderately effective regimen in advanced colorectal cancer. A randomized trial comparing low and high dosages of leucovorin in the FOLFOX regimen is warranted.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasm, Oxaliplatin, 5-Fluorouracil, Leucovorin

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal adenocarcinomas are the fourth most common malignancy both in Korea and worldwide, and the fourth most common cause of cancer related deaths in Korea (1,2). Approximately one half of all patients develop a metastatic disease (3), and the prognosis for these patients is poor, although palliative chemotherapy has been shown to prolong survival and improve the quality of life compared to the best supportive care (4,5).

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), as the first line therapy, has been the most effective single agent for more than 40 years, but has only achieved a 10% objective response in advanced colorectal cancer (6). Leucovorin (LV) modulation of 5-FU has been shown to improve patient survival and the tumor response rate (7).

Oxaliplatin is a diaminocyclohexane platinum complex, and similarly to cisplatin and carboplatin, its main mechanism of action is mediated by the formation of DNA adducts. Oxaliplatin displays in vitro activity against human colorectal cancer cells (8), and has also exhibited in vivo synergistic antitumor activity with 5-FU against transplantable tumor models (9).

When used as a single agent, oxaliplatin has achieved objective response rates between 10 and 24% in metastatic colorectal cancer (10~12). The various schedules of chemotherapy with the oxaliplatin, infusional 5-FU and LV (FOLFOX) combination have been studied, as the first line or as a salvage treatment, in the treatment of advanced colorectal carcinomas, but no consensus on the best regimen among the various FOLFOX schedules yet exists. Furthermore, although most Western studies have used intermediate to high dose LV, no direct evidence exists for higher dose leucovorin being superior to that of lower dose when combined with 5-FU and oxaliplatin.

This study was performed to assess the efficacy and toxicities of the combination chemotherapy of oxaliplatin, low dose LV and continuous infusion 5-FU in patients with advanced colorectal cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1) Patients

Eligible patients had a histologically or cytologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum, with an unresectable or metastatic disease and a bidimensionally measurable lesion. Patients were permitted to have had one prior chemotherapy regimen, consisting of agents other than oxaliplatin in either an adjuvant or metastatic setting. In an analysis of endpoints, patients who had received only adjuvant chemotherapy were categorized into the non-treated group if they had completed treatment more than 6 months prior to registration in this study.

The inclusion criteria also required adequate bone marrow, renal and hepatic functions, an age younger than 75 years and a performance status of less than or equal to 2 according to the ECOG scale. Patients were not permitted to have CNS metastases requiring active treatment.

Clinical and radiological assessments had to be performed within 2 weeks prior to the start of treatment. The initial assessment included a complete medical history and physical examination, complete blood cell counts, chemistry profile, CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) measurement, urine analysis, chest X-ray and CT scans of the abdomen, pelvis and/or chest.

2) Treatment schedule and dose modifications

Patients were treated with oxaliplatin, 85 mg/m2, administered as a 2-hour infusion on day 1, followed by LV, 20 mg/m2, as a bolus and 5-FU, 1,500 mg/m2, via continuous infusion for 24 hours on days 1 and 2. Treatment was repeated every 14 days, and all patients were required to be hospitalized for chemotherapy. A complete blood cell count was obtained prior to the start of each treatment cycle, together with a serum chemistry profile, CEA measurement, physical examination and toxicity assessment.

Toxicities were evaluated and graded according to the WHO criteria. The chemotherapy dose was adjusted according to the complete blood cell counts, obtained immediately prior to each cycle, and other non-hematological toxicities. The dose was reduced by 25% if there was any grade 1 leukopenia or thrombocytopenia; if there was any grade 2 toxicity, the chemotherapy was delayed for at least one week until the patient had recovered. If grade 3 mucositis or diarrhea occurred, the LV and 5-FU was reduced by 25% in the subsequent cycles. If grade 2 neuropathy occurred, the oxaliplatin was reduced by 50% in the subsequent cycles, with grade 3 neuropathy resulting in the complete discontinuation of oxaliplatin.

Treatment was continued until there were signs of disease progression, any unacceptable toxic effect developed or the patient refused further treatment.

3) Evaluation of clinical response

A physical examination, CEA, complete blood cell counts and chemistry profile were obtained between days 12 and 13 of each cycle, with CT scans repeated every three cycles, or earlier in cases of clinical deterioration.

The antitumor activity was evaluated according to the WHO criteria. A complete response (CR) was defined as the complete disappearance of all assessable disease for at least 4 weeks; a partial response (PR) as a decrease of at least 50% in the sum of the products of the diameters of measurable lesions for at least 4 weeks; a stable disease (SD) as a decrease of less than 50% or an increase of less than 25% in the tumor size; and a progressive disease (PD) as an increase of at least 25% or the appearance of new neoplastic lesion (s).

The dose-intensity was calculated as the total cumulative dose divided by the dosing duration. The relative dose-intensity was calculated as the dose-intensity divided by the planned dose-intensity, multiplied by 100. The planned dose-intensities, expressed as milligrams per square meter per week, were 42.5 for oxaliplatin, 1,500 for 5-FU and 20 for LV.

4) Statistical analyses

Survival was measured from the initial date treatment began to the date of death, or the most recent follow-up visit; the response duration was measured from the date the response was declared to the date progression was confirmed, or the last visit without progression; and the time to progression was assessed from the initial date treatment began to the date of progression, or the last visit without progression. Estimations of all median durations were based on the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences between the Kaplan-Meier survival curves were tested using the log-rank test. Comparisons of the response rates for the different variables were performed using the Chi-square test. The Cox-regression was used to analyze the survival according to the relative dose intensity of each drug. All data were analyzed using the SPSS software (version 10.0).

RESULTS

1) Patients

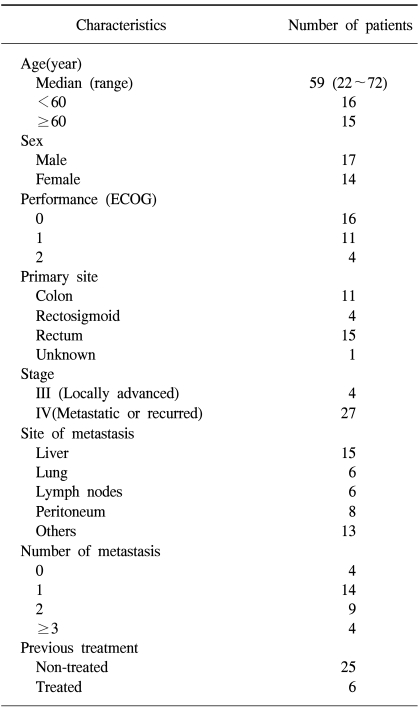

Between August 1999 and May 2004, a total 31 patients, who visited Chungbuk National University Hospital, were enrolled. The patients' characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median patient age was 59 years, ranging from 22 to 72, with 4 patients older than 70 years. There were 17 male and 14 female patients. The 11, 15 and 4 patients had colon, rectal and rectosigmoid cancers, respectively. The location of the primary tumor was unable to be identified in one patient. The liver was the most common site of metastasis, which was present in 15 patients.

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics

Of all the patients, 11 had received prior adjuvant chemotherapy, with 7 of these having received 5-FU based regimens. Six patients had had previous chemotherapy within 6 months prior to registration. The median length of follow-up of the patients was 9.6 months, ranging from 1 to 65 months.

2) Response to treatment

A total of 127 chemotherapy cycles were administered during this study, with a median number of cycles of 4, ranging from 1 to 10. The mean dose intensities of oxaliplatin, 5-FU and LV were 36.2, 1,220 and 16.2 mg/m2/week, respectively. All the relative dose intensities of oxaliplatin, 5-FU and LV were 85%.

Excluding those patients lost or expired prior to evaluation, 24 were able to be evaluated for a response to chemotherapy. No patient achieved a complete response, but 9 (37.5%) showed a partial response. The intention to treat response rate for all patients was 29%. Seven patients showed a stable disease and 8 a progressive disease on initial evaluation after the third cycle of chemotherapy. The reasons for drop-out were referral to other hospitals due to the patients' wish in 2 cases, loss to follow-up without advance notification in 1, an economic problem in 1 and deterioration in clinical stati in a further 3.

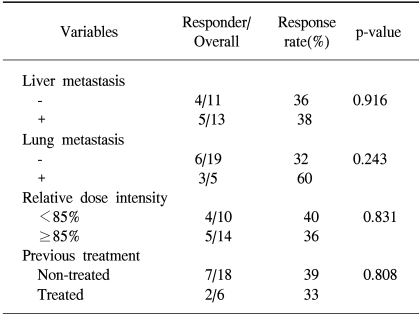

The median duration of the response in the responders was 6 (95% confidence interval, 4.2~7.7) months. The comparison of the response rates according to the patients' characteristics is shown in Table 2. The primary site, number of metastases and presence of liver metastases did not affect the response rate. There was no difference in the response rates between previously treated and non-treated patients (33 vs. 39%, p=0.808).

Table 2.

Objective response according to the variables

3) Survival

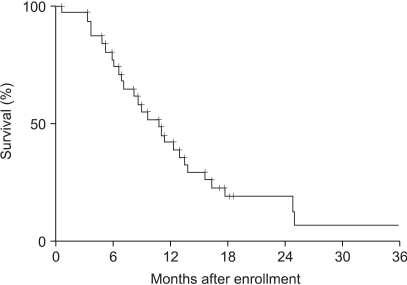

All thirty one patients were evaluable in the survival analyses. After a median follow-up of 9.6 months, 27 patients had died and 4 were still alive.

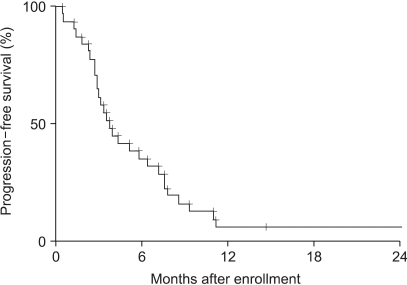

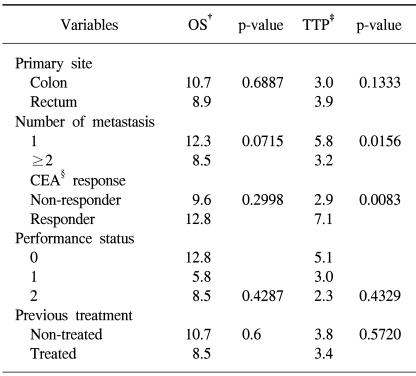

The median overall survival and time to progression were 10.7 (95% confidence interval, 7.6~13.9) (Fig. 1) and 3.8 (95% confidence interval, 2.7~5.0) months (Fig. 2), respectively. Overall survival and time to progression according to the variables are shown in Table 3. Although there was no difference in the overall survival, the time to progression in the CEA responders was longer than in the non-responders (p=0.0083). No difference was observed between the previously treated and non-treated groups.

Fig. 1.

Overall survival curve.

Fig. 2.

Time to progression curve.

Table 3.

Overall survival and time to progression according to the variables*

*all intervals are expressed in months. †overall survival, ‡time to pregression, §response was defined as a reduction in the serum carcinoembryonic antigen level of more than 50% that of the baseline following chemotherapy.

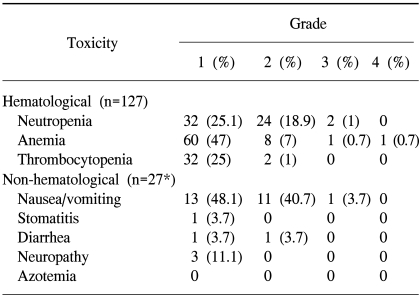

4) Toxicity

The incidences of hematological and non-hematological toxicities are summarized in Table 4. The hematological toxicities were mild to moderate, with grades 1 and 2 leukopenia in 32 (25.1%) and 24 (18.9%) cycles. Grade 1 thrombocytopenia occurred in 32 cycles (25%). Grades 3 and 4 toxicities were rare. The major non-hematological toxicities were nausea and vomiting. Emeses was experienced by 92.6% of patients, but most of these were mild to moderate (either grades 1 or 2).

Table 4.

Adverse reactions to treatment

*evaluable for non-hematological toxicities.

Three patients (9.6%) complained of a tingling sensation at their extremities, including one patient with hand-foot syndrome. No patient developed azotemia. A delay in treatment occurred in 22 cycles because of leukopenia in 13 patients, but there was no treatment-related septicemia or mortality.

DISCUSSION

The combination chemotherapy of oxaliplatin, infusional 5-FU and LV (FOLFOX) has been proven to have antitumor efficacy and safety in metastatic colon cancer in many studies over several years. Recently, the FOLFOX has rapidly replaced the Mayo clinic schedule (bolus 5-FU/LV) as the first line chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer, with its application expanding into adjuvant settings (13,14).

Although many studies have been performed, the best method of infusion, time duration and optimal dosage remain to be confirmed. De Gramont's group studied the efficacy of the combinations (FOLFOX-1 through FOLFOX-7) of oxaliplatin, 5-FU and LV. The FOLFOX regimens generally consist of oxaliplatin, 85~130 mg/m2, 5-FU 2,000~4,000 mg/m2, and LV, 400~1,000 mg/m2. They achieved response rates of 16 to 37% in previously treated colorectal cancer patients. A recently reported trial by the same group employed the FOLFOX regimen, where oxaliplatin was administered at 130 mg/m2 as a two-hour infusion, with a 400 mg/m2 bolus of LV, followed by a 400 mg/m2 bolus of 5-FU, with a further 2.4 g/m2 of 5-FU over 46 hours, every two weeks. The objective response rate in 5-FU refractory patients was 42%, with a median progression free survival of 6 months (15).

Our regimen was a modified version of the FOLFOX 4 scheme. Considering the effective dose of oxaliplatin based on previous studies (11), the oxaliplatin was administered at 85 mg/m2 on day 1. 5-FU, 1,500 mg/m2, was infused continuously for 24 hours on days 1 and 2. The administration of 5-FU by continuous infusion has previously been proved to be superior to that via a bolus (16).

Although most other studies have used moderate to high doses of LV in their FOLFOX regimens, there is no current evidence a higher dose of LV being superior to a lower dose (17). In fact, the Mayo clinic schedule, which uses low dose leucovorin, is both a regulatory standard and the most widely used 5-FU schedule in North America (18).

Therefore, it is postulated that low dose (20 mg/m2) LV would be enough to modulate the antitumor activity of 5-FU.

The 37.5% response rate achieved in this trial was relatively low compared with other studies that use oxaliplatin containing regimens (19,20). The 29% intention to treat response rate was still lower than in other trials. A slightly discouraging outcome of this study may be related to the low dose of leucovorin. Although several randomized trials, comparing low versus high dose leucovorin modulation of bolus 5-FU, have shown low dose leucovorin to be comparable or superior to high dose in the biomodulation of the fluorouracil activity (21,22), the same issue has never been tested with regimens incorporating oxaliplatin. Furthermore, the biochemical mechanism of FU modulation by LV may differ when FU is administered as a continuous infusion over several days (23). Here, this is postulated as being a very important issue that requires priority, as the applications of the FOLFOX regimen are rapidly widened in colorectal cancers.

There have been two other studies (24,25) using similar schedules to those used here, with low dose LV. Kwon et al. used a modified FOLFOX-4 regimen (oxaliplatin, 85 mg/m2, on day 1, LV, 20 mg/m2, and 5-FU, 400 mg/m2, as a bolus, followed by a 600 mg/m2 continuous infusion on days 1 and 2, repeated every 2 weeks) in previously non-treated patients (24). The response rate was 40%, with a median time to progression of 6.6 months. Lee et al. also used the same dosage schedules for oxaliplatin and LV, but 5-FU (1,200 mg/m2) was given as a 6-hour infusion to patients who had previously received fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy (25). The response rate was 42%, with a median progression free survival of 132 days, which were similar to our results.

Although the statistical power of this trial is limited by the small number patients, there were no differences in the response rates (39 vs. 33%) and overall survivals (10.7 vs. 8.5 months) between the previously treated and non-treated patients.

Although speculative, the relatively shorter survival of patients in this study might be attributable; partly, to the negatively selected prognostic features of the patients in our community-based hospital. In fact, patients with higher socioeconomic status, stronger volition and greater compliance to treatment, all of which are unquantifiable, but important prognostic factors, tend to visit larger clinical centers in Korea. For example, one third of the patients in this trial, for numerous reasons, dropped out prior to the third cycle of chemotherapy.

Our regimen was well tolerated, and showed mild overall toxicities. The neuropathy, a reversible side effect of oxaliplatin, which has been an issue in FOLFOX studies, was 10% in this study, a relatively lower incidence than had been originally envisaged.

CONCLUSIONS

The combination chemotherapy of oxaliplatin, low dose LV and continuous infusion of 5-FU is safe and has a cost-benefit, but is a moderately effective regimen in advanced colorectal cancer. A randomized trial comparing low and high dose leucovorin in the FOLFOX regimen is warranted.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae JM, Won YJ, Jung KW, Park JG. Annual report of the Korean central cancer registry program 2000: Based on registered data from 131 hospitals. Cancer Res Treat. 2002;34:77–83. doi: 10.4143/crt.2002.34.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures: 1995. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham D, Pyrhonen S, James RD, Punt CJ, Hickish TF, Heikkila R, et al. Randomised trial of irinotecan plus supportive care versus supportive care alone after fluorouracil failure for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1998;352:1413–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)02309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palliative chemotherapy for advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer: Colorectal Meta-analysis Collaboration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD001545. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park JY, Kim SY, Lee JJ, Yoon HJ, Cho KS. The efficacy of a modified chronomodulated infusion of oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in advanced colorectal cancer (preliminary data) Cancer Res Treat. 2004;36:199–204. doi: 10.4143/crt.2004.36.3.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thirion P, Michiels S, Pignon JP, Buyse M, Braud AC, Carlson RW, et al. Modulation of fluorouracil by leucovorin in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: An updated meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3766–3775. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pendyala L, Creaven PJ. In vitro cytotoxicity, protein binding, red blood cell partitioning, and biotransformation of oxaliplatin. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5970–5976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathe G, Kidani Y, Segiguchi M, Eriguchi M, Fredj G, Peytavin G, et al. Oxalato-platinum or I-OHP, a third generation platinum complex: An experimental and clinical appraisal and preliminary comparison with cisplatinum and carboplatinum. Biomed Pharmacother. 1989;43:237–250. doi: 10.1016/0753-3322(89)90003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levi F, Perpoint B, Garufi C, Focan C, Chollet P, Depres-Brummer P, et al. Oxaliplatin activity against metastatic colorectal cancer: A phase II study of 5-day continuous venous infusion at circadian rhythm modulated rate. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29:1280–1284. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(93)90073-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becouarn Y, Ychou M, Ducreux M, Borel C, Bertheault-Cvitkovic F, Seitz JF, et al. Digestive Group of French Federation of Cancer Centers. Phase II trial of oxaliplatin as first-line chemotherapy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2739–2744. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diaz-Rubio E, Sastre J, Zaniboni A, Labianca R, Cortes-Funes H, de Braud F, et al. Oxaliplatin as a single agent in previously untreated colorectal carcinoma patients: A phase II multicentric study. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:105–108. doi: 10.1023/a:1008200825886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SY. Oxaliplatin: Is it a new standard weapon for colorectal cancer? Cancer Res Treat. 2004;36:91–92. doi: 10.4143/crt.2004.36.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Food and Drug Administration. Eloxatin: New or modified indication. Washington, DC: US Food and Drug Administration; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maindrault-Goebel F, de Gramont A, Louvet C, Andre T, Carola E, Mabro M, et al. High-dose intensity oxaliplatin added to the simplified bimonthly leucovorin and 5-fluorouracil regimen as second-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer (FOLFOX 7) Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1000–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyerhardt JA, Mayer RJ. Systemic therapy for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:476–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.QUASAR Collaborative Group. Comparison of flourouracil with additional levamisole, higher-dose folinic acid, or both, as adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;355:1588–1596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Libutti SK, Saltz LB, Rustgi AK, Tepper JE. Cancer of the colon. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer, Principles and practice of oncology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 2005. pp. 1061–1109. [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Gramont A, Figer A, Seymour M, Homerin M, Hmissi A, Cassidy J, et al. Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2938–2947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.16.2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein D, Mitchell P, Micael M, Beale P, Friedlander M, Zalcber J, et al. Australian experience of a modified schedule of FOLFOX with high activity and tolerability and improved convenience in untreated metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:832–837. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buroker TR, O'Connell MJ, Wieand HS, Krook JE, Gerstner JB, Mailliard JA, et al. Randomized comparison of two schedules of fluorouracil and leucovorin in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:14–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leichman CG, Fleming TR, Muggia FM, Tangen CM, Ardalan B, Doroshow JH, et al. Phase II study of fluorouracil and its modulation in advanced colorectal cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1303–1311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.6.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobrero AF, Aschele C, Bertino JR. Fluorouracil in colorectal cancer: A tale of two drugs-implications for biochemical modulation. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:368–381. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwon HC, Kim KT, Lee SA, Park JS, Kim SH, Kim JS, et al. Oxaliplatin with biweekly, low dose leucovorin and bolus and continuous infusion 5-fluorouracil (modified FOLFOX 4) as first-line therapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2004;36:115–120. doi: 10.4143/crt.2004.36.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JH, Kim TW, Lee KH, Kang YK, Lee JS, Kim SH, et al. Combination of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin in the treatment of fluoropyrimidine-pretreated patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:69–74. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]