Abstract

Aims

Oral anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (AF) is effective but has significant limitations. AZD0837, a new oral anticoagulant, is a prodrug converted to a selective and reversible direct thrombin inhibitor (AR-H067637). We report from a Phase II randomized, dose-guiding study (NCT00684307) to assess safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of extended-release AZD0837 in patients with AF.

Methods and results

Atrial fibrillation patients (n = 955) with ≥1 additional risk factor for stroke were randomized to receive AZD0837 (150, 300, or 450 mg once daily or 200 mg twice daily) or VKA (international normalized ratio 2–3, target 2.5) for 3–9 months. Approximately 30% of patients were naïve to VKA treatment. Total bleeding events were similar or lower in all AZD0837 groups (5.3–14.7%, mean exposure 138–145 days) vs. VKA (14.5%, mean exposure 161 days), with fewer clinically relevant bleeding events on AZD0837 150 and 300 mg once daily. Adverse events were similar between treatment groups; with AZD0837, the most common were gastrointestinal disorders (e.g. diarrhoea, flatulence, or nausea). d-Dimer, used as a biomarker of thrombogenesis, decreased in all groups in VKA-naïve subjects with treatment, whereas in VKA pre-treated patients, d-dimer levels started low and remained low in all groups. As expected, only a few strokes or systemic embolic events occurred. In the AZD0837 groups, mean S-creatinine increased by ∼10% from baseline and returned to baseline following treatment cessation. The frequency of serum alanine aminotransferase ≥3× upper limit of normal was similar for AZD0837 and VKA.

Conclusion

AZD0837 was generally well tolerated at all doses tested. AZD0837 treatment at an exposure corresponding to the 300 mg od dose in this study provides similar suppression of thrombogenesis at a potentially lower bleeding risk compared with dose-adjusted VKA.

This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00684307.

Keywords: Vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), Stroke prevention, Atrial fibrillation, Direct thrombin inhibitor, AZD0837

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF), the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality from stroke and thromboembolism.1 Current guidelines recommend dose-adjusted vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) (e.g. warfarin) titrated to an international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.0–3.0 for thromboprophylaxis in AF patients with moderate to high risk of stroke.2,3 While VKAs can be given orally, they are associated with a number of limitations,4–6 including slow onset and offset of action, a narrow therapeutic index requiring frequent coagulation monitoring and dose adjustment, and interactions with many drugs and with food. The consequence is a variable therapeutic response, leading either to increased risk of bleeding complications or a suboptimal antithrombotic effect, resulting in undertreatment of many patients.6 Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) is recommended in low- to moderate-risk patients or as second-line therapy in patients with contraindications for VKA treatment, although stroke prevention with antiplatelet agents is suboptimal in AF patients compared with VKA.2,7,8 Hence, there is a need for a novel oral anticoagulant that is effective and well tolerated, with a more predictable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile than VKAs, without the inconvenience of regular INR monitoring, while maintaining, or improving, the therapeutic effect.

AZD0837 is a new oral anticoagulant which is rapidly metabolized to AR-H067637, a selective and reversible direct thrombin inhibitor.9,10 The half-life of AR-H067637 is 9–14 h in healthy subjects, and AZD0837 and its metabolites are excreted in the urine and the faeces.11 The safety, tolerability, and pharmacodynamic profile of an immediate-release formulation of AZD0837 have previously been evaluated against warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) in AF.12 An extended-release formulation of AZD0837 has been developed to achieve smooth plasma levels and a stable degree of anticoagulation with a once-daily dosage. The current study is the first to assess an extended-release formulation of AZD0837 in patients with AF.

The primary objective of this Phase II randomized, controlled, parallel, dose-guiding study was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of AZD0837 extended-release vs. dose-adjusted VKA (INR 2.0–3.0) in AF patients with one or more additional risk factors for stroke. Four doses of AZD0837 (i.e. 150, 300, and 450 mg od and 200 mg bid) were selected based on safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic data from previous studies with the immediate-release formulation of AZD0837.12 Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of AZD0837 were also evaluated, including activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), ecarin clotting time (ECT), and fibrin d-dimer (a marker of fibrin turnover and thrombogenesis7).

Methods

This study (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00684307) was conducted in 95 centres within nine European countries (Austria, Denmark, Hungary, Ireland, Norway, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the UK). Patients were enrolled between 20 February 2007 and 4 September 2007. The last patient was followed up on 24 January 2008. All patients gave written informed consent and the trial was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study committees

An independent data safety monitoring board reviewed unblinded safety data monthly during the study and could make recommendations to the Executive Steering Committee to modify the conduct of the study if necessary.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients with a history of paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent non-valvular AF (verified by at least two electrocardiograms in the last year) and at a moderate to high risk of stroke were eligible for enrolment. The patient had to have one or more (high-risk patient) of the following risk factors: previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack, or previous systemic embolism; or one (moderate-risk patient), or two or more (high-risk patient) of the following risk factors: age ≥75 years, symptomatic congestive heart failure, impaired left ventricular systolic function, diabetes mellitus, or hypertension requiring antihypertensive treatment.2 Hypertensive patients were enrolled and randomized into the study only if they were well controlled with antihypertensive treatment aiming for a blood pressure <160/100 mmHg.

Main exclusion criteria were as follows: AF secondary to reversible disorders; contraindication to VKA treatment; valvular heart disease or any condition other than AF requiring chronic anticoagulation treatment; myocardial infarction; stroke or transient ischaemic attack, and/or systemic embolism within the last 30 days; conditions associated with increased risk of major bleeding within the last year; major surgical procedure or trauma within the last 2 weeks; renal impairment (calculated creatinine clearance <30 mL/min); known hepatic disease and/or alanine transaminase (ALT) > 3× upper limit of normal (ULN); treatment with antiplatelet agent other than aspirin ≤100 mg/day or fibrinolytic agents within the last 10 days; or planned cardioversion or surgery during the study.

Randomization

Patients were randomized into five parallel groups: four groups receiving AZD0837 extended-release tablets (150, 300, or 450 mg od or 200 mg bid) and one group receiving VKA (aiming for INR 2.0–3.0) for at least 3 months but no longer than 9 months. The study was double-blind for AZD0837 doses but open for VKA. Randomization into the study was performed in blocks and stratified with respect to VKA-naïve patients, defined as patients never treated with VKA or those previously treated with VKA, but without VKA treatment during the last 3 months before enrolment. Patients were enrolled by the investigators at each study centre and randomized strictly sequentially as they were eligible for randomization. Randomization was centralized via an interactive web or voice-response system connected to a database that was loaded with the randomization schedule. The randomization schedule was computer generated by AstraZeneca R&D.

Patients attended the clinic at enrolment (within 2 weeks before randomization), at randomization, every second week for 12 weeks and then every fourth week until the end of treatment. After the end of randomized treatment, patients were followed up at the clinic after 1 and 4 weeks. The patients were switched to local standard anticoagulation treatment, or were offered to participate in an extension of the trial, as part of a separate protocol (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00645853).

Bleeding classification

Bleeding events were classified as major, clinically relevant minor, or minimal. A major bleeding event was defined as fatal bleeding, clinically overt bleeding causing a fall in haemoglobin level of ≥20 g/L (1.24 mmol/L), or leading to transfusion of two or more units of whole blood or red cells, bleeding in areas of special concern or bleeding causing permanent treatment cessation. Clinically relevant minor bleeding events were defined as clinically overt bleeding causing a fall in haemoglobin level of <20 g/L (1.24 mmol/L) or leading to transfusion of one unit of whole blood or red cells, bleeding causing temporary treatment cessation or bleeding with clinical implications resulting in medical consultation/intervention. Minimal bleeding events were defined as other minor bleedings.

Definitions of adverse events

Adverse events (AEs) were defined as the development of an undesirable medical condition, or the deterioration of a pre-existing medical condition, whether or not considered causally related to the product. Serious AEs were defined as AEs that resulted in death, were immediately life-threatening, required hospitalization, resulted in persistent disability, or were important medical events that could jeopardize the patient or required medical intervention to prevent the outcomes mentioned above.

Safety laboratory assessments

Samples for safety laboratory assessments were taken at enrolment, randomization, every second week for 12 weeks, and then every fourth week until the end of treatment. Follow-up assessments were undertaken at 1 and 4 weeks after the end of treatment [follow-up assessments were not done for patients who continued in the extension trial (n = 523; AZD0837=288, VKA = 235)]. The samples were analysed by a central laboratory (Covance, Switzerland).

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic measurements

For the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analyses, blood samples were taken at randomization, 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks and then every eighth week until the end of treatment. The 2-, 12-, and 36-week samples were taken pre-dose, and at the 2 week visit also at 2 and 4 h post-dose; otherwise, samples were taken at any time. In addition, fibrin d-dimer level was determined at enrolment (baseline value), i.e. without anticoagulation for VKA-naïve patients. The plasma concentration of AR-H067637 was determined with a liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method at Eurofins Medinet B.V., the Netherlands.

The pharmacodynamic variables included APTT (measured using STA Compact analyser and CK Prest reagent, Diagnostica Stago, Asniéres, France) and ECT (BCS coagulation analyser, Dade Behring, Schwalbach, Germany and Ecarin reagent, PentaPharm, Basel, Switzerland) (ECT only for AZD0837 patients), and d-dimer (Trinity Biotech, Umeå, Sweden) (all patients). The reference range for APTT was 24–33 s. The fibrin d-dimer method had a ULN of 130 ng/mL. Samples were analysed by the central laboratory (Covance, Switzerland) and INR was measured locally at the study centres.

Statistical analysis

Sample size

No formal sample size calculation was conducted because the study objectives were very general and could not be translated into a statistical hypothesis to be tested. However, the selected study size was considered adequate to provide relevant information on the safety profile and tolerability of AZD0837. The incidence of bleeding and suppression of d-dimer concentration in plasma was expected to provide data to guide the selection of dose(s) for a Phase III study. In order to evaluate the change from baseline in d-dimer values after at least 4 weeks of treatment, it was aimed to include at least 20 VKA-naïve patients in each AZD0837 treatment group and at least 40 VKA-naïve patients in the VKA treatment group. Experience from previous studies supports that this should be sufficient to demonstrate reduction from baseline in d-dimer of at least 40%.7

Statistical considerations

The population used for statistical analyses included patients who took at least one dose of study treatment, and for whom any post-dose data were available, and was evaluated on treatment (i.e. from first to last dose). Given a treatment period of at least 3 months, but no longer than 9 months, the number of patients available for analysis decreases over time and the statistical interpretations focus on analyses of data up to 12 weeks of treatment. The safety data were evaluated using descriptive statistics. For safety laboratory assessments, the randomization visit was regarded as baseline. Fibrin d-dimer is presented by median values (interquartile range given for measurements at 12–36 weeks on treatment) by treatment and time. All individual d-dimer values have been used to calculate the descriptive statistics presented. Values below 75 ng/mL are estimated with lower precision, but in the calculation of descriptive statistics all values have been ascribed the same weight.

Role of the funding source

The trial was sponsored by AstraZeneca, who were involved in the study design, data interpretation and, in conjunction with the authors, the decision to publish. Employees of the sponsor collected, and managed the data, and performed the data analysis. All authors had access to the clinical study data, and took part in their interpretation. Prof GYH Lip wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors reviewed and contributed to subsequent drafts of the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Results

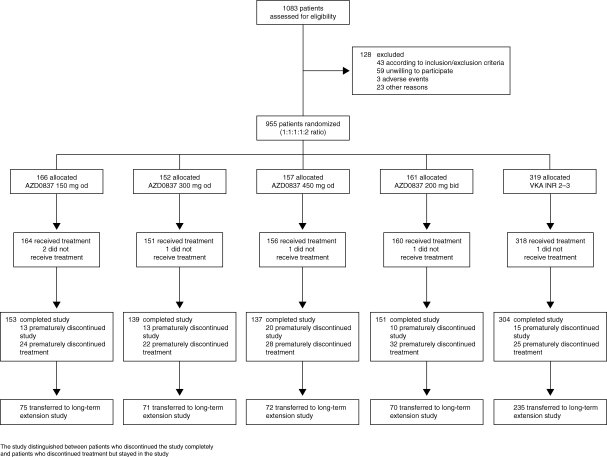

Patient flow through the study is summarized in Figure 1. Of 1083 patients assessed for eligibility, 955 were randomized to treatment. Patient demography, the distribution of risk factors for stroke, and concomitant cardiovascular conditions at randomization are summarized in Table 1. Patients were well matched for age, gender, weight, and body mass index across the five treatment groups, with 28% of AZD0837-treated patients and 30% of VKA-treated patients classed as VKA naïve. Approximately 70% of the patients had two or more risk factors for stroke, with a few patients having six risk factors. The average number of risk factors was 2.1. The most common concomitant cardiovascular condition was hypertension followed by dyslipidaemia, cardiac failure, and coronary artery disease.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram. INR, international normalized ratio; VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

Table 1.

Patient demography including risk factors for stroke and concomitant conditions at randomization

| AZD0837 150 mg od (n = 164) | AZD0837 300 mg od (n = 151) | AZD0837 450 mg od (n = 156) | AZD0837 200 mg bid (n = 160) | Total AZD0837 (n = 631) | VKA INR 2–3 (n = 318) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VKA naïve, % | 28.0 | 27.2 | 26.9 | 30.6 | 28.2 | 30.2 |

| Age in years, mean (range) | 69.9 (43–93) | 69.8 (45–92) | 69.3 (45–88) | 67.8 (34–88) | 69.2 (34–93) | 68.3 (33–87) |

| Gender, male, % | 71.3 | 68.9 | 68.6 | 66.9 | 68.9 | 67.6 |

| Weight in kg, mean (range) | 86.4 (47.0–130.0) | 86.6 (51.0–143.0) | 86.2 (49.0–134.0) | 87.2 (53.0–167.0) | 86.6 (47.0–167.0) | 86.9 (48.0–150.0) |

| BMI in kg/m2, mean (range) | 29.1 (18.8–44.5) | 29.3 (19.0–50.0) | 29.0 (18.9–43.4) | 29.5 (19.6–47.8) | 29.2 (18.8–50.0) | 29.3 (17.8–48.1) |

| Risk factors for stroke in addition to AF, number (%) | ||||||

| At least one risk factor for stroke in addition to AF | 164 (100) | 151 (100) | 156 (100) | 160 (100) | 631 (100) | 318 (100) |

| Previous cerebral ischaemic attack (stroke or TIA) | 19 (11.6) | 21 (13.9) | 24 (15.4) | 28 (17.5) | 92 (14.6) | 47 (14.8) |

| Previous systemic embolism | 2 (1.2) | 4 (2.6) | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.5) | 13 (2.1) | 3 (0.9) |

| Age ≥75 years | 58 (35.4) | 53 (35.1) | 51 (32.7) | 35 (21.9) | 197 (31.2) | 87 (27.4) |

| Symptomatic CHF | 62 (37.8) | 50 (33.1) | 58 (37.2) | 52 (32.5) | 222 (35.2) | 130 (40.9) |

| Impaired left ventricular systolic function | 41 (25.0) | 31 (20.5) | 38 (24.4) | 40 (25.0) | 150 (23.8) | 79 (24.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 32 (19.5) | 26 (17.2) | 42 (26.9) | 42 (26.3) | 142 (22.5) | 96 (30.2) |

| Hypertension requiring antihypertensive treatment | 142 (86.6) | 123 (81.5) | 124 (79.5) | 137 (85.6) | 526 (83.4) | 253 (79.6) |

| Other concomitant cardiovascular condition, number (%) | ||||||

| Coronary artery diseasea | 56 (34.1) | 70 (46.4) | 61 (39.1) | 57 (35.6) | 244 (38.7) | 132 (41.5) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 73 (44.5) | 74 (49.0) | 80 (51.3) | 82 (51.3) | 309 (49.0) | 161 (50.6) |

| Cardiac failure | 68 (41.5) | 56 (37.1) | 60 (38.5) | 56 (35.0) | 240 (38.0) | 139 (43.7) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 8 (4.9) | 6 (4.0) | 9 (5.8) | 7 (4.4) | 30 (4.8) | 17 (5.3) |

AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; CHF, congestive heart failure; INR, international normalized ratio; VKA, vitamin K antagonist; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

aCoronary artery disease: angina pectoris, coronary artery bypass surgery, myocardial infarction, or percutaneous coronary intervention including percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty with or without stent.

Patients treated with AZD0837 were exposed for a mean 142 days (min–max 1–263 days) and patients treated with VKA for a mean 161 days (min–max 9–267 days). Compliance to AZD0837 treatment was high (96%, 97%, 94%, and 94% of patients on AZD0837 150 mg od, 300 mg od, 450 mg od, and 200 mg bid doses, respectively, were taking 90–110% of the dispensed drug). For the VKA-treated patients, treatment within target INR 2.0–3.0 was achieved for 57–68% of patients during weeks 6–36, with a better control in patients previously treated with VKA than in VKA-naïve patients during the first part of the study (data not shown).

Bleeding events

Bleeding events are summarized in Table 2. In the whole cohort, bleeding events were less common in the AZD0837 150 mg od, 300 mg od, and 200 mg bid dose groups and similar in the AZD0837 450 mg od group compared with the VKA group. In the VKA-naïve subgroup, there were fewer bleeding events at all doses of AZD0837 compared with VKA. Clinically relevant bleeding events (i.e. major and clinically relevant minor bleeding events) were numerically less common in the AZD0837 150 mg od and 300 mg od groups compared with the higher dose AZD0837 and VKA both in the whole cohort and in the VKA-naïve subgroup. Patients on aspirin <100 mg/day as concomitant therapy had similar bleeding rates in the AZD0837 and VKA groups.

Table 2.

Number (%) of patients with at least one bleeding event

| AZD0837 150 mg od | AZD0837 300 mg od | AZD0837 450 mg od | AZD0837 200 mg bid | VKA INR 2–3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients, n | 164 | 151 | 156 | 160 | 318 |

| Mean exposure, days | 141 | 144 | 145 | 138 | 161 |

| Any bleeding | 18 (11.0) | 8 (5.3) | 22 (14.1) | 17 (10.6) | 46 (14.5) |

| Major or clinically relevant minor | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.2) | 7 (4.4) | 9 (2.8)a |

| Major | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.9) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (0.6) |

| Clinically relevant minor | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.3) | 5 (3.1) | 8 (2.5) |

| Minimal | 16 (9.8) | 8 (5.3) | 17 (10.9) | 10 (6.3) | 37 (11.6) |

| VKA-naïve patients, n | 46 | 41 | 42 | 49 | 96 |

| Mean exposure, days | 131 | 127 | 144 | 142 | 155 |

| Any bleeding | 3 (6.5) | 1 (2.4) | 4 (9.5) | 4 (8.2) | 17 (17.7) |

| Major or clinically relevant minor | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.8) | 4 (8.2) | 3 (3.1) |

| Major | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.8) | 2 (4.1) | 1 (1.0) |

| Clinically relevant minor | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.1) | 2 (2.1) |

| Minimal | 3 (6.5) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (14.6) |

INR, international normalized ratio; VKA, vitamin K antagonists.

Patients with multiple events in one category are counted once in that category. Patients with events in more than one category are counted once in each of those categories.

aOne patient experienced one major bleed and one clinically relevant minor bleed and is only counted once.

Adverse events

The proportion of patients with AEs was similar between the different AZD0837 doses and the VKA group, as summarized in Table 3 along with discontinuations due to AEs, serious AEs, and deaths.

Table 3.

Number (%) of patients who had at least one adverse event with onset during treatment (safety population)

| AZD0837 150 mg od (n = 164) | AZD0837 300 mg od (n = 151) | AZD0837 450 mg od (n = 156) | AZD0837 200 mg bid (n = 160) | VKA INR 2–3 (n = 318) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean exposure, days | 141 | 144 | 145 | 138 | 161 |

| Adverse events | 96 (58.5) | 88 (58.3) | 92 (59.0) | 92 (57.5) | 197 (61.9) |

| Adverse events leading to discontinuation of study treatment | 11 (6.7) | 11 (7.3) | 16 (10.3) | 20 (12.5) | 5 (1.6) |

| Serious adverse events | 11 (6.7) | 17 (11.3) | 25 (16.0) | 23 (14.4) | 38 (11.9) |

| Deaths | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) |

INR, international normalized ratio; VKA, vitamin K antagonists.

Patients with multiple events in one category are counted once in that category.

Patients with events in more than one category are counted once in each of those categories.

The most common AEs with AZD0837 treatment were gastrointestinal disorders (23 vs. 14% in the VKA group), such as diarrhoea, flatulence, or nausea. Diarrhoea and flatulence were more common in the AZD0837 groups compared with VKA, without any dose–response relationship, and nausea was as common as with VKA. The episodes of diarrhoea most commonly started soon after initiation of study treatment, lasted for 1–3 days, and were of mild intensity.

A greater proportion of patients in the AZD0837 treatment groups (6.7–12.5%) discontinued study treatment than in the VKA treatment group (1.6%). The most common reasons for discontinuation were gastrointestinal disorders.

As expected, since the study was not powered to look at stroke and systemic embolic events, few events were reported. These included ischaemic stroke (two on AZD0837 150 mg od, one on VKA), transient ischaemic attack (one on AZD0837 200 mg bid, one on VKA), and systemic embolus (one on AZD0837 150 mg od). There were also few events with deep vein thrombosis (one on AZD0837 150 mg od, one on AZD0837 200 mg bid) and pulmonary embolism (one on AZD0837 450 mg od, one on VKA). Among the AEs of cardiac origin, three myocardial infarctions were reported (one on AZD0837 300 mg od, one on AZD0837 450 mg od, and one on VKA).

There were six deaths in the trial, three on treatment (one on AZD0837 and two in the VKA group) and three during follow-up. None of the deaths were judged by the study investigator to be a result of the study medication. On treatment, one patient taking AZD0837 (150 mg od group) died from heart failure, 3 days after randomization, and two patients in the VKA group died from sudden death and pulmonary embolism, respectively. Three deaths occurred in the AZD0837 groups during follow-up; one because of pulmonary embolism (150 mg od group, on VKA when she died), one because of intracranial haemorrhage following a skull fracture (300 mg od group, on VKA when he died), and one because of circulatory collapse after a ruptured gastric ulcer (450 mg od group, no information about anticoagulant treatment at time of death was available).

Safety laboratory assessments

There was an increase from baseline in mean S-creatinine of approximately 10% in AZD0837-treated patients. Serum creatinine generally returned to baseline levels following cessation of therapy. Serum cystatine level, a better measure of glomerular filtration rate, was stable for both AZD0837 and VKA treatment. No consistent change or increase in urinary albumin and urinary albumin:creatinine ratio was seen in the AZD0837 treatment groups compared with the VKA group (data not shown).

The incidence of ALT ≥3×ULN was 2.3% for AZD0837-treated patients and 1.6% for VKA-treated patients, with no dose-dependency found across the AZD0837 treatment groups. One patient (in the AZD0837 200 mg bid group) had elevations of ALT ≥3×ULN, bilirubin ≥2×ULN, alkaline phosphatase, and γ-glutamyltransferase, without any symptoms. The study treatment was withdrawn and the elevated levels of ALT and bilirubin normalized within 14 days after the observed peak. This patient had findings of calculus cholecystitis on ultrasound.

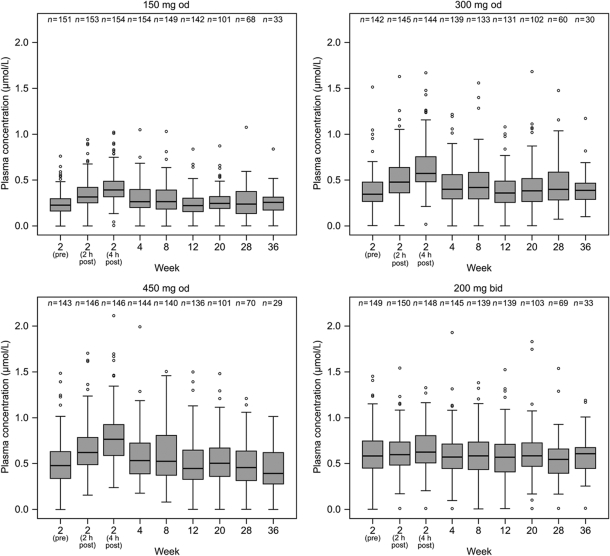

Pharmacokinetic results

Plasma concentrations of AR-H067637 at each dose level over time are presented in Figure 2. Observations obtained at 2 and 4 h post-dose at visit 3, when peak plasma concentrations are expected, showed that low fluctuations compared with trough concentrations were achieved for both od and bid dosing regimens of AZD0837 given in the extended-release formulation. Medians of the observed plasma concentrations, predominately taken at pre-dose (trough concentrations), were approximately 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 µmol/L for those receiving AZD0837 150 mg od, 300 mg od, and 450 mg od, respectively, and 0.6 µmol/L for those receiving 200 mg bid. Within each dose group, the exposures remained consistent during the 36-week treatment period suggesting that steady-state plasma concentrations were achieved within 2 weeks of treatment and the pharmacokinetics of AR-H067637 was stable over time.

Figure 2.

Box and whiskers plots of plasma concentration of AR-H067637 (μmol/L) for each AZD0837 treatment group. Boxes show interquartile range with median indicated. Whiskers extend to the most extreme data point which is not more than 1.5 times the interquartile range. Values outside these limits are individually depicted. The 2-, 12-, and 36-week samples were taken pre-dose (trough values), and at the 2-week visit also at 2 and 4 h post-dose; otherwise, samples were allowed to be taken at any time but were predominantly collected at pre-dose.

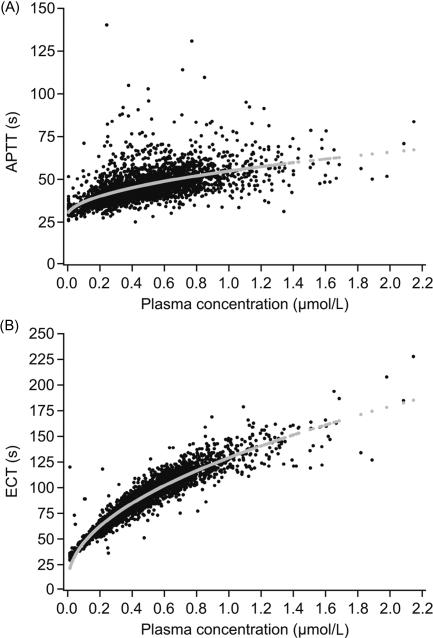

Pharmacodynamic changes

Prolongation effects were observed for the coagulation time assays APTT and ECT and the effects correlated to the plasma concentration of AR-H067637 (Figure 3A and B). Ecarin clotting time was more sensitive, i.e. showed a higher correlation, and the response was less variable than for APTT.

Figure 3.

(A) Activated partial thromboplastin time (s) vs. plasma concentration of AR-H067637 (μmol/L); (B) Ecarin clotting time (s) vs. plasma concentration of AR-H067637 (μmol/L).

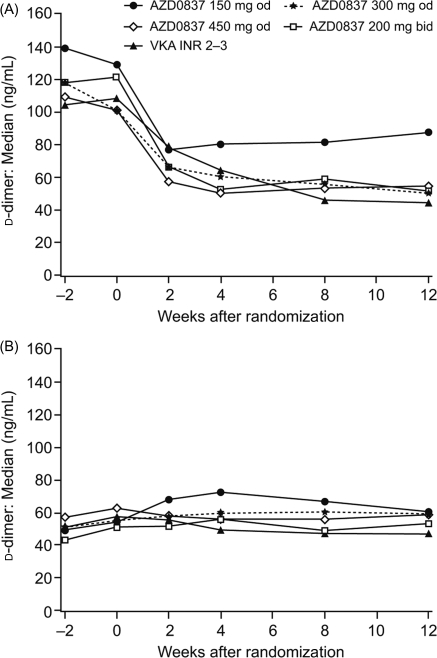

Median fibrin d-dimer levels during the first 12 weeks of treatment are shown in Figure 4A and B for VKA-naïve patients and VKA pre-treated patients, respectively. Results after 12–36 weeks on treatment are summarized in Table 4. The d-dimer levels showed large variability, the distribution was skewed, and many values were below ULN both before and during treatment. In VKA-naïve patients, fibrin d-dimer decreased in all treatment groups, with comparable changes in median fibrin d-dimer levels seen in the 300 mg od, 450 mg od, and 200 mg bid treatment groups compared with VKA. Levels of fibrin d-dimer in the VKA pre-treated patients started and remained low following treatment with AZD0837 and VKA.

Figure 4.

d-Dimer level by treatment and time in (A) vitamin K antagonist (VKA)-naïve patients and (B) VKA pre-treated patients.

Table 4.

Median plasma concentration and interquartile range in ng/mL of fibrin d-dimer at baseline and after 12 to 36 weeks on treatment

| Baseline | 12 weeks | 20 weeks | 28 weeks | 36 weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VKA-naïve patients | |||||

| AZD0837 150 mg od | 139.3 (72.5–224.6), n = 46 | 88.0 (38.8–126.4), n = 37 | 69.6 (44.0–97.4), n = 26 | 74.4 (46.0–114.0), n = 18 | 72.4(29.4–223.2), n = 7 |

| AZD0837 300 mg od | 117.7 (80.0–261.8), n = 41 | 50.0 (31.1–83.0), n = 32 | 60.6 (31.5–119.9), n = 23 | 51.1 (33.1–120.0), n = 15 | 69.8 (48.3–86.5), n = 6 |

| AZD0837 450 mg od | 109.3 (60.4–326.0), n = 39 | 54.9 (34.3–95.7), n = 37 | 58.1 (38.8–92.0), n = 29 | 55.7 (27.1–122.8), n = 22 | 43.7 (20.8–105.8), n = 5 |

| AZD0837 200 mg bid | 118.0 (73.7–204.6), n = 49 | 51.6 (30.1–75.0), n = 43 | 56.6 (39.5–85.4), n = 35 | 56.0 (38.9–89.7), n = 20 | 58.0 (41.5–103.0), n = 8 |

| VKA (INR 2.0–3.0) | 104.6 (61.2–232.4), n = 94 | 44.6 (27.5–74.1), n = 87 | 47.6 (27.5–75.3), n = 72 | 48.7 (36.8–74.1), n = 47 | 51.1 (34.7–70.3), n = 18 |

| VKA pre-treated patients | |||||

| AZD0837 150 mg od | 48.6 (23.5–95.8), n = 116 | 60.8 (42.0–110.4), n = 104 | 63.3 (35.2–103.4), n = 72 | 73.4 (40.4–130.2), n = 49 | 68.2 (55.5–244.5), n = 25 |

| AZD0837 300 mg od | 50.9 (29.5–100.6), n = 110 | 58.0 (37.4–103.4), n = 98 | 69.4 (43.7–109.6), n = 79 | 61.3 (36.1–105.8), n = 48 | 69.4 (44.8–92.1), n = 23 |

| AZD0837 450 mg od | 57.1 (24.1–117.6), n = 110 | 59.2 (32.8–113.0), n = 95 | 60.5 (32.6–123.1), n = 73 | 58.8 (38.6–100.2), n = 50 | 70.0 (28.1–118.2), n = 23 |

| AZD0837 200 mg bid | 43.1 (22.6–83.7), n = 110 | 53.2 (36.0–80.1), n = 89 | 52.5 (31.3–86.6), n = 69 | 56.1 (37.0–86.8), n = 45 | 60.0 (29.6–104.8), n = 22 |

| VKA (INR 2.0–3.0) | 51.5 (27.7–105.8), n = 215 | 47.2 (25.1–79.8), n = 211 | 49.1 (25.5–75.4), n = 164 | 46.3 (27.3–85.1), n = 120 | 59.2 (33.9–114.4), n = 60 |

INR, international normalized ratio; VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

Discussion

In this Phase II dose-guiding study, we investigated the safety, tolerability, and pharmacodynamic efficacy of four doses of an extended-release formulation of the oral anticoagulant AZD0837 in the AF population. This was an exploratory study and conclusions are therefore based on descriptive statistics rather than formal statistical testing. There was a trend towards less bleeding with the 150 mg od and 300 mg od doses of AZD0837 compared with VKA. Furthermore, the proportion of patients with serious AEs in the 150 mg od and 300 mg od dose group was lower than with the two higher doses of AZD0837 and similar or lower compared with VKA. An anticoagulant effect was seen with all doses of AZD0837. All doses of AZD0837 suppressed fibrin d-dimer levels in VKA-naïve patients, but the 150 mg dose appeared to decrease d-dimer to a lesser extent than higher doses. Based on this assessment of safety, tolerability, and pharmacodynamics, AZD0837 300 mg od was regarded as the most favourable dose used in this study.

Bleeding events occurred with an overall low frequency and with few major bleeding events. Numerically fewer major and clinically relevant minor bleeding events were reported in the AZD0837 150 mg od and 300 mg od groups compared with the AZD0837 450 mg od, 200 mg bid and VKA groups, in the whole cohort. Most major bleedings were reported among the VKA-naïve patients. This group would be expected to be more sensitive to anticoagulant-related bleeding events, given that prior VKA takers would be more ‘anticoagulant-tolerant’, since any tendency to bleeding would have become apparent prior to entering this trial.13

Overall, treatments were well tolerated, with a similar proportion of patients with any AE in each treatment group. A somewhat higher incidence of gastrointestinal disorders with AZD0837, e.g. diarrhoea and flatulence, was observed both in this study and also in a previous study.12 The proportion of patients withdrawing due to AEs was higher in the AZD0837 groups than in the VKA group. However, it should be considered that the study was open to investigational drug allocation, and more withdrawals on AZD0837 could be expected because of more stringent withdrawal criteria in the protocol for this new drug and because of investigator bias to more likely withdraw a new treatment than a well-known routine treatment. No difference with respect to serious AEs of a cardiac origin between AZD0837 and VKA was observed. While the study was not powered to look at stroke and systemic embolic events, few events were reported.

As previously observed in patients receiving AZD0837,12 an increase of approximately 10% in mean serum creatinine was noted in this study. A study in elderly healthy volunteers14 showed that AZD0837 has no effect on glomerular filtration rate as assessed by iohexol clearance. The effect on creatinine associated with AZD0837 is suggested to be caused by an inhibition of active renal tubular creatinine secretion via the human organic cation transporter 2 protein, as seen in in vitro studies. Inhibition of active tubular secretion has been observed with other drugs such as cimetidine. In the current study, cystatine C, which is a more sensitive marker for glomerular filtration rate than creatinine,15 and the urine albumin:creatinine ratio was not significantly changed with AZD0837 (data not shown). The elevation in serum creatinine is unlikely to pose a clinical problem given its modest magnitude and since it does not appear to be related to an effect on glomerular filtration rate.

After administration of another oral direct thrombin inhibitor, ximelagatran (active form, melagatran), an increase in ALT was observed;16,17 therefore liver function was extensively followed in this study. The incidence of ALT ≥3×ULN for AZD0837 patients combined was 2.3% and for VKA patients was 1.6%. This may appear high in both groups (usually less than 1% for VKA), but may be explained by a fairly large proportion of patients with high ALT levels at baseline, as the exclusion criterion allowed ALT elevations up to 3×ULN in contrast to, for example, the Phase II study of stroke prevention in AF with the oral direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran etexilate,18 where a >2×ULN limit was used as an exclusion criterion.18 Results of the present study indicate no evidence of a clinically relevant liver signal with AZD0837 at any of the doses investigated, in agreement with previous findings with the immediate-release formulation of AZD083712 and the Phase II study with dabigatran etexilate.18 Together, these results suggest that the liver function abnormalities leading to the withdrawal of ximelagatran from the market do not appear to be a class effect of oral direct thrombin inhibitors.

AZD0837 is rapidly metabolized to the active form, AR-H067637, which has a half-life of approximately 9–14 h in healthy volunteers.11 At the studied doses, the range of median plasma concentrations of AR-H067637, predominately taken at pre-dose, was approximately 0.3–0.6 µmol/L. The anticoagulant effect was demonstrated by the observed prolongation of APTT and ECT coagulation times. Activated partial thromboplastin time was increased by approximately 50%, while the more sensitive ECT assay increased three- to four-fold compared with baseline. The interpatient variability in exposure of the active form was moderate. Relatively small fluctuations during a dosing interval were observed with both od and bid dosing of AZD0837 in the extended-release formulation. In each dose group, the plasma exposure of the active form and the level of anticoagulation assessed as APTT and ECT were stable during the 9-month treatment period.

Fibrin d-dimer, used as a marker of thrombogenicity, was analysed in the study to gain more knowledge of the antithrombotic properties of the drug, and for dose guidance. The use of fibrin d-dimer is not an established surrogate for clinical efficacy in AF. Although the biomarker has limitations, increased d-dimer levels have been detected in patients when changing from sinus rhythm to paroxysmal AF.19 Additionally, even though high levels of fibrin d-dimer are not necessarily caused by fibrin formation in a thrombus in the atrium of the heart, low levels could be helpful in excluding the presence of left atrial appendage thrombi.20 Measurement of d-dimer levels has shown large variability, which was also observed in the present study. In spite of its limitations and being a non-standardized indirect marker of thrombogenesis, the concept has previously been used to test the benefits on thrombogenesis of different antithrombotic regimens,7,18,21 and has been proposed in recent recommendations from a consensus conference organized by the German Atrial Fibrillation Competence NETwork and the European Heart Rhythm Association on outcome parameters for trials in AF.22 In the paper by Kamath et al., 7 indices of thrombogenesis (including d-dimer) and platelet activation were used to determine the effects of warfarin compared with aspirin plus clopidogrel combination therapy in a randomized trial. From that trial, it was concluded that warfarin suppressed biomarkers of thrombogenesis, whereas aspirin plus clopidogrel was ineffective, although some platelet-activated indices were suppressed. Kamath et al.7 concluded that aspirin plus clopidogrel therapy was unlikely to provide adequate thromboprophylaxis in AF patients, a clinical observation subsequently confirmed in the ACTIVE-W trial.8

In the present study, the overall proportion of patients in INR range 2.0–3.0 during weeks 6–36 was 57–68%. This is a good level of control compared with the real-life situation,23–25 and similar to that achieved in other clinical trials.18,26 However, it may still not be ideal since a better protection from vascular events has been shown in patients where INR was controlled >65% of the time.26 This illustrates that keeping VKA in range is a challenge even in clinical trials.

We found that AZD0837 at doses of 300 mg od, 450 mg od, and 200 mg bid suppressed fibrin d-dimer levels to a similar extent as VKA (INR 2.0–3.0) in VKA-naïve patients, whereas 150 mg od appeared to cause less suppression of fibrin d-dimer levels compared with VKA. In the VKA-naïve patients, there were reductions from baseline for all dose groups of AZD0837 and VKA. Because of the repeated measurements every second week, the onset of effect during the first 8 weeks was clearly demonstrated in the VKA-naïve patients. The patients already on VKA treatment at enrolment had suppressed d-dimer already and therefore could not, as expected, be further suppressed. These observations suggest that AZD0837 needed to be at an exposure corresponding to the 300 mg od dose in this study or above to have similar therapeutic efficacy to VKA in reducing thrombogenesis amongst AF patients. Together with information from previous clinical studies, data from this dose-guiding study are used in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modelling work for dose selection.

This study is limited by the relatively short period of exposure of AZD0837. However, many of the AZD0837-treated patients who completed the current protocol continued in an extension trial (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00645853), which will give additional data on prolonged administration of AZD0837.

In conclusion, the results of this Phase II dose-guiding study show that all tested doses of AZD0837 were generally well tolerated, and suggest that AZD0837 at an exposure corresponding to the 300 mg od dose provides a similar suppression of thrombogenesis at a potentially lower bleeding risk compared with dose-adjusted VKA.

Funding

Funding is provided by AstraZeneca.

Conflict of interest: the clinical study presented here was sponsored by AstraZeneca.

A.L.P., E.C.J., U.E., and K.F.C.W. are employees of the sponsor with stock ownership. G.Y.H.L. acted as the Chair of the Executive Steering Committee, and has received funding for consultancy, meetings, and symposia from AstraZeneca. L.H.R. is a member of the Executive Steering Committee and has received funding for consultancy from AstraZeneca. S.B.O. is a member of the Executive Steering Committee, and is a shareholder in AstraZeneca and has received financial support for clinical research from the company.

Acknowledgements

Executive Steering Committee

G.Y.H.L. (University of Birmingham Centre for Cardiovascular Sciences, City Hospital, Birmingham, UK); L.H.R. (Department of Cardiology, Aalborg University Hospital, Aalborg, Denmark); S.B.O. (Department of Cardiology, Lund University Hospital, Sweden); A.L.P. (AstraZeneca, Mölndal, Sweden); E.C.J. (AstraZeneca, Mölndal, Sweden); A. Jaremo (AstraZeneca, Mölndal, Sweden).

Steering Committee

G.Y.H.L. (UK); L.H.R. (Denmark); S.B.O. (Sweden); E. Pilger (Austria); M. Lengyel (Hungary); A. Tveit (Norway); M. Kochmański (Poland); E. Panchenko (Russia); V. Frykman (Sweden); A.L.P. (AstraZeneca, Sweden); E.C.J. (AstraZeneca, Sweden); A. Järemo (AstraZeneca, Sweden).

Data Safety Management Board

L. Wilhelmsen (Sweden); A. Berggren (AstraZeneca, Sweden); L. Frison (AstraZeneca, Sweden); H. Ericsson (AstraZeneca, Sweden).

Contributing Centres (Principal Investigators)

Austria—P.A. Kyrle; M. Wolzt; E. Pilger; H. Brussee; O. Pachinger; M. Pichler.

Denmark—L.H.R.; T. Melchior; R. Sykulski; P. Clemmensen; S. Rasmussen; L. Frost; K.E. Pedersen; K. Dodt; T. Jakobsen; K. Skagen; T. Nielsen; L. Fog.

Great Britain—G.Y.H.L.; S. Saltissi; G. Ford; A. Sharma; K. Beatt; P. Stubbs.

Hungary—K. Sándori; M. Hetey; M. Sereg; C. Kerekes; A. Pálinkás; A. Katona; L. Illyés; Á. Kalina; A. Jánosi; J. Hankóczy; A. Czigány; A. Kovács; C. Király.

Ireland—R. Sheahan; P. Crean.

Norway—A. Tveit; R. Retzius; B. Øie; K. Risberg; H. Istad; S. Elle; A. Tandberg; K. Langaker; K. Valnes; T. Wessel-Aas; P.A. Sirnes; E. Skjegstad; J. Sandvik; F. Strekerud; A. Svilaas; J. Gronert; L. Gullestad.

Poland—M. Kochmanski; P. Miękus; M. Zieliński; B. Kuśnierz; T. Waszyrowski; J. Bortkiewicz; M. Krzciuk; J. Frycz; J. Rekosz; W. Figatowski; M. Krauze-Wielicka; D. Wojciechowski; A. Ługowski; M. Bronisz; K. Niezgoda; R. Ściborski.

Russian Federation—G.P. Arutyunov; S. Tereschenko; T. Novikova; S. Shustov; M. Bubnova; V. Kukharchuk; I. Chazova; E. Panchenko; S. Golitzyn; M. Kotelnikov; B. Tatarskiy; A. Galyavich; E. Shlyakhto; E. Oshchepkova; J. Karpov; A. Fursov.

Sweden—V. Frykman; P. Platonov; A. Ebrahimi; K. Pedersen; C.-J. Lindholm; F. Al-Khalili; T. Jonson; R. Svensson; F. Jacobsson.

Study Project Team

A. Järemo (AstraZeneca, Sweden); B. Boberg (AstraZeneca, Sweden); E. Brann (AstraZeneca, Sweden); E.C.J. (AstraZeneca, Sweden); M. Andersson (AstraZeneca, Sweden); A.L.P. (AstraZeneca, Sweden).

We thank Barbro Boberg and Andreas Järemo for their contribution in planning and conducting the study. Editorial support was provided by Dr Cindy Macpherson, MediTech Media Ltd, UK and was funded by AstraZeneca.

References

- 1.Lip GY, Lim HS. Atrial fibrillation and stroke prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:981–993. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Halperin JL, Le Heuzey JY, Kay GN, Lowe JE, Olsson SB, Prystowsky EN, Tamargo JL, Wann S Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; Committee for Practice Guidelines, European Society of Cardiology; European Heart Rhythm Association; Heart Rhythm Society. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation-executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation) Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1979–2030. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Atrial Fibrillation: National Clinical Guideline for Management in Primary and Secondary Care. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansell J, Hirsh J, Poller L, Bussey H, Jacobson A, Hylek E. The pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(Suppl. 3):204S–233S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.204S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choudhury A, Goyal D, Lip GY. Ximelagatran. Drugs Today (Barc) 2006;42:3–19. doi: 10.1358/dot.2006.42.1.893611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taggar JS, Lip GY. Anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation: the trials and tribulations of keeping within therapeutic range. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:1455–1458. doi: 10.1185/030079908x301875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamath S, Blann AD, Chin BS, Lip GY. A prospective randomized trial of aspirin-clopidogrel combination therapy and dose-adjusted warfarin on indices of thrombogenesis and platelet activation in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:484–490. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01984-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connolly S, Pogue J, Hart R, Pfeffer M, Hohnloser S, Chrolavicius S, Pfeffer M, Hohnloser S, Yusuf S ACTIVE Writing Group of the ACTIVE Investigators. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1903–1912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68845-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pehrsson S, Elg M. The antithrombotic effect of AR-H067637, the active form of the novel oral direct thrombin inhibitor AZD0837, in rat models of arterial and venous thrombosis. (Abstract) J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl. 2):P-W-637. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deinum J, Mattssona C, Inghardt T, Elg M. Biochemical and pharmacological effects of the direct thrombin inhibitor AR-H067637. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:1051–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cullberg M, Wåhlander K, Jansson SO, Nyström P, Lönnerstedt C, Berggren A. Safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor AZD0837 in young healthy volunteers. (Abstract 206) Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;101:130. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsson B, Rasmussen LH, Tveit A, Jensen E, Wessman P, Panfilov S, Ekdal HD, Wahlander K. Safety and tolerability of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor AZD0837 in prevention of stroke and other thromboembolic complications associated with atrial fibrillation (AF). (Abstract) J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl. 2):O-W-053. doi: 10.1160/TH09-07-0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, O'Donnell M, Pogue J, Yusuf S. Challenges of establishing new antithrombotic therapies in atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2007;116:449–455. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.695163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schützer KM, Svensson M, Dellstrand M, Björck K, Wåhlander K. Effect of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor AZD0837 on glomerular filtration rate in elderly healthy subjects. (Abstract) J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl. 2):P-W-668. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fliser D, Ritz E. Serum cystatin C concentration as a marker of renal dysfunction in the elderly. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:79–83. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.20628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diener HC Executive Steering Committee of the SPORTIFF III V Investigators. Stroke prevention using the oral direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Pooled analysis from the SPORTIF III and V studies. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;21:279–293. doi: 10.1159/000091265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee WM, Larrey D, Olsson R, Lewis JH, Keisu M, Auclert L, Sheth S. Hepatic findings in long-term clinical trials of ximelagatran. Drug Saf. 2005;28:351–370. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200528040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ezekowitz MD, Reilly PA, Nehmiz G, Simmers TA, Nagarakanti R, Parcham-Azad K, Pedersen KE, Lionetti DA, Stangier J, Wallentin L. Dabigatran with or without concomitant aspirin compared with warfarin alone in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (PETRO Study) Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:1419–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang TL, Hung CR, Chang H. Evolution of plasma D-dimer and fibrinogen in witnessed onset of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Cardiology. 2004;102:115–118. doi: 10.1159/000078410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habara S, Dote K, Kato M, Sasaki S, Goto K, Takemoto H, Haseqawa D, Matsuda O. Prediction of left atrial appendage thrombi in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2217–2222. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li-Saw-Hee FL, Blann AD, Lip GY. Effects of fixed low-dose warfarin, aspirin-warfarin combination therapy, and dose-adjusted warfarin on thrombogenesis in chronic atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2000;31:828–833. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.4.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirchhof P, Auricchio A, Bax J, Crijns H, Camm J, Diener HC, Goette A, Hindricks G, Hohnloser S, Kappenberger L, Kuck KH, Lip GY, Olsson B, Meinertz T, Priori S, Ravens U, Steinbeck G, Svernhage E, Tijssen J, Vincent A, Breithardt G. Outcome parameters for trials in atrial fibrillation: recommendations from a consensus conference organized by the German Atrial Fibrillation Competence NETwork and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2007;9:1006–1023. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker AM, Bennett D. Epidemiology and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1365–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hylek EM, Go AS, Chang Y, Jensvold NG, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE. Effect of intensity of oral anticoagulation on stroke severity and mortality in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1019–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young L, Ockelford P, Harper P. Audit of community-based anticoagulant monitoring in patients with thromboembolic disease: is frequent testing necessary? Intern Med J. 2004;34:639–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connolly SJ, Pogue J, Eikelboom J, Flaker G, Commerford P, Franzosi MG, Healey JS, Yusuf S ACTIVE W Investigators. Benefit of oral anticoagulant over antiplatelet therapy in atrial fibrillation depends on the quality of international normalized ratio control achieved by centers and countries as measured by time in therapeutic range. Circulation. 2008;118:2029–2037. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.750000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]