Abstract

Objectives

There have been few studies exploring the discriminative stimulus effects of inhalants and none that have trained an interoceptive discrimination using the inhaled route. This study was designed to assess if it was possible to train an inhaled toluene discrimination. The second objective was to determine whether the discrimination was based on interoceptive or exteroceptive stimulus effects.

Methods

Eight B6SJLF1/J mice were trained to discriminate 10 min of exposure to 6000 ppm inhaled toluene vapor from air using a standard food-reinforced operant procedure.

Results

Toluene vapor produced robust, concentration dependent, discriminative stimulus effects with concentrations of 4000 ppm and higher producing full substitution. Substitution of inhaled toluene vapor for the training condition was exposure-time dependent. A minimum of 7 min of exposure to 6000 ppm was required to produce complete substitution. Injected i.p. toluene produced dose-dependent full substitution for inhaled toluene vapor. Both inhaled and i.p. ethylbenzene produced similar levels of partial substitution for 6000 ppm toluene vapor. Inhaled isoflurane vapor produced no substitution for toluene vapor.

Conclusions

These results show that a toluene vapor discrimination can be successfully trained in mice and the discrimination is selective for toluene compared to ethylbenzene and isoflurane. The results also suggest that the discrimination was likely to have been based primarily on interoceptive rather than exteroceptive stimulus effects.

Keywords: drug discrimination, toluene, ethylbenzene, isoflurane, inhalant, mice

1. Introduction

The abuse of inhalants is a serious social and medical problem both in the United States and worldwide. Although all age brackets report inhalant use, the prevalence of inhalant abuse is highest among children. The most recent data from the 2005 Monitoring the Future Study Survey found that 17% of 8th graders reported inhalant use at least once (Johnston et al. 2005). Despite the magnitude of the problem, the neural basis for the abuse-related acute behavioral effects of inhalants are poorly understood, especially at the high concentrations at which they are typically abused (Balster 1998).

The subjective effects of inhalants are one important aspect of their pharmacology that may be related to their abuse potential (Balster 1987). Unfortunately, with the exception of anesthetic gasses and volatile anesthetics, virtually all abused inhalants have known toxicity, especially at the high concentrations that are necessary to produce rapid, intoxicating effects. For instance, the OSHA ceiling air concentration at which the inhalant toluene is considered unsafe for any exposure duration is only 300 ppm (OSHA 1998) which is near the lower limit for detectable behavioral effects in rodents after short duration exposure (Bowen and Balster 1998; Bowen et al. 1996). Fortunately, the drug discrimination model in animals is highly predictive of a drug’s subjective effects in humans and may therefore be an extremely useful surrogate for understanding the neurochemistry underlying this aspect of inhalants effects, much as has been the case for many other classes of abused drugs (Balster 1991; Schuster and Johanson 1988).

Only two studies have trained inhalants themselves as interoceptive discriminative stimulus and both of these experiments used intrerperitoneal (i.p.) injections of the compound as a training stimulus, rather than administration via the route it is abused (i.e. inhalation). In the first of these studies, conducted in mice, 100 mg/kg i.p. toluene was trained as a discriminative stimulus (Rees et al. 1987c). Following training, substitution tests were conducted with inhaled toluene, i.p. pentobarbital and i.p. morphine. The results indicated that inhaled toluene concentrations of 1200 ppm and higher fully substituted for 100 mg/kg i.p. toluene. Pentobarbital also fully substituted for i.p. toluene, whereas morphine did not produce i.p. toluene-like responding. In rats trained to discriminate 100 mg/kg i.p. toluene from saline, inhaled toluene was not tested, but both methohexital and oxazepam produced only partial substitution for i.p. toluene (Knisely et al. 1990). In both of these studies, injected inhalants proved to be difficult to work with as training stimuli, due to their tissue damaging effects over repeated daily injection as well as an extremely lengthy training procedure. Further studies were never undertaken as a consequence (R.L. Balster, unpublished observation).

Given the difficulties of injecting inhalants and the fact that they are not commonly administered in that manner the best route for examining the interoceptive discriminative stimulus effects of inhalants is probably by inhalation. Most of these technical difficulties associated with inhalational delivery, such as reproducibly producing and accurately measuring inhalant concentrations, choosing behaviorally active inhalant concentrations and assessing relevant exposure durations have been overcome (Balster 1987). A few studies have utilized these techniques to test for cross substitution of inhalants in animals trained to discriminate injected drugs from vehicle. The general conclusion of these experiments is that a subset of inhalants have discriminative stimulus effects that share some similarity to ethanol, benzodiazepines and barbiturates (Bowen and Balster 1997; Bowen et al. 1999; Rees et al. 1987a; Rees et al. 1987b; Shelton and Balster 2004). The data from these cross-substitution studies are valuable and suggest that GABAA receptor positive modulation and perhaps to a lesser degree NMDA receptor antagonism may play a role in the discriminative stimulus effects of inhalants. However, there are reasons to hypothesize testing inhalants in animals trained to discriminate other drugs from vehicle may alone be insufficient to completely characterize the discriminative stimulus effects of inhalants.

In many respects the discriminative stimulus effects of the few inhalants that have been examined to date bear considerable similarity to ethanol (Grant, 1994; 1999). Ethanol’s discriminative stimulus has been repeatedly shown to be a mixed stimulus composed of strong GABA-positive modulator and NMDA antagonist-like effects as well as some less pronounced serotonergic effects (Grant et al. 1991, 1997; Sanger 1993; Shelton 2004; Shelton and Balster, 1994). Given the proper training procedure any of these three components of ethanol’s mixed stimulus is sufficient to elicit full substitution in ethanol trained animals. For example, any of a number of GABA-positive modulators and NMDA antagonists will completely substitute in animals trained to discriminate ethanol from vehicle (De Vry and Slangen 1986; Kostowski and Bienkowski 1999; Shelton and Grant 2002). However, when ethanol is tested in animals trained to discriminate those same GABA positive modulators or NMDA antagonists from vehicle, ethanol produces little if any substitution (Balster et al. 1992; Butelman et al. 1993; De Vry and Slangen 1986; Herling et al. 1980). This unique pattern of results has been termed asymmetric or asymmetrical substitution. If inhalants are also effectively a mixed discriminative stimulus resulting from effects at multiple receptors, as seems likely based on the available data, they too may have asymmetrical substitution profiles and therefore the only means of completely unraveling their discriminative stimulus effects is by training the inhalants themselves as discriminative stimuli.

Another concern with training inhalants as discriminative stimuli is their pronounced odor and local irritant properties. When the drug discrimination paradigm was first being differentiated from the state-dependent learning field it was unclear whether the discriminative stimulus effects of injected drugs which could control behavior were based on CNS activity or upon these exteroceptive stimulus effects. A number of studies conducted in the 1970’s and 1980’s consistently showed that the discriminative stimulus effects of injected drugs, even those which possess exteroceptive stimulus effects, were almost certainly based on the drug’s activity in the CNS rather than peripheral cues like change in heart rate (Johansson and Jarbe 1976; Kubena and Barry 1969; Schechter 1973; Schechter and Rosecrans 1971). These studies and others showed that in the absence of strong peripheral cues, interoceptive cues of injected drugs play a primary role in controlling behavior. However, inhalants present a unique challenge in drug discrimination research because they have very pronounced odors and local irritant effects even at concentrations that are likely to be well below those which produce behavioral effects on measures such as locomotor performance (Bowen and Balster 1998; Moser and Balster 1986). As such either the interoceptive or the exteroceptive cues of inhalants could potentially be used to direct behavior and one component if of sufficient intensity might overshadow the weaker component.

A few studies have explicitly examined the consequences of exteroceptive and interoceptive stimulus compounding in drug discrimination (see Jarbe et al., 1989 for review). In one rodent study, exteroceptive visual+tactile cues combined with interoceptive drug cues produced by d-amphetamine were trained versus the same visual+tactile cues combined with pentobarbital (Duncan, 1986). One group of rats was trained with high drug doses. In a second group of rats the training drug doses were relatively low. The visual+tactile stimulus were identical in both groups. The study found that both interoceptive and exteroceptive cues could control behavior. However, when the drug training doses were high, the rats attended more strongly to the interoceptive drug cues and when the training drug doses were low, the rats attended more strongly to the exteroceptive visual+tactile cues. These data indicate that when a compound cue composed of an interoceptive drug stimulus and exteroceptive stimulus are combined the discrimination learned is based on the relative salience of the interoceptive versus exteroceptive cues. If the interoceptive cues are of sufficient intensity they will not be overshadowed and alone will be capable of controlling behavior. However, if the interoceptive stimuli are weak relative to the exteroceptive stimuli they will control behavior less strongly (Jarbe et al., 1989).

The first goal of the present experiment was to determine if a prototypic abused inhalant, toluene, could be trained as a discriminative stimulus via it’s commonly abused inhalation route. Compounds with strong odors can easily be trained as discriminative stimuli in rodents so the ability to train such a discrimination was not really in doubt (Bodyak and Slotnick 1999). The second and more critical goal of the present study was to determine what aspect of toluene’s discriminative stimulus, its interoceptive effects, exteroceptive stimulus properties or both were responsible for maintaining the discrimination.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Eight B6SJLF1/J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) served as subjects. This strain is a F1 hybrid derived from C57BL6/J female and SJL/J male parents which has been used previously in our laboratory for drug discrimination studies (Shelton et al., 2004). The mice were 9-10 weeks old at the start of discrimination training. The mice were individually housed on a 12 hr light/dark cycle (lights on 7 AM) and allowed to acclimate to the laboratory for a period of one week prior to the start of training. To promote operant responding the mice were fed 3-5 g of standard rodent chow (Harlan, Teklad, Madison, WI) once daily after the daily test session. Feeding was adjusted to maintain a healthy, stable weight of between 25-31g for the duration of the study. Feeding was increased if the animals showed any signs of adverse consequences resulting from this mild food restriction.

2.2 Drugs

HPLC grade toluene and ethylbenzene were purchased from Aldrich Chemicals (Milwaukee, WI). Isoflurane, USP (Isoflo) was purchased from Abbott Laboratories (North Chicago, IL). For injection, toluene and ethylbenzene was suspended in Liposyn II – 20% fat emulsion (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) to produce a constant injection volume of 10 ml/kg of body weight. The toluene/Liposyn and ethylbenzene/Liposyn suspension was vortexed for 30 seconds immediately before being drawn into a syringe and rapidly injected.

2.3 Apparatus

Drug discrimination sessions were conducted in standard mouse operant conditioning chambers (Med-associates model ENV-307AW, St. Albans, VT). Each chamber was equipped with two ultra-sensitive optically switched levers (Med-associates model ENV-310M) on the front wall. Above each lever was a yellow LED stimulus lamp. Equidistant between the levers was a recessed receptacle into which a 0.1 ml liquid dipper cup could be elevated via an electrically-operated dipper mechanism. A single 5 watt houselight was located at the top center of the chamber rear wall. The operant conditioning chambers were individually housed in sound-attenuating and ventilated cubicles. Drug discrimination schedule conditions and data recording were accomplished using a Med-associates interface and Med-PC version 4 control software running on a PC-compatible computer (Med-Associates, St. Albans, VT). The milk solution reinforcer consisted of 25% sugar, 25% nonfat powdered milk and 50% tap water (by volume).

The static vapor chambers and general procedures used to expose the mice to toluene vapors prior to drug discrimination testing have been described in detail in many reports (e.g. Bowen and Balster 1996; 1997). Briefly, each chamber consisted of a 26-liter cylindrical glass bell jar with a clear acrylic lid with an attached fan motor. A foam rubber gasket was fixed to the rim of the bell jar to insure a tight seal. A drive shaft with sealed bearings extended through the lid into the chamber where it was connected to a plastic fan blade. Directly below the fan blade was a suspended wire mesh platform to which a filter paper disk was attached. Toluene and ethylbenzene vapor were produced by injecting liquid onto the filter paper using a gas-tight glass microliter syringe. The internal fan was then activated which rapidly volatilized the liquid and produced vapor. Since the inhalation chambers were sealed and of a fixed volume, the amount of liquid necessary to produce a given vapor concentration could accurately be calculated using the ideal gas law equation for room temperature (Nelson 1971). It was not deemed necessary to make any temperature or atmospheric pressure corrections to the calculations since normal laboratory variability in these factors were predicted to have a 1% or less effect on the parts per million (ppm) of vapor produced by a given volume of liquid toluene or ethylbenzene. The rise time and stability of chamber toluene vapor concentrations were verified prior to the start of the study by using a vacuum pump to recirculate the chamber air/toluene vapor mixture through a single wavelength monitoring infrared spectrometer set at 13.9μm (Miran 1A, Foxboro Analytical, North Haven, CT).

Prior to vapor exposure each mouse was weighed and placed into a separate, ventilated, 7.5 cm diameter × 8 cm tall, cylindrical stainless steel container (Oneida, Oneida, NY). The stainless steel containers were then inserted into the inhalation chamber and the lid sealed. The calculated volume of liquid to produce a given chamber concentration was injected via a stoppered port in the chamber lid onto the filter paper. The fan was then activated, which rapidly volatilized the liquid and distributed the vapor throughout the chamber. Air exposure sessions were identical to those with vapor except that no liquid toluene or ethylbenzene were injected into the chamber.

2.4 Discrimination training

After the animals were acclimated to the laboratory, daily (M-F) 15-min training sessions were initiated. The mice were first trained to press one lever under a fixed ratio 1 response (FR 1) schedule. Upon completion of the FR requirement, a 0.1 ml liquid dipper cup was elevated into the dipper receptacle for 3 sec. Responses occurring while the dipper was elevated did not count toward completion of the next ratio requirement. Responding on the inactive lever reset the FR requirement on the correct lever. The animals were then trained to respond on the opposite lever under the FR 1 schedule. During experimental sessions, both stimulus lights and the house light were illuminated for the duration of the session. Once the animals were reliably responding at FR 1 during the 15-min session, the operant session length was decreased to 5 min in duration and behavior was again allowed to stabilize before drug discrimination training sessions were initiated. During each 5 min discrimination training session, one of the two levers was designated as correct. The correct lever was determined by whether the subject received a 10 min exposure to 6000 ppm toluene vapor or an identical 10 min exposure in the inhalation chamber to air. Completion of the FR requirement on the correct lever resulted in 3 sec of dipper availability. The lever corresponding to toluene vapor and air exposure remained fixed for the duration of the study for a given animal but was counterbalanced across mice. Exposures were presented according to a double alternation schedule (i.e. two toluene vapor days followed by two air days). Responses emitted on the incorrect lever were recorded and reset the FR requirement on the correct lever. Over the course of 10-20 sessions, the response requirement was increased to FR 12. These training conditions were in effect for the remainder of the study. Animals were determined to have acquired the 6000 ppm toluene vapor and air discrimination when the first FR was completed on the correct lever, prior to the completion of a FR on the incorrect lever, in 8 out of 10 consecutive sessions. Additionally, the mice were required to emit greater than 80% of responses on the correct lever during all 10 of these sessions.

2.5 Substitution Test Procedure

Following acquisition of the 6000 ppm toluene vapor and air discrimination, substitution tests were conducted on Tues and Fri, providing that the mice continued to exhibit accurate stimulus control on the Mon, Wed and Thurs training sessions. Test sessions were suspended if an animal did not emit the first FR on the correct lever and produce greater than 80% correct-lever responding during all training sessions since the last test session. If a mouse did not meet the criteria for testing on a particular Tues or Fri, it received additional daily toluene vapor and air training sessions until the correct first FR, as well as greater than 80% correct-lever responding, was emitted for a minimum of 3 consecutive training sessions at which point it was again returned to the Tues and Fri testing, Mon, Wed, Thurs training schedule. Between substitution tests, the double alternation sequence of toluene vapor and air training sessions was continued. Substitution tests with toluene, ethylbenzene and isoflurane vapor, except those assessing exposure duration, were preceded by a 10-min exposure to a single concentration of vapor. The animal was then immediately removed from the exposure chambers and placed into the operant chamber for a 5-min drug discrimination test session. Substitution test sessions examining injected toluene or ethylbenzene were initiated by a toluene/Liposyn or ethylbenzene/Liposyn injection, followed by a 10-min air exposure period in the vapor chamber and a subsequent 5-min substitution test session. The control test for injected toluene or ethylbenzene was i.p. Liposyn vehicle, a 10-min air exposure and a 5-min substitution test. On test days, both levers were active and completion of a FR requirement on either lever resulted in dipper presentation. Vapor concentrations or injections were administered in an ascending order. Each condition was tested once without regard for the prior days training condition (toluene vapor or air). Prior to each concentration or dose-effect curve control test sessions were conducted with 6000 ppm toluene vapor and air.

2.6 Data analysis

Toluene vapor and air-lever responses and dipper presentations were recorded for each animal. Group means (± SEM) were calculated for both percentage toluene vapor and air-lever responding and response rate at each drug dose or concentration. During drug discrimination tests, the percentage of responses emitted on the toluene vapor-appropriate lever during the entire test session and lever on which the first fixed ratio (FFR) was completed were used as measures of the ability of a test condition to substitute for the 6000 ppm toluene vapor training concentration. The FFR was defined as the first lever upon which an individual animal completed a consecutive FR12. FFR data was expressed as number of mice responding on the toluene lever compared to total number of mice that completed at least one consecutive fixed-ratio value. Any vapor concentration or injected dose that suppressed response rates to the extent that the animal did not complete a FFR resulted in the exclusion of that mouse’s data point from the group lever-selection and FFR analysis, although that animal’s data was included in the response rate determination. Response rate for each test concentration or dose were expressed in responses/second. A criteria of 80% or greater toluene vapor-appropriate responding was selected to indicate full substitution for the 6000 ppm toluene vapor training concentration. Mean toluene vapor-lever responding between 20% and 79% was defined as partial substitution. Mean toluene vapor-lever responding of less than 20% was considered to be evidence of no substitution for 6000 ppm toluene vapor. When possible EC50 and ED50 values (and 95% confidence limits) for 6000 ppm toluene vapor-lever selection were calculated based on the linear portion of each mean dose-effect curve. Calculations were performed using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet based on SAS Pharm/PCS version 4 (Tallarida and Murray 1986).

3. Results

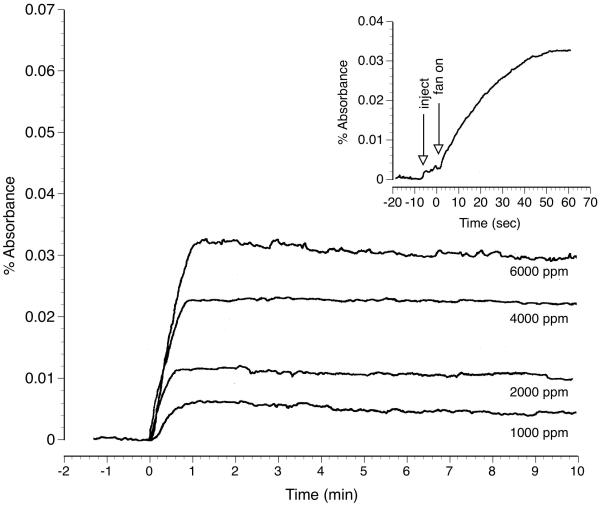

At the outset of the study the time necessary to reach chamber concentration equilibrium following liquid toluene introduction as well as static chamber integrity were assessed. IR spectrometer absorbance values for 1000, 2000, 4000 and 6000 ppm toluene vapor over 10 min are shown in figure 1. Chamber absorbance was approximately proportional to toluene liquid injection volume and IR absorbance values were nearly identical to those reported in an earlier study (Moser and Balster 1981). Vapor concentrations reached peak levels within the first minute after activating the internal fan (figure 1 inset) and remained stable for at least 10 min at all four concentrations.

Figure 1.

IR spectrometer plot showing exposure chamber air absorbance over a 10 min period following injection of liquid toluene volumes calculated to produce 1000, 2000, 4000 or 6000 ppm toluene vapor. Inset shows chamber air absorbance for 70 sec following the injection of liquid toluene calculated to produce 6000 ppm toluene vapor. Arrows mark the time at which toluene was injected as well as the time the internal fan was engaged.

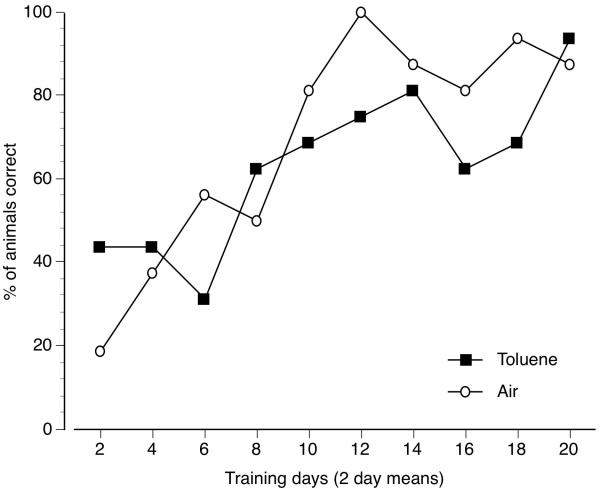

Figure 2 shows group discrimination accuracy as a function of training days. Animals were consider to be correct only if they emitted both a correct first FR and greater than 80% correct-lever responding for the entire session. Data are shown as two day group means for a given training stimulus (air or toluene vapor). Overall accuracy increased across test sessions in a similar linear pattern for both air and toluene vapor. It required a mean of 10 air training sessions and 14 toluene vapor training sessions before greater than 80% of mice met this daily criteria on any given pair of same condition training days. All eight mice acquired the 6000 ppm toluene vapor versus air discrimination. A mean of 25.9±2.8 total training sessions (19-44 session range) were required to reach overall acquisition criteria of 8 out of 10 consecutive sessions of successfully meeting the daily correct responding criteria.

Figure 2.

Percentage of mice meeting both the correct first fixed ratio and greater than 80% total training-appropriate lever responding requirements across 40 consecutive training sessions (20 air/20 toluene). Data points represent two days means for air (open circles) and 6000 ppm toluene vapor (closed squares).

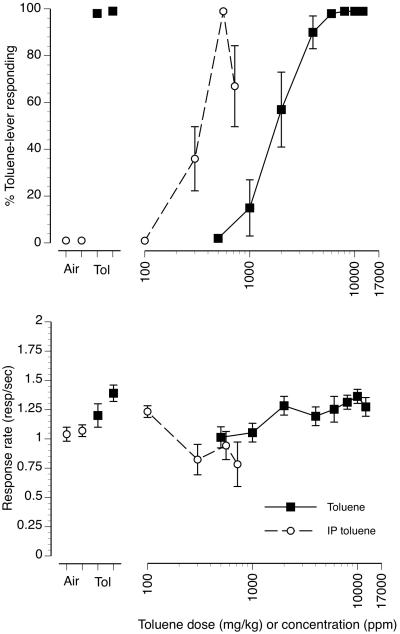

The upper panel of figure 3 (filled squares/solid line) shows the concentration-effect curve for substitution of increasing concentrations of toluene vapor for the 6000 ppm toluene vapor training concentration. The first fixed ratio (FFR) emitted on the toluene-appropriate lever for each concentration of inhaled toluene is shown in Table 1. Toluene vapor concentration-dependently substituted for the 6000 ppm training concentration with an EC50 value of 1792 ppm (CL: 1459-2200 ppm). The 500 and 1000 ppm toluene vapor concentrations produced less than 20% toluene-appropriate responding with only 1 of 8 mice emitting their FFR on the toluene lever at the 1000 ppm concentration (table 1). The 2000 ppm toluene vapor concentration produced 57% toluene-appropriate responding with 4 of 8 mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-appropriate lever. Toluene vapor concentrations of 4000, 6000, 8000, 10000 and 12000 ppm produced full substitution for the 6000 ppm toluene vapor training concentration. Six of eight mice emitted their FFR on the toluene lever at the 4000 ppm concentration and 8 of 8 mice emitted their first FFR on the toluene lever at 6000 ppm and greater.

Figure 3.

Concentration-effect curve for inhaled toluene vapor and dose-effect curve for injected toluene in 8 mice trained to discriminate 6000 ppm inhaled toluene from air. Points above Air represent the results of air (first open circle) and air + i.p. vehicle (second open circle) exposure control sessions. Points above Tol represent the results of toluene (first filled square) and i.p. toluene + air (second filled square) exposure control sessions. Mean (± SEM) percentages toluene-lever responding are shown in the upper panel for both inhaled (filled squares/solid line) and i.p. injected (open circles/dashed line) toluene. Mean (± SEM) response rates in responses per second for both inhaled (filled squares/solid line) and i.p. injected (open circles and dashed line) toluene as well as control sessions are shown in the bottom panel.

Table 1. Number of mice emitting the first fixed ratio (FFR) on the toluene-appropriate lever in each test session.

The data show the number of animals emitting their first fixed ratio (FFR) on the toluene-appropriate lever (first number) compared to the number of animals completing at least one full fixed ratio (second number). Data are shown for inhaled toluene, ethylbenzene and isoflurane as well as i.p. injected toluene and ethylbenzene.

| Concentration or dose | Toluene Inhaled |

Ethylbenzene Inhaled |

Isoflurane Inhaled |

toluene I.P. |

Ethylbenzene I.P. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air control | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/7 | 0/8 | 0/8 |

| Toluene control | 8/8 | 8/8 | 7/7 | 8/8 | 7/8 |

| 100 mg/kg | - | - | - | 0/8 | 0/8 |

| 300 mg/kg | - | - | - | 3/8 | 1/8 |

| 560 mg/kg | - | - | - | 7/8 | 4/8 |

| 720 mg/kg | - | - | - | 6/7 | 3/5 |

| 500 ppm | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0/7 | ||

| 1000 ppm | 1/8 | 0/8 | 0/7 | ||

| 2000 ppm | 4/8 | 0/8 | 0/7 | ||

| 4000 ppm | 6/8 | 1/8 | 0/7 | ||

| 6000 ppm | 8/8 | 3/8 | 1/7 | ||

| 8000 ppm | 8/8 | 6/8 | 1/6 | ||

| 10000 ppm | 8/8 | 7/8 | 0/6 | ||

| 12000 ppm | 8/8 | 5/8 |

The upper panel of figure 3 (open circles/dashed line) also shows the substitution of increasing doses of i.p. injected liquid toluene for the 6000 ppm toluene vapor training condition. Like toluene vapor, i.p. liquid toluene produced dose-dependent substitution for the toluene vapor training condition with an ED50 value of 344 mg/kg (CL: 298-399 mg/kg). The 100 mg/kg i.p. dose produced no toluene vapor-lever responding nor did any mice emit their FFR on the toluene-appropriate lever (Table 1). The 300 mg/kg dose produced 36% toluene-lever responding with 3 of 8 mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-appropriate lever. The 560 mg/kg dose produced 99% toluene vapor-lever responding with 7 of 8 mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-appropriate lever. An even greater dose of 720 mg/kg liquid toluene resulted in a decline to 67% in toluene vapor-appropriate responding with FFR being emitted on the toluene lever in 6 of the 7 mice that completed at least one fixed ratio at that dose. The four leftmost points in the top panel of figure 3 are control test sessions conducted prior to each test curve. Control tests following 10 min of exposure to air or air + the i.p. toluene vehicle (first and second open circles, respectively) produced no toluene vapor appropriate responding or FFR responses on the toluene-appropriate lever. Control tests following exposure to 6000 ppm toluene vapor or 6000 ppm toluene vapor + the i.p. toluene vehicle (first and second filled squared, respectively) resulted in almost 100% toluene vapor-lever responding with all 8 of 8 mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-appropriate lever in both cases.

The bottom panel of figure 3 (filled squares/solid line) shows operant response rates following 10 min of exposure to increasing concentrations of toluene vapor. Up to the highest test concentration of 12000 ppm there were no pronounced changes in response rates in the 5 min test session. This was despite visible ataxia as well as overt signs of respiratory tract irritation such as profuse lacrimation and salivation noted during the transfer of the mice from the vapor exposure chamber to the operant test chamber after exposure to the highest concentration. For these reasons additional higher toluene concentrations were not examined. The bottom panel of figure 3 (open circles/dashed line) also shows the effects of increasing i.p. injected doses of toluene on rates of operant responding. As was the case with toluene vapor, i.p. toluene up to a dose of 720 mg/kg did not have substantial effects on rates of operant responding, although there was a slight trend for decreased responding as dose increased. Higher concentrations of liquid toluene above 720 mg/kg were not examined since maximal toluene vapor appropriate responding was generated at the lower 560 mg/kg dose and 720 mg/kg liquid toluene resulted in overt signs of local irritation in the animals (vocalizations and writhing) immediately after injection. Mean response rates during control test sessions following air, air + i.p. injection vehicle, 6000 ppm toluene and 6000 ppm toluene + i.p. injection vehicle ranged from 1.04 responses/sec in the air control session to 1.39 responses/sec in the 6000 ppm toluene + i.p. vehicle control session (figure 3, bottom panel, first four points). Mean reinforcers earned per session ranged from a low of 26 in the air control session to a high of 36 in the 6000 ppm toluene + i.p. vehicle control session.

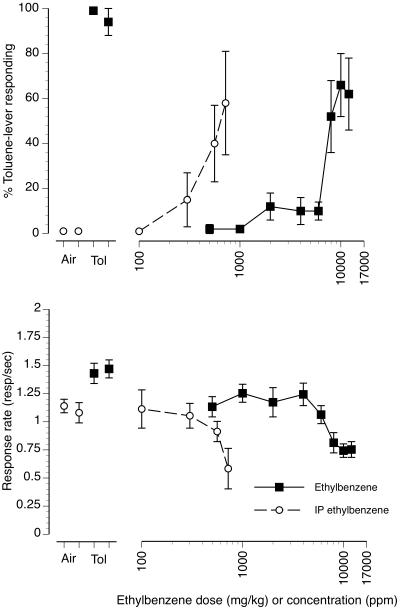

The upper panel of figure 4 (filled squares/solid line) shows the concentration-effect curve for substitution of increasing concentrations of ethylbenzene vapor for the 6000 ppm toluene vapor training concentration. Ethylbenzene vapor produced concentration-dependent partial substitution for the 6000 ppm toluene vapor training concentration. Ethylbenzene concentrations of 500-6000 ppm produced less than 20% toluene-appropriate responding. The 1000 and 2000 ppm ethylbenzene concentrations resulted in 0 of 8 mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-appropriate lever (Table 1). The 4000 and 6000 ppm ethylbenzene concentrations resulted in 1 of 8 and 3 of 8 mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-lever, respectively. The 8000 ppm ethylbenzene vapor concentration produced 52% toluene-appropriate responding with 6 of 8 mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-appropriate lever. Ethylbenzene vapor concentrations of 10000 and 12000 ppm produced 66% and 62% toluene-appropriate responding, respectively. At the 10000 ppm ethylbenzene concentration, 7 of 8 mice emitted their FFR on the toluene-lever, while at the 12000 ppm concentration 5 of 8 mice emitted their FFR on the toluene lever. The upper panel of figure 4 (open circles/dashed line) also shows the substitution of increasing doses of i.p. injected liquid ethylbenzene for the 6000 ppm toluene vapor training condition. Like ethylbenzene vapor, i.p. ethylbenzene produced dose-dependent partial substitution for the toluene vapor training condition. The 100 and 300 mg/kg i.p. doses produced no substitution for toluene vapor with no mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-lever at the 100 mg/kg dose and only 1 of 8 mice emitted their FFR on the toluene-lever at the 300 mg/kg dose. The 560 mg/kg ethylbenzene dose produced 40% toluene-lever responding and 4 of 8 mice making their FFR on the toluene-lever. The 720 mg/kg dose produced 58% toluene vapor-lever responding and 3 of 5 mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-lever.

Figure 4.

Concentration-effect curve for inhaled ethylbenzene vapor and dose-effect curve for injected ethylbenzene in 8 mice trained to discriminate 6000 ppm inhaled toluene from air. Points above Air represent the results of air (first open circle) and air + i.p. vehicle (second open circle) exposure control sessions. Points above Tol represent the results of toluene (first filled square) and i.p. toluene + air (second filled square) exposure control sessions. Mean (± SEM) percentages toluene-lever responding are shown in the upper panel for both inhaled (filled squares/solid line) and i.p. injected (open circles/dashed line) ethylbenzene. Mean (± SEM) response rates in responses per second for both inhaled (filled squares/solid line) and i.p. injected (open circles/dashed line) ethylbenzene as well as control sessions are shown in the bottom panel.

The four leftmost points in the top panel of figure 4 are control test sessions conducted prior to each test curve. Control tests following 10 min of exposure to air or air + the i.p. injection vehicle (first and second open circles, respectively) produced no substitution for 6000 ppm toluene vapor. Control tests following exposure to 6000 ppm toluene vapor (filled square) or 6000 ppm toluene vapor + i.p. injection vehicle (first and second filled squared, respectively) resulted in full substitution for 6000 ppm toluene vapor. FFR responses also demonstrated good stimulus control with all the mice emitting their FFR on the air lever following air and air + i.p. vehicle exposure and the toluene lever following toluene and toluene + i.p. vehicle exposure.

The bottom panel of figure 4 (filled squares/solid line) shows operant response rates following 10 min of exposure to increasing concentrations of ethylbenzene vapor. The highest test concentration of 12000 ppm ethylbenzene vapor resulted in a mean 5-min response rate which was 65% of the air control value. Visible ataxia as well as overt signs of respiratory tract irritation (profuse lacrimation and salivation) were also noted during the transfer of the mice from the vapor exposure chamber to the operant test chamber after exposure to the highest concentration. For these reasons higher ethylbenzene concentrations were not examined. The bottom panel of figure 4 (open circles/dashed line) also shows the effects of increasing i.p. injected doses of ethylbenzene on rates of operant responding. The 720 mg/kg i.p. dose of ethylbenzene produced responses rates which were 54% of those following the air + i.p. vehicle control session. Higher concentrations of i.p. ethylbenzene above 720 mg/kg were not examined since, as was the case with 720 mg/kg i.p. toluene, it produced signs of distress immediately after injection. Response rates during control test sessions following air, air + i.p. injection vehicle, 6000 ppm toluene and 6000 ppm toluene + i.p. injection vehicle are also shown (figure 4, bottom panel, first four points).

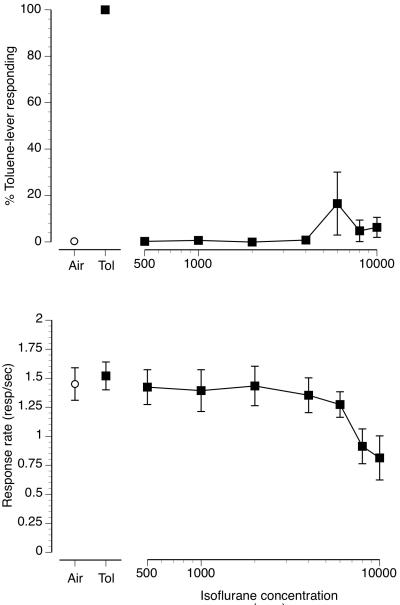

The upper panel of figure 5 (filled squares/solid line) shows the concentration-effect curve for substitution of increasing concentrations of isoflurane vapor for the 6000 ppm toluene vapor training concentration. Isoflurane concentrations of 500-10000 ppm were examined. With the exception of 1 animal each at the 6000 ppm and 8000 ppm concentrations none of the mice emitted their first FR on the toluene-lever following any isoflurane exposure concentration. The bottom panel of figure 5 (filled squares/solid line) shows response rates following isoflurane exposure. The higher isoflurane concentrations produced a concentration-dependent reduction in response rates. The uppermost, 10000 ppm isoflurane concentration, reduced response rates to 0.81 resp/sec compared to a response rate of 1.45 resp/sec in the air exposure control session.

Figure 5.

Concentration-effect curve for inhaled isoflurane vapor in 8 mice trained to discriminate 6000 ppm inhaled toluene from air. Point above Air (open circle) represents the results of the air exposure control session. Point above Tol (filled square) represents the results of the 6000 ppm inhaled toluene exposure control session. Mean (± SEM) percentage toluene-lever responding for isoflurane vapor is shown in the upper panel (filled squares/solid line). Mean (± SEM) response rates in responses per second for isoflurane vapor (filled squares/solid line) as well as response rates during the air (open circle) and toluene control sessions (filled square) are shown in the bottom panel.

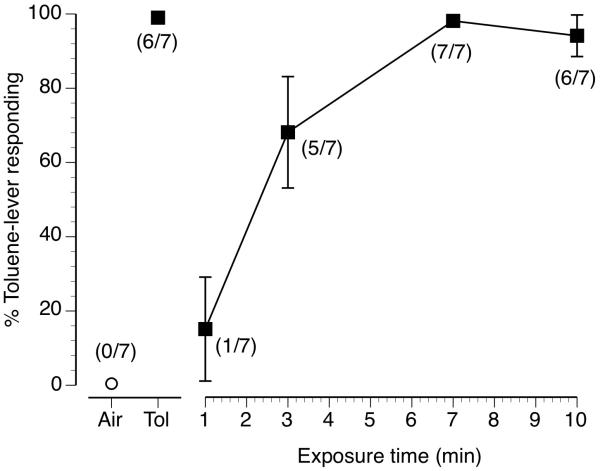

The results of substitution tests following increasing exposure durations to the 6000 ppm toluene vapor training stimulus are shown in figure 6 (filled squares/solid line). Numbers of mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-appropriate lever compared to the total number of mice tested at each exposure duration are shown in parenthesis. Tests were conducted at 1, 3, 7 and 10 min after the beginning of toluene vapor exposure. At the exposure test duration of 1 min, toluene vapor failed to substitute for the training stimulus (10 min of exposure to 6000 ppm toluene vapor) producing 15% toluene-lever responding with only 1 of 7 mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-lever. Partial substitution of 68% toluene-lever responding was produced by the 3 min vapor exposure duration with 5 of 7 mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-appropriate lever. Full substitution was produced by both the 7 and 10 min toluene vapor exposure durations with 7 of 7 and 6 of 7 mice emitting their FFR on the toluene-lever, respectively. Control tests with 10 min of exposure to air (open circle) and 10 min of exposure to 6000 ppm toluene vapor (filled square) are shown as the left two points in figure 5 and resulted in 0% and 100% toluene-lever responding, respectively. No exposure duration had any pronounced effect on rates of operant responding (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Mean exposure time-effect curve for 7 mice trained to discriminate 10 min of exposure to 6000 ppm inhaled toluene vapor from 10 min of exposure to air. Mean (± SEM) percentage inhaled toluene-lever responding as a function of exposure time to 6000 ppm toluene vapor is shown by the filled squares and solid line. Open circle above Air and filled square above Tol represent the results of control test sessions which were preceded by 10 min of air or 6000 ppm toluene vapor exposure, respectively.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study indicate that exposure to 6000 ppm toluene vapor versus air can be readily trained as a discriminative stimulus in B6SJLF1/J mice. The discriminative stimulus effects of inhaled toluene vapor were orderly and concentration dependent across a wide range from 500 to 12,000 ppm (see figure 3, filled squares/solid line). Complete substitution for the 6000 ppm toluene vapor training condition was generated by concentrations of 4000 ppm toluene and greater. This pattern of results is similar to that seen in scores of drug discrimination studies using injected or orally administered drugs in that the percentage drug lever responding increases directly with dose, peaking at or near the training dose.

Exposure to 6000 ppm for comparable durations to that used in the present study produces locomotor incoordination and enhances locomotor activity in mice (Bowen and Balster 1998; Moser and Balster 1985). It also has been shown to strongly suppress operant response rates in mice (Bowen and Balster 1998; Moser and Balster 1986). We chose to use this relatively high concentration of toluene as a training stimulus to maximize the chance of successful acquisition since it has been shown that high drug doses are more easily trained as discriminative stimuli than low drug doses (e.g. Bowen et al., 1999). A mean of only 26 training sessions was necessary to reach acquisition criteria, substantially shorter than the 51 sessions required to train a 1.5 g/kg i.p. ethanol versus saline discrimination in the same strain of mice using comparable training conditions (Shelton et al. 2004). It was also far shorter than the 35 to 100 day range needed to train a discrimination of 100 mg/kg i.p. toluene in Swiss-Webster mice (Rees et al. 1987c) as well as the 121 mean sessions required to train a 100 mg/kg i.p. toluene discrimination in rats (Knisely et al. 1990). The shorter training period suggests that the discriminative stimulus effects of 6000 ppm inhaled toluene are more pronounced than the discriminative stimulus effects of the 100 mg/kg i.p. dose previously trained in mice and rats (Overton et al. 1986). This interpretation is strengthened by the fact that it required an i.p. dose of 560 mg/kg toluene to fully substitute for the 6000 ppm training concentration in the present study. In contrast, it only required 1200 ppm toluene vapor to fully substitute for the 100 mg/kg i.p. toluene training dose in the prior experiment in mice. It is interesting to note that in the present study inhaled concentrations of toluene up to 12,000 ppm produced very little effect on operant performance. This could suggest that tolerance occurred to the rate suppressing effects of toluene, but could also be due to the use of a different strain of mice than that used in the earlier studies (Bowen and Balster 1998; Moser and Balster 1986). Additional experiments specifically designed to examine tolerance to the response-rate suppressing effects of toluene-vapor in B6SJLF1/J mice would be necessary to address this question.

The data from the toluene vapor concentration effect curve is consistent with two alternative hypotheses. The first being that the discriminative stimulus effect of inhaled toluene vapor are controlled by CNS mechanisms as is the case with most other drugs (Colpaert, 1999). The second hypothesis is that the odor cues of toluene were responsible for maintaining the discrimination and as the odor of the test concentration of toluene more closely matched that of the training concentration the degree of substitution also increased. Olfaction in mice is highly developed and has long been know to be used for many natural discriminations such as differentiating between related individuals and searching for food (Bowers and Alexander 1967; Howard et al. 1968). In addition, mice can be readily trained to discriminate between different odors including differentiating between the odor of toluene (also know as methyl benzene) and benzene (Bodyak and Slotnick 1999). If the mice were simply discriminating the odor of toluene versus it’s absence, the inhalation discrimination would have little utility for examining the neurochemical processes underlying the CNS effects of toluene, which are unlikely to be mediated predominantly by olfactory mechanism. For this reason several additional test curves were conducted. In the first of these, the ability of i.p. injected toluene to substitute for the 6000 ppm inhaled toluene vapor training stimulus was examined (figure 3, open circles/dashed line). Injected toluene dose-dependently substituted for 6000 ppm inhaled toluene vapor. Full substitution was produced at the 560 mg/kg i.p. toluene dose. Some percentage of injected toluene absorbed by the bloodstream would be expelled as vapor in exhaled air similar to that which occurs when ethanol vapor is expelled during exhalation after oral or intravenous administration (Subramanian et al. 2002), but it is uncertain if this expelled toluene vapor would be sufficient to produce an odor stimulus similar to the fairly high 6000 ppm toluene vapor concentration. Regardless the i.p. substitution results do show that the discrimination is not dependent upon route of inhalant administration.

To determine the specificity of the inhaled toluene cue and further address the question of odor as a potential exteroceptive cueing mechanism, concentration/dose-response curves were conducted for both inhaled and i.p. ethylbenzene as well as inhaled isoflurane. Ethylbenzene is also a component in abused inhalant mixtures and is closely structurally related to toluene whereas isoflurane is a more structurally dissimilar halogenated ether. Inhaled ethylbenzene vapor produced a maximum of 66% toluene-lever responding at the 10000 ppm concentration whereas isoflurane showed almost no substitution for toluene vapor at any concentration tested. There is emerging evidence that inhalants as well as volatile anesthetics differ in the degree to which they will modulate receptor function (Cruz et al., 2000; Lopreato et al., 2003; Shafer et al., 2005; Ogata et al., 2006) so it is a plausible hypothesis that the disparity in the discriminative stimulus effects of toluene and isoflurane were due to differences in neurotransmitter receptor interactions. It is less certain if less pronounced structural differences between aromatic hydrocarbons alter their pharmacological mechanisms of action to the degree suggested by the ethylbenzene substitution results. Additional substitution tests with other aromatic hydrocarbons will be necessary to more conclusively answer this question.

Alternatively, it might simply have been the case that the distinct odors of the three compounds were responsible for the differences observed in substitution for toluene vapor. The similar levels of partial substitution produced by i.p. injected ethylbenzene and inhaled ethylbenzene make that interpretation somewhat less likely but still not certain. Therefore, in a final test to examine the potential role of odor in producing toluene’s discriminative stimulus effects, a toluene exposure time curve was conducted (figure 6). Mice were exposed to 6000 ppm toluene vapor for increasing durations prior to a standard 5 min discrimination test session. It was hypothesized that if odor was serving as the discriminative stimulus controlling behavior even a brief exposure to 6000 ppm toluene vapor would be sufficient to elicit toluene-appropriate responding. Initial examination of chamber toluene vapor concentrations ascertained that 1 min was the minimum time required to fully volatilize a volume of liquid toluene which was calculated to produce a 6000 ppm vapor concentration (see figure 1). Mean toluene-lever responding following this 1 min exposure was less than 20%. While brief exposure was not sufficient to generate substantial toluene-lever responding, the data did indicate that 3 min of exposure to 6000 ppm toluene vapor produced 68% toluene-lever responding and 7 min of exposure produced full substitution for the 10 min training exposure duration. This is probably not surprising given that volatile vapors are quite quickly absorbed into the bloodstream. In one study with the vapor, 1,1,1-tricholoroethane, blood and brain inhalant concentrations of between 75% and 100% of maximal achievable levels for a wide range of 1,1,1-trichloroethane concentrations were reached in the shortest measured time-point of 6 min (Warren et al. 2000). In addition, the results from the initial inhaled toluene concentration effect curve indicated that 4000 ppm toluene vapor resulted in complete substitution, suggesting that somewhat lower levels of toluene exposure are sufficient to produce discriminative stimulus effects indistinguishable from the 6000 ppm training condition. Individually these tests do not conclusively prove that odor played no role in the toluene vapor versus air discrimination, but in aggregate they strongly suggest that the discrimination was based on CNS-mediated stimulus effects rather than olfaction or other exteroceptive stimulus mechanisms.

Overall, these experiments indicate that drug discrimination studies using inhalants as training stimuli may be a viable method for exploring the neurochemical substrates underlying the discriminative stimulus effects of these compounds. Additional studies using representative test drugs with know receptor mechanisms will be necessary to determine the neurochemical systems responsible for toluene’s discriminative stimulus effects. Studies examining inhalants other than ethylbenzene and isoflurane in animals trained to discriminate toluene vapor may also prove a valuable means to classify inhalants based on their behavioral effects and perhaps predict if they possess toluene-like abuse liability.

5. References

- Balster RL. Abuse potential evaluation of inhalants. Drug Alc Depend. 1987;19:7–15. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(87)90082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balster RL. Discriminative stimulus properties of phencyclidine and other NMDA antagonists. NIDA Res Monogr. 1991:163–80. doi: 10.1037/e496182006-011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balster RL. Neural basis of inhalant abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:207–14. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balster RL, Grech DM, Bobelis DJ. Drug discrimination analysis of ethanol as an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;222:39–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90460-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodyak N, Slotnick B. Performance of mice in an automated olfactometer: odor detection, discrimination and odor memory. Chem Senses. 1999;24:637–45. doi: 10.1093/chemse/24.6.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen CA, Purdy RH, Grant KA. Ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of endogenous neuroactive steroids: Effect of ethanol training dose and dosing procedure. J Pharm Exp Ther. 1999;289:405–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen SE, Balster RL. Effects of inhaled 1,1,1-trichloroethane on locomotor activity in mice. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1996;18:77–81. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(95)02024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen SE, Balster RL. Desflurane, enflurane, isoflurane and ether produce ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;57:191–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen SE, Balster RL. A direct comparison of inhalant effects on locomotor activity and schedule-controlled behavior in mice. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;6:235–47. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen SE, Wiley JL, Balster RL. The effects of abused inhalants on mouse behavior in an elevated plus-maze. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;312:131–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00459-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen SE, Wiley JL, Jones HE, Balster RL. Phencyclidine- and diazepam-like discriminative stimulus effects of inhalants in mice. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;7:28–37. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers JM, Alexander BK. Mice: individual recognition by olfactory cues. Science. 1967;158:1208–10. doi: 10.1126/science.158.3805.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butelman EE, Baron SS, Woods JJ. Ethanol effects in pigeons trained to discriminate MK-801, PCP or CGS-19755. Behav Pharmacol. 1993;4:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert FC. Drug discrimination in neurobiology. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:337–345. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz SL, Balster RL, Woodward JJ. Effects of volatile solvents on recombinant N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:1303–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vry J, Slangen JL. Effects of training dose on discrimination and cross-generalization of chlordiazepoxide, pentobarbital and ethanol in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1986;88:341–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00180836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan PM. The effect of training dose on the discrimination of compound drug-exteroceptive stimuli. Psychopharmacology. 1986;90:543–547. doi: 10.1007/BF00174076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA. Emerging neurochemical concepts in the actions of ethanol at ligand-gated ion channels. Behav Pharmacol. 1994;5:383–404. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199408000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA. Strategies for understanding the pharmacological effects of ethanol with drug discrimination procedures. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:261–7. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Colombo G, Gatto GJ. Characterization of the ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of 5-HT receptor agonists as a function of ethanol training dose. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;133:133–41. doi: 10.1007/s002130050383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA, Knisely JJ, Tabakoff BB, Barrett JJ, Balster RL. Ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects of non-competitive n-methyl-d-aspartate antagonists. Behav Pharmacol. 1991;2:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herling S, Valentino RJ, Winger GD. Discriminative stimulus effects of pentobarbital in pigeons. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1980;71:21–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00433247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard WE, Marsh RE, Cole RE. Food detection by deer mice using olfactory rather than visual cues. Anim Behav. 1968;16:13–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-3472(68)90100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson JO, Jarbe TU. Physostigmine as a discriminative cue in rats. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1976;219:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarebe TU, Hiltunen AJ, Swedber MD. Compound drug discrimination learning. Drug Dev Res. 1989;16:111–22. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Teen drug use down but progress halts among youngest teens. University of Michigan News and Information Services; Ann Arbor, MI: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knisely JS, Rees DC, Balster RL. Discriminative stimulus properties of toluene in the rat. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1990;12:129–33. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(90)90124-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostowski W, Bienkowski P. Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol: neuropharmacological characterization. Alcohol. 1999;17:63–80. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(98)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubena RK, Barry H., 3rd Generalization by rats of alcohol and atropine stimulus characteristics to other drugs. Psychopharmacologia. 1969;15:196–206. doi: 10.1007/BF00411169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopreato GF, Phelan R, Borghese CM, Beckstead MJ, Mihic SJ. Inhaled drugs of abuse enhance serotonin-3 receptor function. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70:11–15. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser VC, Balster RL. The effects of acute and repeated toluene exposure on operant behavior in mice. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1981;3:471–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser VC, Balster RL. Acute motor and lethal effects of inhaled toluene, 1,1,1-trichloroethane, halothane, and ethanol in mice: effects of exposure duration. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1985;77:285–91. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(85)90328-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser VC, Balster RL. The effects of inhaled toluene, halothane, 1,1,1-trichloroethane, and ethanol on fixed-interval responding in mice. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1986;8:525–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson GO. Controlled Test Atmospheres. Principles and Techniques. Ann Arbor Press; 1971. Ann Arbor Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata J, Shiraishi M, Namba T, Smothers CT, Woodward JJ, Harris RA. Effects of Anesthetics on Mutant N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptors Expressed in Xenopus Oocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.101691. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSHA US government printing office; Occupational Safety and Health Standards, Toxic and Hazardous Substances. Code of Federal Regulations. 1998

- Overton DA, Leonard WR, Merkle DA. Methods for measuring the strength of discriminable drug effects. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1986;10:251–263. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(86)90012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees DC, Knisely JS, Balster RL, Jordan S, Breen TJ. Pentobarbital-like discriminative stimulus properties of halothane, 1,1,1-trichloroethane, isoamyl nitrite, flurothyl and oxazepam in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987a;241:507–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees DC, Knisely JS, Breen TJ, Balster RL. Toluene, halothane, 1,1,1-trichloroethane and oxazepam produce ethanol-like discriminative stimulus effects in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987b;243:931–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees DC, Knisely JS, Jordan S, Balster RL. Discriminative stimulus properties of toluene in the mouse. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1987c;88:97–104. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(87)90273-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger DD. Substitution by NMDA antagonists and other drugs in rats trained to discriminate ethanol. Behav Pharmacol. 1993;4:523–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter MD. Transfer of state-dependent control of discriminative behaviour between subcutaneously and intraventricularly administered nicotine and saline. Psychopharmacologia. 1973;32:327–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00429468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter MD, Rosecrans JA. C.N.S. effect of nicotine as the discriminative stimulus for the rat in a T-maze. Life Sci. 1971:821–32. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(71)90037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster CR, Johanson CE. Relationship between the discriminative stimulus properties and subjective effects of drugs. Psychopharmacol Ser. 1988;4:161–75. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-73223-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer TJ, Bushnell PJ, Benignus VA, Woodward JJ. Perturbation of voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channel function by volatile organic solvents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:1109–18. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.090027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KL. Substitution profiles of N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists in ethanol discriminating mice. Alcohol. 2004;34:165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KL, Balster RL. Ethanol drug discrimination in rats: substitution with GABA agonists and NMDA antagonists. Behav Pharmacol. 1994;5:441–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KL, Balster RL. Effects of abused inhalants and GABA-positive modulators in dizocilpine discriminating inbred mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:219–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KL, Dukat M, Allan AM. Effect of 5-HT3 receptor over-expression on the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1161–71. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000138687.27452.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KL, Grant KA. Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J inbred mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:747–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian MG, Heil SH, Kruger ML, Collins KL, Buck PO, Zawacki T, Abbey A, Sokol RJ, Diamond MP. A three-stage alcohol clamp procedure in human subjects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1479–83. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000034038.41972.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ, Murray RB. Manual of Pharmacological Calculations with Computer Programs. 2 edn Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Warren DA, Bowen SE, Jennings WB, Dallas CE, Balster RL. Biphasic effects of 1,1,1-trichloroethane on the locomotor activity of mice: relationship to blood and brain solvent concentrations. Toxicol Sci. 2000;56:365–73. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/56.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]