Abstract

Changes in brain function during the initial weeks of abstinence from chronic methamphetamine abuse may substantially affect clinical outcome, but are not well understood. We used positron emission tomography with [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) to quantify regional cerebral glucose metabolism, an index of brain function, during performance of a vigilance task. Ten methamphetamine-dependent subjects were tested after 5-9 days of abstinence, and after 4 additional weeks of supervised abstinence. Twelve healthy control subjects were tested at corresponding times. Global glucose metabolism increased between tests (p = .01), more in methamphetamine-dependent (10.9%, p = .02) than control subjects (1.9%, NS). Glucose metabolism did not change in subcortical regions of methamphetamine-dependent subjects, but increased in neocortex, with maximal increase (> 20%) in parietal regions. Changes in reaction time and self-reports of negative affect varied more in methamphetamine-dependent than in control subjects, and correlated both with the increase in parietal glucose metabolism, and decrease in relative activity (after scaling to the global mean) in some regions. A robust relationship between change in self-reports of depressive symptoms and relative activity in the ventral striatum may have great relevance to treatment success because of the role of this region in drug abuse-related behaviors. Shifts in cortical-subcortical metabolic balance either reflect new processes that occur during early abstinence, or the unmasking of effects of chronic methamphetamine abuse that are obscured by suppression of cortical glucose metabolism that continues for at least 5-9 days after cessation of methamphetamine self-administration.

Keywords: methamphetamine, drug abuse, brain metabolism, fluorodeoxyglucose, PET imaging, continuous performance test, abstinence

Human subjects who previously abused methamphetamine (MA) exhibit disturbances of mood and cognition during abstinence 1-5. These deficits appear to reflect regional cerebral dysfunction. When abstinent for one week, MA abusers studied with [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) and positron emission tomography (PET) have more severe self-reports of depressive symptoms than control subjects, and these self-reports covary with relative uptake of the radiotracer in anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala 1. Cingulate and insular dysfunctions may also contribute to impaired vigilance in MA-dependent subjects who recently stopped taking the drug 6.

Anterior cingulate dysfunction has also been observed in subjects who maintained abstinence from MA. Deficiencies were seen in activation during performance of a decision-making task after one month of abstinence 2. In another study, cingulate perfusion was lower than control levels after 3 months of abstinence, but was normal in subjects abstinent for 36 months 7.

Abnormalities in cerebral glucose metabolism during the first week of abstinence from MA differ from those observed in a sample abstinent between .5-35 months. Cortical glucose metabolism was above control levels, most markedly in parietal cortex, with lower relative radioactivity (after global scaling) in the striatum and thalamus 8. The thalamic, but not the striatal deficits in relative activity, normalized after the first year 9.

Although the first weeks of abstinence from MA abuse are important for retention in treatment 10, we know of no reports on cerebral metabolic changes during this period. Such effects might have important implications for therapies that involve specific brain circuits, and therefore are the subject of the present report. We hypothesized: 1) that abnormalities during the initial week of abstinence from chronic MA abuse (i.e., lower relative glucose metabolism in the anterior cingulate gyrus, higher relative glucose metabolism in the striatum) 1 would shift, after an additional month of abstinence, to the pattern previously reported after longer abstinence 8,9 through increases in cortical activity, particularly in the parietal lobes, and 2) that changes in activity would be associated with concurrent changes in cognitive performance, as measured by a vigilance task, and in self-reports of depressive symptoms.

Methods

General experimental design

Two groups of research subjects participated. MA-dependent participants resided on a research ward during the study. Cerebral glucose metabolism was assayed using FDG with PET 11 during an auditory vigilance task. Comparison subjects participated on a nonresidential basis. MA-dependent subjects were tested after 5-9 days (mean ± SD = 6.7 ± 1.6 days) and after another month of supervised abstinence (mean ± SD = 27.6 ± 0.96 days). The test interval was analogous for comparison subjects (mean ± SD = 33.1 ± 7.20 days). Participants each provided a self-rating of depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory, BDI) 12 and a urine sample negative for illegal drugs of abuse on the day of each PET scan.

Research participants

The current sample of 10 MA-dependent and 12 comparison subjects overlapped with 17 MA-dependent and 18 comparison subjects in a prior study of mood and cerebral glucose metabolism 1. Only subjects who completed both PET sessions were included. Abstinence was confirmed by urine drug screens during hospitalization. All subjects gave informed consent as approved by the institutional review boards of UCLA and Long Beach VAMC, and were healthy according to medical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests. Left-handedness 13, current use of psychoactive medications, and seropositive status for human immunodeficiency virus were exclusionary.

The groups did not differ significantly on age, gender, ethnicity, education, or mother’s education (Table 1). During the first week of abstinence, subjects completed a self-report intake questionnaire and drug-use survey. Current Axis I diagnoses of dependencies on substances other than nicotine and lifetime Axis I diagnoses unrelated to drug abuse (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; SCID-I) 14, were exclusionary, except that MA-dependence and abuse before enrollment (verified by urine screen) were required for the MA group. Alcohol use < 7.5 drinks per week was permitted.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Research Subjects

| Analysis: | CMRglc | Relative Radioactivity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control n = 7 |

MA n = 9 |

Control n = 12 |

MA N = 10 |

|

| Age (years) a | 33.1(7.17) | 32.9 (7.17) | 33.7 (7.49) | 33.1 (6.79) |

| Gender (males/total number) | 6/7 | 8/9 | 7/12 | 9/10 |

| Subject’s Education (years) a | 15.0 (2.08) | 13.2 (2.10) | 14.5 (2.07) | 13.5 (2.17) |

| Mother’s Education (years) a,b | 13.4 (1.90) | 13.2 (2.82) | 12.9 (1.64) | 13.5 (2.80) |

| Race | ||||

| European (non-Hispanic) | 5/7 | 4/9 | 8/12 | 5/10 |

| European (Hispanic) | 0/7 | 2/9 | 1/12 | 2/10 |

| African American | 2/7 | 1/9 | 3/12 | 1/10 |

| Asian | 0/7 | 2/9 | 0/12 | 2/10 |

| Self – Reported Drug Use c | ||||

| Methamphetamine Use | ||||

| Duration (yr) | - | 8.89 (4.2) | - | 8.20 (4.5) |

| Average (g/wk) | - | 2.10 (2.1) | - | 2.01 (2.0) |

| Days Used in Last 30 | - | 19.3 (6.2) | - | 18.1 (7.01) |

| Tobacco Smokers d | 0/7 | 8/9* | 0/12 | 9/10* |

| Marijuana Use | ||||

| Days in Last 30 | .29 (.76) | 1.67 (3.32) | .17 (0.58) | 1.70 (3.13) |

| Alcohol Use e | ||||

| Days in last 30 | 1.86 (2.12) | 1.44 (1.74) | 2.00 (2.09) | 1.3 (1.70) |

Data shown are means (standard errors of the means) for the number of subjects indicated.

An index of socioeconomic status

Data shown are means (SEM) of self-reported drug use. In addition to the data tabled above regarding regular drug use, data were obtained on other illicit drugs. Seven of ten subjects in the MA group and two of twelve subjects in the control group reported lifetime use of an illicit drug other than marijuana. There were no occurrences of illicit drug use during the last 30 days.

Self-reported smoking ≥ 5 cigarettes per day.

Significantly different from control by Pearson Chi-Square analysis (χ2 (1) = 18.28, p < .001 for relative activity analysis; (χ2(1) = 12.44, P<.001) for CMRglc measurement.

No subject in the MA group had a lifetime history of alcohol abuse or dependence. One control subject had a history of alcohol abuse but no current drug or alcohol-related diagnosis.

Image acquisition

T2 and T1-weighted whole-brain MRI images were acquired (3-T, General Electric), respectively, for exclusion of individuals with frank structural brain abnormalities and for co-registration of PET scans (Siemens ECAT EXACT HR+, Knoxville, TN), acquired in conjunction with an auditory vigilance task. Details on the methods of data acquisition and quantitative analysis of the PET scans have been published 1.

Subjects performed a 30-min auditory vigilance task that required a button press after hearing a tone of designated pitch within a sequence of nontarget tones (inter-stimulus interval = 2 sec). FDG (< 5 mCi) was injected shortly after the vigilance task began. PET images integrated decay-corrected activity from 50-80 min after FDG injection, used as an index of radiotracer uptake during the vigilance task. An input function, using data from arterial samples, was used to determine cerebral metabolic rate for glucose (CMRglc, mg glucose per 100 g tissue per min) at each voxel 15. Voxels exhibiting values < 4 mg/100 g/min were excluded to minimize contributions from cerebrospinal fluid, and remaining voxels averaged to calculate global CMRglc. Although all subjects provided analyzable images of decay-corrected activity, CMRglc could not be calculated for one MA-dependent and five control subjects due to catheter failure or improper instrument calibration.

Statistical analysis

Vigilance performance was quantified by target accuracy and reaction time (RT). Two-tailed t-tests compared the groups on vigilance and continuous demographic variables. Chi square analyses were used for frequency data. The statistical threshold was set at p < .05.

Group comparisons to assess regional relative radioactivity from FDG (regional radioactivity divided by whole-brain radioactivity, used as a surrogate measure of regional – CMRglc), and absolute regional CMRglc (from modeled images) were performed by Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM2; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). PET images were spatially normalized into a standard coordinate system (Montreal Neurological Institute, MNI space), and smoothed with an 8-mm (FWHM) isotropic Gaussian kernel.

Ten regions of interest (ROIs) were selected because of prior demonstrations of functional abnormalities associated with MA abuse: parietal cortex (Brodmann areas [BAs] 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 19, 39, 40), thalamus, dorsal striatum, ventral striatum, medial orbitofrontal cortex (gyrus rectus & medial orbital gyrus; BA 11), lateral orbitofrontal cortex (lateral, posterior orbital & inferior frontal gyri; BAs 47, 11), infragenual anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (BAs 25, 32), supragenual ACC (BAs 24, 32, 33), insula (BA 13), and amygdala. 1, 6, 8, 9

ROIs were drawn on the structural MR template provided in SPM2, using MEDx Software (Sensor Systems, Sterling, VA). Bilateral sampling of these regions provided data on activity changes across sessions within 20 ROIs (i.e., 40 comparisons). Separate analyses were performed for analyses of the cerebral metabolic rate for glucose (CMRglc) and regional relative radioactivity. Additional analyses assessed covariation between changes in regional brain activity across sessions and simultaneous changes in cognitive performance (vigilance task reaction time and depressive symptoms; BDI score).

We set an initial voxel-height threshold of p = .01 (uncorrected) for inclusion in statistical parametric maps. However, to correct for multiple comparisons within a volume of assessed voxels, we considered as significant only findings that also retained a p value < .05 after correction for the volume of the ROI (SPM2 familywise error correction; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). As an additional measure of confidence, effects that retained statistical significance after Bonferroni correction for the number of regions were also identified. Using this approach, the nominal alpha level for a particular region must be < 0.05 divided by the number of comparisons (i.e., .05 / 40 = .0012) in order to exhibit a true alpha level of 0.05. This evidentiary criterion is highly conservative as it assumes that tests of the individual regions are independent of one another. This assumption is certainly untrue because of connectivity between different brain regions, especially brain regions selected for study on the basis of prior reports of a common functional abnormality.

RESULTS

Self-report of drug use

Self report data are given in Table 1. The MA group had used the drug, on average, for > 8 years; consumed about 2-4 g/week, and had used MA on most of the 30 days before entering the study.

Self-report of depressive symptoms

Control subjects reported low ratings of depressive symptoms at the initial measurement (eight BDI scores of 0, two scores of 1, and two scores of 3). Participants in the MA group gave higher self-ratings than control subjects at 5-9 days of abstinence (mean [SD] 5.8 [6.4], (t = 2.73, p = .01). Four weeks later, one control subject reported a 1-unit increase in BDI score. No other scores changed. In contrast, half of the MA group showed a BDI change ≥ 4 units at retest (2 increases, 3 decreases). Although the MA group as a whole reported a 29.3% reduction in BDI score after 4 weeks (from 5.8 to 4.1 [6.1]), this reduction was not significant (t = 0.93, p = .38). At retest, there was no longer a significant difference between groups (t = 1.88, p = .08).

Vigilance task performance

Accuracy on the vigilance task decreased in both groups at retest (MA initial mean [SD] 96.0% [4.4], retest 94.1% [5.6]; control 98.1% [2.3], retest 96.1% [3.3]). Although the Session-by-Group interaction was not significant (F 1, 20 = .01, p = .93), the decrease attained significance in the control group (p = .02) but not in the MA group (p = .37). Since the mean decrease was similar (MA 1.9%; control 2.0%), this finding appeared to be due to larger variance of the change score in the MA group (SD = 6.0%) vs control group (2.5%); Levene’s Test for equality of variance (F = 3.85, p = .06).

Mean RT was 4 ms shorter at retest in the control group (Mean [SD] 664 ms [206] vs. 660 ms [181]) and 43 ms longer in the MA group (714 ms [194] vs. 757 ms [243]). These effects and the Session-by-Group interaction (F 1, 20 = 0.40, p = .53) were not significant. However, there was significantly greater variance in the RT change score for the MA group (43 ms [243]) than in the control group (4 ms [78]), as indicated by Levene’s Test for equality of variance (F = 5.68, p = .03).

Global CMRglc

The total sample showed a significant increase in global CMRglc from the first to the second measurement (F 1, 14 = 8.67, p = .01). The Session-by-Group interaction bordered on significance (F 1, 14 = 4.31, p = .06). Planned comparisons indicated that in the MA group, a 10.9% increase in CMRglc was significant (9.84 vs. 10.91, t 8 = 2.94, p = .02), whereas in the control group the 1.9% increase was not significant (10.19 vs. 10.38, t 6 = 1.71, p = .14).

Regional CMRglc

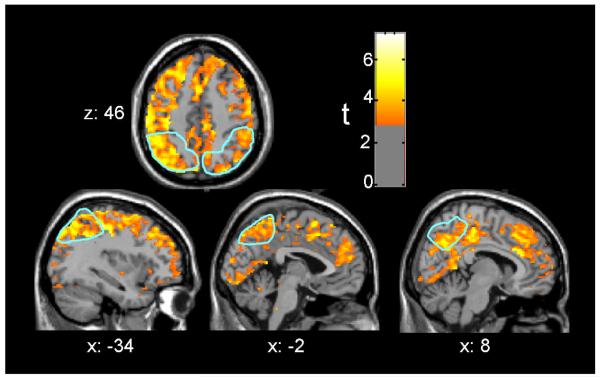

Analyses of the interaction of group with session indicated larger increases at retest in the MA group or decreases in the control group based on volume-corrected spatial-extent p-values in both right and left parietal lobe ROIs (Table 2). These effects maintained statistical significance after Bonferroni correction. Peak voxel effects were significant in the parietal lobes, the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, supragenual cingulate cortex, insula, and thalamus, although voxel effects did not maintain statistical significance after Bonferroni correction. Figure 1 depicts this interaction over much of the cerebral grey matter, including prominent effects in parietal cortex.

Table 2.

Interaction of Group with Change in Absolute rCMRglc

| Cluster-level | Peak Voxel | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in MA group and / or Decrease in Control group | ||||||||||

| Volume corrected Spatial Extent p Value |

Max. Cluster Size (voxels) |

p<.01 voxels in Total ROI |

% ROI |

Volume corrected Voxel Height p Value |

Z- Score |

Coordinates (x, y, z) |

||||

| Parietal Lobe |

Left | <.0005* | 3328 | 3336 | 73% | .019 | 4.37 | −30 | −54 | 64 |

| Right | <.0005* | 1894 | 1922 | 47% | .030 | 4.20 | 20 | −82 | 34 | |

| Lateral Orbitofrontal |

Left | .107 | 92 | 199 | 16% | .035 | 3.83 | −42 | 50 | −6 |

| Right | .071 | 114 | 213 | 19% | .007 | 4.32 | 44 | 22 | −14 | |

| Insula | Left | .322 | 19 | 45 | 4% | .362 | 2.69 | −42 | 18 | −2 |

| Right | .276 | 24 | 29 | 2% | .028 | 3.78 | 48 | 18 | −6 | |

| ACCsg | Left | .018 | 179 | 219 | 22% | .079 | 3.29 | −2 | 46 | 16 |

| Right | .035 | 136 | 175 | 23% | .048 | 3.49 | 8 | 28 | 24 | |

| Thalamus | Left | |||||||||

| Right | .068 | 85 | 85 | 15% | .040 | 3.59 | 12 | −28 | 0 | |

| Within Group simple effects: Increase in MA group | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parietal Lobe |

Left | <.0005* | 4539 | 4540 | 99% | <.0005* | 5.30 | −28 | −78 | 46 |

| Right | <.0005* | 4023 | 4023 | 98% | <.0005* | 5.42 | 20 | −82 | 34 | |

| Lateral Orbitofrontal |

Left | <.0005* | 984 | 984 | 81% | .009 | 4.25 | −42 | 50 | −6 |

| Right | <.0005* | 872 | 872 | 78% | <.0005* | 5.04 | 44 | 22 | −14 | |

| Medial Orbitofrontal |

Left | .019 | 195 | 255 | 27% | .009 | 4.15 | −26 | 48 | −14 |

| Right | .034 | 149 | 222 | 26% | .119 | 3.24 | 22 | 44 | −16 | |

| Insula | Left | <.0005* | 746 | 752 | 64% | .034 | 3.73 | −34 | 22 | 0 |

| Right | <.0005* | 609 | 681 | 55% | .001* | 4.87 | 48 | 18 | −6 | |

| ACCsg | Left | <.0005* | 889 | 889 | 91% | .008 | 5.84 | −6 | 36 | 16 |

| Right | <.0005* | 723 | 723 | 96% | .006 | 4.18 | 6 | 26 | 24 | |

| ACCig | Left | .075 | 29 | 38 | 20% | .064 | 2.90 | −8 | 38 | −14 |

| Right | .039 | 55 | 55 | 40% | .015 | 3.41 | 4 | 42 | −8 | |

Included in tables 2 and 3 are those of the 20 ROIs that were assessed (10 in each hemisphere) where the noted effect attained volume-corrected probability <.05 at the peak voxel, and for comparative purposes, the homologous ROI in the opposite hemisphere. The size and spatial-extent probability associated with the largest cluster, the total proportion of the ROI constituted by all clusters, and the peak voxel Z-score, associated probability, and MNI coordinates are tabled. ACCsg = supragenual anterior cingulate cortex, ACCig = infragenual anterior cingulate cortex

Statistical significance maintained after applying the Bonferroni correction for 40 comparisons (.05 / 40 = .0012).

Figure 1. Parietal cortex CMRglc increased between sessions in the MA abuse group, more than in the control group.

The figures are depicted in neurological orientation. The gray-scale image is a T1 structural MRI that is representative of MNI space, where positive values of the x, y, and z coordinates approximately represent mm to the right, anterior and superior relative to the sagittal midpoint of the anterior commissure. The a priori parietal lobe regions of interest (ROIs) are outlined in light blue. Red/yellow colors indicate greater increases in CMRglc from initial PET session to four weeks later in 9 MA, as compared to 7 control subjects (p < .01 uncorrected).

Separate analysis of the change across session within each group confirmed that the effects depicted in Figure 1 were due solely to widespread increases in the MA group. They attained Bonferroni-corrected spatial-extent significance in bilateral parietal lobe, lateral orbitofrontal cortex, insula and supragenual cingulate gyrus (Table 2). Peak voxel effects attained Bonferroni-corrected significance in bilateral parietal lobe, right lateral orbitofrontal cortex and right insula. Whole brain statistical analysis revealed that no voxel in the MA group showed a decrease in CMRglc of p < .01, even prior to correction for multiple comparisons.

Regional relative radioactivity

The interaction of group with session produced evidence for greater increase in the MA group or decrease in the control group by the criterion of spatial-extent in the right parietal lobe (p = .033), and of peak height in the parietal lobes (left p = .029; right p = .023), right lateral orbitofrontal cortex (p = .017), and right insula (p = .028). A peak voxel in the left dorsal striatum had a greater decrease in the MA group, or increase in the Control group, (p = .017). No effects survived Bonferroni correction.

However, separate analysis of the MA group confirmed an increase in the bilateral parietal lobes (left and right spatial-extent p <.0005; both peak voxel z > 4.8, both p = .001), and right lateral orbitofrontal cortex (spatial-extent p <.003; peak voxel z = 4.21, p = .003). All parietal effects retained significance after Bonferroni correction, but the orbitofrontal cortex effects did not.

Relationship between changes in regional CMRglc or relative radioactivity and vigilance task performance

In the control group, there was no relationship between RT change and either regional CMRglc or relative radioactivity.

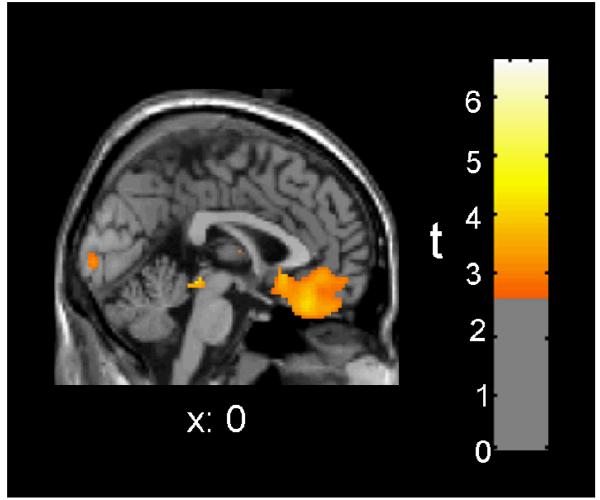

In the MA group, the amount of RT slowing was associated with increases in regional CMRglc by the criterion of spatial extent for clusters in the left (32 voxels, p = .047) and right parietal lobes (166 voxels, p = .004). The peak voxel effect in the right parietal lobe (14, −62, 48) was also significant (Z = 4.38, p = .024). Although the amount of RT slowing was not associated with increased relative radioactivity in any ROI, it was associated with a decrease in 7 of the 20 ROIs by the criterion of peak voxel-height (Table 3). Six of these ROIs were also significant for spatial extent, with the largest effects in ventromedial orbitofrontal cortex (Figure 2). The spatial-extent effect in the right medial orbitofrontal cortex retained significance after Bonferroni correction.

Table 3.

MA Group: Association of Change in RT to Change in Relative Brain Activity

| Cluster-level | Peak Voxel | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Covariation (One measure increases when the other decreases) | ||||||||||

| Volume corrected Spatial Extent p Value |

Max. Cluster Size (voxels) |

p<.01 voxels in Total ROI |

% ROI |

Volume corrected Voxel Height p Value |

Z- Score |

Coordinates (x, y, z) |

||||

| Lateral Orbitofrontal |

Left | |||||||||

| Right | .025 | 367 | 381 | 20% | .042 | 3.46 | 46 | 42 | −10 | |

| Medial Orbitofrontal |

Left | .013 | 445 | 447 | 32% | .033 | 3.45 | −10 | 22 | −14 |

| Right | .001* | 1188 | 1188 | 91% | .012 | 3.80 | 10 | 46 | −20 | |

| ACCig | Left | .029 | 129 | 129 | 59% | .006 | 3.58 | −6 | 22 | −10 |

| Right | .031 | 113 | 113 | 50% | .031 | 2.94 | 2 | 36 | −16 | |

| Dorsal Striatum |

Left | .124 | 92 | 92 | 8% | .046 | 3.31 | −14 | 6 | 18 |

| Right | .146 | 82 | 121 | 13% | .093 | 3.06 | 26 | −10 | 8 | |

| Ventral Striatum |

Left | .085 | 1 | 1 | 1% | .086 | 2.35 | −4 | 14 | −14 |

| Right | .049 | 40 | 40 | 23% | .010 | 3.25 | 10 | 14 | −14 | |

Statistical significance maintained after applying the Bonferroni correction for 40 comparisons (.05 / 40 = .0012).

Figure 2. Between-session directional change in relative radioactivity of medial orbitofrontal cortex was inversely correlated with vigilance reaction time (RT) in the MA abuse group.

Red/yellow colors indicate areas where the amount of RT slowing from initial PET session to four weeks later was associated with decreased regional relative radioactivity in 10 MA subjects (p < .01 uncorrected).

Relationship between changes in regional CMRglc or relative radioactivity and depressive symptoms in MA Group

As BDI scores were negligible, with no meaningful change between assessments in the control group, these analyses were only conducted for the MA group. The extent of the increase in regional CMRglc in the left parietal lobe was directly associated with BDI score by the criteria of spatial extent (p = .045) and peak voxel height (x,y,z = −32, −40, 64; Z = 4.57, p = .005).

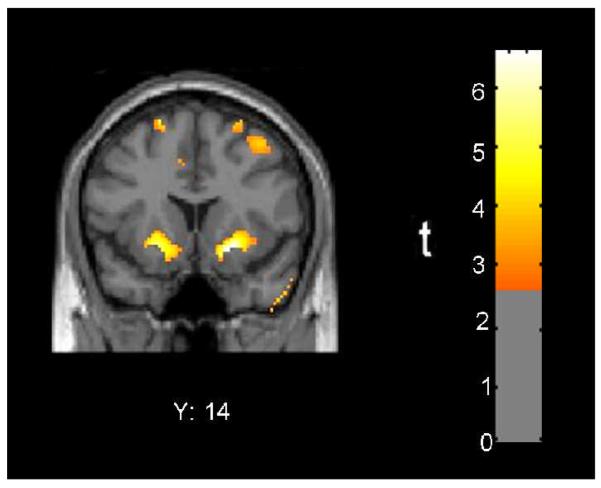

BDI score was correlated with change in relative radioactivity in at least one cerebral hemisphere for all ROIs with the exception of the thalamus (Table 4). BDI score was positively correlated with the change in relative radioactivity by criteria for both spatial extent and peak voxel effect in the right parietal lobe, right amygdala, and bilateral ventral striatum, and in the bilateral dorsal striatum by the criterion of peak voxel effect. The peak effect in the right ventral striatum retained significance after Bonferroni correction (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Association of Change in BDI to Change in Relative Brain Activity

| Cluster-level | Peak Voxel | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Covariation (Both measures decrease or increase in parallel) | ||||||||||

| Volume corrected Spatial Extent p Value |

Max. Cluster Size (voxels) |

p<.01 voxels in Total ROI |

% ROI |

Volume corrected Voxel Height p Value |

Z- Score |

Coordinates (x, y, z) |

||||

| Parietal Lobe |

Left | .364 | 18 | 18 | 1% | .289 | 2.65 | −28 | −32 | 68 |

| Right | .045 | 432 | 432 | 17% | .029 | 3.66 | 38 | −32 | 68 | |

| Amygdala | Left | |||||||||

| Right | .048 | 3 | 3 | 9% | .036 | 2.50 | 28 | −4 | −16 | |

| Dorsal Striatum |

Left | .079 | 176 | 176 | 16% | .012 | 3.69 | −20 | 16 | −6 |

| Right | .078 | 192 | 192 | 21% | .003 | 4.11 | 22 | 16 | −6 | |

| Ventral Striatum |

Left | .031 | 85 | 85 | 57% | .002 | 3.72 | −20 | 14 | −8 |

| Right | .042 | 56 | 56 | 33% | <.0005* | 4.43 | 20 | 14 | −10 | |

| Negative Covariation (One measure increases when the other decreases) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral Orbitofrontal |

Left | .171 | 89 | 89 | 5% | .082 | 3.13 | −34 | 40 | −6 |

| Right | .099 | 242 | 242 | 13% | .008 | 3.92 | 52 | 22 | −8 | |

| Medial Orbitofrontal |

Left | .195 | 32 | 37 | 3% | .126 | 2.81 | −18 | 44 | −24 |

| Right | .048 | 260 | 269 | 21% | .099 | 2.92 | 16 | 52 | −18 | |

| Insula | Left | .064 | 219 | 220 | 16% | .003 | 4.11 | −34 | 8 | 16 |

| Right | .041 | 298 | 298 | 22% | .010 | 3.77 | 36 | −8 | 16 | |

| ACCsg | Left | .128 | 68 | 68 | 7% | .055 | 3.07 | −2 | 60 | 14 |

| Right | .043 | 272 | 272 | 27% | .048 | 3.15 | 12 | 38 | −4 | |

| ACCig | Left | .094 | 7 | 7 | 3% | .077 | 2.51 | −2 | 20 | −14 |

| Right | .032 | 126 | 126 | 56% | .014 | 3.17 | 12 | 38 | −6 | |

| Dorsal Striatum |

Left | .093 | 147 | 163 | 15% | .041 | 3.27 | −18 | 16 | 14 |

| Right | .175 | 61 | 80 | 9% | .033 | 3.38 | 30 | −2 | 12 | |

Statistical significance maintained after applying the Bonferroni correction for 40 comparisons (.05 / 40 = .0012).

Figure 3. Between-session directional change in relative radioactivity of ventral striatum was directly correlated with self-reported depressive symptoms in the MA abuse group.

Red/yellow colors indicate areas where change in BDI score from initial PET session to four weeks later was associated with change in regional relative radioactivity in 10 MA subjects (p < .01 uncorrected).

BDI score was negatively correlated with the change in relative radioactivity (one measure increased when the other decreased) by criteria for both spatial extent and peak voxel effect in the right infragenual cingulate cortex, right supragenual cingulate cortex and right insula. The indirect associations were significant by the peak voxel criterion only in the left insula, right lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and bilateral dorsal striatum, and by the spatial extent criterion only in the right medial orbitofrontal cortex (Table 4).

Discussion

Widespread, large increases in cortical CMRglc (>20% in parietal lobes) develop during the initial month of MA-abstinence. Notably, parietal glucose metabolism during the initial week of abstinence from MA does not differ from that in healthy comparison subjects but reportedly is higher after prolonged abstinence. This combination of findings may indicate that residual effects of MA on CMRglc persist for at least a week after initiating abstinence, making an underlying chronic effect; or session of chronic MA administration produces new effects that evolve after the first week of abstinence form the drug. At retest, participants who were maintaining abstinence from MA varied more than healthy subjects on task performance and global CMRglc. Such heterogeneity is consistent with considerable variation in the magnitude or timecourse of physiological abnormalities during early MA abstinence.

Importance of absolute measures

Although many functional brain imaging studies have used only measures of relative activity, our results underscore the value of absolute measures of cerebral glucose metabolism. During the first month without MA, CMRglc increased in most of the superior cortex. These widespread increases changed the global mean, and therefore the relative measures scaled to that mean. Despite the greater sample size for analysis of changes in regional relative radioactivity, scaling reduced the power to detect significant differences between groups. The pattern of higher relative radioactivity in striata of MA abusers during the first week of abstinence 6 was reversed four weeks later. With only relative measures, this might be interpreted as a loss of striatal function, but there was no absolute change in this region. Absolute measures suggest that relative decreases in striatal radioactivity may actually measure the degree of global increase in CMRglc driven by widespread cortical change.

With only relative measures, one might interpret the relationship between slowing of vigilance reaction time and decreased relative ventromedial frontal radioactivity depicted in Figure 2 as a frontomedial metabolic deficit with cognitive consequences. However, comparison of Figure 2 to Figure 1 shows that the ventromedial frontal region where decreased relative radioactivity is reliably related to slowed vigilance reaction time is precisely that part of cortex where the actual level of metabolic activity changed least. The largest metabolic change, the degree of increased parietal CMRglc, was associated with both slowed vigilance reaction time and with less reduced (or higher) self-report of depressive symptoms. Subjects with larger metabolic increases in parietal cortex will have larger whole-brain increases. Larger whole-brain increases generate relative activity decrease in areas where absolute activity increases less than the global index. Since no brain area showed a decrease in absolute CMRglc over the first weeks of abstinence, the magnitude of CMRglc increase in the parietal lobes may constitute a measure of the severity of brain insult, or the inability to recover normal brain function. Distractibility and anhedonia are two deficits associated with abstinence from chronic MA abuse 17. This explanation is, therefore, consistent with negative covariation of both vigilance reaction time and BDI score with relative activity in the medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortex, ventral cingulate, and dorsal striatum (Tables 3 and 4), areas where CMRglc increased less than in the parietal lobes.

Behavioral observations during early withdrawal

MA withdrawal has an early phase with severity greatest at 24 h after final use, decreasing over the next week 16, 17 and stabilizing at 7-10 days. The initial week is characterized by depression, craving, anxiety, increased sleeping and eating. Together with prior results 1, 6, 8, 9, the current results suggest that during this phase, subcortical and limbic radiotracer uptake are abnormally high and cortical uptake is abnormally low, whereas later abstinence is associated with higher CMRglc in posterior, particularly parietal cortices.

Possibly reflecting reduced novelty to some degree, there was evidence for reduced vigilance at retest, i.e. – accuracy decreased by 2% in both groups. Mean reaction time was 41 ms longer at retest with higher variance in the MA group than the control group. BDI scores also were higher and more variable in the MA group than in the control group, with negligible BDI score or change across sessions in the control group, but notable change in half of the MA group. As discussed above, increased parietal CMRglc was associated with both slower vigilance reaction time and less drop in BDI score, and this may have produced the negative covariations with relative activity in Tables 3 and 4.

In contrast, the robust positive covariation between the change in BDI score and relative activity in the ventral striatum suggests that although the MA-group had no overall change in activity of the ventral striatum at retest, subjects with lower BDI scores also had less relative activity, subjects with higher BDI scores also had more relative activity, or both. The association of ventral striatal activity with the change in BDI score during the critical early weeks of abstinence from MA is particularly important because of the role of the nucleus accumbens in drug-mediated reinforcement 18, withdrawal 19, and relapse 20.

The dorsal striatum yielded evidence for areas with both positive and negative covariation between change in BDI score and relative activity. Visual inspection of the statistical parametric maps indicated the positive covariation represented extension of effects in the ventral striatum into the inferior dorsal putamen (see Figure 3), whereas the negative covariation occurred about 2 cm superiorly in the most dorsal 10% of the dorsal striatum.

Possible interpretations of changes in cortical glucose metabolism

Although MA abuse produces the most profound neurotoxicity in the dopamine-rich basal ganglia 21-23, it also increases proliferation of cortical microglia and astrocytes 24. Increasing the numbers of both types of glia are thought to increase CMRglc 25. Therefore, Volkow and associates 8 suggested that higher parietal activity in MA abusers could reflect reactive gliosis after excitotoxic damage to parietal neurons. Notably, the rat brain shows MA-associated neurodegeneration in parietal cortices 26.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) investigations of MA abuse have reported basal ganglia and frontal cortical metabolite abnormalities consistent with gliosis 27-30, including an abnormally high choline signal, a potential index of glial density, in the anterior cingulate cortex of MA abusers abstinent less than six months 31. However, the signal was negatively correlated with duration of abstinence, and had returned to control values after more than one year. The authors suggested the first 8 months following MA neurotoxicity are characterized by axon sprouting and gliosis, whereas later abstinence features axon pruning and recovery. Our preliminary MRS investigations of the parietal lobes 32 did not find evidence for this abnormally high choline signal at 5-9 days of abstinence.

In rats, three daily exposures to MA are sufficient to induce reactive gliosis lasting 14-21 days 21. Our subjects used MA regularly for many years. If the elevated parietal metabolism we report at one month of abstinence, and previously reported later in abstinence 8, derives from parietal gliosis, either gliosis did not occur until after the initial week of abstinence, or some process masks the gliosis-mediated increase in parietal CMRglc during the initial week.

Cortical/subcortical homeostasis

Metabolic abnormalities in the MA group at one week abstinence 1 resemble those observed in a previous human study of acute MA effects; less cortical activity and more subcortical activity 33. Reduction of cortical CMRglc is a common response to acute administration of drugs of abuse 34, as observed with opiates 35, barbiturates 36, benzodiazepines 37, cocaine 38, and amphetamine 39. This commonality is consistent with a classic theory proposing that activity in subcortical emotion circuits alters human consciousness more when cortical inhibition is suppressed 40. In this view, metabolic effects of intoxication represent release of subcortical regions from cortical inhibition, resulting in heightened emotions.

If chronic MA use inhibits cortical activity, compensatory adjustment might work to up-regulate cortical activity. Although the time-course of inhibition of cortical activity after acute MA intoxication has not been well-studied, compensatory changes after chronic abuse should be unmasked after a sufficient period of abstinence. The time-course and reversibility of any such adjustments are also unknown.

Unmasking increased noradrenergic tone

Our vigilance task required detection of rare events, termed “oddballs.” Oddball detection in all sensory modalities activates frontoparietal attention networks 41, which generate the P300 event-related scalp potential. Parietal activity during oddball detection, has been linked to noradrenergic modulation 42 and frontal activity to dopaminergic modulation 43. Therefore, another possible explanation of the changes observed during the first month of abstinence from MA is that progressive unmasking of increased noradrenergic tone due to long-term MA abuse and accompanying dopaminergic neurotoxicity has shifted frontoparietal attention networks toward relatively more parietal activity, and that lowered efficiency of frontal executive arousal networks has increased vigilance reaction time. This idea is consistent with reports that a rat analog of P300 was reduced by 15 days of MA followed by over a week of abstinence 44, just as the human P300 is reduced during recovery from MA-abuse 45.

Limitations

This study has a small sample size of abstaining MA users. However, most previous studies of regional brain function during abstinence from chronic MA have not considered longitudinal changes, or have compared subjects tested once during broad periods of early abstinence, (usually < 6 months), with subjects tested during later abstinence. 46, 7, 8, 9 As the only previous report on repeated assessments of brain function compared 5 subjects tested at < 6 months abstinence to reassessment between 12 and 17 months 9, the current report represents the largest sample of subjects tested twice during abstinence and the first study to compare two narrowly specified periods of abstinence (5-9 days vs 32-36 days).

Although chronic MA-use has been associated with lesions in both gray 47 and white matter 48, we did not consider structural influences on our functional measures. A previous study of 22 MA-abusers and 21 controls from which the current subjects were drawn did not find structural changes in the parietal lobes 47. However, a larger group of 43 former MA-abusers had larger gray matter volumes than control subjects in both parietal cortex and basal ganglia 49. Because prolonged functional activity can increase local grey matter 50, high striatal activity during the first week of abstinence 1, combined with high parietal activity in later abstinence (this paper and a previous report 8), suggests that alternating between periods of use and abstinence may produce cumulative increases in the volumes of both structures.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the following support from the National Institute of Health: Grants 5RO1 DA 15179 and 5RO1 DA 020726 [to EDL], MOI RR 00865 and contract 1 Y01 DA 50038 [to EDL, WL]. Preliminary reports have been presented in abstracts at the following annual meetings: American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Waikoloa, HI, December 8, 2001; American Psychiatric Association, Philadelphia, PA, May 18, 2002; Cognitive Neuroscience Society, San Francisco, CA, April 14 2002; XXIII CINP Congress, Montreal, Canada, June 23, 2002; Society for Neuroscience, Atlanta, GA, October 14, 2006.

Reference List

- 1.London ED, Simon SL, Berman SM, Mandelkern MA, Lichtman AM, Bramen J, et al. Mood disturbances and regional cerebral metabolic abnormalities in recently abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004;61:73–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paulus MP, Hozack N, Frank L, Brown GG, Schuckit MA. Decision making by methamphetamine-dependent subjects is associated with error-rate-independent decrease in prefrontal and parietal activation. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;53:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monterosso JR, Aron AR, Cordova X, Xu J, London ED. Deficits in response inhibition associated with chronic methamphetamine abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:273–277. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalechstein AD, Newton TF, Green M. Methamphetamine dependence is associated with neurocognitive impairment in the initial phases of abstinence. Neurophysiology Clin. 2003;15:215–220. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salo R, Nordahl TE, Possin K, Leamon M, Gibson DR, Galloway GP, et al. Preliminary evidence of reduced cognitive inhibition in methamphetamine-dependent individuals. Psychiatry Res. 2002;111:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.London E, Berman S, Voytek B, Simon S, Monterosso J, Geaga J, et al. Cerebral metabolic dysfunction and impaired vigilance in recently abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;58:770–778. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang J, Lyoo IK, Kim SJ, Sung YH, Bae S, Cho SN, et al. Decreased cerebral blood flow of the right anterior cingulate cortex in long-term and short-term abstinent methamphetamine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Franceschi D, Sedler MJ, et al. Higher cortical and lower subcortical metabolism in detoxified methamphetamine abusers. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:383–389. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang G-J, Volkow ND, Chang L, Miller E, Sedler M, Hitzemann R, et al. Partial recovery of brain metabolism in methamphetamine abusers after protracted abstinence. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161:242–248. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brecht ML, von Mayrhauser C, Anglin MD. Predictors of relapse after treatment for methamphetamine use. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:211–220. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phelps ME, Huang SC, Hoffman EJ, Selin C, Sokoloff L, Kuhl DE. Tomographic measurement of local cerebral glucose metabolic rate in humans with (F-18)2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose: Validation of method. Ann. Neurol. 1979;6:371–388. doi: 10.1002/ana.410060502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Revised Beck Depression Inventory. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denckla MB. Revised Neurological Examination for Subtle Signs (1985) Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1985;21:773–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders- Patient Edition (SCID-IP, Version 2.0) Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang S-C, Phelps ME, Hoffman EJ, Sideris K, Selin CJ, Kuhl DE. Noninvasive determination of local cerebral metabolic rate of glucose in man. Am. J. Physiol. 1980;238:E69–E82. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1980.238.1.E69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGregor C, Srisurapanont M, Jittiwutikarn J, Laobhripatr S, Wongtan T, White JM. The nature, time course and severity of methamphetamine withdrawal. Addiction. 2005;100:1320–1329. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newton TF, Kalechstein AD, Duran S, Vansluis N, Ling W. Methamphetamine abstinence syndrome: Preliminary findings. American Journal on Addictions. 2002;13:248–255. doi: 10.1080/10550490490459915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koob GF. Neural mechanisms of drug reinforcement. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1992;654:171–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb25966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammer RP, Jr., Pires WS, Markou A, Koob GF. Withdrawal following cocaine self-administration decreases regional cerebral metabolic rate in critical brain reward regions. Synapse. 1993;14:73–80. doi: 10.1002/syn.890140110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss F, Ciccocioppo R, Parsons LH, Katner S, Liu X, Zorrilla EP, et al. Compulsive drug-seeking behavior and relapse. Neuroadaptation, stress, and conditioning factors. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001;937:1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pennypacker KR, Kassed CA, Eidizadeh S, O’Callaghan JP. Brain injury: prolonged induction of transcription factors. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. (Wars. ) 2000;60:515–530. doi: 10.55782/ane-2000-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCann UD, Wong DF, Yokoi F, Villemagne V, Dannals RF, Ricaurte GA. Reduced striatal dopamine transporter density in abstinent methamphetamine and methcathinone users: evidence from positron emission tomography studies with [11C]WIN-35,428. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8417–8422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08417.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang G-J, Fowler JS, Franceschi D, Sedler M, et al. Loss of dopamine transporters in methamphetamine abusers recovers with protracted abstinence. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:9414–9418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09414.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaVoie MJ, Card JP, Hastings TG. Microglial activation precedes dopamine terminal pathology in methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. Exp. Neurol. 2004;187:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roh JK, Nam H, Lee MC. A case of central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis with early hypermetabolism on 18FDG-PET scan. J Korean Med. Sci. 1998;13:99–102. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1998.13.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowyer JF, Clausing P, Gough B, Slikker W, Jr., Holson RR. Nitric oxide regulation of methamphetamine-induced dopamine release in caudate/putamen. Brain Res. 1995;699:62–70. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00877-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ernst T, Chang L, Leonido-Yee M, Speck O. Evidence for long-term neurotoxicity associated with methamphetamine abuse: A 1H MRS study. Neurology. 2000;54:1344–1349. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.6.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nordahl TE, Salo R, Possin K, Gibson DR, Flynn N, Leamon M, et al. Low N-acetyl-aspartate and high choline in the anterior cingulum of recently abstinent methamphetamine-dependent subjects: a preliminary proton MRS study. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Psychiatry Res. 2002;116:43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(02)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekine Y, Iyo M, Ouchi Y, Matsunaga T, Tsukada H, Okada H, et al. Methamphetamine-related psychiatric symptoms and reduced brain dopamine transporters studied with PET. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1206–1214. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith LM, Chang L, Yonekura ML, Grob C, Osborn D, Ernst T. Brain proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and imaging in children exposed to methamphetamine in utero. Neurology. 2001;57:255–260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nordahl TE, Salo R, Natsuaki Y, Galloway GP, Waters C, Moore CD, et al. Methamphetamine users in sustained abstinence: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:444–452. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Neill JO, Monterosso J, Walker MK, London ED. 1H MRSI brain findings in chronic methamphetamine abuse. Program 392.9, 2006 Neuroscience Meeting Planner, Atlanta, Georgia, Society for Neuroscience; 2006. online. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gouzoulis-Mayfrank E, Schreckenberger M, Sabri O, Arning C, Thelen B, Spitzer M, et al. Neurometabolic effects of psilocybin, 3,4-methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDE) and d-methamphetamine in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:565–581. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00089-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.London ED, Grant SJ, Morgan MJ, Zukin SR. Neurobiology of drug abuse. In: Fogel BS, Schiffer RB, Rao SM, editors. Neuropsychiatry. William & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1996. pp. 635–678. [Google Scholar]

- 35.London ED, Broussolle EP, Links JM, Wong DF, Cascella NG, Dannals RF, et al. Morphine-induced metabolic changes in human brain. Studies with positron emission tomography and [fluorine 18]fluorodeoxyglucose. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1990;47:73–81. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810130075010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Theodore WH, DiChiro G, Margolin R, Fishbein D, Porter RJ, Brooks RA. Barbiturates reduce human cerebral glucose metabolism. Neurology. 1986;36:60–64. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foster NL, VanDerSpek AFL, Aldrich MS, Berent S, Hichwa RH, Sackellares JC, et al. The effect of diazepam sedation on cerebral glucose metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease as measured using positron emission tomography. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1987;7:415–420. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1987.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.London ED, Cascella NG, Wong DF, Phillips RL, Dannals RF, Links JM, et al. Cocaine-induced reduction of glucose utilization in human brain. A study using positron emission tomography and [fluorine 18]-fluorodeoxyglucose. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1990;47:567–574. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180067010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolkin A, Angrist B, Wolf A, Brodie J, Wolkin B, Jaeger J, et al. Effects of amphetamine on local cerebral metabolism in normal and schizophrenic subjects as determined by positron emission tomography. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1987;92:241–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00177923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cannon WB. The James-Lange theory of emotions: A critical examination and an alternative theory. Am. J. Psychol. 1927;39:106–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang MX, Lee RR, Miller GA, Thoma RJ, Hanlon FM, Paulson KM, et al. A parietal-frontal network studied by somatosensory oddball MEG responses, and its cross-modal consistency. Neuroimage. 2005;28:99–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nieuwenhuis S, Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. Decision making, the P3, and the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system. Psychol. Bull. 2005;131:510–532. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polich J, Criado JR. Neuropsychology and neuropharmacology of P3a and P3b. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2006;60:172–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeuchi S, Jodo E, Suzuki Y, Matsuki T, Niwa S, Kayama Y. Effects of Repeated Administration of Methamphetamine on P3-like Potentials in Rats. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1999;32:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(99)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwanami A, Suga I, Kaneko T, Sugiyama A, Nakatani Y. P300 Component of Event-related Potentials in Methamphetamine Psychosis and Schizophrenia. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol & Biol Psychiat. 1994;18:465–475. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nordahl TE, Salo R, Natsuaki Y, Galloway GP, Waters C, Moore CD, et al. Methamphetamine users in sustained abstinence: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:444–452. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson PM, Hayashi K, Simon SL, Geaga JA, Hong MS, Sui Y, et al. Structural abnormalities in the brains of human subjects who use methamphetamine. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6028–6036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0713-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oh JS, Lyoo IK, Sung YH, Hwang J, Kim J, Chung A, et al. Shape changes of the corpus callosum in abstinent methamphetamine users. Neurosci. Lett. 2005;384:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.04.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jernigan TL, Gamst AC, Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Mindt MR, Marcotte TD, et al. Effects of methamphetamine dependence and HIV infection on cerebral morphology. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1461–1472. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Draganski B, Gaser C, Busch V, Schuierer G, Bogdahn U, May A. Neuroplasticity: changes in grey matter induced by training. Nature. 2004;427:311–312. doi: 10.1038/427311a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]