Abstract

Mutations in the human cytomegalovirus (CMV) UL97 protein kinase are the most common mechanism of ganciclovir (GCV) resistance in the clinical setting. A CMV strain with a previously unrecognized UL97 mutation N597D was identified in the blood of a heart transplant recipient who experienced a persistent CMV infection with high viral loads accompanying pain and fever while receiving valganciclovir (valGCV) therapy. The N597D mutation was transferred by mutagenesis to an antiviral sensitive CMV strain for analysis of antiviral susceptibility by standardized phenotypic assay. Recombinant phenotyping showed N597D conferred a less than 2-fold increase in GCV IC50 compared to the sensitive control strain. Despite the presence of this mutation, valGCV eventually resolved the infection after six weeks of therapy. A subsequent CMV reactivation was also responsive to valganciclovir. This case illustrates the diversity of UL97 mutations in the codon segment 590–607 usually associated with GCV resistance, with some mutations producing minimal levels of resistance that do not preclude a therapeutic response to the drug. Accurate interpretation of genotypic test results ultimately requires experimental determination of the level of resistance conferred by newly discovered UL97 mutations.

Keywords: human cytomegalovirus, heart transplant, protein kinase, antiviral resistance

The introduction of antiviral agents for the treatment of CMV infection and disease has significantly reduced morbidity and mortality. Both prophylaxis and preemptive therapy are used for the prevention of CMV disease and reduction of opportunistic infection [Singh, 2006; Snydman, 2006]. However, the emergence of antiviral resistance is associated with treatment failure and progression of CMV disease [Limaye et al., 2000]. The consequences of antiviral resistance are complex and it has been suggested that CMV antiviral resistance may develop more rapidly in severely immunocompromised patients [Wolf et al., 1998], and persist in the absence of antiviral selective pressure [Iwasenko et al., 2007]. The CMV UL97 protein kinase phosphorylates nucleoside analogues such as ganciclovir (GCV) [Littler et al., 1992; Sullivan et al., 1992] and as such the UL97 protein kinase has an essential role in GCV susceptibility and is commonly mutated in GCV-resistant CMV strains. Although mutations of DNA polymerase catalytic subunit (UL54) can lead to the development of antiviral resistance, prevalence studies estimate that UL97 mutations are present in over 90% of GCV resistant strains (reviewed in [Gilbert and Boivin, 2005]). UL97 mutations conferring GCV resistance are clustered at codons 460, 520 and 590–607, with mutations M460V, A594V and L595S the most common [Chou et al., 2002]. These common GCV-resistant UL97 mutations confer a 5- to 10-fold increase in GCV 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) compared to antiviral sensitive strains [Chou et al., 2005; Chou et al., 2002]. However, the more recent availability of oral GCV and now valganciclovir (valGCV), which may result in reduced levels of GCV in the blood, have coincided with increased rates of other UL97 mutations, such as C592G, that confer lower levels of GCV resistance (2- to 3-fold increases above baseline) to CMV strains [Chou et al., 2002]. Here, we report the identification and characterization of a previously unrecognized UL97 mutation, N597D.

A 35-year-old male with Hepatitis C underwent a heart transplant for idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. The recipient was seronegative for CMV at the time of transplant but received a heart from a seropositive donor (D+R−). Post-transplant immunosuppressive therapy included cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, corticosteroids and prednisolone.

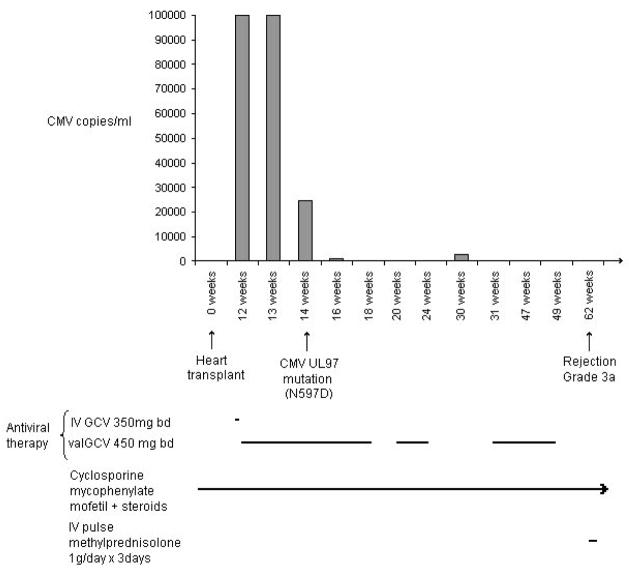

CMV infection was initially diagnosed after the patient presented with pain and fever at 12 weeks post-transplant. He was shown to have a viral load in plasma of >1×105 copies/ml (Figure I) using the Roche COBAS® AMPLICOR™ CMV MONITOR assay (analytical range 6×102 – 1×105 per ml plasma). Intravenous (IV) GCV was given at a dose of 350mg bd for one day, followed by 450mg bd valGCV orally. The CMV load remained at >1×105 copies/ml after one week of therapy, but decreased to 2.5×104 copies/ml 14 weeks post-transplant, and decreased further to 1.2×103 copies/ml by 16 weeks post-transplant. ValGCV was ceased at 18 weeks post-transplant. Two weeks later, CMV reactivation was suspected with the recurrence of symptoms, despite the virus remaining undetectable by PCR, prompting further treatment with 450mg bd valGCV at 20 to 24 weeks post-transplant. CMV was subsequently detected at 30 weeks post-transplant (viral load = 2.4×103 copies/ml), and 450mg bd valGCV was given from 31 to 49 weeks post-transplant. CMV was not detected by nucleic acid testing during this last period of valGCV therapy. CMV has not been detected since this time and the patient has had no further episodes of CMV-related symptoms.

Figure I. CMV status and drug therapy post transplant in a heart transplant recipient.

Columns indicate CMV positive specimens and viral load. Lines indicate duration of antiviral or immunosuppressive therapy. An arrow at the end of a line indicates ongoing therapy. Not to scale.

Genotypic antiviral resistance testing was carried out on EDTA blood specimens sent by attending physicians to Virology Research, Prince of Wales Hospital with patient consent. DNA was extracted from plasma using the MagNA Pure DNA extraction kit and workstation (Roche). Nested PCR and sequencing of relevant regions of UL97 protein kinase and UL54 DNA polymerase was performed as described previously [Iwasenko et al., 2007; Scott et al., 2004]. A specimen taken at 14 weeks post-transplant identified an AAC→GAC mutation that translates to an asparagine (N) to aspartic acid (D) change at codon 597 of the UL97 protein kinase. The N597D substitution was present in forward and reverse sequences. Sequencing of re-extracted and re-amplified UL97 also confirmed the presence of the N597D mutation. The N597D mutation was detected in the first specimen available for resistance testing and CMV was not detected in two other available specimens taken at 33 and 35 weeks post-transplant. The N597D mutation was suspected to confer GCV resistance because it resides within UL97 codon segment 590–607 where many other GCV resistance mutations have been described [Chou et al., 2002], and codon 597 is not recognized as a locus of natural sequence polymorphism [Lurain et al., 2001]. A similar uncharacterized mutation (N597I) was previously reported in a highly immunocompromised child together with other substitutions in the 590–607 region [Wolf et al., 1998].

The UL97 mutation N597D was characterized by recombinant phenotyping, as described previously [Chou et al., 2005]. Briefly, site-directed mutagenesis was performed using HPLC-purified primers and QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) to alter wild-type (AD169) UL97 sequence cloned into pGEM-T (Promega) so that it contained the AAC→GAC (N597D) mutation. After sequence confirmation of the mutated clone, the N597D mutation was transferred to a reference CMV laboratory strain (T2211) that had been modified from AD169 to contain unique restriction sites and a reporter gene expressing secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP). The GCV susceptibility of the N597D recombinant virus (T3048), a second recombinant virus containing a known low-grade GCV-resistant mutation C592G (T2258) and the antiviral sensitive parent strain (T2211) were assessed on the basis of the GCV concentration that reduced SEAP activity within culture supernatant by 50% (IC50) [Chou et al., 2005].

Phenotypic analysis showed the GCV IC50 of the N597D recombinant strain (T3048) was only 1.4-fold higher than the IC50 of the antiviral sensitive parent strain (T2211) (Table I). In comparison, the GCV IC 50 of the recombinant strain containing GCV-resistant mutation C592G (T2258) was 2.3-fold higher than the sensitive strain. Therefore, mutation N597D confers a minimal or negligible level of GCV resistance compared with the mutation C592G, which in turn confers a lower level of GCV resistance than the common M460V, A594V and L595S mutations [Chou et al., 2005].

Table I.

GCV susceptibility of a CMV recombinant strain containing UL97 mutation N597D compared with wild-type CMV and a known GCV resistant strain

| Virus | UL97 Mutation | GCV IC50 (μM)* | IC50 Fold increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| T2211 | - | 1.10 ± 0.04 | - |

| T3042 | N597D | 1.52 ± 0.13 | 1.4 |

| T2258 | C592G | 2.55 ± 0.2 | 2.3 |

mean ± SEM of 10 assays

Antiviral resistant CMV mutants generally have some loss of growth fitness, particularly strains with UL54 mutations [Springer et al., 2005]. SEAP growth curves were set up on two occasions using methods previously described [Chou et al., 2005] and the N597D mutant T3048 showed slight retardation of growth as compared with the wild type parental strain T2211 on one occasion but not on the other. This is typical of findings with known UL97 GCV resistant mutants, which grow well in cell culture, in contrast to UL97 genetic knockout viruses, which are severely growth-impaired [Prichard et al., 1999].

The minimal change in GCV sensitivity conferred by N597D is consistent with the clinical outcome of this case. Six weeks of valGCV therapy successfully reduced the CMV load below detection limits. After valGCV was withdrawn, one episode of CMV reactivation was confirmed, which responded to additional valGCV therapy. This demonstrates that GCV or valGCV treatment of adequate dose and duration can be used to treat CMV infection in the presence of certain UL97 mutations, even when they occur within the 590–607 locus.

N597D was detected after two weeks of valGCV therapy, which would be an early onset for a drug resistance mutation. The genotypes of CMV strains at earlier time points of the infection were unable to be established with only a single blood specimen available for resistance testing. It is therefore unclear whether N597D was selected via GCV exposure or is a previously unrecorded natural UL97 sequence polymorphism. However, there are no reports of N597D being present in antiviral sensitive strains from untreated patients [Chou, 1999]. Indeed, D605E is the only amino acid sequence variation within the 590–607 locus that has been described in baseline isolates [Chou, 1999].

The detection of N597D adds to diverse findings of UL97 mutations in the codon 590–607 region [Chou et al., 2002; Gilbert and Boivin, 2005]. While this region is highly associated with mutations that confer clinically significant GCV resistance, several mutations in this region, such as A591V, C592G, A594T, and E596G, are known to confer low-levels of GCV resistance [Chou et al., 2005; Chou et al., 2002] that may not preclude successful therapy with GCV or valGCV. However, there is potential for these low level resistant strains to facilitate the development of secondary mutations within UL97 or the UL54 DNA polymerase that lead to increased levels of drug resistance, as has been shown for C592G [Chou et al., 2005]. Therefore, it is advisable in this setting to use full therapeutic doses of GCV or valGCV, with attention to pharmacokinetic factors including dosing intervals, renal and gastrointestinal function. Regular virologic and genotypic monitoring is especially important in high-risk patients where the frequent or rapid emergence of antiviral resistant CMV strains has been documented, such as lung transplant recipients and immunocompromised children [Gilbert and Boivin, 2005; Wolf et al., 1998].

The current case report emphasizes the need for recombinant phenotyping of previously unrecognized mutations to confirm their role in antiviral resistance and the level of resistance conferred. While UL97 or UL54 mutations that confer drug resistance can be present without associated clinical symptoms [Boivin et al., 2005] extended antiviral therapy is commonly required for CMV infection, and the detection of new viral mutations often prompts a switch to alternate therapies such as foscarnet, which can have major implications for patient management, including prolonged intravenous infusions and added toxicity. As it turned out, the N597D mutation did not confer clinically significant GCV resistance and was adequately treated with oral valGCV. Increased understanding of differences in the degree of resistance conferred by various UL97 and DNA polymerase mutations will improve therapeutic decision-making when the less common mutations are encountered.

Acknowledgments

U.S. NIH AI-39938 and Department of Veterans Affairs.

Abbreviations

- CMV

human cytomegalovirus

- GCV

ganciclovir

- valGCV

valganciclovir

- SEAP

secreted alkaline phosphatase

Footnotes

The authors do not have a commercial association or other affiliation that may pose a conflict of interest.

References

- Boivin G, Goyette N, Gilbert C, Covington E. Analysis of cytomegalovirus DNA polymerase (UL54) mutations in solid organ transplant patients receiving valganciclovir or ganciclovir prophylaxis. J Med Virol. 2005;77:425–429. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou S. Antiviral drug resistance in human cytomegalovirus. Transpl Infect Dis. 1999;1:105–114. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3062.1999.010204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou S, Van Wechel LC, Lichy HM, Marousek GI. Phenotyping of cytomegalovirus drug resistance mutations by using recombinant viruses incorporating a reporter gene. Antimicrobiol Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2710–2715. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2710-2715.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou S, Waldemer RH, Senters AE, Michels KS, Kemble GW, Miner RC, Drew WL. Cytomegalovirus UL97 phosphotransferase mutations that affect susceptibility to ganciclovir. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:162–169. doi: 10.1086/338362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oña Navarro M, Melón S, Méndez S, Iglesias B, Palacio A, Bernardo M, Rodriguez-Lambert J, Gómez E. Assay of cytomegalovirus susceptibility to ganciclovir in renal and heart transplant recipients. Transpl Int. 2002;15:570–573. doi: 10.1007/s00147-002-0453-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert C, Boivin G. Human cytomegalovirus resistance to antiviral drugs. Antimicrobiol Agents Chemother. 2005;49:873–883. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.873-883.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert C, LeBlanc M, Boivin G. Case study: rapid emergence of a cytomegalovirus UL97 mutant in a heart-transplant recipient on preemptive ganciclovir therapy. Herpes. 2001;8:80–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasenko JM, Scott GM, Ziegler JB, Rawlinson WD. Emergence of multiple antiviral resistant CMV strains in a highly immuncompromised patient. J Clin Virol. 2007;40:152–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limaye AP, Corey L, Koelle DM, Davis CL, Boeckh M. Emergence of ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus diseases among recipients of solid-organ transplants. Lancet. 2000;356:645–649. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02607-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littler E, Stuart AD, Chee MS. Human cytomegalovirus UL97 open reading frame encodes a protein that phosphorylates the antiviral nucleoside analogue ganciclovir. Nature. 1992;358:160–162. doi: 10.1038/358160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurain NS, Weinberg A, Crumpacker CS, Chou S. Sequencing of cytomegalovirus UL97 gene for genotypic antiviral resistance testing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2775–2780. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.10.2775-2780.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prichard MN, Gao N, Jairath S, Mulamba G, Krosky P, Coen DM, Parker BO, Pari GS. A recombinant human cytomegalovirus with a large deletion in UL97 has a severe replication deficiency. J Virol. 1999;73:5663–5670. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5663-5670.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott GM, Isaacs MA, Zeng F, Kesson AM, Rawlinson WD. Cytomegalovirus antiviral resistance associated with treatment induced UL97 (protein kinase) and UL54 (DNA polymerase) mutations. J Med Virol. 2004;74:85–93. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N. Antiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus in transplant recipients: advantages of preemptive therapy. Rev Med Virol. 2006;16:281–287. doi: 10.1002/rmv.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snydman D. The case for cytomegalovirus prophylaxis in solid organ transplantation. Rev Med Virol. 2006;16:289–295. doi: 10.1002/rmv.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer K, Chou S, Li S, Giller R, Quinones R, Shira J, Weinberg A. How evolution of mutations conferring drug resistance affects viral dynamics and clinical outcomes of cytomegalovirus-infected hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:208–213. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.208-213.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan V, Talarico CL, Stanat SC, David M, Coen DM, Biron KK. A protein kinase homologue controls phosphorylation of ganciclovir in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells [erratum for Nature 1992 Jul 9;358:162–4; PMID: 1319560] Nature. 1992;359:85. doi: 10.1038/358162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DG, Yaniv I, Honigman A, Kassis I, Schonfeld T, Ashkenazi S. Early emergence of ganciclovir-resistant human cytomegalovirus strains in children with primary combined immunodeficiency. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:535–538. doi: 10.1086/517468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]