Abstract

Antigen-specific gamma interferon (IFN-γ) has been demonstrated to participate in protection against Bordetella pertussis infection. Circulating mononuclear cells from B. pertussis-infected and from pertussis-vaccinated infants secrete high amounts of IFN-γ after in vitro stimulation by B. pertussis antigens, but with a large variation in the secreted IFN-γ levels between individuals. We show here that the inhibition of the specific IFN-γ response can be at least partially attributed to IL-10 secretion by monocytes. This IL-10 secretion was not associated with polymorphisms at positions −1082, −819, and −592 of the IL-10 gene promoter, suggesting that other genetic or environmental factors affect IL-10 expression and secretion.

Bordetella pertussis, the gram-negative bacterium that causes whooping cough, still infects up to 40 million individuals each year and is responsible for around 300,000 annual deaths (27), despite a high worldwide vaccine coverage. However, the immune mechanism of protection against B. pertussis and, consequently, the optimal way to administer pertussis vaccines, especially in young children, are still insufficiently understood. The humoral side of the adaptive immunity was initially considered the main effector of protection against B. pertussis, but there appears to be no direct correlation between serum antibody titers and protection (6, 7). The contribution of specific cellular immune responses, and especially of gamma interferon (IFN-γ), to the protection against B. pertussis has more recently been demonstrated. In mice, recovery from infection is associated with the development of B. pertussis-specific Th1 cells, and the adoptive transfer of these Th1 cells from convalescent mice confers protection to the recipient mice (18). In addition, IFN-γ receptor knockout mice develop lethal disseminated infection (12). The protective role of IFN-γ is more difficult to demonstrate in humans but is strongly suggested by several lines of indirect evidence. T lymphocytes from both naturally infected children and from vaccinated subjects secrete IFN-γ in response to in vitro stimulation with B. pertussis antigens (15, 16, 22). This specific IFN-γ secretion is at least partially induced by interleukin-12 (IL-12), as suggested by the strong correlation between B. pertussis-specific IFN-γ and IL-12 secretion levels, both in infected and in vaccinated infants (15, 16). However, although most vaccinated infants develop specific Th1 responses, these responses are very heterogeneous, according to the type of pertussis vaccine, and they are sometimes lower than detectable levels in peripheral blood. Acquired immune responses are generally modulated by responses from the innate immune system, and specific IFN-γ responses are often modulated by IL-10. This prototypical regulatory cytokine, produced by monocytes and dendritic cells, as well as by T lymphocytes, has been shown to dampen the specific T-cell responses to several pathogens (8, 17, 20). Interindividual variations in IL-10 production can be a consequence of a genetic polymorphism (5, 25, 26), as well as numerous other factors (8, 9, 17, 21).

Therefore, we investigated here whether IL-10 secretion in infants vaccinated with an acellular vaccine against B. pertussis plays a role in the high interindividual variations of the specific IFN-γ responses to B. pertussis antigens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects included in the study.

A total of 63 infants between 2 and 13 months of age were included in the study after we obtained informed consent from their parents and approval from the ethical committee of the Saint-Pierre Hospital (Brussels, Belgium), where the children were recruited. All infants had already been included in previous studies on cellular immune responses induced by pertussis vaccine administrations (16) and had been, as previously described, vaccinated against pertussis, tetanus, diphtheria, poliomyelitis, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and hepatitis B virus according to the recommendations in Belgium. At 2, 3, and 4 months of age these infants received the acellular vaccine Tetravac (sanofi pasteur, Lyon, France), used to reconstitute just before the administration the lyophilized tetanus toxoïd-conjugated H. influenzae type b polysaccharide vaccine (Act-Hib; sanofi pasteur). The recombinant hepatitis B virus vaccine (HBVAXPRO; sanofi pasteur, Lyon, France) was injected at a separate site at 3 and 4 months of age. The enrolled infants were born from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected mothers but they were all HIV negative. Until definite confirmation of their HIV-negative status, they received a 6-week preventive therapy with zidovudine. Blood samples were collected before the first vaccine administration at 2 months of age (n = 42) and at 3 (n = 28) and/or 6 (n = 24) months of age, i.e., 1 month after the first vaccine dose and/or 2 months after the third vaccine dose. For some infants (n = 5) an additional blood sample was collected just before the administration of the booster dose, at around 13 months of age. For obvious ethical reasons, blood samples could not be collected at each time point from all the infants, and not all the experiments could be performed on each blood sample due to the limited amount of blood available.

Antigens, mitogen, and blocking antibodies for cellular immune assays.

Filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA) was purified from pertussis toxin (PT)-deficient B. pertussis BPRA (2) and PT from FHA-deficient B. pertussis BPDR-RE, as previously described (1). PT was heated for 20 min at 80°C to inactivate its mitogenic activity. Antigen concentrations were estimated by using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) was purchased from Remel (Lenexa, KS).

Concentrations of 1 μg/ml for B. pertussis antigens and 2 μg/ml for PHA were used for the in vitro stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). When indicated, blocking anti-human IL-10 antibody (clone 23738.111; R&D Systems Europe, Abington, United Kingdom) or a mouse immunoglobulin G2b isotype control (clone 20116; R&D Systems Europe, United Kingdom) was added to the culture medium at 5 μg/ml. For optimal utilization of the blood amount available, these additional experiments were performed on blood samples collected from 3-month-old infants, whereas others (see below) were performed on blood samples collected from 6- and 13-month-old infants.

Cell isolation and culture and cytokine determinations.

PBMC were obtained by density gradient centrifugation of the blood on Lymphoprep (Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway). Cells were cultured at 2 × 106/ml in complete RPMI medium in the presence of antigens or mitogen at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere, as previously described (15). Concentrations of IL-10 (IL-10 Cytoset ELISA kit; BioSource International, Camarillo, CA), IL-12p70 (human IL-12p70 Quantikine HS ELISA kit; R&D Systems Europe, United Kingdom), and IFN-γ (IFN-γ Cytoset ELISA kit; BioSource International) were measured in the 24-h (for IL-10 and IL-12p70) or 72-h (for IFN-γ) supernatants, using sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Cytokine concentrations were calculated using KC4 software (BRS, Drogenbos, Belgium). The sensitivity limits of the assays were 25 pg/ml for IFN-γ and IL-10 and 0.5 pg/ml for IL-12p70. When detectable, cytokine concentrations obtained under nonstimulated conditions were subtracted from those obtained for mitogen- or antigen-stimulated cells.

Monocyte depletions.

Monocytes were depleted from whole blood samples by positive selection using anti-CD36 antibodies (RosetteSep; StemCell Technologies, Grenoble, France). This was followed by density gradient centrifugation on Lymphoprep (Nycomed Pharma, Norway). The effectiveness of the monocyte depletion was controlled by flow cytometry (FACSCanto I; BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) using peridinin chlorophyll protein-conjugated anti-CD3, fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD8, allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD4, and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD14 monoclonal antibodies (BD Biosciences). Percentages of remaining CD14+ cells were always lower than 0.1% of the PBMC when analyzed with FlowJo software (Ashland, OR). These experiments were performed on blood samples from 6- and 13-month-old infants, as the amount of blood available from younger infants was insufficient.

IL-10 genotyping.

Genomic DNA was extracted from PBMC using the QIAmp DNA blood minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The three biallelic IL-10 promoter polymorphisms were detected by PCR using primers to amplify a short fragment of DNA containing the polymorphism. PCR for position −592 was performed using primers 5′-CCT AGG TCA CAG TGA CGT GG-3′ and 5′-GGT GAG CAC TAC CTG ACT AGC-3′, and for position −819 primers 5′-TCA TTC TAT GTG CTG GAG ATG G-3′ and 5′-TGG GGG AAG TGG GTA AGA GT-3′, as described in reference 4. For position −1082, primers 5′-CCG CAA CCC AAC TGG CT-3′ and 5′-TCT TAC CTA TCC CTA CTT CC-3′ were used. The −592 and −819 fragments were amplified by using the HotStar HiFidelity PCR system (Qiagen, Germany) in a volume of 50 μl containing 20 ng of template DNA. The −1082 fragment was amplified by using the HotStar HiFidelity PCR system (Qiagen, Germany) in a volume of 50 μl containing 100 ng of template DNA. PCR was performed using a 2400 Gene Amp PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and the parameters for thermocycling were as follows: denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for positions −592 and −819 or at 53°C for position −1082 for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min. This was followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

The two alleles at each polymorphic site were identified by incubating 1 μg of each PCR product for 1 h at 55°C with 1 U of RsaI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, United Kingdom) for the −592 PCR product, at 37°C with 1 U of MaeIII (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for the −819 PCR product, and at 37°C with 1 U of MnlI (New England BioLabs) for the −1082 PCR product, after concentration of the PCR products with a Microcon centrifugal filter (YM-30; Millipore S.A., Brussels, Belgium), followed by electrophoresis on agarose gels (2%).

Statistical analysis.

The statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The significance of differences between two groups was determined using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test or Wilcoxon matched pairs test, whereas the significance of the correlation was analyzed by the nonparametric Spearman test.

RESULTS

FHA- and PT-induced IFN-γ secretions.

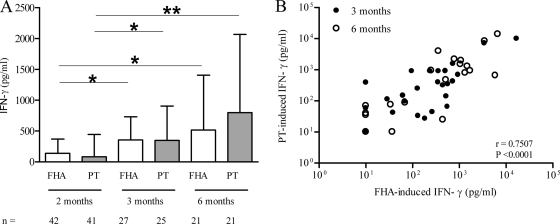

As previously reported (16), the PBMC isolated from 3- and 6-month-old vaccinated infants secreted more IFN-γ in response to in vitro stimulation with FHA or PT than those cells collected from unvaccinated 2-month-old infants (Fig. 1A). However, there was a large heterogeneity of the IFN-γ concentrations detected in cell culture supernatants, with some infants mounting better Th1 responses than others. The heterogeneities of the IFN-γ responses were similar for FHA and for PT, and the responses correlated well (r = 0.7507; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

FHA- and PT-induced IFN-γ secretion in 3- and 6-month-old vaccinated infants. PBMC were in vitro stimulated for 72 h with FHA or PT as indicated, and the IFN-γ concentrations in cell culture supernatants were measured. (A) Kinetics of the FHA- and PT-stimulated IFN-γ responses in 3-month-old infants (1 month after the first vaccine injection) or in 6-month-old infants (2 months after the third vaccine injection) were compared to those obtained in prevaccinated infants (2 months old). Results shown are medians and 75th percentiles. n, number of infants tested. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (B) Correlation between FHA- and PT-induced IFN-γ secretion by PBMC from 3-month-old (n = 25) and 6-month-old (n = 20) vaccinated infants. The nonparametric Spearman test was used to analyze the correlation (r = 0.7507; P < 0.0001).

Spontaneous IL-10 secretion and relationship with FHA- and PT-induced IFN-γ and IL-12p70 secretions.

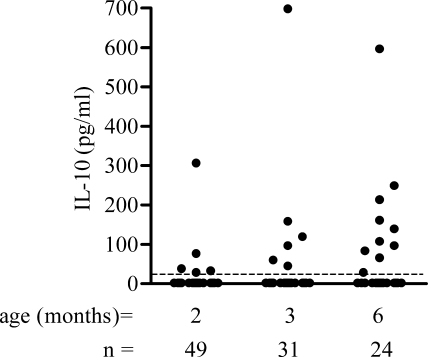

Because of the immunoregulatory role of IL-10, we investigated whether this cytokine could play a role in the highly variable IFN-γ responses to FHA and PT by the PBMC from vaccinated infants. We analyzed the spontaneous IL-10 secretion in these infants by measuring the IL-10 concentrations released by their PBMC after 24 h of in vitro culture in the absence of any stimulation. Whereas these concentrations were low for 2-month-old infants (only 5/49 infants had detectable levels), they were higher in 3- and 6-month-old infants, with 6/31 (19%) and 10/24 (42%) infants having detectable levels at 3 and 6 months, respectively (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

IL-10 secretion by PBMC from 2-, 3-, and 6- month-old infants in the absence of antigenic stimulation. IL-10 concentrations were measured in cell culture supernatants collected after 24 h. The dotted horizontal line indicates the sensitivity limit of the assay. n, number of samples tested.

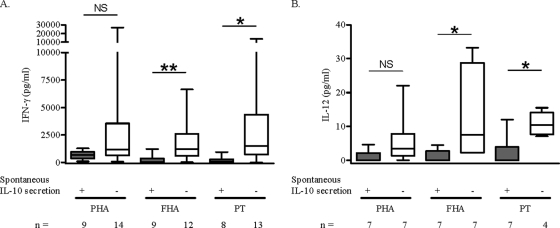

Since the PBMC from a substantial proportion, especially of the 6-month-old infants, spontaneously secreted IL-10, we studied the relationship of the FHA- and PT-induced IFN-γ secretions by the PBMC with that of the IL-10 secretion in 6-month-old infants. As shown in Fig. 3A, PT- and FHA-induced IFN-γ secretions were significantly lower in the group of infants with detectable levels of spontaneous IL-10 secretion (group I) than in those with no detectable secretion of IL-10 (group II) (P = 0.0025 and P = 0.0138 for FHA and PT, respectively). The PBMC from group I also secreted lower IFN-γ concentrations in response to PHA than those from infants of group II, although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.0727). The analysis of the individual data for the infants with a three-time point longitudinal follow-up is given in Table 1 and illustrates at an individual level that a high spontaneous IL-10 secretion level was associated with a low antigen-specific IFN-γ response.

FIG. 3.

PHA-, FHA-, and PT-induced IFN-γ (A) and IL-12p70 (B) secretion. PBMC collected from 6-month-old vaccinated infants were in vitro stimulated with PHA, FHA, or PT. IFN-γ and IL-12p70 concentrations were measured in cell culture supernatants after 72 h and 24 h, respectively. Infants were divided into two groups according to the presence (+; group I) or the absence (−; group II) of spontaneous IL-10 secretion by PBMC. The medians, 25th and 75th percentiles, and the ranges of cytokine concentrations are represented. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test was used to calculate statistical differences. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; NS, not significant; n, number of samples tested.

TABLE 1.

Longitudinal follow-up of spontaneous IL-10 secretion and antigen-induced IFN-γ secretion

| Infant no. | Cytokine concn (pg/ml) in children at agea: |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 mos |

3 mos |

6 mos |

|||||||

| IL-10 | IFN-γ |

IL-10 | IFN-γ |

IL-10 | IFN-γ |

||||

| FHA | PT | FHA | PT | FHA | PT | ||||

| 1 | <25 | 66 | 182 | <25 | 263 | 44 | 106 | 69 | 88 |

| 2 | <25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | 38 | 42 | 595 | <25 | <25 |

| 3 | <25 | 68 | <25 | <25 | 128 | 251 | 212 | 34 | 75 |

| 4 | <25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | NDb | ND | <25 | ND | 4,712 |

| 5 | <25 | ND | 82 | <25 | 355 | 906 | 82 | <25 | 35 |

| 6 | <25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | ND | ND | <25 | 1,092 | 1,963 |

| 7 | <25 | <25 | <25 | <25 | 445 | 318 | <25 | 1,046 | 1,497 |

| 8 | <25 | <25 | 33 | <25 | <25 | 58 | <25 | 37 | <25 |

IL-10 or IFN-γ concentrations were measured in the cell culture supernatants collected after 24 h of in vitro culture of PBMC without any added stimulant (for IL-10) or after 72 h of in vitro culture in the presence of FHA or PT (for IFN-γ).

ND, not done.

A similar association was found between the spontaneous IL-10 secretion and the antigen-specific IL-12p70 secretion levels (for FHA, P = 0.0111; for PT, P = 0.0242) (Fig. 3B), which was expected, since B. pertussis antigen-induced IFN-γ and IL-12p70 secretion levels are correlated (16).

Effect of blocking anti-IL-10 antibodies.

To demonstrate the inhibitory role of IL-10 on the B. pertussis antigen-specific IFN-γ secretion by the PBMC from vaccinated infants, we compared for 11 infants the FHA-induced IFN-γ concentrations secreted by FHA-stimulated PBMC after 72 h of culture in the presence or absence of a blocking anti-IL-10 antibody. As shown in Fig. 4, the IFN-γ concentrations were significantly higher in the presence of an anti-IL-10 antibody (P = 0.002) and augmented in almost all the children, increasing up to 80-fold, compared to the results obtained in the absence of an anti-IL-10 antibody. In contrast to the anti-IL-10 antibody, the addition of a control isotype antibody had no effect on the FHA-induced IFN-γ secretion (medians [25th to 75th percentiles], 400 pg/ml [74 to 2,399 pg/ml] versus 878 pg/ml [108 to 3,318 pg/ml] without and with the control isotype, respectively; nonsignificant difference). Due to the limited amount of blood available, the effect of the blocking anti-IL-10 antibody on the PT-induced IFN-γ response was analyzed only for 5/11 infants, and these experiments gave similar results as those obtained for the FHA-induced IFN-γ response (data not shown). These results indicate that IL-10 plays a role in the low IFN-γ responses to FHA and PT in vaccinated infants who respond poorly to this antigen.

FIG. 4.

Effects of anti-IL-10 blocking antibodies on the FHA-induced IFN-γ secretion by PBMC from 3-month-old vaccinated infants. PBMC were in vitro stimulated with FHA, with or without blocking anti-IL-10 antibodies. IFN-γ concentrations were measured in cell culture supernatants after 72 h. The nonparametric Wilcoxon matched pairs test was used to calculate statistical differences. **, P < 0.01.

Cellular source of the spontaneous IL-10 secretion.

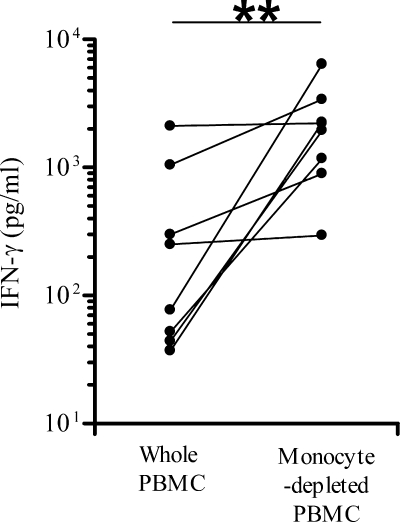

As monocytes represent the major source of IL-10 (23), we compared the IFN-γ concentrations induced by FHA stimulation in whole PBMC suspensions with those of monocyte-depleted cell suspensions. The IFN-γ concentrations measured after 72 h of culture were significantly higher for the monocyte-depleted PBMC compared to the whole PBMC (P = 0.0078), indicating that the monocytes were the major source of IFN-γ suppression in this system (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Effects of monocyte depletion on FHA-induced IFN-γ secretion by PBMC from 6- and 13-month-old vaccinated infants. IFN-γ concentrations induced by FHA stimulation in whole PBMC suspensions and in monocyte-depleted cell suspensions were measured in cell culture supernatants after 72 h. The nonparametric Wilcoxon matched pairs test was used to calculated statistical differences. **, P < 0.01.

IL-10 polymorphisms.

Since the PBMC of only some of the infants in this study spontaneously secreted detectable levels of IL-10 and, consequently, low IFN-γ concentrations upon stimulation with FHA and PT, we investigated whether these differences could be linked to genetic polymorphisms of the IL-10 gene promoter which have been reported to influence the constitutive IL-10 production (14, 24, 25).

The polymorphisms of the IL-10 gene promoter described for three base pairs at positions −1082, −819, and −592 were analyzed for 19 infants, including 6 who spontaneously secreted IL-10 at 2 or 6 months of age (Table 2). Genotypes were defined previously as “low” (ATA/ATA, ACC/ATA, and ACC/ACC), “intermediate” (GCC/ACC and GCC/ATA), and “high” IL-10 producers (GCC/GCC) (4, 25). The high IL-10 producer genotype was found in 1/3 infants secreting IL-10 at 2 months and in 0/3 infants with IL-10 secretion at 6 months. The five other IL-10-secreting infants comprised four low IL-10 producer genotypes and one intermediate producer, indicating that this spontaneous IL-10 secretion in infants was not influenced by the IL-10 genotype analyzed.

TABLE 2.

IL-10 polymorphisms

| Phenotype | Genotype | Spontaneous IL-10 secretion (pg/ml) at age: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 mos | 6 mos | ||

| Low | ATA/ATA | <25 | 27 |

| <25 | NDa | ||

| <25 | ND | ||

| 75 | ND | ||

| ACC/ATA | <25 | <25 | |

| <25 | 82 | ||

| <25 | ND | ||

| 31 | ND | ||

| <25 | ND | ||

| Intermediate | GCC/ATA | <25 | 95 |

| <25 | <25 | ||

| <25 | ND | ||

| <25 | ND | ||

| GCC/ACC | <25 | <25 | |

| <25 | <25 | ||

| <25 | <25 | ||

| High | GCC/GCC | 42 | <25 |

| <25 | ND | ||

| <25 | ND | ||

ND, not done.

DISCUSSION

Both specific antibodies and specific IFN-γ responses are necessary for optimal protection against B pertussis infection (11, 19). Therefore, most recent studies reporting on the immune responses of children vaccinated against pertussis describe both parameters. However, the optimal specific IFN-γ response that could be considered as appropriate for vaccine-induced protection has not yet been defined. In addition, large interindividual variations among the secreted B. pertussis-specific IFN-γ concentrations have been reported in several studies (3, 9, 29), including this one.

These interindividual variations could be due to the fact that usually only circulating lymphocytes are analyzed and most antigen-specific IFN-γ-secreting T lymphocytes may be sequestered in other body sites, such as lymph nodes. Alternatively, in some cases the IFN-γ responses could be inhibited by regulatory mechanisms, such as regulatory T cells or inhibitory cytokines. As the infants with a low IFN-γ response to FHA also had a low IFN-γ response to PT, we hypothesized that these responses were depressed by immunomodulatory cytokines, such as IL-10. We found that at 6 months in vaccinated children with detectable amounts of spontaneous IL-10 secretion, the levels of IFN-γ secretion by FHA-stimulated PBMC were significantly lower than in age-matched vaccinated children with undetectable spontaneous IL-10 secretion. The levels of antigen-specific IFN-γ secretions were significantly increased by blocking IL-10 with specific antibodies. Furthermore, upon depletion of the monocytes from the PBMC, the lymphocytes from most of the low IFN-γ responders were able to secrete B. pertussis antigen-specific IFN-γ. These observations strongly suggest that the main source of the suppressive IL-10 is the circulating monocytes, although this was not directly demonstrated because of the lack of sensitivity of the available tools for cytometric analysis.

Considering that monocytes are the main IL-10-producing cells and since polymorphisms of the IL-10 gene promoter have been described to control the constitutive levels of IL-10 (24), we analyzed whether the known genetic polymorphisms of the IL-10 gene promoter could explain the spontaneous secretion of IL-10 in approximately one-third of the 6-month-old infants. However, whereas the polymorphism may be linked to IL-10 secretion at 2 months, this was not the case at 6 months, suggesting that other factors, including nongenetic factors, trigger this IL-10 secretion by the monocytes at 6 months. Commensal bacteria from the intestinal microflora, such as Escherichia coli, have been reported to induce the secretion of IL-10 by human monocytes, leading to low acquired T-cell-mediated immunity (8, 9). Similarly, some bacterial virulence factors, such as FHA, included in most acellular vaccines against pertussis, have been shown to induce IL-10 production and to inhibit IL-12 secretion by a macrophage cell line via an IL-10-dependent mechanism (17, 21). More recently, allergen extracts from cereal grains were reported to induce marked IL-10 production by PBMC (28). The monocytes were identified as the main source of IL-10 in response to cereal grain extracts, further stressing the importance of the innate, albeit induced immune responses.

As blood samples were collected between 2 and 6 months of age, the fact that all the children included in this study were born from HIV-infected mothers must be taken into account, although all children were HIV negative. Very few consistent data are available on the cellular immune responses in HIV-negative children born from HIV-positive mothers. Lee et al. compared the constitutive production of IL-10 by PBMC from HIV-infected infants (median age, 21 months) with that of HIV-uninfected infants exposed in utero (median age, <1 month) and did not detect any significant difference in the IL-10 production between groups (10). Moreover, a recent study quantified Th1 cytokine expression by Mycobacterium bovis BCG-specific T cells in HIV-infected or exposed but HIV-uninfected infants from 3 to 12 months of age (13). No differences in total cytokine expression or in IFN-γ-, IL-2-, or TNF-α-expressing CD4+ T cells were noted between the two groups of infants. These data allowed us to assume that the observed cellular immune responses in this study can be extrapolated to the general population, including that of HIV-unexposed infants.

The multiple mechanisms of fine modulation of acquired immune responses by the innate immune system indicate that optimal vaccine strategies should not only be based on vaccine components but should also take into consideration genetic as well as environmental factors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Fond de la Recherche Scientifique Médicale, by the European Commission, within the 5th Framework Program (contract number QLK2-CT-0429), and by sanofi pasteur. V.D. was supported by a fellowship from the Fond pour la Formation à la Recherche dans l'Industrie et dans l'Agriculture.

We also thank the participating parents and children whose collaboration formed the backbone of the study, Kaatje Smits and Françoise Villée for PCR advice, and Emanuelle Trannoy and Emmanuel Vidor for study support and for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 October 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso, S., K. Pethe, N. Mielcarek, D. Raze, and C. Locht. 2001. Role of ADP-ribosyltransferase activity of pertussis toxin in toxin-adhesin redundancy with filamentous hemagglutinin during Bordetella pertussis infection. Infect. Immun. 69:6038-6043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoine, R., and C. Locht. 1990. Roles of the disulfide bond and the carboxy-terminal region of the S1 subunit in the assembly and biosynthesis of pertussis toxin. Infect. Immun. 58:1518-1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausiello, C. M., F. Urbani, A. La Sala, R. Lande, and A. Cassone. 1997. Vaccine- and antigen-dependent type 1 and type 2 cytokine induction after primary vaccination of infants with whole-cell or acellular pertussis vaccines. Infect. Immun. 65:2168-2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards-Smith, C. J., J. R. Jonsson, D. M. Purdie, A. Bansal, C. Shorthouse, and E. E. Powell. 1999. Interleukin-10 promoter polymorphism predicts initial response of chronic hepatitis C to interferon alfa. Hepatology. 30:526-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eskalde, J., G. Gallgher, C. L. Verweij, V. Keijsers, R. G. J. Westendorp, and T. W. J. Huizinga. 1998. Interleukin 10 secretion in relation to human IL-10 locus haplotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:9465-9470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giuliano, M., P. Mastrantonio, A. Giammanco, A. Piscitelli, S. Salmaso, and S. G. Wassilak. 1998. Antibody responses and persistence in two years after immunization with two acellular vaccines and one whole-cell vaccine against pertussis. J. Pediatr. 132:983-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustafsson, L., H. O. Hallander, P. Olin, E. Reizenstein, and J. Storsaeter. 1996. A controlled trial of a two-component acellular, a five-component acellular and a whole-cell pertussis vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 334:349-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hessle, C., L. A. Hanson, and A. E. Wold. 2000. Interleukin-10 produced by the innate immune system masks in vitro evidence of acquired T-cell immunity to E.coli. Scand. J. Immunol. 52:13-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karlsson, H., C. Hessle, and A. Rudin. 2002. Innate immune responses of human neonatal cells to bacteria from the normal gastrointestinal flora. Infect. Immun. 70:6688-6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, B.-N., J.-G. Lu, M. W. Kline, M. Paul, M. Doyle, C. Kozinetz, W. T. Shearer, and J. M. Reuben. 1996. Type 1 and type 2 cytokine profiles in children exposed to or infected with vertically transmitted human immunodeficiency virus. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 3:493-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leef, M., K. L. Elkins, J. Barbic, and R. D. Shahin. 2000. Protective immunity to Bordetella pertussis requires both B cells and CD4+ T cells for key functions other than specific antibody production. J. Exp. Med. 191:1841-1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahon, B. P., B. J. Sheahan, F. Griffin, G. Murphy, and K. H. Mills. 1997. Atypical disease after Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection of mice with targeted disruptions of interferon-γ receptor or immunoglobulin μ chain genes. J. Exp. Med. 186:1843-1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mansoor, N., T. J. Scriba, M. de Kock, M. Tameris, B. Abel, A. Keyser, F. Little, A. Soares, S. Gelderbloem, S. Mlenjeni, L. Denation, A. Hawkridge, W. H. Boom, G. Kaplan, G. D. Hussey, and W. A. Hanekom. 2009. HIV-1 infection in infants severely impairs the immune response induced by Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 199:982-990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Márka, M., B. Bessenyei, M. Zeher, and I. Semsei. 2005. IL-10 promoter −1082 polymorphism is associated with elevated IL-10 levels in control subjects but does not explain elevated plasma IL-10 observed in Sjögren's syndrome in a Hungarian cohort. Scan. J. Immunol. 62:474-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mascart, F., V. Verscheure, A. Malfroot, M. Hainaut, D. Piérard, S. Temerman, A. Peltier, A.-S. Debrie, J. Levy, G. Del Giudice, and C. Locht. 2003. Bordetella pertussis infection in 2-month-old infants promotes type 1 T cell responses. J. Immunol. 170:1504-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mascart, F., M. Hainaut, A. Peltier, V. Verscheure, J. Levy, and C. Locht. 2007. Modulation of the infant immune responses by the first pertussis vaccine administrations. Vaccine 25:391-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGuirk, P., and K. H. Mills. 2000. Direct anti-inflammatory effect of a bacterial virulence factor: IL-10-dependent suppression of IL-12 production by filamentous hemagglutinin from Bordetella pertussis. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:415-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mills, K. H. G., A. Barnard, J. Watkins, and K. Redhead. 1993. Cell-mediated immunity to Bordetella pertussis: role of Th1 cells in bacterial clearance in a murine respiratory infection model. Infect. Immun. 61:399-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mills, K. H. 2001. Immunity to Bordetella pertussis. Microbes Infect. 3:655-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore, K. W., R. de Waal Malefyt, L. C. Coffman, and A. O'Garra. 2001. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:683-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross, P. J., E. C. Lavelle, K. H. G. Mills, and A. P. Boyd. 2004. Adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis synergizes with lipopolysaccharide to promote innate interleukin-10 production and enhances the induction of Th2 and regulatory T cells. Infect. Immun. 72:1568-1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan, M., G. Murphy, L. Gothefors, L. Nilsson, J. Storsaeter, and K. H. Mills. 1997. Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection in children is associated with preferential activation of type 1 T helper cells. J. Infect. Dis. 175:1246-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinke, J. W., and L. Borish. 2006. 3. Cytokines and chemokines. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 117:S441-S445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suarez, A., P. Castro, R. Alonso, L. Mozo, and C. Guttierrez. 2003. Interindividual variations in constitutive interleukin-10 messenger RNA and protein levels and their association with genetic polymorphisms. Transplantation. 75:711-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner, D. M., D. M. Williams, D. Sankaran, M. Lazarus, P. J. Sinnott, and I. V. Hutchinson. 1997. An investigation of polymorphism in the interleukin-10 gene. Eur. J. Immunogenet. 24:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westendorp, R. G. J., J. A. M. Langermans, T. W. J. Huizinga, A. H. Elouali, C. L. Verweij, D. I. Boomsma, and J. P. Vandenbrouke. 1997. Genetic influence on cytokine production and fatal meningococcal disease. Lancet 349:170-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. 2005. Immunization, vaccines and biologicals: pertussis. http://www.who.int/immunization/topics/pertussis/en/index/html.

- 28.Yamazaki, K., J. A. Murray, and H. Kita. 2008. Innate immunomodulatory effects of cereal grains through induction of IL-10. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 121:172-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zepp, F., M. Knuf, P. Habermehl, H. J. Schmitt, C. Rebsch, P. Schmidtke, R. Clemens, and M. Slaoui. 1996. Pertussis-specific cell-mediated immunity in infants after vaccination with a tricomponent acellular pertussis vaccine. Infect. Immun. 64:4078-4084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]