Abstract

Streptococcus gallolyticus (formerly known as Streptococcus bovis biotype I) is a low-grade opportunistic pathogen which is considered to be associated with colon cancer. It is thought that colon polyps or tumors are the main portal of entry for this bacterium and that heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) at the colon tumor cell surface are involved in bacterial adherence during the first stages of infection. In this study, we have shown that the histone-like protein A (HlpA) of S. gallolyticus is a genuine anchorless bacterial surface protein that binds to lipoteichoic acid (LTA) of the gram-positive cell wall in a growth phase-dependent manner. In addition, HlpA was shown to be one of the major heparin-binding proteins of S. gallolyticus able to bind to the HSPG-expressing colon tumor cell lines HCT116 and HT-29. Strikingly, although wild-type levels of HlpA appeared to contribute to adherence, coating of additional HlpA at the bacterial surface resulted in reduced binding to colon tumor cells. This may be explained by the fact that heparan sulfate and LTA compete for the same binding site in HlpA. Altogether, this study implies that HlpA serves as a fine-tuning factor for bacterial adherence.

The human gastrointestinal tract is the habitat for a large and dynamic bacterial community, which is essential for intestinal epithelial homeostasis and human health. In contrast, gut flora may also be of critical importance in gastrointestinal diseases, such as colon cancer (10). Although hundreds of microbial species reside in the human intestinal tract, only a systemic infection with the gram-positive gut bacterium Streptococcus gallolyticus (formerly known as Streptococcus bovis biotype I) has a well-known association with colon cancer (13, 20, 44). (S. gallolyticus has the highest association with colorectal cancer of all S. bovis biotypes. Unfortunately, not all studies have distinguished S. bovis biotypes. Therefore, we use the name S. bovis when the specific biotype is not known and S. gallolyticus only when it is certain that the authors refer to S. bovis biotype I.) This bacterium, which can normally be detected in the gastrointestinal tracts of about 10% of the human population (31), is considered to be a low-grade opportunistic pathogen that can establish infections only in individuals with damaged heart valves (endocarditis) or a compromised immune system (bacteremia). Interestingly, fecal carriage of S. bovis was shown to be increased about fivefold in patients with colon cancer, indicating that colon tumors constitute a preferential colonization niche for this bacterium (20). In addition, multiple studies have shown that in up to 60% of patients with S. bovis endocarditis or bacteremia a colon tumor was detected upon full bowel examination (44). This strongly suggests that a colon polyp or tumor is the main portal of entry for S. gallolyticus, which is underscored by the fact that patients with S. bovis endocarditis are significantly older than those with endocarditis due to other streptococci (15). Noticeably, this could mirror the increased frequency of tumors in the elderly population.

A first requirement to establish a bacterial infection is a dependable connection between bacterial adhesins and host surface structures to withstand microbial competition and mechanical cleansing processes within the intestinal tract (14, 39). It has been suggested that heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) present on intestinal epithelial cells are a target for S. bovis adherence and internalization, thereby participating in bacterial translocation across the intestinal epithelial barrier (12). Interestingly, the heparin-binding histone-like protein A (HlpA) from S. bovis was recently shown to be present in cell wall extracts and was a target of the humoral immune response in patients with colon cancer (38). Several other studies confirmed that this conserved bacterial protein from Streptococcus pyogenes, which is 95.6% identical to S. gallolyticus HlpA, had affinity for lipoteichoic acid (LTA), an intrinsic component of the gram-positive cell wall (22, 35, 43). Furthermore, proteomic analysis of the bacterial surface of S. pyogenes revealed that HlpA is a surface-linked protein (33). Taken together, these observations suggested that HlpA from S. gallolyticus is a so-called anchorless surface protein, which is a target of the humoral immune system upon infection and may mediate bacterial adherence to colon tumor cells by linking bacterial LTA to HSPG on colon epithelial cells.

Anchorless proteins comprise typical cytoplasmic proteins that are released by unknown mechanisms and reassociate with components of the bacterial cell wall or proteins at the bacterial surface (23, 36). To several of these anchorless surface proteins a secondary extracytoplasmic function has been assigned. For instance, alpha-enolase and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate of group A streptococci have the ability to bind to plasminogen and fibronectin on pharyngeal epithelial cells (2, 24-26). Similarly, these surface-exposed proteins from Streptococcus pneumoniae bind to and activate plasminogen and are important for tissue invasion and virulence (5).

Therefore, the main aim of this study was to investigate the ability of S. gallolyticus HlpA to mediate bacterial adherence to colon tumor cells. Our experiments showed that purified HlpA did bind to both intact bacteria and colon tumor cells. Furthermore, antibody-mediated blockage of HlpA reduced the adhering properties of S. gallolyticus, whereas loading S. gallolyticus cells with purified HlpA had no promoting effect on bacterial adherence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

The strain used in this study was S. gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus UCN34 (entitled herein S. gallolyticus), which was previously isolated from a colon cancer patient with coincidental endocarditis (P. Glaser, unpublished data). This strain relates to S. bovis biotype I, which has the highest association with colon cancer (6). S. gallolyticus cells were cultured at 37°C/5% CO2 in brain heart infusion broth (Difco Laboratories) supplemented with 1% glucose. S. gallolyticus lysates were obtained by mechanical disruption of frozen bacterial cell pellets at 2,000 rpm in liquid N2. Lysed bacteria were dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stored at −20°C. The Escherichia coli strains DH5α (Invitrogen), used for recombinant DNA procedures, and BL21(DE3) (Novagen), used as an overproduction host, were grown aerobically at 37°C in Luria broth. When required, the medium for E. coli was supplemented with 50 μg/ml ampicillin.

Colon adenocarcinoma cell lines and media.

The colon adenocarcinoma cell lines Caco-2, HCT116, and HT-29 (obtained from the American Type Culture Collection) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Lonza) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 20 mM HEPES, 100 nM nonessential amino acids, and 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco). HT-29 and HCT116 cells were subcultured every 3 days and Caco-2 cells every 7 days. Coculture experiments were performed in six-well plates with complete DMEM containing 1% fetal calf serum.

DNA techniques.

Procedures for PCR, DNA purification, restriction, ligation, agarose gel electrophoresis, and calcium chloride transformation of E. coli were carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (29). Enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs and Applied Biosystems. To construct pET11-HlpA-His, first a fragment comprising the complete open reading frame of the hlpA gene of S. gallolyticus was amplified by PCR using the primers HlpA-u (5′-ACGTCATATGGCTAACAAACAAGATTT AATCGC-3′), containing an NdeI cleavage site, and HlpA-r (5′-CGTAGGATCCTTAATGGTGATGGTGATGGTGTTTTACAGCGT CTTTAAGTGCTTTACC-3′), which inserts a hexahistidine (six-His) tag upstream of the hlpA stop codon and contains a BamHI cleavage site. Next, the amplified fragment was cleaved with NdeI and BamHI and ligated into the corresponding sites of pET11a (Novagen).

Protein purification.

To overproduce HlpA-His, 500 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to exponentially growing E. coli BL21(DE3) cells that were first introduced with pET11-HlpA-His. Cells were harvested after 4 h and lysed by three freeze-thaw cycles. Native His-tagged HlpA was purified by nickel affinity chromatography by use of a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid mini spin kit from Qiagen.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

To monitor the affinity of HlpA-His for intact S. gallolyticus cells, bacteria were incubated with purified HlpA-His (∼30 μM) for 1 h at 37°C. Next, bacteria were washed three times with sterile PBS and directly incubated in Tricine sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (30) for 15 min. Bacteria and isolated protein fractions were analyzed by Tricine SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (30). To detect HlpA or HlpA-His, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Amersham) by Western blotting (40). Blots were incubated with monoclonal antihexahistidine antibodies (Qiagen) or highly cross-reactive anti-S. pyogenes HlpA antibodies that were raised against recombinant S. pyogenes histone-like protein and purified as described previously (16). Bound antibodies were visualized with an ECL detection system (Amersham) using anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G horseradish peroxidase conjugates (Jackson ImmunoResearch).

In-cell Western analysis.

To investigate the binding of HlpA-His to intact S. gallolyticus or adenocarcinoma cells, 96-well plates were coated with either adenocarcinoma cells (50,000 cells/well) or bacteria (1 × 109/ml). Briefly, bacteria were cultured to the exponential (optical density at 600 nm of 0.6) or stationary (optical density at 600 nm of 1.0) growth phase and subsequently incubated with purified HlpA (∼30 μM) at 37°C/5% CO2 for 1 h. Next, bacteria were allowed to attach to a poly-lysine-coated 96-well plate at 4°C overnight. To determine the net binding of endogenous and recombinant HlpA, coated bacteria were stripped with trypsin-EDTA (20 U/ml). The HT-29, Caco-2, and HCT116 cells were cultured in 96-well plates for 3 days at 37°C to create a confluent monolayer. Purified HlpA-His (∼30 μM) was dissolved in specified growth medium and allowed to bind to confluent monolayers for 1 h. Excess protein was removed by three washes with PBS. Then, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and left intact to determine the amount of extracellularly adhered HlpA. After fixation, plates were washed with PBS and blocked with Li-COR Odyssey blocking buffer (Li-COR Biosciences). HlpA was detected with a polyclonal HlpA antibody and visualized with Odyssey (Li-COR Biosciences) and a secondary anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 680 (Molecular Probes).

LTA and heparin binding assays.

Streptococcal LTA (1 μg/μl; Sigma) was immobilized on Interaction Discovery Mapping (IDM) affinity beads (Ciphergen Biosystems) by incubation in 100 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5). Beads were washed extensively with PBS after blocking of unoccupied binding sites by 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8. Immobilized LTA or heparin (heparin Sepharose; Pierce) was incubated with soluble bacterial proteins for 1 h in PBS, followed by centrifugation, after which the supernatant (unbound fraction) was collected. Next, LTA or heparin beads were washed three times with PBS, and retained proteins were eluted in 100 mM ammonium acetate (pH 6) containing 0.1% SDS at 95°C for 10 min. Protein profiles of bound and unbound low-molecular-mass proteins were generated by surface-enhanced laser desorption-ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, as described previously (38). Alternatively, eluted proteins were boiled in SDS sample buffer for SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. Protein identification was performed by in-gel tryptic digestion followed by peptide sequencing by tandem mass spectrometry, as described previously (37).

Bacterial adherence assay.

The influence of HlpA on adherence of S. gallolyticus to adenocarcinoma cells (HCT116 and HT-29) was studied with an adherence assay as described previously (3). First, S. gallolyticus cells were treated with recombinant HlpA-His (∼30 μM), HlpA antibodies (1:1,000), or HlpA antibodies preblocked with HlpA-His in PBS. Nontreated S. gallolyticus cells were used to determine normal adherence levels. After pretreatment of the bacteria, the bacteria were added at a multiplicity of infection of 20:1 (bacteria/cells) to subconfluent monolayers, and the infected cells were incubated for 2 h. To determine the number of adhered bacteria, the monolayers were washed three times with PBS and lysed with ice-cold PBS containing 0.025% Triton X-100. Serial dilutions of cell lysates were plated on blood-agar plates and incubated at 37°C/5% CO2 to count the CFU.

RESULTS

HlpA of S. gallolyticus is an anchorless bacterial surface protein with affinity for colon tumor cells.

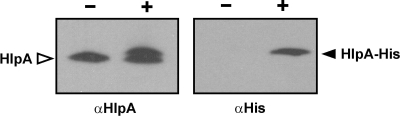

To act as adherence factors, anchorless proteins should have affinity for components of both bacterial and colon tumor cells. To evaluate this for HlpA from S. gallolyticus, the hlpA gene was first cloned in such a way that a hexahistidine extension (His tag) was added to the carboxyl terminus of HlpA. The resulting HlpA-His protein was overproduced and purified from E. coli cells to determine affinity for the surfaces of intact S. gallolyticus cells (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Binding of HlpA to intact bacteria. Western blot analysis of S. gallolyticus cells that were incubated with (+) or without (−) purified HlpA-His. In the left panel, the recombinant and endogenous HlpA molecules were visualized with anti-HlpA (αHlpA) antibodies. The upper band in the “+” lane corresponds to the recombinant HlpA-His molecule that is also detected by the anti-His (αHis) antibody (right panel).

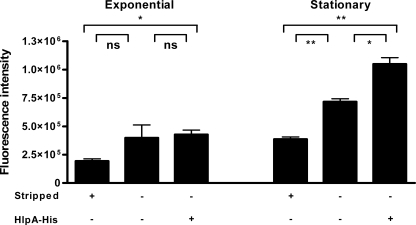

To investigate whether the surface expression of HlpA from S. gallolyticus is also growth phase dependent, S. gallolyticus cells were harvested during the exponential and stationary growth phases and immobilized in microtiter plates for in-cell Western analysis using HlpA antibodies. To reveal the endogenous expression of HlpA at the bacterial surface, bacterial cells were stripped with trypsin-EDTA to remove extracellular proteins. This showed that the endogenous expression of surface HlpA was indeed more abundant during the stationary growth phase (P = 0.0095) than during the exponential phase (not significant) (Fig. 2), but it should be noted that some low level of autolysis could have contributed to the amount of endogenous surface HlpA. Interestingly, the extracellular addition of HlpA-His to intact bacteria showed that the cell wall of S. gallolyticus cells from the stationary growth phase was not saturated with HlpA (P = 0.0331), whereas no additional binding of HlpA-His to exponentially growing cells was observed. These data show that endogenous HlpA is expressed at the cell surface of S. gallolyticus and that this phenomenon seems present most prominently during the stationary growth phase.

FIG. 2.

Affinity of HlpA for S. gallolyticus in exponential and stationary growth phases. In-cell Western analysis of S. gallolyticus bacteria in exponential and stationary growth phases exposed to HlpA-His. Approximately 1 × 109 exponential- or stationary-phase-grown bacteria were coated onto a 96-well plate. Detection of HlpA and HlpA-His was established by rabbit anti-HlpA antibodies and secondary Alexa Fluor 680-labeled anti-rabbit antibody. The bars represent the fluorescence intensities of extracytoplasmic recombinant HlpA-His and endogenous HlpA of bacteria. Note that nonstripped (top row, −) bacteria have, in addition to HlpA-His, endogenous HlpA at their surfaces, whereas trypsin-stripped (top row, +) bacteria have reduced endogenous levels of HlpA on the bacterial cell wall. Exponential- or stationary-phase bacteria were incubated either with (bottom row, +) or without (bottom row, −) HlpA-His. The fluorescence intensity was corrected for background measurement of the incubation medium. Error bars indicate the standard errors from two replicate experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ns, not significant (Student's t test).

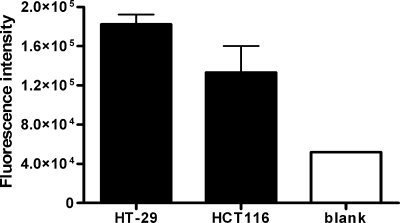

To identify whether HlpA can play a role in S. gallolyticus adherence, the binding of HlpA-His to the adenocarcinoma cell lines HT-29, HCT116, and Caco-2 was quantified by in-cell Western analysis. The fluorescence intensity of HlpA was highest in HT-29 cells and then in HCT116 cells compared to that for the blank measurement (Fig. 3). In contrast, the fluorescence intensity of Caco-2 adenocarcinoma cells after incubation with HlpA-His remained similar to that for the blank measurement, which may reflect the low level of HSPGs in these cells (reference 11 and data not shown). Taken together, these data show that extracellularly added HlpA can bind to the bacterial surface and also has affinity for HT-29 and HCT116 colon tumor cells and thus, in principle, should be able to act as a mediator for bacterial adherence.

FIG. 3.

Binding of HlpA to intact adenocarcinoma cells. In-cell Western analysis of HT-29 and HCT116 colorectal cancer cells incubated with purified HlpA-His from S. gallolyticus. Detection of HlpA-His was established by incubation with rabbit anti-HlpA antibody and with Alexa Fluor 680-labeled secondary anti-rabbit antibody. The bars represent the fluorescence intensities of HlpA-His on adenocarcinoma cells. The fluorescence intensity of HlpA was corrected for the basal fluorescence level (nonspecific fluorescence) of the indicated cell line. The blank measurement was obtained by subtracting the fluorescence intensity of a blank well incubated with DMEM from that of a well incubated with DMEM with HlpA (background measurement). Error bars indicate the standard errors from two replicate experiments.

HlpA from S. gallolyticus is a heparin- and LTA-binding protein.

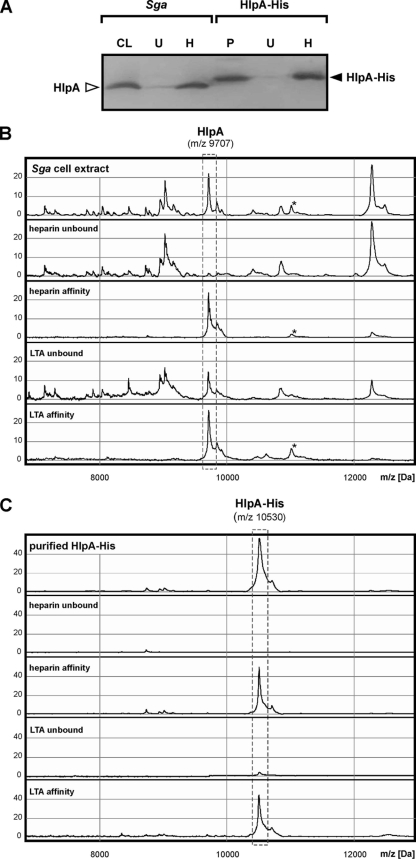

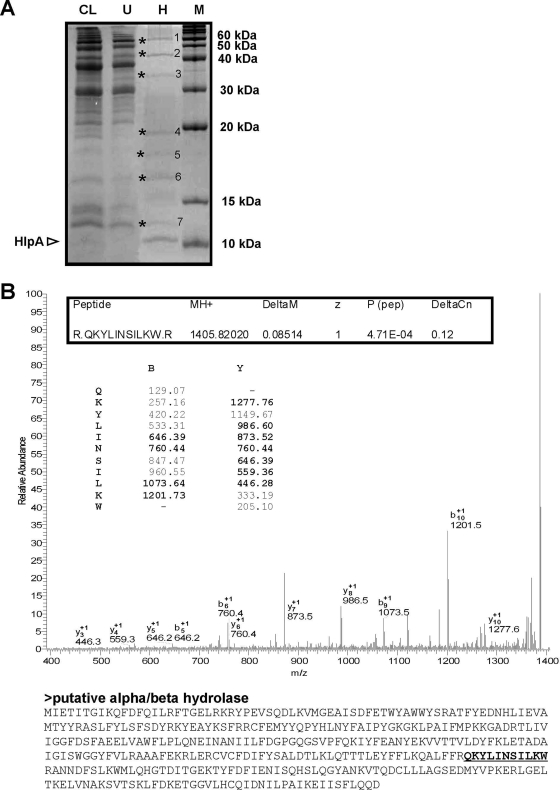

To gain evidence for the components on the colon tumor and bacterial cell surfaces that are responsible for the retention of HlpA, in vitro binding assays were performed. Previous studies showed that HlpA from S. bovis biotype II is a heparin-binding protein (37) and indicated that HSPGs on epithelial cells may have a role in the binding and invasion of these bacteria (12). To confirm heparin affinity of endogenous HlpA from the S. gallolyticus strain used in this study and that of its recombinant analogue HlpA-His, cell lysates and purified HlpA-His were incubated with immobilized heparin. As shown in Fig. 4A, both endogenous and recombinant HlpA(-His) had a high affinity for heparin. Furthermore, mass spectrometry analysis of the low-molecular-mass proteins showed that heparin affinity is selective for HlpA (Fig. 4B and C), which appeared to be the major low-molecular-mass heparin-binding protein of S. gallolyticus. To investigate whether S. gallolyticus contains additional heparin-binding proteins of >15 kDa, S. gallolyticus total cell lysates were incubated with immobilized heparin, after which retained proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. These analyses confirmed that HlpA is one of the major heparin-binding proteins from S. gallolyticus; however, at least seven additional heparin-binding proteins were observed (Fig. 5A), and of these, protein 2 was identified as a putative alpha/beta hydrolase of 44 kDa (Fig. 5B). Nevertheless, these additional proteins were not present or scarcely present in S. gallolyticus cell wall extracts (our unpublished observations). Thus, HlpA appears to be the major surface-exposed heparin-binding protein from S. gallolyticus.

FIG. 4.

Heparin and LTA affinity of HlpA. (A) Western blot analysis of a total S. gallolyticus (Sga) cell lysate (CL) and purified (P) HlpA-His and the respective fractions that remain unbound (U) after incubation with immobilized heparin and that have heparin affinity (H). Blots were decorated with anti-HlpA or anti-six-His antibodies. The positions of endogenous HlpA and recombinant HlpA-His are indicated. (B) Low-molecular-mass protein profiles of a total S. gallolyticus cell extract, the respective proteins that remain unbound after incubation with immobilized heparin or LTA, and the respective proteins that have heparin or LTA affinity. Note that a second (unknown) protein with both heparin and LTA affinity is indicated with an asterisk. (C) Low-molecular-mass spectra of purified HlpA-His from S. gallolyticus, the fraction that remains unbound after incubation with immobilized heparin or LTA, and the proteins that have heparin or LTA affinity. The 9,707- and 10,530-Da peaks, corresponding to, respectively, endogenous HlpA and recombinant HlpA-His, are indicated. The peak intensity is given in arbitrary units.

FIG. 5.

(A) SDS-PAGE analysis of a total S. gallolyticus cell lysate (CL) and the respective proteins that remain unbound (U) after incubation with immobilized heparin or have heparin affinity (H). The position of endogenous HlpA is indicated. Unknown heparin-binding proteins 1 to 7 are indicated with asterisks. M, molecular mass marker. (B) Identification of protein band 2 as a putative alpha/beta hydrolase of S. gallolyticus. Band 2, a putative heparin-binding protein (indicated in panel A), was excised from the gel and digested with trypsin to allow tandem mass spectrometry and peptide mass fingerprinting. The tandem mass spectrometry spectrum of peptide “QKYLINSILKW,” m/z 1,405.82, is shown. The theoretical series of b ions produced from cleavage of the amide bond and y ions produced by cleavage of the amide bond are indicated, with the actual identified ions printed in bold. The theoretical molecular mass of the corresponding putative alpha/beta hydrolase is 43.7 kDa, which is in-line with its mobility by SDS-PAGE (see panel A).

To show LTA affinity of endogenous and recombinant HlpA(-His) from S. gallolyticus, cell lysates and purified HlpA-His were incubated with immobilized LTA and retained proteins were analyzed by mass spectrometry. As shown in Fig. 4B and C, endogenous and recombinant HlpA(-His) both had affinity for LTA. This suggests that HlpA is retained by LTA in the bacterial cell wall and can mediate bacterial adherence by linking HSPGs of epithelial cells to LTA of the bacterial cell wall. Importantly, these analyses also indicated that the native features of HlpA have been preserved in recombinant HlpA-His, which thus can be used as an experimental substitute for endogenous HlpA.

Surface HlpA affects S. gallolyticus adherence to colon tumor cells.

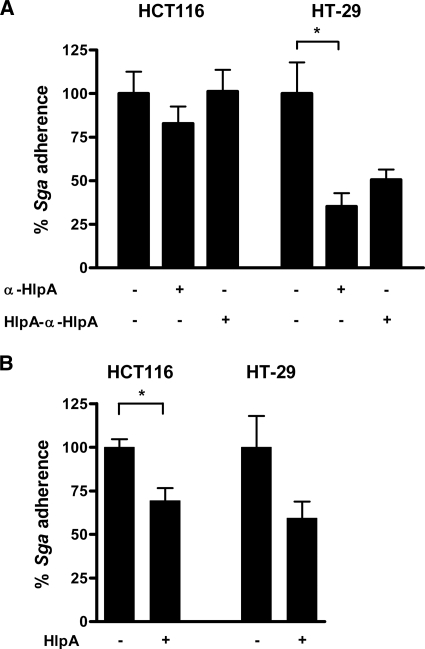

To investigate whether surface HlpA indeed mediates the adherence of S. gallolyticus to colorectal cancer cells, bacterial adherence assays were performed. First, endogenous HlpA on the surface of S. gallolyticus was blocked by the anti-HlpA immunoglobulin G that was also used for in-cell Western analysis (Fig. 2 and 3). As shown in Fig. 6A, this resulted in approximately 20% (not significant) and 60% (P = 0.0158) reduced adherence of S. gallolyticus to HCT116 and HT-29 cells, respectively, compared to the level for untreated S. gallolyticus cells (100% adhesion). The latter inhibition was partially restored (not significant) by antibodies preblocked with HlpA-His that were used to confirm a specific interaction between HlpA and the anti-HlpA antibody.

FIG. 6.

Surface HlpA modulates bacterial adherence. (A) S. gallolyticus cells were incubated with (+) or without (−) anti-HlpA (α-HlpA) antibodies. Antibodies preincubated with HlpA-His (HlpA-α-HlpA) served as a control. Adherence of S. gallolyticus (Sga) to HCT116 and HT-29 cells was monitored by CFU serial dilution counting. The adherence of S. gallolyticus for the specified cell lines was set at 100%. Error bars indicate the standard errors from three replicate experiments. *, P < 0.05 (Student's t test). (B) Adherence of S. gallolyticus cells coated with (+) or without (−) recombinant HlpA-His was monitored by CFU serial dilution counting. The adherence of S. gallolyticus to the specified cell lines was set at 100%. Error bars indicate the standard errors from three replicate experiments. *, P < 0.05 (Student's t test).

To investigate whether additional surface HlpA could further increase bacterial adherence, S. gallolyticus cells were coated with HlpA-His prior to use in an adherence assay. Unexpectedly, adhesion of HlpA-His-coated bacteria did not result in an increase, but decreased the adherence to HT-29 (not significant) and HCT116 (P = 0.0242) cells to about 65% of the level for untreated S. gallolyticus cells (Fig. 6B). This implies that an excess of surface HlpA has an inhibitory effect.

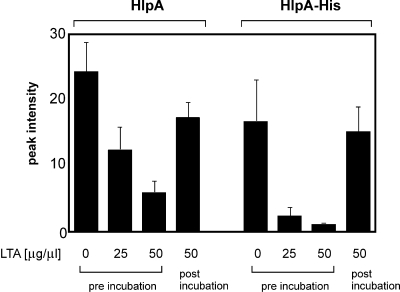

Heparin and LTA compete for the same binding sites in HlpA.

The above-described apparent contradictory data suggest that HlpA adds to bacterial adherence but point to a more complex process than simply linking HSPGs and LTA. One of the influencing factors could be that HSPGs and LTA, both strong negative structures, compete for the same positively charged binding sites in HlpA (28, 35). Therefore, the interference of LTA in heparin binding of HlpA was investigated by mass spectrometry. As shown in Fig. 7, preincubation of HlpA with soluble LTA inhibited the binding of both HlpA and HlpA-His to immobilized heparin in a concentration-dependent manner. In contrast, incubation with LTA after binding to immobilized heparin had no significant inhibitory effect on the binding of HlpA and HlpA-His to heparin. The fact that these effects were more pronounced with HlpA-His is possibly due to the scavenging of LTA by other S. gallolyticus proteins with affinity for LTA (and possibly heparin) in the total cell extracts (Fig. 4B). Thus, these data suggest that HlpA cannot efficiently bind to both HSPG and LTA simultaneously.

FIG. 7.

LTA inhibition of heparin binding of HlpA. Low-molecular-mass profiles of heparin-binding proteins from a total S. gallolyticus cell extract or that of purified HlpA-His were generated by mass spectrometry. Bars represent the peak intensities of HlpA (m/z 9,707) and HlpA-His (m/z 10,530) that were retained by immobilized heparin after preincubation or postincubation with 25 or 50 μg/μl soluble LTA. Error bars indicate the standard errors from three replicate experiments.

DISCUSSION

HSPGs are proposed to give bacteria the opportunity to adhere to and invade the epithelium, but whether bacteria can use these eukaryotic structures is dependent on bacterial heparin-binding proteins at the bacterial surface. Several studies have stated that histone-like proteins are detected in the culture supernatant or at the bacterial cell surface of Helicobacter pylori, S. pyogenes, and Streptococcus intermedius (19, 21, 33). Furthermore, it has been shown previously that HlpA from S. pyogenes can be complexed to LTA (33, 35). Therefore, we hypothesized that the histone-like protein HlpA of S. gallolyticus was a likely candidate to mediate adherence via these structures. Our studies clearly showed that endogenous and recombinant HlpA(-His) have affinity for both heparin and LTA. Our data demonstrate that endogenous HlpA is preferentially expressed at the bacterial surface in the stationary growth phase, which is in line with the study of Katsube et al., who reported that the histone-like protein MDP1 of Mycobacterium smegmatis accumulates in cell wall fractions in the stationary phase (18). Furthermore, our findings correlate with previous studies reporting the release of HlpA during the stationary growth phase (22, 35). In the exponential phase, HlpA is required intracellularly to execute its physiological role in nucleoid formation (1), but even though endogenous HlpA is maintained intracellularly, recombinant HlpA-His was not able to bind to the bacterial surface. Thus, HlpA relocation at the bacterial surface is growth phase dependent in vitro, which could mirror the in vivo bacterial steady-state situation in, for instance, the gastrointestinal tract.

A previous study by Henry-Stanley et al. showed that the colon adenocarcinoma cell line HT-29 expresses HSPGs and more specifically the heparan sulfate syndecan-1, whereas Caco-2 cells have only low levels of these proteoglycans (11). Furthermore, Stinson et al. reported that bacterial HlpA of S. pyogenes binds to heparan sulfate in the extracellular matrix of human epithelial Hep-2 cells (35). We observed that recombinant HlpA-His could bind to HT-29 and HCT116 adenocarcinoma cells but not to Caco-2 cells, which coincides with the amount of HSPGs and syndecan-1 and with the previously reported conclusion that S. bovis may use heparan sulfates to invade eukaryotic cells (12). Furthermore, we found that S. gallolyticus adherence to both HCT116 and HT-29 cells was reduced by anti-HlpA antibodies, although the effects seen in the independent experiments did not reach statistical significance. Nevertheless, the same trend was observed for both cell lines, which is in line with the fact that heparin inhibited S. bovis internalization to a similar extent in HT-29 cells (12). Unexpectedly, however, when S. gallolyticus was coated with additional recombinant HlpA-His, adherence was decreased. This implies that an excess of surface HlpA blocks adherence. A possible explanation for these apparent contradictory effects may be given by the fact that LTA competes with heparin for the binding of endogenous and recombinant HlpA, indicating that HSPGs and LTA use the same binding site(s) in this molecule (Fig. 7). The E. coli DNA binding protein HU, which is homologous to HlpA, has been studied extensively in its interaction with DNA. Homotypic dimers of E. coli HU interact with DNA via its binding arms, which resemble the amino acid sequence of S. gallolyticus HlpA (27). These binding arms display an amino acid sequence that contains a typical positively charged heparin-binding site, as proposed by Cardin and Weintraub (4, 9), which interacts with negatively charged sulfate or carboxyl groups on heparin chains but may also interact with the negatively charged LTA (42).

Thus, although we have shown that HlpA is a major heparin-binding protein at the bacterial surface, the exact contribution of HlpA and HSPGs in the adherence of S. gallolyticus to colon tumor cells is not yet fully resolved. In this respect, it was interesting to note that Sillanpaa and coworkers showed that S. gallolyticus can bind to several eukaryotic extracellular matrix proteins (34). Others demonstrated that LTA itself is important for bacterial adherence and invasion (7, 17, 32); this was confirmed for S. gallolyticus in a study by Von Hunolstein et al., who showed that adherence to buccal epithelial cells was affected by anti-LTA antibodies and epithelial LTA treatment (41). In view of our current observations, increasing the amount of HlpA at the bacterial surface could therefore decrease the amount of interacting LTA molecules, when attachment of our clinical isolate is mainly LTA driven. Furthermore, our results could imply that excess surface HlpA hinders the interaction of other important adhesion molecules on S. gallolyticus.

For opportunistic pathogens, such as S. gallolyticus, a temporal regulation of interactions with host cells may be of critical importance. Although a firm connection with host epithelial (tumor) cells is key during the first phase of infection, an interaction with tissue macrophages that form the second line of defense against invading pathogens should be avoided. In this respect, surface HlpA may for instance shield LTA from interacting with Toll-like receptors on macrophages (8). Our current data show that surface HlpA may be one of the modulators of these bacterial interactions with host cells. However, HlpA from Streptococcus mitis by itself has been shown to activate an immune response in murine macrophages in vitro, which is mediated by the induction of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (43). Similarly, Liu et al. have shown that HlpA of S. intermedius can induce cytokine production in human macrophages (22). However, none of these studies has determined the net effect of the HlpA-mediated shielding of LTA from intact bacteria on the interaction with, and activation of, macrophages; this will be a subject of our future investigations.

Taken together, our current data underscore that bacterial adherence is a highly balanced process involving multiple interactions on the host-pathogen interface. Importantly, this study presents the first evidence that surface HlpA may provide opportunistic pathogens, such as S. gallolyticus, with the ability to adjust their host-pathogen interactions during different stages of infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Coby Laarakkers, Rian Roelofs, Peter Burghout, Hester Bootsma, and our other colleagues from the Department of Clinical Chemistry and the Laboratory of Pediatric Infectious Diseases and Rene te Morsche and Hennie Roelofs from the Department of Gastroenterology for useful discussions and/or technical assistance.

A.B. and R.M.J.S. were supported by the Dutch Cancer Association (KWF; KUN 2006-3591).

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 September 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali Azam, T., A. Iwata, A. Nishimura, S. Ueda, and A. Ishihama. 1999. Growth phase-dependent variation in protein composition of the Escherichia coli nucleoid. J. Bacteriol. 181:6361-6370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boël, G., H. Jin, and V. Pancholi. 2005. Inhibition of cell surface export of group A streptococcal anchorless surface dehydrogenase affects bacterial adherence and antiphagocytic properties. Infect. Immun. 73:6237-6248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bootsma, H. J., M. Egmont-Petersen, and P. W. Hermans. 2007. Analysis of the in vitro transcriptional response of human pharyngeal epithelial cells to adherent Streptococcus pneumoniae: evidence for a distinct response to encapsulated strains. Infect. Immun. 75:5489-5499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardin, A. D., and H. J. Weintraub. 1989. Molecular modeling of protein-glycosaminoglycan interactions. Arteriosclerosis 9:21-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhatwal, G. S. 2002. Anchorless adhesins and invasins of Gram-positive bacteria: a new class of virulence factors. Trends Microbiol. 10:205-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corredoira, J., M. P. Alonso, A. Coira, E. Casariego, C. Arias, D. Alonso, J. Pita, A. Rodriguez, M. J. Lopez, and J. Varela. 2008. Characteristics of Streptococcus bovis endocarditis and its differences with Streptococcus viridans endocarditis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27:285-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtney, H. S., C. von Hunolstein, J. B. Dale, M. S. Bronze, E. H. Beachey, and D. L. Hasty. 1992. Lipoteichoic acid and M protein: dual adhesins of group A streptococci. Microb. Pathog. 12:199-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Draing, C., S. Sigel, S. Deininger, S. Traub, R. Munke, C. Mayer, L. Hareng, T. Hartung, S. von Aulock, and C. Hermann. 2008. Cytokine induction by Gram-positive bacteria. Immunobiology 213:285-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gandhi, N. S., and R. L. Mancera. 2008. The structure of glycosaminoglycans and their interactions with proteins. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 72:455-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guarner, F., and J. R. Malagelada. 2003. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet 361:512-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henry-Stanley, M. J., D. J. Hess, E. A. Erickson, R. M. Garni, and C. L. Wells. 2003. Role of heparan sulfate in interactions of Listeria monocytogenes with enterocytes. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 192:107-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry-Stanley, M. J., D. J. Hess, S. L. Erlandsen, and C. L. Wells. 2005. Ability of the heparan sulfate proteoglycan syndecan-1 to participate in bacterial translocation across the intestinal epithelial barrier. Shock 24:571-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herrero, I. A., M. S. Rouse, K. E. Piper, S. A. Alyaseen, J. M. Steckelberg, and R. Patel. 2002. Reevaluation of Streptococcus bovis endocarditis cases from 1975 to 1985 by 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3848-3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hess, D. J., M. J. Henry-Stanley, S. L. Erlandsen, and C. L. Wells. 2006. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate Staphylococcus aureus interactions with intestinal epithelium. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 195:133-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoen, B., C. Chirouze, C. H. Cabell, C. Selton-Suty, F. Duchene, L. Olaison, J. M. Miro, G. Habib, E. Abrutyn, S. Eykyn, Y. Bernard, F. Marco, and G. R. Corey. 2005. Emergence of endocarditis due to group D streptococci: findings derived from the merged database of the International Collaboration on Endocarditis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 24:12-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin, H., and V. Pancholi. 2006. Identification and biochemical characterization of a eukaryotic-type serine/threonine kinase and its cognate phosphatase in Streptococcus pyogenes: their biological functions and substrate identification. J. Mol. Biol. 357:1351-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapczynski, D. R., R. J. Meinersmann, and M. D. Lee. 2000. Adherence of Lactobacillus to intestinal 407 cells in culture correlates with fibronectin binding. Curr. Microbiol. 41:136-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katsube, T., S. Matsumoto, M. Takatsuka, M. Okuyama, Y. Ozeki, M. Naito, Y. Nishiuchi, N. Fujiwara, M. Yoshimura, T. Tsuboi, M. Torii, N. Oshitani, T. Arakawa, and K. Kobayashi. 2007. Control of cell wall assembly by a histone-like protein in mycobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 189:8241-8249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim, N., D. L. Weeks, J. M. Shin, D. R. Scott, M. K. Young, and G. Sachs. 2002. Proteins released by Helicobacter pylori in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 184:6155-6162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein, R. S., R. A. Recco, M. T. Catalano, S. C. Edberg, J. I. Casey, and N. H. Steigbigel. 1977. Association of Streptococcus bovis with carcinoma of the colon. N. Engl. J. Med. 297:800-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lei, B., S. Mackie, S. Lukomski, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Identification and immunogenicity of group A streptococcus culture supernatant proteins. Infect. Immun. 68:6807-6818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, D., H. Yumoto, K. Hirota, K. Murakami, K. Takahashi, K. Hirao, T. Matsuo, K. Ohkura, H. Nagamune, and Y. Miyake. 2008. Histone-like DNA binding protein of Streptococcus intermedius induces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in human monocytes via activation of ERK1/2 and JNK pathways. Cell. Microbiol. 10:262-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pancholi, V., and G. S. Chhatwal. 2003. Housekeeping enzymes as virulence factors for pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 293:391-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pancholi, V., and V. A. Fischetti. 1998. Alpha-enolase, a novel strong plasmin(ogen) binding protein on the surface of pathogenic streptococci. J. Biol. Chem. 273:14503-14515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pancholi, V., and V. A. Fischetti. 1992. A major surface protein on group A streptococci is a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase with multiple binding activity. J. Exp. Med. 176:415-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pancholi, V., P. Fontan, and H. Jin. 2003. Plasminogen-mediated group A streptococcal adherence to and pericellular invasion of human pharyngeal cells. Microb. Pathog. 35:293-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramstein, J., N. Hervouet, F. Coste, C. Zelwer, J. Oberto, and B. Castaing. 2003. Evidence of a thermal unfolding dimeric intermediate for the Escherichia coli histone-like HU proteins: thermodynamics and structure. J. Mol. Biol. 331:101-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rostand, K. S., and J. D. Esko. 1997. Microbial adherence to and invasion through proteoglycans. Infect. Immun. 65:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed., vol. 1. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 30.Schagger, H. 2006. Tricine-SDS-PAGE. Nat. Protoc. 1:16-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlegel, L., F. Grimont, M. D. Collins, B. Regnault, P. A. Grimont, and A. Bouvet. 2000. Streptococcus infantarius sp. nov., Streptococcus infantarius subsp. infantarius subsp. nov. and Streptococcus infantarius subsp. coli subsp. nov., isolated from humans and food. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:1425-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sela, S., M. J. Marouni, R. Perry, and A. Barzilai. 2000. Effect of lipoteichoic acid on the uptake of Streptococcus pyogenes by HEp-2 cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 193:187-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Severin, A., E. Nickbarg, J. Wooters, S. A. Quazi, Y. V. Matsuka, E. Murphy, I. K. Moutsatsos, R. J. Zagursky, and S. B. Olmsted. 2007. Proteomic analysis and identification of Streptococcus pyogenes surface-associated proteins. J. Bacteriol. 189:1514-1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sillanpaa, J., S. R. Nallapareddy, K. V. Singh, M. J. Ferraro, and B. E. Murray. 2008. Adherence characteristics of endocarditis-derived Streptococcus gallolyticus ssp. gallolyticus (Streptococcus bovis biotype I) isolates to host extracellular matrix proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 289:104-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stinson, M. W., R. McLaughlin, S. H. Choi, Z. E. Juarez, and J. Barnard. 1998. Streptococcal histone-like protein: primary structure of hlpA and protein binding to lipoteichoic acid and epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 66:259-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tjalsma, H., L. Lambooy, P. W. Hermans, and D. W. Swinkels. 2008. Shedding & shaving: disclosure of proteomic expressions on a bacterial face. Proteomics 8:1415-1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tjalsma, H., W. Pluk, L. P. van den Heuvel, W. H. Peters, R. Roelofs, and D. W. Swinkels. 2006. Proteomic inventory of “anchorless” proteins on the colon adenocarcinoma cell surface. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1764:1607-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tjalsma, H., M. Scholler-Guinard, E. Lasonder, T. J. Ruers, H. L. Willems, and D. W. Swinkels. 2006. Profiling the humoral immune response in colon cancer patients: diagnostic antigens from Streptococcus bovis. Int. J. Cancer 119:2127-2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tonnaer, E. L., T. G. Hafmans, T. H. Van Kuppevelt, E. A. Sanders, P. E. Verweij, and J. H. Curfs. 2006. Involvement of glycosaminoglycans in the attachment of pneumococci to nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Microbes Infect. 8:316-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Von Hunolstein, C., M. L. Ricci, and G. Orefici. 1993. Adherence of glucan-positive and glucan-negative strains of Streptococcus bovis to human epithelial cells. J. Med. Microbiol. 39:53-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winters, B. D., N. Ramasubbu, and M. W. Stinson. 1993. Isolation and characterization of a Streptococcus pyogenes protein that binds to basal laminae of human cardiac muscle. Infect. Immun. 61:3259-3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang, L., T. A. Ignatowski, R. N. Spengler, B. Noble, and M. W. Stinson. 1999. Streptococcal histone induces murine macrophages to produce interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect. Immun. 67:6473-6477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.zur Hausen, H. 2006. Streptococcus bovis: causal or incidental involvement in cancer of the colon? Int. J. Cancer 119:xi-xii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]