Abstract

The pathogenesis of an infection of the male genitourinary tract of mice with a human serovar of Chlamydia trachomatis has not been characterized. To establish a new model, we inoculated C3H/HeN (H-2k) mice in the meatus urethra with C. trachomatis serovar D. To determine the 50% infectious dose (ID50), male mice were inoculated with doses ranging from 102 to 106 inclusion-forming units (IFU). The mice were euthanized 10 days post infection (p.i.), and the urethra, bladder, epididimydes, and testes were cultured for Chlamydia. Positive cultures were obtained from the urethra, urinary bladder, and epididimydes, and the ID50 was determined to be 5 × 104 IFU/mouse. Subsequently, to characterize the course of the infection, wild-type (WT) and C3H animals with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID animals) were inoculated with 106 IFU/mouse (20 times the ID50). In the WT mice, the infection peaked in the second week, and by 42 days p.i., it was cleared. In contrast, most of the SCID mice continued to have positive cultures at 60 days p.i. C. trachomatis-specific antibodies were first detected in WT animals' sera at 21 days p.i. and increased until 42 days p.i. The immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) titers were 32-fold higher than those of IgG1, indicative of a Th1-biased immune response. A lymphoproliferative assay using splenocytes showed a significant cell-mediated immune response in the WT mice. As expected, no humoral or cell-mediated immune responses were observed in the SCID animals. In conclusion, inoculation of WT male mice in the meatus urethra with a human serovar of C. trachomatis resulted in a limited infection mainly localized to the lower genitourinary tract. On the other hand, SCID animals could not clear the infection, suggesting that in male mice, the adaptive immune response is necessary to control an infection with a C. trachomatis human serovar.

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common sexually transmitted bacterial pathogen in the Western world (1, 9, 34, 36). The organism can produce a wide variety of infections that may remain asymptomatic or that can result in long-term sequelae (18, 38, 40). Both males and females are affected, and the highest prevalence of infection is found in young sexually active individuals (3, 15, 18, 34, 36). Chlamydial infections not only represent a significant health and economic burden, they also play a role in increasing susceptibility to and transmission of other sexually transmitted pathogens, including human immunodeficiency virus and human papillomavirus (2, 29). Thus, in order to implement preventive and therapeutic measures, the pathogeneses of these infections must be understood.

Recently, an increase in the incidence of male urethritis in several countries has been noted (14, 16, 36). In the United States, it is estimated that almost 2 million cases of symptomatic acute urethritis occur in males, 50% of which are due to C. trachomatis (3, 36). While 50 to 70% of the infections do not produce symptoms, in some males, severe complications can occur (3, 5, 8, 15, 21, 30, 38). For example, approximately 50,000 cases of epididymitis occur yearly in the United States due to C. trachomatis (3, 27). Although rare, abscess formation and infarction of the testicle can also occur (3). Whether a C. trachomatis infection can lead to male infertility is still a matter of debate (3, 5, 8, 10). C. trachomatis may also have a role in Reiter's syndrome, sexually acquired reactive arthritis, proctitis, prostatitis, and granulomatous bowel disease (3, 5, 15, 34, 36, 38).

Little is known about the pathogenesis of chlamydial infections in males. This is due, at least in part, to the lack of an experimental model that mimics the natural infection. We recently described a new male murine model using Chlamydia muridarum (previously known as C. trachomatis mouse pneumonitis [MoPn] biovar [23, 25]). In female mice, this organism causes a more severe disease than the C. trachomatis human serovars (6, 11, 20). Therefore, to gain a better understanding of the immunopathogeneses of these infections, we decided to establish a male model using a human C. trachomatis serovar and the natural route of entry. To implement this new model, we chose to work with C3H/HeN (H-2k) mice. The female animals of this strain have been found to be highly susceptible to infection with C. trachomatis (6). To assess the role of the innate and adaptive immune responses in controlling the infection, we also inoculated animals that had severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID animals). Here, we report the results of infecting male wild-type (WT) and SCID C3H mice in the meatus urethra with the human C. trachomatis serovar D.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Stocks of C. trachomatis serovar D.

C. trachomatis serovar D (strain UW-3/Cx) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and was grown in HeLa-229 cells using Eagle's minimal essential medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum and cycloheximide (1 μg/ml) (28). Elementary bodies (EB) were purified using Hypaque-76 (Nycomed Inc., Princeton, NJ) and stored at −70°C in SPG (0.2 M sucrose, 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, and 5 mM glutamic acid) as described by Caldwell et al. (4).

Infection of mice.

Seven- to 8-week-old male WT C3H/HeNHsd and SCID C3H.C-Prkdcscid lcrSmnHsd (H-2k) mice (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were housed in isolation cubicles at a constant temperature of 24°C with a cycle of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness and were fed chow ad libitum. Following anesthesia, the animals were infected by placing the inoculum on the meatus urethra as previously described (25). To determine the 50% infectious dose (ID50), groups of WT mice were inoculated with doses ranging from 1 × 102 to 1 × 106 inclusion-forming units (IFU) of C. trachomatis serovar D in 2 μl of SPG, and a control group was sham infected with 2 μl of mock-infected HeLa-229 cell extracts. The mice were euthanized 10 days postinfection (p.i.).

To assess the course of the infection, WT and SCID mice were infected with 106 IFU (20 times the ID50), and the animals were euthanized 10, 21, 28, 42, and 60 days p.i. (25). The urethra, urinary bladder, epididymides, and testes were collected, placed in 2 ml of SPG, and homogenized using a Stomacher Lab-Blender 80 (Tekmar Co., Cincinnati, OH). Duplicates of 10-fold dilutions were inoculated onto McCoy cells grown in 48-well tissue culture plates by centrifugation (1,000 × g; 1 h at 24°C). Each well was inoculated with 100 μl of the homogenate. Following inoculation, fresh medium containing cycloheximide (1 μg/ml) was added. The culture plates were incubated for 40 h at 37°C, the medium was discarded, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and fixed with methanol, and the chlamydial inclusions were stained with the Chlamydia monoclonal antibody (E4) developed in our laboratory (28). The limit of detection was 10 IFU per organ. The animal protocols were approved by the University of California, Irvine, Animal Care and Use Committee.

Immunoassays.

Blood was collected at regular intervals by periorbital puncture and terminally from the heart. The serum Chlamydia titer was determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for each individual mouse (24, 25). In brief, 96-well plates were coated with 100 μl of C. trachomatis serovar D in phosphate-buffered saline at a concentration of 10 μg of protein/ml. Mouse serum (100 μl) was added in triplicate to wells in twofold serial dilutions. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the serum was discarded and the wells were washed. The plates were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin M (IgM), IgA, IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, AL). Binding was measured in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader (Labsystem Multiscan, Helsinki, Finland) using 2′-2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic) acid as the substrate. Sera collected from mice before infection were used as negative controls.

Western blot analyses were performed using purified C. trachomatis serovar D EB run on Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide minigels (10% acrylamide, 0.3% [wt/vol] bis-acrylamide) (35). Following transfer to nitrocellulose membranes, the nonspecific sites were blocked with BLOTTO (bovine lacto transfer technique optimizer; 5% [wt/vol] nonfat dry milk, 2 mM CaCl2, and 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0). Pooled serum samples from each group were diluted 1:100 and incubated overnight at 4°C. Antibody binding was detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse pan-Ig antibody and developed with 0.01% hydrogen peroxide and 4-chloro-1-naphthol (24).

A T-cell lymphoproliferative assay was performed using splenocytes (25). The spleens of two mice from each group were teased and enriched for T cells by passage over a nylon wool column. Using a fluorescence-labeled monoclonal antibody to CD3+ (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY), more than 90% of the suspension was found to be T cells. T-cell-enriched cells were counted, and 105 cells/well were aliquoted into a 96-well plate. Antigen-presenting cells were prepared by irradiating the splenocytes with 3,300 rads of 137Cs. UV-inactivated C. trachomatis serovar D was added at a concentration of 50 EB to 1 antigen-presenting cell. Medium alone was used as a negative control, and concanavalin A (5 μg/ml) was added as a positive control. Cell proliferation was measured following the addition of 1 μCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine per well. The uptake of the [3H]thymidine was determined in triplicate cultures after 18 h of incubation.

Histopathology.

Mice infected with 106 IFU were euthanized at 1, 3, 5, 10, 21, 28, 42, and 60 h p.i.; their genitourinary tracts were removed, fixed in buffered formaldehyde, and processed, and the tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and with antibodies to C. trachomatis (25).

Statistics.

A two-tailed unpaired Student's t test and Man-Whitney U test were used to determine the significance of differences between the groups, using the Statview software program on a Macintosh computer (Apple, Cupertino, CA). Differences were considered significant at P values of <0.05.

RESULTS

Determination of the ID50 for C. trachomatis serovar D.

To determine the ID50, groups of 7- to 8-week-old WT C3H/HeN male mice were inoculated in the meatus urethra with doses of C. trachomatis serovar D ranging from 102 to 106 IFU per animal. A control group of mice was sham infected with HeLa-229 cells. The animals were euthanized at 10 days p.i., and the penis, urinary bladder, epididymides, and testes were cultured for C. trachomatis. The results of the dose-response are shown in Table 1. One mouse from each group inoculated with 102 and 103 IFU had a positive culture from at least one of the four organs. Thirty-three percent (two of six) of the mice inoculated with 104 IFU had a positive culture from at least one of the organs, while 83% (five of six) of the mice inoculated with 105 IFU had a positive culture. Of the animals inoculated with 106 IFU, 94% (15/16) had positive cultures. Cultures from the urinary bladder were positive in 67% of the animals inoculated with 105 IFU and in 50% of the mice infected with 106 IFU. The epididymides from one mouse inoculated with 105 IFU and from four mice infected with 106 IFU were positive. All cultures from the testes were negative. Using the Reed-Muench (33) formula, the ID50 for the WT C3H/HeN male mice was determined to be 5 × 104 IFU. From the sham-infected mice, all cultures were negative.

TABLE 1.

Culture results at day 10 p.i. for male C3H/HeN mice infected in the meatus urethra with C. trachomatis serovar D

| C. trachomatis serovar D dose (no. of IFU/mouse) | No. of mice with positive cultures/total no. of mice (% positive for at least one organ) | Urethra |

Bladder |

Epididymides |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Positive | No. of IFUa ± 1 SE | % Positive | No. of IFU ± 1 SE | % Positive | No. of IFU ± 1 SE | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | <10b | 0 | <10 | 0 | <10 |

| 102 | 1/6 (17) | 17 | 6,201 ± 6,201 | 0 | <10 | 0 | <10 |

| 103 | 1/6 (17) | 17 | 20,670 ± 20,670 | 0 | <10 | 0 | <10 |

| 104 | 2/6 (33) | 33 | 3,709 ± 2,498 | 17 | 3 ± 3 | 0 | <10 |

| 105 | 5/6 (83) | 83 | 189,207 ± 132,361 | 67 | 40 ± 21 | 17 | 67 ± 67 |

| 106 | 15/16 (94) | 94 | 102,570 ± 61,647 | 50 | 50 ± 24 | 25 | 5 ± 3 |

Mean number of IFU recovered per organ ± 1 SE.

Limit of detection per organ, 10 IFU.

Assessment of the course of infection.

The course of infection was established by infecting WT and SCID-C3H mice with 106 C. trachomatis IFU, a dose corresponding to 20 times the ID50 for the WT animals. The mice were euthanized, and the organs were harvested over a 9-week period. The results of the organ cultures are shown in Table 2. At day 10, the urethral cultures in 80% (8/10) of the WT mice and in 100% (10/10) of the SCID animals were positive. Over half of the WT and 80% of the SCID mice had positive cultures from the urinary bladder on day 10. Ten of the WT and 20% of the SCID mice had positive cultures of the epididymides. By day 21 p.i., 70% (7/10) of the WT and 100% (5/5) of the SCID animals had positive cultures. Only 30% of the WT mice had positive cultures by day 28 p.i., while 100% of the SCID animals had positive cultures. By day 42 p.i., all the WT mice had negative cultures from all the organs, while 83% (5/6) of the SCID mice had positive cultures from the urethra. The bladder and the epididymides were positive in 33% of the SCID mice by day 42 p.i., while cultures from the WT mice were all negative. All the WT mice had negative cultures at 49 and 60 days p.i. In contrast, 83% (5/6) and 86% (6/7), respectively, of the SCID mice had positive cultures on the same days. Of the SCID mice, 86% (6/7) had positive urethral cultures, 29% (2/7) had positive bladder cultures, and 14% (1/7) had positive cultures from the epididymides at 60 days p.i.

TABLE 2.

Culture results for C3H/HeN and C3H-SCID mice infected in the meatus urethra with 106 IFU of C. trachomatis serovar D

| No. of days p.i. | Mouse type | No. of mice with positive cultures/total no. mice (% positive for at least one organ) | Urethra |

Bladder |

Epididymides |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Positive | No. of IFUa ± 1 SE | % Positive | No. of IFU ± 1 SE | % Positive | No. of IFU ± 1 SE | |||

| 10 | C3H/HeN | 8/10 (80) | 80 | 49,335 ± 19,386c | 60 | 155 ± 122 | 10 | 6 ± 6 |

| C3H-SCID | 10/10 (100) | 100 | 127,056 ± 23,395 | 80 | 122 ± 46 | 20 | 157 ± 148 | |

| 21 | C3H/HeN | 7/10 (70) | 70 | 2,618 ± 1,701 | 0 | <10b | 0 | <10 |

| C3H-SCID | 5/5 (100) | 60 | 15,198 ± 10,851 | 0 | <10 | 0 | <10 | |

| 28 | C3H/HeN | 3/10 (30) | 30 | 94 ± 79c | 0 | <10 | 0 | <10 |

| C3H-SCID | 5/5 (100) | 100 | 38,607 ± 16,284 | 40 | 24 ± 16 | 20 | 8 ± 8 | |

| 42 | C3H/HeN | 0/10 (0) | 0 | <10c | 0 | <10 | 0 | <10 |

| C3H-SCID | 5/6 (83) | 83 | 2,588 ± 1,090 | 33 | 27 ± 20 | 33 | 7 ± 4 | |

| 49 | C3H/HeN | 0/8 (0) | 0 | <10c | 0 | <10 | 0 | <10 |

| C3H-SCID | 5/6 (83) | 83 | 11,948 ± 8,500 | 20 | 964 ± 20 | 0 | <10 | |

| 60 | C3H/HeN | 0/9 (0) | 0 | <10c | 0 | <10 | 0 | <10 |

| C3H-SCID | 6/7 (86) | 86 | 2,585 ± 1,237 | 29 | 29 ± 20 | 14 | 448 ± 448 | |

Mean number of IFU recovered per organ ± 1 SE.

Limit of detection per organ, 10 IFU.

P < 0.05 by the Mann-Whitney U test compared to the C3H-SCID mice.

For the WT mice, the highest yield of C. trachomatis was obtained from the urethra at 10 days p.i. Subsequently, the number of IFU recovered declined, and by 42 days p.i., all of the mice were negative. In the case of SCID mice, the highest yield of IFU from the urethra was also observed at 10 days p.i. However, significant numbers of IFU were recovered from the urethra, bladder, and epididymides of the SCID mice until the end of the experiment at 60 days p.i.

Characterization of the immune response.

C. trachomatis serovar D-specific IgM antibodies were negative in the WT mice at 10 days p.i., were first detected at 21 days p.i., and peaked by 28 days p.i., with a median titer of 200 (data not shown). IgG antibodies were first detected at 21 days p.i., progressively increased, and reached a peak of 19,200 at 42 days p.i. (Table 3). The titers of IgG2a, determined at 42 days p.i., were 25,600, and those of IgG1 were 800. IgA antibody titers slowly increased and peaked with a titer of 500. In the SCID and sham-infected animals, no Chlamydia-specific antibodies were detected.

TABLE 3.

Immune responses at day 42 p.i. in male C3H/HeN and C3H-SCID mice infected with C. trachomatis serovar D

| Mouse type | Group | Anti-C. trachomatis serovar D median enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay titer ± 1 SE |

T-cell proliferative responsea (103 cpm ± 1 SE) to: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgG1 | IgG2a | IgG2b | IgG3 | IgA | EBb | ConAc | Medium | ||

| C3H/HeN | Infected | 19,200 ± 9,715d | 800 ± 677d | 25,600 ± 8,744d | 4,800 ± 1,351d | 1,600 ± 514d | 500 ± 308d | 10.7 ± 0.6e | 21.7 ± 3.3 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| C3H/HeN | Sham infected | <100f | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 25.2 ± 1.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| C3H-SCID | Infected | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 0.1 ± 0.1 |

| C3H-SCID | Sham infected | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

Responses measured using splenocytes.

UV-inactivated C. trachomatis serovar D was added at a concentration of 50 EB to 1 antigen-presenting cell.

Concanavalin A (ConA) was added at a concentration of 5 μg per ml.

P < 0.05 by the Mann-Whitney U test compared to the sham-infected group.

P < 0.05 by Student's t test compared to the sham-infected group.

Limit of detection, a titer of <100.

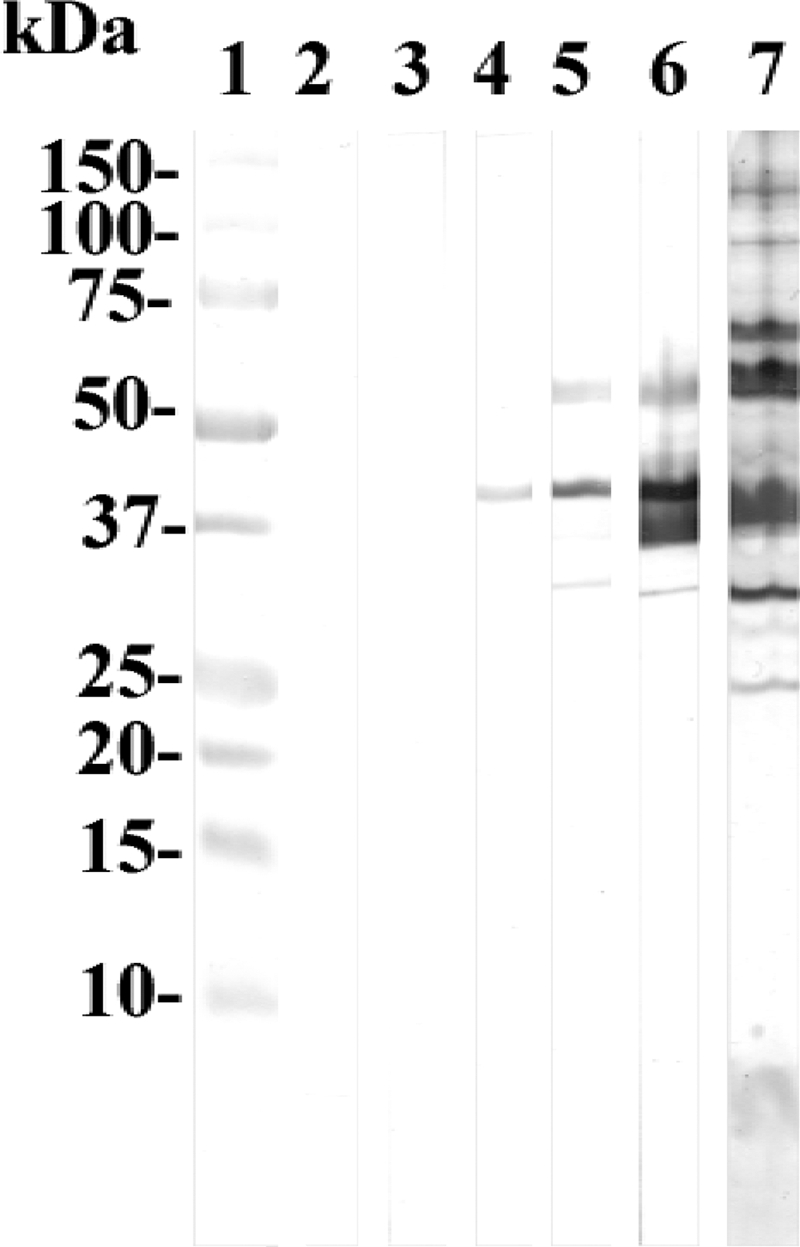

Figure 1 shows the results of the Western blot assays performed with preinfection serum and serum samples collected from the WT mice at 10, 21, 28, and 42 days p.i. The first antibodies, detected at 21 days p.i., bound to the C. trachomatis major outer membrane protein. At 28 days p.i., antibodies to the 60-kDa cysteine-rich protein (Crp), the 60-kDa heat shock protein (Hsp), and the 50- and 28-kDa proteins were also detected. By 42 and 60 days p.i., reactivity to those proteins was more intense, but no additional bands were detected. No C. trachomatis-specific antibodies were detected by Western blot assays of the SCID and noninfected control mice. The strip tested with polyclonal sera from mice infected intranasally, serving as a positive control, also showed a positive reaction, with additional bands with masses of 25, 70, 100, and 120 kDa, as well as a positive reaction to lipopolysaccharide.

FIG. 1.

Western blot of C. trachomatis serovar D EB probed with serum samples collected from WT C3H mice infected in the meatus urethra with serovar D. Lane 1, molecular mass standards; lane 2, preinfection serum; lanes 3 to 6, serum samples collected at 10, 21, 28, and 42 days p.i.; lane 7, EB probed with sera from mice inoculated intranasally with C. trachomatis serovar D.

To characterize the cellular immune responses to C. trachomatis serovar D, T-cell-enriched splenocytes from WT and SCID mice were tested for their proliferative responses to EB at 42 days p.i. As a control, splenocytes from the sham-infected male were used. As shown in Table 3, in comparison to the control animals, a significant proliferative response to EB was observed with the T-cell-enriched splenocytes from the infected WT mice in comparison to the noninfected group. As expected, no significant differences in the proliferative responses were observed between the infected and sham-infected SCID mice.

Histopathological analyses.

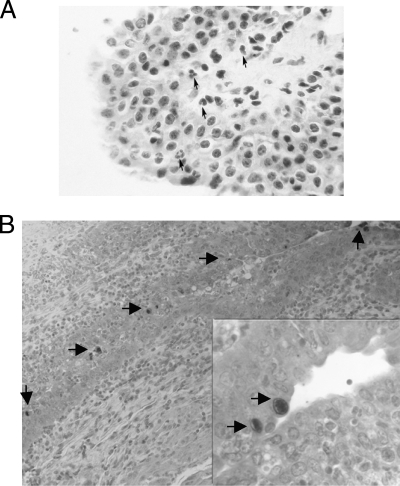

At days 1, 3, 5, 10, 21, 28, 42, and 60 p.i., tissue sections from the urethra, urinary bladder, epididymides, and testes from the WT and SCID mice inoculated with 106 C. trachomatis IFU were prepared for histopathological analysis. In the WT and SCID mice at 5 and 10 days p.i., the urethra showed few focal areas with minimal acute inflammatory infiltrate consisting of polymorphonuclear neutrophils located in the lamina propria and infiltrating the epithelium (Fig. 2A). A similar type of very focal and limited inflammatory infiltrate was detected in the urethra by 21 days p.i. At 42 and 60 days p.i., histological sections of the urethra appeared normal. In the urinary bladder, focal acute inflammatory infiltrates were detected in only a few sections at 10 days p.i. Sections of the epididymides and testes showed no inflammatory changes. Inclusions were detected in the epithelia of the urethras from the WT and SCID mice using Chlamydia-specific monoclonal antibodies (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

(A) Histopathological section from the urethra of a WT mouse infected with C. trachomatis serovar D (hematoxylin and eosin; magnification, ×400). The arrows point to polymorphonuclear neutrophils. (B) Section of the urethra from a WT mouse stained with a monoclonal antibody to Chlamydia and a secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase Arrows point to chlamydial inclusions. Magnification, ×250; inset, ×750.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that inoculation of WT male C3H/HeN mice in the meatus urethra with C. trachomatis serovar D resulted in an infection mainly localized to the lower genitourinary tract that cleared spontaneously in a period of less than 6 weeks. In contrast, SCID male mice were not able to clear the infection during the 9 weeks of observation. This is, to our knowledge, the first time that, using the natural route of inoculation, an infection of the genital tract of the male mouse was achieved with a human serovar of C. trachomatis. Our data also suggest that, at least in male mice, the adaptive immune response is necessary for clearing an infection with a human C. trachomatis serovar.

The results with the human C. trachomatis D serovar contrast with the data we previously obtained with MoPn (25). In the case of WT C3H/HeN mice infected with 106 IFU of MoPn, the yields of IFU recovered from the four organs were several log units higher than the organ cultures from the animals inoculated with serovar D. In addition, more than 50% of the mice inoculated with 106 IFU of MoPn had positive cultures for the 42 days of observation. Therefore, although WT C3H/HeN mice have the same susceptibility to the MoPn and serovar D as shown bt the ID50, they can clear the human serovar more effectively than the mouse serovar.

Although the infection with serovar D remained primarily localized to the urethra and the urinary bladder, the WT mice mounted significant humoral and cellular immune responses. IgM, IgG, and IgA Chlamydia-specific antibodies were detected in serum, and EB elicited a significant proliferative response in splenocytes. Based on the IgG2a/IgG1 ratio, the immune response was predominantly of the Th1 type. In the MoPn male and female models, following a chlamydial genital infection, predominant Th1 responses have also been described (20, 25). Thus, the findings reported here show that a similar type of immune response occurs in the male murine model infected with a human serovar.

Based on these results, and those previously reported for MoPn, there appear to be similarities between the infections of male and female animals with the human and mouse chlamydial isolates. In both the female and male mouse models, MoPn induced a more severe, disseminated, and long-lasting infection than the human serovars (6, 11, 20, 24, 25). Furthermore, the local inflammatory response was much more robust against the mouse than against the human serovar (25).

Nelson et al. (22) have proposed that the different virulences observed in the mouse model between the C. trachomatis human serovars and MoPn is due to gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-mediated immunity. In murine epithelial cells, IFN-γ elicits expression of p47 GTPases that can inhibit the human serovars, but not MoPn. This results from the ability of MoPn to produce a protein (TC0437, TC0438, or TC0439) with homology to the clostridial toxin (LCT) and to the Yersinia YopT protein that can block the GTPases. The human serovars do not code for this protein and therefore cannot block the GTPases. Hence, inoculation of mice with the human serovars leads to inhibition by p47 GTPases, in particular Iigp1, which results in a limited infection, while a more severe infection occurs if the animals are inoculated with MoPn. Nelson et al. (22) proposed a different situation with regard to mechanisms of infection in humans. In human epithelial cells, IFN-γ induces indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, which blocks Chlamydia growth by depleting tryptophan pools. In this case, the human serovars are able to grow because, unlike MoPn, they code for a functional tryptophan synthase that can use indole to synthesize tryptophan.

Migration of Chlamydia from the urethra to the epididymides and the testes may occur by several mechanisms. Chlamydia may ascend by the intraluminar route or may disseminate by the hematogenous or lymphatic route. If, as proposed by Nelson et al., (22), the human serovars are blocked by the p47 GTPases, this may explain the very limited dissemination of the D serovar to the testes and epididymides. Another possibility could be that the epididymides and testes of mice lack receptors for the human serovars of Chlamydia, and as a result, they cannot be infected. This, however, does not appear to be the case. For example, Kuzan et al. (13) inoculated the epididymides of B6D2F1 mice with 2.8 × 108 IFU of C. trachomatis serovar E and observed a severe acute inflammatory infiltrate by 3 days p.i. that subsided by 3 weeks p.i. Our results with the WT and SCID mice also support the premise that the human serovars can infect the epididymides. The data with the SCID mice, however, do not support the premise of Nelson et al. (22) that the local innate immune response blocks dissemination by controlling the infection at the site of entry. In SCID mice, the innate immunity is presumably intact (17). The fact that the WT mice had cleared the infection by 42 days p.i. while the SCID mice continued to have positive cultures thereafter suggests that the adaptive immune response plays a role in controlling an infection with a human serovar in the male mouse model. We are not aware of a publication describing the outcome of an infection of a female SCID mouse model with a human serovar of C. trachomatis. Therefore, our findings cannot be extrapolated at this point to the female mouse model.

Tuffrey et al. (39) inoculated medroxyprogesterone (Depo Provera)-treated WT CBA and congenic CBA nude mice with a lymphogranuloma venereum strain (SF-2f) in the uterus. The number of IFU recovered from the vagina was significantly greater in the nude mice than that yielded by the immunologically competent animals. However, the infection was self-limited, lasting approximately 60 days, and there was no statistical difference in the duration of the shedding in the nude and WT mice. Based on these results, the authors concluded that T lymphocytes and T-lymphocyte-dependent antibodies have minimal effects on the course of a Chlamydia infection with a human serovar in mice. Taking the Tuffrey et al. (39) model and ours together, it appears that a murine infection with a human serovar requires at least B cells and/or antibodies for clearance.

Nonhuman primates could be ideal models to study infections with the C. trachomatis human serovars (7, 12, 19, 26, 37). For example, Taylor-Robinson et al. (37) inoculated three male chimpanzees in the urethra with human serovars and obtained positive urethral cultures from two of the animals. However, no clinical evidence of epididymitis or orchitis was observed. On the other hand, direct inoculation of the C. trachomatis K serovar into the spermatic cords of two grivet monkeys resulted in swelling of the epididymides and spermatic cords that were infiltrated with polymorphonuclear neutrophils and lymphocytes (19). Another useful model to characterize genital chlamydial infections in males is the guinea pig. The Chlamydia caviae (also called Chlamydia psittaci guinea pig inclusion conjunctivitis agent) is a natural pathogen of guinea pigs. Inoculation of male guinea pigs in the meatus urethra with guinea pig inclusion conjunctivitis agent resulted in urethritis and cystitis (32). In addition, Rank et al. (31) utilized this animal model to characterize sexual transmission from male to female animals. Therefore, we now have three animal models that can be used to characterize the immunopathogenesis of a chlamydial genital infection in males.

In conclusion, we have shown that, when delivered by the natural route of entry, a human C. trachomatis serovar can produce an infection of the lower genitourinary tract in WT C3H/HeN male mice. In spite of the infection remaining localized, the mice mounted significant systemic humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to Chlamydia. The similarities and differences between this model and a chlamydial infection in human males remain to be investigated. In humans, approximately 50 to 70% of the C. trachomatis infections in males are asymptomatic, indicative of minimal inflammatory reaction, and the infection is mainly limited to the urethra. In most instances, male patients, even if untreated, resolve the infection without long-term sequelae. Thus, although the immunopathogeneses of the infections may differ, this model may parallel the clinical presentation most frequently encountered in humans. Furthermore, the fact that SCID mice were unable to clear the infection suggests that the adaptive immune response is necessary, at least in male mice, for controlling an infection with a human C. trachomatis serovar.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI-67888 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Editor: R. P. Morrison

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 October 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler, M. W. 2003. Sexual health: health of the nation. Sex. Transm. Infect. 79:84-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anttila, T., P. Saikku, P. Koskela, A. Bloigu, J. Dillner, I. Ikaheimo, E. Jellum, M. Lehtinen, P. Lenner, T. Hakulinen, A. Narvanen, E. Pukkala, S. Thoresen, L. Youngman, and J. Paavonen. 2001. Serotypes of Chlamydia trachomatis and risk for development of cervical squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA 285:47-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger, R. E. 1999. Acute epididymitis, p. 847-858. In K. K. Holmes et al. (ed.), Sexually transmitted diseases. McGraw Hill, New York, NY.

- 4.Caldwell, H. D., J. Kromhout, and J. Schachter. 1981. Purification and characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 31:1161-1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham, K. A., and K. W. Beagley. 2008. Male genital tract chlamydial infection: implications for pathology and infertility. Biol. Reprod. 79:180-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de la Maza, L. M., S. Pal, A. Khamesipour, and E. M. Peterson. 1994. Intravaginal inoculation of mice with the Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis biovar results in infertility. Infect. Immun. 62:2094-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Digiacomo R. F., J. L. Gale, S.-P. Wang, and M. D. Kiviat. 1975. Chlamydial infection of the male baboon urethra. Br. J. Vener. Dis. 51:310-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez-Jimenez, M. A., and C. A. Villanueva-Diaz. 2006. Epididymal stereocilia in semen of infertile men: evidence of chronic epididymitis? Andrologia 38:26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grayston, J. T., and S.-P. Wang. 1975. New knowledge of Chlamydiae and the diseases they cause. J. Infect. Dis. 132:87-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosseinzadeh, S., I. A. Brewis, A. A. Pacey, H. D. M. Moore, and A. Eley. 2000. Coincubation of human spermatozoa with Chlamydia trachomatis in vitro causes increased tyrosine phosphorylation of sperm proteins. Infect. Immun. 68:4872-4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito, J. I., J. M. Lyons, and L. P. Airo-Brown. 1990. Variation in virulence among oculogenital serovars of Chlamydia trachomatis in experimental genital tract infection. Infect. Immun. 58:2021-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson, A. P., and D. Taylor-Robinson. 1982. Chlamydial genital tract infection. Experimental infection of the primate genital tract with Chlamydia trachomatis. Am. J. Pathol. 106:132-135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuzan, F. B., D. L. Patton, S. M. Allen, and C.-C. Kuo. 1989. A proposed mouse model for acute epididymitis provoked by genital serovar E, Chlamydia trachomatis. Biol. Reprod. 40:165-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaMontagne, D. S., D. N. Fine, and J. M. Marrazzo. 2003. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in asymptomatic men. Am. J. Prev. Med. 24:36-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin, D. H., and W. R. Bowie. 1999. Urethritis in males, p. 761-781. In K. K. Holmes et al. (ed.), Sexually transmitted diseases. McGraw Hill, New York, NY.

- 16.Massari, V., Y. Dorleans, and A. Flahault. 2006. Persistent increase in the incidence of acute male urethritis diagnosed in general practices in France. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 56:110-114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald, V., and G. J. Bancroft. 1994. Mechanisms of innate and acquired resistance to Cryptosporidium parvum infection in SCID mice. Parasite Immunol. 16:315-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller, W. C., C. A. Ford, M. Morris, M. S. Handcock, J. L. Schmitz, M. M. Hobbs, M. S. Cohen, K. M. Harris, and J. R. Udry. 2004. Prevalence of chlamydial and gonococcal infections among young adults in the United States. JAMA 291:2229-2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moller, B. R., and P.-A. Mardh. 1980. Experimental epididymitis and urethritis in grivet monkeys provoked by Chlamydia trachomatis. Fert. Steril. 34:275-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison, R. P., and H. D. Caldwell. 2002. Immunity to murine chlamydial genital infection. Infect. Immun. 70:2741-2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munday, P. E., J. M. Carder, and D. Taylor-Robinson. 1985. Chlamydial proctitis? Genitourin. Med. 61:376-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson, D. E., D. P. Virok, H. Wood, C. Roshick, R. M. Johnson, W. M. Whitmire, D. D. Crane, O. Steele-Mortimer, L. Kari, G. McClarty, and H. D. Caldwell. 2005. Chlamydia IFN-γ immune evasion is linked to host infection tropism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:10658-10663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nigg, C. 1942. An unidentified virus which produces pneumonia and systemic infection in mice. Science 99:49-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pal, S., T. J. Fielder, E. M. Peterson, and L. M. de la Maza. 1994. Protection against infertility in a BALB/c mouse salpingitis model by intranasal immunization with the mouse pneumonitis biovar of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 62:3354-3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pal, S., E. M. Peterson, and L. M. de la Maza. 2005. New murine model for the study of Chlamydia trachomatis genitourinary tract infections in males. Infect. Immun. 72:4210-4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton, D. L., Y. T. Sweeney, and W. E. Stamm. 2005. Significant reduction in inflammatory response in the macaque model of chlamydial pelvic inflammatory disease with azithromycin treatment. J. Infect. Dis. 192:129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearson, R. C., C. D. Baumber, D. McGhie, and I. V. Thambar. 1988. The relevance of Chlamydia trachomatis in acute epididymitis in young men. Br. J. Urol. 62:72-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson, E. M., X. Cheng, S. Pal, and L. M. de la Maza. 1993. Effects of antibody isotype and host cell type on in vitro neutralization of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 61:498-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plummer, F. A., J. N. Simonsen, D. W. Cameron, J. O. Ndinya-Achola, J. K. Kreiss, M. N. Gkinya, P. Waiyaki, M. Cheang, P. Piot, and A. R. Ronald. 1991. Cofactors in male-female sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Infect. Dis. 164:1236-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quinn, T. C., S. E. Goodell, E. Mkrtichian, M. D. Schuffler, S.-P. Wang, W. E. Stamm, and K. K. Holmes. 1981. Chlamydia trachomatis proctitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 305:195-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rank, R. G., A. K. Bowlin, R. L. Reed, and T. Darville. 2003. Characterization of chlamydial genital infection resulting from sexual transmission from male to female guinea pigs and determination of infectious dose. Infect. Immun. 71:6148-6154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rank, R. G., H. J. White, B. L. Soloff, and A. L. Barron. 1981. Cystitis associated with chlamydial infection of the genital tract in male guinea pigs. Sex. Transm. Dis. 8:203-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reed, L. J., and H. A. Muench. 1938. Simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoint. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schachter, J., and C. Dawson. 1978. Human chlamydial infections. PSG Publishing, Littleton, MA.

- 35.Schagger, H., and G. Von Jagow. 1987. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166:368-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stamm, W. E. 1999. Chlamydia trachomatis infections of the adult, p. 407-422. In K. K. Holmes et al. (ed.), Sexually transmitted diseases. McGraw Hill, New York, NY.

- 37.Taylor-Robinson, D., R. H. Purcell, W. T. London, D. L. Sly, B. J. Thomas, and R. T. Evans. 1981. Microbiological, serological, and histopathological features of experimental Chlamydia trachomatis urethritis in chimpanzees. Br. J. Vener. Dis. 57:36-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toth, M., D. L. Patton, L. A. Campbell, E. Il Carretta, J. Mouradian, A. Toth, M. Sheychuk, R. Baergen, and W. Ledger. 2000. Detection of chlamydial antigenic material in ovarian, prostatic, ectopic pregnancy and semen samples of culture-negative subjects. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 43:218-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tuffrey, M., P. Falder, and D. Taylor-Robinsion. 1982. Genital-tract infection and disease in nude and immunologically competent mice after inoculation of a human strain of Chlamydia trachomatis. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 63:539-546. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westrom, L., R. Joesoef, G. Reynolds, A. Hagdu, and S. E. Thompson. 1992. Pelvic inflammatory disease and fertility: a cohort study of 1,844 women with laparoscopically verified disease and 657 control women with normal laparoscopy. Sex. Transm. Dis. 19:185-192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]