Abstract

Dextran-dependent aggregation (DDAG) of Streptococcus mutans is an in vitro phenomenon that is believed to represent a property of the organism that is beneficial for sucrose-dependent biofilm development. GbpC, a cell surface glucan-binding protein, is responsible for DDAG in S. mutans when cultured under defined stressful conditions. Recent reports have described a putative transcriptional regulator gene, irvA, located just upstream of gbpC, that is normally repressed by the product of an adjacent gene, irvR. When repression of irvA is relieved, there is a resulting increase in the expression of GbpC and decreases in competence and synthesis of the antibiotic mutacin I. This study examined the role of irvA in DDAG and biofilm formation by engineering strains that overexpressed irvA (IrvA+) on an extrachromosomal plasmid. The IrvA+ strain displayed large aggregation particles that did not require stressful growth conditions. A novel finding was that overexpression of irvA in a gbpC mutant background retained a measure of DDAG, albeit very small aggregation particles. Biofilms formed by the IrvA+ strain in the parental background possessed larger-than-normal microcolonies. In a gbpC mutant background, the overexpression of irvA reversed the fragile biofilm phenotype normally associated with loss of GbpC. Real-time PCR and Northern blot analyses found that expression of gbpC did not change significantly in the IrvA+ strain but expression of spaP, encoding the major surface adhesin P1, increased significantly. Inactivation of spaP eliminated the small-particle DDAG. The results suggest that IrvA promotes DDAG not only by GbpC, but also via an increase in P1.

Streptococcus mutans is considered the main etiological agent of dental caries (10, 20). A prominent virulence property of this species is its ability to adhere to tooth surfaces in the presence of dietary sucrose. Dextran-dependent aggregation (DDAG) is an in vitro phenomenon that is believed to represent a property of the organism that is beneficial for sucrose-dependent biofilm development. It can be described as the formation of bacterial aggregates or flocculation upon the addition of dextran to an overnight culture of bacteria grown in the absence of sucrose. In this instance, the dextran simulates the glucan that would be synthesized if sucrose were present. DDAG was originally reported for Streptococcus sobrinus and Streptococcus criceti (7). It was regarded as specific for these two mutans streptococcal species until Sato et al. demonstrated DDAG of S. mutans following growth under a variety of stress conditions, including subinhibitory concentrations of tetracycline, ethanol, or xylitol (27, 28). S. mutans DDAG was attributed to GbpC, a wall-anchored surface glucan-binding protein encoded by the gbpC gene (27). However, GbpC alone does not appear to account for DDAG, as transcription of gbpC does not increase under some growth conditions that promote DDAG (4).

Located just upstream of gbpC is a putative transcriptional regulator gene, irvA (Fig. 1), that has been found to contribute to repression of mutacin I gene expression and is thought to be part of a stress regulon (24, 31). The predicted IrvA amino acid sequence is 79 residues and bears a helix-turn-helix domain characteristic of the Cro/cI family of transcriptional regulators (2). Under routine growth conditions in the laboratory, irvA appears to be repressed by the product of an adjacent gene, irvR (25). Similarly, gbpC is transcribed under routine laboratory conditions despite the potential to be repressed by CovR (GcrR) (4, 29) and perhaps by another, as yet unidentified, regulator (29). Derepression of irvA following mutation of irvR leads to prolific DDAG and enhanced GbpC expression (25).

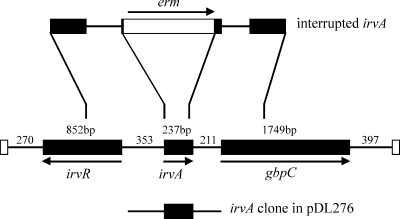

FIG. 1.

The chromosomal locus harboring genes irvR, irvA, and gbpC is depicted (middle), along with representations depicting the construction of the irvA mutant (top) and the cloning of irvA and the flanking DNA (bottom). The arrows indicate gene orientation. The numbers indicate the lengths of the genes or intergenic regions in base pairs.

Taken together, these observations suggest that the DDAG phenotype in S. mutans is most advantageous under conditions of stress. The ability of bacteria to autoaggregate has been proposed to be an important step in biofilm formation (17), though several other theories have been proposed as well. These include protection against predation or environmental stresses, or responses to nutrient conditions (8). It is curious that the mutans streptococci, which share similar virulence traits responsible for caries in animals or humans, are divided between species for which DDAG is a constitutive property and those for which DDAG is induced only under growth conditions that simulate stress. This study was undertaken to further examine the conditions under which DDAG is induced in S. mutans and to investigate its effects on biofilm formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

Escherichia coli JM109 was used for the intermediate cloning steps. Streptococcus mutans UA159 was used as the parental strain for all genetically engineered S. mutans strains, including those harboring irvA on an extrachromosomal plasmid, as well as strains wherein gbpC, irvA, or spaP is inactivated. Table 1 lists the strains used in this study. E. coli was cultured in Luria broth (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) at 37°C with shaking. Streptococci were cultured on Todd-Hewitt plates (Becton, Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ) and in chemically defined medium (CDM) (SAFC Biosciences, Inc., Lenexa, KS) and were grown at 37°C in an anaerobic chamber (5% CO2, 10% H2, 85% N2). Biofilms were cultured in CDM with 1% sucrose and grown at 37°C in 5% CO2.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| S. mutans strain | Description | Antibiotic resistancea | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| UA159 | Wild-type S. mutans | None | 2 |

| MZ159VC | UA159 with pDL276; vector control | Km | This study |

| MZ159A | UA159 irvA overexpresser (IrvA+) | Km | This study |

| MZ159i | UA159 irvA mutant | Em | This study |

| MZ159c | UA159 gbpC mutant | Sp | This study |

| MZ159Ac | UA159 gbpC mutant, irvA overexpresser | Sp, Km | This study |

| MZ159Acp | UA159 gbpC spaP mutant, irvA overexpresser | Sp, Km, Em | This study |

Km, kanamycin (800 μg/ml); Em, erythromycin (25 μg/ml); Sp, spectinomycin (500 μg/ml).

Cloning and overexpression of irvA.

The irvA gene was cloned into the shuttle vector pDL276 (19). The cloned portion of irvA extended from 317 bp upstream of the irvA start codon (primer 5′-XbaI-CATGCTTCACCTTC-3′) to 206 bp downstream of the irvA termination codon (primer 5′-BamHI-AAACCATCCTTTATATT-3′) (Fig. 1). The shuttle vector pDL276 with irvA was transformed into the parental strain, S. mutans UA159, and gbpC mutant strains to generate overexpressing strains (IrvA+). Vector control strains contained pDL276 without the irvA insert. For transformation, overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 in medium containing 5% horse serum (23). The bacteria were incubated 2 h following the initial dilution, 0.8 μg/ml of a synthetic competence-stimulating peptide (SGSLSTFFRLFNRSFTQALGK) was added, and the bacteria were incubated another 0.5 h prior to addition of DNA. The culture was then incubated 3 h at 37°C and plated onto medium containing 800 μg/ml kanamycin.

Inactivation of irvA and spaP.

A mutant strain in which irvA is inactivated was engineered by allelic replacement. DNA upstream and downstream of irvA was amplified by PCR and cloned on either side of an erythromycin resistance cassette (erm) (Fig. 1). The upstream amplification began 707 bp upstream of the irvA start codon (primer 5′-PstI-CTCAGTCGTTTCATCACTGG-3′) and ended 5 bp into the irvA reading frame (primer 5′-XbaI-CTGCATAGGAATCATTACCT-3′). The downstream amplification began 37 bp prior to the irvA termination codon (primer 5′-BamHI-TTACTATGATATCAGTTTAG-3′) and ended 700 bp downstream of the irvA termination codon (primer 5′-KpnI-TGAGCTTCATACTCCTTGAC-3′). A linear fragment containing these regions was then used to transform S. mutans. Homologous recombination on either side of erm resulted in a replacement of irvA, which was confirmed using conventional PCR, and real-time PCR was used to confirm the lack of irvA transcription. A spaP mutant was engineered by insertional inactivation. A 703-bp internal portion of spaP from base 466 (primer 5′-ACAGCTGAAGAAGCAGTCCAAAAAGAAA-3′) to base 1142 (primer 5′-TCACAGCTGAAAATACTGCAATTAAGAA-3′) was amplified by PCR and cloned into the suicide vector pVA8912 (30). This construct was transformed into S. mutans wherein a single homologous recombination generated two incomplete copies of spaP. Conventional PCR was used to confirm the genotype, and real-time PCR was used to confirm the lack of spaP transcription.

DDAG.

Overnight cultures, grown in CDM with or without 4% ethanol, were washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4). Dextran T2000 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. The tubes were then incubated at 37°C for 1 h, with optical density (OD) measurements at 660 nm taken at 0, 2, 15, 30, and 60 min. Small-particle aggregation was visualized following a 1:2 dilution in PBS.

Biofilm growth and analysis.

Biofilms of parental and mutant strains were formed in 24-well polystyrene plates (Costar 3526; Corning Inc., Corning, NY) or in glass-bottom culture dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA) when biofilms were to be analyzed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. The culture dishes were first incubated with sterile, diluted saliva for 3 h at 37°C, which was aspirated prior to the addition of medium (CDM with 1% sucrose), and then inoculated with growth from overnight cultures of test strains. The biofilms were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2 on a fixed-angle rotator at a rotation speed of 10 rpm and an angle of 60° overnight or for 2 days with a change in medium after 24 h (3). Biofilms in polystyrene dishes were washed, stained with safranin, and photographed against a light box. Biofilms for confocal microscopy were rinsed twice in PBS and stained for 35 min with SYTO9 (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) and then rinsed twice more with PBS. One milliliter of PBS was added to the wells to prevent drying of the biofilm during image collection. Biofilm images of the substratum were collected using a Bio-Rad Radiance 2100MP multiphoton/confocal microscope. Particle counts and particle sizes of microcolonies at the substratum were calculated using ImageJ 1.40 and averaged from three random fields.

Real-time PCR.

Total RNA from each bacterial strain was isolated using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). Relative expression levels of gbpC and spaP were measured by quantitative real-time PCR, using equivalent amounts of RNA. Results were normalized to gyrA transcription. The gbpC or spaP expression was set at 1 for the parental strain. Reactions were set up using the iScript one-step reverse transcription-PCR kit with SYBR green (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and tested in an iQ5 real-time PCR detection system. Each sample was tested in duplicate during a trial, and four independent trials were performed.

Northern blotting.

mRNA from each bacterial strain was isolated by the MicrobExpress bacterial mRNA purification kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Northern blot analyses employed equivalent amounts of mRNA (100 ng) for each sample and were performed using the NorthernMax formaldehyde-based system (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

Our laboratory has had a longstanding focus on S. mutans glucan-binding proteins, so the proximity of irvA, a putative transcriptional regulator gene, to gbpC was of interest. Initially, it was determined that overexpression of irvA in the parental or gbp mutant backgrounds enhanced the DDAG of S. mutans. In particular, strains carrying a copy of irvA on an extrachromosomal plasmid (IrvA+) were capable of DDAG even when grown in the absence of stress (Fig. 2A). Stress was simulated by adding 4% ethanol to the growth medium. The expression of irvA was enhanced approximately 2.5-fold in the IrvA+ strains (Fig. 3), whereas ethanol had no effect on irvA expression. An S. mutans irvA mutant strain behaved similarly to the wild-type parental strain (Fig. 2A).

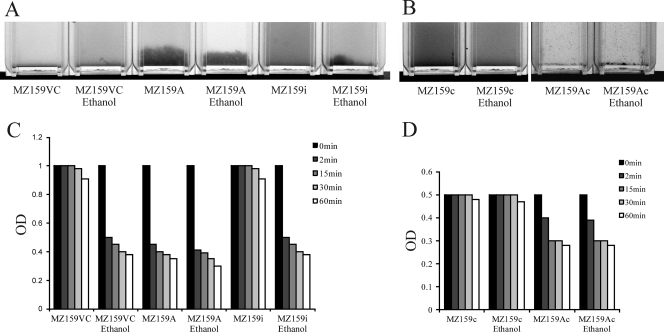

FIG. 2.

Strains carrying a copy of irvA on an extrachromosomal plasmid (IrvA+), or parental vector control strains carrying the plasmid without irvA, were tested for DDAG when grown with or without 4% ethanol added to the growth medium. (A) In S. mutans, the IrvA+ strain (MZ159A) was capable of DDAG under both growth conditions, whereas the parental vector control (MZ159VC) and irvA mutant (MZ159i) strains displayed DDAG only when grown with ethanol. (B) In a gbpC mutant background (MZ159c), S. mutans lost the ability to form large aggregates as a result of DDAG, but the plasmid-based copy of irvA (MZ159Ac) resulted in tiny, dense aggregates under either growth condition. In order to visualize these aggregates more easily, the suspension of bacteria was diluted and the photographic contrast exaggerated. (C) The magnitudes of DDAG in the IrvA+ and parental vector control strains were quantified by measuring the decreases in OD over a period of 60 min. The histogram shows that DDAG by S. mutans resulted in an almost immediate decrease in OD when the parental vector control (MZ159VC) or irvA mutant (MZ159i) strains were grown in the presence of ethanol. An identical reduction in OD occurred in the IrvA+ (MZ159A) strain but was independent of the growth condition. (D) In the S. mutans gbpC mutant background (MZ159c), reductions in OD were evident in the strain carrying a plasmid copy of irvA (MZ159Ac), albeit more modestly than when large aggregates were formed. These reductions were independent of the growth condition.

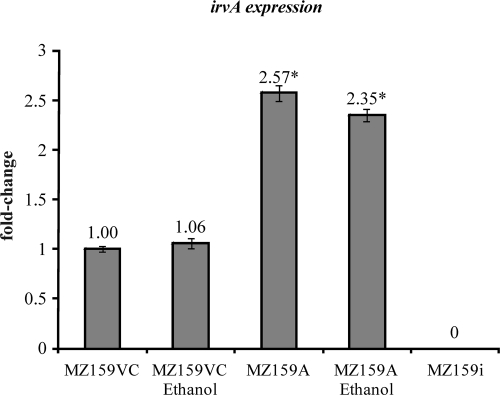

FIG. 3.

Real-time PCR was used to measure the relative transcriptions of irvA in parental vector control (MZ159VC) and IrvA+ (MZ159A) strains. The data were normalized to gyrA expression, and then between strains by setting expression in the parental strain to 1. Addition of ethanol to the growth medium had no effect on irvA expression. The expression of irvA was increased approximately 2.5-fold in the IrvA+ strain, a difference that was statistically significant (marked by an asterisk) based upon a Student t test (P < 0.05). As expected, no transcription could be detected in an irvA mutant strain (MZ159i).

Since GbpC was known to be linked to DDAG in S. mutans, an irvA-overexpressing strain was engineered in a gbpC mutant background. As expected, large aggregates of bacteria no longer appeared upon the addition of dextran. However, DDAG did not disappear altogether. The plasmid-based copy of irvA resulted in tiny, dense aggregates that quickly fell to the bottom of the tube (Fig. 2B). The two forms of DDAG could be distinguished spectrophotometrically as well. Figure 2C shows that DDAG resulted in an almost immediate decrease in OD when the parental or irvA mutant strains were grown in the presence of stress. An identical reduction in OD occurred in the IrvA+ strain but was independent of stress. When irvA was overexpressed in a gbpC mutant background (Fig. 2D), the reductions in OD due to small-particle aggregation were more modest than when large aggregates were formed, and were independent of stress.

Not only did the IrvA+ strain display stress-independent DDAG, the DDAG that occurred following growth under stress appeared to be more robust than that formed by the parental vector control strain. To determine whether this observation could be explained by increased expression of GbpC, transcription of gbpC was measured by quantitative real-time PCR. As shown in Fig. 4A, the IrvA+ strain displayed only a slight increase in expression that appeared to be within the margin of experimental error. A Northern blot (Fig. 4B) also supported a conclusion that gbpC expression was not appreciably changed in the IrvA+ strain.

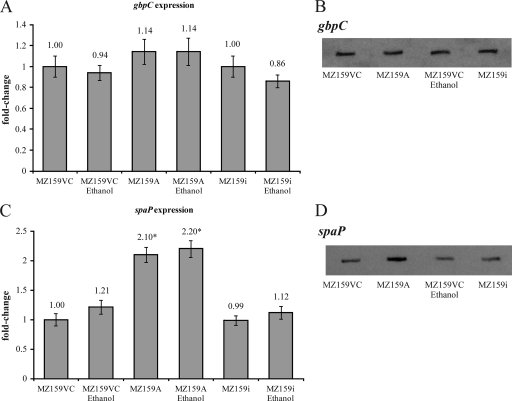

FIG. 4.

Transcription of gbpC and spaP was measured by real-time PCR (A and C) and by Northern blotting (B and D). (A) The IrvA+ strain (MZ159A) displayed only a slight increase in expression of gbpC relative to that for the parental vector control (MZ159VC). The difference was within the margin of experimental error. Growth in the presence of ethanol did not increase expression of gbpC. (B) A Northern blot also supported a conclusion that gbpC expression was not appreciably changed in the IrvA+ strain (MZ159A). (C) The expression of the gene encoding P1, spaP, was examined in the IrvA+ strain (MZ159A) and found to be significantly enhanced (marked by an asterisk) compared to expression in the parental vector control (MZ159VC) as determined by a Student t test comparing the mean values of four independent trials (P < 0.05). (D) The induction of spaP was further confirmed by Northern blot analysis. In all instances, the irvA mutant (MZ159i) was similar to the parental vector control (MZ159VC).

Since the prominent surface antigen P1 was once described as a possible glucan-binding protein (5), the expression of the gene encoding P1, spaP, was examined in the IrvA+ strain and found to be significantly enhanced (Fig. 4C). The induction of spaP was further confirmed by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 4D). To determine whether an increase in P1 could account for the small aggregates formed in the absence of GbpC, DDAG was tested in an IrvA+ strain that had mutations of both gbpC and spaP. The loss of P1 resulted in the ablation of DDAG (Fig. 5).

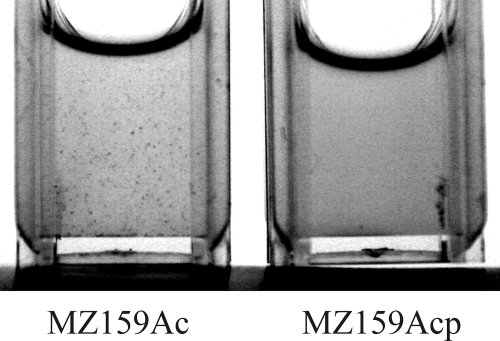

FIG. 5.

DDAG was tested in an IrvA+ strain (MZ159Acp) that had mutations in both gbpC and spaP and compared to DDAG in an IrvA+ strain that had a mutation only in gbpC (MZ159Ac). The loss of P1 resulted in the ablation of the small-particle DDAG.

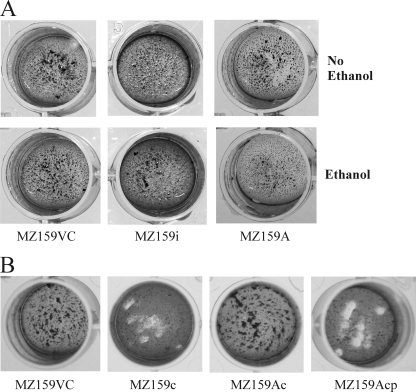

Next, the impact of DDAG on biofilm formation was analyzed. Biofilms were generated in saliva-coated polystyrene wells and stained with safranin to view the overall appearance of the mature biofilm (Fig. 6). The overexpression of irvA (MZ159A) in the parental background did not alter biofilm appearance, nor did a mutation in irvA (MZ159i) (Fig. 6A). The parental vector control strain (MZ159VC), the irvA mutant strain (MZ159i), and the IrvA+ strain (MZ159A) all formed similar biofilms whether or not ethanol, which stimulates DDAG, was present (Fig. 6A). However, GbpC, the main mediator of large-particle DDAG, was necessary to maintain a biofilm morphology similar to that of the parental strain (Fig. 6B; compare the parental vector control, MZ159VC, with the gbpC mutant, MZ159c), even when grown in the absence of ethanol. The overexpression of irvA in the gbpC mutant background (MZ159Ac) compensated for the loss of GbpC, resulting in a biofilm similar to that generated by the parental strain (MZ159VC). When the spaP gene was inactivated (MZ159Acp), the overexpression of irvA was no longer able to restore the biofilm appearance that resulted from loss of GbpC (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Photographic images of mature biofilms formed by parental vector control and IrvA+ strains. (A) IrvA made little, if any, contribution to the macroscopic appearance of biofilms since biofilms produced by an irvA mutant (MZ159i) and an IrvA+ strain (MZ159A) appeared to be similar to those of the parental vector control (MZ159VC) strain. Growth in ethanol (second row of images), which stimulates DDAG, did not affect biofilm morphology for any of the strains. (B) The loss of GbpC (MZ159c) changed the biofilm appearance compared to that of the parental vector control strain (MZ159VC), despite growth under a condition that does not promote DDAG (no ethanol). Overexpression of irvA (MZ159Ac) overcame the change in biofilm appearance caused by the loss of GbpC, unless the spaP gene was inactivated (MZ08Acp).

In an effort to determine the basis for the changes in biofilm appearance, mature biofilms were examined by confocal microscopy. Differences at the substratum were immediately apparent. To quantify these differences, substratum images from three random fields were analyzed by the program ImageJ to calculate the average numbers and sizes of microcolonies. These are designated particle count and particle size in Table 2. The IrvA+ strain (MZ159A) formed biofilms with significantly fewer microcolonies of larger average size than did the parental strain (MZ159VC). Microcolonies within biofilms formed by an irvA mutant (MZ159i) did not differ from those formed by the parental strain. The inactivation of gbpC (MZ159c) led to very small microcolonies with significantly reduced particle size and significantly increased particle count relative to those for the parental strain. These GbpC-based changes had previously been reported in a qualitative manner (22). When irvA was added to the gbpC mutant background (MZ159Ac), the particle count significantly decreased, and the particle size significantly increased relative to those for the gbpC mutant strain (MZ159c). These data demonstrate that the overexpression of irvA significantly increases the size of individual microcolonies.

TABLE 2.

Confocal image analysis of biofilm microcolonies at the substratum

| S. mutans strain | Particle count | Particle size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| MZ159VC | 4,549 ± 186 | 70.0 ± 7.6 |

| MZ159A | 3,917 ± 67a | 110.9 ± 12.1a |

| MZ159i | 5,521 ± 191 | 72.9 ± 7.8 |

| MZ159c | 11,376 ± 879a | 38.2 ± 5.4a |

| MZ159Ac | 2,149 ± 102b | 65.7 ± 8.0b |

Significantly different from the parental strain (MZ159VC) based on a Student t test comparing means.

Significantly different from MZ159c based on a Student t test comparing means.

DISCUSSION

The precise significance of DDAG as it relates to S. mutans sucrose-dependent adhesion and biofilm formation is still a subject of speculation. DDAG is apparent under routine laboratory culture conditions for some closely related species within the mutans streptococci but is induced in S. mutans only under stressful growth conditions, such as the inclusion of 4% ethanol or sublethal dosages of antibiotics in the growth medium (27). S. mutans DDAG has been attributed to GbpC (27), yet gbpC is expressed even in the absence of DDAG, and Biswas et al. (4) report that transcription of gbpC does not increase when ethanol is added to the growth medium. Still, it appears that increased gbpC expression can promote DDAG. Sato et al. (28) reported that growth in the presence of xylitol increased both gbpC expression and DDAG. In addition, Niu et al. (25) demonstrated that inactivation of irvR, encoding a transcriptional repressor of irvA and reminiscent of the lambda cI/Cro repressor system, resulted in elevated levels of GbpC and DDAG that did not require special growth conditions. The results of the current study add another layer of complexity to DDAG and its contribution to biofilm development.

The initial observation in this study was that overexpression of irvA, accomplished by providing a copy of irvA on an extrachromosomal plasmid, induced DDAG that was independent of stressful growth conditions. A similar phenotype was observed when S. mutans irvA was introduced into Streptococcus gordonii, whereas Streptococcus mitis was unaffected (data not shown). These results suggested that DDAG is a property shared by at least one primary plaque-colonizing species and that it may be regulated by a similar mechanism. The induction of DDAG in the IrvA+ strain was not accompanied by a significant increase in transcription of gbpC. To reconcile this observation with the report that derepression of irvA leads to increased gbpC expression, we propose that the latter increase in gbpC expression is due to transcriptional read-through, rather than regulatory activity of IrvA at the gbpC promoter. Since irvA was overexpressed in trans in our experiments, transcriptional read-through was not a possibility.

Despite the fact that irvA overexpression did not result in increased expression of gbpC, inactivation of gbpC severely diminished DDAG in the IrvA+ strain. However, a novel finding was that small-particle aggregates remained even in the absence of GbpC. These were specific for the IrvA+ strain and were eventually shown to require the presence of P1. At one time, it was speculated that P1 was a glucan-binding protein (5), but no published evidence of that possibility exists. The fact that P1 shares some sequence homology with GbpC (27), along with its apparent role in forming small, dextran-induced aggregates, suggests that a possible glucan-binding role for P1 is not out of the question. Such a role might also explain why biofilms formed in the presence of sucrose by a mutant missing GbpA, -C, and -D remain significantly more robust than biofilms formed in the absence of sucrose (22). However, contributions from other cell components cannot be ruled out. For example, it has been reported that a mutation in spaP is associated with a decreased retention of WapA on the cell wall (12) and that WapA has the property of binding dextran (11).

Another unexpected conclusion from this study was that the changes that accompanied the overexpression of irvA had a significant impact on certain characteristics of sucrose-dependent biofilms. At the macroscopic level, the appearance of biofilms formed by the parental, irvA mutant, or IrvA+ strains did not appear to differ regardless of whether the biofilms were formed in the presence or absence of ethanol. Thus, the conditions that enhanced DDAG did not visibly alter biofilm morphology. Yet the loss of GbpC, the main component responsible for large-particle DDAG, resulted in biofilms that were noticeably different from those formed by the parental strain. Interestingly, the overexpression of irvA rescued the gbpC mutant biofilm phenotype. Thus, the small-particle DDAG induced by overexpression of irvA had an effect that was noticeable macroscopically only when GbpC was absent. A microscopic examination of the biofilms was made in an effort to further understand the basis for these observations. The results showed that small-particle aggregation accompanying irvA overexpression affected the size and quantity of microcolonies at the biofilm substratum. The small-particle aggregation was eliminated when the spaP gene was mutated, as was the ability of irvA overexpression to compensate for the loss of gbpC in biofilm development. These data suggest that small-particle DDAG is mediated by P1, though we did not distinguish between P1 being necessary and it being both necessary and sufficient to bring about the observed results. This study also did not address whether the increased expression of spaP in the IrvA+ background was due to direct activation by IrvA acting as a transcriptional regulator.

It is relatively common for autoaggregation to be linked to enhanced adhesion and biofilm formation in a number of human pathogens and environmental species (6, 9, 13, 18, 21, 32). Aggregation of S. mutans by salivary agglutinins, however, can either promote removal by swallowing or promote adhesion to the tooth surface (1). Since the property of DDAG in S. mutans is induced only under specific in vitro laboratory culture conditions, it is unclear whether DDAG promotes efficient adhesion and accumulation of S. mutans within the dental plaque biofilm. There appears to be at least one (CovR), if not more, repressor that can regulate gbpC expression (4, 29). In addition, induction of irvA coincides with greater gbpC expression (25). Biswas et al. (4) report that expression of gbpC is reduced at low pH, a condition that might be more common within an established biofilm.

An alternative possibility is that DDAG is a response to stress, with the aggregates being collectively more resistant to environmental conditions (8). In this scenario, the repression of irvR would induce expression of irvA and gbpC. In turn, IrvA would induce expression of spaP and perhaps several other genes.

Determining the environmental signals that regulate gbpC and remove repression of irvA may hold the keys to understanding the role of DDAG in S. mutans plaque survival. Clearly, however, DDAG encompasses aggregation of various sizes that holds substantial potential to influence how this organism interacts with its environment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant DE10058 (J.A.B.) from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and by COBRE grant RR018741 (J.M. and D.A.) from the National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 September 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, S.-J., S.-J. Ahn, Z. T. Wen, L. J. Brady, and R. A. Burne. 2008. Characteristics of biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans in the presence of saliva. Infect. Immun. 76:4259-4268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ajdić, D., W. M. McShan, R. E. McLaughlin, G. Savic, J. Chang, M. B. Carson, C. Primeaux, R. Tian, S. Kenton, H. Jia, S. Lin, Y. Qian, S. Li, H. Zhu, F. Najar, H. Lai, J. White, B. A. Roe, and J. J. Ferretti. 2002. Genome sequence of Streptococcus mutans UA159, a cariogenic dental pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:14434-14439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banas, J. A., K. R. Hazlett, and J. E. Mazurkiewicz. 2001. An in vitro model for studying the contributions of the Streptococcus mutans glucan-binding protein A to biofilm structure. Methods Enzymol. 337:425-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biswas, I., L. Drake, and S. Biswas. 2007. Regulation of gbpC expression in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 189:6521-6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtiss, R., III. 1985. Genetic analysis of Streptococcus mutans virulence, p. 253-277. In W. Goebel (ed.), Current topics in microbial immunity. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.De Windt, W., H. Gao, W. Kromer, P. Van Damme, J. Dick, J. Mast, N. Boon, J. Zhou, and W. Verstraete. 2006. AggA is required for aggregation and increased biofilm formation of a hyper-aggregating mutant of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Microbiology 152:721-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drake, D., K. G. Taylor, A. S. Bleiweis, and R. J. Doyle. 1988. Specificity of the glucan-binding lectin of Streptococcus cricetus. Infect. Immun. 56:1864-1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrell, A., and B. Quilty. 2002. Substrate-dependent autoaggregation of Pseudomonas putida CP1 during the degradation of monochlorophenols and phenol. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 28:316-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felek, S., M. B. Lawrenz, and E. S. Krukonis. 2008. The Yersinia pestis autotransporter YapC mediates host cell binding, autoaggregation and biofilm formation. Microbiology 154:1802-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamada, S., and H. D. Slade. 1980. Biology, immunology, and cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol. Rev. 44:331-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han, T. K., and M. L. Dao. 2005. Differential immunogenicity of a DNA vaccine containing the Streptococcus mutans wall-associated protein A gene versus that containing a truncated derivative antigen A lacking in the hydrophobic carboxyterminal region. DNA Cell Biol. 24:574-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrington, D. J., and R. R. B. Russell. 1993. Multiple changes in cell wall antigens of isogenic mutants of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 175:5925-5933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart, E., J. Yang, M. Tauschek, M. Kelly, M. J. Wakefield, G. Frankel, E. L. Hartland, and R. M. Robins-Browne. 2008. RegA, an AraC-like protein, is a global transcriptional regulator that controls virulence gene expression in Citrobacter rodentium. Infect. Immun. 76:5247-5256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reference deleted.

- 15.Reference deleted.

- 16.Reference deleted.

- 17.Johnson, L. R. 2008. Microcolony and biofilm formation as a survival strategy for bacteria. J. Theor. Biol. 251:24-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirisits, M. J., L. Prost, M. Starkey, and M. R. Parsek. 2005. Characterization of colony morphology variants isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4809-4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeBlanc, D. J., L. N. Lee, and G. M. Dunny. 1991. A shuttle vector containing a polylinker region flanked by transcription terminators which replicates in Escherichia coli and in many gram-positive cocci, p. 306. In G. M. Dunny, P. P. Cleary, and L. L. McKay (ed.), Genetics and molecular biology of streptococci, lactococci, and enterococci. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 20.Loesche, W. J. 1986. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol. Rev. 50:353-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo, F., S. Lizano, S. Banik, H. Zhang, and D. E. Bessen. 2008. Role of Mga in group A streptococcal infection at the skin epithelium. Microb. Pathog. 45:217-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch, D. J., T. L. Fountain, J. E. Mazurkiewicz, and J. A. Banas. 2007. Glucan-binding proteins are essential for shaping Streptococcus mutans biofilm architecture. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 268:158-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macrina, F. L., C. L. Keeler, Jr., K. R. Jones, and P. H. Wood. 1980. Molecular characterization of unique deletion mutants of the streptococcal plasmid, pAMβ1. Plasmid 4:8-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merritt, J., J. Kreth, W. Shi, and F. Qi. 2005. LuxS controls bacteriocin production in Streptococcus mutans through a novel regulatory component. Mol. Microbiol. 57:960-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niu, G., T. Okinaga, L. Zhu, J. Banas, F. Qi, and J. Merritt. 2008. Characterization of irvR, a novel regulator of the irvA-dependent pathway required for genetic competence and dextran-dependent aggregation in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 190:7268-7274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reference deleted.

- 27.Sato, Y., Y. Yamamoto, and H. Kizaki. 1997. Cloning and sequence analysis of the gbpC gene encoding a novel glucan-binding protein of Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 65:668-675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato, Y., Y. Yamamoto, and H. Kizaki. 2000. Xylitol-induced elevated expression of the gbpC gene in a population of Streptococcus mutans cells. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 108:538-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato, Y., Y. Yamamoto, and H. Kizaki. 2000. Construction of region-specific partial duplication mutants (merodiploid mutants) to identify the regulatory gene for the glucan-binding protein C gene in vivo in Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 186:187-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steiner, K., and H. Malke. 1995. Transcription termination of the streptokinase gene of Streptococcus equisimilis H46A: bidirectionality and efficiency in homologous and heterologous hosts. Mol. Gen. Genet. 246:374-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsang, P., J. Merritt, W. Shi, and F. Qi. 2006. IrvA-dependent and IrvA-independent pathways for mutacin gene regulation in Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 261:231-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walter, J., C. Schwab, D. M. Loach, M. G. Ganzle, and G. W. Tannock. 2008. Glucosyltransferase A (GtfA) and inulosucrase (Inu) of Lactobacillus reuteri TMW1.106 contribute to cell aggregation, in vitro biofilm formation, and colonization of the mouse gastrointestinal tract. Microbiology 154:72-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]