Abstract

A fatty acyl coenzyme A synthetase (FadD) from Pseudomonas putida CA-3 is capable of activating a wide range of phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acids. It exhibits the highest rates of reaction and catalytic efficiency with long-chain aromatic and aliphatic substrates. FadD exhibits higher kcat and Km values for aromatic substrates than for the aliphatic equivalents (e.g., 15-phenylpentadecanoic acid versus pentadecanoic acid). FadD is inhibited noncompetitively by both acrylic acid and 2-bromooctanoic acid. The deletion of the fadD gene from P. putida CA-3 resulted in no detectable growth or polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) accumulation with 10-phenyldecanoic acid, decanoic acid, and longer-chain substrates. The results suggest that FadD is solely responsible for the activation of long-chain phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acids. While the CA-3ΔfadD mutant could grow on medium-chain substrates, a decrease in growth yield and PHA accumulation was observed. The PHA accumulated by CA-3ΔfadD contained a greater proportion of short-chain monomers than did wild-type PHA. Growth of CA-3ΔfadD was unaffected, but PHA accumulation decreased modestly with shorter-chain substrates. The complemented mutant regained 70% to 90% of the growth and PHA-accumulating ability of the wild-type strain depending on the substrate. The expression of an extra copy of fadD in P. putida CA-3 resulted in increased levels of PHA accumulation (up to 1.6-fold) and an increase in the incorporation of longer-monomer units into the PHA polymer.

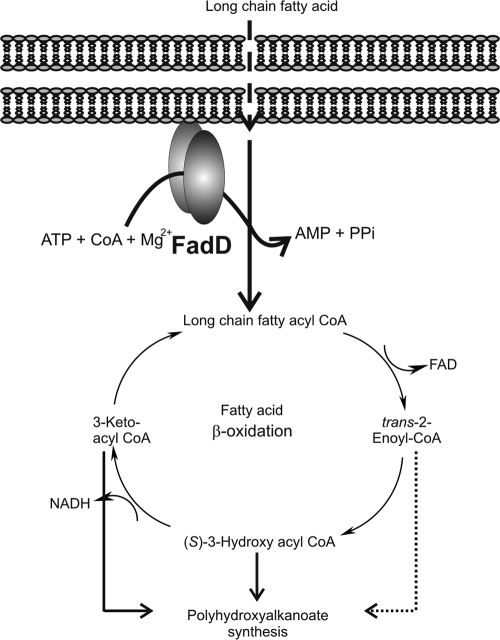

Fatty acyl coenzyme A (CoA) synthetases (FACS; fatty acid:CoA ligases; EC 6.2.1.3) are ATP-, CoA-, and Mg2+-dependent enzymes that activate alkanoic acids to CoA esters for β oxidation (Fig. 1 ) (2, 17). FACS are widely distributed in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms and exhibit a broad substrate specificity (34). FadD is a cytoplasmic membrane-associated FACS (7), with sizes ranging from 47 kDa to 62 kDa (2, 14). There is a lack of biochemical information on FadD with a preference for long-chain aromatic and aliphatic substrates. In the current study we purify and characterize for the first time a true long-chain FadD with activity toward both phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acids.

FIG. 1.

FadD activation of fatty acids to their CoA derivatives proceeds through ATP-dependent covalent binding of AMP to fatty acid with the release of inorganic pyrophosphate, followed by C-S bond formation to obtain fatty acyl-CoA ester and subsequent release of AMP. FadD requires the presence of Mg2+ ions to be active (2, 17).

It is known that bacteria such as Pseudomonas putida can accumulate the biological polyester polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) from aromatic as well as aliphatic alkanoic acids (5, 6, 42, 45). The presence of aromatic monomers in the PHA polymer suggests that a FadD with activity toward aromatic substrates is present in these PHA-accumulating strains. Garcia et al. knocked out an acyl-CoA synthetase in P. putida U with a high homology to long-chain fadD products from Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas fragi (6). Garcia et al. also showed that the mutant was not capable of growth or PHA accumulation with aromatic and aliphatic substrates having between 5 and 10 carbons in their acyl chain, indicating that it is a general and not a long-chain acyl-CoA ligase (6). In a follow-up study, Olivera et al. showed that the fadD mutants reverted to wild-type characteristics within 3 days of incubation, indicating that fadD could be replaced by the activity of a second enzyme (25). Indeed, two fadD gene homologues have been identified in P. putida U, namely, fadD1 and fadD2, with fadD2 being expressed only when fadD1 is inactivated (25). A putative FadD in P. putida KT2440 is encoded by PP_4549 (24), but the protein has not been studied nor has the effect of fadD (PP_4549) expression/disruption been examined. In the current study the knockout and complementation of fadD from P. putida CA-3 demonstrated that its activity is critical for growth and PHA accumulation with long-chain aromatic and aliphatic alkanoic acids and that the activity is not replaced by a second enzyme. While reports have shown that PHA polymerase greatly affects PHA monomer composition (30, 40), no evidence of the specific effect of FACS on PHA accumulation so far exists.

We describe here the purification, kinetic characterization, gene deletion, and homologous expression of FadD from P. putida CA-3. This is a fundamental study of the activity and physiological role of FACS activity in aromatic and aliphatic alkanoic acid activation and PHA accumulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

The phenylalkanoic acids 9-phenylnonanoic acid (C9Ph), 12-phenyldodecanoic acid (C12Ph), 15-phenylpentadecanoic acid (C15Ph), and 16-phenylhexadecanoic acid (C16Ph) were all purchased from Apollo Scientific (Stockport, Cheshire, United Kingdom); all other phenylalkanoic acids were purchased from Alfa-Aesar (Heysham, Lancaster, United Kingdom). Pentadecanoic acid was purchased from Alfa-Aesar (Heysham, Lancaster, United Kingdom); all other aliphatic alkanoic acids (C3 to C16) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Dublin, Ireland). Hydrochloric acid, sodium nitroprusside dihydrate, and ethylchloroformate were purchased from Sigma (Dublin, Ireland); methyl-3-hydroxyundecanoate and methyl-3-hydroxypentadecanoate were purchased from Larodan Fine Chemicals (Malmo, Sweden). Bio-X-ACT Long DNA polymerase was purchased from Bioline (London, England), the pGEM-T Easy vector system was purchased from Promega, and T4 DNA ligase was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Restriction enzymes NdeΙ, XhoΙ, NotΙ, BamHΙ, SmaI, and ClaI were obtained from Invitrogen (Paisley, United Kingdom). Bug Buster, mouse monoclonal antibody immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-His6, and goat anti-mouse IgG were all purchased from Merck Biosciences (United Kingdom). Oligonucleotide primers were obtained from Sigma Genosys (Dublin, Ireland). The QIAprep spin plasmid miniprep kit and Qiaex II gel purification kit were purchased from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany). All other chemicals were purchased at the highest purity from Sigma-Aldrich (Dublin, Ireland). The digoxigenin DNA labeling and detection kit and positively charged nylon membrane were purchased from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany).

Culture media and growth conditions.

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study are listed in Table 1 and Table 2. Pseudomonas strains were grown in MSM liquid medium (36) and were stored frozen at −80°C in MSM medium containing 15% (vol/vol) glycerol. E. coli strains used for protein expression studies were grown in shake flasks (250 ml) containing 50 ml of Luria-Bertani (LB) complex medium (35) at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm and supplemented with carbenicillin (50 μg ml−1).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics or purpose | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. putida | ||

| CA-3 | Wild-type strain, source of fadD gene | 29 |

| CA-3ΔfadD | P. putida CA-3 fadD deletion mutant, Gmr | This work |

| CA-3ΔfadD+fadD | P. putida CA-3 fadD deletion mutant expressing fadD copy from a pJB861-fadD plasmid, Kmr Gmr | This work |

| CA-3+fadD | P. putida CA-3 expressing extra copy of fadD from pJB861-fadD, Kmr | This work |

| CA-3+pJB | P. putida CA-3 carrying pJB861, control strain | This work |

| CA-3ΔfadD+pJB | P. putida CA-3 fadD deletion mutant carrying pJB861, control strain | This work |

| E. coli | ||

| XL1-Blue MRF′ | F−recA1 endA1 relA1 lac, cloning host | Stratagene |

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT, high-level expression of genes regulated by T7 promoter | Novagen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET22b | Expression under T7 promoter, C-terminal His tag, Ampr | Novagen |

| pET22b-fadD | 1.7-kbp fadD fragment from CA-3 in pET22b, Ampr | This work |

| pGEM-T Easy | Cloning of PCR products | Promega |

| pGEM-fadD2.4 | Plasmid containing 1.7-kb sequence of fadD flanked by 350 bp on each side | This work |

| pGEM-ΔfadD | Plasmid containing gentamicin cassette flanked by 55 bp from the beginning of fadD gene and 38 bp from the end of fadD gene from P. putida CA-3 | This work |

| pPS856 | Plasmid containing gentamicin cassette, Ampr Gmr | 14 |

| pJB861 | Broad host range, expression under Pm promoter, Kmr | 3, 4 |

| pJB861-fadD | 1.7-kb fadD fragment from P. putida CA-3 in pJB861, Kmr | This work |

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this studya

| Primerb | Sequence (5′ to 3′)c |

|---|---|

| FadD_NdeΙ_ (F) | GGAGCGCATATGATCGAAAATTTTTTGGAAGG |

| FadD_XhoΙ_ (R) | ATAGCTCTCGAGGGCGATCTTCTTCAAGCCTT |

| FadD_JB_NotΙ_ (F) | ATAGCTGCGGCCGCGATCGACAATTTTTGGAAGGAT |

| FadD_JB_BamHΙ_ (R) | ATAGCTGGATCCTCAGGCGATCTTCTTCAAGCC |

| FadD_external_seq (F) | CGATATAGCGTGATACCGGGATGG |

| FadD_external_seq (R) | GCATTGCCACCAGCCACATCA |

| FadD_ext_Up_inverse (R) | CCCGGGAAGCTTGGAATTCGTCAGGATTGATT |

| FadD_ext_Down_inverse (F) | CCCGGGAAGCTTTCGAACTGCGTGATGAAGA |

This work was the source for all primers.

seq, primer used for sequencing.

Underlining indicates SmaI restriction nuclease recognition site.

For the purpose of PHA accumulation experiments, MSM medium was used with the inorganic nitrogen source ammonium chloride supplied at a concentration of 0.25 g liter−1 (65 mg N liter−1). Except where otherwise stated, carbon substrates were included in the medium at a concentration of 2.28 g C liter−1. Bacterial cultures were grown for 48 h at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm. When appropriate, gentamicin (50 μg ml−1) and kanamycin (75 μg ml−1) were added to the medium for Pseudomonas deletion and complemented strains (Table 1). Carbon substrates were included in the medium at a concentration of 15 mmol liter−1. Pseudomonas deletion and complemented strains were grown for the appropriate length of time (2 to 7 days) depending on the growth substrate used with shaking at 200 rpm.

DNA techniques and plasmid construction.

All basic molecular biology techniques were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (35). Isolation of plasmid DNA from E. coli and Pseudomonas strains was carried out using a plasmid isolation procedure (Qiagen). Pseudomonas cells were made competent following a previously described procedure (3). Plasmids were transformed into electrocompetent E. coli and P. putida CA-3 cells using Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), using a 2-mm-gap-width electroporation cuvette and applying a pulse (settings: 25 μF, 200 Ω, and 2.5 kV). For the generation of pJB861-fadD plasmid (Table 1), E. coli XL1-Blue MRF electrocompetent cells were used as cloning hosts and transformed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene, Germany).

Genomic DNA was isolated from P. putida CA-3 by the method of Sambrook et al. (35). The primers FadD_NdeΙ_ (F) and FadD_XhoΙ_ (R) (Table 2) were designed based on the known fadD sequence of P. putida KT2440 and were used to amplify the fadD gene from P. putida CA-3. PCR was performed using a DNA Engine thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using the following parameters: 95°C for 2 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 2 min; and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The 1.7-kb fragment generated by PCR was digested with NdeΙ and XhoΙ and ligated into pET22b to generate pET22b_FadD for expression in E. coli (Table 1). Similarly, primers FadD_JB_NotΙ_ (F) and FadD_JB_BamHΙ_ (R) (Table 2) were used to amplify fadD for cloning into the broad-range expression vector pJB861 for expression in P. putida (Table 1). A control strain, CA-3+pJB, which contains a vector but no fadD gene inserted, was also included (Table 1). To verify plasmid constructs, DNA sequencing was conducted by GATC Biotech (Hamburg, Germany) using appropriate primers. Sequence data were aligned and compared to the GenBank database using the BLAST program (1).

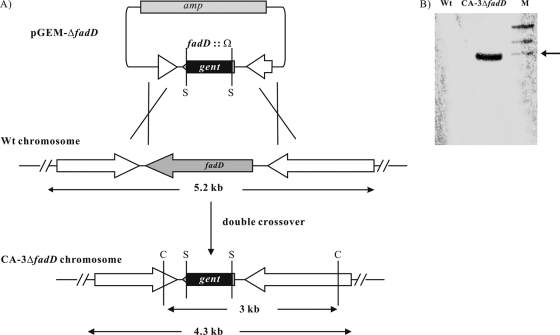

fadD gene deletion.

A 2.4-kb DNA fragment which contained the 1.7-kb sequence of fadD was amplified by PCR using genomic DNA of P. putida CA-3 as template and primers FadD_external_seq (F) and FadD_external_seq (R) (Table 2). PCR conditions consisted of one cycle of 95°C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 51°C for 40 s, 68°C for 1 min, and finally 68°C for 7 min. Purified PCR product was ligated into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), generating pGEM-fadD2.4 (Table 1).

Primers FadD_ext_Up_inverse (R) and FadD_ext_Down_inverse (F) (Table 2) were used to amplify a 4-kb DNA fragment using pGEM-fadD2.4 as template. PCR conditions consisted of one cycle of 95°C for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 40 s, 68°C for 4 min, and finally 68°C for 7 min. The PCR product obtained contained a SmaI restriction site flanked by 55 bp from the beginning of the fadD gene, the rest of the pGEM vector, 38 bp from the end of the fadD gene, and another SmaI restriction site. A 1,053-bp gentamicin resistance cassette was excised from the pPS856 plasmid by digestion with SmaI and ligated with the 4-kb PCR product to generate plasmid pGEM-ΔfadD (Table 2). Verification of all generated vectors was carried out by restriction digestion and sequencing (GATC Biotech, Hamburg, Germany) using appropriate primers.

Plasmid pGEM-ΔfadD was introduced into electrocompetent P. putida CA-3 by electroporation to generate the deletion mutant CA-3ΔfadD (Table 1). Gentamicin-resistant colonies were selected and verified by plasmid preparation, PCR, and Southern blot analysis.

Complementation of CA-3ΔfadD deletion mutant.

Complementation of CA-3ΔfadD was carried out using pJB861-fadD plasmid (Table 1). pJB861-fadD was introduced into CA-3ΔfadD by electroporation to generate CA-3ΔfadD+fadD. Selection of CA-3ΔfadD+fadD was carried out by screening for gentamicin and kanamycin resistance. An appropriate control strain (CA-3ΔfadD+pJB), which contains the expression vector without the fadD gene inserted, was also included in the study (Table 1).

Southern blot analysis.

Genomic DNA from the wild type and the deletion mutant was digested with ClaI and resolved in an 0.8% agarose (Tris-acetate-EDTA) gel for 1.5 h at 60 V. DNA was transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane using the Turboblotter Rapid Downward transfer system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Schleicher & Schuell, Inc.), and DNA was then UV cross-linked to the membrane. The gentamicin cassette was used as a hybridization probe and was digoxigenin labeled. The signal was detected using color substrate solution (nitroblue tetrazolium-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Creation of P. putida CA-3 fadD deletion mutant. (A) Experimental design; (B) Southern blot analysis of the deletion mutant. The arrow points to the 3-kb marker. S, SmaI restriction site; C, ClaI restriction site; Wt, wild type. Lane M, molecular size markers.

Overexpression of FadD in E. coli and subsequent purification.

Cultures were prepared for use in experiments by inoculation of cells from frozen stock culture onto agar plates and then subcultured into broth and incubated at the appropriate temperatures. Seed cultures of E. coli BL21(DE3) cells expressing FadD from pET22b were grown overnight at 37°C in 50-ml cultures of LB supplemented with carbenicillin (50 μg ml−1). These were then inoculated into a 5-liter fermentor (Electrolab Limited, Tewkesbury, England) (1% inoculum) and grown in LB supplemented with carbenicillin (50 μg ml−1) at 37°C, with a 5-liter min−1 airflow and an agitation speed maintained at 400 rpm (11). Once the culture had reached an optical density of 0.6 (600 nm; Helios Gamma UV-visible spectrophotometer [Thermo Scientific, Ireland]), the cells were induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) and further incubated for 10 to 14 h at 25°C. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C in a Sorvall RC5C Plus centrifuge (Unitech, Ireland). The cells (2 g [wet weight]) were lysed using Bug Buster (7 ml) (Merck Biosciences, United Kingdom) supplemented with 2 ml binding buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole), 25 μl protease inhibitor (Sigma), 10 μl benzonase nuclease (Sigma), and 1 to 2 mg of lysozyme (Sigma). After incubation with shaking at 30°C for 30 min, cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was filtered through 0.45-μm sterile filters (Sarstedt). The filtered supernatant (6 ml) was loaded onto a Ni-MAC cartridge (1 ml; Merck Biosciences, United Kingdom) using the Aktaprime protein purification system (GE Healthcare, United Kingdom) equilibrated with binding buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole) at 0.5 ml min−1. After loading, the column was washed with 6 volumes of the same binding buffer and then eluted with elution buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole) at 0.5 ml min−1 with an imidazole step gradient from 0% to 100%. All the purification steps were carried out at 4°C. The eluted protein was put through Amicon ultracentrifugal filter devices (50 kDa; Millipore, Ireland), to remove any smaller background bands and to concentrate the protein twofold. Charged amino acids l-arginine and l-glutamate (Sigma) at 50 mM were added to the eluted protein, to stabilize the protein, according to the method of Golovanov et al. (8).

Protein analysis.

The protein concentration was determined as previously described (38). Concentrated protein (4 mg ml−1) was separated on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel according to the protocol described by Laemmli (19). The proteins separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis were electroblotted onto an Immobilon-P transfer polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (0.45-μm pore size; Millipore, Ireland). The membranes were incubated first with IgG anti-His6 mouse monoclonal antibody as primary antibody and then with goat anti-mouse IgG as secondary antibody according to the manufacturer's instructions. The membranes were finally treated with an Immobilon Western chemiluminescent kit (Millipore, Ireland) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the protein bands were visualized using the FluorChemFC2 imager (Alpha Innotech Medical Supply, Dublin, Ireland).

In order to confirm protein identity, protein bands were cut from the SDS-polyacrylamide gel and the proteins were digested in gel with trypsin according to the method of Shevchenko et al. (37). In-house proteomics pipeline software (Proline) was used to process data. Briefly, spectra were searched using the X!Tandem algorithm (4) against the UniProt database restricted to P. putida entries (downloaded 7 January 2007). Only proteins (i) with an X!Tandem probability score greater than 0.99, (ii) identified by a minimum of two spectra, and (iii) from P. putida were accepted. Spectral counts were automatically calculated for each peptide using Proline.

Analysis of acyl-CoA synthetase activity.

Acyl-CoA synthetase activity was determined by measuring the rate of formation of the corresponding hydroxamate in the presence of ATP, CoA, substrate acid, and neutral hydroxylamine as previously described by Martinez-Blanco et al. (23). Phenylalkanoic or alkanoic acids (C3 to C16) were used as substrates. The reaction mixture contained 12.5 μl MgCl2 (0.2 M), 50 μl ATP (0.1 M), 30 μl CoA (20 mM), 30 μl substrate (ranging in concentration from 0.00075 to 0.25 mM), and 50 μl hydroxylamine solution (prepared as described below). Both ATP and CoA were dissolved in 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.2. After 5 min of temperature equilibration in a 30°C water bath, 100 μl of purified enzyme at a concentration of 4 mg ml−1 was added to the assay vial and incubated for 5 min. Five different control reaction mixtures were included in the study. One of the indicated components—ATP, CoA, MgCl2, or substrate—was omitted in the assay, and the assay mixture was incubated as described for test assays. Additionally, a control reaction mixture containing all components and heat-treated enzyme (75°C for 10 min) was also included. Reactions were stopped by adding 450 μl of the ferric chloride reagent (see below), and reaction mixtures were kept on ice for 30 min. The reaction mixtures were then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g in an Eppendorf 5415D microcentrifuge. The red-purple color formed was measured at 540 nm with a Helios Gamma UV-visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Ireland). The molar extinction coefficients of the corresponding fatty acyl-hydroxamate (phenylalkanoic or alkanoic acids, C3 to C16) were determined experimentally as described below (Table 3). One unit of enzyme activity is defined as the catalytic activity leading to the formation of 1 nmol of fatty acyl-hydroxamate in 1 min. Specific activity is given as unit/mg of protein. Neutral hydroxylamine solution, pH 8.0, was prepared by mixing 1 ml hydroxylamine hydrochloride (5 M), 250 μl Millipore water, and 1.25 ml of KOH (4 M). Ferric chloride reagent was prepared by mixing a 1:1:1 ratio of ferric chloride (0.37 M), trichloroacetic acid (0.02 M), and hydrochloride (0.66 M) (22).

TABLE 3.

Molar extinction coefficient values for aliphatic and aromatic compoundsa

| Aliphatic compound (acid) | ɛ value (mM−1 cm−1) | Aromatic compound (acid) | ɛ value (mM−1 cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propionic | 1.84 | 3-Ph propionic | 0.81 |

| Butyric | 1.55 | 4-Ph butyric | 0.78 |

| Valeric | 0.92 | 5-Ph valeric | 0.72 |

| Hexanoic | 2.65 | 6-Ph hexanoic | 0.58 |

| Heptanoic | 2.70 | 7-Ph heptanoic | 0.49 |

| Octanoic | 1.56 | 8-Ph octanoic | 0.46 |

| Nonanoic | 1.19 | 9-Ph nonanoic | 0.45 |

| Decanoic | 1.10 | 10-Ph decanoic | 0.42 |

| Undecanoic | 0.82 | 11-Ph undecanoic | 0.37 |

| Dodecanoic | 0.85 | 12-Ph dodecanoic | 0.36 |

| Myristic | 0.79 | ||

| Pentadecanoic | 0.72 | 15-Ph pentanoic | 0.36 |

| Palmitic | 0.42 | 16-Ph hexanoic | 0.34 |

Ph, phenyl. All data are the averages of at least three determinations.

Chemical synthesis of fatty acyl-CoA thioesters.

Fatty acyl-CoAs were synthesized as described previously by Stadtman (39) The phenylalkanoic or alkanoic acids were reacted with pyridine and ethylchloroformate to form the corresponding mixed anhydride. The anhydride was then reacted with free CoA to form the corresponding fatty acyl-CoA. The mixed anhydride was added to a 20 mM CoA solution, pH 7.5 (adjusted with 1 M KHCO3), until free CoA could no longer be detected by adding 5 μl of the solution to a strip of filter paper, which was then dipped in a sodium nitroprusside reagent (39), which reacts with free CoA to give a pink color. When the pink color could no longer be detected, all the free CoA was assumed to have reacted with the mixed anhydride to form the fatty acyl-CoA. This was confirmed by adding saturated NaOH solution (dissolved in methanol), which cleaves the thioester bond, causing free CoA to be released and the pink color to return.

Inhibition activity assays.

The inhibitory effect of acrylic acid and 2-bromooctanoic acid was determined by measuring acyl-CoA synthetase activity and the rate of formation of the corresponding hydroxamate in the presence of ATP, CoA, 8-phenyloctanoic acid or octanoic acid, neutral hydroxylamine, and either acrylic acid or 2-bromooctanoic acid. The reaction mixture contained 12.5 μl MgCl2 (0.2 M), 50 μl ATP (0.1 M), 30 μl CoA (20 mM), 30 μl substrate (8-phenyloctanoic acid or octanoic acid [0.25 mM]), 50 μl hydroxylamine solution (as described above [“Analysis of acyl-CoA synthetase activity”]), and either acrylic acid or 2-bromooctanoic acid (ranging in concentration from 0.00125 to 2 mM) for initial inhibitory assays. Assay mixtures for the determination of the type of inhibition exhibited by acrylic acid and 2-bromooctanoic acid contained a fixed concentration of 0.0025 mM of the inhibitor with substrate concentrations varying between 0.00075 and 0.25 mM. Both ATP and CoA were dissolved in 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.2. After 5 min of temperature equilibration in a 30°C water bath, 100 μl of purified enzyme at a concentration of 4 mg ml−1 was added to the assay vial and incubated for 5 min. Reactions were stopped by adding 450 μl of the ferric chloride reagent (as previously described), and reaction mixtures were kept on ice for 30 min (23). The reaction mixtures were then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g in an Eppendorf 5415D microcentrifuge. The red-purple color formed was measured at 540 nm with a Helios Gamma UV-visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Ireland). Control experiments were carried out in the absence of acrylic acid and 2-bromooctanoic acid.

PHA content and monomer determination from bacterial cultures.

After 48 h of incubation at 30°C, P. putida CA-3 cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,500 × g for 20 min at 4°C in a bench top 5810R centrifuge (Eppendorf). For PHA analysis of the fadD deletion mutant, the strains were left for the appropriate length of time depending on the growth substrate used. The pellet was washed twice with 1 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and freeze-dried.

To determine the polymer content of the lyophilized whole cells, approximately 5 to 10 mg of the cells was subjected to acidic methanolysis according to previously described protocols (20). This method degrades the intracellular PHA to the methyl ester of its constituent 3-hydroxyalkanoic acid monomers. Cell material (5 to 10 mg) or PHA standard was resuspended in 2 ml acidified methanol (15% [vol/vol] H2SO4) and 2 ml of chloroform containing 6 mg liter−1 benzoate methyl ester as an internal standard. The mixture was placed in 15-ml Pyrex test tubes and incubated at 100°C for 3 h (with frequent inversions). The solution was extracted with 1 ml of water (vigorous vortexing for 2 min). The phases were allowed to separate before the top layer (water) was removed. The organic phase (bottom layer) was removed into a new vial for analysis.

The samples were analyzed on an Agilent 6890N series gas chromatograph fitted with a 30-m by 0.25-mm by 0.25-μm HP-1 column (Hewlett-Packard) using a split mode (split ratio, 10:1). The oven method employed was 120°C for 5 min, with the temperature increasing by 3°C/min to 180°C and being held for 25 min, followed by an increase of 10°C/min to 220°C and being held for 2 min. For peak identification, the following standards were used: (R)-3-hydroxyhexanoic acid, (R)-3-hydroxyoctanoic acid, (R)-3-hydroxydecanoic acid, (R)-3-hydroxydodecanoic acid, (R)-3-hydroxymyristic acid, (R)-3-hydroxypalmitic acid, methyl-3-hydroxyundecanoate, and methyl-3-hydroxypentadecanoate. PHA monomer determination was confirmed using an Agilent 6890N gas chromatograph fitted with a 5973 series inert mass spectrophotometer; an HP-1 column (12 m × 0.2 mm × 0.33 μm) (Hewlett-Packard) was used with an oven method of 50°C for 3 min with the temperature increasing by 10°C/min to 250°C and being held for 1 min.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

Sequencing data obtained for the P. putida CA-3 fadD gene were submitted under the GenBank accession number EU605979.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequencing of the fadD gene from P. putida CA-3.

The DNA sequence (1,698 bp) of the P. putida CA-3 fadD gene was submitted to GenBank (accession number EU605979). DNA sequence analysis showed 99% homology between the fadD genes of P. putida CA-3 and P. putida KT2440 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Purification of FadD and characterization of its biochemical properties.

The fadD gene from P. putida CA-3 was expressed in pET22b under the control of the T7 promoter in E. coli BL21(DE3) (Table 1). The recombinant FadD protein had a C-terminal tag consisting of six consecutive histidines. The His-tagged FadD was purified to homogeneity by affinity chromatography using a nickel-chelating column (Merck Biosciences, United Kingdom). A protein product of approximately 62 kDa was observed on a denaturing SDS-polyacrylamide gel (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). This is in agreement with the molecular mass of FadD deduced from its amino acid sequence (62 kDa). The molecular mass was also verified by Western blot analysis using an IgG anti-His6 antibody (Merck Biosciences, United Kingdom) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), and protein identification was confirmed by mass spectrometry analysis.

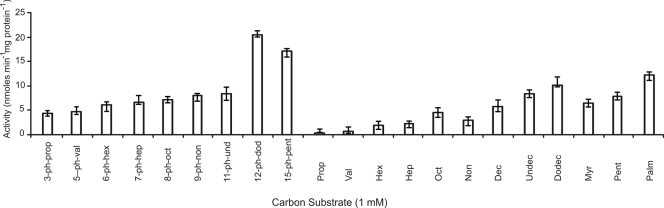

In order to quantify FadD activity, the molar extinction coefficient of the CoA esters of each phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acid had to be determined experimentally (Table 3). Following the determination of the molar extinction coefficient values, the substrate range of purified FadD (4 mg ml−1) was investigated using both phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acids. FadD from P. putida CA-3 showed activity toward long-, medium-, and short-chain phenylalkanoic and alkanoic substrates (Fig. 3). The protein exhibited a gradual increase in activity with increasing side chain length of the phenylalkanoic substrate (C3Ph to C11Ph) (Fig. 3). A more dramatic 2.4-fold increase in activity was observed when 12-phenyldodecanoic acid was used as a substrate in comparison to 11-phenylundecanoic acid. FadD exhibited a 1.25-fold-lower rate of activity with 15-phenylpentadecanoic acid than with 12-phenyldodecanoic acid (Fig. 3). In general FadD also exhibited an increase in activity with increasing chain length of the aliphatic substrates. The highest activity was observed with palmitic acid (C16) as a substrate (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

P. putida CA-3 FACS activity toward a range of phenylalkanoic and alkanoic substrates (1 mM). All data are the averages of at least three independent determinations.

Representative substrates were chosen for kinetic characterization of FadD from P. putida CA-3 (Table 4). Higher kcat values were observed for substrates with a longer carbon chain than for those with a short carbon chain (Table 4). FadD exhibited similar kcat values for the long-chain aromatic and aliphatic substrates such as 12-phenyldodecanoic (C12Ph), 15-phenylpentadecanoic (C15Ph), and palmitic (C16) acids (Table 4). Interestingly, the kcat values for phenylalkanoic acids such as C15Ph, C8Ph, and C5Ph were higher than those for the aliphatic equivalents (Table 4). FadD exhibited the lowest Km value when incubated with octanoic acid, while the highest Km value was observed with C5Ph acid as a substrate (Table 4). The Km values for aromatic substrates were higher than those for the aliphatic substrates (Table 4). In general, the catalytic efficiency of FadD was higher with long-chain aromatic and aliphatic alkanoic acids than with substrates with shorter carbon chains (Table 4). FadD exhibited similarly high catalytic efficiency values with the long-chain aromatic and aliphatic acids, i.e., C12Ph, C15Ph, C15, and C16 (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Kinetic rates for FACS activity from P. putida CA-3 for a range of phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acidsa

| Acid substrate | Value for FadD from P. putida CA-3 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (min−1) (mean ± SD) | Km (mM) (mean ± SD) | kcat/Km (min−1/mM−1) | |

| 5-Ph valeric | 24 ± 1 | 84 ± 2 | 286 |

| 8-Ph octanoic | 42 ± 1 | 79 ± 1 | 532 |

| 12-Ph dodecanoic | 112 ± 3 | 55 ± 1 | 2,036 |

| 15-Ph pentadecanoic | 108 ± 2 | 66 ± 2 | 1,636 |

| Valeric | 3 ± 1 | 32 ± 1 | 94 |

| Octanoic | 25 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 | 962 |

| Nonanoic | 15 ± 1 | 35 ± 2 | 429 |

| Myristic | 52 ± 2 | 46 ± 1 | 1,130 |

| Pentadecanoic | 61 ± 1 | 32 ± 1 | 1,906 |

| Palmitic | 124 ± 3 | 62 ± 2 | 2000 |

Ph, phenyl. All data are the averages of at least three determinations. All data have been rounded to the nearest whole number.

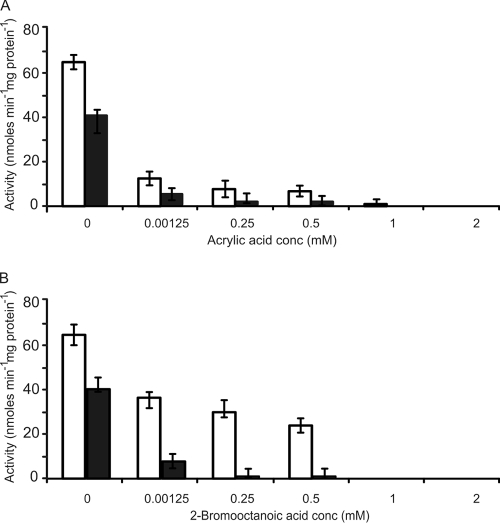

The effect of acrylic acid and 2-bromooctanoic acid on FadD activity.

Acrylic acid and 2-bromooctanoic acid have previously been reported to act as enzyme inhibitors in whole-cell assays (12, 21, 42). Acyl-CoA synthetase and 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthetase (3-ketothiolase I) are both inhibited by acrylic acid in β oxidation, while (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP)-CoA transferase is inhibited by 2-bromooctanoic acid in fatty acid synthesis (21, 28, 29, 42). To date, these compounds have not been tested as inhibitors of FadD enzyme activity. The structural similarities of 2-bromooctanoic acid and acrylic acid to alkanoic acids make them interesting molecules for FadD inhibition studies. In the present study we observed that both acrylic acid (1 to 2 mM) and 2-bromooctanoic acid (1 to 2 mM) inhibited the activity of FadD with a range of phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acids (C3 to C16 and C5Ph to C15Ph). 8-Phenyloctanoic acid and octanoic acid were chosen as representative substrates (Fig. 4A and B).

FIG. 4.

The inhibitory effects of acrylic acid (A) and 2-bromooctanoic acid (B) on FACS activity from P. putida CA-3 using either 8-phenyloctanoic acid (open bars) or octanoic acid (solid bars) as substrate (0.25 mM). All data are the averages of at least three independent determinations.

Acrylic acid (1.25 μM) caused a five- and a ninefold decrease in activity for FadD with 8-phenyloctanoic acid and octanoic acid, respectively (Fig. 4A). Increasing the concentration of acrylic acid 200-fold to 0.25 mM did not result in total inhibition of FadD activity. Increasing the concentration of acrylic acid to 1.0 mM completely inhibited FadD activity toward 8-phenyloctanoic acid (Fig. 4A). However, a twofold-higher concentration of acrylic acid was needed to completely inhibit FadD activity with octanoic acid (Fig. 4A).

2-Bromooctanoic acid exhibited strong inhibition of enzyme activity toward octanoic acid at 1.25 μM but was less effective at inhibiting FadD activity with 8-phenyloctanoic acid at inhibitor concentrations up to 0.5 mM (Fig. 4B). A dramatic increase in inhibition was observed when the concentration of 2-bromoctanoic acid was increased to 1 mM. Indeed, the complete inhibition of FadD with 8-phenyloctanoic acid and octanoic acid was observed at 1 mM 2-bromooctanoic acid (Fig. 4B).

Analysis of Lineweaver-Burk plots (1/V versus 1/S) revealed that both acrylic acid and 2-bromooctanoic acid are noncompetitive inhibitors of FadD, i.e., a reduction in Vmax values, without a change in the binding affinity (Km) of the enzyme for the substrate, was observed (see Fig. S3A and B in the supplemental material).

Thus far, this study has established that a single enzyme, FadD, is capable of activating both aromatic and aliphatic alkanoic acids with markedly higher activity toward long-chain substrates than toward medium- and short-chain substrates. Whether FadD in P. putida CA-3 is the only FACS capable of activating long-chain aromatic and aliphatic alkanoic acids was investigated through the creation of a gene-specific deletion mutant (CA-3ΔfadD). The creation of the mutant allowed us to define exactly the role of FadD in phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acid metabolism as well as its effect on accumulation of the biological polymer PHA.

The effect of fadD gene deletion in P. putida CA-3 on growth and PHA accumulation.

The gene encoding the FACS FadD was specifically deleted from the genome of P. putida CA-3, creating the mutant CA-3ΔfadD. Specific deletion was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 2A). The expected ClaI fragment containing the gentamicin cassette from CA-3ΔfadD was 3 kb in size (Fig. 2B). Complementation of the CA-3ΔfadD deletion mutant was performed by expressing fadD on pJB861 to create the strain CA-3ΔfadD+fadD (Table 1). The deletion mutant, complemented mutant, and the wild-type strain P. putida CA-3 were supplied with a range of phenylalkanoic acids (C3Ph to C12Ph) and alkanoic acids (C3 to C16) and tested for growth and PHA accumulation.

Long-chain phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acid substrates.

The deletion mutant CA-3ΔfadD failed to grow despite extended incubation (7 days) when supplied with 10-phenyldecanoic acid and 12-phenyldodecanoic acid (Table 5). Similar results were observed with aliphatic substrates, i.e., decanoic acid (C10) to palmitic acid (C16) (Table 6). Since the fadD deletion mutant cannot grow when supplied with long-chain aromatic and aliphatic substrates, it was supplied with glucose as a carbon and energy source to allow good growth and also supplied with a long-chain phenylalkanoic acid (C12Ph) and an alkanoic acid (C12) as selected substrates for PHA accumulation (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). CA-3ΔfadD accumulated PHA with aliphatic monomers only and failed to accumulate any aromatic monomers when grown with glucose and 12-phenyldodecanoic acid (see Fig. S4 and Table S1 in the supplemental material). The wild-type strain grown under the same conditions accumulated PHA with both aliphatic and aromatic monomers (see Fig. S4 and Table S1 in the supplemental material). The deletion mutant also failed to accumulate the long-chain monomer unit (R)-3-hydroxytetradecanoic acid, observed in the wild type, when grown on glucose and supplemented with dodecanoic acid (see Fig. S4A and Table S1 in the supplemental material). The wild-type strain also accumulated PHA with a higher percentage of the long-chain monomer unit (R)-3-hydroxydodecanoic acid in comparison to the levels produced by the deletion mutant (see Fig. S4B and Table S1 in the supplemental material). Thus, FadD is essential for the metabolism and activation of long-chain phenylalkanoic acids and alkanoic acids for PHA accumulation in P. putida CA-3. The complemented mutant expressing fadD from P. putida CA-3 on a plasmid (pJB861-fadD) regained its ability to grow on long-chain phenylalkanoic acids (C10Ph and C12Ph) and alkanoic acids (C10 to C16). The complemented mutant (CA-3ΔfadD+fadD) regained 70% to 90% of the growth and PHA-accumulating capacity of the wild-type strain depending on the substrate (Tables 5 and 6). The control mutant strain carrying the pJB861 plasmid without the fadD gene failed to grow on long-chain aromatic (C10Ph and C12Ph) and aliphatic (C10 to C16) alkanoic acids. The control strain grew and accumulated PHA in a manner similar to that of the knockout mutant with medium-chain phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acid substrates (C6 to C9 and C7Ph to C9Ph; data not shown).

TABLE 5.

Biomasses and percentages PHA accumulated for P. putida CA-3, CA-3ΔfadD, CA-3ΔfadD+fadD, and CA-3+fadD grown on a range of phenylalkanoic acidsd

| Aromatic compound | CA-3 |

CA-3ΔfadD |

CA-3ΔfadD+fadD |

CA-3+fadD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass, g liter−1 | % PHA | Biomass, g liter−1 | % PHA | Biomass, g liter−1 | % PHA | Biomass, g liter−1 | % PHA | |

| 12-Ph dodecanoic | 1.48a ± 0.04 | 52 ± 1 | NG | 0 | 1.32c ± 0.05 | 36 ± 1 | 1.76a ± 0.05 | 64 ± 2 |

| 10-Ph decanoic | 1.50a ± 0.02 | 42 ± 1 | NG | 0 | 1.21c ± 0.03 | 26 ± 1 | 1.62a ± 0.04 | 45 ± 1 |

| 9-Ph nonanoic | 1.49a ± 0.05 | 39 ± 1 | 0.85b ± 0.02 | 12 ± 0.5 | 1.17c ± 0.02 | 25 ± 2 | 1.64a ± 0.03 | 44 ± 1 |

| 8-Ph octanoic | 1.32a ± 0.03 | 35 ± 2 | 1.03b ± 0.04 | 11 ± 0.2 | 0.97c ± 0.02 | 22 ± 1 | 1.45a ± 0.03 | 39 ± 1 |

| 7-Ph heptanoic | 0.93a ± 0.04 | 30 ± 1 | 0.76b ± 0.02 | 12 ± 0.4 | 0.65c ± 0.02 | 19 ± 1 | 0.96a ± 0.02 | 33 ± 2 |

| 6-Ph hexanoic | 0.84a ± 0.03 | 26 ± 1 | 0.87a ± 0.03 | 18 ± 0.5 | 0.56c ± 0.01 | 16 ± 0.5 | 0.88a ± 0.03 | 28 ± 1 |

| 5-Ph valeric | 0.80a ± 0.02 | 18 ± 2 | 0.80a ± 0.02 | 14 ± 0.3 | 0.78c ± 0.01 | 17 ± 0.5 | 0.91a ± 0.02 | 22 ± 2 |

Time allowed for growth, 48 h.

Time allowed for growth, 7 days (168 h).

Time allowed for growth, 88 h.

Ph, phenyl; NG, no growth. All data are means ± standard deviations and are the averages of at least three determinations. All PHA data have been rounded to the nearest whole number.

TABLE 6.

Biomasses and percentages PHA accumulated for P. putida CA-3, CA-3ΔfadD, CA-3ΔfadD+fadD, and CA-3+fadD grown on a range of aliphatic acidsd

| Aliphatic compound | CA-3 |

CA-3ΔfadD |

CA-3ΔfadD+fadD |

CA-3+fadD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass, g liter−1 | % PHA | Biomass, g liter−1 | % PHA | Biomass, g liter−1 | % PHA | Biomass, g liter−1 | % PHA | |

| Palmitic | 2.27a ± 0.1 | 26 ± 1 | NG | 0 | 1.81c ± 0.05 | 18 ± 0.4 | 2.25a ± 0.07 | 27 ± 0.5 |

| Myristic | 1.73a ± 0.1 | 37 ± 1 | NG | 0 | 1.34c ± 0.05 | 24 ± 0.2 | 1.81a ± 0.07 | 32 ± 0.5 |

| Dodecanoic | 1.69a ± 0.05 | 37 ± 1 | NG | 0 | 1.29c ± 0.04 | 24 ± 0.2 | 1.78a ± 0.06 | 46 ± 1 |

| Decanoic | 1.8a ± 0.04 | 32 ± 2 | NG | 0 | 1.31c ± 0.02 | 20 ± 0.6 | 1.89a ± 0.05 | 34 ± 1 |

| Nonanoic | 1.79a ±0.03 | 31 ± 2 | 0.49b ± 0.02 | 8 ± 0.1 | 0.78c ± 0.02 | 20 ± 0.2 | 1.92a ± 0.05 | 34 ± 1 |

| Octanoic | 1.59a ±0.04 | 32 ± 1 | 1.03b ± 0.04 | 11 ± 0.1 | 1.26c ± 0.03 | 25 ± 0.2 | 1.88a ± 0.04 | 36 ± 1 |

| Heptanoic | 1.01a ± 0.04 | 20 ± 1 | 0.66b ± 0.02 | 10.5 ± 0.2 | 0.64c ± 0.01 | 12 ± 0.3 | ND | ND |

| Hexanoic | 0.91a ± 0.03 | 22 ± 1 | 0.56b ± 0.01 | 12 ± 0.3 | 0.60c ± 0.01 | 13 ± 0.3 | ND | ND |

| Valeric | 0.84a ± 0.02 | 19 ± 0.4 | 0.88a ± 0.01 | 13.5 ± 0.04 | 0.75c ± 0.02 | 16 ± 0.4 | ND | ND |

| Butyric | 0.77a ± 0.02 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 0.73a ± 0.02 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 0.62c ± 0.01 | 6 ± 0.1 | ND | ND |

| Propionic | 0.73a ± 0.02 | 6 ± 0.1 | 0.71a ± 0.02 | 3.5 ± 0.07 | 0.59c ± 0.01 | 5 ± 0.1 | ND | ND |

Time allowed for growth, 48 h.

Time allowed for growth, 7 days.

Time allowed for growth, 88 h.

NG, no growth; ND, not determined. All data are means ± standard deviations and are the averages of at least three determinations. All PHA data have been rounded to the nearest whole number.

When the deletion mutant CA-3ΔfadD was grown on medium-chain phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acids (C7Ph to C9Ph and C6 to C9), there was a longer lag period before growth entered the log phase. The mutant required 7 days to achieve approximately 60% of the biomass of the wild type (2 days). The biomass yield of the deletion mutant (total cell material minus PHA) decreased by 1.2- to 1.8-fold for phenylalkanoic acids and 1.5- to 3.8-fold for alkanoic acids in comparison to the wild type (Tables 5 and 6). The complemented mutant achieved a 1.4- and 1.6-fold-higher growth yield than did the deletion mutant when supplied with 9-phenylnonanoic acid and nonanoic acid, respectively (Tables 5 and 6). The deletion of fadD also resulted in a decreased growth yield of P. putida CA-3 when 7-phenylheptanoic acid, 8-phenyloctanoic acid, and aliphatic substrates hexanoic acid to octanoic acid were supplied as growth substrates. However, the complemented mutant did not achieve a higher biomass than did the mutant strain when supplied with any aromatic substrate with an acyl chain of eight carbons or fewer (Table 5) or an aliphatic substrate with seven carbons or fewer (Table 6).

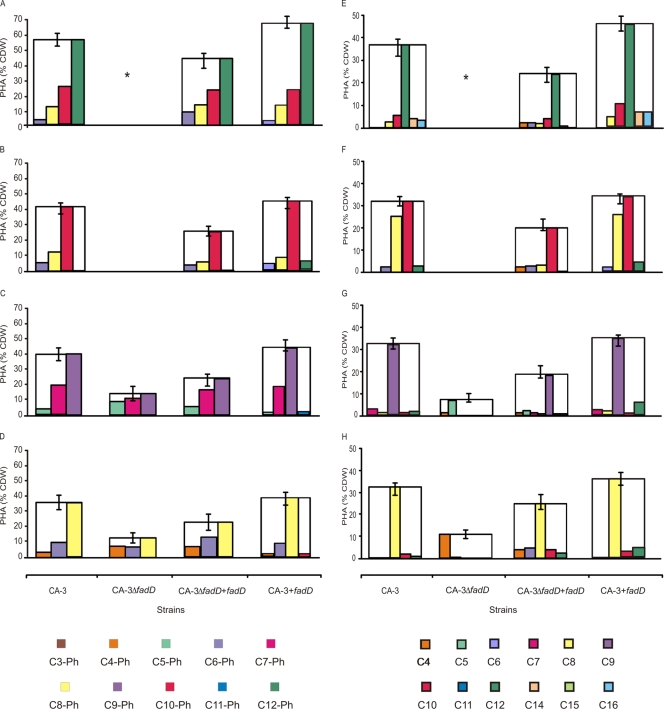

CA-3ΔfadD supplied with medium-chain-length substrates (C7Ph to C8Ph and C7 to C9) accumulated 3.9- to 2.5-fold less PHA than did the wild-type strain (Table 5). When medium-chain-length phenylalkanoic acids were supplied to CA-3ΔfadD, an increase in the proportion of shorter-chain aromatic monomers was detected. For example, a 5.2-fold increase and a 1.2-fold increase in the percentage of (R)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylvaleric acid and (R)-3-hydroxy-7-phenylheptanoic acid monomer units were observed when 9-phenylnonanoic acid was used as a substrate in comparison to the levels produced by the wild type (Fig. 5C).

FIG. 5.

PHA accumulation and monomer distribution for P. putida CA-3, deletion mutant (CA-3ΔfadD), complemented deletion mutant (CA-3ΔfadD+fadD), and P. putida CA-3 carrying an extra copy of the fadD gene (CA-3+fadD) grown on a range of phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acids: 12-phenyldodecanoic acid (A), 10-phenyldecanoic acid (B), 9-phenylnonanoic acid (C), 8-phenyloctanoic acid (D), dodecanoic acid (E), decanoic acid (F), nonanoic acid (G), and octanoic acid (H). C4, (R)-3-hydroxybutyric acid, etc.; C3Ph, (R)-3-hydroxy-3-phenylpropionoic acid, etc.; *, cells grown on glucose and supplemented with either 12-phenyldodecanoic acid or dodecanoic acid for PHA accumulation (see Fig. S4 and Table S1 in the supplemental material). All data are the averages of at least three independent determinations.

The complemented mutant (CA-3ΔfadD+fadD) accumulated 1.6- to 2-fold-more PHA than did the deletion mutant when supplied with C7Ph to C9Ph. The PHA accumulated by the complemented mutant contained proportionally more medium-chain monomers than did that accumulated by the deletion mutant but fewer than that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 5C and D). CA-3ΔfadD+fadD exhibited 2.3-fold and 2.4-fold increases in PHA accumulation levels with C8 and C9 as substrates compared to the mutant strain (Table 6).

Short-chain phenylalkanoic acid and alkanoic acid substrates.

The growth of CA-3ΔfadD was unaffected when short-chain aromatic (C5Ph and C6Ph) and aliphatic (C5 to C3) acids were supplied as substrates. PHA accumulation by the deletion mutant CA-3ΔfadD was affected 1.2- to 1.4-fold with these short-chain substrates (Tables 5 and 6; Fig. 5).

While the purified enzyme FadD has a broad substrate range, activating long-, medium-, and short-chain aromatic and aliphatic substrates (Fig. 3), its physiological role is critical only for the activation of long-chain aromatic and aliphatic substrates.

The effect of expression of fadD in P. putida CA-3 on PHA accumulation and monomer composition.

As the deletion of fadD resulted in a decrease in the level of PHA and the appearance of shorter-chain monomers, the expression of an extra copy of fadD in the wild-type strain was undertaken to determine if an increase in PHA accumulation levels and the proportion of long-chain monomers could be achieved.

A recombinant strain of P. putida CA-3 expressing an extra copy of fadD was constructed (Table 1). The wild type and the recombinant strain (CA-3+fadD) were grown on a range of phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acids to determine growth yields, PHA accumulation, and monomer composition levels.

Phenylalkanoic acids.

In general the expression of an extra copy of FadD (CA-3+fadD) results in a modest increase (1.1- to 1.3-fold) in PHA accumulation when phenylalkanoic acids are supplied (Table 5). This effect was not observed in the control strain P. putida CA-3 carrying pJB861 without a fadD gene. PHA accumulated by the wild type and the recombinant strain (CA-3+fadD) from phenylalkanoic acids was composed predominantly of monomer units equal in length to the carbon substrate supplied, e.g., (R)-3-hydroxy-10-phenyldecanoic acid was the predominant monomer in strains supplied with 10-phenyldecanoic acid. However, PHA accumulated by the recombinant strain (CA-3+fadD) also contained monomers two carbons longer than the predominant monomer. This was not observed in the wild-type or control strain expressing pJB861 without the fadD gene (Fig. 5A to D).

Alkanoic acids.

The expression of an extra copy of FadD also resulted in a modest increase (up to 1.3-fold) in PHA accumulation when alkanoic acids were supplied (Table 6). The recombinant (CA-3+fadD) and wild-type strains accumulated PHA with the predominant monomer equal in chain length to the carbon substrate supplied in the range of C8 to C10 (Fig. 5E and F). This was not observed in the control strain expressing the pJB861 vector without the fadD gene. The overexpression of FadD resulted in an increase in (R)-3-hydroxydodecanoic acid monomer when supplied with C8 to C10 (Fig. 5F to H). An increase in the proportion of (R)-3-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid was observed in the recombinant strain (CA-3+fadD) when dodecanoic acid was used as a carbon source (Fig. 5E).

The predominant monomer in PHA accumulation from myristic and palmitic acid was (R)-3-hydroxyoctanoic acid (data not shown). The recombinant strain (CA-3+fadD) accumulated higher proportions of (R)-3-hydroxydodecanoic acid, (R)-3-hydroxytetradecanoic acid, and (R)-3-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid than did wild-type strains when supplied with myristic acid and palmitic acid (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

FadD activity toward aromatic and aliphatic alkanoic acids.

We have shown for the first time that a single enzyme, FadD, is capable of activating both aromatic and aliphatic alkanoic acids. While FadD exhibited activity toward a range of phenylalkanoic acids, it showed a higher activity toward the longer-chain substrates, i.e., C12Ph and C15Ph (Fig. 3). Interestingly, FadD exhibited higher activity for C12Ph and C15Ph than for the aliphatic equivalents (Fig. 3). Thus, the aromatic substituent appears to positively affect the rate of enzyme activity, while the turnover number (kcat) of FadD increases with increasing chain length of the phenylalkanoic acid substrate. However, the Km value of FadD was in general higher for aromatic substrates than for aliphatic substrates, suggesting that the aromatic ring decreases the affinity of FadD for that substrate (Table 4). For aromatic substrates, it is possible only to compare the enzyme activity of FadD from P. putida CA-3 to one other source, namely, a short-chain acyl-CoA synthetase from Pseudomonas chlororaphis B23 (9). P. putida CA-3 FadD exhibited a 13-fold-higher rate of reaction with 3-phenylpropionic acid than with propionic acid (Fig. 3). In contrast, the short-chain acyl-CoA synthetase from P. chlororaphis B23 showed a 2,952-fold-lower activity with 3-phenylpropionic acid (4.2 nmol min−1 mg protein−1) than with its aliphatic equivalent propionic acid (9). Purified acyl-CoA synthetase from E. coli exhibited maximum activity toward dodecanoic acid (2,632 nmol min−1 mg protein−1) (14). However, FadD from P. putida CA-3 exhibited the highest activity values with C12Ph, C15, and C16 acids, respectively (Table 4). FadD from P. putida CA-3 had Km values similar to that reported in the literature for acyl-CoA synthetases from E. coli acting on aliphatic substrates from C6 to C9 but higher Km values for aliphatic substrates ranging from C14 to C16 (14).

The effect of inhibitors on the activity of FadD.

Acrylic acid was previously shown to inhibit the first and last enzymes of β oxidation, namely, acyl-CoA synthetase (FadD) and 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthetase (FadA), in whole-cell assays (12, 28). 2-Bromooctanoic acid has been reported to inhibit the fatty acid synthesis enzyme (R)-3-hydroxyacyl-ACP-CoA transferase (PhaG) and the β-oxidation enzyme 3-ketothiolase I (21, 29, 42). As β-oxidation and fatty acid synthesis pathways are providing intermediates for the PHA synthesis, both of these inhibitors have been extensively used in attempts to modulate PHA accumulation levels (26, 33). In general, when used in whole-cell assays at concentrations of 4 to 5 mM, acrylic acid causes either complete inhibition or considerably decreased levels of PHA accumulation from alkanoic and phenylalkanoic acid substrates (12, 21, 42). 2-Bromooctanoic acid caused a 20% decrease in cell dry weight and PHA accumulation when P. fluorescens BM07 was grown on alkanoic and phenylalkanoic acid substrates (21).

We have shown for the first time that acrylic acid is an inhibitor of the purified enzyme FadD from P. putida CA-3. Thijsse put forward the presumption that the possible mechanism of inhibition of acrylic acid with acyl-CoA synthetase and 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthetase is via an interaction of the double bond of acrylic acid with CoASH (41). There have been no studies of the inhibitory effect of 2-bromooctanoic acid on purified FACS. Raaka and Lowenstein proposed that 2-bromooctanoic acid is converted to 2-bromooctanoyl-CoA and 2-bromo-3-ketooctanoyl-CoA in rat liver mitochondria and that this 2-bromo-3-ketooctanoyl-CoA is the specific inhibitor of the enzyme 3-ketothiolase I (21, 29). It was suggested by Lee et al. that acyl-ACP-CoA transferase (PhaG) is also inhibited by 2-bromo-3-ketooctanoyl-CoA (21). FadD from P. putida CA-3 may also be inhibited by 2-bromooctanoyl-CoA formed by the action of FadD on 2-bromooctanoic acid. In support of this possibility, a low level of activity for FadD toward 2-bromooctanoic acid was observed when 2-bromooctanoic acid was incubated with FadD from P. putida CA-3 (data not shown). Kasuya et al. reported that purified medium-chain acyl-CoA synthetase from bovine liver mitochondria was inhibited by 2-hydroxyoctanoic acid (Ki, 500 μM) when hexanoic acid was used as a substrate (15). In comparison to 2-hydroxyoctanoic acid and other inhibitors, both acrylic acid and 2-bromooctanoic acid are more potent (15, 16). Kasuya et al. demonstrated that 2-hydroxyoctanoic acid is a competitive inhibitor of mitochondrial medium-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (15). However, acrylic acid and 2-bromooctanoic acid are noncompetitive inhibitors of FadD from P. putida CA-3 with both 8-phenyloctanoic acid and octanoic acid as substrates.

The effect of fadD gene deletion on growth and PHA accumulation. (i) Growth.

The lack of growth on long-chain aromatic (C10Ph and C12Ph) and aliphatic (C10 to C16) alkanoic acids indicates that FadD is essential for growth on these substrates. Therefore we have established that FadD from P. putida CA-3 is truly a long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase. Despite extended incubation (7 days), the deletion mutant did not revert to growth or PHA accumulation levels of the wild-type strain. This differs from the work of Olivera et al., who observed reversion of the fadD transposon insertion mutants to wild-type behavior after 80 h (>3 days) of incubation (25). Similarly, a long-chain FACS knockout mutant, KO15, of P. putida GPO1 was delayed in its growth when supplied with octanoate as the sole carbon source but adapted after initial lag phase (15 h) to achieve growth rates and final cell densities similar to those of the parental strain (31). This suggests that other enzymes can replace the activity of the interrupted gene in these organisms.

When CA-3ΔfadD was supplied with short- and medium-chain phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acids with carbon chain lengths from C3 to C9, the growth yield of the deleted mutant was either unaffected or moderately affected (Tables 5 and 6; Fig. 5). Thus, in P. putida CA-3 FadD is not essential but does contribute to the metabolism of medium-chain-length aromatic (C6Ph to C9Ph) and aliphatic (C6 to C9) substrates (Tables 5 and 6; Fig. 5). This differs from observations by Olivera et al. and Garcia et al., who observed a complete lack of growth of mutants disrupted in a FACS supplied with phenylalkanoic acids (C5Ph to C10Ph) and alkanoic acids (C5 to C10) (6, 25). This again demonstrates the long-chain nature of FadD from P. putida CA-3 in comparison to the FadD from P. putida U. Additional genetic analysis by Olivera et al. located a second acyl-CoA synthetase gene, fadD2, upstream from fadD1. Disruption of the fadD2 gene did not have any effect on the catabolism of acetic, butyric, and longer fatty acids (aliphatic or aromatic) in P. putida U. Olivera et al. suggested that fadD2 was a cryptic gene, encoding a protein with a function similar to that of the fadD1 product, which could be expressed only when fadD1 was disrupted (25). The fadD deletion mutant in P. putida CA-3 would appear to either not have or be incapable of inducing a second fadD to replace the activity under the conditions tested.

(ii) PHA accumulation.

The PHA-accumulating ability of CA-3ΔfadD mimicked that of the growth pattern, with no PHA accumulation from long-chain substrates (C12Ph and C12) (growth on glucose), lower PHA levels than those for the wild-type strain for medium-chain substrates, and levels similar to those of the wild type for short-chain substrates. There was no adaptation of the mutant to accumulate higher levels of PHA upon extended incubation. In contrast, the fadD1 mutant of P. putida U was incapable of PHA accumulation from short-, medium-, and long-chain phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acids. However, the adapted mutant could accumulate PHA to wild-type levels (25). P. putida GPO1 mutant KO15 accumulated twofold-lower levels of PHA with the medium-chain-length carbon source (C8) than did the wild-type P. putida GPO1 (31). However, long-chain substrates were not tested. CA-3ΔfadD supplied with C8 as a substrate accumulated 3.6-fold-lower levels of PHA than did the wild-type strain (Fig. 5H). The CA-3ΔfadD deletion mutant when complemented with a plasmid carrying a copy of fadD (CA-3ΔfadD+fadD) exhibited an increase in the percentage of PHA accumulated over that for CA-3ΔfadD. The complemented strain regained its ability to grow on longer-chain phenylalkanoic and alkanoic acids, confirming that observed physiological changes in the mutant were due to the specific deletion of the fadD gene.

Monomer distribution of PHA.

An increase in the percentage of short-chain monomer units incorporated into the PHA polymer was observed for the deletion mutant CA-3ΔfadD. Olivera et al. and Ren et al. reported no alternation in the monomer composition profile in polymers produced by the fadD1 and KO15 adapted mutants (25, 31). The complemented strain accumulated PHA that was more similar to the wild-type PHA, but it still contained some short-chain monomers, indicating that the expression of fadD on a plasmid was not sufficient to fully restore wild-type characteristics.

The effect of expression of an additional copy of fadD on PHA accumulation and monomer composition.

Various groups have manipulated PHA biosynthetic genes or fatty acid biosynthetic genes in an attempt to alter PHA accumulation or monomer composition (6, 26, 27, 46). In this study we noted that the expression of an extra copy of the fadD gene in P. putida CA-3 increased PHA accumulation levels up to 1.3-fold. This is in keeping with other overexpression studies (32, 44). Kraak et al. found that the expression of an additional copy of PHA polymerase C1 resulted in a 1.1- and 1.9-fold increase in PHA accumulation under nitrogen-limiting and non-nitrogen-limiting conditions, respectively, in Pseudomonas oleovorans GPO1 (18).

PHA accumulated by the recombinant strain of P. putida CA-3 (CA-3+fadD) contained monomers two carbons longer than the predominant monomer, which were not present in the wild-type strain when grown on phenylalkanoic acids. Several papers report an alteration in PHA monomer composition due to the expression of an extra copy of genes such as those for PHA polymerase (phaC), acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (phaB), and 3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase (fabG) (27, 33). While Park et al. demonstrated that the overexpression of E. coli fadD, fadE, and/or fadL genes along with the PHA synthase gene from Pseudomonas sp. strain 61-3 resulted in 1.5-fold enrichment of 3-hydroxydecanoate when cells were grown on sodium decanoate, the authors did not observe an increase in 3-hydroxydodecanoic acid monomers (two carbons longer) (26). Ren et al. observed that the E. coli fadR fadA mutant (JMU194) equipped with the PHA polymerase 2 from P. oleovorans GPO1 incorporated twofold-more (R)-3-hydroxyhexanoic acid monomer than did the wild-type strain (32). E. coli recombinants expressing PhaC1 with either PhaJ1 or PhaJ2 accumulated larger amounts of (R)-3-hydroxyhexanoic acid and (R)-3-hydroxyoctanoic acid monomers (43). However, none of the studies reported PHA containing monomer units longer than that found in the PHA produced by the wild type. To the best of our knowledge, CA-3+fadD is the only recombinant strain accumulating PHA containing longer-chain monomer units than those found in the wild-type polymer when phenylalkanoic acids are used as a carbon source. In addition, this strain accumulates PHA with an increased proportion of longer monomer units incorporated into the polymer when alkanoic acids are used as a carbon source. Since polymer properties are determined by polymer composition, the recombinant strains (CA-3+fadD and CA-3ΔfadD+fadD) may offer opportunities for the generation of PHA with novel properties.

Intermediates for PHA synthesis can be generated via de novo fatty acid synthesis, β oxidation, and elongation of fatty acids in Pseudomonas putida KT2442 (12). Haywood et al. reported that 3 to 10% of the monomeric units of PHA accumulated from hexanoic acid are one or more C2 units longer than the substrate used (10, 13). It was suggested that the presence of these longer monomers is due to a condensation reaction of acyl-CoA molecules with acetyl-CoA catalyzed by the β-oxidation enzyme 3-ketothiolase (10). An additional copy of fadD in P. putida CA-3 could result in the production of higher concentrations of both fatty acyl-CoA esters and acetyl-CoA due to an increased flux through β oxidation. The condensation of acetyl-CoA with fatty acyl-CoA esters could explain the appearance of PHA monomers two carbons longer than the feed substrate in recombinant P. putida CA-3 (CA-3+fadD) grown on phenylalkanoic acids.

Conclusion.

In conclusion, the long-chain FACS encoded by a fadD gene from P. putida CA-3 exhibits the highest catalytic activity and efficiency with long-chain substrates. It is solely responsible for the activation of long-chain aromatic and aliphatic substrates in vivo but also affects medium-chain-length substrate metabolism and conversion to PHA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the gift of pJB expression vectors from Svein Valla (Norwegian University of Science and Technology).

Aisling Hume is a recipient of a University College Dublin postgraduate scholarship. Jasmina Nikodinovic-Runic is funded by the Environmental Protection Agency Ireland (ERTDI 2005-ET-LS-9-M3).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 October 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black, P. N., C. C. DiRusso, A. K. Metzger, and T. L. Heimert. 1992. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the fadD gene of Escherichia coli encoding acyl coenzyme A synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 267:25513-25520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi, K.-H., A. Kumar, and H. P. Schweizer. 2006. A 10-min method for preparation of highly electrocompetent Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells: application for DNA fragment transfer between chromosomes and plasmid transformation J. Microbiol. Methods 64:391-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig, R., and R. C. Beavis. 2004. TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics 20:1466-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eggink, G., P. De Waard, and G. N. M. Huijberts. 1992. The role of fatty acid biosynthesis and degradation in the supply of substrates for poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) formation in Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 103:159-163. [Google Scholar]

- 6.García, B., E. R. Olivera, B. Minambres, M. Fernandez-Valverde, L. M. Canedo, M. A. Prieto, J. L. García, M. Martínez, and J. M. Luengo. 1999. Novel biodegradable aromatic plastics from a bacterial source. Genetic and biochemical studies on a route of the phenylacetyl-CoA catabolon. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29228-29241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gargiulo, C. E., S. M. Stuhlsatz-Krouper, and J. E. Schaffer. 1999. Localization of adipocyte long-chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase at the plasma membrane. J. Lipid Res. 40:881-892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golovanov, A. P., G. M. Hautbergue, S. A. Wilson, and L.-Y. Lian. 2004. A simple method for improving protein solubility and long-term stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:8933-8939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hashimoto, Y., H. Hosaka, K.-I. Oinuma, M. Goda, H. Higashibata, and M. Kobayashi. 2005. Nitrile pathway involving acyl-CoA synthetase overall metabolic gene organization and purification and characterization of the enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 280:8660-8667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haywood, G. W., A. J. Anderson, L. Chun, and E. A. Dawes. 1988. Characterization of two 3-ketothiolases possessing differing substrate specificities in the polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesizing organism Alcaligenes eutrophus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 52:91-96. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman, B. J., J. A. Broadwater, P. Johnson, J. Harper, B. G. Fox, and W. R. Kenealy. 1995. Lactose fed-batch overexpression of recombinant metalloproteins in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3): process control yielding high levels of metal-incorporated, soluble protein. Protein Expr. Purif. 6:646-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huijberts, G. N. M., T. C. De Rijk, P. De Waard, and G. Eggink. 1994. 13C nuclear magnetic resonance studies of Pseudomonas putida fatty acid metabolic routes involved in poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 176:1661-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huisman, G. W., O. De Leeuw, G. Eggink, and B. Witholt. 1989. Synthesis of poly-3-hydroxyalkanoates is a common feature of fluorescent pseudomonads. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:1949-1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kameda, K., and W. D. Nunn. 1981. Purification and characterization of acyl coenzyme A synthetase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 256:5702-5707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasuya, F., K. Igarashi, and M. Fukui. 1996. Inhibition of a medium chain acyl-CoA synthetase involved in glycine conjugation by carboxylic acids. Biochem. Pharmacol. 52:1643-1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasuya, F., Y. Yamaoka, K. Igarashi, and M. Fukui. 1998. Molecular specificity of a medium chain acyl-CoA synthetase for substrates and inhibitors conformational analysis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 55:1769-1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kornberg, A., and W. E. Pricer, Jr. 1953. Enzymatic synthesis of the coenzyme A derivatives of long chain fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 204:329-343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraak, M. N., T. H. M. Smits, B. Kessler, and B. Witholt. 1997. Polymerase C1 levels and poly(R-3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis in wild-type and recombinant Pseudomonas strains. J. Bacteriol. 179:4985-4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural protein during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lageveen, R. G., G. W. Huisman, H. Preusting, P. Ketelaar, G. Eggink, and B. Witholt. 1988. Formation of polyesters by Pseudomonas oleovorans: effect of substrates on formation and composition of poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoates and poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkenoates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:2924-2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, H.-J., M. H. Choi, T.-U. Kim, and S. C. Yoon. 2001. Accumulation of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid containing large amounts of unsaturated monomers in Pseudomonas fluorescens BM07 utilizing saccharides and its inhibition by 2-bromooctanoic acid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4963-4974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipmann, F., and C. L. Tuttle. 1945. The specific micromethod for the determination of acyl phosphates J. Biol. Chem. 159:21-28. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez-Blanco, H., A. Reglero, L. B. Rodriguez-Aparicio, and J. M. Luengo. 1990. Purification and biochemical characterization of phenylacetyl-CoA ligase from Pseudomonas putida. A specific enzyme for the catabolism of phenylacetic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 265:7084-7090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson, K. E., C. Weinel, I. T. Paulsen, R. J. Dodson, H. Hilbert, V. A. P. Martins dos Santos, D. E. Fouts, S. R. Gill, M. Pop, M. Holmes, L. Brinkac, M. Beanan, R. T. DeBoy, S. Daugherty, J. Kolonay, R. Madupu, W. Nelson, O. White, J. Peterson, H. Khouri, I. Hance, P. C. Lee, E. Holtzapple, D. Scanlan, K. Tran, A. Moazzez, T. Utterback, M. Rizzo, K. Lee, D. Kosack, D. Moesti, H. Wedler, J. Lauber, D. Stjepandic, J. Hoheisel, M. Straetz, S. Heim, C. Kiewitz, J. Eisen, K. N. Timmis, A. Dusterhoft, B. Tummler, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the metabolically versatile Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ. Microbiol. 4:799-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olivera, E. R., D. Carnicero, B. Garcia, B. Minambres, M. A. Moreno, L. Canedo, C. C. DiRusso, G. Naharro, and J. M. Luengo. 2001. Two different pathways are involved in the β-oxidation of n-alkanoic and n-phenylalkanoic acids in Pseudomonas putida U: genetic studies and biotechnological applications. Mol. Microbiol. 39:863-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park, S. J., J. P. Park, S. Y. Lee, and Y. Doi. 2003. Enrichment of specific monomer in medium-chain-length poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) by amplification of fadD and fadE genes in recombinant Escherichia coli. Enzyme Microbiol. Technol. 33:62-70. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi, Q., B. H. A. Rehm, and A. Steinbüchel. 1997. Synthesis of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) in Escherichia coli expressing the PHA synthase gene phaC2 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: comparison of PhaC1 and PhaC2. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 157:155-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi, Q., A. Steinbüchel, and B. H. A. Rehm. 1998. Metabolic routing towards polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthesis in recombinant Escherichia coli (fadR): inhibition of fatty acid β-oxidation by acrylic acid. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 167:89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raaka, B. M., and J. M. Lowenstein. 1979. Inhibition of fatty acid oxidation by 2-bromooctanoate. Evidence for the enzymatic formation of 2-bromo-3-ketooctanoyl coenzyme A and the inhibition of 3-ketothiolase. J. Biol. Chem. 254:6755-6762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rehm, B. H. A. 2003. Polyester synthases: natural catalysts for plastics. Biochem. J. 376:15-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren, Q., G. De Roo, K. Ruth, B. Witholt, M. Zinn, and L. Thony-Meyer. 2009. Simultaneous accumulation and degradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates: futile cycle or clever regulation? Biomacromolecules 10:916-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren, Q., N. Sierro, M. Kellerhals, B. Kessler, and B. Witholt. 2000. Properties of engineered poly-3-hydroxyalkanoates produced in recombinant Escherichia coli strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1311-1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren, Q., N. Sierro, B. Witholt, and B. Kessler. 2000. FabG, an NADPH-dependent 3-ketoacyl reductase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, provides precursors for medium-chain-length poly-3-hydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:2978-2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruth, K., G. De Roo, T. Egli, and Q. Ren. 2008. Identification of two acyl-CoA synthetases from Pseudomonas putida GPO1: one is located at the surface of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) granules. Biomacromolecules 9:1652-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 36.Schlegel, H. G. 1961. A submersion method for culture of hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria: growth physiological studies. Arch. Mikrobiol. 308:209-222. (In German.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shevchenko, A., M. Wilm, O. Vorm, and M. Mann. 1996. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68:850-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith, P. K., R. I. Krohn, G. T. Hermanson, A. K. Mallia, F. H. Gartner, and M. D. Provenzano. 1985. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150:76-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stadtman, E. R. 1957. Preparation and assay of acyl-coenzyme A and other thioesters; use of hydroxylamine. Methods Enzymol. 3:931-941. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinbüchel, A., and S. Hein. 2001. Biochemical and molecular basis of microbial synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates in microorganisms. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 71:81-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thijsse, G. J. E. 1964. Fatty-acid accumulation by acrylate inhibition of beta-oxidation in an alkane oxidizing Pseudomonas. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 84:195-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tobin, K. M., and K. E. O'Connor. 2005. Polyhydroxyalkanoate accumulating diversity of Pseudomonas species utilising aromatic hydrocarbons. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 253:111-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsuge, T., T. Fukui, H. Matsusaki, S. Taguchi, G. Kobayashi, A. Ishizaki, and Y. Doi. 2000. Molecular cloning of two (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase genes from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their use for polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 184:193-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vo, M. T., K.-W. Lee, Y.-M. Jung, and Y.-H. Lee. 2008. Comparative effect of overexpressed phaJ and fabG genes supplementing (R)-3-hydroxyalkanoate monomer units on biosynthesis of mcl-polyhydroxyalkanoate in Pseudomonas putida KCTC1639. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 106:95-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Witholt, B., and B. Kessler. 1999. Perspectives of medium chain length poly(hydroxyalkanoates), a versatile set of bacterial bioplastics. Environ. Biotechnol. 10:279-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan, M.-Q., Z.-Y. Shi, X.-X. Wei, Q. Wu, S.-F. Chen, and G.-Q. Chen. 2008. Microbial production of medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanoic acids by recombinant Pseudomonas putida KT2442 harboring genes fadL, fadD and phaZ. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 283:167-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.