Abstract

The opportunistic human bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa produces membrane vesicles (MVs) in its surrounding environment. Several features of the P. aeruginosa MV production mechanism are still unknown. We previously observed that depletion of Opr86, which has a role in outer membrane protein (OMP) assembly, resulted in hypervesiculation. In this study, we showed that the outer membrane machinery and alginate synthesis regulatory machinery are closely related to MV production in P. aeruginosa. Depletion of Opr86 resulted in increased expression of the periplasmic serine protease MucD, suggesting that the accumulation of misfolded OMPs in the periplasm is related to MV production. Indeed, the mucD mutant showed a mucoid phenotype and the mucD mutation caused increased MV production. Strains with the gene encoding alginate synthetic regulator AlgU, MucA, or MucB deleted also caused altered MV production. Overexpression of either MucD or AlgW serine proteases resulted in decreased MV production, suggesting that proteases localized in the periplasm repress MV production in P. aeruginosa. Deletion of mucD resulted in increased MV proteins, even in strains with mutations in the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS), which serves as a positive regulator of MV production. This study suggests that misfolded OMPs may be important for MV production, in addition to PQS, and that these regulators act in independent pathways.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic human pathogen, causing infections in cystic fibrosis (CF) and burn patients, as well as other immunocompromised individuals (12, 55). The biofilm-forming ability of P. aeruginosa and of other bacteria is thought to contribute to their ability to thrive in hostile host environments and cause chronic infection. The P. aeruginosa biofilm matrix is mainly composed of cells, extracellular proteins, DNA, and polysaccharides, including alginate, pel product, and psl product (13, 16, 50, 70, 75).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and many other gram-negative bacteria naturally produce membrane vesicles (MVs), which are released from their outer surface. These bilayered spheres are made up of outer membrane proteins (OMPs), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and phospholipids, and they encapsulate periplasmic components (5, 6). P. aeruginosa MVs contain some secreted virulence factors for killing host cells or other bacteria, including proelastase, hemolysin, phospholipase C, alkaline phosphatase, and Cif (25, 32), and antibacterial factors, such as murein hydrolases (23, 24, 26, 29, 30). Recent reports indicated that P. aeruginosa MVs deliver them directly into the host cell cytoplasm and contribute to the inflammatory response during infection (3, 4, 7). To control P. aeruginosa pathogenicity, it is important to know the mechanism of MV production in P. aeruginosa. Although MVs have been well studied in terms of transmission of materials involved in pathogenicity, the production mechanism has not been elucidated completely.

On a relevant note, recent studies have indicated that P. aeruginosa MVs contain a quorum-sensing signaling molecule 2-heptyl-3-hydroxyl-4-quinolone (Pseudomonas quinolone signal [PQS]) (37), as well as an antimicrobial quinolone (20); these molecules serve as mediators of cell-cell communication (47). This signal serves as a coinducer for the transcriptional activator PqsR (MvfR), which positively regulates PQS production to create an autoregulatory loop that regulates the expression of multiple virulence factors in P. aeruginosa (14). PQS is derived from anthranilate through PqsABCD and finally synthesized by PqsH. In P. aeruginosa, MV production increases when adjacent lipid A molecules in the outer membrane exhibit charge repulsion (39). PQS interacts strongly with the acyl chains and 4′-phosphate of bacterial LPS and increases MV production (38).

We previously reported that Opr86 depletion causes tremendous blebbing in P. aeruginosa (63), but little is known about how Opr86 depletion causes increased MV production. Opr86 belongs to the Omp85/YaeT family, which is conserved in all gram-negative bacteria (51, 66). An OMP belonging to the Omp85/YaeT family was shown to be essential for viability, have a role in assembly or insertion of OMPs, and act as a protective antigen (15, 31, 44, 63, 66, 68, 76, 77). The mechanism of OMP assembly has been studied well in Escherichia coli. YaeT is a part of complex that contains four lipoproteins, YfgL, YfiO, NlpB, and SmpA, and plays a central role in assembly of β-barrel OMPs (33, 43, 56, 76).

Stress, such as an elevated temperature, is thought to lead to the accumulation of misfolded OMPs in the periplasm and cause envelope stress (1, 67). Recently, it has been shown that misfolded OMPs regulate σ22 activity and activate alginate synthesis in P. aeruginosa (48). The P. aeruginosa sigma factor σ22 is encoded by algU (algT) and is required for the production of alginate (17, 18). The algU operon consists of algU-mucABCD. MucA is an anti-sigma factor that sequesters σ22 (40, 53), and mutations in mucA are common in mucoid P. aeruginosa isolates from CF patients (35). The products of the other members of this operon, MucB (AlgN), MucC, and MucD, also appear to act in a negative manner along with MucA to inhibit AlgU activity (8, 9, 19, 34). MucD is a periplasmic serine protease and involved in alginate synthesis and virulence (8, 72, 78). AlgW also plays a role in regulating AlgU activity and alginate production (48). Sigma factor σ22 of P. aeruginosa has homology to the extracytoplasmic-function σE of E. coli. Recent studies reported that the σE pathway is associated with MV production in E. coli (11, 41, 42). However, the relationship between envelope stress response and MV production in P. aeruginosa is unknown.

Since misfolded OMPs regulate alginate synthesis in P. aeruginosa (48), it is believed that misfolded OMPs are not only unnecessary compounds but also intracellular signals to activate cellular phenotypes. In this study, we investigated the effects of OMP machinery-associated factors and alginate synthesis regulators on MV production in P. aeruginosa. Moreover, we analyzed a relationship between misfolded OMPs and PQS, which both regulate MV production, and suggest a model of MV production in P. aeruginosa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids that were used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli and P. aeruginosa were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB Lennox; Nacalai, Kyoto, Japan) medium. When necessary, the following antibiotics were used: 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 10 μg/ml gentamicin for E. coli and 200 μg/ml carbenicillin and 100 μg/ml gentamicin for P. aeruginosa.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Description, relevant characteristic(s), relevant genotype, or sequencea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| P. aeruginosa strains | ||

| PAO1 | Wild type | 21 |

| Δopr86 mutant | PAO1 Δopr86 mutant carrying pMMB6786 | This study |

| ΔmucD mutant | PAO1 ΔmucD mutant | This study |

| ΔmucD Δopr86 mutant | PAO1 ΔmucD Δopr86 double mutant carrying pMMB6786 | This study |

| ΔalgW mutant | PAO1 ΔalgW mutant | This study |

| ΔalgU mutant | PAO1 ΔalgU mutant | This study |

| ΔmucA mutant | PAO1 ΔmucA mutant | This study |

| ΔmucB mutant | PAO1 ΔmucB mutant | This study |

| ΔpqsH mutant | PAO1 ΔpqsH mutant | 65 |

| ΔpqsR mutant | PAO1 ΔpqsR mutant | 65 |

| ΔpqsH ΔmucD mutant | PAO1 ΔpqsH ΔmucD double mutant | This study |

| ΔpqsR ΔmucD mutant | PAO1 ΔpqsR ΔmucD double mutant | This study |

| pqsH-xylE strain | PAO1 carrying a chromosomal pqsH-xylE fusion | This study |

| ΔmucD pqsH-xylE mutant | ΔmucD mutant carrying a chromosomal pqsH-xylE fusion | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| JM109 | recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thi Δ(lac-proAB) F′ (traD36 proAB+lacIqlacZΔM15) | TaKaRa |

| S17-1 | pro thi hsdR recA Tpr Smr; chromosome::RP4-2 Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 | 54 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pHSG398 | Cloning vector; Cmr | TaKaRa |

| pG19II | Derivative of pK19 mob sacB; Gmr | 36 |

| pG19-delopr86 | opr86 deletion cassette in pG19II | 63 |

| pG19mucD | mucD deletion cassette in pG19II | This study |

| pG19algW | algW deletion cassette in pG19II | This study |

| pG19algU | algU deletion cassette in pG19II | This study |

| pG19mucA | mucA deletion cassette in pG19II | This study |

| pG19mucB | mucB deletion cassette in pG19II | This study |

| pG19pqsHX | pqsH-xylE cassette in pG19II | This study |

| pMMB6786 | pMMB67EH derivative carrying the opr86 gene; Ampr | 63 |

| pUCP24 | P. aeruginosa expression vector | 69 |

| popr86 | opr86 on pUCP24 | This study |

| pmucD | mucD on pUCP24 | This study |

| palgW | algW on pUCP24 | This study |

| pmucDalgW | mucD-algW on pUCP24 | This study |

| pMEX9 | pME4510-derived promoter-probe vector; xylE Gmr | 64 |

| pMEXalgU | algU promoter region in pMEX9 | This study |

| pMEXmucD | mucD promoter region in pMEX9 | This study |

| Primers | ||

| mucD1 | 5′-CGGGATCCGCGCTCGGAATGGCTGCCG-3′ | This study |

| mucD2 | 5′-GGCCAGCTCAGCTCCCGTGATGTTCGAGGG-3′ | This study |

| mucD3 | 5′-GGGAGCTGAGCTGGCCGAATAAGCCGGCTG-3′ | This study |

| mucD4 | 5′-CCCAAGCTTCGTACCAGCGAGACCACGCC-3′ | This study |

| algW1 | 5′-CGGGATCCCCCGTAGCGCTCGGTGGC-3′ | This study |

| algW2 | 5′-GACGGGGTCCTTGGGGTTGCGAGGCCG-3′ | This study |

| algW3 | 5′-CCCCAAGGACCCCGTCATTGAAAACGGCGC-3′ | This study |

| algW4 | 5′-CCCAAGCTTCCAACACGACCTGCCGCTGC-3′ | This study |

| algUF1 | 5′-CCGAAGCTTGGAAGGTATCGACTTCGCCGC-3′ | This study |

| algUR1 | 5′-CGGAATTCAGGGATCGAACTTGCGCACCG-3′ | This study |

| algUF2 | 5′-GCGGATCCCACAGCGGCAAATGCCAAGAGAGG-3′ | This study |

| algUR2 | 5′-CGGGATCCGAAAGCTCCTCTTCGAACCTGG-3′ | This study |

| mucA1 | 5′-CGGATCCGCATCGGTTCCAAAGCAGG-3′ | This study |

| mucA2 | 5′-CTGCGGCGCCCCTGCTCTTCGCTGTAGC-3′ | This study |

| mucA3 | 5′-AGAGCAGGGGCGCCGCAGGTGATCACC-3′ | This study |

| mucA4 | 5′-GCTCTAGACCTGCTCCTCGATCATTTCTGG-3′ | This study |

| mucB1 | 5′-CGGGATCCCCTTCATCAAGGCATACCGTGC-3′ | This study |

| mucB2 | 5′-CGCTCGAGGTCTCTCCTCAGCGGTTTTCC-3′ | This study |

| mucB3 | 5′-GGAGAGACCTCGAGCGCTTCCAGTTCACC-3′ | This study |

| mucB4 | 5′-GCTCTAGAGGTCGGCAGGTTCTTCGCCTCG-3′ | This study |

| PalgUF | 5′-GGAATTCGCCCGCATTTCCCCGTGGTGG-3′ | This study |

| PalgUR | 5′-CCCAAGCTTGCTCCTCTTCGAACCTGGAGG-3′ | This study |

| PmucDR | 5′-GGAATTCGCCAGCCGGCTTATTCGGCC-3′ | This study |

| mucDF | 5′-GGAATTCGGGAGCTGTAGTCGATGCATACCC-3′ | This study |

| mucDR | 5′-CGGGATCCGCCAGCCGGCTTATTCGGCC-3′ | This study |

| mucDR2 | 5′-GGAATTCGCCAGCCGGCTTATTCGGCC-3′ | This study |

| algWF | 5′-GGAATTCAAGGATTTTCCCGATGCCCAAGGCC-3′ | This study |

| algWR | 5′-CGGGATCCGGATCACTCGCCGCCGTCC-3′ | This study |

| pqsHX1 | 5′-GGAATTCCTGGATGAGTCGCGCATTCGGG-3′ | This study |

| pqsHX2 | 5′-GCTCTAGACTACTGTGCGGCCATCTCACCG-3′ | This study |

| pqsHX3 | 5′-GCTCTAGATGCCAGTGGCGTCTTGGTCGCC-3′ | This study |

| pqsHX4 | 5′-CCCAAGCTTGATCTCGCCCTCGGACAGCG-3′ | This study |

| mucD-RTF | 5′-ACGCTGTATGGCTGCGATGG-3′ | This study |

| mucD-RTR | 5′-ATGCTGCGCTCGAGGAAGTC-3′ | This study |

| algW-RTF | 5′-CTGATCATCCAGCACAACCC-3′ | This study |

| algW-RTR | 5′-TGTACAGGTTGGCCACTGCC-3′ | This study |

| rplU-RTF | 5′-CGCAGTCATTGTTACCGGTG-3′ | This study |

| rplU-RTR | 5′-AGGCCTGAATGCCGGTGATC-3′ | This study |

Drug resistance phenotype designations: Tpr, trimethoprim resistance; Smr, streptomycin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Gmr, gentamicin resistance; Ampr, ampicillin resistance. The added restriction sites in the primers are underlined.

Construction of mutants.

The construction of several mutants of P. aeruginosa PAO1 was achieved by conjugation and homologous recombination. Plasmid pG19mucD, which carried deletion cassettes of mucD, was constructed as follows. The DNA fragment was amplified from the PAO1 chromosome with primers mucD1/mucD2 and mucD3/mucD4 (listed in Table 1). These flanking DNA fragments were joined using overlap extension PCR. The resulting PCR fragment was digested with BamHI/HindIII and ligated into a multicloning site of pG19II to yield pG19mucD. Plasmids pG19algW, pG19mucA, and pG19mucB were constructed in the same way with restriction enzymes corresponding to their respective primers. Plasmid pG19algU carrying the deletion cassette of algU was constructed by the procedure described previously (36). The DNA fragment was amplified from the PAO1 chromosome with primers algUF1/algUR1, digested with HindIII/EcoRI, and ligated into a multicloning site of cloning vector pHSG398. The DNA flanking fragment of algU on pHSG398 was amplified using inverse PCR with primers algUF2/algUR2, digested with BglII, and self-ligated. The algU flanking fragment was digested with HindIII/EcoRI and ligated into a multicloning site of pG19II to yield pG19algU. The plasmid pG19 series (Table 1) were introduced into the mobilizer E. coli strain S17-1 and then were transferred into P. aeruginosa PAO1 by conjugation as reported earlier (36, 63). The deletion of the chromosomal gene was confirmed by PCR analysis.

Construction of plasmids for overexpression.

The mucD and algW genes were amplified with primers mucDF/mucDR or algWF/algWR, digested with EcoRI/BamHI, and cloned in pUCP24 under the lac promoter to yield plasmids pmucD and palgW. The amplified mucD gene with primers mucDF/mucDR2 was digested with EcoRI and cloned into plasmid palgW between the lac promoter and algW to yield plasmid pmucDalgW. These plasmids were electoroporated in the wild-type (WT) strain PAO1 or in the ΔmucD, ΔalgW, or ΔalgU mutant.

Isolation and purification of MVs.

MVs were isolated using a modified version of the procedure reported by Kadurugamuwa and Beveridge (25). P. aeruginosa was grown in LB medium at 37°C for 12 h with shaking at 150 rpm. Cells were removed by centrifugation (6,000 × g, 15 min), and supernatants were filtered first through a 0.45-μm cellulose acetate filter and then a 0.22-μm cellulose acetate filter. Filtrates were ultracentrifuged (150,000 × g, 3 h, 4°C) in a Beckman type 45 rotor, and pellets were washed with 10 mM HEPES (pH 6.8) containing 0.85% NaCl (HEPES-NaCl). For MV purification, the method was modified from the procedure reported by Horstman and Kuehn (22). The crude MV sample was adjusted to 45% Optiprep in HEPES-NaCl with EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) per the manufacturer's instructions. An Optiprep gradient was layered over the 0.5-ml crude MV sample with 0.5 ml Optiprep in HEPES-NaCl (40%, 35%, 30%, 25%, 20%, 15%, and 10%) with protease inhibitor. Gradients were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 3 h in a Beckman SW41Ti rotor, and the MV fraction was extracted and washed with HEPES-NaCl.

MV mass measurement.

The quantity of MVs was determined by protein assay and phospholipid assay. In the protein assay, extracted MVs were homogenized, and the protein concentration was measured by the Bradford method (10). Bovine serum albumin was used as a reference standard. Since the proteolytic activities of the supernatants were not significantly different among the WT strain and the ΔmucD, ΔalgW, ΔalgU, ΔmucA, and ΔmucB mutants (data not shown), we considered that extracellular proteases did not affect the difference of MV production. Proteolytic activity was determined by an azocasein assay as previously reported (27) with some modifications. Briefly, 10 μl of cell-free supernatant was added to 0.5 ml of 0.3% azocasein (Sigma) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2) and 0.5 mM CaCl2 and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.5 ml of 10% trichloroacetic acid. After centrifugation (15,000 × g, 20 min), the absorbance at 400 nm (A400) in the supernatant was measured. The MV phospholipid concentration was measured using a modified version of the procedure reported by Stewart et al. (60). Briefly, extracted MVs were homogenized, and 10 μl of the MV sample, 100 μl of ammonium ferrothiocyanate solution (27.03 g/liter ferric chloride hexahydrate and 30.4 g/liter ammonium thiocyanate), and 100 μl of chloroform were vortexed. The absorption of the lower layer was measured at 488 nm. l-α-Phosphatidylethanolamine was used as a reference standard. MV production was measured by the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) and compared with an indicated control strain to determine relative MV production.

Quantification of C23O activities.

To examine the transcriptional activities of the algU promoter and mucD promoter, these DNA fragments were amplified from the PAO1 chromosome with primers PalgUF/PalgUR or mucD1/PmucDR, digested with BamHI/HindIII or EcoRI/HindIII, and ligated into the pMEX9 plasmid upstream of xylE to yield plasmids pMEXalgU and pMEXmucD, respectively. These plasmids were introduced into the WT strain PAO1 or the ΔalgW, ΔalgU, ΔmucA, or ΔmucB mutants. To examine the transcriptional activity of pqsH, the xylE gene cassette was inserted downstream of the chromosomal pqsH gene as follows. Two 0.8-kb DNA fragments were amplified from PAO1 chromosomal DNA with primers pqsHX1/pqsHX2 or with primers pqsHX3/pqsHX4, digested with EcoRI/XbaI or XbaI/HindIII, respectively, and ligated into the EcoRI-HindIII site of plasmid pG19II. The xylE fragment, digested from pX1918 with XbaI, was then inserted into the XbaI site of the constructed plasmid to yield pG19pqsHX in which xylE lies downstream of pqsH. This plasmid was introduced into the mobilizer strain E. coli S17-1 and transferred into strain PAO1 (WT) and ΔmucD mutant using conjugation as reported earlier (36). An assay for activity of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase (C23O) (the xylE product) was performed by the method of Maseda et al. (36). Cells cultured for 6 h were homogenized, and lysed protein samples were used. The A375 was recorded at 30°C. Specific activity was defined as nanomoles of product formed per minute per milligram of protein (ɛ1 cm = 4.4 × 104).

Quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR).

The cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.4 in LB medium. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation, the supernatants were removed, and cell pellets were frozen in an ice-ethanol bath and stored at −80°C until RNA extractions were performed. Total RNA was extracted from approximately 108 cells by using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as described by the manufacturer. Qiagen on-column DNase was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Additional DNase treatment was performed using Qiagen DNase I, and RNA was purified using the RNeasy kit again. The cDNA synthesis was performed from 1 μg RNA using RT SuperScript III (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with random hexamers. The cDNA was used as a template for PCRs completed with the primers shown in Table 1. Real-time PCR was conducted using LightCycler (Roche) with the LightCycler FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR green I kit. The rplU gene was used as the internal control, and data were normalized to rplU expression.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

For sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), samples were denatured at 98°C for 10 min using sample buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% (wt/vol) SDS, 6% (vol/vol) 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 0.02% bromophenol blue. The samples were resolved using 15% SDS-PAGE, fixed in 50% methanol and 10% acetic acid, and visualized by Coomassie brilliant blue staining or silver staining (Daiichikagaku, Tokyo, Japan). Western blot analysis with p-Opr86 antiserum (1/1,000 dilution) was performed as described previously (63). The intensities of protein bands were evaluated using densitometric scanning (Image Master ID Elite; GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

Bacterial viability assay.

The viability of P. aeruginosa in planktonic shaking culture was determined by using BacLight live/dead bacterial viability staining kit (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR) as described previously (63).

TEM.

Purified vesicles were placed on Formvar-coated copper grids (200 mesh), which were then stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate for 1 min, rinsed, and observed with a JEOL-1010 transmission electron microscope (TEM) (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 80 kV.

PQS detection assay.

PQS was extracted from 1 ml of cell-free supernatant, ultracentrifuged supernatant (without MVs) or extracted MVs with acidified ethyl acetate, and separated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) as described previously (65). The intensities of PQS spots were evaluated using densitometric scanning (Image Master ID Elite; GE Healthcare).

RESULTS

Overexpression of Opr86 decreases MV production.

To quantify MVs in the supernatant of P. aeruginosa PAO1, cell-free supernatant from overnight culture was ultracentrifuged, and the pellets containing MVs were extracted. To evaluate MV production, the protein concentration in the ultracentrifuged pellets was measured (38, 45). However, it has also been reported that the ultracentrifuged pellets contain other components, such as flagella and pili (4). We fractionated the crude pellets by previously reported methods using an Optiprep density gradient (22). The pellets from P. aeruginosa PAO1 supernatant localized to a main band at a medium location (buoyant density, 1.15 g/ml) and a minor band at a heavier layer (buoyant density, 1.20 g/ml). The concentrations of proteins and phospholipids in each fraction were also examined; over 90% of proteins and over 99% of phospholipids were contained in a major band (data not shown). The existence of MVs in the peak fractions could be confirmed by electron microscopy (data not shown). Hence, we concluded that the protein assay of ultracentrifuged pellets roughly represented MV quantities and that the phospholipid assay was more accurate.

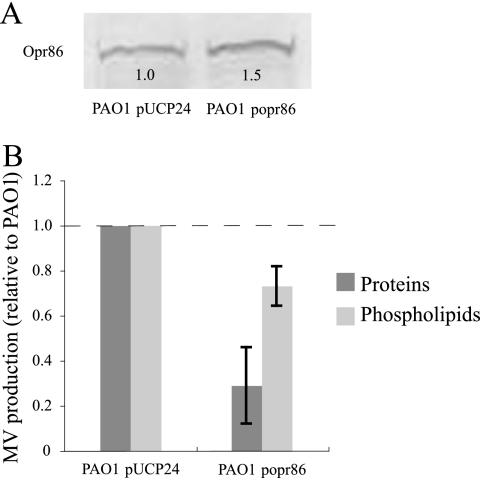

In our previous study, it was observed by scanning electron microscopy that the Opr86 deletion mutant releases many MVs (63). However, it is difficult to quantify accurately how many MVs the Opr86 deletion mutant produces because the growth of Opr86 deletion mutant is remarkably repressed in the absence of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). To confirm the relationship between Opr86 and MV production, we first examined the quantities of MVs in the supernatants of the control strain [PAO1(pUCP24)] and the opr86 overexpression strain [PAO1(popr86)] after 12 h of incubation in LB medium. Growth curve analysis confirmed that P. aeruginosa PAO1 growth was unaffected by the overexpression of Opr86 (data not shown), and immunoblotting analysis confirmed that Opr86 in PAO1(popr86) was overexpressed compared to PAO1(pUCP24) (Fig. 1A). MV production in the Opr86 overexpression strain was less than that of the parent strain: in particular, the protein concentration was decreased in MVs released from the strain expressing Opr86 (Fig. 1B). TLC analysis indicated that PQS quantities in the supernatants are not different for these two strains (data not shown). These data suggest that Opr86 negatively regulates MV production and that this regulation is independent of the PQS pathway.

FIG. 1.

Overexpression of Opr86 decreases MV production. (A) Western blot analysis using Opr86 antibody. Total proteins were extracted from cells of PAO1 carrying plasmid pUCP24 and PAO1 carrying plasmid popr86 at the exponential phase, and 20 μg of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE. The numbers below the Opr86 bands on the Western blot showed the relative densitometry values compared to the WT strain PAO1(pUCP24). (B) MV production of PAO1(pUCP24) and PAO1(popr86) after 12 h of growth. The values are compared to the values for PAO1(pUCP24). Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three independent experiments.

MucD expression is important under Opr86 depletion conditions.

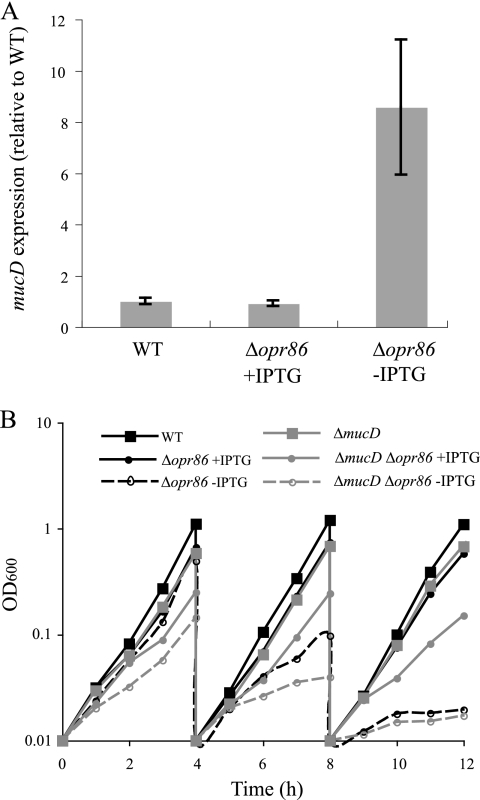

Since Opr86 plays a role in OMP assembly (63) and overexpression of Opr86 resulted in decreased MV production (Fig. 1B), it was hypothesized that accumulation of misfolded OMPs triggers MV production. To elucidate the relationship between Opr86 depletion and the accumulation of misfolded OMPs in the periplasm, we focused on MucD, which is a serine protease that recognizes misfolded OMPs and localizes to the periplasm (8, 72, 73). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis showed that Opr86 depletion increases mucD transcription by about 10-fold (Fig. 2A), suggesting that misfolded OMPs accumulate in the periplasm under Opr86 depletion.

FIG. 2.

Relationship between Opr86 and periplasmic protease MucD. (A) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of mucD transcript levels at the exponential phase in P. aeruginosa PAO1 and in the Δopr86 mutant treated with 100 μM IPTG (+IPTG) or not treated with IPTG (−IPTG). The values are compared to the values for the WT strain (PAO1). Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (error bars) from triplicate samples. Similar results were obtained from three independent experiments. (B) Growth curves of LB cultures in the absence and presence of 100 μM IPTG. After 4 and 8 h of incubation, cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.01. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

To further examine the effects of Opr86 depletion on accumulation of OMPs in the periplasm, the growth curves were analyzed under Opr86 or MucD depletion. Under Opr86 depletion conditions, the absence of MucD accelerated the cessation of growth compared with when MucD was normally expressed (Fig. 2B). In addition, the cells at the 8-h growth point shown in Fig. 2B were stained with SYTO9 and propidium iodide. The viable cell rates were as follows: 100% (±<0.1%) for the WT strain (PAO1), 97% (±1%) for the Δopr86 mutant in the presence of IPTG, 68% (±11%) for the Δopr86 mutant in the absence of IPTG, 98% (±1%) for the ΔmucD mutant, 88% (±2%) for the ΔmucD Δopr86 mutant in the presence of IPTG, and 48% (±8%) for the ΔmucD Δopr86 mutant in the absence of IPTG. These results suggest that the activity of MucD against misfolded OMPs is important for viability under Opr86 depletion conditions.

MucD depletion increases MV production.

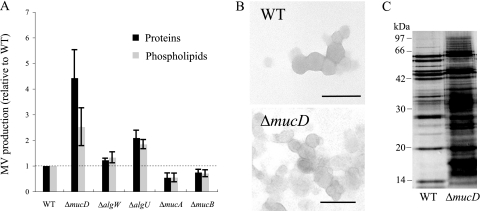

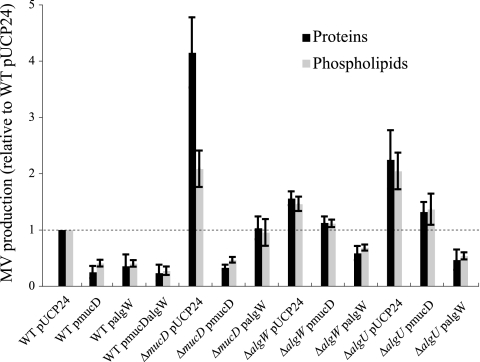

It is known that MucD and AlgW are serine proteases localized in the periplasm in P. aeruginosa (8). Here, we examined whether MucD and AlgW are related to MV production. We constructed ΔmucD and ΔalgW mutants. While the ΔmucD mutant, which showed a mucoid phenotype (data not shown), displayed increased MV production compared to the WT strain (PAO1), about fourfold-higher protein level and about twofold-higher phospholipid level, MV production in the ΔalgW mutant was barely different from that in the WT (Fig. 3A). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis indicated that mucD expression is 7.04-fold (±0.78-fold) greater than algW expression during the exponential phase in the WT. We concluded that MucD plays the main role of degrading misfolded OMPs, and for that reason, deletion of AlgW did not affect MV production.

FIG. 3.

Effects of chromosomal mucD deletion on MV production. (A) MV production of the WT strain (PAO1) and ΔmucD, ΔalgW, ΔalgU, ΔmucA, and ΔmucB mutant strains after 12 h of culture. The values are compared to the values for the WT strain. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three independent experiments. (B) Electron micrographs of negatively stained MVs purified from supernatants from the WT and ΔmucD strains. Bar, 100 nm. (C) SDS-PAGE protein profiles of MVs purified from supernatants from the WT and the ΔmucD mutant. One microgram of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with silver. The positions of molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are shown to the left of the gel.

It is well-known that deletion of MucD leads to the activation of σ22 (8, 48). To examine whether inactivation of σ22 leads to decreased MV production, we constructed a ΔalgU mutant and investigated MV production in the ΔalgU mutant. In contrast to our expectation, the ΔalgU mutant showed an approximately twofold increase in MV production (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the effect of MucD on the increase of MV production is not due to σ22 activation but that σ22 is related to MV production. It is also known that AlgU negatively controls flagellum synthesis in P. aeruginosa (18, 62). When crude ultracentrifuged pellets from supernatants of ΔmucD, ΔalgW, and ΔalgU mutants were subjected to Optiprep density gradient centrifugation and protein concentrations were examined, over 90% of proteins were found in MVs in all cultures as well as the WT (data not shown). These data indicate that MucD and AlgU negatively control MV production.

To further examine the effects of alginate synthetic regulators, we tested MV production in ΔmucA and ΔmucB mutants. The ΔmucA mutant showed a hypermucoid phenotype, and the ΔmucB mutant showed a mucoid phenotype compared to the WT (data not shown). In the results from the quantitative MV assay, ΔmucA and ΔmucB mutants showed decreased MV production (Fig. 3A). When extracted MVs from the WT were added to the MV-free supernatant of the WT or ΔmucA mutant and the MV-resuspended solutions were ultracentrifuged to examine the effect of alginate on precipitation, the protein and phospholipid contents of the pellets were not different in these samples (data not shown), suggesting that alginate in the supernatant of the ΔmucA mutant does not affect the precipitation of MVs. These results support the idea that alginate synthesis regulators are linked to MV production.

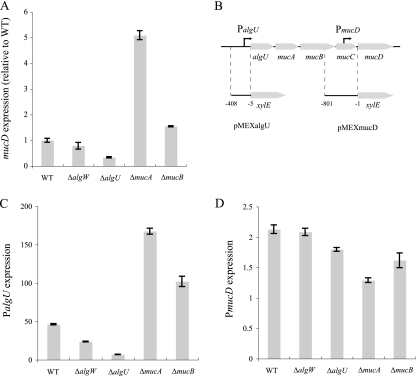

We presumed that alginate synthesis regulators affect mucD expression and hence lead to altered MV production. To verify this presumption, we examined mucD expression in the WT strain (PAO1) and in ΔalgW, ΔalgU, ΔmucA, and ΔmucB mutant strains by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Expression of mucD was almost inversely related to MV production; in particular, the deletion of algU decreased mucD expression, and deletion of mucA resulted in increased mucD expression (Fig. 4A). It is known that mucD transcription is activated by the algU promoter (PalgU) and another independent mucD promoter (PmucD) (73). Each promoter was inserted into the front of xylE in reporter plasmid pMEX9 (Fig. 4B), and the effects of alginate synthesis regulators on those promoter activities were analyzed. The activity of PalgU was much higher than that of PmucD in the WT (Fig. 4C and D), suggesting that mucD expression for the most part is affected by PalgU activity. The results of PalgU transcription were similar to the result from quantitative real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 4A and C). Deletion of algU resulted in decreased PalgU expression (Fig. 4C), leading to positive autoregulation by AlgU. In contrast, deletion of mucA resulted in increased PalgU expression (Fig. 4C). This effect was suggested by the previous report that MucA binds to AlgU and inhibits it from acting as a positive transcriptional regulator (40, 53). In the same way, depletion of MucB, which is also a negative regulator of AlgU, led to increased PalgU expression (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that some alginate synthesis regulators control MV production by altering mucD expression.

FIG. 4.

MucD expression in the WT strain and in ΔalgW, ΔalgU, ΔmucA, and ΔmucB mutant strains. (A) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of mucD transcript levels in cells at the exponential phase. The values are compared to those for the WT. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (error bars) from triplicate samples. Similar results were obtained from three independent experiments. (B) Organization of the algU-mucABCD gene cluster. The fragments inserted upstream of the xylE gene in plasmids pMEXalgU and pMEXmucD are shown. (C and D) Catechol 2,3-dioxygenase (C23O) activity assays of PalgU (C) and PmucD (D) transcript levels. C23O activity in the cells in which plasmid pMEXalgU or pMEXmucD was introduced were measured and normalized against the C23O activity of the cells in which pMEX9 was introduced. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three independent experiments.

To examine the effects of MucD on MV production in detail, MVs were purified from supernatants of WT or ΔmucD cultures. The TEM observation analysis showed that MVs isolated from the ΔmucD culture were not altered in terms of size and configuration compared to those from the WT culture (Fig. 3B). However, analysis of SDS-PAGE protein profiles indicated that MVs released from the ΔmucD mutant contained many kinds of bands that are not detected in the MVs released from the WT (Fig. 3C), and it is believed that these bands are misfolded OMPs. As presumed before, this result supports the idea that misfolded OMPs regulate MV production.

Overexpression of MucD or AlgW represses MV production.

To further analyze the effects of serine proteases localized in the periplasm, we tested MV production during overexpression of MucD or AlgW. PAO1 carrying plasmid pmucD and PAO1 carrying plasmid palgW showed decreased MV production compared to PAO1(pUCP24) (Fig. 5). PAO1(pmucDalgW), in which both MucD and AlgW are overexpressed, also displayed decreased MV production (Fig. 5). We also tested the effects of overexpression of MucD and AlgW on MV production in ΔmucD and ΔalgW mutants. While the ΔmucD mutant carrying plasmid pmucD and the ΔalgW mutant carrying plasmid palgW showed decreased MV production at the same level of PAO1(pmucD) or PAO1(palgW), the ΔmucD mutant carrying palgW and ΔalgW mutant carrying pmucD did not repress MV production to the same degree (Fig. 5). These results suggested that overexpression of periplasmic proteases represses MV production, but the selectivity of OMP degradation in MucD and AlgW may not be completely identical.

FIG. 5.

Effects of mucD and/or algW multicopies on MV production. Values are compared to the values for PAO1 carrying plasmid pUCP24. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three independent experiments. ΔmucD pmucD, ΔmucD mutant carrying plasmid pmucD.

We observed that the deletion of AlgU resulted in increased MV production (Fig. 3A) and considered the idea that the effect of AlgU on MV production was due to upregulation of MucD expression (Fig. 4). To further verify this notion, we tested the effect of overexpression of MucD on MV production in a ΔalgU mutant. The result showed that the ΔalgU mutant carrying plasmid pmucD partially complemented production compared to PAO1(pUCP24) (Fig. 5), suggesting that AlgU downregulation of MV production is related to MucD proteolytic activity but does not completely depend on it. In contrast, the ΔalgU mutant carrying plasmid palgW showed decreased MV production as well as PAO1 (palgW) (Fig. 5). These results suggest that overexpression of periplasmic proteases represses MV production, even in the σ22-defective strain.

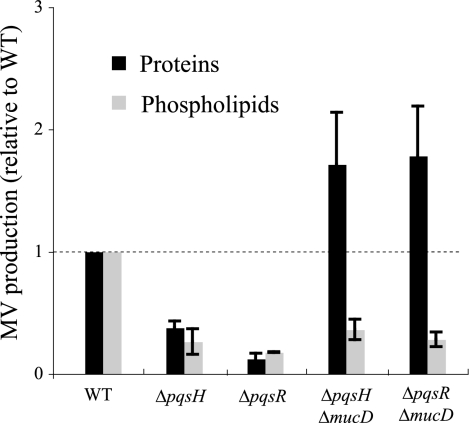

Effect of MucD on MV production in PQS-defective strains.

It has been reported that PQS is a positive regulator of MV production in P. aeruginosa (37). In addition, the results of this study suggested that periplasmic proteases repress MV production in P. aeruginosa (Fig. 3A and 5). To examine whether the effect of periplasmic proteases on MV production depends on the PQS pathway, we constructed ΔpqsH ΔmucD and ΔpqsR ΔmucD double mutants, which both accumulate misfolded OMPs in the periplasm and do not produce PQS, and tested MV production. The levels of MVs in ΔpqsH and ΔpqsR mutants were decreased at both the protein level and phospholipid level (Fig. 6), and these results are consistent with a previous report by Mashburn and Whiteley (37). Deletion of mucD in these mutants showed the same level of MV phospholipid quantities as in ΔpqsH and ΔpqsR mutants but showed high MV protein quantities, suggesting that MucD is related to MV proteins. Moreover, since MucD also affects MV production in a PQS-defective strain, it is thought that these two processes are in independent pathways.

FIG. 6.

Effect of MucD on MV production in PQS-defective strains. Values are compared to the values for the WT. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three independent experiments.

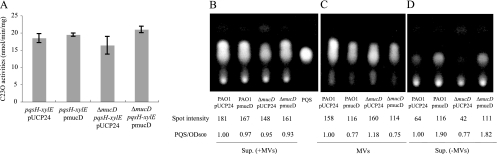

Alteration of MucD expression changes PQS localization.

It has been reported that MVs act as PQS carriers in the P. aeruginosa supernatants (37). We asked whether change in MV production by MucD regulation affect PQS synthesis. To test this, the pqsH-xylE allele was introduced into the WT strain (PAO1) or the ΔmucD mutant strain, and the effects of MucD on pqsH transcription were examined. The level of pqsH transcription was not different even when MucD was depleted or overexpressed (Fig. 7A). TLC analysis also indicated that the PQS quantities in the supernatants are not different in these strains (Fig. 7B). However, the localization of PQS was different when the expression level of MucD was altered. The amount of PQS contained in MVs was elevated in the ΔmucD mutant carrying plasmid pUCP24 than in PAO1(pUCP24), while the amount of PQS in MVs was decreased in the WT strain PAO1(pmucD) and the ΔmucD mutant carrying plasmid pmucD (Fig. 7C). In contrast, the PQS amount in the supernatant was high in the strains expressing a high level of MucD (Fig. 7D). These results indicated that MucD regulation of MV production affects PQS localization without changing the quantity of PQS in the supernatant.

FIG. 7.

Effects of MucD on PQS synthesis and localization. (A) C23O activity assays of pqsH transcript levels. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (error bars) from three independent samples. (B to D) Detection of PQS by TLC and UV light. Spot intensity is shown in arbitrary units. PQS/OD600 values are shown compared to the values for the WT strain carrying plasmid pUCP24. PAO1 carrying plasmid pUCP24 or plasmid pmucD and the ΔmucD mutant carrying plasmid pUCP24 (ΔmucD pUCP24) or plasmid pmucD (ΔmucD pmucD) are shown. (B) PQS in supernatants including MVs [Sup. (+MVs)]. The rightmost lane shows synthesized PQS (25 nmol). (C) PQS in MVs. (D) PQS in supernatants without MVs [Sup. (−MVs)].

DISCUSSION

Analysis of Opr86 and MucD provides a useful tool for understanding the effects of misfolded OMPs on phenotypic changes in P. aeruginosa. Since the Omp85/YaeT family, which includes Opr86, is essential for viability and has been difficult to analyze, there has been little study of the relationship between the factor and a physiological phenotype. In E. coli, lipoproteins such as YfgL, YfiO, NlpB, and SmpA exist in a heterooligomeric complex with YaeT and coordinate the overall OM assembly (57, 75). While cells lacking YfgL, NlpB, or SmpA are viable and exhibit only minor OMP assembly defects, YfiO and YaeT are essential, and depletion of these proteins in cells results in severe OMP targeting defects. Previously, we found that depletion of Opr86, which result in OMP assembly defects, causes hypervesiculation (63). Moreover, we showed that overexpression of opr86 results in decreased MV production in this study (Fig. 1B). These data suggest that misfolded OMPs upregulate MV production in P. aeruginosa, and the data correspond to the fact that stress, such as accumulation of toxic misfolded OMPs, causes increased MV synthesis in E. coli and Salmonella enterica (42). We also observed that overexpression of SurA resulted in decreased MV production in P. aeruginosa (unpublished data). It has been reported that SurA is a chaperone responsible for the periplasmic transit of the bulk mass of OMPs to the outer membrane in E. coli (28, 49), but P. aeruginosa SurA has been not characterized. It has also been shown that Skp and DegP play the role of chaperone with OMPs, but the loss of either DegP or Skp has no effect on the outer membrane composition in E. coli (57). We examined the effect of PA3647, which seems to be an E. coli skp homolog, on MV production. Overexpression of this gene did not affect the quantity of MVs in supernatants compared to that in the WT (unpublished data), suggesting that either PA3647 does not operate as a chaperone or it also plays a supplementary role in the mechanism in E. coli. In contrast, overexpression of MucD, which is the DegP homolog in P. aeruginosa, resulted in decreased MV production (Fig. 5). DegP has been shown to have not only chaperone activity but also a periplasmic serine protease that degrades improperly folded or mislocalized OMPs (59, 61), and it is believed that repression of MV production by MucD is attributed to the latter function.

In E. coli, the relationship between MV production and the signaling system, including Bae, Cpx, Psp, and the σE pathway, which monitor bacterial cell envelope systems, has been studied (42). The σE pathway is activated by the binding of DegS to the C-terminal YYF or YQF sequence present on OMPs when accumulation of misfolded OMPs is caused by a stress, such as an elevated temperature (1, 2, 67). Since the periplasmic protein cytochrome b562 fused with C-terminal YYF increased MV production and since it is enriched in MVs (42), it is hypothesized that this C-terminal sequence acts as an inducible signal for MV production. In E. coli, σE pathway regulators, including DegS, RseA, and DegP, act as negative regulators of MV production (42). These three factors, DegS, RseA, and DegP, are homologous to AlgW, MucA, and MucD of P. aeruginosa, respectively. In P. aeruginosa, however, strains with mutations in the sigma factor σ22 pathway, including ΔalgW, ΔalgU, ΔmucA, ΔmucB, and ΔmucD mutants showed different quantities of MV production (Fig. 3A). While DegS and RseA repress MV production in E. coli (42), deletion of algW did not alter MV levels significantly and deletion of mucA resulted in decreased MV levels in P. aeruginosa, suggesting that the mechanism of this pathway in P. aeruginosa is a little different from the σE pathway in E. coli. It is believed that the different mechanism is derived from the gene location: while degP is located in a different position from that of rpoE or rseA in E. coli, mucD is located in algU-mucABCD in P. aeruginosa. We considered the possibility that alteration of MV levels in some alginate synthetic regulators is a consequence of alteration of mucD expression in P. aeruginosa (Fig. 4). In our experiment, mucD expression mostly depended on the algU promoter, although Wood and Ohman previously reported that the mucD-specific promoter leads to about half of the amount of MucD (73). Since we analyzed mucD expression at the transcriptional level, while Wood et al. analyzed it at the translational level, there may be some posttranscriptional regulation. In addition, it is known that MucD (DegP, HtrA) sensitively responds to several stresses, such as osmotic pressure and temperature (2, 71, 73). Therefore, the differences in the growth conditions, such as the medium and growth stage, may have resulted in the different levels of mucD expression.

The relationship between the sigma factor σE pathway and the release of MVs has also been reported in Vibrio cholerae (58). A small regulatory noncoding RNA VrrA, whose expression requires σE activity, positively regulates MV production through downregulation of an outer membrane protein OmpA. Meanwhile, another study reported that activation of the σE pathway causes a rapid downregulation of major omp mRNAs and downregulates the accumulation of misfolded OMPs in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (46). Since the algU deletion caused an increase in MV production in our results, it is possible that the latter regulation exists in P. aeruginosa. Indeed, Wood and Ohman recently reported that small RNAs were upregulated by σ22 activation in P. aeruginosa (74). Further investigation is needed to elucidate the detailed mechanism of MV regulation by σ22.

In P. aeruginosa, it has been shown that PQS is one of the most important factors for releasing MVs by interacting strongly with LPS (38). A proposed model for MV production is that charge-to-charge repulsion between neighboring negatively charged LPS is enhanced by PQS, resulting in curvature of the outer membrane (39). Divalent cations stabilize the gram-negative outer membrane by forming salt bridges between negatively charged phosphates of neighboring LPS molecules. Since several quinolones have been shown to interact with cations (38), PQS probably functions by sequestering positive charge from LPS.

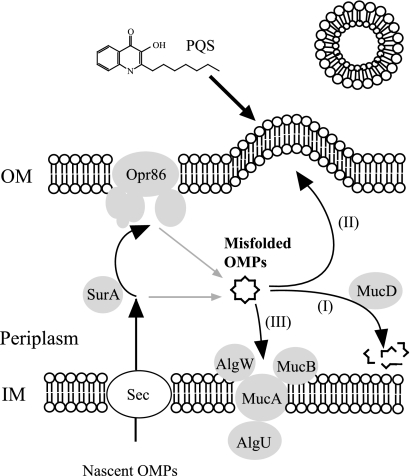

Taking all the results together, MV production seems to be induced by at least two independent processes as shown in Fig. 8. While PQS operates on LPS from outside, misfolded OMPs increase MV proteins from the periplasm. We also propose a model for the presumed process of misfolded OMPs as shown in Fig. 8. It is thought that elimination of misfolded OMPs can be divided into three processes. One is degradation by the serine protease MucD. The second process is the induction of MV production. Accumulation of misfolded OMPs in the periplasm resulting from decreased MucD would cause excretion of misfolded OMPs to the extracellular milieu through MVs and increased MV production. This process in E. coli has been previously reported in a study by McBroom and Kuehn (42). The third process is alginate synthesis. However, it seems that this process is low priority in terms of misfolded OMP elimination. Alginate synthesis usually occurred in small amounts in P. aeruginosa PAO1. Qiu et al. showed that overexpression of MucE, which has a WVF motif in its C-terminal region and is a positive regulator of alginate synthesis to activate AlgU activity, did not change appearance after induction from a lac promoter or a tac promoter (48). However, a higher level of induction by an aaC1 or a PBAD promoter caused mucoid conversion. Therefore, it is believed that a slight fluctuation in the quantity of misfolded OMPs in the periplasm does not affect alginate synthesis.

FIG. 8.

Model of brief MV production and stress response in the periplasm of P. aeruginosa. MV production is enhanced by PQS and misfolded OMPs, and these processes are in independent pathways. Misfolded OMPs accumulate in the periplasm through the decline in function of OMP assembly machinery. Accumulated misfolded OMPs proceed in three processes. To alleviate periplasmic stress, serine protease MucD degrades misfolded OMPs selectively (process I). In another process, misfolded OMPs are released as MVs (process II). According to the level of expression of MucD, MV production changes. When there is an extreme accumulation of misfolded OMPs in the periplasm, alginate synthesis seems to be activated (process III). OM, outer membrane; IM, inner membrane.

In the airways of CF patients, mucoid conversion frequently occurs mostly through mutations in mucA (35). As chronic CF lung disease progresses, mucoid, alginate-overexpressing strains emerge and become the predominant form. Alginate is one of the components in exopolysaccharides in P. aeruginosa biofilms. On the other hand, it has been reported that MVs are also an important particulate component of the matrix of not only P. aeruginosa biofilms but also of mixed bacterial biofilms (52). However, its function in biofilms has not been elucidated. Investigation of the role of MVs in biofilm production should be particularly interesting.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sosaku Ichikawa and Fumiko Yukuhiro for advice and helping with the TEM analysis. We also thank Michael A. Kertesz for providing us with the pME4510 plasmid and Herbert P. Schweizer for providing us with the pUCP24 plasmid.

Y. Tashiro was supported by a Scientific Research fellowship from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences (JSPS) fellowship. This study was supported in part by a Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (grant 21380056) to N. Nomura from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 October 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ades, S. 2008. Regulation by destruction: design of the σE envelope stress response. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:535-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alba, B., and C. Gross. 2004. Regulation of the Escherichia coli sigma-dependent envelope stress response. Mol. Microbiol. 52:613-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauman, S., and M. Kuehn. 2009. Pseudomonas aeruginosa vesicles associate with and are internalized by human lung epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 9:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauman, S., and M. Kuehn. 2006. Purification of outer membrane vesicles from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their activation of an IL-8 response. Microbes Infect. 8:2400-2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beveridge, T. J. 1999. Structures of gram-negative cell walls and their derived membrane vesicles. J. Bacteriol. 181:4725-4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beveridge, T. J., and J. Kadurugamuwa. 1996. Periplasm, periplasmic spaces, and their relation to bacterial wall structure: novel secretion of selected periplasmic proteins from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb. Drug Resist. 2:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bomberger, J., D. Maceachran, B. Coutermarsh, S. Ye, G. O'Toole, and B. Stanton. 2009. Long-distance delivery of bacterial virulence factors by Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane vesicles. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boucher, J., J. Martinez-Salazar, M. Schurr, M. Mudd, H. Yu, and V. Deretic. 1996. Two distinct loci affecting conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis encode homologs of the serine protease HtrA. J. Bacteriol. 178:511-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boucher, J., M. Schurr, H. Yu, D. Rowen, and V. Deretic. 1997. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: role of mucC in the regulation of alginate production and stress sensitivity. Microbiology 143:3473-3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradford, M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Button, J. E., T. J. Silhavy, and N. Ruiz. 2007. A suppressor of cell death caused by the loss of σE downregulates extracytoplasmic stress responses and outer membrane vesicle production in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 189:1523-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costerton, J., P. Stewart, and E. Greenberg. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies, D., A. Chakrabarty, and G. Geesey. 1993. Exopolysaccharide production in biofilms: substratum activation of alginate gene expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1181-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Déziel, E., S. Gopalan, A. Tampakaki, F. Lépine, K. Padfield, M. Saucier, G. Xiao, and L. Rahme. 2005. The contribution of MvfR to Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis and quorum sensing circuitry regulation: multiple quorum sensing-regulated genes are modulated without affecting lasRI, rhlRI or the production of N-acyl-L-homoserine lactones. Mol. Microbiol. 55:998-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doerrler, W., and C. Raetz. 2005. Loss of outer membrane proteins without inhibition of lipid export in an Escherichia coli YaeT mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 280:27679-27687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flynn, J., and D. E. Ohman. 1988. Cloning of genes from mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa which control spontaneous conversion to the alginate production phenotype. J. Bacteriol. 170:1452-1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flynn, J., and D. E. Ohman. 1988. Use of a gene replacement cosmid vector for cloning alginate conversion genes from mucoid and nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains: algS controls expression of algT. J. Bacteriol. 170:3228-3236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garrett, E., D. Perlegas, and D. Wozniak. 1999. Negative control of flagellum synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is modulated by the alternative sigma factor AlgT (AlgU). J. Bacteriol. 181:7401-7404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg, J., W. Gorman, J. Flynn, and D. E. Ohman. 1993. A mutation in algN permits trans activation of alginate production by algT in Pseudomonas species. J. Bacteriol. 175:1303-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hays, E. E., I. C. Wells, P. A. Katzman, C. K. Cain, F. A. Jacobs, S. A. Thayer, E. A. Doisy, W. L. Gaby, E. C. Roberts, R. D. Muir, C. J. Carroll, L. R. Jones, and N. J. Wade. 1945. Antibiotic substances produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 159:725-750. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holloway, B., V. Krishnapillai, and A. Morgan. 1979. Chromosomal genetics of Pseudomonas. Microbiol. Rev. 43:73-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horstman, A., and M. Kuehn. 2000. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli secretes active heat-labile enterotoxin via outer membrane vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 275:12489-12496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kadurugamuwa, J., and T. J. Beveridge. 1996. Bacteriolytic effect of membrane vesicles from Pseudomonas aeruginosa on other bacteria including pathogens: conceptually new antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 178:2767-2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadurugamuwa, J., and T. J. Beveridge. 1999. Membrane vesicles derived from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Shigella flexneri can be integrated into the surfaces of other gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology 145:2051-2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kadurugamuwa, J., and T. J. Beveridge. 1995. Virulence factors are released from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in association with membrane vesicles during normal growth and exposure to gentamicin: a novel mechanism of enzyme secretion. J. Bacteriol. 177:3998-4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadurugamuwa, J., A. Mayer, P. Messner, M. Sára, U. Sleytr, and T. J. Beveridge. 1998. S-layered Aneurinibacillus and Bacillus spp. are susceptible to the lytic action of Pseudomonas aeruginosa membrane vesicles. J. Bacteriol. 180:2306-2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessler, E., M. Safrin, J. Olson, and D. E. Ohman. 1993. Secreted LasA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a staphylolytic protease. J. Biol. Chem. 268:7503-7508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazar, S., and R. Kolter. 1996. SurA assists the folding of Escherichia coli outer membrane proteins. J. Bacteriol. 178:1770-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, Z., A. Clarke, and T. J. Beveridge. 1996. A major autolysin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: subcellular distribution, potential role in cell growth and division, and secretion in surface membrane vesicles. J. Bacteriol. 178:2479-2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, Z., A. Clarke, and T. J. Beveridge. 1998. Gram-negative bacteria produce membrane vesicles which are capable of killing other bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 180:5478-5483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loosmore, S., Y. Yang, D. Coleman, J. Shortreed, D. England, and M. Klein. 1997. Outer membrane protein D15 is conserved among Haemophilus influenzae species and may represent a universal protective antigen against invasive disease. Infect. Immun. 65:3701-3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacEachran, D., S. Ye, J. Bomberger, D. Hogan, A. Swiatecka-Urban, B. Stanton, and G. O'Toole. 2007. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa secreted protein PA2934 decreases apical membrane expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Infect. Immun. 75:3902-3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malinverni, J., J. Werner, S. Kim, J. Sklar, D. Kahne, R. Misra, and T. J. Silhavy. 2006. YfiO stabilizes the YaeT complex and is essential for outer membrane protein assembly in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 61:151-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin, D., M. Schurr, M. Mudd, and V. Deretic. 1993. Differentiation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa into the alginate-producing form: inactivation of mucB causes conversion to mucoidy. Mol. Microbiol. 9:497-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin, D., M. Schurr, M. Mudd, J. Govan, B. Holloway, and V. Deretic. 1993. Mechanism of conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting cystic fibrosis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8377-8381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maseda, H., I. Sawada, K. Saito, H. Uchiyama, T. Nakae, and N. Nomura. 2004. Enhancement of the mexAB-oprM efflux pump expression by a quorum-sensing autoinducer and its cancellation by a regulator, MexT, of the mexEF-oprN efflux pump operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1320-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mashburn, L., and M. Whiteley. 2005. Membrane vesicles traffic signals and facilitate group activities in a prokaryote. Nature 437:422-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mashburn-Warren, L., J. Howe, P. Garidel, W. Richter, F. Steiniger, M. Roessle, K. Brandenburg, and M. Whiteley. 2008. Interaction of quorum signals with outer membrane lipids: insights into prokaryotic membrane vesicle formation. Mol. Microbiol. 69:491-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mashburn-Warren, L., and M. Whiteley. 2006. Special delivery: vesicle trafficking in prokaryotes. Mol. Microbiol. 61:839-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mathee, K., C. McPherson, and D. E. Ohman. 1997. Posttranslational control of the algT (algU)-encoded σ22 for expression of the alginate regulon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and localization of its antagonist proteins MucA and MucB (AlgN). J. Bacteriol. 179:3711-3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McBroom, A., A. Johnson, S. Vemulapalli, and M. Kuehn. 2006. Outer membrane vesicle production by Escherichia coli is independent of membrane instability. J. Bacteriol. 188:5385-5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McBroom, A., and M. Kuehn. 2007. Release of outer membrane vesicles by Gram-negative bacteria is a novel envelope stress response. Mol. Microbiol. 63:545-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Misra, R. 2007. First glimpse of the crystal structure of YaeT's POTRA domains. ACS Chem. Biol. 2:649-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakao, R., Y. Tashiro, N. Nomura, S. Kosono, K. Ochiai, H. Yonezawa, H. Watanabe, and H. Senpuku. 2008. Glycosylation of the OMP85 homolog of Porphyromonas gingivalis and its involvement in biofilm formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 365:784-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen, T., A. Saxena, and T. J. Beveridge. 2003. Effect of surface lipopolysaccharide on the nature of membrane vesicles liberated from the Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Electron Microsc. (Tokyo) 52:465-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papenfort, K., V. Pfeiffer, F. Mika, S. Lucchini, J. Hinton, and J. Vogel. 2006. SigmaE-dependent small RNAs of Salmonella respond to membrane stress by accelerating global omp mRNA decay. Mol. Microbiol. 62:1674-1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pesci, E., J. Milbank, J. Pearson, S. McKnight, A. Kende, E. P. Greenberg, and B. Iglewski. 1999. Quinolone signaling in the cell-to-cell communication system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11229-11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qiu, D., V. Eisinger, D. Rowen, and H. Yu. 2007. Regulated proteolysis controls mucoid conversion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:8107-8112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rouvière, P., and C. Gross. 1996. SurA, a periplasmic protein with peptidyl-prolyl isomerase activity, participates in the assembly of outer membrane porins. Genes Dev. 10:3170-3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ryder, C., M. Byrd, and D. Wozniak. 2007. Role of polysaccharides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:644-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schleiff, E., and J. Soll. 2005. Membrane protein insertion: mixing eukaryotic and prokaryotic concepts. EMBO Rep. 6:1023-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schooling, S., and T. J. Beveridge. 2006. Membrane vesicles: an overlooked component of the matrices of biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 188:5945-5957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schurr, M., H. Yu, J. Martinez-Salazar, J. Boucher, and V. Deretic. 1996. Control of AlgU, a member of the σE-like family of stress sigma factors, by the negative regulators MucA and MucB and Pseudomonas aeruginosa conversion to mucoidy in cystic fibrosis. J. Bacteriol. 178:4997-5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simon, R., M. O'Connell, M. Labes, and A. Pühler. 1986. Plasmid vectors for the genetic analysis and manipulation of rhizobia and other gram-negative bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 118:640-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh, P., A. Schaefer, M. Parsek, T. Moninger, M. Welsh, and E. P. Greenberg. 2000. Quorum-sensing signals indicate that cystic fibrosis lungs are infected with bacterial biofilms. Nature 407:762-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sklar, J., T. Wu, L. Gronenberg, J. Malinverni, D. Kahne, and T. J. Silhavy. 2007. Lipoprotein SmpA is a component of the YaeT complex that assembles outer membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:6400-6405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sklar, J., T. Wu, D. Kahne, and T. J. Silhavy. 2007. Defining the roles of the periplasmic chaperones SurA, Skp, and DegP in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 21:2473-2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Song, T., F. Mika, B. Lindmark, Z. Liu, S. Schild, A. Bishop, J. Zhu, A. Camilli, J. Johansson, J. Vogel, and S. Wai. 2008. A new Vibrio cholerae sRNA modulates colonization and affects release of outer membrane vesicles. Mol. Microbiol. 70:100-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spiess, C., A. Beil, and M. Ehrmann. 1999. A temperature-dependent switch from chaperone to protease in a widely conserved heat shock protein. Cell 97:339-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stewart, J. 1980. Colorimetric determination of phospholipids with ammonium ferrothiocyanate. Anal. Biochem. 104:10-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strauch, K., K. Johnson, and J. Beckwith. 1989. Characterization of degP, a gene required for proteolysis in the cell envelope and essential for growth of Escherichia coli at high temperature. J. Bacteriol. 171:2689-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tart, A., M. Wolfgang, and D. Wozniak. 2005. The alternative sigma factor AlgT represses Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellum biosynthesis by inhibiting expression of fleQ. J. Bacteriol. 187:7955-7962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tashiro, Y., N. Nomura, R. Nakao, H. Senpuku, R. Kariyama, H. Kumon, S. Kosono, H. Watanabe, T. Nakajima, and H. Uchiyama. 2008. Opr86 is essential for viability and is a potential candidate for a protective antigen against biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 190:3969-3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Toyofuku, M., N. Nomura, T. Fujii, N. Takaya, H. Maseda, I. Sawada, T. Nakajima, and H. Uchiyama. 2007. Quorum sensing regulates denitrification in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 189:4969-4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toyofuku, M., N. Nomura, E. Kuno, Y. Tashiro, T. Nakajima, and H. Uchiyama. 2008. Influence of the Pseudomonas quinolone signal on denitrification in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 190:7947-7956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Voulhoux, R., M. Bos, J. Geurtsen, M. Mols, and J. Tommassen. 2003. Role of a highly conserved bacterial protein in outer membrane protein assembly. Science 299:262-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Walsh, N., B. Alba, B. Bose, C. Gross, and R. Sauer. 2003. OMP peptide signals initiate the envelope-stress response by activating DegS protease via relief of inhibition mediated by its PDZ domain. Cell 113:61-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Werner, J., and R. Misra. 2005. YaeT (Omp85) affects the assembly of lipid-dependent and lipid-independent outer membrane proteins of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1450-1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.West, S., H. Schweizer, C. Dall, A. Sample, and L. Runyen-Janecky. 1994. Construction of improved Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19 and sequence of the region required for their replication in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 148:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whitchurch, C., T. Tolker-Nielsen, P. Ragas, and J. Mattick. 2002. Extracellular DNA required for bacterial biofilm formation. Science 295:1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wonderling, L., B. Wilkinson, and D. Bayles. 2004. The htrA (degP) gene of Listeria monocytogenes 10403S is essential for optimal growth under stress conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1935-1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wood, L., A. Leech, and D. E. Ohman. 2006. Cell wall-inhibitory antibiotics activate the alginate biosynthesis operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: roles of sigma (AlgT) and the AlgW and Prc proteases. Mol. Microbiol. 62:412-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wood, L., and D. E. Ohman. 2006. Independent regulation of MucD, an HtrA-like protease in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and the role of its proteolytic motif in alginate gene regulation. J. Bacteriol. 188:3134-3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wood, L., and D. E. Ohman. 2009. Use of cell wall stress to characterize sigma 22 (AlgT/U) activation by regulated proteolysis and its regulon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 72:183-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wozniak, D., T. Wyckoff, M. Starkey, R. Keyser, P. Azadi, G. O'Toole, and M. Parsek. 2003. Alginate is not a significant component of the extracellular polysaccharide matrix of PA14 and PAO1 Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:7907-7912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu, T., J. Malinverni, N. Ruiz, S. Kim, T. J. Silhavy, and D. Kahne. 2005. Identification of a multicomponent complex required for outer membrane biogenesis in Escherichia coli. Cell 121:235-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang, Y., W. Thomas, P. Chong, S. Loosmore, and M. Klein. 1998. A 20-kilodalton N-terminal fragment of the D15 protein contains a protective epitope(s) against Haemophilus influenzae type a and type b. Infect. Immun. 66:3349-3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yorgey, P., L. Rahme, M. Tan, and F. Ausubel. 2001. The roles of mucD and alginate in the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in plants, nematodes and mice. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1063-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]