Abstract

Clostridium difficile has been identified as the most important single identifiable cause of nosocomial antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis. Virulent strains of C. difficile produce two large protein toxins, toxin A and toxin B, which are involved in pathogenesis. In this study, we examined the effect of lysogeny by ΦCD119 on C. difficile toxin production. Transcriptional analysis demonstrated a decrease in the expression of pathogenicity locus (PaLoc) genes tcdA, tcdB, tcdR, tcdE, and tcdC in ΦCD119 lysogens. During this study we found that repR, a putative repressor gene of ΦCD119, was expressed in C. difficile lysogens and that its product, RepR, could downregulate tcdA::gusA and tcdR::gusA reporter fusions in Escherichia coli. We cloned and purified a recombinant RepR containing a C-terminal six-His tag and documented its binding to the upstream regions of tcdR in C. difficile PaLoc and in repR upstream region in ΦCD119 by gel shift assays. DNA footprinting experiments revealed similarities between the RepR binding sites in tcdR and repR upstream regions. These findings suggest that presence of a CD119-like temperate phage can influence toxin gene regulation in this nosocomially important pathogen.

Clostridium difficile, a gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-forming bacterium, has been identified as one of the major causative agents of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudo-membranous colitis. C. difficile produces toxins A and B that damage intestinal mucosa and cause fluid accumulation in the colon (1). The toxin genes tcdA and tcdB, along with accessory genes tcdR, tcdC, and tcdE, are part of a 19.6-kb pathogenicity locus (PaLoc). Toxin genes tcdA and tcdB are positively regulated by TcdR (previously TxeR) (27), and tcdC is involved in the negative regulation of toxin genes (16, 29). In pathogenic C. difficile strains, the PaLoc is present at identical locations in the chromosome, whereas it is completely absent in nontoxinogenic strains. This observation has led to the suggestion that the presence of the toxin gene cluster may be associated with a transposable genetic element (3). In other clostridial species, toxins are known to be encoded by mobile genetic elements such as bacteriophages and plasmids (6, 9, 10, 31).

Following publication of the genome of ΦCD119 (15), the genome of a second C. difficile temperate phage (ΦC2, a member of the Myoviridae) was published (13). More recently, eight temperate phages were characterized from six different C. difficile isolates, including the hypervirulent strain responsible for a multi-institutional outbreak (NAP1/027 or QCD-32g58) (11). In addition, the multidrug-resistant C. difficile strain CD630 was found to harbor two highly related prophages (13, 39) as part of its mosaic genome, where nearly 11% is made of mobile genetic elements. Thus, it appears that C. difficile strains often harbor temperate phage(s) as part of their genetic makeup. No direct evidence of lysogenic conversion of a nontoxinogenic C. difficile strain to toxin production was shown. However, preliminary results showed that toxin A and/or toxin B production is modified in a toxigenic C. difficile lysogen (12). In our lab we have successfully used a C. difficile phage for treating C. difficile-associated disease in hamster models (37). Later, we characterized and presented the first complete C. difficile phage genome (15). During these studies it was found that ΦCD119 could modulate toxin production in its C. difficile host strains. Hence, we have conducted a detailed study on the effect of lysogenization by this temperate phage on toxin production in C. difficile and characterized the role of phage-encoded protein RepR on transcriptional regulation of the PaLoc genes. This is the first evidence demonstrating the role of a temperate phage in virulence gene regulation in C. difficile.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. difficile growth conditions, phage propagation, and purification.

The C. difficile strains were stored in chopped meat broth (Carr Scarborough Microbiologicals, Inc., Decatur, GA) at room temperature. When required, the broth cultures were subcultured onto brain heart infusion agar and incubated anaerobically at 37°C. Bacteriophage was induced as described by Mahony et al. (26), propagated, and purified according to methods described previously (15).

Generating ΦCD119 lysogens.

The C. difficile ΦCD119 lysogen F10 and the ΦCD119 host C. difficile strains 602, 660, and 460 were obtained from Rosanna Dei, Universitá degli Studi di Firenze, Italy. Bacteriophage ΦCD119 was induced by mitomycin C treatment from ΦCD119 lysogen F10 and was isolated by techniques described by Mahony et al. (26). ΦCD119 (1 × 109 PFU) was spotted on a lawn of C. difficile strains 602, 660, or 460 on brain heart infusion agar plates and incubated overnight at 37°C, under anaerobic conditions. Bacterial colonies within the lysis zone were isolated and tested for phage production following mitomycin C (10 μg ml−1) treatment. Putative lysogens were confirmed by probing their genomic DNA with α-32P-labeled ΦCD119 DNA. Three ΦCD119 lysogens were isolated in each host C. difficile strain and were named after their parental isolate number, followed by an alphabetical character with a phage sign (e.g., 602ΦA, 602ΦB, and 602ΦC are the three individually isolated lysogens derived from strain 602).

Toxin A assay.

Toxin A was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit from Meridian Diagnostics Inc., Cincinnati, OH. Bacterial cultures were harvested at different time points from C. difficile strains by centrifugation and were resuspended in Tris buffer (0.05 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). The cytosolic contents of the harvested cells were obtained by sonication followed by brief centrifugation. Equal amounts of cytosolic proteins were taken, and their relative toxin A content was determined using an ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's directions. Tris buffer (0.05 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) alone was used as a negative control.

Reverse transcriptase PCR.

Total RNA was prepared from C. difficile cultures using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). After DNase treatment for 30 min at 37°C, the RNA was cleaned with RNeasy columns and was checked for DNA contamination by PCR. The cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of DNA-free RNA and random hexamer primers and employing a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit for reverse transcription-PCR (using avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase) from Roche Biochemicals (Indiana). The synthesized cDNA and the gene-specific primers (Table 1) were used in the subsequent PCRs. Except for tcdC, all transcriptional analyses were performed using RNA extracted from 16-h-old C. difficile cultures. For tcdC analysis RNA was extracted from a culture of C. difficile grown for 8 h.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers used for reverse transcription-PCR

| Gene name | Primer |

|

|---|---|---|

| Direction | Sequence(5′ to 3′) | |

| tcdA | Forward | GCAGCTACTGGATGGCAAAC |

| Reverse | ATCTCGAAAAGTCCACCAGC | |

| tcdB | Forward | TCATTTGACGATGCAAGAGC |

| Reverse | CCTTTCCTCAACAATTTGCG | |

| tcdR | Forward | TCAAAGTAAGTCTGTTTTTGAGGAA |

| Reverse | TGCTCTATTTTTAGCCTTATTAACAGC | |

| tcdC | Forward | GGTTCAAAATGAAAGACGACG |

| Reverse | GCACCTCATCACCATCTTCA | |

| tcdE | Forward | TGGAGGAATCAGAAAAGTAGCA |

| Reverse | CATTTCATCTGTCATTGCATCT | |

| 16SrRNA | Forward | ACACGGTCCAAACTCCTACG |

| Reverse | AGGCGAGTTTCAGCCTACAA | |

| int | Forward | ATGAATATCAAATCAGCTTTTAT |

| Reverse | TGAATAAATACTCCCATGTACTT | |

| repR | Forward | CTGTCATCATCATTGAGAGAATA |

| Reverse | GGGAAAGTGATAGAAGATTTCCT | |

| CD2693 | Forward | GTGCCCAAACTAATCATCGG |

| Reverse | GCTAACATTCCTGCCTCTGG | |

| CD2694 | Forward | AAAATGCTAAATTTGGTTTGT |

| Reverse | CTCCAAATTAAAACTATAGCATCA | |

Expression of six-His tagged ΦCD119 repressor.

The PCR was used to amplify repR from ΦCD119 DNA. DNA was isolated from purified bacteriophage with a High Pure Lambda Isolation Kit (Roche). The repR coding sequence was cloned into pET22b (Novagen), such that it was under the T7 promoter and contained a C-terminal six-histidine tag, employing primers containing NdeI and BamHI (Forward, 5′-GTCGCATATGACTAACACATTTGGAAAC-3′; Reverse, 5′-CCGGGGATCCATTCTCTTCTTTCTTCG-3′). The cloned repR was verified by DNA sequence analysis, and the recombinant vector (pETRepR) was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus(DE3) strain (Stratagene), carrying the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible T7 RNA polymerase. The transformants were grown to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.5) before inducing repR expression (0.5 mM IPTG). After 2 h of induction, the cells were harvested and lysed by sonication. The presence of RepR with a His6 tag was detected by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot analysis employing anti-His6 antibodies (Invitrogen). The ΦCD119 genome sequence and repressor protein sequence can be found in the GenBank under accession numbers AY855346 and AAX53417, respectively.

Reporter fusion plasmids for E. coli.

Plasmids pTUM512, pTUM515, pTUM521, and pTUM525 were the kind gift of A. L. Sonenshein of Tufts University. Plasmids pTUM512 and pTUM515 carry the tcdA upstream (527 bp from translational start) and tcdR upstream (511 bp from the translational start) fused in frame with the E. coli gusA gene, respectively. Plasmids pTUM521 and pTUM525 carry the same respective promoter fusions along with the tcdR gene (28). Reporter constructs from pTUM512, pTUM515, pTUM521, and pTUM525 were excised with SalI-EagI digestion, and fragments were subcloned into the pACYC184 vector, resulting in the construction of pACYC512, pACYC515, pACYC521, and pACYC525, respectively (Table 2). To construct the gdh-gusA fusion, the gdh promoter region was PCR amplified from C. difficile chromosomal DNA using primers gdhF (GGATCCTAGCTGGGATATCGGC, with BamHI) and gdhR (TCTAGAAAAGCCCCCTTATAAA, with XbaI) and was cloned in pGEMT Easy vector (Promega) to create pGEM-gdh. The gusA gene was excised from pTUM515 using XbaI and PstI and was subsequently cloned in pGEM-gdh to create pGEM (gdh-gusA). The gdh-gusA fusion was then excised from pGEM (gdh-gusA) using BamHI and SalI and cloned in pACYC184 digested with the same enzymes to create pACYC528.

TABLE 2.

E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study

| E. coli strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| BL21-codon plus (DE3) | Host for pET expression system | Stratagene |

| GM241 | gusA mutant | 33 |

| GM241(DE3) | gusA mutant lysogenized with λDE3 phage and host for gusA reporter plasmids | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pET22-b | Cloning vector; T7 expression system; C-terminal His tag; Cbr | Novagen |

| pETRepR | Plasmid carrying repR under inducible T7 promoter; Cbr | This Study |

| pTUM512 | tcdA promoter-gusA fusion; Cbr | Sonenshein laboratory, Tufts University |

| pTUM515 | tcdR promoter-gusA fusion; Cbr | Sonenshein laboratory, Tufts University |

| pTUM521 | tcdA promoter-gusA fusion and tcdR structural gene; Cbr | 28 |

| pTUM525 | tcdR promoter-gusA fusion and tcdR structural gene; Cbr | 28 |

| pACYC184 | Cloning vector with p15A origin of replication; coexists with plasmids that use colE1 origin; Tetr Cmr | New England Biolabs |

| pACYC512 | SalI-EagI fragment from pTUM512 cloned in pACYC184; Cmr | This study |

| pACYC515 | SalI-EagI fragment from pTUM515 cloned in pACYC184; Cmr | This study |

| pACYC521 | SalI-EagI fragment from pTUM521 cloned in pACYC184; Cmr; carries tcdR structural gene | This study |

| pACYC525 | SalI-EagI fragment from pTUM525 cloned in pACYC184; Cmr; carries tcdR structural gene | This study |

| pACYC528 | tcdA promoter in pACYC515 was replaced with gdh promoter; Cmr | This study |

E. coli reporter strains for β-glucuronidase assays.

The E. coli gusA mutant, GM241 (33), was obtained from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center (Yale University, CT) and lysogenized with λDE3 to create the GM241 (DE3) strain (Table 2) to facilitate expression of repR cloned under the T7 promoter in a pET22-b vector (Novagen). DE3 λ phage carries an IPTG-inducible T7 RNA polymerase gene, and lysogenization with DE3 λ facilitates the expression of repR cloned in the pET vector under the control of the T7 promoter. To measure the effect of RepR on the expression of the tcdR, tcdA, and gdh promoters, plasmids (Table 2) pACYC512, pACYC515, pACYC525, pACYC521, and pACYC528 carrying gusA reporter fusions were introduced into E. coli strain GM241 (DE3) carrying either pETRepR or vector pET22-b. GM241 (DE3) transformants were grown in Luria-Bertani broth for 1 h, and then IPTG was added at a 0.5 mM final concentration for inducing the expression of RepR from the T7 promoter. Culture samples were removed at regular time intervals for up to 24 h following IPTG induction, and the amount of β-glucuronidase activity was assessed as described by Mani et al., with minor modifications (28). Cells were washed and suspended in 0.8 ml of Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4·7H2O [pH 7.0], 40 mM NaH2PO4·H2O, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), and it was permeabilized with 50 μl of 0.1% SDS plus chloroform. The enzyme reaction was started by the addition of 0.16 ml of 6 mM p-nitrophenyl β-d-glucuronide (Sigma) and stopped by the addition of 0.4 ml of 1.0 M NaHCO3. β-Glucuronidase activity units were calculated as described before by Dupuy and Sonenshein (8).

Purification of RepR-His6 protein.

To purify RepR-His6, a 1-liter culture of the BL21-CodonPlus(DE3) strain carrying pETRepR was grown at 37°C for 4 h in the presence of IPTG (0.5 mM). The cells were harvested by centrifugation (13,000 × g), resuspended in 20 ml of buffer A (50 mM sodium-phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole), and lysed by sonication and the cell debris was removed by centrifugation (14,000 × g). The supernatant was loaded on a 5-ml Ni++ Sepharose column (Amersham Biosciences) and washed with buffer A. RepR was eluted sequentially with buffer B (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl) containing imidazole at concentrations of 50 mM, 100 mM, and 150 mM and analyzed for purity by SDS-PAGE. Fractions with RepR were pooled, dialyzed against water, and lyophilized. Protein concentration was measured by the Bradford method (2).

Gel mobility shift experiments.

Sequences upstream of tcdR and repR were amplified by PCR, with the primer pair TXR2 (5′-TAATGATGCTTTATTTGAAAATTTTG-3′) and TXR3 (5′-TTATTGACTAAATTATAAAGTTTC-3′) and the pair REP1 (5′-AGTCATAGTATTCACCTTCCGTTTTT-3′) and REP2 (5′-TCAACTCCTTTTGTTTTCATTTTGCT-3′), respectively, and labeled with biotin using a 3′ biotin end-labeling kit (Pierce), following the manufacturer's recommendations. DNA binding with RepR protein was performed using a LightShift Chemiluminescent electrophoretic mobility shift assay kit (Pierce) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, binding reactions with 10 picomoles of biotinylated DNA targets were performed with different concentrations of purified RepR protein in 20-μl reaction mixtures in 1× buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol at pH 7.5) supplemented with 50 ng/μl poly(dI-dC) and 10% glycerol. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature, binding reaction mixtures were loaded onto 8% polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. After electrophoresis, the reaction mixtures were transferred from the gel onto a nylon membrane using a Bio-Rad minigel wet transfer system at 380 mA for 30 min. The DNA was cross-linked with UV (at 312 nm) for 10 to 15 min with the membrane face down on a transilluminator. The biotin-labeled DNA was detected using streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate as per the manufacturer's instructions. The amount (moles) of purified RepR used in the binding reaction mixtures was calculated based on the molecular size of monomer RepR.

DNA footprinting experiments.

Upstream regions of repR and tcdR were PCR amplified using specific primers. For repR upstream regions, the REP1 (see above) forward phosphorylated primer and the reverse REP3 (5′-CTTAATTATAGTTAACATTTTGCTAAC-3′) primer were used. For the tcdR upstream region, the forward TXR2 primer (see above) and the reverse phosphorylated primer TXR4 (5′-TGTTTTTACAATACTTTATTAATATAAAG-3′) were used. The amplified products were gel extracted and end labeled with γ-32P using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Approximately 20,000 cpm of the labeled probe was used in each reaction mixture, and the footprinting experiments were carried out as per the instructions of the Core Footprinting System (Promega). The RepR binding reactions were performed at room temperature in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 100 mM KCl, 12.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 20% glycerol) for 10 min. Fifty microliters of Ca2/Mg2 solution (5 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM MgCl2) and 3 U of RQ1 DNase were then added, and the mixture was incubated for 1 min. Following digestion, the DNA was precipitated, resuspended in 4 μl of sequencing gel loading buffer (38), heated to 80°C for 5 min, and separated in a 9% polyacrylamide gel with 7 M urea. For the markers, Maxam-Gilbert G+A sequencing reactions were performed on the PCR-amplified products (30).

RESULTS

Effect of ΦCD119 infection on toxin production in C. difficile.

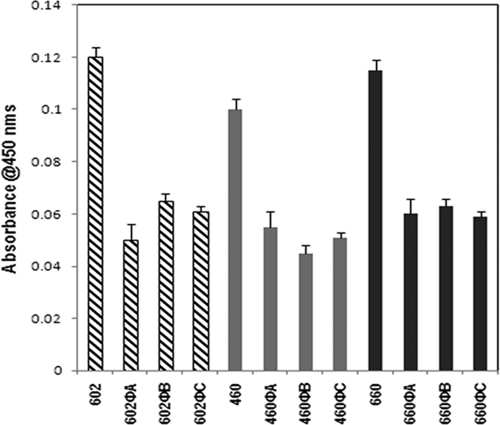

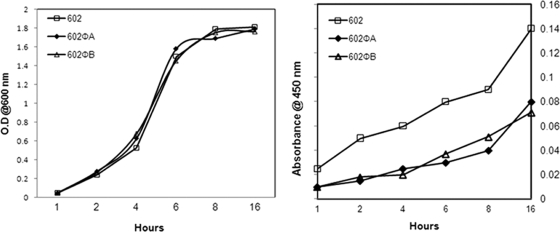

Our preliminary studies suggested that lysogenization of ΦCD119 could modulate toxin production in C. difficile (R. Govind and J. A. Fralick, unpublished data). To understand whether this effect is strain specific, we tested toxin production in ΦCD119 lysogens derived from three different C. difficile strains, 602, 660, and 460. Cytosolic proteins from the lysogens and their respective parent strains were harvested from overnight cultures, and the relative amount of toxin A was determined by ELISA. Tris buffer used for the protein preparation was used as a negative control in the ELISAs, and it recorded zero absorbance. In all three backgrounds the ΦCD119 lysogens produced approximately 50% less toxin A than their respective parent strains (Fig. 1). These results suggest that the effect of ΦCD119 lysogenization on C. difficile is not strain specific. For further analyses on the effect of ΦCD119 lysogenization on toxin production, we selected two lysogens derived from the strain 602, 602ΦA, and 602ΦB. We compared toxin A production of 602ΦA and 602ΦB lysogens with their parent (602) throughout their growth cycles. It was found that the rates of cell growth are similar in lysogens and the parent strain (Fig. 2). However, the relative amount of toxin A per OD600 in the lysogens was consistently less than that present in the parent throughout the growth cycle (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Toxin A titers, expressed as absorbance units, were determined by ELISA. Toxin A production in overnight cultures of ΦCD119 lysogens was compared to parental strains. The ELISA signal was recorded as absorbance at 450 nm relative to the background signal, and the data shown are the mean plus standard error of three replicative samples. Experiments were repeated three times, and the figure represents the data from a single experiment.

FIG. 2.

Toxin A production in the C. difficile 602 parent strain and the lysogens 602ΦA and 602ΦB at different time points in the growth cycle. (Left) Growth curve. (Right) Toxin A ELISA.

Transcriptional analyses in ΦCD119 lysogens.

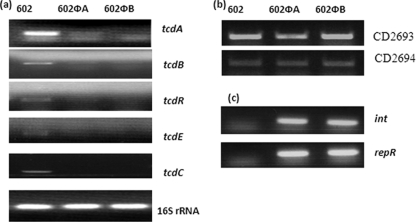

Using reverse transcriptase PCR, transcriptional analyses of different genes were performed with strain 602 and the 602Φ lysogens. To determine the effect of ΦCD119 lysogenization on the regulation of the pathogenicity loci of C. difficile, we compared the transcription of all five genes of the PaLoc. Several studies (8, 18, 23, 35) have shown increased toxin production at the end of exponential growth phase, and hence we prepared RNA from the overnight cultures (16 h old) for transcription analysis. RNA from an 8-h culture was used to analyze tcdC transcription, a stage at which it was found to be transcribed (18). The transcripts of tcdA, tcdB, tcdR, tcdE, and tcdC were found to be downregulated in the lysogens compared with the parent strain (Fig. 3a). Among the toxin genes, tcdA was transcribed at a higher rate than tcdB in the parent strain, supporting an earlier observation that the difference in tcdA and tcdB mRNA levels was approximately twofold (8). Equal levels of 16S rRNA were amplified from both the lysogens and the parent and served as internal controls. In our previous study we defined the integration site of ΦCD119 to be present between C. difficile genes CD2693 and CD2694 (15). The integration site of ΦCD119 in between genes CD2693 and CD2694 was confirmed through PCR in lysogens 602ΦA and 602ΦB (data not shown). We then examined the effect of the integration of ΦCD119 on the expression of host genes CD2693 and CD2694 that are present on either side of the prophage ΦCD119 in lysogens. The transcripts of both of these genes were found to be unaffected by lysogenization with ΦCD119 (Fig. 3b), suggesting that the effect of ΦCD119 lysogenization on C. difficile PaLoc expression is specific for the PaLoc.

FIG. 3.

Reverse transcriptase PCR analyses of (a) PaLoc genes (a), C. difficile genes near the integration site of the phage (b), and ΦCD119 genes (c) in strains 602 (parent), 602ΦA, and 602ΦB. 16S rRNA was used as a control.

We cloned, sequenced, and annotated the genome of the ΦCD119 (15) and identified several open reading frames ([ORFs] ORF44, ORF45, and ORF46) which code for putative transcriptional regulators. Of these ORFs, only ORF44 is transcribed in ΦCD119 lysogens along with the gene that encodes integrase, int (Fig. 3c) (15). ORF 44 (repR) contains an N-terminal helix-turn-helix domain (IPR001387), which belongs to the XRE family of repressors (25). Similar to many other prophages, repR and int may be involved in the maintenance of lysogeny of ΦCD119 in C. difficile.

RepR represses tcdA and tcdR expression in E. coli.

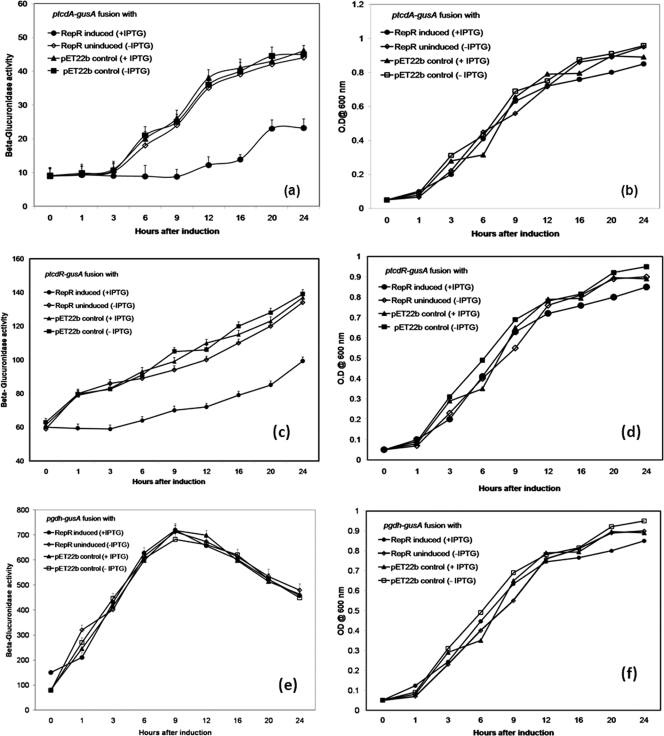

Since we found that repR is expressed in ΦCD119 lysogens and that the PaLoc genes are downregulated in ΦCD119 lysogens, we examined the effect of RepR on toxin gene regulation. To accomplish this, we measured the effect of RepR on the expression of the tcdA-gusA and tcdR-gusA promoter fusions in E. coli. Initially, we transformed the gusA mutant E. coli strain GM241 (DE3) carrying either tcdA-gusA (pACY512) or tcdR-gusA (pACY515) with pET22b and tested for β-glucuronidase activity and found that the activity was below detectable levels (data not shown). These results suggested that the tcdA and tcdR promoters in pACYC512 and pACYC515 were not active in E. coli strain GM241 (λDE3) due to the absence of TcdR, the positive regulator. In 1997, Moncrief et al. provided the first evidence for a positive role of TcdR in toxin gene regulation using a reporter fusion in E. coli (32). These results were confirmed by similar experiments using Clostridium perfringens (27) and later in C. difficile (28). Our results are in agreement with these previous observations and justify the use of E. coli strain GM241 (λDE3) for studying tcdA and tcdR promoter activity. After these initial studies, we then introduced the plasmid expressing RepR (pETRepR) or the control pET22b into E. coli strains carrying either pACYC521 or pACYC525. The plasmids pACYC521 and pACYC525 carry the tcdR-gusA and tcdA-gusA fusions, respectively, along with the tcdR structural gene under its own promoter. Since the repR gene is under the control of IPTG-inducible T7 promoter, we measured β-glucuronidase activity with respect to growth with and without IPTG RepR induction. Expression of tcdA-gusA and tcdR-gusA was recorded in E. coli strains carrying pACYC521 or pACYC525 along with control pET22b. Production of RepR reduced the level of the gusA product when it was under the control of either the tcdA or tcdR promoter, and the reduction was observed throughout the growth cycle (Fig. 4a to d). The effect of RepR on the gdh promoter was measured in cells carrying the pETRepR plasmid along with pACYC528, and it was found that RepR has no effect on the gdh promoter (Fig. 4e and f). These results suggest that RepR specifically represses the tcdA and tcdR promoters when TcdR is coexpressed. This might be due to either the direct interaction of RepR with these promoters or the regulation of tcdR expression. To examine these possibilities, we purified RepR and conducted DNA binding studies.

FIG. 4.

β-Glucuronidase activity of tcdA promoter-gusA and tcdR promoter-gusA fusions (ptcdA-gusA and ptcdR-gusA, respectively). E. coli strains carrying promoter fusion plasmids along with a RepR-expressing plasmid (pETRepR) or vector (pET22-b) were grown and assayed for β-glucuronidase activity. The values represent the means of three independent experiments (plus standard error). The graphs are as follows: growth curve (b) and β-glucuronidase activity (a) of E. coli strains carrying reporter plasmid pACYC521 with tcdA-gusA; growth curve (d) and β-glucuronidase activity (c) of E. coli strains carrying reporter plasmid pACYC525 with tcdR-gusA; growth curve (f) and β-glucuronidase activity (e) of E. coli strains carrying reporter plasmid pACYC528 with gdh-gusA. Strains were grown with (+) or without (−) IPTG.

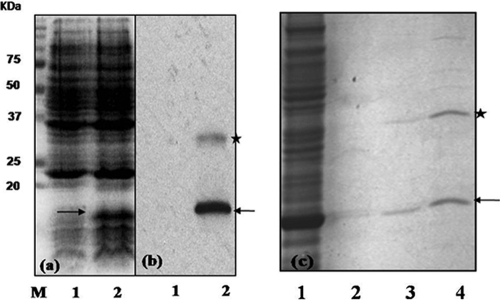

Expression and purification of ΦCD119 RepR.

To purify RepR, we transformed the pETRepR plasmid into the BL21-CodonPlus(DE3) strain, and the expression of the RepR protein was followed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses employing His6 antibodies (Invitrogen). The immunoblot of protein extracts of E. coli strain carrying the pETRepR (Fig. 5a) showed a band around 16 kDa, corresponding to the predicted size of the recombinant RepR-His6 protein. No such protein was detected in the absence of the RepR-encoding plasmid. Western blotting using anti-histidine antibodies also confirmed the expression of RepR protein. A band around 32 kDa was also detected in the Western blot, suggesting that RepR may form a dimer, like many other DNA binding proteins (19) (Fig. 5a). The expressed protein was purified (Fig. 5b) using Ni++ affinity columns and used in gel mobility shift and DNA footprinting experiments.

FIG. 5.

Expression and purification of RepR-His6 in E. coli. SDS-PAGE analysis of protein extracts from E. coli BL21(DE3) carrying either the pET22b vector or pET22b expressing RepR-His6. The OD for cultures of both E. coli strains was adjusted to 0.1 at 550 nm, and these cultures were then sonicated and boiled with SDS-PAGE sample buffer before being loaded on the gel. Lane 1, crude cell extract from E. coli carrying the vector pET22b; lane 2, crude cell extract from E. coli carrying vector expressing RepR-His6. (a) Proteins were stained by Coomassie brilliant blue. M, Precision plus protein marker (Bio-Rad). (b) Immunoblot using anti-His6 antibody. (c) Purification of RepR. Lane 1, crude cell extract of E. coli expressing RepR-His6; lanes 2, 3, and 4, RepR containing fractions collected from Ni++ affinity column for purification. Samples in lanes 3 and 4 represent the purified and partially purified RepR, respectively. The arrow indicates the monomer, and the star indicates dimeric forms of RepR.

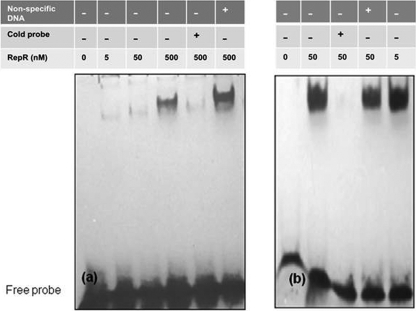

Gel shift experiments.

Initially, partially purified RepR protein (Fig. 5b, lane 4) was used in DNA binding experiments with tcdA and tcdR upstream DNAs, and it was found that RepR could bind only with tcdR and not with tcdA upstream DNA (data not shown). We then purified RepR and used different dilutions to perform DNA binding experiments with tcdR upstream DNA as well as with repR's own upstream DNA. The phage repressor proteins have been shown previously to bind to upstream operator regions to control promoters that decide lytic versus lysogenic cycles of the phage (42). Our results demonstrated that RepR can bind to its own upstream region, and competition by the addition of unlabeled excess probe abolished the binding, indicating the specificity of the interactions (Fig. 6b). Similarly, when RepR was added to a tcdR upstream DNA fragment, the mobility of the DNA was decreased, depending on the amount of RepR added, and the interaction was found to be specific through competition experiments (Fig. 6a). These results suggest that RepR modulates toxin gene expression indirectly by controlling the expression of tcdR, the toxin gene regulator.

FIG. 6.

Gel mobility shift assays with RepR protein. DNA fragments labeled with biotin were incubated with purified RepR protein. Gel mobility shift assays with tcdR upstream DNA (345 bp) (a) and with repR upstream DNA (415 bp) (b). Calf thymus DNA (100 ng) was used for the nonspecific competition, and a 50-fold excess cold probe was used for the specific competition.

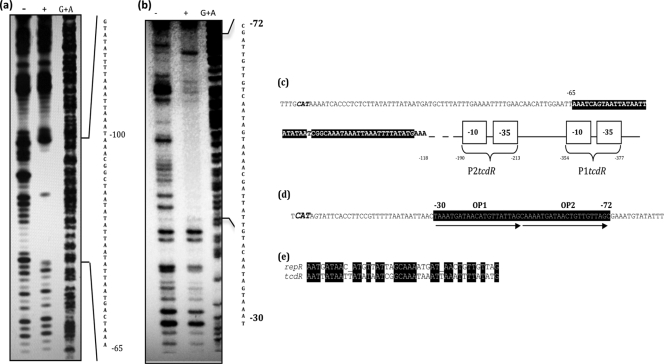

Identification of RepR binding sequences in tcdR and repR upstream regions.

To identify the specific binding sites of RepR, a DNase I footprinting assay was performed with the tcdR and repR upstream DNA regions. RepR protected a region extending from positions −68 to −118 relative to the tcdR ATG start codon (Fig. 7a), and it lies downstream of the tcdR predicted promoters (Fig. 7c) (28). RepR binds to the repeat sequences (Fig. 7b and d) upstream of the repR start codon. These repeat sequences may represent the repR operators. However, the implication of RepR's binding to these sequences in controlling the lytic versus lysogenic cycles of ΦCD119 is yet to be determined. When we aligned the RepR binding sequences in both repR and tcdR promoter regions with the LALIGN program (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/LALIGNform.html), we identified multiple sequence similarities between the two RepR binding regions (Fig. 7e). This could explain RepR's ability to bind to tcdR upstream, which resulted in reduced toxin gene expression. BLAST analysis against the C. difficile genome using the putative operator sequence (Fig. 7d) revealed many possible RepR binding sequences, and, interestingly, one was found within the coding region of the tcdC gene (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

DNase I footprinting of the tcdR and repR upstream regions bound by RepR. End-labeled DNA was incubated with RepR-His6. Following DNase I treatment, samples were run on a 9% acrylamide sequencing gel and visualized on a phosphorimager. (a) tcdR upstream DNA footprinted with RepR protein. (b) repR upstream DNA footprinted with RepR protein. The plus sign indicates lanes in which protein samples were incubated with the DNA, whereas the minus sign indicates lanes with naked DNA alone. The lanes in which the DNA has been chemically cleaved by Maxam-Gilbert G+A reactions are included in each panel as a reference. (c) Sequence analysis of tcdR upstream region. RepR binding sites in tcdR upstream regions are highlighted in black, and the relative positions of the predicted tcdR promoters P1tcdR and P2tcdR are marked. The TcdR start codon is italicized. (d) Sequence analysis of repR upstream region. The repR start codon is italicized, RepR binding sites are highlighted in black, and the direct repeats of the probable operator sequences (OP) are indicated by arrows. (e) The consensus RepR binding sequences in tcdR and repR upstream regions.

DISCUSSION

In the genus Clostridium, several toxin-encoding genes are located on mobile genetic elements such as nonintegrative lysogenic phages, lysogenic phages, and plasmids (6, 9, 17, 31). In C. difficile, it has been shown that PaLoc genes share homology with phage genes, tcdE with phage holins (41), tcdA with a Clostridium tetani phage CT2 gene (4), and tcdC with ORF22 of Lactobacillus casei phage A2 (14). In this study, by demonstrating the interaction of a phage regulator with that of a PaLoc gene, we are presenting another piece of evidence for the possible relationship of the PaLoc with a temperate bacteriophage. We examined the effect of a phage repressor, RepR, on the expression of PaLoc genes of C. difficile. We found that the expression of the ΦCD119 RepR protein in C. difficile ΦCD119 lysogens decreased toxin production. Transcriptional analysis revealed a decreased level of RNA from all five PaLoc genes (tcdR, tcdB, tcdE, tcdA, and tcdC) (Fig. 3a), and reporter gene fusion experiments in E. coli carrying tcdR indicated that the presence of RepR causes the downregulation of tcdA and tcdR promoters (Fig. 4). Furthermore, DNA binding studies indicated that RepR binds specifically to DNA sequences upstream of tcdR as well as to its own gene (Fig. 6). TcdR is an autoregulator that acts as an activator for tcdB and tcdA (8, 27, 28). Hence, our results suggest that RepR is acting through tcdR to downregulate tcdB and tcdA. RepR also downregulates tcdE, a phage holin-like gene, whose product has been speculated to play a role in toxin release through the formation of membrane lesions and eventual lysis (41). This gene lies between tcdB and tcdA, and although tcdE does not appear to have a TcdR-dependent promoter, it has been suggested that a significant amount of transcriptional read-through occurs, resulting in bicistronic transcripts, including tcdB-E (18). RepR may be regulating tcdE through TcdR regulation of tcdB. Thus, reduced TcdE-mediated host cell lysis would help the prophage to successfully maintain its lysogeny. How RepR downregulates tcdC, a negative regulator of tcdA and tcdB, is unknown and is currently under investigation. The presence of a putative RepR binding sequence within the tcdC coding region could partly explain the reduced tcdC transcription observed in ΦCD119 lysogens. If PaLoc was once part of a prophage whose gene expression was regulated by RepR, or a RepR-like repressor, then the silencing of all five PaLoc genes might be expected. Interestingly, CodY, a global regulator in C. difficile, was also found to downregulate both tcdR and tcdC (7). Similar to the function of ΦCD119 RepR, a prophage-encoded repressor regulating a host bacterial gene was reported in λ phage in an earlier study (5). In E. coli, λ infection resulted in the complete suppression of the host pckA gene, which encodes phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, a gene critical for gluconeogenesis (5). It was found that the lambda phage repressor cI, which shuts down lytic phage gene expression, also bound to the operator of the pckA gene and resulted in its downregulation.

Lysogens gain specific advantages from their relationship with phage that improve their overall fitness. In certain bacteria, infection by phage and subsequent conversion result in altered metabolic capabilities (24). In a recent review on marine prophage, the possible role of prophage-encoded repressors in shutting down unwanted metabolic pathways for the survival of the host bacteria under an unfavorable environment has been discussed (36). In C. difficile, toxin gene expression is clearly sensitive to several environmental factors such as the presence of carbon sources, temperature, biotin, and various amino acids (20-22). Certain unfavorable conditions such as the absence of glucose and high temperature are known to induce toxin gene transcription through tcdR (8, 28). Recently, Dineen et al. have demonstrated the role of codY and the level of intracellular GTP in toxin gene regulation in C. difficile (7). The effect of some of these environmental factors on repR and subsequent changes in the toxin gene expression in ΦCD119 lysogens is currently under investigation. A recent study has identified the presence of a cyclic di-GMP riboswitch within the lysis module of the ΦCD119 genome (40). Riboswitches are mRNA domains that control gene expression in response to changing concentrations of their target ligands (34). The presence of such a system in ΦCD119 clearly indicates that it has evolved to monitor the physiological changes in its host through regulatory networks, and, hence, it is reasonable to assume that their effect on PaLoc genes may be part of such a network. Hence, from our study, it appears that a phage regulator(s) is another member of the complex regulatory pathways involved in C. difficile toxin regulation.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible through the support of NIH grant 5R03DK054816-01 and by A. R. P. Norman Hackerman Advanced Research Program grant 010674-0021-2007.

We thank A. L. Sonenshein of Tufts University for the kind gift of pTUM plasmids and for his helpful suggestions throughout the study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 September 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borriello, S. P. 1990. 12th C. L. Oakley lecture. Pathogenesis of Clostridium difficile infection of the gut. J. Med. Microbiol. 33:207-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun, V., T. Hundsberger, P. Leukel, M. Sauerborn, and C. Von Eichel-Streiber. 1996. Definition of the single integration site of the pathogenicity locus in Clostridium difficile. Gene 27:29-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canchaya, C., F. Desiere, W. M. McShan, J. J. Ferretti, J. Parkhill, and H. Brussow. 2002. Genome analysis of an inducible prophage and prophage remnants integrated in the Streptococcus pyogenes strain SF370. Virology 302:245-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, Y., I. Golding, S. Sawai, L. Guo, and E. C. Cox. 2005. Population fitness and the regulation of Escherichia coli genes by bacterial viruses. PLoS Biol. 3:e229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornillot, E., B. Saint-Joanis, G. Daube, S. Katayama, P. E. Granum, B. Canard, and S. T. Cole. 1995. The enterotoxin gene (cpe) of Clostridium perfringens can be chromosomal or plasmid-borne. Mol. Microbiol. 15:639-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dineen, S. S., A. C. Villapakkam, J. T. Nordman, and A. L. Sonenshein. 2007. Repression of Clostridium difficile toxin gene expression by CodY. Mol. Microbiol. 66:206-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupuy, B., and A. L. Sonenshein. 1998. Regulated transcription of Clostridium difficile toxin genes. Mol. Microbiol. 27:107-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eklund, M. W., F. T. Poysky, S. M. Reed, and C. A. Smith. 1971. Bacteriophage and the toxicity of Clostridium botulinum type C. Science 172:480-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn, C. W., Jr., R. P. Silver, W. H. Habig, M. C. Hardegree, G. Zon, and C. F. Garon. 1984. The structural gene for tetanus neurotoxin is on a plasmid. Science 224:881-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortier, L. C., and S. Moineau. 2007. Morphological and genetic diversity of temperate phages in Clostridium difficile. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7358-7366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goh, S., B. J. Chang, and T. V. Riley. 2005. Effect of phage infection on toxin production by Clostridium difficile. J. Med. Microbiol. 54:129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goh, S., P. F. Ong, K. P. Song, T. V. Riley, and B. J. Chang. 2007. The complete genome sequence of Clostridium difficile phage phiC2 and comparisons to phiCD119 and inducible prophages of CD630. Microbiology 153:676-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goh, S., T. V. Riley, and B. J. Chang. 2005. Isolation and characterization of temperate bacteriophages of Clostridium difficile. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1079-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Govind, R., J. A. Fralick, and R. D. Rolfe. 2006. Genomic organization and molecular characterization of Clostridium difficile bacteriophage ΦCD119. J. Bacteriol. 188:2568-2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammond, G. A., and J. L. Johnson. 1995. The toxigenic element of Clostridium difficile strain VPI 10463. Microb. Pathog. 19:203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauser, D., M. Gibert, P. Boquet, and M. R. Popoff. 1992. Plasmid localization of a type E botulinal neurotoxin gene homologue in toxigenic Clostridium butyricum strains, and absence of this gene in non-toxigenic C. butyricum strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 78:251-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hundsberger, T., V. Braun, M. Weidmann, P. Leukel, M. Sauerborn, and C. von Eichel-Streiber. 1997. Transcription analysis of the genes tcdA-E of the pathogenicity locus of Clostridium difficile. Eur. J. Biochem. 244:735-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia, H., W. J. Satumba, G. L. Bidwell, 3rd, and M. C. Mossing. 2005. Slow assembly and disassembly of lambda Cro repressor dimers. J. Mol. Biol. 350:919-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karlsson, S., L. G. Burman, and T. Akerlund. 2008. Induction of toxins in Clostridium difficile is associated with dramatic changes of its metabolism. Microbiology 154:3430-3436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karlsson, S., L. G. Burman, and T. Akerlund. 1999. Suppression of toxin production in Clostridium difficile VPI 10463 by amino acids. Microbiology 145:1683-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karlsson, S., B. Dupuy, K. Mukherjee, E. Norin, L. G. Burman, and T. Akerlund. 2003. Expression of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B and their sigma factor TcdD is controlled by temperature. Infect. Immun. 71:1784-1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ketley, J. M., S. C. Haslam, T. J. Mitchell, J. Stephen, D. C. Candy, and D. W. Burdon. 1984. Production and release of toxins A and B by Clostridium difficile. J. Med. Microbiol. 18:385-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin, B. R., and R. E. Lenski. 1983. Coevolution in bacteria and their viruses and plasmids. Sinauer, Sunderland, MA.

- 25.Li, N., Y. Chen, and J. Feng. 1995. Cloning and analysis of prophage PBSX repressor gene from Bacillus subtilis. Yi Chuan Xue Bao 22:478-486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahony, D. E., P. D. Bell, and K. B. Easterbrook. 1985. Two bacteriophages of Clostridium difficile. J. Clin. Microbiol. 21:251-254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mani, N., and B. Dupuy. 2001. Regulation of toxin synthesis in Clostridium difficile by an alternative RNA polymerase sigma factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5844-5849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mani, N., D. Lyras, L. Barroso, P. Howarth, T. Wilkins, J. I. Rood, A. L. Sonenshein, and B. Dupuy. 2002. Environmental response and autoregulation of Clostridium difficile TxeR, a sigma factor for toxin gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 184:5971-5978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matamouros, S., P. England, and B. Dupuy. 2007. Clostridium difficile toxin expression is inhibited by the novel regulator TcdC. Mol. Microbiol. 64:1274-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maxam, A. M., and W. Gilbert. 1977. A new method for sequencing DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:560-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyamoto, K., J. Li, S. Sayeed, S. Akimoto, and B. A. McClane. 2008. Sequencing and diversity analyses reveal extensive similarities between some epsilon-toxin-encoding plasmids and the pCPF5603 Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 190:7178-7188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moncrief, J. S., L. A. Barroso, and T. D. Wilkins. 1997. Positive regulation of Clostridium difficile toxins. Infect. Immun. 65:1105-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Novel, M., and G. Novel. 1976. Regulation of beta-glucuronidase synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12: pleiotropic constitutive mutations affecting uxu and uidA expression. J. Bacteriol. 127:418-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nudler, E., and A. S. Mironov. 2004. The riboswitch control of bacterial metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29:11-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osgood, D. P., N. P. Wood, and J. F. Sperry. 1993. Nutritional aspects of cytotoxin production by Clostridium difficile. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3985-3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paul, J. H. 2008. Prophages in marine bacteria: dangerous molecular time bombs or the key to survival in the seas? ISME J. 2:579-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramesh, V., J. A. Fralick, and R. D. Rolfe. 1999. Prevention of Clostridium difficile-induced ileocecitis with bacteriophage. Anaerobe 5:69-78. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 39.Sebaihia, M., B. W. Wren, P. Mullany, N. F. Fairweather, N. Minton, R. Stabler, N. R. Thomson, A. P. Roberts, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, H. Wang, M. T. Holden, A. Wright, C. Churcher, M. A. Quail, S. Baker, N. Bason, K. Brooks, T. Chillingworth, A. Cronin, P. Davis, L. Dowd, A. Fraser, T. Feltwell, Z. Hance, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, S. Moule, K. Mungall, C. Price, E. Rabbinowitsch, S. Sharp, M. Simmonds, K. Stevens, L. Unwin, S. Whithead, B. Dupuy, G. Dougan, B. Barrell, and J. Parkhill. 2006. The multidrug-resistant human pathogen Clostridium difficile has a highly mobile, mosaic genome. Nat. Genet. 38:779-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sudarsan, N., E. R. Lee, Z. Weinberg, R. H. Moy, J. N. Kim, K. H. Link, and R. R. Breaker. 2008. Riboswitches in eubacteria sense the second messenger cyclic di-GMP. Science 321:411-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan, K. S., B. Y. Wee, and K. P. Song. 2001. Evidence for holin function of tcdE gene in the pathogenicity of Clostridium difficile. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:613-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waldor, M. K., and D. I. Friedman. 2005. Phage regulatory circuits and virulence gene expression. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8:459-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]