Abstract

Previous studies determined that the CD8+ T-cell response elicited by recombinant adenovirus exhibited a protracted contraction phase that was associated with long-term presentation of antigen. To gain further insight into this process, a doxycycline-regulated adenovirus was constructed to enable controlled extinction of transgene expression in vivo. We investigated the impact of premature termination of transgene expression at various time points (day 3 to day 60) following immunization. When transgene expression was terminated before the maximum response had been attained, overall expansion was attenuated, yielding a small memory population. When transgene expression was terminated between day 13 and day 30, the memory population was not sustained, demonstrating that the early memory population was antigen dependent. Extinction of transgene expression at day 60 had no obvious impact on memory maintenance, indicating that maintenance of the memory population may ultimately become independent of transgene expression. Premature termination of antigen expression had significant but modest effects on the phenotype and cytokine profile of the memory population. These results offer new insights into the mechanisms of memory CD8+ T-cell maintenance following immunization with a recombinant adenovirus.

Recombinant human adenovirus 5 (rHuAd5) vector vaccines have garnered considerable attention as platforms for eliciting CD8+ T-cell immunity due to their strong immunogenicity in numerous studies, including primate studies and preliminary human trials (30, 32, 53). While these vectors may not represent the optimal serotype for use in humans, due to the high prevalence of preexisting immunity, the robust immunogenicity of rHuAd5 in preclinical models merits further investigation, since the biological information derived from these studies will offer important insights that can be extended to other vaccine platforms.

CD8+ T cells play an important role in host defense against tumors and viral infections. During the primary phase of the CD8+ T-cell response, the activated precursors undergo a rapid and dramatic expansion in cell number, followed by a period of contraction where 80 to 90% of the antigen-specific population dies off, leaving the remaining cells to constitute the memory population (44). CD8+ T cells mature over the course of the primary response and acquire the ability to produce gamma interferon (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and, to a lesser degree, interleukin 2 (IL-2). Memory T cells can be divided into central memory and effector memory T cells based on phenotype and anatomical location (44). These phenotypic differences have also been linked to functional differences; however, these relationships remain controversial (2, 16, 20, 46, 55).

Various reports have revealed some unexpected qualities of the CD8+ T-cell response generated by intramuscular immunization with rHuAd5. The rHuAd5-induced CD8+ T-cell response exhibited a protracted contraction phase, and the memory population was composed primarily of effector and effector-memory cells (23, 38, 39, 41, 51). The phenotype of the rHuAd5-elicited CD8+ T-cell population was more consistent with the CD8+ T-cell population observed in persistent infections, such as polyomavirus (25), murine herpesvirus-68 (35), and murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) (1) infections, than with that observed in acute infections, such as lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) (44), vaccinia virus (15), and influenza virus (24) infections. Further investigation demonstrated that, as in a persistent infection, antigen presentation persisted for a prolonged period following intramuscular immunization with rHuAd5, and transgene expression could persist at low levels for more than 1 year following infection (41, 51). These data suggest that the sustained effector phenotype may arise from prolonged, low-level transgene expression from the rHuAd5 vector, although this connection was not formally proven. It is difficult to fully appreciate the implications of these observations at this time, since chronic exposure to antigen is often associated with CD8+ T-cell dysfunction, yet rHuAd5 vectors have been used successfully to elicit protective immunity in many models of pathogen infection and tumor challenge (5, 54). Nevertheless, other reports have provided evidence that rHuAd5 vectors can, indeed, lead to dysfunctional CD8+ T-cell immunity (27, 36). Therefore, further investigation is necessary in order to properly assess the implications of the prolonged antigen expression following rHuAd5 immunization in terms of sustaining a functional memory CD8+ T-cell response.

In the current report, we sought to determine the relationship between transgene expression and CD8+ T-cell maintenance and memory. To this end, we constructed an Ad vector with a doxycycline (DOX)-regulated expression cassette that would permit attenuation of gene expression at various times postinfection. Using this reagent, we addressed two key questions. (i) How does the duration of antigen expression affect the magnitude of primary CD8+ T-cell expansion? (ii) Is antigen expression required beyond the peak expansion to maintain the memory CD8+ T-cell population?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of plasmids and replication-deficient adenovirus (rHuAd5).

The pTet-OFF plasmid was the source of the tetracycline transactivator (tTA) gene (Clontech). pTREminCMV-Luc contains a modified version of luciferase bearing the immunodominant class I epitope from chicken egg ovalbumin (SIINFEKL) tagged to the N terminus under the control of the Tet response element (TRE) fused with the minimal CMV promoter (from pUHD 10-3, a gift from H. Bujard) and terminated by the bovine growth hormone polyadenylation sequence. pTREminIL2-Luc contains the SIINFEKL-luciferase transgene under the control of the TRE fused with the minimal IL-2 promoter (obtained from pZ12I-PL-2, graciously provided by Ariad Pharmaceuticals) and terminated by the simian virus 40 polyadenylation sequence. pGL3-Basic (Promega) consists of the luciferase transgene lacking any eukaryotic promoter. Plasmid ptTA-TRE-SIINFEKL-Luc consists of an expression cassette where tTA is transcribed under the control of the MCMV immediate-early promoter and the reporter cassette from pTREminIL2-Luc on a single plasmid in a tail-to-tail configuration. Plasmid ptTA-HS4-TRE-SIINFEKL-Luc is a variant of ptTA-TRE-SIINFEKL-Luc where the two cassettes are separated by an HS4 chicken β-globin locus core insulator fragment (from pNI-CD, a gift of Adam West).

A recombinant adenovirus (rHuAd5) vector carrying the expression cassette from ptTA-HS4-TRE-SIINFEKL-Luc was rescued using the E1- and E3-deleted backbone described by Ng et al. (34) and named Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc. A control virus, AdSIINFEKL-Luc, expressing the SIINFEKL-Luc transgene under the control of the constitutive MCMV promoter, has been described previously (50). All rHuAd5 vectors were propagated using 293 cells and were purified using CsCl gradient centrifugation as previously described (7). Two preparations of Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc, with particle/PFU ratios of 25 and 34, were used for these experiments.

Immunizations and DOX treatment.

Female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Breeding Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). For immunizations, 107 to 109 PFU rHuAd5 was diluted to 100 μl in sterile phosphate-buffered saline and was subsequently injected intramuscularly into both rear thighs. A rHuAd5 expressing the SIINFEKL-Luc antigen under the control of the constitutive MCMV promoter (AdSIINFEKL-Luc-004) has been described by our group previously (50). To measure secondary responses, mice were challenged with 5 × 106 PFU of a recombinant vaccinia virus (rVV) expressing the SIINFEKL epitope linked to an endoplasmic reticulum-targeting signal (rVV-ESOVA) (graciously provided by Jonathan Yewdell, NIAID, Bethesda, MD). DOX was administered initially as an intraperitoneal injection of 500 μg DOX and was maintained by the addition of DOX to the drinking water. Mice were initially given a high dose of DOX in their drinking water (2 mg/ml) for 48 h and were subsequently maintained on 200 μg/ml DOX. The drinking water was also supplemented with 5% sucrose. This dosing of DOX was found to completely ablate the CD8+ T-cell response to Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc but to have no effect on the CD8+ T-cell response produced by Ad-SIINFEKL-Luc-004. The animal studies described in this report have been approved by the Animal Research Ethics Board of McMaster University.

Flow cytometry reagents.

All flow cytometry antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen except for anti-CD127 (clone A7R34) and anti-KLRG1 (clone MAFA), which were purchased from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA). The following antibodies and fluorescent reagents were purchased from BD Pharmingen: anti-CD8α (clone 53-6.7), anti-CD62L (clone MEL-14), anti-IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2), anti-TNF-α (clone 53-2.1), anti-IL-2 (clone JES6-5H4), and anti-Thy1.2 (clone 30H12). Allophycocyanin (APC)-labeled Kb/SIINFEKL tetramers were prepared at McMaster University or Baylor College of Medicine. Most staining conditions involved five to six fluorochromes (fluorescein isothiocyanate, phycoerythrin [PE], PE-Cy5, PE-Cy7, APC, APC-Alexa Fluor 750), and data were acquired using either an LSRII or a FACSCanto system equipped with a 488-nm and 633-nm laser.

Analysis of T-cell responses.

Sample preparation and staining methodologies have been described in our previous publications (51, 52). Briefly, splenic cell suspensions were prepared by disrupting the spleen between the frosted tips of two glass slides. Lung cell suspensions were generated by dicing whole lungs, incubating them in Hanks balanced salt solution containing 150 U/ml collagenase type 1 from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) for 1 h at 37°C, and passing the slurry through a 70-μm-pore-size cell strainer (BD) to obtain single-cell suspensions. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were prepared by treating whole blood with two rounds of 0.15 M NH4Cl lysis buffer for 5 min (peripheral blood samples were treated twice with lysis buffer). All cell suspensions were aliquoted into 96-well round-bottom plates at 2 × 106 cells/well (BD Pharmingen). Prior to all antibody and tetramer staining, samples were incubated at 4°C for 15 min with Fc block (clone 2.4G2; BD Pharmingen) diluted in fluorescence-activated cell sorter buffer (0.5% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline). For intracellular cytokine staining, the cells were seeded in cell culture medium and stimulated with 1 μM SIINFEKL in the presence of 5 μM brefeldin A for 5 h. Cells were subsequently stained for surface markers, permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences), and stained for intracellular cytokines.

Measurement of vaccinia virus in mouse ovaries.

Ovaries were homogenized in 2 ml of 1 mM Tris, pH 9.0. The homogenates were further disrupted by three consecutive “freeze-thaw” cycles. To determine virus titers in the homogenates, confluent CV-1 cells in 12-well plates were infected with serial dilutions of the homogenate, and 2 days later, plaques were visualized by staining with 0.1% crystal violet in 20% ethanol.

Statistical analysis.

Student t tests were conducted using Microsoft Excel, and differences were considered significant at a P value of <0.05. Data are presented as means ± standard errors.

RESULTS

Development and characterization of a repressible rHuAd5 expression system.

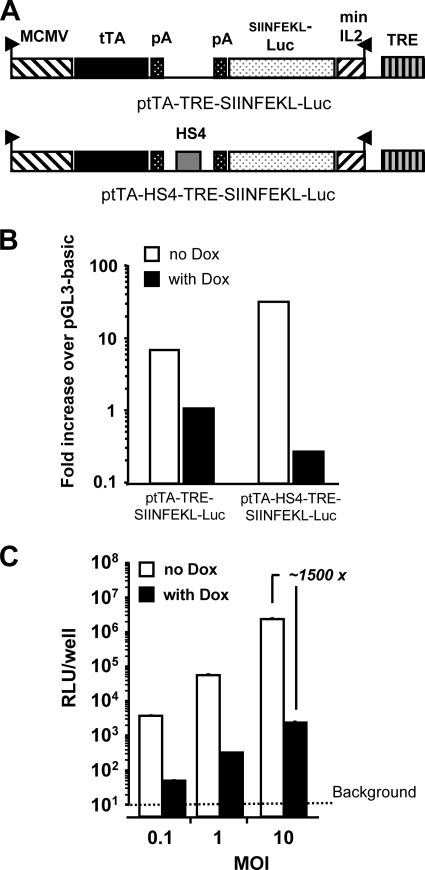

For these investigations, we have employed a model antigen, SIINFEKL-Luc, where the dominant CD8+ T-cell epitope of chicken egg ovalbumin was fused to the N terminus of the firefly luciferase gene (51). To determine the importance of the duration of antigen expression to the CD8+ T-cell response following rHuAd5 immunization, we employed the “Tet-OFF” expression system, where the presence of DOX will terminate gene expression (10). We initially tested the minimal CMV promoter fused to the TRE as an inducible promoter to regulate SIINFEKL-Luc expression; however, we found that this configuration resulted in poor repression of gene expression (data not shown). The minimal CMV promoter was replaced with the minimal IL-2 promoter, and repression was significantly enhanced (data not shown). To produce a single vector that expressed both the tTA and the inducible transgene, we inserted the TRE-minIL2-SIINFEKL-Luc cassette into a plasmid that contained a cassette where tTA was expressed under the control of the MCMV immediate-early promoter. The two cassettes were oriented in a tail-to-tail fashion (Fig. 1A). This configuration provided only modest suppression of transgene expression in the presence of DOX (Fig. 1B). We found that suppression could be greatly increased by the inclusion of an HS4 insulator between the two cassettes (Fig. 1A and B). We therefore rescued the HS4-containing expression system into a rHuAd5 vector (named Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc) that was used subsequently for all in vivo studies. We observed high repression levels (∼1,500-fold) in the presence of DOX across a range of multiplicities of infection in vitro (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Modified DOX-regulated expression cassettes provides robust control of gene expression. (A) Schematic representations of the expression elements in ptTA-TRE-SIINFEKL-Luc, where a cassette expressing tTA under the control of the constitutive MCMV promoter was fused tail-to-tail with the TREminIL2-SIINFEKL-Luc expression cassette, and in ptTA-HS4-TRE-SIINFEKL-Luc, a derivative of ptTA-TRE-SIINFEKL-Luc in which an HS4 core insulator fragment was inserted between the two cassettes. (B) Plasmids containing the expression elements diagramed in panel A were individually transfected into BHK cells and cultured in the presence or absence of DOX (10 μg/ml), and luciferase activity was assayed. (C) An rHuAd5 vector (Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc) encoding the bifunctional, HS4-separated expression system diagramed in panel A was purified and tested at a range of multiplicities of infection on BHK cells in the presence or absence of DOX (10 μg/ml).

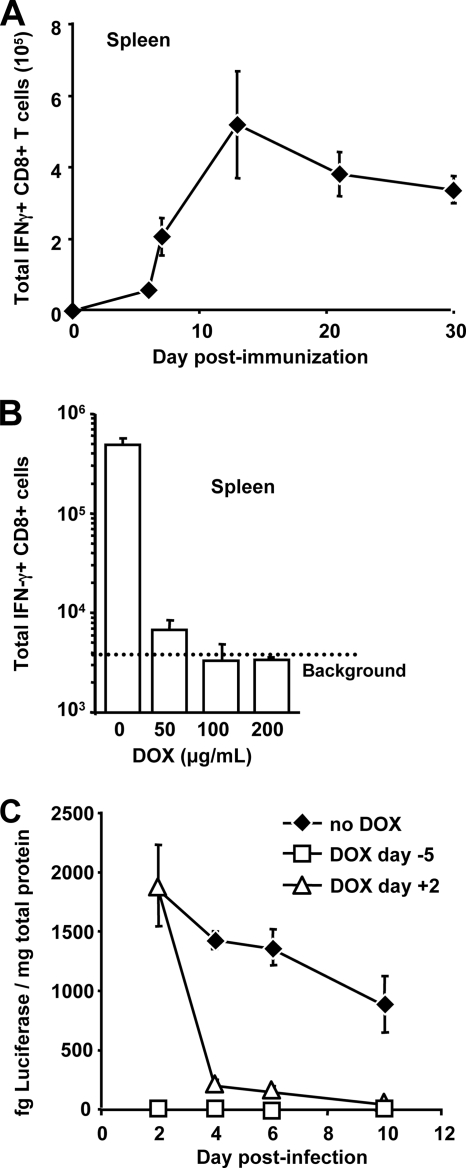

To make the best use of this model, it was necessary to identify a dose of Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc that produced sufficiently high levels of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells for accurate assessment by flow cytometry. Mice were immunized with 108, 3 × 108, or 109 PFU of Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc, and SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells were measured in the blood 14 days later. It was found that 109 PFU of Ad-tTA- SIINFEKL-Luc gave rise to a consistent and measurable response (data not shown), so this dose was used for all further studies. To verify that the kinetics of CD8+ T-cell expansion and contraction following immunization with 109 PFU Ad-tTA-SINFEKL-Luc were consistent with our previously observed data, we examined the numbers of CD8+ T cells present in the spleen at various time points following immunization with Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc (Fig. 2A). In agreement with our previous results, we observed that the SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T-cell population expands dramatically between day 6 and day 12 following immunization and that it subsequently exhibits a slow decline in numbers (50, 51) (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc elicits an immune response comparable to those of other rHuAd5 vectors that can be fully attenuated by treatment with DOX. (A) C57BL/6 mice (three per group) were immunized with 109 PFU of Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc, and the numbers of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleens of mice sacrificed at various times postimmunization were assessed. Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean. (B) C57BL/6 mice (three per group) received a single bolus intraperitoneal injection of DOX 5 days prior to immunization and were subsequently given water containing either 50, 100, or 200 μg/ml DOX. Five days following the initiation of DOX treatment, mice were immunized with 109 PFU of Ad-tTa-SIINFEKLuc. Mice were sacrificed 22 days postimmunization, and the total number of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells in each spleen was assessed. Each data point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean. (C) C57BL/6 mice received 109 PFU Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc intramuscularly in the presence or absence of DOX. One group of mice (DOX day −5) started DOX treatment 5 days prior to immunization. The second group (DOX day +2) started DOX treatment 2 days after immunization. The third group of mice (no DOX) did not receive any DOX during the period of the experiment. Thigh muscles were harvested at the time points indicated and assayed for luciferase activity. The results are means ± standard errors of the means for six muscle samples per group.

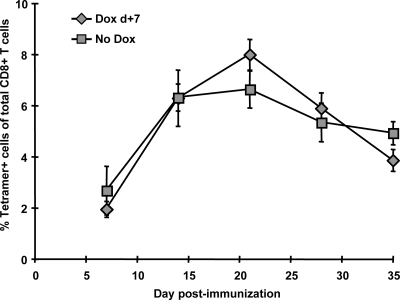

To confirm that DOX treatment would result in sufficient attenuation of gene expression to suppress the induction of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells, mice were administered various doses of DOX in their drinking water 5 days before immunization with Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc, and SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T-cell responses were measured in the spleen 3 weeks after immunization. While DOX concentrations as low as 50 μg/ml and 100 μg/ml resulted in substantial attenuation of the SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T-cell response, a dose of 200 μg/ml was necessary to completely abrogate the SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ response in all mice (Fig. 2B). Similar results were observed in the peripheral blood (data not shown). To test suppression of gene expression following immunization, DOX treatment was initiated 2 days following immunization with Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc and resulted in rapid repression of gene expression (Fig. 2C). To confirm that DOX treatment was not having a nonspecific effect on the CD8+ T-cell response, mice were treated with DOX before and after immunization with AdSIINFEKL-Luc-004 (51). The frequencies of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells in mice treated with DOX were equivalent to those in mice immunized in the absence of DOX around the peak of the response (day 12 to 14) and later in the response (day 21 to 28) (Fig. 3 and data not shown).

FIG. 3.

DOX treatment does not affect the magnitude of the CD8+ T-cell population produced by rHuAd5 vectors that employ constitutive promoters. C57BL/6 mice (n = 10) were immunized with 107 PFU of Ad-SIINFEKL-Luc, and half of the mice were treated with DOX beginning at 7 days postimmunization (Dox d+7). The number of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells was assessed by tetramer staining of peripheral blood mononuclear cells at various times postimmunization. Each point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean for five mice.

Early termination of antigen expression affects the magnitude and kinetics of the antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell response.

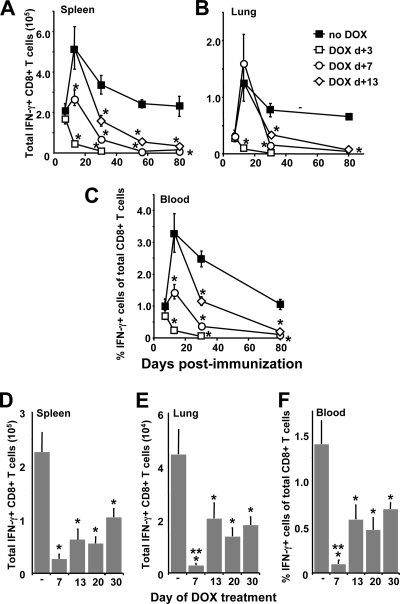

To establish a causal link between antigen expression and CD8+ T-cell expansion/contraction, we employed the DOX-regulated vector to investigate the impact of premature termination of antigen expression on the CD8+ T-cell response. Mice were immunized with 109 PFU of Ad-tTa-SIINFEKL-Luc, and transgene expression was extinguished by initiating DOX treatment at 3 days (prior to the appearance of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells), 7 days (during the expansion phase), or 13 days (around the peak of the response) postimmunization. Mice were sacrificed at various time points, and the presence of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen, lung, and blood was surveyed (Fig. 4A to C). When DOX was administered on day 3, SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells could be measured in all tissues at day 7 (Fig. 4) with frequencies similar to those for mice that did not receive DOX. This likely reflects the fact that several days were required to fully repress transgene expression (Fig. 2C). What is most notable about the mice treated with DOX on day 3 (Fig. 4A to C) is the dramatic and rapid loss of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells, such that we could barely detect any antigen-specific cells 30 days after immunization in this group. Similarly, the frequencies of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells in mice treated with DOX on day 7 continued to rise after DOX treatment was initiated, but, again, the population exhibited a dramatic decline (Fig. 4A to C). Strikingly, when DOX treatment was initiated at day 13, a point where the CD8+ T-cell response was close to maximum (Fig. 2A), the SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T-cell population again exhibited a marked decline at later time points, demonstrating clearly that maintenance of the memory population was dependent on continued transgene expression for more than 2 weeks following immunization.

FIG. 4.

Premature suppression of transgene expression attenuates the magnitude of the primary responses and impairs memory maintenance. (A to C) Mice (eight per group) were immunized with 109 PFU of Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc on day zero and were separated into four groups. Groups 1, 2, and 3 were started on DOX 3 days (DOX d+3) (open squares), 7 days (DOX d+7) (open circles), and 13 days (DOX d+13) (open diamonds) after immunization, respectively, while group 4 received no DOX (filled squares). At the time points indicated, mice were sacrificed, and SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen (A), lung (B), and blood (C) were enumerated. Each data point represents the mean ± standard error of the mean. (D to F) Mice (five per group) were immunized with 109 PFU of Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc on day zero and were treated with DOX 7 days, 13 days, 20 days, or 30 days later. The control group received no DOX (−). Ninety days after immunization, mice were sacrificed, and SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells were enumerated in the spleen (D), lung (E), and blood (F). Each bar represents the mean ± standard error of the mean. *, significantly different from the group receiving no DOX (P < 0.05); **, significantly different from the groups receiving DOX on days 13 to 30 (P < 0.05).

Although our previous reports have demonstrated that the peak following intramuscular immunization with rHuAd5 occurs around 10 to 14 days postimmunization (50-52), it is possible that the peak response following immunization with Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc may occur at a later time point than in our previous results. Figure 2A demonstrates that the peak of the CD8+ T-cell response occurred prior to day 20 postimmunization. Therefore, to characterize the importance of transgene expression beyond the peak of the response, expression was extinguished at either day 20 or day 30 postimmunization, and antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were enumerated in the spleen, lung, and blood on day 90 after immunization. We observed a significant reduction in the numbers of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells in all tissues examined when transgene expression was extinguished as late as 30 days following immunization (Fig. 4D to F). Termination of transgene expression at day 7 had the most pronounced effect. Interestingly, the frequencies of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells were similar in the groups treated with DOX on either day 13, day 20, or day 30, suggesting a continual need for transgene expression to maintain the CD8+ T-cell memory population beyond the peak of the response.

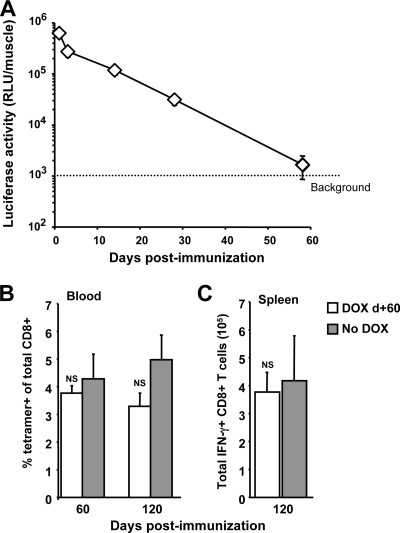

We investigated the duration of transgene expression from the Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc vector over a 2-month period and observed that while transgene expression was measurable for 30 days postimmunization, expression was reduced to background levels by day 58 (Fig. 5A). Consistent with the loss of transgene expression, we determined that treatment with DOX starting at 60 days postimmunization did not produce a significant decline in the CD8+ T-cell population measured 2 months after the onset of DOX treatment (120 days postimmunization) (Fig. 5B and C). Thus, it appears that although long-term maintenance of the transgene-specific CD8+ T-cell population produced by rHuAd5 is dependent on persistent transgene expression for at least 30 days following immunization, the population becomes independent of transgene expression around 60 days postimmunization. Whether the memory population has become independent of antigen remains to be determined.

FIG. 5.

Termination of transgene expression 60 days following immunization does not affect the maintenance of the memory response. (A) C57BL/6 mice received 109 PFU Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc intramuscularly. Thigh muscles were harvested at 1, 3, 14, 28, and 58 days and were assayed for luciferase activity. The results are means ± standard errors of the means for 10 muscle samples per time point. (B and C) Mice (five per group) were immunized with 109 PFU of Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc on day zero. On day 60, half of the mice were put on DOX. (B) The frequency of SIINFEKL-specific cells was assessed on the day DOX treatment began (day 60) and 2 months later (day 120). (C) The number of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen was assessed 2 months after the onset of DOX treatment. Open bars, results for mice that received DOX on day 60 (DOX d+60); shaded bars, results for mice that did not receive DOX. Each bar reflects the mean ± standard error of the mean. NS, not significant.

Long-term gene expression impacts protective immunity but not the magnitude of the CD8+ T-cell population following secondary challenge.

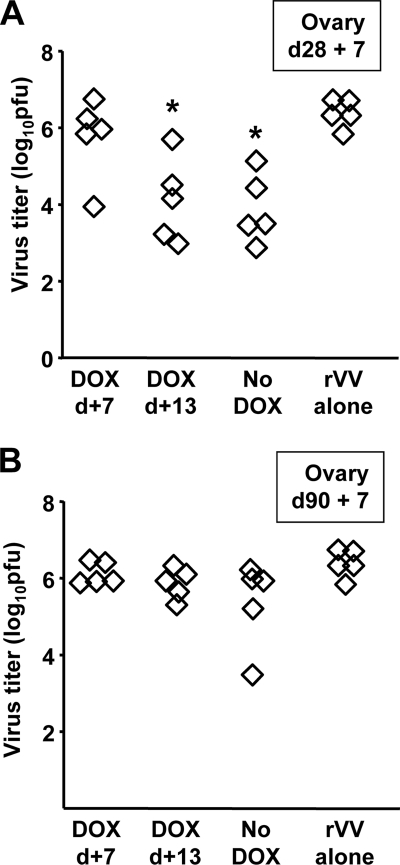

We have previously observed that the frequencies of circulating antigen-specific CD8+ T cells are associated with the magnitude of protection following virus challenge (51, 52). To determine whether the diminished levels of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells in mice treated with DOX had an impact on protection, mice were immunized with Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc and were started on DOX either 7 or 13 days after immunization. Twenty-eight and 90 days later, the mice were challenged with rVV-ESOVA, which shares only the SIINFEKL epitope with Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc; therefore, protective immunity is a direct measure of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells. Mice immunized with Ad-tTA- SIINFEKL-Luc showed lower levels of rVV-ESOVA than unimmunized mice when challenged 28 days after immunization (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, mice treated with DOX 13 days after immunization displayed levels of protection similar to those of the control mice (Fig. 6A). Mice that received DOX treatment 7 days after immunization showed no significant reduction in virus titers relative to unimmunized mice. In contrast, we did not observe any significant protection at day 90 postimmunization (Fig. 6B), indicating that the frequencies of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells in all groups had dropped below the protective level.

FIG. 6.

Premature termination of transgene expression impairs protective immunity. Mice were immunized with 109 PFU of Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc on day zero and were separated into three groups. Groups 1 and 2 were started on DOX 7 days (DOX d+7) and 13 days (DOX d+13) after immunization, respectively, while group 3 received no DOX. Five mice from each group were challenged with 107 PFU rVV-ESOVA either 28 (A) or 90 (B) days after immunization. Ovaries from the rVV-ESOVA-challenged mice were also harvested following virus challenge and were assayed for infectious vaccinia virus. Each point represents a single mouse. *, significantly different from the group receiving no DOX (P < 0.05).

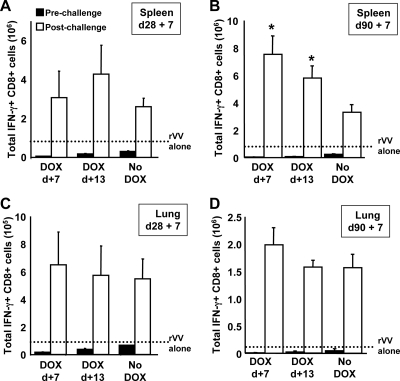

To determine whether premature termination of transgene expression impacted the secondary response following rVV-ESOVA challenge, SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells were enumerated before and after rVV-ESOVA challenge (Fig. 7). As described earlier in the text, premature termination of transgene expression had a marked impact on the frequencies of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells prior to challenge (Fig. 7). Regardless of the number of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells available prior to rVV challenge, secondary expansion in the mice receiving DOX was of equal, or greater, magnitude to the secondary expansion in control mice (Fig. 7). In fact, expansion within the spleen (Fig. 7B) and peritoneal lavage fluid (not shown) at day 90 + 7 was greatest in mice for whom transgene expression was terminated on day 7.

FIG. 7.

Premature termination of transgene expression does not impact the secondary response. Mice were immunized with 109 PFU of Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc on day zero and were separated into three groups. Groups 1 and 2 were started on DOX 7 days (DOX d+7) and 13 days (DOX d+13) after immunization, respectively, while group 3 received no DOX. Five mice from each group were challenged with 107 PFU rVV-ESOVA either 28 or 90 days after immunization. (A to D) SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells were enumerated in the spleen or lung before rVV-ESOVA challenge (filled bars) and 7 days following rVV-ESOVA challenge (open bars). The dotted lines represent the numbers of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells produced by immunization with rVV-ESOVA alone. Each bar represents the mean ± standard error of the mean for five mice. *, significantly different from the group receiving no DOX (P < 0.05).

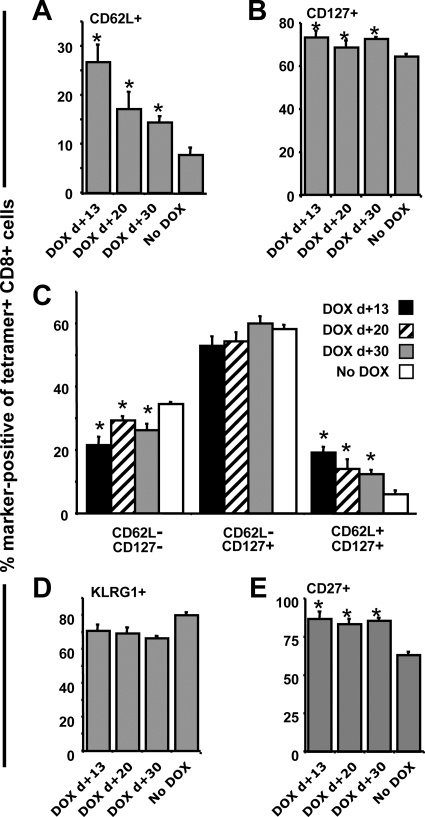

Early termination of antigen expression augments the proportion of central memory CD8+ T cells.

Since CD62L expression has been associated with CD8+ T cells that exhibit high-proliferative capacity (18), it was of interest to determine whether this marker was elevated on memory populations in the mice treated with DOX. We also examined CD127 expression, because the combination of CD127 and CD62L has been employed to separate memory cells into effector (CD62L− CD127−), effector memory (CD62L− CD127+), and central memory (CD62L+ CD127+) cells (18). Premature termination of transgene expression promoted increases in both CD62L and CD127 expression (Fig. 8A and B), which resulted in significant increases in the frequency of central memory cells and a decrease in the frequency of effector cells (Fig. 8C). These phenotypic changes are consistent with the enhanced secondary expansion observed in Fig. 7. We and others have previously reported that the CD8+ T-cell population evoked by rHuAd5 immunization exhibits a sustained effector memory phenotype (41, 51, 52), which was thought to arise from antigen persistence following infection with rHuAd5. KLRG1, a natural killer cell marker, serves as a marker for T cells that have been chronically exposed to antigen and has more recently been associated with short-lived effector CD8+ T cells (21, 42). Indeed, consistent with the requirement for sustained expression of antigen to maintain the CD8+ T-cell memory population, we observed that >80% of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells present at 90 days postimmunization were KLRG1 positive (Fig. 8D). Termination of transgene expression prior to day 30 resulted in a small decrease in KLRG1 expression (Fig. 8D). Interestingly, the KLRG1-positive SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells displayed a reciprocal decrease in the expression of CD27, a marker associated with replicative competence and T-cell fitness (data not shown). When transgene expression was terminated prior to day 30, CD27 expression was elevated in all groups equally (Fig. 8E). For the most part, however, the changes in phenotype were modest, with the exception of CD62L expression, and the majority of the cells retained an effector memory phenotype with high-level expression of KLRG1, even in the group that received DOX on day 13. We could not include data from mice that received DOX on day 7, because the frequencies of antigen-specific cells were too low to conduct multiparametric analyses.

FIG. 8.

Premature extinction of transgene expression results in increased frequencies of central memory cells. Mice were first immunized with Ad-tTA-SIINFEKL-Luc and were then put on DOX 13, 20, and 30 days later. Splenocytes were obtained 90 days after immunization and were examined for the expression of KLRG1, CD27, CD62L, and CD127. Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were identified by tetramer staining. The histograms represent SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells. (A and B) Frequencies of cells expressing CD62L and CD127, respectively. (C) Frequencies of effector (CD127− CD62L−), effector memory (CD127+ CD62L−), and central memory (CD127+ CD62L+) cells within the tetramer-positive CD8+ population. (D and E) Frequencies of cells expressing KLRG1 and CD27, respectively. Data reflect the means ± standard errors of the means for five mice. *, significantly different from the group receiving no DOX (P < 0.05).

Early termination of antigen expression augments TNF-α production by IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells.

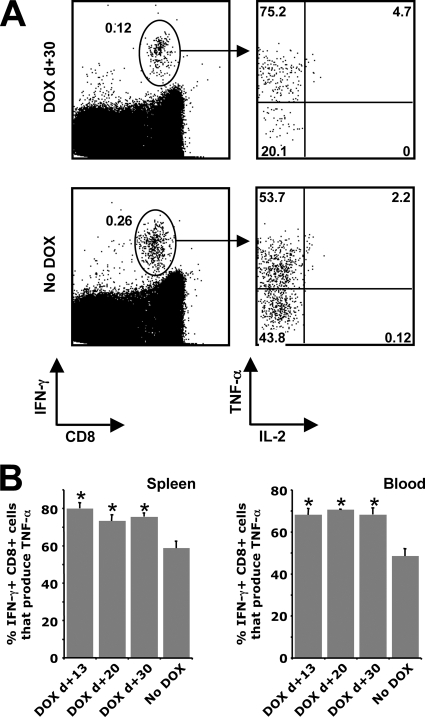

We have previously observed that only a fraction of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cells produced by our rHuAd5 vectors can express TNF-α and that very few produce IL-2 (51, 52). Since CD8+ T cells exposed to chronic antigen exhibit a hierarchical loss of the ability to produce IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ (45), we speculated that the reduced expression of TNF-α and IL-2 may be related to antigen persistence following immunization with rHuAd5. Examination of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cells present in the spleen, lungs, and blood of mice 90 days postimmunization revealed that extinction of transgene expression prior to day 30 yielded a CD8+ T-cell population with a significantly improved capacity for TNF-α production (Fig. 9). It should be noted that we did not include samples from mice that received DOX on day 7, because the frequencies of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells were too low to conduct detailed multiparametric analyses. Extinction of transgene expression between day 13 and day 30 postimmunization yielded approximately twofold greater numbers of IL-2-producing SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells; however, the frequencies of IL-2-producing cells remained less than 10% of the total antigen-specific population defined by IFN-γ production (Fig. 9A; also data not shown). Thus, although premature termination of transgene expression did have an impact on the cytokine profile of the memory population, the effect was modest.

FIG. 9.

Premature termination of transgene expression yields memory cells with a greater capacity for TNF-α production. Spleens and peripheral blood were harvested from mice 90 days postimmunization, and SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T cells were identified by intracellular cytokine staining. (A) Representative flow cytometry data. Left-hand dot plots reflect total lymphocytes following stimulation with SIINFEKL. The percentages of cells in the entire lymphocyte populations that are positive for IFN-γ are given next to the ellipses. The right-hand plots were gated on IFN-γ+ cells. These plots are representative of mice that were treated with DOX 30 days after immunization (DOX d+30) and mice that did not receive DOX (No DOX). (B) Percentages of IFN-γ+ cells that coproduce TNF-α in the spleen (left) and blood (right). Each histogram represents the mean ± standard error of the mean for five mice. *, significantly different from the No DOX group (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

rHuAd5 vectors have proven to be highly effective agents for producing protective immunity against a broad range of infectious agents and tumors in rodents and nonhuman primates (5, 8, 11, 12, 28, 29, 49). Therefore, understanding the mechanisms by which these vectors imprint and maintain the memory T-cell response can provide useful biological information regarding the nature of effective vaccines. The results of the study described here offer important new insights into the relationship between the longevity of transgene expression and the maintenance of CD8+ T-cell memory following immunization with rHuAd5. The temporal relationship between antigen expression and the development of CD8+ T-cell immunity remains a nebulous area, and the data in this report also provide novel information regarding the role for long-term, low-level antigen in the maintenance of CD8+ T-cell memory.

The requirement for persistent transgene expression throughout the expansion phase following rHuAd5 immunization appears to conflict with the “autopilot” hypothesis, which suggests that CD8+ T cells undergo an intrinsic program of expansion and differentiation that is executed following a short period of stimulation in vivo (estimated to be on the order of 24 h) (6). CD8+ T-cell expansion following infection with a number of acute agents (Plasmodium yoelii, Listeria monocytogenes, LCMV) does support the autopilot model, since antigen presentation persists for only a brief period (2 to 4 days) following infection (4, 13, 33, 48), yet the CD8+ T-cell population continues to expand beyond the point where antigen presentation ceases and subsequently contracts in a manner that appears to reflect an intrinsic program (4). This short-lived antigen presentation has been linked to a negative-feedback mechanism where recently activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes kill antigen-loaded dendritic cells and ultimately remove the antigen reservoir (13, 48). In contrast to those reports, removal of the antigen depot following herpes simplex virus type 1 infection or plasmid vaccination prior to the peak of the CD8+ T-cell response diminished the magnitude of the primary response (17, 40), findings similar to our observation with rHuAd5. Thus, although only a brief exposure of antigen is required to engage individual CD8+ T cells, maximal activation of CD8+ T-cell populations may require a longer period of antigen exposure, likely as a result of the asynchronous nature of antigen-presenting cell-T-cell interactions in vivo.

The need for continued transgene expression from the rHuAd5 vector beyond the peak of the CD8+ T-cell expansion phase to sustain the memory population may reflect a situation where naïve T cells are continuously recruited into the memory population to replace dying cells, or it may reflect a memory population that has become antigen dependent. We have previously reported that maintenance of the CD8+ T-cell memory population following rHuAd5 immunization does not require active thymopoiesis, which argues against the mechanism of continual recruitment of naïve T cells (51). Additional experiments from our lab have revealed that only naïve T cells engaged within the first 5 days following immunization are sustained in the memory population (J. Millar and J. Bramson, unpublished data). Thus, we do not believe that the requirement for persistent transgene expression to maintain the memory CD8+ T-cell population is due to continual recruitment of naïve T cells. Rather, we suspect that the early memory population produced by rHuAd5 is sustained by continual restimulation of the CD8+ T-cell population circulating in the periphery. This theory is consistent with the high levels of KLRG1 on the memory population, since KLRG1 is considered to be an indicator of recent and repetitive antigenic stimulation (42). In the same vein, it is noteworthy that the memory population produced by intramuscular immunization with rHuAd5 resembles the phenotype of CD8+ T cells that have been expanded by multiple rounds of immunization. Following secondary and tertiary stimulations, CD8+ T cells that were originally CD62Lhi preferentially retain an effector memory phenotype; they are slow to regain CD62L expression; only a small fraction of the cells produce IL-2; and they remain KLRG1 positive for a prolonged period (19, 31).

If our theory proposed in the preceding paragraph proves to be correct, then the data presented in this report can be reconciled with the “autopilot” hypothesis. Whereas a single CD8+ T-cell clone may undergo a fixed program of expansion and contraction, at the population level, extended availability of antigen may actually augment the magnitude of the CD8+ T-cell population by restimulating “memory” CD8+ T cells present in the primary response. Indeed, several reports have suggested that memory cells can be generated within the first few days of a primary response (3, 22, 47). Thus, individual naïve CD8+ T cells may undergo an intrinsic program of expansion and contraction during the primary response to rHuAd5 immunization. However, these events may not manifest at the level of the total CD8+ T-cell population, because the contraction phase of individual CD8+ T cells can be masked by the expansion of early memory cells that are triggered by persistent transgene expression, thereby extending the duration of the apparent expansion phase and diminishing the overall rate of contraction. It should be noted that extending the availability of antigen does not always increase the magnitude of the primary response or delay the rate of contraction (4, 14), so other factors may also be at play.

Premature termination of transgene expression following rHuAd5 immunization did not diminish the magnitude of the secondary response and may actually have been beneficial. These observations suggest that premature termination of transgene expression yields a memory CD8+ T-cell population with greater proliferative potential, consistent with the observation of elevated frequencies of CD62L+ cells. However, this observation may also reflect more-rapid clearance of antigen in the untreated group due to the higher frequency of SIINFEKL-specific effectors, as described in other reports (9, 47). Similar data were described in two recent reports investigating temporal regulation of transgene expression following immunization with plasmid DNA, where short-term transgene expression produced higher levels of central memory CD8+ T cells and a more robust secondary response (17, 37). These data indicate that the choice of promoter should be based on the application of the recombinant vaccine. Vectors used for priming CD8+ T-cell responses may benefit from promoters that are active only for a brief period following immunization, while boosting vectors may benefit from promoters that yield persistent expression to achieve a sustained effector population.

It is noteworthy that the memory CD8+ T-cell response in the mice that received DOX on day 7 exhibited the greatest proliferation following secondary challenge with vaccinia virus but provided the poorest protection in our experiments. Similar results were recently observed in a model of Listeria monocytogenes infection, where the primary CD8+ T-cell response was attenuated by treatment with antibiotics 24 h after primary infection. Although comparable frequencies of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were measurable in untreated and treated mice following secondary infection, the antibiotic-treated mice displayed impaired protection (43). These data indicate that proliferative capacity may provide only a limited measure of functional protective immunity. Bachmann and colleagues argued that resistance to vaccinia virus was not related to the proliferative capacity of the memory CD8+ T-cell population. Rather, they observed that the magnitude of the available effector population determined the degree of protection (2). We have observed similar results in our rHuAd5 immunization model (52). These combined results suggest that proliferative potential may not be a useful parameter for defining protective CD8+ T-cell memory against vaccinia virus. Other reports have argued that the proliferative capacity of the memory CD8+ T-cell population is important for protection against agents such as LCMV and Leishmania major and against some tumors (2, 26, 46, 55). Therefore, it is likely that the relationship between the proliferative capacity of the CD8+ T-cell population and protective immunity will need to be assessed on an individual basis for each pathogen.

Overall, this report demonstrates, for the first time, a causal link between the duration of transgene expression following immunization with a rHuAd5 vaccine and the maintenance of the CD8+ T-cell population. These data have important implications for the future design of rAd vaccines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to J.L.B. and R.J.P. from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (MOP-42433 and MOP-47819).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 September 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachmann, M. F., P. Wolint, K. Schwarz, P. Jager, and A. Oxenius. 2005. Functional properties and lineage relationship of CD8+ T cell subsets identified by expression of IL-7 receptor alpha and CD62L. J. Immunol. 175:4686-4696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachmann, M. F., P. Wolint, K. Schwarz, and A. Oxenius. 2005. Recall proliferation potential of memory CD8+ T cells and antiviral protection. J. Immunol. 175:4677-4685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badovinac, V. P., K. A. Messingham, A. Jabbari, J. S. Haring, and J. T. Harty. 2005. Accelerated CD8+ T-cell memory and prime-boost response after dendritic-cell vaccination. Nat. Med. 11:748-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badovinac, V. P., B. B. Porter, and J. T. Harty. 2002. Programmed contraction of CD8+ T cells after infection. Nat. Immunol. 3:619-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barouch, D. H., and G. J. Nabel. 2005. Adenovirus vector-based vaccines for human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Hum. Gene Ther. 16:149-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bevan, M. J., and P. J. Fink. 2001. The CD8 response on autopilot. Nat. Immunol. 2:381-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bramson, J. L., M. Hitt, J. Gauldie, and F. L. Graham. 1997. Pre-existing immunity to adenovirus does not prevent tumor regression following intratumoral administration of a vector expressing IL-12 but inhibits virus dissemination. Gene Ther. 4:1069-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capone, S., A. Meola, B. B. Ercole, A. Vitelli, M. Pezzanera, L. Ruggeri, M. E. Davies, R. Tafi, C. Santini, A. Luzzago, T. M. Fu, A. Bett, S. Colloca, R. Cortese, A. Nicosia, and A. Folgori. 2006. A novel adenovirus type 6 (Ad6)-based hepatitis C virus vector that overcomes preexisting anti-Ad5 immunity and induces potent and broad cellular immune responses in rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 80:1688-1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cockburn, I. A., S. Chakravarty, M. G. Overstreet, A. Garcia-Sastre, and F. Zavala. 2008. Memory CD8+ T cell responses expand when antigen presentation overcomes T cell self-regulation. J. Immunol. 180:64-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furth, P. A., L. St. Onge, H. Boger, P. Gruss, M. Gossen, A. Kistner, H. Bujard, and L. Hennighausen. 1994. Temporal control of gene expression in transgenic mice by a tetracycline-responsive promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:9302-9306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallo, P., S. Dharmapuri, B. Cipriani, and P. Monaci. 2005. Adenovirus as vehicle for anticancer genetic immunotherapy. Gene Ther. 12(Suppl. 1):S84-S91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao, W., A. C. Soloff, X. Lu, A. Montecalvo, D. C. Nguyen, Y. Matsuoka, P. D. Robbins, D. E. Swayne, R. O. Donis, J. M. Katz, S. M. Barratt-Boyes, and A. Gambotto. 2006. Protection of mice and poultry from lethal H5N1 avian influenza virus through adenovirus-based immunization. J. Virol. 80:1959-1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hafalla, J. C., A. Morrot, G. Sano, G. Milon, J. J. Lafaille, and F. Zavala. 2003. Early self-regulatory mechanisms control the magnitude of CD8+ T cell responses against liver stages of murine malaria. J. Immunol. 171:964-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hafalla, J. C., G. Sano, L. H. Carvalho, A. Morrot, and F. Zavala. 2002. Short-term antigen presentation and single clonal burst limit the magnitude of the CD8+ T cell responses to malaria liver stages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11819-11824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrington, L. E., R. van der Most, J. L. Whitton, and R. Ahmed. 2002. Recombinant vaccinia virus-induced T-cell immunity: quantitation of the response to the virus vector and the foreign epitope. J. Virol. 76:3329-3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hikono, H., J. E. Kohlmeier, S. Takamura, S. T. Wittmer, A. D. Roberts, and D. L. Woodland. 2007. Activation phenotype, rather than central- or effector-memory phenotype, predicts the recall efficacy of memory CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 204:1625-1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hovav, A. H., M. W. Panas, S. Rahman, P. Sircar, G. Gillard, M. J. Cayabyab, and N. L. Letvin. 2007. Duration of antigen expression in vivo following DNA immunization modifies the magnitude, contraction, and secondary responses of CD8+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 179:6725-6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huster, K. M., V. Busch, M. Schiemann, K. Linkemann, K. M. Kerksiek, H. Wagner, and D. H. Busch. 2004. Selective expression of IL-7 receptor on memory T cells identifies early CD40L-dependent generation of distinct CD8+ memory T cell subsets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:5610-5615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jabbari, A., and J. T. Harty. 2006. Secondary memory CD8+ T cells are more protective but slower to acquire a central-memory phenotype. J. Exp. Med. 203:919-932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson, S. S., J. E. Schmitz, M. J. Kuroda, P. F. McKay, S. M. Sumida, K. L. Martin, F. Yu, M. A. Lifton, D. A. Gorgone, and N. L. Letvin. 2005. Evaluation of CD62L expression as a marker for vaccine-elicited memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunology 116:443-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joshi, N. S., W. Cui, A. Chandele, H. K. Lee, D. R. Urso, J. Hagman, L. Gapin, and S. M. Kaech. 2007. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8+ T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity 27:281-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaech, S. M., J. T. Tan, E. J. Wherry, B. T. Konieczny, C. D. Surh, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat. Immunol. 4:1191-1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufman, D. R., J. Liu, A. Carville, K. G. Mansfield, M. J. Havenga, J. Goudsmit, and D. H. Barouch. 2008. Trafficking of antigen-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes to mucosal surfaces following intramuscular vaccination. J. Immunol. 181:4188-4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kedzierska, K., N. L. La Gruta, S. J. Turner, and P. C. Doherty. 2006. Establishment and recall of CD8+ T-cell memory in a model of localized transient infection. Immunol. Rev. 211:133-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kemball, C. C., E. D. Lee, V. Vezys, T. C. Pearson, C. P. Larsen, and A. E. Lukacher. 2005. Late priming and variability of epitope-specific CD8+ T cell responses during a persistent virus infection. J. Immunol. 174:7950-7960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klebanoff, C. A., L. Gattinoni, P. Torabi-Parizi, K. Kerstann, A. R. Cardones, S. E. Finkelstein, D. C. Palmer, P. A. Antony, S. T. Hwang, S. A. Rosenberg, T. A. Waldmann, and N. P. Restifo. 2005. Central memory self/tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells confer superior antitumor immunity compared with effector memory T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:9571-9576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krebs, P., E. Scandella, B. Odermatt, and B. Ludewig. 2005. Rapid functional exhaustion and deletion of CTL following immunization with recombinant adenovirus. J. Immunol. 174:4559-4566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane, C., J. Leitch, X. Tan, J. Hadjati, J. L. Bramson, and Y. Wan. 2004. Vaccination-induced autoimmune vitiligo is a consequence of secondary trauma to the skin. Cancer Res. 64:1509-1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, S., E. Locke, J. Bruder, D. Clarke, D. L. Doolan, M. J. Havenga, A. V. Hill, P. Liljestrom, T. P. Monath, H. Y. Naim, C. Ockenhouse, D. C. Tang, K. R. Van Kampen, J. F. Viret, F. Zavala, and F. Dubovsky. 2007. Viral vectors for malaria vaccine development. Vaccine 25:2567-2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, J., K. L. O'Brien, D. M. Lynch, N. L. Simmons, A. La Porte, A. M. Riggs, P. Abbink, R. T. Coffey, L. E. Grandpre, M. S. Seaman, G. Landucci, D. N. Forthal, D. C. Montefiori, A. Carville, K. G. Mansfield, M. J. Havenga, M. G. Pau, J. Goudsmit, and D. H. Barouch. 2009. Immune control of an SIV challenge by a T-cell-based vaccine in rhesus monkeys. Nature 457:87-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masopust, D., S. J. Ha, V. Vezys, and R. Ahmed. 2006. Stimulation history dictates memory CD8 T cell phenotype: implications for prime-boost vaccination. J. Immunol. 177:831-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McElrath, M. J., S. C. De Rosa, Z. Moodie, S. Dubey, L. Kierstead, H. Janes, O. D. Defawe, D. K. Carter, J. Hural, R. Akondy, S. P. Buchbinder, M. N. Robertson, D. V. Mehrotra, S. G. Self, L. Corey, J. W. Shiver, and D. R. Casimiro. 2008. HIV-1 vaccine-induced immunity in the test-of-concept Step Study: a case-cohort analysis. Lancet 372:1894-1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mercado, R., S. Vijh, S. E. Allen, K. Kerksiek, I. M. Pilip, and E. G. Pamer. 2000. Early programming of T cell populations responding to bacterial infection. J. Immunol. 165:6833-6839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ng, P., R. J. Parks, D. T. Cummings, C. M. Evelegh, and F. L. Graham. 2000. An enhanced system for construction of adenoviral vectors by the two-plasmid rescue method. Hum. Gene Ther. 11:693-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Obar, J. J., S. Fuse, E. K. Leung, S. C. Bellfy, and E. J. Usherwood. 2006. Gammaherpesvirus persistence alters key CD8 T-cell memory characteristics and enhances antiviral protection. J. Virol. 80:8303-8315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pascual, D. W., N. Walters, and P. Hillemeyer. 1998. Repeated intratracheal instillations of nonreplicating adenovirus 2 vector attenuate CTL responses and IFN-γ production. J. Immunol. 160:4465-4472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radcliffe, J. N., J. S. Roddick, F. K. Stevenson, and S. M. Thirdborough. 2007. Prolonged antigen expression following DNA vaccination impairs effector CD8+ T cell function and memory development. J. Immunol. 179:8313-8321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reyes-Sandoval, A., S. Sridhar, T. Berthoud, A. C. Moore, J. T. Harty, S. C. Gilbert, G. Gao, H. C. Ertl, J. C. Wilson, and A. V. Hill. 2008. Single-dose immunogenicity and protective efficacy of simian adenoviral vectors against Plasmodium berghei. Eur. J. Immunol. 38:732-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schirmbeck, R., J. Reimann, S. Kochanek, and F. Kreppel. 2008. The immunogenicity of adenovirus vectors limits the multispecificity of CD8 T-cell responses to vector-encoded transgenic antigens. Mol. Ther. 16:1609-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stock, A. T., S. N. Mueller, A. L. van Lint, W. R. Heath, and F. R. Carbone. 2004. Prolonged antigen presentation after herpes simplex virus-1 skin infection. J. Immunol. 173:2241-2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tatsis, N., J. C. Fitzgerald, A. Reyes-Sandoval, K. C. Harris-McCoy, S. E. Hensley, D. Zhou, S. W. Lin, A. Bian, Z. Q. Xiang, A. Iparraguirre, C. Lopez-Camacho, E. J. Wherry, and H. C. Ertl. 2007. Adenoviral vectors persist in vivo and maintain activated CD8+ T cells: implications for their use as vaccines. Blood 110:1916-1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thimme, R., V. Appay, M. Koschella, E. Panther, E. Roth, A. D. Hislop, A. B. Rickinson, S. L. Rowland-Jones, H. E. Blum, and H. Pircher. 2005. Increased expression of the NK cell receptor KLRG1 by virus-specific CD8 T cells during persistent antigen stimulation. J. Virol. 79:12112-12116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tseng, K. E., C. Y. Chung, W. S. H'ng, and S. L. Wang. 2009. Early infection termination affects number of CD8+ memory T cells and protective capacities in Listeria monocytogenes-infected mice upon rechallenge. J. Immunol. 182:4590-4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wherry, E. J., and R. Ahmed. 2004. Memory CD8 T-cell differentiation during viral infection. J. Virol. 78:5535-5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wherry, E. J., J. N. Blattman, K. Murali-Krishna, R. van der Most, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J. Virol. 77:4911-4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wherry, E. J., V. Teichgraber, T. C. Becker, D. Masopust, S. M. Kaech, R. Antia, U. H. von Andrian, and R. Ahmed. 2003. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Nat. Immunol. 4:225-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong, P., M. Lara-Tejero, A. Ploss, I. Leiner, and E. G. Pamer. 2004. Rapid development of T cell memory. J. Immunol. 172:7239-7245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong, P., and E. G. Pamer. 2003. Feedback regulation of pathogen-specific T cell priming. Immunity 18:499-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xing, Z., M. Santosuosso, S. McCormick, T. C. Yang, J. Millar, M. Hitt, Y. Wan, J. Bramson, and H. M. Vordermeier. 2005. Recent advances in the development of adenovirus- and poxvirus-vectored tuberculosis vaccines. Curr. Gene Ther. 5:485-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang, T. C., K. Dayball, Y. H. Wan, and J. Bramson. 2003. Detailed analysis of the CD8+ T-cell response following adenovirus vaccination. J. Virol. 77:13407-13411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang, T. C., J. Millar, T. Groves, N. Grinshtein, R. Parsons, S. Takenaka, Y. Wan, and J. L. Bramson. 2006. The CD8+ T cell population elicited by recombinant adenovirus displays a novel partially exhausted phenotype associated with prolonged antigen presentation that nonetheless provides long-term immunity. J. Immunol. 176:200-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang, T. C., J. Millar, T. Groves, W. Zhou, N. Grinshtein, R. Parsons, C. Evelegh, Z. Xing, Y. Wan, and J. Bramson. 2007. On the role of CD4+ T cells in the CD8+ T-cell response elicited by recombinant adenovirus vaccines. Mol. Ther. 15:997-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang, T. C., J. B. Millar, N. Grinshtein, J. Bassett, J. Finn, and J. L. Bramson. 2007. T-cell immunity generated by recombinant adenovirus vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 6:347-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang, Z. R., H. F. Wang, J. Zhao, Y. Y. Peng, J. Wang, B. A. Guinn, and L. Q. Huang. 2007. Recent developments in the use of adenoviruses and immunotoxins in cancer gene therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 14:599-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zaph, C., J. Uzonna, S. M. Beverley, and P. Scott. 2004. Central memory T cells mediate long-term immunity to Leishmania major in the absence of persistent parasites. Nat. Med. 10:1104-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]