Abstract

Murine norovirus (MNV) is a highly infectious but generally nonpathogenic agent that is commonly found in research mouse colonies in both North America and Europe. In the present study, the effects of acute and chronic infections with MNV on immune responses and recovery from concurrent Friend virus (FV) infections were investigated. No significant differences in T-cell or NK-cell responses, FV-neutralizing antibody responses, or long-term recovery from FV infection were observed. We conclude that concurrent MNV infections had no major impacts on FV infections.

Murine noroviruses (MNV) are small single-stranded RNA viruses related to human noroviruses, which are the major cause of nonbacterial gastroenteritis in humans. Noroviruses are highly contagious and spread through the fecal-oral route. Although MNV generally does not cause overt clinical signs in immunocompetent mice, its high prevalence of 32% in North American and European research colonies (15, 23) raises the concern that coinfection with MNV might significantly impact studies being done on other pathogens. In this regard, MNV was recently shown to affect disease progression in bacterium-induced inflammatory bowel disease (19). However, another recent study showed no major impact of MNV on adaptive immunity to coinfection with either vaccinia virus or influenza A virus (14).

Several MNV strains have been described, some of which persist indefinitely and could potentially cause long-term consequences. It has previously been shown that either acute or chronic infection of mice with lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus suppresses immune responses to coinfection with Friend virus (FV), a mouse retrovirus used by several research groups to study host-virus interactions (20, 25). Thus, there was a precedent for concern over the presence of intercurrent infections in FV studies. MNV replicates predominantly in gut enterocytes but also in antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as macrophages and dendritic cells (29, 31). MNV infection of APCs could produce downstream effects on FV-specific immune responses that could significantly alter recovery.

FV is a retroviral complex consisting of replication-competent Friend murine leukemia virus and a pathogenic but replication-defective virus known as spleen focus-forming virus. Spleen focus-forming virus encodes a defective env protein (gp55) that binds to erythropoietin receptors on erythroid progenitors, causing them to proliferate, resulting in high numbers of erythroid blasts in hematopoietic tissues such as the spleen. Unless controlled by immune responses, FV infection leads to lethal erythroleukemia in most strains of mice and produces long-term, low-level chronic infections in mice that recover from acute infection (13). Recovery from acute FV infection is highly dependent on both T-cell (11, 24) and virus-neutralizing antibody responses (3, 12, 21), and the quality of these responses is dependent on host genes such as major histocompatibility complex genes (2). To determine whether MNV coinfection affects FV-specific immune responses and ultimately recovery from FV infection, we chose medium-recovery (B10.A × A.BY)F1 mice bearing one susceptible major histocompatibility complex haplotype (H-2a) and one resistant haplotype (H-2b) (2). These mice have detectable, but not optimal, immune responses, thus providing a sensitive model to detect either increased or decreased immune responses due to MNV coinfection.

Acute FV infection induces splenomegaly accompanied by significant alterations in cell subset proportions in the spleen (25), so it was important to determine whether MNV infection alone causes disruptions that might confound data from MNV-FV coinfections. Mice were infected orally with 30 μl of MNV-CR6 p5 containing 3 × 107 PFU. This strain of MNV persists long term (14, 28). MNV shedding was detected by reverse transcription-PCR as previously described (5), except that the starting material was a fresh pellet of mouse feces dissolved by shaking in 0.5 ml phosphate-buffered saline, and RNA was purified with the MagMAX-96 kit from Applied Biosystems. The open reading frame encoding helicase/protease/polymerase was targeted with the forward primer sequence (5′ to 3′) AATCTATGCGCCTGGTTTGC, the reverse primer sequence CTCATCACCCGGGCTGTT, and the probe sequence CACGCCACTCCGC.

Of 20 mice tested for chronic virus shedding, 19 tested positive at 4 to 6 weeks postinfection (wpi). There were no false positives in any of the 13 uninfected controls (data not shown). All mice in the experiment were housed in microisolator cages in the same room, and aseptic husbandry techniques were used to prevent cross contamination. No spread of MNV to mice in uninfected cages was observed over the course of the experiments.

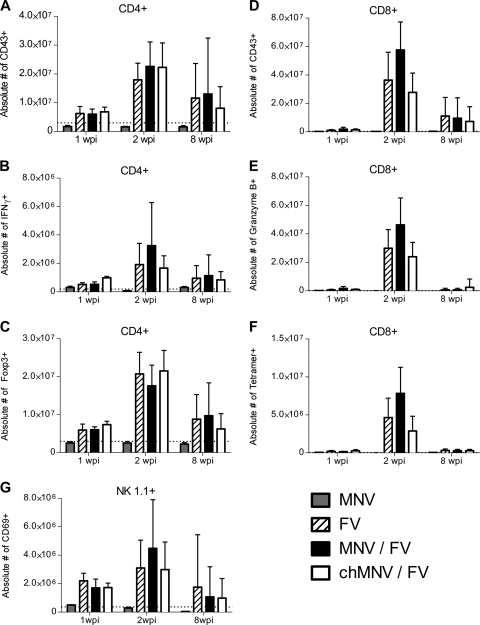

Spleen cells were examined by flow cytometry during both the acute (1 wpi) and chronic (8 wpi) phases of MNV infection as previously described (25). At 1 wpi, there was a slight but statistically significant increase in the percentage of CD11b+ cells (predominantly monocytes and neutrophils) in the spleen, but the difference was no longer significant at 8 wpi (Fig. 1A). No other significant changes in splenic cell subset proportions were observed in response to MNV infection (Fig. 1A and B).

FIG. 1.

Effect of MNV infection on splenic subset proportions. Mononuclear splenocytes from mice infected with MNV at 1 and 8 wpi were stained for (A) CD11b (macrophages), CD11c (dendritic cells), NK1.1 (NK cells), and Ter119 (erythroid progenitor cells) and for (B) CD4, CD8 (T cells), and CD19 (B cells). Bars indicate means and standard errors of the means. Significant difference from naïve controls (P < 0.05 by one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett's posttest) is indicated by an asterisk. For MNV-infected mice, data are from one experiment with six infected mice and three naïve mice (n = 3).

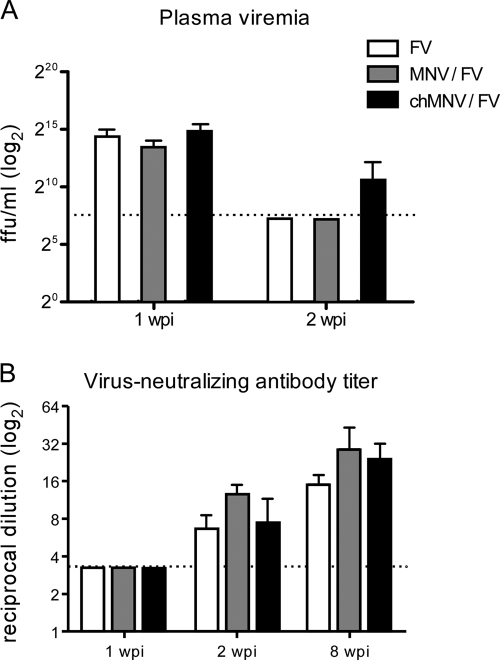

Splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were analyzed for expression of the activation-induced isoform of CD43. CD43 is a cell surface molecule expressed on effector T cells but not on naïve or memory T cells (10). Interestingly, T cells examined at 1, 2, and 8 wpi showed no activation by MNV alone (Fig. 2A and D). For coinfection studies, the mice were also infected with approximately 2,000 spleen focus-forming units of B-tropic FV complex as described previously (25). FV infections were done either coincidently with MNV (acute MNV) or at 4 wpi with MNV (chronic MNV). The presence of either acute or chronic MNV infection did not significantly alter FV-induced activation of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2A) or CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2D). Two functions important for the control of FV infections were examined, gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production by CD4+ T cells (18) and granzyme B production by CD8+ T cells (32, 34). There was no significant effect of MNV coinfection on the number of CD4+ T cells producing IFN-γ (Fig. 2B) or the number of CD8+ T cells producing granzyme B (Fig. 2E). CD8+ T cells were also analyzed with tetramers specific for an immunodominant FV epitope (1, 27). By 1 wpi, tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells expanded slightly in all groups infected with FV (P < 0.05) and reached levels of around five million per spleen by 2 wpi (Fig. 2F). The levels of expansion were variable from mouse to mouse, but no significant differences between FV-infected groups at any time point were observed.

FIG. 2.

Cellular activation and function during FV-MNV coinfection. Splenocyte subsets were stained as indicated for activation markers (A, D, and G), IFN-γ (B), granzyme B (E), tetramer reactivity (F), and the regulatory T-cell marker Foxp3 (C). Data were obtained from a B.D. LSR II flow cytometry instrument and analyzed with Flowjo software. Time points are weeks postinfection with MNV alone (MNV, n = 6) or FV alone (FV, n = 8), concurrent MNV and FV infection (MNV/FV, n = 7), and FV infection in mice chronically infected with MNV 4 weeks previously (chMNV/FV, n = 8). The data from two separate experiments were pooled. Error bars indicate means and standard deviations. At no time point were there any statistically significant differences between any of the FV-infected groups (as determined by either one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's multiple-comparison posttest or Dunnett's posttest with FV set as the control.) The dotted line represents the mean value for naïve mice. Mean values for naïve mice and MNV-infected mice in the CD8+ T-cell groups are barely above the x axis.

A hallmark of FV infection is the induction of CD4+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) (6, 17) with significant expansion at 2 wpi (22, 33). CD4+ FoxP3+ Tregs were analyzed at 1, 2, and 8 wpi, with expansion most evident at 2 wpi (Fig. 2C). Unlike FV infection, MNV infection by itself did not induce expansion of Tregs in the spleen. Again, MNV coinfections did not significantly alter the numbers of Tregs between groups of mice infected with FV. Natural killer (NK) cells also play a protective role in FV infections (16), and a significant proportion of splenic NK cells (NK1.1+) were activated in response to FV infection at all three time points (Fig. 2G). In contrast, there was no evidence of NK-cell activation in response to MNV only, and concurrent MNV infection did not significantly affect the NK response to FV infection at any of the time points.

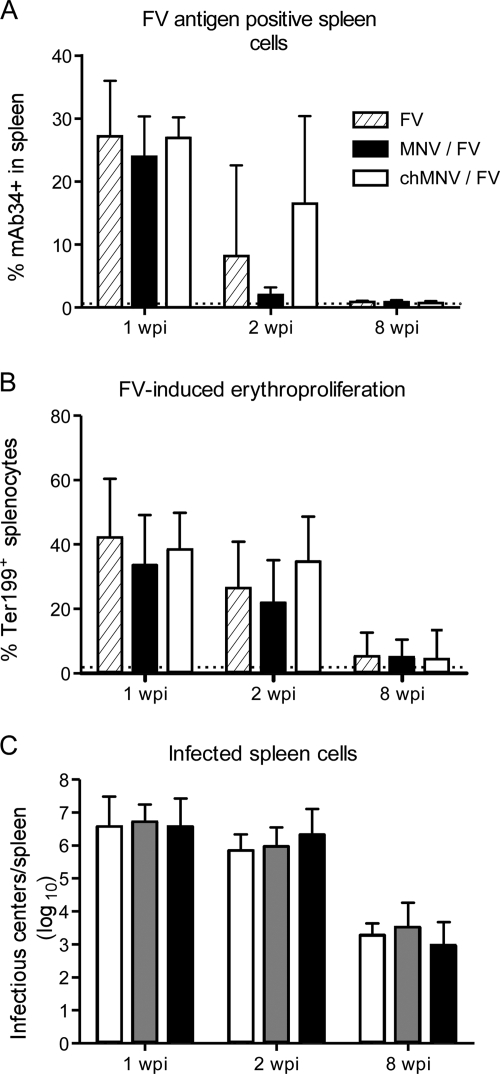

Acute FV infection of (B10.A × A.BY)F1 mice produces high levels of plasma viremia that are controlled by virus-neutralizing antibody responses (7, 26). At 1 wpi, all mice had very high viremia levels (Fig. 3A) with no detectable virus-neutralizing antibody responses (Fig. 3B). By 2 wpi, virus-neutralizing antibody responses were detectable and viremia was cleared in almost all of the mice. There were no significant differences between the groups, indicating that MNV coinfection did not alter either the antibody responses or viremia levels.

FIG. 3.

Viremia and virus-neutralizing antibody titers. (A) Mean plasma viremia titers (± the standard deviations; n = 4 per group for each time point) and (B) virus-neutralizing antibody titers were determined as previously described (21). The plasma dilution neutralizing 75% of Friend murine leukemia virus infectivity is shown. For FV infection, n = 8 for 1 and 2 wpi and 4 for 8 wpi; for MNV-FV coinfection, n = 5 to 8 per time point; for chronic MNV-FV coinfection, n = 8 per time point. The dotted lines represent the detection limit of the assays. The data were pooled from two separate experiments. At none of the time points tested did either acute or chronic MNV cause statistically significant differences between any of the test groups, as determined by one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's multiple-comparison posttest.

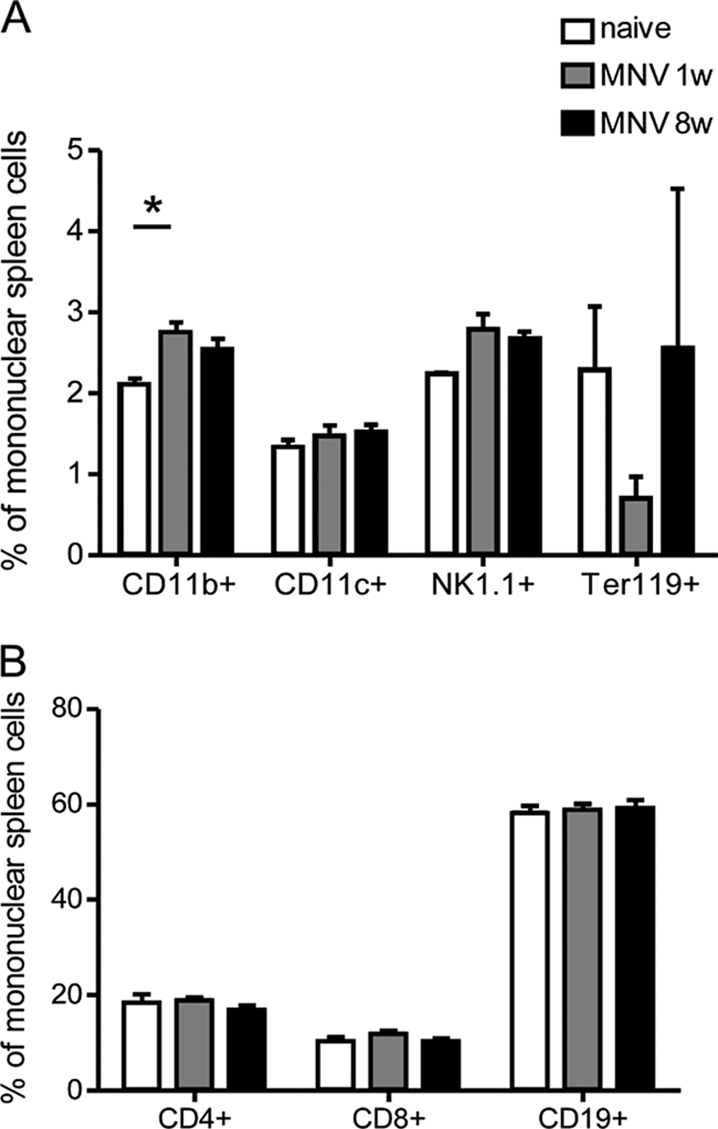

Levels of cellular infection in the spleen were analyzed by flow cytometry to detect expression of the FV-encoded glycosylated gag antigen (8, 9) and to measure the proliferation of erythroid precursors in the spleen. At 1 wpi, there was a high level of both viral antigen expression (monoclonal antibody 34+) and erythroid cell (Ter119+) proliferation in the spleen (Fig. 4A and B). By 2 wpi, FV infection was in decline. Although mice concurrently infected with MNV and FV appeared to have lower levels of FV antigen expression at 2 wpi, the difference was not statistically significant due to the high degree of mouse-to-mouse variability at this time point, when the antiviral immune response is becoming effective (Fig. 4A). There were also no significant differences associated with MNV coinfection in levels of erythroid cell proliferation or in levels of spleen cells producing live virus, as measured by infectious-center assays (Fig. 4C). All of the mice in all of the groups that recovered from acute FV infection survived the infection for 8 weeks and had equivalent levels of chronic FV infection at 8 wpi (Fig. 4C). Thus, there was no indication that MNV affected FV infection levels or recovery from infection.

FIG. 4.

Cell-associated FV titers and pathology. Bars indicate means and standard deviations. (A) Spleen cells were stained with monoclonal antibody (MAb) 34 to detect cell surface expression of the FV-encoded glycosylated gag antigen as described previously (25). The differences between the groups were not statistically significant. (B) Proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells was determined by staining for Ter119 (25). The dotted line represents mean levels in naïve control animals. (C) Infectious centers were determined as described previously (4). In panels A to C, the numbers of mice per group were as follows: for FV infection, n = 8 per time point; for MNV-FV coinfection, n = 7 to 13 per time point; for chronic MNV-FV coinfection, n = 7 to 8 per time point. The data shown were pooled from two separate experiments.

It has been shown that prior infections with a number of viruses can skew the T-cell repertoire and thereby alter responses to subsequent infections in either beneficial or harmful ways (30). No evidence of such changes was observed in this study, but detailed analyses of the repertoire are required to rule out such effects. However, we can conclude that neither acute nor chronic MNV infection impacted FV-induced immune responses or recovery from FV infection in any major way. This conclusion is basically the same as that reached in studies on the effects of MNV on influenza and vaccinia virus infections (14) but different from that reached in studies on bacterium-induced inflammatory bowel disease, where significant effects were observed (19). A very preliminary conclusion from these results is that the effects of concurrent norovirus infection might be more likely to affect infections of the gastrointestinal tract than of other locations. In the present experiments, little evidence of a systemic immune response to MNV was observed in the spleen, suggesting that the response might be localized to gut-associated lymphatic tissues. It is also possible that the difference between bacterial and viral infections is an important one. It remains important to investigate each type of infection being studied and also to keep in mind that there are numerous strains of MNV (28), some of which might cause different effects. Thus, care must be taken not to generalize to other coinfecting viruses or to other norovirus strains.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Herbert W. Virgin for sharing MNV stocks with us and providing important advice and criticism.

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the NIAID, NIH.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 October 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen, W., H. Qin, B. Chesebro, and M. A. Cheever. 1996. Identification of a gag-encoded cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope from FBL-3 leukemia shared by Friend, Moloney, and Rauscher murine leukemia virus-induced tumors. J. Virol. 70:7773-7782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chesebro, B., M. Miyazawa, and W. J. Britt. 1990. Host genetic control of spontaneous and induced immunity to Friend murine retrovirus infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 8:477-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesebro, B., and K. Wehrly. 1979. Identification of a non-H-2 gene (Rfv-3) influencing recovery from viremia and leukemia induced by Friend virus complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:425-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chesebro, B., K. Wehrly, K. Watson, and K. Chesebro. 1978. Murine leukemia virus infectious centers are dependent on the rate of virus production by infected cells. Virology 84:222-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimcheff, D. E., S. Askovic, A. H. Baker, C. Johnson-Fowler, and J. L. Portis. 2003. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is a determinant of retrovirus-induced spongiform neurodegeneration. J. Virol. 77:12617-12629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dittmer, U., H. He, R. J. Messer, S. Schimmer, A. R. Olbrich, C. Ohlen, P. D. Greenberg, I. M. Stromnes, M. Iwashiro, S. Sakaguchi, L. H. Evans, K. E. Peterson, G. Yang, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2004. Functional impairment of CD8+ T cells by regulatory T cells during persistent retroviral infection. Immunity 20:293-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doig, D., and B. Chesebro. 1979. Anti-Friend virus antibody is associated with recovery from viremia and loss of viral leukemia cell-surface antigens in leukemic mice. Identification of Rfv-3 as a gene locus influencing antibody production. J. Exp. Med. 150:10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards, S. A., and H. Fan. 1979. gag-related polyproteins of Moloney murine leukemia virus: evidence for independent synthesis of glycosylated and unglycosylated forms. J. Virol. 30:551-563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans, L. H., S. Dresler, and D. Kabat. 1977. Synthesis and glycosylation of polyprotein precursors to the internal core proteins of Friend murine leukemia virus. J. Virol. 24:865-874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrington, L. E., M. Galvan, L. G. Baum, J. D. Altman, and R. Ahmed. 2000. Differentiating between memory and effector CD8 T cells by altered expression of cell surface O-glycans. J. Exp. Med. 191:1241-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasenkrug, K. J. 1999. Lymphocyte deficiencies increase susceptibility to Friend virus-induced erythroleukemia in Fv-2 genetically resistant mice. J. Virol. 73:6468-6473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasenkrug, K. J., D. M. Brooks, and B. Chesebro. 1995. Passive immunotherapy for retroviral disease: influence of major histocompatibility complex type and T-cell responsiveness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:10492-10495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasenkrug, K. J., and U. Dittmer. 2007. Immune control and prevention of chronic Friend retrovirus infection. Front. Biosci. 12:1544-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hensley, S. E., A. K. Pinto, H. D. Hickman, R. J. Kastenmayer, J. R. Bennink, H. W. Virgin, and J. W. Yewdell. 2009. Murine norovirus infection has no significant effect on adaptive immunity to vaccinia virus or influenza A virus. J. Virol. 83:7357-7360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu, C. C., C. E. Wobus, E. K. Steffen, L. K. Riley, and R. S. Livingston. 2005. Development of a microsphere-based serologic multiplexed fluorescent immunoassay and a reverse transcriptase PCR assay to detect murine norovirus 1 infection in mice. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12:1145-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwanami, N., A. Niwa, Y. Yasutomi, N. Tabata, and M. Miyazawa. 2001. Role of natural killer cells in resistance against Friend retrovirus-induced leukemia. J. Virol. 75:3152-3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwashiro, M., R. J. Messer, K. E. Peterson, I. M. Stromnes, T. Sugie, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2001. Immunosuppression by CD4+ regulatory T cells induced by chronic retroviral infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:9226-9230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwashiro, M., K. Peterson, R. J. Messer, I. M. Stromnes, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2001. CD4+ T cells and gamma interferon in the long-term control of persistent Friend retrovirus infection. J. Virol. 75:52-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lencioni, K. C., A. Seamons, P. M. Treuting, L. Maggio-Price, and T. Brabb. 2008. Murine norovirus: an intercurrent variable in a mouse model of bacteria-induced inflammatory bowel disease. Comp. Med. 58:522-533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marques, R., I. Antunes, U. Eksmond, J. Stoye, K. Hasenkrug, and G. Kassiotis. 2008. B lymphocyte activation by coinfection prevents immune control of Friend virus infection. J. Immunol. 181:3432-3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messer, R. J., U. Dittmer, K. E. Peterson, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2004. Essential role for virus-neutralizing antibodies in sterilizing immunity against Friend retrovirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:12260-12265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers, L., R. J. Messer, A. B. Carmody, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2009. Tissue specific abundance of regulatory T cells correlates with CD8+ T cell dysfunction and chronic retrovirus loads. J. Immunol. 183:1636-1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pritchett-Corning, K. R., J. Cosentino, and C. B. Clifford. 2009. Contemporary prevalence of infectious agents in laboratory mice and rats. Lab. Anim. 43:165-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson, M. N., G. J. Spangrude, K. Hasenkrug, L. Perry, J. Nishio, K. Wehrly, and B. Chesebro. 1992. Role and specificity of T-cell subsets in spontaneous recovery from Friend virus-induced leukemia in mice. J. Virol. 66:3271-3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson, S. J., C. G. Ammann, R. J. Messer, A. B. Carmody, L. Myers, U. Dittmer, S. Nair, N. Gerlach, L. H. Evans, W. A. Cafruny, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2008. Suppression of acute anti-Friend virus CD8+ T-cell responses by coinfection with lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus. J. Virol. 82:408-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santiago, M. L., M. Montano, R. Benitez, R. J. Messer, W. Yonemoto, B. Chesebro, K. J. Hasenkrug, and W. C. Greene. 2008. Apobec3 encodes Rfv3, a gene influencing neutralizing antibody control of retrovirus infection. Science 321:1343-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schepers, K., M. Toebes, G. Sotthewes, F. A. Vyth-Dreese, T. A. Dellemijn, C. J. Melief, F. Ossendorp, and T. N. Schumacher. 2002. Differential kinetics of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in the regression of retrovirus-induced sarcomas. J. Immunol. 169:3191-3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thackray, L. B., C. E. Wobus, K. A. Chachu, B. Liu, E. R. Alegre, K. S. Henderson, S. T. Kelley, and H. W. Virgin. 2007. Murine noroviruses comprising a single genogroup exhibit biological diversity despite limited sequence divergence. J. Virol. 81:10460-10473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Virgin, H. W. 2005. Immune regulation of viral infection and vice versa. Immunol. Res. 32:293-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welsh, R. M., S. K. Kim, M. Cornberg, S. C. Clute, L. K. Selin, and Y. N. Naumov. 2006. The privacy of T cell memory to viruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 311:117-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wobus, C. E., S. M. Karst, L. B. Thackray, K. O. Chang, S. V. Sosnovtsev, G. Belliot, A. Krug, J. M. Mackenzie, K. Y. Green, and H. W. Virgin. 2004. Replication of norovirus in cell culture reveals a tropism for dendritic cells and macrophages. PLoS Biol. 2:e432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zelinskyy, G., S. Balkow, S. Schimmer, K. Schepers, M. M. Simon, and U. Dittmer. 2004. Independent roles of perforin, granzymes, and Fas in the control of Friend retrovirus infection. Virology 330:365-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zelinskyy, G., A. R. Kraft, S. Schimmer, T. Arndt, and U. Dittmer. 2006. Kinetics of CD8+ effector T cell responses and induced CD4+ regulatory T cell responses during Friend retrovirus infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 36:2658-2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zelinskyy, G., S. J. Robertson, S. Schimmer, R. J. Messer, K. J. Hasenkrug, and U. Dittmer. 2005. CD8+ T-cell dysfunction due to cytolytic granule deficiency in persistent Friend retrovirus infection. J. Virol. 79:10619-10626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]