Abstract

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), a ligand-activated transcription factor, is known to mediate a wide variety of pharmacological and toxicological effects caused by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Recent studies have revealed that AhR is involved in the normal development and homeostasis of many organs. Here, we demonstrate that AhR knockout (AhR KO) mice are hypersensitive to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced septic shock, mainly due to the dysfunction of their macrophages. In response to LPS, bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) of AhR KO mice secreted an enhanced amount of interleukin-1β (IL-1β). Since the enhanced IL-1β secretion was suppressed by supplementing Plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 (Pai-2) expression through transduction with Pai-2-expressing adenoviruses, reduced Pai-2 expression could be a cause of the increased IL-1β secretion by AhR KO mouse BMDM. Analysis of gene expression revealed that AhR directly regulates the expression of Pai-2 through a mechanism involving NF-κB but not AhR nuclear translocator (Arnt), in an LPS-dependent manner. Together with the result that administration of the AhR ligand 3-methylcholanthrene partially protected mice with wild-type AhR from endotoxin-induced death, these results raise the possibility that an appropriate AhR ligand may be useful for treating patients with inflammatory disorders.

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a member of the basic helix-loop-helix/Per-Arnt-Sim homology superfamily and is involved in the induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes and the susceptibility of cells to a variety of cytotoxicities induced by dioxins (9). AhR is a ligand-activated transcription factor activated by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), such as 3-methylcholanthrene (3MC) and 2′,3′,7′,8′-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). Under normal conditions, AhR exists in the cytoplasm in a complex with Hsp90, XAP2, and p23 (22). After binding a ligand, AhR translocates into the nucleus where it dimerizes with its partner molecule, AhR nuclear translocator (Arnt), and acts as a transcriptional activator to regulate the expression of target genes, such as those expressing drug-metabolizing cytochrome P450 (Cyp1a1, 1a2, and 1b1) and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase (Nqo), by binding to xenobiotic response element (XRE) sequences in their promoter regions (9). By using AhR knockout (AhR KO) mice, it has been demonstrated that AhR is essential not only for the induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes but also for most, if not all, of the toxicological effects caused by TCDD, including immunosuppression, thymic atrophy, teratogenesis, and hyperplasia (6, 7, 17, 24), the mechanisms for which are largely unknown. Recently, careful investigation into the loss of functions in AhR KO mice has also revealed that AhR is involved in the normal development of several organs, including the liver, heart, vascular tissues, and reproductive organs (1, 2, 6, 8, 15, 24). In addition, AhR has been found to play a key role in the differentiation of regulatory T cells Treg, Th17, and Th1 from naive CD4 T cells by regulating their expression of Foxp3 or by as-yet-unknown mechanisms (14, 20, 23, 32). From these studies, one of the general features of AhR that begins to emerge is that it serves as a multifunctional regulator in a large number of areas, ranging from drug metabolism to innate immunity for protection against invasive xenobiotics. In the work presented here, we demonstrated that AhR KO mice were hypersensitive to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced septic shock, mainly due to the dysfunction of their macrophages. AhR KO mouse macrophages secreted an enhanced amount of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in response to LPS treatment and had markedly reduced Plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 (Pai-2) mRNA concentrations, as revealed by DNA microarray analysis. Pai-2 was reported to be a negative regulator of IL-1β secretion through its inhibition of caspase-1 (10), suggesting that the enhanced secretion of IL-1β by AhR KO macrophages in response to LPS may have been due to the reduced level of Pai-2. We showed that AhR directly regulates the expression of inhibitory Pai-2, in an LPS-dependent manner, through a mechanism involving NF-κB but not Arnt.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

AhR knockout (AhR KO) mice were generated as described previously (17). These mice were back-crossed with C57BL/6J mice at least 10 times. Age-matched mice (10 weeks) were intraperitoneally injected with 20 mg of LPS/kg of body weight. Mice with floxed Arnt (30) and AhR (Jackson laboratory) alleles were crossed to LysM Cre mice to specifically delete these genes in their macrophages. AhRflox/− and AhRflox/−::LysM Cre mice were generated by mating AhRflox/flox::LysM Cre and AhR−/− (AhR KO) mice. These age-matched mice (9 to 11 weeks old) were intraperitoneally injected with 25 mg LPS/kg. Mouse survival was checked every 6 or 12 h. 3MC (Wako, Osaka) at 10 μl (4 mg/ml 3MC)/g of body weight or 10 μl corn oil/g was intraperitoneally injected. After 2 h, each mouse was intraperitoneally injected with 30 mg LPS/kg. LPS (from Escherichia coli 0111:B4) was purchased from Sigma.

Preparation of macrophages.

Bone marrow cells were obtained from the femurs of 8- to 12-week-old mice. The bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) used for each experiment were isolated by culturing bone marrow cells in the presence of 10 ng/ml granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (PeproTech) for 7 days and washing the attached cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times. For cytokine assays, washed cells were collected with a scraper, plated at 2 × 106 cells/ml in 96-well plates, and cultured with 10 ng/ml LPS for 8 h.

For isolation of peritoneal exudate macrophages (PEMs), mice were intraperitoneally injected with 2 ml of 4% thioglycolate. Peritoneal cells were isolated from exudates of the peritoneal cavity 3 days after injection, incubated for 3 h in appropriate plates, and washed with PBS. The adherent cells were used for experiments.

Measurement of cytokines.

Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 20 mg/kg LPS and bled 2 h after injection. Plasma concentrations of IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-6, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), IL-12, and IL-18 were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Biosource). BMDM of mice with wild-type AhR (AhR WT mice) and AhR KO at 2 × 106 cells/ml were incubated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 8 h, and their culture supernatants were assessed for cytokines using mouse TNF-α and IL-1β ELISAs (Biosource).

Cell culture.

All cells were maintained in RPMI medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone) and penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) under 5.0% CO2 at 37°C.

Caspase inhibitors.

BMDM of AhR KO mice at 2 × 106 cells/ml were incubated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 80 μM Z-YVAD-FMK (caspase-1 inhibitor VI; Merck) or 100 μM Z-VAD-FMK (caspase inhibitor VI; Merck) for 30 min before LPS (10 ng/ml) stimulation. The BMDM were incubated for 8 h, and their culture supernatants were assessed for cytokines using a mouse IL-1β ELISA (Biosource).

Virus infections.

Adenoviruses expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP), human Pai-2 (hPai-2), and human Bcl-2 (hBcl-2) were purchased from Vector Biolabs (Philadelphia). BMDM from AhR KO mice were infected for 12 h with adenoviruses expressing GFP, hPai-2, and hBcl-2 at a multiplicity of infection of 100. Infected BMDM were washed with PBS, followed by 12 h of incubation. As it was reported that adenoviral vectors enhanced IL-1β secretion in macrophages (19), IL-1β levels were investigated in these incubation supernatants by ELISA. At this point, no IL-1β was observed in the supernatants. Therefore, the cells were washed, collected with a scraper, and plated at 2 × 106 cells/ml in 96-well plates. The cells were treated with 10 ng/ml of LPS for an additional 8 h.

Retroviral infection was performed as follofws: pQC-mAhR, a cloned murine AhR (mAhR) fragment in pQCXIN (Clontech), and pQCXLN for LacZ expression (as a control) were transfected into PT67 cells that were then cultured for 24 h. The culture medium was replaced with fresh medium, and the culture was continued for an additional 24 h. This culture medium was used as the retrovirus particle source.

Microarray analysis.

Total RNA samples were purified using Isogen before being processed and hybridized to Affymetrix mouse genome 430 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix). The experimental procedures for the GeneChip analyses were performed according to the Affymetrix technical manual.

Generation of stable transformant cell lines.

ANA-1 cells were the kind gift of L. Varesio (3). ANA-1 cells were transduced with LacZ- or AhR-expressing retroviruses in a suspension with 8 mg/ml of Polybrene. One day after infection, the infected cells were replated and incubated in a selection medium containing 0.5 mg/ml of Geneticin (Gibco).

Plasmids.

pcDNA3-p65 and pcDNA3-AhR were generated by inserting AhR and p65 cDNA fragments, excised from pBS-mAhR and pBS-mp65 (murine p65), into the pcDNA3 vector. The 2.7-kb fragment upstream of the Pai-2 transcription start site was generated by PCR (primers 5′-gaagcttGGGTTGCAGATCCCTTTAGC-3′ and 5′-ccatggtggCTGACACACAGGAAATGCTTC-3′; lowercase indicates restriction site sequences for cloning), using a BAC vector carrying the Pai-2 gene as a template, and then cloned into the pBS vector. After sequencing, the construct was cleaved with HindIII/NcoI, and the isolated insert was cloned into the HindIII/NcoI-digested pGL4.10 (Promega) to produce pGL4-Pai-2 (−2.7 kb). The 0.8-kb fragment upstream of the Pai-2 transcription start site was generated by PCR (primers 5′-ggaattcGAGAAGTGATCTGGTAGATG-3′ and 5′-ccatggtggCTGACACACAGGAAATGCTTC-3′) using pGL4-Pai-2 (−2.7 kb) as a template and cloned into the pBS vector. After sequencing, the construct was cleaved with HindIII/NcoI, and the isolated insert was cloned into the HindIII/NcoI-digested pGL4.10 (Promega) to produce pGL4-Pai-2 (−0.8 kb). pGL4-Pai-2 (−0.55 kb) was produced by cleaving pGL4-Pai-2 (−2.7 kb) with NdeI/EcoRV. pGL4-Pai-2 (−0.1 kb) was generated in a similar manner, using primers 5′-GATGTCTTTATGAGTAAAATGTTGAATCA-3′ and 5′-ccatggtggCTGACACACAGGAAATGCTTC-3′. pGL4-Pai-2 (−0.55 kb C/EBPβ mutant) was generated by site-directed mutagenesis using a Sculptor in vitro mutagenesis system (Amersham) with pGL4-Pai-2 (−0.55 kb) as a template and primer pair 5′-GATTTAAAATTGGAAAggGCTAAATTCTTGAATTTTGAATGACATCAC-3′ and 5′-GTGATGTCATTCAAAATTCAAGAATTTAGCccTTTCCAATTTTAAATC-3′.

RNA preparation and reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR).

Total RNA was prepared using Isogen (Nippon Gene, Tokyo) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA synthesis from 1 μg of total RNA was carried out using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, United States). Real-time PCR was performed using an ABI7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and Platinum SYBR green quantitative PCR SuperMix (Invitrogen, United States). Each sample was normalized to the expression of β-actin as a control. The primer sequences were as follows: Pai-2, 5′-GCATCCACTGGCTTGGAA-3′ and 5′-GGGAATGTAGACCACAACATCAT-3′; Bcl-2, 5′-GTGGTGGAGGAACTCTTCAGGGATG-3′ and 5′-GGTCTTCAGAGACAGCCAGGAGAAATC-3′; AhR, 5′-TTCTATGCTTCCTCCACTATCCA-3′ and 5′-GGCTTCGTCCACTCCTTGT-3′; Arnt, 5′-GGACGGTGCCATCTCGAC-3′ and 5′-CATCTGGTCATCATCGCATC-3′: Mmp-8, 5′-CCACACACAGCTTGCCAATGCCT-3′ and 5′-GGTCAGGTTAGTGTGTGTCCACT-3′; Nqo1, 5′-TTTAGGGTCGTCTTGGCAAC-3′ and 5′-AGTACAATCAGGGCTCTTCTCG-3′; AhR repressor, 5′-CCTGTCCCGGGATCAAAGATG-3′ and 5′-CTCACCACCAGAGCGAAGCCATTGA-3′; IL-1β, 5′-CTGAAGCAGCTATGGCAACT-3′ and 5′-GGATGCTCTCATCTGGACAG-3′; TNF-α, 5′-CTGTAGCCCACGTCGTAGC-3′ and 5′-TTGAGATCCATGCCGTTG-3′; Cox-2, 5′-GCATTCTTTGCCCAGCACTT-3′ and 5′-AGACCAGGCACCAGACCAAAG-3′; β-actin, 5′-GACAGGATGCAGAAGGAGAT-3′ and 5′-TTGCTGATCCACATCTGCTG-3′; hPai-2, 5′-CCCAGAACCTCTTCCTCTCC-3′ and 5′-CATTGGCTCCCACTTCATTA-3′; and hBcl-2, 5′-GTGTGTGGAGAGCGTCAACC-3′ and 5′-GAGACAGCCAGGAGAAATCAAA-3′.

Reporter assays.

All luciferase assays were performed using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega), with some modifications. RAW 264.7 cells (2.0 × 104 cells/well) were plated in 24-well plates 24 h prior to transfection. Cells were cotransfected with 100 ng pGL4-Pai-2 (various lengths in kilobases) (see “Plasmids”), 1 ng Renilla luciferase (as an internal control), and 1 ng pcDNA3-p65 and/or pcDNA3-AhR using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocol. All cells were incubated for 12 h at 37°C after transfection, treated with 10 ng/ml LPS, and incubated for an additional 6 h.

Co-IP assays.

AhR WT PEMs or transfected 293T cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, followed by buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 125 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 20 mM ZnCl2, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate (31). The cells were harvested by scraping, centrifuged at 5,000 rpm at 4°C for 5 min, and suspended in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The cells were vortexed and placed on ice for 10 min. The samples were then centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were saved as whole-cell lysates.

The prepared whole-cell lysate (250 μl) was incubated with anti-immunoglobulin G, anti-AhR antibody, or anti-p65 for 2 h at 4°C. The reaction mixture was supplemented with 20 μl of protein A-agarose beads (Amersham). After being incubated for an additional 1 h at 4°C, the beads were washed three times with IP buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail and resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer. The coimmunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and Western blot analysis was performed.

ChIP assays.

Chromatin IP (ChIP) assays were performed with PEMs from AhR WT and AhR KO mice. PEMs were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 60 min and then fixed with formaldehyde for 10 min. The cells were lysed and sheared by sonication. The lysis solution was incubated with immunoglobulin G or preimmune serum and protein A-agarose for 2 h to remove nonspecific DNA binding. The solution was incubated overnight with a specific antibody, followed by incubation with protein A-agarose saturated with salmon sperm DNA. Precipitated DNA was analyzed by real-time PCR using primer pair 5′-GGAAGTTCCCTGAGGCTTATAGG-3′ and 5′-ATGGAAGCACATACATAAGAACATGG-3′ for the NF-κB binding site of Pai-2, 5′-TGAGTGTGAGTGGTGCAGATTAC-3′ and 5′-CCTCCCACACAGCTCTTTTTTC-3′ for mPai-2 TATA, 5′-CGGAGGGTAGTTCCATGAAA-3′ and 5′-CAGGCTTTTACCCACGCAAA-3′ for the NF-κB binding site of mCox2, and 5′-CGCAACTCACTGAAGCAGAG-3′ and 5′-TCCTTCGTGAGCAGAGTCCT-3′ for mCox-2 TATA. The antibodies used were as follows: anti-AhR serum, preimmune serum, anti-p65, and anti-PolII antibodies (Santa Cruz).

Western blot analyses.

Cells were dissolved in SDS sample buffer, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE for Western blot analysis. The proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and blocked in 3% skim milk for 30 min. Each antibody was used as a primary reagent, and after being washed three times with Tris-borate-EDTA containing 0.1% Triton X-100, membranes were incubated with species-specific horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Zymed). The protein-antibody complexes were visualized by using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Nuclear extracts were prepared by a standard method (25). The antibodies used were as follows: anti-Arnt serum (28); anti-AhR (Biomol); anti-Pai-2, anti-p65, and antilamin antibodies (Santa Cruz); and antitubulin antibody (Sigma).

RESULTS

High susceptibility of AhR-deficient mice to LPS-induced endotoxin shock.

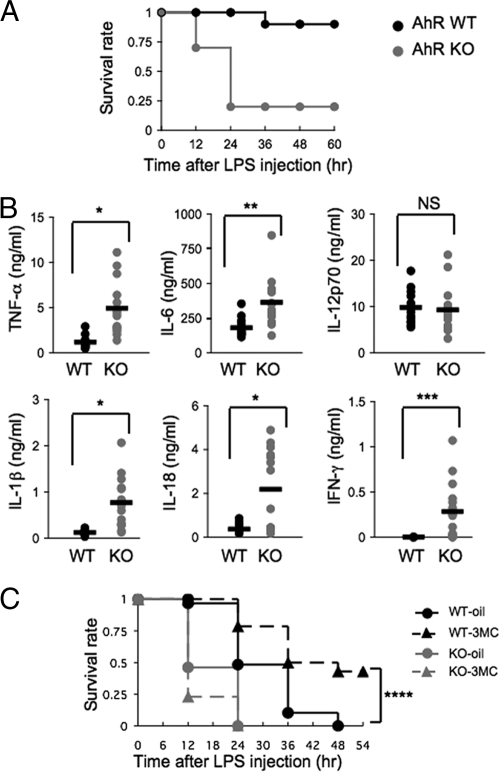

To investigate the function of AhR in acute inflammation in vivo, we performed studies of experimental LPS-induced endotoxin shock. For these studies, 10-week-old AhR WT and AhR KO mice were injected intraperitoneally with 20 mg/kg LPS. After 24 h, while all of the AhR WT mice survived, most of the AhR KO mice (80%) had died (Fig. 1A). These data indicate that AhR-deficient mice were highly susceptible to LPS-induced endotoxin shock. To explain the increased sensitivity of AhR KO mice to septic shock, the plasma concentrations of several inflammatory cytokines were measured 2 h after LPS challenge. Consistent with the enhanced susceptibility of AhR KO mice to the LPS treatment, AhR KO mice had marked increases in plasma IL-1β, IL-18, and TNF-α levels (P < 0.001), with modest increases in IL-6 and IFN-γ (Fig. 1B). In contrast, there was no difference in plasma IL-12p70 levels (Fig. 1B). Administration of 3MC, an AhR ligand, before LPS treatment (30 mg/kg) made the AhR WT mice significantly more resistant to septic shock than the mice that were not treated with 3MC (P = 0.002) (Fig. 1C). Together with the fact that there was essentially no effect of 3MC on AhR KO mice, these results suggested that activated AhR could play an anti-inflammatory role.

FIG. 1.

High susceptibility of AhR KO mice to LPS-induced endotoxin shock. (A) Survival of AhR WT and AhR KO mice (n = 10) after LPS challenge (20 mg/ml). (B) TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12p70, IL-1β, IL-18, and IFN-γ plasma levels 2 h after LPS challenge (20 mg/ml). Horizontal bars show the mean results. (C) Partial protection of AhR WT mice from septic shock by intraperitoneal injection of 3MC at 2 h before LPS challenge (30 mg/ml) and survival of corn oil-injected mice. AhR WT-oil, n = 29; AhR WT-3MC, n = 28; AhR KO-oil, n = 13; AhR KO-3MC, n = 13. *, P < 0.001; **, P = 0.001; ***, P < 0.005; ****, P = 0.002; NS, not significant.

Increased susceptibility of mice with AhR KO macrophages to LPS-induced endotoxin shock.

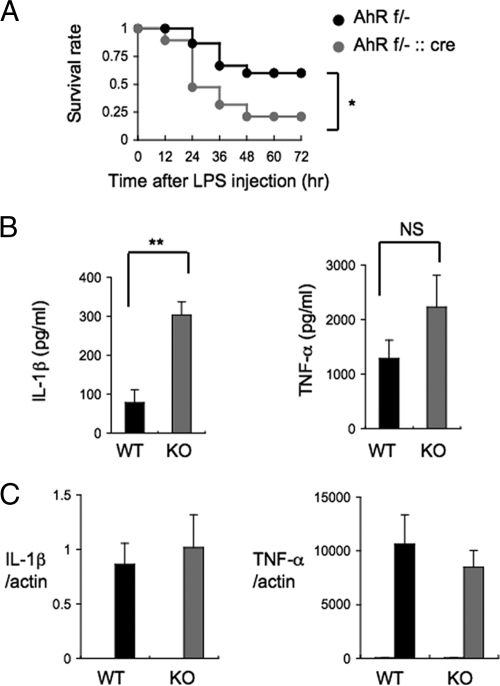

Since macrophages play an important role in sensitivity to LPS toxicity, we generated mice with macrophages deficient in AhR (AhRflox/−::LysM Cre [ΔAhR Mac] mice) to evaluate the contribution of macrophages to the LPS hypersensitivity of AhR KO mice. When ΔAhR Mac and control mice (AhRflox/−) were injected intraperitoneally with 25 mg/kg LPS, most of the ΔAhR Mac mice (80%) had died at 48 h after LPS challenge, while 60% of the control mice survived (P = 0.03) (Fig. 2A). Together with the previous results, these data showed that dysfunctional AhR-deficient macrophages are one of the main causes of LPS hypersensitivity in AhR KO mice.

FIG. 2.

LPS induces abnormal secretion of IL-1β by BMDM from AhR KO mice. (A) Survival of AhRflox/− (AhR f/−; n = 15) and AhRflox/−::LysM Cre (AhR f/−::cre; n = 19) mice after LPS challenge (25 mg/ml). (B) IL-1β and TNF-α levels in the culture supernatants of AhR WT and AhR KO BMDM 8 h after LPS stimulation (10 ng/ml) (n = 4). (C) Relative expression levels of IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA 4 h after LPS stimulation (10 ng/ml) of AhR WT and AhR KO BMDM. Gray and black bars show results with LPS; white bars show results for untreated cells. Error bars show standard deviations. *, P = 0.03; **, P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

Elevated IL-1β secretion from AhR KO BMDM in response to LPS.

To further investigate the cause of the aberrant cytokine secretion by LPS-challenged AhR KO mice, we next asked if there were any differences in the production of proinflammatory cytokines by AhR WT and AhR KO mouse BMDM in response to LPS stimulation. Macrophages from the bone marrow of AhR WT and AhR KO mice were challenged with 10 ng/ml LPS for 8 h, and then the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in the culture medium were assessed by ELISA. Compared to the levels in AhR WT BMDM, the levels of IL-1β secretion by AhR KO BMDM were markedly elevated, along with slight increases in TNF-α, in response to LPS treatment (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B, left). However, IL-1β mRNA levels were not altered between AhR WT and AhR KO BMDM (Fig. 2C, left). These data indicated that AhR deficiency markedly increased IL-1β accumulation due to its enhanced secretion rather than its increased synthesis.

Expression of AhR-dependent genes in macrophages.

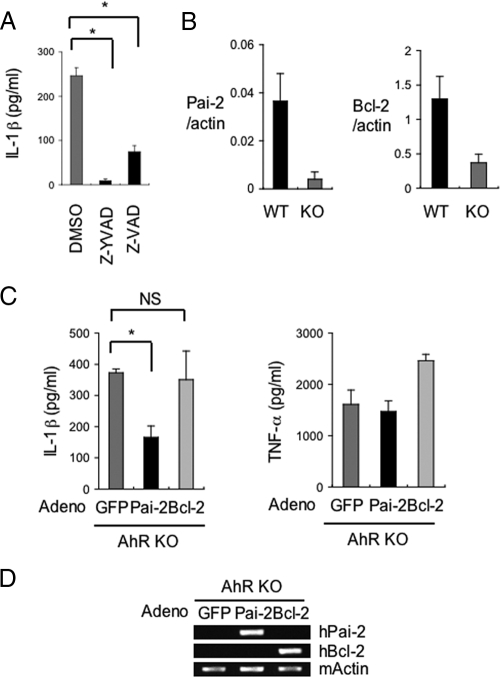

We next performed microarray analysis of AhR WT and AhR KO mouse macrophages to comprehensively investigate the AhR-dependent changes in gene expression that were related to IL-1β secretion (Table 1). Among the genes whose expression was reduced in AhR KO macrophages, we noted the markedly reduced levels of expression of the Pai-2 and Bcl-2 genes. These genes were significant because they had been reported to negatively regulate IL-1β secretion by inhibiting the activity of caspase-1 (5, 10). Consistent with the notion that the enhanced secretion of IL-1β is due to the activation of caspase-1, treatment with the caspase inhibitors Z-YVAD-FMK and Z-VAD-FMK markedly reduced the secretion of IL-1β in AhR KO BMDM (Fig. 3A). To confirm their reduced expression in AhR KO BMDM, Pai-2 and Bcl-2 mRNA expression levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR in AhR WT and AhR KO BMDM (Fig. 3B). Figure 3B shows that Pai-2 and Bcl-2 mRNA expression levels were clearly reduced in AhR KO BMDM. To investigate whether the increased IL-1β secretion in AhR KO BMDM was due to their reduced Pai-2 and Bcl-2 expression, the expression of these proteins was supplemented in AhR KO BMDM by infection with adenoviral vectors expressing hPai-2 and hBcl-2 (Fig. 3D). The efficiency of the adenoviral gene transfer, as monitored by the expression of GFP, was estimated to be >90% (data not shown). Compared with control adenoviral expression of GFP, transfer of the hPai-2 gene into AhR KO BMDM significantly inhibited LPS-induced secretion of IL-1β (Fig. 3C), but almost no effect was observed with Bcl-2 expression. Bcl-2 has been reported to suppress IL-1β secretion that is specifically processed through the NALP1 complex and regulated by muramyl dipeptide, which is usually a contaminant in commercial LPS (5). These results suggested that the enhanced IL-1β secretion in response to LPS was due not to processing through the NALP1 complex (5) but to processing through the NALP3 complex, an inflammasome-containing caspase-1 regulated by LPS (16), and that decreased Pai-2 expression is at least one of the causes for the increased IL-1β secretion by AhR KO BMDM after LPS treatment.

TABLE 1.

Decreased gene expression in AhR KO PEMs revealed by cDNA microarray analysis

| Fold change | Value for |

Gene name | Gene product | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT PEMs | KO PEMs | |||

| 14.0 | 0.561 | 0.040 | Gsta3 | Glutathione S-transferase alpha 3 |

| 10.2 | 7.826 | 0.767 | Pai-2 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 |

| 5.5 | 9.354 | 1.700 | Cyp1b1 | Cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily b, polypeptide 1 |

| 4.6 | 0.206 | 0.045 | Nkrf | NF-κB repressing factor |

| 3.6 | 1.922 | 0.541 | Cxcl5 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 |

| 3.1 | 13.670 | 4.444 | Mmp8 | Matrix metallopeptidase 8 |

| 2.9 | 1.406 | 0.489 | Cxcl13 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 13 |

| 2.6 | 2.111 | 0.800 | Lrrc27 | Leucine-rich repeat-containing 27 |

| 2.5 | 3.466434 | 1.394728 | Ctgf | Connective tissue growth factor |

| 2.2 | 3.849141 | 1.722473 | Mcoln3 | Mucolipin 3 |

| 2.2 | 1.204793 | 0.550093 | Nqo1 | NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1 |

| 2.0 | 6.96623 | 3.453017 | ler3 | Immediate early response 3 |

| 2.0 | 0.596479 | 0.294062 | Bcl2 | B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 |

FIG. 3.

Decreased Pai-2 expression is one of the causes of the increased IL-1β secretion by LPS-treated AhR KO BMDM. (A) Inhibition of IL-1β oversecretion from AhR KO BMDM by treatment with caspase-1 inhibitor (Z-YVAD-FMK) or caspase inhibitor (Z-VAD-FMK). (B) Relative expression levels of Pai-2 and Bcl-2 mRNA in AhR WT and AhR KO BMDM. (C) The effect of hPai-2 and hBcl-2 reconstitution on the LPS-induced secretion of IL-1β and TNF-α by AhR KO BMDM. BMDM from AhR KO mice were infected with the individual adenovirus (adeno) vectors and then washed and incubated for 24 h. IL-1β and TNF-α levels in the supernatants 8 h after LPS stimulation (n = 3) were determined by ELISA. (D) Assessment of hPai-2 and hBcl-2 mRNA expression in adenovirus (adeno) vector-infected BMDM by conventional RT-PCR. Error bars show standard deviations. *, P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

Arnt is not required for enhancement of LPS-induced Pai-2 expression by AhR.

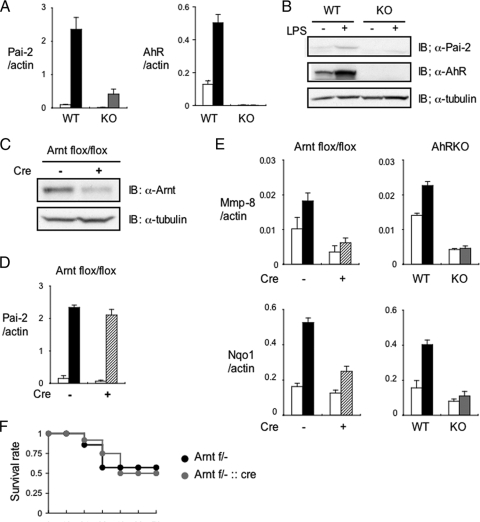

It has been reported that LPS stimulation induces Pai-2 expression (21, 26). Figure 4A and B show that the induction of both Pai-2 mRNA and protein expression was remarkably reduced in AhR KO macrophages compared with the levels in AhR WT macrophages. Interestingly, AhR mRNA and protein expression levels were also induced by LPS stimulation (Fig. 4A and B). In response to various PAHs, AhR is known to act, in most cases, as a transcriptional activator, in heterodimer formation with Arnt. Although the mouse Pai-2 promoter does not have any obvious XRE sequences (GCGTG) in its regions 5 kb upstream and downstream of the transcription start site, we were interested in determining whether Arnt was also involved in the inducible expression of Pai-2 by LPS. Other AhR target genes identified by the microarray analysis, e.g., the matrix metalloproteinase (Mmp-8) gene and the NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (Nqo1) gene (Table 1), have characteristic XRE sequences in their promoter regions and were also induced by 3MC. As expected, the induction of their expression was greatly reduced in Arnt KO and Arnt small interfering RNA (siRNA)-treated macrophages (Fig. 4E; also see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In stark contrast, the expression of Pai-2 was not much different in Arnt KO and Arnt siRNA-treated macrophages, indicating that Arnt is not involved in regulating Pai-2 gene expression (Fig. 4D; also see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and that AhR regulates Pai-2 gene expression by a noncanonical mechanism. Consistent with these observations, macrophage-specific conditional deletion of Arnt did not significantly alter the sensitivity to LPS treatment (Fig. 4F).

FIG. 4.

Arnt is not required for LPS-induced enhancement of Pai-2 expression. (A) Relative Pai-2 and AhR mRNA expression levels in AhR WT and AhR KO PEMs 4 h after treatment with (black or gray bars) or without (white bars) LPS (10 ng/ml). (B) Immunoblot analysis of Pai-2 and AhR expression in AhR WT and KO PEMs after a 16-h incubation with LPS (10 ng/ml). (C) Immunoblot analysis of Arnt in Arntflox/flox and Arntflox/flox::LysM Cre PEMs. (D) Relative Pai-2 mRNA expression levels 4 h after incubation of Arntflox/flox (black bar) and Arntflox/flox::LysM Cre (hatched bar) PEMs with LPS (10 ng/ml). (E) Left, relative expression levels of Mmp-8 and Nqo1 mRNA in Arntflox/flox (black bar) and Arntflox/flox::LysM Cre (hatched bar) PEMs treated with DMSO (white bars) or 3MC (black or hatched bar) (1 μM). Right, relative expression levels of Mmp-8 and Nqo1 mRNA in AhR WT (black bar) and AhR KO (gray bar) PEMs treated with DMSO (white bars) or 3MC (black or gray bar) (1 μM). (F) Survival of Arntflox/− (Arnt f/−; n = 7) and Arntflox/−::LysM Cre (Arnt f/−::cre; n = 12) mice after LPS challenge (25 mg/ml). Error bars show standard deviations. IB, immunoblot; +, present; −, absent; α, anti.

DNA elements regulating Pai-2 gene expression.

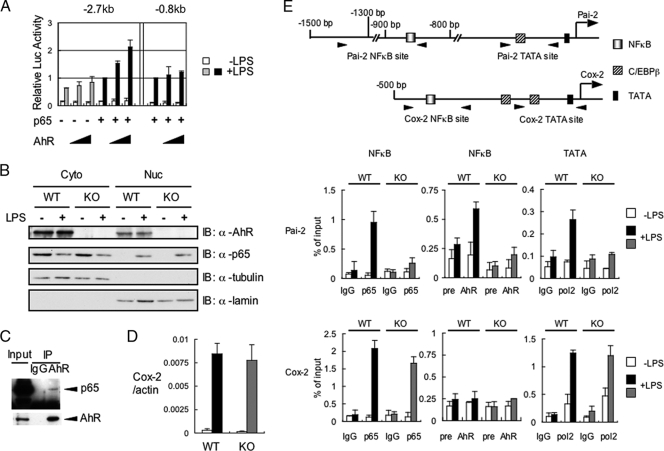

We were interested in further investigating how AhR regulates Pai-2 gene expression in macrophages. It has been previously reported that LPS-induced Pai-2 expression requires NF-κB activation (21) and that AhR and p65 physically interact with each other (31). With those results in mind, we constructed a reporter gene by fusing a 2.7-kb sequence upstream of the mouse Pai-2 transcription start site to the luciferase gene (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). This 2.7-kb Pai-2 reporter gene contained a previously reported NF-κB site (21). When the AhR expression vector alone was transfected into RAW 264.7 cells, it did not enhance LPS-induced reporter gene expression. In contrast, cotransfection of both AhR and p65 did (Fig. 5A). To identify the sequence responsible for enhancing the LPS-induced activation of the reporter gene, we constructed an 0.8-kb Pai-2 reporter gene by deleting the sequence from −2.7 to −0.8 kb, which contained the previously reported NF-κB site (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). With this 0.8-kb Pai-2 construct, the addition of AhR and p65 no longer enhanced the activity in response to LPS treatment (Fig. 5A), indicating that the sequence between −0.8 and −2.7 kb, containing an NF-κB site, is responsible for enhancing Pai-2 gene activation in response to AhR and NF-κB. Further downstream, we noticed the presence of a putative C/EBPβ binding sequence (around 250 base pairs upstream of the transcription initiation site), which has been reported to be responsible for LPS-induced activation of the gene (4). Deletion or point mutation of this sequence was found to abrogate the ability of LPS to induce this gene, indicating that this C/EBPβ binding site functions as an enhancer sequence in the LPS response (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 5.

Recruitment of transcription factors necessary for LPS-induced Pai-2 expression. (A) LPS-induced luciferase expression from the Pai-2 (−2.7 kb) and Pai-2 (−0.8 kb) reporter genes. RAW 264.7 cells were transfected with each reporter gene, with and without pcDNA3-AhR (0 ng, 50 ng, 100 ng) and/or pcDNA3-p65 (1 ng). Values represent the means, normalized to Renilla luciferase activity (used as an internal control), ± standard deviations of the results of three independent experiments. The activities shown by the fourth and seventh pairs of bars were used as standards for normalizing the relative activities of the other conditions. (B) AhR WT and AhR KO PEMs were left untreated or were treated with LPS for 1 h. Cytoplasmic (Cyto) and nuclear (Nuc) extracts were immunoblotted with antibodies against AhR, p65, tubulin, and lamin. (C) Co-IP of AhR and p65. Whole-cell extracts from AhR WT PEMs were coimmunoprecipitated with anti-AhR antibody. Co-IPs and Western blotting were performed as described in Materials and Methods. (D) Relative expression levels of Cox-2 mRNA in AhR WT and AhR KO PEMs after 4 h of treatment with or without LPS (10 ng/ml). Bars are as labeled in panel A. Error bars show standard deviations. (E) Top, transcription factor binding sites in the Pai-2 and Cox-2 genes. Bottom, results of ChIP analyses of the Pai-2 and Cox-2 promoters. ChIP analyses were performed using antibodies to p65, AhR, and PolII in LPS-induced AhR WT and AhR KO PEMs. ChIP analyses and real-time PCRs were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars show standard deviations. +, present; −, absent; α, anti; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

Recruitment of transcription factors necessary for LPS-induced Pai-2 expression.

When macrophages were treated with LPS, p65 translocated from the cytoplasm into the nucleus independently of AhR (Fig. 5B), as reported previously. However, without AhR, ChIP revealed that p65 was not recruited to the enhancer sequence in the Pai-2 gene, which contains an NF-κB site (Fig. 5E). In WT macrophages, nuclear-translocated p65 was only recruited to the enhancer sequence of the Pai-2 gene together with AhR. PolII was concomitantly recruited to the TATA sequence of the Pai-2 gene in AhR WT but not AhR KO macrophages. Surprisingly, we observed that LPS induced AhR binding to the Pai-2 NF-κB site, as shown by ChIP using an anti-AhR antiserum. Co-IP assays revealed that AhR and p65 interacted in macrophages (Fig. 5C), consistent with a previous report (31). On the other hand, expression of the Cox-2 gene is known to be activated by LPS through recruitment of p65 to its NF-κB binding site, and this occurs independent of AhR (Fig. 5D), with concomitant binding of PolII to the transcription initiation site (TATA) of the Cox-2 gene (Fig. 5E). Arnt was not recruited to the Pai-2 promoter by ChIP assay (data not shown), consistent with normal Pai-2 expression in the macrophages from Arntflox/−::LysM Cre mice (Fig. 4D).

As shown in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material, the CCAAT box sequence in the Pai-2 gene was recognized by C/EBPβ in an LPS-dependent manner in both AhR WT and KO macrophages. This binding of C/EBPβ to the Pai-2 promoter might explain the weak LPS-induced activation of Pai-2 gene expression in AhR KO macrophages (Fig. 4A; also see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), as described in the previous section.

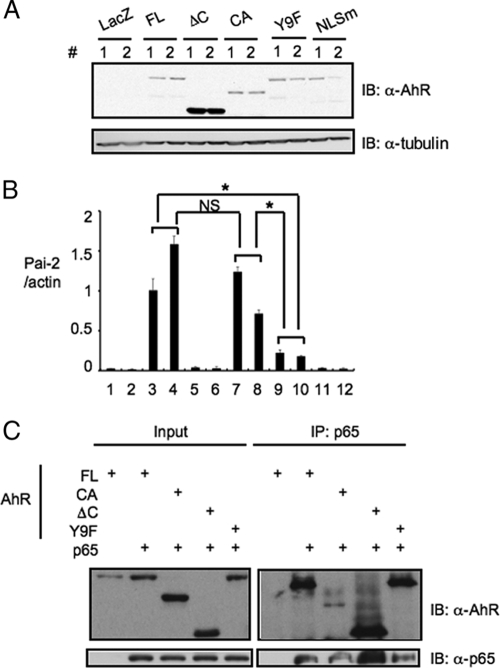

The requirement of the functional domains of AhR for AhR-dependent Pai-2 expression.

To determine the functional domains of AhR for AhR-dependent Pai-2 expression, we investigated the Pai-2 expression in ANA-1 cells, which were transfected with various AhR mutants (Fig. 6). Compared with the levels in ANA-1 cells transfected with full-length AhR, we observed much lower levels of expression of Pai-2 in the ANA-1 cells transfected with AhR NLSm (a mutant located predominantly in the cytoplasm) (Fig. 6B, bars 3, 4, 11, and 12). On the other hand, transfection with AhR CA (a constitutively active mutant located predominantly in the nucleus) gave a result for Pai-2 expression comparable to that of the transfection with full-length AhR (Fig. 6B, bars 3, 4, 7, and 8). These results indicated that nuclear AhR functions in AhR-dependent Pai-2 expression. The fractionation of AhR indicated that a small but significant amount of AhR existed in the nucleus without treatment with ligands such as 3MC, in contrast with the large amount in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5B), consistent with the previous report that AhR has functional nuclear localization signal and nuclear export signal sequences and shuttles between the cytoplasm and nucleus. It is reported that when nuclear export is inhibited by trichomycin B or phosphorylation at S68, AhR accumulates in the nucleus (12). Therefore, it could be considered that in macrophages, AhR is involved in Pai-2 expression induced by LPS treatment in the absence of typical AhR ligands (Fig. 4A). The mechanism of AhR's involvement in Pai-2 expression induced by LPS will be investigated in detail. To further address the question of the requirement for the AhR domain in Pai-2 expression, we generated ANA-1 cells stably transfected with AhR ΔC (an activation domain-deficient mutant) and AhR Y9F (the mutant with attenuated DNA binding) (18). Compared with the expression in stable ANA-1 cells transfected with full-length AhR, neither of the cell lines transfected with AhR ΔC or AhR Y9F significantly expressed Pai-2 (Fig. 6B, bars 3 to 6, 9, and 10). These results indicate that both the activation and DNA binding domains of AhR were required for AhR-dependent Pai-2 expression. Co-IP analysis using these AhR mutants showed that the N-terminal region of AhR (AhR ΔC mutant) interacted with p65 (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Nuclear localization, activation, and DNA binding domains of AhR are required for AhR-dependent Pai-2 expression. (A) Immunoblot analysis of full-length AhR or mutants in LacZ or AhR transformant ANA-1 cells. Paired lanes labeled 1 and 2 show results from experiments using two independent transformants. (B) Relative expression levels of Pai-2 mRNA in ANA-1 cells transfected with LacZ or full-length AhR or mutants. Bars show quantification of the results in the 12 lanes in panel A; error bars show standard deviations. *, P < 0.001; NS, not significant. (C) Interaction of p65 and AhR mutants. Co-IP of p65 and full-length AhR or mutants expressed in 293T cells, using anti-p65 antibody. AhR FL (full-length) comprises amino acids 1 to 805, AhR ΔC comprises amino acids 1 to 544, and AhR CA comprises amino acids 1 to 276 and 419 to 805; in AhR Y9F, Y9 was mutated to F; and in AhR NLSm 37R, 38H, and 39R were mutated to A, G, and S, respectively. IB, immunoblot; α, anti; +, present.

DISCUSSION

AhR was originally found as a transcription factor that was involved in the induction of xenobiotic-metabolizing CYP1A1 by TCDD and other PAHs and has been found to act as a multifunctional regulatory factor in areas ranging from drug metabolism to innate immunity, providing protection against invading xenobiotics. Close investigation of the phenotypes of AhR KO mice revealed that they seem to suffer from morbidity from impaired immunity and easily succumb to bacterial infection. We examined the susceptibility of AhR KO mice to LPS-induced septic shock and found that they were hypersensitive to LPS treatment and had increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-18, and IFN-γ (Fig. 1A and B). It has been reported that in endotoxic shock, IL-1β and TNF-α are rapidly released and trigger a secondary inflammatory cascade that is dependent on the transcription factor NF-κB (10). Mice with a macrophage-specific conditional deletion of AhR (AhRflox/−::LysM Cre) were more susceptible to LPS-induced septic shock than AhRflox/− mice, indicating that the dysfunction of macrophages due to AhR deficiency is one of the major causes of the enhanced susceptibility of AhR KO mice to LPS-induced septic shock (Fig. 2A). Consistent with these observations, isolated AhR KO BMDM secreted much larger amounts of IL-1β and had a slight increase in TNF-α in response to LPS (Fig. 2B). Since IL-1β mRNA levels were not altered between AhR KO and AhR WT BMDM (Fig. 2C), the increased IL-1β secretion is probably not due to the enhanced synthesis but, rather, is likely due to enhanced processing of IL-1β. (16).

We thought that this IL-1β oversecretion by AhR-deficient macrophages might provide clues as to how AhR functions as a physiological immunosuppressor. Microarray analyses to comprehensively investigate the AhR-dependent changes in gene expression that were responsible for increased IL-1β secretion revealed that the levels of expression of Pai-2 and Bcl-2 mRNA were markedly reduced in AhR KO BMDM, which was confirmed by real-time PCR (Fig. 3B). Reconstitution experiments with adenoviruses showed that only Pai-2 expression could significantly suppress IL-1β oversecretion in AhR KO macrophages, while no suppressive effect was observed with Bcl-2 expression (Fig. 3C). It has been reported that there are several pathways for processing IL-1β that lead to its secretion (16). These results indicate that Pai-2 and Bcl-2 are differentially involved in these pathways. Recently, in experiments using ΔIKKβ myeloid mice, Pai-2 has been reported to suppress IL-1β secretion, acting downstream of NF-κB (10). The IL-1β processing that is regulated by the inflammasome involves caspase-1 (16). Consistent with these observations, treatment with caspase inhibitors, Z-YVAD-FMK and Z-VAD-FMK markedly reduced the secretion of IL-1β in AhR KO BMDM (Fig. 3A). It has also been reported that IL-18 processing is regulated by the same mechanism as IL-1β, which is consistent with the marked increase in plasma IL-18 levels (P < 0.001) observed in LPS-injected AhR KO mice (Fig. 1B). Stimulation of the inflammasome involving caspase-1 usually requires secondary signals, such as high ATP concentrations. Interestingly, however, the IL-1β oversecretion resulting from AhR deficiency did not seem to require any other stimulation besides LPS, which is in accordance with the report on the IKKβ Δmyeloid mice (10). Further investigation will be required to address the molecular details of Pai-2-regulated IL-1β secretion.

Although it has been reported that Pai-2 mRNA was induced by a typical AhR ligand, TCDD (27), we did not find any obvious XRE sequences (GCGTG) in the 5-kb regions upstream or downstream of the transcription start site of the mouse Pai-2 promoter. However, these promoter regions rendered a reporter gene responsive to LPS (Fig. 5A and E). This sequence search suggested that AhR might not regulate Pai-2 gene expression in the canonical way (i.e., heterodimerized with Arnt) and led us to investigate whether Arnt was involved in LPS-induced Pai-2 regulation. In experiments with Arnt-deficient and Arnt siRNA-expressing macrophages, we demonstrated that AhR enhanced Pai-2 expression in an Arnt-independent manner (Fig. 4D; also see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Arnt2 is considered to be another possible alternative (11), but we have previously shown that AhR interacts predominantly with Arnt but not with Arnt2 (27). Therefore, it is highly likely that AhR enhances Pai-2 expression independently of Arnt family proteins (11). It was previously reported that LPS induced Pai-2 expression through activation of NF-κB (21) and that AhR physically interacted with p65 (31) to activate or inhibit gene expression in a context-dependent manner (31). In our reporter gene assay using RAW 264.7 cells, the Pai-2 reporter gene required both NF-κB and AhR for a high level of expression in response to LPS treatment (Fig. 5A). In AhR KO macrophages, LPS treatment induced nuclear translocation of p65 (Fig. 5B), but it was not recruited to the NF-κB-binding site of the Pai-2 gene, which confers LPS inducibility (Fig. 5E), suggesting that AhR is required for recruitment of p65 to this site, which may be a crossing point between AhR and NF-κB signaling pathways. In WT macrophages, AhR and p65 were recruited to the same DNA sequence by the LPS treatment (Fig. 5E), and they interacted directly (Fig. 5C and 6C), leading to the recruitment of PolII to the TATA sequence of the transcription initiation site. In contrast, p65 was recruited to the Cox-2 promoter in response to LPS treatment in AhR KO macrophages. The detailed molecular basis for how p65 binds differentially to the Pai-2 and Cox-2 genes remains to be investigated.

It was also reported that AhR interacts with RelB on chemokine promoters, such as IL-8, in response to TCDD treatment, enhancing their expression (33). Although an AhR-RelB binding DNA sequence, designated RelBAhRE (GGGTGCAT), was found near the NF-κB site in the Pai-2 promoter, the expression of the Pai-2 (−2.7 kb) Luc reporter gene was not enhanced by RelB and AhR coexpression (data not shown), suggesting that RelB may not function as a partner for AhR in inducing Pai-2 expression. Since the AhR DNA binding activity was suggested by the results of the experiment using the AhR Y9F mutant to be required for AhR-dependent Pai-2 expression (Fig. 6B, bars 3, 4, 9, and 10), the possibility could be raised that an AhR and p65 heterodimer might work as a transcription factor by binding the RelBAhRE sequence. However, the experiments using the reporter gene containing a tandem arrangement of four RelBAhRE sequences did not showed enhanced expression of the reporter gene expression with coexpression of AhR and p65. It remains to be investigated in detail how AhR and p65 activate the Pai-2 promoter. AhR has been reported to have the nuclear localization signal and nuclear export signal sequences and to shuttle between nucleus and cytoplasm. Inhibition of nuclear export of AhR by trichomycin B or phosphorylation reportedly leads to the accumulation of AhR in the nucleus (12). Consistent with these findings, a small part of AhR was observed in the nuclei of macrophages under normal conditions. Upon treatment with LPS, nuclear AhR should accumulate due to phosphorylation downstream of the LPS signaling pathway or p65, reported to be translocated into the nucleus (21), should be recruited to the Pai-2 promoter with the nuclear AhR.

Recently, there have been growing lines of evidence that AhR plays a crucial role in differentiation of the Th cell subsets Th1, Treg, and Th17 from naive CD4 T cells. It was reported that differentiation of these regulatory T cells from AhR KO naive T cells was significantly impaired under their respective polarizing conditions. AhR is reported to be highly induced under these conditions (14, 20, 23, 32), and AhR ligands further stimulated the tendency to their respective differentiations by molecular mechanisms that are largely unknown. In macrophages, AhR was also induced by LPS treatment (Fig. 4A and B) and negatively regulated the secretion of certain inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-18, most likely through the expression of Pai-2. Since AhR is a ligand-activated transcription factor and is known to be ubiquitously expressed in immune cells (13), this raises the possibility that an appropriate AhR ligand may be useful for treating patients with inflammatory disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Varesio for kindly providing ANA-1 cells and Y. Watanabe and S. Ooba for mouse maintenance. We also thank Y. Nemoto for clerical work.

This work was funded in part by Solution Oriented Research for Science and Technology from Japan Science and Technology, Japan Science and Technology Agency, Kawaguchi, Japan, and by a grant for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 12 October 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott, B., J. Schmid, J. Pitt, A. Buckalew, C. Wood, G. Held, and J. Diliberto. 1999. Adverse reproductive outcomes in the transgenic Ah receptor-deficient mouse. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 155:62-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba, T., J. Mimura, N. Nakamura, N. Harada, M. Yamamoto, K. Morohashi, and Y. Fujii-Kuriyama. 2005. Intrinsic function of the aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor as a key factor in female reproduction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:10040-10051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasi, E., D. Radzioch, S. Durum, and L. Varesio. 1987. A murine macrophage cell line, immortalized by v-raf and v-myc oncogenes, exhibits normal macrophage functions. Eur. J. Immunol. 17:1491-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley, M., L. Zhou, and S. Smale. 2003. C/EBPbeta regulation in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:4841-4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruey, J., N. Bruey-Sedano, F. Luciano, D. Zhai, R. Balpai, C. Xu, C. Kress, B. Bailly-Maitre, X. Li, A. Osterman, S. Matsuzawa, A. Terskikh, B. Faustin, and J. Reed. 2007. Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL regulate proinflammatory caspase-1 activation by interaction with NALP1. Cell 129:45-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez-Salguero, P., D. Hilbert, S. Rudikoff, J. Ward, and F. Gonzalez. 1996. Aryl-hydrocarbon receptor-deficient mice are resistant to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 140:173-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez-Salguero, P., T. Pineau, D. Hilbert, T. McPhail, S. Lee, S. Kimura, D. Nebert, S. Rudikoff, J. Ward, and F. Gonzalez. 1995. Immune system impairment and hepatic fibrosis in mice lacking the dioxin-binding Ah receptor. Science 268:722-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez-Salguero, P., J. Ward, J. Sundberg, and F. Gonzalez. 1997. Lesions of aryl-hydrocarbon receptor-deficient mice. Vet. Pathol. 34:605-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujii-Kuriyama, Y., and J. Mimura. 2005. Molecular mechanisms of AhR functions in the regulation of cytochrome P450 genes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338:311-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greten, F., M. Arkan, J. Bollrath, L. Hsu, J. Goode, C. Miething, S. Göktuna, M. Neuenhahn, J. Fierer, S. Paxian, N. Van Rooijen, Y. Xu, T. O'Cain, B. Jaffee, D. Busch, J. Duyster, R. Schmid, L. Eckmann, and M. Karin. 2007. NF-kappaB is a negative regulator of IL-1beta secretion as revealed by genetic and pharmacological inhibition of IKKbeta. Cell 130:918-931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirose, K., M. Morita, M. Ema, J. Mimura, H. Hamada, H. Fujii, Y. Saijo, O. Gotoh, K. Sogawa, and Y. Fujii-Kuriyama. 1996. cDNA cloning and tissue-specific expression of a novel basic helix-loop-helix/PAS factor (Arnt2) with close sequence similarity to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt). Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1706-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikuta, T., Y. Kobayashi, and K. Kawajiri. 2004. Cell density regulates intracellular localization of aryl hydrocarbon receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 279:19209-19216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerkvliet, N. 2009. AHR-mediated immunomodulation: the role of altered gene transcription. Biochem. Pharmacol. 77:746-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura, A., T. Naka, K. Nohara, Y. Fujii-Kuriyama, and T. Kishimoto. 2008. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor regulates Stat1 activation and participates in the development of Th17 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:9721-9726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lund, A., M. Goens, B. Nuñez, and M. Walker. 2006. Characterizing the role of endothelin-1 in the progression of cardiac hypertrophy in aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) null mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 212:127-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinon, F., and J. Tschopp. 2007. Inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes: master switches of inflammation. Cell Death Differ. 14:10-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mimura, J., K. Yamashita, K. Nakamura, M. Morita, T. Takagi, K. Nakao, M. Ema, K. Sogawa, M. Yasuda, M. Katsuki, and Y. Fujii-Kuriyama. 1997. Loss of teratogenic response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in mice lacking the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Genes Cells 2:645-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minsavage, G. D., S. Park, and T. A. Gasiewicz. 2004. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) tyrosine 9, a residue that is essential for AhR DNA binding activity, is not a phosphoresidue but augments AhR phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 279:20582-20593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muruve, D., V. Pétrilli, A. Zaiss, L. White, S. Clark, P. Ross, R. Parks, and J. Tschopp. 2008. The inflammasome recognizes cytosolic microbial and host DNA and triggers an innate immune response. Nature 452:103-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Negishi, T., Y. Kato, O. Ooneda, J. Mimura, T. Takada, H. Mochizuki, M. Yamamoto, Y. Fujii-Kuriyama, and S. Furusako. 2005. Effects of aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling on the modulation of TH1/TH2 balance. J. Immunol. 175:7348-7356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park, J., F. Greten, A. Wong, R. Westrick, J. Arthur, K. Otsu, A. Hoffmann, M. Montminy, and M. Karin. 2005. Signaling pathways and genes that inhibit pathogen-induced macrophage apoptosis—CREB and NF-kappaB as key regulators. Immunity 23:319-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrulis, J., and G. Perdew. 2002. The role of chaperone proteins in the aryl hydrocarbon receptor core complex. Chem. Biol. Interact. 141:25-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quintana, F., A. Basso, A. Iglesias, T. Korn, M. Farez, E. Bettelli, M. Caccamo, M. Oukka, and H. Weiner. 2008. Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 453:65-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt, J., G. Su, J. Reddy, M. Simon, and C. Bradfield. 1996. Characterization of a murine Ahr null allele: involvement of the Ah receptor in hepatic growth and development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:6731-6736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schreiber, E., P. Matthias, M. Müller, and W. Schaffner. 1989. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts,’ prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz, B., and J. Bradshaw. 1992. Regulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor mRNA levels in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytes. Correlation with production of the protein. J. Biol. Chem. 267:7089-7094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekine, H., J. Mimura, M. Yamamoto, and Y. Fujii-Kuriyama. 2006. Unique and overlapping transcriptional roles of arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt) and Arnt2 in xenobiotic and hypoxic responses. J. Biol. Chem. 281:37507-37516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sogawa, K., R. Nakano, A. Kobayashi, Y. Kikuchi, N. Ohe, N. Matsushita, and Y. Fujii-Kuriyama. 1995. Possible function of Ah receptor nuclear translocator (Arnt) homodimer in transcriptional regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1936-1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reference deleted.

- 30.Takagi, S., H. Tojo, S. Tomita, S. Sano, S. Itami, M. Hara, S. Inoue, K. Horie, G. Kondoh, K. Hosokawa, F. Gonzalez, and J. Takeda. 2003. Alteration of the 4-sphingenine scaffolds of ceramides in keratinocyte-specific Arnt-deficient mice affects skin barrier function. J. Clin. Investig. 112:1372-1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tian, Y., S. Ke, M. Denison, A. Rabson, and M. Gallo. 1999. Ah receptor and NF-kappaB interactions, a potential mechanism for dioxin toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 274:510-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veldhoen, M., K. Hirota, A. Westendorf, J. Buer, L. Dumoutier, J. Renauld, and B. Stockinger. 2008. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature 453:106-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogel, C., E. Sciullo, W. Li, P. Wong, G. Lazennec, and F. Matsumura. 2007. RelB, a new partner of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated transcription. Mol. Endocrinol. 21:2941-2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.