Abstract

We report a link between Cullin5 (Cul5) E3 ubiquitin ligase and the heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) chaperone complex. Hsp90 participates in the folding of its client proteins into their functional conformation. Many Hsp90 clients have been reported to be aberrantly expressed in a number of cancers. We demonstrate Cul5 interaction with members of the Hsp90 chaperone complex as well as the Hsp90 client, ErbB2. We observed recruitment of Cul5 to the site of ErbB2 at the plasma membrane and subsequent induction of polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. We also demonstrate Cul5 involvement in regulation of another Hsp90 client, Hif-1α. We observed Cul5 degradation of ErbB2 to occur independently of ElonginB-ElonginC function. The involvement of Cul5 in Hsp90 client regulation has implications in the effectiveness of Hsp90 targeted chemotherapy, which is currently undergoing clinical trials. The link between Cul5 and Hsp90 client regulation may represent an avenue for cancer drug development.

Keywords: chaperone, erbb2

The regulation of client proteins by heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) plays an important role in critical cellular processes such as cell cycle control and apoptosis. Dysregulation is linked to cancer and neurological diseases (1, 2). Hsp90 is a molecular chaperone responsible for the correct folding of proteins, allowing them to attain their proper functional conformations (3). Many client proteins of Hsp90 are overexpressed oncogenes that are critical for the transformed phenotype observed in tumors (4–6). Clients of Hsp90 are also regulated by the ubiquitin/proteasome system (7). However, the identity of the cellular E3 ubiquitin ligase(s) that regulate(s) Hsp90 client proteins is still elusive.

The Cullin family of RING E3 ubiquitin ligases are modular enzymes that act as a scaffolding to bring a specific substrate within close proximity to the E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, thereby facilitating ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation (8, 9). There are seven known human Cullin proteins, Cul1, 2, 3, 4a, 4b, 5, and 7, with diverse functions from cell cycle regulation, to DNA repair, to regulation of developmental processes. Substrate specificity is determined by the combinatorial nature of E3 ligase assembly. In the case of Cul1, diversity is achieved by the assembly of different F-box substrate receptor proteins with Cul1 through a single Skp1 adaptor protein (10). Each F-box protein determines the specificity of Cul1 substrates. Cul3 is unique in having one protein with two domains, one functioning as an adaptor forming an interface with Cullin, and the other acting as a substrate receptor (9).

Cul2 and 5 are interesting in that they both use ElonginB-C adaptor proteins, through which they bind a SOCS box containing substrate receptor (8). Whether a substrate receptor recruits Cul2 or Cul5 depends on an additional Cullin binding interface. In the case of cellular substrate receptors, Cullin selection is determined by the presence of a VHL or SOCS box motif (11), in the case of HIV and SIV, a zinc-stabilized helix mediates Cul5 selection (12–15).

Here we demonstrate that Cul5 regulates Hsp90 clients. Our results indicate that Cul5 interacts with the Hsp90 chaperone complex and the Hsp90 client ErbB2 and demonstrate that Cul5 is recruited to the site of ErbB2 on the plasma membrane, thereby inducing its polyubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation. Other Hsp90 client proteins, such as HIF1-α, were also regulated by Cul5. We observed Cul5-mediated degradation of ErbB2 to occur in the absence of the traditional Cul5 adaptors ElonginB and ElonginC, suggesting that a component of the Hsp90 chaperone complex may serve this function. This is an example of a link between Hsp90 and the Cullin family of E3 ubiquitin ligases. This is also a report of an ElonginB-ElonginC-independent Cul5 E3 ubiquitin ligase.

Hsp90 is a well-established target for chemotherapy (16). Our data now provide an explanation for the decrease or loss of Cul5 expression that is observed in a number of cancers (17). Our data also suggest that Cul5 levels could potentially influence susceptibility to certain cancers and the effectiveness of anti-cancer treatment with geldanamycin or its derivatives, which are currently in human clinical trials.

Results

Cul5 Interacts with the Hsp90 Chaperone Complex.

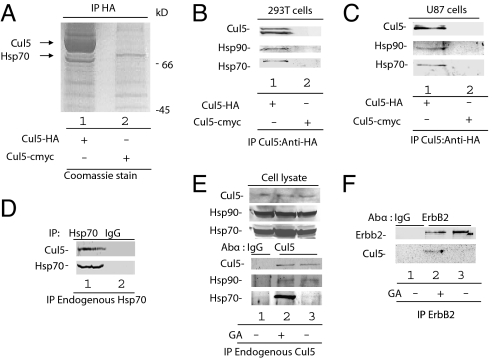

While the cellular function of Cul5 is poorly understood, it is known to be hijacked by the HIV type 1 (HIV-1) Vif protein to suppress the antiviral protein Apobec3G (A3G) (18–20) and by adenovirus E4orf6 and E1B55K to degrade p53, Mre11, and DNA ligase IV (18, 21–25). To identify potential cellular partners of the Cul5 E3 ligase, we immunoprecipitated HA-tagged Cul5 and identified proteins that specifically co-immunoprecipitated with Cul5-HA but not with a cmyc-tagged Cul5 control protein. In repeated experiments, Cul5-HA, but not Cul5-myc, co-precipitated Hsp70, as indicated by mass spectrometry analysis (Fig. 1A). Interaction of Hsp70 with Cul5-HA but not Cul5-myc was confirmed by Western blotting with an anti-Hsp70 antibody (Fig. 1B). We also observed an interaction between Hsp90 and Cul5-HA (Fig. 1B), suggesting that Cul5 may be involved in the regulation of Hsp90 client proteins. Hsp90 is a chaperone that is required for the maturation and function of a number of classes of proteins, namely receptors, kinases, and transcription factors (7, 26). Hsp90 assembles with a number of co-chaperones, including Hsp70, and coordinates the maturation of its client proteins. Client protein maturation occurs via a dynamic ATP-dependent process (7). ATP hydrolysis or inhibition of Hsp90 function through drug treatment results in the reorganization of the chaperone complex and subsequent destabilization of the client protein (7). Interaction of Cul5 with Hsp90 and Hsp70 was also confirmed in U87cells (Fig. 1C). Immunoprecipitation of endogenous Hsp70 also co-precipitated endogenous Cul5 (Fig. 1D). Conversely, immunoprecipitation of endogenous Cul5 also co-precipitated endogenous Hsp90 and Hsp70 (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Cul5 interacts with the Hsp90-Hsp70 chaperone complex. (A) Cul5-HA and Cul5-cmyc were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA-conjugated agarose beads. The eluates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining, and bands were identified by mass spectrometry. (B and C) Cul5-HA and Cul5-cmyc were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA-conjugated agarose beads in (B) 293T and (C) U87 cells. Eluates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with antibodies against HA, Hsp90, and Hsp70. (D) 293T cell lysates were incubated with antibody against Hsp70 or IgG and protein A/G agarose. Protein complexes were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with antibodies against Hsp70 and Cul5. (E) 293T cells were treated with GA or DMSO as indicated. Protein complexes were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against Cul5 and protein A/G agarose. Eluates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with antibodies against Cul5, Hsp90, and Hsp70. (F) 293T cells were transfected with the ErbB2 expression vector and treated with GA or MG132 as indicated. Cell lysates were incubated with antibody against ErbB2 and with protein A/G agarose. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting with antibody against Cul5.

Hsp90 has been shown to be expressed at high levels, along with a number of its client proteins, in a variety of cancers and has therefore become a promising target for intervention (7). Treatment of cells with the benzoquinone ansamycin antibiotic geldanamycin (GA) or its analogs results in the proteasomal degradation of Hsp90 client proteins (16). GA is an ATPase inhibitor that binds the nucleotide-binding pocket with an affinity greater than that of ATP or ADP, shifting the chaperone complex into a conformation that favors client-protein degradation (27). ErbB2 is an Hsp90 client that has been extensively characterized. This receptor tyrosine kinase is overexpressed in approximately 30% of breast cancers and is required for tumor cell proliferation. Treatment of ErbB2- overexpressing cells with GA or its analogs results in rapid proteasomal degradation of ErbB2 (28, 29). While the U-box-containing E3 ligase, CHIP, has been implicated in the degradation of ErbB2 via Hsp/Hsc70, GA-mediated ErbB2 degradation still occurs in CHIP−/− cells, suggesting that an additional E3 ligase is also involved in GA-mediated degradation of ErbB2 (29).

To examine the possibility that Cul5, interacting with the Hsp90 chaperone complex, might serve as an E3 ligase to degrade Hsp90 client proteins, we characterized the interaction of Cul5 with ErbB2. We treated 293T cells transfected with ErbB2 or empty vector with 2 μM GA or control DMSO and 5 μM MG132. Even though equal amounts of ErbB2 were immunoprecipitated, Cul5 interaction was detected only in GA-treated cells (Fig. 1F). These data demonstrate the endogenous interaction of Cul5 with ErbB2 and the Hsp90 chaperone complex, suggesting the involvement of Cul5 in the regulation of Hsp90 client proteins.

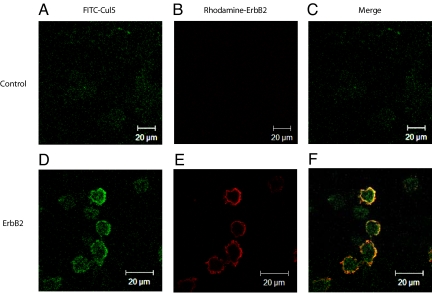

Cul5 Co-Localizes with ErbB2 at the Plasma Membrane.

Since ErbB2 is a receptor tyrosine kinase, we hypothesized that Cul5 might be acting on ErbB2 at the plasma membrane. We therefore transfected 293T cells with either the ErbB2 expression vector or empty vector control for 48 h, then stained for ErbB2 and endogenous Cul5. In the absence of ErbB2, Cul5 was evenly distributed throughout the cell (Fig. 2A). However, in the presence of ErbB2, Cul5 expression appeared to be concentrated at the plasma membrane (Fig. 2 D and E), suggesting that the presence of substrate results in the recruitment of Cul5 to the plasma membrane. This interaction was specific to Cul5, as Cul2 did not co-localize with ErbB2 (Fig. S1). Cul5 appears to co-localize with ErbB2 at the plasma membrane as seen in multiple (2-μm) frames of a zstack (Fig. S2). ErbB2 expression did not affect cell integrity as seen by DAPI and phase contrast (Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Cul5 is recruited to ErbB2 at the plasma membrane. (A–F) 293T cells were transfected with the ErbB2 expression vector (D–F) or empty vector control (A–C). Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were plated on glass coverslips and incubated for 16 h. Cells were fixed, permeablized, and stained with antibodies against endogenous Cul5 and ErbB2. Slides were visualized using a Zeiss Meta 510 confocal microscope and viewed with LSM software. Images are equivalent slices of a z-stack.

Cul5 Is Required for Polyubiquitination and Proteasomal Degradation of ErbB2.

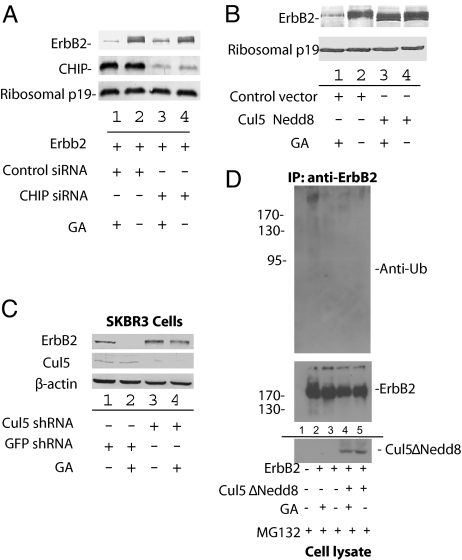

Treatment of ErbB2-expressing cells with GA is known to result in rapid proteasomal degradation of the receptor; however, degradation of ErbB2 still occurs in CHIP−/− cells, suggesting that CHIP is necessary but not sufficient for GA-mediated degradation of ErbB2 (29). In fact, we observed the same phenotype in our system. Transfection with CHIP siRNA resulted in efficient CHIP knockdown; however, treatment with GA still resulted in ErbB2 degradation, supporting the hypothesis that an additional mechanism of GA-induced degradation is at work in this system (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Cul5 is required for polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of ErbB2. (A) CHIP knockdown does not completely stabilize ErbB2. 293T cells were transfected with ErbB2 and either CHIP or control siRNA as indicated. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with GA or DMSO for 16 h. ErbB2 stability was assessed by Western blotting with antibodies against ErbB2, CHIP, and ribosomal p19. (B) ErbB2 degradation is inhibited by the Cul5 dominant-negative mutant. 293T cells were transfected with ErbB2 and Cul5ΔNedd8-cmyc where indicated. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with GA or DMSO for 16 h as indicated. ErbB2 stability was assessed by Western blotting with antibodies against ErbB2, cmyc, and ribosomal p19. (C) Cul5 shRNA inhibits GA-mediated degradation of ErbB2 in SKBR3 cells. SKBR3 cells were infected with lentiviruses containing GFP targeting or Cul5 targeting shRNA. Twenty-four hours post infection, cells were selected with puromycin for 1 week. Cells were treated with GA or equivalent volume of DMSO for 2 h. Cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blot against ErbB2, Cul5, or β-actin where indicated. (D) A Cul5 dominant-negative mutant inhibits ErbB2 polyubiquitination. 293T cells were transfected with ErbB2 and Cul5ΔNedd8-cmyc as indicated. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with 5 μM MG132 and 3 μM GA or DMSO for 4 h as indicated. Cell lysates were incubated with anti-ErbB2 and protein G-conjugated agarose. Immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against ErbB2, myc, and ubiquitin.

To determine whether Cul5 is involved in ErbB2 degradation, we used a dominant-negative mutant, Cul5ΔNedd8, to assess the requirement of Cul5 for ErbB2 degradation (Fig. 3B). In the absence of Cul5ΔNedd8, treatment of ErbB2-transfected 293T cells with GA resulted in ErbB2 degradation (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 1 and 2). However, after the addition of Cul5ΔNedd8, ErbB2 was stabilized even in the presence of GA (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 3 and 1). We have also demonstrated that GA induced degradation of endogenous ErbB2 in the SKBR3 breast cancer cell line was inhibited when Cul5 was efficiently knocked-down. We observed the stabilization of ErbB2 in the SKBR3 cells even in the presence of GA when Cul5 expression was reduced by the shRNA strategy via a lentiviral delivery system (Fig. 3C, lane 4), compared to SKBR3 cells treated with control shRNA targeting GFP (Fig. 3C, lane 2). GA treatment induced polyubiquitination of ErbB2 (Fig. 3D, lane 2), when compared to the control treated cells (lane 3). Cul5ΔNedd8 also inhibited the polyubiquitination of ErbB2 induced by GA (Fig. 3D, compare lanes 2 and 4).

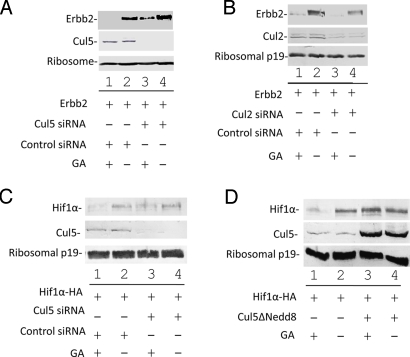

To further examine the role of Cul5 in GA-induced degradation of Hsp90 clients, we used siRNA against the Cul5 coding region to knock down Cul5 expression. Addition of Cul5-specific siRNA (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 and 4), but not control siRNA (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 2), resulted in efficient Cul5 knockdown. GA induced efficient degradation of ErbB2 in control siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 1 and 2), but Cul5 knockdown served to stabilize ErbB2, even in the presence of GA (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 3 and 1). In contrast, knockdown of another Cullin E3 ligase (Cul2) had little effect on GA-induced ErbB2 degradation (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these data suggest that Cul5 is required for GA-induced polyubiquitination and degradation of the Hsp90 client protein ErbB2.

Fig. 4.

Cul5 is required for ErbB2 and Hif-1α degradation. (A and B) Cul5 but not Cul2 is required for GA-mediated ErbB2 degradation. 293T cells were transfected with the ErbB2 expression vector and Cul5, Cul2, or control siRNA as indicated. Forty-eight hours post transfection, the cells were treated with GA or DMSO for 16 h. ErbB2 stability was assessed by Western blotting with antibodies against ErbB2, Cul2, Cul5, and ribosomal p19. (C and D) Cul5 is required for GA-mediated degradation of HIF-1α. 293T cells were cotransfected with HIF-1α-HA expression vector and Cul5 or control siRNA or Cul5ΔNedd8 as indicated. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with GA or DMSO for 16 h. HIF-1α stability was assessed by Western blotting with antibodies against HA, Cul5, and ribosomal p19.

Cul5 Is Required for Degradation of HIF1-α, Another Hsp90 Client.

These findings led us to ask whether Cul5 also participates in the regulation of other Hsp90 client proteins. HIF1-α is a transcription factor that is involved in the regulation of angiogenesis and glucose metabolism (30). Under normoxic conditions, the Cul2-VHL E3 ubiquitin ligase induces the degradation of HIF1-α, but under hypoxic conditions, HIF1-α is stabilized (31). Stabilization of HIF1-α under normoxic conditions has been observed in tumors and VHL-null or mutant cell lines (32). Constitutive expression of HIF1-α is important for vascularization, adaptation to hypoxia, and overall tumor survival. HIF1-α has also been shown to associate with Hsp90 and is sensitive to GA-induced degradation via a mechanism that is independent of oxygen and VHL-Cul2 (7, 33). We examined the potential involvement of Cul5 in GA-mediated, oxygen-independent degradation of HIF1-α. In the presence of control siRNA, treatment with 3 μM GA for 16 h induced HIF1-α degradation (Fig. 4C, lane 1), when compared to control cells that were not subjected to GA (Fig. 4C, lane 2). However, when Cul5 expression was reduced by siRNA against Cul5, GA-induced degradation of HIF1-α was inhibited (Fig. 4C, compare lane 3 to lane 1). We observed a similar effect with the Cul5 dominant negative mutant, Cul5ΔNedd8 (Fig. 4D). Thus, Cul5 apparently also plays a role in the regulation of the Hsp90 client protein HIF1-α, suggesting that Cul5 may regulate multiple Hsp90 client proteins.

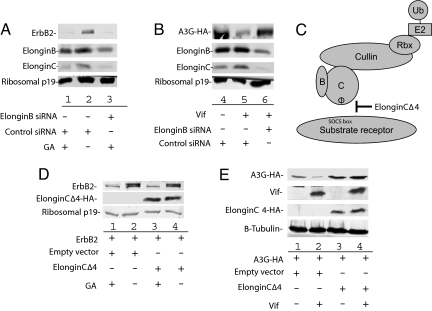

Cul5-Induced Degradation of ErbB2 Occurs Independent of ElonginB and ElonginC.

Cul5 classically requires the adaptor proteins ElonginB and ElonginC to efficiently induce the proteasomal degradation of its substrate. To determine whether ElonginB and ElonginC are required for ErbB2 degradation we used siRNA against ElonginB. Interestingly we observed that knockdown of ElonginB resulted in a significant decrease in ElonginC (Fig. 5 A and B, lanes 3 and 6). This data supports the hypothesis that ElonginB may be involved in stabilization of ElonginC (34). In the presence of siRNA targeted against ElonginB, we did not observe a defect in GA-induced degradation of ErbB2 when compared to nontargeting control siRNA (Fig. 5A, compare lanes 1 and 3). However, we did observe a defect in HIV Vif-mediated degradation of APOBEC3G, suggesting an efficient decrease in ElonginB and ElonginC levels (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 2 and 3). To further evaluate the role of the ElonginB-C adaptor module in Cul5-mediated ErbB2 degradation, we used an ElonginC dominant negative mutant. This mutant can bind Cul5 but can no longer bind the SOCS box in the substrate receptor (Fig. 5C). This has been observed for both HIV-1 Vif and adenovirus E4orf6 (19, 22). Transfection of the ElonginC dominant negative mutant that can no longer interact with the SOCS box had no effect on GA-mediated ErbB2 degradation (Fig. 5D, compare lane 1 with lane 3) but did effect Vif-mediated A3G degradation (Fig. 5E, compare lanes 2 and 4). Since this mutant can no longer interact with the SOCS box, this data suggests that Cul5-mediated degradation of ErbB2 occurs in the absence of a SOCS box containing substrate receptor. In addition, this data suggests Cul5-mediated ErbB2 regulation occurs via an ElonginB-ElonginC-independent, E3 ubiquitin ligase.

Fig. 5.

Cul5-mediated degradation of ErbB2 occurs via an ElonginB-ElonginC-independent mechanism. (A) ElonginB and ElonginC are not required for GA-mediated degradation of ErbB2. 293T cells were cotransfected with ErbB2 expression vector and ElonginB or control siRNA as indicated. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with GA or DMSO for 16 h. ErbB2 stability was assessed by Western blotting with antibodies against ErbB2, ElonginB, ElonginC, and ribosomal p19. (B) ElonginB and ElonginC are required for HIV Vif-mediated degradation of APOBEC3G (A3G). 293T cells were cotransfected with A3G and Vif expression vectors and ElonginB or control siRNA where indicated. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were harvested, and A3G stability was assessed by Western blotting with antibodies against A3G-HA, ElonginB, ElonginC, and ribosomal p19. (C) The ElonginC dominant negative mutant can no longer interact with the SOCS box containing substrate receptor, yet retains interaction with Cul5. (D) ElonginC is not required for GA-mediated degradation of ErbB2. 293T cells were cotransfected with ErbB2 expression vector and ElonginCΔ4 or control empty vector as indicated. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with GA or DMSO for 16 h. ErbB2 stability was assessed by Western blotting with antibodies against ErbB2, HA-tagged ElonginC Δ4, and ribosomal p19. (E) ElonginC is required for Vif-mediated degradation of A3G. 293T cells were cotransfected with A3G and Vif expression vectors and ElonginCΔ4 or control empty vector where indicated. Forty-eight hours post transfection A3G stability was assessed by Western blotting with antibodies against HA-A3G, HIV Vif, HA-tagged ElonginC Δ4, and ribosomal p19.

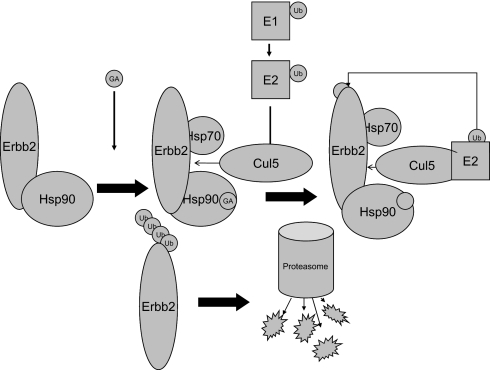

Fig. 6.

A proposed model for Cul5-mediated regulation of Hsp90 client proteins. GA treatment or ATP hydrolysis induces remodeling of the Hsp90 chaperone complex, resulting in recruitment of the Cul5-E3 ubiquitin ligase, followed by polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of ErbB2 or other Hsp90 client proteins.

Discussion

The data we present here suggests that Cul5 is recruited by the Hsp90 complex and serves to regulate Hsp90 client proteins via an ElonginB-ElonginC-independent mechanism. This is an example of a Cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligase being involved in chaperone-mediated protein regulation. We demonstrate Cul5 interaction with Hsp90, Hsp70, and ErbB2. Cul5 specifically co-localizes with ErbB2 at the plasma membrane. Cul5 but not Cul2 is required for proteasomal degradation of ErbB2.

We used lentivirus delivered shRNA against Cul5 to evaluate ErbB2 degradation in SKBR3 breast cancer cells and observed stabilization of ErbB2 in the presence of GA. We also observed increased levels of ErbB2 in DMSO controls, suggesting that Cul5 plays a role in regulation of ErbB2 in both 293T cells ectopically expressing ErbB2 and ErbB2 positive SKBR3 breast cancer cells in the absence of GA. In addition, Cul5 serves to regulate another Hsp90 client Hif1-α, suggesting a role for Cul5 in Hsp90 client regulation. Interestingly, inhibition of the ElonginB-C module via siRNA and dominant negative mutant suggests that Cul5 may be functioning independently of the traditional adaptor proteins. The ElonginC dominant negative mutant can no longer interact with the SOCS box in both HIV Vif and adenovirus E4orf6, suggesting that it can no longer interact with cellular SOCS box containing substrate receptors. This data suggests that a Cul5 E3 ligase is at work here. It is possible that Cul5 may be interacting directly with the Hsp90/Hsp70 chaperone complex, however this has been difficult to determine due to the dynamic nature of the complex.

Hsp90 client proteins play important roles in numerous cellular processes, including signal transduction, gene regulation, cell cycle control, and apoptosis, and elevated expression of some Hsp90 client proteins has been implicated in the maintenance and progression of a number of cancers. Our data raise the possibility that Cul5 dysregulation may play a role in the overexpression of Hsp90 client proteins in certain tumors. Interestingly, Cul5 expression has been shown to be decreased in a number of cancers, suggesting that Cul5 suppression may be beneficial for tumor development or maintenance (35). Our data also suggest that Cul5 can influence the effectiveness of anticancer treatment with GA or its derivatives, and its potential effects should be considered when evaluating the clinical efficacy of these treatments. Thus, the relationship between oncogenesis and Cul5-mediated Hsp90 client regulation may represent an avenue for cancer drug development.

Methods

Cells, Plasmids, Transfection, Reagents, and Antibodies.

293T cells [AIDS Research Reagents Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH), cat no. 3522] were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) with 10% FBS and gentamycin (5 μg/mL; D-10 medium) and passaged upon confluence. Plasmids VR1012, pElonginCΔ4, pCul5-HA, pCul5-myc, and pCul5ΔNedd8 have been described (18, 19). pErbB2 and pCMV-HIF1-α HA were described previously (29, 33). Cells were transfected with Mirus LT1 transfection reagent or Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturers' instructions. The following antibodies used in this study have been described previously (18): anti-HA antibody-agarose conjugate, anti-Elongin B, anti-Elongin C, anti-myc, anti-HA, and anti-human ribosomal P antigens. In addition, the following antibodies were used: anti-ErbB2 (Oncogene), anti-Cul5 (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Cul2 (Zymed), anti-ubiquitin (Covance), anti-Hsp70, and anti-Hsp90 (Stressgen). Geldanamycin (Invivogen) was stored as a 1 mM stock solution in DMSO and used at the indicated concentrations. MG132 (EMD Biosciences) was stored as a 10 mM stock solution in DMSO and used at 5 μM unless otherwise indicated.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting.

Immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously (18). The eluted materials were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting as described (18).

RNA Interference.

siRNA duplexes (Dharmacon) were obtained as a smartpool. Duplexes were transfected according to Dharmacon's instructions using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cells were transfected at 50% confluence and harvested 72 h later.

shRNA Lentivirus Production and Transduction.

shRNA and lentivirus packaging system were obtained from The RNAi Consortium collection available through the Hit center at Johns Hopkins University as a gift from Jef Boeke. Lentivuruses were prepared, and cells were transduced following the protocol generated by the The RNAi Consortium at the Broad Institute. Briefly, 293T cells were plated in a 10-cm plate at a concentration of 1.3–1.5 × 105 cells/mL and transfected at a confluence of approximately 70% with the following plasmids: Cul5 or GFP shRNA pLKO.1 (20 μg), pMD2.G (6 μg), pRSV-Rev (5 μg), and pMDLg/pRRE (10 μg). Eighteen hours post transfection media was changed to high BSA virus production media. Virus was harvested 48 h post transfection. Supernatant was centrifuged to remove any cell debris. SKBR3 cells were infected by adding 10% of the harvested virus plus polybreene at a concentration of 8 μg/mL. Twenty-four hours post infection, media was replaced with fresh media containing puromycin at a concentration of 2 μg/mL. Cells were selected for 1 week before being used for the GA-induced degradation assay.

In Vivo Ubiquitination Assays.

293T cells were cotransfected with ErbB2, Cul5ΔNedd8, and control vector as indicated. At 48 h post transfection, the cells were treated with 5 μM MG132 for 18 h. ErbB2 was immunoprecipitated as described previously. Immunoprecipitates were washed with a 500 μM NaCl wash buffer. Samples were then analyzed by Western blot against ErbB2, ubiquitin, myc, and β-actin.

Immunofluorescent Staining.

293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids as described above. At 24 h post transfection, the cells were trypsinized and plated on glass coverslips at a dilution of one-eighth. Sixteen hours post-plating, cells were fixed in 4% parafomaldehyde, permeablized in 0.3% Triton X-100, then stained with the indicated antibodies. Cells were visualized with a Zeiss Meta 510 confocal microscope and viewed with LSM software or a Nikon 90i and viewed with Velocity software as indicated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank R. Cohen, P.T. Sarkis, J. Romano, L. Tan, and Z. Huh for advice and technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI062644 (to X.F.Y.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. W.J.M. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0810571106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dai C, Whitesell L, Rogers AB, Lindquist S. Heat shock factor 1 is a powerful multifaceted modifier of carcinogenesis. Cell. 2007;130:1005–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solit DB, Rosen N. Hsp90: A novel target for cancer therapy. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:1205–1214. doi: 10.2174/156802606777812068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wegele H, Muller L, Buchner J. Hsp70 and Hsp90—a relay team for protein folding. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;151:1–44. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang H, Burrows F. Targeting multiple signal transduction pathways through inhibition of Hsp90. J Mol Med. 2004;82:488–499. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0549-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waterston RH, et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420:520–562. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Citri A, Kochupurakkal BS, Yarden Y. The achilles heel of ErbB-2/HER2: Regulation by the Hsp90 chaperone machine and potential for pharmacological intervention. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neckers L. Hsp90 inhibitors as novel cancer chemotherapeutic agents. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8(4 Suppl):S55–S61. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02316-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ. Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:9–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pintard L, Willems A, Peter M. Cullin-based ubiquitin ligases: Cul3-BTB complexes join the family. EMBO J. 2004;23:1681–1687. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deshaies RJ. SCF and Cullin/Ring H2-based ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:435–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamura T, et al. VHL-box and SOCS-box domains determine binding specificity for Cul2-Rbx1 and Cul5-Rbx2 modules of ubiquitin ligases. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3055–3065. doi: 10.1101/gad.1252404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehle A, Thomas ER, Rajendran KS, Gabuzda D. A zinc-binding region in Vif binds Cul5 and determines Cullin selection. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17259–17265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602413200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao Z, Ehrlich E, Luo K, Xiong Y, Yu XF. Zinc chelation inhibits HIV Vif activity and liberates antiviral function of the cytidine deaminase APOBEC3G. Faseb J. 2007;21:217–222. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6773com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao Z, et al. Characterization of a novel Cullin5 binding domain in HIV-1 Vif. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao Z, et al. Assembly of HIV-1 Vif-Cul5 E3 ubiquitin ligase through a novel zinc-binding domain-stabilized hydrophobic interface in Vif. Virology. 2006;349:290–299. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blagosklonny MV. Hsp-90-associated oncoproteins: Multiple targets of geldanamycin and its analogs. Leukemia. 2002;16:455–462. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fay MJ, et al. Analysis of CUL-5 expression in breast epithelial cells, breast cancer cell lines, normal tissues and tumor tissues. Mol Cancer. 2003;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu X, et al. Induction of APOBEC3G ubiquitination and degradation by an HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-SCF complex. Science. 2003;302:1056–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.1089591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Y, Xiao Z, Ehrlich ES, Yu X, Yu XF. Selective assembly of HIV-1 Vif-Cul5-ElonginB-ElonginC E3 ubiquitin ligase complex through a novel SOCS box and upstream cysteines. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2867–2872. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehle A, Goncalves J, Santa-Marta M, McPike M, Gabuzda D. Phosphorylation of a novel SOCS-box regulates assembly of the HIV-1 Vif-Cul5 complex that promotes APOBEC3G degradation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2861–2866. doi: 10.1101/gad.1249904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stracker TH, Carson CT, Weitzman MD. Adenovirus oncoproteins inactivate the Mre11-Rad50-NBS1 DNA repair complex. Nature. 2002;418:348–352. doi: 10.1038/nature00863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo K, et al. Adenovirus E4orf6 assembles with Cullin5-ElonginBElonginC E3 ubiquitin ligase through an HIV/SIV Vif-like BC-box to regulate p53. Faseb J. 2007;21:1742–1750. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7241com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harada JN, Shevchenko A, Shevchenko A, Pallas DC, Berk AJ. Analysis of the adenovirus E1B–55K-anchored proteome reveals its link to ubiquitination machinery. J Virol. 2002;76:9194–9206. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9194-9206.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Querido E, et al. Degradation of p53 by adenovirus E4orf6 and E1B55K proteins occurs via a novel mechanism involving a Cullin-containing complex. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3104–3117. doi: 10.1101/gad.926401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker A, Rohleder KJ, Hanakahi LA, Ketner G. Adenovirus E4 34k and E1b 55k oncoproteins target host DNA ligase IV for proteasomal degradation. J Virol. 2007;81:7034–7040. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00029-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young JC, Agashe VR, Siegers K, Hartl FU. Pathways of chaperone mediated protein folding in the cytosol. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:781–791. doi: 10.1038/nrm1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prodromou C, et al. Identification and structural characterization of the ATP/ADP-binding site in the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Cell. 1997;90:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou P, et al. ErbB2 degradation mediated by the co-chaperone protein CHIP. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13829–13837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209640200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu W, et al. Chaperone-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP mediates a degradative pathway for c-ErbB2/Neu. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12847–12852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202365899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Safran M, Kaelin WG., Jr HIF hydroxylation and the mammalian oxygen-sensing pathway. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:779–783. doi: 10.1172/JCI18181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lonergan KM, et al. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible mRNAs by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein requires binding to complexes containing elongins B/C and Cul2. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:732–741. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maxwell PH, et al. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature. 1999;399:271–275. doi: 10.1038/20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Isaacs JS, Jung YJ, Neckers L. Aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator (ARNT) promotes oxygen-independent stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha by modulating an Hsp90-dependent regulatory pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16128–16135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stebbins CE, Kaelin WG, Jr, Pavletich NP. Structure of the VHLElonginC-ElonginB complex: Implications for VHL tumor suppressor function. Science. 1999;284:455–461. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5413.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen XP, et al. Pim serine/threonine kinases regulate the stability of Socs- 1 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2175–2180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042035699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.