Abstract

Single-molecule force spectroscopy methods can be used to generate folding trajectories of biopolymers from arbitrary regions of the folding landscape. We illustrate the complexity of the folding kinetics and generic aspects of the collapse of RNA and proteins upon force quench by using simulations of an RNA hairpin and theory based on the de Gennes model for homopolymer collapse. The folding time, τF, depends asymmetrically on δfS = f S − f m and δf Q = f m − f Q where f S (f Q) is the stretch (quench) force and f m is the transition midforce of the RNA hairpin. In accord with experiments, the relaxation kinetics of the molecular extension, R(t), occurs in three stages: A rapid initial decrease in the extension is followed by a plateau and finally, an abrupt reduction in R(t) occurs as the native state is approached. The duration of the plateau increases as λ = τ Q/τ F decreases (where τ Q is the time in which the force is reduced from f S to f Q). Variations in the mechanisms of force-quench relaxation as λ is altered are reflected in the experimentally measurable time-dependent entropy, which is computed directly from the folding trajectories. An analytical solution of the de Gennes model under tension reproduces the multistage stage kinetics in R(t). The prediction that the initial stages of collapse should also be a generic feature of polymers is validated by simulation of the kinetics of toroid (globule) formation in semiflexible (flexible) homopolymers in poor solvents upon quenching the force from a fully stretched state. Our findings give a unified explanation for multiple disparate experimental observations of protein folding.

The folding of RNA molecules (1) and proteins (2 –5) should be thought of as dynamic changes in the distribution of conformations that result in collapse, the formation of intermediates, and barrier crossings to reach the folded structures. Such a statistical, mechanical perspective of the folding process is finding support in single-molecule measurements that manipulate the structural ensembles by using an external mechanical force (f) (6 –8). The development of the force-clamp methods (6, 8), which allow the application of a constant force to specific locations on a biomolecule, have made it possible to explore in the most straightforward manner the folding of proteins and RNA initiated from regions of the folding landscape that are inaccessible in conventional ensemble experiments. The use of an initial stretching force, f S, which fully unfolds the biomolecule, followed by a subsequent quench to a sufficiently low force, f Q, which populates the native basin of attraction (NBA), holds the promise of unearthing all aspects of the folding reaction, including the dynamics of the collapse process and the extent to which the folding pathways are heterogeneous.

Although there is great heterogeneity in the folding trajectories, Fernandez and Li (6) noted that upon the quench f S → f Q, ubiquitin (Ub) folded in three stages, as reflected in the time-dependent changes in the extension, R(t). Typically, after a very rapid decrease in R(t), there is a long plateau in R(t) that is suggestive of the formation of metastable states, which we term force-induced metastable intermediates (FIMI's). Finally, R(t) decreases sharply in the last stage as the extension corresponding to the native state is reached. Although it is not emphasized, a similar behavior has been observed in the folding of TAR RNA (see figure 3 A of ref. 8) upon abrupt decrease in f, even though the forces used in atomic force microscopy (AFM) experiments on Ub and laser optical tweezers (LOT) experiments on the RNA differ greatly. In contrast, it has been argued that Ub folds in a discrete manner based on refolding initiated by decreasing force slowly by using AFM (7) and not in the way described in ref. 6. The seemingly contradictory conclusions on the refolding of an initially extended Ub require a full theoretical description of the molecular events that ensue when force is decreased from f S.

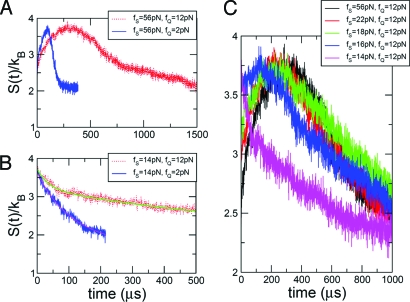

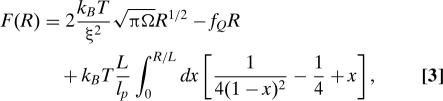

Fig. 3.

The time evolution of the entropy, measured by using Eq. 2. (A) S(t)/k B from f S = 56 pN to f Q = 12 pN (red) and 2 pN (blue). (B) S(t)/k B from f S = 14 pN to f Q = 12 pN (red) and 2 pN (blue). (C) The time evolution of S(t)/k B for varying f S with fixed f Q = 12 pN. In this frame, we take the running average of S(t)/k B every 4.7 μ s.

In order to quantitatively describe the results of single-molecule measurements, the interplay between a number of factors has to be taken into account. The variables that can be controlled in experiments are f S, f Q, and v L, the speed with which the position of the transducer is contracted (over a length ΔL) or equivalently, r c, the rate of force contraction. Because the routes navigated by the biomolecule will depend on the precise protocol used (8, 9), these factors must be taken into account when comparing different experiments, even if the biomolecule under consideration is the same. For a system whose global folding obeys two-state kinetics, the two relevant time scales are the force-relaxation time, τQ (with τQ ≈ ΔL/v L or equivalently, τQ ≈ (f S − f Q)/r c) and the overall folding time, τF(f S,f Q). The dynamics of the folding trajectories, R(t), should depend on λ = τQ/τF. If λ ≪ 1, then folding takes place far from equilibrium, whereas in the opposite limit refolding occurs under near-equilibrium conditions. Thus, by altering the force-quench protocol, it is possible to control the collapse process and the folding routes for a given protein or RNA, even if f Q and f S are fixed.

Here, we explore quantitatively the scenarios that emerge for the folding of a RNA hairpin as a function of f Q and f S. The value of λ is controlled by altering τF(f Q,f S) in this work, rather than by adjusting the force contraction timescale τQ, as in refs. 6 and 7. We place particular emphasis on the general features of the physics underlying the early stages of length contraction. The folding trajectories for a RNA hairpin exhibit a long plateau of varying length in R(t), associated with the development of a FIMI. More generally, we show that the folding trajectories can be controlled by the choice of an appropriate force-quench protocol, which is succinctly expressed in terms of λ. The origin of the long-lived FIMIs when λ is small is explained by adapting de Gennes' picture of the kinetics of a coil to globule transition in flexible homopolymers. The combination of simulations and theory shows that the formation of long-lived FIMIs should be a generic feature of any biomolecule that adopts a compact structure, which implies that the polymeric nature of RNA and proteins, along with interactions that induce a globular state for sufficiently low f Q, will generically lead to a long plateau in R(t) as long as λ is small. These conclusions are supported by explicit simulations of force-quench studies of a flexible homopolymer in a poor solvent and a semiflexible chain model for DNA, in which the compact state adopts a toroidal structure. Our theory, which emphasizes λ as the relevant variable in determining the folding routes, naturally explains the apparent differences in the interpretation of force-quench folding of Ub by different groups (6, 7).

Results

Asymmetry in the Force-Quench Kinetics.

Force-quench refolding of a RNA hairpin (or a protein) can be initiated by using two distinct modes. In the first, the RNA is equilibrated at an initial f S > f m, where f m is the transition force at which the probabilities of being folded and unfolded are equal, and subsequently the force is quenched to various f Q values (f S → {f Q}), with f Q < f m (Fig. 1). We use simulations of the P5GA hairpin (10), with f m = 14.7 pN at T = 300 K (see Methods) to extract the dependence of τF on f Q from the dynamics of folding trajectories (Fig. 1 D and Fig. 2). Similarly, refolding can also be initiated by varying f S(> f m) and reducing the force to a single f Q(< f m) ({f S} → f Q) (see Fig. 1 A).

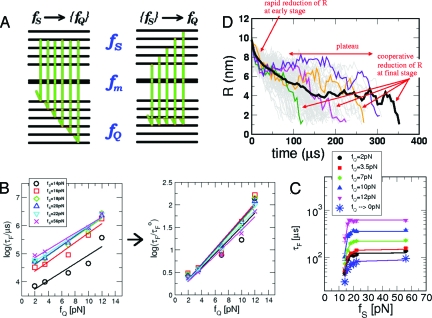

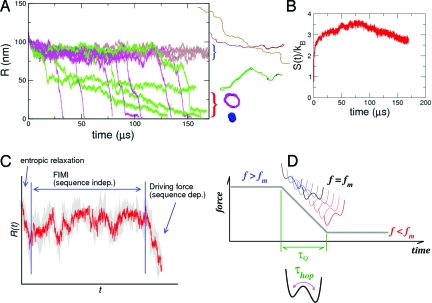

Fig. 1.

Force-quench kinetics of P5GA hairpins. (A) Refolding from a fixed f S to varying f Q (left) or from varying f S to a fixed f Q (right). (B) τF versus f Q starting from different f S. A fit to the Bell equation gives nm. The extrapolated value τF o to zero quench force is plotted in C (* symbols). (C) τF versus f S for each value of f Q. The variations of τF with f S are fit to Eq. 1. From the fit, we find (Δx UN/nm, τ(f Q)/μs) = (1.5,89.7), (2.5, 126), (1.8, 150), (2.6, 224), (3.8, 357), (4.4, 622) for f Q = 0, 2, 3.5, 7, 10, 12 pN, respectively. (D) Time traces of the molecular extension, R(t), upon force quench. Multiple time traces are plotted in gray, and the averaged time trace is shown by the thick black line. A few representative time traces are in color. The ensemble of time traces are shown for f S = 70 pN and f Q = 3.5 pN.

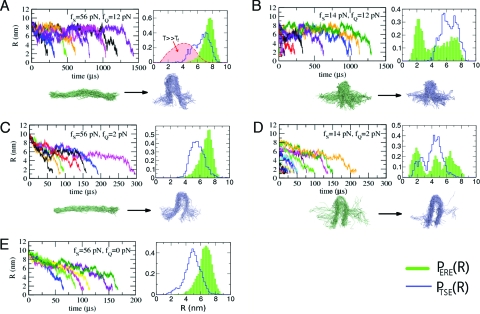

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the folding trajectories associated with force quench for various values of (f S,f Q). (A) f S = 56 pN → pN. (B) f S = 14 pN → pN. (C) f S = 56 pN → pN. (D) f S = 14 pN → pN. (E) f S = 56 pN → pN. P ERE(R) and P TSE(R) are shown in the right-hand frames of A–E, and the corresponding structures are shown for the ERE (left) and TSE (right). Thermally denatured ensemble P TDE(R) for T ≫ T f is shown in A.

The mean refolding time () for different values of f Q is fit to a Bell equation (6, 11, 12) (Fig. 1 B), where τF o(f S) is the folding time at f Q = 0, and Δx U → F ‡ is the distance between the transition state and the free energy minimum in the unfolded basin of attraction (UBA), which assumes that R is a good reaction coordinate. The slight upward curvature in log(τF) as a function of f Q is due to the dependence of Δx U → N ‡ on f Q (13 –15). When τF is rescaled by τF o(f S), the refolding times at different f S values nearly collapse onto a single curve (see the right-hand frame of Fig. 1 B). It follows that the time scale for crossing an effective free energy barrier (in the late stages of folding) is solely determined by f Q and is independent of f S. The microscopic model in refs. 15 and 16 provides an excellent fit to the simulation data (see also Fig. S2 and its legend in the SI Appendix). Here, we use the Bell equation to provide a physically simpler picture of the effect of force on the free energy profile.

Unlike the behavior of τF with varying f Q, the dependence of τF on f S cannot be explained by using the Bell model. We find that τF decreases sharply with f S for f S < 20 pN but saturates to a limiting value (which is also dependent upon f Q) if f S > 20 pN (Fig. 1 C). The saturation of τF for large f S suggests that the initial conformations of P5GA belong to the same structural ensemble [see the variations of the end-to-end distribution, P S(R), at each f S in Fig. S1A]. At low f S (f m ≲ f S < 20 pN), the molecules are partitioned into different ensembles. The initial population of molecules in the UBA, determined by f S, affects the average folding time. Because P5GA is two-state folder under force, the fraction of molecules in the UBA at f S is φUBA(f S) = 1/[1 + e (ΔFUNo−fSΔxUN)/kBT], where ΔF UN o = F U o − F N o and Δx UN = x U − x N are the difference in free energy and molecular extension between unfolded and folded conformations, respectively. By combining the f Q dependence of τF from Bell's model with φUBA(f S), we obtain a unified expression that describes force-quench folding time in both modes (see SI Appendix for details),

where δf S = f S − f m, δf Q = f m − f Q, with τo being the time scale in the absence of an activation barrier, and we have used ΔF UN o − f mΔx UN = 0. The fits using the two parameters and Δx UN, provides an excellent description of the simulation data (Fig. 1 C). The analytic result in Eq. 1 also shows the inherent asymmetry in the two modes for initiating folding by force quench.

Nonequilibrium Force-Quench Folding Is Reflected in R(t).

The dramatic variations in the refolding time τF(f Q,f S) (Fig. 1 B and C) are reflected in the folding trajectories, R(t), as f S and f Q are varied. In Fig. 1 D (see also Fig. 2), which shows the ensemble of force-quench trajectories with f S = 70 pN and f Q = 3.5 pN, we observe a rapid decrease in R(t) in the early stages of folding (stage 1), followed by a slowly decaying plateau of varying length (stage 2). The second stage is followed by an abrupt reduction to R ≲ 2 nm, corresponding to the hairpin formation (6, 18, 17, 13) (stage 3). The three stages of folding are well separated temporally, and the plateau length increases with increasing f Q. Although multistage folding has been discussed in the context of T-jump protein folding (5, 19, 20), the dramatic manifestation of time scale separation at an “early” stage of protein folding is unique to force-quench experiments. The nature of FIMI is different from that of a thermally collapsed intermediate state in that the FIMI state contains no intramolecular contacts (see Fig. 2 A and discussion of P TDE below). The rapid increase in the folding times (Fig. 1 B and 1D) is directly linked to the long-lived FIMIs. The plateau persists until the system reaches the transition state, R ≈ R TS = 4 nm, where R TS is the position of transition barrier at f = f m (Fig. S3 of the SI Appendix).

The process by which RNA navigates the folding landscape in stage 2 of the collapse process, during which R(t) is nearly a constant (Fig. 1 D), is assessed by monitoring the conformational changes in the hairpin. In order to illustrate these structural changes, we computed the distributions, P ERE(R) (ERE stands for entropically relaxed ensemble) “immediately after” the forcequench (between stages 1 and 2), and P TSE(R) (TSE denotes the transition-state ensemble) that gives the distribution function “immediately before” the final decrease of R(t) (between stages 2 and 3; see the SI Appendix for further discussion). The differences between P ERE(R) and P TSE(R) are illustrated in Fig. 2. As long as f S ≫ f m, P ERE(R) consists of a set of homogeneously stretched structures, whereas the structural ensemble of hairpin loops with disordered ends become dominant for f S ≲ f m (see Fig. 2 A–D). For f S = 56 pN, P TSE(R) is peaked at smaller values of R ≈ (6 − 7) nm, and becomes broader with decreasing f Q (see Fig. 2 A, C, and E). The ensemble of structures that are sampled in this second stage are the FIMIs, which are analogues of minimum-energy compact structures, postulated by Camacho and Thirumalai (21) for folding initiated by temperature quench. A comparison of P(R) in Fig. 2 A, C, and E with P TDE(R) (TDE denotes the thermally denatured ensemble; see the pink distribution in Fig. 2 A) shows that the conformations in the FIMI are unlikely to be sampled during a typical refolding initiated by temperature quench (17).

At f S = 14 pN ≲ f m (Fig. 2 B and D), P ERE(R) differs substantially from the distributions for f S = 56 pN ≫ f m (Fig. 2 A, C, and E). The ERE has an approximately bimodal distribution, similar to the initial distribution P S(R) at f = f m (10, 22) (compare P ERE(R) in Fig. 2 B and D with Fig. S1 of the SI Appendix at f S = 14 pN) and is far more heterogeneous than the ensemble at f S = 56 pN. With f S ≈ f m, the folding is initiated predominantly from molecules with a partially formed hairpin loop. In this case, the molecule refolds directly to the native state without a well-defined plateau in R(t). A plateau in R(t) will be manifested most clearly only when the force is quenched from a large f S(≫ f m) and f Q(≲ f m). The simulations also suggest that the lifetimes of the FIMIs depend on the protocol used to quench the force, which is determined by λ (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Rate of force quench in various experiments

| Experiments | vL (Slew rate) | τQ (Quench time) | τF(fQ) (Folding time) | a λ = τQ/τF(fQ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyubiquitin (6) | ∼ 104 nm/s | 3 msec | 0.2 s (fQ = 15 pN) | 0.015 |

| TAR RNA (8) | > 200 nm/s | 0.1 sec | ∼ 1 sec | 0.1 |

| RNAase H (I → N) (33) | (10 − 103) nm/s | (0.05 − 5) sec | 5 sec (I → U) | (0.01 − 1) |

| RNAase H (N → U) (33) | (10 − 103) nm/s | (0.05 − 5) sec | 3,000 sec (N → U) | (1/60,000 − 1/600) |

| Ubiquitin dimer (7) | 5 nm/s | ∼ 0.16 sec | ≳ 5 msec (fQ = 0 pN) | ≲ 32 |

| P5GA hairpin (simulation) | ∼ 1011 nm/s | 47 ps | (10 − 1,000) μ s | (10−9 − 10−6) |

| WLC (simulation) | ∼ 1013 nm/s | 0.5 ps | ≳ 100 μ s | ≲ 5 × 10−9 |

a For λ ≪ 1, we expect, a nonequilibrium effect, which leads to a population of long-lived FIMIs. In the opposite limit, folding occurs close to equilibrium conditions. The values of λ for Ub explain the differences in the refolding found in refs. 6 and 7. The value of λ in all our simulations are extremely small and cannot be realized in AFM experiments. However, we expect qualitative changes in R(t) only when λ > 1, and hence our simulation results are qualitatively similar to the small λ(≪ 1) used in ref. 6. WLC, worm-like chain.

The evolution from the ERE to the TSE, which occurs over a time scale determined by the length of the plateau, is associated with a search process leading to a nucleation step in the hairpin formation. We have shown previously, in a force-quench simulation with f Q = 0, that the dynamics of the plateau is associated with a search for the native dihedral angles (trans → gauche transition) in the tetra-loop region (13, 17). However, the plateau formation in R(t) is a generic feature of force-quench dynamics and has also been observed in recent experiments on polyubiquitin, I27, and the PEVK protein from titin (6, 23). Interestingly, the formation of long-lived FIMIs also occurs in force-quench dynamics of semiflexible chains and flexible homopolymers (see Discussion).

Link Between Entropy Production and the Collapse Dynamics.

The transition from the stretched state to the folded state that occurs through FIMIs can be described by using time-dependent changes in the entropy. From the ensemble of force-quench time traces, R(t), we estimate the entropy of the molecule as a function of time by using

where P(R,t) is the end-to-end distribution function obtained directly from the ensemble of trajectories. At long times, P(R,t → ∞) will reduce to the distribution for a given system. The time-dependent entropy is computed directly from the data generated from experiments or simulations, giving this approach a practical use, and thus captures the nonequilibrium behavior in all force regimes and over all time scales. Note that Eq. 2 makes no assumptions about a particular model for P(R,t) but is strictly valid only if R can adequately describe the conformation of the molecule of interest. Fig. 3 shows S(t) computed for four different pairs of (f S,f Q). Interestingly, changes in S(t) are nonmonotonic when the system begins from a high stretch force (f S = 56 pN, Fig. 3 A), whereas the S(t) decreases monotonically upon force-quench from f S = 14 pN (Fig. 3 B). The quantitative analysis using S(t) clarifies the dynamics in the ensemble of time traces (Fig. 2). The evolution of the end-to-end distribution, P S(R) → P ERE(R) → P TSE(R) → P NBA(R), is due to changes in the dynamic evolution of the entropy (Eq. 2) which progresses from a low (stretched) → medium (ERE) → high (FIMIs, TSE) → low (NBA) value as the hairpin folds, especially when the initial ensemble of states is fully stretched (R ≫ 4 nm in Fig. S2 of the SI Appendix). At f S = 14 pN, P S(R) is bimodal and S(t) with a maximum value at t = 0, and decreases monotonically as S(t)/k B ∼ Φe −t/τf + (1−Φ)e −t/τs where Φ, τf and τs are f Q -dependent for the same value of f S. The time constants τf and τs correspond to collapse of fast- and slow-track molecules in the multidimensional free energy landscape (with τf < τs), and Φ is the fraction of fast collapsing molecules (1). The fast and slow tracks are associated with the dynamics of collapse, starting from within the NBA (R < 4 nm) and UBA (R > 4 nm), respectively. We find Φ = 0.29, τf = 33.8 μs, τs = 715 μs for f Q = 12 pN, and Φ = 0.47, τf = 81.3 μs, τs = 181 μs for f Q = 2 pN. A smaller value of f Q increases the fraction of conformations in the folding route starting from NBA to the native state. The force-quench dynamics from the force-denatured ensemble with f S = 14 pN is an example of the kinetic partitioning mechanism (1) and shows that the mechanisms of hairpin formation can be surprisingly complex (8).

The transition from the monotonic to nonmonotonic decay of S(t) occurs at f S ≈ 16 pN (Fig. 3 C), and the time scales for S(t) to attain its maximum value are similar for f S = 18 − 56 pN. However, the entropies of the initial structural ensemble, S(0), are different and decrease as f S increases. This finding provides insights into why τF saturates for f S ≥ 18 pN in Fig. 1 C, because the P5GA hairpin is predominantly in the UBA for f S > f m + δf 1/2 = 14.7 + 1.2 pN ≈ 16 pN, where δf 1/2 is the half-width of force fluctuations around f m (see SI Appendix for details).

The Expanding Sausage Model Under Tension Captures the Physics of Force-Quench Refolding of Biopolymers.

Although the nonequilibrium behavior of the hairpin, reflected in R(t) and the time scales for hairpin formation, is shown for P5GA (Figs. 1 and 2), the dynamics of contraction of the molecule upon rapid quench should be a generic phenomenon, provided λ is small and a driving force leads to the development of a compact structure for sufficiently low f Q. In order to illustrate the generality of the FIMI that gives rises to the second stage of contraction (Figs. 1 and 2 and ref. 6), we provide a theoretical description by adapting de Gennes' model (24) for collapse kinetics of a flexible coil. By using an “expanding sausage model,” de Gennes envisioned that the collapse (upon temperature quench to T = T Θ − ΔT < T Θ, the Flory Θ-temperature) progresses from a randomly distributed string of thermal blobs of size ξ(= ag 1/2) (where g[= (T Θ/ΔT)2] is the number of monomer constituting each blob), to a sausage-like collapsed structure. The driving force in this picture (see Fig. S4A) is the minimization of the surface tension in a poor solvent (T < T Θ).

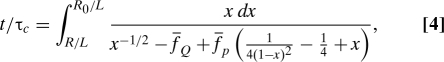

To describe the second stage in the force-quench dynamics (or more generally for any biopolymer that undergoes a stretch → collapse transition) using the generalization of the expanding sausage model, we write the free energy under tension as

|

where the first term is the driving force for collapse (F C = γA where A is the surface area of a thermal blob). We rewrite F C ∼ 2k B T(πΩR)1/2/ξ2, where the surface tension for a thermal blob is γ ≈ k B T/ξ2, and Ω is the volume of the sausage, assumed to be constant throughout the collapse process (24). The second term in Eq. 3, F f = −f Q R, accounts for the mechanical work. The third term in Eq. 3, which enforces chain inextensibility under the applied tension, is required to incorporate the sharp increase of mechanical force at R ≈ L, observed in the P5GA hairpin (see Fig. S1B). A simplified version of the sausage model, where inextensibility is not taken into account, is presented in the SI Appendix. The details of the free energy (Eq. 3) are not expected to change the qualitative picture of the collapse kinetics that emerges when using the expanding sausage model to describe force-quench dynamics as long as each term is taken into account. The effect of the stretch force f S on the folding kinetics is introduced through the initial equilibrium extension R 0, which for f S ≫ k B T/l p(≡ f p) is .

We equate the rate of free energy reduction of the system, , with the entropy production due to dissipation, (24), where we have used the Stokes–Einstein relation and a damping force f ≈ −ζv ≈ −ηRv. The friction coefficient ζ ≈ ηR, where R is the size of collapsed polymer in the longitudinal direction and , is the velocity. By equating , we get

|

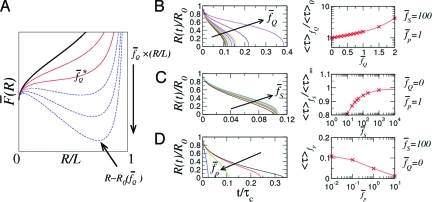

where for f S ≫ f p and the forces are scaled as for α = S, Q, and p, and with . The ratio R(t)/R 0 ≡ Σ(t), which is interpreted as the survival probability of the unfolded state upon force quench f Q, can be determined by numerically integrating Eq. 4 (see the left columns of Figs. 4 B–D). The average folding time (or mean first passage time) is τF({f α}) = 〈τ〉{fα} = ∫0 τ* dtΣ(t;{f α}), where τ* satisfies R(τ*) = 0. The results of τF for various combinations of ( Q, S, p) are given in the right columns of Fig. 4 B–D. In agreement with our simulation results (see also refs. 13, 17, and 18), as well as force-quench experiments on poly-Ub (6), the sausage model for the worm-like chain (WLC) shows a sharp decrease in R(t) at an early stage of the force-quench dynamics, after which a plateau in R of variable length develops, before an abrupt collapse to R = 0 (see Fig. 2). A long time plateau is observed for a stiffer biopolymer (small f p) and for larger f Q (Fig. 4 B and D). In agreement with the more-detailed P5GA simulations, τF increases exponentially at small quench forces () with a slight upward curvature for larger f Q (compare Fig. 4 B). The dependence of τF on the stretch force f S is typically small and saturates when (compare Figs. 1 C and 4 C).

Fig. 4.

The expanding sausage model for force-quench dynamics. (A) The free energy profile as a function of R for increasing tension. The free energy profile F(R) is plotted in dimensionless form by using . Two stable, free energy minima occur at R = 0 and R = R 0(f Q) ≲ L when . The profiles show that R TS decreases and R 0 increases with increasing f. In B–D, the dynamics of R(t) (left) and the average refolding time 〈τ〉 = τF (right) are shown for varying , , and chain flexibility (), respectively.

A word of caution is appropriate. Eq. 4, which is derived in the absence of fluctuating force (noise term in the Langevin equation), is valid only for , where is the force beyond which a finite free energy barrier for refolding develops (the dotted energy profiles in Fig. 4 A). Above , there is a barrier to refolding, , and a valid solution to Eq. 4 cannot be found for all t > 0. De Gennes' approach (24) is not applicable for rate processes (25) that involve crossing a free energy barrier. Physically, the residence time in the FIMI state becomes infinite in the absence of noise. The analog of was referred to as “spinodal” or as a “coercive field” in ref. 26 in which the nonequilibrium relaxation of spin systems was studied. Therefore, to account for the force-quench dynamics when , we use Kramers' theory for barrier crossing, assuming that R (under tension) is a good reaction coordinate, an approach that is consistent with other estimations of the transition time (27, 28). In so doing, it is assumed that under tension (f Q≠0) that results in the suppression of internal fluctuations, R is a good reaction coordinate. The refolding time τF scales with the effective height of the free energy barrier as τF ∼exp(δF ‡) where . For , one can show (see SI Appendix for details)

|

For small or increasing flexibility (), τF in Eq. 5 deviates significantly from Bell's expression [] (13 –15). We stress that Eq. 5 is only approximate and is shown to emphasize that activated transitions (in contrast to Eq. 4) dominate the approach to the ordered state.

Although additional factors, such as topological constraints due to self-avoidance (29) or other interactions, may alter the dynamic characteristics (for instance, the dependence of τF on f S or f Q), the generic feature of the emergence of a FIMI state upon force quench, also evidenced in the force-quench collapse dynamics of polymer chain under poor solvent conditions (see Discussion), is satisfactorily captured by the simple model.

Discussion

Implications for Experiments.

Our finding that the very nature of folding can be altered by the depth of quench as well as the rate of quench readily explains the different conclusions reached in the refolding of Ub (7). As shown in Figs. 1 and 2, the lifetime of the FIMIs, leading to the plateau in R(t), arises only if the ratio λ = τQ/τF(f Q,f S) is small. Under the experimental conditions in ref. 6, λ ≈ 0.15, whereas in the more recent AFM experiments, λ ≈ 32 (7) (see Table 1 for details). Consequently, the experiments by Schlierf and Rief (7) are closer to equilibrium conditions than the force-quench refolding reported in ref. 6. We predict that the apparent differences between the conclusions reached in refs. 6 and 7 are solely due to differing values of λ. The generality of these findings can be further appreciated from the study of Li et al. on TAR RNA (λ = 0.1, see Table 1), which showed evidence for the development of a plateau (see figure 3 A in ref. 8), although its importance was not discussed. Our findings also imply that only by varying λ over a wide range is it possible to discern the multiple stages in folding and firmly establish a link between collapse and folding transitions.

FIMIs Are a Generic Feature of Force-Quench Dynamics.

The sharp transitions in R(t), from its value in the second stage to the native compact structure in the third stage, is reminiscent of a weak first-order phase transition. Analyses of P TSE(R) for P5GA (Fig. 2 A) show that the formation of the hairpin loop from a FIMI is the key nucleation event in bringing the stretched RNA into its native-like hairpin structure. Because the simulations on RNA hairpins and the expanding sausage model suggest the long plateau only depends on the characteristic time scales associated with the folding polymer and the experimentally controlled variables in force quench, a similar behavior should be observed even in polymers that do not have a unique native structure but can undergo a transition to a globular state. To this end, we consider the dynamics of R(t) in homopolymers (flexible and worm-like chains) in a poor solvent upon force quench. The simulation details are in the SI Appendix.

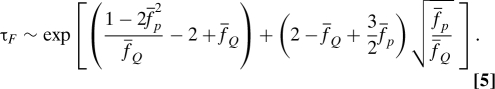

Collapse of semiflexible chain.

In the absence of force, the thermodynamically stable state of a semiflexible chain in a poor solvent is a toroid (see Fig. 5 A). We consider the collapse of a stiff worm-like chain (bending rigidity k b = 80k B T; see Eq. 8 of the SI Appendix) that is initially equilibrated at f = f S = 83 pN, and the force is suddenly quenched to f Q = 4 pN. From the time traces of R(t) in Fig. 5 A, we surmise that the transition to the toroidal structure occurs in three stages, just as for the P5GA hairpin and Ub (6). Within our simulation times (≲ 170 μ s), some molecules adopt toroidal (magenta) or racquet structures (green), whereas others (brown) fluctuate around large values of R without adopting any ordered structure. These findings for the formation of toroids for the WLC are in quantitative accord with experiments on the dynamics of force-quench collapse of λ- DNA, which showed that toroid formation occurs in a stepwise, quantized manner (30) and is in agreement with the forced unfolding of the lattice model of he proteins (31).

Fig. 5.

Polymer collapse in a poor solvent upon force quench. (A) The collapse of a WLC in a poor solvent. (B) Toroidal, single racquet, or multiple racquet structures are formed in various trajectories. (C) The entropy production using Eq. 2, displaying the low → high → low pathway from high f S to low f Q. (D) Linear reduction in force over a period, τQ, during which the free energy gradually changes from a profile with f > f m to one with f < f m. Depending on the time scale for hopping between the native and unfolded basins of attraction, τhop, in comparison with τQ, the pattern of relaxation dynamics upon force quench can be greatly affected.

The entropy production, S(t), of a collapsing WLC is shown in Fig. 5 B only for those molecules that form an ordered structure (the trajectories grouped in the red curly bracket in Fig. 5 A; see also Fig. S5 in the SI Appendix for complete set of trajectories). The low entropy of the initial, highly stretched state increases until it attains a maximum value, corresponding to an ensemble dominated by the FIMIs, after which the entropy slowly decays to a value in the more ordered, low-entropy state. This finding is in agreement with the three-stage collapse dynamics of the simpler RNA hairpin with a well-defined folded structure.

Collapse of flexible polymers in a poor solvent.

To further demonstrate that bending rigidity in the semiflexible chain plays no special role in leading to FIMIs, we have considered the stretch → globule transition of a flexible hompolymer in a poor solvent under force-quench conditions (see SI Appendix text for details). The final globular structure, in the absence of force, forms continuously from the ends of the chain (a pearl-necklace ensemble), with no evidence of a plateau in the collapse (see Fig. S6A of the SI Appendix). However, the continuous collapse transition becomes cooperative and weakly first order by choosing a large quench force f Q = 75 pN (Fig. S6B), due to the formation of FIMIs.

These two examples for homopolymers and the results for RNA hairpin show that the value of λ, and not the specific architecture of the folded structure, dictate the collapse in the intermediate stages. The expected changes in R(t) of a biomolecule (or a homopolymer in a poor solvent) upon a rapid f S → f Q quench (small λ) must occur in multiple stages (Fig. S5), with stages 1 and 2 being determined by entropy growth (stage 1). The search for the folding nuclei (32) that can further drive structure formation (stage 3) and sequence-dependent effects arises in the final stages of folding (Fig. 5 C).

If the force is quenched rapidly, the biomolecule will be far from equilibrium when the first nucleation event occurs, which will drastically change the dynamics of the folding process. Folding occurs in a near-equilibrium manner either if the force is relaxed slowly (Fig. 5 D), so that the internal modes of the biomolecule equilibrate, or if the quench force is sufficiently large that there is a significant barrier to folding. For a slow decrease in the force, the relevant time scale is τQ = ΔL/v L, whereas the relevant time scale for the barrier crossing event will be τhop(f Q) (Fig. 5 D). Thus, near folding occurs at near equilibrium for λ = τ Q/τhop ≫ 1, whereas nonequilibrium folding occurs in the opposite limit. Variations in the experimental protocol have to be taken into account in elucidating the pathways explored during the folding process.

Methods

The P5GA hairpin, as represented by using the self-organized polymer model (see ref. 22 for the energy function and simulation method), is a two-state folder with a transition midforce of f m = 14.7 pN (10). We probe the refolding kinetics for multiple pairs of initial and quench forces, (f S, f Q), whose magnitudes range from 14 ≤ f S ≤ 70 pN and 2 ≤ f Q ≤ 12 pN (see Fig. 1 A). The force-quench refolding kinetics for 100 molecules were simulated beginning with an initial tension (f S) and quenched to a final tension (f Q). The refolding time of the i th molecule, τF(i), was defined as the first time the hairpin gained more than 95% of native contacts after the tension was reduced to f = f Q.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation Grant CHE 09-14033 (to D.T.) and the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (R01-2008-000-10920-0, KRF-C00142, KRF-C00180 and 2009-93817) (to C.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0905764106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Thirumalai D, Hyeon C. RNA and protein folding: Common themes and variations. Biochemistry. 2005;44:4957–4970. doi: 10.1021/bi047314+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Theory of protein folding. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dill KA, Ozkan SB, Shell MS, Weikl TR. The protein folding problem. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:289–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.092707.153558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shakhnovich E. Protein folding thermodynamics and dynamics: Where physics, chemistry, and biology meet. Chem Rev. 2006;106:1559–1588. doi: 10.1021/cr040425u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thirumalai D. From minimal models to real proteins: Time scales for protein folding kinetics. J Physique I. 1995;5:1457–1467. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez JM, Li H. Force-clamp spectroscopy monitors the folding trajectory of a single protein. Science. 2004;303:1674–1678. doi: 10.1126/science.1092497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlierf M, Rief M. Surprising simplicity in the single-molecule folding mechanics of proteins. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:820–822. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li PTX, Collin D, Smith SB, Bustamante C, Tinoco I., Jr Probing the mechanical folding kinetics of TAR RNA by hopping, force-jump, and force-ramp methods. Biophys J. 2006;90:250–260. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.068049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li PTX, Bustamante C, Tinoco I., Jr Real-time control of the energy landscape by force directs the folding of RNA molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7039–7044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702137104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyeon C, Morrison G, Thirumalai D. Force dependent hopping rates of RNA hairpins can be estimated from accurate measurement of the folding landscapes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9604–9606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802484105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell GI. Models for the specific adhesion of cells to cells. Science. 1978;200:618–627. doi: 10.1126/science.347575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li MS, Hu CK, Klimov DK, Thirumalai D. Multiple stepwise refolding of immunoglobulin I27 upon force quench depends on initial conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:93–98. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503758103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyeon C, Thirumalai D. Forced-unfolding and force-quench refolding of RNA hairpins. Biophys J. 2006;90:3410–3427. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.078030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyeon C, Thirumalai D. Measuring the energy landscape roughness and the transition state location of biomolecules using single molecule mechanical unfolding experiments. J Phys Condens Matter. 2007;19:113101. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudko OK, Hummer G, Szabo A. Intrinsic rates and activation free energies from single-molecule pulling experiments. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:108101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.108101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dudko OK, Hummer G, Szabo A. Theory, analysis, and interpretation of single-molecule force spectroscopy experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15755–15760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806085105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyeon C, Thirumalai D. Multiple probes are required to explore and control the rugged energy landscape of RNA hairpins. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1538–1539. doi: 10.1021/ja0771641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyeon C, Thirumalai D. Mechanical unfolding of RNA hairpins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6789–6794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408314102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sali A, Shakhnovich E, Karplus M. How does a protein fold. Nature. 1994;369:248–251. doi: 10.1038/369248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camacho C, Thirumalai D. Kinetics and thermodynamics of folding in model proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6369–6372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camacho C, Thirumalai D. Minimum energy compact structures of random sequences of heteropolymers. PhyS Rev Lett. 1993;71:2505–2508. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyeon C, Thirumalai D. Mechanical unfolding of RNA: From hairpins to structures with internal multiloops. Biophys J. 2007;92:731–743. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walther KA, et al. Signatures of hydrophobic collapse in extended proteins captured with force spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7916–7921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702179104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Gennes PG. Kinetics of collapse of a flexible coil. J Physique Lett. 1985;46:L639–L642. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chandrasekhar S. Stochastic problems in physics and astronomy. Rev Mod Phys. 1943;15:1–89. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binder K. Time-dependent Ginzburg–Landau theory of nonequilibrium relaxation. Phys Rev B. 1973;8:3423–3438. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshinaga N. Folding and unfolding kinetics of a single semiflexible polymer. Phys Rev E. 2008;77:061805. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.77.061805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halperin A, Goldbart PM. Early stage of homopolymer collapse. Phys Rev E. 2000;61:565–573. doi: 10.1103/physreve.61.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grosberg AY, Nechaev SK, Shakhnovich EI. The role of topological constraints in the kinetics of collapse of macromolecules. J Phys. 1988;49:2095–2100. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu WB, et al. Compaction dynamics of single DNA molecule under tension. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:15040–15041. doi: 10.1021/ja064305a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klimov DK, Thirumalai D. Stretching single-domain proteins: Phase diagram and kinetics of force-induced unfolding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6166–6170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo Z, Thirumalai D. The nucleation-collapse mechanism in protein folding: Evidence for the non-uniqueness of the folding nucleus. Folding & Design. 1997;2:277–341. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(97)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cecconi C, Shank EA, Bustamante C, Marqusee S. Direct observation of three-state folding of a single protein molecule. Science. 2005;309:2057–2060. doi: 10.1126/science.1116702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.