Preface

Neuronal inclusions comprised of the microtubule-associated protein tau are found in a number of neurodegenerative diseases, commonly known as tauopathies. In Alzheimer's disease, the most prevalent tauopathy, misfolded tau is probably a key pathological agent. The recent failure of Aβ-targeted therapeutics in Phase III clinical trials suggests that it is timely and prudent to consider alternative drug discovery strategies for Alzheimer's disease. Here we focus on those directed at reducing misfolded tau and compensating for the loss of normal tau function.

Introduction

The brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) and a number of other central nervous system disorders, such as frontotemporal dementia, Pick's disease, corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy, contain inclusions comprised of the microtubule-associated protein tau1,2. This shared pathological feature has resulted in these various neurodegenerative diseases being called “tauopathies”, although there are clear distinctions in the phenotypic manifestations of these disorders. The insoluble tau deposits found in the brains of patients with tauopathies are comprised of fibrils and are typically found within the cell bodies and dendrites of neurons3, where they are referred to as neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and neuropil threads (Figure 1). The occurrence of fibrillar tau inclusions in tauopathies suggests that they play a critical role in the observed clinical symptomology and pathology. This hypothesis is supported by correlations of NFT density and cognitive decline in AD4-6. However, no tau mutations have been identified in AD, whereas inherited early-onset AD can result from mutations in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) or presenilins that lead to increased synthesis of the amyloid β (Aβ) peptide found within the hallmark senile plaques of AD brain7,8. These genetic data led to an Aβ-centric view of AD that, while still prevalent, was tempered by the later discovery that FTD with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) resulted from tau gene mutations9,10. Because FTDP-17 patients have AD-like tau deposits in their brains11, it seems reasonable to surmise that this common tau pathology causes disease in AD and other tauopathies, albeit in the absence of tau gene mutations. In the case of AD, there is thus compelling evidence to implicate both Aβ and tau as disease-causing agents. Although the linkage between these two molecules in AD is not fully understood, the prevailing viewpoint is that misfolded Aβ species initiate cellular events that result in later tau aggregation12.

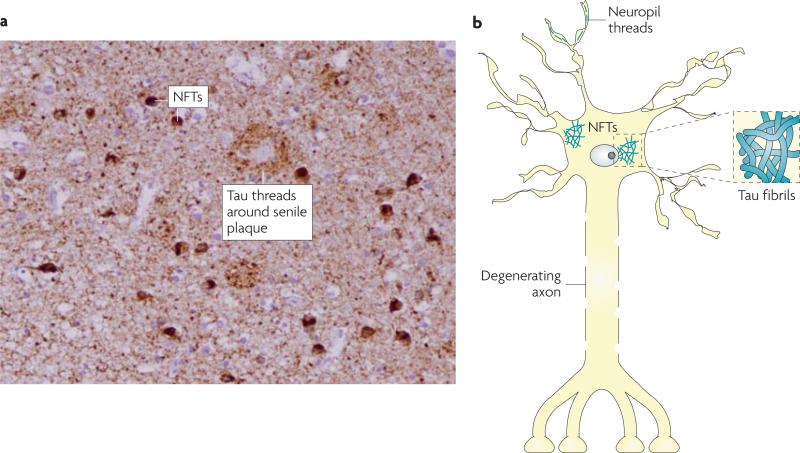

Figure 1. Tau pathology in AD and related tauopathies.

At autopsy, the brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease or related tauopathies show abundant neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and neuropil threads that are comprised of pathological tau. These tau deposits can be visualized by treating brain slices with certain silver stains or by immunostaining with antibodies that recognize tau (as shown in A, with darkly-stained NFTs and dense tau neuropil threads that yield a nearly uniform brown staining in a hippocampal section of an Alzheimer's disease brain). A schematic representation of NFTs and neuropil threads within a neuron is shown in B, with an example of tau fibrils that resemble those found in NFTs depicted in the associated inset.

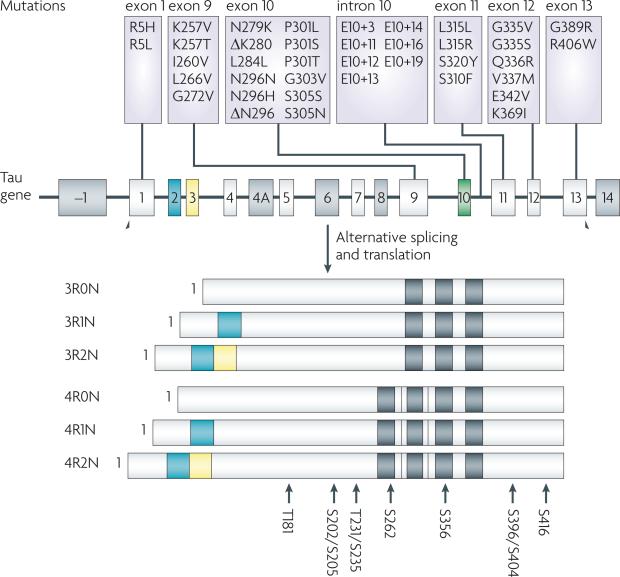

Tau stabilizes microtubules (MTs) within cells13,14 and is particularly enriched in neurons15, where MTs serve as the “tracks” upon which cellular cargo is transported in axons (Figure 2). Humans express six tau isoforms that result from alternative splicing of exons 2, 3 and 1016,17, and the absence or presence of exon 10 leads to tau species that contain either three (3-R) or four (4-R) carboxyl-terminal microtubule (MT)-binding repeats (Figure 3). Not surprisingly, 4-R tau isoforms bind MTs with greater avidity than 3-R forms18, and there is approximately equimolar 4-R and 3-R tau in normal individuals. Interestingly, a significant proportion of the known tau mutations in FTLD-17 affect exon 10 splicing (Figure 3), leading to an increase in the 4-R/3-R ratio2,9,10 and suggesting that over-stabilization of MTs results in disease. An alternative explanation is that 4-R tau more readily forms aggregates that contribute to disease19. The remaining FTLD-17 tau mutations result in missense mutations within the coding region of the gene (Figure 3)2,9,10, and studies show that some of these amino acid changes decrease the ability of tau to bind MTs20-22 and/or increase the propensity of tau to form insoluble fibrils in vitro23-25.

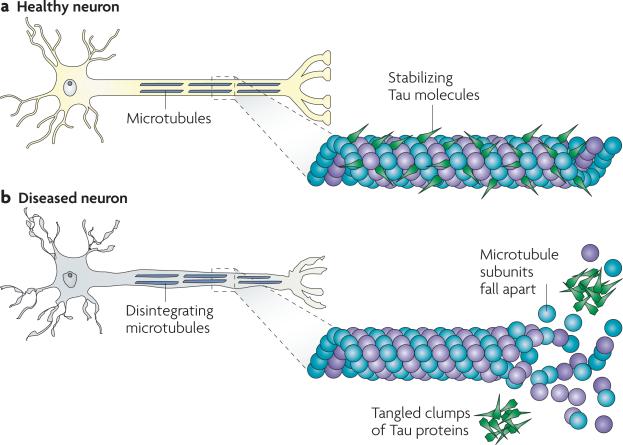

Figure 2. Tau in healthy neurons and in tauopathies.

Tau facilitates microtubule (MT) stabilization within cells and it is particularly enriched in neurons. MTs serve as “tracks” that are essential for normal trafficking of cellular cargo along the lengthy axonal projections of neurons, and it is thought that tau function is compromised in Alzheimer's disease and other tauopathies. This probably results both from tau hyperphosphorylation, which reduces the binding of tau to MTs, and through the sequestration of hyperphosphorylated tau into neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) so that there is less tau to bind MTs. The loss of tau function leads to MT instability and reduced axonal transport, which could contribute to neuropathology.

Figure 3. The Tau gene, known Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) mutations and sites of hyperphosphorylation.

Tau is a mult-exonic gene that undergoes alternative post-transcriptional splicing of exons 2 (orange), 3 (yellow) and 10 (green) to yield six isoforms in the brain. Exons 9-12 encode microtubule (MT)-binding repeat domains and the exclusion or inclusion of exon 10 results in tau with three (3-R) or four (4-R) MT-binding domains, respectively (black bars). Tau mutations that result in FTDP-17 map primarily to exons 9-12 or to the intronic region between exons 10 and 11, with the latter increasing the prevalence of exon 10-containing 4-R tau. There are no reported tau mutations in Alzheimer's disease, but hyperphosphorylated tau inclusions are formed that resemble those seen in FTDP-17. There are ~40 reported sites of tau phosphorylation, and the major hyperphosphorylation sites91 are shown at the bottom of the figure.

The causes of tau aggregation in sporadic tauopathies are not fully understood. One post-translational modification that seems to alter the properties of tau in ways that resemble FTLD-17 mutations is hyperphosphorylation, which occurs in all tauopathies26,26,27. Tau is normally phosphorylated at multiple serine (ser) and threonine (thr) residues28, and hyperphosphorylation (Figure 3) reduces MT binding29-32,32 and may enhance aggregation31,33,34. Therefore, it is possible that changes in protein kinase and/or phosphatase activities could enhance tau phosphorylation with consequent loss-of-function (LOF) and/or gain-of-function (GOF) toxicities. Additional post-translational modifications may also contribute to tau dysfunction. For example, tau undergoes a specific type of ser/thr O-glycosylation and these modifications can reduce the extent of tau phosphorylation35,36. Thus, a decrease in tau O-glycosylation could result in increased hyperphosphorylation. Tau can also be tyrosine phosphorylated37, sumoylated and nitrated38, although it is not fully understood what effects these modifications have on tau. Another post-translational event that may facilitate tau aggregation is proteolytic cleavage, as it appears that both calpain39 and caspases40 can act on tau to produce fragments that may have an increased propensity to aggregate. Finally, it is known that tau fibrillization in vitro requires the presence of anionic co-factors such as heparin, RNA or negatively-charged lipids41,42, and it is possible that changes in the intracellular content of one or more such molecules may facilitate tau deposition in tauopathies.

The knowledge gained from the FTDP-17 mutations and an increased understanding of how the post-translational modifications of tau affect its function has led to a growing interest in developing therapeutics that target pathological tau. Most tau-directed drug discovery programmes are in early research stages and are not nearly as advanced as Aβ-focused AD programmes. However, recent notable failures in pivotal clinical trials with agents such as tramiprosate43 and flurbiprofen44, which were aimed at reducing Aβ burden in the brains of AD patients, underline the need to pursue other therapeutic approaches including those that reduce pathological tau. It is thus timely to review recent advancements in tau-based drug discovery efforts and the relative merits of these strategies.

Compensating for Tau LOF

Evidence that tau mutations and hyperphosphorylation can affect MT binding suggests that impairment of MT function and axonal transport contributes to neurodegeneration in AD and related tauopathies (Figure 2). A reduction of the stabilized MT marker, acetyl-tubulin, has been observed in NFT-containing neurons within the brain of patients with AD45 and after tau deposition in a rat hippocampal slice model46. Importantly, a reduction in MT density and fast axonal transport (FAT) has been observed in a transgenic mouse model that develops hyperphosphorylated tau inclusions in neurons of the cortex, brainstem and spinal cord47. Finally, in patients with AD a reduced MT density was observed in pyramidal neurons relative to age-matched controls, although the change appeared to be unrelated to the presence of NFTs48.

It should be noted that there are data which contradict the viewpoint that tau LOF contributes to neurodegeneration. For example, FAT was not affected in tau knockout mice49, and human APP transgenic mice that were crossed with tau-deficient mice showed improved cognitive performance relative to the APP mice expressing normal amounts of tau50. However, constitutive gene knockout can lead to compensatory changes during development and it has been reported that tau knockout mice have elevated expression of the MT-associated protein 1a (MAP1a)51. Moreover, tau knockout mice are not normal as they develop cognitive as well as motor deficits with age, and primary hippocampal neurons from these animals show delayed axonal extension52,53. Inducible tau knockout mice have not yet been evaluated; these animals may provide a better measure of the significance of tau.

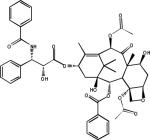

The hypothesis that tau LOF contributes to neuronal dysfunction has been further tested by treating tau transgenic mice that display MT and motor deficits with the MT-stabilizing drug, paclitaxel (Table 1)47,54. After three months of drug treatment, the mice showed a significant improvement of FAT and MT density relative to vehicle-treated animals. Furthermore, there was a marked improvement in motor function in the paclitaxel-treated mice. Because paclitaxel does not readily cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), the observed drug-induced changes presumably resulted from paclitaxel uptake at peripheral neuromuscular junctions with subsequent retrograde transport to spinal motor neurons. These results demonstrate that tau LOF can be compensated for by small molecule drugs, and that MT-stabilizing agents that readily cross the BBB might lead to similar improvements in tauopathy brains. Recently, the octapeptide NAP, which crosses the BBB, was found to promote MT assembly55. Intranasal NAP administration for three months to 9-month old transgenic mice that develop Aβ and tau deposits resulted in a reduction of tau phosphorylation as well as a lowering of Aβ levels56. Furthermore, in older transgenic mice that had developed moderate pathology, NAP treatment reduced tau phosphorylation, although Aβ levels were unaffected57. The mechanism whereby NAP alters tau phosphorylation and Aβ levels in young transgenic mice is unclear, as it is not evident that stabilization of MTs would lead to these changes. Nonetheless, these data are intriguing and support the concept that drug-induced stabilization of MTs could be beneficial in tauopathies.

Table 1.

Compounds directed to potential tauopathy drug targets

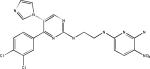

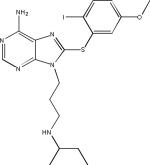

| Tau Kinase Inhibitors | MT-Stabilizer | ||

|---|---|---|---|

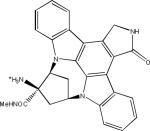

| SRN-003-556 |  |

Paclitaxel |  |

| AR-A014418 |  |

O-GlcNacase Inhibitor | |

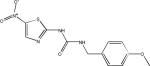

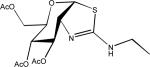

| Thiomet-G |  |

||

| CHIR98014 |  |

Hsp90 Inhibitors | |

| EC102 (presumed structure) |  |

||

| Alsterpaullone |  |

PU24FCl |  |

| SB216763 |  |

||

A challenge when attempting to treat AD and related tauopathies with MT-stabilizing compounds is identifying molecules that readily reach the brain. Although intranasal administration of NAP seemed to result in effective brain levels, many of the more traditional MT-stabilizing agents, including the taxanes, have relatively poor BBB penetration58. This is due, at least in part, to many of the taxanes being substrates of the P-glycoprotein transporter that actively pumps xenobiotics from the cells lining the BBB back into the blood59. Identifying MT-stabilizing compounds with good brain penetration is important not only because this is the site of pathology in human tauopathies, but also because compounds that readily pass the BBB will achieve efficacious brain concentrations at relatively lower plasma drug levels. Keeping peripheral levels of MT-stabilizing drugs as low as possible is important as these compounds are potent anti-mitotic agents that can have significant side-effects. Based on the absence of observable morbidities in the tau transgenic mice that showed motor improvements upon paclitaxel treatment54, there is hope that relatively low brain concentrations of MT-stabilizing drugs will be required to stabilize neuronal MTs in tauopathies. Further analysis of MT-stabilizing compounds to identify those that can gain access to the brain, followed by testing in animal models of tauopathy, will provide further information on the relative efficacy and safety of this approach.

Inhibition of Tau hyperphosphorylation

Challenges associated with reducing Tau phosphorylation

Normal tau is phosphorylated on a number of residues and the extent of this phosphorylation is increased dramatically in the brain of patients with AD60,61. Although ~40 ser/thr tau phosphorylation sites have been described62, only a small number of hyperphosphorylation sites are well-characterized (Figure 3); most of them flank the MT-binding domains, although ser262 and ser356 reside within these regions. Phosphorylation at ser262, thr231 and ser235 was found to reduce tau binding to MTs63, and phosphorylation or pseudophosphorylation of a number of sites has been demonstrated to enhance tau fibrillization31,33,64 although phosphorylation at ser214 and ser262 may prevent tau aggregation65. Because hyperphosphorylation could lead to tau LOF or GOF, identifying inhibitors of the appropriate kinases has considerable therapeutic appeal.

Kinase inhibitors are being actively pursued in the pharmaceutical industry for a number of clinical applications, particularly for the treatment of cancers. Nonetheless, there are significant challenges to the development of tau kinase inhibitors. Because current kinase inhibitors are generally directed to the common ATP binding site shared by all members of this family, achieving kinase selectivity has proven to be difficult66. Furthermore, inhibiting tau hyperphosphorylation requires an understanding of the specific enzymes involved in these modifications. A large number of kinases have been shown to be capable of phosphorylating tau in vitro, including proline-directed kinases such as extracellular signal-related kinase 2 (ERK2), glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) and cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (cdk5), as well as the non-proline-directed enzymes casein kinase 1 (CK1), protein kinase A (PKA), and microtubule affinity-regulating kinase (MARK)62,67,68. However, uncertainty remains about which of these is most important to tau hyperphosphorylation in human disease.

There is substantial support for CDK5 and GSK-3 being relevant kinases in tauopathies. GSK-3 exists in two highly homologous α and β isoforms, but because the reagents used in many studies do not differentiate between these two species their relative contributions are unclear. GSK-3 co-localizes with NFTs69, although there doesn't seem to be an up-regulation of GSK-3 activity in AD brain70. Overexpression of GSK-3β in transgenic mice has been reported to increase tau hyperphosphorylation and to cause behavioural deficits71,72. CDK5 activity73 and the levels of the CDK5 activator p35/p2574 have been reported to be up-regulated in the brain of patients with AD Like GSK-3, CDK5 has also been demonstrated to be associated with nascent NFTs75-77. In addition, co-expression of p25 and mutant human tau in mice led to the formation of NFTs with resulting neurodegeneration78. Interestingly, both CDK579 and GSK-3 have been implicated in the upregulation of Aβ synthesis, with inhibition of GSK-3α and GSK-3β reported to decrease Aβ levels80-82. Also, there seems to be a link between CDK5 and GSK-3β activity, as inhibition of CDK5 in mice overexpressing p25 led to an increase of tau phosphorylation by GSK-3β83. This implies that inhibition of CDK-5 may not lead to a desired reduction of tau hyperphosphorylation. Among the candidate non-proline directed tau kinases, MARK may arguably be the most relevant. MARK phosphorylates multiple MT-associated proteins in addition to tau and cells that overexpress this kinase show increased tau phosphorylation84. MARK is localized to tau tangles in the AD brain85 and overexpression of the MARK orthologue Par-1 in flies co-expressing human tau resulted in increased tau phosphorylation and enhanced neurotoxicity86.

A further challenge in developing tau kinase inhibitors, in addition to the issues mentioned above, is the possibility of target related side-effects as most kinases regulate several cellular processes. GSK-3 is perhaps best known for its involvement in glycogen metabolism and as a drug target for metabolic disease87. CDK5 is essential for survival in mice and has a key role in neuronal development88. Similarly, MARK is involved in axonal transport and neurite growth89,90. Although kinase inhibitors have been used successfully in oncology, it remains to be determined whether these molecules can be safely administered on a chronic basis for the treatment of tauopathies. Notwithstanding these concerns, a number of research groups have developed inhibitors of the key kinases implicated in tau phosphorylation. The details on the many classes of compounds that have been identified to date have been reviewed in references67,91. A small number of tau kinase inhibitors (Table 1) have progressed to efficacy testing in tau-based animal models (Box 1), and these data are briefly discussed here as they provide important information about the merits of this approach. In fact, the development of several transgenic mouse lines that overexpress tau with FTDP-17 mutations92 has provided important research tools for compound evaluation. These mice typically show an age-dependent formation of intraneuronal hyperphosphorylated tau inclusions that mimic many aspects of the NFTs observed in human tauopathies, including neuritic pathology and axonal degeneration.

Analysis of Tau phosphorylation inhibitors in animal models

Most in vivo efficacy studies of tau kinase inhibitors have examined the effects of GSK-3 inhibition. Administration of the GSK-3 inhibitor LiCl for ~one month to transgenic mice that overexpress mutant human tau resulted in a decrease of tau phosphorylation and a reduction of insoluble tau93,94. LiCl has effects on other enzymes besides GSK-3, but it has been shown that treatment with the relatively specific GSK-3 inhibitor AR-A014418 (Table 1) leads to a reduction of insoluble tau within these transgenic mice that is comparable to that observed with LiCl. A four-month LiCl treatment of young transgenic mice that express the shortest human tau isoform led to a reduction of tau pathology and behavioural improvement95. Interestingly, although decreased tau phosphorylation was observed during the initial month of dosing in these mice, this effect was not seen by the end of the dosing regimen95. Thus, the attenuated tau pathology in the LiCl-treated mice may have resulted from the transient inhibition of GSK-3 and/or from an increase in tau ubiquitination that was observed in these animals. More recently, LiCl was administered to transgenic mice that overexpress both mutant human tau and GSK-3β, and which develop age-dependent tau hyperphosphorylation accompanied by NFT formation. Treatment of pre-symptomatic animals with LiCl for 7.5 months prevented tau hyperphosphorylation and the onset of tau pathology, whereas administration of LiCl to mice with existing tau pathology resulted in a reduction of tau phosphorylation although NFTs persisted96. A comparable effect was observed when tetracycline-controlled GSK-3β expression was down-regulated in these older mice, suggesting that the effects of LiCl were specifically due to inhibition of GSK-3β96. Finally, LiCl has been administered to 15-month old transgenic mice that develop Aβ plaques and tau tangles in their brain97. Daily LiCl treatment for one month led to reduced tau phosphorylation without affecting Aβ plaque burden. However, the drug treatment did not rescue memory deficits within these animals. Although studies of LiCl in human AD subjects are sparse, a recent 10-week clinical trial of LiCl in 71 mild AD patients did not show clinical or biomarker efficacy98.

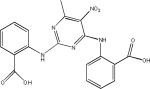

Although many in vivo studies of tau kinase inhibition have used LiCl, a few additional small molecule kinase inhibitors have been evaluated for efficacy. The non-specific kinase inhibitor SRN-003-556 (Table 1), which affects CDK5, GSK-3 and ERK2, was evaluated in mice that overexpress mutant human tau99. The compound was shown to significantly delay the development of motor deficits and decrease the amount of soluble hyperphosphorylated tau after nine weeks of dosing. However, no reduction in NFTs was observed, leading the authors to speculate that the negative effects of tau may have resulted from diffusible multimers. More recently, a large number of GSK-3 inhibitors were investigated in 12-day old rats that have elevated tau phosphorylation relative to adult animals100. Both LiCl and CHIR98104 were found to reduce tau phosphorylation in the cortex and hippocampus, whereas alsterpaullone and SB216763 (Table 1) were only effective in the hippocampus.

Finally, it should be noted that another potential approach to modifying tau phosphorylation is through manipulation of tau O-linked glycosylation101. Certain ser/thr residues of tau are post-translationally modified through the addition of β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNac), and the levels of tau phosphorylation and O-GlcNac have been demonstrated to be reciprocally regulated such that increased tau O-GlcNac results in decreased phosphorylation35,36. The cleavage of O-GlcNac from tau is mediated by the enzyme O-GlcNacase, and a recent study has demonstrated that acute administration of an inhibitor of this enzyme, thiamet-G (Table 1), to normal rats caused an apparent reduction of tau phosphorylation at ser396, thr231 and ser404102. Thus, it may be possible to modulate tau phosphorylation through inhibition of O-GlcNacase, although it should be noted that the single in vivo study with the O-GlcNacase inhibitor thiamet-G was conducted with normal rats that do not have hyperphosphorylated tau. As many intracellular proteins undergo O-GlcNac modification, the potential side-effects of chronic inhibition of O-GlcNacase will have to be carefully examined.

Inhibition of Tau assembly into oligomers and fibrils

As mentioned above, the conversion of soluble tau into oligomeric and fibrillar species could result in tau GOF and LOF toxicities. Thus, inhibiting tau assembly into multimeric structures might prevent the formation of toxic species and increase the levels of monomeric tau, which could contribute to MT stabilization. Although blocking protein–protein binding with small molecule drugs is generally believed to be difficult due to the large surface areas involved in such interactions, there is now growing evidence that tau multimerization can be disrupted with low molecular weight compounds (Table 2). These studies have been greatly facilitated by the discovery that tau can be induced to form well-defined fibrils in vitro in the presence of certain anionic co-factors, such as heparin or negatively-charged lipids42,103. Moreover, the formation of these tau fibrils can be readily monitored with fluorescent dyes that recognize the cross-β-fibril structure that is common of all amyloid fibrils (see Box 2). Although the tau fibrils formed in vitro bear verisimilitude to the PHFs observed in the brains of patients with AD, other tauopathies such as progressive supranuclear palsy are characterized by straight tau filaments2. Thus it remains to be determined whether a compound that blocks tau fibrillization in vitro will affect all types of tau fibrils.

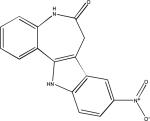

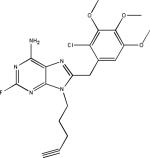

Table 2.

Tau fibrillization inhibitors

| Methylene Blue (Phenothiazines) |  |

| N774 |  |

| Daunorubicin (Anthracyclines) |  |

| N-Phenylamines |  |

| Phenylthiazolyl-hydrazides | |

| Rhodanines |  |

| Exifone (Polyphenols) |  |

| Quinoxalines |  |

| Aminothienopyridazines |  |

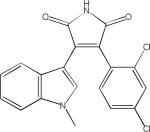

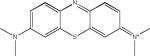

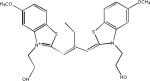

The first compound reported to inhibit tau–tau interactions was the dye methylene blue (Table 2), which was also shown to alter the structure of existing paired helical filaments (PHFs) isolated from the brain104. This molecule is now in clinical testing for AD and Phase II data presented at the 2008 International Conference on AD suggest that this compound had a positive treatment effect105, although larger Phase III studies are required to prove efficacy. Another dye-like molecule, N744, has also been identified as an inhibitor of full-length tau fibrillization and like methylene blue this compound could disaggregate existing filaments106. However, at higher concentrations N744 forms aggregates that were found to increase tau assembly107.

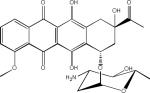

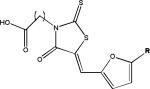

A number of laboratories have screened compound libraries (Box 2) with the goal of identifying inhibitors of tau fibrillization (see Table 1 for examples). For example, the Mandelkow laboratory completed high-throughput screening (HTS) of ~200,000 compounds in an assay in which fibrillization of a 3-R tau fragment was evaluated by thioflavine S (ThS) fluorescence108. This led to the identification of a number of anthraquinone inhibitors of tau fibril formation, including daunorubicin and adriamycin. These compounds also caused disaggregation of pre-formed tau fibrils if concentrations were increased above those required to prevent fibrillization, indicating that it is possible to find compounds that can both block the formation of tau fibrils and dissolve existing aggregates. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that an anthraquinone analogue could reduce the formation of tau inclusions in N2a neuroblastoma cells that overexpress a 4-R human tau fragment. A number of N-phenylamine tau fibrillization inhibitors identified from this screen were later shown to also be active in the N2a cell model109. This group subsequently developed a pharmacophore model from the active compounds identified after HTS110, resulting in the identification of a phenylthiazolyl-hydrazide (PTH) series of compounds that prevented tau fibrillization as well as aggregation in the N2a cellular model111. Finally, a rhodanine series of tau fibril inhibitors was identified112 by this team that disaggregated pre-formed tau fibrils and prevented tau aggregate formation in the N2a cells.

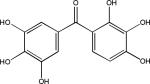

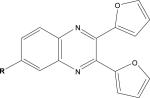

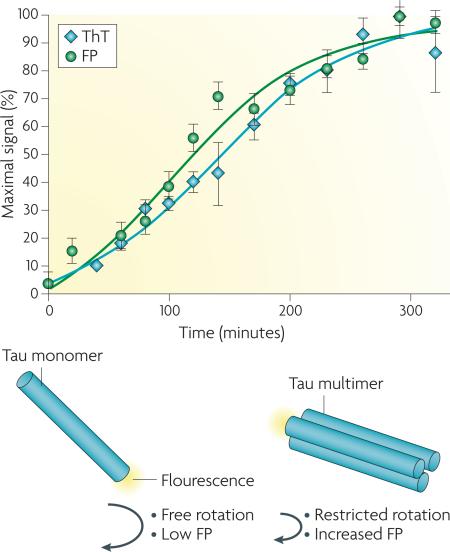

Other researchers have also screened compound collections to identify inhibitors of tau fibril assembly. Phenothiazines, porphyrins and polyphenols have been reported to block tau fibrillization as determined by ThT fluorescence and electron microscopic analysis of reaction products113. Another screen of ~51,000 compounds to identify inhibitors of heparin-induced fibrillization of a human 4-R tau fragment114 identified several active compounds, including previously described anthraquinones, phenothiazines, porphyrins and sulfonated dyes. In addition, novel benzofuran, pyrimidotriazine and quinoxaline inhibitors were discovered. Secondary analyses revealed that many of the compounds were inactive when dithiothreitol (DTT) was omitted from the tau assembly reaction, possibly because these compounds form peroxides in the presence of DTT that alter tau interaction. Among the compounds with less activity in the absence of DTT were the anthraquinones, benzofurans, porphyrins, pyrimidotriazines and sulfonated dyes, raising questions about the ultimate suitability of these molecules for use in vivo. The quinoxaline compounds did not depend on DTT for inhibition of tau fibril formation, and a bioinformatic analysis of the screening library revealed that only two of ~200 compounds containing a quinoxaline core structure were active in the tau assay. Both of these molecules contained a 2,3-di(furan-2yl) functionality that might be critical for activity. More recently, >290,000 compounds were screened at six concentrations with tau fibrillization monitored using fluorescence polarization (FP) and ThT fluorescence (Box 2). A total of 285 compounds showed complete dose-dependent inhibition of tau assembly, and a unique set of aminothienopyridazine inhibitors were identified that have drug-like physical-chemical attributes115.

In summary, several distinct classes of small molecule compounds have been identified that prevent tau fibrillization (Table 2) and some of these have also been shown to disaggregate pre-formed fibrils or block tau aggregate formation in cells. Many of the existing examples of tau assembly inhibitors have chemical or biological properties that will probably make them unsuitable for use in vivo, and at least some may act through the generation of reactive species or via covalent modification that increase the potential for off-target side-effects. Moreover, it is possible that certain of the described tau fibrillization inhibitors may form colloidal structures that have been shown to result in non-specific inhibition of amyloid polymerization116. Nonetheless, continued efforts in this area are likely to yield compounds that will be suitable for analysis in mouse models of tauopathy, which will be crucial in determining whether the strategy of inhibiting tau fibril formation has therapeutic merit. In particular, it will be important to show that tau assembly inhibitors can have the desired effect of reducing tau accumulations at doses that are safe. Many of the described compounds seem to require nearly equimolar concentrations relative to tau to block fibril formation in vitro, which might suggest that high concentrations would be required in the brain to achieve efficacy. However, it has been estimated that >99% of tau is bound to MTs117, and thus the free tau concentrations might be <20 nM in neurons based on an estimate of 2 μM total tau118. Under these circumstances, achieving equimolar drug concentrations should be achievable with reasonable doses.

Another factor to consider in the evaluation of tau assembly inhibitors is that there has been very little characterization of the tau species that accumulate in the presence of these compounds. Preferred compounds are likely to be those that prevent the initial stages of tau–tau interaction, so that they lead to an increase of tau monomers and not uncharacterized intermediate multimeric structures which could conceivably have biological activity119. Thus, an understanding of the tau species that are formed in the presence of assembly inhibitors will be important in interpreting results from studies conducted in animal models of tauopathy.

Enhancing intracellular Tau degradation

There are two major pathways by which cells can degrade misfolded cytosolic proteins. The first is the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) in which proteins are modified with ubiquitin tags and subsequently degraded by the proteasome complex120. This requires the threading of the targeted protein into a narrow opening formed by the proteasome, thereby excluding oligomers and larger aggregates from catabolism by this route. Larger multimeric protein structures are thus primarily degraded through macroautophagy, which requires encapsulation by an autophagosome and subsequent fusion with a hydrolase-containing lysosome121. There is evidence that both of these systems may be affected in the AD brain122-126, and although normal tau has not been shown to use these systems there are reports which suggest that hyperphosphorylated and misfolded tau can undergo degradation through both of these pathways. Accordingly, it is possible that upregulation of one or both of these catabolic systems may lead to a reduction of pathological tau in AD and other tauopathies.

The involvement of the UPS in the degradation of phosphorylated tau has been demonstrated through the use of inhibitors of the 90 kD heat shock protein (Hsp90). Hsp90 acts as a molecular chaperone that combines with other proteins to form a complex that assists in the refolding of denatured proteins in an ATP-dependent process. If the ATPase function of Hsp90 is inhibited with molecules such as geldanamycin, the composition of the refolding complexes can change such that proteins which were once stabilized by Hsp90 are targeted for degradation by the proteasome (see 127,128 for greater detail). Inhibitors of Hsp90 have been extensively studied as possible cancer therapies as it appears that many oncogenic proteins are stabilized through interactions with Hsp90. Several Hsp90 inhibitors reduced the levels of tau phosphorylated at proline-directed kinase sites Ser202/Thr205 and Ser396/Ser404 in cells overexpressing mutated human tau129. Moreover, tau with an altered conformation that is recognized by a specific antibody was found to be decreased in cells treated with Hsp90 inhibitors. Two studies have shown that treating transgenic mice that express human tau with BBB-permeable Hsp90 inhibitors (Table 1) — EC102 for seven days, or PU24FCl for one month — reduced the amount of hyperphosphorylated tau in the brain127,130.

Interestingly, EC102 was found to displace biotin-labeled geldanamycin from Hsp90 complexes within human AD cortical brain homogenates at 1000-fold lower concentration than from homogenates derived from control cortex or non-affected AD cerebellum127. This observation is in keeping with the discovery that the Hsp90 inhibitor 17-asllylaminogeldanamycin has 100-fold higher binding affinity for Hsp90 derived from tumour cells than from normal cells131. These data suggest that there is a preferential binding of Hsp90 inhibitors to complexes that are associated with misfolded proteins, and imply that Hsp90 inhibitors can be used clinically at doses that will leave other Hsp90–client protein interactions intact.

Although Hsp90 inhibitors seem to hold promise for reducing phosphorylated and misfolded monomeric tau through the UPS, it is unlikely that this pathway would affect larger tau oligomers and fibrils. However, the autophagic clearance system has been implicated in the removal of aggregate-prone proteins, including those involved in neurodegenerative disease121,132. Macroautophagy can be induced with the drug rapamycin, and it has been demonstrated that treatment of flies which express wild-type or mutated tau with this compound results in a reduction of insoluble tau and associated toxicity 133. Recently, it was found that clearance of tau was slowed in human tau-expressing neuroblastoma cells that were treated with the lysosomotropic agents NH4Cl or chloroquine 134. Furthermore, the addition of the autophagy inhibitor, 3-methyladenine, led to enhanced tau accumulation and aggregation 134. There is thus growing evidence that aggregated tau can be degraded by autophagy and that an up-regulation of the autophagy-lysosomal system with drugs like rapamycin might be a potential strategy for the treatment of tauopathies. Unfortunately, rapamycin affects the mTOR signalling network and has pleiotropic effects, including immunosuppression, that complicate its use. In this regard, inhibition of an mTOR-independent target, inositol monophosphatase, with LiCl has been shown to cause an upregulation of autophagy and an increased clearance α-synuclein, which forms intracellular inclusions in Parkinson's disease135. As previously discussed, many studies have been conducted with LiCl in tauopathy models in which changes in aggregated tau levels were attributed to inhibition of GSK-3. It is possible that LiCl might have also induced autophagy in these models, and it will be important to further study whether inositol monophosphatase inhibition affects tau aggregates in cell-based models and tau transgenic mice.

Conclusions

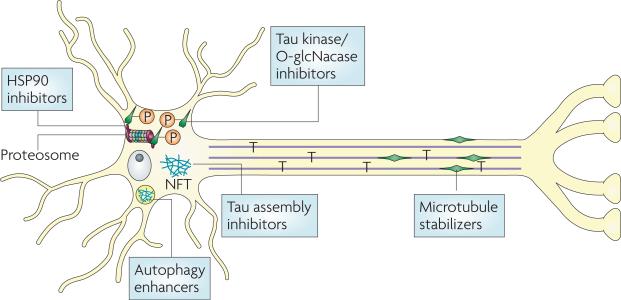

There clearly is growing interest in tau-focused drug discovery for AD and other tauopathies, and this has resulted in significant recent advancements in this area. Indeed, a number of small molecules have been identified that target tau-mediated neuropathology and neurodegeneration (Figure 4). These include compounds that inhibit tau multimerization, decrease tau phosphorylation through inhibition of kinases or O-GlcNacase, enhance tau degradation or compensate for tau LOF through stabilization of MTs. However, only a handful of tau kinase inhibitors, Hsp90 inhibitors and MT stabilizing agents have undergone proof-of-principle testing in established transgenic mouse models of tauopathy. Moreover, the only tau-directed drugs that have progressed to human clinical testing are methylene blue, LiCl and NAP. It is hoped that many additional compounds that target tau pathology will soon be examined for efficacy in vivo, as such studies are important in further validating the use of tau-based therapeutic approaches.

Figure 4. Therapeutic strategies to reduce Tau-mediated neuropathology and neurodegeneration.

A number of approaches are being pursued to reduce the consequences of pathological tau in Alzheimer's disease and related tauopathies. It is believed that tau deposition into neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) results in a loss of normal tau stabilization of microtubules (MTs) and/or the formation of toxic tau multimeric structures. A reduction of tau interaction with MTs might be compensated for by small molecule MT-stabilizing agents. Tau hyperphosphorylation reduces its binding to MTs and enhances its fibrillization, and inhibitors of tau kinases might thus improve both MT function and reduce the formation of pathologic tau multimers. Because tau O-glycosylation and phosphorylation seem to be reciprocally regulated, inhibition of O-GlcNacase might be another approach to decreasing tau hyperphosphorylation. Another potential strategy for increasing the amount of soluble tau available for MT binding and for decreasing potentially toxic aggregates is to inhibit the assembly of tau into larger multimeric structures or dissolve existing aggregates (tau assembly inhibitors). Finally, it may be possible to increase the degradation of misfolded and aggregated tau. Hsp90 inhibitors might increase proteasome-mediated clearance of misfolded and/or hyperphosphorylated tau monomers, whereas enhancers of autophagy have the potential to increase the removal of tau aggregates. For examples of compounds targeting these processes please see table 1.

As tau-directed therapies move toward clinical testing in AD and other tauopathies, they will face many of the same difficulties that are presently being encountered in trials of Aβ-targeted drugs. Foremost among these is the challenge of demonstrating clinical efficacy in a population that is likely to have substantial existing neurodegeneration. Efforts are underway to improve early AD diagnosis and to identify those with prodromal disease, as such patients should be more responsive to disease-modifying treatments. However, conducting clinical trials at an early disease stage presents other difficulties, including the possibility of having to follow patient response for longer time periods. This challenge might be mitigated by the identification of informative efficacy biomarkers for AD and related tauopathies. Although there is considerable uncertainty about the relative roles of Aβ and tau in AD, the greater correlation of memory impairment with NFTs than with Aβ-containing senile plaques suggests that tau pathology is temporally more proximal to the neurodegenerative events that result in dementia than are Aβ aggregates. If true, it may be easier to demonstrate clinical efficacy in AD with tau-directed drugs than with those targeting Aβ. It is thus very important that there be continued advancement of tau drug discovery programmes so that candidates are identified for future clinical assessment.

Box 1. Transgenic mouse models of tauopathy.

The assessment of compounds directed to potential tauopathy drug targets has been greatly facilitated by the development of transgenic mice that develop tau neuropathology as they age (reviewed in 1,92). In general, mice that have been genetically altered to overexpress human tau containing one or more mutations found in patients with frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) develop central nervous system inclusions comprised of hyperphosphorylated human tau. These intraneuronal aggregates resemble those observed in tauopathies, and many tau transgenic mice also show profound neuron loss. The regional expression profile of tau in these transgenic mice depends on the promoter that is used to drive tau expression, and thus certain transgenic lines show neuropathology that is largely restricted to the forebrain, whereas other lines have more broadly disseminated tau expression and pathology. Recently, transgenic mice have been developed in which mutated human tau expression can be regulated through the use of a repressible promoter 136, thereby facilitating studies examining the effects of temporal tau expression.

Box 2. Description of high-throughput screens used to identify Tau fibrillization inhibitors.

Full-length tau or certain tau fragments can be induced to form fibrils that closely resemble those isolated from diseased brains. Tau monomers have a highly disorganized structure and will not spontaneously assemble into fibrils unless an anionic co-factor such as heparin or arachidonic acid is included in the incubation mixture. When one of these anionic species is added to a tau preparation and incubated at 37°C, a time-dependent increase in fibril content is observed that can be detected with dyes such as Thioflavine S or T (ThT), which emit a characteristic fluorescence signal upon binding to cross-β-fibril structures (see figure)137. A alternative detection method involves mixing a small amount of fluorescently-labeled tau into the fibrillization assay115. The fluorescent tau is incorporated in growing tau multimers, which slows the rotational freedom of the fluorescent probe and causes an increase in fluorescence polarization (FP) (depicted below). Whereas ThT will only bind tau fibrils, the FP method allows for the detection of both non-fibrillar and fibrillar multimeric tau species and the FP and ThT readouts can be performed in the same reaction. Combining both of these methods in one assay can help to distinguish compounds that inhibit the earliest stages of tau assembly (resulting in a diminution of both FP and ThT fluorescence) from those that primarily affect fibril growth (leading to diminished ThT fluorescence but relatively unchanged FP). Tau fibrillization assays of this type have been miniaturized so that fibrils can be reproducibly formed in 384- or 1536-well plates, thereby allowing large compound libraries to be screened for molecules that inhibit tau fibril formation.

Online bits:

At a Glance

-

-

A number of neurodegenerative diseases of the brain are characterized by the presence of inclusions within neurons that are comprised of aggregated fibrils of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. These various disorders, which include Alzheimer's disease (AD), Pick's disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration and certain frontotemporal dementias, are broadly referred to as tauopathies.

-

-

Tau is normally a soluble protein that stabilizes microtubules (MTs) within cells and is particularly enriched in neurons, where MTs serve as the “tracks” upon which cellular cargo is transported in axonal projections. The formation of insoluble tau aggregates could cause neurodegeneration through the formation of toxic tau species, or through a loss of tau function due to its hyperphosphorylation and sequestration in inclusions.

-

-

Tau mutations have been shown to cause frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17), but tau mutations have not been identified in other tauopathies, including AD. The causes of tau aggregation in these sporadic tauopathies are not fully understood, although tau hyperphosphorylation might be important as it decreases tau binding to MTs and increases tau fibrillization.

-

-

There is a growing interest in developing therapeutics that target pathological tau, particularly for the treatment of AD. Most tau-directed drug discovery programmes are in early research stages and are not as advanced as programmes that aim to decrease levels of the amyloid β peptides which form senile plaques in the AD brain.

-

-

A number of approaches are being pursued for the treatment of tauopathies, including the development of brain-penetrant compounds that can 1) stabilize MTs and thus compensate for tau loss-of-function; 2) reduce tau hyperphosphorylation; 3) inhibit tau assembly into oligomers and fibrils; or 4) enhance tau intracellular degradative pathways.

-

-

As tau-directed therapies move toward clinical testing in AD and other tauopathies, they will face many of the difficulties that are presently being encountered in trials of Aβ-targeted AD drugs. These include drug safety and the challenge of demonstrating clinical efficacy in a population that is likely to have existing neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleagues for their contributions to the work summarized here which has been supported by grants from the NIH (P01 AG09215, P30 AG10124, P01 AG11542, P01 AG14382, P01 AG14449, P01 AG17586, PO1 AG19724, P01 NS-044233, UO1 AG24904), and the Marian S. Ware Alzheimer Program. Finally, we are indebted to our patients and their families whose commitment to research has made our work possible.

Glossary

- Dendrites

a branched extension of a neuron that interacts with adjacent cells and transmits electrical impulses.

- Fast Axonal Transport

a mechanism whereby intracellular organelles are transported along microtubules at a rate of ~400 mm/day.

- Microtubule-stabilizing drug

typically molecules, such as paclitaxel or epothilones, that were identified from natural products and which bind with high affinity to microtubules, thereby affecting microtubule dynamics. Compounds of this type have been used for the treatment of cancer because they affect mitotic spindles and induce death in rapidly dividing cells.

- Pseudophosphorylation

the effects of serine (ser) or threonine (thr) phosphorylation can be mimicked in part by substitution of the phosphorylated ser/thr residues within a protein with aspartic acid or glutamic acid residues. These amino acids, like phosphorylated ser or thr, carry a negative charge at physiological pH.

- Cross-β-Fibril

a fibril composed of repeating units enriched in β-sheets that align parallel to the fibril axis with their β-strands perpendicular to this axis.

- Macroautophagy

a process whereby a double-membrane structure encapsulates cytosolic material and later fuses with lysosomes, resulting in degradation of the sequestered matter.

- Lysosomotropic Agent

a molecule that enters the lysosomes and alters its function, often by increasing the pH of this normally acidic organelle.

- Prodromal Disease

the earliest phase of a developing condition or disease.

Biographies

Dr. Kurt R. Brunden obtained his PhD in Biochemistry from Purdue University in 1985. He then worked as a post-doctoral fellow at the Mayo Clinic before joining the Biochemistry faculty at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in 1988, with a research focus on the regulation of myelination. He was recruited to the biotechnology sector in 1991, served as VP of Research at Gliatech, Inc. and Sr. VP of Drug Discovery at Athersys, Inc, where he initiated and managed drug discovery programmes in Alzheimer's disease, cognition, schizophrenia, obesity, asthma and inflammation. In 2007, Brunden became Director of Drug Discovery in the Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. J.Q.Trojanowski obtained his MD/PhD in 1976 from Tufts, and after training at Harvard and Penn, he joined the Penn faculty in 1981 where he is Professor, and directs the NIA Alzheimer's Center, the NINDS Udall Parkinson's Center and the Institute on Aging. His research focuses on neurodegenerative diseases. He was elected to the Institute of Medicine in 2002. He has also led an effort to prepare a 2009 PBS film entitled “Alzheimer's Disease-Facing the Facts” that won a CINE “Golden Eagle Award”.

Dr. Virginia M.-Y. Lee, obtained her PhD in Biochemistry from the University of California San Francisco in 1973. She also holds an MBA from the Wharton School (1984) and an MS in Biochemistry from the University of London (1968). She is now [AU: ok?] John H. Ware 3rd Professor in Alzheimer's Research; Director, Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research; Co-director, Marian S. Ware Alzheimer Drug Discovery Program, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Her research focuses on the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, frontotemporal dementias and related neurodegenerative disorders.

Reference List

- 1.Ballatore C, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8:663–672. doi: 10.1038/nrn2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee VMY, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidd M. Paired Helical Filaments in Electron Microscopy of Alzheimers Disease. Nature. 1963;197:192. doi: 10.1038/197192b0. [First description of PHFs in AD neurofibrillary tangles at the EM level] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedleywhyte ET, Hyman BT. Neurofibrillary Tangles But Not Senile Plaques Parallel Duration and Severity of Alzheimers-Disease. Neurology. 1992;42:631–639. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.631. [Showed that tangles not plaques correlate with dementia severity in AD] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilcock GK, Esiri MM. Plaques, Tangles and Dementia - A Quantitative Study. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1982;56:343–356. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(82)90155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomezlsla T, et al. Neuronal loss correlates with but exceeds neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Annals of Neurology. 1997;41:17–24. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.George-Hyslop PH, Petit A. Molecular biology and genetics of Alzheimer's disease. C R. Biol. 2005;328:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selkoe DJ, Schenk D. Alzheimer's disease: Molecular understanding predicts amyloid-based therapeutics. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2003;43:545–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.140248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goedert M. Tau gene mutations and their effects. Movement Disorders. 2005;20:S45–S52. doi: 10.1002/mds.20539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goedert M, Jakes R. Mutations causing neurodegenerative tauopathies. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Molecular Basis of Disease. 2005;1739:240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.08.007. [Good review of tau mutations associated with neurodegenerative disease] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandt R, Hundelt M, Shahani N. Tau alteration and neuronal degeneration in tauopathies: mechanisms and models. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Molecular Basis of Disease. 2005;1739:331–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. Medicine - The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drechsel DN, Hyman AA, Cobb MH, Kirschner MW. Modulation of the Dynamic Instability of Tubulin Assembly by the Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1992;3:1141–1154. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.10.1141. [One of the earliest studies to define tau functions in MT assembly/stability] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gustke N, Trinczek B, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Domains of Tau-Protein and Interactions with Microtubules. Biochemistry. 1994;33:9511–9522. doi: 10.1021/bi00198a017. [Defined domains in tau that interact with MTs] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binder LI, Frankfurter A, Rebhun LI. The Distribution of Tau in the Mammalian Central Nervous-System. Journal of Cell Biology. 1985;101:1371–1378. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1371. [First description of the distribution of tau in CNS cells] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andreadis A, Brown WM, Kosik KS. Structure and Novel Exons of the Human-Tau Gene. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10626–10633. doi: 10.1021/bi00158a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA. Multiple Isoforms of Human Microtubule-Associated Protein-Tau - Sequences and Localization in Neurofibrillary Tangles of Alzheimers-Disease. Neuron. 1989;3:519–526. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panda D, Samuel JC, Massie M, Feinstein SC, Wilson L. Differential regulation of microtubule dynamics by three- and four-repeat tau: Implications for the onset of neurodegenerative disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:9548–9553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633508100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spillantini MG, et al. Familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia: A disease with abundant neuronal and glial tau filaments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:4113–4118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dayanandan R, et al. Mutations in tau reduce its microtubule binding properties in intact cells and affect its phosphorylation. Febs Letters. 1999;446:228–232. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasegawa M, Smith MJ, Goedert M. Tau proteins with FTDP-17 mutations have a reduced ability to promote microtubule assembly. Febs Letters. 1998;437:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong M, et al. Mutation-specific functional impairments in distinct Tau isoforms of hereditary FTDP-17. Science. 1998;282:1914–1917. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1914. [Described gains and losses of tau functions caused by authentic FTDP-17 tau gene mutations] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barghorn S, et al. Structure, microtubule interactions, and paired helical filament aggregation by tau mutants of frontotemporal dementias. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11714–11721. doi: 10.1021/bi000850r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gamblin TC, et al. In vitro polymerization of tau protein monitored by laser light scattering: Method and application to the study of FTDP-17 mutants. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6136–6144. doi: 10.1021/bi000201f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nacharaju P, et al. Accelerated filament formation from tau protein with specific FTDP-17 missense mutations. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1999;58:545. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avila J, Santa-Maria I, Perez M, Hernandez F, Moreno F. Tau phosphorylation, aggregation, and cell toxicity. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2006 doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/74539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avila J. Tau and tauopathies: tau phosphorylation and tau assembly. Febs Journal. 2006;273:23. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buee L, Bussiere T, Buee-Scherrer V, Delacourte A, Hof PR. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Research Reviews. 2000;33:95–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merrick SE, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY. Selective destruction of stable microtubules and axons by inhibitors of protein serine/threonine phosphatases in cultured human neurons (NT2N cells). Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:5726–5737. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05726.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner U, Utton M, Gallo JM, Miller CCJ. Cellular phosphorylation of tau by GSK-3 beta influences tau binding to microtubules and microtubule organisation. Journal of Cell Science. 1996;109:1537–1543. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alonso AD, GrundkeIqbal I, Iqbal K. Alzheimer's disease hyperphosphorylated tau sequesters normal tau into tangles of filaments and disassembles microtubules. Nature Medicine. 1996;2:783–787. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alonso AD, GrundkeIqbal I, Iqbal K. Abnormally Phosphorylated-Tau from Alzheimer-Disease Brain Depolymerizes Microtubules. Neurobiology of Aging. 1994;15:S37. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Necula M, Kuret J. Pseudophosphorylation and glycation of tau protein enhance but do not trigger fibrillization in vitro. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:49694–49703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kins S, et al. Reduced protein phosphatase 2A activity induces hyperphosphorylation and altered compartmentalization of tau in transgenic mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:38193–38200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu F, Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I, Hart GW, Gong CX. O-GlcNAcylation regulates phosphorylation of tau: A mechanism involved in Alzheimer's disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:10804–10809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400348101. [Describes a potential alternative strategy to reduce tau hyperphosphorylation] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lefebvre T, et al. Evidence of a balance between phosphorylation and O-GlcNAc glycosylation of Tau proteins - a role in nuclear localization. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-General Subjects. 2003;1619:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee G, et al. Phosphorylation of tau by fyn: Implications for Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:2304–2312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4162-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gong CX, Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Post-translational modifications of tau protein in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2005;112:813–838. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park SY, Ferreira A. The generation of a 17 kDa neurotoxic fragment: An alternative mechanism by which tau mediates beta-amyloid-induced neurodegeneration. Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25:5365–5375. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1125-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gamblin TC, et al. Caspase cleavage of tau: Linking amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:10032–10037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1630428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chirita CN, Necula M, Kuret J. Anionic micelles and vesicles induce tau fibrillization in vitro. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:25644–25650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson DM, Binder LI. Free fatty acids stimulate the polymerization of tau and amyloid beta peptides - In vitro evidence for a common effector of pathogenesis in Alzheimer's disease. American Journal of Pathology. 1997;150:2181–2195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gauthier S, et al. Effect of tramiprosate in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: exploratory analyses of the MRI sub-group of the Alphase study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13:550–557. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green RC, Schneider LS, Hendrix S, Zavitz K, Swabb E. Safety and efficacy of tarenflurbil in subjects with mild Alzheimer's disease: results from an 18 month multicenter phase 3 trial Late breaking news. European Journal of Neurology. 2008;15:412. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hempen B, Brion JP. Reduction of acetylated alpha-tubulin immunoreactivity in neurofibrillary tangle-bearing neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1996;55:964–972. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bendiske J, Caba E, Brown QB, Bahr BA. Intracellular deposition, microtubule destabilization, and transport failure: An “early” pathogenic cascade leading to synaptic decline. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2002;61:640–650. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.7.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ishihara T, et al. Age-dependent emergence and progression of a tauopathy in transgenic mice overexpressing the shortest human tau isoform. Neuron. 1999;24:751–762. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cash AD, et al. Microtubule reduction in Alzheimer's disease and aging is independent of tau filament formation. American Journal of Pathology. 2003;162:1623–1627. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64296-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan A, Kumar A, Peterhoff C, Duff K, Nixon RA. Axonal transport rates in vivo are unaffected by tau deletion or overexpression in mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:1682–1687. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5242-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roberson ED, et al. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid beta-induced deficits in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316:750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harada A, et al. Altered Microtubule Organization in Small-Caliber Axons of Mice Lacking Tau-Protein. Nature. 1994;369:488–491. doi: 10.1038/369488a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dawson HN, et al. Inhibition of neuronal maturation in primary hippocampal neurons from tau deficient mice. Journal of Cell Science. 2001;114:1179–1187. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.6.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ikegami S, Harada A, Hirokawa N. Muscle weakness, hyperactivity, and impairment in fear conditioning in tau-deficient mice. Neuroscience Letters. 2000;279:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00964-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang B, et al. Microtubule-binding drugs offset tau sequestration by stabilizing microtubules and reversing fast axonal transport deficits in a tauopathy model. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:227–231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406361102. [Provided evidence that tau loss-of-function could be compensated for by a small molecule microtubule stabilizer] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gozes I, Divinski I. The femtomolar-acting NAP interacts with microtubules: Novel aspects of astrocyte protection. Journal of Alzheimers Disease. 2004;6:S37–S41. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6s605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsuoka Y, et al. Intranasal NAP administration reduces accumulation of amyloid peptide and tau hyperphosphorylation in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease at early pathological stage. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2007;31:165–170. doi: 10.1385/jmn/31:02:165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matsuoka Y, et al. A neuronal microtubule-interacting agent, NAPVSIPQ, reduces tau pathology and enhances cognitive function in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2008;325:146–153. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.130526. [Proof-of-concept study of NAP in a transgenic mouse model of AD pathology, and NAP is the first putative MT-stabilizing drug to enter a clinical trial] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ballatore C, et al. Paclitaxel C-10 carbamates: Potential candidates for the treatment of neurodegenerative tauopathies. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2007;17:3642–3646. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.04.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fellner S, et al. Transport of paclitaxel (Taxol) across the blood-brain barrier in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;110:1309–1318. doi: 10.1172/JCI15451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matsuo ES, et al. Biopsy-Derived Adult Human Brain Tau Is Phosphorylated at Many of the Same Sites As Alzheimers-Disease Paired Helical Filament-Tau. Neuron. 1994;13:989–1002. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90264-x. [Showed that nearly all phosphorylation sites in PHFtau also exist in normal tau isolated from rapidly processed human cortical biopsies, thereby establishing that the abnormal phosphorylation in PHFtau is defined by quantitative rather than qualitative differences with normal tau] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hasegawa M, et al. Protein-Sequence and Mass-Spectrometric Analyses of Tau in the Alzheimers-Disease Brain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:17047–17054. [Extensively mapped PHFtau phosphorylation sites] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hanger DP, Anderton BH, Noble W. Tau phosphorylation: the therapeutic challenge for neurodegenerative disease. Trends Molecular Medicine. 2009;15:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sengupta A, et al. Phosphorylation of tau at both Thr 231 and Ser 262 is required for maximal inhibition of its binding to microtubules. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1998;357:299–309. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alonso AD, Mederlyova A, Novak M, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Promotion of hyperphosphorylation by frontotemporal dementia tau mutations. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:34873–34881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405131200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schneider A, Biernat J, von Bergen M, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Phosphorylation that detaches tau from microtubules S262 and S214 protects it against aggregation into Alzheimer paired helical filaments. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;73:S26. doi: 10.1021/bi981874p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O'Shea JJ. Selectivity and therapeutic inhibition of kinases: to be or not to be? Nature Immunology. 2009;10:356–360. doi: 10.1038/ni.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mazanetz MP, Fischer PM. Untangling tau hyperphosphorylation in drug design for neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2007;6:464–479. doi: 10.1038/nrd2111. [Excellent review on medicinal chemistry efforts to develop tau kinase inhibitors] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gong CX, Iqbal K. Hyperphosphorylation of Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau: A Promising Therapeutic Target for Alzheimer Disease. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;15:2321–2328. doi: 10.2174/092986708785909111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Imahori K, Uchida T. Physiology and pathology of tau protein kinases in relation to Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Biochemistry. 1997;121:179–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pei JJ, et al. Distribution, levels, and activity of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the Alzheimer disease brain. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1997;56:70–78. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lucas JJ, et al. Decreased nuclear beta-catenin, tau hyperphosphorylation and neurodegeneration in GSK-3 beta conditional transgenic mice. Embo Journal. 2001;20:27–39. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hernandez F, Borrell J, Guaza C, Avila J, Lucas JJ. Spatial learning deficit in transgenic mice that conditionally over-express GSK-3 beta in the brain but do not form tau filaments. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;83:1529–1533. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee KY, et al. Elevated neuronal Cdc2-like kinase activity in the Alzheimer disease brain. Neuroscience Research. 1999;34:21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(99)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tseng HC, Zhou Y, Shen Y, Tsai LH. A survey of Cdk5 activator p35 and p25 levels in Alzheimer's disease brains. Febs Letters. 2002;523:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02934-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yamaguchi H, et al. Preferential labeling of Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles with antisera for tau protein kinase (TPK)I glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta and cyclin-dependent kinase 5, a component of TPK II. Acta Neuropathologica. 1996;92:232–241. doi: 10.1007/s004010050513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Augustinack JC, Sanders JL, Tsai LH, Hyman BT. Colocalization and fluorescence resonance energy transfer between cdk5 and AT8 suggests a close association in pre-neurofibrillary tangles and neurofibrillary tangles. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2002;61:557–564. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.6.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pei JJ, et al. Accumulation of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (cdk5) in neurons with early stages of Alzheimer's disease neurofibrillary degeneration. Brain Research. 1998;797:267–277. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Noble W, et al. Cdk5 is a key factor in tau aggregation and tangle formation in vivo. Neuron. 2003;38:555–565. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cruz JC, et al. P25/cyclin-dependent kinase 5 induces production and intraneuronal accumulation of amyloid beta in vivo. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:10536–10541. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3133-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Phiel CJ, Wilson CA, Lee VMY, Klein PS. GSK-3 alpha regulates production of Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta peptides. Nature. 2003;423:435–439. doi: 10.1038/nature01640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aplin AE, Jacobsen JS, Anderton BH, Gallo JM. Effect of increased glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity upon the maturation of the amyloid precursor protein in transfected cells. Neuroreport. 1997;8:639–643. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199702100-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rockenstein E, et al. Neuroprotective effects of regulators of the glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta signaling pathway in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease are associated with reduced amyloid precursor protein phosphorylation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:1981–1991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4321-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wen Y, et al. Interplay between cyclin-dependent kinase 5 and glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta mediated by neuregulin signaling leads to differential effects on tau phosphorylation and amyloid precursor protein processing. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:2624–2632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5245-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Drewes G, Ebneth A, Preuss U, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. MARK, a novel family of protein kinases that phosphorylate microtubule-associated proteins and trigger microtubule disruption. Cell. 1997;89:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80208-1. [Defined MARK as a significant kinase that phosphorylates tau] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chin JY, et al. Microtubule-affinity regulating kinase (MARK) is tightly associated with neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer brain: A fluorescence resonance energy transfer study. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2000;59:966–971. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.11.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nishimura I, Yang YF, Lu BW. PAR-1 kinase plays an initiator role in a temporally ordered phosphorylation process that confers tau toxicity in Drosophila. Cell. 2004;116:671–682. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Medina M, Castro A. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) inhibitors reach the clinic. Current Opinion in Drug Discovery & Development. 2008;11:533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dhavan R, Tsai LH. A decade of CDK5. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2001;2:749–759. doi: 10.1038/35096019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Biernat J, et al. Protein kinase MARK/PAR-1 is required for neurite outgrowth and establishment of neuronal polarity. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2002;13:4013–4028. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-03-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mandelkow EM, Thies E, Trinczek B, Biernat J, Mandelkow E. MARK/PAR1 kinase is a regulator of microtubuledependent transport in axons. Journal of Cell Biology. 2004;167:99–110. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Churcher I. Tau therapeutic strategies for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;6:579–595. doi: 10.2174/156802606776743057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee VMY, Kenyon TK, Trojanowski JQ. Transgenic animal models of tauopathies. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Molecular Basis of Disease. 2005;1739:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Noble W, et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by lithium correlates with reduced tauopathy and degeneration in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:6990–6995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500466102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Perez M, Hernandez F, Lim F, Diaz-Nido J, Avila J. Chronic lithium treatment decreases mutant tau protein aggregation in a transgenic mouse model. J. Alzheimer's Disease. 2003;5:301–308. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nakashima H, et al. Effect of chronic lithium treatment on an animal model of tauopathies. Neurobiology of Aging. 2004;25:S595. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Engel T, Goni-Oliver P, Lucas JJ, Avila J, Hernandez F. Chronic lithium administration to FTDP-17 tau and GSK-3 beta overexpressing mice prevents tau hyperphosphorylation and neurofibrillary tangle formation, but pre-formed neurofibrillary tangles do not revert. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2006;99:1445–1455. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Caccamo A, Oddo S, Tran LX, LaFerla FM. Lithium reduces tau phosphorylation but not A beta or working memory deficits in a transgenic model with both plaques and tangles. American Journal of Pathology. 2007;170:1669–1675. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hampel H, et al. Lithium trial in Alzheimer's disease: a randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter 10-week study. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2009 In press. [Describes a clinical trial, albeit small, that failed to demonstrate significant ameliorative effects of lithium therapy] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Le Corre S, et al. An inhibitor of tau hyperphosphorylation prevents severe motor impairments in tau transgenic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602913103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Selenica ML, et al. Efficacy of small-molecule glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitors in the postnatal rat model of tau hyperphosphorylation. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2007;152:959–979. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fischer PM. Turning down tau phosphorylation. Nature Chemical Biology. 2008;4:448–449. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0808-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yuzwa SA, et al. A potent mechanism-inspired O-GlcNAcase inhibitor that blocks phosphorylation of tau in vivo. Nature Chemical Biology. 2008;4:483–490. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hasegawa M, Crowther RA, Jakes B, Goedert M. Alzheimer-like changes in microtubule-associated protein tau induced by sulfated glycosaminoglycans - Inhibition of microtubule binding, stimulation of phosphorylation, and filament assembly depend on the degree of sulfation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:33118–33124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wischik CM, Edwards PC, Lai RYK, Roth M, Harrington CR. Selective inhibition of Alzheimer disease-like tau aggregation by phenothiazines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:11213–11218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11213. [One of the earliest in vitro studies of compounds that inhibit tau aggregation] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Staff RT, et al. Tau aggregation inhibitor (TAI) therapy with rember arrests the trajectory of rCBF decline in brain regions affected by tau pathology in mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's and Dementia. 2008;4:T775. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chirita C, Necula M, Kuret J. Ligand-dependent inhibition and reversal of tau filament formation. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2879–2887. doi: 10.1021/bi036094h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Congdon EE, Necula M, Blackstone RD, Kuret J. Potency of a tar fibrillization inhibitor is influenced by its aggregation state. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2007;465:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]