Abstract

Identification of transplanted human cells in mouse models is important for studying the biology and therapeutic potential of stem/progenitor cells. As stem/progenitor cells are often transplanted in low numbers, detection of cell engraftment requires sensitive tools. Single copy genes, as well as repetitive genetic elements have been developed for molecular detection of transplanted cells. We examined whether human sequences in chimeric mice could be measured with quantitative real-time polymerase chain reactions for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, type 1 repeat element, sex-determining region Y, or short tandem repeats across human leukocyte antigen regions, which are distinct from rodent genomes. We found that specific probes for all three candidate approaches successfully identified presence of human cells in mixtures of human and mouse genomes. However, probes for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease element or short tandem repeats for human leukocyte antigen regions were less effective for low numbers of transplanted human stem/progenitor cells in mice than human sex determining region on Y chromosome. None of the approaches could identify transplanted human cells constituting less than one percent of the total cell mass. This required localization of transplanted cells in tissue sections with human-specific in situ hybridization probes. Therefore, quantitative assays with single copy gene sequences, short tandem repeats or sex determining region will be helpful for demonstrating organ repopulation, although initial lower frequency engraftment of human cells in chimeric mice will be most effectively demonstrated by complementary tools, such as in situ localization of human cells in tissues.

Keywords: Cell Transplantation, Detection, Human, Mouse, Stem cells

INTRODUCTION

Transplantation of cells in animals is necessary for generating insights in stem cell biology and developing cell therapy applications. Cells generated from embryonic or fetal stem cells and from other types of stem cells are of increasing interest for these purposes (1). As the efficiency by which stem/progenitor cells may generate mature tissue cells is variable, and the fate of cells in vitro may be different from that in vivo (2), systematic cell transplantation studies are required with candidate cell populations. This makes identification of human cells in chimeric animals a critical need for stem cell research. While exogenous labeling of transplanted cells is convenient for some applications (3), leaching or reuptake of exogenous labels generally limits long-term studies. Similarly, marking of cells with reporter transgenes may produce genetic perturbations of unknown significance, particularly in stem/progenitor cells, and could induce deleterious host immune responses leading to clearance of transplanted cells with additional mechanisms. These confounding issues could be avoided by developing unique endogenous markers as probes for human cells in chimeric animals, e.g., fluorescent in situ hybridization for human-specific chromosome or centromere sequences has been useful (4,5). On the other hand, as the number of stem cells is often limited, and transplanted cells engraft in only small numbers, it will be helpful if sensitive assays were available to screen tissues for transplanted cells before in-depth tissue analyses. Moreover, such assays will be helpful for studies aimed at improving engraftment and proliferation of transplanted cells.

Recently, human-specific DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) probes have been used for identifying transplanted cells, e.g., intronic Alu repeats, sex-determining region on Y (SRY) or Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, type 1A repeat element (CMT1A) (5–7). However, measurement of transplanted cells by Alu repeats is confounded by its extensive representation in the genome, and SRY identifies only male cells, whereas the CMT1A probe is able to identify all types of human cells and offers the possibility of correlations between transplanted cell numbers and gene copies. Similarly, PCR assays with variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) were effective as genetic markers to measure engraftment of donor bone marrow cells in allogeneic recipients (8), although their limitations in distinguishing only some donor-recipient combinations led to short tandem repeats (STRs) as an attractive alternative (8). STRs are highly polymorphic and their location across human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and flanking regions offers excellent opportunities for developing genome-specific signatures for additional applications in cell transplantation research. Recently, a large panel of HLA-specific STRs characterized by tri-, tetra- and pentanucleotide repeats was developed for preimplantation genetic diagnosis of HLA identity with PCR-based approaches (9). These probes were superior to dinucleotide repeats and provided unambiguous ways to identify individual genotypes in single cell samples. Here, we defined the efficacy of these multiple probes for identifying human stem/progenitor cells in chimeric mice. Although the probes had been used individually to identify transplanted human cells, their sensitivity relative to one another had not previously been defined. Moreover, we identified transplanted human cells in mouse tissues with in situ hybridization for highly conserved primate alphoid satellite sequences that are ubiquitously distributed in all centrromeres of every cell, irrespective of gender or HLA haplotype, and are absent in rodents (10). We studied well-characterized human fetal stem/progenitor cells, which exhbit multilineage differentiation potential, extensive replication capacity, as well as ability to engraft in the liver of xenotolerant natural onset diabetes (NOD) mice in the severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) background (2).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fetal human tissue

Livers or pancreas of 18–20 week gestation were obtained from Human Fetal Tissue Repository at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Tissues were provided in an anonymous fashion and the Repository documented informed consent from donors. The Committee on Clinical Investigations (institutional review board) approved the procedures.

Animals

Male NOD-CB17-prkdcSCID mice of 10–12 weeks age were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were maintained under barrier conditions in the Institute for Animal Studies at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. The Animal Care and Use Committee at Einstein approved the studies.

Isolation and transplantation of human fetal cells

Liver or pancreas was dissociated as previously described (2). Dispersed cells were passed through 80 μm dacron mesh, pelleted under 350×g for 5 min at 4°C, and resuspended in Dulbecco’s Minimal Eagle’s Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cell numbers were determined manually in a Neubauer hemocytometer. Freshly isolated 0.5×106 to 5×106 human fetal cells were transplanted via the portal vein into NOD/SCID mice, as previously described (2). In some studies, fetal pancreas cells were used that had been immunomagnetically sorted for epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), as described (2), and were further modified by introducing the catalytic subunit of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) with a retrovirus construct described previously (11). The properties of hTERT-expanded fetal human liver cells included their capacity to transdifferentiate into insulin-expressing cells under appropriate context of genetic modification (12). These cells exhibited a conjoint meso-endodermal phenotype, which constituted a signature of stem/progenitor properties in epithelial fetal human liver cells with capacity to produce hepatic, bone, cartilage and adipocyte lineages (2). Similarly, hTERT-modified epithelial pancreatic fetal cells displayed conjoint meso-endodermal properties and expressed multilineage genes, including insulin, glucagon, mesenchymal and stem cell genes.

After cell transplantation, liver samples were collected at intervals of 24 h and 1, 2 and 4 weeks for DNA extraction and other studies (n=3–4 each).

Real-time qPCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from human fetal liver and mouse liver with DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time qPCR was done with LightCycler 2 System (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR reactions were in total volume of 25 μl with 2.5 μl of PCR buffer, 5 μl of 25 mM MgCl2 solution, 0.75 μl of 10 mM dNTP, 0.125 μl of AmpliTaq Gold (PE Applied Biosystems), 1 μl of each primer (10 pM) and 100 ng of DNA. Primers were based on sequences of human SRY, CMT1 and HLA-A STRs (Table 1). We selected two STRs for this study after initial studies of donor tissues and cells with a total of five STR probes. Mouse glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) primers were used to verify the integrity of mouse DNA. PCR was performed with denaturation at 95°C × 15 s and annealing at 55°C × 1 min. DNA mixing curves were prepared from male human samples and mouse DNAs. To decrease intratest variability at very low concentrations of DNA, four samples were used for each dilution in standard curves and at least four replicate samples were examined for all test conditions.

Table 1.

Primers for Real-Time PCR

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Tm (°C) | Product size (bp) | Reference number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human SRY | 5′-AGTTTCGCATTCTGGGA TTCTCT-3′ | 5′-GCGACCCATGAACGCA TT-3′ | 60 | 100 | Ref 7 |

| Human CMT1A | 5′-GAAATTCATTTAAAAGCA TTTTAAC-3′ | 5′-GCTAATAGTCATGTTTA AAATCATTTT -3′ | 55 | 345 | Current authors |

| Human HLA-A 39B | 5′-CCAAGAAAGAAAGAACC AATAGCA-3′ | 5′-GAGCCAATTAGCCCAA TAAATCAC-3′ | 60 | 176 | Ref 9 |

| Human HLA-A 54 | 5′-GCTCAGTTCCAGTTGCT TG-3′ | 5′-GCAGTGAGCCAAGATT GCAC-3′ | 60 | 215 | Ref 9 |

| Mouse GAPDH | 5′-GGGTGGAGCCAAACGG GTC-3′ | 5′-GGAGTTGCTGTTGAAG TCGCA -3′ | 56 | 550 | Ref 3 |

In situ hybridization

The pancentromeric alphoid satellite probe for human sequences was generated and used for in situ hybridization as described previously (5). To visualize hybridization signals, slides were incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C with 80–100 μl peroxidase-conjugated anti-Digoxigenin (1:50, Roche Life Sciences, Indianapolis, IN) and color was developed over 20 min with diaminobenzidine. Tissue sections were counterstained with toluidine blue before light microscopic examinations.

Statistical methods

Data were analyzed by Excel spreadsheet-based statistical package (Microsoft Corp., Seattle, WA) and linear regression was used to correlate significances.

RESULTS

Sensitivity of qPCR probes for human cells in mice

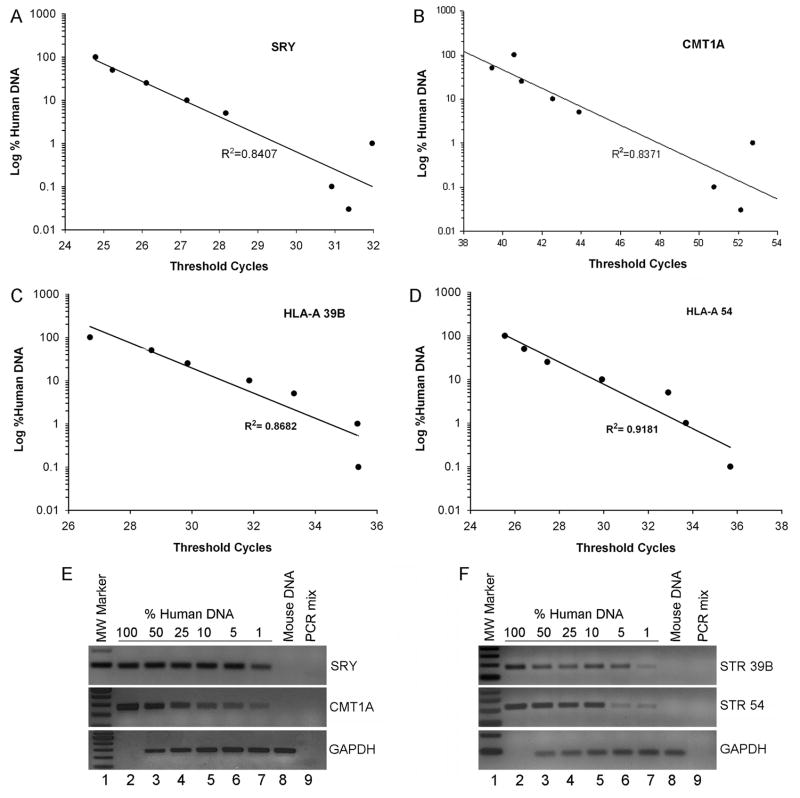

To first establish the limits of various PCR probes, we performed qPCR with genomic DNA from mouse and human livers. To compare data with qPCR for SRY, samples were from males. We combined human and mouse DNAs in a series of ratios to obtain samples with human DNA content ranging from 0.01% to 100%. These DNA samples were subjected to qPCR with threshold cycle analysis for establishing the sensitivity of CMT1A, STR and SRY probes (Fig. 1a – 1d). Moreover, PCR end-products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis to document single bands of anticipated sizes (Fig. 1d and 1f). These studies verified that CMT1A, STR and SRY probes amplified human DNAs and not mouse DNAs. Also, linear relationships emerged between threshold PCR cycles and human DNA in samples, verifying that qPCR conditions were appropriate.

Figure 1. qPCR validation of SRY and CMT1A probes in DNA mixing studies.

Male human DNA was mixed with mouse DNA to generate samples containing 0.01% to 100%. Panels A – D show inverse linear relationships between threshold cycle and log of human DNA concentration in human-mouse DNA mixtures with SRY (Panel A; R2=0.84), CMT1A (Panel B; R2= 0.87), STR 38B and STR 54 (Panels C and D, R2= 0.87 and R2= 0.92, respectively). Panels in E and F show end-point PCR products after qPCR for SRY, CMTA1 and STRs, along with mouse GAPDH, which was expected to be absent in human DNA. Lane1, molecular weight marker; lane2, human DNA only; lanes3–7, mixtures of human DNA in concentrations indicated with mouse DNA; lane 8, mouse DNA alone; lane 9, PCR mix alone as negative control.

We found that the SRY PCR probe detected up to 0.03% of human DNA in mixtures of human and mouse samples (Table 2). By contrast, qPCR for STR probes was less sensitive. CMT1A probe required far more PCR cycles than other probes at all levels of human DNA content. As STR probes did not amplify human genomes in mixtures containing 0.03% human DNA despite 40 PCR cycles, which was much greater than the corresponding 31.4 cycles needed for the SRY probe, we did not pursue further amplifications with STR probes. The findings were in agreement with lower representation of CMT1A in genomic DNA compared with that of SRY and STRs, and suggested that single gene probes will be least sensitive for detecting transplanted cells in animal tissues.

Table 2.

qPCR Threshold Cycles

| Human DNA content of samples (% of 100 ng total) | Threshold qPCR cycles for detecting human DNA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRY | CMT1A | HLA-A 39B | HLA-A 54 | |

| 100 | 24.79 | 40.59 | 26.70 | 25.55 |

| 50 | 25.23 | 39.46 | 29.86 | 26.42 |

| 25 | 26.11 | 40.97 | 28.69 | 27.46 |

| 10 | 27.16 | 42.55 | 31.86 | 29.92 |

| 5 | 28.17 | 43.90 | 33.31 | 32.90 |

| 1 | 31.97 | 52.74 | 35.37 | 33.69 |

| 0.1 | 30.92 | 50.77 | 35.40 | 35.69 |

| 0.03 | 31.36 | 52.14 | >40* | >40* |

Not studied beyond 40 cycles

Analysis of transplanted human fetal stem/progenitor cells in chimeric mouse tissue

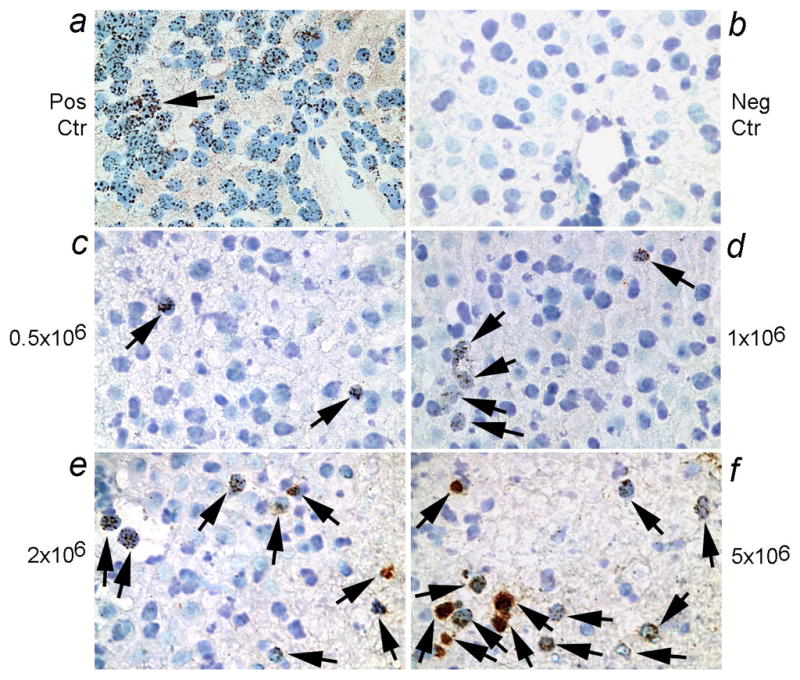

To detect transplanted human cells, we studied tissues from NOD/SCID mice after transplanting male human fetal liver stem/progenitor cells, ranging from 0.5 to 5×106 cells per animal. To verify appropriate engraftment of transplanted cells in the mouse liver, we performed in situ hybridization with alphoid DNA probe. This produced multiple in situ hybridization signals in human nuclei, although the extent of hybridization signals was variable, as would be expected from the ploidy state of cells (diploid, 46 chromosomes = 46 signals; polyploidy, multiples of 46 signals) (Fig. 2a). It should be noteworthy that depending on cell sizes, entire cell nuclei will not be included in tissue sections and differences in the portions of nuclei included will also be inevitable due to the 3-dimentional structure of tissues. Nonetheless, multiple centromeric signals were readily observed in each nucleus, which increased the probability of demonstrating transplanted human cells in mice. No hybridization signals were observed in mouse tissue (Fig. 2b). We identified transplanted fetal human liver stem/progenitor cells in vascular spaces and parenchyma of the liver in recipient mice, as was expected. After transplanting 0.5×106 human cells, only occasional transplanted cells were observed in the liver (Fig. 2c). Progressively more human cells were observed after transplantation of 1×106, 2×106 or 5×106 cells (Fig. 2d–2f).

Figure 2. Transplanted human fetal liver stem/progenitor cells in mouse liver.

Shown is in situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled pancentromere probe followed by visualization of peroxidase activity with DAB to generate brown color. Panel a shows brown nuclear signals in fetal human liver (arrow; positive control), whereas mouse liver was negative (b). The prevalence of human cells 24 h after cell transplantation was related to cell numbers transplanted, as seen with 0.5×106 cells (c), 1×106 cells (d), 2×106 cells (e), and 5×106 cells (f). Arrows point toward transplanted cells. Orig. Mag., ×400.

As the mouse liver is estimated to contain a total number of 1×108 cells, transplantation of these cell numbers represented 0.5%, 1%, 2% and 5% of the liver cell mass, which was within the range of our initial DNA mixing studies. These estimates were based on previous studies showing correlations between the cell numbers transplanted with reconstitution of blood proteins, survival of transplanted cells in tissues, as well as correlations with the number of transplanted cells in reisolated cell fractions (7, 13–15).

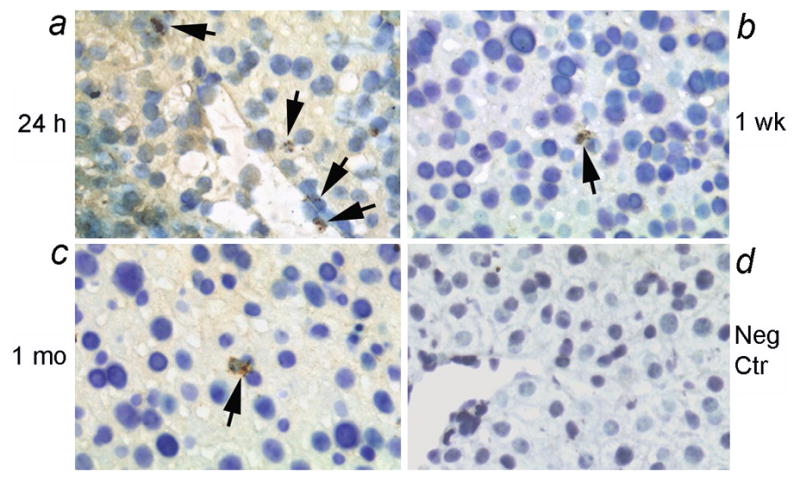

In further studies, we examined whether transplanted human cells engrafted and survived over the long-term with studies over up to 4 weeks. In these studies, we transplanted fetal human pancreatic epithelial stem/progenitor cells that had been immortalized with hTERT. This verified that transplanted cells were present in the liver throughout this period, although the number of human cells declined after 24 h (Fig. 3a–3d). The data were from at least 3 to 6 replicate tissue sections from each mouse and each condition included at least 3 mice.

Figure 3. Long-term survival in mouse liver of transplanted human fetal pancreas stem/progenitor cells modified by hTERT.

Shown are transplanted human cells after 24 h (a), 1 week (b) and 1 month (c), along with a negative control mouse liver (d). Transplanted cells were observed in portal area and vascular spaces after 24 h (arrows, a). Subsequently, occasional transplanted cells were present in the liver parenchyma without evidence of transplanted cell proliferation. No hybridization signals were detected in mouse liver without cell transplantation. Orig. Mag., ×400.

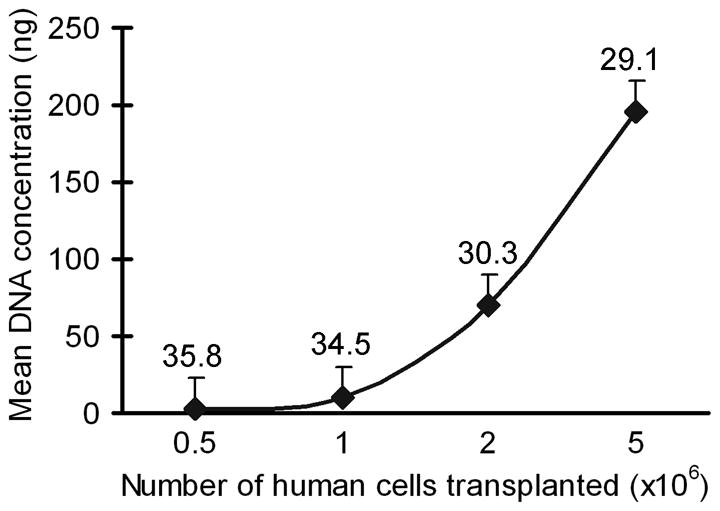

This ability to identify transplanted cells by in situ hybridization offered further opportunities to compare the sensitivity of this procedure with qPCR of tissues. Therefore, we analyzed genomic DNA samples by qPCR from mouse livers 24 h after cell transplantation, as well as 1 week and 4 weeks after cell transplantation, and included mixtures of human and mouse DNA samples for reference. In these studies, qPCR with SRY probe was successful in demonstrating human DNA after 24 h, even when only 0.5×106 human cells were transplanted (Fig. 4). However, STR and CMT1A qPCR probes required excessive cycle numbers for identifying low levels of human DNA in recipients of human cells. None of the qPCR probes were successful in demonstrating transplanted cells in tissues beyond 24 h, presumably because the level of transplanted human cells in liver was below the threshold of qPCR detection.

Figure 4. Quantitation of human DNA in mouse liver after cell transplantation.

qPCR for SRY in liver samples from animals 24 h after cell transplantation showing detection of transplanted cells. Mean DNA concentration on y-axis refers to the amount of input DNA from chimeric mice in each PCR reaction. The threshold cycle at which human genomes were detected is given above each condition. The data are from replicate samples in multiple animals (n=3 each).

DISCUSSION

These studies demonstrated that qPCR for CMT1A, as well as HLA-A STRs was less sensitive for detecting human DNA in mixtures of human and mouse genomic DNAs, while the SRY probe was more sensitive for that purpose. On the other hand, in situ detection of transplanted cells with the pancentromeric alphoid satellite probe was effective even when relatively few human cells had been transplanted in the mouse liver and when relatively few transplanted human cells engrafted and survived in the liver over the long-term, up to 4 weeks.

As the utility of SRY probes is restricted to the identification of male cells containing the Y chromosome (7), we recently developed the CMT1A probe, which is representative of highly homologous 24 kilobase pair-long sequences on the human chromosome 17p11.2-12 and is thus autosomally transmitted in all cells (10). The CMT1A element is highly conserved in primates, including humans and chimpanzees, and is absent in rodents and lower mammals. Therefore, we reasoned that CMT1A sequences will demonstrate individual human genomes in mice originating from transplanted human cells, irrespective of the tissue origin of human cells, including male and female donors. However, the inability of qPCR for a single (CMT1A) gene to identify transplanted cells should indicate that this approach will likely be similarly limited in case of other single copy candidate gene probes.

The length of STRs ranges from 2 to 10 basepairs, which may account for their lower sensitivity compared with SRY probe in detection of human genomes in mice. On the other hand, VNTR and STR-based assays have been useful for detecting allogeneic cells after bone marrow transplantation (8). Moreover, STR probes have been useful for establishing genetic matches, including for sensitive forensic applications, as well as haplotype analysis of kindred (9). Our data indicate that STR probes, e.g., STRs 39B and 54 studied here were from HLA-A regions beyond the telomeric end, will be effective for identifying appropriate numbers of human cells in animals. In particular, HLA STRs could be useful for identifying cells of more than one donor in the same animal because curated panels of HLA-restricted STR probes may be organized. The sensitivity of STR-based approaches could be enhanced by incorporation of fluorogenic substrates in PCR and detection with capillary electrophoresis.

However, our comparative studies showed here that qPCR for SRY was more sensitive for detecting human cells in mouse tissues. The basis of this difference in sensitivity with the SRY probe likely resides in multiple representations of sequences within the Y-chromosome locus of SRY (16). The SRY probe has been effective for detecting male human DNA in mixed samples (7), and should be useful for cell transplantation studies, including for studies of stem/progenitor cells. Our results showing that transplanted cells representing approximately 1% of the liver cell mass were successfully demonstrated with the SRY probe should be encouraging. When an organ is progressively repopulated with transplanted cells, less sensitive though highly-specific probes, such as STR or CMT1A probes, should also be effective. As the gender of donor cells will be of no consequence for applications of STR or CMT1A probes, this should constitute a particular advantage. Although a potential way to overcome the issue for single copy gene targets could be to amplify longer stretches of DNA sequences, the fidelity of qPCR generally requires amplification of shorter rather than longer gene sequences.

In situ localization of human cells in tissues will be necessary for analyzing phenotypic changes in transplanted stem/progenitor cells, including for studies of cell differentiation and proliferation in cell subsets. For example, by combining in situ hybridization with centromeric probe to localize transplanted human cells and simultaneous immunohistochemical studies of cellular proteins, the fate as well as function of transplanted human cells, including expression of transgenes in cells, was established in vivo (2). However, as the efficiency by which stem/progenitor cells engraft in tissues tends to be low and the majority of transplanted cells are usually cleared before engraftment, highly sensitive methods to identify human cells in animal models are required. Therefore, development of alternative molecular approaches to screen for transplanted cells in mouse tissues will be helpful.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH grants R01 DK46952, R01 DK071111, P30 DK41296, and P30 CA13330, and by a grant from Empire State Stem Cell Board, State of New York, Albany, New York.

References

- 1.MURRY CE, KELLER G. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells to clinically relevant populations: lessons from embryonic development. Cell. 2008;132:661–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.INADA M, FOLLENZI A, CHENG K, et al. Phenotype reversion in fetal human liver epithelial cells identifies the role of an intermediate meso-endodermal stage before hepatic maturation. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1002–13. doi: 10.1242/jcs.019315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.BENTEN D, FOLLENZI A, BHARGAVA KK, et al. Organ-specific targeting of transplanted endothelial cells in intact mice. Hepatology. 2005;42:140–148. doi: 10.1002/hep.20746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.KORBLING M, KATZ RL, KHANNA A, et al. Hepatocytes and epithelial cells of donor origin in recipients of peripheral-blood stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:738–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa3461002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.BENTEN D, CHENG K, GUPTA S. Identification of transplanted human cells in animal tissues. Meth Mol Biol. 2006;326:189–201. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-007-3:189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CHO JJ, JOSEPH B, SAPPAL BS, et al. Analysis of the functional integrity of cryopreserved human liver cells including xenografting in immunodeficient mice to address suitability for clinical applications. Liver Int. 2004;24:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WANG LJ, CHEN YM, GEORGE D, et al. Engraftment assessment in human and mouse liver tissue after sex-mismatched liver cell transplantation by real-time quantitative PCR for Y chromosome sequences. Liver Transplantation. 2002;8:822–28. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.34891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.SCHICHMAN SA, SUESS P, VERTINO AM, GRAY PS. Comparison of short tandem repeat and variable number tandem repeat genetic markers for quantitative determination of allogeneic bone marrow transplant engraftment. Bone Marrrow Transpl. 2002;29:243–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.BICK SL, BICK DP, WELLS BE, et al. Preimplantation HLA haplotyping using tri-, tetra-, and pentanucleotide short tandem repeats for HLA matching. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2008;25:323–31. doi: 10.1007/s10815-008-9233-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.KELLER MP, SEIFRIED BA, CHANCE PF. Molecular evolution of the CMT1A-REP region: a human- and chimpanzee-specific repeat. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:1019–26. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WEGE H, LE HT, CHUI MS, et al. Telomerase reconstitution immortalizes human fetal hepatocytes without disrupting their differentiation potential. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:432–444. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ZALZMAN M, GUPTA S, GIRI RK, et al. Reversal of hyperglycemia in mice using human expandable insulin-producing cells differentiated from fetal liver progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7253–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1136854100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PONDER KP, GUPTA S, LELAND F, et al. Mouse hepatocytes migrate to liver parenchyma and function indefinitely after intrasplenic transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1217–1221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.RAJVANSHI P, KERR A, BHARGAVA KK, BURK RD, GUPTA S. Efficacy and safety of repeated hepatocyte transplantation for significant liver repopulation in rodents. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1092–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.FOLLENZI A, BENTEN D, NOVIKOFF P, et al. Transplanted endothelial cells repopulate the liver endothelium and correct the phenotype of hemophilia A mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:935–945. doi: 10.1172/JCI32748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CUI KH, WARNES GM, JEFFREY R, MATTHEWS CD. Sex determination of preimplantation embryos by human testis-determining-gene amplification. Lancet. 1994;343:79–82. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90815-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]