Abstract

Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) is a Ca2+-releasing messenger. Biological data suggest that its receptor has two binding sites: one high-affinity locking site and one low-affinity opening site. To directly address the presence and function of these putative binding sites, we synthesized and tested analogues of the NAADP antagonist Ned-19. Ned-19 itself inhibits both NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release and NAADP binding. A fluorometry bioassay was used to assess NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release, whereas a radioreceptor assay was used to assess binding to the NAADP receptor (only at the high-affinity site). In Ned-20, the fluorine is para rather than ortho as in Ned-19. Ned-20 does not inhibit NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release but inhibits NAADP binding. Conversely, Ned-19.4 (a methyl ester of Ned-19) inhibits NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release but cannot inhibit NAADP binding. Furthermore, Ned-20 prevents the self-desensitization response characteristic of NAADP in sea urchin eggs, confirming that this response is mediated by a high-affinity allosteric site to which NAADP binds in the radioreceptor assay. Collectively, these data provide the first direct evidence for two binding sites (one high- and one low-affinity) on the NAADP receptor.

Introduction

Ca2+ is an extremely versatile and powerful second messenger (1). Three accepted Ca2+-releasing second messengers that cells utilize to control the spatiotemporal properties of these Ca2+ signals are inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (2), cyclic ADP-ribose (3), and nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP)2 (4). Of these three messengers, little is known about the mechanism of action of NAADP. NAADP is the most potent of the three Ca2+-releasing messengers (5), and its actions are pharmacologically distinct from inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and cyclic ADP-ribose (6–9). Controversy surrounds both the identity of the NAADP-activated channel and its organellar location. There is evidence for the NAADP receptor being the transient receptor potential mucolipin 1 channel (10), the ryanodine receptor (11, 12), or the two-pore channel (Refs. 13–15; for review, see Ref. 16). There is evidence for the Ca2+ store targeted by NAADP being the endoplasmic reticulum (11) or physically distinct (17), acidic, lysosome-related organelles (18).

One of the most intriguing features of NAADP is the relationship between concentration, binding, and response (5, 9, 19). In sea urchin eggs, a subthreshold concentration of NAADP that does not itself release Ca2+ is able to prevent Ca2+ release in response to a second addition of NAADP that would normally be able to release Ca2+ (20, 21). This unusual desensitization may relate to the formation of a spatial and temporal “memory” (22, 23). This effect is thought to be due to a second high-affinity inhibitory site present on the receptor (24); thus, at low concentrations, NAADP only binds to this site and is able to prevent Ca2+ release via this receptor. In contrast to sea urchin eggs, in mammalian tissue, NAADP has a bell-shaped concentration-response curve (25). As the concentration of NAADP increases, the amount of Ca2+ released also increases. An optimal concentration of NAADP causes maximal Ca2+ release, after which increasing concentrations of NAADP actually release less Ca2+, with very high concentrations of NAADP unable to release any Ca2+ at all (25, 26). The mammalian response can also be explained by a two-site model of the receptor, whereby binding to the high-affinity site activates the receptor, whereas binding to the low-affinity site inactivates it.

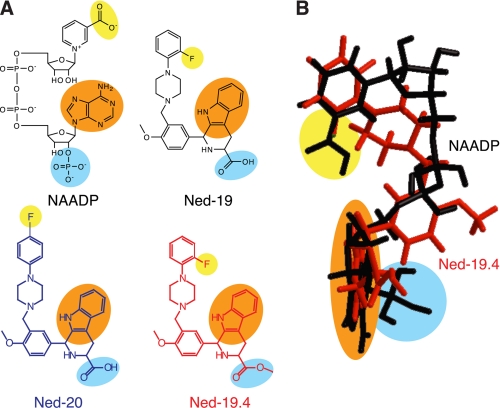

One of the major problems associated with investigating NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release is that there are very few pharmacological tools with which we can alter the signaling pathway (27). To meet the need for selective and useful chemical probes for studying NAADP signaling, we have synthesized a cell-permeant form of NAADP, NAADP-acetoxymethyl ester, which is cleaved by esterases intracellularly to become biologically active (28), and identified a drug-like, cell-permeant, and selective NAADP antagonist, Ned-19 (see Fig. 1A) (29). Current data suggest that the structure of Ned-19 is highly correlated to its function, as its cis and trans isomers have different affinities and Ned-20 (differs from Ned-19 by a para-fluorine rather than ortho) is biologically inert (29). We therefore synthesized analogues of Ned-19 to identify compounds with different pharmacological profiles with regard to affinity, efficacy, or both. Here, we describe analogues of Ned-19 (see Fig. 1A) with different pharmacological activities to provide the first direct evidence for two binding sites on the NAADP receptor.

FIGURE 1.

Structural comparisons of NAADP and the Ned-19 analogues. A, two-dimensional chemical structure of NAADP, Ned-19, Ned-19.4, and Ned-20. Structural groups that mimic one another are highlighted in the same color. B, three-dimensional overlay of NAADP (black) and Ned-19.4 (red) illustrating the basis of the mimicry.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All materials were purchased from Sigma Aldrich unless otherwise indicated. Ned-19, Ned-19.4, and Ned-20 were synthesized as previously described (29).

Sea Urchin Homogenate Preparation

Eggs were harvested from Lytechinus pictus by intracoelomic injection of ∼1 ml of 0.5 m KCl. Artificial seawater was prepared to have the following composition: 435 mm NaCl, 15 mm MgSO4, 11 mm CaCl2, 10 mm KCl, 2.5 mm NaHCO3, 20 mm Tris-Cl. pH was adjusted to 8.0 using KOH. Homogenate was then prepared as described previously (30, 31) in an intracellular-like buffer containing 250 mm potassium gluconate, 250 mm N-methylglucamine, 1 mm MgCl2, and 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.2).

Radioreceptor Binding Assay

[32P]NAADP was synthesized in a two-step reaction as described previously (7, 31). The radioreceptor assay was performed as described previously (32). NAADP-binding protein from L. pictus egg homogenate was used. This is highly specific for NAADP (33, 34). First, 25 μl of either standard NAADP or compound in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each tube. Second, 125 μl of 1% (v/v) sea urchin egg homogenate in intracellular medium was added and allowed to incubate for 10 min. Finally, we added 100 μl of intracellular medium containing [32P]NAADP to generate ∼50,000 scintillation counts/min/tube. The tubes were then incubated at room temperature for a further 10 min. The nonradiolabeled compounds were added prior to the [32P]NAADP to enable direct comparison with previous studies (29, 32, 34). A preincubation with the test compound was used in previous studies so that the test compounds are able to bind without having their equilibrium affected by NAADP, which has an off rate so slow as to make its binding effectively irreversible over the time course of the experiment.

NAADP was then trapped onto Whatman GF/B filter papers using a Brandel Cell Harvester. Washing was carried out using a buffer containing 20 mm HEPES, 500 mm potassium acetate (pH 7.4). Radioactivity was determined using a storage phosphor screen and Typhoon scanner (GE Healthcare), a method equally effective to the traditional Cerenkov scintillation counting (32).

Sea Urchin Homogenate Bioassay

On the day of use, an aliquot of homogenate was sequentially diluted in equal volumes of intracellular buffer (with the addition of 2 mm ATP, 20 mm phosphocreatine, and 20 units/ml creatine phosphokinase) over a period of 3 h at 17 °C to give 2.5% (v/v) final concentration (31). Fluorometry was conducted in a PerkinElmer LS50B luminescence spectrometer at 17.5 °C. We used 600 μl of homogenate/cuvette. To determine whether the compounds had Ca2+ contamination or released Ca2+ themselves, we added the compounds to the homogenate and monitored the response. After a 3–5-min incubation, 50 nm NAADP was added, and Ca2+ release was measured with 3 μm fluo-3 (excitation at 506 nm and emission at 526 nm).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Prism 4 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Inhibition of NAADP-mediated Ca2+ Release by Ned-19, Ned-20, and Ned-19.4

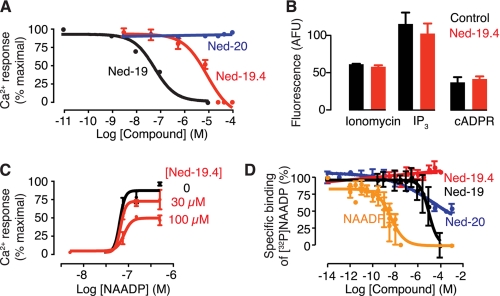

A previous study revealed that the fluorine of Ned-19 is vital for its efficacy, because Ned-20 (Fig. 1A) is inactive in the Ca2+ release assay (29). To determine the role of the carboxylic acid group of Ned-19 in its activity, we synthesized its methyl ester, Ned-19.4 (Fig. 1A). We used the sea urchin homogenate bioassay to assess the activity of the Ned-19 analogues on NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release (31). NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release was inhibited by both Ned-19 (IC50 of 65 nm) and Ned-19.4 (IC50 values of 10 μm) but not by Ned-20, even at 100 μm (Fig. 2A). This suggests that both the carboxylic acid and fluorine are key functional groups for biological activity; esterification of the carboxylic acid dramatically reduces the potency of Ned-19, whereas repositioning the fluorine from ortho to para on the benzene ring renders the molecule unable to inhibit NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release. The effect is specific for NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release because Ned-19.4 did not affect Ca2+ release induced by ionomycin, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate, or cyclic ADP-ribose (Fig. 2B). Ned-19 is not a competitive inhibitor because it causes a decrease in maximal response to NAADP as well as increases the EC50, whereas Ned-20 has no effect (29). To investigate the manner by which Ned-19.4 antagonizes NAADP, we assessed the response to a range of concentrations of NAADP in the presence of varying concentrations of Ned-19.4 (Fig. 2C). Preincubation with Ned-19.4 reduced the maximal response elicited by maximal NAADP, without affecting the EC50 (Fig. 2C). The lack of an effect on the EC50 is in contrast to that seen in the presence of Ned-19.

FIGURE 2.

Ned-19 analogues exhibit different effects on NAADP-induced Ca2+ release and [32P]NAADP binding indicating two binding sites for NAADP on its receptor. A, effects of Ned-19 analogue concentration on NAADP-induced Ca2+ release. Sea urchin egg homogenate was preincubated (3–5 min) with the indicated concentrations of Ned-19 analogues. The Ca2+ response to 50 nm NAADP (approximate EC50) was then measured. B, Ned-19.4 selectively inhibits NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release. Ca2+ release mediated by ionomycin (5 μm), inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3; 5 μm), and cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR; 1 μm) is unaffected by Ned-19.4 compared with the control (1% DMSO). AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units. C, effect of several Ned-19.4 concentrations on the concentration-response relationship for NAADP-induced Ca2+ release. The control is labeled “0” and contained 1% DMSO. For NAADP, the EC50 values are as follows: 65 nm (control), 75 nm (100 μm Ned-19.4), and 65 nm (30 μm Ned-19.4). D, effect of NAADP and Ned-19 analogues on [32P]NAADP binding. The IC50 values are as follows: Ned-19, 4 μm; Ned-20, 1 μm; Ned-19.4 does not bind.

Competition of NAADP Binding

As well as assessing inhibition of NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release, we are able to see whether these compounds could compete with NAADP binding to its receptor using the radioreceptor binding assay (20, 32). Ned-19 prevented [32P]NAADP binding to the receptor with an IC50 of 4 μm (Fig. 2D). Ned-19.4 was unable to prevent [32P]NAADP binding to the receptor, whereas Ned-20 prevented [32P]NAADP binding with an IC50 of 1.2 μm, similar to that of Ned-19 (Fig. 2D) (29). These data suggest two things: first, that binding to the receptor at this site is not necessary to inhibit Ca2+ release because Ned-19.4 inhibits Ca2+ release but not [32P]NAADP binding; and second, that binding to the receptor at this site does not necessarily mean inhibition of Ca2+ release, as Ned-20 is able to bind to the receptor without inhibiting Ca2+ release. The shallow slope and incomplete displacement of [32P]NAADP by Ned-20 are consistent with allosteric displacement (35). Moreover, allosteric ligands often have very slow off rates of hours or days (36), also consistent with the slow off rate for Ned-19 (29). Together, these data support previous suggestions that the observed binding in the assay is to an allosteric site with high affinity that is inhibitory rather than an orthosteric site that activates the channel (24, 33).

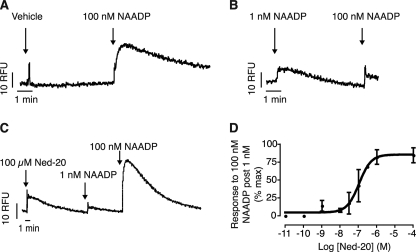

Modulation of the NAADP Self-desensitization Response

One of the most interesting and unique properties of NAADP signaling in sea urchin eggs is its self-desensitizing property, as discussed previously. It is thought that a high-affinity inhibitory site mediates this action, and it is at this site that we observe binding in the radioreceptor assay (24, 33). Because Ned-20 prevents [32P]NAADP binding to the receptor in the binding assay (Fig. 2D) but has no discernable ability to inhibit Ca2+ release (Fig. 2A), we investigated whether Ned-20 was able to prevent self-desensitization by NAADP (20, 21). Addition of 100 nm NAADP after a preincubation with vehicle (1% DMSO) resulted in a robust increase in Ca2+ (Fig. 3A). In contrast, preincubation with 1 nm NAADP dramatically reduced the response to 100 nm NAADP (Fig. 3B). Incubation of the homogenate with 100 μm Ned-20 for 10 min before adding the 1 nm NAADP restored the ability of 100 nm NAADP to release Ca2+ (Fig. 3C), i.e. Ned-20 blocked the self-desensitization. The ability of Ned-20 to inhibit the self-desensitization response was concentration-dependent (Fig. 3D), with an IC50 of 109 nm.

FIGURE 3.

Ned-20 prevents NAADP self-desensitization. A, example trace of a control response to 100 nm NAADP following a 5-min incubation with vehicle (1% DMSO). B, example trace of a desensitization response to a low concentration of NAADP. Sea urchin egg homogenate was incubated with a low concentration of NAADP (1 nm) for 5 min before the addition of 100 nm NAADP. C, example trace showing Ned-20-mediated inhibition of the NAADP self-desensitization response. Preincubation (10 min) with Ned-20 (100 μm) prevented self-desensitization induced by 1 nm NAADP. D, effect of Ned-20 concentration on inhibition of the NAADP self-desensitization response. The experiment was conducted as in C but with the concentration of Ned-20 varied. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

DISCUSSION

Because NAADP is a relatively uncharacterized Ca2+-releasing messenger, there are few pharmacological tools to investigate NAADP physiology (reviewed in Ref. 37). By performing medicinal chemistry on Ned-19, a recently discovered antagonist of NAADP (29), we have been able to provide evidence for two distinct binding sites on the NAADP receptor and provide chemical probes for further characterization of the NAADP signaling pathway.

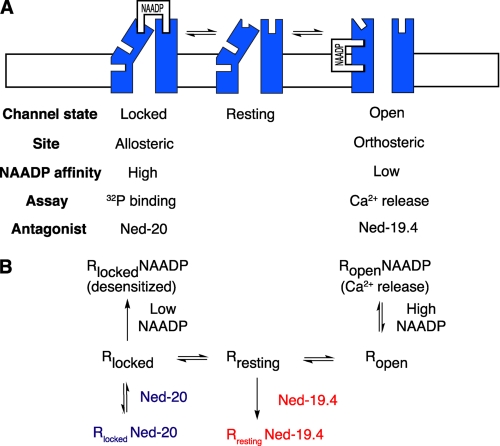

Taking our data as a whole, we propose a mechanistic model for NAADP activation and inactivation of the NAADP receptor (Fig. 4). We propose a three-state model (Fig. 3B). This model is based on the two-state or multistate model developed for G-protein-coupled receptors in which proteins undergo spontaneous conformational transitions, and these different preexisting conformations are then selectively stabilized by ligand binding (38). Upon addition of a given ligand, the equilibria are shifted toward this stabilized conformation. For the NAADP receptor, low concentrations of NAADP selectively occupy an allosteric high-affinity site on the locked state of the channel. Conversely, high concentrations of NAADP bind to an orthosteric low-affinity site on the open channel. Only the high-affinity site is detected with [32P]NAADP binding. Direct evidence for the high-affinity site comes from the ability of Ned-20 to block [32P]NAADP binding and prevent desensitization without affecting NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release (Fig. 4). Direct evidence for the low-affinity site comes from the ability of Ned-19.4 to prevent NAADP-mediated calcium release but not affect binding or presumably channel inactivation. The mechanism contains linked equilibria, which are either readily reversible or have off rates so slow that they are effectively unidirectional and trap the receptor and the ligand (Fig. 4). This mechanism explains how low concentrations of NAADP will pull all receptors into a locked, desensitized state, which is time-dependent (20). Implicit in this model is that for NAADP to be able to release Ca2+ it has to bind to the orthosteric site on the open receptor faster than to the higher-affinity allosteric site on the locked receptor (39).

FIGURE 4.

Model for the action of NAADP at its receptor in sea urchin egg. A, schematic depicting the NAADP receptor channel illustrating a possible relationship between receptor state (function) and orthosteric and allosteric binding sites. B, mechanistic three-state model for the NAADP receptor. The receptor is in thermodynamic equilibrium with all three states, with the most prominent state being “resting” in the absence of ligand. High concentrations of NAADP bind to the low-affinity orthosteric site of the open receptor state, stabilizing this conformation and shifting the equilibria of the states to “open,” resulting in Ca2+ release. The orthosteric binding site can be antagonized by Ned-19.4. Low concentrations of NAADP bind to the high-affinity allosteric site on the “locked” receptor state, stabilizing this state and thereby shifting the equilibria and resulting in self-desensitization. Binding to the allosteric site can be detected with [32P]NAADP. Either the bound NAADP at the allosteric site is occluded, or the off rate is slow enough to make binding effectively irreversible over the time course of the experiments. This allosteric binding site activity can be reversibly antagonized by Ned-20.

The Ned-20 data support the notion that there are two binding sites and that the binding assay only reveals the binding of NAADP to the allosteric site. Because Ned-20 is unable to inhibit NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release, it cannot be binding to, or having any discernable effect at, the orthosteric site. Ned-20 competes with NAADP for binding at the allosteric site. As NAADP can still bind to the orthosteric site on the open channel, Ned-20 has no effect on NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release. Furthermore, Ned-20 prevents the self-desensitization response of NAADP (20), thought to be mediated by a high-affinity site (24). We can now substantiate that this allosteric site does indeed mediate this self-desensitization response and is also the binding site observed in the binding assay.

These data also reveal structure-activity relationships for the biological activity of Ned-19. The similarity between NAADP, Ned-19, Ned-19.4, and Ned-20 can be seen by comparing the two-dimensional structures of the compounds (Fig. 1A) but is much more apparent when they are compared in three dimensions (Fig. 1B). The position of the carboxylic acid or methyl ester for Ned-19.4 corresponds to the 2′-phosphate on NAADP (Fig. 1B) (29). We know that this phosphate is important for NAADP activity because the equivalent compound lacking it, NAAD, is unable to release Ca2+ or prevent [32P]NAADP from binding (4, 33). It is therefore not surprising that modifying the carboxylic acid group at this position by methylation in Ned-19.4 has a pronounced effect on biological activity. Similarly, the fluorine of Ned-19 likely mimics the carboxylic acid group on NAADP (Fig. 1). Repositioning of the fluorine group as in Ned-20 reduces the efficacy compared with Ned-19. This fits with the structure-activity data for NAADP itself. On NAADP, the carboxylic acid group is important for the biological activity because NADP (nicotinamide rather than a nicotinic acid base) is unable to release Ca2+ or affect [32P]NAADP binding (4, 33). Moreover, analogues of NAADP in which the nicotinic acid base is replaced with different charges or sized groups also have pronounced effects on biological activity (5, 40). Thus, the biological activity of Ned-19 is highly dependent on the fluorine and carboxylic acid.

When considering the mechanism of action of Ned-19, it is also necessary to consider its effect on the concentration-response curve of NAADP. Ned-19 is not a competitive inhibitor because it does not cause the classical rightward parallel shift of the NAADP concentration-response curve (29). With the data we now present, there are two possible ways by which Ned-19 could inhibit NAADP-mediated Ca2+ release and produce the change in the concentration-response curve of NAADP. It is possible that Ned-19 binds to the orthosteric site on the open state channel irreversibly, its binding to the allosteric site on the locked state channel being purely coincidental. Alternatively, Ned-19 binds to the allosteric site and stabilizes the locked state channel, in a similar manner to a subthreshold concentration of NAADP. Ned-19 may further act at the orthosteric site on the open state channel, but binding at this site may or may not be irreversible. It is likely that the actual mechanism is a combination of the two because of the manner in which Ned-19.4 affects the concentration-response curve of NAADP. Ned-19.4 reduces the maximal response and has no effect on the EC50, corroborating the notion that binding to the orthosteric site has an off rate slow enough to make binding of Ned-19.4 effectively irreversible over the time course of the experiment. If Ned-19.4 binding were reversible, we would expect to only see a rightward shift in EC50, with no drop in maximal response. Irreversible competition at the orthosteric site has the same effect as reducing the number of available receptors, which means that the maximal response would reduce. The EC50 for NAADP is shifted by Ned-19 but not Ned-19.4, suggesting that Ned-19 also acts at the allosteric site. These combined actions explain why Ned-19 shifts the EC50 and is so potent. In conclusion, we have used analogues of Ned-19 to provide the first direct evidence for more than one binding site for NAADP on its receptor.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. C. Lee (University of Hong Kong) for kindly donating the ADP-ribosyl cyclase and F. Berger (University of Berlin) for kindly providing the NAD kinase.

This work was supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Grant BB/G008523/1.

- NAADP

- nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berridge M. J., Lipp P., Bootman M. D. (2000) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1, 11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Streb H., Irvine R. F., Berridge M. J., Schulz I. (1983) Nature 306, 67–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee H. C., Walseth T. F., Bratt G. T., Hayes R. N., Clapper D. L. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 1608–1615 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee H. C., Aarhus R. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2152–2157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee H. C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33693–33696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clapper D. L., Walseth T. F., Dargie P. J., Lee H. C. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 9561–9568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aarhus R., Graeff R. M., Dickey D. M., Walseth T. F., Lee H. C. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30327–30333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galione A., Churchill G. C. (2002) Cell Calcium 32, 343–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guse A. H., Lee H. C. (2008) Sci. Signal. 1, re10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang F., Li P. L. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 25259–25269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hohenegger M., Suko J., Gscheidlinger R., Drobny H., Zidar A. (2002) Biochem. J. 367, 423–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dammermann W., Zhang B., Nebel M., Cordiglieri C., Odoardi F., Kirchberger T., Kawakami N., Dowden J., Schmid F., Dornmair K., Hohenegger M., Flügel A., Guse A. H., Potter B. V. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10678–10683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calcraft P. J., Ruas M., Pan Z., Cheng X., Arredouani A., Hao X., Tang J., Rietdorf K., Teboul L., Chuang K. T., Lin P., Xiao R., Wang C., Zhu Y., Lin Y., Wyatt C. N., Parrington J., Ma J., Evans A. M., Galione A., Zhu M. X. (2009) Nature 459, 596–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zong X., Schieder M., Cuny H., Fenske S., Gruner C., Rötzer K., Griesbeck O., Harz H., Biel M., Wahl-Schott C. (2009) Pflugers Arch. 458, 891–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brailoiu E., Churamani D., Cai X., Schrlau M. G., Brailoiu G. C., Gao X., Hooper R., Boulware M. J., Dun N. J., Marchant J. S., Patel S. (2009) J. Cell Biol. 186, 201–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guse A. H. (2009) Curr. Biol. 19, R521–R523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H. C., Aarhus R. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 4413–4420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Churchill G. C., Okada Y., Thomas J. M., Genazzani A. A., Patel S., Galione A. (2002) Cell 111, 703–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galione A., Ruas M. (2005) Cell Calcium 38, 273–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aarhus R., Dickey D. M., Graeff R. M., Gee K. R., Walseth T. F., Lee H. C. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 8513–8516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genazzani A. A., Empson R. M., Galione A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 11599–11602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Churchill G. C., Galione A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 11223–11225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Churamani D., Dickinson G. D., Ziegler M., Patel S. (2006) Biochem. J. 397, 313–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel S., Churchill G. C., Galione A. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 482–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cancela J. M., Churchill G. C., Galione A. (1999) Nature 398, 74–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berg I., Potter B. V., Mayr G. W., Guse A. H. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 150, 581–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galione A., Parrington J., Dowden J. (2004) Br. J. Pharmacol. 142, 1203–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parkesh R., Lewis A. M., Aley P. K., Arredouani A., Rossi S., Tavares R., Vasudevan S. R., Rosen D., Galione A., Dowden J., Churchill G. C. (2007) Cell Calcium 43, 531–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naylor E., Arredouani A., Vasudevan S. R., Lewis A. M., Parkesh R., Mizote A., Rosen D., Thomas J. M., Izumi M., Ganesan A., Galione A., Churchill G. C. (2009) Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 220–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dargie P. J., Agre M. C., Lee H. C. (1990) Cell Regul. 1, 279–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan A. J., Churchill G. C., Masgrau R., Ruas M., Davis L. C., Billington R. A., Patel S., Yamasaki M., Thomas J. M., Genazzani A. A., Galione A. (2006) in Calcium Signaling (Putney J. W. ed) 2nd Ed., pp. 265–334, CRC/Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis A. M., Masgrau R., Vasudevan S. R., Yamasaki M., O'Neill J. S., Garnham C., James K., Macdonald A., Ziegler M., Galione A., Churchill G. C. (2007) Anal. Biochem. 371, 26–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Billington R. A., Genazzani A. A. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 276, 112–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel S., Churchill G. C., Galione A. (2000) Biochem. J. 352, 725–729 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christopoulos A., Kenakin T. (2002) Pharmacol. Rev. 54, 323–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson C., Jenkinson S., Kazmierski W., Kenakin T. (2005) Mol. Pharmacol. 67, 1268–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galione A. (2006) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 922–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kenakin T. (2003) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 24, 346–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Genazzani A. A., Mezna M., Summerhill R. J., Galione A., Michelangeli F. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 7669–7675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Billington R. A., Tron G. C., Reichenbach S., Sorba G., Genazzani A. A. (2005) Cell Calcium 37, 81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]