Abstract

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and RNA metabolism are considered to be important for modulating gene expression in trypanosomes, because these protozoan parasites mainly rely on post-transcriptional mechanisms to regulate protein levels. Previously, we have identified TcUBP1, a single RNA recognition motif (RRM)-type RBP from Trypanosoma cruzi. TcUBP1 is a cytoplasmic protein with roles in stabilization/degradation of mRNAs and in the protection of transcripts through their recruitment into cytoplasmic granules. We now show that TcUBP1, and the closely related protein TcUBP2, can be found in small amounts in the nucleus under normal conditions, and are able to accumulate in the nucleus under arsenite stress. The kinetics of nuclear accumulation, and export to the cytoplasm, are consistent with the shuttling of TcUBP1 between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. The sequence required for TcUBP1 nuclear accumulation was narrowed to the RRM, and point mutations affecting RNA binding abolished nuclear import. This RRM was also shown to be efficiently exported from the nucleus in unstressed parasites, a property that relied on the binding to RNA. TcUBP1 nuclear accumulation was dependent on active transcription, and colocalized with transcripts in the nucleus, suggesting nuclear binding of the mRNA. We propose that TcUBP1 could be linking the mRNA metabolism at both sides of the nuclear pore complex, using the RRM as a nuclear localization signal, and being exported as a cargo on mRNA.

Introduction

Trypanosomes are parasitic protists producing relevant human and animal diseases worldwide (1). In particular, Trypanosoma cruzi and Trypanosoma brucei, are the causative agents of Chagas disease and sleeping sickness, respectively. Trypanosomes display complex life cycles, which alternate between insect vectors and vertebrate hosts. These parasites require a rapid adaptation to fulfill metabolic and structural changes to subsist in different developmental niches. At odds with most eukaryotes, transcription of protein-coding genes in trypanosomes is polycistronic and mostly regulated by post-transcriptional mechanisms (2, 3). Polycistronic pre-messenger RNAs (mRNAs) are processed into monocistronic mRNAs by 5′ trans-splicing coupled to 3′ polyadenylation (4). Mature transcripts are exported from the trypanosome nucleus by yet unidentified cis-recognized elements and pathways. Once in the cytoplasm, the net balance between mRNA turnover, translation, and silencing dictates protein levels (3, 5). All of these processes are almost exclusively achieved by RNA-binding proteins (RBPs),3 which recognize sequences and/or structure determinants in mRNA 3′ untranslated regions (UTR) (5). At the heart of these trans-acting factors, several RNA recognition motif (RRM)-type RBPs have been identified and characterized in trypanosomes (6, 7). The RRM is the most studied RNA-binding domain, and functions in recognition of nucleic acids and/or proteins (8). RRM-containing proteins take part in most post-transcriptional processes inside cells, including mRNA and rRNA processing, RNA export, and stability (9). Within RRM containing proteins in T. cruzi, TcUBP1 is involved in developmental turnover of certain mRNAs (10, 11). TcUBP1 RRM is 99% identical to the RRM present in TcUBP2, and together with TcRBP3, TcRBP4, TcRBP5a, and TcRBP6b comprise the RRM-type TcRBP family (7). TcUBP1 binds structured sequences found in the 3′-UTR of functionally related transcripts (12). It can also bind the AU-rich RNA element located in the 3′-UTR of certain mucin mRNAs, thus affecting their stability and half-life (10). In T. brucei, TbUBP1 and TbUBP2 could regulate some mRNA levels of products potentially involved in cell division, and were suggested to be essential by RNA interference experiments (13). Most recently, we have shown the association of all members of the TcRBP family as well as TcPABP1 and other proteins to mRNA granules formed in epimastigotes under starvation stress conditions (14). These microscopically visible structures were proposed to serve as mRNAs reservoirs, protecting the transcripts from degradation until the stress is relieved and transcripts can be reutilized (14). TcUBP1 association with mRNA granules is RRM-dependent (14).

In mammals, the physical barrier imposed by the nuclear envelope requires a regulated import and export of factors to accomplish the road from transcript to protein (15). All nucleocytoplasmic traffic occurs through nuclear pore complexes (NPC), allowing the passive diffusion of molecules <40 kDa (15). Transport across NPCs is mediated by soluble factors. Among these, importins and exportins utilize the GTPase Ran gradient to achieve directionality, whereas NTF2 imports Ran back into the nucleus (16, 17). Classical nuclear localization signals (NLS), consisting of monopartite or bipartite stretches of basic amino acids, are the best characterized signals for protein import (18). These NLS are recognized in the cytoplasm by importin α and β, which in the presence of Ran-GDP, NTF2, and GTP are translocated across the NPC (19). Non-classical NLS were described (20), including different RRMs in PABP1 (21, 22), TIA-1, and TIAR (23). Notably, TIA-1 and TIAR nuclear accumulation is dependent on active transcription (23), as it is the case also for heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (24), HuR (25), and many other RBPs (see “Discussion”).

Once in the nucleus, some proteins also shuttle back to the cytoplasm by virtue of the specific recognition of a nuclear export signal by the respective exportin. The best characterized nuclear export signal is the leucine-rich sequence recognized by the CRM1 exporter (exportin 1, XPO1) (26). CRM1 has also been implicated in the export of a small subset of mRNAs in mammals, Caenorhabditis elegans (16, 26) and T. cruzi (27). Notwithstanding this, the vast majority of transcripts are exported via the Tap/Mex67 family of export receptors in mammals and yeast, respectively, independently of the Ran driving force (16, 28), Notably, high identity sequence candidates for Tap or Mex67 orthologs seem to be lacking in trypanosomes (29). Tap operates together with adaptor RBPs (16), such as Yra proteins in yeast and the metazoan counterpart Aly/Ref (30, 31).

In trypanosomes, few NLS have been identified to date, and all of them belong to the canonical SV-40 type (32–34). Much effort has been made to understand the mechanisms underlying cytoplasmic mRNA turnover/stability and translatability in these unicellular parasites. However, identification of proteins linking these processes with messenger ribonucleoprotein particle biogenesis and mRNA export remains elusive. Here we describe the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling activity of a well characterized trypanosomal RRM-type RBP, TcUBP1. Although mostly cytoplasmic, TcUBP1 can accumulate in the nucleus under stress. Functional dissection and site-directed mutagenesis assays revealed the requirement of a functional RRM to retain TcUBP1 shuttling activity, showing dependence of RNA binding for proper subcellular localization. Moreover, TcUBP1 shuttling activity is transcription dependent, and nuclear-accumulated protein co-localizes with bulk poly(A)+ mRNA and a target transcript. The relevance of TcUBP1 nuclear shuttling is discussed in the context of nuclear mRNA cargoes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Parasite Cultures and Drug Treatments

T. cruzi epimastigotes from the RA and CL Brenner strains were cultured in BHT medium at 28 °C as described in Ref. 14. Parasite cultures were taken in late logarithmic growth phase at a cell density of 3–4 × 107 parasites ml−1. For nutritional studies, parasites were washed and incubated in phosphate-buffered saline for the indicated time periods. Sodium arsenite was used at 2 mm for most experiments, at 0.5 mm (mild arsenite stress), or at 0.4 mm for 24 h when indicated. Actinomycin D (ActD), puromycin, and cycloheximide (all from Sigma) were used at 10, 200, and 50 mg ml−1, respectively.

GFP Fusion Constructs and Parasite Transfections

pTEX-eGFP constructs mentioned in supplemental Fig. S4 were the same as in Ref. 14. TcUBP1 fragments and point mutants were generated by PCR using the primers listed in supplemental Table S1 and cloned into the BamHI site of pTEX-eGFP (35) kindly provided by Dr. J. M. Kelly. βGal-GFP fusions were expressed from pTEX-eGFPs-βGal, where the LacZ open reading frame was cloned downstream of GFP in the XhoI and NotI sites of a pTEX-eGFP derivative (pTEX-eGFPs) without the stop codon in GFP, using the primers listed in supplemental Table S1 and using pAB5001 plasmid (36) as template, kindly provided by Dr. Rodrigo Sieira. The NLS in the TcLA protein (GHKRPRD) was cloned downstream of GFP by PCR in the XhoI and NotI sites of pTEX-eGFPs, using overlapping primers listed in supplemental Table S1. Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega) was used for all reactions, and every construct was verified by DNA sequencing. pRibotex-GFP and TcUBP1 in pRibotex-GFP constructs were a gift from Dr. Iván D'Orso. Transfections were carried out as previously described (37).

Immunofluorescence, Poly(A)+, and Amastin RNA Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (FISH)

Immunofluorescence and poly(A)+ mRNA FISH were performed as previously described (14). For amastin mRNA FISH, an antisense RNA probe labeled with digoxigenin (DIG) was used. Briefly, a 197-nucleotide-long conserved and poorly structured sequence of amastin 3′-UTR (comprising nucleotides 158–354, 3′-UTR numeration) was PCR amplified with primers listed in supplemental Table S1. Amplicons were cloned into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pSPT18 and pSPT19 plasmids (DIG labeling kit SP6/T7, Roche Applied Science). Cloned inserts were PCR amplified with SP6 and T7 primers, and RNA probes were synthesized by T7 RNA polymerase using PCR amplicons from pSPT18 (antisense probe), and pSPT19 (sense probe) as templates. In vitro RNA synthesis was performed in the presence of DIG-11-UTP to obtain DIG-labeled probes according to the manufacturer's instructions. Labeling efficiency (2 ng of DIG-labeled probe μl−1) was determined by dot blot using a mouse anti-DIG monoclonal antibody (Roche Applied Science). Hybridization was performed in transfected parasites essentially as described in Ref. 14, with the addition of a denaturation step at 42 °C for 15 min in 40% formamide, 2× SSC after permeabilization of the cells. Heat-denatured probes were used at a final concentration of 0.2 ng μl−1. After extensive washing, parasites were post-fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in 2× SSC, and detection was performed with anti-DIG (1:150) and a secondary anti-mouse antibody conjugated to rhodamine (1:300). After extensive washing, parasites were stained with 1 mg ml−1 of DAPI and mounted with 5 μl of Fluor Save reagent (Calbiochem Novabiochem, La Jolla, CA).

Microscopy

Analysis of subcellular localization was performed in a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope coupled to a SPOT RT color camera (Diagnostic Instruments). Merged images were obtained by superimposing the indicated images files in SPOT Software 4.0.9 (Diagnostic Instruments). The number of analyzed parasites for the nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio determination of GFP fluorescence in Figs. 1B and 5B are shown in supplemental Table S2, whereas those in Fig. 2, B and C, are in supplemental Table S3. In each parasite the fluorescence from the green (GFP) channel was quantified in an area selected according to blue signal (DAPI) fluorescence (nucleus) using the RGB plugin in ImageJ (rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). Cytoplasmic fluorescence was quantified in the same way selecting the brightest perinuclear areas in the green (GFP) channel. Selection criterion was the same for all transfected parasites. Cytoplasmic selections included the previous selected nuclear areas and fluorescence values, which were afterward subtracted, resulting in the area and values corresponding to the cytoplasm. For each parasite, the relationship between fluorescence/area was obtained for the nucleus and cytoplasm. The ratio between the nuclear and cytoplasmic values was obtained for each parasite. Figs. 1B, 2, B and C, and 5B show the mean ± S.D. for each population of parasites. Confocal images were acquired in an LSM 5 PASCAL confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The scheme of the plane shown in confocal images was obtained by visualizing a series of 3–5 Z stack images orthogonally with the LSM image viewer, and the depth of the plane shown (0.37 μm) was determined to scale.

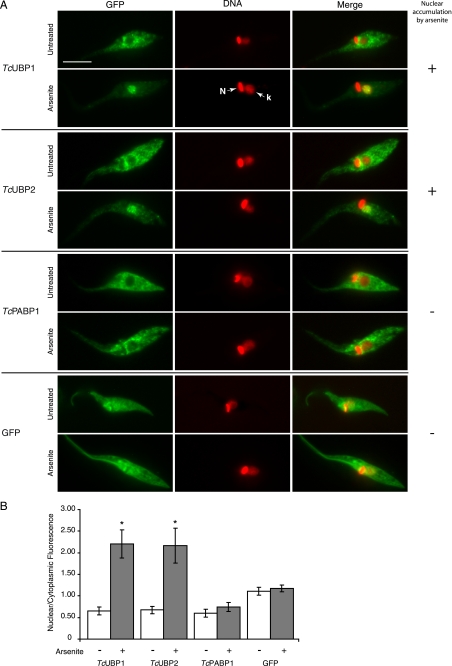

FIGURE 1.

Nuclear accumulation of TcUBP1 and TcUBP2 induced by arsenite. A, the localization of the respective GFP fusion proteins is shown in untreated and arsenite-treated (2 mm, 4 h) parasites. TcPABP1 and GFP are shown as controls. DAPI staining, shown in red for better contrast, reveals the position of nuclear (N) and kinetoplast (k) DNA. The column on the right summarizes if the fusion protein accumulates (+) or not (−) in the nucleus of the parasites under arsenite treatment. Scale bar, 5 μm. B, nuclear/cytoplasmic fluorescence ratio obtained from parasites from different transfection experiments, in the two tested conditions. Bars represent mean ± S.D. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant difference (p < 0.00001) within the same population.

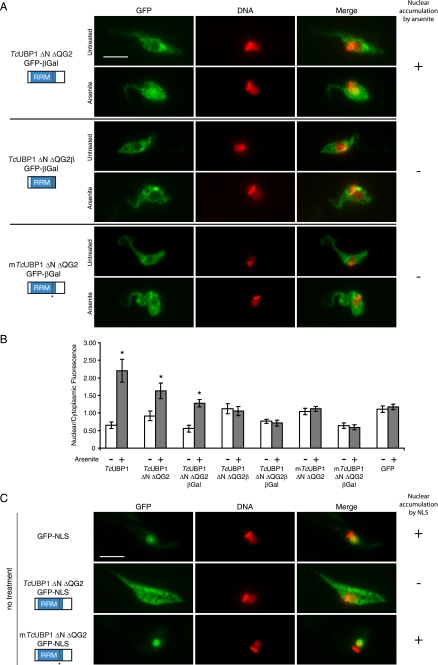

FIGURE 5.

Nuclear import and export of TcUBP1 RRM. A, behavior of TcUBP1 mutants fused to GFP-βGal. The localization of TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2, TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2β, and mTcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2 fused to GFP-βGal is shown in untreated or arsenite-treated (2 mm, 4 h) parasites. The column on the right summarizes if the fusion protein accumulates (+) or not (−) in the nucleus of the parasites under arsenite treatment. B, nuclear/cytoplasmic fluorescence ratio obtained from parasites from different transfection experiments, in the two tested conditions. The ratios of TcUBP1 and GFP are the same as Fig. 1B. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant difference (p < 0.00001) within the same population. C, the localization of GFP-NLS, TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP-NLS, and mTcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP-NLS is shown in untreated parasites. DNA was stained with DAPI, and is shown in red for better contrast. The column on the right summarizes if the fusion accumulates (+) or not (−) in the nucleus due to the NLS. Scale bar, 5 μm.

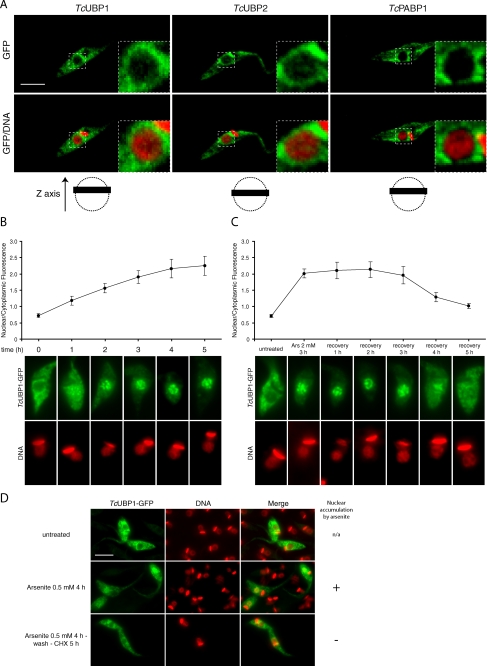

FIGURE 2.

TcUBP1 nucleocytoplasmic dynamics. A, localization of TcUBP1, TcUBP2, and TcPABP1 in untreated transfected parasites by confocal microscopy. A magnification of the dotted area is shown on the top right angle. DNA was stained with propidium iodide. The images shown in the figure are part of a Z stack covering 0.37 μm (black bar) in the z axis, and are represented with dotted circles (nucleus) in the schemes at the bottom. B, TcUBP1 nuclear accumulation kinetics. The graph shows nuclear/cytoplasmic fluorescence mean ± S.D. for each time point of arsenite treatment in the presence of cycloheximide. The images show representative arsenite-treated (2 mm) parasites transfected with TcUBP1-GFP obtained at the time points indicated. Time = 0 is before the addition of the drug. C, TcUBP1 cytoplasmic recovery kinetics. The graph shows nuclear/cytoplasmic fluorescence mean ± S.D. for each time point and treatment. Parasites were incubated with 2 mm arsenite for 3 h, and afterward subjected to recovery after arsenite washing in the presence of cycloheximide. The images show representative parasites transfected with TcUBP1-GFP obtained at the time points or treatments indicated. D, TcUBP1 recovery after mild arsenite stress. Arsenite treatment was performed under mild conditions (0.5 mm) for 4 h. The treatment “Arsenite 0.5 mm 4 h-wash-CHX 5 h” was performed by incubating the parasites with arsenite for 4 h, then the parasites were washed in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX), and recovery continued for an incubation period of 5 h together with cycloheximide. DNA was stained with DAPI, and is shown in red for better contrast. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Western Blot

Whole cell extracts were prepared by incubating parasites in 1× Laemmli buffer plus DNase I (Sigma) for 15 min in ice. Samples were boiled, centrifuged, and loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Gels were transferred to Immobilon-NC transfer membranes (Millipore), probed with rabbit anti-GFP (1:750) (Molecular Probes), anti-RRM (1:750), anti-TcPABP1 (1:1000) (11), anti-TcLA (1:1000), anti-TcHSP70 (1:2000) (38), and anti-tubulin (1:1000) (Sigma), and developed using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit (1:8000) antibodies and the Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In Vitro Homoribopolymer Binding Assay

TcUBP1 and TcUBP2 fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) cloned in pGEX-2T vector (GE Healthcare) (11) were used as templates for PCR-directed mutagenesis to obtain mTcUBP1 and mTcUBP2 recombinant GST fusion proteins using the primers listed in supplemental Table S1. All constructs were transformed in Escherichia coli strain DH5αF′Iq. Cultures were induced with 0.2 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 3 h at 37 °C. Recombinant proteins were purified using GST-agarose columns (Sigma). Dihydrazide-agarose RNA cross-linking was performed as described (7). Purified proteins were incubated with RNA cross-linked beads for 1 h at room temperature and washed extensively. Elution was done with 2× Laemmli buffer. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining.

RESULTS

Stress-mediated Nuclear Accumulation of TcUBP1

Cytoplasmic mRNA granules in T. cruzi and T. brucei insect forms contain proteins involved in mRNA metabolism, including RRM-type RBPs such as TcUBP1 and TcPABP1. These structures are likely to have a similar role to mammalian stress granules protecting transcripts from degradation during stress (14). In mammalian cells, arsenite stress has been widely used for the induction of stress granule assembly (39). We tested if this potent oxidative agent also promotes granule formation in T. cruzi, involving the aforementioned proteins. We found that arsenite treatment did not induce cytoplasmic granules in culture epimastigotes, but after 4 h of treatment made TcUBP1 and TcUBP2 GFP fusion proteins accumulate in the nucleus (Fig. 1A). The nuclear/cytoplasmic fluorescence ratio changed from ∼0.7 to over 2 during stress for these two proteins (Fig. 1B). This was not the case for TcPABP1-GFP or GFP alone, which had no change in localization compared with untreated parasites (Fig. 1). Similar results were observed when endogenous TcUBP1 was analyzed in wild-type parasites by immunofluorescence using a specific antibody (11) (supplemental Fig. S1), showing the same localization as the GFP fusion protein in transfected parasites. The cytoplasmic localization and arsenite-induced nuclear accumulation of TcUBP1-GFP was evidenced throughout the culture of parasites (supplemental Fig. S1B). Thus, TcUBP1-GFP fusion is a valuable tool for studying its nuclear localization.

By using confocal microscopy, we found a fraction of TcUBP1-GFP in the nucleus of transfected T. cruzi epimastigotes under steady state conditions (Fig. 2A). A similar distribution was recorded for TcUBP2 (Fig. 2A) and other members of the TcRBP family such as TcRBP3, TcRBP4, TcRBP5a, and TcRBP6b (supplemental Fig. S2A). This is not a general phenomenon as TcPABP1 is cytoplasmic under the same experimental setup (Fig. 2A).

To gain insight into the kinetics of TcUBP1 nuclear accumulation, we analyzed localization of the protein at several time points during arsenite treatment (2 mm) in the presence of cycloheximide to inhibit new protein synthesis. We found that TcUBP1 nuclear accumulation is not a fast phenomenon, but rather a gradual process. TcUBP1 can already be observed in the nucleus 1 h after the addition of arsenite, and it takes 3 to 4 h to obtain the nuclear phenotype (Fig. 2B), which was synchronous throughout the population (not shown). Additionally, we analyzed the recovery of TcUBP1 from arsenite stress. In this experiment the culture of parasites was incubated with 2 mm arsenite for 3 h, time that is long enough to accumulate the protein in the nucleus (Fig. 2B). After that, parasites were washed three times with fresh medium containing cycloheximide to inhibit new protein synthesis, and were recovered for 5 h in fresh medium plus cycloheximide. Fig. 2C shows that, after 4 h, TcUBP1 exits the nucleus in 70% of the transfected parasites, having a nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio of 1.3. The remaining parasites showed no recovery (ratio = 2, not shown). By 5 h, the same percentage of parasites showed a nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio of 1, whereas the ratio of the remaining parasites was 1.8 (not shown). Additionally, recovery from mild arsenite stress (0.5 mm, enough to accumulate part of the protein in the nucleus) after 5 h in the presence of cycloheximide, showed cytoplasmic localization of TcUBP1 indistinguishable from untreated parasites (Fig. 2D). Recovered parasites showed the same overall morphology and motility of untreated parasites, suggesting that viability was not compromised (not shown).

It should be pointed out that pTEX-eGFP vector-derived expression yielded similar levels as endogenous proteins (supplemental Fig. S2B) and GFP fusion proteins display very similar biochemical properties to those of endogenous ones (14). Also, the amount of TcUBP1, TcUBP2, or other proteins did not vary during arsenite treatment (supplemental Fig. S2C). GFP alone was distributed evenly throughout the cell because its small size allows passive diffusion though the NPC (supplemental Fig. S2A).

The nuclear accumulation of TcUBP1 and TcUBP2 in transfected parasites was confirmed by confocal microscopy (supplemental Fig. S3). TcRBP6b also showed nuclear localization very similar to TcUBP1 (supplemental Fig. S4). TcRBP3 and TcRBP4 had less nuclear accumulation although clearly visible, whereas TcRBP5a had only mild nuclear accumulation (supplemental Fig. S4). From the analysis of other mRNA metabolism-related proteins under arsenite stress, only TceIF4E.1, a cytoplasmic mRNA 5′-cap binding protein, showed mild nuclear accumulation (supplemental Fig. S5). In summary, these results support the shuttling nature of TcUBP1, and accumulation in the nucleus under stress.

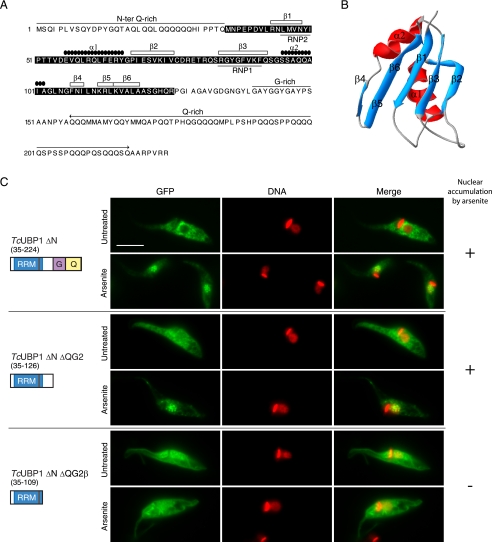

TcUBP1 RRM Is the Motif Allowing Nuclear Accumulation under Stress Conditions

Even though TcUBP1 and TcUBP2 could enter the trypanosome nucleus, none of these proteins is predicted to display a canonical monopartite or bipartite NLS when analyzed by PSORT II prediction or the PredictNLS server (40). TcUBP1 displays modular architecture (Fig. 3A), with a central RRM adopting the characteristic βαββαβ-fold (41), an amino-terminal Gln-rich region, and additional carboxyl terminus Gly- and Gln-rich regions (Fig. 3B). To track down the sequence determinants involved in nuclear import, we performed a deletion analysis on TcUBP1 and fused each fragment to GFP. Of 10 deletion mutants analyzed, none displayed nuclear accumulation in untreated parasites (Fig. 3C and supplemental Fig. S6). However, the mutant lacking the amino-terminal Gln-rich region (TcUBP1 ΔN) showed the same localization as the full-length TcUBP1 in untreated and arsenite-treated parasites, showing that the NH2 terminus is dispensable for its nuclear accumulation (Fig. 3C). On the other hand, deletion of the COOH-terminal Gln and/or Gly-rich regions rendered fusion proteins with an increase in nuclear abundance in untreated parasites, and still could accumulate in the nucleus of arsenite-treated parasites (Fig. 3C and supplemental Fig. S6). Similar results were obtained with the TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2 protein, which contains exclusively the 92-amino acids long RRM (Fig. 3C), and is the minimal portion of the protein with RNA binding activity (11) capable of being recruited to mRNA granules in starved parasites (14). Further deletion of the β5 and β6 strands of the RRM in the TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2β mutant gave a protein evenly distributed in the nucleus and the cytoplasm in untreated parasites. More important, this construct is neither accumulated in the nucleus of parasites treated with arsenite (Fig. 3C), nor capable to co-localize with mRNA granules in starved parasites (supplemental Fig. S7A). It should be mentioned that TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2 and TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2β proteins are below the size exclusion limit for the NPC, thus are allowed into the nucleus by passive diffusion. Altogether, these results narrow to the RRM the sequence determinant responsible for arsenite-induced nuclear accumulation.

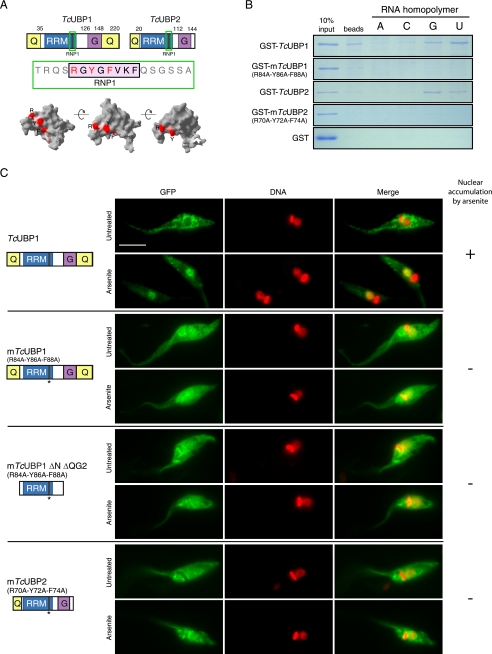

FIGURE 3.

TcUBP1 RRM mediates arsenite-induced nuclear accumulation. A, primary and secondary structure of TcUBP1. The RRM is shown boxed in black. Secondary structure elements, Gln and Gly-rich regions, and RNP1 and RNP2 are indicated. B, ribbon diagram of amino acids 41 to 120 of TcUBP1 comprising the RRM, based on NMR structural data. Secondary structure elements are indicated. β5 and β6 strands are shown together. C, localization of different TcUBP1 deletion mutants expressed as GFP fusion proteins in untreated and arsenite-treated (2 mm, 4 h) transfected parasites. Mutant protein names and a scheme of the domains fused to GFP are shown on the left side of the respective images. Numbers in parentheses indicate the amino acid residues fused to GFP. DNA was stained with DAPI, and is shown in red for better contrast. The column on the right summarizes if the fusion protein accumulates (+) or not (−) in the nucleus of the parasites under arsenite treatment. Scale bar, 5 μm.

TcUBP1 RRM Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling Is Coupled to RNA Binding

Given that arsenite-induced nuclear accumulation of TcUBP1 maps to the RRM motif, involved in RNA recognition, we wondered if these two properties were somehow interconnected. To address this issue, we performed site-directed mutagenesis on specific amino acids of the canonical RNP1 octapeptide of TcUBP1 and TcUBP2 RRMs that likely make stacking interactions with the RNA substrate, as suggested by structural data (41). A scheme of TcUBP1- and TcUBP2-mutated residues in the RNP1, and their position in a three-dimensional representation of the RRM is shown in Fig. 4A. RNA binding ability of the mutated proteins (mTcUBP1 and mTcUBP2) was evaluated by in vitro RNA homopolymer pull-down assays using recombinant GST fusion proteins. As reported earlier (7), control TcUBP1 and TcUBP2 wild-type constructs showed similar specificity, preferentially binding poly(U) and poly(G) tracts (Fig. 4B). However, mTcUBP1 and mTcUBP2 did not bind to any of the homoribopolymers tested, as it was also the case for GST (Fig. 4B). Upon parasite transfection, mTcUBP1, mTcUBP2, and a mutant version of TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2 (mutant RRM) fused to GFP were found evenly distributed in the nucleus and cytoplasm in untreated parasites (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, none of these mutants showed nuclear accumulation under arsenite stress conditions (Fig. 4C) or co-localization with mRNA granules in starved parasites (supplemental Fig. S7A). Proper expression and lack of significant in vivo degradation of these mutants was assessed by Western blotting (supplemental Fig. S7B).

FIGURE 4.

RNP1 mutations affect RNA binding and arsenite-induced nuclear accumulation. A, TcUBP1 and TcUBP2 protein schemes showing the RRM and accessory domains. The fragment containing the RNP1 peptide is shown in green and the amino acids mutated to alanine in mTcUBP1, mTcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2, and mTcUBP2 are shown in red (R, Y, F). Different views of TcUBP1 RRM based on NMR spectroscopy data showing the RNP1 peptide with the mutated amino acids in red are indicated. Structure analysis was performed using Swiss-Pdb Viewer version 3.7 using TcUBP1 RRM as input (Protein Data Bank code 1U6F). B, RNA homopolymer binding specificity of TcUBP1, mTcUBP1, TcUBP2, and mTcUBP2. Proteins were synthesized as recombinant GST fusions and incubated with dihydrazide-agarose beads alone (beads) or cross-linked to homoribopolymers (A, C, G, or U). After washing and elution, SDS-PAGE was performed, and the gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. C, localization of TcUBP1, mTcUBP1, mTcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2, and mTcUBP2 as GFP fusion proteins in untreated and arsenite-treated (2 mm, 4 h) transfected parasites. Protein names and a scheme of the protein fused to GFP are shown on the left side of the respective images. Numbers in parentheses indicate the amino acid residues mutated to alanine (parental numeration). TcUBP1 is shown for comparison with mutants. DNA was stained with DAPI, and is shown in red for better contrast. The column on the right summarizes if the fusion protein accumulates (+) or not (−) in the nucleus of the parasites under arsenite treatment. Scale bar, 5 μm.

To further determine whether TcUBP1 RRM nuclear uptake is a result of active transport, or passive diffusion and retention in the nucleus, we fused TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2, TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2β, and mTcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2 to GFP and β-Gal. These protein constructs would not passively diffuse through the NPC due to a restriction in size. As expected, all three constructs were localized to the cytoplasm in untreated parasites (Fig. 5A). Nevertheless, the TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP-βGal construct could still accumulate in the nucleus of arsenite-treated parasites, showing an increase in nuclear/cytoplasmic fluorescence from 0.56 to 1.28, whereas the other two mutated RRMs fused to GFP-βGal remained in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5A). Nuclear/cytoplasmic fluorescence ratios from the parasites in this experiment showed a statistically significant difference only for TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP-βGal, as it happened with TcUBP1-GFP or TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP from previous experiments (Fig. 5B). Non-functional RRMs fused to GFP (TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2β and mTcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2) showed similar nuclear/cytoplasmic ratios to that of GFP in untreated or arsenite-treated parasites. β-Gal fusion proteins had overall reduced ratios because these constructs cannot diffuse passively into the nucleus (Fig. 5B). It is to be mentioned that the β-Gal fusion proteins had some tendency to form aggregates, which could explain the patchy localization of all constructs, and the partial nuclear localization of the TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP-βGal chimera. Western blot of whole extracts from these transfected parasites with an anti-GFP antibody show that the molecular mass of the chimeras were the ones expected, and no degradation that could give a false result due to truncated forms was detected (supplemental Fig. S8A). TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP-βGal could still colocalize with mRNA granules, showing that the addition of β-Gal does not impair the function of the RRM (supplemental Fig. S8B). Fig. 6 shows a comparison of the results obtained with the most significant deletion mutants and constructs analyzed, regarding localization, nuclear accumulation under arsenite stress, mRNA granule association, and RNA binding. To sum up, these results show the ability of this trypanosomal RRM to perform as an NLS under arsenite stress.

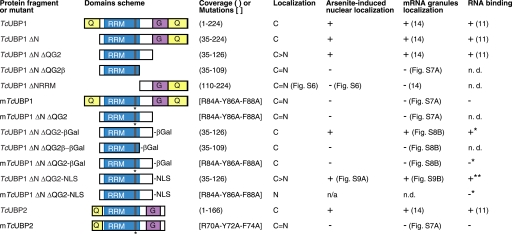

FIGURE 6.

TcUBP1 RRM couples arsenite-induced nuclear accumulation, mRNA granule association, and RNA binding capacity. A scheme of the domains (not to scale) of the most relevant constructs used for determining the sequences required for nuclear shuttling are shown. Coverage is shown in parentheses and mutated residues are shown in brackets. Localization is referred to untreated parasites grown in culture. Arsenite-induced nuclear localization, mRNA granules localization, and RNA binding in vitro are also summarized. C, cytoplasmic, C > N, more cytoplasmic than nuclear; C = N, even in cytoplasm and nucleus. Asterisk (*) is referred to the RNA binding capacity of the protein without the β-Gal moiety. Double asterisk (**) is referred to the RNA binding capacity of the protein without the NLS. N.D., not determined. n/a, not applicable.

Nuclear Export of TcUBP1 RRM

Under normal conditions TcUBP1 is cytoplasmic (Fig. 1A), with a small fraction residing in the nucleus (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, RNP1-mutated forms of TcUBP1 and TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2 are evenly distributed in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 4C), most probably due to passive diffusion (see above). These observations suggest that the RNA binding activity of the RRM could be involved in nuclear export of TcUBP1 under normal conditions. To answer this, we fused TcUBP1 RRM to GFP and a functional NLS, derived from the nuclear TcLA protein (14), that is almost identical to the characterized NLS in the T. brucei LA protein (34). A control GFP-NLS construct localized to the nucleus in untreated parasites, as expected (Fig. 5C). The TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP-NLS was not nuclear, and showed the same localization as the protein without the NLS (compare images in Figs. 3C and 5C). When the RNP1 mutations that abolish RNA binding were introduced into this same construct, the mTcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP-NLS protein adopted nuclear localization (Fig. 5C). In this case, these two constructs have the same configuration and background, with the only difference that TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP-NLS can bind to RNA. As a control of functionality, TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP-NLS was shown to accumulate in the nucleus under arsenite stress, and localize to mRNA granules under starvation (supplemental Fig. S9, A and B, respectively). These results suggest that RNA binding in TcUBP1 RRM is important for nuclear export and cytoplasmic localization of the protein.

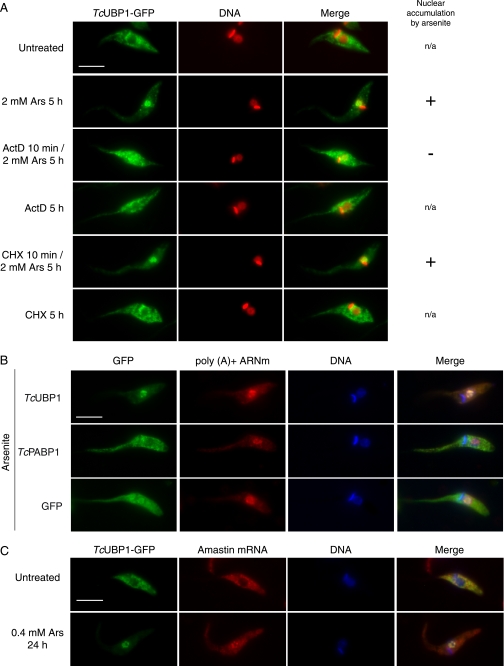

TcUBP1 Nuclear Accumulation Is Dependent on Active Transcription

We next investigated whether TcUBP1 nuclear accumulation was affected by inhibiting transcription with ActD, because a large amount of RBPs have a transcription-dependent nuclear localization (see “Discussion”). Treatment of cells with ActD 10 min before the addition of sodium arsenite and incubating both drugs for 5 h did not induce the nuclear accumulation of TcUBP1-GFP (Fig. 7A). As a positive control, treatment with arsenite alone showed complete nuclear accumulation of TcUBP1-GFP (Fig. 7A). ActD alone had no effect on protein localization, and co-incubation of cycloheximide (CHX) and arsenite did not alter the nuclear phenotype previously seen with arsenite alone (Fig. 7A). These results show that TcUBP1 nuclear accumulation is abolished by a blockade in transcription and not by a general shut down in gene expression.

FIGURE 7.

Transcription-dependent nuclear accumulation of TcUBP1 and colocalization with mRNA. A, active transcription is required for TcUBP1 arsenite-induced nuclear accumulation. The localization of TcUBP1-GFP is shown in transfected parasites treated according to the left column. When ActD or cycloheximide (CHX) were combined with arsenite, the inhibitors were added 10 min before the addition of arsenite. DNA was stained with DAPI, and is shown in red for better contrast. The column on the right summarizes if the fusion protein accumulates (+) or not (−) in the nucleus of the parasites under arsenite treatment when applicable. n/a, not applicable. B, nuclear accumulation of poly(A)+ mRNA with TcUBP1 but not TcPABP1. The localization of the respective proteins fused to GFP is shown in arsenite-treated (0.4 mm, 24 h) transfected parasites. C, colocalization of TcUBP1 with amastin mRNA, a target transcript. Localization of amastin mRNA by FISH with a DIG-labeled RNA antisense probe in untreated and arsenite-treated (0.4 mm, 24 h) TcUBP1-GFP transfected parasites. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Additionally, ActD and CHX were added for 5 h to TcUBP1-GFP-transfected parasites previously subjected to mild arsenite stress (supplemental Fig. S10A). Here, the inhibitors are added when TcUBP1 is already nuclear, and arsenite is not washed out. In this experiment, all protein recovered the cytoplasmic localization, whereas the same treatment without ActD makes TcUBP1 even more nuclear (supplemental Fig. S10A). This same experiment was performed with the TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2 deletion mutant and behaved the same way as the full-length protein (supplemental Fig. S10B). Altogether, these results show that transcription is required for TcUBP1 RRM-mediated nuclear accumulation.

TcUBP1 Colocalizes with mRNA within the Nucleus

The fact that only the functional RRM of TcUBP1 is required for arsenite-induced transcription-dependent nuclear localization made us wonder whether this protein could be accumulating together with mRNA in the nucleus. When we used a lower concentration of arsenite (0.4 mm) for 24 h, bulk poly(A)+ mRNA accumulated in discrete nuclear foci together with TcUBP1-GFP (Fig. 7B). This phenomenon was also observed in TcPABP1-GFP and GFP-transfected parasites, implying that it is not caused by transfected TcUBP1-GFP. We also analyzed the localization of amastin mRNA, a target transcript that can be bound both in vitro and in vivo by TcUBP1 (7). Amastin transcript colocalized with TcUBP1 in the nucleus of parasites treated with 0.4 mm arsenite for 24 h when detected with a DIG-labeled antisense RNA probe (Fig. 7C). RNA FISH with an amastin DIG-labeled sense RNA probe was used as a negative control (supplemental Fig. S11). We concluded that, under conditions leading to TcUBP1 nuclear accumulation, the protein could be close to specific mRNA targets such as amastin.

DISCUSSION

In eukaryotic cells, the coordinated nuclear entry and exit of factors regulating biological processes is crucial to maintain homeostasis. However, cell stress can affect the balance of molecules at both sides of the nuclear envelope. In this work we describe the nucleocytoplasmic transport of a well known cytoplasmic RRM-type RBP from T. cruzi, TcUBP1. The potent cellular stressor sodium arsenite induced nuclear accumulation of TcUBP1, TcUBP2, and TcRBP6b, whereas the remaining members of this family showed mild nuclear accumulation. After stress induction, TcUBP1 gradually accumulates in the nucleus. The time needed to fully accumulate this protein in the nucleus is relatively high (3–4 h), and does not correlate with a fast response to stress. It seems more likely that cytoplasmic TcUBP1 and TcUBP2 are recycled transiently to the nucleus and under stress are retained there and accumulated. TceIF4E.1 also showed an increase in nuclear abundance under stress. The mammalian ortholog is known to shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm in mammals (42), and to accumulate in the nucleus under stress (43). Nevertheless, nuclear accumulation under arsenite treatment was not shared by other mRNA metabolism-related proteins.

TIA-1 and TIAR are nuclear proteins composed of three RRMs, of which RRM2 plus its COOH-terminal auxiliary domain are needed for nuclear accumulation (23). Similarly to TcUBP1, the disruption of TIAR RNA binding activity by point mutations in either RNP2 or RNP1 impairs nuclear accumulation (23). Although several of the mutated residues in TIAR are solvent exposed and suggested to interact with RNA, some are buried in the hydrophobic protein interior and might interfere with protein folding (44). This observation suggests that a properly folder RRM2 is necessary for nuclear shuttling, instead of the ability to bind RNA. In our case, the selected TcUBP1 RNP1-mutated residues were chosen based on the available TcUBP1 RRM structure and the modeled TcUBP1 RRM-RNA complex (41). These residues are solvent exposed and suggested to make stacking interactions with the substrate RNA (41). These mutations affected RNA binding of TcUBP1 and TcUBP2, and also localization, because these mutants were distributed throughout the cell in all tested conditions. The alternative elimination of the β5 and β6 strands also altered localization, supposedly by affecting the domain structure and function. Therefore, intact RRM and RNA binding capabilities are likely required for nuclear accumulation, because it was not possible to uncouple these two activities. This conclusion gives RNA binding in TcUBP1 a new twist toward protein localization. Recent evidence shows that the binding of short Y RNAs by the RNA quality control protein Ro, favors cytoplasmic localization of the protein by masking an NLS. Consequently, a Ro mutant without Y RNA binding capability accumulates in nuclei (45). Similarly, human ADAR1 localization can be modulated by RNA binding. The interaction of double strand RNA with double strand RNA-binding domain 3 abolishes transportin 1 association with ADAR1 and therefore nuclear import (46). Hence, the interplay between RNA binding and nucleocytoplasmic shuttling is emerging.

The nuclear fluorescence observed in the evenly distributed RNP1 mutant and deletion proteins seems to be caused by passive diffusion. In fact, TcUBP1-GFP has similar mass (∼55 kDa) as a double GFP construct shown to localize uniformly in the nucleus and cytoplasm of mammalian cells (47). This implies that it is not the mass of a protein but rather its diameter which restricts passive diffusion. Actually, changing the size and mass of these constructs by the addition of β-Gal restored cytoplasmic localization in untreated parasites. However, the TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP-βGal construct, with an intact RRM, could still enter the nucleus and partially accumulate under arsenite treatment. Thus, this RRM is actively transported into the nucleus under stress. Even so, under normal conditions, this same RRM can retain most of the TcUBP1 ΔN ΔQG2-GFP-NLS construct in the cytoplasm. The fact that only the RRM able to bind to RNA, and not the mutated one, could overcome the nuclear localization imposed by the TcLA NLS could suggest that TcUBP1 might be exported from the nucleus as a cargo bound to mRNA.

Transcription inhibition has been shown to impair nuclear localization of several proteins such as heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (24), HuR (25), SF2/ASF (48), TIA-1 and TIAR (23), and other RNA metabolism-related proteins. In the case of TcUBP1, nuclear accumulation under stress was abolished when transcription was inhibited. In addition, nuclear-accumulated TcUBP1 under mild stress recovered cytoplasmic localization when ActD was added. The export of the protein under these circumstances depended on the RRM. Thus, in stressed parasites, TcUBP1 RRM behaves like the transcription-dependent nuclear proteins mentioned earlier. The availability of newly synthesized nuclear transcripts might also be necessary for nuclear accumulation. The mechanism for transcription-dependent nuclear localization of this group of proteins has so far eluded identification. Nevertheless, accelerated export, rather than impairment of nuclear import, has been proposed for cytoplasmic relocation of nuclear proteins when transcription is inhibited (49).

TcUBP1 and poly(A)+ mRNA, or amastin transcripts, were found to colocalize in nuclear foci in parasites submitted to arsenite. It is tempting to speculate that under normal conditions the amount of TcUBP1 and mRNAs in the nucleus might be scarce and rapidly exported to the cytoplasm, thus, can only be detected when accumulating under stress conditions.

In summary, we present evidence of an RRM that is recognized as a nuclear localization determinant, and also involved in the export of TcUBP1 from the nucleus. The tight relationship between RNA binding and moving across the nuclear envelope was so far impossible to separate without affecting each other. Our results support the possible association of TcUBP1 with mRNA targets in the nucleus, and trafficking across NPCs. These biological functions can be linked with those activities of TcUBP1 in the cytoplasm of the parasite: transcript turnover and mRNA granules formation. Future work will determine the import adapter associated to TcUBP1 RRM during nuclear translocation, to better understand non-classical NLS in an early branching eukaryote. The knowledge of the steps from mRNA biogenesis in the nucleus to its translation and/or destruction in the cytoplasm is important in trypanosomatids, because these agents of diseases affecting millions of people worldwide make use exclusively of post-transcriptional mechanisms to regulate gene expression.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Berta Franke de Cazzulo, Liliana Sferco, and Agustina Chidichimo for parasite cultures, and Carlos Buscaglia, Javier De Gaudenzi, and Griselda Noé for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank J. M. Kelly for providing pTEX-eGFP and pTEX-eGFPs vectors, and Iván D'Orso for pRibotex-GFP constructs. We thank Javier De Gaudenzi for help with in vitro homoribopolymer binding assays and Flavia Barbano for help with pTEX-eGFP-NLS vector construct.

This work was supported by grants from the Agencia Nacional de Promocion Cientifica y Tecnologica (ANPCyT, Argentina) (to A. C. F.) and an International Research Scholars Grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to A. C. F.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S11 and Tables S1–S3.

- RBP

- RNA-binding protein

- UTR

- untranslated region

- RRM

- RNA recognition motif

- RNP

- ribonucleoprotein

- NPC

- nuclear pore complex

- NLS

- nuclear localization signal

- β-Gal

- β-galactosidase

- ActD

- actinomycin D

- CHX

- cycloheximide

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- FISH

- fluorescence in situ hybridization

- eGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- DIG

- digoxigenin

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrett M. P., Burchmore R. J., Stich A., Lazzari J. O., Frasch A. C., Cazzulo J. J., Krishna S. (2003) Lancet 362, 1469–1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clayton C. E. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 1881–1888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Orso I., De Gaudenzi J. G., Frasch A. C. (2003) Trends Parasitol. 19, 151–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang X. H., Haritan A., Uliel S., Michaeli S. (2003) Eukaryot. Cell 2, 830–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayton C., Shapira M. (2007) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 156, 93–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Gaudenzi J., Frasch A. C., Clayton C. (2005) Eukaryot. Cell 4, 2106–2114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Gaudenzi J. G., D'Orso I., Frasch A. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 18884–18894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cléry A., Blatter M., Allain F. H. (2008) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18, 290–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreyfuss G., Kim V. N., Kataoka N. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 195–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Orso I., Frasch A. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34801–34809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Orso I., Frasch A. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50520–50528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noé G., De Gaudenzi J. G., Frasch A. C. (2008) BMC Mol. Biol. 9, 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartmann C., Benz C., Brems S., Ellis L., Luu V. D., Stewart M., D'Orso I., Busold C., Fellenberg K., Frasch A. C., Carrington M., Hoheisel J., Clayton C. E. (2007) Eukaryot. Cell 6, 1964–1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassola A., De Gaudenzi J. G., Frasch A. C. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 65, 655–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terry L. J., Shows E. B., Wente S. R. (2007) Science 318, 1412–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Köhler A., Hurt E. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 761–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weis K. (2002) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 328–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lange A., Mills R. E., Lange C. J., Stewart M., Devine S. E., Corbett A. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5101–5105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weis K. (1998) Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 185–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakielny S., Dreyfuss G. (1999) Cell 99, 677–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afonina E., Stauber R., Pavlakis G. N. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 13015–13021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brune C., Munchel S. E., Fischer N., Podtelejnikov A. V., Weis K. (2005) RNA 11, 517–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang T., Delestienne N., Huez G., Kruys V., Gueydan C. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118, 5453–5463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piñol-Roma S., Dreyfuss G. (1991) Science 253, 312–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng S. S., Chen C. Y., Xu N., Shyu A. B. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 3461–3470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutten S., Kehlenbach R. H. (2007) Trends Cell Biol. 17, 193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuevas I. C., Frasch A. C., D'Orso I. (2005) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 139, 15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei E. P., Silver P. A. (2002) Dev. Cell 2, 261–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ivens A. C., Peacock C. S., Worthey E. A., Murphy L., Aggarwal G., Berriman M., Sisk E., Rajandream M. A., Adlem E., Aert R., Anupama A., Apostolou Z., Attipoe P., Bason N., Bauser C., Beck A., Beverley S. M., Bianchettin G., Borzym K., Bothe G., Bruschi C. V., Collins M., Cadag E., Ciarloni L., Clayton C., Coulson R. M., Cronin A., Cruz A. K., Davies R. M., De Gaudenzi J., Dobson D. E., Duesterhoeft A., Fazelina G., Fosker N., Frasch A. C., Fraser A., Fuchs M., Gabel C., Goble A., Goffeau A., Harris D., Hertz-Fowler C., Hilbert H., Horn D., Huang Y., Klages S., Knights A., Kube M., Larke N., Litvin L., Lord A., Louie T., Marra M., Masuy D., Matthews K., Michaeli S., Mottram J. C., Müller-Auer S., Munden H., Nelson S., Norbertczak H., Oliver K., O'neil S., Pentony M., Pohl T. M., Price C., Purnelle B., Quail M. A., Rabbinowitsch E., Reinhardt R., Rieger M., Rinta J., Robben J., Robertson L., Ruiz J. C., Rutter S., Saunders D., Schäfer M., Schein J., Schwartz D. C., Seeger K., Seyler A., Sharp S., Shin H., Sivam D., Squares R., Squares S., Tosato V., Vogt C., Volckaert G., Wambutt R., Warren T., Wedler H., Woodward J., Zhou S., Zimmermann W., Smith D. F., Blackwell J. M., Stuart K. D., Barrell B., Myler P. J. (2005) Science 309, 436–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conti E., Izaurralde E. (2001) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 310–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reed R., Magni K. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, E201–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hellman K., Prohaska K., Williams N. (2007) Eukaryot. Cell 6, 2206–2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoek M., Engstler M., Cross G. A. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 3959–3968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marchetti M. A., Tschudi C., Kwon H., Wolin S. L., Ullu E. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 899–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson S. R., Meyer D. J., Taylor M. C., Bromley E. V., Miles M. A., Kelly J. M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17062–17071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becker A., Schmidt M., Jäger W., Pühler A. (1995) Gene 162, 37–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Noia J. M., D'Orso I., Sáanchez D. O., Frasch A. C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10218–10227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jäger A. V., De Gaudenzi J. G., Cassola A., D'Orso I., Frasch A. C. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 2035–2042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kedersha N., Anderson P. (2007) Methods Enzymol. 431, 61–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cokol M., Nair R., Rost B. (2000) EMBO Rep. 1, 411–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Volpon L., D'Orso I., Young C. R., Frasch A. C., Gehring K. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 3708–3717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dostie J., Ferraiuolo M., Pause A., Adam S. A., Sonenberg N. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 3142–3156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rong L., Livingstone M., Sukarieh R., Petroulakis E., Gingras A. C., Crosby K., Smith B., Polakiewicz R. D., Pelletier J., Ferraiuolo M. A., Sonenberg N. (2008) RNA 14, 1318–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar A. O., Swenson M. C., Benning M. M., Kielkopf C. L. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 367, 813–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sim S., Weinberg D. E., Fuchs G., Choi K., Chung J., Wolin S. L. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 1555–1564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fritz J., Strehblow A., Taschner A., Schopoff S., Pasierbek P., Jantsch M. F. (2009) Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 1487–1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cardarelli F., Serresi M., Bizzarri R., Giacca M., Beltram F. (2007) Mol. Ther. 15, 1313–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cáceres J. F., Screaton G. R., Krainer A. R. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 55–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lichtenstein M., Guo W., Tartakoff A. M. (2001) Traffic 2, 261–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]