Abstract

Protein evolution is constrained by folding efficiency (“foldability”) and the implicit threat of toxic misfolding. A model is provided by proinsulin, whose misfolding is associated with β-cell dysfunction and diabetes mellitus. An insulin analogue containing a subtle core substitution (LeuA16 → Val) is biologically active, and its crystal structure recapitulates that of the wild-type protein. As a seeming paradox, however, ValA16 blocks both insulin chain combination and the in vitro refolding of proinsulin. Disulfide pairing in mammalian cell culture is likewise inefficient, leading to misfolding, endoplasmic reticular stress, and proteosome-mediated degradation. ValA16 destabilizes the native state and so presumably perturbs a partial fold that directs initial disulfide pairing. Substitutions elsewhere in the core similarly destabilize the native state but, unlike ValA16, preserve folding efficiency. We propose that LeuA16 stabilizes nonlocal interactions between nascent α-helices in the A- and B-domains to facilitate initial pairing of CysA20 and CysB19, thus surmounting their wide separation in sequence. Although ValA16 is likely to destabilize this proto-core, its structural effects are mitigated once folding is achieved. Classical studies of insulin chain combination in vitro have illuminated the impact of off-pathway reactions on the efficiency of native disulfide pairing. The capability of a polypeptide sequence to fold within the endoplasmic reticulum may likewise be influenced by kinetic or thermodynamic partitioning among on- and off-pathway disulfide intermediates. The properties of [ValA16]insulin and [ValA16]proinsulin demonstrate that essential contributions of conserved residues to folding may be inapparent once the native state is achieved.

Introduction

A fundamental problem in biophysics is posed by the efficiency of protein folding (1, 2). The capability of folding is an evolved property of biological sequences, i.e. not broadly representative of polypeptides as a class of heteropolymers (3). A funnel-shaped free-energy landscape enables an efficient conformational search leading by multiple trajectories to the native state (4–6). What distinguishes foldable from nonfoldable sequences (7), and how do productive trajectories avoid bottlenecks (8–10)? Despite the centrality of these questions, experimental approaches are limited. Here, we combine biophysical and cellular studies to identify a residue critical to the efficiency of oxidative folding. A model is provided by insulin, a globular protein central to the regulation of vertebrate metabolism (11).

The insulin gene encodes a single-chain precursor, preproinsulin (Fig. 1A, top) (12). A signal peptide (Fig. 1A, gray bar) is cleaved on translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)5 to yield proinsulin. The precursor contains successive sequence motifs, defining a B-domain (Fig. 1A, blue bar), connecting domain (black bar), and A-domain (red bar) (13). The translocated polypeptide is reduced and unfolded. Biophysical studies suggest that folding in the ER yields a well organized A-B (insulin-like) core and disordered C-domain (Fig. 1B, dashed black segment) (14–19). Folding of proinsulin is coupled to disulfide pairing (Fig. 1, A and B, gold A6–A11, A7–B7, and A20–B19). Two cystines provide interior struts (A20–B19 and A6–A11), whereas the third forms an external staple (A7–B7). These structural elements are required for stability and activity (20–29). Insulin disulfide isomers exhibit molten structures of marginal stability and low activity (30–32). Proinsulin isomers have been observed at low concentration in β-cells (33), and their accumulation may be linked to β-cell dysfunction (34, 35). Misfolding of proinsulin variants is associated with non-native aggregation, leading to β-cell dysfunction and in turn diabetes mellitus (36–39).

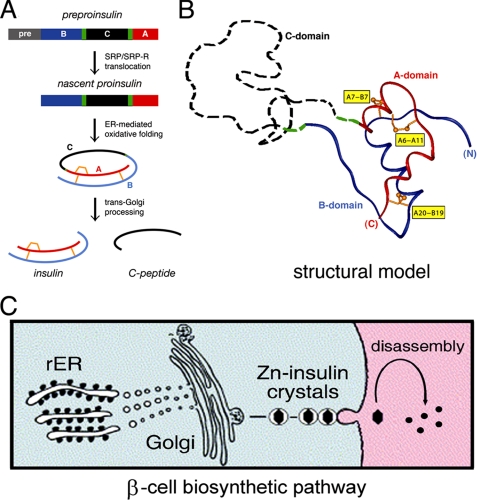

FIGURE 1.

Proinsulin and its biosynthetic pathway. A, pathway of insulin biosynthesis beginning with preproinsulin (top): signal peptide (gray), B-domain (blue), dibasic BC junction (green), C-domain (black), dibasic CA junction (green), and A-domain (red). In the ER the unfolded prohormone undergoes specific disulfide pairing to yield native proinsulin (middle panels). Cleavage of BC and CA junctions (by prohormone convertases PC1 and PC2 and by carboxypeptidase E) leads to mature insulin and the C-peptide (bottom). B, structural model of insulin-like moiety and disordered connecting peptide (dashed line). The A- and B-domains are shown in red and blue, respectively; the disordered connecting domain is shown in dashed black line. Cystines are labeled in yellow boxes. C, cellular pathway of insulin biosynthesis: nascent proinsulin folds as a monomer in ER (left) wherein zinc-ion concentration is low; in post-Golgi granules proinsulin is processed by cleavage of connecting peptide to yield mature insulin, and zinc-stabilized hexamers begin to assemble. Zinc-insulin crystals are observed in secretory granules. On secretion into the portal circulation (right), hexamers dissociated to yield bioactive insulin monomers. rER, rough endoplasmic reticulum; SRP, signal recognition particle.

Following the folding of proinsulin in the ER, the biosynthetic pathway of insulin imposes additional structural constraints. After transit through the Golgi apparatus and entry into immature secretory granules (40), a specific set of prohormone convertases proteolytically excises the C-peptide at conserved dibasic sites (BC and CA junctions; Fig. 1, A and B, green), liberating the bioactive hormone (41–43). Insulin thus contains two chains, A (21 residues) and B (30 residues), and is stored as Zn2+-stabilized hexamers within specialized secretory granules (Fig. 1C) (44). The hexamers dissociate upon secretion into the portal circulation, enabling the circulating hormone to function as a Zn2+-free monomer (Fig. 1C, right).

This study investigates a mutant proinsulin defective in folding and yet active and well organized once the native state is achieved. Substitution of LeuA16 by Val (45) reduces the efficiency of disulfide pairing in vitro and leads in mammalian cells to accelerated degradation associated with ER stress (46, 47). Despite these perturbations, the crystal structure of the variant (as a mutant insulin) is essentially identical to wild type (48, 49). We propose that ValA16 allows formation of off-pathway oxidative intermediates and/or destabilizes on-pathway intermediates (50). Such perturbations are similar to those proposed to underlie a newly recognized syndrome of toxic protein misfolding, permanent neonatal-onset diabetes mellitus (DM) due to mutations in proinsulin (36–39). Although to date clinical mutations (excluding insertion or removal of cysteines) have clustered in the B-domain, our results demonstrate that the A-domain is also required for efficient folding. The aberrant properties of [ValA16]proinsulin thus provide a model for the molecular genetics of a disease of protein misfolding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemical Synthesis

Insulin was provided by Eli Lilly and Co.; S-sulfonate B-chain derivatives were obtained by oxidative sulfitolysis (51). A- and B-chain analogues were otherwise prepared by solid-phase synthesis (51). Insulin analogues were prepared by chain combination as described previously (45). Predicted molecular masses were confirmed by mass spectrometry.

Recombinant Expression of Proteins

Wild-type and variant proinsulins were expressed in Escherichia coli (52); wild-type and variant mini-proinsulins (53-residue construct) were expressed in folded secreted form in Pichia pastoris (53).

Mammalian Cell Culture

HEK293T cells were cultured at 37 °C in high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.1% penicillin/streptomycin with 5% CO2. CHO-CLA14 cells were maintained in low glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 400 μg/ml G418 and 200 μg/ml hygromycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2 (54). For metabolic labeling, cells were plated into 6-well plates 1 day before transfection. Plasmid DNA (2 μg) was transfected into each well using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). For studies of the unfolded protein response (UPR), cells were seeded into 24-well plates 1 day before transfection. Plasmid DNAs containing proinsulin (wild type or variant) were co-transfected with plasmids (provided by R. Kaufman) encoding luciferase (driven by BiP promoter) and β-galactosidase (driven by CMV promoter) at 5:2:1 ratio using Lipofectamine; assays were performed in triplicate.

Metabolic Labeling and PAGE

At 40 h post-transfection, cells were preincubated in methionine/cysteine-deficient medium for 30 min, metabolically labeled in the same medium containing 35S-labeled Met and Cys for 1 h, washed once with complete medium, and chased for the indicated times. To examine degradation, labeled cells were chased for 4 h with or without 20 μm MG132 or lactacystin. After chase media were collected, cells were lysed in 100 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.2% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 10 mm EDTA, and 25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). Lysates and chase media were immunoprecipitated with guinea pig anti-insulin antiserum (LINCO Diagnostics, Inc.) and analyzed by Tris-Tricine/urea-SDS-PAGE under reducing and nonreducing conditions (33, 55).

UPR Assay and Statistical Analysis

The UPR assay (see supplemental Fig. S1 and supplemental Table S1) was performed as described previously (56). At 40 h post-transfection cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline, lysed in luciferase assay buffer, and transferred to a 96-well plate; luminometry was performed in a Turner Biosystems plate luminometer using the Dual-Light assay system (Applied Biosystems). Statistical analysis employed a randomized block design analysis of variance model after checking for appropriateness of a normality assumption on errors using a Q-Q plot with Wilk-Shapiro test. Testing (two-tailed) was done at a significance level of α = 0.05. When significant findings were discovered, a nonparametric version of analysis of variance was run to ensure consistency.

Spectroscopy

CD spectra, obtained using an Aviv spectropolarimeter equipped with a titration unit for denaturation studies, were measured at a protein concentration of 5 μm at 4 °C (57). 1H NMR spectra were obtained at 700 MHz in D2O solution at pH 7.0 and 25 °C (21).

Thermodynamic Modeling

CD-detected guanidine denaturation data (222 nm) were fitted by nonlinear least squares to a two-state model (supplemental Table S2) as described previously (58). In brief, CD data, θ(x), were fitted by a nonlinear least-squares program according to Equation 1,

|

where x is the concentration of guanidine hydrochloride, and where θA and θB are base-line values in the native and unfolded states. These base lines were approximated by pre- and post-transition lines θA(x) = θAH2O + mAx and θBH2O + mBx. Fitting the original CD data and base lines simultaneously circumvents artifacts associated with linear plots of DG as a function of denaturant according to ΔG0(x) = ΔGH2O0 + m0x (for reviews see Refs. 58, 59).

Crystallography

Crystals were grown by hanging-drop vapor diffusion with a 1:2.5 ratio of Zn2+ to protein monomer and 3.7:1 ratio of phenol to protein monomer (49). Drops consisted of 1 μl of protein solution (10 mg/ml in 0.02 m HCl) mixed with 1 μl of reservoir solution (0.02 m Tris-HCl, 0.05 m sodium citrate, 5% acetone, 0.03% phenol, and 0.01% zinc acetate (pH 8.0)). Crystals (space group R3) were obtained at room temperature after 2 weeks. Data were collected from single crystals flash-frozen to 100 K. Reflections from 22.58 to 1.8 Å were measured using synchrotron radiation (Chess, Cornell University). Data were processed with programs DENZO (version 1.9.6) and SCALEPACK (version 1.9.6). The structure was determined by molecular replacement using CNS; initial model was the wild-type TRf dimer (PDB identifier 1RWE) following removal of water, zinc, and chloride ions. A translation-function search was performed following rotation-function analysis of data between 15.0 and 4.0 Å. Rigid-body refinement using CNS, employing overall anisotropic temperature factors and bulk-solvent correction, yielded values of 0.31 and 0.30 for R and Rfree, respectively, for data between 19.2 and 3.0 Å resolution. Between refinement cycles, 2Fo − Fc and Fo − Fc maps were calculated using data to 3.0 Å resolution; zinc, chloride ions, and phenol molecules were built using O (60). Water molecules were calculated and checked using DDQ (61). The geometry was monitored with PROCHECK (62); zinc ions and water molecules were built as refinement proceeded. Further refinement employed CNS (63), which implements maximum-likelihood torsion-angle dynamics and conjugate-gradient refinement. Statistical data are provided in supplemental Table S3. Potential packing defects were calculated with Surfnet (64).

RESULTS

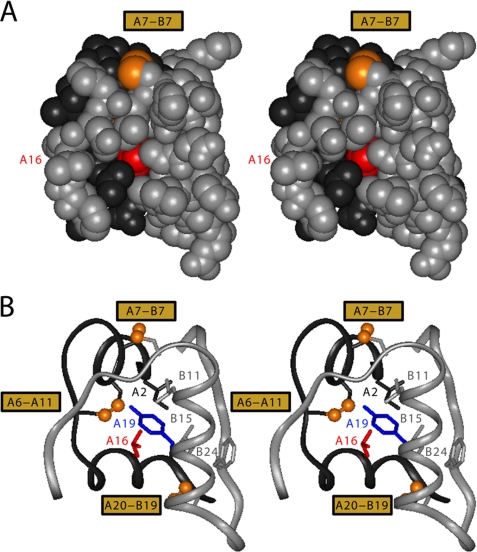

The hydrophobic core of insulin is conserved among vertebrates (12); the neighborhood of cystine A20–B19 is structurally invariant (48, 65, 66). Studies of insulin-related polypeptides have demonstrated the importance of cystine A20–B19 as a first step in disulfide pairing (67–69). LeuA16, inaccessible in the native state (Fig. 2A, red), adjoins TyrA19 and CysA20 (Fig. 2B, blue and gold, respectively) along the inner surface of the A12–A19 α-helix and projects between CysA11 and LeuB15 (gold and gray). Hydrophobic collapse of these side chains in the nascent polypeptide is proposed to orient CysA20 and CysB19 for initial pairing (20, 29, 57).

FIGURE 2.

Structural environment of LeuA16 in insulin monomer. A, stereo space-filling model showing limited exposure of internal A16 side chain (red) between B-chain (gray, overlying surface) and A-chain (black). The solvent-exposed A7–B7 disulfide bridge is shown in gold (top); internal cystines A6–A11 and A20–B19 are not visible. B, corresponding ribbon model in same orientation showing LeuA16 in relation to TyrA19 (blue) and the internal side chains of IleA2 (black), LeuB11 (gray), and LeuB15 (gray). The A and B main chains are shown as gray and black ribbons, respectively. The three disulfide bridges (labeled at left) are shown as gold spheres. Coordinates were obtained from 2-Zn insulin molecule 1 (Protein Data bank code 4INS).

ValA16 Impairs Insulin Chain Combination and Refolding of Proinsulin

Insulin chain combination provides a peptide model of proinsulin refolding (70). The reaction leads to native disulfide pairing, demonstrating that information required for proinsulin folding is contained within the A and B sequences (71). Yield is limited by off-pathway products under kinetic control (disulfide-linked cyclic A-chains, cyclic B-chains, B-chain dimers, and B-chain polymers). The robustness of chain combination to amino acid substitutions has enabled synthesis of hundreds of analogues in past decades. As an initial test of the importance of LeuA16 in disulfide pairing, we prepared a variant A-chain containing ValA16. Reactions employed 80 mg of wild-type A-chain and 40 mg of B-chain (each as S-sulfonate derivatives). Whereas this protocol ordinarily yields 8–9 mg of wild-type insulin (following purification by reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (51, 57, 72)), no product was detectable in three attempted reactions. Because the threshold of HPLC detection is <40 μg, the efficiency of chain combination was reduced by >200-fold.

Refolding of proinsulin is more efficient than chain combination (73). Accordingly, we sought to prepare ValA16-human proinsulin (position 81 of the polypeptide) by recombinant expression in E. coli. Bacterial expression gave rise to inclusion bodies containing reduced and unfolded proinsulin; following purification, oxidative refolding ordinarily yields native disulfide pairing (52, 74). Expression of wild-type and variant polypeptides within inclusion bodies achieved similar levels; the reduced polypeptides were purified in similar yield. Although refolding of wild-type proinsulin was robust (52), however, the yield of [ValA16]proinsulin was negligible. The refolding mixture gave rise to a broad and inhomogeneous HPLC elution profile, suggesting the presence of multiple products.

ValA16 Blocks the Cellular Folding of Proinsulin and Induces ER Stress

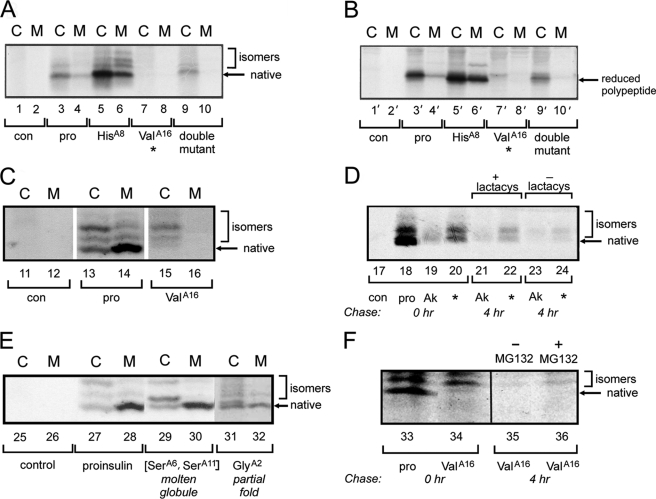

Cellular folding efficiencies of variant proinsulins were evaluated in CLA14 cells (a subclone of the Chinese hamster ovary cell line) (54) and in human cell line HEK293T. Following transfection, we examined expression, disulfide isomer formation, and secretion of newly synthesized proinsulin as radiolabeled with 35S-labeled amino acids for 1 h and chased for 4 h (Fig. 3, A–C). Denaturing PAGE (Tris-Tricine/urea-SDS-PAGE) in the absence of reduction (Fig. 3A) permitted examination of distinct proinsulin disulfide isomers as formed in the ER (33, 35); with reduction, this gel system provides a probe of total protein expression (Fig. 3B). The wild-type construct gave rise to robust expression, primarily of a fast migrating species; previous studies established that the latter is the native species (33). This species is efficiently secreted from transfected cells (Fig. 3, lane C) to medium (lane M). Two minor species are also present as slower migrating isomers with mispaired disulfide bonds; these exhibit lower secretion efficiency (Fig. 3, brackets). In CLA14 cells, substitution of LeuA16 by Val markedly impairs expression (relative to wild-type; Fig. 3, A and B, lanes 3 and 4 and 3′ and 4′) of the variant proinsulin in the ER (lanes 7 and 7′) and blocks its secretion (lanes 8 and 8′).

FIGURE 3.

Biosynthesis and degradation of proinsulin variants in cell culture. A and B, analysis of folding and secretability by Tris-Tricine/urea-SDS-PAGE under nonreducing (A, lanes 1–10) and reducing (B, lanes 1′–10′) conditions. CLA14 cells were transfected to express wild-type proinsulin (pro, lanes 3 and 4, 3′ and 4′) or variants ThrA8 → His (lanes 5 and 6, 5′ and 6′), LeuA16 → Val (lanes 7 and 8, 7′ and 8′), or both HisA8,ValA16 (lanes 9 and 10, 9′ and 10′). Lanes 1 and 2, 1′ and 2′ provide an empty-vector control (con). The A8 substitution enhances overall expression and secretion; secretion of non-native isomers is also increased. At 48 h, cells were pulse-labeled with 35S-labeled amino acids for 1 h and chased for 1 h. Chase media (M) were collected, and cells (C) were lysed; each fraction was immunoprecipitated with anti-insulin antiserum. Prior to transfections, 15 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside was added to induce the expression of ER chaperone ATF6 as described previously (54). C, corresponding pulse-chase studies in HEK293T cells as analyzed under nonreduced conditions (33). For ValA16 mutant (lanes 15 and 16, cellular (C) and medium (M)), a higher fraction of nascent polypeptide migrated as misfolded disulfide isomers relative to wild-type proinsulin (lanes 13 and 14); an empty-vector control is provided in lanes 11 and 12. D, effect of proteosome inhibitor lactacystin (lactacys) on intracellular proinsulin expression in transfected HEK293T cells expressing newly synthesized 35S-pulse-labeled wild-type proinsulin (pro, lane 18), diabetes-associated variant CysA7 → Tyr (Akita mutant (75); designated AK, lanes 19, 21 and 23), or ValA16 variant (lanes 20, 22 and 24); an empty-vector control is provided in lane 17. Cells were chased with or without 20 μm lactacystin for 4 h. Akita and ValA16 variants exhibit enhanced degradation relative to wild type, in each case partially blocked by the proteasome inhibitor. E, control studies of unstable protein variants in transfected HEK293T cells suggest that cellular folding efficiency is uncorrelated with native-state thermodynamic stability. Folding and secretion of a molten two-disulfide analogue (containing paired substitutions CysA6 → Ser and CysA11→Ser; lanes 29 and 30) and partially folded analogue (IleA2 → Gly; lanes 31 and 32) are similar to wild type (lanes 27 and 28); an empty-vector control is provided in lanes 25 and 26. Cells were pulse-labeled with 35S-labeled amino acids for 1 h and chased 1 h. Chase media (M) and cell lysates (C) were immunoprecipitated with anti-insulin antiserum and analyzed by nonreducing Tris-Tricine/urea-SDS-PAGE. F, effect of proteosome inhibitor MG132 on intracellular proinsulin expression in HEK293T cells transfected with wild-type proinsulin (pro, lane 33) or ValA16 variant (lanes 34–36). Cells were pulse labeled for 1 h and lysed without chase, or chased 4 h in the presence (lanes 35) or absence (lane 36) of 20 mm MG132.

In the course of screening a variety of cell lines, we observed that HEK293T cells generally exhibit higher expression of human proinsulin (e.g. Fig. 3C, lanes 13 and 14) relative to rodent CLA14 cells (lanes 3 and 4). We further observed that HEK293T cells impose more stringent quality control as defined by the relative amounts of non-native isomers secreted into the medium. Subsequent experiments thus utilized this human cell line. In HEK293T cells, folding of [ValA16]proinsulin in the ER preferentially yields non-native isomers (Fig. 3C, lane 15) that are not secreted (lane 16). Pulse-chase experiments (4 h with or without proteosome inhibitors; lactacystin in Fig. 3D and MG132 in Fig. 3F) indicate that the misfolded variant retained in the ER undergoes proteolytic degradation (lanes 22 versus 24 and 35 versus 36). A clinical mutation (CysA7 → Tyr) provided positive control for misfolding, ER retention, and degradation (Fig. 3D, lanes 19, 21, and 23); this mutation causes DM in the Akita mouse (75) and humans (36).

A probe for UPR activation was provided by up-regulation of ER resident chaperone immunoglobulin-binding protein (76). An assay for induction of the UPR transcriptional program was provided by co-transfection of a proinsulin expression plasmid with a plasmid employing the BiP promoter to drive expression of luciferase (56). Transfection efficiency was normalized by co-transfection of a β-galactosidase construct driven by a viral promoter (cytomegalic virus; CMV). Each experiment was repeated three times with triplicate samples (nine in total), enabling statistical significance to be evaluated within and between data sets. Whereas co-transfection of wild-type insulin caused an ∼2-fold increase in luciferase expression relative to base line, co-transfection of [ValA16]proinsulin induced an ∼4-fold increase (p < 0.02); the extent of UPR activation by the proinsulin variant is similar to that induced by addition of tunicamycin (an inhibitor of protein glycosylation in the secretory pathway) to control cells co-transfected with the empty parent plasmid (see supplemental Fig. S1 and supplemental Table S1).

Partial Rescue of Folding by a Second-site Substitution

In the course of screening variant proinsulins, we observed that substitution ThrA8 → His enhanced expression and secretion in CLA14 cells (lanes 5 and 6 in Fig. 3A and counterparts in Fig. 3B). This surface substitution (found in avian insulins) in principle enhances the α-helical propensity of the A1–A8 segment (77, 78). We therefore tested whether HisA8 might rescue the folding defect caused by ValA16 (Fig. 3A and counterparts in Fig. 3B, lanes 9 and 10; lanes 9′ and 10′). Expression and secretion are partially restored relative to ValA16 alone but still markedly decreased relative to wild type. Refolding studies of [HisA8,ValA16]proinsulin, obtained by recombinant expression in E. coli, yielded a distribution of misfolded products similar to those observed in studies of [ValA16]proinsulin,6 likewise precluding isolation of the folded variant.

Despite the slight effects of HisA8 in partial rescue of the ValA16-associated folding defect, we undertook synthetic studies in an effort to obtain a sufficient quantity of a ValA16-containing insulin analogue for analysis of structure and function. The efficiency of wild-type chain combination was enhanced by ∼20% by the stabilizing HisA8 substitution. More striking effects were observed in chemical synthesis of [HisA8,ValA16]insulin; efficiency of chain combination rose from essentially unobservable (above) to “only” 8-fold impaired. Although this yield remained anomalously low, it represented an augmentation of >25-fold and, through brute force of mass action, enabled isolation of the analogue in milligram quantities.

Folding Efficiency and Stability Are Uncorrelated

Cellular folding may be impaired by one or more of several molecular mechanisms as follows: a kinetic block en route to an on-pathway intermediate, aberrant stabilization of an off-pathway intermediate, or instability and degradation of the folded state, once reached. The above PAGE assay, by distinguishing between native and non-native disulfide isomers, provided evidence for inefficient disulfide pairing but cannot distinguish between these possibilities. This issue was further pursued by correlating cellular and biophysical studies. Because proinsulin consists of a folded insulin moiety and disordered connecting domain, effects of amino acid substitutions on native-state stability were investigated in corresponding insulin analogues. CD provided a convenient probe for fractional unfolding as a function of chemical denaturation (Fig. 4). Fits to a two-state model (58) in each case were characterized by R-values greater than 0.99.

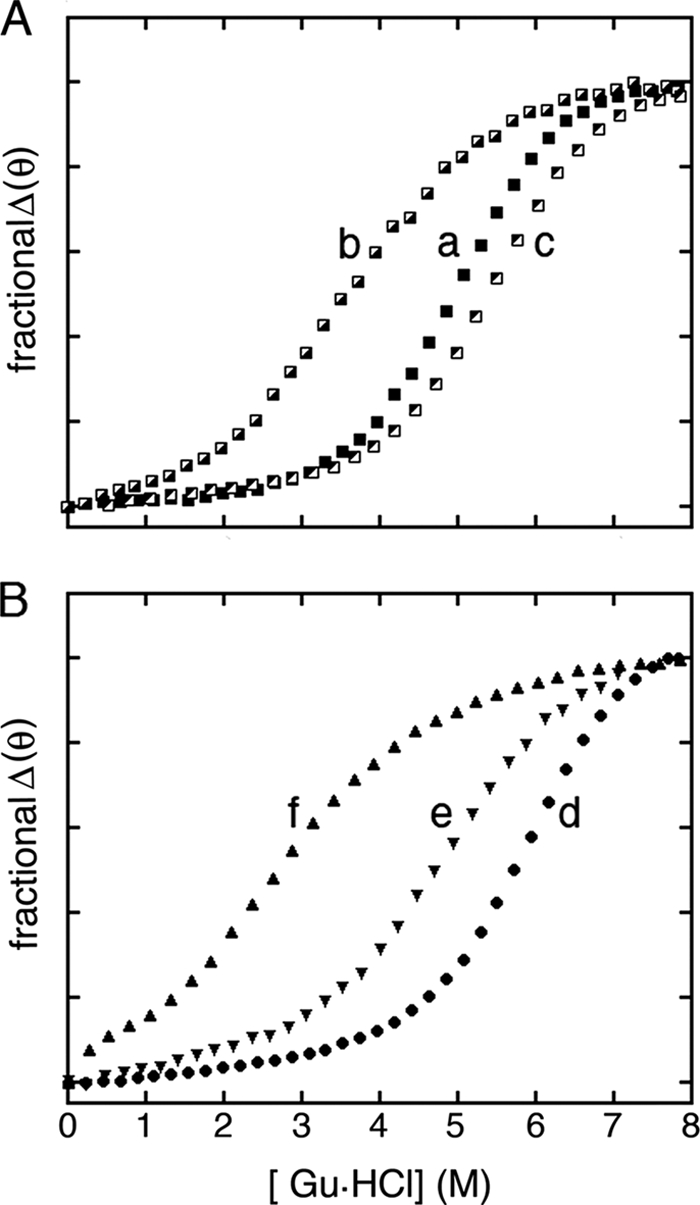

FIGURE 4.

CD studies of protein stability. A, guanidine-induced unfolding of insulin analogues as monitored by mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm: wild-type insulin (a, ■), [HisA8,ValA16]insulin (c, ◩), and control analogue [HisA8]insulin (b,  ). B, corresponding studies of DKP-insulin analogues: parent monomer (d, ●), GlyA2 analogue (e, ▾), and SerA6,SerA11 two-disulfide analogue (f, ▴). Fit to a two-state model by nonlinear least squares regression was in each case characterized by R-factors greater than 0.99, justifying extrapolation of free energies (ΔGu) to zero denaturant concentration (supplemental Table S2) (58). GuHCl, guanidine-HCl.

). B, corresponding studies of DKP-insulin analogues: parent monomer (d, ●), GlyA2 analogue (e, ▾), and SerA6,SerA11 two-disulfide analogue (f, ▴). Fit to a two-state model by nonlinear least squares regression was in each case characterized by R-factors greater than 0.99, justifying extrapolation of free energies (ΔGu) to zero denaturant concentration (supplemental Table S2) (58). GuHCl, guanidine-HCl.

The stability of [HisA8,ValA16]insulin was observed to be reduced relative to insulin and [HisA8]insulin (Fig. 4A). Its free energy of unfolding (ΔGu), as inferred from a two-state model (58), is 2.1 ± 0.1 kcal/mol (supplemental Table S2). This represents a perturbation (ΔΔGu) of 2.8 ± 0.2 kcal/mol relative to [HisA8] (ΔGu 4.9 kcal/mol), presumably due to the following: (i) substitution of a β-branched residue in an α-helix (79), and (ii) a packing defect in the hydrophobic core (80) with possible transmitted structural changes (81). Native disulfide pairing in the three analogues was verified in each case by x-ray crystallography (below).

To test whether decreased native-state stability might in itself be responsible for the impaired folding efficiency of [ValA16]insulin and [HisA8,ValA16]proinsulin, we investigated the cellular folding and secretion of two partially folded mutant proinsulins, a two-disulfide analogue containing pairwise substitution of CysA6 and CysA11 by Ser (and so lacking cystine A6–A11; Fig. 3, lanes 29 and 30), and an analogue containing core substitution IleA2 → Gly (lanes 31 and 32). Biophysical studies of these analogues have previously been described in the context of an engineered monomer (DKP-insulin) (82). Native disulfide pairing was verified by two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy (21, 83).

The two-disulfide analogue [SerA6,SerA11]DKP-insulin adopts a flexible conformation of marginal stability lacking the A1–A8 α-helix; [GlyA2]insulin also exhibits local unfolding of this α-helix (21, 24, 57, 83). Denaturation studies indicated that the stabilities of these analogues are reduced to an extent similar to or greater than that of [HisA8,ValA16]insulin (Fig. 3B and supplemental Table S2), and yet the corresponding mutant proinsulins were efficiently folded and secreted by HEK293T cells (Fig. 3E). Chain combination yields in their chemical synthesis were likewise robust. The contrast between the folding properties of ValA16-containing variants, on the one hand, and the unstable control analogues, on the other, suggests that LeuA16 contributes to efficiency of disulfide pairing in a way that is disproportionate to its role in the native state. Efficient folding, trafficking, and secretion of [SerA6,SerA11]proinsulin and [GlyA2]proinsulin further suggest that native structural organization (i.e. folding of the A1–A8 α-helix) is not required to pass quality control checkpoints in the ER and secretory pathway.

Structure-Function Relationships

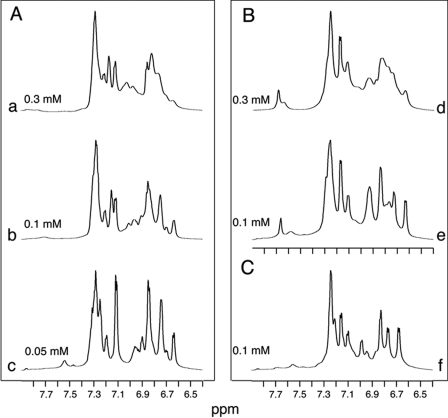

Despite its impaired folding efficiency, the affinity of [HisA8,ValA16]insulin for the insulin receptor (Kd 0.15 ± 0.03 nm) is almost 3-fold higher than that of wild-type insulin (Kd 0.41 ± 0.06 nm). Because [HisA8]insulin exhibits similarly enhanced activity (77, 78), these results indicate that, once folding is achieved, substitution of LeuA16 by Val does not perturb receptor binding. A probe for maintenance of the receptor-binding surface was also provided by dimerization. Comprising the central α-helix and C-terminal β-strand of the B-chain, the dimer interface of insulin contains multiple side chains also involved in receptor binding (48). This surface is buttressed by LeuA16 (45), and so its maintenance or perturbation in A16 analogues provides a read-out of possible transmitted conformational changes. Because the interface contains aromatic side chains (TyrB16, PheB24, PheB25, and TyrB26), dimerization may conveniently be monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy (82, 84). Our studies were simplified by incorporation of substitution HisB10 → Asp to block the independent trimerization surface (82, 85) (which would otherwise lead to further self-assembly) (48). Aromatic 1H NMR spectra of [AspB10]insulin and [AspB10,ValA16]insulin exhibit similar concentration-dependent resonance broadening between 50 and 300 μm (Fig. 5, A and B), indicating analogous dimerization properties. The spectrum of a related monomeric analogue retained a native-like pattern of chemical shifts ([ValA16]DKP-insulin; Fig. 5C). Although dispersion is partially attenuated, its two-dimensional NOESY spectrum contains long range inter-residue cross-peaks characteristic of native-like tertiary structure (supplemental Fig. S3).

FIGURE 5.

1H NMR studies of insulin analogues. Aromatic resonances provide probes of dimerization. A, spectra of [AspB10]insulin in the protein concentration range 0.05–0.30 mm at neutral pH and 25 °C (spectra a–c). B, corresponding dimerization of [ValA16,AspB10]insulin (spectra d and e). C, reference spectrum of ValA16 analogue of engineered monomer DKP-insulin (spectrum f).

To investigate the structure of [HisA8,ValA16]insulin in detail, single crystals were grown in the presence of zinc ions under conditions well characterized in wild-type insulin (48, 86). The crystals diffracted to a resolution of 1.8 Å with unit-cell dimensions consistent with hexamer form T3Rf3. The variant structure was determined by molecular replacement; statistical information is provided in the supplemental Table S3. Wild-type and variant hexamers are essentially identical (Fig. 6, A and B); root mean square deviations are provided in supplemental Tables S4–S7. The side chains of LeuA16 and ValA16 (Fig. 6, A and B, red) occupy similar core positions without perturbation of the A12–A18 α-helix. The ValA16 side chain is well defined in both T- and Rf-protomers without evidence of multiple conformations (Fig. 6, C and D). Surrounding density is likewise unambiguous without packing defects. (In the T-state density is weak for one branch of LeuB15 (Fig. 6C), but similar features have been observed in wild-type hexamers.) Inferred solvent accessibilities of the variant side chains are given in supplemental Table S8 relative to wild type. A comparison between respective inter-residue distances involving ValA16 (variant T- and R-protomers) or LeuA16 (in multiple wild-type structures) is provided in supplemental Table S9.

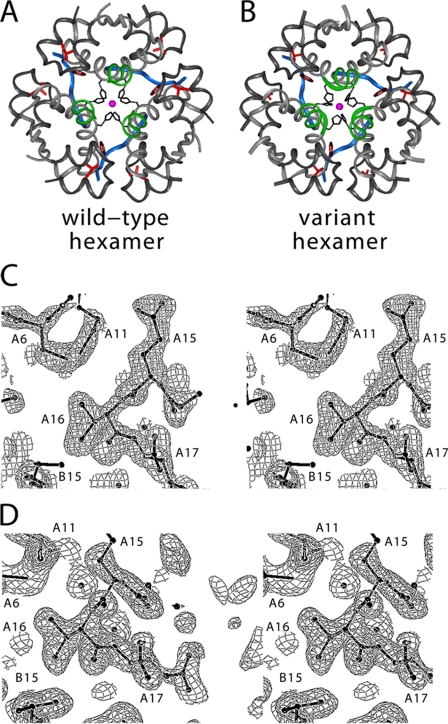

FIGURE 6.

Crystal structure of [HisA8,ValA16]insulin. A, overview of wild-type T3R3f zinc hexamer. The A-chain is shown in light gray with A16 side chain in red. The B1–B8 segments are shown in blue (T-state) or green (R-state); the remainder of the B-chain is dark gray. Also shown is the coordination of the central zinc ions (magenta) by HisB10 side chains (black). B, corresponding view of variant hexamer. C and D, regions of electron density maps (2Fo − Fc) showing A16 side chain and its environment in T-state protomer (C) and R-state protomer (D).

Global alignment of respective T- and R-protomers relative to a collection of wild-type protomers indicates overlapping B-chain conformations and similar but not identical A-chain positions (Fig. 7). B-chain-specific alignment reveals a small rigid-body displacement of each A-chain α-helix that is systematic relative to conformational variability among wild-type structures. The structure of the variant A-chain nonetheless closely adjoins wild-type structures. Comparison of the structures of [HisA8,ValA16]insulin and [HisA8]insulin (49) in the same crystal form indicates that the small adjustment of the A-chain is likely to be due to the A16 substitution, apparently in compensation for loss of side-chain volume (Fig. 8). These subtle changes seem unlikely to provide a structural basis for the marked effects of the A16 substitution on folding. The absence of significant perturbations in structure or function suggests that LeuA16 functions transiently in an unobserved folding intermediate and, despite its contribution to global stability, is otherwise dispensable once folding is achieved.

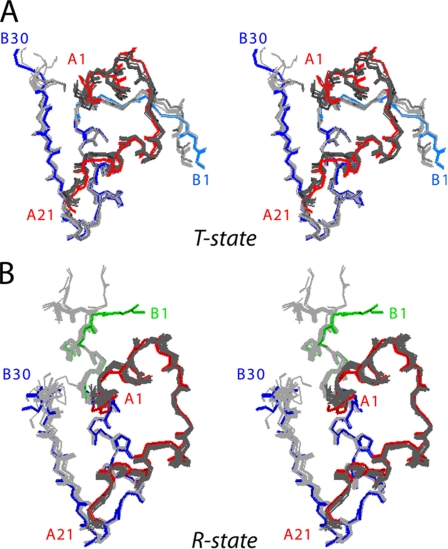

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of the crystal structure of [HisA8,ValA16]insulin with prior crystal structures. A, superposition of T-state protomer of variant with reference structures (PDB entries 1APH, 1DPH, 1BEN, 1MPJ, 1TRZ, 1TYL, 1TYM, 1RWE, 1G7A, 1ZNI, 2INS, and 4INS). The A- and B-chains of the A16 variant are red and blue (thick sticks), respectively, whereas the A- and B-chains of the reference structures are dark and light gray (thin lines). The B1–B8 segment of the variant is powder blue. B, corresponding alignment of R-state protomers. The A-chain of the variant is shown in red, and the B-chain in green (B1–B8) or blue (B9–B30). The A- and B-chains of the reference structures are shown in dark and light gray (PDB entries 1BEN, 1G7A, 1RWE, 1EV3, 1EV6, 1MPJ, 1TRZ, 1TYL, 1MPJ, 1ZEG, 1ZNJ, and 1ZNI). Structures were aligned with respect to the main-chain atoms of residues A1–A21 and B3–B28.

FIGURE 8.

Structural environment of ValA16 in relation to LeuA16 in control structure of [HisA8]insulin. A, stereo comparison of corresponding side chains in T-state protomers. Position of ValA16 (gray) in T-state protomer in relation to selected residues in A-chain (IleA2 and TyrA19 (red); CysA6 and CysA11 (gold)) and B-chain (PheB1, LeuB11, AlaB14, LeuB15, and ValB18 (green)). [HisA8]Insulin (black; PDB entry 1RWE, molecule 1). B, stereo comparison of corresponding side chains in R-state protomers of [ValA16,HisA8]insulin (color scheme as in A with addition of R-state-specific ligand (phenol; blue and asterisk) and [HisA8]insulin (black; PDB entry 1RWE, molecule 2).

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the folding of a globular domain. An invariant residue in proinsulin (LeuA16; position 81 in intact proinsulin) is required for its folding efficiency but is open to substitution in the mature hormone. Whereas expression of [ValA16]proinsulin in mammalian cells leads to disulfide mispairing and degradation in association with ER stress, comparison of related insulin analogues ([ValA16,HisA8]insulin and [HisA8]insulin) demonstrated retention of native-like structure and function. We discuss these results in relation to the structural origins of disulfide pairing. Our findings have implications for neonatal DM as a prototypical disease of misfolding.

Substitution of LeuA16 by Val reduces the stability of the native state, presumably due in part to decreased α-helical propensity (79, 87) and to loss of side-chain volume (80). Yet control studies of destabilizing substitutions elsewhere in the hydrophobic core (positions A2 and A6–A11) revealed unperturbed fold efficiencies, both in a transfected human cell line and as probed by insulin chain combination. These contrasting findings indicate that effects on folding can be distinguished from extent of native-state perturbation. Multiple molecular models may account for these findings. The conformational search leading to native disulfide pairing may be rendered inefficient due to destabilization of on-pathway intermediates or stabilization of off-pathway intermediates. Apparent bottlenecks may reflect thermodynamic or kinetic traps. A mutation may even create barriers not pertinent to the folding mechanism of the wild-type protein. The coarseness of our experimental probes thus prevents unambiguous interpretation of our results on the molecular level.

We suspect that more than one molecular mechanism may underlie the profound inefficiency of folding of [ValA16]proinsulin. A kinetic barrier to formation of an on-pathway intermediate, for example, may lead to increased occupancy of a non-native disulfide isomer as a thermodynamic trap susceptible to degradation. Which is cause and which is effect may in turn be difficult to distinguish. We nonetheless propose, as a general framework for discussion, that ValA16 disproportionately impairs the stability of a species containing the single cystine A20–B19. Prior studies have suggested that this species defines an obligatory on-pathway disulfide intermediate.7 Nascent native-like structure in such an intermediate could exert kinetic control of disulfide pairing, whereas folding efficiency would be unperturbed by substitutions extrinsic to this proto-core. Even as we recognize the limitations of the present data, it may illuminate future studies to consider how they relate to established biochemical features of proinsulin and the mechanism of insulin chain combination.

Disulfide Intermediates in Protein Folding

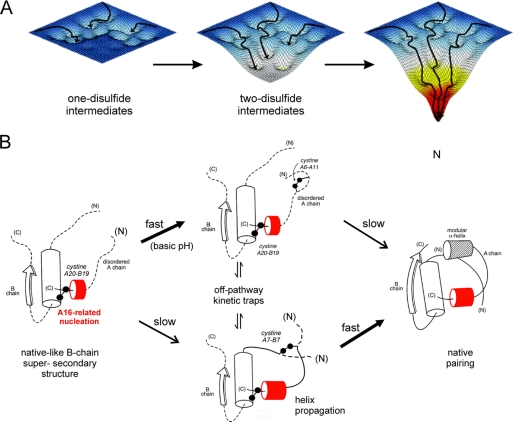

Oxidative folding may be probed by chemical trapping of populated disulfide intermediates (88). Application to proinsulin and related polypeptides is notable for the transient accumulation of one- and two-disulfide intermediates (67–69). Their partial folding may be represented by a series of trajectories on successive free-energy landscapes (Fig. 9A). We envisage that each landscape governs folding trajectories in the presence of a specific subset of disulfide bridges. Because the polypeptide acquires structure stepwise on successive pairing, the landscapes proceed from shallow to steep. A preferred sequence of disulfide intermediates, as defined by chemical trapping, hence provides a framework for visualizing a progression of multiple folding trajectories on funnel-shaped landscapes. This perspective integrates the classical disulfide-centered paradigm (89) with general physical models of folding (1, 5). Despite its elegance, the landscape perspective is difficult to establish experimentally and so in the present context should be regarded as an evocative metaphor. The utility of this metaphor lies in its potential for exploration by molecular dynamics simulations as a foundation for the design and interpretation of experiments (10).

FIGURE 9.

Energy landscape view of proinsulin folding and disulfide pairing. A, formation of successive disulfide bridges may be viewed as enabling a sequence of folding trajectories on a succession of steeper funnel-shaped free-energy landscapes. B, preferred pathway of disulfide pairing begins with cystine A20–B19 (left), whose pairing is directed by a nascent hydrophobic core formed by the central B-domain α-helix (residues B9–B19), part of the C-terminal B-chain β-strand (B24–B26), and part of the C-terminal A-domain α-helix (A16–A20). Alternative pathways mediate formation of successive disulfide bridges (middle panel) en route to the native state (right panel). The mechanism of disulfide pairing is perturbed by clinical mutations associated with misfolding of proinsulin.

The notion of successive landscapes is based on the observation of nonrandom disulfide intermediates. Although refolding studies of proinsulin are limited by aggregation (90), disulfide pathways of related polypeptides are well characterized (20, 23, 67–69, 91, 92). A structural pathway has been proposed based on equilibrium models (Fig. 9B) (20–22, 24–29, 93). A key role is played by initial formation of cystine A20–B19, which in the native state connects the C-terminal α-helix of the A-domain to the central α-helix of the B-domain. This bridge packs within a cluster of conserved side chains in the hydrophobic core, including LeuA16 (31, 32, 57). Neighboring side chains include LeuB11, LeuB15, LeuB18, PheB24, and TyrA19. In one- and two-disulfide models, LeuA16 plays a prominent structural role in maintenance of a specific partial fold, recapitulating salient features of the native state (29). We envisage that general hydrophobic clustering facilitates alignment of CysB19 and CysA20; once pairing has occurred, the bridge stabilizes a more specific organization of neighboring aliphatic and aromatic side chains.

This study has demonstrated that substitution of LeuA16 by Val, although compatible with native structure and function, imposes a block to the folding of proinsulin in mammalian cells. This block (recapitulated in chain combination) may arise from perturbations analogous to those that impair native-state stability but in the context of an ensemble of partial folds. Key perturbations might thus arise from the following: (a) a packing defect in the nascent core that misaligns CysA20 and CysB19, and (b) decreased α-helical propensity of the A-domain segment of the unfolded polypeptide due to a β-branched substituent. Because AlaA16 (a helicogenic substitution of reduced volume) likewise blocks folding and secretion of a mini-proinsulin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (94, 95), perturbed hydrophobic collapse is likely to be the predominant mechanism. Mutations elsewhere in the A20–B19-associated subdomain similarly impair chain combination and yeast biosynthesis (24, 94, 96–98). This perspective suggests that abortive cellular folding of [ValA16]proinsulin reflects a primary defect in on-pathway processes and, as a secondary consequence, can markedly augment formation of non-native disulfide isomers (Fig. 9B, central panel). A reverse chain of causality, primary ValA16-related stabilization of a non-native fold leading indirectly to inefficient native folding, is also possible.

Relationship to Insulin Chain Combination

Although chain combination is ordinarily robust to amino acid substitutions (57), position A16 represents an Achilles' heel (45). An analogous block to chain combination was observed on removal of AsnA21 (96, 99, 100). Remarkably, chain combination was largely rescued on amidation of CysA20. Because in wild-type crystal structures the main-chain amide of AsnA21 participates in a hydrogen bond to the carbonyl oxygen of GlyB23 (supplemental Fig. S10), Katsoyannis and co-workers (96, 99, 100) proposed that pairing of CysA20 and CysB19 was dependent on formation of this hydrogen bond. These pioneering observations demonstrated that the yield of chain combination could be enhanced by fluorous modification at the C terminus (ethylamide versus trifluoroethylamide; supplemental Fig. S11). The former electronegative modification would be expected to withdraw electrons from the amide donor and hence strengthen the A21–B23 hydrogen bond. This study did not distinguish between kinetic and thermodynamic effects of the modifications.

We envisage as a working hypothesis that the side chain of LeuA16 and the A21–B23 main-chain hydrogen each stabilize a native-like partial fold directing pairing of cystine A20–B19. Whereas LeuA16 presumably participates in nonpolar interactions between nascent α-helices in the A- and B-domains (Fig. 9B), formation of the A21–B23 hydrogen bond apparently requires a specific orientation of the carbonyl group of GlyB23. In the native state this conserved glycine exhibits a positive ϕ dihedral angle, ordinarily forbidden to l-amino acids (48). Whereas d-Ala is readily accommodated at B23, the efficiency of chain combination is markedly impaired by l-AlaB23 (98) and blocked by l-ValB23.8 Similar stereospecific effects of l- and d-substitutions at GlyB20 imply that the productive intermediate exhibits a native-like B20–B23 β-turn. Anchored at one end by the B9–B19 α-helix and at the other end by PheB24, this turn is retained in a peptide model of a one-disulfide intermediate (29).

Why do insulin-related polypeptides exhibit initial pairing of cystine A20–B19 when these residues are so distant in sequence? We propose that folding begins with nascent α-helix formation within segments B9–B19 and A16–A20; these segments then interact via nonpolar clustering of LeuB11, LeuB15, LeuB18, LeuA16, TyrA19, and the two cysteines. Diffusion-collision of α-helices aligns the thiol moieties of A20 and B19 for disulfide pairing. The stability (or meta-stability) of this intermediate would be augmented by the A21–B23 hydrogen bond and native-like packing of PheB24 against one edge of the disulfide bridge.

Implications for Human Genetics

Dominant mutations in the insulin gene have recently been identified as a cause of permanent neonatal-onset DM (36–39). Like ValA16, these mutations are predicted to block folding in the ER and so impair the function of pancreatic β-cells. Although expression of the wild-type insulin allele would in other circumstances be sufficient to maintain homeostasis, studies of a corresponding mouse model (75, 101, 102) have demonstrated that misfolding of the variant perturbs wild-type biosynthesis (34, 103). Impaired β-cell secretion of insulin is associated with ER stress, distorted organelle architecture, and eventual cell death (35, 104).

Clinical mutations fall in two classes as follows: (a) substitutions that introduce or remove a Cys and so unbalance disulfide pairing, and (b) substitutions at other sites apparently critical to the structural mechanism of disulfide pairing. The latter class includes GlyB23 → Val at the site of the key B23–A21 hydrogen bond (above). Additional mutational hot spots have been observed at B5, B6, and B8, conserved sites proposed to direct pairing of CysA7 and CysB7 (50, 55, 105, 106). To date non-cysteine-related mutations have been observed only in the B-domain. The present results demonstrate that conserved sites in the A-domain may likewise contribute to folding efficiency and so are likely to be observed in neonatal DM. The growing catalogue of clinical mutations in the insulin gene promises to provide important insight into sequence determinants of folding in vivo. It is important to note that the distribution and frequency of clinical mutations may reflect the relative susceptibility of DNA codons to mutagenesis (due to genomic sequence and structure) as well as the consequences of the predicted amino acid substitutions in the variant polypeptides.

The genetics of neonatal DM and other diseases of misfolding suggest that the evolution of proteins has been constrained not only by its structure and function, but also by an underlying risk of toxic misfolding. The native-like crystal structure of a “nonfoldable” insulin analogue demonstrates that the transient function of a conserved side chain in the mechanism of folding may be structurally inapparent once the ground state is reached. Although neonatal DM is uncommon, the diversity of associated mutations in the insulin gene highlights the possible role of wild-type bottlenecks and resultant chronic ER stress in type 2 DM (34). The pathogenesis of progressive β-cell dysfunction in type 2 DM and the metabolic syndrome poses a medical problem of overarching societal importance.

Concluding Remarks

The evolution of proteins faces independent structural constraints at multiple levels of biosynthesis and function. A classical model is provided by insulin; its conserved residues may contribute to one or more essential processes, including folding efficiency in the β-cell, prevention of toxic misfolding, self-assembly within secretory granules, disulfide stability in the bloodstream, and receptor binding. Interlocking sets of constraints may account for the limited sequence diversity among vertebrate insulins (48).

LeuA16 provides an example of an invariant residue that enables effective folding, but once the native state has been reached, ValA16 is equally compatible with canonical structure, assembly, and receptor binding. This subtle substitution impairs ground-state stability and may disproportionately perturb the relative stabilities and kinetic accessibilities of obligatory on- or off-pathway intermediates. The marked compression of structural information within the sequence of insulin suggests that other conserved sites may facilitate folding but weaken receptor binding (105); alternatively, structural features favoring receptor binding may impede disulfide pairing (107, 108). We thus envisage that specific residues in insulin play distinct roles at each stage of its conformational “life cycle.” The growing clinical data base of DM-associated mutations suggests that the sequence of insulin lies at the edge of nonfoldability.

Supplemental Material

Eleven figures provide a histogram of ER stress assay, NMR spectra, additional depictions of the crystal structure, and summary of prior chemical studies of insulin chain combination; and nine tables give the original ER stress data, thermodynamic modeling of protein denaturation studies, and structural comparisons. Coordinates have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession number 3GKY).

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Nakagawa for receptor binding assays; W. Jia for assistance with spectroscopy; and G. G. Dodson, D. F. Steiner, J. Whittaker, and J. Whittingham for discussions. We are grateful to a member of the Editorial Board for insights into folding mechanisms.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK052085 (to R. B. M.), DK48280 (to P. A.), DK56673 (to P. G. K.), and DK0697674 (to M. A. W.). This work was also supported by the American Diabetes Association (to M. A. W.). This article is a contribution from the Cleveland Center for Membrane and Structural Biology.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S11, Tables S1–S9, and additional references.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3GKY) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

Secretion of a corresponding variant single-chain insulin analogue in yeast P. pastoris, ordinarily robust to diverse mutations, was impaired by 40-fold by the paired substitutions HisA8,ValA16 (from 40 to 1 mg/liter).

The fractional contribution of a given interaction to the stability of a native-like partial fold can be larger or smaller than its fractional contribution to the native state. Whereas both IleA2 and LeuA16 each contribute to native-state stability through core packing, for example, folding and chain combination are robust to A2 substitutions (45). Kinetic control via a subset of native-like contacts in a transition state differs from the concept of “pathway mutations” as originally envisioned in studies of a β-helical phage tail spike (46).

S.-Q. Hu and M. A. W., unpublished results.

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- DKP-insulin

- insulin analogue containing three substitutions in B-chain (AspB10, LysB28 and ProB29)

- DM

- diabetes mellitus

- HPLC

- high performance liquid chromatography

- UPR

- unfolded protein response

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank. Amino acids are designated by three-letter code.

REFERENCES

- 1.Onuchic J. N., Luthey-Schulten Z., Wolynes P. G. (1997) Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 48, 545–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobson C. M., Karplus M. (1999) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 9, 92–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shakhnovich E., Farztdinov G., Gutin A. M., Karplus M. (1991) Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 1665–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onuchic J. N., Socci N. D., Luthey-Schulten Z., Wolynes P. G. (1996) Fold. Des. 1, 441–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dill K. A., Chan H. S. (1997) Nat. Struct. Biol. 4, 10–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazaridis T., Karplus M. (1997) Science 278, 1928–1931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirny L. A., Abkevich V. I., Shakhnovich E. I. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 4976–4981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinner A. R., Abkevich V., Shakhnovich E., Karplus M. (1999) Proteins 35, 34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiana G., Broglia R. A., Shakhnovich E. I. (2000) Proteins 39, 244–251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveberg M., Wolynes P. G. (2005) Q. Rev. Biophys. 38, 245–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dodson G., Steiner D. (1998) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8, 189–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steiner D. F., Chan S. J. (1988) Horm. Metab. Res. 20, 443–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner D. F. (1967) Trans. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 30, 60–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank B. H., Veros A. J. (1968) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 32, 155–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pekar A. H., Frank B. H. (1972) Biochemistry 11, 4013–4016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank B. H., Pekar A. H., Veros A. J. (1972) Diabetes 21, 486–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snell C. R., Smyth D. G. (1975) J. Biol. Chem. 250, 6291–6295 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brems D. N., Brown P. L., Heckenlaible L. A., Frank B. H. (1990) Biochemistry 29, 9289–9293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss M. A., Frank B. H., Khait I., Pekar A., Heiney R., Shoelson S. E., Neuringer L. J. (1990) Biochemistry 29, 8389–8401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narhi L. O., Hua Q. X., Arakawa T., Fox G. M., Tsai L., Rosenfeld R., Holst P., Miller J. A., Weiss M. A. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 5214–5221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hua Q. X., Hu S. Q., Frank B. H., Jia W., Chu Y. C., Wang S. H., Burke G. T., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 264, 390–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai Y., Tang J. G. (1996) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1296, 63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hober S., Uhlén M., Nilsson B. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 4616–4622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss M. A., Hua Q. X., Jia W., Chu Y. C., Wang R. Y., Katsoyannis P. G. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 15429–15440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo Z. Y., Feng Y. M. (2001) Biol. Chem. 382, 443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng Y., Liu D., Wang J. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 330, 821–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jia X. Y., Guo Z. Y., Wang Y., Xu Y., Duan S. S., Feng Y. M. (2003) Protein Sci. 12, 2412–2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan H., Guo Z. Y., Gong X. W., Xi D., Feng Y. M. (2003) Protein Sci. 12, 768–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hua Q. X., Mayer J. P., Jia W., Zhang J., Weiss M. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 28131–28142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sieber P., Eisler K., Kamber B., Riniker B., Rittel W., Märki F., de Gasparo M. (1978) Hoppe-Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 359, 113–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hua Q. X., Gozani S. N., Chance R. E., Hoffmann J. A., Frank B. H., Weiss M. A. (1995) Nat. Struct. Biol. 2, 129–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hua Q. X., Jia W., Frank B. H., Phillips N. F., Weiss M. A. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 14700–14715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu M., Li Y., Cavener D., Arvan P. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 13209–13212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ron D. (2002) J. Clin. Invest. 109, 443–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu M., Hodish I., Rhodes C. J., Arvan P. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15841–15846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Støy J., Edghill E. L., Flanagan S. E., Ye H., Paz V. P., Pluzhnikov A., Below J. E., Hayes M. G., Cox N. J., Lipkind G. M., Lipton R. B., Greeley S. A., Patch A. M., Ellard S., Steiner D. F., Hattersley A. T., Philipson L. H., Bell G. I. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15040–15044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colombo C., Porzio O., Liu M., Massa O., Vasta M., Salardi S., Beccaria L., Monciotti C., Toni S., Pedersen O., Hansen T., Federici L., Pesavento R., Cadario F., Federici G., Ghirri P., Arvan P., Iafusco D., Barbetti F.Early Onset Diabetes Study Group of the Italian Society of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes (2008) J. Clin. Invest. 118, 2148–2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edghill E. L., Flanagan S. E., Patch A. M., Boustred C., Parrish A., Shields B., Shepherd M. H., Hussain K., Kapoor R. R., Malecki M., MacDonald M. J., Støy J., Steiner D. F., Philipson L. H., Bell G. I., Hattersley A. T., Ellard S. (2008) Diabetes 57, 1034–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molven A., Ringdal M., Nordbø A. M., Raeder H., Støy J., Lipkind G. M., Steiner D. F., Philipson L. H., Bergmann I., Aarskog D., Undlien D. E., Joner G., Søvik O., Bell G. I., Njølstad P. R. (2008) Diabetes 57, 1131–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang X. F., Arvan P. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 20838–20844 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steiner D. F., Clark J. L., Nolan C., Rubenstein A. H., Margoliash E., Aten B., Oyer P. E. (1969) Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 25, 207–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galloway J. A., Hooper S. A., Spradlin C. T., Howey D. C., Frank B. H., Bowsher R. R., Anderson J. H. (1992) Diabetes Care 15, 666–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steiner D. F. (1998) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2, 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang X. F., Arvan P. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 20417–20423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiss M. A., Nakagawa S. H., Jia W., Xu B., Hua Q. X., Chu Y. C., Wang R. Y., Katsoyannis P. G. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 809–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaufman R. J. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1211–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshida H. (2007) FEBS J. 274, 630–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baker E. N., Blundell T. L., Cutfield J. F., Cutfield S. M., Dodson E. J., Dodson G. G., Hodgkin D. M., Hubbard R. E., Isaacs N. W., Reynolds C. D. (1988) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 319, 369–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wan Z., Xu B., Huang K., Chu Y. C., Li B., Nakagawa S. H., Qu Y., Hu S. Q., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 16119–16133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiss M. A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19159–19163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu S. Q., Burke G. T., Schwartz G. P., Ferderigos N., Ross J. B., Katsoyannis P. G. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 2631–2635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mackin R. B., Choquette M. H. (2003) Protein Expr. Purif. 27, 210–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y., Liang Z. H., Zhang Y. S., Yao S. Y., Xu Y. G., Tang Y. H., Zhu S. Q., Cui D. F., Feng Y. M. (2001) Biotechnol. Bioeng. 73, 74–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu M., Ramos-Castañeda J., Arvan P. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14798–14805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hua Q. X., Liu M., Hu S. Q., Jia W., Arvan P., Weiss M. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24889–24899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tirasophon W., Welihinda A. A., Kaufman R. J. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 1812–1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hua Q. X., Chu Y. C., Jia W., Phillips N. F., Wang R. Y., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43443–43453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sosnick T. R., Fang X., Shelton V. M. (2000) Methods Enzymol. 317, 393–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pace C. N., Shaw K. L. (2000) Proteins 4, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones T. A., Zou J. Y., Cowan S. W., Kjeldgaard M. (1991) Acta Crystallogr. A 47, 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van den Akker F., Hol W. G. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55, 206–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laskowski R. A., Macarthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laskowski R. A. (1995) J. Mol. Graph. 13, 323–330, 307–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vajdos F. F., Ultsch M., Schaffer M. L., Deshayes K. D., Liu J., Skelton N. J., de Vos A. M. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 11022–11029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brzozowski A. M., Dodson E. J., Dodson G. G., Murshudov G. N., Verma C., Turkenburg J. P., de Bree F. M., Dauter Z. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 9389–9397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hober S., Forsberg G., Palm G., Hartmanis M., Nilsson B. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 1749–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miller J. A., Narhi L. O., Hua Q. X., Rosenfeld R., Arakawa T., Rohde M., Prestrelski S., Lauren S., Stoney K. S., Tsai L., Weiss M. A. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 5203–5213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qiao Z. S., Guo Z. Y., Feng Y. M. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 2662–2668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Katsoyannis P. G. (1966) Science 154, 1509–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tang J. G., Tsou C. L. (1990) Biochem. J. 268, 429–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chance R. E., Hoffman J. A., Kroeff E. P., Johnson M. G., Schirmer W. E., Bormer W. W. (1981) in Peptides: Synthesis, Structure and Function; Proceedings of the Seventh American Peptide Symposium (Rich D. H., Gross E. eds) pp. 721–728, Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steiner D. F. (1978) Diabetes 27, Suppl. 1, 145–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Frank B. H., Chance R. E. (1983) MMW Munch. Med. Wochenschr. 125, S14–S20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang J., Takeuchi T., Tanaka S., Kubo S. K., Kayo T., Lu D., Takata K., Koizumi A., Izumi T. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 103, 27–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bertolotti A., Zhang Y., Hendershot L. M., Harding H. P., Ron D. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 326–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaarsholm N. C., Norris K., Jørgensen R. J., Mikkelsen J., Ludvigsen S., Olsen O. H., Sørensen A. R., Havelund S. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 10773–10778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weiss M. A., Hua Q. X., Jia W., Nakagawa S. H., Chu Y. C., Hu S. Q., Katsoyannis P. G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40018–40024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.O'Neil K. T., DeGrado W. F. (1990) Science 250, 646–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eriksson A. E., Baase W. A., Zhang X. J., Heinz D. W., Blaber M., Baldwin E. P., Matthews B. W. (1992) Science 255, 178–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu J., Baase W. A., Baldwin E., Matthews B. W. (1998) Protein Sci. 7, 158–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weiss M. A., Hua Q. X., Lynch C. S., Frank B. H., Shoelson S. E. (1991) Biochemistry 30, 7373–7389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xu B., Hua Q. X., Nakagawa S. H., Jia W., Chu Y. C., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2002) Protein Sci. 11, 104–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Roy M., Lee R. W., Brange J., Dunn M. F. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 5448–5452 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brange J., Ribel U., Hansen J. F., Dodson G., Hansen M. T., Havelund S., Melberg S. G., Norris F., Norris K., Snel L. (1988) Nature 333, 679–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bentley G., Dodson E., Dodson G., Hodgkin D., Mercola D. (1976) Nature 261, 166–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Padmanabhan S., Marqusee S., Ridgeway T., Laue T. M., Baldwin R. L. (1990) Nature 344, 268–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Baldwin T. O., Ziegler M. M., Chaffotte A. F., Goldberg M. E. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 10766–10772 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Creighton T. E. (1997) Biol. Chem. 378, 731–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Qiao Z. S., Min C. Y., Hua Q. X., Weiss M. A., Feng Y. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 17800–17809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hober S., Hansson A., Uhlén M., Nilsson B. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 6758–6761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Milner S. J., Carver J. A., Ballard F. J., Francis G. L. (1999) Biotechnol. Bioeng. 62, 693–703 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hua Q. X., Narhi L., Jia W., Arakawa T., Rosenfeld R., Hawkins N., Miller J. A., Weiss M. A. (1996) J. Mol. Biol. 259, 297–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kristensen C., Kjeldsen T., Wiberg F. C., Schäffer L., Hach M., Havelund S., Bass J., Steiner D. F., Andersen A. S. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 12978–12983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang Z. J., Wu L., Qiao Z. S., Qiao M. Q., Feng Y. M., Guo Z. Y. (2008) Protein J. 27, 192–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chu Y. C., Burke G. T., Chanley J. D., Katsoyannis P. G. (1987) Biochemistry 26, 6972–6975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hua Q. X., Nakagawa S. H., Jia W., Hu S. Q., Chu Y. C., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 12299–12311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nakagawa S. H., Hua Q. X., Hu S. Q., Jia W., Wang S., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22386–22396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chu Y. C., Wang R. Y., Burke G. T., Chanley J. D., Katsoyannis P. G. (1987) Biochemistry 26, 6966–6971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chu Y. C., Wang R. Y., Burke G. T., Chanley J. D., Katsoyannis P. G. (1987) Biochemistry 26, 6975–6979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yoshioka M., Kayo T., Ikeda T., Koizumi A. (1997) Diabetes 46, 887–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Oyadomari S., Koizumi A., Takeda K., Gotoh T., Akira S., Araki E., Mori M. (2002) J. Clin. Invest. 109, 525–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Izumi T., Yokota-Hashimoto H., Zhao S., Wang J., Halban P. A., Takeuchi T. (2003) Diabetes 52, 409–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zuber C., Fan J. Y., Guhl B., Roth J. (2004) FASEB J. 18, 917–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nakagawa S. H., Zhao M., Hua Q. X., Hu S. Q., Wan Z. L., Jia W., Weiss M. A. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 4984–4999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hua Q. X., Nakagawa S., Hu S. Q., Jia W., Wang S., Weiss M. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24900–24909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hua Q. X., Xu B., Huang K., Hu S. Q., Nakagawa S., Jia W., Wang S., Whittaker J., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14586–14596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Xu B., Huang K., Chu Y. C., Hu S. Q., Nakagawa S., Wang S., Wang R. Y., Whittaker J., Katsoyannis P. G., Weiss M. A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14597–14608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]