The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 appropriated $1.1 billion for comparative effectiveness research (CER) and delineated CER as a key component of the national health care agenda. Most discussions of CER have focused on definitions, topic prioritization, and the potential impact of this discipline on individual patient care decisions. Less has been said about the role of health care delivery organizations (herein considered to be establishments with centralized, multidisciplinary resources to provide direct patient care, such as an integrated health system or a practice network) in contributing to the CER knowledge base and applying CER findings.

A recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report describes CER as “the generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care.”1 Comparative effectiveness research aims to discern which interventions work best for particular types of patients in real-world environments, information that is often unavailable from randomized trials. Comparative effectiveness research can be conducted on a wide range of substrates, including databases, systematic literature reviews, or clinical studies. The essential purpose of CER is to improve health outcomes at both the individual and the population levels by empowering consumers, clinicians, and policymakers to arrive at informed decisions.

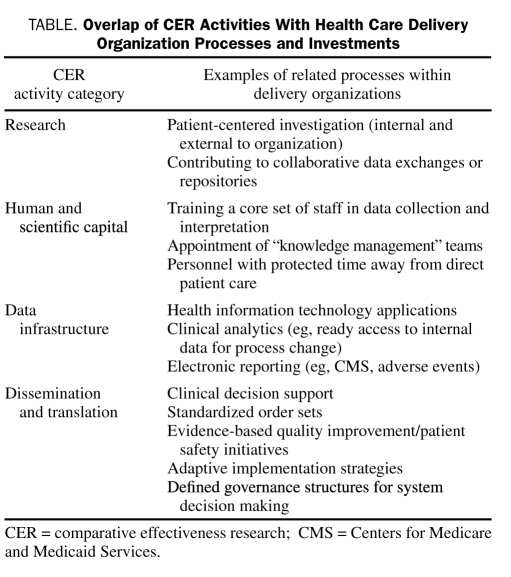

The Federal Coordinating Council for Comparative Effectiveness Research (established by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act) has identified 4 areas of CER activity and investment: research, human and scientific capital, data infrastructure, and dissemination and translation into practice.2 Importantly, the intent of the initial reports produced by the Federal Council and by the IOM and similar efforts by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (another central player in CER) was to set a broad, transparent, and sustainable CER strategy. As such, the categories of CER activity have not been earmarked for specific health care entities. In contrast to basic science research, in which academic centers or industry often have advantages because of enhanced resources or experience, due to its nascence, these associations have a limited role in CER.

Within this evolving CER framework, health care delivery organizations will emerge with overlapping roles both as developers and as end-users of CER content. Delivery organizations integrate the 2 main stakeholders in CER: clinicians and patients. Clinical staff can generate CER either indirectly (eg, partnerships in data sharing networks) or directly through active research pursuits (this is less common). Interactions among clinical staff, processes of care, and patients represent opportunities for application of CER. In a fundamental shift from judgment based primarily on service performance alone, health care delivery organizations are increasingly being measured according to outcomes.3 Operationalization of CER at an institutional level supports this transition.

See also page 1065

In the current issue of Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Simpson et al4 illustrate the complexities of the relationship between CER and health care delivery organizations. Their observational study showed a benefit between cardiovascular outcomes and total cost equivalency with atorvastatin use compared with simvastatin in a large population of patients with employer-based health insurance. The work fulfills the criteria of CER, but from the standpoint of a delivery organization, it triggers an additional series of questions beyond the clinical findings. For example, how do patients within the health care delivery organization compare to the study population? Does responsibility for accessing the study and applying its results fall to individual physicians, or should deployment of CER results be coordinated by designated personnel within the organization? What level of evidence is required to add a new drug to the formulary if an alternative is already in place?

To address these sorts of questions and realize the improved outcomes targeted by CER, health care delivery organizations need to engage the topic on multiple fronts. Mapping the 4 categories of CER activity to delivery organizations' operational and care processes offers mechanisms whereby this engagement can be achieved (Table). Often, the foundation for participation in CER can be accomplished by building on or adjusting existing workflows.

TABLE.

Overlap of CER Activities With Health Care Delivery Organization Processes and Investments

An expanded view of what constitutes CER provides opportunities for delivery organizations that previously have had minimal involvement in the research enterprise. The scope of CER entails more than comparisons of one treatment vs another. As Volpp and Das5 discuss, the study of how the behavior of the health care delivery system itself affects outcomes (eg, work intensity, staffing patterns, use of electronic health records [EHRs]) has generally not been subjected to the investigative rigor that many medical treatments have received. The importance of these aspects of care is reflected in the IOM's report in which one-half of the top 100 CER priorities were in the health services research domain.1 Delivery organizations without the bandwidth to undertake traditional clinical research (eg, coordinating a large National Institutes of Health—sponsored trial) in the past could more readily participate in studies exploring the effects of modifications in their care process on patient outcomes, either internally or as part of a collaboration. Indeed, as CER seeks to produce pragmatic information that can improve health care for all Americans, activation of “real-world” systems in the research endeavor is fundamental to success of that mission.6

In many health care delivery organizations, human and scientific capital for CER will probably need to take the form of designated groups specializing in its identification, distribution, and adoption. A relatively small number of sites will have capabilities to conduct original research or develop internal CER training programs, so organizational acumen in obtaining and interpreting the communal CER output is of heightened importance. Oversight of this CER knowledge management would potentially fit well in an organization's quality or evidence-based care departments.

Health information technology (HIT) underpins the data infrastructure development activity for CER. Most health care delivery organizations are currently in some stage of HIT implementation. HIT facilitates involvement in CER because the data used in daily operations can be modified for research data exchanges or applied locally to guide process improvement. Beyond the data, especially in view of the impetus toward EHRs, HIT will increasingly be used during transactions between patients and clinicians.

Dissemination and translation activity are the critical leverage points for health care delivery organizations to bring CER to their patients. The extended delays between evidence of an intervention's efficacy and its consistent delivery in practice (eg, β-blockers after acute myocardial infarction) have been well documented.7 Clearly, in this era of a rapidly growing scientific knowledge base, expecting individual practitioners to keep up with a new wave of CER publications as a singular mechanism of information knowledge and use is unlikely to yield meaningful gains. Furthermore, because the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Federal Council, and IOM have no authority or plans to adjudicate on specific treatment decisions, this responsibility lies within delivery organizations on a macro (Will a particular statin drug be offered on the system formulary?) and micro (Which statin drug on the formulary will this particular patient be offered on the basis of his or her risk profile?) level.

Accelerated application of CER in health care delivery organizations can manifest in several forms. Use of standardized order sets is one readily visible example. Growing evidence indicates a favorable impact of order sets and guideline-driven care on metrics such as mortality and length of hospital stay, most recently with pneumonia.8,9 Construction of these order sets allows embedding of CER content into care processes. For order sets to function efficiently as a CER implementation tool, delivery organizations need to articulate parameters of ownership and approval, explicit standards for content, and education and rollout. This active diffusion of CER represents a practical way to move to the final stage (from effectiveness knowledge to improved health care quality and value) on the translational road map.10,11

Clinical decision support for individual order items provides another scenario for implementing CER. This might play out when a health care professional who is using an EHR orders drug A, but, on the basis of specific characteristics of that patient, an alert suggests changing the prescription to drug B. The decision on whether to include both drugs as safe and therapeutically equivalent ordering options would be made at the organizational level; the decision for what to eventually prescribe at the point of care remains in the hands of the health care professional. The optimal workflow for delivering this type of evidence while being sensitive to alert fatigue is an area for future investigation.

Finally, because many health care delivery organizations have embraced quality improvement methodology as a mechanism to effect rapid process change, this approach represents an alternative avenue for translation of CER content. An appealing feature of quality improvement is that it would allow organizations to incorporate CER in selected priority areas quickly, independent of HIT or the more comprehensive systematic cultural and governance changes necessary for order set deployment.

As producers of generalizable knowledge and as stakeholders in CER content and application, health care delivery organizations will need to display adaptability to fully engage CER. Linking current organizational operations to the areas of CER activity is a first step in achieving that protean role. Ultimately, success with CER will be gauged by a health care delivery organization's ability to integrate this information into care processes that improve patient outcomes.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2009. http://www.iom.edu/en/Reports/2009/ComparativeEffectivenessResearchPriorities.aspx Accessed November 3, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services Federal Coordinating Council for Comparative Effectiveness Research: Report to the President and Congress Washington, DC: Dept of Health and Human Services; June2009. http://www.hhs.gov/recovery/programs/cer/cerannualrpt.pdf Accessed November 3, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohmer RM, Lee TH. The shifting mission of health care delivery organizations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):551-553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpson RJ, Jr, Signorovitch J, Birnbaum H, et al. Cardiovascular and economic outcomes after initiation of lipid-lowering therapy with atorvastatin vs simvastatin in an employed population. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2009;84(12):1065-1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volpp KG, Das A. Comparative effectiveness—thinking beyond medication A versus medication B. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(4):331-333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conway PH, Clancy C. Comparative-effectiveness research—implications of the Federal Coordinating Council's report. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(4):328-330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee TH. Eulogy for a quality measure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(12):1175-1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming NS, Ogola G, Ballard DJ. Implementing a standardized order set for community-acquired pneumonia: impact on mortality and cost. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(8):414-421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCabe C, Kirchner C, Zhang H, Daley J, Fisman DN. Guideline-concordant therapy and reduced mortality and length of stay in adults with community-acquired pneumonia: playing by the rules. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(16):1525-1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dougherty D, Conway PH. The “3T's” road map to transform US health care: the “how” of high-quality care. JAMA 2008;299(19):2319-2321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naik AD, Petersen LA. The neglected purpose of comparative-effectiveness research. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(19):1929-1931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]