Summary

Wolbachia are maternally inherited bacterial endosymbionts that occupy many but not all tissues of adult insects. During the initial mitotic divisions in Drosophila embryogenesis, Wolbachia exhibit a symmetric pattern of segregation. Wolbachia undergo microtubule-dependent and cell-cycle-regulated movement between centrosomes. Symmetric segregation occurs during late anaphase when Wolbachia cluster around duplicated and separating centrosomes. This centrosome association is microtubule-dependent and promotes an even Wolbachia distribution throughout the host embryo. By contrast, during the later embryonic and larval neuroblast divisions, Wolbachia segregate asymmetrically with the apical self-renewing neuroblast. During these polarized asymmetric neuroblast divisions, Wolbachia colocalize with the apical centrosome and apically localized Par complex. This localization depends on microtubules, but not the cortical actin-based cytoskeleton. We also found that Wolbachia concentrate in specific regions of the adult brain, which might be a direct consequence of the asymmetric Wolbachia segregation in the earlier neuroblast divisions. Finally, we demonstrate that the fidelity of asymmetric segregation to the self-renewing neuroblast is lower in the virulent Popcorn strain of Wolbachia.

Keywords: Mitosis, Wolbachia, Drosophila, Neuroblasts

Introduction

Bacteria and viral host pathogens exhibit tissue-specific host tropisms. Much of this tropism is explained by routes of entry during infection and subsequent cell-to-cell migration (Ireton, 2007; Sieczkarski and Whittaker, 2005). Less well explored are mechanisms that regulate the tissue distribution of obligate intracellular bacteria that are inherited through the germline. Of particular interest is the segregation of intracellular pathogens in mitotically active host cells, as this might be an important mechanism to spread infection to specific tissue types during host development. Wolbachia is a bacterial endosymbiont that infects numerous insect species and is an effective system in which to identify the factors that control pathogen distribution in host tissue (Serbus et al., 2008; Werren et al., 2008). Although much research has focused on Wolbachia germline concentration and transmission, a number of studies have convincingly demonstrated that Wolbachia are present in a broad array of larval and adult somatic tissues. These include the head, thoracic muscles, midgut, Malpighian tubules (Dobson et al., 1999; McGraw et al., 2002), somatic cells associated with the testis, and ovaries (Clark et al., 2005; Clark et al., 2008; Frydman et al., 2006; McGraw et al., 2002; Riparbelli et al., 2007). Comparisons among several host species and Wolbachia strains demonstrate that factors intrinsic to both the host and Wolbachia control its tissue distribution and density (Dobson et al., 1999; Ijichi et al., 2002; Veneti et al., 2004). Popcorn (WPop), a virulent strain of Wolbachia, provides a particularly striking demonstration of the role of Wolbachia-specific factors as it over-replicates in adult neurons and muscle cells ultimately causing tissue degeneration and premature death (Min and Benzer, 1997). Recent studies demonstrate that when WPop is transferred from Drosophila melanogaster to Aedes aegypti (mosquito), overproliferation and early lethality are still observed (McMeniman et al., 2009). Conversely, experiments in which the WMel strain of Wolbachia overreplicates when transferred from D. melanogaster to Drosophila simulans, demonstrate that host factors also have an important role in Wolbachia density (Serbus and Sullivan, 2007; Veneti et al., 2004; Zabalou et al., 2008).

Insights into mechanisms of Wolbachia segregation during host mitosis have come from studying initial mitotic divisions in early Drosophila embryogenesis. After fertilization, the embryos undergo a series of rapid synchronous nuclear divisions before cellularizing during nuclear cycle 14. During nuclear cycles 10 to 13, the divisions occur on a plane just beneath the plasma membrane and thus are easily imaged. Cytological analysis of Wolbachia-infected embryos revealed that Wolbachia localize near the centrosomes throughout the cell cycle (Callaini et al., 1994; Kose and Karr, 1995; O'Neill and Karr, 1990), which was found to depend on microtubule asters but not actin (Callaini et al., 1994). During the syncytial mitotic divisions, the bacteria reside in equal numbers at each daughter centrosome, ensuring transmission to both daughter nuclei (Kose and Karr, 1995). This segregation pattern results in a broad Wolbachia distribution throughout the embryo by cellularization. If this pattern of segregation were to continue throughout host development, one would expect Wolbachia to be equally distributed throughout all larval and adult tissues. However, Wolbachia are unevenly distributed in adult tissues (Dobson, 2003; Ijdo et al., 2007; McGraw et al., 2002).

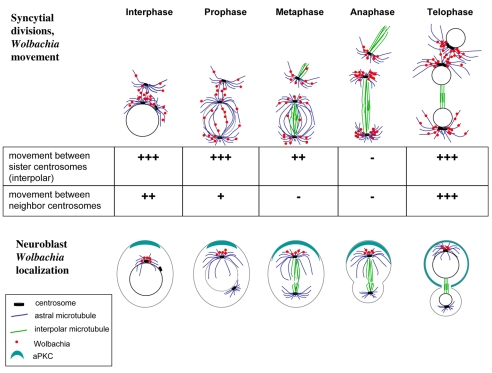

In this study, we further identify the host cellular mechanisms that guide symmetric Wolbachia segregation during the syncytial divisions of early Drosophila embryogenesis. In addition, we identify potential cellular mechanisms that lead to the highly uneven and tissue-specific distributions of Wolbachia later in development. To address the first issue, we developed imaging techniques to analyze live Wolbachia movement during the syncytial divisions. These studies demonstrate that during syncytial mitosis, Wolbachia exhibit cell-cycle-dependent bidirectional movements along microtubules. This results in an exchange of Wolbachia between recently duplicated (sister) and neighboring (non-sister) centrosomes. During anaphase-telophase, when centrosomes duplicate and begin to separate, Wolbachia cluster tightly around the centrosomes and thus are evenly distributed between dividing sister centrosomes. This segregation pattern results in a broad Wolbachia distribution throughout the entire embryo.

To address the second issue of how uneven Wolbachia distribution in various tissues is achieved later in development, we focused on embryonic neurogenesis. In contrast to the syncytial cell cycles, neuroblast cells are highly polarized and undergo asymmetric cell divisions (Egger et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2008). Thus, it is of great interest to determine the segregation pattern of Wolbachia in this cell type. Embryonic neuroblasts are selected from a neuroectoderm layer and delaminate interiorly. Neuroblasts exhibit several aspects of asymmetry: they establish distinct apical-basal cortical protein domains, have an asymmetric mitotic spindle (the apical pole contains a larger centrosome and a more extensive astral microtubule network) and divide asymmetrically along an apical-basal axis to regenerate a large self-renewing neuroblast and a small ganglion mother cell (GMC) (Albertson and Doe, 2003; Kaltschmidt et al., 2000). The GMC undergoes an additional round of division to generate neurons and glia (Goodman and Doe, 1993). The neuroblast apical domain includes the evolutionarily conserved Par3-Par6-aPKC protein complex. After neuroblast delamination, this complex binds the protein Inscuteable, which is required to orient the mitotic spindle along the apical-basal axis (Kraut et al., 1996). This ensures that cell division is orthogonal to the apical-basal polarity determinants. Inscuteable recruits Pins and a heterotrimeric G-protein subunit Gαi, which is required for asymmetric spindle geometry, resulting in asymmetric daughter cells during the neuroblast division (Schaefer et al., 2001). These highly polarized cells are an excellent system to study mechanisms of Wolbachia segregation.

Although Wolbachia are symmetrically localized at sister centrosomes during the syncytial cortical divisions, we demonstrate that Wolbachia are asymmetrically localized at the apical pole of the polarized Drosophila embryonic epithelia cells and neuroblasts. Wolbachia colocalize with apical centrosomes and the apical cortical protein atypical protein kinase C (aPKC). We find that this apical localization is dependent on apical spindle pole microtubules, yet it is independent of extrinsic factors, cortical actin and cortically localized apical determinants. This segregation pattern results in an asymmetric Wolbachia distribution to the self-renewing neuroblast. Thus, Wolbachia is present in the CNS from early embryonic neuroblasts to mature neurons in the adult brain. In accord with Wolbachia maintenance in the embryonic and larval neuroblasts, Wolbachia localize to specific regions of the adult brain and might account for Wolbachia effects on behavior. Finally, we demonstrate that this segregation pattern is less stringent in Popcorn (WPop), which is a virulent Wolbachia strain.

Results

Wolbachia association with the MTOC results in a symmetric segregation pattern during the initial divisions of Drosophila embryogenesis

Wolbachia are associated with the centrosomes in the pre-cellularized, syncycial Drosophila embryo (Callaini et al., 1994; Kose and Karr, 1995; O'Neill and Karr, 1990). In the syncytial embryo, all blastoderm nuclei divide in synchrony through the first 13 mitotic cycles. During early interphase of cycle 14, membranes form between nuclei, dividing them into separate cells. During early gastrulation, cell clusters, known as mitotic domains, undergo synchronous mitosis (Foe, 1989). These cells exhibit symmetric distribution of cortical polarity proteins (such as Dlg, Scrib and aPKC), form equally sized and positioned spindle poles during division, and produce two equally sized daughter cells (Bilder et al., 2000).

To analyze Wolbachia dynamics throughout the syncytial cell cycles, we took advantage of the vital dye Syto-11. This fluorescent nucleic acid dye robustly labels Wolbachia. At long incubation times, Syto-11 labels both Wolbachia and host chromosomes. In fixed images, Wolbachia were readily identified as rod-shaped Syto-11-stained bacteria that were concentrated around centrosomes (Fig. 1). These Syto-11-positive clusters were only present in infected embryos, demonstrating that the dye is specific to Wolbachia and not to other organelles, such as mitochondria. When injected into live embryos and imaged immediately, Syto-11 predominantly labeled Wolbachia and not the host DNA (Fig. 2). Live images obtained with the Syto-11 stain were equivalent to images obtained from fixed analysis (data not shown), indicating that Syto-11 is not influencing the cell cycle or Wolbachia positioning and therefore provides a means of live analysis of Wolbachia dynamics throughout the syncytial cycles.

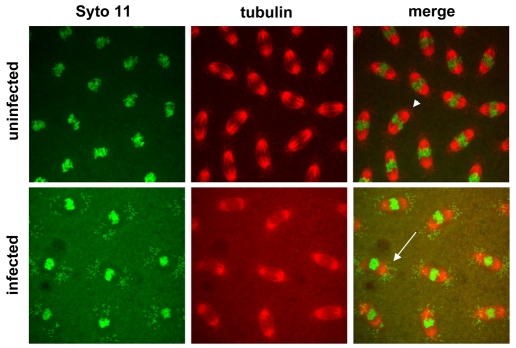

Fig. 1.

Syto 11 labels Wolbachia and nuclear DNA in Drosophila embryos. Fixed uninfected and infected D. simulans embryos stained with Syto 11 (green) to label nucleic acid and α-tubulin (red) to label microtubules. Wolbachia (WRiv) are present as rod-shaped particles (arrow) located at the poles of the mitotic spindle in infected embryos and are absent from uninfected embryos (arrowhead).

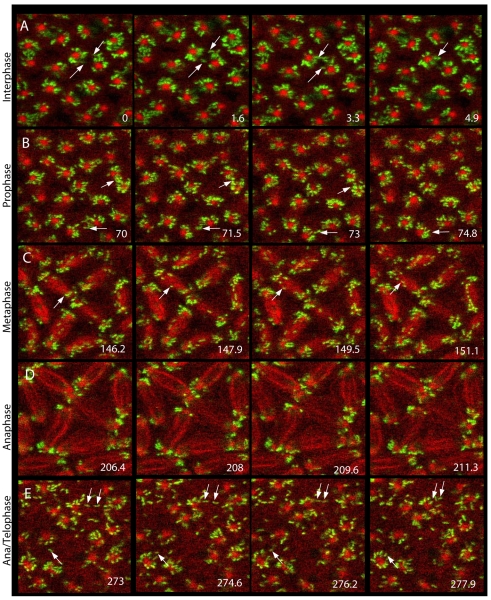

Fig. 2.

Patterns of microtubule-based Wolbachia movement throughout the syncytial cell cycle. Wolbachia movement during consecutive 1.6 second intervals (indicated bottom right) are shown for different phases of the cell cycle (indicated on left). Embryos were injected with Syto-11 to label Wolbachia (green), and Rhodamine-tubulin to label microtubule structures (red). Moving Wolbachia are indicated by arrows. During late interphase (A), prophase (B) and metaphase (C), most Wolbachia movement occurs along microtubules between sister (newly duplicated and divided) centrosomes. Almost no Wolbachia movement is observed during anaphase (D), when Wolbachia form two clusters on the sides of each centrosome. (E) At late anaphase to early telophase, Wolbachia move along astral microtubules between neighboring, non-sister centrosomes. Panels are taken from the supplementary material Movie 1. Analysis was performed with WRiv strain in D. simulans.

Embryos injected with Syto-11 and Rhodamine-tubulin were recorded during the cortical nuclear cycles (supplementary material Movie 1). During interphase, equal amounts of Wolbachia clustered around the separating sister centrosomes (Fig. 2A). A subset of bacteria moved rapidly between separating sister centrosomes (duplicated centrosomes associated with the same nucleus), presumably relying on the array of anti-parallel pole-to-pole microtubules (Fig. 2A, arrows). By contrast, few Wolbachia were observed moving between neighboring, non-sister, centrosomes (centrosomes associated with separate nuclei). This pattern of Wolbachia movement continued throughout prophase and metaphase (Fig. 2B,C, arrows). Upon entry into anaphase, Wolbachia movement ceased and no Wolbachia were found on the central spindle (Fig. 2D). During anaphase, Wolbachia formed two clusters at each spindle pole. The centrosomes duplicated during anaphase and existed as a pair at each pole. Thus, each Wolbachia cluster is probably associated with a member of the centrosome pair. During the late anaphase and early telophase, rapid Wolbachia movements resumed (Fig. 2E, arrows). In contrast to the earlier cell cycle stages, Wolbachia moved between sister centrosomes and neighboring non-sister centrosomes.

The ability of Wolbachia to move rapidly between sister and non-sister centrosomes facilitates a broad and equal Wolbachia distribution throughout the embryo. Consequently, Wolbachia have the potential to locate to many if not all different cell and tissue types as development proceeds. Another key factor in establishing this distribution is that during centrosome duplication at anaphase, Wolbachia are equally partitioned between separating sister centrosomes. To further understand the mechanisms of Wolbachia distribution, we explored the role of microtubules and actin in Wolbachia dynamics.

Wolbachia movement and symmetric distribution to syncytial mitotic products require microtubules

The close association between Wolbachia and microtubules suggests that Wolbachia movement and localization rely on microtubules. To test this, we injected embryos with both Syto-11 and Rhodamine-tubulin to label the Wolbachia and microtubules. We then injected the microtubule inhibitor Colchicine during late anaphase, when Wolbachia typically exhibit extensive trafficking between both sister and non-sister neighboring centrosomes (Fig. 3A, Fig. 4B; supplementary material Movie 2). Wolbachia trafficking between centrosomes immediately stopped in response to the Colchicine treatment (Fig. 3A). The efficacy of the Colchicine treatment was indicated by the lack of visible microtubule formation and the failure in centrosome separation during longer observations (Fig. 4B). In addition, the longer treatment showed that over a period of minutes, the close association of Wolbachia with centrosomes is lost, and clusters of Wolbachia become distributed throughout the cytoplasm encompassing the nuclei (Fig. 4B). This result shows that intact microtubules are required for Wolbachia movement between centrosomes and for maintaining Wolbachia centrosome association.

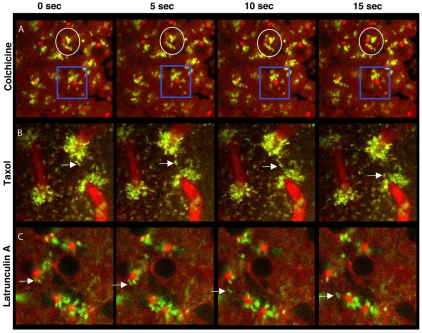

Fig. 3.

Wolbachia movement depends on microtubules but not on actin filaments. Consecutive 5 second intervals of embryos injected with Syto-11 to label Wolbachia (green), with Rhodamine-tubulin to label microtubule-based structures (red) and with inhibitors (indicated to left of panels). (A) Colchicine arrests Wolbachia movement during anaphase. (B) Taxol arrests cells in metaphase and Wolbachia move only between neighboring non-sister centrosomes (arrows). (C) Latrunculin A has no obvious effect on Wolbachia movement during interphase. Colchicine panels are taken from supplementary material Movie 2, Taxol panels from supplementary material Movie 3 and Latrunculin A panels from supplementary material Movie 4. Time frame starts 200 seconds after injection in A and B. Analysis was performed with WRiv strain in D. simulans.

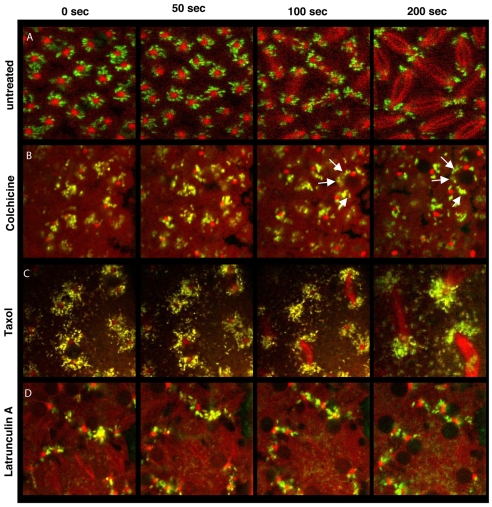

Fig. 4.

Wolbachia association with centrosomes depends on microtubules. Consecutive 50 and 100 second intervals of the same embryos shown in Fig. 2 (untreated) and Fig. 3 (from the same supplementary Movies). (A) Untreated embryos with centrosome-associated Wolbachia. (B) Colchicine treatment at interphase results in loss of Wolbachia concentration around the centrosome and abnormal distribution around the entire nucleus (arrows). (C) Taxol treatment during interphase does not affect Wolbachia centrosome association. (D) Latrunculin A injection leads to unevenly spaced nuclei and prevents centrosome separation, yet does not affect Wolbachia localization to centrosomes. Analysis was performed with WRiv strain in D. simulans.

To determine whether Wolbachia movement and positioning require dynamic microtubules, we treated embryos with Taxol, a microtubule-stabilizing drug. Embryos were first injected with Syto-11 and Rhodamine-tubulin, followed by Taxol injection (supplementary material Movie 3). During prophase, Wolbachia movement in Taxol-treated embryos was similar to that in untreated embryos: Wolbachia moved between sister centrosomes and occasionally between neighboring centrosomes (data not shown). Taxol treatment caused cells to arrest at metaphase (Fig. 4C). During Taxol-induced metaphase arrest, Wolbachia movement occurred along astral microtubules between neighboring, non-sister centrosomes (Fig. 3B, arrows). Long-term Taxol-treatment also showed that Wolbachia remained closely associated with centrosomes (Fig. 4C), demonstrating that dynamic microtubules are not required for maintaining the Wolbachia concentration at the centrosomes. However, movement between sister centrosomes along the pole-to-pole axis was greatly reduced (Fig. 3B).

Wolbachia movement and Wolbachia centrosome positioning during syncytial divisions do not require actin

To determine whether actin is required for Wolbachia movement and positioning during the cortical syncytial divisions, Wolbachia and microtubule dynamics were monitored in real time after injecting Latrunculin A, a potent inhibitor of actin polymerization (Fig. 3C, Fig. 4D; supplementary material Movie 2). Latrunculin A compromises the cortical actin cytoskeleton, disrupts the interphase actin cap and metaphase furrow formation in syncytial embryos, resulting in failed centrosome separation and abnormal nuclear spacing (Cao et al., 2008; Spector et al., 1983).

Latrunculin A was injected during the anaphase-telophase transition, and Wolbachia dynamics were monitored during the following division cycle. Wolbachia movement between neighboring non-sister centrosomes was normal in Latrunculin-A-treated embryos (Fig. 3C, arrows). Longer observation of Latrunculin-A-treated embyos showed that, in contrast to the Colchicine treatment, Wolbachia generally maintained a close association with the centrosomes (Fig. 4D). Similar results were obtained after treatment with Cytochalasin D, another drug that disrupts actin filaments (data not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate that actin filaments are not required for Wolbachia movement between the centrosomes or for Wolbachia positioning at the centrosomes.

Asymmetric distribution and segregation of Wolbachia to the self-renewing stem cell in the embryonic neuroblast divisions

The even Wolbachia partitioning among dividing nuclei in the syncytial embryo ensures that all tissues have the potential to inherit Wolbachia. However, the uneven distribution in adult tissues suggests that this distribution pattern changes during development. To understand the origins of uneven Wolbachia tissue distribution in adults, we examined Wolbachia later during the post-cellularized mitotic divisions at gastrulation (Fig. 5A). During metaphase, anaphase, early and late telophase, Wolbachia were clearly present at both poles. Consequently, as with the syncytial divisions, both daughter cells contained even numbers of Wolbachia (Fig. 5A, arrows).

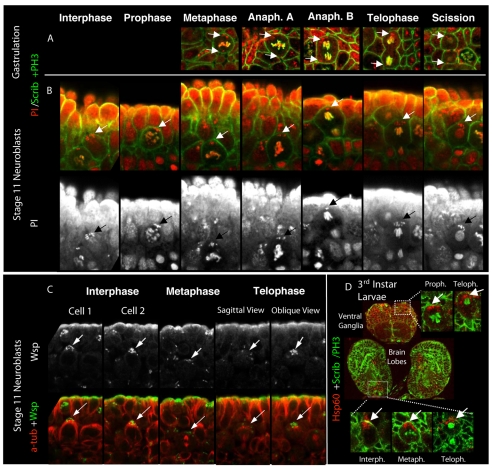

Fig. 5.

Wolbachia localization in cells during Drosophila development. (A) Wolbachia (WPinta in D. simulans) distributes symmetrically in dividing daughter cells during gastrulation (arrows). (B) Neuroblasts from stage 11 embryos show asymmetric distribution and localize apically during host cell mitosis (arrows). Wolbachia are stained with propidium iodide (PI, red), the host cell cortex is marked with anti-scribble (green), and host-cell DNA is stained with anti-phospho-histone3 (PH3, green) in addition to PI staining (yellow in merged image). (C) Wolbachia specifically localize near the microtubule-organizing centers in neuroblasts (arrows). Wolbachia are labeled with anti-Wsp antibody (top row and green in bottom row), microtubules are marked with anti-α-tubulin (red). (D) Wolbachia are distributed asymmetrically in dividing neuroblasts in third-instar larval brains. Inset magnifications of dividing neuroblasts are shown from the ventral ganglia (top) and from the brain lobes (bottom) during different cell cycle stages as indicated. Wolbachia are labeled with anti-Hsp60 (red), host cell cortex is marked with anti-scribble (green), and host cell DNA with anti-PH3 (green). Antibodies against recombinant human heat-shock protein 60 (Hsp60) and Scribble were used to label Wolbachia and the neuroblast apical cortex, respectively.

In contrast to symmetric mitotic divisions of the syncytial and post-cellularization stages, embryonic neurogenesis involves highly polarized cells that undergo asymmetric mitotic divisions to produce daughter cells with different developmental fates (Egger et al., 2008). The apical centrosome enlarges and nucleates a large number of astral microtubules. Subsequently, apical astral microtubles are longer and denser than basal astral microtubles. We discovered that Wolbachia exhibits a striking asymmetric segregation during these neuroblast divisions (Fig. 5B). For this analysis, we took advantage of Wolbachia-infected D. simulans lines originating from collections in Big Sur, California. One of these lines (named WPinta) exhibited a high concentration of Wolbachia in the embryonic neuroblasts and thus facilitated characterization of Wolbachia segregation in this cell type.

In contrast to the symmetric segregation patterns, Wolbachia were almost exclusively localized at the apical cortex during interphase in stage 11 neuroblasts. (Fig. 5B, arrows in first panel). This position was maintained as the neuroblast progresses into prophase and through telophase and cytokinesis (Fig. 5B). Consequently, nearly all Wolbachia were segregated to the apical daughter cell after cytokinesis. These images also show the size asymmetry during neuroblast division: the apical daughter cell was much larger than the basal daughter cell (Fig. 5B, right panel). After cell division, the apical cell self-renews as a neuroblast stem cell, whereas the basal cell forms the ganglion mother cell that will ultimately produce neurons and/or glial cells (Wu et al., 2008). Thus, asymmetric Wolbachia localization to the apical cell cortex is likely to ensure that bacteria will mostly remain in the self-renewing neuroblast during embryonic neurogenesis and infection will persist in neuronal stem cells through later development stages. By contrast, embryonic and larval neurons are likely to be less infected as a result of this segregation pattern.

To examine Wolbachia localization in dividing neuroblasts relative to spindle dynamics, we performed double immunofluorescence analysis using antibodies against the Wolbachia surface protein (Wsp) and against tubulin (Fig. 5C). Consistent with the propidium iodide staining results, Wolbachia specifically localized to the apical pole during interphase and maintained this apical association during metaphase and telophase. In addition, Wolbachia concentrated near the apical MTOC and apical astral microtubules (Fig. 5C, arrows).

We next examined whether asymmetric Wolbachia localization in dividing neuroblasts is maintained into late embryogenesis and larval developmental stages. Embryonic neuroblasts repeatedly divide and reduce in size. Neuroblasts then undergo a stage of quiescence before they are reactivated during larval stages. During the early larval stages, neuroblasts grow and asymmetrically divide to produce a self-renewing daughter neuroblast and a daughter that will give rise to a variety of specialized neural cells in the third instar larval brain (Ceron et al., 2001). We stained third-instar larval ventral ganglia and brain lobes, and examined Wolbachia distribution in dividing neuroblasts. Wolbachia showed nearly exclusive localization to the Scribble-enriched apical cortex throughout the entire cell cycle in both locations (Fig. 5D, insets, arrows). These results indicate that Wolbachia segregate asymmetrically to neuroblast stem cells throughout embryonic and larval neurogenesis.

Apical Wolbachia localization is independent of division axis in polarized epithelia cells

Neuroblasts and epithelia originate from the neuroectodermal layer at the embryo periphery (Kuchinke et al., 1998; Wodarz and Huttner, 2003). Similarly to neuroblasts, epithelial cells have a distinct cortical polarity, consisting of apical and basolateral domains (Hutterer et al., 2004; Suzuki and Ohno, 2006; Tepass et al., 2001). We found that in polarized epithelial cells, Wolbachia localized apically during interphase, similarly to neuroblasts (Fig. 6A-E, arrowheads). Interestingly, Wolbachia even localized apically during neuroblast delamination from the neuroectodermal layer (supplementary material Fig. S1). Unlike neuroblasts, however, epiblasts divided parallel (and not perpendicular) to the neuroectoderm, and they divided symmetrically based on cell size, spindle pole size and cortical protein localization. We examined Wolbachia position and segregation during mitosis in these polarized, but symmetrically dividing cells to understand the origin of asymmetric distribution. Wolbachia distribution was equal between the two spindle poles during symmetric epiblast divisions (Fig. 6F, arrowheads). Adjacent cells, a non-dividing polarized epithelial cell and two neuroblasts, all showed asymmetric apical Wolbachia localization (Fig. 6F, arrow). This result illustrates that epithelial cell asymmetry during interphase determines apical Wolbachia localization.

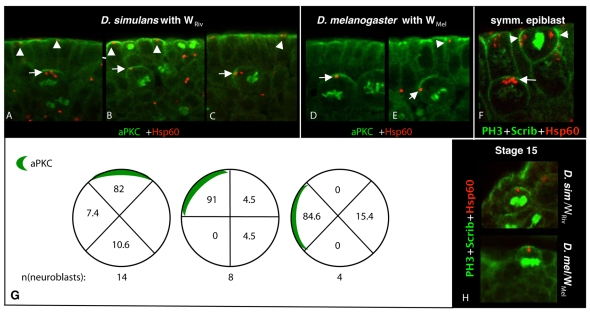

Fig. 6.

Wolbachia localization in neuroblasts and epithelial cells (WRiv in D. simulans and WMel in D. melanogaster). (A-E) Wolbachia localize to the aPKC-dense area in neuroblasts (arrows) and epithelial cells (arrowheads) in WRiv in D. simulans (A-C) and in WMel in D. melanogaster (D,E). Wolbachia are stained with anti-Hsp60 (red), aPKC is labeled with anti-aPKC (green), and host cell DNA with anti-PH3 (green). (F) Wolbachia are distributed evenly between symmetrically dividing epiblasts (arrowheads) and apically localized in the neuroblast below (arrow). Wolbachia are labeled with anti-Hsp60 (red), dividing cells with anti-scribble (green), and host DNA with anti-PH3 (green). (G) Quantification of Wolbachia localization (%) in relation to aPKC distribution in neuroblasts of wild-type embryos with naturally differing neuroblast orientation. (H) Wolbachia localization near the aPKC crescent in Stage 15 neuroblast after dissociation from the epithelial layer. Staining as in panels A-E.

Wolbachia colocalizes with aPKC

Embryonic neuroblast polarity is influenced by both extrinsic epithelia signals and by cell-intrinsic factors such as cortical cell polarity and asymmetric spindle poles (Siegrist and Doe, 2006; Siegrist and Doe, 2007). The position of the apical protein domain is induced by the surrounding epithelia cells and generally aligned with the apical poles of the surrounding cells (Siegrist and Doe, 2006), but apical protein crescents are occasionally mispositioned toward the lateral cortex. Proteins of the highly conserved apical Par3 (Bazooka)-Par6-aPKC (Par) complex are interdependent for complex formation and maintenance at the apical cortex (Wu et al., 2008). During prophase, the apical Par protein complex recruits a second protein complex that includes heterotrimeric G proteins (Pins-Gαi complex) and ultimately regulates spindle orientation and geometry (Fuse et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2008). During metaphase, the Pins-Gαi complex can also be apically localized by microtubules (Siegrist and Doe, 2005; Siegrist and Doe, 2007).

We analyzed Wolbachia colocalization with the cortical protein aPKC as a marker for cell-intrinsic apical factors. For these experiments, we used the well-characterized and sequenced strains Wolbachia Riverside (WRiv) in D. simulans (Salzberg et al., 2005), and Wolbachia melanogaster (WMel) in D. melanogaster (Wu et al., 2004). These are frequently used laboratory strains, and although there are fewer Wolbachia per cell than in WPinta, both strains also exhibit the asymmetric apical localization that was observed with the newly isolated WPinta strain (Fig. 6A-E). We labeled aPKC to identify the Par complex and showed that both WRiv (Fig. 6A-C) and WMel (Fig. 6D-E) strongly colocalized with the aPKC crescent in the neuroblasts (arrows). The colocalization was particularly striking in Fig. 6C,E, in which the aPKC crescent was mis-positioned laterally relative to the surrounding epithelia. In these instances, Wolbachia localized to the cortical region associated with the mislocalized aPKC crescent rather than to the cortical region that is apical relative to the surrounding epithelium.

Quantification of Wolbachia and aPKC colocalization in naturally occurring neuroblasts with correctly or mis-positioned apical proteins is shown in Fig. 6G. Roughly half of the neuroblasts (14 of 26) had apically localized aPKC with most (82%) of the Wolbachia cells localizing apically. About one third of the neuroblasts had the aPKC crest oriented 45 degrees off the apical-basal axis with respect to the surrounding epithelium. In those cells, almost all Wolbachia (91%) aligned with aPKC rather than with the `true' apical position relative to surrounding cells. Few neuroblasts (4 of 26) had the aPKC crest oriented 90 degrees off the apical-basal axis. Even in those neuroblasts, most Wolbachia (84%) localized with the crest, and none with the `true' apical position relative to the surrounding epithelium.

The data indicate that Wolbachia maintain strong colocalization with the aPKC crescent, even if the crescent is not aligned with true apical position, as determined by the surrounding cells. These results suggest that the extrinsic epithelia cells do not provide the primary cue for Wolbachia localization. Further support for the hypothesis that Wolbachia localization is predominantly determined by cell-intrinsic signals stems from the observation that WMel and WRiv maintained colocalization with aPKC at late embryonic and larval stages, when neuroblasts have dissociated from the epithelial layer (Fig. 5D, Fig. 6H) and no longer receive extrinsic cues.

Taken together, the results indicate that Wolbachia localization is strongly influenced by cell polarity and that Wolbachia positioning is influenced by cell-intrinsic cues such as cortical protein domains and spindle pole microtubules.

Microtubules but not actin are essential for apical Wolbachia localization

The Par complex determines the apical-basal orientation as soon as neuroblasts delaminate from the neuroectoderm (Hutterer et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2008). Subsequent apical localization of the Pins-Gαi complex is either guided by signaling from the Par complex, or by apical microtubules (Siegrist and Doe, 2007). To determine whether apical Wolbachia localization in dividing neuroblasts depends on microtubules, we treated living embryos with Colcemid and assayed Wolbachia distribution. Propidium Iodide and anti-aPKC antibody were used to stain for Wolbachia and the apical cortex (Fig. 7A). Colcemid disrupted microtubule organization, as evidenced by a lack of a mitotic spindle in treated but not in control metaphase neuroblasts (Fig. 7A, bottom row). In mock-treated embryos, 90% of Wolbachia bacteria located to the apical cortex (Fig. 7A, top row schematics). After Colcemid treatment, cell orientation became randomized as the spindles depolymerized. After 30 and 60 minutes of treatment, an aPKC crescent was still defined, although the orientation relative to the surrounding tissue had rotated in some instances. After 30 minutes of Colcemid treatment, only 79% of Wolbachia remained apical with respect to aPKC localization. Basal and lateral localization increased from 9% to 21%. After a 60 minute treatment, the portion of Wolbachia maintained at the apical cortex was further reduced to 46% while basal-lateral localization increased to 54% (compared with 85% and 14%, for mock-treated embryos). These studies demonstrate that microtubules have an important role in Wolbachia localization to the apical crescent.

Fig. 7.

Wolbachia localization depends on intact microtubules but not on actin filaments. (A) Top panel shows Wolbachia quantification (%) in neuroblasts in the indicated areas in relation to aPKC staining. Middle panels show representative images of the treatment indicated above the schematics. The lower panels show tubulin staining only of the same images as the middle panels. Wolbachia (red puncta) disperse from the apical cortex after microtubule disruption (Colcemid treatment) for 30 and 60 minutes, and no longer colocalize with the aPKC crescent (green crescent, arrow). Actin depolymerization (Latrunculin A treatment) does not disrupt microtubules, but causes spindle rotation and fused spindles (arrows in lower panels), and disperses aPKC (green) from the apical cortex. Wolbachia continue to localize to the spindle poles (arrows). Wolbachia are stained with propidium iodide (PI, red), aPKC is stained with anti-aPKC (green) and tubulin with anti-α-tubulin (blue and lower panels). Spindle poles are indicated by arrows in the mock and Latrunculin A treatments. (B) Quantification of Wolbachia localization with respect to the centrosome after no treatment, after mock treatment (DMSO in Schneider's medium) and after Latrunculin A treatment. Wolbachia (% ± s.e.) are quantified in the areas labeled with letters indicated on the schematic.

We next determined whether cortical actin has a role in localizing Wolbachia to the apical cortex. As opposed to microtubules, actin microfilaments are required to anchor asymmetrically distributed proteins (such as the Par complex) during neuroblast mitosis (Broadus and Doe, 1997). Neuroblasts were treated with the F-actin-depolymerizing drug Latrunculin A, which has been shown to eliminate the cortical actin network and completely destabilize apical protein complexes (Barros et al., 2003). After Latrunculin A treatment for 60 minutes, aPKC was mislocalized and dissociated from the neuroblast cortex (Fig. 7A, right panels, lack of green crescent). Yet, in spite of aPKC dispersion, Wolbachia (Fig. 7A, arrows in merged panels) still localized to the MTOC of the spindles (Fig. 7A, arrows in bottom row). Wolbachia exhibited an apical localization in 77% of the neuroblasts compared with 85% for the controls. As expected, Latrunculin-A-treated cells failed to divide, resulting in cells with multiple nuclei, ectopic spindles poles and misoriented spindles (Fig. 7A, right α-tubulin panels). Wolbachia still localized to the spindle poles in these abnormal cells, even when aPKC was absent, and spindles were grossly misaligned with respect to surrounding cells.

Wolbachia localization around the MTOC was quantified in untreated, mock-treated and Latrunculin-A-treated neuroblasts (Fig. 7B). Wolbachia localization was scored relative to the MTOC, as apical in close cortex proximity (A), apical (B), basal (D), lateral (C), or randomly in cell cytoplasm (E). Wolbachia localization in either of the zones remained unchanged after Latrunculin A treatment, although the treatment resulted in multinucleate cells, loss of telophase, loss of epithelial columnar morphology and polarity (not shown). These data indicate that Wolbachia localization to the spindle pole does not require an intact cortical cytoskeleton, the presence of apically localized cortical proteins such as aPKC, or the alignment of astral microtubules with the apical cell pole. The results support a model in which the apical spindle pole is a key factor for asymmetric Wolbachia localization.

Asymmetric Wolbachia segregation depends on asymmetric neuroblast division

In asymmetric neuroblast division, the Par complex and the apical Pins-Gαi complex function in redundant pathways to induce asymmetric spindles and daughter cells (Cai et al., 2003; Wodarz, 2005) by suppressing basal spindle development (Fuse et al., 2003). Pins binds to Gαi in the heterotrimetic G-protein complex and causes the release of the Gβ13F subunit. Mutation of any of these proteins (Pins, Gαi, Gβ13F) causes defects in asymmetric protein localization (Insc, Numb, Miranda) and results in largely asymmetric neuroblast division (Fuse et al., 2003; Schaefer et al., 2001; Yu et al., 2003). Overexpression of Gαi, which binds and depletes the Gβγ pool, also leads to the loss of polarized localization of Gαi and Pins, Miranda, Numb, resulting mislocalized spindles, and terminating in neuroblast division into equally sized daughter cells (Schaefer et al., 2001). More specifically, Gαi overexpression leads to the formation of abundant astral microtubules at both centrosomes, rather than just at the apical centrosome as seen during wild-type neuroblast division (Yu et al., 2003).

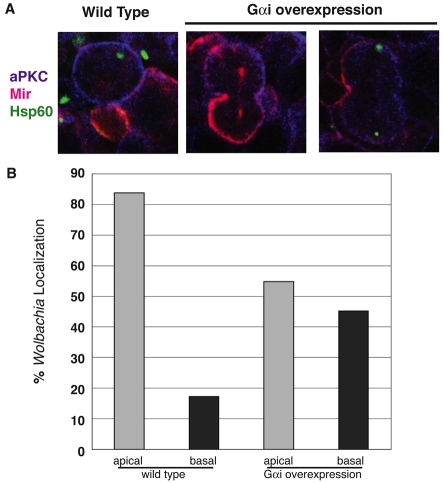

We used GαI-overexpressing embryos (stage 11) to analyze whether Wolbachia apical localization in neuroblasts depends on Gβγ-dependent induction of asymmetric proteins and spindle poles. In accordance with Schaefer and colleagues (Schaefer et al., 2001), we observed that Miranda, a basal cortical protein, was no longer restricted to the basal cell in these neuroblasts (Fig. 8A). Analysis of Wolbachia localization showed a random distribution in dividing telophase neuroblasts (Fig. 8B). This result clearly indicates that Wolbachia localization to the apical centrosome depends on the induction of asymmetry in the neuroblast divisions.

Fig. 8.

Gαi overexpression in stage 11 embryos abolishes asymmetric division in neuroblasts and randomizes Wolbachia distribution. (A) Asymmetrically dividing neuroblast in the wild type and symmetrically dividing neuroblasts in Gαi-overexpressing embryos. Miranda (pink), a basally located cortical protein is localized properly in the wild type, but mislocalized to the mitotic spindle (middle panel) and to the apical and basal cortex (middle and right panels) in Gαi-overexpressing cells. Wolbachia localization (green) is apical in the wild type, and either absent (middle panel) or random (right panel) in Gαi-overexpressing cells. (B) Quantification of Wolbachia localization in asymmetrically dividing wild-type neuroblasts (n=23 cells) and in symmetrically dividing neuroblasts (n=18 cells).

Wolbachia strains differ in the extent to which they localize apically in embryonic epithelia cells and neuroblasts

We examined Wolbachia neuroblast localization patterns in WRiv, WMel and WPop. The latter strain is known to overproliferate in adult brains and cause neurodegeneration (Min and Benzer, 1997). Similarly to WRiv and WMel, WPop exhibited apical Wolbachia localization in epithelia cells of stage 9 and 10 embryos (Table 1, supplementary material Fig. S1). WRiv showed the strongest Wolbachia localization to the apical domain (93%), whereas in WMel and WPop, two thirds of the bacteria were in the apical quarter (Table 1). While neuroblasts were delaminating from the epithelium, WRiv maintained a strong apical localization, whereas WPop exhibited a weaker apical localization (Fig. S1). In interphase neuroblasts, all three strains exhibited apical Wolbachia localization, but WPop showed weaker retention (57%) in the apical region than WRiv (95%) and WMel (71%) (Table 1, supplementary material Fig. S1). Quantification of Wolbachia revealed significantly more WRiv per neuroblast in D. simulans (7.2 bacteria per cell) than WMel or WPop in D. melanogaster (1.6 and 2.4 bacteria per cell, respectively, Table 1). Taken together, these data highlight strain differences in the abundance and in the extent to which Wolbachia segregate asymmetrically in the neuroblasts.

Table 1.

Strain differences in apical Wolbachia localization in stage 9 and 10 embryo interphase neuroblasts and epithelia cells

| Wolbachia localization | WRiv in Drosophila simulans | WMel in Drosophila melanogaster | WPop in Drosophila melanogaster | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interphase neuroblasts | 100% in apical third | 95 | 71 | 57 |

| <50% in apical third | 5 | 13 | 19 | |

| >50% in apical third | 0 | 16 | 25 | |

| N (embryos) | 4 | 5 | 5 | |

| n (cells) | 119 | 45 | 53 | |

| Epithelial cells | All in apical quarter | 93 | 58 | 59 |

| Apical and lateral | 4 | 26 | 35 | |

| Apical, lateral, basal | 0 | 15 | 5 | |

| N (embryos) | 3 | 4 | 4 | |

| n (cells) | 162 | 79 | 79 | |

| No. of Wolbachia per infected cell | 7.2 | 1.6 | 2.4 |

Wolbachia localization in adult brain

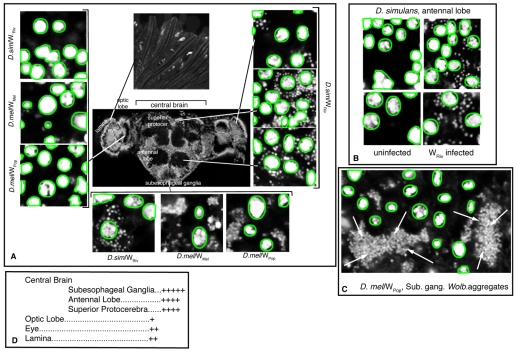

To examine the consequences of asymmetric Wolbachia distribution during development, we determined abundance of Wolbachia the adult brain (Fig. 9). Wolbachia were detected by the DNA stain Syto11 and seen as small dots surrounding the Syto-11-stained host nuclei (Fig. 9B). We found that the Wolbachia titer differed significantly among brain regions (Fig. 9D). Images of WRiv in D. simulans showed that Wolbachia density was highest in the central brain, containing subesophageal ganglia (Fig. 9A, bottom left panel), antennal lobes and the superior protocerebrum (Fig. 9A, right insets, bottom and middle panels). Bacteria densities were lower in the lamina (Fig. 9A, right inset, top panel) and eye (top inset). Very few bacteria were found in the optic lobe (Fig. 9A, left insets, top panel). Wolbachia strains WMel and WPop in D. melanolgaster also exhibited low titers in the optic lobe (Fig. 9A, left insets, middle and bottom panels), and were more abundant in the subesophageal ganglia (Fig. 9A, bottom insets, middle and right panels). Among the three strains, WPop exhibited the greatest concentration in the adult brain (Fig. 9A, bottom insets). WPop formed large aggregates in the brain and appeared to be more clumped than the other bacteria strains (Fig. 9C, arrows).

Fig. 9.

Wolbachia are most abundant in the central brain. (A) Image of a male Wolbachia-infected adult brain, anterior view. Most bacteria can be seen in the subesophageal ganglia (bottom insets, hosts and bacteria strains are indicated), in the antennal lobe (right insets, bottom image) and in the superior protocerebrum (right insets, middle image). Fewer bacteria are found in the optic lobe in all three examined strains (left insets, hosts and bacteria strains are indicated), in the eye (right insets, top image) and in the lamina (top inset). Unless otherwise indicated, the images are WRiv in D. simulans. (B) Wolbachia are visible as small puncta next to the host nuclei in D. simulans. (C) WPop form large aggregates in the subesophageal ganglia (arrows). Host nuclei are circled in green in A-C. (D) Subjective quantification of Wolbachia abundance in the different brain areas of a WSim-infected D. simulans fly.

Discussion

Symmetric and asymmetric Wolbachia segregation patterns

The studies presented here define two distinct patterns of Wolbachia segregation during Drosophila development (Fig. 10). As has been previously reported (Callaini et al., 1994; Kose and Karr, 1995; O'Neill and Karr, 1990), we found that Wolbachia undergo a symmetric division pattern and segregate evenly throughout the syncytial divisions in the developing Drosophila embryo. However, later in embryogenesis and larval development we found a distinct and highly asymmetric segregation pattern, in which Wolbachia are preferentially inherited to only one of the two daughter cells. Both segregation patterns rely on a close association of Wolbachia with microtubules and centrosomes. Although the symmetric segregation broadly disseminated Wolbachia throughout all embryonic cell lineages, the later asymmetric segregation pattern in the post-cellularized embryo concentrated Wolbachia in specific cell lineages. This is in agreement with findings that Wolbachia is widely but unevenly distributed throughout the tissues of adult insects (Dobson, 2003; Ijichi et al., 2002; McGarry et al., 2004).

Fig. 10.

Schematic of Wolbachia symmetric and asymmetric segregation patterns. During syncytial divisions (top), Wolbachia move along astral microtubules migrating between sister and non-sister centrosomes during interphase and prophase. During metaphase, less movement occurs between sister centrosomes, and no movement occurs between neighboring centrosomes. We propose that Wolbachia movement occurs predominantly on astral microtubules (depicted in blue). During anaphase, Wolbachia do not move, but maintain a close association with the separating centrosomes, resulting in a symmetric segregation pattern. Wolbachia movement resumes during telophase. During embryonic neuroblast divisions (bottom), Wolbachia are concentrated at the apical centrosome. This concentration is achieved primarily through an association with the robust astral microtubules arrays of apical centrosome. After centrosome duplication, the new centrosome moves basally, but does not establish robust astral microtubules. Wolbachia do not move to the basal centrosome. This results in an asymmetric segregation and maintenance of Wolbachia in the self-renewing neuroblast stem cell.

Cell-cycle regulation of Wolbachia movement

Live analysis revealed that during the syncytial division cycles, Wolbachia use microtubules to rapidly migrate between sister and non-sister centrosomes. From prophase through early anaphase, Wolbachia migrated on the pole-to-pole microtubules between sister centrosomes. Little movement was observed during late anaphase and early telophase. During the telophase-interphase transition, Wolbachia relied on astral microtubules to migrate between neighboring, non-sister centrosomes (Fig. 10). This extensive migration between centrosomes promotes a broad Wolbachia distribution throughout the embryo. Given the extensive movement of Wolbachia throughout much of the syncytial cycle, the stable and tight association with the centrosomes during early anaphase is particularly striking. Significantly, this coincides with centrosome duplication and separation. The stable association ensures that equal numbers of Wolbachia associate with the duplicated and separating sister centrosomes.

Previous work also demonstrated Wolbachia localization near the centrosome and suggested that this was the mechanism by which Wolbachia are widely distributed throughout the syncytial embryo (Callaini et al., 1994; Kose and Karr, 1995). Our studies confirm this finding and further demonstrate that shuttling between sister and non-sister centrosomes provides an additional distribution mechanism. One possible advantage of Wolbachia moving between both sister and non-sister centrosomes during the mitotic cycle is that this might facilitate a more rapid and broader bacteria distribution throughout the dividing nuclei of the entire embryo.

Microtubule-dependent Wolbachia movement

In accord with previous studies (Callaini et al., 1994; Kose and Karr, 1995), concentration of Wolbachia near the centrosomes required intact microtubules. Work in the Drosophila oocyte has demonstrated that microtubule-dependent Wolbachia movement during mid-oogenesis relies on the minus-end motor protein dynein for proper anterior positioning (Ferree et al., 2005). This raises the possibility that the concentration at the centrosome might be achieved by Wolbachia continuously engaging dynein, a minus-end-directed motor protein. It should be noted, however, that we also observe Wolbachia movement away from the MTOC. Work in the Drosophila oocyte during later stages of oogenesis has shown that Wolbachia also engage the plus-end motor protein kinesin to migrate to and concentrate at the posterior cortex (Serbus et al., 2008; Serbus and Sullivan, 2007). Therefore, the observed Wolbachia movement toward and away from the centrosomes might be the result of Wolbachia alternatively engaging dynein and kinesin. Surprisingly, Taxol treatment, which stabilizes microtubules, dramatically reduces Wolbachia movement on overlapping pole-to-pole microtubules, but not along astral microtubules connecting neighboring centrosomes. This raises the possibility that Wolbachia movement between sister centrosomes is different from that between neighboring non-sister centrosomes. Between sister centrosomes, Wolbachia might associate with the ends of dynamic pole-to-pole microtubules that are Taxol stabilized. Wolbachia might move using motors along astral microtubules, which continue to operate during Taxol treatment. This possibility is supported by studies suggesting that Wolbachia associate with microtubule plus-ends during spermatid elongation (Riparbelli and Callaini, 1998; Riparbelli et al., 2007), and via kinesin KLP67 on astral microtubules during early embryogenesis (Pereira et al., 1997). Another possibility is that Wolbachia only move on astral microtubules (see below).

The bacterium Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) also moves toward the spindle poles before cytokinesis (Fedorova et al., 2007) and segregates to both daughter cells during host cell mitosis. After mitosis, the bacteria move to the cortical region over the entire cell. The role of microtubules and motor proteins in Bradyrhizobium movement has not been determined and no other bacteria have been reported to segregate to the poles during host cell mitosis. It will be interesting to examine whether the mechanisms used by Bradyrhizobium and Wolbachia take advantage of the same host factors during their segregation into daughter cells.

Wolbachia localize apically in epithelia and neuroblast cells

After cellularization, Wolbachia are evenly distributed throughout the epithelial cell layer resulting from symmetric segregation during cell division in the Drosophila embryo. In epithelial cells, Wolbachia become apically located during interphase. When epithelial cells divide symmetrically (perpendicular to the apical-basal axis), Wolbachia redistribute to both of the spindle poles during metaphase, and segregate symmetrically. As neuroblasts delaminate from interphase epithelial cells, Wolbachia remained localized to the thin apical stalk that stretches into the epithelial layer (supplementary material Fig. S1), indicating that neuroblasts inherit apical Wolbachia from the neuroectoderm.

Asymmetric segregation of Wolbachia in neuroblast cells

In striking contrast to the symmetric Wolbachia segregation during syncytial divisions and gastrulation, and in symmetrically dividing epithelia, we discovered that Wolbachia exhibit a highly asymmetric segregation pattern in neuroblasts of embryos and larvae. After delamination from the epithelial layer, neuroblasts undergo a spindle rotation, resulting in the spindle being oriented along the apical-basal axis (Egger et al., 2008). Neuroblast cell division then results in segregation of both Wolbachia and apical determinants to the self-renewing apical daughter cell. The basal GMC daughter lacks Wolbachia and differentiates into larva neurons and glia cells. During the subsequent neuroblast divisions throughout embryo and larval stages, Wolbachia are continuously maintained at the apical cortex and segregate to the apical neuroblast daughter cell. Although Wolbachia strains vary in the extent to which they exhibit asymmetric segregation, all examined strains exhibit this pattern of segregation. Thus, in contrast to the distributive symmetric centrosome-based segregation pattern during the syncytial divisions, this highly asymmetric pattern of Wolbachia inheritance concentrates Wolbachia in specific neuroblast lineages. Presumably, this Wolbachia distribution results in an overall low infection rate of the larval and adult brain, but it ensures that at least a few glia cells in the adult brain, the ones resulting from the final differentiation of the neuroblast, are infected and reside in the adult CNS.

Possible mechanisms for Wolbachia localization

To undergo a switch from symmetric to asymmetric segregation, Wolbachia must either interact with different host factors as development proceeds, or with host factors that act differently during development. Either of these possibilities is likely, because studies of Wolbachia in oocytes have shown that the bacteria can engage different motor and cortical proteins during oocyte development (Ferree et al., 2005; Serbus and Sullivan, 2007).

A common theme of Wolbachia movement and position in the neuroblast and syncytial divisions is their colocalization with astral microtubules. It has been postulated previously that Wolbachia only locate to astral and not to spindle microtubules in syncytial embryos (Callaini et al., 1994; Kose and Karr, 1995). If, during syncytial divisions, astral microtubules reach from one pole to the opposite pole during prophase and metaphase but not during anaphase, it could explain the pole-to-pole Wolbachia movement during the early mitotic phases and the lack of movement between sister centrosomes in the later stages of mitosis. Similarly during Taxol treatment, when the distance between poles (sister centrosomes) increases (Figs 3B, 4C and 10), Wolbachia ceased movement between the sister centrosomes, but not between the closer neighboring centrosomes. During asymmetric neuroblast division, the basal centrosome builds fewer and shorter astral microtubules than the apical centrosome, and only after migration away from the apical centrosome (Rebollo et al., 2007; Rusan and Peifer, 2007; Wodarz, 2005; Yu et al., 2003). If Wolbachia only travel along astral microtubules toward the MTOC, the short basal microtubules might be insufficient to allow Wolbachia transport to the basal centrosome (Fig. 10).

In both interphase neuroblasts and epithelial cells, Wolbachia colocalize with the apical aPKC complex. However, our data show that Wolbachia and aPKC rely on different mechanisms for their apical localization: disruption of cortical actin results in severe aPKC mislocalization, but produces only minor disruptions in apical Wolbachia positioning. By contrast, apical Wolbachia localization in neuroblasts is dependent on intact microtubules. Treatment with microtubule inhibitors resulted in a significant, but not complete, loss of Wolbachia from the apical cortex, whereas most aPKC remained localized. One possibility is that in neuroblasts, Wolbachia interaction with the apical centrosome depends on compositional differences between the two centrosomes. For example, the basal centrosome has a reduced concentration of γ-tubulin and centrosomal proteins CP60 and CP190 from anaphase on (Kaltschmidt et al., 2000). The basal centrosome MTOC activity is also reduced and only accumulates pericentriolar material (PCM) at mitosis onset (Rebollo et al., 2007).

In asymmetric neuroblast divisions, astral microtubules are also involved in re-enforcing cortical polarity of the apical determinants Pins and Gαi via kinesin Khc-73 that binds to apically located Discs large (Dlg) (Siegrist and Doe, 2005). When microtubules are de-polymerized by Colchicine, cortical polarity is still established, but correct spindle alignment is only achieved in two thirds of the neuroblasts (Siegrist and Doe, 2005). If these microtubule-dependent apical determinants are involved in Wolbachia localization, this might explain why Wolbachia are largely, but not completely mislocalized after Colchicine treatment. Interestingly, Dlg is also localized to the apical margin of the lateral membrane in epithelial cells, where it induces apical localization of other proteins (Bilder et al., 2000) and might contribute to the apical Wolbachia localization in epithelia cells.

Functional significance of Wolbachia asymmetric segregation

The polarized localization and asymmetric segregation of Wolbachia in the embryonic neuroblast stem cells contrasts with the pattern of Wolbachia segregation observed in the female germline stem cells. Division of the germline stem cell (GSC) produces a self-renewing daughter and a daughter to differentiate into a mature oocyte (Fuller and Spradling, 2007). Wolbachia are found in the GSC and in the daughter cells that will develop into the mature oocyte (Serbus et al., 2008). The mechanism for Wolbachia distribution into both the stem and daughter cells, is not known. The functional significance of this segregation pattern is clear, because it enables Wolbachia to be stably transmitted into oocytes throughout the life of the insect. It is not clear whether male GSCs are infected with Wolbachia, but they are visible in early stage spermatocysts and in surrounding somatic tissues (Clark et al., 2003). During mitotic divisions during sperm development, Wolbachia are distributed unevenly in the cytoplasm, which results in cysts with both infected and uninfected cells (Clark et al., 2002; Clark et al., 2003; Riparbelli et al., 2007). The only common mechanism of Wolbachia localization during sperm development, oogenesis, and observations described in this paper, is that Wolbachia associates with astral microtubules during the meiotic prophase and telophase during sperm development. However, during male meiotic metaphase and anaphase, Wolbachia no longer associate with astral microtubules but instead locate to the spindle midzone (Riparbelli et al., 2007).

The functional significance of the highly asymmetric segregation of Wolbachia in the neuroblast stem cells is not immediately obvious. Possible insight comes from examining the fate of the neuroblasts. At the conclusion of embryogenesis, neuroblasts undergo a period of quiescence until reactivation at larval stages when they undergo asymmetric divisions similar to those in embryogenesis. Asymmetric divisions during larval development rely on the same apical-basal determinants, as described for the embryonic neuroblasts, with some minor differences (Slack et al., 2006). As with the embryonic neuroblasts, we found that Wolbachia exhibit an asymmetric segregation pattern such that they are maintained in the self-renewing larval neuroblast stem cells. These stem cells ultimately divide into daughter cells that develop into the adult central nervous system. Thus by maintaining an apical position in the embryonic and larval neuroblast stem cells, this ensures that at least some Wolbachia will eventually localize to some cells in the adult nervous system during the final neuroblast differentiation. After localization to the adult brain, Wolbachia appear to reproduce preferably in some areas of the brain. Larval brains are predicted to be less infected as a result of the asymmetric segregation pattern.

It is possible that the presence of Wolbachia in specific host brain regions alters insect behavior. Recent studies demonstrate that Wolbachia influences olfactory-cued locomotion (Peng et al., 2008) and mating behavior (Champion de Crespigny and Wedell, 2006; Gazla and Carracedo, 2009; Koukou et al., 2006). It is well known that distinct elements of the Drosophila brain govern certain behavior, especially well characterized are sex-specific behaviors such as courtship (Hall, 1979; Villella and Hall, 2008). Our images show that Wolbachia is not distributed evenly in different brain regions. The selective infection of the areas in the central brain might be related to the Wolbachia-induced effects on Drosophila behavior. Expression of behavior-related genes are found to be spatially and temporarily regulated in the developing brain (Lee et al., 2000). Wolbachia might influence these expression patterns. The higher Wolbachia titer in specific adult brain areas is probably the result of targeting during development and increased Wolbachia reproduction in those regions, because the titers are significantly higher than those we observed in neuroblasts. This discrepancy is especially noticeable in the WPop strain in D. melanogaster, which has a lower titer than WSim in D. riverside throughout development, but overproliferates in the adult brain, as has been observed previously (Min and Benzer, 1997).

Strain variability

Although all three Wolbachia strains examined exhibited a pronounced apical localization in the embryonic neuroblasts, the stringency of apical localization varied among the strains. WRiv exhibited the tightest apical concentration with 95% of infected cells having all Wolbachia in the apical third of interphase neuroblasts. WPop have the least-stringent localization with only 57% of the interphase neuroblasts exhibiting complete apical Wolbachia localization. Thus, in WPop, although most Wolbachia are maintained in the self-renewing neuroblast, significant numbers are also segregated to the differentiating neuronal daughter cells. This is likely to alter the tissue distribution of WPop relative to other Wolbachia strains. It is tempting to speculate that the less-stringent apical localization of WPop is partly responsible for the over-replication of Wolbachia in adult brains. One possibility is that replication of the apically localized cortical Wolbachia is strictly controlled, whereas these controls are not in place in the basally localized Wolbachia.

Materials and Methods

Fly strains

Drosophila stocks were maintained on standard molasses and cornmeal medium. The D. simulans strain with WPinta was collected at the University of California Big Creek Reserve (Big Sur, CA). Drosophila melanogaster with WPop, D. simulans with WRiv and D. melanogaster with WMel are labstocks. UAS-Gai and UAS-GaiQ205L were generously provided by the Knoblich (IMBA, Vienna, Austria) and Hooper laboratories (University of Colorado, Boulder, CO) and expressed with a V32-Gal4 driver.

In vivo microscopy

Drosophila embryos were prepared for microinjection according to a standard protocol (Tram et al., 2001). Embryos were injected sequentially with Syto-11 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) to visualize Wolbachia and Rhodamine-tubulin (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO) to label microtubules. Syto-11 was diluted 1:10 with water, microfuged for 2 minutes at 4°C, and injected near the embryo cortex. Rhodamine-tubulin was injected undiluted into the embryo interior. Time-lapse microscopy was performed on a Leica DM IRB inverted microscope equipped with the TCS SP2 confocal system. For time-lapse analysis, images were taken every 1.6 seconds or every 5 seconds, as indicated.

Live inhibitor studies

For live examination of Wolbachia motility in syncytial embryos, inhibitors were injected into embryos approximately 5 minutes after the injection of Syto-11 and Rhodamine-tubulin. Colchicine was used at 1 mM in water, Taxol was used at 58.5 mM in fresh DMSO, Cytochalasin D was used at 1 mM, and Latrunculin A was used at 1 mM in fresh DMSO.

Fixation and antibody staining

Larval brains from third-instar larvae were dissected in PBS (with 0.1% Triton X-100) and fixed in PEM (100 mM PIPES, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgSO4) with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes. 3- to 7-hour-old Drosophila embryos were collected and fixed in PEM with 4.5% paraformaldehyde and 50% heptane for 20 minutes. Embryos were de-vitellinized with 100% methanol as previously described (Rothwell and Sullivan, 2000). The following antibodies were used: anti-Hsp60 (1:200, Sigma) with secondary anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (1:150; Molecular Probes). This antibody against recombinant human Hsp60 labels the Wolbachia homolog without crossreacting with Drosophila proteins (Hoerauf et al., 2000; McGraw et al., 2002; Taylor and Hoerauf, 1999) and stains better than the anti-Wsp antibody in some fixation processes. We also generated a rabbit polyclonal antibody against Wsp. This was achieved by cloning wsp from WMel Wolbachia, omitting the signal sequence. A Wsp-Gst fusion protein was expressed in E.coli. E. coli proteins were separated on a SDS gel, the Wsp-Gst fusion protein was cut out, and used for rabbit antibody production (Open Biosystems). The secondary antibody was anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:150, Molecular Probes). Anti-Scrib polyclonal antibody was raised against the C-terminal of Scrib fused to GST (Albertson and Doe, 2003) with secondary anti-mouse Cy5 (1:150, Molecular Probes); Rabbit anti-PH3 antibody (1:1000, Upstate Biotech, Waltham, MA) was used with secondary anti-mouse Cy5 (1:150, Molecular Probes); anti-aPKC (1:1000, SC biotech) was used with secondary anti-mouse Cy5 (1:150, Molecular Probes); anti-α-tubulin (1:150, Sigma) was used with secondary anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (1:150, Molecular Probes). The Rabbit anti-Miranda antibody was used at 1:200 (Chris Doe, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR). All antibody staining was performed for at least 8 hours at 4°C. For propidium iodide (PI) staining, fixed larval brains were incubated in RNase (10 mg/ml PBS), rotated at 4°C overnight (or at 37°C for 3 hours) and mounted in mounting medium containing PI (10 μg/ml PI, 1× PBS, 70% glycerol in water). For Syto11 staining of adult brain, flies were dissected in PBS, transferred to a watch glass and incubated in Syto11 (Molecular Probes, 1:100 dilution in PBS) for 20 minutes in the dark. Non-fixed brains were directly transferred to a slide and imaged. Drug treatment for fixed-imaged embryos was performed as described previously (Knoblich et al., 1997). Bleach (50%)-dechorinated, washed embryos were incubated for 30 minutes in a 1:1 mixture of n-heptane and 200 μM Latrunculin A in Scheider's medium. Latrunculin A was dissolved in DMSO, which also served as the mock control. Embryos were then fixed in 5% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes, and then devitellinized with methanol. Staining with antibodies was carried out overnight in PBST at 4°C. Colcemid (5 μg/ml) treatment during neurogenesis was performed similarly, and samples were incubated for the indicated times. Fixed embryos and larval brains were analyzed with the TCS SP2 confocal system on the Leica DM IRB inverted microscope.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/122/24/4570/DC1

We thank the members of the Sullivan laboratory for helpful comments on the manuscript. We thank the Doe laboratory for anti-scribble and anti-Miranda antibodies. We thank the Knoblich and Hooper laboratories for sharing and sending the UAS-Gαi strains. In addition, we would like to thank Kurt Meg and Mark Readdie for help, advice and access to the facilities at the Big Creek Reserve. Special thanks to Pinta for not chewing up all the fly vials. We are thankful for funding from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) and from NIH (5RO1GM046409). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Albertson, R. and Doe, C. Q. (2003). Dlg, Scrib and Lgl regulate neuroblast cell size and mitotic spindle asymmetry. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 166-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros, C. S., Phelps, C. B. and Brand, A. H. (2003). Drosophila nonmuscle myosin II promotes the asymmetric segregation of cell fate determinants by cortical exclusion rather than active transport. Dev. Cell 5, 829-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder, D., Li, M. and Perrimon, N. (2000). Cooperative regulation of cell polarity and growth by Drosophila tumor suppressors. Science 289, 113-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadus, J. and Doe, C. Q. (1997). Extrinsic cues, intrinsic cues and microfilaments regulate asymmetric protein localization in Drosophila neuroblasts. Curr. Biol. 7, 827-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y., Yu, F., Lin, S., Chia, W. and Yang, X. (2003). Apical complex genes control mitotic spindle geometry and relative size of daughter cells in Drosophila neuroblast and pI asymmetric divisions. Cell 112, 51-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaini, G., Riparbelli, M. G. and Dallai, R. (1994). The distribution of cytoplasmic bacteria in the early Drosophila embryo is mediated by astral microtubules. J. Cell Sci. 107, 673-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J., Albertson, R., Riggs, B., Field, C. M. and Sullivan, W. (2008). Nuf, a Rab11 effector, maintains cytokinetic furrow integrity by promoting local actin polymerization. J. Cell Biol. 182, 301-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceron, J., Gonzalez, C. and Tejedor, F. J. (2001). Patterns of cell division and expression of asymmetric cell fate determinants in postembryonic neuroblast lineages of Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 230, 125-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion de Crespigny, F. E. and Wedell, N. (2006). Wolbachia infection reduces sperm competitive ability in an insect. Proc. Biol. Sci. 273, 1455-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. E., Veneti, Z., Bourtzis, K. and Karr, T. L. (2002). The distribution and proliferation of the intracellular bacteria Wolbachia during spermatogenesis in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 111, 3-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. E., Veneti, Z., Bourtzis, K. and Karr, T. L. (2003). Wolbachia distribution and cytoplasmic incompatibility during sperm development: the cyst as the basic cellular unit of CI expression. Mech. Dev. 120, 185-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. E., Anderson, C. L., Cande, J. and Karr, T. L. (2005). Widespread prevalence of Wolbachia in laboratory stocks and the implications for Drosophila research. Genetics 170, 1667-1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. E., Bailey-Jourdain, C., Ferree, P. M., England, S. J., Sullivan, W., Windsor, D. M. and Werren, J. H. (2008). Wolbachia modification of sperm does not always require residence within developing sperm. Heredity 101, 420-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, S. L. (2003). Reversing Wolbachia-based population replacement. Trends Parasitol. 19, 128-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, S. L., Bourtzis, K., Braig, H. R., Jones, B. F., Zhou, W., Rousset, F. and O'Neill, S. L. (1999). Wolbachia infections are distributed throughout insect somatic and germ line tissues. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 29, 153-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger, B., Chell, J. M. and Brand, A. H. (2008). Insights into neural stem cell biology from flies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 363, 39-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorova, E. E., de Felipe, M. R., Pueyo, J. J. and Lucas, M. M. (2007). Conformation of cytoskeletal elements during the division of infected Lupinus albus L. nodule cells. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 2225-2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferree, P. M., Frydman, H. M., Li, J. M., Cao, J., Wieschaus, E. and Sullivan, W. (2005). Wolbachia utilizes host microtubules and Dynein for anterior localization in the Drosophila oocyte. PLoS Pathog. 1, e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foe, V. E. (1989). Mitotic domains reveal early commitment of cells in Drosophila embryos. Development 107, 1-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman, H. M., Li, J. M., Robson, D. N. and Wieschaus, E. (2006). Somatic stem cell niche tropism in Wolbachia. Nature 441, 509-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, M. T. and Spradling, A. C. (2007). Male and female Drosophila germline stem cells: two versions of immortality. Science 316, 402-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuse, N., Hisata, K., Katzen, A. L. and Matsuzaki, F. (2003). Heterotrimeric G proteins regulate daughter cell size asymmetry in Drosophila neuroblast divisions. Curr. Biol. 13, 947-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazla, I. N. and Carracedo, M. C. (2009). Effect of intracellular Wolbachia on interspecific crosses between Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans. Genet. Mol. Res. 8, 861-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, C. S. and Doe, C. Q. (1993). Embryonic Development of the Drosophila Central Nervous System . Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Hall, J. C. (1979). Control of male reproductive behavior by the central nervous system of Drosophila: dissection of a courtship pathway by genetic mosaics. Genetics 92, 437-457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerauf, A., Volkmann, L., Hamelmann, C., Adjei, O., Autenrieth, I. B., Fleischer, B. and Buttner, D. W. (2000). Endosymbiotic bacteria in worms as targets for a novel chemotherapy in filariasis. Lancet 355, 1242-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutterer, A., Betschinger, J., Petronczki, M. and Knoblich, J. A. (2004). Sequential roles of Cdc42, Par-6, aPKC, and Lgl in the establishment of epithelial polarity during Drosophila embryogenesis. Dev. Cell 6, 845-854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ijdo, J. W., Carlson, A. C. and Kennedy, E. L. (2007). Anaplasma phagocytophilum AnkA is tyrosine-phosphorylated at EPIYA motifs and recruits SHP-1 during early infection. Cell Microbiol. 9, 1284-1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ijichi, N., Kondo, N., Matsumoto, R., Shimada, M., Ishikawa, H. and Fukatsu, T. (2002). Internal spatiotemporal population dynamics of infection with three Wolbachia strains in the adzuki bean beetle, Callosobruchus chinensis (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ireton, K. (2007). Entry of the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes into mammalian cells. Cell Microbiol. 9, 1365-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltschmidt, J. A., Davidson, C. M., Brown, N. H. and Brand, A. H. (2000). Rotation and asymmetry of the mitotic spindle direct asymmetric cell division in the developing central nervous system. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 7-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblich, J. A., Jan, L. Y. and Jan, Y. N. (1997). The N terminus of the Drosophila Numb protein directs membrane association and actin-dependent asymmetric localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 13005-13010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kose, H. and Karr, T. L. (1995). Organization of Wolbachia pipientis in the Drosophila fertilized egg and embryo revealed by an anti-Wolbachia monoclonal antibody. Mech. Dev. 51, 275-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukou, K., Pavlikaki, H., Kilias, G., Werren, J. H., Bourtzis, K. and Alahiotis, S. N. (2006). Influence of antibiotic treatment and Wolbachia curing on sexual isolation among Drosophila melanogaster cage populations. Evolution Int. J. Org. Evolution 60, 87-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut, R., Chia, W., Jan, L. Y., Jan, Y. N. and Knoblich, J. A. (1996). Role of inscuteable in orienting asymmetric cell divisions in Drosophila. Nature 383, 50-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchinke, U., Grawe, F. and Knust, E. (1998). Control of spindle orientation in Drosophila by the Par-3-related PDZ-domain protein Bazooka. Curr. Biol. 8, 1357-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G., Foss, M., Goodwin, S. F., Carlo, T., Taylor, B. J. and Hall, J. C. (2000). Spatial, temporal, and sexually dimorphic expression patterns of the fruitless gene in the Drosophila central nervous system. J. Neurobiol. 43, 404-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry, H. F., Egerton, G. L. and Taylor, M. J. (2004). Population dynamics of Wolbachia bacterial endosymbionts in Brugia malayi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 135, 57-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw, E. A., Merritt, D. J., Droller, J. N. and O'Neill, S. L. (2002). Wolbachia density and virulence attenuation after transfer into a novel host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2918-2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMeniman, C. J., Lane, R. V., Cass, B. N., Fong, A. W., Sidhu, M., Wang, Y. F. and O'Neill, S. L. (2009). Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection into the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science 323, 141-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min, K. T. and Benzer, S. (1997). Wolbachia, normally a symbiont of Drosophila, can be virulent, causing degeneration and early death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 10792-10796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill, S. L. and Karr, T. L. (1990). Bidirectional incompatibility between conspecific populations of Drosophila simulans. Nature 348, 178-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y., Nielsen, J. E., Cunningham, J. P. and McGraw, E. A. (2008). Wolbachia infection alters olfactory-cued locomotion in Drosophila spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 3943-3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A. J., Dalby, B., Stewart, R. J., Doxsey, S. J. and Goldstein, L. S. (1997). Mitochondrial association of a plus end-directed microtubule motor expressed during mitosis in Drosophila. J. Cell Biol. 136, 1081-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo, E., Sampaio, P., Januschke, J., Llamazares, S., Varmark, H. and Gonzalez, C. (2007). Functionally unequal centrosomes drive spindle orientation in asymmetrically dividing Drosophila neural stem cells. Dev. Cell 12, 467-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riparbelli, M. G. and Callaini, G. (1998). gamma-Tubulin is transiently associated with the Drosophila oocyte meiotic apparatus. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 75, 21-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riparbelli, M. G., Giordano, R. and Callaini, G. (2007). Effects of Wolbachia on sperm maturation and architecture in Drosophila simulans Riverside. Mech. Dev. 124, 699-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, W. F. and Sullivan, W. (2000). Fluorescent Analysis of Drosophila Embryos . Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Rusan, N. M. and Peifer, M. (2007). A role for a novel centrosome cycle in asymmetric cell division. J. Cell Biol. 177, 13-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzberg, S. L., Hotopp, J. C., Delcher, A. L., Pop, M., Smith, D. R., Eisen, M. B. and Nelson, W. C. (2005). Serendipitous discovery of Wolbachia genomes in multiple Drosophila species. Genome Biol. 6, R23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, M., Petronczki, M., Dorner, D., Forte, M. and Knoblich, J. A. (2001). Heterotrimeric G proteins direct two modes of asymmetric cell division in the Drosophila nervous system. Cell 107, 183-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbus, L. R. and Sullivan, W. (2007). A Cellular Basis for Wolbachia Recruitment to the Host Germline. PLoS Pathog. 3, e190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbus, L. R., Casper-Lindley, C., Landmann, F. and Sullivan, W. (2008). The genetics and cell biology of Wolbachia-host interactions. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42, 683-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]