Abstract

Objective

Brazil accounts for ∼70% of injection drug users (IDU) receiving HAART in low/middle income countries. We evaluated the impact of HAART availability/access on AIDS-related mortality among IDU versus men who have sex with men (MSM).

Design

Nationwide analysis on Brazilian IDU and MSM diagnosed with AIDS in 2000-2006.

Methods

Four national information systems were linked and Cox regression was used to assess impact of HAART availability/access on differential AIDS-related mortality.

Results

Among 28,426 patients, 6,777 died during 87,792 person-years of follow-up. Compared to MSM, IDU were significantly less likely to be receiving HAART, to have ever had determinations for CD4 or viral load. After controlling for confounders, IDU had a significantly higher risk of death (AHR: 1.94; 95% CI: 1.84-2.05). Among the subset that had at least one CD4 and viral load determination, higher risk of death among IDU persisted (HR: 1.82; 95% CI: 1.58-2.11). Non-white ethnicity significantly increased this risk, while prompt HAART uptake after AIDS diagnosis reduced the risk of death. After controlling for spatially-correlated survival data, AIDS-related mortality remained higher in IDU than in MSM.

Conclusions

Despite free/universal HAART access, differential AIDS-related mortality exists in Brazil. Efforts are needed to identify and eliminate these health disparities.

Keywords: HIV, AIDS, Survival, HAART, drug user

Introduction

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) significantly improves the prognosis of HIV-infected persons by reducing HIV viral load, increasing CD4+ cell levels and delaying progression to AIDS, ultimately reducing mortality rates.1 Since reduced HIV viral load also appears to be important for reducing HIV transmission2, increasing availability and adherence to HAART has also gained attention as a potential HIV prevention strategy.3

However, inequalities in health outcomes among people living with HIV/AIDS continue to be reported in high, middle and low income countries such diverse as the United States, Brazil and Uganda.4-9 A high proportion of AIDS deaths in the developed world are due to poor access to HAART among disadvantaged/marginalized populations.10,11

Disparities in HIV-related mortality might be due to differential access to HAART and retention in treatment among specific subpopulations, such as drug users.12,13 Compared with other populations living with HIV/AIDS, injecting drug users (IDU) usually have lower utilization and adherence to HAART and are more likely to experience virologic failure, contributing to a rapid disease progression.14-16 Studies in the United States indicate that IDU tend to initiate HAART at a more advanced stage of HIV infection compared to other populations.15,17-19 However, in the U.S, health insurance is a major barrier to care and may explain many of these associations. The active use of illicit drugs, and limited mental health care and substance abuse management (especially methadone substitution therapy), as well as constant incarceration/detention of drug users may also explain delays or interruptions in HAART use among IDU.20-22

Brazil was the first middle-income country to provide full access to HAART, laboratory monitoring and clinical care at no cost at the point of health care delivery to any eligible patient, since 1996.23 As of June 2008, approximately 190,000 patients were receiving HAART in Brazil, making it the most comprehensive HIV treatment initiative implemented thus far in a middle-income country, worldwide.24,25 Globally, Brazil provides treatment and care to approximately 70% of IDUs receiving HAART, which is the largest number of HIV+ IDU outside high income countries.13

Despite being one of the first countries to implement free and universal access to HAART, no nation-wide evaluation has been conducted using longitudinal information of all PLWHA receiving HIV treatment and care. A recent small study analyzed data from 170 patients (68 IDU) from Brazil, aiming to compare the utilization of HIV-related healthcare by IDU and other populations.26 According to this study, IDU were less likely to receive ARV prescriptions and requests for CD4 lymphocyte and viral load counts compared to non-IDU. Healthcare utilization increased over time in the non-IDU group, parallel to the implementation of the Brazilian health policy of universal access to HIV-treatment, but this favorable trend was not observed among IDU.

Herein, we report differences in survival from AIDS diagnosis by transmission risk category, within the unique Brazilian setting. This study evaluated all patients receiving treatment in the country between 2000 and 2006, therefore avoiding selection bias present in other studies that included partial subsets of the country's population living with HIV/AIDS.

Methods

This study utilized four databanks comprising different longitudinal information of all PLWHA under treatment and care through the Brazilian public health system. These databanks contain the core information of Brazil's surveillance system, and are specified as follows: socio-demographic information on AIDS cases (SINAN); data from exams conducted in public laboratories, particularly TCD4+/TCD8 lymphocyte counting and HIV viral load (SISCEL), information about monthly ARV refills and therapeutic regimen changes over time (SICLOM), and the date and cause/s of death (SIM). Data from the entire population of PLWHA with diagnosis between 2000 and 2006, whose transmission category was injecting drug use or homo/bisexual contact were extracted from those databanks and merged.

Databank linkage

In Brazil, although private health insurance covers costs with laboratorial exams, accredited physicians and hospitals, it does not cover costs with medications. Therefore, the number of PLWHA not receiving ARVs through the public health system is negligible. Affluent PLWHA tend to be notified on SICLOM and SINAN databanks, although are rarely found on SISCEL (i.e. they use their private insurance to reimburse them for exams performed at private labs). On the other hand, PLWHA from low socio-economic strata have less access to successive laboratory follow-up and ARV refills. Therefore, those patients tend to be more efficiently and rapidly included on SINAN-AIDS and SIM databanks than on SISCEL and SICLOM.

Since differential information is found in each databank, comprehensive analyses must use data from all databanks. As a first step, we standardized the different databanks, in order to have exactly the same variable names, lengths and format throughout all databanks. An identification key was created for each patient, therefore permitting his unique identification in the different databanks.

The National AIDS Program is in charge of the management of three of the abovementioned databanks (SINAN-AIDS, SISCEL, and SICLOM). The merging of such databanks originated a new databank, comprising socio-demographic information and information on exposure category (SINAN-AIDS), successive laboratorial exams (SISCEL), and monthly refill of ARV medication and ARV therapeutic regimens switches (SICLOM).

In a subsequent step, we performed the linkage of this merged databank with information from the National Mortality System (SIM). SIM identifies each death through the patient full name, his mother's name, and cause(s) of death, but lacks alphanumeric identifiers. Therefore, we linked the merged AIDS databank with SIM using Recklink 3.0 software,27 which is based on probabilistic record linkage.28,29

The above linkage yielded a comprehensive databank with information on PLWHA under treatment through the Brazilian public health system, aged 18 years or older and with a confirmed AIDS diagnosis. For this analysis, participants were included if they were diagnosed (medical assessment of AIDS) between January 1, 2000 and August 31, 2006, and if their most probable route of HIV infection was IDU or male homosexual contact. Patients whose most probable route of HIV infection was heterosexual contact were not included because we aimed to analyze differences in survival from AIDS diagnosis between a population known to have higher rates of initiation and adherence to HAART (MSM) with a population known to have the lowest rates of initiating HAART, worldwide: IDU. Females were excluded on the analysis, since they corresponded to less than 3% of the IDU AIDS cases.

The final databank comprised the following covariates: date of birth, most probable route of HIV infection, ethnicity, date of AIDS diagnosis, dates of initiation of HAART, CD4 counts and viral load values in successive visits (with the corresponding dates), and cause(s) and date of death.

Statistical analyses

The primary endpoint was mortality from AIDS-related causes during the follow-up period. Survival was calculated as the time elapsed from date of AIDS diagnosis until the date of AIDS-related death (or censoring). All other deaths were censored on the date of death, and individuals who stayed alive were censored at the end of data collection period (August 31, 2006). Since analyses were based on secondary data, we did not have access to information on clinical visits; therefore we were not able to calculate losses to follow-up.

Kaplan-Meier curves were fitted to compare probabilities of survival according to selected covariates using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard regression modeling was used to examine covariates associated with survival among the following: age at AIDS diagnosis, HIV exposure category (IDU vs. MSM), first CD4 lymphocyte count, HAART uptake, first HIV-RNA viral load exam, and ethnicity. The likelihood ratio test was used to select variables to be entered in the Cox models, adjusting for potential confounders and testing for effect modification. The assumption of proportional hazards was evaluated through the examination of Schoenfeld residuals.30

Hazard rates are strongly influenced by selection effects operating in the population (e.g. higher availability of referral centers in a given locality), and individuals surviving up to a certain time will on average be less frail than the original population, therefore unobserved individual heterogeneity (or frailty) was also taken into account.31-34

With 8.5 million square kilometers and 185 million inhabitants, Brazil is the largest and most populous country in Latin America, and faces deep health and socio-economic differences within each region. In an attempt to account for the heterogeneity between and within different Brazilian regions and localities, analyses were repeated with the introduction of a random effect term to assess the potential association between survival times within a cluster – state or municipality of residency – using gamma-distributed frailty.35

Analyses were conducted with the entire population, and with a subgroup of patients who received at least one CD4 count determination and one HIV-1 RNA viral load determination, to evaluate the existence of differential survival patterns among patients who sought earlier diagnosis and treatment.

Analyses were performed in R.36 To estimate confidence intervals for Cox's proportional hazards models, robust methods were used. Maximum penalized likelihood estimation was used to estimate frailty models.

Results

Characteristics of the patients

Of the 28,426 patients included in the study, 43% were IDU and the overall mean age at AIDS diagnosis was 34.8 years (SD: 8.5). Ethnicity and age were similar comparing IDU and MSM. Although all patients had a confirmed AIDS diagnosis, only 28.3% were actually receiving HAART in the beginning of the study period (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of patients included on the study, according to transmission category (n=28,426).

| Transmission category | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male homosexual contact | Injecting drug use | |

| Subjects (N, %) | 28,426 | 16,195 (57.0) | 12,231 (43.0) |

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| Mean ± SD | 34.8 ± 8.5 | 35.3 ± 9.1 | 34.2 ± 7.4 |

| Range | 18 – 89 | 18 – 89 | 18 - 81 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 10,433 (36.7) | 5,620 (34.7) | 4,813 (39.4) |

| Mulatto (mixed white and black) | 3,915 (13.8) | 2,625 (16.2) | 1,290 (10.5) |

| Black | 1,657 (5.8) | 838 (5.2) | 819 (6.7) |

| Others (Asian, Indigenous…) | 118 (0.4) | 75 (0.5) | 43 (0.4) |

| Unspecified | 12,303 (43.3) | 7,037 (43.5) | 5,266 (43.1) |

| HAARTa uptake (N, %) | |||

| Never received HAART | 20,395 (71.7) | 11,138 (68.8) | 9,257 (75.7) |

| Received (or is still under) HAART | 8,031 (28.3) | 5,057 (31.2) | 2,974 (24.3) |

| Deathsc | 6,777 (23.8) | 2,727 (16.8) | 4,050 (33.1) |

| Have ever done at least one CD4 exam | |||

| No | 13,822 (48.6) | 6,984 (43.1) | 6,838 (55.9) |

| Yes | 14,604 (51.4) | 9,211 (56.9) | 5,393 (44.1) |

| CD4 lymphocytes (first exam available)d | |||

| Mean ± SD | 297.4 ± 213.4 | 309.2 ± 217.2 | 277.3 ± 205.2 |

| Range | 1 – 1,778 | 1 – 1,758 | 1 – 1,778 |

| Have ever done at least one HIV-1 RNA Viral load exam | |||

| No | 16,424 (57.8) | 8,775 (54.2) | 7,649 (62.5) |

| Yes | 12,002 (42.2) | 7,420(45.8) | 4,582 (37.5) |

| HIV RNA in plasma, log10 copies/ml (first exam available)e | |||

| Mean ± SD | 4.01 ± 1.17 | 4.05 ± 1.16 | 3.94 ± 1.18 |

| Range | 1.70 – 6.85 | 1.70 – 6.85 | 1.70 – 6.80 |

Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy;

Persons-year;

All causes of death;

Among those who have done at least one CD4 exam;

Among those who have done at least one Viral load exam;

The overall median survival after AIDS diagnosis was 2.45 years (IQR: 2.09-2.86). During the follow-up period, 6,777 (23.8%) patients were known to have died from AIDS-related deaths. The proportion of deaths was 2.4 times higher among IDU than among MSM (33.1% vs. 16.8%; p<0.0001) (Table 1). Patients who accessed accredited health units had better survival rates compared to those who did not receive ARVs. Compared to MSM, IDU were significantly less likely to be receiving HAART at recruitment (24.3% vs. 31.2%; p<0.001), less likely to have ever received at least one CD4 count (44.1% vs. 56.9%; p<0.001), and were less likely to have ever had at least one HIV-1 RNA viral load determination (62.5% vs. 54.2%; p<0.001).

Among those who had conducted at least one CD4 and HIV-1 RNA viral load exam (N=12,002), IDU had lower mean CD4 count (277.3 vs. 309.2; p<0.001), but had similar HIV-1 RNA viral load counts: 3.94 vs. 4.05 log10 copies/ml (compared to MSM) (Table 1).

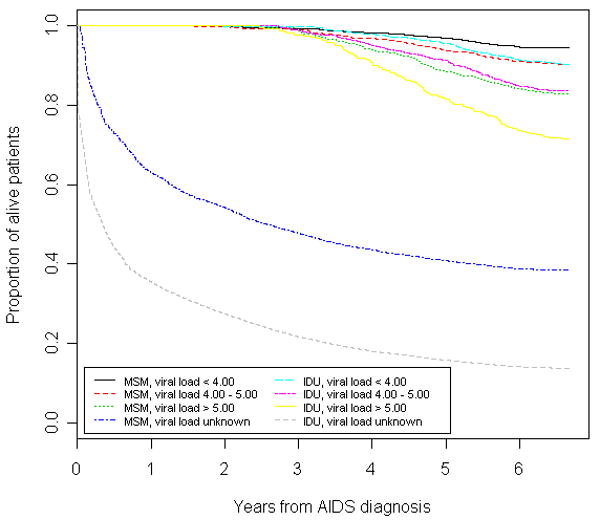

In Kaplan-Meier analyses stratified by HIV-1 RNA viral load on baseline, IDU had significantly lower survival since AIDS diagnosis, when compared to MSM (p<0.001 for each comparison). Survival since AIDS diagnosis was lower among those who had never had an HIV-1 RNA viral load determination, followed by those with first HIV-1 RNA test >5.00 log10 copies/ml, those with results between 4.00 and 5.00 log10 copies/ml, and patients with HIV-1 RNA below 4.00 log10 copies/ml, and survival among IDU was lower than among MSM for all viral loads strata (Figure 1). Patients who did not have at least one CD4 determination during the study period had the worst survival following AIDS diagnosis, followed by those with CD4 counts bellow 200 cells/mm3, and those with CD4 counts higher than 200 cells/mm3.

Figure 1. Time from AIDS to death by transmission category stratified by HIV-1 RNA (Iog10 copies/ml).

Predictors of survival

In univariate analysis, exposure category was a strong predictor of survival: risk of death for IDU was roughly 2 times higher than that of MSM. Predictors of longer survival included HAART uptake and CD4 counts >350 cells/mm3 at diagnosis. Patients with an HIV-RNA viral load >5log10 copies/ml at diagnosis had a higher risk of death, as well as non-white patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios of mortality according to baseline variables among IDU and MSM diagnosed with AIDS. Brazil, 2000-2006.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

|---|---|---|

| Predictor | HR (95%CI)a | HR (95%CI)# |

| Exposure category | ||

| MSMb | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| IDUc | 1.96 (1.86 – 2.06)*** | 1.77 (1.68 – 1.86)*** |

| Age (per year of increase) | 1.02 (1.01 – 1.02)*** | 1.02 (1.02 – 1.03)*** |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-white | 1.32 (1.23 – 1.41)** | 1.39 (1.30 – 1.49)*** |

| Unknown | 0.63 (0.59 – 0.67)*** | 0.64 (0.60 – 0.68)*** |

| HAART uptake after AIDS diagnosis | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 0.14 (0.13 – 0.16)*** | 0.52 (0.46 – 0.58)*** |

| CD4 cell count at diagnosis (×106/l) | ||

| <200 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 200-350 | 0.27 (0.23 – 0.31)** | 0.31 (0.26 – 0.37)*** |

| >350 | 0.24 (0.20 – 0.27)*** | 0.30 (0.26 – 0.35)*** |

| Unknown | 3.11 (2.86 – 3.37)*** | 2.23 (1.99 – 2.50)*** |

| HIV-1 RNA (log10 copies/ml) | ||

| <4.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 4.00-5.00 | 1.91 (1.64 – 2.22)** | 1.48 (1.27 – 1.72)** |

| >5.00 | 3.77 (3.25 – 4.37)*** | 2.44 (2.10 – 2.84)*** |

| Unknown | 7.29 (6.52 – 8.16)*** | 1.67 (1.46 – 1.92)** |

Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval);

Men who have sex with men;

Injection Drug Users;

Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy;

Antiretroviral Therapy;

p-value<0.001;

p-value=0.0000;

Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for all variables listed in the table.

In multivariate analysis, the increased risk of death observed in IDU compared to MSM persisted. As expected, biological predictors such as higher CD4 cells counts and lower viral load remained a strong predictor of survival, as well as HAART uptake (Table 2). Results were similar when restricted to the subsample of patients who have conducted at least one CD4 determination and one HIV-1 RNA viral load determination (Table 3). However, caution should be exercised in generalizing these findings, since the subsample accounted for only 40% of the overall sample.

Table 3.

Hazard ratios of mortality according to baseline variables among IDU and MSM diagnosed with AIDS who have conducted at least one CD4 count and one HIV-1 RNA viral load determination. Brazil, 2000-2006 (N=11,340)

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

|---|---|---|

| Predictor | HR (95%CI)a | HR (95%CI)# |

| Exposure category | ||

| MSMb | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| IDUc | 1.87 (1.62 – 2.16)*** | 1.82 (1.58 – 2.11)** |

| Age (per year of increase) | 1.02 (1.01 – 1.02)** | 1.02 (1.01 – 1.02)** |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-white | 1.39 (1.16 – 1.65)** | 1.32 (1.10 – 1.57)* |

| Unknown | 0.80 (0.67 – 0.95)* | 0.99 (0.83 – 1.17) |

| HAART uptake after AIDS diagnosis | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 0.42 (0.36 – 0.48)*** | 0.46 (0.39 – 0.54)*** |

| CD4 cell count at diagnosis (×106/l) | ||

| <200 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 200-350 | 0.32 (0.26 – 0.38)*** | 0.36 (0.30 – 0.44)*** |

| >350 | 0.32 (0.26 – 0.38)*** | 0.41 (0.34 – 0.49)*** |

| Unknown | NA | NA |

| HIV-1 RNA (log10 copies/ml) | ||

| <4.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 4.00-5.00 | 1.61 (1.35 – 1.92)** | 1.36 (1.13 – 1.63)** |

| >5.00 | 2.82 (2.37 – 3.35)*** | 2.09 (1.75 – 2.51)** |

| Unknown | NA | NA |

Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval);

Men who have sex with men;

Injection Drug Users;

Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy;

Antiretroviral Therapy;

p-value≤0.01;

p-value<0.001;

p-value=0.0000;

Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for all variables listed in the table.

Upon multivariate Cox frailty regression that accounted for a random effect due to the place of residence (Table 4), the increased risk of death observed in IDU compared to MSM remained higher than the estimates found in our multivariate model. Both CD4 cells counts and viral load remained as significant predictors of survival, as well as HAART uptake, and non-white participants remained having a higher risk of death. As expected, older participants had a slightly higher risk of death. The same patterns were observed on multivariate Cox frailty regression, accounting for a random effect due to the municipality of residence, although with a slightly smaller variance.

Table 4.

Hazard ratios of mortality according to baseline variables among IDU and MSM diagnosed with AIDS, adjusted by state or municipality frailty effect. Brazil, 2000-2006.

| Frailty: State of Residence | Frailty: Municipality of Residence | |

|---|---|---|

| Predictor | HR (95%CI) a | HR (95%CI) |

| Exposure category | ||

| MSMb | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| IDUc | 1.94 (1.84 – 2.05)*** | 1.87 (1.77 – 1.98)*** |

| Age (per year of increase) | 1.02 (1.02 – 1.03)*** | 1.02 (1.02 – 1.03)*** |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-white | 1.29 (1.20 – 1.38)*** | 1.34 (1.25 – 1.45) *** |

| Unknown | 0.56 (0.52 – 0.59)*** | 0.56 (0.52 – 0.59) *** |

| HAART uptake after AIDS diagnosis | ||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 0.50 (0.44 – 0.56)*** | 0.48 (0.42 – 0.53) *** |

| CD4 cell count at diagnosis (×106/l) | ||

| <200 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 200-350 | 0.31 (0.26 – 0.36)*** | 0.30 (0.26 – 0.35) *** |

| >350 | 0.30 (0.26 – 0.36)*** | 0.30 (0.26 – 0.35) *** |

| Unknown | 2.39 (2.13 – 2.68)*** | 2.65 (2.35 – 2.99) *** |

| HIV-1 RNA (log10 copies/ml) | ||

| <4.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 4.00-5.00 | 1.44 (1.23 – 1.67)*** | 1.47 (1.26 – 1.72) *** |

| >5.00 | 2.39 (2.05 – 2.77)** | 2.46 (2.11 – 2.87) *** |

| Unknown | 1.67 (1.46 – 1.91)*** | 1.71 (1.49 – 1.96) *** |

| Estimated frailty variance | 0.57*** | 0.50*** |

Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval);

Men who have sex with men;

Injection Drug Users;

Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy;

Antiretroviral Therapy;

p-value=0.0000

The estimated frailty variance was significantly different from zero on both analyses, suggesting that the risk of death after AIDS diagnosis was heterogeneous among subjects living in different states and municipalities (Table 4). Greater frailty effects were found in larger states located in the Tropical Rain Forest region and in states located in the Northeast, Brazil's poorest region. On the other hand, industrialized areas from the Southern and Southeastern regions accounted for the smallest frailty effect.

Discussion

This is the first study in Brazil to conduct survival analyses with a large and representative population of PLWHA using data from all Brazilian AIDS surveillance databanks. MSM were selected as the comparison group because several studies have demonstrated the increased survival and better access to health care among MSM, particularly when compared to IDU, a highly marginalized population.37-39 Previous survival analyses conducted with Brazilian AIDS National Data found a substantial increase in survival time over the years, particularly among patients diagnosed after 1996, when free and universal access was instituted in Brazil.40 The present study extended these earlier findings by analyzing for the first time data from all patients with a confirmed AIDS diagnosis after HAART became widely available in the country, with specific analyses for different exposure categories (IDU and MSM).

This study uncovered a significant increase in survival after AIDS diagnosis among patients belonging to both MSM and IDU exposure categories: the overall median survival was 2.45 years for those patients diagnosed in the late post-HAART era (after 2000). In a previous study conducted with national data, the median survival times following AIDS diagnosis were 5 months for cases diagnosed in the 1980s and 18 months for those diagnosed in 1995.40 The increased survival we observed underscores the dramatic benefit of providing universal access to HAART to both MSM and IDU that has been reported by others,41,42 and emphasizes the need for treatment roll-out in developing countries.

However, our analysis also showed that deep inequalities remain, even in the context of free and universal access to HAART in Brazil. IDU living with AIDS were less likely to receive HAART, had lower CD4 counts and higher HIV-1 viral loads when presenting to health care facilities, and subsequently had higher mortality rates compared to MSM. Even for patients diagnosed after 2000, when HAART and correspondent monitoring were available even in Brazil's most remote corners, IDU still had a higher mortality rate: almost one and a half times higher than MSM, after adjusting for confounders. Even after restricting our analysis to patients who had received at least one CD4 count and one HIV-1 RNA viral load determination, IDU remained with higher mortality rates. Our findings suggest that substantial reductions in time to AIDS and death during the HAART era do not apply equally to IDU, when compared to MSM, and that unequal access to care is unlikely to fully explain the disparities in mortality rates.

The disparities we observed may be attributed to key problems already identified among this population: lower overall uptake of HAART;13 late presentation into care, lack of key laboratory and monitoring for a large proportion of IDU and initiation of HAART at more advanced stages of disease.20 The higher mortality rate we observed among IDU has already been described in a smaller Brazilian study by Cardoso and colleagues43 and in high-income countries with universal access to HAART.37, 44 Our study extends findings by Cardoso and colleagues,43 by evaluating all IDU receiving HIV treatment and care through public health facilities in the country, rather than a convenience sample of HIV-positive IDU.

In the present study, having received HAART was also associated with a clear survival advantage after AIDS diagnosis. However, we cannot rule out selection bias due to differential indication of treatment, as those patients who are prescribed HAART might be those with a greater a priori probability of survival. Additional modeling analyses are needed to separate these entangled effects.

This study is highly representative in terms of its broad geographic scope; however, its external validity might be limited by the fact that an unmeasurable fraction of people living with AIDS may not access the network of accredited health units due to costs associated with traveling or other marginal costs (e.g. losses secondary to unexpected work leaves or the need to care of young children).

Another limitation of our study is the unavailability of information on other covariates that may influence health and survival and which may vary over time, such as active drug use and engagement in drug addiction treatment. We were unable to examine other structural factors, such as access to private health insurance (around 30% of PLWHA in Brazil) quality of care, or health-related behavior (e.g. HAART adherence) that may account for these disparities on an individual and/or at population level. Differences outcomes might result from biases and/or confounders not accounted for in our model.

Around 40-50% of our sample had never had a CD4 count and/or an HIV viral load determination performed through the public health system. Although a proportion of these patients might be obtaining their exams through private laboratories, the Kaplan-Meier curves for those with unknown initial CD4 or HIV viral load were significantly lower that for those with available results, which reinforces the notion that an important percentage of those patients with unknown information might not receiving any care.

Perhaps the greatest limitation of our analysis is the lack of information on treatment course and clinical events, such as the type of initial ART regimen and changes in therapeutic regimens over time. Recent studies have found that better immunological, virological and clinical outcomes are associated with non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase-inhibitor regimens instead of unboosted protease inhibitor regimens, or regimens containing boosted protease inhibitors.45-47 Information on treatment interruptions due to the development of medication side-effects,48 or the development of a concurrent illness was also not available.

Our analysis attempted to account for the heterogeneity between and within different Brazilian regions and localities. As expected, this analysis suggests higher mortality risks for patients living in larger semi-urban and rural areas and/or in the poorest regions of Brazil In those regions, AIDS mortality might be influenced by structural factors related to the place of residence, beyond individual level factors (e.g. less availability of specialized services, great distances from residence to AIDS services). This analysis suggests the need to include the assessment of structural variables and/or to conduct multilevel analyses in future studies. Even after these adjustments, the analyses followed the same general trend of a significantly increased risk of death among IDU, when compared to MSM.

Among the patients who access Brazil's network of over 600 ARV dispensing units, the use of HAART for HIV-positive drug users remains a complex public health problem. Issues of delayed AIDS diagnose, late entry into treatment, and lower HAART uptake need to be simultaneously addressed. Since it has been established that IDUs can attain similar adherence levels to HAART compared to other populations,21,22 efforts are needed to improve early engagement of IDU in comprehensive HIV/AIDS treatment and care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Brazilian National STD/AIDS Program for authorizing our access to their Nation-wide datasets.

Sources of Support: Dr. Strathdee acknowledges support from the Fogarty International Center, grant R25-TW007500.

Dr. Malta acknowledges support from the CICAD/NIDA Competitive Research Award Fund, and the University of California Center for AIDS Research (NIAID 5 P30 AI 036214).

Footnotes

Part of this data was presented at the: XVII International AIDS Conference (Mexico City, 3-8 August, 2008)

References

- 1.Egger M, May M, Chene G, Phillips AN, Ledergerber B, Dabis F, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Li C, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:921–929. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montaner JS, Hogg R, Wood E, Kerr T, Tyndall M, Levy AR, et al. The case for expanding access to highly active antiretroviral therapy to curb the growth of the HIV epidemic. Lancet. 2006;368:531–536. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine RS, Briggs NC, Kilbourne BS, King WD, Fry-Johnson Y, Baltrus PT, et al. Black-White mortality from HIV in the United States before and after introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy in 1996. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1884–1892. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper S, Lynch J. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and socioeconomic inequalities in AIDS mortality in Spain. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17:231. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dray-Spira R, Gueguen A, Ravaud JF, Lert F. Socioeconomic differences in the impact of HIV infection on workforce participation in France in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:552–558. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braga P, Cardoso MR, Segurado AC. Gender differences in survival in an HIV/AIDS cohort from Sao Paulo, Brazil. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:321–328. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hacker MA, Petersen ML, Enriquez M, Bastos FI. Highly active antiretroviral therapy in Brazil: the challenge of universal access in a context of social inequality. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2004;16:78–83. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892004000800002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiguba R, Byakika-Tusiime J, Karamagi C, Ssali F, Mugyenyi P, Katabira E. Discontinuation and modification of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected Ugandans: prevalence and associated factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:218–223. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31805d8ae3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, Harrigan PR, O'Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JSG. Effect of medication adherence on survival of HIV infected adults who start highly active antiretroviral therapy when the CD4_ cell count is 0.200 to 0.350 _ 109 cell/L. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:810–816. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, Harrigan PR, O'Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS. Is there a baseline CD4 cell count that precludes a survival response to modern antiretroviral therapy? AIDS. 2003;17:711–720. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303280-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fein O. The influence of social class on health status. Americanand British research on health inequalities. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:577–586. doi: 10.1007/BF02640369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aceijas C, Oppenheimer E, Stimson GV, Ashcroft RE, Matic S, Hickman M. Antiretroviral treatment for injecting DU in developing and transitional countries 1 year before the end of the “Treating 3 million by 2005. Making it happen. The WHO strategy” (″3 by 5″) Addiction. 2006;101:1246–1253. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palepu A, Tyndall M, Yip B, O'Shaughnessy MV, Hogg RS, Montaner JS. Impaired virologic response to highly active antiretroviral therapy associated with ongoing injection drug use. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:522–526. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celentano DD, Galai N, Sethi AK, Shah NG, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D, et al. Time to initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected injection DU. AIDS. 2001;15:1707–1715. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109070-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poundstone KE, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Differences in HIV disease progression by injection drug use and by sex in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2001;15:1115–1123. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang C, Vlahov D, Galai N, Bareta J, Strathdee SA, Nelson KE, et al. Mortality in HIV-seropositive versus seronegative persons in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: implications for when to initiate therapy. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1046–1054. doi: 10.1086/422848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassetti S, Battegay M, Furrer H, Rickenbach M, Flepp M, Kaiser L, et al. Why is highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) not prescribed or discontinued? Swiss HIV cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;21:114–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mocroft A, Madge S, Johnson AM, Lazzarin A, Clumeck N, Goebel FD, et al. A comparison of exposure groups in the EuroSIDA study: starting highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), response to HAART, and survival. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;22:369–378. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199912010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vlahov D, Celentano DD. Access to highly active antiretroviral therapy for injection DU: adherence, resistance, and death. Cad Saude Publica. 2006;22:705–718. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2006000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malta M, Strathdee SA, Magnanini MM, Bastos FI. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome among drug users: a systematic review. Addiction. 2008;103:1242–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malta M, Magnanini MM, Strathdee SA, Bastos FI. Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Among HIV-Infected Drug Users: A Meta-Analysis. AIDS Behav. 2008 Nov 20; doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9489-7. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bastos FI, Kerrigan D, Malta M, Carneiro-da-Cunha C, Strathdee SA. Treatment for HIV/AIDS in Brazil: strengths, challenges, and opportunities for operations research. [Nov 12, 2008];AIDS Science. 2001 November;1(15) serial online. Available at: http://aidscience.org/Articles/aidscience012.asp.

- 24.Simao M. Drug pricing policies and challenges: Lessons from Brazil [THSY0102]. Presented at: XVII International AIDS Conference; 2008; Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nunn AS, Fonseca EM, Bastos FI, Gruskin S, Salomon JA. Evolution of antiretroviral drug costs in Brazil in the context of free and universal access to AIDS treatment. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melo AC, Caiaffa WT, Cesar CC, Dantas RV, Couttolenc BF. Utilization of HIV/AIDS treatment services: comparing injecting drug users and other clients. Cad Saude Publica. 2006;22:803–813. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2006000400019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camargo KR, Jr, Coeli CM. Reclink: an application for database linkage implementing the probabilistic record linkage method. Cad Saude Publica. 2000;16:439–447. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2000000200014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook LJ, Olson LM, Dean JM. Probabilistic record linkage: relationships between file sizes, identifiers and match weights. Methods Inf Med. 2001;40:196–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grannis SJ, Overhage JM, Hui S, McDonald CJ. Analysis of a probabilistic record linkage technique without human review. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003;2003:259–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schoenfeld D. Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika. 1982;69:239–241. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clayton DG. A model for association in bivariate life tables and its application in epidemiological studies of familial tendency in chronic disease incidence. Biometrika. 1978;65:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hougaard P. Analysis of multivariate survival data. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aalen OO. Effects of frailty in survival analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 1994;3:227–243. doi: 10.1177/096228029400300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carvalho MS, Andreozzi VL, Codeço CT, Barbosa MTS, Shimakura SE. Portuguese. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fiocruz; 2005. [Survival Analysis: Theory and Health Applications] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naskar M, Das K, Ibrahim JG. A semiparametric mixture model for analyzing clustered competing risks data. Biometrics. 2005;61:729–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.R Core Development Team. computer software Version 2.8.0. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodríguez-Arenas MA, Jarrín I, del Amo J, Iribarren JA, Moreno S, Viciana P, et al. Delay in the initiation of HAART, poorer virological response, and higher mortality among HIV-infected injecting drug users in Spain. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:715–723. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blades R, Li K, Kerr T, Tyndall MW, Montaner JS, Wood E. Contribution of HIV to mortality among injection drug users in the era of HAART. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:655–656. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181568d8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirk GD, Vlahov D. Improving survival among HIV-infected injection drug users: how should we define success? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:377–380. doi: 10.1086/519426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marins JR, Jamal LF, Chen SY, Barros MB, Hudes ES, Barbosa AA, et al. Dramatic improvement in survival among adult Brazilian AIDS patients. AIDS. 2003;17:1675–1682. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200307250-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smit C, Geskus R, Walker S, Sabin C, Coutinho R, Porter K, et al. Effective therapy has altered the spectrum of cause-specific mortality following HIV seroconversion. AIDS. 2006;20:741–749. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216375.99560.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pérez-Hoyos S, del Amo J, Muga R, del Romero J, García de Olalla P, Guerrero R, et al. Effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy in Spanish cohorts of HIV seroconverters: differences by transmission category. AIDS. 2003;17:353–359. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200302140-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cardoso MN, Caiaffa WT, Mingoti SA. Projeto AjUDE-Brasil II. AIDS incidence and mortality in injecting drug users: the AjUDE-Brasil II. Project. Cad Saude Publica. 2006;22:827–837. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2006000400021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood E, Kerr T, Hogg RS, Palepu A, Zhang R, Strathdee SA, et al. Impact of HIV testing on uptake of HIV therapy among antiretroviral naïve HIV-infected injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25:451–454. doi: 10.1080/09595230600883313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gupta R, Hill A, Sawyer AW, Pillay D. Emergence of drug resistance in HIV type 1-infected patients after receipt of first-line highly active antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review of clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:712–722. doi: 10.1086/590943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lima VD, Gill VS, Yip B, Hogg RS, Montaner JS, Harrigan PR. Increased resilience to the development of drug resistance with modern boosted protease inhibitor-based highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:51–58. doi: 10.1086/588675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:939–941. doi: 10.1086/507526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pádua CA, César CC, Bonolo PF, Acurcio FA, Guimarães MD. High incidence of adverse reactions to initial antiretroviral therapy in Brazil. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39:495–505. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2006000400010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]