Summary

Heparin, the focus of this review, is a critically important anticoagulant drug produced from animal sources, which was contaminated last year leading to a number of adverse side effects, some resulting in death. Heparin is a highly acidic polysaccharide and a member of a family of biopolymers called glycosaminoglycans. The structure and activities of heparin are detailed along with recent advances in heparin structural analysis and biological evaluation. Current state-of-the-art chemical and chemoenzymatic synthesis of heparin and new approaches for its metabolic engineering are described. New technologies, including microarrays and digital microfluidics, are proposed for high-throughput synthesis and screening of heparin and for the fabrication of an artificial Golgi.

GAG structure-activity overview

Heparin and heparan sulfate (HS) are the focus of the current review (Figure 1). Heparin is a member of a family of polyanionic, polydisperse, linear polysaccharides called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), which perform a variety of critical biological functions and have been extensively employed as therapeutic agents [1]. GAGs range from relatively simple structures, such as hyaluronan, comprised of a repeating N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc)-glucuronic acid (GlcA) disaccharide, to the extremely complex heparin/HS-GAGs made of repeating uronic acid-glucosamine disaccharides with as many as 32 different disaccharide building blocks comprising > 1014 possible sequences for an icosasaccharide chain. Heparin and HS GAGs are structurally related and synthesized in the Golgi by the same biosynthetic enzymes. While they are comprised of identical back-bone disaccharides, heparin and HS show very different compositions with heparin containing a much higher density of N- and O-sulfo groups [2]. Heparin/HS GAGs are covalently attached, through a tetrasaccharide linker, to selected serine residues of a core protein and this glycoconjugate is called a proteoglycan (PG). HS-PGs consist of one or more HS-GAG chains attached to a variety of cores, including integral transmembrane and glycosylphosphatidyl inositol-anchored proteins, and are generally localized to the outer cell membrane or the extracellular matrix (ECM) of virtually all animal cells, where they are involved in cell-cell interaction and signaling [3]. In contrast, the heparin-PG is comprised only of the serglycin core and is localized intracellularly in the granules of a selected group of cells, in particular mast cells [1]. Heparin is released as a GAG on mast cell degranulation along with histamine in an allergic response. In summary, while biosynthesized in a common pathway, heparin and HS are structurally distinctive, differentially localized, and functionally unique.

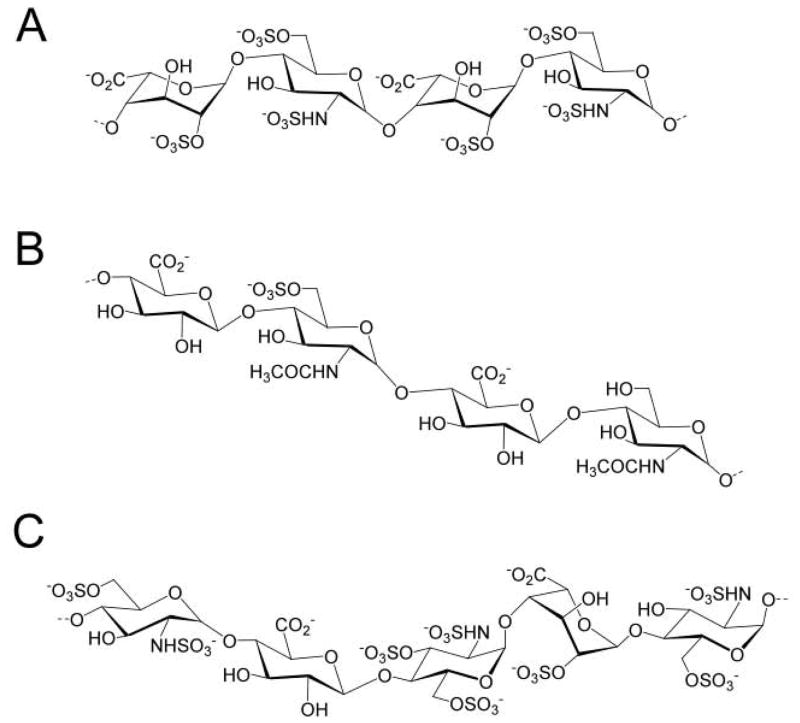

Figure 1.

Heparin and HS. A. The prominent trisulfated disaccharide-repeating unit in heparin represents 80–90% of its structure. B. HS has a more variable structure and primarily consists of monosulfated and unsulfated disaccharide units. It has a domain structure in which the more highly sulfated repeating units are clustered. C. An AT-binding pentasaccharide site is shown. There is some variability both within this AT-binding site and in surrounding residues, but all contain the critical 3-O-sulfo group in the central saccharide residue. Both heparin and HS can contain this site or one of its structural variants.

Heparin/HS interact with a wide array of proteins, called heparin-binding proteins (Table 1), modulating their biological activities [4]. The most studied of these interactions is between a pentasaccharide sequence (Figure 1) in heparin and HS and the serine protease inhibitor antithrombin (AT). This specific interaction leads to a conformational change in AT resulting in its potent inhibition of thrombin and other serine proteases and heparin’s anticoagulant activity [1]. Heparin, prepared from pig intestine, is currently in widespread use as an anticoagulant drug with over 100 metric tons used annually. In 2008, a contamination of the heparin supply caused a number of deaths in the US, leading to the introduction of sophisticated analytical controls to secure the quality and safety of this critical pharmaceutical agent [5]. Recent studies have established specificity of HS interactions with chemokines (such as interleukins) and growth factors and their receptors (such as fibroblast growth factor and its receptors) [6,7]. These interactions are critical in cell migration in inflammation, metastasis, and cell growth and differentiation in development and wound healing [6,8]. There is currently an ongoing debate on how specific these interactions are and whether a single saccharide sequence within heparin and HS or a collection of sequences give the appropriate spatial array of sulfo groups responsible for protein binding and functional activity [9]. In any case it is clear that the linear sequence of heparin/HS determines its three-dimensional structure and thus is ultimately responsible for biological activity.

Table 1.

Selected examples of heparin-binding proteins and their biological activity

| Class | Examples | Physiological/Pathophysiological Effect of Binding |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | Coagulation proteases, complement esterases, extracellular superoxide dismutase, topoisomerase | Multiple |

| Enzyme inhibitors | AT, heparin cofactor II, secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor, C1INH | Coagulation, inflammation, complement regulation |

| Cell adhesion proteins | P-selectin, L-selectin | Cell adhesion, inflammation, metastasis |

| Extracellular matrix proteins | Laminin, fibronectin, collagens, thrombospondin, vitronectin, tenascin | Cell adhesion, matrix organization |

| Chemokines | Platelet factor 4, interleukins | Chemotaxis, signaling, inflammation |

| Growth factors | Fibroblast growth factors, hepatocyte growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor | Mitogenesis, cell migration |

| Morphogens | Hedgehogs, transforming growth factor-β | Cell specification, tissue differentiation, development |

| Tyrosine-kinase growth factor receptors | Fibroblast growth factor receptors, vascular endothelium growth factor receptor | Mitogenesis |

| Lipid-binding proteins | Apolipoprotein E, lipoprotein lipase, hepatic lipase, annexins | Lipid metabolism cell membrane functions |

| Plaque proteins | Prion proteins, amyloid protein | Plaque formation |

| Pathogen and viral surface proteins | Malaria cirumsporozoite protein, herpes simplex virus, dengue virus, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus | Pathogen infections |

GAG structural analysis

Physicochemical properties and low abundance of naturally occurring GAGs (Table 2), and the lack of amplification mechanism due to their non-template-dependent biosynthesis direct the developments in GAG structural analysis. Currently, nanogram amounts of intact GAGs can be assessed in terms of their concentration, polydispersity, charge density, and molecular weight by capillary electrophoresis [10]. Saccharide composition of milligram amounts of intact GAGs can be determined using multidimensional nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [11–13]. Multidimensional NMR has been employed in elucidating the composition and solution conformation of heparin and chemoenzymatically synthesized [13C, 15N]-heparin, two critical parameters in understanding heparin’s structure-activity relationship (SAR) [12].

Table 2.

Examples of natural abundance of HS

| Tissue | Amount | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| human liver | 80 μg/g wet tissue | Vonchan et al., Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2005, 1721: 1–8 |

| mosquito | 11 ng/mosquito | Sinnis et al., J. Biol. Chem., 2007, 282: 25376–25384 |

| murine embryonic stem cell | 12–94 ng/106 cells | Nairn et al., J. Proteome Res., 2007, 6: 4374–4387 |

| murine liver | 30 μg/g wet tissue | Warda et al., Glycoconj. J., 2006, 23: 555–563 |

| zebrafish (HS and CS) | 30 μg/adult fish | Zhang et al., Glycoconj. J., 2009, 26: 211–218 |

High-resolution Fourier-transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometric (MS) analysis of intact GAG component of bikunin PG has been reported [14]; however, the MS structural analysis of intact single chain in a mixture remains a challenge. In most studies, GAGs are depolymerized to oligosaccharides prior to analysis under controlled enzymatic or chemical conditions. MS coupled with on-line or off-line separation is the method of choice for structural characterization of GAG oligosaccharides [15] providing femtomole sensitivity in the analysis of underivatized oligosaccharides [10,15]. Multiple-stage MS oligosaccharide analysis is useful in determining the saccharide modification pattern and C5 uronic acid epimerization [16] and can differentiate structural isomers of the same molecular mass. [17] Novel ion-activation methods effecting information-rich saccharide fragmentation have recently been applied in the structural analysis of GAG oligosaccharides [16,18,19] and hold great potential in microsequencing GAGs.

GAG biological evaluation

Interactions between heparin/HS GAGs and numerous heparin-binding proteins mediate such diverse biological processes as blood coagulation, cell growth and differentiation, host defense and viral infection, lipid transport and clearance/metabolism, cell-cell and cell-matrix signaling, inflammation, and cancer [4,20–23]. Thus, an understanding of GAG-protein interactions at the molecular level is of fundamental importance to biology and to the design of highly specific therapeutic agents [4,24]. Parameters that provide both qualitative and quantitative information about heparin/HS-protein interactions include binding affinity and kinetics (KD, on-rate, off-rate), thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS), binding stoichiometry, and structural specificity characterized using affinity chromatography, isothermal titration calorimetry, NMR, fluorescence spectroscopy, surface plasmon resonance, affinity coelectrophoresis, equilibrium dialysis, competitive binding techniques, analytical centrifugation, circular dichroism, and x-ray crystallography [25]. These studies suggest several guiding principles behind protein-GAG interactions including: shallow binding sites on the surface of the protein, ionic and hydrogen bonding interactions between arginine and lysine residues of the protein and sulfo and carboxyl groups of the GAG, fast binding, multivalent binding, and some but not all binding events being accompanied by conformational changes in protein and GAG.

The knowledge of physicochemical parameters of protein-GAG interactions alone is insufficient for determining GAG biological activity, and biological evaluation is required to develop effective GAG-based drugs. In the case of anticoagulant activity, for example, while binding to AT is important, in vitro blood coagulation assays and in vivo pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles, assessed using animal models, are required before clinical evaluation of a new agent is possible [26].

GAG synthesis

Biosynthesis of GAGs

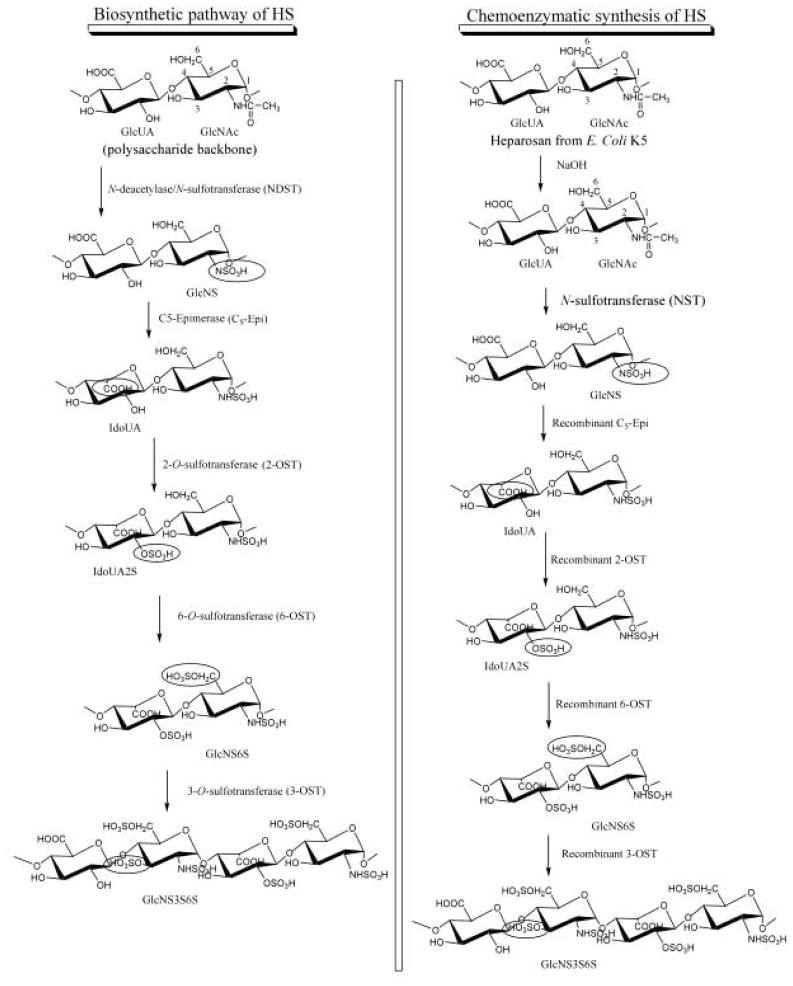

The biosynthesis of HS involves a series of specialized enzymes, including glycosyl transferases, an epimerase, and sulfotransferases, essentially all of which have been cloned [27]. Both the enzymes involved in the synthesis of linkage region tetrasaccharide and polysaccharide backbone and the modifying enzymes impart high functional selectivity to the HS. The modification reactions are carried out on the unsulfated polysaccharide backbone consisting of GlcA-GlcNAc repeat (Figure 2). The glucosaminyl N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase (NDST) converts a GlcNAc unit to N-sulfoglucosamine (GlcNS). After the N-sulfonation, C5-epimerase converts some GlcA units to iduronic acid (IdoA). The polysaccharide is then modified by the 2-O-sulfotransferase (2-OST), 6-O-sulfotransferase (6-OST), and 3-O-sulfotransferase (3-OST), incorporating sulfo groups at the 2-position of IdoA and GlcA and the 6- and 3-positions of the glucosamine (GlcN), respectively. Although the modifications do not necessarily follow the sequence shown in Figure 2, NDST action on GlcNAc dictates the levels of O-sulfonation and epimerization. The modifications in vivo are typically incomplete, resulting in structurally heterogeneous polysaccharide products.

Figure 2.

Biosynthetic pathway and chemoenzymatic synthesis of HS. The polysaccharide backbone synthesis is omitted for clarity. The recombinant biosynthetic HS modifying enzymes are obtained from bacterial expression. To improve cost-efficiency, a low-cost sulfo donor, p-nitrophenol sulfate is coupled with the 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate regeneration system for use with HS sulfotransferases

Chemical synthesis of GAGs

Despite major advances in carbohydrate chemistry, the chemical synthesis of heparin is still not possible. Twenty five years ago a major effort resulted in the multistep chemical synthesis of the heparin AT-binding site pentasaccharide [28]. This synthesis was critical in confirming the structure of the AT-binding pentasaccharide and in understanding its SAR. Improvements in this synthesis led to the successful introduction of the synthetic pentasaccharide drug, Arixtra, a specific anti-factor Xa inhibitor [29]. This drug is expensive and has failed to capture more than a very small portion of the heparin market. Because of the difficulties inherent to the chemical synthesis of carbohydrates, it is unlikely that heparin having an average of 40 saccharide units will ever be successfully synthesized.

Chemoenzymatic synthesis of GAGs

A promising alternative to chemical synthesis of HS/heparin is the enzyme-based approach, which takes advantage of extremely high regioselectivity of HS biosynthetic enzymes. This approach is particularly effective in synthesizing sulfated polysaccharides and large oligosaccharides, where chemical synthesis often fails [30]. The chemoenzymatic synthesis mimics the biosynthetic pathway of HS (Figure 2) affording a variety of HS structures with desired biological activities, for example structures comparable to the heparin from natural sources [12,31,32]. By selecting the appropriate combination of biosynthetic enzymes, a library of sulfated polysaccharides has been prepared and employed in the identification of a novel heparin structure with anticoagulant activity [33]. The structural diversity of the chemoenzymatically synthesized HS can be expanded using enzyme engineering. Structurally-guided site-directed mutagenesis has been used successfully to alter the substrate specificities of 3-OST and 2-OST, thereby resulting in polysaccharide products that are not biosynthesized by wild-type enzymes [34,35].

GAG synthesis through metabolic engineering of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells

Health safety issues associated with the use of porcine heparin encouraged work on heparin production through metabolic engineering. CHO cells are capable of biosynthesizing HS but not heparin; however, CHO mutants defective in HS biosynthesis demonstrate the similarity of CHO cell HS biosynthesis and heparin biosynthesis in connective tissue type mast cells [36,37]. The selective expression of the NDST isoforms apparently determines whether HS or heparin is synthesized [38]. Indeed, > 80% of the GlcN residues in mast cell heparin are GlcNS, while > 50% of the GlcN residues in CHO cell HS are GlcNAc [39]. Wild-type CHO cells express two out of the four NDSTs, one out of the three 6-OSTs, and none of the seven 3-OSTs found in human, which explains structural simplicity of HS produced by these cells [37]. Thus, the CHO-cell HS lacks some of the biological activities observed in HS produced by other cell types. Biosynthesis of heparin-like HS in CHO cells would require: 1. Over-expression of an appropriate core protein for carrying the CHO heparin outside the cell and releasing it into the culture supernatant; 2. Controlled expression of the NDST isoforms; 3. Co-localization of sufficient amounts of C5 epimerase and 2-OST; 4. Maintaining sufficient levels and the correct Golgi localization of the appropriate 6-OST isoforms; and 5. Expression and the correct Golgi localization of 3-OST isoforms. While challenging, such steps do not require inventing new methodologies, thus the potential for metabolically engineered cell culture for HS synthesis is high, particularly for the generation of HS analogs.

High-throughput synthesis and screening of bioactive GAGs

Microfluidics and lab-on-a-chip technologies have received considerable attention for their reduced reagent consumption and analysis time, increased reaction control and throughput, and amenability to full automation associated with the microscale reaction format [25,40,41]. Both microarray- and microfluidic-based platforms allow rapid synthesis seamlessly coupled with bioactivity screening. This flexibility is ideally suited for the rapidly expanding field of glycomics, a study of expression, SAR, and biological mechanisms of glycans, as well as for designing unnatural glycans that may serve as new therapeutics [42]. Glycomics-on-a-chip approaches have been advanced, primarily involving high-throughput microarray-based screening of glycan-protein interactions [43,44]. For example, a heparin glycan chip with a 4800-fold enhanced signal-to-noise ratio, as compared to the control without heparin, has been developed for high-throughput analysis of heparin-AT interactions for potential therapeutic applications [45]. Enhanced interactions of complex glycans with cells may be facilitated by advances in the design of three-dimensional human cell culture microarrays [46], enabling a combination of cell-based and biomolecular assays to be performed in very high throughput.

Microfluidic systems lack the immediate high-throughput character of microarrays; however, they may provide environments that more accurately mimic biological synthesis and can be manipulated leading to new biosynthetic and biological screening designs. Currently, two types of microfluidic systems have been developed: 1. Channel microfluidics, consisting of fluid flow in patterned channels; and 2. Digital microfluidics, consisting of open droplet movement on a two-dimensional grid-like platform, which eliminates many of the constraints associated with fixed channels. Since digital microfluidics manipulates samples and reagents in the form of discrete droplets and due to the geometry of the array, it is more easily reconfigured than a channel device, allowing for a greater number of paths through the system and droplet size tailored from nanoliter to microliter volumes [41]. This permits a variety of functions without the need to redesign the device expanding the range of applications from assays to sample preparation [40,47].

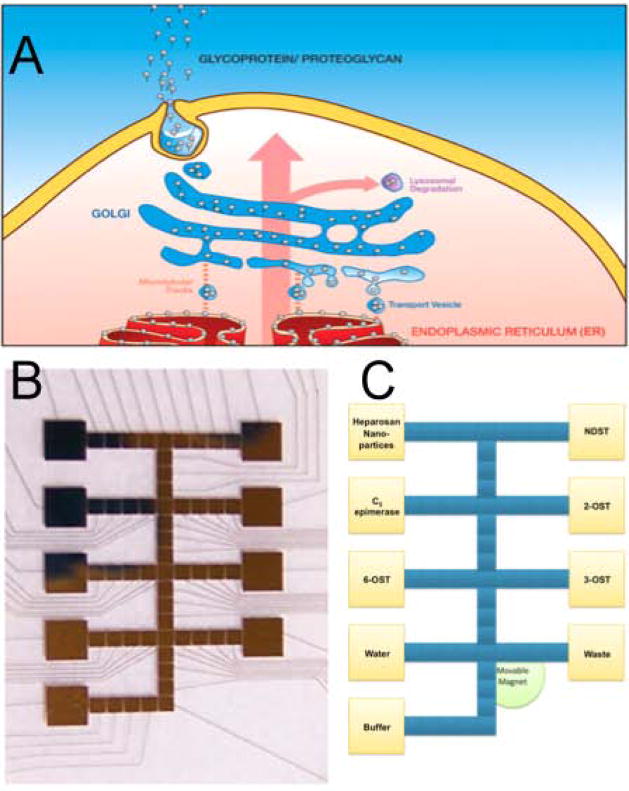

Microfluidic GAG synthesis – development of an artificial Golgi organelle

The Golgi is the organelle responsible for the posttranslational protein glycosylation, a multistep non-template-dependent process resulting in the synthesis of glycoproteins and PGs. The structural microheterogeneity of HS originates in the complex organization of the Golgi that, in a simplified view, acts as a network of nanofluidic channels and membranes containing a number of enzymes. GAG synthesis through the Golgi is the result of precise control of the fluid flow and biocatalytic transformations (Figure 3). As the first step toward the construction of the artificial Golgi, HS has been successfully modified by 3-OST on a digital microfluidic platform[48]. Biotinylated HS, immobilized on streptavidin-coated magnetic nanoparticles, has been brought in contact with 3-OST-1 in a digital microfluidic device (Figure 3). Analysis of the 3-OST-modified HS showed 70-fold greater amount of 3-O-sulfation compared with the unmodified control. This approach may aid in the design of biosynthetic heparin, rendering current unsafe methods of heparin production from animal tissue obsolete [49].

Figure 3.

The Golgi and artificial Golgi. A. Cartoon of the Golgi: The direction of flow (pink arrow) in posttranslational modification is from the endoplasmic reticulum (red) to the cell membrane (yellow), where PGs and glycoproteins are released into the extracellular environment. B. The design of an artificial Golgi for the HS biosynthesis: Yellow squares are the reagent and enzyme reservoir electrodes, blue squares – electrodes for droplet movement, mixing, and sequestration. C. A fabricated artificial Golgi based on the design in panel B: Thin gold wires lead from square reservoir electrodes to pads connecting them to a power source.

Conclusions

The remarkable therapeutic and biological importance of heparin/HS ensures a continued interest in advancing new technologies for their synthesis and to understand their SAR. The future should bring an improved understanding of Golgi-based heparin/HS biosynthesis, its control and scale-up, and the rapid, microscale analysis of heparin/HS leading to the production of bioengineered anticoagulant heparin and a novel array of designer heparin-based therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (HL62244, HL096972, GM38060, GM090127, RR023764 to RJL and HL094463 to JL) for supporting this work and thank JG Martin for preparing Figure 3.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Linhardt RJ, Claude S. Hudson Award Address in Carbohydrate Chemistry. Heparin: Structure and Activity. J Med Chem. 2003;46:2551–2564. doi: 10.1021/jm030176m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stringer SE, Gallagher JT. Heparan sulphate. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:709–714. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop JR, Schuksz M, Esko JD. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans fine-tune mammalian physiology. Nature. 2007;446:1030–1037. doi: 10.1038/nature05817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capila I, Linhardt RJ. Heparin-protein interactions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:391–412. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020201)41:3<390::aid-anie390>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5**.Liu H, Zhang Z, Linhardt RJ. Lessons learned from the contamination of heparin. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:313–321. doi: 10.1039/b819896a. This review gives a detailed account of the heparin contamination crisis of 2008 and proposes both short-term and long-term solutions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen SK, Li JY, Bromleigh C, Eliseenkova AV, Ibrahimi OA, Lao Z, Zhang F, Linhardt RJ, Joyner AL, Mohammadi M. Structural basis by which alternative splicing modulates the organizer activity of FGF8 in the brain. Genes Dev. 2006;20:185–198. doi: 10.1101/gad.1365406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson FC, Elgin ES, Nelson TJ, Zhang F, Hoeger TJ, Linhardt RJ, Volkman BF. Identification and characterization of a glycosaminoglycan recognition element of the C chemokine lymphotactin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12598–12604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexopoulou AN, Multhaupt HA, Couchman JR. Syndecans in wound healing, inflammation and vascular biology. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:505–528. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kreuger J, Spillmann D, Li J-P, Lindahl U. Interactions between heparan sulfate and proteins: the concept of specificity. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:323–327. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volpi N, Maccari F, Linhardt RJ. Capillary electrophoresis of complex natural polysaccharides. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:3095–3106. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrini M, Guglieri S, Naggi A, Sasisekharan R, Torri G. Low molecular weight heparins: structural differentiation by bidimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2007;33:478–487. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-982078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Z, McCallum SA, Xie J, Nieto L, Corzana F, Jimenez-Barbero J, Chen M, Liu J, Linhardt RJ. Solution structures of chemoenzymatically synthesized heparin and its precursors. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12998–13007. doi: 10.1021/ja8026345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guerrini M, Naggi A, Guglieri S, Santarsiero R, Torri G. Complex glycosaminoglycans: profiling substitution patterns by two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Anal Biochem. 2005;337:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chi L, Wolff JJ, Laremore TN, Restaino OF, Xie J, Schiraldi C, Toida T, Amster IJ, Linhardt RJ. Structural analysis of bikunin glycosaminoglycan. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2617–2625. doi: 10.1021/ja0778500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15**.Zaia J. On-line separations combined with MS for analysis of glycosaminoglycans. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2009;28:254–272. doi: 10.1002/mas.20200. A comprehensive review of current liquid chromatographic-mass spectrometric methods of GAG characterization. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16*.Wolff JJ, Chi L, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. Distinguishing glucuronic from iduronic acid in glycosaminoglycan tetrasaccharides by using electron detachment dissociation. Anal Chem. 2007;79:2015–2022. doi: 10.1021/ac061636x. This is the first report on distinguishing the two C5 epimers of uronic acid by mass spectrometry. The ability to distinguish between IdoA and GlcA is critical in characterizing biologically active GAG domains. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meissen JK, Sweeney MD, Girardi M, Lawrence R, Esko JD, Leary JA. Differentiation of 3-O-sulfated heparin disaccharide isomers: identification of structural aspects of the heparin CCL2 binding motif. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:652–657. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolff JJ, Amster IJ, Chi L, Linhardt RJ. Electron detachment dissociation of glycosaminoglycan tetrasaccharides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolff JJ, Laremore TN, Aslam H, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. Electron-induced dissociation of glycosaminoglycan tetrasaccharides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:1449–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hacker U, Nybakken K, Perrimon N. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans: the sweet side of development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:530–541. doi: 10.1038/nrm1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parish CR. The role of heparan sulphate in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:633–643. doi: 10.1038/nri1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22*.Powell AK, Yates EA, Fernig DG, Turnbull JE. Interactions of heparin/heparan sulfate with proteins: appraisal of structural factors and experimental approaches. Glycobiology. 2004;14:17R–30R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh051. An expert review of methods to measure GAG-protein interactions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sasisekharan R, Raman R, Prabhakar V. Glycomics approach to structure-function relationships of glycosaminoglycans. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2006;8:181–231. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24*.Gandhi NS, Mancera RL. The structure of glycosaminoglycans and their interactions with proteins. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2008;72:455–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00741.x. A survey of over 200 publications describing structure-activity relationship of GAGs, types of their interactions with proteins, and factors affecting these interactions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.de Paz JL, Seeberger PH. Deciphering the glycosaminoglycan code with the help of microarrays. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:707–711. doi: 10.1039/b802217h. This review describes the applications of microarrays in GAG sequencing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mousa SA, Zhang F, Aljada A, Chaturvedi S, Takieddin M, Zhang H, Chi L, Castelli MC, Friedman K, Goldberg MM, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral heparin solid dosage form in healthy human subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47:1508–1520. doi: 10.1177/0091270007307242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27*.Peterson S, Frick A, Liu J. Design of biologically active heparan sulfate and heparin using an enzyme-based approach. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:610–627. doi: 10.1039/b803795g. This paper explains new approaches in designing and synthesizing therapeutic agents based on heparin and heparan sulfate. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinaÿ P, Jacquinet J-C, Petitou M, Duchaussoy P, Lederman I, Choay J, Torri G. Total synthesis of a heparin pentasaccharide fragment having high affinity for antithrombin III. Carbohydr Res. 1984;132:C5–C9. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petitou M, Boeckel CAAV. A Synthetic Antithrombin III Binding Pentasaccharide Is Now a Drug! What Comes Next? Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2004;43:3118–3133. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindahl U, Li JP, Kusche-Gullberg M, Salmivirta M, Alaranta S, Veromaa T, Emeis J, Roberts I, Taylor C, Oreste P, et al. Generation of “neoheparin” from E. coli K5 capsular polysaccharide. J Med Chem. 2005;48:349–352. doi: 10.1021/jm049812m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, Avci FY, Munoz EM, McDowell LM, Chen M, Pedersen LC, Zhang L, Linhardt RJ, Liu J. Enzymatic redesigning of biologically active heparan sulfate. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42817–42825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504338200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuberan B, Lech MZ, Beeler DL, Wu ZL, Rosenberg RD. Enzymatic synthesis of antithrombin III-binding heparan sulfate pentasaccharide. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1343–1346. doi: 10.1038/nbt885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33*.Chen J, Jones CL, Liu J. Using an enzymatic combinatorial approach to identify anticoagulant heparan sulfate structures. Chem Biol. 2007;14:986–993. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.07.015. The article reports preparation of eight HS polysaccharides using different combinations of biosynthetic enzymes and determination of their biological activity. This combinatorial enzymatic approach holds great potential in the synthesis of HS-based therapeutics with high functional selectivity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bethea HN, Xu D, Liu J, Pedersen LC. Redirecting the substrate specificity of heparan sulfate 2-O-sulfotransferase by structurally guided mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18724–18729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806975105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu D, Moon AF, Song D, Pedersen LC, Liu J. Engineering sulfotransferases to modify heparan sulfate. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:200–202. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bame KJ, Lidholt K, Lindahl U, Esko JD. Biosynthesis of heparan sulfate. Coordination of polymer-modification reactions in a Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant defective in N-sulfotransferase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:10287–10293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Lawrence R, Frazier BA, Esko JD. CHO glycosylation mutants: proteoglycans. Methods Enzymol. 2006;416:205–221. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)16013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugahara K, Kitagawa H. Heparin and heparan sulfate biosynthesis. IUBMB Life. 2002;54:163–175. doi: 10.1080/15216540214928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bame KJ, Esko JD. Undersulfated heparan sulfate in a Chinese hamster ovary cell mutant defective in heparan sulfate N-sulfotransferase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8059–8065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40*.Miller EM, Wheeler AR. Digital bioanalysis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;393:419–426. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2397-x. A review of the current state of digital microfluidics and its applications in bioanalysis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang H, Luk VN, Abelgawad M, Barbulovic-Nad I, Wheeler AR. A world-to-chip interface for digital microfluidics. Anal Chem. 2009;81:1061–1067. doi: 10.1021/ac802154h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42*.Liu Y, Palma AS, Feizi T. Carbohydrate microarrays: key developments in glycobiology. Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.071. A most recent review of microarray technologies in glycobiology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang PH, Wu CY, Greenberg WA, Wong CH. Glycan arrays: biological and medical applications. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song X, Xia B, Lasanajak Y, Smith DF, Cummings RD. Quantifiable fluorescent glycan microarrays. Glycoconj J. 2008;25:15–25. doi: 10.1007/s10719-007-9066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park TJ, Lee MY, Dordick JS, Linhardt RJ. Signal amplification of target protein on heparin glycan microarray. Anal Biochem. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee MY, Kumar RA, Sukumaran SM, Hogg MG, Clark DS, Dordick JS. Three-dimensional cellular microarray for high-throughput toxicology assays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:59–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708756105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller EM, Wheeler AR. A digital microfluidic approach to homogeneous enzyme assays. Anal Chem. 2008;80:1614–1619. doi: 10.1021/ac702269d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48*.Martin JG, Gupta M, Xu Y, Akella S, Liu J, Dordick JS, Linhardt RJ. Toward an Artificial Golgi: Redesigning the Biological Activities of Heparan Sulfate on a Digital Microfluidic Chip. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11041–11048. doi: 10.1021/ja903038d. The first report of a functional prototype of an artificial Golgi describes 3-O-sulfonation of an HS chain in a digital microfluidics format. The feasibility of studying multienzyme systems using this approach is discussed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guerrini M, Beccati D, Shriver Z, Naggi A, Viswanathan K, Bisio A, Capila I, Lansing JC, Guglieri S, Fraser B, et al. Oversulfated chondroitin sulfate is a contaminant in heparin associated with adverse clinical events. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:669–675. doi: 10.1038/nbt1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]