Abstract

Patient-centered cancer care has become a priority in the oncology field. Increasing efforts to train oncologists in communication skills have led to a growing literature on patient-centered cancer education. In addition, systems approaches have led to an increased emphasis on the concept of teams as an organizing framework for cancer care. In this essay, we examine issues involved in educating teams to provide patient-centered cancer care. In the process, we question the applicability of a tightly coordinated ‘team’ concept, and suggest the concept of a ‘care community’ as a more achievable ideal for the way that cancer care is commonly delivered. We discuss the implications that this has for cancer communication education, and propose three principles to guide the development of educational interventions aimed at increasing patient-centeredness in cancer care delivery systems.

Keywords: Physician-Patient Relations, Patient-Centered Care, Medical Oncology, Radiation Oncology, Oncology Service

1. Introduction

The past two decades have seen breathtaking advances in imaging, genetics, molecular biology, and a number of other disciplines related to the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cancer. While such advances have led to powerful new patient care technologies, clinicians, educators, and researchers have increasingly stressed a need to combine the new technologies with patient-centered communication. [1,2] The U.S. National Cancer Institute has established five research centers to focus specifically on communication, and the number of articles devoted to communication in cancer settings has increased exponentially over the past ten years. [3] There have also been increasing efforts to educate oncologists and other cancer care providers in the skills needed for patient-centered communication. [4–6] In parallel with such efforts have been attempts to use a team approach to organize the delivery and enhance the patient-centeredness of cancer care. [7] In this essay, we examine several issues involved in educating teams to provide patient-centered cancer care. In the process, we question the applicability of the concept of tightly coordinated ‘teams’, and suggest a ‘care community’ as an alternate ideal for how cancer care might be delivered. We discuss the implications that this has for cancer communication education, and propose several principles to guide the development of educational interventions that strive to increase patient-centeredness in cancer care systems.

2. From ‘Teams’ to ‘Communities of Care’

2.1 A Case Study of Cancer Communication

The following case is a composite based on several real patients’ stories. We do not intend it to be representative of the behaviors of all providers, but rather as an exemplar to illustrate the concepts that follow.

Tess is a 75-year-old woman with known colon cancer who presents to the hospital with hypotension and altered mental status. Tess’s cancer story began two years prior, when she was hospitalized with a bowel obstruction. At that time, the surgeons removed a large mass in the colon, and several smaller masses in her abdomen, all of which turned out to be cancerous. After surgery, the surgeon referred her to a local oncologist. Over the span of the past two years, she has been treated with varying chemotherapy regimens in response to slowly progressing cancer.

The possibility of getting cancer had created large amounts of fear for Tess for more than 30 years, stemming from the time that her aunt died of breast cancer. Her aunt’s cancer course was tumultuous, and was marked by wasting and severe bouts of nausea and sickness during chemotherapy. Tess’s worst fear was realized when she was diagnosed, and she has remained ambivalent about the doctors using ‘too much chemo’, even though her oncologist and his nurse feel that today’s powerful anti-nausea medicines can help with many of the symptoms that her aunt experienced. Tess’s main sources of information are: a) the oncologist, although her visits with him are brief; b) the oncologist’s nurse, who spends considerably more time with her and her husband Peter, answering their questions and fielding additional questions over the phone; and c) two other women who also have colon cancer and receive chemo on the same days as Tess. Over two years, her weekly chemo visits have become a ritual of sorts, and she has felt comfort in getting to know her fellow patients and exchange stories and ideas. Over the past few months, though, Tess’s situation has changed, as she has experienced large amounts of fatigue, a loss of appetite and weight, and intermittent pain. Tess has made it clear to Peter and her family that if something were to happen, she would only want the doctors to keep her alive if there were a good possibility of getting back on her feet and getting home. She has also expressed a strong desire to die at home, when the time comes.

On this admission to the hospital, Tess is found to be severely dehydrated, hypotensive, in acute renal failure, and in mild respiratory distress. Because there is the possibility that most of these problems could be reversed with aggressive hydration, the hospital doctors decide to admit her to the intensive care unit. Peter is at her side, and her family all arrive within eight hours. They have a family meeting right there in the waiting area, and decide that if the prognosis is very bad, they should transfer Tess to home with hospice care, in accordance with her wishes. During the initial visit by the oncologist, the family expresses Tess’ wishes, and is told that the prognosis is unclear. However, as the next two days pass, and Tess doesn’t improve, the family asks all the providers they encounter, including the ICU physicians, the ICU nurses, the nephrology consultant, and the pulmonary consultant, for information about prognosis. However, all of these providers defer a discussion about prognosis to the oncologist. Unfortunately, during these two days, the oncologist’s visits occur during times when designated decision-making family members aren’t immediately in the room. After two days of waiting, one of the ICU nurses takes it upon herself to call the oncologist’s nurse, conveying, nurse to nurse, the need for the oncologist to come in at a specified time and visit with the family to talk about prognosis. Three hours later, the oncologist arrives at Tess’s bedside, briefly confirms her grave prognosis, and leaves. While her family is making preparations to transfer Tess home, she dies in the hospital.

2.2 Problems With Using the ‘Team’ Concept

While several of the individuals, particularly the oncologist, may be responsible to a large extent for the communication problems in Tess’s story, remedying the situation is more complex than just a matter of training the providers in basic communication skills. Tess’s story contains underlying perceptions and actions, based in part on a disconnect between the team concept and what actually happens in care settings, creating barriers to communication regardless of the patient-centeredness of the oncologist or other providers. [8] A recent National Cancer Institute monograph lists six core functions of patient-clinician communication in cancer care. [9] These functions are consistent with those listed in a number of other consensus statements on patient-centered care in a variety of settings, [10,11] and include: 1) exchanging information, 2) responding to emotions, 3) making decisions, 4) fostering healing relationships, 5) enabling patient self-management, and 6) managing uncertainty. A team concept suggests that the team itself would be responsible for carrying out all six functions of communication, and that individual members of the team would coordinate their actions with each other in the service of this goal. [12] Education, then, would be a matter of skills training for medical teams focusing on the six functions. However, several difficulties arise when considering real-world cases and trying to determine who the team consists of, and who is responsible for which function at which point in time.

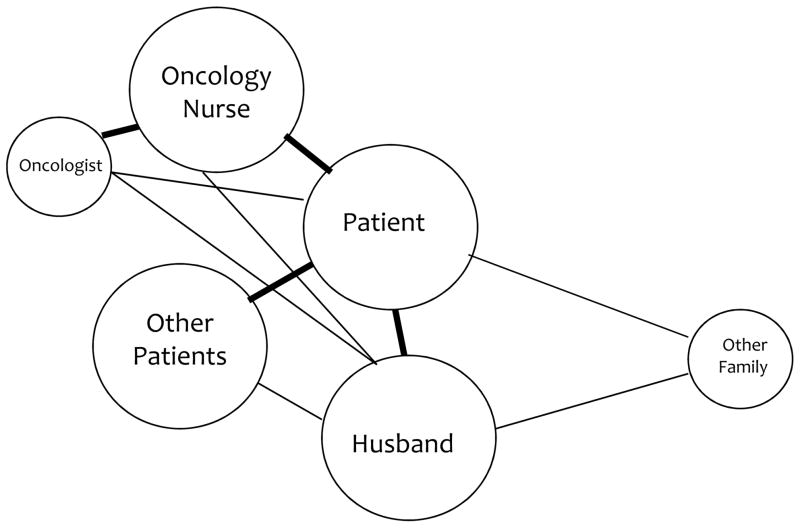

Consider the early phase of Tess’s story. When Tess was originally diagnosed and undergoing chemotherapy, the diagram shown in Figure 1 could represent the patterns of communication of the persons important to Tess’s care. In the diagram, Tess is the central character, consistent with a patient-centered model. The lines indicate multiple conversations over time, and thicker lines and larger circles represent those with greater importance in achieving the six functions. For example, consider the function of responding to and supporting emotions. In Tess’s case, the other patients in the infusion center, Tess’s husband Peter, and, to a lesser degree, the oncology nurse largely carry out this function. Are other patients, then, considered part of the medical team? Even functions as seemingly straightforward as information exchange become complex in this scenario. For information exchange, the oncologist may directly provide some information during his brief visits with Tess, but this information is then added to, modified, and constructed into new meanings by Tess’s conversations with the oncology nurse, other patients, and with her husband. [13]

Figure 1.

Patterns of Communication During Tess’s Outpatient Care

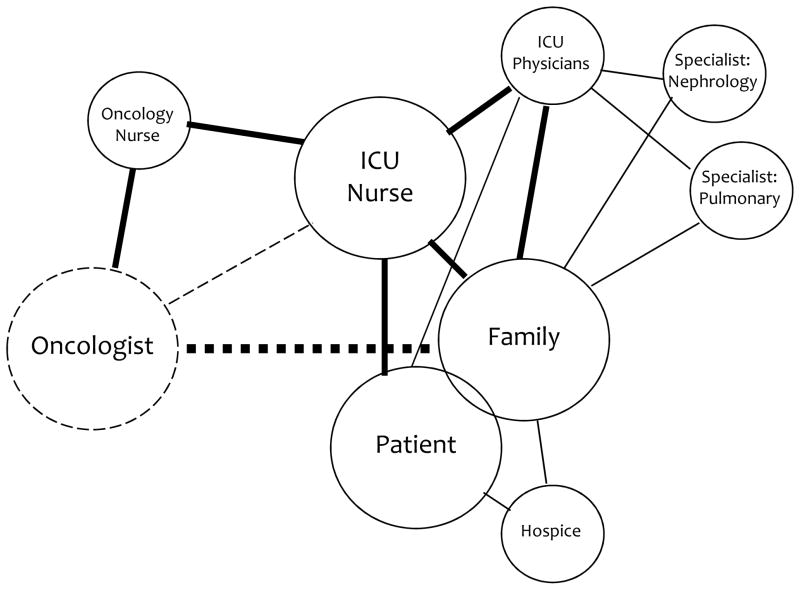

The situation becomes even more complicated when Tess enters the hospital for the final time (Figure 2). Now, the ‘target’ of patient-centered care becomes not only Tess, but also her family. Multiple conversations are now occurring over a very short span of time. However, a conversation between the ICU team and the oncologist, for the purpose of appraising the oncologist of the situation and the need for his presence, is NOT occurring, as indicated by the dashed line. Similarly, a critical conversation (as indicated by the bold dashed line) between the oncologist and the family about issues of prognosis does not occur until too late in the process to honor Tess’s wishes. This critical conversation eventually takes place because of some forward thinking by the ICU nurse, who initiates a conversation with the oncology nurse and works through that nurse’s influence to finally bring the oncologist into conversation with the family. In addition, the compartmentalization and increasing specialization of roles has led to the designation of certain kinds of knowledge (such as prognosis) as belonging to certain roles (such as the oncologist’s). This ‘ownership’ of knowledge creates barriers for other members of the healthcare team (such as the ICU physician, who may have more ongoing contact) to undertake the crucial conversation about prognosis with the family. [14]

Figure 2.

Patterns of Communication During Tess’s Inpatient Care

Cancer communication often occurs as a series of conversations that unfold asynchronously over time with multiple persons who may or may not be themselves communicating with each other. As such, we posit that the concept of a tightly integrated and coordinated team, while attractive from a patient care standpoint, may not be feasible or achievable in the current medical climate. [15] However, this does not mean that educators should avoid trying to create patient-centered communication within the cancer care system. Instead, it means that a concept that more realistically represents today’s cancer care is needed to guide educators’ efforts. A good candidate for an alternate conceptual frame is that of community. [16]

2.3. The ‘Community of Care’

The shift from ‘team’ to ‘community’ is a subtle one. Both teams and communities tend to organize around common themes or goals. Both involve multiple members with special areas of expertise to be leveraged in service to the common goal. Both involve multiple interpersonal relationships, as well as a relationship between each individual and the whole. [17,18] Spontaneous and planned events occur within both teams and communities. However, coordination of care in a team concept is a primary goal, [12] whereas in community, multiple members go about their individual caring activities in general support of providing quality care, but these activities are much less coordinated. The team concept implies deliberate coordination with input from all members, while in community, coordination is more organic – sometimes it occurs and sometimes it doesn’t, depending in part on whether someone takes responsibility for the big picture. [19]

A given cancer care community includes all who are relevant, from the patient, their family, oncologists, and oncology nurses, to surgeons, infusion nurses, palliative care personnel, physical therapists, radiation oncologists, clergy, and others. There may be differing definitions of ‘improving life’ that may range from extending lifespan, to improving quality of life, to ensuring a good death, and the members of the community may change or shift their positions over time. There are also hierarchies and power differentials that may inhibit certain members from being able to share their perspectives and opinions. All community members hold a unique and individual position that carries, to a greater or lesser degree, influence in the community’s web of relationships. [20]

A shift to the concept of community will necessarily disrupt the status quo in cancer care, because it expands the current focus on communication by only individuals to now be situated within multiple communication events occurring asynchronously throughout the community. This notion has implications for educators regarding designing interventions that aim to improve communication. [21]

3. Educating Communities to Provide Patient-Centered Cancer Communication

A growing number of innovative programs are being developed to improve the patient-centered communication skills of oncologists and other oncology providers. [22–28] Such training programs usually are aimed at strengthening the abilities of providers to achieve one or more of the six core functions of cancer communication, and they often include innovative experiential methods such as trigger videos, patient and provider stories, self-reflection, role-play, and supervised practice with standardized patients. [29–32] These programs provide a good foundation for patient-centered cancer communication at the level of the provider-patient dyad. However, in order to harness the power of community to improve the life of the patient, providers need additional abilities. Specifically, they need to: a) work from a common frame of reference, b) understand their own position and communications within the context of the larger community, and c) be proactive in managing the uncertainty that often is created by multiple conversations spread out over space and time. In this section, we discuss core principles for designing educational interventions aimed at communities of care, based on these community-level abilities.

3.1. A Common Frame of Reference

Programs to improve skills in patient-centered cancer communication should be offered to all providers in cancer care (not just oncologists) and should be transdisciplinary in nature. The term ‘providers’ can include not only other physicians (e.g., radiation oncologists, surgeons, etc), but also oncology nurses, infusion center staff, physical therapists, and any persons involved in the care of the patient and his/her family. By transdisciplinary, we mean that all providers in a given cancer patient’s care community are using a common framework to guide the communication process. This is in contrast to an interdisciplinary process, where all of the providers may have the same goals, but try to achieve those goals from a number of different conceptual frameworks. [33] For example, if an oncologist and her nursing staff and the staff of the associated infusion center are all trained in communication skills using the National Cancer Institute six-function framework, [9] then they are in a better position to coordinate their actions (e.g., making decisions about which person will focus on which function) to produce better overall communication than if each is approaching the patient from a different communicative framework. Transdisciplinary communication training necessitates that the community of cancer providers be in place, and in agreement on a common frame of reference with which to approach the communication process, particularly since the communication approaches taught in professional schools tend to differ significantly between allopathic and osteopathic medical schools, nursing schools, and technical schools. In addition, students from these schools have their attitudes and behaviors further shaped during their apprenticing experiences based on the norms of their respective professions and those of the institution where they apprenticed. [34] By using such norms and traditions as the starting point and incorporating them into a common frame of reference, the community of providers will be more likely to provide coordinated communication that enhances outcomes rather than causes confusion. Central to this approach is an explicit effort on the part of providers to form a collaborative community. [35]

3.2. Understanding One’s Position in the Context of Community

A key issue in educating providers to harness the full resources of the patient’s care community is that of raising the awareness of providers to the fact that they are not sole actors, but rather part of a community of care. [17] By understanding one’s own place and the places of others in the community of care, one is in a better position to coordinate with others to improve communication processes for the patient. For example, consider the actions of the ICU nurse when Tess was admitted to the intensive care unit. Her family needed to have a discussion with the oncologist in order to move forward with care planning, but the oncologist was not returning the ICU nurse’s direct pages. None of the other specialists would talk with the family about prognosis because they felt this subject to be in the purview of the oncologist, but none had actually spoken with the oncologist, either. The ICU nurse understood herself to be in a relatively compromised position, in that she did not have the authorization or specialized knowledge to talk with Tess’s family about prognosis and she also did not possess the authority to force the oncologist to come in to talk with the family. She did, however, realize that the oncologist’s nurse had a longstanding relationship with the oncologist, and this relationship could provide the necessary influence to spur the oncologist into action. Further, her shared identity as a nurse could facilitate her discussion with the oncologist’s nurse. By taking the route of communicating with the oncologist through the oncologist’s nurse, the ICU nurse facilitated the patient centered cancer communication functions of exchanging information, making decisions, and managing uncertainty. [36]

In order to train learners to think about community, educators need to challenge some commonly held assumptions about teaching and learning. In most learning environments, there is a dyadic relationship, either between an individual teacher and student (as in the apprenticeship form of teaching that occurs in clinical environments), or between a teacher and a group of students (as in a classroom or didactic lecture environment). Such traditional education structures do not foster a sense of community because they reduce the conceptualization of the learning process to a one-way flow of information from expert to novice. It is easy for providers to transfer such educational concepts to patient care, [34] because of similarities between this traditional educational scenario and the clinical scenario, where a gap in biomedical knowledge often exists between providers and patients. In order to better help learners to bring a sense of community to their activities, the structure of the learning environment would ideally foster a more nuanced understanding of the backgrounds, strengths, weaknesses, and contributions that all (students and teacher alike) who are members of the community bring to the task of learning. Parker Palmer, a respected teacher and writer, has called such a learning environment “the community of truth”, and he uses this concept as a foundation for thinking about what kinds of educational activities will best help educators to not only achieve content-oriented objectives, but interpersonal communication process objectives as well. [37] A number of educators in medical settings have used innovative techniques aimed at fostering students and physicians to have an expanded view of who is involved in the care of the patient, and how relationships can be leveraged to promote healing. These include practice genograms, ‘life space’ diagramming of the community caring for patients, and a variety of small group reflection techniques. [38–40] In addition, educators whose aim is to expand individuals’ notions of who is involved in care could strive to introduce non-traditional content and processes into traditional structures. For example, what would happen if oncology nurses, radiation technologists, or even patients themselves participated in traditional ‘tumor board’ conferences? By incorporating strategies to create practitioners’ reflection about their unique positions in the care community, educators will better equip providers to harness the power of communities to achieve the six core functions of patient-centered cancer care.

3.3. A Proactive Stance Toward Uncertainty Management

An important difference between a team and a community is that roles are not usually as tightly defined in a community. This gives members leeway to act and communicate in ways beyond what their role mandates. This may or may not be positive for the patient. In Tess’s case, a less rigid perception of role could have given the ICU doctors, specialty doctors, and the ICU nurses the ability to talk with Tess’s family, rather than all deferring to the oncologist. We suspect that these other providers did not take this route because of uncertainty. [41] By all deferring to the one member of the ‘team’ who had authority to have prognostic discussions, the other providers reduced the potential uncertainty of multiple prognostic opinions at the expense of the family’s request for information. A community approach to this situation would potentially allow any of the providers to discuss prognosis, but would also require the providers to recognize and manage the potential for increased uncertainty that multiple opinions might create. Such management would consist of: 1) acknowledging and preparing the patient or family for uncertainty, e.g., “All of the doctors taking care of you will probably have opinions about how bad this is, and we may have differences of opinion about this…”; 2) framing one’s communications so that the patient or family understands the source of the information and the limitations of the source, e.g., “I can let you know what I think, but my expertise is in kidney problems, and the oncologist may have a different and more accurate view…”; and 3) designation of one or more providers to help patients and families make sense about points of uncertainty, e.g., “When you have heard all of the opinions, let’s you and I sit down and try to figure out what is the right thing to do…” This last task is particularly important for patients who struggle with decision making, or who want or need their doctors to take a more directive role. In such circumstances, caution must be taken to avoid displacing the emotional burden of information management responsibilities from physician to patient in the name of patient-centeredness or empowerment. Instead, it is critical for one or more of the community’s providers to accept this sense-making role, and to take initiative to be a moderator of information flow between all members of the healing community. In an ideal scenario, this would be the provider or providers with the greatest trust and continuity with the patient. In Tess’s outpatient phase of chemotherapy, the oncology nurse facilitated this by regularly meeting with Tess, talking about what Tess had heard from various other persons and sources, and providing additional information to help Tess understand, communicate, and make decisions about her ongoing treatment.

Beyond the educational goals already noted (i.e., a common frame of reference and understanding one’s position), uncertainty management requires that providers become comfortable acknowledging and working with uncertainty within the context of cancer conversations. Unfortunately, research on communication would suggest that the opposite is the norm. [42] Educators need to recognize this and structure educational activities to provide a safe environment where learners can practice uncertainty management by testing hypotheses, considering each others’ ideas, and freely brainstorming solutions to real-world problems. A promising method for creating such an environment is Team-Based Learning (TBL). Team-Based Learning is an instructional format that was originally developed in business education, but has increasingly been used in medical education. [43] One of the cornerstones of TBL is constructive controversy, [44] a situation where multiple teams make decisions about a common real-world problem, and then, using course concepts, work collaboratively as an entire class to address disagreements and discuss alternative solutions to the problem. While TBL uses the concept of teams to motivate and prepare learners for in-class sessions, it also creates open, safe discussions among multiple teams in the community of the classroom, and gives learners experience in working with, acknowledging, and managing the uncertainty of complex problems.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1 Discussion

The shift from a concept of teams to that of care communities is not to be taken lightly. Often, transformations that seem so necessary, and which the members of organizations themselves endorse, become very difficult to achieve in practice. We anticipate that a community concept might be perceived as a threat to existing hierarchies, and that acting within this concept might create conflict and discomfort for community members who are not empowered in the current order. Education, then, is only one part of a multi-faceted, multidisciplinary effort to transform cancer care. Equally important is the need for enlightened leadership on the part of those in power in order to increase the feasibility of a community model. An example of such leadership is the recent initiative at the Indiana University School of Medicine to create a more relationship-oriented organizational culture. [45]

4.2 Conclusion

As the recent National Cancer Institute’s monograph on patient-centered cancer care [9] points out, significant strides have been made in educating individual providers to increase their own skills in conducting one-on-one conversations with patients and families. The next step is to begin to educate caregivers to function as communities of care, to provide patients and families with multiple communication experiences that build upon one another, and that in total fulfill all six functions of patient-centered cancer care. In order to do this, providers need to work from a common frame of reference, understand their own position in the community of care, and be proactive in framing their own communications to exist in concert with those of other providers.

4.3 Practice Implications

The choices that educators make in terms of how they present content, who they present that content to, what activities they have learners participate in, and what pedagogical methods they use can help to foster the community objectives of patient-centered cancer education.

Acknowledgments

The Houston Center is supported by HFP 90-020 from the Office of Research and Development, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Drs. Haidet and Teal are supported by K07-HL85622 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The funders had no role in writing or the decision to submit this report for publication.

Footnotes

None of the authors has any actual or potential conflicts of interest, including any financial, personal, or other relationships with other people or organizations (within 3 years) that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence this work.

The opinions contained herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, The Pennsylvania State Univeresity, or Baylor College of Medicine.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fallowfield L. Can we improve the professional and personal fulfillment of doctors in cancer medicine? Br J Cancer. 1995;71:1132–3. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakemeier RF. Communication: a crucial concern for cancer curricula. J Cancer Educ. 1993;8:89–90. doi: 10.1080/08858199309528214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arora NK. Advancing research on patient-centered cancer communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:301–2. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stiefel F, Favre N, Despland JN. Communication skills training in oncology: it works! Recent Results Cancer Res. 2006;168:113–9. doi: 10.1007/3-540-30758-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Current concepts of communication skills training in oncology. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2006;168:105–12. doi: 10.1007/3-540-30758-3_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaffan J, Dacre J, Jones A. Educating undergraduate medical students about oncology: a literature review. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1932–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.6617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakobsson S, Ekman T, Ahlberg K. Components that influence assessment and management of cancer-related symptoms: an interdisciplinary perspective. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:691–8. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.691-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carline JD, Curtis JR, Wenrich MD, Shannon SE, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG. Physicians’ interactions with health care teams and systems in the care of dying patients: perspectives of dying patients, family members, and health care professionals. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00537-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr . Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2007. NIH Publication No 07-6225. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makoul G. Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Acad Med. 2001;76:390–3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200104000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. [accessed January 2009];ACGME Outcome Project. www.acgme.org/outcome/

- 12.Boyle FM, Robinson E, Heinrich P, Dunn SM. Cancer: communicating in the team game. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:477–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perry E, Swartz J, Brown S, Smith D, Kelly G, Swartz R. Peer mentoring: a culturally sensitive approach to end-of-life planning for long-term dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:111–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blaauwbroek R, Zwart N, Bouma M, Meyboom-de Jong B, Kamps WA, Postma A. The willingness of general practitioners to be involved in the follow-up of adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:292–7. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0032-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lienard A, Merckaert I, Libert Y, et al. Factors that influence cancer patients’ and relatives’ anxiety following a three-person medical consultation: impact of a communication skills training program for physicians. Psychooncology. 2008;17:488–96. doi: 10.1002/pon.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inui TS. What are the sciences of relationship-centered primary care? J Fam Pract. 1996;42:171–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tressolini CP The Pew-Fetzer Task Force. Health Professions Education and Relationship-Centered Care. San Francisco: Pew Health Professions Commission; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beach MC, Inui TS the Relationship-Centered Care Research Network. Relationship-centered care: a constructive reframing. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S3–S8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergenmar M, Nylen U, Lidbrink E, Bergh J, Brandberg Y. Improvements in patient satisfaction at an outpatient clinic for patients with breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:550–8. doi: 10.1080/02841860500511239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Candib LM, Gelberg L. How will family physicians care for the patient in the context of family and community? Fam Med. 2001;33:298–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dix L, Steggles E, Baptiste S, Risdon C. A process-oriented approach to enhancing interprofessional education and collaborative relationship-centered care: the PIER project. J Interprof Care. 2008;22:321–4. doi: 10.1080/13561820801886370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:453–60. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, Saul J, Duffy A, Eves R. Efficacy of a cancer research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:650–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fraser HC, Kutner JS, Pfeifer MP. Senior medical students’ perceptions of the adequacy of education on end-of-life issues. J Palliat Med. 2001;4:337–43. doi: 10.1089/109662101753123959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukui S, Ogawa K, Ohtsuka M, Fukui N. A randomized study assessing the efficacy of communication skill training on patients’ psychologic distress and coping: nurses’ communication with patients just after being diagnosed with cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:1462–70. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surbone A. Cultural aspects of communication in cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:235–40. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butow P, Cockburn J, Girgis A, et al. Increasing oncologists’ skills in eliciting and responding to emotional cues: evaluation of a communication skills training program. Psychooncology. 2008;17:209–18. doi: 10.1002/pon.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman M, Steinberg M. Development and implementation of a curriculum in communication skills and psycho-oncology for medical oncology fellows. J Cancer Educ. 2002;17:196–200. doi: 10.1080/08858190209528837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faulkner A. Using simulators to aid the teaching of communication skills in cancer and palliative care. Patient Educ Couns. 1994;23:125–9. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fallowfield L, Lipkin M, Hall A. Teaching senior oncologists communication skills: results from phase 1 of a comprehensive longitudinal program in the United Kingdom. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1961–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorin S, Rho L, Wisnivesky JP, Nierman DM. Improving medical student intensive care unit communication skills: a novel educational initiative using standardized family members. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2386–91. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000230239.04781.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suipiot S, Bonnaud-Antignac A. Using simulated interviews to teach junior medical students to disclose the diagnosis of cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2008;23:102–7. doi: 10.1080/08858190701849437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grey M, Connolly CA. Coming together, keeping together, working together: interdisciplinary to transdisciplinary research and nursing. Nurs Outlook. 2008;56:102–7. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haidet P, Stein HF. The role of the student-teacher relationship in the formation of physicians: the hidden curriculum as process. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S16–S20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobie S. Viewpoint: reflections on a well-traveled path: self-awareness, mindful practice, and relationship-centered care as foundations of medical education. Acad Med. 2007;82:422–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000259374.52323.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitch MI, Maxwell C. Bisphosphonate therapy for metastatic bone disease: the pivotal role of nurses in patient education. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:709–13. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.709-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palmer P. The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McIlvain H, Crabtree B, Medder J, Stange KC, Miller WL. Using practice genograms to understand and describe practice configurations. Fam Med. 1998;30:490–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haidet P, Hatem DS, Fecile ML, et al. The role of relationships in the professional formation of physicians: case report and illustration of an elicitation technique. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;72:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fryer-Edwards K, Arnold RM, Baile W, Tulsky JA, Petracca F, Back A. Reflective teaching practices: an approach to teaching communication skills in a small-group setting. Acad Med. 2006;81:638–44. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000232414.43142.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kassirer JP. Our stubborn quest for diagnostic certainty: a cause of excessive testing. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1489–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906013202211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quill TE, Suchman AL. Uncertainty and control: learning to live with medicine’s limitations. Humane Med. 1993;9:109–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haidet P, Fecile ML. Team-based learning: a promising strategy to foster active learning in cancer education. J Cancer Educ. 2006;21:125–8. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2103_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson DW, Johnson RT, Smith KA. Constructive controversy. Change. 2000;32:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cottingham AH, Suchman AL, Litzelman DK, et al. Enhancing the informal curriculum of a medical school: a case study in organizational culture change. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:715–22. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0543-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]