Abstract

We designed and tested three PilA-derived vaccine candidates in a chinchilla model of ascending nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHI)-induced otitis media (OM). Delivery of antiserum directed against each immunogen conferred varying degrees of protection. Presentation of a B-cell epitope derived from the OMP P5 adhesin at the N-terminus of recombinant soluble PilA protein (as opposed to the C-terminus), resulted in a protective chimeric immunogen that combined epitopes from two distinct NTHI adhesins (type IV pili and OMP P5). Incorporating protective epitopes derived from two NTHI adhesins/virulence determinants into a single pediatric vaccine candidate to prevent OM has multiple potential inherent advantages.

Keywords: chinchilla, otitis media, COPD

Introduction

NTHI is a commensal that exists primarily as a benign member of the colonizing normal flora within the nasopharynx of its human host. However, it is also capable of causing a number of distinct diseases of the airway including bronchitis, sinusitis, adenotonsilitis, otitis media and exacerbations of COPD, among others, when normal host defenses are compromised [1]. Since the first step in these disease processes is colonization, mechanisms to adhere to and maintain long-term residence within the nasopharyngeal micro-environment are considered ‘virulence determinants’ for NTHI. The importance of being able to adhere to the mucosal epithelial surfaces of its human host is reflected in the multiplicity of adhesins expressed by NTHI (reviewed in [2]).

In our attempts to develop vaccine candidates to prevent those diseases of the respiratory tract caused by NTHI, we have focused primarily on two of these adhesins. The OMP P5 homologous adhesin (also called fimbrin or P5-fimbrin) and the type IV pilus (Tfp). As such, we previously designed, and have extensively tested a 40-mer synthetic chimeric peptide immunogen called ‘LB1’, which contains a B-cell epitope of the NTHI OMP P5-homologous adhesin [3]. This 19-mer protective B-cell epitope is co-linearly synthesized N-terminal to a promiscuous T-cell epitope derived from measles virus fusion protein to generate the 40-mer peptide immunogen LB1. While this chimeric immunogen is highly efficacious in preventing OM in both chinchilla and rat models of direct middle ear and/or lung challenge [3, 4], as well as preventing ascending OM due to NTHI in the chinchilla passive transfer superinfection model [5, 6], the incorporation of a T-cell promiscuous epitope within a pediatric vaccine formulation was considered potentially problematic.

Thus, we have been contemplating how to best replace the measles virus fusion epitope without reducing the overall efficacy of the 40-mer immunogen, LB1. The use of either diphtheria toxoid or tetanus toxoid as potential alternative carriers did not prove to be appropriate for various reasons (author’s unpublished data). Nevertheless, in complementary ongoing efforts in the laboratory to identify novel virulence determinants of NTHI, we recently demonstrated that NTHI express functional Tfp, which are known to play a role in the pathogenesis of other Gram-negative organisms such as Neisseria meningitidis, N. gonorrhoeae, enteropathogenic E. coli and Moraxella catarrhalis [7–11]. These structures are classically involved in twitching motility, adherence and colonization, biofilm formation and competence; functions which are similarly performed by NTHI Tfp [12–14]. Within a panel of 24 low-passage clinical H. influenzae isolates recovered from patients in the U.S. or Europe, including isolates representative of those causing a variety of either acute or chronic respiratory tract diseases and meningitis, a single pilA gene (the gene that encodes the majority protein subunit of Tfp) was identified. Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of these twenty-four PilA proteins revealed extensive homology ([15], and author’s unpublished data).

The surface location of the Tfp, their demonstrated conservation in terms of extremely limited deduced amino acid sequence diversity, the presence of a single pilA gene, and their role mediating important biological functions (including adherence and colonization), made them a potentially attractive target for vaccine development. Whereas the described features of NTHI Tfp would fulfill those typically desired as minimal requirements for a vaccine target, the rational design of a broadly protective and highly efficacious vaccine candidate intended for the prevention of NTHI-induced diseases of the respiratory tract requires an understanding of the immunological nature of the protein subunit that comprises the Tfp. This is particularly essential when one is attempting to design a vaccine candidate for a group of microorganisms as heterogeneous as NTHI, and when there is a history for difficulties encountered using Tfp-derived strategies in vaccine development strategies for other infectious agents (i.e. N. gonorrhoea, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Burkholderia mallei) [16–19].

As such, an optimal strategy for vaccine design would include understanding the role(s) of Tfp in both nasopharyngeal colonization and during active disease, in addition to knowing how this structure (and the subunit protein that comprises it) is responded to immunologically, and perhaps uniquely, under these two extremes. Moreover, since the correlates of immune protection can be quite different in the upper vs. lower airway, we wanted to study the immune response to NTHI Tfp using clinical samples obtained from patients with disease of both niches. Thereby, we recovered serum samples from both children and adults who were simply colonized with NTHI in the absence of active disease, as well as from children who were otitis prone and experiencing OM, and from adults during an exacerbation of COPD due to NTHI. In addition to serum samples, we also recovered local specimens from either the middle ear (effusion fluid) or the lower airway (sputum) of those patients with ongoing disease.

To epitope map the immunodominant domains of PilA, the above clinical specimens were assayed by ELISA, Western blot and biosensor against first a series of overlapping 15-mer peptides, then against ~34-mer sequential peptides designed to mimic the four quartiles of the PilA protein subunit from a truncated N-terminus to the native C-terminus. These data were then used to facilitate the design of two chimeric vaccine candidates (called chimV3 & chimV4) which were tested in a chinchilla passive transfer viral-bacterial superinfection model [5, 6, 20], alongside soluble recombinant PilA protein, for relative ability to prevent the development of ascending experimental OM due to NTHI.

Materials & Methods

Pediatric serum and middle ear fluids

Blood for serum was collected from 21 healthy children and 51 OM-prone children, whereas middle ear effusions were collected from 40 OM-prone children at the time of surgery. All children were between the ages of 6 months and 4.5 years, and once collected, samples were stored at −80°C until used. Healthy children included in the study were defined as having no evidence of OM, or any other respiratory tract illness, as indicated by their physician during a well-child visit, and were not currently taking antimicrobials at the time of sample collection. OM-prone children (i.e. children who experience ≥ 4 episodes of AOM in 1st yr. of life or ≥ 6 episodes by 2nd yr. of life) [21] were selected based on documented chronic serous OM or recurrent acute OM as noted by their pediatric otolaryngologist. Clinical specimens for OM prone children (i.e. blood and middle ear fluids) were obtained during surgery for tympanostomy tube insertion after obtaining informed consent from their parent or guardian, and were in concordance with all institutional and federal guidelines for the use of human subjects.

Adult serum and sputum supernatant

Serum and sputum supernatant samples were collected from adults with COPD who were followed in the COPD Study Clinic at the Buffalo VA Medical Center as part of prospective study described in detail previously [22, 23]. Patients were seen monthly. At each clinic visit, clinical information, sputum and serum samples were collected. Paired pre- and post-exacerbation serum and sputum samples were identified. An exacerbation due to NTHI was defined as the onset of clinical symptoms of exacerbation (increased sputum volume, increased sputum purulence and increased shortness of breath compared to baseline symptoms) simultaneous with the acquisition of a new strain of NTHI based on molecular typing of strains obtained at monthly clinic visits. Pre-exacerbation samples were collected 1 to 3 months prior to the exacerbation and post-exacerbation samples were collected 1 to 3 months following the exacerbation. Twenty such pairs of serum and sputum supernatant samples were included.

A set of 10 paired serum and sputum supernatant samples were identified as negative controls. These samples were collected from adults with COPD from the same study. The samples were collected when patients were clinically stable with no symptoms of exacerbations and also with negative sputum cultures for NTHI or other respiratory tract pathogens for at least 6 months before and after the time of collection.

Synthesis of peptides

A series of thirteen approximately 15-mer synthetic peptides with a 5-residue overlap (Table 1, ‘overlap peptide’) (Note: due to an overall lack of significant reactivity with the majority of OLP peptide, only OLP3 is shown) and a set of three 34- to 35-mer sequential quartile peptides (Table 1, ‘Tfp quartile peptides’) were synthesized in order to epitope map the PilA protein of NTHI strain #86-028NP [12]. Peptides OLP3, TfpQ2, TfpQ3 and TfpQ4 were used to represent the four approximate quartiles of mature PilA from truncated N-terminus to the native C-terminus (Table 1). Synthesis, purification and sequence confirmation of all synthetic peptides was performed as described [3, 24], using established techniques of the Peptide and Protein Engineering Laboratory at The Ohio State University. Amino acid analysis and mass spectral analysis was used to confirm the purity, composition and amino acid sequence of each peptide (data not shown).

Table 1.

Schematic representation of the amino acid sequence of mature NTHI strain #86-028NP PilA protein, rsPilA and PilA-derived synthetic peptides.

| Mature PilA | FTLIELMIVIAIIAILATIAIPSYQNYTKKAAVSELLQASAPYKADVELCVYSTNETTNCTGGKNGIAADITTAKGYVKSVTTSNGAITVKGDGTLANMEYILQATGNAATGVTWTTTCKGTDASLFPANFCGSVTQ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rsPilA | GSHMTKKAAVSELLQASAPYKADVELCVYSTNETTNCTGGKNGIAADITTAKGYVKSVTTSNGAITVKGDGTLANMEYILQATGNAATGVTWTTTCKGTDASLFPANFCGSVTQ | |||

| OLP3 | IPSYQNYTKKAAVSE | |||

| TfpQ2 | ELLQASAPYKADVELCVYSTNETTNCTGGKNGIA | |||

| TfpQ3 | ADITTAKGYVKSVTTSNGAITVKGDGTLANMEYI | |||

| TfpQ4 | LQATGNAATGVTWTTTCKGTDASLFPANFCGSVTQ | |||

Biosensor analysis

Analysis of the interaction between synthetic peptides and antibodies present in sera, middle ear fluids or sputum supernatant samples was examined using a Biacore 3000 instrument as described [25–27] and all reagents were purchased from Biacore (Uppsala, Sweden). Briefly, peptides were suspended in sodium acetate buffer [at pH 4.75 for OLP3 and TfpQ3, or at pH 4.0 for TfpQ2 and TfpQ4], prior to immobilization to the surface of an activated reagent grade CM5 sensor chip using amine coupling chemistry. For interaction analysis, 15 μl of serum (diluted 1:2 in HBS-EP buffer plus 1 mg carboxymethyldextran/ml), middle ear fluids (diluted 1:5), and sputa (diluted 1:2) were injected across the sensor chip surface at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. The relative amount of antigen- or immunogen-specific antibody in each sample was calculated as the difference in resonance units (RU) obtained 5 seconds before and 45 seconds after each sample was injected. The sensor chip surface was regenerated between samples with 25 mM NaOH.

After biosensor analysis, due to variability amongst patients in terms of relative amount of antigen-specific antibody (i.e. that directed towards the PilA protein subunit of the Tfp of NTHI) within serum, effusion or sputum supernatant specimens, data obtained from each patient group/specimen type were clustered based upon the demonstrated greatest overall recognition of any of the four quartile peptides OLP3, TfpQ2, TfpQ3 or TfpQ4 (regardless of the magnitude of that response). The association between each group of patients and their response to a particular peptide was tested via Chi Square analysis wherein individual peptide deviations from chance were tested with standardized residuals (z). Bonferroni method was used to maintain the overall type I error rate for testing multiple hypotheses. In addition, a mixed model was used for multiple variable analysis to account for within-patient variations.

Design and synthesis or expression of synthetic, recombinant or recombinant chimeric vaccine candidates used here

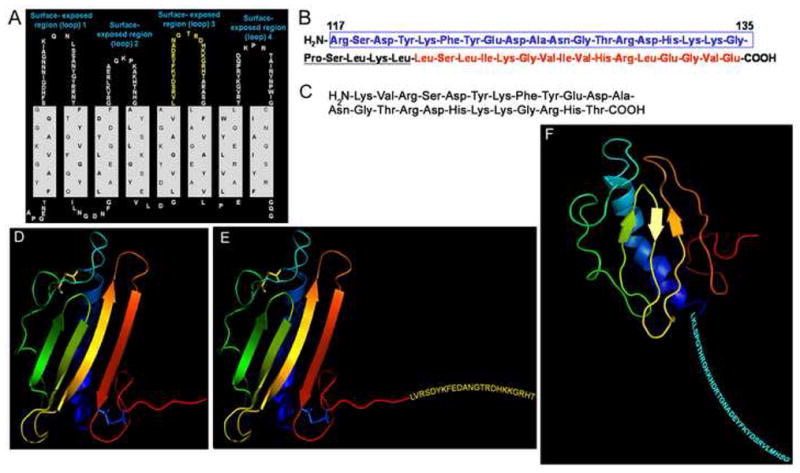

LB1 and LB1(1): the vaccine candidate ‘LB1’ is a 40-mer synthetic peptide in toto that contains a 19-mer B-cell epitope derived from the NTHI OMP P5-homologous adhesin (Fig. 1A, see peptide chain represented in yellow font within surface-exposed region 3) that has been co-linearly synthesized with a small linker peptide followed by a promiscuous T-cell epitope derived from measles virus fusion protein [3] (Fig. 1B). The vaccine candidate ‘LB1(1)’ (Fig. 1C) is a 24-mer synthetic peptide that represents only the 19-mer B-cell epitope from the OMP P5-homologous adhesin (as incorporated into the 40-mer peptide ‘LB1’) to which 2 additional N-terminal and 3 additional C-terminal residues have been added.

rsPilA: recombinant soluble PilA (Table 1 & Fig. 1D) is a 114 residue recombinant peptide that includes the deduced amino acids representing mature PilA derived from NTHI strain #86-028NP, less 27 native N-terminal hydrophobic residues, but to which 4 unique N-terminal residues (GSHM) remain from either the vector or the restriction site utilized in the preparation of this recombinant peptide antigen.

chimV3 and chimV4: these vaccine candidates were generated in an attempt to use a unique NTHI-derived protein as both a carrier and immunogenic partner for the 24-mer LB1(1) B-cell epitope of the OMP P5 adhesin as described above. We have thus replaced the measles virus fusion protein-derived promiscuous T-cell epitope of the 40-mer immunogen LB1 (described above and depicted in red font in Fig. 1B) with recombinant soluble PilA. In each of these chimeric recombinant immunogens, rsPilA was used as both a unique immunogenic protein, as well as to carry the LB1(1) epitope at either its C- or N-terminus [chimV3 (Fig. 1E) or chimV4 (Fig. 1F), respectively]. When the LB1(1) epitope was placed at the truncated N-terminus of rsPilA, a small 6-residue linker peptide (GPSLKL), positioned between the LB1(1) epitope and the N-terminus of rsPilA was incorporated into the design

Figure 1.

(A) hypothetical model of the N-terminal portion of OMP P5-homologous adhesin of NTHI depicting the four predicted surface-exposed regions. The amino acid sequence in yellow font represents the portion of region (or loop) three, from which the B-cell epitope of LB1 is derived. (B) ‘LB1’ is a 40-mer, synthetic, chimeric peptide comprised of a 19-mer B-cell epitope (blue boxed sequence) from the predicted surface exposed region 3 of the OMP P5-homologous adhesin discussed relative to Panel A, a small linker peptide (underlined sequence), and a T-cell promiscuous epitope from measles fusion virus protein (MVF; sequence in red font). In the present study, we sought to replace this latter T-cell epitope from MVF with a second NTHI adhesin protein (or epitope thereof) derived from the Tfp PilA protein. (C) the 24-mer vaccine candidate called ‘LB1(1) which is that sequence depicted in yellow font in Panel A. (D) Computer model of N-terminally truncated structure of the PilA protein of NTHI 86-028NP as predicted using MSI Quanta. Colors used in 3-D model approximate the same regions mimicked by similarly colored synthetic quartile peptides used for epitope mapping here. (E) Chim-V3: the 24-mer peptide LB1(1) is presented extending beyond the C-terminal glutamine residue of rsPilA. (F) Chim-V4: the LB1(1) peptide plus a short linker sequence is presented at the N-terminus of rsPilA [Note: in Panel F the 3-D model of rsPilA is turned on its axis from that depicted in Panels D & E in order to better show the placement of the LB1(1) epitope at the N-terminus of this recombinant protein].

To generate chimV3 and chimV4, we relied upon the services of Blue Heron Biotechnology (Bothell, WA) to first optimize codon usage for E. coli, then requested custom gene synthesis to generate the nucleotide sequence required to encode these recombinant chimeric immunogens. Once received, customized genes were cloned into an expression vector pET15b (Novagen, Madison, WI) as an NdeI to BamHI fragment. The plasmid was transformed into Origami B (DE3) cells and expression of the protein induced in mid-log phase cells with 0.4 mM IPTG. Bacterial cells were harvested and resuspended in BugBuster plus Benzoate-Nuclease (Novagen). The soluble fraction was applied to a nickel column (Novagen) and the proteins were purified with an imidazole gradient. His-tags were removed and recombinant proteins were purified via use of Thrombin Cleavage/Capture kit (Novagen). These purified proteins were used to generate polyclonal anti-chimV3 or anti-chimV4 by immunization of chinchillas, as described below. Anti-rsPilA, anti-LB1 and anti-LB1(1) sera were also prepared by immunization of chinchillas (described below).

Generation of polyclonal antisera and assessment by ELISA and Western blotting to determine titer and specificity

To generate immune serum for passive transfer in Study A, five cohorts of two adult chinchillas (Chinchilla lanigera; Rauscher’s Chinchilla Ranch, LaRue, OH) each were established. Chinchillas were parenterally immunized by subcutaneous (SQ) injection of 10 μg of either LB1, LB1(1), rsPilA, or chimV3 administered co-mixed with the adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL; Corixa) or with MPL alone (adjuvant-only control cohort). Two identical boosts were delivered at 21-day intervals. Blood for serum was collected 10 days after receipt of the final immunizing dose.

Immune serum for passive transfer in Study B was generated by SQ immunization of three cohorts of four adult chinchillas each with 10 μg of either LB1, rsPilA or chimV4, delivered co-mixed with the adjuvant AS04 (MPL plus aluminum hydroxide; GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Inc.), or with AS04 alone (adjuvant-only control cohort). Two identical boosts were given at monthly intervals. Blood for serum was collected 15 days after receipt of the final immunizing dose.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Western blotting of chinchilla antisera was performed as described previously [3, 5, 6, 20]. For ELISA, sera were assayed in a 96-well plate format against the immunogen delivered (0.2 μg protein/well). Titer was defined as the reciprocal of the serum dilution that yielded an OD450 value of 0.1 greater than control wells which contained all components except serum. ELISA assays were performed a minimum of three times and results are reported as the geometric mean. Western blotting was performed against 1 μg of the respective immunogen using immune serum diluted 1:100 and detected with HRP-protein A (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA). Color was developed with CN/DAB substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Chinchilla passive transfer, superinfection model of ascending experimental OM due to NTHI

To assess the protective efficacy of immune sera, in Study A, five cohorts of six juvenile chinchillas each were established, and for Study B, four cohorts of 10 juvenile chinchillas each were established. All animals were confirmed to be free of middle ear disease as determined by video otoscopy and tympanometry. Prior to enrollment, naive serum from each animal was screened for pre-existing reactivity to NTHI strain 86-028NP outer membrane proteins (OMPs) via Western blotting. Animals with highly reactive sera were excluded from the study.

In this animal model [5, 6, 20, 28], juvenile chinchillas are first given a viral upper respiratory tract infection with a wild type human adenovirus. To do so, chinchillas were inoculated intranasally (IN) by passive inhalation of 1.9 × 107 TCID50 adenovirus (serotype 1), delivered in a volume of 200 μl, with 100 μl administered per naris as described previously [3, 5, 6, 20, 29, 30]. When virus-induced compromise of Eustachian tube function is maximum (~7 days after viral challenge), chinchilla immune serum pools (previously generated in adult animals by SQ immunization, as described above) are transferred to cohorts of juvenile animals by cardiac puncture at a volume of 5 ml undiluted immune serum per kg body weight. One day later, all animals are challenged IN with 1 × 108 CFU NTHI strain #86-028NP [3, 5, 6, 20, 31, 32] via passive inhalation of 200 μl bacterial suspension, with 100 μl administered per naris. Animals are then monitored blindly, on a daily basis, for signs and severity of OM (scored on a 0 – 4+ scale) using video otoscopy and tympanometry. This period of observation and scoring of disease severity continues for 35 days after bacterial challenge. Cohorts are compared for relative incidence and severity of induced experimental OM compared to both a cohort that received anti-adjuvant only serum (negative control) and a cohort that received anti-LB1 + adjuvant serum (positive control based on multiple prior studies) [3, 5, 6].

To assess the development of experimental disease, all animals were evaluated daily by video otoscopy using a 0°, 3-in probe connected to a digital camera system (MedRx, Inc., Largo, FL) for signs of tympanic membrane inflammation and/or presence of fluid within the middle ear space and were rated on a 0 to 4+ scale [5, 6, 20]. Tympanometry (EarScan, South Daytona, FL) was also performed to monitor changes in middle ear pressure, tympanic membrane compliance and tympanic width [20, 33–35]. For the entire 26-day (Study A) or 35-day (Study B) post-bacterial challenge assessment period, observers were blinded as to the serum pool administered and knowledge as to which cohort a given chinchilla was assigned. At the completion of each study, efficacy determinations were calculated based on the cumulative percentage of ears with OM in the cohorts that received immune serum versus the cohort that received anti-adjuvant serum. Animal studies were conducted in compliance with all institutional and federal guidelines.

Flow cytometry to detect relative ability of antisera directed against PilA-derived immunogens to recognize native pili as expressed by viable NTHI

We assessed chinchilla anti-rsPilA, anti-chimV3, or anti-chimV4 serum pools for ability to recognize and bind to whole, unfixed NTHI strain #86-028NP using FACS analysis [36]. Naïve chinchilla serum was used as a negative control and anti-NTHI total OMP serum was used as a positive control. NTHI strain 86-028NP was incubated with either chinchilla anti-chimV3, chinchilla anti-chimV4 or chinchilla anti-rsPilA serum for 1 hr followed by detection with FITC-conjugated Protein A (Zymed). Cells were washed and analyzed with an Epics XL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). A total of 20,000 events were collected per sample and data analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR). Assays were performed a minimum of three times.

Results

Immunoreactivity of pediatric and adult serum samples with synthetic peptides derived from PilA in a biosensor assay

Overall, the use of the series of fifteen short, 15-mer overlapping sequential peptides that were designed to mimic the Tfp subunit (PilA) from N- to C-terminus, did not reveal significant reactivity overall when any clinical sample type was tested (data not shown). This result suggested that the 15-mer peptides were likely too short to define a immune-recognizable domain, or perhaps that the immunodominant domain(s) of PilA were discontinuous in nature. However, when OLP3 plus the longer 34- to 35-mer sequential peptides (called TfpQ2, TfpQ3, TfpQ4) (Table 1), that were designed to mimic the four approximate quartiles of PilA were used, there was recognition by all clinical specimens including pediatric and adult sera, sputum and middle ear fluids. Thereby, we relied upon these latter four peptides for our subsequent biosensor-based epitope-mapping efforts.

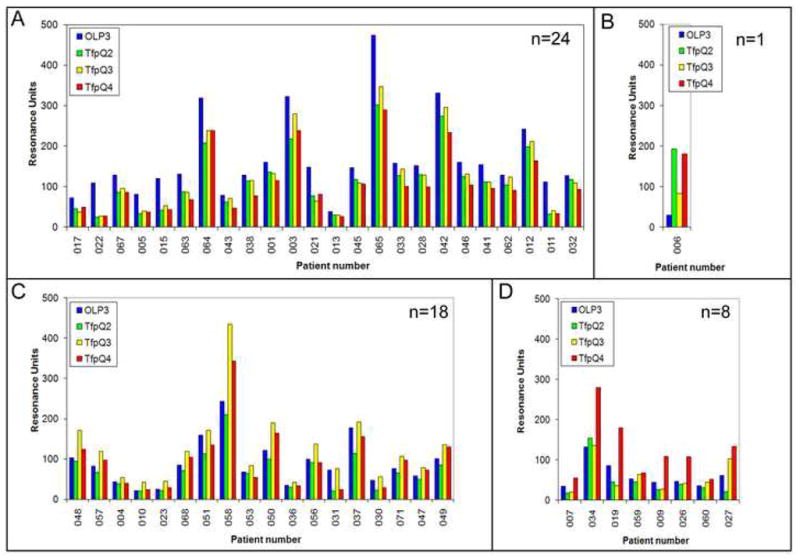

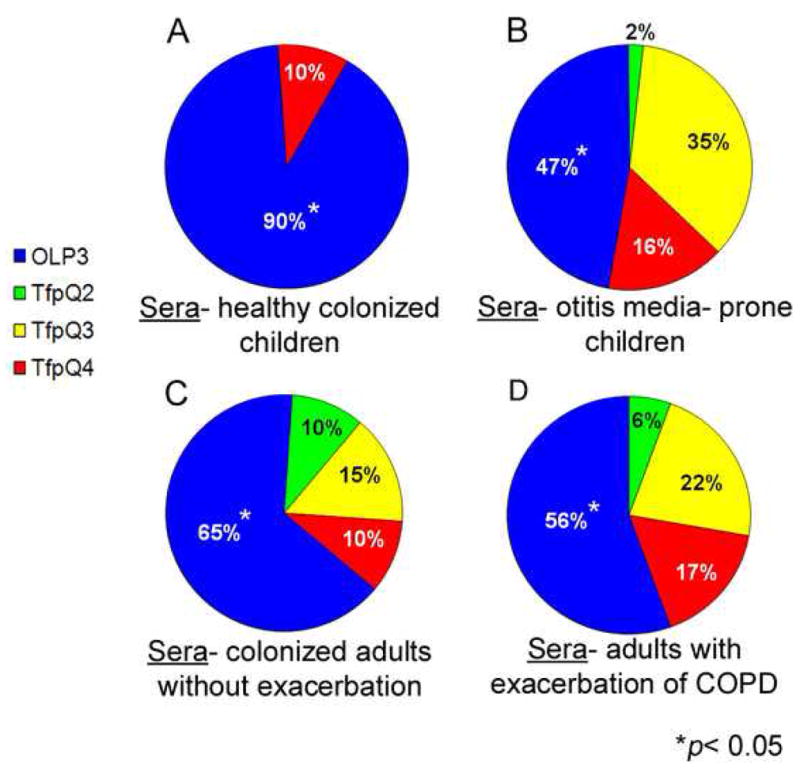

As stated in Methods, due to variability amongst patients in terms of relative overall antigen-specific antibody levels within clinical specimens, biosensor-generated data (in RU or response units) obtained from each patient group/specimen type were clustered based upon to which of the four peptides they showed greatest overall recognition (regardless of the overall magnitude of that response). An example dataset is shown in Fig. 2, wherein serum samples from a total of 51 otitis media prone children were assayed by biosensor against the peptides OLP3, TfpQ2, TfpQ3 and TfpQ4. Twenty-four of these serum samples (47%) showed greatest overall recognition of OLP3 (Panel A, blue bars); one of these serum samples (2%) showed greatest overall recognition of TfpQ2 (Panel B, green bars); eighteen of these serum samples (35%) showed greatest overall recognition of TfpQ3 (Panel C, yellow bars), and eight serum samples (16%) showed greatest overall recognition of TfpQ4 (Panel D, red bars). These data are summarized as a pie chart (see Fig. 3, Panel B). In addition to these data, we performed a similar analysis using sera recovered from healthy, colonized children; sera recovered colonized adults who were not experiencing an exacerbation of COPD; and sera from adults who were experiencing an exacerbation of COPD due to NTHI. Compiled data obtained via the analysis of these four serum sample sets are shown in Fig. 3 and discussed in greater detail below.

Figure 2.

Biosensor data generated by assay of serum samples recovered from 51 OM prone children at the time of tube insertion for chronic and/or recurrent OM against four synthetic peptides designed to mimic the quartiles of the PilA protein that comprises NTHI type IV pili. From N- to C-terminus, these four peptides are called: OLP3, TfpQ2, TfpQ3 and TfpQ4. Reactivity to OLP3 is always shown via blue bars; to TfpQ2 by green bars; to TfpQ3 by yellow bars and to TfpQ4 by red bars. Panel A depicts biosensor data (in RU values) for 24 OM prone children whose sera showed greatest reactivity with OLP3. Panel B depicts biosensor data for 1 child whose serum showed greatest reactivity with TfpQ2. Panel C depicts biosensor data for 18 children whose sera showed greatest reactivity with TfpQ3. Panel D depicts biosensor data for 8 children whose sera showed greatest reactivity with TfpQ4.

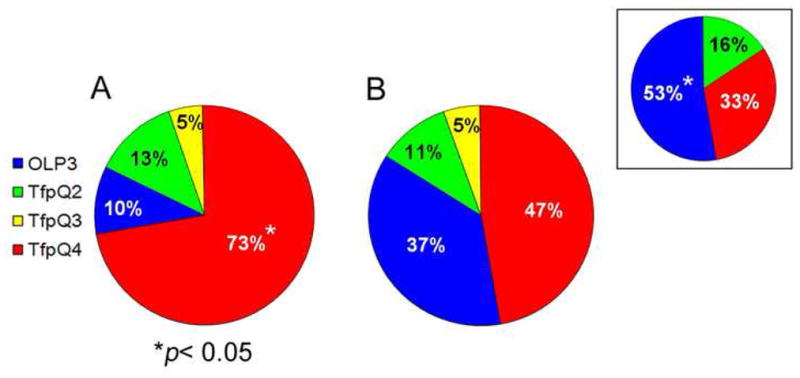

Figure 3.

(A) Of 21 serum samples from healthy children, 19 (90%) demonstrated overall greatest recognition of OLP3, the N-terminal-most peptide (p < 0.05) with less recognition of other peptides. (B) Forty-seven percent of 51 serum samples recovered from OM-prone children demonstrated greatest overall recognition of OLP3 (p < 0.05). Of those serum samples that showed greatest overall recognition of OLP3, 54% had culturable NTHI from their nasopharynges and/or middle ear effusions at the time of surgery. Although the majority of sera from OM-prone children showed greatest overall reactivity to the N-terminal-most peptide, the percentage of sera that showed reactivity toward other epitopes increased notably over that seen for healthy children. (C) Of 40 adult serum samples recovered from COPD patients who were not experiencing an exacerbation, 26 (65%) showed overall greatest recognition of OLP3, the N-terminal-most peptide (p < 0.05) and less recognition of C-terminal peptides. (D) Ten of 18 serum samples (56%) recovered from adults who were experiencing an exacerbation of COPD due to NTHI showed overall greatest recognition of OLP3, the N-terminal-most peptide (p < 0.05), however as seen with serum samples from OM prone children, immune recognition of other epitopes increased notably compared to sera that were not associated with an exacerbation.

Whereas the majority of sera from healthy children (90%) showed greatest overall recognition of the N-terminal-most PilA-derived peptide (OLP3) (Fig. 3A, blue quadrant, p < 0.05), sera from otitis prone children demonstrated more mixed immunoreactivity wherein mid-and C-terminal peptides were also recognized (Fig. 3B). Like healthy children, sera from the majority of COPD patients who were not experiencing an exacerbation, yet were colonized with NTHI (65%), showed greatest overall recognition of OLP3 (the N-terminal-most peptide) (Fig. 3C, blue quadrant, p < 0.05). Similar to sera from otitis prone children however, sera from COPD patients who had experienced a recent exacerbation due to NTHI showed a more mixed immune-responsiveness to the PilA-derived peptides, now recognizing mid and C-terminal regions as well (Fig. 3D).

In terms of additional detail, overall there was an approximately 5-fold greater response to the peptides OLP3 and TfpQ4 by antibody in serum recovered from OM prone children compared to healthy children. For example, in terms of reactivity to the N-terminal most peptide OLP3, serum from OM prone children who showed the greatest reactivity to this peptide (n=24), the mean RU value obtained was 167.5 ± 100.7 RU whereas for healthy children who similarly demonstrated greatest reactivity to OLP3 (n=45), their sera yielded a mean RU value of 31.2 ± 13.8. Similarly for those OM prone children who demonstrated greatest overall recognition of the N-terminal most peptide TfpQ4 (n=8), the mean RU value obtained by biosensor was 122.4 ± 76.5 RU. For healthy children who also demonstrated greatest overall reactivity with TfpQ4, this value was 25.0 ± 12.7 RU. In terms of additional detail for our adult patient samples, more exacerbations/year was associated with a greater level of antibody in any COPD patient sample (p = 0.007) and there was more antibody in samples from COPD patients who had recently experienced an exacerbation than those patients who had not (p = 0.03).

Use of epitope mapping data derived from serum samples to design chimV3

The above described epitope mapping data suggested to us that the N-terminus of rsPilA (represented by OLP3, see blue quadrant in Fig. 3) was recognized as an immunodominant region of the Tfp pilin protein during colonization of the nasopharynx by NTHI. Thereby, we constructed chimV3 wherein the 24-mer B-cell epitope derived from the OMP P5-homologous adhesin protein of NTHI was positioned at the C-terminus of rsPilA (see Fig. 1E). Whereas chimV3 (as all recombinant immunogens used in this study) was initially expressed as a His-tagged recombinant chimeric protein, the His tag was removed prior to immunization of chinchillas for use in the passive transfer-superinfection model, as described below.

Immunogenicity of rsPilA and chimV3

Prior to passive transfer to juvenile chinchilla cohorts, the polyclonal antiserum pools generated against rsPilA, chimV3, LB1 or LB1(1) in adult chinchillas were tested for specificity via Western blot (data not shown), and for reciprocal titer via ELISA (Table 2). As shown, all immunogens used were immunogenic in the chinchilla host when delivered with the adjuvant MPL.

Table 2.

Reciprocal geometric mean titers of adult chinchilla serum pools generated for delivery to juvenile chinchillas by passive transfer.

| Serum pool | Reciprocal geometric titer to immunogen delivered | |

|---|---|---|

| Study A | anti-LB1/MPL | 8063 |

| anti-LB1(1)/MPL | 6400 | |

| anti-rsPilA/MPL | 10,763 | |

| anti-chimV3/MPL | 6400 | |

| anti-MPL | 1008 | |

| Study B | Anti-LB1/AS04 | 32,000 |

| anti-rsPilA/AS04 | 16,000 | |

| anti-chimV4/AS04 | 45,300 | |

| anti-AS04* | 1680 | |

MPL plus aluminum hydroxide

Assessment of relative efficacy of rsPilA and chimV3 as vaccine candidates via the use of the chinchilla passive transfer, viral-bacterial superinfection model

Study A

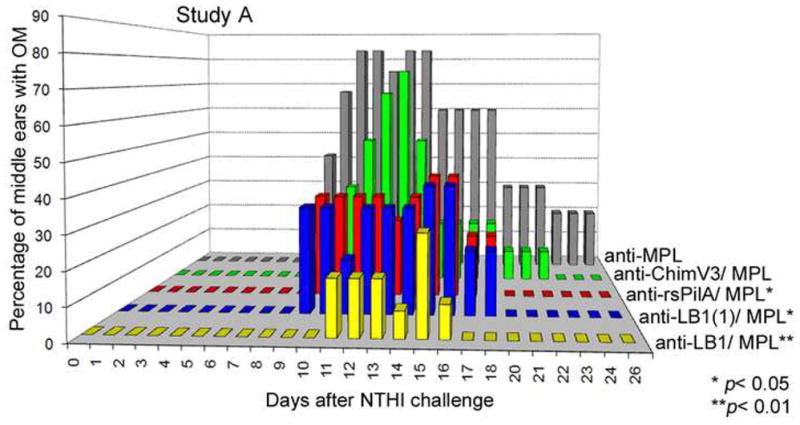

As previously shown, passive transfer of antiserum directed against the 40-mer LB1 when delivered with MPL (used here as a positive control) was highly efficacious in this chinchilla model with 89% of ears never developing OM, and a 48% overall protective efficacy conferred (p < 0.01; Fig. 4, yellow bars) when compared to the cohort that received anti-MPL serum as a negative control (Fig. 4, grey bars). Anti-LB1(1), the 24-mer B-cell epitope of the OMP P5 adhesin, when delivered with MPL, induced the formation of antibodies that conferred protection to 68% of ears that never developed OM. Overall protective efficacy in the cohort that received anti-LB1(1) was 37%, which was also statistically significant (p < 0.05; Fig. 4, blue bars). Anti-rsPilA + MPL conferred protection to 65% of ears for an overall protective efficacy of 35% (p < 0.05; Fig. 4, red bars). When delivered with MPL, antiserum directed against chim-V3 induced the formation of antibodies that provided protection from development of OM to 53% of ears, for a 28% overall protective efficacy (Fig. 4, green bars) compared to the negative control cohort. This latter outcome was not statistically significant.

Figure 4.

Relative protection against ascending NTHI-induced OM afforded by passive transfer of immune serum pools. Relative percentage of chinchilla middle ears with OM in Study A as determined by video otoscopy and tympanometry over time. The greatest protection against ascending OM was conferred by delivery of antiserum against the known effective immunogen, LB1 when admixed with MPL (p< 0.01; yellow bars). The cohort that received anti-MPL served as the negative control and as expected, this cohort showed the greatest incidence of OM (grey bars). All other cohorts showed varying degrees of protection from NTHI-induced OM, with anti-chimV3 (green bars) being notably less protective than was delivery of either anti-LB1(1) (blue bars) or anti-rsPilA (red bars). The protection conferred by immune serum pools directed at either LB1 or rsPilA was statistically significant (p < 0.05), whereas that conferred by delivery of anti-chimV3 was not.

Whereas the chinchilla model may not be sensitive enough to demonstrate and additive effect when two epitopes from a human-restricted microorganism are combined, anti-chimV3 was notably less protective than its two component parts [i.e. either anti-LB1(1) or anti-rsPilA]. This outcome suggested to us that combining rsPilA with a protective B-cell epitope derived from the OMP P5 adhesin by presenting LB1(1) at the C-terminus of rsPilA (see Fig. 1E) was not an ideal configuration. Moreover, results obtained in Study A suggested that perhaps both the C-terminus of rsPilA and the N-terminus of LB1(1) were important protective immune epitopes of their respective adhesin proteins, and would perhaps function more optimally when each was freely accessible to the host immune system. This confounding factor was highly likely given that the configuration of chimV3 resulted in the potential masking of both the N-terminus of LB1(1) and the C-terminus of rsPilA.

Immunoreactivity of local pediatric (middle ear fluids) and adult (sputum) samples with synthetic peptides derived from PilA

Continued evaluation of our clinical specimen collection supported our hypothesis that the C-terminus of PilA was perhaps an immunoprotective epitope. In addition to results obtained with serum samples from OM prone children and adults experiencing an exacerbation of COPD, as discussed above, when we expanded our biosensor analysis to now assess the immunoreactivity of local specimens recovered from these two patient populations (i.e. middle ear fluids and sputum supernatants), the immunodominant nature of the C-terminus of PilA became apparent. As shown in Fig. 5A, the majority of middle ear fluid specimens from otitis media prone children (73%) showed greatest overall recognition of the C-terminal-most peptide (TfpQ4) (red quadrant, p < 0.05). Although not as remarkable as the shift in response seen when middle ear fluids from otitis prone children were assayed, the majority of sputa supernatants collected from COPD patients who had experienced a recent exacerbation (47%) also showed increased recognition of the C-terminal-most PilA peptide (TfpQ4) (Fig. 5B, red quadrant). This shift in reactivity towards the C-terminal most PilA peptide is evident when post-exacerbation sputa data are compared to results obtained using pre-exacerbation sputa recovered from this patient population (see inset of Fig. 5B), wherein reactivity to TfpQ4 (red quadrant in inset) was 33% compared to 47% in post-exacerbation sputa. These latter data suggested that, like the local immune response in the middle ears of otitis prone children, the lower airway of COPD patients responded independently of the serum response during an exacerbation. Moreover, in each niche, regardless of whether it was the uppermost (middle ear) or lower reaches of the airway, the serum response was clearly not driving the immune response measured when local specimens (middle ear fluids and sputum supernatants) were assayed.

Figure 5.

(A) Twenty-nine of 40 middle ear effusions (73%) showed overall greatest recognition of TfpQ4, the C-terminal-most PilA-derived peptide (p < 0.05). Of 29 OM-prone children whose middle ear effusions showed greatest overall recognition of TfpQ4, 19 (66%) had culturable NTHI in their nasopharynges and/or middle ear effusions at the time of surgery for tympanostomy tube placement. (B) Post NTHI-induced exacerbation of COPD sputum samples showed greatest recognition of TfpQ4 (47%), the C-terminal most peptide. Compare results in Panel B to those obtained when pre-exacerbation sputa recovered from these patients were also assayed by biosensor (see inset in Panel B) and wherein sputa obtained pre-exacerbation reacted to significantly greater to the N-terminal most peptide OLP3 (p < 0.05).

Use of epitope mapping data derived from local specimens to design chimV4

Whereas both healthy, colonized children and non-exacerbation experiencing, colonized adults favored recognition of the N-terminus of the Tfp subunit protein (e.g. reactivity with the peptide OLP3), repeated invasion of either the middle ear of children or the airways of adults with COPD induced both broader serum mediated reactivity with the PilA quartile mapping peptides, as well as a local immune response in the middle ear or lung that favored recognition of the C-terminal most peptide (e.g. reactivity with the peptide TfpQ4). To speculate as to what these findings might mean collectively, since humans are typically colonized early and throughout life with NTHI, we reasoned that recognition of the N-terminus of PilA did not likely result in eradication of this microbe from its NP niche. Conversely, whereas despite recurrent disease in both OM prone children and adults with COPD, there were intermittent periods during which the host immune response did indeed successfully eradicate NTHI from either the middle ear or the lower airway in these populations, and thus immune recognition of the C-terminus of PilA (as observed when middle ear fluids and sputum were assayed) might be more favorable to eradication of NTHI.

Thereby, based on both the lack of protective efficacy observed when antiserum directed against chimV3 was delivered to juvenile chinchillas, as discussed above, combined with biosensor data obtained when local airway specimens were evaluated for reactivity with PilA quartile peptides, we designed a new chimeric recombinant vaccine candidate (chimV4) wherein the 24-mer LB1(1) peptide of the OMP P5 adhesin was now positioned at the truncated N-terminus of rsPilA. This configuration was designed to allow for immune recognition of both the N-terminus of LB1(1), as well as the C-terminus of rsPilA. If optimally configured, our goal remained to develop a single, small molecular mass immunogen that could induce the formation of antibodies that could confer protection against NTHI-induced OM by targeting both the OMP P5 adhesin and the Tfp of this microbe.

Immunogenicity of rsPilA and chimV4

In order to evaluate the relative protective efficacy of chimV4 in the chinchilla juvenile viral-bacterial superinfection model, we first generated immune serum pools in adult chinchillas as described above. Antiserum pools were evaluated by both Western blot and ELISA prior to passive transfer to juvenile chinchilla cohorts established as described for Study B (Table 2).

Assessment of relative efficacy of rsPilA and chimV4 as vaccine candidates via the use of the chinchilla passive transfer, viral-bacterial superinfection model

Study B

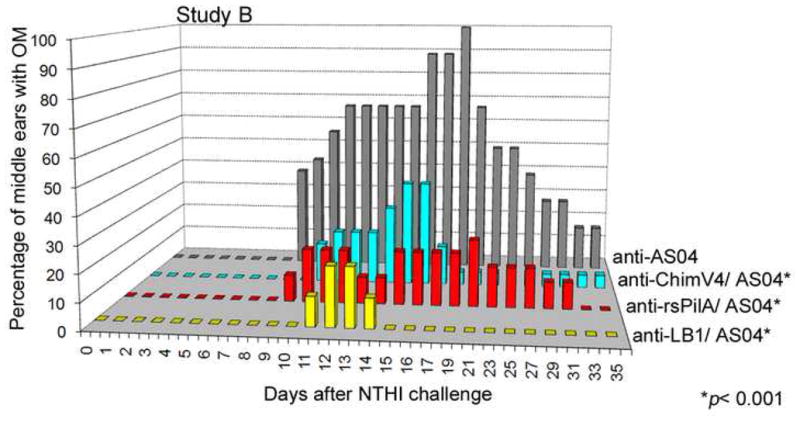

Due to the limited efficacy of chimV3, we conducted a second study, wherein juvenile chinchillas with an existing upper respiratory tract infection (and accompanying Eustachian tube dysfunction), were given antiserum directed against either: 1) adjuvant only (AS04, negative control cohort); 2) rsPilA + AS04; 3) chimV4 + AS04; or 4) LB1+AS04 (positive control cohort). The positive cohort that received anti-LB1 + AS04 serum was significantly protected against ascending OM due to NTHI (78% of ears did not develop OM, 52% overall protective efficacy; Fig. 6, yellow bars) when compared to the cohort that received anti-adjuvant only serum (Fig. 6, gray bars). Anti-rsPilA+AS04 again induced the formation of highly protective antiserum, conferring protection against OM to 65% of ears for an overall protective efficacy of 42%, which was statistically significant (p < 0.001; Fig. 6, red bars).

Figure 6.

Relative percentage of middle ears with OM in Study B. The greatest incidence of OM was observed in the negative control cohort, which received anti-adjuvant serum (grey bars). In contrast, the greatest protection against the development of experimental NTHI-induced OM was achieved in the cohort administered antiserum against LB1 + AS04 (p< 0.001; yellow bars), as expected since this cohort served as the positive control. Further, significant protection against ascending NTHI-induced OM was conferred by receipt of either anti-rsPilA (p< 0.001; red bars) or anti-chimV4 serum pools (p< 0.001; bluegreen bars).

Lastly, anti-chimV4+AS04, induced the formation of antiserum that conferred protection to 60% of ears for a 43% overall protection, (p < 0.001) (Fig. 6, aqua bars). There was no statistically significant difference noted between the cohorts that received either anti-chimV4 or anti-rsPilA serum pools, however as mentioned above, this chinchilla model of experimental OM may not be sensitive enough to detect an additive effect. An alternative explanation is that placement of the LB1(1) epitope at the N-terminus of rsPilA does not interfere with the efficacy of rsPilA as an immunogen. However given our ability to detect antibody to the LB1(1) epitope of chimV4 and the already demonstrated protective nature of antibodies directed against this epitope of OMP P5 [3, 4], it would seem counterintuitive to conclude that these antibodies did not contribute to the demonstrated protective efficacy of chimV4.

Nevertheless, when one compares the relative kinetics of experimental disease in the cohort that received antiserum directed against chimV3 (Fig. 4, green bars) to that observed in those juvenile animals that received anti-chimV4 (Fig. 6, aqua bars), it was evident that chimV4 was the more optimally configured of the two chimeric recombinant immunogens tested here.

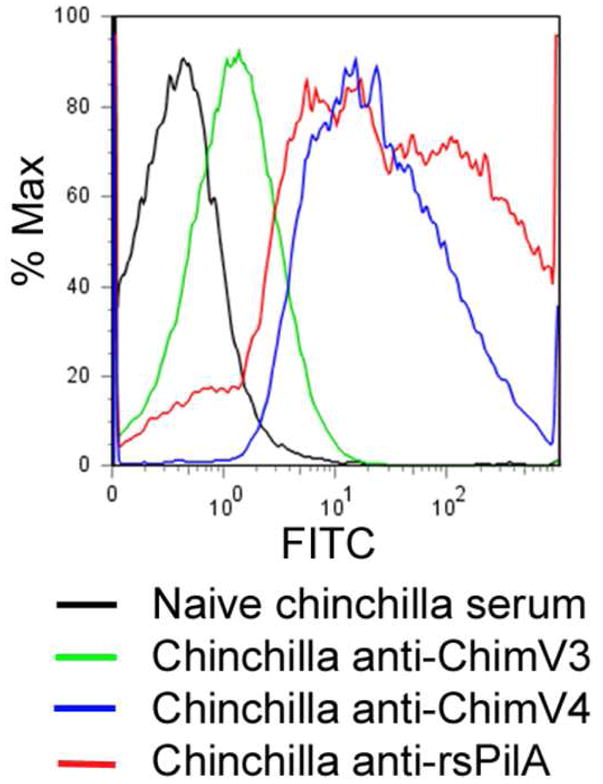

Initial investigation of potential mechanisms that underlie the demonstrated increased protective efficacy of chimV4 over chimV3

Anti-chimV3, anti-chimV4, and anti-rsPilA [all of which were used at an equivalent reciprocal titer of ~5,000–10,000 against the immunogen used to generate the antiserum pool] were tested by FACS analysis using whole NTHI that had been grown under conditions shown to induce expression of pilA [13] to determine their relative ability to label native Tfp expressed by NTHI strain #86-028NP. As shown in Fig. 7, NTHI that had been incubated with chinchilla anti-rsPilA demonstrated a marked shift in fluorescence (red plot, MFI 23.5) compared to those bacteria that had been incubated with naïve serum (black plot). Further, the broadness of the histogram obtained when NTHI was incubated with chinchilla anti-rsPilA suggested that there was likely variation in the relative expression of Tfp amongst individual bacterial cells within the culture. Whereas antiserum to both chimV3 and chimV4 recognized whole NTHI (green and blue plots, respectively), and by inference, the native Tfp expressed by these bacteria, significantly greater than did naive chinchilla serum, the bacterial population incubated with anti-chimV4 was nonetheless ~21-times more fluorescent (MFI = 23.0) than NTHI incubated with anti-chimV3 (MFI = 1.09) This latter observation suggested that placement of the LB1(1) epitope at the N-terminus of rsPilA (as opposed to the C-terminus) likely resulted in the formation of antibodies with a greater overall ability to recognize Tfp in their native conformation, as expressed on the bacterial surface.

Figure 7.

Flow cytometry histograms which depict the relative ability of naïve and immune chinchilla serum pools to recognize native Tfp expressed by viable NTHI. Relative to naive chinchilla serum (black histogram), histograms obtained with NTHI (grown under conditions known to promote expression of pilA) were incubated with either chinchilla anti-chimV3 serum (green histogram), chinchilla anti-chimV4 serum (blue histogram) or chinchilla anti-rsPilA serum (red histogram) demonstrated a markedly greater fluorescent population of cells and suggested recognition of native Tfp as expressed by NTHI by each of these immune serum pools. However, incubation of NTHI with chinchilla anti-chimV4 or anti-rsPilA resulted in a population of NTHI with mean fluorescent intensity that was 21- to 57-times greater, respectively, compared to that obtained when NTHI were incubated with an anti-chimV3 serum pool. These data suggested that the configuration of the immunogen chimV4 allowed for greater recognition of the Tfp subunit protein, PilA, than did the configuration of chimV3.

Importantly, the configuration of chimV4 appeared to allow for greater recognition of both the LB1(1) epitope and the C-terminal fragment of PilA than did chimV3. Support for this latter assertion was provided by biosensor analysis wherein rsPilA, LB1(1) and TfpQ4 were bound to a sensor chip surface as we have previously reported [25–27], and assayed for relative ability to bind antibodies within the chinchilla anti-chimV3, anti-chimV4 and anti-rsPilA serum pools [again, each antiserum pool used was at an equivalent reciprocal titer of ~5,000–10,000 against the immunogen delivered]. Whereas binding to rsPilA was equivalent for both anti-chimV3 and anti-chimV4 sera (403 vs. 398.3 RU, respectively), anti-chimV4 demonstrated an approximately 2-fold greater ability to recognize the B-cell epitope of OMP P5 [i.e. LB1(1)] than did anti-chimV3 (276.5 RU vs. 152.1 RU, respectively). Moreover, when assayed for relative ability to recognize TfpQ4 (the C-terminal peptide of PilA), anti-chimV4 serum generated an RU value of 60.8, anti-rsPilA was equivalent, generating an RU = 64.7; whereas anti-chimV3 serum yielded an RU value of 25.9. For comparison, RU values obtained when naive chinchilla serum was used, were 13.4 against TfpQ4 and 19.1 against LB1(1).

Discussion

Nontypeable H. influenzae is a predominant bacterial pathogen of the human upper and lower respiratory tracts. This highly heterogeneous family of microbes is a prevalent causative agent of chronic OM, recurrent OM, and OM with effusion in the pediatric population, in addition to causing exacerbations of COPD in the adult population [1]. While not considered virulent in the classic sense, due to the fact that NTHI exists primarily as a benign member of the normal commensal nasopharyngeal flora, this microbe can nonetheless behave as an opportunistic pathogen under certain predisposing conditions. Most typically these conditions involve compromise of airway protective functions by a preceding or concurrent viral upper respiratory tract infection [37], which allows NTHI to grow to increased bacterial loads in the nasopharynx [38–44], and subsequently gain access to the temporarily poorly defended middle ear or lower airways.

In our attempts over the years to design vaccine candidates for the prevention of NTHI-induced diseases of the respiratory tract, we have primarily focused our efforts on two of several adhesins expressed by this group of microorganisms – the OMP P5-homologous adhesin and Tfp. Here, we elected to combine epitopes from these two NTHI adhesins and thus designed recombinant chimeric peptide immunogens comprised of an N-terminally truncated recombinant PilA that has been modified to also incorporate a slightly longer variant of the B-cell epitope from the OMP P5-homologous adhesin [LB1(1)] at either its N- or C-terminus. As such, two chimeric immunogens (chimV3 and chimV4) were generated based on the use of rsPilA as both an immunizing co-partner as well as an alternative carrier peptide for the protective B-cell epitope derived from OMP P5 (replacing the former measles virus fusion protein-derived T-cell promiscuous epitope). Thus, rsPilA protein that was modified to present a 24-mer B-cell epitope of the OMP P5-homologous adhesin at its C-terminus, resulted in a chimeric immunogen comprised of portions of two distinct NTHI adhesins, that was called ‘chim-V3’. Upon parenteral immunization with the adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A, chimV3 induced antibodies that recognized the 40-mer peptide LB1, the B-cell epitope contained within LB1 and recombinant soluble PilA protein, as well as the chimeric immunogen itself. Nonetheless, disappointingly chimV3 did not confer protection against the development of experimental NTHI-induced OM in a chinchilla model system, and in fact was less protective than either rsPilA or LB1(1) which suggested that combination of the P5 and PilA epitopes in this configuration was not optimal. Whereas we have published multiple studies describing the protective efficacy of LB1 against experimental NTHI-induced OM in chinchilla models [3–6, 24–27], the present study represents the first use of the 24-mer peptide LB1(1) as a non-chimeric immunogen, as well as the first reported use of Tfp PilA-derived immunogens.

The failure of chimV3 in a chinchilla model of ascending NTHI-induce OM combined with ongoing epitope mapping data obtained via the use of both pediatric and adult patient local airway specimens which showed that the C-terminal domain of PilA was immunodominant when middle ear fluids and sputum supernatants were assayed, suggested to us a better design option that would potentially improve the efficacy of chimV3. Thus, we designed and tested the immunogen chimV4. In chimV4, the 24-mer OMP P5 adhesin-derived B-cell epitope is presented at the N-terminus of the rsPilA protein, leaving the C-terminus of this latter protein freely accessible for immune recognition. Unlike anti-chimV3, anti-chimV4 serum was highly protective in the chinchilla model and performed as well as anti-rsPilA. These data, combined with additional biosensor and flow cytometry analysis suggested that placement of the OMP P5-derived B-cell epitope LB1(1) at the N-terminus of rsPilA (i.e. chimV4) was more optimal than presenting this B-cell epitope at the C-terminus of rsPilA (i.e. chimV3).

Whereas both rsPilA and chimV4 are being developed further, chimV4 is of great potential interest as it was designed to have the added benefit of including epitopes derived from two NTHI adhesins (OMP P5 and Tfp), each of which have been shown to confer key biological functions to NTHI and each further shown to be required for pathogenesis [12, 13, 46, 47], in a single immunogen. In addition, since chimV4 does not contain the T-cell promiscuous measles virus fusion protein epitope included in LB1, this immunogen has enhanced attractiveness for further development for the prevention of NTHI-induced OM in the pediatric population. The 40-mer LB1 remains extremely attractive for older patient populations and/or other diseases of the respiratory tract due to its longstanding protective efficacy in pre-clinical trials [12,13,17,38]. Thereby, we continue to develop LB1, rsPilA, and chimV4 as vaccine candidates (for use via parenteral and non-invasive routes) for NTHI-induced diseases of the upper and lower respiratory tract.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NIH/NIAID N01 AI-30040, NIH/NIDCD R01 DC-007464, and NIH/NIDCD R01 DC-003915 to L.O.B.; R01 AI19641 from NIH/NIAID and Dept. of Veterans Affairs to T.F.M.; and from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart Belgium to L.O.B. for the chinchilla study to assess efficacy of chimV4. We thank Grace Wentzel, Shelli Farley and their colleagues in both Clinical Research Services at Nationwide Children’s Hospital & it’s Close to Home Centers for recovery of pediatric specimens. We are grateful to Dr. William Ray for 3D computer modeling of rsPilA; to Dr. Robert S. Munson, Jr. for multiple contributions to the design and generation of chimV3 and chimV4 as well as critical review of our manuscript; to Erin Tracy for the expression of recombinant immunogens used here, and to Pravin T. P. Kaumaya and his laboratory for synthesis and purification of PilA-derived peptides. Most importantly, we express our gratitude to the patients and their families for allowing us to use these valuable clinical specimens in our efforts to better understand the pathogenesis of diseases of the respiratory tract due to NTHI and develop novel ways to treat or prevent them.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Murphy TF. Respiratory infections caused by non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16(2):129–34. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200304000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.St Geme JW., 3rd Molecular and cellular determinants of non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae adherence and invasion. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4(4):191–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakaletz LO, Leake ER, Billy JM, Kaumaya PT. Relative immunogenicity and efficacy of two synthetic chimeric peptides of fimbrin as vaccinogens against nasopharyngeal colonization by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in the chinchilla. Vaccine. 1997;15(9):955–61. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyd JM, Cripps AW, Novotny LA, Bakaletz LO. Efficacy of the 26-kilodalton outer membrane protein and two P5 fimbrin-derived immunogens to induce clearance of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae from the rat middle ear and lungs as well as from the chinchilla middle ear and nasopharynx. Infect Immun. 2003;71(8):4691–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.8.4691-4699.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakaletz LO, Kennedy BJ, Novotny LA, Duquesne G, Cohen J, Lobet Y. Protection against development of otitis media induced by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae by both active and passive immunization in a chinchilla model of virus-bacterium superinfection. Infect Immun. 1999;67(6):2746–62. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2746-2762.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy BJ, Novotny LA, Jurcisek JA, Lobet Y, Bakaletz LO. Passive transfer of antiserum specific for immunogens derived from a nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae adhesin and lipoprotein D prevents otitis media after heterologous challenge. Infect Immun. 2000;68(5):2756–65. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2756-2765.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luke NR, Howlett AJ, Shao J, Campagnari AA. Expression of type IV pili by Moraxella catarrhalis is essential for natural competence and is affected by iron limitation. Infect Immun. 2004;72(11):6262–70. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6262-6270.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merz AJ, Enns CA, So M. Type IV pili of pathogenic Neisseriae elicit cortical plaque formation in epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32(6):1316–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plant L, Jonsson AB. Contacting the host: insights and implications of pathogenic Neisseria cell interactions. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35(9):608–13. doi: 10.1080/00365540310016349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bieber D, Ramer SW, Wu CY, Murray WJ, Tobe T, Fernandez R, et al. Type IV pili, transient bacterial aggregates, and virulence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science. 1998;280(5372):2114–8. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luke NR, Jurcisek JA, Bakaletz LO, Campagnari AA. Contribution of Moraxella catarrhalis type IV pili to nasopharyngeal colonization and biofilm formation. Infect Immun. 2007;75(12):5559–64. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00946-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakaletz LO, Baker BD, Jurcisek JA, Harrison A, Novotny LA, Bookwalter JE, et al. Demonstration of type IV pilus expression and a twitching phenotype by Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 2005;73(3):1635–43. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1635-1643.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jurcisek JA, Bookwalter JE, Baker BD, Fernandez S, Novotny LA, Munson RS, Jr, et al. The PilA protein of non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae plays a role in biofilm formation, adherence to epithelial cells and colonization of the mammalian upper respiratory tract. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65(5):1288–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jurcisek JA, Bakaletz LO. Biofilms formed by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in vivo contain both double-stranded DNA and type IV pilin protein. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(10):3868–75. doi: 10.1128/JB.01935-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jurcisek JA, Grieves JL, Bakaletz LO. Resolution of experimental NTHI-induced OM and eradication of pre-existing middle ear biofilms in chinchillas immunized with a type IV pilus protein-based vaccine candidate. 1st International Workshop on Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis; Rotterdam, The Netherlands. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kao DJ, Churchill ME, Irvin RT, Hodges RS. Animal protection and structural studies of a consensus sequence vaccine targeting the receptor binding domain of the type IV pilus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Mol Biol. 2007;374(2):426–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandes PJ, Guo Q, Waag DM, Donnenberg MS. The type IV pilin of Burkholderia mallei is highly immunogenic but fails to protect against lethal aerosol challenge in a murine model. Infect Immun. 2007;75(6):3027–32. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00150-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boslego JW, Tramont EC, Chung RC, McChesney DG, Ciak J, Sadoff JC, et al. Efficacy trial of a parenteral gonococcal pilus vaccine in men. Vaccine. 1991;9(3):154–62. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoolnik GK, Tai JY, Gotschlich EC. A pilus peptide vaccine for the prevention of gonorrhea. Prog Allergy. 1983;33:314–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novotny LA, Jurcisek JA, Godfroid F, Poolman JT, Denoel PA, Bakaletz LO. Passive immunization with human anti-protein D antibodies induced by polysaccharide protein D conjugates protects chinchillas against otitis media after intranasal challenge with Haemophilus influenzae. Vaccine. 2006;24(22):4804–11. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamanaka N, Faden H. Antibody response to outer membrane protein of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in otitis-prone children. J Pediatr. 1993;122(2):212–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(06)80115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sethi S, Evans N, Grant BJ, Murphy TF. New strains of bacteria and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(7):465–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sethi S, Wrona C, Grant BJ, Murphy TF. Strain-specific immune response to Haemophilus influenzae in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(4):448–53. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1181OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakaletz LO. Peptide and recombinant antigens for protection against bacterial middle ear infection. Vaccine. 2001;19(17–19):2323–8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00522-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novotny LA, Jurcisek JA, Pichichero ME, Bakaletz LO. Epitope mapping of the outer membrane protein P5-homologous fimbrin adhesin of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 2000;68(4):2119–28. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2119-2128.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novotny LA, Pichichero ME, Denoel PA, Neyt C, Vanderschrick S, Dequesne G, et al. Detection and characterization of pediatric serum antibody to the OMP P5-homologous adhesin of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae during acute otitis media. Vaccine. 2002;20(29–30):3590–7. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Novotny LA, Bakaletz LO. The fourth surface-exposed region of the outer membrane protein P5-homologous adhesin of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae is an immunodominant but nonprotective decoying epitope. J Immunol. 2003;171(4):1978–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bakaletz LO. Developing animal models for polymicrobial diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(7):552–68. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bakaletz LO, Daniels RL, Lim DJ. Modeling adenovirus type 1-induced otitis media in the chinchilla: effect on ciliary activity and fluid transport function of Eustachian tube mucosal epithelium. J Infect Dis. 1993;168(4):865–72. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.4.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki K, Bakaletz LO. Synergistic effect of adenovirus type 1 and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in a chinchilla model of experimental otitis media. Infect Immun. 1994;62(5):1710–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1710-1718.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyamoto N, Bakaletz LO. Kinetics of the ascension of NTHi from the nasopharynx to the middle ear coincident with adenovirus-induced compromise in the chinchilla. Microb Pathog. 1997;23(2):119–26. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrison A, Dyer DW, Gillaspy A, Ray WC, Mungur R, Carson MB, et al. Genomic sequence of an otitis media isolate of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: comparative study with H. influenzae serotype d, strain KW20. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(13):4627–36. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.13.4627-4636.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giebink GS, Heller KA, Harford ER. Tympanometric configurations and middle ear findings in experimental otitis media. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1982;91(1 Pt 1):20–4. doi: 10.1177/000348948209100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Margolis RH, Hunter LL, Giebink GS. Tympanometric evaluation of middle ear function in children with otitis media. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1994;163:34–8. doi: 10.1177/00034894941030s510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong HH, Weiser JN, James MA, DeMaria TF. Effect of influenza A virus infection on nasopharyngeal colonization and otitis media induced by transparent or opaque phenotype variants of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the chinchilla model. Infect Immun. 2001;69(1):602–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.602-606.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mason KM, Munson RS, Jr, Bakaletz LO. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae gene expression induced in vivo in a chinchilla model of otitis media. Infect Immun. 2003;71(6):3454–62. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3454-3462.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bakaletz LO. Otitis Media. In: Brogden KA, Guthmiller JM, editors. Polymicrobial Diseases. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology Press; 2002. pp. 259–98. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faden H. The microbiologic and immunologic basis for recurrent otitis media in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160(7):407–13. doi: 10.1007/s004310100754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faden H, Duffy L, Wasielewski R, Wolf J, Krystofik D, Tung Y. Relationship between nasopharyngeal colonization and the development of otitis media in children. Tonawanda/Williamsville Pediatrics. J Infect Dis. 1997;175(6):1440–5. doi: 10.1086/516477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faden H, Duffy L, Williams A, Krystofik DA, Wolf J. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal colonization with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in the first 2 years of life. J Infect Dis. 1995;172(1):132–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernstein JM, Faden HF, Dryja DM, Wactawski-Wende J. Micro-ecology of the nasopharyngeal bacterial flora in otitis-prone and non-otitis-prone children. Acta Otolaryngol. 1993;113(1):88–92. doi: 10.3109/00016489309135772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faden H, Waz MJ, Bernstein JM, Brodsky L, Stanievich J, Ogra PL. Nasopharyngeal flora in the first three years of life in normal and otitis-prone children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100(8):612–5. doi: 10.1177/000348949110000802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faden H, Stanievich J, Brodsky L, Bernstein J, Ogra PL. Changes in nasopharyngeal flora during otitis media of childhood. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9(9):623–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGillivary G, Mason KM, Jurcisek JA, Peeples ME, Bakaletz LO. RSV-induced dysregulation of expression of a mucosal β-defensin augments colonization of the upper airway by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Cell Microbiol . 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.462-5822.2009.01339.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Novotny LA, Bakaletz LO. A novel transcutaneous immunization regimen with OMP P5 and type IV pilus-derived immunogens confers protection against nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae-induced otitis media. 6th Extraordinary International Symposium on Recent Advances in Otitis Media; May 6–10, 2009; Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sirakova T, Kolattukudy PE, Murwin D, Billy J, Leake E, Lim D, et al. Role of fimbriae expressed by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in pathogenesis of and protection against otitis media and relatedness of the fimbrin subunit to outer membrane protein A. Infect Immun. 1994;62(5):2002–20. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.2002-2020.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang Z, Nagata N, Molina E, Bakaletz LO, Hawkins H, Patel JA. Fimbria-mediated enhanced attachment of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae to respiratory syncytial virus-infected respiratory epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67(1):187–92. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.187-192.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]