Abstract

Objective(s)

We evaluated changes in characteristics of clients presenting for Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) before and during Care and Treatment Center (CTC) scale-up activities in Moshi, Tanzania between November 2003 and December 2007.

Methods

Consecutive clients were surveyed following pre-test counseling, and rapid HIV antibody testing was performed. Trend tests were used to assess changes in seroprevalence and client characteristics over time. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the contribution of changes in sociodemographic and behavioral risk characteristics, and symptoms, to changes in seroprevalence before and during CTC scale-up.

Results

Data from 4391 first-time VCT clients were analyzed. HIV seroprevalence decreased from 26.2% to 18.9% following the availability of free antiretroviral therapy and expansion of CTCs beyond regional and referral hospitals. Seroprevalence decreased by 27 % for females (p=0.0002) and 34% for males (p =0.0125). Declines in seropositivity coincided with decreases in symptoms among males and females (p<0.0001), and a more favorable distribution of sociodemographic risks among females (p=0.002). No changes in behavioral risk characteristics were observed.

Conclusions

Concurrent with the scale-up of CTCs, HIV seroprevalence and rates of symptoms declined sharply at an established free-standing VCT site in Moshi, Tanzania. If more HIV-infected persons access VCT at sites where antiretrovirals are offered, free-standing VCT sites may become a less cost-effective means for HIV case-finding.

Keywords: Sub-Saharan Africa, antiretroviral therapy, risk factors, HIV seroprevalence, care and treatment

Introduction

Despite substantial advances in HIV diagnostics and therapeutics over the past decade, approximately 2.5 million people were newly infected in the past year, bringing the global count of HIV-infected people to 33.2 million 1. Although many resources have been allocated to address the epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa, this region remains disproportionately affected, accounting for 68% of HIV-infected adults living and 76% of adult and child deaths from AIDS worldwide 1. Continuing efforts to focus on prevention and treatment remains critical to containing the HIV/AIDS epidemic 2, 3.

Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) has long been seen as an important intervention in sub-Saharan Africa, offering an individualized, client-centered approach that addresses prevention of transmission between partners as well as between mother and child 4. VCT also provides opportunities for early identification of infection 5, allowing for more effective treatment of HIV/AIDS and its co-infections 6, 7, especially as access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) continues to expand 8.

In Tanzania, free access to ART began in September of 2004 under the HIV/AIDS Treatment and Care Plan 2003-2008 9. With a goal of treating 400,000 HIV-infected Tanzanian residents by the year 2008, this plan also emphasized the need to expand VCT services as the primary entry point for care and treatment.

The interaction between prevention efforts and treatment rollout has been highlighted as an important strategy in effectively fighting the HIV epidemic 10, 11. Even in developing countries where access to ART may be limited, it has been postulated that synergistic effects between the two could lead to 29 million fewer infections and 10 million deaths averted, while unsuccessful integration 3 or sole focus on treatment would be insufficient to control the epidemic 12.

Several studies have evaluated the interactions between ART access and VCT, finding more favorable attitudes towards testing 13, expansion of education activities, and changing community attitudes towards HIV and testing 14 after the availability of drugs. In Haiti 15, South Africa 16, and Botswana 17 VCT uptake increased after ART became accessible. However, it has yet to be determined how VCT client characteristics, including risk behaviors, may change following the regional scale-up of access to free care and treatment. Greater access to care and treatment centers (CTCs) might influence the characteristics of populations accessing free-standing VCT centers. Understanding such changes may help shape policy and practice around the optimal means for HIV case-finding and care delivery. Using data from a cohort of clients presenting at an established stand-alone VCT Centre in Moshi, Tanzania, we examined changes in the seropositivity, sociodemographic characteristics, and HIV risk behaviors and symptoms of clients from 2003 through 2007, a time period intersected by the introduction of free ART in September 2004 and the rapid scale-up of multiple CTCs.

Methods

Location and Context

Subjects were recruited from the AIDS Information Centre in downtown Moshi, Tanzania, an established stand-alone VCT site operated by Kikundi cha Wanawake Kilimanjaro Kupambana na UKIMWI (KIWAKKUKI; Women Against AIDS in Kilimanjaro). VCT services have been offered since March of 2003, in conjunction with other services that have been incorporated since the founding of KIWAKKUKI in 1990 such as home-based care, education and outreach, and orphan care and assistance services. Initially each test cost 1000 Tanzanian shillings (US $0.95 at 2003 exchange rates), but testing for clients became free in May 2004. In September 2004 the Tanzanian government began offering access to free ART; hence therapy became available locally at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC), though initially in limited supply. Scale-up of regional HIV CTCs through which patients could receive free antiretroviral therapy progressed rapidly. Data collection for this report began November 21, 2003 and ended December 31, 2007.

Voluntary HIV Counseling and Testing Procedures

All counseling and testing was performed in accordance with guidelines provided by the Tanzanian Ministry of Health National AIDS Control Programme 18. Clients presenting for testing received confidential pre-test counseling including risk assessment and risk reduction planning with a trained counselor, after which informed consent was obtained for clients aged 18 and above. Clients under the age of 18 were tested with a parent's permission but not enrolled in this study. Counselors then administered a structured questionnaire designed to obtain information on sociodemographic characteristics, reasons for testing, past and current sexual behavior, partner relationship status, HIV testing history, potentially HIV-related symptoms (fever, cough, bloody cough, diarrhea, rash, night sweats, genital ulcers, and weight loss), ART knowledge, and planned changes in behavior after testing 19. For marital status specifically, clients were given the option to choose co-habitating, divorced/separated, widowed, married (polygamous or monogamous), or single (including never married, have girlfriend or boyfriend, or engaged). The provision of VCT services was not contingent upon participation in the study.

After pre-test counseling and administration of the questionnaire, a 2mL blood sample was drawn and tested using both Capillus (Trinity Biotech PLC, Bray, County Wicklow, Ireland) and Determine (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) rapid HIV1/2 antibody tests. If the two test results did not match, the blood samples were sent to the referral laboratory at KCMC for confirmatory testing using the ELISA method. For quality control purposes, every 10th sample also underwent repeat testing using the ELISA method at the KCMC laboratory. Clients who tested positive were referred to the zonal hospital HIV clinic for care, offered to join peer support groups and the home-based care program, and encouraged to have sexual partners and children tested. For clients who tested negative, post-test counseling focused on prevention of transmission of HIV and clients were encouraged to return for repeat testing at the time interval recommended by the Ministry of Health. Regular testing of the sexual partner was also emphasized. Clients who screened positive for possible sexually transmitted diseases, domestic violence, and/or tuberculosis were referred to the appropriate care centers.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the KCMC Research Ethics Committee, the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board, and the Tanzanian National Institute of Medical Research (NIMR) National Medical Research Coordinating Committee. All study subjects were provided with Kiswahili versions of the written consent, and only consenting adults enrolled in the study.

Analysis

Data were entered using Epi Info 2002 or Epi Info 3.3 software (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia) or Teleform 9.0 (Cardiff, Visa, California). Data were validated by randomly sampling 10% of the questionnaires, with an acceptable error rate of < 1 error per 5 forms. Data were compiled into one database using JMP 6.0 (SAS Institute, Inc.) and all analyses performed using STATA 10 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Differences in client characteristics by gender were assessed using chi-square and Student's t-tests. Non-parametric trend tests were used to descriptively assess changes in the characteristics of the client population over time. For analyses of changes in seropositivity and correlates of seropositivity, the study period was divided into three time intervals: pre-CTC period (before October 1, 2004); a transitional early CTC period (October 1, 2004 – June 30, 2006); and a CTC scale-up period (July 1, 2006 or later). The early CTC period was defined by the time of free-ART introduction at only the zonal and regional referral hospitals until decentralization to district hospitals and health centers.

Generalized Hausman tests were used to evaluate whether correlates of seropositivity, identified using gender-specific multivariable logistic regression models, differed significantly between the pre-CTC and the CTC scale-up-CTC periods. All models included the following variable domains as covariates: 1) sociodemographic characteristics (age, education, rural versus urban residence, and marital status), 2) behavioral risk (number of lifetime partners, 3 or more lifetime partners), and 3) presence of any HIV-related symptoms and the number of symptoms. All analyses were stratified by gender.

Combined models, stratified by gender and covering the entire study period, were estimated to identify the effects of changes in the client population on rates of seropositivity and to identify the differential effects of changes in the distribution of each of the three explanatory domains: sociodemographic characteristics, behavioral risk characteristics, and symptoms. Parameter estimates from the combined models were used to predict each client's probability of seropositivity. To determine domain-specific contributions to changes in seropositivity, we iteratively analyzed changes in the predicted probabilities over time when holding all characteristics in the respective other domains constant at the sample mean. Time effects were analyzed using linear regression models with predicted probabilities as dependent variables and time as the sole explanatory variable. The time variable was specified in three segments: the pre-CTC period was used as the reference group, the transitional (early CTC) period was described by a spline ranging from October 1, 2004 to June 30, 2006), and the CTC scale-up period was specified as a binary indicator variable. Significance was assessed by a linear combination of the spline and the estimated post-ART parameter. The process was repeated for each domain, separately for males and females.

Results

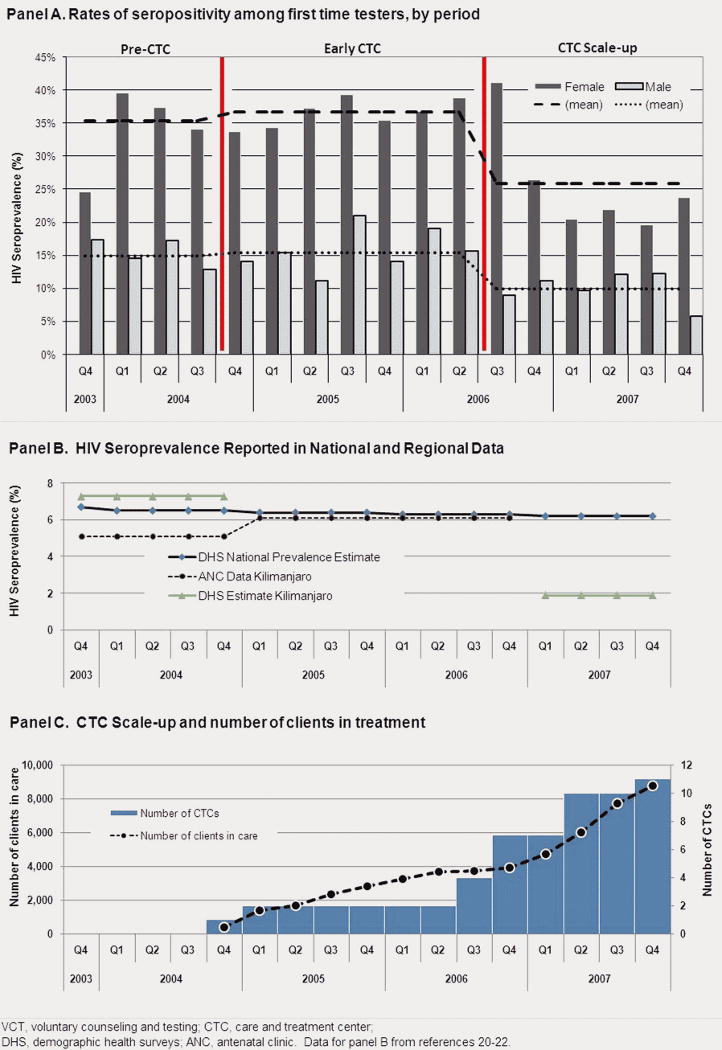

Between November 21, 2003 and December 31, 2007, 8647 consecutive clients presented for VCT services at KIWAKKUKI and, of these, 4,391 (50.8%) were first time testers. Seropositivity rates among first time testers declined significantly in the CTC scale-up period (see Figure 1), with a decrease from 14.9% to 9.9% (p=0.0124) in males and from 35.4% to 25.9% (p=0.0002) in females, compared to the pre-CTC period. For comparison, also shown in Figure 1 are available Kilimanjaro Region-specific antenatal clinic and demographic surveillance data from this time period.20-22 Sociodemographic characteristics, behavioral risk characteristics, and client-reported symptoms in the pre-CTC period and the CTC scale-up period, along with trends across the entire study period, are summarized in Table 1. Age distribution did not change significantly across time. The percent of female clients reporting a primary school education or less decreased significantly (p<0.0001) as did the proportion residing in rural areas for both males and females (p<0.0001).). Significantly more men and women reported that they were divorced/separated during the later time period (p=0.0001 and p=0.0058, respectively), and fewer women reported being widowed (p=0.0090). The proportion of clients reporting 3 or more lifetime sexual partners increased over time from 55.6 to 66.7% for men (p=0.0172) and from 26.4% to 31.4% for women ((p=0.0951). The number of lifetime sexual partners increased significantly for males (p=0.0199), but not for females. Over time, the proportion of clients reporting any of the 8 listed HIV-related symptoms decreased by more than half for men and by more than a third for women (p<0.0001); the mean number of symptoms did not change

Figure 1.

Rates of seropositivity by gender among first-time clients presenting for VCT in Moshi, Tanzania, pre-CTC and during CTC scale-up, 2003-2007 (N=4,391)

Table 1. Client characteristics at a VCT centre in Moshi, Tanzania, pre-CTC and during CTC scale-up, N=4,391.

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pre-CTC | CTC Scale-up | p-value | pre-CTC | CTC Scale-up | p-value | |

| Age | 31.5 | 32.4 | 0.4495 | 33.1 | 32.3 | 0.4757 |

| Primary school education or less | 58.0% | 55.4% | 0.3799 | 81.0% | 68.4% | 0.0000 |

| Rural residence | 59.2% | 44.2% | 0.0000 | 67.5% | 44.6% | 0.0000 |

| Seropositivity | 14.9% | 9.9% | 0.0341 | 35.4% | 25.9% | 0.0001 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Co-habitating | 5.7% | 5.4% | 0.1121 | 8.6% | 8.5% | 0.4180 |

| Divorced/separated | 4.3% | 9.7% | 0.0001 | 10.4% | 14.1% | 0.0058 |

| Widowed | 3.7% | 3.1% | 0.6074 | 20.2% | 11.7% | 0.0090 |

| Married | 25.3% | 23.0% | 0.7021 | 22.6% | 20.8% | 0.1653 |

| Single | 61.1% | 58.8% | 0.5545 | 38.2% | 44.9% | 0.0755 |

| Behavioral risk | ||||||

| 3 or more lifetime partners | 55.6% | 66.7% | 0.0172 | 26.4% | 31.4% | 0.0951 |

| Number of lifetime partners | 4.47 | 5.88 | 0.0199 | 2.30 | 2.31 | 0.6767 |

| Symptoms | ||||||

| Any symptoms | 26.1% | 12.9% | 0.0000 | 35.9% | 22.1% | 0.0000 |

| Number of symptoms 1 | 2.40 | 2.01 | 0.7592 | 2.52 | 2.35 | 0.8848 |

p-value denotes significance of trend among all clients (Nov 2003 - Dec 2007)

mean number of symptoms for clients with any symptoms

Summarized in Table 2 are client reasons for testing during the pre-CTC and CTC scale-up periods with trend tests for all clients across the study period, by gender. Over time, a greater percentage of men and women cited having multiple sexual partners (p<0.0001 for each), suspecting unfaithfulness in their partner (p<0.001 for each), and pre-marital planning (p=0.00167 for males; p=0.0002 for females). Women citing pre-conception planning as a reason for test increased significantly (p=0.0068). Multivariate analysis of correlates of seropositivity from 2003 to 2007 revealed no significant changes over time (Table 3). Among males, receiving less education (odds ratio (OR) 1.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07-2.07, p<0.05), residing in a rural area (OR 1.49, CI 1.07-2.09, p<0.05), cohabitating (OR 5.76, CI 3.49-9.51, p<0.001), being divorced/separated (OR 2.99, CI 1.67-5.34, p<0.001), being widowed (OR 6.43, CI 3.11-13.31, p< 0.001), being married (OR 1.80, CI 1.11-2.90, P<0.05), having more than 3 lifetime sexual partners (OR 1.53, CI 1.04-2.25, p<0.05), and having a higher number of symptoms (OR 1.81, CI 1.50-2.19, p<0.001) were associated with increased risk. Among females, cohabitating (OR 2.73, CI 1.94-3.86, p<0.001), being divorced/separated (OR 2.13, CI 1.50-3.03, p<0.001), being widowed (OR 4.57, CI 3.21-6.49, p<0.001), having more than 3 lifetime sexual partners (OR 1.97, CI 1.55-2.51, p<0.001), having any symptoms (OR 2.07, CI 1.44-2.97, p<0.001), and having a higher number of symptoms (OR 1.76, CI 1.52-2.04, p<0.001) were associated with increased risk.

Table 2. Reasons for testing cited by clients presenting for VCT in Moshi, Tanzania, pre-CTC and during CTC scale-up (% reporting), N=4,391.

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pre-CTC | CTC Scale-up | p-value | pre-CTC | CTC Scale-up | p-value | |

| Personal illness | 17.5% | 13.1% | 0.2195 | 27.2% | 24.1% | 0.1753 |

| Sexual partner ill or died | 5.6% | 6.3% | 0.4827 | 15.4% | 12.4% | 0.1688 |

| Multiple sexual partners | 20.1% | 50.4% | 0.0000 | 5.7% | 26.1% | 0.0000 |

| Suspect an unfaithful partner | 23.9% | 34.7% | 0.0000 | 26.9% | 51.6% | 0.0000 |

| Pre-marital | 22.1% | 26.6% | 0.0167 | 17.9% | 19.2% | 0.0002 |

| Pre-conception | 3.4% | 1.4% | 0.4464 | 4.4% | 7.2% | 0.0068 |

p-value denotes significance of trend among all clients (Nov 2003 - Dec 2007)

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of correlates of seropositivity and ART access in a population of first-time VCT clients in Moshi, Tanzania, 2003-2007.

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Clients | Pre-CTC | CTC Scale-up | All Clients | Pre-CTC | CTC Scale-up | |

| N | 1827 OR [95% CI] |

460 OR [95% CI] |

554 OR [95% CI] |

2426 OR [95% CI] |

562 OR [95% CI] |

712 OR [95% CI] |

| Age | 1.01 [1.00;1.03] |

1.01 [0.98;1.04] |

1.00 [0.97;1.03] |

1.00 [0.99;1.01] |

0.99 [0.97;1.01] |

1.00 [0.98;1.03] |

| Primary school education or less | 1.45 * [1.01;2.07] |

2.28 * [1.14;4.53] |

1.19 [0.58;2.45] |

1.28 [0.99;1.67] |

1.17 [0.65;2.10] |

1.52 [0.93;2.50] |

| Rural residence | 1.49 * [1.07;2.09] |

1.35 [0.70;2.60] |

1.28 [0.63;2.60] |

0.93 [0.75;1.16] |

0.90 [0.57;1.42] |

1.08 [0.70;1.66] |

| Marital Status (single is reference) | ||||||

| Cohabitating | 5.76 *** [3.49;9.51] |

4.36 ** [1.58;12.03] |

8.59 *** [2.68;27.55] |

2.73 *** [1.94;3.86] |

2.54 * [1.21;5.35] |

3.95 *** [1.98;7.88] |

| Divorced/separated | 2.99 *** [1.67;5.34] |

2.37 [0.64;8.76] |

5.51 ** [1.89;16.06] |

2.13 *** [1.50;3.03] |

2.63 * [1.25;5.55] |

1.79 [0.91;3.49] |

| Widowed | 6.43 *** [3.11;13.31] |

3.11 [0.76;12.69] |

26.41 *** [5.57;125.12] |

4.57 *** [3.21;6.49] |

3.05 ** [1.54;6.02] |

3.84 *** [1.85;7.98] |

| Married | 1.80 * [1.11;2.90] |

1.96 [0.86;4.45] |

2.90 [0.99;8.55] |

1.19 [0.86;1.64] |

1.12 [0.58;2.14] |

1.14 [0.58;2.20] |

| Behavioral Risk Characteristics | ||||||

| More than 3 lifetime partners | 1.53 * [1.04;2.25] |

2.03 [0.96;4.28] |

1.81 [0.72;4.51] |

1.97 *** [1.55;2.51] |

1.17 [0.65;2.11] |

2.82 *** [1.70;4.67] |

| Number of lifetime partners | 1.00 [0.99;1.02] |

0.97 [0.91;1.04] |

1.00 [0.97;1.03] |

1.01 [0.98;1.05] |

1.05 [0.94;1.17] |

1.00 [0.92;1.10] |

| Symptoms | ||||||

| Any symptoms | 1.66 [0.97;2.84] |

2.33 [0.95;5.72] |

0.75 [0.17;3.29] |

2.07 *** [1.44;2.97] |

1.86 [0.96;3.62] |

1.53 [0.66;3.58] |

| Number of symptoms 1 | 1.81 *** [1.50;2.19] |

1.56 ** [1.19;2.05] |

2.58 ** [1.41;4.71] |

1.76 *** [1.52;2.04] |

1.73 *** [1.34;2.25] |

2.10 *** [1.44;3.07] |

| Test for Equality: Pre-CTC vs. CTC Scale-up | p=0.7401 | p=0.3729 | ||||

OR = odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval

Mean number of symptoms for clients with any symptoms

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

The differential effects of the three explanatory domains (sociodemographic characteristics, behavioral risk characteristics, and symptoms) on seroprevalence are summarized in Table 4. For females, changes in sociodemographic characteristics and symptoms resulted in decreased seroprevalence (p=0.002 and p<0.0001, respectively)). For males, symptom-related decreases in seropositivity (p<0.0001) were partially offset by small increases in behavioral risk characteristics (p=0.0590)

Table 4. Estimated contribution of sociodemographic characteristics, behavioral risk characteristics, and symptoms to observed changes in rates of seropositivity of first-time clients presenting for VCT in Moshi, Tanzania, 2003-2007.

| Males | Females | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect on Seroprevalence | P-value | Confidence Interval | Effect on Seroprevalence | P-value | Confidence Interval | |||

| Sociodemographics Characteristics | -0.77% | 0.1350 | -1.79% | 0.24% | -2.12% | 0.0020 | -3.48% | -0.76% |

| Behavioral Risk Characteristics | 0.19% | 0.0590 | -0.01% | 0.38% | 0.21% | 0.5990 | -0.57% | 0.99% |

| Symptoms | -3.77% | 0.0000 | -5.27% | -2.26% | -6.51% | 0.0000 | -8.80% | -4.21% |

Discussion

In this analysis of over 4300 consecutive clients presenting for first-time VCT over 50 months and including intervals before and after CTC expansion in Moshi, Tanzania, we describe a significant decrease in HIV seroprevalence for both women and men. Reductions in symptoms for both men and women and a more favorable distribution of sociodemographic risk factors among women contributed to this decrease.

While causality between the scale-up of CTCs and changes in VCT client characteristics cannot be assessed from this study, it is evident that the proportion of clients found to be HIV seropositive decreased significantly in this region with the addition of more CTCs. Several reasons could underlie the results seen. Persons who suspect they are HIV infected (either because they have a family member being cared for at a CTC or because they are symptomatic) may prefer to be tested at sites where treatment is known to be available. It is also possible that because treatment availability may reduce community stigma, community members may be more inclined to access testing even when well 23. It has been shown in South Africa that VCT coupled with ART availability changes community perceptions favorably 24. Similarly, educational campaigns concurrent with CTC scale-up up may have resulted in a broader population accessing VCT services. This is supported by the changing sociodemographic characteristics of women. Another possibility is that seroprevalence is decreasing in the general population. Nationally, Tanzania has seen a decreasing trend over the past few years, with seropositivity rates dropping from 9% in 2003 1 to 7% in 2004 25 to 6.5% in 2005 to 6% in 2007-08 1. As shown in Figure 1, population-based survey estimates of HIV seroprevalence in the Kilimanjaro Region were 7.3% in 2003-04 and 1.9% in 2007-08. Even though prevalence decreases of such magnitude seem unlikely, it is quite possible that seroprevalence is actually decreasing in this region;22 additional data are needed to corroborate these observations. Our data and those from other similar cohorts suggest that all of the explanations may have contributed to these changes.

We also note persisting differences among VCT clients by gender. Disparity of power within relationships and in society are prominent within sub-Saharan culture, and are often cited as contributing factors to higher HIV risk among women in this region 26. It is possible that greater access to care and treatment may attenuate gender disparities by providing more personal control of health to men and women equally. Despite this hypothesis, our results show a continuing gender differential in HIV seroprevalence, suggesting that, for females, testing may be viewed less as a means of prevention and more as an entry point to care, plausibly leading to gender-specific responses to the increased access to CTCs.

We note several limitations to this study. All results were self-reported by clients; underestimation of current sexual behaviors may have occurred due to social desirability bias 27. Similarly, clients are a self-selected group who attend counseling and testing services voluntarily and cannot be considered a sample of the general population. Also, our pre-CTC period estimates are limited to a relatively short period, and thus we cannot fully distinguish what occurred during this time frame; there may have been changes in anticipation of the provision of free ART that we could not detect. Finally, other correlates of seropositivity not included in our analyses may have contributed to the observed changes in seropositivity over time. It is not possible to ascertain the contribution of other characteristics from our data.

Collectively, these findings hold several important policy-level and programmatic implications for VCT programs. Firstly, as CTC sites increase in number and become more decentralized, more symptomatic clients may access HIV testing services at sites where antiretrovirals are offered. Free-standing VCT sites may thus become a less-cost effective means for HIV case-finding. Given the rationale and mandate for universal testing in this region and anticipated worsening fiscal constraints, alternative methods for identifying HIV-infected persons, such as mobile VCT, provider-initiated testing and counseling, home-based testing, and CTC-based testing campaigns and their relative cost-effectiveness should be explored. Secondly, because the declines in seroprevalence among first-time testers at this VCT site seem to mirror those of population-based serosurveys for the Kilimanjaro Region, seroprevalence data from stable VCT sites, such as this one, may be useful for ascertaining trends reflective of the larger population, despite the inherent bias of this self-selected, self-referred sample. Thirdly, we observed no appreciable changes in behavior risk characteristics over time; there remains a pressing need to sharpen and focus HIV risk behavior reduction messaging.

In conclusion, we identified a decrease in seroprevalence in both genders. Declines in symptoms contributed to this overall finding in both men and women, as did a more favorable distribution of sociodemographic risks among women. Although this analysis cannot establish a causal relationship between these events and the scale-up of CTCs within this region, it is clear that the client population presenting for VCT has changed. It will be important for VCT programs to incorporate this new knowledge into their prevention programs if they are to appropriately target the changing needs of their client population.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants, and the staff, volunteers, and counselors of KIWAKKUKI. This study was supported in part by Roche laboratories; the National Institutes of Health: AIDS Clinical Trials Group (5U01 AI069484-02) and International Studies of AIDS Associated Co-infections (U01 AI062563-04) (Drs. Bartlett, Crump, and Thielman), and Mid-career Investigator and Center for AIDS Research (P30AI64518; Dr. Bartlett); US Department State Fulbright Program (Dr. Thielman); and the Hubert-Yeargan Center for Global Health (Dr. Tribble and Ms. Mayhood).

Sources of support: Roche Laboratories

National Institutes of Health: AIDS Clinical Trials Group (5U01 AI069484-02) and International Studies of AIDS Associated Co-infections (U01 AI062563-04), (Drs. Bartlett, Crump, and Thielman), and Mid-career Investigator (K24 AI-0744-01) and Center for AIDS Research (P30AI64518) (Dr. Bartlett)

US Department State Fulbright Program (Dr. Thielman)

Hubert-Yeargan Center for Global Health, Duke University Medical Center (Dr. Tribble and Ms. Mayhood)

Footnotes

Data Presented at: 4th International AIDS Society (IAS) Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention, Sydney, 22-25 July 2007

Conflicts of Interest: Authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.UNAIDS, WHO. AIDS Epidemic Update: December 2007. Geneva: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT): UNAIDS Technical Update. Geneva: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salomon JA, Hogan DR, Stover J, et al. Integrating HIV prevention and treatment: from slogans to impact. PLos Med. 2005;2(1 e16):0050–0056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo C. Achievable standard of care in low-resource settings. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000 Nov;918:179–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Voluntary HIV-1 Counseling and Testing Efficacy Study Group. Efficacy of voluntary HIV-1 counselling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000 Jul 8;356(9224):103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van de Perre P. HIV voluntary counselling and testing in community health services. Lancet. 2000;356:86–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02462-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godfrey-Faussett P, Maher D, Mukadi YD, Nunn P, Perriens J, Raviglione M. How human immunodeficiency virus voluntary testing can contribute to tuberculosis control. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(12):939–945. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landman K, Thielman N, Mgonja A, et al. Risk factors for low HIV treatment literacy among clients presenting for voluntary counseling and testing in Moshi, Tanzania. 3rd IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis and Treatment; Vol Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Republic of Tanzania. HIV/AIDS care and treatment plan 2003-2008. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamptey P, Wilson D. Scaling up AIDS treatment: what is the potential impact and what are the risks? PLos Med. 2005;2(2):102–104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stover J, Bertozzi S, Gutierrez JP, et al. The global impact of scaling up HIV/AIDS prevention programs in low- and middle-income countries. Science. 2006;311:1474–1476. doi: 10.1126/science.1121176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baggaley RF, Garnett GP, Ferguson NM. Modeling the impact of antiretroviral use in resource-poor settings. PLos Med. 2006;3(4):493–504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nuwaha F, Kabatesi D, Muganwa M, Whalen CC. Factors influencing acceptability of voluntary counselling and testing for HIV in Bushenyi District of Uganda. East Afr Med J. 2002;79(12):626–632. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v79i12.8669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, Solberg P, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2006;20:85–92. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196566.40702.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukherjee J, Farmer J, Leandre F, et al. Access to antiretroviral treatment and care: the experience of the HIV Equity Initiative, Cange, Haiti. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antiretroviral therapy in primary health care: experience of the Khayelitsha programme in South Africa. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Medecins sans Frontieres South Africa, Department of Public Health at the University of Cape Town, Provincial Administration of the Western Cape SA. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warwick Z. The influence of antiretroviral therapy on the uptake of HIV testing in Tutume, Botswana. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17:479–481. doi: 10.1258/095646206777689189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Health National AIDS Control Programme. National Guidelines for Voluntary Counselling and Testing, 2005. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu HY, Crump JA, Ostermann J, et al. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of clients presenting for HIV voluntary counseling and testing in Moshi, Tanzania. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:691–696. doi: 10.1258/095646205774357307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministry of Health. HIV/AIDS/STI Surveillance Report: January - December 2005, Report Number 20. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Health. Tanzania HIV/AIDS Indicator Survey 2003-04. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanzania Commission for HIV/AIDS. Tanzania HIV/AIDS and Malaria Indicator Survey 2007-08. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glick P. Scaling up HIV voluntary counseling and testing in Africa: what can evaluation studies tell us about potential prevention impacts? Located at: Strategies and Analysis for Growth and Access. 2005 doi: 10.1177/0193841X05276437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy NC, Miksad RA, Fein OT. From treatment to prevention: the interplay between HIV/AIDS treatment availability and HIV/AIDS prevention programming in Khayelitsha, South Africa. J Urban Health. 2005;82(3):498–509. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra V, Vaessan M, Boerma JT, et al. HIV testing in national population-based surveys: experience from the Demographic and Health Surveys. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:537–545. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.029520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Interagency Coalition on AIDS and Development. HIV/AIDS and Gender Issues. Ottawa, ON: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregson S, Mushati P, White PJ, Mlilo M, Mundandi C, Nyamukapa C. Informal confidential voting interview methods and temporal changes in reported sexual risk behavior for HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:36–42. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]