Abstract

Objective

To examine racial/ethnic longitudinal disparities in antimanic medication use among adults with bipolar-I disorder.

Methods

Observational study using administrative data from Florida’s Medicaid program, July 1997-June 2005, for enrollees diagnosed with bipolar-I disorder (N=13,497 persons; 126,413 person-quarters). We examined the likelihood of receiving one of the following during a given quarter: 1) any antimanic agent (antipsychotic or mood stabilizer) or none, and 2) mood stabilizers, antipsychotic monotherapy, or neither. Binary and multinomial logistic regression models predicted the association between race/ethnicity and prescription fills, adjusting for clinical and demographic characteristics. Cohort indicators for year that the enrollee met study criteria were included to account for cohort effects.

Results

Averaging over all cohorts and quarters, compared to whites, blacks had lower odds of filling any antimanic and mood stabilizer prescriptions specifically (40%–49% and 47%–63% respectively), but similar odds of filling prescriptions for antipsychotic monotherapy. After Bonferroni adjustment, compared to whites, there were no statistically significant disparities for Hispanics in filling prescriptions for any, or specific antimanic medications.

Conclusions

Rates of antimanic medication use were low regardless of race/ethnicity. However, we found disparities in antimanic medication use for blacks compared to whites and these disparities persisted over time. We found no Hispanic-white disparities. Quality improvement efforts should focus on all individuals with bipolar disorder, but particular attention should be paid to understanding disparities in medication use for blacks.

Suggested Key Words: bipolar disorder, quality of health care, healthcare disparities, health services research

Introduction

Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health care persist,1–7 partly because some groups gain greater access to new therapies.8, 9 Discrimination and other social factors have been identified as sources of disparities. Evidence for both exists in mental health care.10, 11 Low-income members of racial/ethnic minorities with serious mental illness may have the most difficulty in navigating the healthcare system.

Bipolar disorder provides an opportunity to study disparities in a vulnerable and severely ill population for whom medication options have been rapidly expanding—particularly second-generation antipsychotics. During the 1990s, these drugs were used “off label” by some patients for the treatment of bipolar disorder. In 2000, olanzapine became the first second-generation antipsychotic to receive FDA approval for the acute manic phase. By 2004, the remaining second-generation antipsychotics were similarly FDA indicated. Since 2004, some have received FDA indications for other bipolar treatment phases also, such as mania prophylaxis (olanzapine in 2004, aripiprazole in 2005). Further, as a class, these medications are increasingly acceptable for treating mania according to guidelines.12, 13 Second-generation antipsychotics have a different, and for some, better tolerated acute side-effect profile than non-dopamine blocking antimanic agents and do not require blood-level monitoring. The disadvantages of these medications are a higher risk of obesity and diabetes14 and greater costs compared to older antimanic medications such as mood stabilizers (e.g., lithium and valproate).

There are several important, unanswered questions about changes in bipolar disorder pharmacotherapy utilization trends. Are second-generation antipsychotics replacing older agents or instead expanding the pool of bipolar patients who take antimanic medication? Does this vary by race/ethnicity? Are there racial/ethnic disparities in antimanic medication utilization during an earlier time period, prior to second-generation antipsychotics receiving bipolar disorder FDA indications or inclusion in guideline recommendations? Also, are there racial/ethnic differences in utilizing specific antimanic medications (i.e., mood stabilizers or antipsychotics) over time?

Depp et al15 examined changes in antimanic prescription fills in San Diego Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder from 2001–2004 and found antimanic medication disparities for both blacks and Hispanics, compared to whites, and some overall increase in antimanic medication fills over time. However, it is unclear how generalizable their results would be to another Medicaid population. Further, their study inclusion of enrollees with any bipolar spectrum disorder, and inclusion of treatment with novel anticonvulsants (some with either no or unclear bipolar efficacy), make interpreting their results difficult from a quality perspective.

We study the changes in bipolar medication utilization and potential disparities by examining whether antimanic medication utilization patterns for adults diagnosed with bipolar-I disorder differ, and differentially change over time, for blacks and Hispanics compared to whites in Florida’s Medicaid population during 1997 through 2005. We include only enrollees diagnosed with bipolar-I disorder, since the guidelines are clear that all patients with bipolar-I should receive antimanic medications both when acutely manic and for mania prophylaxis—but are less clear on the need for mania prophylaxis for other (i.e., non-bipolar-I spectrum disorders). We also include only medications with either FDA indication or guideline support for treating bipolar mania. Florida is a large, ethnically diverse state and its Medicaid program is the fourth largest.16 We examine disparities in any antimanic medication use, as well as specific types (i.e., mood stabilizers vs. antipsychotics). Examining potential disparities for type of antimanic medication used is also important because there is no evidence that patients with bipolar disorder of different races/ethnicities respond differentially to mood stabilizers versus antipsychotics.17 We hypothesize that racial disparities exist for both antimanic prescription use in general, and for use of specific types of antimanic medications.

Methods

Data and Local Context

We use administrative data from the Florida Medicaid program from July 1996–June 2005 that included enrollee claims for outpatient and inpatient visits, and prescriptions. During the study period there were no Medicaid policy restrictions such as prior authorization requirements on the antimanic medications. This study was approved by the Harvard Medical School IRB (case number M12489-108).

Bipolar Cohort Identification

Claims data have demonstrated validity in determining a bipolar cohort for assessing population-based quality of care, with predictive positive values of 95%.18, 19 To identify a cohort of patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder, we first identified enrollees with any bipolar disorder diagnosis (ICD-9-CM 296.0, 296.1, 296.4–296.8, 301.11, 301.13) in the administrative claims. We then excluded enrollees with schizophrenia diagnoses occurring either prior to or within a year after the first observed bipolar diagnosis. Next, we required: 1) at least two claims with a bipolar disorder diagnosis, or 2) if one claim, it was inpatient or represented at least 50% of all outpatient mental health claims for the enrollee. At least one claim with a bipolar diagnosis had to be from a psychiatrist. After identifying this preliminary sample of bipolar subjects, we then selected those with at least one claim for bipolar-I disorder (ICD9-CM 296.0, 296.1, 296.4–296.7). We selected bipolar-I because: 1) other bipolar spectrum disorder diagnoses, with more subtle clinical presentations, may be less accurate in claims data, and 2) the guidelines are less clear whether persons with other bipolar spectrum disorders (i.e., not bipolar I) require antimanic maintenance treatment.

Because our unit of analysis was the patient-quarter, we included only patient-quarters for which enrollees were between ages 18 and 64. Quarters after age 64 were excluded to reduce the probability of antipsychotic use for comorbid dementia symptoms (which would become increasingly prevalent after age 64). We eliminated patient-quarters for which the Medicaid program was not financially responsible for medication expenditures (e.g., if an individual was enrolled in an HMO). Because Medicaid has monthly enrollment, we required enrollment for at least one month of a given quarter, thereby ensuring each study subject had the opportunity to fill a prescription in that quarter.

Outcome Measures

Our main outcome was the presence of a filled prescription for an antimanic medication, defined as either a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Mood stabilizers were defined as non-dopamine blocking antimanic medications either recommended by national expert consensus guidelines12, 13, 20, 21 or indicated by the FDA for mania prophylaxis before July 2005. These included lithium, valproate, carbamazepine and lamotrigine. Among antipsychotic medications, the FDA indications and newer bipolar disorder expert guideline recommendations are primarily limited to second-generation agents.12, 13 However, we included first-generation antipsychotics because they traditionally have had a role in bipolar disorder antimanic treatment due to their demonstrated efficacy (particularly in the acute manic phase), 21 and the most recent guidelines do not discount them as an acceptable option (albeit not first line).13 Notably, both the literature and our preliminary data analyses indicate that increasingly patients are prescribed second-generation antipsychotics rather than first,22, 23 so the distinction between them is less relevant over time.

Explanatory Variables

Race/ethnicity, our primary explanatory variable, was coded as white, black, Hispanic, and —other and missing. Enrollees entering the program through Supplemental Security Income (SSI) eligibility have their race/ethnicity information reported to the state Medicaid program through records from the Social Security Administration (SSA). Prior to 1999, SSA records only included racial categories of black, white and other.24, 25 Thus, Hispanic persons receiving Medicaid eligibility initially through SSI prior to 1999 were likely coded as —other/missing. Florida’s Medicaid program has implemented procedures to improve the pre-1999 enrollee ethnicity data using other data sources where possible.26 To account for racial/ethnic misclassification prior to 1999, and other possible “cohort” effects, we included in the model an indicator variable for the year in which the enrollee first appeared in our sample. Unlike subsequent cohorts, those in FY1996 consisted of “incident and prevalent” cases of bipolar disorder, and were therefore dropped from the analysis.

We adjusted for enrollee clinical and demographic characteristics that might influence medication choices. These included: age, sex, and Medicaid eligibility category (Medicare, SSI, AFDC/pregnant women/family planning, or other [General Assistance, HMO or Medicaid ineligible, Medically Needy]). We also adjusted for co-occurring conditions such as substance use disorders and medical conditions that might influence mood stabilizer or antipsychotic prescribing due to medication side effect profiles or increased risk of non-adherence. The co-occurring conditions were grouped into three categories of dichotomous variables; those that may: 1) discourage mood stabilizer prescribing (thyroid, renal, pancreatic, inflammatory and hepatic disorders, aplastic anemia/agranulocytosis and pregnancy, 2) discourage antipsychotic prescribing (obesity, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, cardiac conditions, glaucoma/cataracts, pituitary disorders and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder), or 3) promote mood stabilizer prescribing (seizure disorders). All co-occurring conditions were considered present after the first observed claim with the respective ICD-9 diagnosis. The exception, pregnancy, was identified through ICD-9 and pregnancy specific Current Procedure Terminology (CPT)27 codes; if no termination/delivery code was seen, then a pregnancy was considered to end nine months after the first observed pregnancy claim. Time trends were modeled using a linear term that represented the quarter in which the prescription was filled, with the first quarter in 1997 as the referent quarter, as well as a quadratic term for quarter that permitted non-linearity over time.

Statistical Analyses

The unit of analysis was the person-quarter. We estimated two logistic regression models, each including the same explanatory variables and utilizing the full population of FY1997-FY2004 cohorts. In the first model, our outcome was the likelihood of filling a prescription for any antimanic medication during a quarter versus none in a quarter. In the second model, we estimated a multinomial logistic regression model where the outcome assumed one of three levels describing the prescription in a quarter: 1) a mood stabilizer (with or without an antipsychotic), 2) antipsychotic monotherapy (i.e., without a mood stabilizer), or 3) neither (the reference category). We included several interaction terms to accommodate temporal trends in medication use: race/ethnicity by quarter, race/ethnicity by cohort, and quarter by cohort. For the binary outcome, repeated measurements on the same enrollee were accommodated by using a generalized estimating equations (GEE) approach with an autoregressive correlation structure.28 Standard errors of model estimates were then adjusted to reflect within-subject correlation. Autoregressive GEE cannot easily be extended to outcomes with multiple unordered levels. Therefore, for our three-category response, we permitted within-subject dependence but not serially. We adjust for multiple racial/ethnic comparisons by using a Bonferroni adjustment that considered p. values <0.025 as significant in the binary model for any antimanic medication and values <0.0125 as significant in the multinomial model.

We summarized our findings in three different ways. First, we highlight two of the eight cohorts (FY1997 and FY2000), by calculating odds ratios and interval estimates of prescription fills for the minority group relative to whites in the first and in last quarters of the cohort year. The 1997 cohort was selected because it represents patterns of care in the beginning of our observational period. This was also a period when second-generation antipsychotics were off-label for bipolar disorder. The 2000 cohort was selected as a cohort to highlight in the middle of our observational period, and also as one of the first cohorts in which Hispanic ethnicity was not misclassified by the SSA. Second, we tested for trends in disparities for all cohorts (i.e., FY1997 through FY2004) by examining the statistical significance of the race/ethnicity by quarter interaction term, and computed these trends by year, rather than quarter. To provide a quantitative summary of the disparity trends, we calculated odds ratios of this interaction term and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Third, we again highlighted cohorts FY1997 and FY2000 by calculating predicted probabilities of antimanic medication utilization for these cohorts. We computed these probabilities for each eligible quarter, and averaged by race/ethnicity to obtain summary estimates at each time point.

First quarter FY2001 had incomplete data due to changes in state reporting/accounting. We considered these data to be missing completely at random because administrative changes were responsible for these gaps, and eliminated them from the analyses. Additionally, 8.6% of the ethnicity data were coded by the state as—missing and other. Because our inability to disaggregate the missing from —other makes interpreting results for this category problematic, we excluded these individuals from our analysis.

Results

The total bipolar-I sample across the nine cohort-years consisted of 13,497 adults; corresponding to 126,413 person-quarters. The racial/ethnic composition varied over time (Table 1). The increased Hispanic proportion is consistent with the SSA changes in reporting,24, 25 and the nearly 45% increase in the Florida Hispanic population between years 1996 and 2006.29, 30 Patient characteristics differed for the three racial/ethnic groups. Compared to whites and blacks, Hispanics were less likely to receive their Medicaid eligibility through categories indicating disability: SSI and dually eligible for Medicare (which may be an artifact of the SSA coding changes). Hispanics were also less likely than whites or blacks to be identified as having a co-occurring substance use disorder. Approximately three-quarters of whites and Hispanics filled an antimanic medication prescription in at least one quarter compared to two-thirds of blacks. Whites were most likely to ever fill prescriptions for a mood stabilizer (whites 58%, blacks 43%, and Hispanics 46%). Hispanics were most likely to ever fill a prescription for an antipsychotic but never a mood stabilizer (Hispanics 46%, blacks and whites 37%).

Table 1.

Unadjusted characteristics of Florida Medicaid Bipolar-I diagnosed study cohort (fiscal years 1997–2004, N = 13,497 adults).

| White | Black | Hispanic; | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Number of unique adults | 11,020 | 1,256 | 1,221 | |||

| Number of unique adults per cohort fiscal-year year | ||||||

| 1997 | 1,533 | 83.7% | 194 | 10.6% | 105 | 5.7% |

| 1998 | 1,453 | 84.6% | 161 | 9.4% | 103 | 6.0% |

| 1999 | 1,333 | 80.2% | 168 | 10.1% | 162 | 9.7% |

| 2000 | 1,454 | 82.4% | 153 | 8.7% | 158 | 9.0% |

| 2001 | 1,538 | 82.0% | 166 | 8.9% | 171 | 9.1% |

| 2002 | 1,584 | 80.8% | 159 | 8.1% | 217 | 11.1% |

| 2003 | 1,272 | 79.4% | 166 | 10.4% | 164 | 10.2% |

| 2004 | 853 | 78.8% | 89 | 8.2% | 141 | 13.0% |

| Study sample characteristics | ||||||

| Male | 3,296 | 29.9 | 360 | 28.7 | 325 | 26.6 |

| Predominate Medicaid eligibility category (person-quarter) | ||||||

| Medicare | 3,080 | 28.0 | 363 | 28.9 | 236 | 19.3 |

| SSI | 3,949 | 35.8 | 493 | 39.2 | 359 | 29.4 |

| AFDC, Pregnancy, and Family Planning | 2,726 | 24.7 | 314 | 25.0 | 485 | 39.7 |

| Other Eligibilitya | 1,265 | 11.5 | 86 | 6.8 | 141 | 11.5 |

| Co-occurring conditions (ever diagnosed in a person-quarter) | ||||||

| Substance Use Disorder | 3,033 | 27.5 | 309 | 24.6 | 164 | 13.4 |

| Conditions that may influence prescribing: | ||||||

| Increase mood stabilizerb | 431 | 3.9 | 40 | 3.2 | 32 | 2.6 |

| Decrease mood stabilizerc | 5,825 | 52.9 | 537 | 42.7 | 580 | 47.5 |

| Decrease D2 antagonistsd | 320 | 2.9 | 16 | 1.3 | 16 | 1.3 |

| Decrease second-generatione | 3,508 | 31.8 | 402 | 32.01 | 434 | 35.5 |

| Prescribing patterns during study period (ever in a person-quarter) | ||||||

| Any antimanic agent | 8,345 | 75.5 | 835 | 66.5 | 908 | 74.4 |

| Mood stabilizerf | 6,410 | 58.2 | 538 | 42.8 | 563 | 46.1 |

| Lithium | 2,676 | 24.3 | 187 | 14.9 | 201 | 16.5 |

| Valproate | 3,867 | 35.1 | 361 | 28.7 | 344 | 28.2 |

| Carbamazepine | 1,028 | 9.3 | 72 | 5.7 | 54 | 4.4 |

| Lamotrigine | 1,159 | 10.5 | 46 | 3.7 | 114 | 9.3 |

| Antipsychotic in absence of mood stabilizer | 4,136 | 37.5 | 473 | 37.7 | 566 | 46.4 |

| Mean | Std | Mean | Std | Mean | Std | |

| Age when first entered study cohort | 36.0 | 11.1 | 34.0 | 10.9 | 36.0 | 11.6 |

General Assistance, HMO or Medicaid ineligible, Medically Needy

Seizure disorders

Thyroid, renal, pancreatic, hematologic, hepatic and inflammatory conditions requiring NSAIDs, viral hepatitis, pregnancy.

Pituitary conditions and ADHD.

Cardiovascular conditions, obesity, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, glaucoma, cataracts, ADHD.

Lithium, valproate, carbamazepine or lamotrigine.

Adjusting for clinical and demographic characteristics, in the 1997 and 2000 cohorts, disparities emerged in the likelihood of utilizing any antimanic medication (Table 2). At each contrasted time point and in both cohorts, blacks had 40%–49% lower odds of filling an antimanic prescription compared to whites. After Bonferroni adjustment, there were no statistically significant disparities between Hispanics and whites in filling any antimanic medication in either cohort. The disparities time-trend analyses for all cohorts (i.e., cohorts FY1997 through FY2004) indicated no changes over time. In sum, these disparities for blacks persisted over time and in all cohorts (OR.98[0.94–1.02]), whereas for Hispanics no disparities were found in any cohort (OR 1.03[0.98–1.08].

Table 2.

Adjusted quarterly racial/ethnic disparities and trends in the odds of filling any antimanic prescriptions in bipolar-I diagnosed population in Florida’s Medicaid program (N=13,497 adults).a

| Fiscal-Year 1997 Cohort N= 1,832 | Fiscal-Year 2000 Cohort N= 1,765 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Quarter, Fiscal-Year 1997 | 4th Quarter, Fiscal-Year 2004 | 1st Quarter, Fiscal-Year 2000 | 4th Quarter, Fiscal-Year 2004 | |||||

| Any antimanic medicationb | ||||||||

| OR | CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Whites | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Blacks | ..60*** | .46–.79 | .52*** | .37–.73 | .56** | .42–.75 | .51*** | .38–.70 |

| Hispanics | .71 | .51–.99 | .87 | .57–1.33 | .87 | .66–1.15 | .99 | .74–1.33 |

| Annual Trends Among All Cohortsc | OR | CI | ||||||

| Whites | 1 | |||||||

| Blacks | .98 | .94–1.02 | ||||||

| Hispanics | 1.03 | .98–1.08 | ||||||

All comparisons are relative to whites

Comparison: no antimanic medication

Interaction of race/ethnicity and time

Bonferroni adjusted significance for a binary outcome:

p. =≤0.25

p. ≤.005

p. ≤.0005

For blacks but not Hispanics, differences were observed in filling specific antimanic prescriptions in these two cohorts, compared to whites (Table 3). In both cohorts, blacks had 50%-63% lower odds of filling a mood stabilizer prescription (with statistical significance achieved in all but for the 4th quarter in the FY2000 cohort). No statistically significant disparities were found in the odds of Hispanics filling mood stabilizer prescriptions. For neither blacks nor Hispanics was there a statistically significant disparity in receiving antipsychotic monotherapy for both cohorts. Again, there were no changes for blacks or Hispanics in the disparities trends over time. Thus, for all cohorts (i.e., cohorts FY 1997-FY2004), when specific antimanic medication disparities were present at baseline they persisted, unchanged, over time.

Table 3.

Adjusted quarterly racial/ethnic disparities and trends in the odds of filling specific antimanic prescriptions in bipolar-I diagnosed population in Florida’s Medicaid program (N=13,497 adults).

| Fiscal-Year 1997 Cohort N= 1,832 | Fiscal-Year 2000 Cohort N= 1,765 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Quarter, Fiscal-Year 1997 | 4th Quarter, Fiscal-Year 2004 | 1st Quarter, Fiscal-Year 2000 | 4th Quarter, Fiscal-Year 2004 | |||||

| Specific antimanic medicationsa,b | ||||||||

| OR | CI | OR | CI | OR | CI | OR | CI | |

| Mood stabilizerc | ||||||||

| Whites | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Blacks | .50*** | .36–.69 | .57 | .35–.93 | .37*** | .24–.57 | .40*** | .25–.64 |

| Hispanics | .63 | .40–.98 | .71 | .38–1.35 | .74 | .50–1.08 | .80 | .52–1.21 |

| Antipsychoticd | ||||||||

| Whites | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Blacks | .97 | .59–1.60 | .57 | .34–.97 | .88 | .58–.1.34 | .64 | .41–1.00 |

| Hispanics | 1.47 | .91–2.36 | 1.11 | .62–1.99 | 1.38 | .94–2.03 | 1.17 | .79–1.72 |

| Annual Trends Among All Cohortsc | OR | CI | ||||||

| Mood stabilizerd | ||||||||

| Whites | 1 | |||||||

| Blacks | 1.02 | .96–1.08 | ||||||

| Hispanics | 1.02 | .95–1.09 | ||||||

| Antipsychotice | ||||||||

| Whites | 1 | |||||||

| Blacks | .93 | .87–1.00 | ||||||

| Hispanics | .96 | .90–1.03 | ||||||

All comparisons are relative to whites

Comparison: no antimanic medication

Interaction of race/ethnicity and time.

Lithium, valproate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine (with or without antipsychotic medication)

Without mood stabilizer

Bonferroni adjusted for a multinomial outcome

p. = ≤0.0125

p. ≤.0005

p. ≤.0003

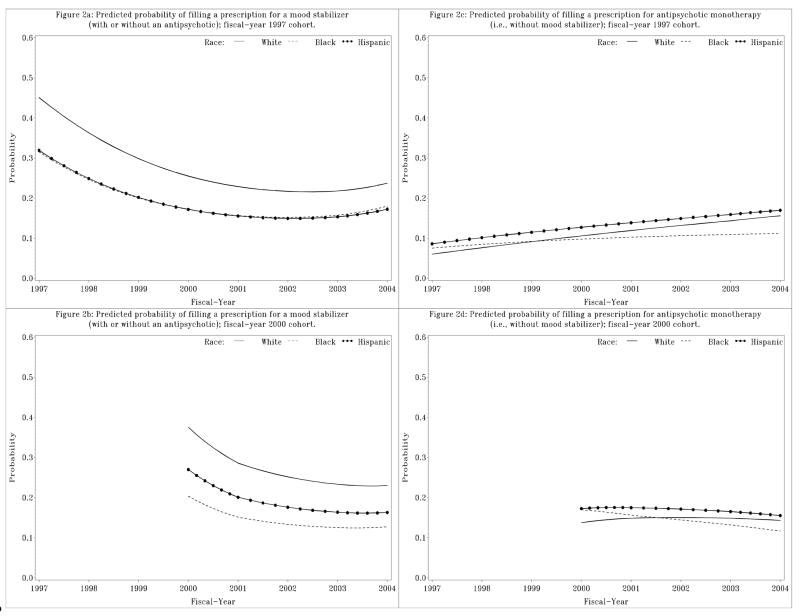

Figures 1a and 1b display the predicted probabilities of filling a prescription for any antimanic medication for the 1997 and 2000 fiscal-year cohorts. Notably, in both cohorts, the probability of filling any antimanic agent was low at baseline (45%-60%). Blacks were least likely to fill a prescription for any antimanic agent, Hispanics had a somewhat higher probability, and whites were most likely. The trajectory for the 1997 cohort declines until approximately year 2000, and then improves, whereas the trajectory for the 2000 cohort only declines over our observation period.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Predicted probability of filling a prescription for any antimanic agent; fiscal-year 2000 cohort.

Figure 1b. Predicted probability of filling a prescription for any antimanic agent; fiscal-year 1997 cohort.

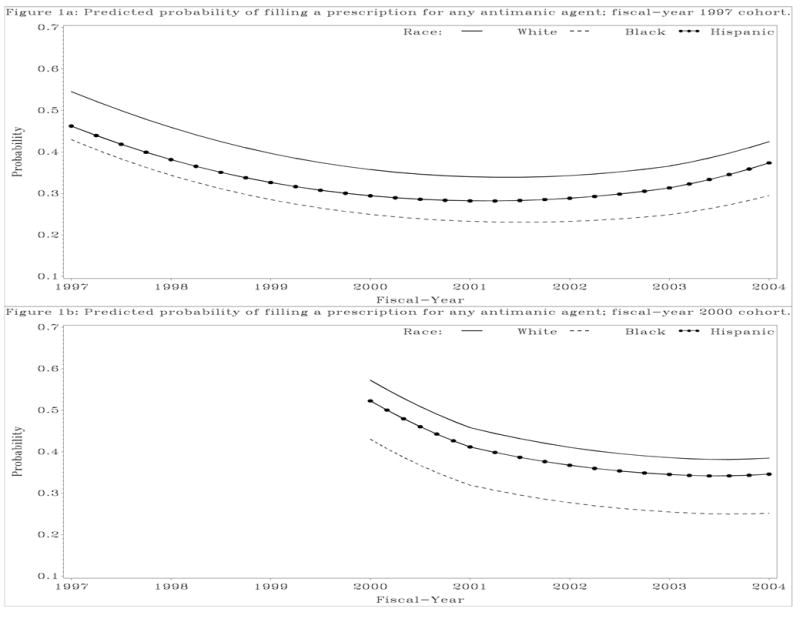

The 1997 and 2000 fiscal-year cohort predicted probabilities of filling prescriptions for specific antimanic medication categories are illustrated in Figures 2a through 2d. Half or fewer of the person-quarters included mood stabilizer utilization, and the overall use of mood stabilizers declined in both cohorts (Figures 2a & 2b). Although not statistically significant based on the cohort contrast results in Table 3, blacks and Hispanics were less likely to fill mood stabilizer prescriptions. In the 2000 cohort, although blacks and Hispanics had lower predicted probabilities of filling mood stabilizers compared to whites, statistically significant differences were only seen for blacks. While race/ethnicity changes in the probability of antipsychotic monotherapy prescription fills were not statistically different over time, there does seem to be some narrow differences by cohort (Figures 2c and 2d). In the 1997 cohort, there was a trend toward increasing antipsychotic monotherapy use among all groups, but less so for blacks. In the 2000 cohort, antipsychotic monotherapy use remained similar over time for whites and Hispanics but declined somewhat for blacks.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Predicted probability of filling a prescription for a mood stabilizer (with or without an antipsychotic); fiscal-year 2000 cohort.

Figure 2b. Predicted probability of filling a prescription for a mood stabilizer (with or without an antipsychotic); fiscal-year 1997 cohort.

Figure 2c. Predicted probability of filling a prescription for antipsychotic monotherapy (i.e., without mood stabilizer); fiscal-year 2000 cohort.

Figure 2d. Predicted probability of filling a prescription for antipsychotic monotherapy (i.e., without mood stabilizer); fiscal-year 1997 cohort.

Discussion

While we observed shortfalls in bipolar disorder treatment quality independent of race/ethnicity (at best, no more than 60% of the person-quarters included any antimanic medication between fiscal-years 1997 and 2004), we also observed racial/ethnic disparities in filling prescriptions for antimanic medications. As in prior research, compared to whites, we found disparities for blacks, and unlike most prior literature, no statistically significant disparities for Hispanics.1, 2, 6, 9, 31–34 We found no change in the trends in disparities over time, however. Prior research on changing trends in mental health treatment disparities has been mixed, with some studies indicating no change in the black-white disparities trends when they exist at baseline2, 6, 31 and others showing Hispanic-white disparities worsening over time.2, 6, 31 We found limited evidence of the substitution of antispychotics for mood stabilizers, although less so for blacks.

We found statistically significant disparities for blacks but not Hispanics. Several possible explanations may account for our results. First, clinical characteristics unobservable in claims may account for our findings: blacks with bipolar disorder may be more likely to experience psychosis and have more manic episodes33, 35 compared to whites, whereas Hispanics and whites may be similar regarding these characteristics.33 However, this would not explain why we found blacks were less likely to utilize mood stabilizers but similarly likely to use antipsychotic monotherapy, compared to whites. Alternatively, there may be regional differences in access to higher quality mental health care or in training of clinicians.

Finally, it is possible that observed racial/ethnic differences reflect patient choice.36, 37 Two-thirds to three-quarters of these patients received an antimanic agent at some point over our study period (Table 1). When contrasted with the adjusted quarter-level results, this suggests that higher proportions of patients filled antimanic medication prescriptions at some point than remained on them—raising the possibility of racial/ethnic differences in adherence to treatment recommendations. However, while there is evidence of racial/ethnic disparities in psychotropic adherence, the literature overall suggests that when there were differences, it was Hispanics, not blacks, who were less likely to be adherent than whites. Also, that racial/ethnic differences were associated with differential barriers to quality care.38 Thus differential adherence among racial/ethnic groups does not preclude problems in treatment quality.

Independent of race/ethnicity we observed cohort differences in any antimanic, and specific type of antimanic, prescription fill trends over time. Possibly, this is because we observed the 1997 cohort for eight years and the 2000 cohort for only four. Perhaps, the different trajectories represent differences related to longer periods of clinical follow-up; longer follow up may be associated with increased antimanic medication use. Or, these cohort differences may represent secular time or cohort trends.

Our results differ from Depp et al. 15 There are several possible explanations for this, some of which may be due to differences in definitions and methods described earlier. Further, both studies broadly defined racial/ethnic minorities as —black or —Hispanic, combining American-born blacks with those of Caribbean descent, and —Hispanics of Cuban descent with Puerto Ricans and other Hispanics. Although we cannot disaggregate these subgroups in administrative data, treatment patterns differ in some cases across these subgroups.39, 40 San Diego and Florida likely have different compositions of minority subgroups, which also could account for the observed different prescription patterns.

There are several limitations worth noting. Diagnosis and race/ethnicity were ascertained through claims data. However, while the gold standard for diagnostic accuracy are structured clinical interviews or chart review, claims data have demonstrated validity for identifying patients with bipolar disorder.19 Also, while some have raised concerns about the accuracy of administrative data in conducting analyses on race and ethnicity, misclassification in administrative data does not seem to appreciably bias estimates of racial/ethnic treatment utilization for blacks, whites and Hispanics (even when examined in the Florida Medicaid program)24, 41, 42 and therefore are reasonable to utilize when measuring treatment disparities.8 However, an additional limitation of this study (indeed all Medicaid claims studies examining disparities that predate 1999 when the SSA corrected their race/ethnicity data categories), is that prior to 1999, Hispanics who entered this Medicaid program through the SSA, were classified as “Other”. We have accounted for this in the analysis by separating the population into cohorts, determined by the year an individual enrollee entered the bipolar cohort, and by selecting a cohort year after 1999 to highlight in the analyses. Notably, there were no differences in Hispanic-white disparity trends in any of the cohorts (as evidenced by the time trends analyses)—either before or after the year in which the SSA changed their racial/ethnic categories.

While we found overall quality problems independent of race/ethnicity, we also found racial/ethnic disparities—particularly for blacks. From a research and policy perspective, disaggregating the contributing factors for disparities in antimanic medication utilization is an important next step in improving overall bipolar disorder treatment quality, as well eliminating disparities. Clearly, clinical and policy efforts are needed to improve overall pharmacotherapy quality for bipolar disorder. Some evidence suggests that improving overall quality can disproportionately improve care for racial/ethnic minorities11. Further, targeted efforts may be needed to improve pharmacotherapy for black patients in this population.

Appendix 1a.

Logistic Regression Full Model Results Likelihood of Receiving Any Antimanic Medication or Not (N=126,413 records, n=13,497 Patients)

| Any antimanic medication (reference = no antimanic medication) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Estimate | Standard Error | 95% Confidence Limits | Z | Pr > |Z| | |

| Intercept | 0.4587 | 0.0708 | 0.3198 | 0.5975 | 6.48 | <.0001 |

| Quarter | −0.1059 | 0.0068 | −0.1193 | −0.0925 | −15.51 | <.0001 |

| Quarter2 | 0.0029 | 0.0002 | 0.0025 | 0.0033 | 15.06 | <.0001 |

| Race/Ethnicity (reference = White) | ||||||

| Black | −0.5050 | 0.1364 | −0.7722 | −0.2377 | −3.70 | 0.0002 |

| Hispanic | −0.3408 | 0.1713 | −0.6765 | −0.0050 | −1.99 | 0.0467 |

| Quarter*Black | −0.0047 | 0.0053 | −0.0151 | 0.0058 | −0.87 | 0.3830 |

| Quarter*Hispanic | 0.0066 | 0.0060 | −0.0053 | 0.0184 | 1.09 | 0.2757 |

| Female | −0.1800 | 0.0333 | −0.2452 | −0.1148 | −5.41 | <.0001 |

| Age (centered at 40) | 0.0139 | 0.0014 | 0.0111 | 0.0167 | 9.82 | <.0001 |

| Age2 (centered at 40) | −0.0004 | 0.0001 | −0.0006 | −0.0002 | −4.39 | <.0001 |

| Medicaid Eligibility (reference = Medicare) | ||||||

| Supplemental Security Income | −0.1001 | 0.0600 | −0.2177 | 0.0175 | −1.67 | 0.0952 |

| AFDC/Pregnant women/Family Planning | −0.2968 | 0.0760 | −0.4458 | −0.1478 | −3.90 | <.0001 |

| Other (Not Medicaid Eligible, General Assistance, Medically Needy, HMO Ineligible) | −0.5236 | 0.0904 | −0.7008 | −0.3465 | −5.79 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Supplemental Security Income | −0.0065 | 0.0028 | −0.0121 | −0.0009 | −2.28 | 0.0226 |

| Quarter*AFDC/Pregnant women/Family Planning | −0.0223 | 0.0035 | −0.0291 | −0.0154 | −6.34 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Other (Not Medicaid Eligible, General Assistance, Medically Needy, HMO Ineligible) | 0.0116 | 0.0040 | 0.0038 | 0.0193 | 2.93 | 0.0034 |

| Months in Quarter Eligible and in Bipolar Cohort (reference = 1 month) | ||||||

| 2 months | 0.3671 | 0.0281 | 0.3121 | 0.4222 | 13.07 | <.0001 |

| 3 months | 0.4911 | 0.0227 | 0.4465 | 0.5356 | 21.62 | <.0001 |

| Medical/Psychiatric Conditions That May Influence Prescribing | ||||||

| Substance Use Disorder | 0.0395 | 0.0297 | −0.0188 | 0.0978 | 1.33 | 0.1842 |

| Increase Mood Stabilizer or Antipsychotic | 0.3798 | 0.0658 | 0.2508 | 0.5087 | 5.77 | <.0001 |

| Decrease Mood Stabilizer or Antipsychotic | 0.0787 | 0.0202 | 0.0390 | 0.1183 | 3.89 | 0.0001 |

| Cohort Year (reference = FY1997) | ||||||

| Cohort FY1998 | 0.3231 | 0.0781 | 0.1701 | 0.4762 | 4.14 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY1999 | 0.7860 | 0.0966 | 0.5967 | 0.9754 | 8.13 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2000 | 1.5250 | 0.1255 | 1.2790 | 1.7710 | 12.15 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2001 | 2.0392 | 0.1668 | 1.7124 | 2.3661 | 12.23 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2002 | 3.0978 | 0.2297 | 2.6476 | 3.5479 | 13.49 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2003 | 5.2000 | 0.3979 | 4.4201 | 5.9800 | 13.07 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2004 | 5.1000 | 1.1558 | 2.8347 | 7.3654 | 4.41 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY1998 | −0.0151 | 0.0044 | −0.0236 | −0.0065 | −3.46 | 0.0005 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY1999 | −0.0242 | 0.0050 | −0.0340 | −0.0145 | −4.86 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2000 | −0.0511 | 0.0059 | −0.0628 | −0.0395 | −8.60 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2001 | −0.0670 | 0.0072 | −0.0811 | −0.0528 | −9.26 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2002 | −0.0980 | 0.0092 | −0.1160 | −0.0799 | −10.63 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2003 | −0.1642 | 0.0146 | −0.1928 | −0.1357 | −11.27 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2004 | −0.1477 | 0.0386 | −0.2233 | −0.0720 | −3.82 | 0.0001 |

| Cohort FY1997*Black | 0.4327 | 0.1896 | 0.0611 | 0.8043 | 2.28 | 0.0225 |

| Cohort FY1998*Black | 0.1624 | 0.1917 | −0.2134 | 0.5382 | 0.85 | 0.3969 |

| Cohort FY1999*Black | −0.0177 | 0.1991 | −0.4080 | 0.3725 | −0.09 | 0.9291 |

| Cohort FY2000*Black | 0.1491 | 0.2036 | −0.2500 | 0.5482 | 0.73 | 0.4640 |

| Cohort FY2001*Black | 0.3786 | 0.2083 | −0.0296 | 0.7868 | 1.82 | 0.0691 |

| Cohort FY2002*Black | 0.0411 | 0.2117 | −0.3738 | 0.4560 | 0.19 | 0.8461 |

| Cohort FY2003*Black | 0.2388 | 0.2664 | −0.2834 | 0.7610 | 0.90 | 0.3701 |

| Cohort FY1997*Hispanic | −0.0159 | 0.2308 | −0.4684 | 0.4365 | −0.07 | 0.9449 |

| Cohort FY1998*Hispanic | −0.2662 | 0.2182 | −0.6939 | 0.1614 | −1.22 | 0.2224 |

| Cohort FY1999*Hispanic | 0.1279 | 0.2227 | −0.3086 | 0.5644 | 0.57 | 0.5658 |

| Cohort FY2000*Hispanic | 0.4742 | 0.2254 | 0.0325 | 0.9159 | 2.10 | 0.0354 |

| Cohort FY 2001*Hispanic | 0.6750 | 0.2268 | 0.2305 | 1.1194 | 2.98 | 0.0029 |

| Cohort FY 2002*Hispanic | 0.3323 | 0.2461 | −0.1500 | 0.8147 | 1.35 | 0.1769 |

| Cohort FY 2003*Hispanic | 0.4154 | 0.2753 | −0.1242 | 0.9550 | 1.51 | 0.1313 |

Appendix 1b.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Full Model Results Likelihood of Receiving A Mood Stabilizer (with or without an antipsychotic), Antipsychotic Monotherapy, or Neither (N=126,413 records, n=13,497 Patients)

| Medication categories: 1=Mood Stabilizer, 2=Antipsychotic Alone (reference = neither mood stabilizer nor antipsychotic) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Medication | DF | Estimate | Standard Error | Wald Chi-Square | Pr > Chi Sq |

| Intercept | 1 | 1 | 0.2728 | 0.0848 | 10.3518 | 0.0013 |

| Intercept | 2 | 1 | −2.0772 | 0.1326 | 245.2700 | <.0001 |

| Quarter | 1 | 1 | −0.1070 | 0.00807 | 176.0592 | <.0001 |

| Quarter | 2 | 1 | 0.0172 | 0.0108 | 2.5301 | 0.1117 |

| Quarter2 | 1 | 1 | 0.00249 | 0.000222 | 124.9994 | <.0001 |

| Quarter2 | 2 | 1 | 0.000221 | 0.000286 | 0.6004 | 0.4384 |

| Race/Ethnicity (reference = White) | ||||||

| Black | 1 | 1 | −0.6946 | 0.1634 | 18.0654 | <.0001 |

| Black | 2 | 1 | −0.0300 | 0.2549 | 0.0139 | 0.9062 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 1 | −0.4668 | 0.2296 | 4.1348 | 0.0420 |

| Hispanic | 2 | 1 | 0.3827 | 0.2438 | 2.4632 | 0.1165 |

| Quarter*Black | 1 | 1 | 0.00429 | 0.00737 | 0.3387 | 0.5606 |

| Quarter*Black | 2 | 1 | −0.0171 | 0.00807 | 4.4621 | 0.0347 |

| Quarter*Hispanic | 1 | 1 | 0.00408 | 0.00842 | 0.2347 | 0.6281 |

| Quarter*Hispanic | 2 | 1 | −0.00897 | 0.00843 | 1.1327 | 0.2872 |

| Female | 1 | 1 | −0.1647 | 0.0447 | 13.5853 | 0.0002 |

| Female | 2 | 1 | −0.0241 | 0.0503 | 0.2300 | 0.6315 |

| Age (centered at 40) | 1 | 1 | 0.00591 | 0.00194 | 9.2676 | 0.0023 |

| Age (centered at 40) | 2 | 1 | 0.0151 | 0.00212 | 50.6425 | <.0001 |

| Age2 (centered at 40) | 1 | 1 | −0.00075 | 0.000135 | 30.5183 | <.0001 |

| Age2 (centered at 40) | 2 | 1 | −0.00070 | 0.000153 | 20.5825 | <.0001 |

| Medicaid Eligibility (reference = Medicare) | ||||||

| Supplemental Security Income | 1 | 1 | −0.1533 | 0.0828 | 3.4285 | 0.0641 |

| Supplemental Security Income | 2 | 1 | −0.1209 | 0.1195 | 1.0248 | 0.3114 |

| AFDC/Pregnant women/Family Planning | 1 | 1 | −0.9481 | 0.1003 | 89.3065 | <.0001 |

| AFDC/Pregnant women/Family Planning | 2 | 1 | −1.3419 | 0.1580 | 72.1764 | <.0001 |

| Other (Not Medicaid Eligible, General Assistance, Medically Needy, HMO Ineligible) | 1 | 1 | −0.2298 | 0.1414 | 2.6430 | 0.1040 |

| Other (Not Medicaid Eligible, General Assistance, Medically Needy, HMO Ineligible) | 2 | 1 | 0.00641 | 0.1858 | 0.0012 | 0.9725 |

| Quarter*Supplemental Security Income | 1 | 1 | −0.0119 | 0.00383 | 9.7249 | 0.0018 |

| Quarter*Supplemental Security Income | 2 | 1 | −0.00467 | 0.00510 | 0.8385 | 0.3598 |

| Quarter*AFDC/Pregnant women/Family Planning | 1 | 1 | −0.0144 | 0.00480 | 8.9915 | 0.0027 |

| Quarter*AFDC/Pregnant women/Family Planning | 2 | 1 | 0.00822 | 0.00685 | 1.4436 | 0.2296 |

| Quarter*Other (Not Medicaid Eligible, General Assistance, Medically Needy, HMO Ineligible) | 1 | 1 | 0.0126 | 0.00588 | 4.5777 | 0.0324 |

| Quarter*Other (Not Medicaid Eligible, General Assistance, Medically Needy, HMO Ineligible) | 2 | 1 | 0.00434 | 0.00740 | 0.3441 | 0.5575 |

| Months in Quarter Eligible and in Bipolar Cohort (reference = 1 month) | ||||||

| 2 months | 1 | 1 | 0.4949 | 0.0391 | 160.3282 | <.0001 |

| 2 months | 2 | 1 | 0.4706 | 0.0494 | 90.7092 | <.0001 |

| 3 months | 1 | 1 | 0.7455 | 0.0327 | 519.9657 | <.0001 |

| 3 months | 2 | 1 | 0.7003 | 0.0405 | 299.3050 | <.0001 |

| Substance Use Disorder | 1 | 1 | −0.2002 | 0.0458 | 19.1193 | <.0001 |

| Substance Use Disorder | 2 | 1 | 0.00569 | 0.0477 | 0.0142 | 0.9052 |

| Medical/Psychiatric Conditions That May Influence Prescribing | ||||||

| Increase Mood Stabilizer | 1 | 1 | 0.6367 | 0.0997 | 40.7625 | <.0001 |

| Increase Mood Stabilizer | 2 | 1 | 0.0839 | 0.1205 | 0.4847 | 0.4863 |

| Decrease Mood Stabilizer | 1 | 1 | −0.1049 | 0.0388 | 7.3046 | 0.0069 |

| Decrease Mood Stabilizer | 2 | 1 | −0.0208 | 0.0430 | 0.2343 | 0.6284 |

| Decrease Antipsychotic | 1 | 1 | 0.1660 | 0.0436 | 14.5077 | 0.0001 |

| Decrease Antipsychotic | 2 | 1 | 0.2635 | 0.0466 | 32.0221 | <.0001 |

| Cohort Year (reference = FY 1997) | ||||||

| Cohort FY1998 | 1 | 1 | 0.2828 | 0.0881 | 10.3186 | 0.0013 |

| Cohort FY1998 | 2 | 1 | 0.0708 | 0.1446 | 0.2399 | 0.6242 |

| Cohort FY1999 | 1 | 1 | 0.7565 | 0.1124 | 45.3310 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY1999 | 2 | 1 | 0.4099 | 0.1587 | 6.6700 | 0.0098 |

| Cohort FY2000 | 1 | 1 | 1.1484 | 0.1428 | 64.6683 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2000 | 2 | 1 | 1.2434 | 0.1861 | 44.6408 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2001 | 1 | 1 | 1.4813 | 0.1964 | 56.8677 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2001 | 2 | 1 | 1.4258 | 0.2345 | 36.9698 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2001 | 1 | 1 | 2.0771 | 0.2715 | 58.5480 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2002 | 2 | 1 | 2.5073 | 0.3055 | 67.3396 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2003 | 1 | 1 | 3.6793 | 0.4690 | 61.5342 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2003 | 2 | 1 | 3.9577 | 0.5228 | 57.3137 | <.0001 |

| Cohort FY2004 | 1 | 1 | 0.7668 | 1.4355 | 0.2853 | 0.5932 |

| Cohort FY2004 | 2 | 1 | 0.1561 | 1.6134 | 0.0094 | 0.9229 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY1998 | 1 | 1 | −0.0129 | 0.00530 | 5.9478 | 0.0147 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY1998 | 2 | 1 | −0.00510 | 0.00698 | 0.5350 | 0.4645 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY1999 | 1 | 1 | −0.0235 | 0.00620 | 14.3621 | 0.0002 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY1999 | 2 | 1 | −0.00589 | 0.00740 | 0.6339 | 0.4259 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2000 | 1 | 1 | −0.0336 | 0.00701 | 22.9744 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2000 | 2 | 1 | −0.0394 | 0.00838 | 22.0904 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2001 | 1 | 1 | −0.0455 | 0.00875 | 27.0159 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2001 | 2 | 1 | −0.0398 | 0.00996 | 15.9428 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2002 | 1 | 1 | −0.0578 | 0.0110 | 27.4101 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2002 | 2 | 1 | −0.0751 | 0.0122 | 37.8360 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2003 | 1 | 1 | −0.1109 | 0.0172 | 41.3458 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2003 | 2 | 1 | −0.1166 | 0.0192 | 36.6953 | <.0001 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2004 | 1 | 1 | 0.00186 | 0.0480 | 0.0015 | 0.9691 |

| Quarter*Cohort FY2004 | 2 | 1 | 0.0196 | 0.0538 | 0.1330 | 0.7153 |

| Cohort FY1998*Black | 1 | 1 | 0.4101 | 0.2512 | 2.6640 | 0.1026 |

| Cohort FY1998*Black | 2 | 1 | 0.2951 | 0.3016 | 0.9572 | 0.3279 |

| Cohort FY1999*Black | 1 | 1 | 0.0782 | 0.2588 | 0.0913 | 0.7626 |

| Cohort FY1999*Black | 2 | 1 | 0.1416 | 0.3108 | 0.2077 | 0.6486 |

| Cohort FY2000*Black | 1 | 1 | −0.3465 | 0.2904 | 1.4243 | 0.2327 |

| Cohort FY2000*Black | 2 | 1 | 0.1121 | 0.3102 | 0.1305 | 0.7179 |

| Cohort FY2001*Black | 1 | 1 | −0.1646 | 0.2926 | 0.3165 | 0.5737 |

| Cohort FY2001*Black | 2 | 1 | 0.1517 | 0.3070 | 0.2442 | 0.6212 |

| Cohort FY2002*Black | 1 | 1 | −0.0152 | 0.3026 | 0.0025 | 0.9600 |

| Cohort FY2002*Black | 2 | 1 | 0.6014 | 0.3063 | 3.8556 | 0.0496 |

| Cohort FY2003*Black | 1 | 1 | −0.2807 | 0.3047 | 0.8487 | 0.3569 |

| Cohort FY2003*Black | 2 | 1 | 0.0963 | 0.3120 | 0.0952 | 0.7577 |

| Cohort FY2004*Black | 1 | 1 | −0.2729 | 0.3801 | 0.5156 | 0.4727 |

| Cohort FY2004*Black | 2 | 1 | 0.4409 | 0.3645 | 1.4634 | 0.2264 |

| Cohort FY1998*Hispanic | 1 | 1 | 0.0465 | 0.3204 | 0.0210 | 0.8847 |

| Cohort FY1998*Hispanic | 2 | 1 | −0.2766 | 0.3363 | 0.6765 | 0.4108 |

| Cohort FY1999*Hispanic | 1 | 1 | −0.6683 | 0.3177 | 4.4247 | 0.0354 |

| Cohort FY1999*Hispanic | 2 | 1 | −0.1702 | 0.3121 | 0.2973 | 0.5856 |

| Cohort FY 2000*Hispanic | 1 | 1 | 0.1127 | 0.3253 | 0.1200 | 0.7291 |

| Cohort FY 2000*Hispanic | 2 | 1 | 0.0499 | 0.3106 | 0.0258 | 0.8725 |

| Cohort FY 2001*Hispanic | 1 | 1 | 0.3931 | 0.3321 | 1.4011 | 0.2365 |

| Cohort FY 2001*Hispanic | 2 | 1 | 0.5816 | 0.3113 | 3.4895 | 0.0618 |

| Cohort FY 2002*Hispanic | 1 | 1 | 0.5026 | 0.3361 | 2.2355 | 0.1349 |

| Cohort FY 2002*Hispanic | 2 | 1 | 0.7879 | 0.3130 | 6.3385 | 0.0118 |

| Cohort FY 2003*Hispanic | 1 | 1 | 0.3250 | 0.3590 | 0.8193 | 0.3654 |

| Cohort FY 2003*Hispanic | 2 | 1 | 0.2531 | 0.3342 | 0.5735 | 0.4489 |

| Cohort FY 2004*Hispanic | 1 | 1 | 0.5666 | 0.3897 | 2.1138 | 0.1460 |

| Cohort FY 2004*Hispanic | 2 | 1 | 0.0784 | 0.3712 | 0.0446 | 0.8328 |

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institute of Mental Health K01MH071714 (Dr. Busch), K01MH66109 (Dr. Huskamp), P50 MH073469 (Dr. McGuire) and R01-MH61434 (Drs. McGuire, Neelon and Normand and Mr. Manning), The MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment (Dr. McGuire), and the National Center for Minority Health and Disparities 20 MD000537 (Dr. McGuire).

References

- 1.Daumit GL, Crum RM, Guallar E, et al. Outpatient prescriptions for atypical antipsychotics for African Americans, Hispanics and Whites in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:121–128. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook BL, McGuire T, Miranda J. Measuring trends in mental health care disparities, 2000–2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(12):1533–1540. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Power NR, Steinwachs D, Eaton WW, Ford DE. Mental health service utilization by African Americans and Whites. Medical Care. 1999;37(10):1034–1045. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neighbors HW, Caldwell C, Williams DR, et al. Race, ethnicity and the use of services for mental disorders: results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:485–494. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virnig B, Huang Z, Lurie N, Musgrave D, McBean AM, Dowd B. Does Medicare managed care provide equal treatment for mental illness across races? Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004 Feb;61(2):201–205. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Change in mental health service delivery among blacks, whites, and Hispanics in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Administration & Policy in Mental Health. 2003 Sep;31(1):31–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1026096123010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Grochocinski VJ, Cluss PA, Houck PR, Stapf DA. Demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals in a bipolar case registry. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;63(2):120–125. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escarce JJ, McGuire TG. Methods for using Medicare data to compare procedure rates among Asians, blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, and whites. Health Services Research. 2003;38(5):1303–1317. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J, Noel JM, Zuckerman IH, Miller NA, Shaya FT. Disparities in access to essential new prescription drugs between non-Hispanic Whites, Non-Hispanic Blacks, and Hispanic Whites. Medical Care Res Rev. 2006;63(6):742–763. doi: 10.1177/1077558706293638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGuire T, Miranda J. New evidence regarding racial and ethnic disparities in mental health policy: policy implications. Health Affairs. 2008;27(2):393–403. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, et al. Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Services Research. 2003;38(2):613–630. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keck PE, Jr, Perlis RH, Otto MW, Carpenter D, Ross R, Docherty JP. The Expert Consensus Series: Treatment of bipolar disorder. Postgraduate Medicine. 2004:1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suppes T, Dennehy EB, Hirschfeld RMA, et al. The Texas implementation of medication algorithms: Update to the algorithms for treatment of bipolar I disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66(7):870–886. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus Statement: Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596–601. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Depp C, Ojeda VD, Mastin W, Unutzer J, Gilmer TP. Trends in use of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers among Medicaid beneficiaries with bipolar disorder, 2001–2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(10):1169–1174. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.10.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The Medicaid Analytic Extract Chartbook. In: Office of Research Development and Information MPR, ed: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CMS; 2007.

- 17.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unutzer J, Simon G, Pabiniak C, Bond K, Katon W. The treated prevalence of bipolar disorder in a large staff-model HMO. Psychiatric Services. 1998;49(8):1072–1078. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.8.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unutzer J, Simon G, Pabiniak C, Bond K, Katon W. The use of administrative data to assess quality of care for bipolar disorder in a large staff model HMO. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2000;22(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(99)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowden CL, Gitlin MJ, Keck PE, Perlis RH, Suppes T, Thase ME. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision) American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(4):1–50. Supplement. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirschfeld RM, Bowden CL, Gitlin MJ, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994 Dec;151(12 Suppl):40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domino ME, Frank RG, Rosenheck R. The diffusion of new antipsychotic medications and formulary policy. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2003;29(1):95–104. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghaemi SN, Hsu DJ, Thase ME, et al. Pharmacological treatment patterns at study entry for the first 500 STEP-BD participants. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(5):660–665. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.5.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arday SL, Arday DR, Monroe S, Zhang J. HCFA’s racial and ethnic data: Current accuracy and recent improvements. Health Care Financing Review. 2000;21(4):107–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott CG. Identifying the race or ethnicity of SSI recipients. Soc Secur Bull. 1999;62(4):9–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murrin MR. In: Tampa. Busch AB, editor. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Medical Association. Current Procedural Terminology. AMA Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed September 17, 2008];Population Estimates for States by Race and Hispanic Origin. 1996 July 1; http://www.census.gov/popest/archives/1990s/strh/srh96.txt.

- 30.U.S. Census Bureau. [September 17, 2008];State and County QuickFacts: Florida. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valenstein M, McCarthy JE, Ignacio R, Dalack GW, Stavanger T, Blow FC. Patient- and facility-level factors associated with diffusion of a new antipsychotic in the VA health system. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(1):70–76. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Managerial and environmental factors in the continuity of mental health care across institutions.[comment] Psychiatric Services. 2003;54(4):529–534. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalez JM, Thompson P, Escamilla M, et al. Treatment characteristics and illness burden among European Americans, African Americans, and Latinos int he first 2,000 patients of the systematic treatment enhancing program for bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 2007;40(1):31–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Opolka JL, Rascati KL, Brown CM, Gibson PJ. Ethnicity and prescription patterns for haloperidol, risperidone, and olanzapine. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(2):151–156. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleck DE, Hendricks WL, DeBello MP, Strakowski SM. Differential prescription of maintenance antipsychotics to African American and white patietns with new-onset bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;63(8):658–664. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miranda J, Cooper-Patrick L. Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19:120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooper LA, Gonzalez JM, Gallo JJ, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic and White primary care patients. Medical Care. 2003;41(4):479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanouette NM, Folsom DP, Sciolla A, Jeste DV. Psychotropic medication nonadherence among United States Latinos: A comprehensive literature review. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(2):157–174. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alegria M, Mulvaney-Day N, Woo M, Torres M, Gao S, Oddo V. Correlates of past-year mental health service use among Latinos: results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:76–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams DR, Haile R, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors HW, Baser R, Jackson JS. The mental health of black Caribbean immigrants: results for the National Survey of American Life. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:52–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boothroyd R, Murrin MR. personal communication. Describes validation study done in FL Medicaid data to examine potential bias in race/ethnicity reporting, comparing Medicaid data to interview. ed; 2007.

- 42.McBean AM. Medicare race and ethnicity data. Washington: National Academy of Social Insurance; 2004. [Google Scholar]