Abstract

NT69L is a neurotensin receptor agonist with antipsychotic-like activity. NT69L blocks apomorphine-induced climbing in rats with no effect on stereotypic behavior, attenuates d-amphetamine-induced hyperactivity, and blocks pharmacologically-induced disruption of prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the startle response. Repeated administration of NT69L results in tolerance to some, but not to all of its effects. Because schizophrenic patients require long term treatment, chronic (21-day) administration of NT69L was tested in PPI with comparisons to chronic haloperidol and clozapine treatment.

Sprague-Dawley rats received acute or 21 daily, subcutaneous injections of NT69L (1.0 mg/kg). On days one and 21 the NT69L injection was followed 30 min later by treatment with either saline; the dopamine agonist, d-amphetamine (5.0 mg/kg); or the serotonin 5-HT2A psychotomimetic receptor agonist [1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-2-aminopropane] DOI (0.5 mg/kg). Experiments were repeated with either haloperidol (1 mg/kg) or clozapine (20 mg/kg) in place of NT69L. Acute injection of NT69L significantly blocked d-amphetamine and DOI disruption of PPI. As with the acute injection, 21 daily administrations of NT69L also blocked d-amphetamine- and DOI-induced disruption of PPI. The data show that animals do not develop tolerance to the antipsychotic-like effects of NT69L when tested in the PPI of the startle response. The persistent efficacy of NT69L with chronic treatment provides further support for the therapeutic use of neurotensin agonists to treat schizophrenia and possibly other disorders that are characterized by PPI deficits. The modulatory role of NT69L on the dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission systems both of which are implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia is discussed.

Keywords: neurotensin, clozapine, haloperidol, tolerance, prepulse inhibition

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a life-long debilitating disease, which usually begins in early adulthood. The currently-available, typical antipsychotic drugs (APD) can control the positive manifestations of the disease, but are associated with extrapyramidal side effects (EPS). The newer, atypical APD such as clozapine provide major advances, but result in metabolic and other side effects [17]. Additionally, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study found that three-quarters of the participants stopped taking their first antipsychotic medication before the end of 18 months. Reasons such as medication not controlling the symptoms or intolerable side effects were cited for lack of compliance [34,35,53]}. Thus there is a great need for the development of new APD.

Neurotensin (NT) is an endogenous tridecapeptide neurotransmitter with potent central nervous system effects including hypothermia [6], antinociception [40], modulation of dopamine (DA) neurotransmission [20,33,41,42], and stimulation of anterior pituitary hormone secretion [37,43,45]. Additionally, NT and NT receptor agonists demonstrate antipsychotic-like activities [9,11]. NT69L, a NT agonist that can be administered peripherally [55] shows antipsychotic-like activity in various animal models predictive of efficacy in treatment of psychosis. Specifically, NT69L blocks apomorphine-induced climbing without causing catalepsy [19], attenuates amphetamine-induced hyperactivity [12], and prevents the disruption of prepulse inhibition (PPI) induced by d-amphetamine (indirect DA agonist), [1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-2-aminopropane hydrochloride] (DOI, a 5-HT2A agonist), and dizocilpine (a non-competitive NMDA antagonist)[46,48]. Repeated administration of NT69L results in tolerance to some, but not to all of the effects of NT69L [10]. Since effective pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia typically requires that patients take an antipsychotic drug (APD) indefinitely, an ideal APD should demonstrate persistent efficacy as the result of continuous administration. Thus, the chronic administration of NT69L was tested in an animal model with high predictive validity for antipsychotic drugs, namely, blockade of drug-induced disruption of PPI of the startle reflex, an operational measure of sensorimotor gating that is deficient in schizophrenic patients [13,14] . However, in addition to schizophrenia, there are other disorders that are characterized by PPI deficits. These include Huntington's disease [52], Tourette's syndrome [15], and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) [50] and might benefit in some way from NT therapy.

Our previous findings [10] showed no tolerance developing to NT69L at blocking effects of the direct DA receptor agonist apomorphine, which stimulates pre- and post-synaptic DA receptors, or blocking the indirect DA receptor agonist d-amphetamine, which releases DA and other amines and blocks DA uptake [18]. Therefore, we predicted that chronic administration of NT69L will block drug-induced disruption of PPI without the development of tolerance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Sprague-Dawley rats, n=4-52, (initial weight 220-250g) obtained from Harlan Laboratories, San Diego, were used in all experiments. The animals were housed in groups of two or three in a temperature controlled room with free access to water and food (Irridated rat diet (Teklad LH-485) from Harlan, Madison WI, USA) on a 12h:12h light/dark cycle. Animals were allowed a minimum of 7 days habituation to home cages during which time they were handled for 2 min daily as previously described [28] before experimental testing. On test days (day 1 and day 21), animals were habituated to the experimental room for 60 min prior to behavioral testing, performed between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. Primarily an acute study was conducted where animals in each group were used once. For the chronic study, in each separate group the same animals were tested on days 1 and 21. The data from the acute study and day 1 in the chronic study were averaged and presented as day 1. All animal protocols are approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Drugs

NT69L (1 mg/kg) was synthesized in the Mayo Proteomics Research Center (Rochester, MN) as previously described [23]. DOI (0.5 mg/kg), clozapine (20 mg/kg), and haloperidol (1 mg/kg) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). NT69L, DOI, and d-amphetamine (Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) were dissolved in saline (0.9% sodium chloride injection, Baxter Healthcare Cooperation, Deerfield, IL, USA); haloperidol and clozapine were dissolved in saline with ethanol and/or saline with 0.04% (v/v) acetic acid (vehicle). Doses of d-amphetamine and DOI used in this study have been previously shown consistently to disrupt PPI [48]. Additionally, similar doses of NT69L, haloperidol, and clozapine were used in previous experiments to block disruption of PPI [4,26,48]. All drugs were injected subcutaneously (s.c.). Control groups were injected with 100 μl of sterile saline or vehicle.

2.3. Behavioral testing

2.3. a. Equipment

PPI was measured using four identical startle chambers (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA). Each chamber consisted of a clear Plexiglas cylinder that rested on a Plexiglas platform inside a ventilated and illuminated enclosure housed in a sound attenuated room. A continuous background noise of 65 dB and the various acoustic stimuli were produced within each chamber by a high-frequency loudspeaker. The whole-body startle response of each animal resulted in vibrations that were transduced into analog signals by a piezoelectric unit mounted beneath the platform.

2.3. b. Test Sessions

Tests were performed as previously described [47]. The test session consisted of 5 trial types within a 15 min time period, including a 5 min acclimation to a 65 dB background noise that continued throughout the trial. Trials were: no stimulus, presented to measure baseline movements within the cylinder; pulse alone (a 120dB startle pulse for 40 ms) and; prepulse plus pulse (prepulses 4, 8, or 12 dB above background lasting 20 ms). Prepulses were presented 100 ms (onset to onset) before the pulse. All trial types were presented in pseudo-random order with an average inter-trial interval of 15 s (range 8-23 s). In addition, four pulse-alone trials were presented at the beginning and end of the session. These were not used in the calculation of prepulse inhibition. % PPI was calculated according to the formula: [1 − (startle magnitude after prepulse-pulse pair/startle magnitude after pulse only] × 100. Rats were administered 21 daily s.c. injections of NT69L (1 mg/kg), haloperidol (1 mg/kg), clozapine (20 mg/kg), saline, or vehicle. On test days, the rats were injected with NT69L, haloperidol, or clozapine and thirty minutes later they were injected s.c. with either saline or the PPI disrupting drug (d-amphetamine at 5 mg/kg or DOI at 0.5 mg/kg). Twenty minutes later the animals were placed in the startle chambers and PPI was measured.

2.4. Determination of the dose response curves for NT69L in reversing d-amphetamine- and DOI-induced disruption of PPI

Various doses (0.01 – 2 mg/kg) of NT69L were injected into different groups of rats (n≥8) followed by d-amphetamine (5 mg/kg) or DOI (0.5 mg/kg). PPI was conducted as described previously. The ED50 for NT69L in blocking d-amphetamine- or DOI- induced disruption of PPI was determined using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA).

2.5. Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed with One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test for multiple comparisons. Two-way ANOVA was used to determine the interaction between the treatment and the pulse intensities. Data analysis was done using Sigma Stat software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) with P<0.05 being considered significant.

3. Results

The % PPI for vehicle/saline group was not significantly different from the saline/saline group at day 1 (29±4 and 32±3, 49±3 and 51±3, 63±2 and 64±2 for vehicle and saline groups at 4, 8, and 12dB pulse intensities respectively), thus both group averages were used as controls. Twenty-one daily injections of saline did not alter %PPI as compared to acute injections (32±3 and 40±10, 51±3 and 51±7, 64±2 and 63±7 for acute and chronic injections at 4, 8 and 12 pulse intensities respectively). Chronic injection of haloperidol, clozapine, or NT69L did not cause any significant change in body weight gain as compared to the saline control group. All groups showed an average of 17-21 % increase in body weight at the end of the 21 days.

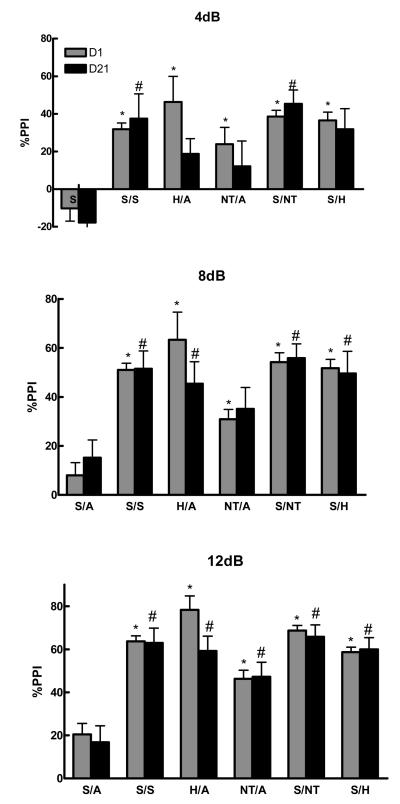

3.1. The effect of chronic injections of haloperidol and NT69L on d-amphetamine-induced disruption of PPI

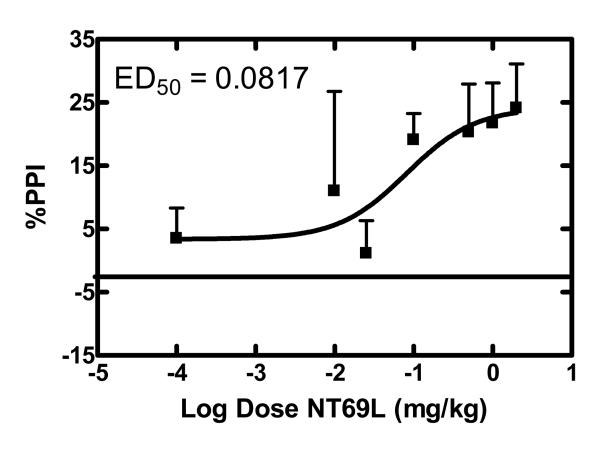

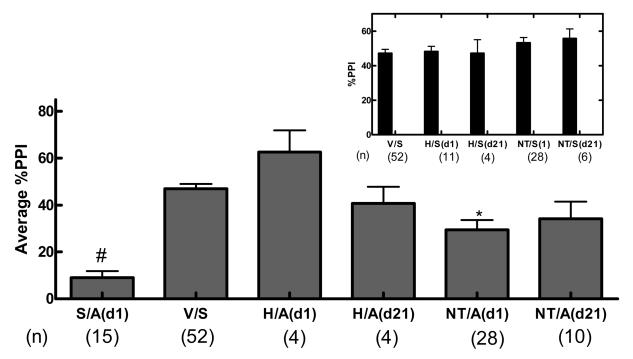

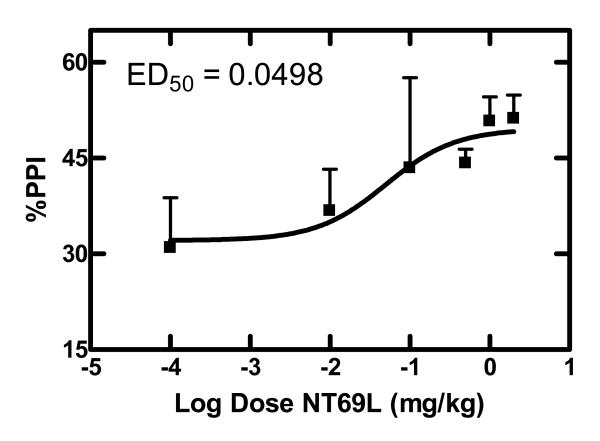

Figure 1 shows the significant effect of drug treatment (haloperidol and NT69L) in preventing the d-amphetamine-induced disruption of PPI (F 10,145 = 7.61; F 10,144 = 10.79; F 10,147 = 15.12, P<0.001) at 4, 8, and 12dB pulse intensities respectively. Comparisons among the groups show that haloperidol significantly (P=0.001) blocked d-amphetamine-induced disruption of PPI after acute and 21 daily injections (4, 8, and 12 dB). Repeated injections of haloperidol attenuated the reversal potential, when compared to acute injections. However, the difference between the acute and chronic haloperidol injections did not reach a significant level (P=0.348). Similarly, NT69L significantly blocked d-amphetamine-induced disruption of PPI after acute (4, 8, and 12dB) and 21 daily injections (12dB) (P<0.05) without causing tolerance. Two-way ANOVA shows no significant interaction between the treatment and the pulse intensity (P=0.628). Acute NT69L prevented PPI disruption caused by d-amphetamine with an ED50 of 0.08 mg/kg (Figure 2). When compared to the effect of the typical APD haloperidol, NT69L had a significantly diminished effect after acute injection, but reached a similar level of significance after 21 daily injections. Thus, repeated administration of NT69L enhanced PPI without tolerance, a result similar to that of haloperidol. The effect of NT69L on blocking d-amphetamine induced disruption of PPI was not significantly different between day 1 and day 21, although the inability to develop tolerance was shown to be significant only at 12dB. Figure 3 shows the average %PPI and the controls. One-way ANOVA shows a significant effect of treatment (F 5,111 =24.65, P<0.001) on the average %PPI. Comparisons among groups show that d-amphetamine significantly disrupted PPI as compared to all other treatments (P<0.001). Acute pretreatment with NT69L had a significantly (P<0.05) diminished effect in blocking the d-amphetamine-induced disruption of PPI as compared to acute haloperidol and chronic NT69L. There was no significant difference between the control groups [%PPI 50±2, 52±3, 56±6, 48±3 and 47±8 for vehicle/saline, NT/saline (d1), NT/saline (d21), haloperidol/saline (d1) and haloperidol/saline (d21) respectively].

Figure 1a-c.

| H=haloperidol | NT=NT69L | A=d-amphetamine |

| S=saline | V=vehicle | |

| d1=day 1 | d21=day 21 |

Figure 2.

Dose dependent effects of NT69L on amphetamine-disrupted PPI

Sprague Dawley rats (n≥8) received varying concentrations of the NT69L (0.01-2 mg/kg) and 30 min later injected with d-amphetamine (5 mg/kg). PPI was determined 20 min later as described in the text. Each point represents the mean value ± SEM. ED50 value was calculated by plotting the response vs. log [dose (mg/kg)].

Figure 3.

| H=haloperidol | NT=NT69L | A=d-amphetamine |

| S=saline | V=vehicle | |

| d1=day 1 | d21=day 21 |

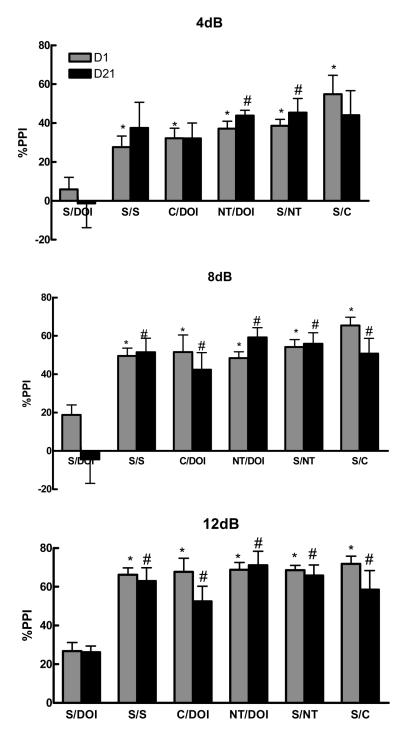

3.2. The effect of chronic injections of clozapine and NT69L on DOI-induced disruption of PPI

Figure 4 shows the significant effect of drug treatment in blocking the DOI-induced disruption of PPI (F 10,109 = 5.43, F 10,106 = 7.38, F 10,115 = 12.43, P<0.001) at 4, 8, and 12 dB pulse intensities respectively. Comparisons among the groups show that clozapine and NT69L significantly (P=0.001) blocked DOI-induced disruption of PPI after acute (4, 8, and 12 dB) and 21 daily injections (4, 8, and 12 dB for clozapine and 8 and 12 dB for NT69L). Two-way ANOVA shows no significant interaction between treatment and the pulse intensity (P=0.37).

Figure 4a-c.

| NT=NT69L | C=clozapine |

| S=saline | V=vehicle |

| d1=day 1 | d21=day 21 |

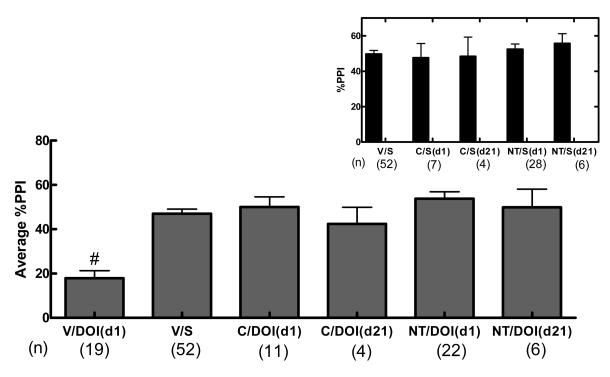

Acute NT69L blocked PPI disruption caused by DOI with an ED50 of 0.05 mg/kg (Figure 5). Average %PPI and controls are shown in Figure 6. One-way ANOVA shows a significant effect of treatment (F 5,108 =14.37, P<0.001) on the average %PPI. Comparisons among groups show that DOI significantly disrupted PPI when compared to all other treatments (P<0.001). There was no significant difference between NT69L or clozapine treatments. There was no difference between the control groups [%PPI 50±2, 52±3, 56±6, 48±8, and 50±10 for vehicle/saline, NT/saline (d1), NT/saline (d21), clozapine/saline (d1) and clozapine/saline (d21) respectively]. Animals did not develop tolerance to repeated administration of either clozapine or NT69L.

Figure 5.

Dose dependent effects of NT69L on DOI-disrupted PPI

Sprague Dawley rats (n≥8) received varying concentrations of the NT69L (0.01-2 mg/kg) and 30 min later injected with DOI (0.5 mg/kg). PPI was determined 20 min later as described in the text. Each point represents the mean value ± SEM. ED50 value was calculated by plotting the response vs. log [dose (mg/kg)].

Figure 6.

| NT=NT69L | C=clozapine |

| S=saline | V=vehicle |

| d1=day 1 | d21=day 21 |

4. Discussion

Most animal models that are predictive of antipsychotic effects of drugs are based upon findings from studies using only a single administration of the test compound. In some cases where chronic administration has been tested, efficacy demonstrated with acute administration of an established antipsychotic is not exhibited after chronic administration [3,56]. Nonetheless, patients are treated chronically with antipsychotic drugs. Therefore, it is important to investigate the chronic as well as the acute effects of potential APD in putative animal models that are predictive of antipsychotic efficacy to determine whether tolerance occurs. In general, patients do not develop tolerance to the currently available APD, which are largely thought to exert their therapeutic effects as receptor antagonists. The interest in investigating tolerance in the present study pertains mainly to the effects of the NT analogs, which as receptor agonists are more likely than receptor antagonists to show tolerance. These NT compounds have antipsychotic-like effects and have therapeutic potential for the treatment of schizophrenia.

Indeed, many studies have provided evidence suggesting that NT analogs have antipsychotic-like properties [9]. Previous studies by our group demonstrated that one of our NT agonists, NT69L, behaves like APD in various animal models that are predictive of antipsychotic properties, such as blockade of apomorphine-induced climbing and of d-amphetamine-induced hyperactivity without causing catalepsy, an indication of the propensity to cause EPS [8,19]. In addition to the above mentioned animal models, NT69L blocked pharmacologically-induced disruption of PPI, a result that is highly predictive of its antipsychotic properties. Acute NT69L potently blocked PPI disruption caused by d-amphetamine and DOI with an ED50 of 0.08 and 0.05 mg/kg, respectively, similar to previous studies [47]. DA neurotransmission is involved in the modulation of PPI [60]. The ability of NT69L to block d-amphetamine-induced disruption of PPI suggests that it might involve changes in presynaptic dopaminergic cells making them less sensitive to DA-releasing actions of d-amphetamine (see [5] for review on NT-dopamine interactions). Thus, the modulatory effect of NT69L on dopaminergic function may play an important role in its antipsychotic-like effect.

Our acute results are in contrast with a previous study by Secchi et al., 2009 who reported that NT69L did not reverse d-amphetamine-induced disruption of PPI. The differential effect could be due to differences in the PPI parameters (pulse intensities and inter-trial intervals). Another explanation for the differences in the PPI-disruptive effects of d-amphetamine could be due to differences in the strain of animals used or vendors [51]. Both animal strain and vendor can influence the effects of dopaminergic drugs [46]. Although the present study used the same strain (Sprague-Dawley) and from the same vendor (Harlan), the animals used in the Secchi study were provided from a barrier room in the Austin Texas facility. The authors of that study postulated that the rats might have exhibited less sensitivity to the effects of d-amphetamine due to their genetic isolation and subsequent breeding, while our animals were provided from the San Diego facility in California. Interestingly, our results for the acute injection are in agreement with [48] and [27] who used Sprague-Dawley rats from the San Diego facility.

In the present study, the effects of the drugs (d-amphetamine, NT69L, DOI, and clozapine) on PPI and the startle response do not appear to be correlated as previously reported [4]. For example, although d-amphetamine has motor stimulatory effects, its effect on the startle response was not different from the saline control group and resulted in disruption of %PPI. Additionally, the effect on the startle response did not contribute significantly to the effect on %PPI, since NT69L decreased the startle amplitude in saline treated rats (Table 1), but produced no appreciable change in the PPI of these rats (Figure 3 inset). Similarly, saline/DOI and clozapine/DOI (d21) did not modify the startle response as compared to the saline control, but decreased and increased %PPI, respectively. In contrast clozapine/DOI diminished the startle response but increased the %PPI (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of treatment on pulse-alone responding

| Treatment | (n) | Startle response (Mean ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|

| Saline/saline* | (52) | 415 ± 40 |

| NT69L/saline* | (34) | 290 ± 33b |

| Saline/d-amphetamie(d1) | (15) | 610 ± 60 |

| NT69L/d-amphetamine (d1) | (28) | 220 ± 30 a,b |

| NT69L/d-amphetamine (d21) | (10) | 180 ± 40 a,b |

| Haloperidol/d-amphetamine (d1) | (4) | 280 ± 80b |

| Haloperidol/d-amphetamine (d21) | (4) | 300 ± 100 |

| Haloperidol/saline (d1) | (11) | 328 ± 38 |

| Haloperidol/saline (d21) | (4) | 392 ± 67 |

| Saline/DOI (d1) | (19) | 470 ± 50 c |

| NT69L/DOI (d1) | (12) | 330 ± 40 |

| NT69L/DOI (d21) | (6) | 250 ± 50 |

| Clozapine/DOI (d1) | (11) | 150 ± 30a |

| Clozapine/DOI (d21) | (4) | 500 ± 100c |

| Clozapine/saline (d1) | (7) | 266 ± 50 |

| Clozapine/saline (d21) | (4) | 315 ± 45 |

Effect of NT69L (1 mg/kg), haloperidol (1 mg/kg), or clozapine (20 mg/kg) on the startle response amplitude in rats given s.c. injections of saline, the indirect dopamine agonist d-amphetamine or the serotonin agonist DOI.

Significantly (P<0.05) different from saline/saline.

Significantly (P<0.05) different from saline/d-amphetamine.

Significantly (P<0.05) different from clozapine/DOI (d1). (n) = number of animals.

Data is average of day 1 and day 21.

The present study is the first to investigate the effect of long term dosing of NT69L on blockade of pharmacologically-induced disruption of PPI, which serves as a screening model for identifying compounds that may be useful in the treatment of schizophrenia. With repeated administration tolerance to NT69L develops to some but not to all of its effects. Interestingly, repeated administration of NT69L results in the rapid development of tolerance (after a single dose) to its hypothermic effects, its ability to block the catalepsy caused by injection of the DA receptor antagonist haloperidol, and its effect on blood glucose levels and pituitary hormones [10]. The lack of tolerance exhibited to the reversal of d-amphetamine- or DOI-induced disruption of PPI in the present study is consistent with previous findings from our laboratory where the blocking effects of NT69L against direct (apomorphine) or indirect (d-amphetamine and cocaine) DA receptor agonists did not show tolerance after several daily injections [10]. Similarly, Feifel et al., 2008 and Hadden et al., 2005 reported lack of tolerance to the effect of a selective NT receptor 1 agonist (PD149163) and a different modified NT(8-13) peptide (KH28) in blocking amphetamine-induced hyper-locomotion [24,29]. In contrast, Hertel et al., [30,31] found that repeated administration of NT69L resulted in tolerance to its antipsychotic-like effect in blocking amphetamine-induced hyperactivity and conditioned avoidance response. The discrepancy in the results between Hertel et al. and the others [24], including our group, may be due to the difference in the dosing regimen and has been discussed in detail [24].

Chronic stimulation of neurotransmitter receptors by an agonist can lead to adaptive changes that result in decreased responsiveness or tolerance to the agonist. At the molecular level, mechanisms explaining tolerance to an agonist drug are desensitization and down-regulation of the receptors. Desensitization is thought initially to be due to decreased coupling of the receptor with second messenger systems and can be followed by a reduction in the number of ligand recognition sites (down-regulation) [44]. However, it could also result from modulating events along the neuronal effector pathways distant from the receptor system [21]. NT, and its analogs, exert their effects by activating mainly two well defined NT receptors, the high affinity, levocabastine-insensitive NT receptor (NTS1) [54,57] and the low affinity, levocabastine-sensitive receptor (NTS2) [16,38]. The different responses to the long term administration of NT69L suggest that the distinct NT receptors and their distribution might play different roles in the development of tolerance and the cellular regulation of different receptors and interaction with neurotransmitters such as DA and 5-HT [59]. Our group demonstrated that the systemic treatment of NT69L for 5 consecutive days induced down-regulation of NTS1 but not NTS2 receptors [59] and that repeated perfusion of slices from untreated animals with NT69L, caused a marked reduction in its effects on K+-evoked but not the electrically-evoked [3H]DA release [58]. Thus, tolerance to some of the effects of NT69L but not others might involve a different role for the NT receptor subtypes in mediating K+- or electrically-evoked DA release.

The effect of NT69L on the of PPI deficits caused by the 5-HT agonist DOI was similar to the atypical APD clozapine after one and 21 daily injections, indicating that the therapeutic effect of both drugs begins early and that their efficacy is persistent with chronic administration. While the present study is the first to address the chronic effect of NT69L and clozapine on DOI-induced disruption of PPI, the acute effect of NT69L on reversing DOI-induced disruption of PPI is in agreement with previous studies done on NT69L and another NT analog PD149163 [25,47].

Here we show no tolerance to repeated injections of NT69L in reversing DOI-induced disruption of PPI. In addition, this work further supports the notion that NT agonists functionally inhibit 5-HT2A-mediated modulation of the sensorimotor circuitry, since all drugs reported to antagonize PPI deficits produced by DOI exhibit strong 5-HT2A antagonism, including atypical antipsychotics such as clozapine. The mechanism of action of NT69L on the reversal of DOI-induced PPI deficits is likely to be different from the atypical antipsychotic drug clozapine. NT69L has very low affinity for 5-HT2A receptors, but NT interacts with the 5-HT system in the brain on many levels [32]. NT-containing cell bodies and NT-containing fibers and terminals [2,22,36] in addition to NT receptor binding sites and mRNA [1,7] are found in raphe nuclei. Additionally, NT receptor subtype 1 and 2 (NTS1 and NTS2) as well as 5-HT2A receptors are expressed in the ventral pallidum that has been implicated in playing an important role in mediating PPI disrupted by DOI [49]. Since all three receptors share common signal transduction pathways, i.e., phosphatidylinositol turnover [39,49], the effects of NT agonists on 5-HT2A function could occur in this signal transduction pathway in the ventral pallidum.

Haloperidol mainly acts on dopaminergic systems and clozapine acts mainly on dopaminergic and serotonergic systems. Based on the behavioral data presented here NT69L appeared to modulate both systems. Thus, we have done in vivo microdialysis to determine the effect of acute NT69L, haloperidol, and clozapine injections on changes in extracellular levels of DA and 5-HT in the striatum and prefrontal cortex, respectively (unpublished data). Acute injections of NT69L and clozapine showed similar effects on extracellular DA and 5-HT levels in the striatum and prefrontal cortex, effects that were different from haloperidol. These data provided further support for the notion that NT69L and other NT receptor agonists behave like atypical antipsychotic drugs and that these agonists modulate not only dopaminergic, but also serotonergic neurotransmission.

In conclusion, the data show that animals do not develop tolerance to the antipsychotic-like effects of NT69L after chronic treatment when tested in PPI. Additionally, although NT69L, unlike all antipsychotic drugs developed to date, does not have significant affinity for DA, 5-HT, or other monoamine receptors (unpublished data), it modulates both dopaminergic and serotonergic systems that have been implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded was NIMH grant # MH71241 and Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alexander MJ, Leeman SE. Widespread expression in adult rat forebrain of mRNA encoding high-affinity neurotensin receptor. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402:475–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen GV, Cechetto DF. Neurotensin in the lateral hypothalamic area: origin and function. Neuroscience. 1995;69:533–44. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00261-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen MP, Pouzet B. Effects of acute versus chronic treatment with typical or atypical antipsychotics on d-amphetamine-induced sensorimotor gating deficits in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:291–304. doi: 10.1007/s002130100818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auclair AL, Kleven MS, Besnard J, Depoortere R, Newman-Tancredi A. Actions of novel antipsychotic agents on apomorphine-induced PPI disruption: influence of combined serotonin 5-HT1A receptor activation and dopamine D2 receptor blockade. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1900–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binder EB, Kinkead B, Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB. Neurotensin and dopamine interactions. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:453–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bissette G, Nemeroff CB, Loosen PT, Prange AJ, Lipton MA. Hypothermia and intolerance to cold induced by intracisternal administration of the hypothalamic peptide neurotensin. Nature. 1976;262:607–9. doi: 10.1038/262607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boudin H, Grauz-Guyon A, Faure MP, Forgez P, Lhiaubet AM, Dennis M, Beaudet A, Rostene W, Pelaprat D. Immunological recognition of different forms of the neurotensin receptor in transfected cells and rat brain. Biochem J. 1995;305:277–83. doi: 10.1042/bj3050277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boules M, Fredrickson P, Richelson E. Current topics: brain penetrating neurotensin analog. Life Sci. 2003;73:2785–92. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00674-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boules M, Fredrickson P, Richelson E. Neurotensin agonists as an alternative to antipsychotics. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;14:359–69. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boules M, McMahon B, Wang R, Warrington L, Stewart J, Yerbury S, Fauq A, McCormick D, Richelson E. Selective tolerance to the hypothermic and anticataleptic effects of a neurotensin analog that crosses the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res. 2003;987:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boules M, Shaw A, Fredrickson P, Richelson E. Neurotensin agonists: potential in the treatment of schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:13–23. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boules M, Warrington L, Fauq A, McCormick D, Richelson E. A novel neurotensin analog blocks cocaine- and D-amphetamine-induced hyperactivity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;426:73–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braff D, Stone C, Callaway E, Geyer M, Glick I, Bali L. Prestimulus effects on human startle reflex in normals and schizophrenics. Psychophysiology. 1978;15:339–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1978.tb01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braff DL, Grillon C, Geyer MA. Gating and habituation of the startle reflex in schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:206–15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820030038005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castellanos FX, Fine EJ, Kaysen D, Marsh WL, Rapoport JL, Hallett M. Sensorimotor gating in boys with Tourette's syndrome and ADHD: preliminary results. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:33–41. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chalon P, Vita N, Kaghad M, Guillemot M, Bonnin J, Delpech B, Le Fur G, Ferrara P, Caput D. Molecular cloning of a levocabastine-sensitive neurotensin binding site. FEBS Lett. 1996;386:91–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Consensus R. Consenses development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:596–601. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper JR, Bloom FE, Roth RH. The biochemical basis of neuropharmacology. Oxford University Press; NY: 1996. pp. 310–343. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cusack B, Boules M, Tyler BM, Fauq A, McCormick DJ, Richelson E. Effects of a novel neurotensin peptide analog given extracranially on CNS behaviors mediated by apomorphine and haloperidol. Brain Res. 2000;856:48–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02363-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drumheller AD, Gagne MA, St-Pierre S, Jolicoeur FB. Effects of neurotensin on regional brain concentrations of dopamine, serotonin and their main metabolites. Neuropeptides. 1990;15:169–78. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(90)90150-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubuc I, Pain C, Suaudeau C, Costentin J. Tolerance to the hypothermic but not to the analgesic effect of [D-Trp11]neurotensin during the semichronic intracerebroventricular infusion of the peptide in rats. Peptides. 1994;15:303–7. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emson PC, Goedert M, Horsfield P, Rioux F, Pierre S. The regional distribution and chromatographic characterisation of neurotensin-like immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. J Neurochem. 1982;38:992–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1982.tb05340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fauq AH, Hong F, Cusack B, Tyler BM, Pang YP, Richelson E. Synthesis of (2S)-2-amino-3-(1H-4-indolyl) propanoic acid, a novel trryptophan analog for structural modification of bioactive peptides. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1998;9:4127–34. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feifel D, Melendez G, Murray RJ, Tina Tran DN, Rullan MA, Shilling PD. The reversal of amphetamine-induced locomotor activation by a selective neurotensin-1 receptor agonist does not exhibit tolerance. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;200:197–203. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1197-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feifel D, Melendez G, Shilling PD. A systemically administered neurotensin agonist blocks disruption of prepulse inhibition produced by a serotonin-2A agonist. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:651–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feifel D, Melendez G, Shilling PD. Reversal of sensorimotor gating deficits in Brattleboro rats by acute administration of clozapine and a neurotensin agonist, but not haloperidol: a potential predictive model for novel antipsychotic effects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:731–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feifel D, Reza TL, Wustrow DJ, Davis MD. Novel antipsychotic-like effects on prepulse inhibition of startle produced by a neurotensin agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:710–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geyer MA, Swerdlow NR. Measurement of startle response, prepulse inhibition, and habituation. In: Crawley JN, Gerfen CR, McKay R, Rogawski MA, Sibley DR, Skolnick P, editors. Current protocols in neuroscience. Wiley; New York: 1998. pp. 8.7.1–8.7.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadden MK, Orwig KS, Kokko KP, Mazella J, Dix TA. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of the antipsychotic potential of orally bioavailable neurotensin (8-13) analogues containing non-natural arginine and lysine residues. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:1149–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hertel P, Byskov L, Didriksen M, Arnt J. Induction of tolerance to the suppressant effect of the neurotensin analogue NT69L on amphetamine-induced hyperactivity. Eur J Pharm. 2001;422:77–81. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hertel P, Olsen CK, Arnt J. Repeated administration of the neurotensin analogue NT69L induces tolerance to its suppressant effect on conditioned avoidance behaviour. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;439:107–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jolas T, Aghajanian GK. Neurotensin and the serotonergic system. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;52:455–68. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinkead B, Binder EB, Nemeroff CB. Does neurotensin mediate the effects of antipsychotic drugs? Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;46:340–51. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lieberman JA. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs. A commentary on: Cost Utility Of The Latest Antipsychotic Drugs In Schizophrenia Study (CUTLASS 1) and Clinical Antipsychotic Trials Of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1069–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lieberman JA, Koreen AR. Neurochemistry and neuroendocrinology of schizophrenia: a selective review. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19:371–429. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mai JK, Triepel J, Metz J. Neurotensin in the human brain. Neuroscience. 1987;22:499–524. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malendowicz LK, Miskowiak B. Effects of prolonged administration of neurotensin, arginine-vasopressin, NPY, and bombesin on blood TSH, T3 and T4 levels in the rat. In Vivo. 1990;4:259–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazella J, Botto JM, Guillemare E, Coppola T, Sarret P, Vincent JP. Structure, functional expression, and cerebral localization of the levocabastine-sensitive neurotensin/neuromedin N receptor from mouse brain. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5613–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05613.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morilak DA, Garlow SJ, Ciaranello RD. Immunocytochemical localization and description of neurons expressing serotonin2 receptors in the rat brain. Neuroscience. 1993;54:701–17. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nemeroff CB, Bissette G, Prange AJ, Loosen PT, Barlow TS, Lipton MA. Neurotensin: central nervous system effects of a hypothalamic peptide. Brain Res. 1977;128:485–96. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90173-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nemeroff CB, Hernandez DE, Luttinger D, Kalivas PW, Prange AJ. Interactions of neurotensin with brain dopamine systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;400:330–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb31579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nemeroff CB, Levant B, Myers B, Bissette G. Neurotensin, antipsychotic drugs, and schizophrenia. Basic and clinical studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;668:146–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb27346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicot A, Rowe WB, De Kloet ER, Betancur C, Jessop DS, Lightman SL, Quirion R, Rostene W, Berod A. Endogenous neurotensin regulates hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and peptidergic neurons in the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. J Neuroendocrinol. 1997;9:263–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1997.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rang HP, Dale MM, Ritter JM, Gardner P. Pharmacology. Elsevier Science Limited; Churchill Livingstone: 2003. pp. 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rowe W, Viau V, Meaney MJ, Quirion R. Central administration of neurotensin stimulates hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity. The paraventricular CRF neuron as a critical site of action. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;668:365–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb27378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Secchi RL, Sung E, Hedley LR, Button D, Schreiber R. The neurotensin agonist NT69L improves sensorimotor gating deficits in rats induced by a glutamatergic antagonist but not by dopaminergic agonists. Behavioral Brain Research. 2009;202:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shilling PD, M G, Priebe K, Richelson E, Feifel D. Neurotensin agonists block the prepulse inhibition deficits produced by a 5-HT(2A) and an alpha(1) agonist. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;175:353–59. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1835-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shilling PD, Richelson E, Feifel D. The effects of systemic NT69L, a neurotensin agonist, on baseline and drug-disrupted prepulse inhibition. Behavioural Brain Research. 2003;143:7–14. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sipes TE, Geyer MA. DOI disrupts prepulse inhibition of startle in rats via 5-HT2A receptors in the ventral pallidum. Brain Res. 1997;761:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00316-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swerdlow NR, Benbow CH, Zisook S, Geyer MA, Braff DL. A preliminary assessment of sensorimotor gating in patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;33:298–301. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA. Using an animal model of deficient sensorimotor gating to study the pathophysiology and new treatments of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:285–301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swerdlow NR, Paulsen J, Braff DL, Butters N, Geyer MA, Swenson MR. Impaired prepulse inhibition of acoustic and tactile startle response in patients with Huntington's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58:192–200. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.2.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tamminga CA. Practical Treatment Information for Schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:563–65. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanaka K, Masu M, Nakanishi S. Structure and functional expression of the cloned rat neurotensin receptor. Neuron. 1990;4:847–54. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tyler-McMahon BM, Stewart JA, Farinas F, McCormick DJ, Richelson E. Highly potent neurotensin analog that causes hypothermia and antinociception. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2000;390:107–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ungerstedt U, Ljungberg T. Behavioral patterns related to dopamine neurotransmission: effect of acute and chronic antipsychotic drugs. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1977;16:193–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vita N, Laurent P, Lefort S, Chalon P, Dumont X, Kaghad M, Gully D, Le Fur G, Ferrara P, Caput D. Cloning and expression of a complementary DNA encoding a high affinity human neurotensin receptor. FEBS Lett. 1993;317:39–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81509-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang R, Boules M, Tiner W, Richelson E. Effects of repeated injections of the neurotensin analog NT69L on dopamine release and uptake in rat striatum in vitro. Brain Res. 2004;1025:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang R, Boules M, Gollatz E, Williams K, Tiner W, Richelson E. Effects of 5 daily injections of the neurotensin-mimetic NT69L on the expression of neurotensin receptors in rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;138:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang J, Forkstam C, Engel JA, Svensson L. Role of dopamine in prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;149:181–8. doi: 10.1007/s002130000369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]