Abstract

Objective

To determine the effectiveness of planned short hospital stays versus standard care for people with serious mental illness.

Design

Systematic review of all randomised controlled trials comparing planned short hospital stay versus long hospital stay or standard care for people with serious mental illness.

Subjects

Four trials enrolled 628 patients.

Main outcomes measures

Relapse; readmission; death (suicides and all causes); violent incidents (self, others, property); lost to follow up; premature discharge; delayed discharge; mental state (not improved); social functioning; patient satisfaction, quality of life, self esteem, and psychological wellbeing; family burden; imprisonment; employment status; independent living; total cost of care; and average length of hospital stay.

Results

Patients allocated to planned short hospital stays had no more readmissions (in four trials, odds ratio 0.93, 95% confidence interval 0.66 to 1.29 with no heterogeneity between trials), no more losses to follow up (in three trials of 404 patients, 1.09, 0.62 to 1.91 with no heterogeneity between trials), and more successful discharges on time (in three trials of 404 patients, 0.47, 0.27 to 0.85) than patients allocated long hospital stays or standard care. Some evidence showed that patients allocated planned short hospital stay were no more likely to leave hospital prematurely and had a greater chance of being employed than those allocated long hospital stay or standard care. Data on mental, social, and family outcomes could not be summated, and there were few or no data on patient satisfaction, deaths, violence, criminal behaviour, and costs.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of care in mental hospitals is important to patients, carers, and policy makers. Despite inadequacies in the data, this review suggests that planned short hospital stays do not encourage a “revolving door” pattern of care for people with serious mental illness and may be more effective than standard care. Further pragmatic trials are needed on the most effective organisation and delivery of care in mental hospitals.

Key messages

The effectiveness of care in mental hospitals is important to patients, carers, and policymakers irrespective of the quality and quantity of community care and the provision of newer psychotic drugs

Inpatient costs use around 80% of mental health resources, yet a longstanding record of poor or inadequate evidence on the organisation and delivery of hospital care was highlighted

Despite this, planned short hospital stays seem to be as successful, or more so, than standard care: patients experienced no more readmissions and no more losses to follow up and were more likely to be discharged on time than those receiving standard care

Further pragmatic trials are needed that focus on the most effective organisation and delivery of care in mental hospitals

Introduction

Many countries, including Britain, are reviewing their community care and favouring more hospital care for people with serious mental illness—after 40 years of mental hospital closures.1 Reduced length of stay in hospital is cited as one of the reasons for failure of community care2 and the emergence of “revolving door” and “new long stay” patients.3,4 Although there is some merit in the argument for closing large institutions and preventing institutionalisation,5,6 one important questions still remains: how long should a person with serious mental illness stay in hospital for optimum benefit (and least harm) both to the patient and to society? Many researchers have attempted to answer this question, but with observational studies and using outcomes that are irrelevant for today's policy makers.7

We aimed to determine the effectiveness of planned short or brief hospital stays to long hospital stay or standard care for patients with serious mental illness, extracting outcomes data from all relevant randomised controlled trials.

Methods

Search strategy

We identified relevant randomised trials (all languages) by searching several electronic databases: biological abstracts (January 1982 to May 1995); Embase (January 1980 to May 1998); Medline (January 1966 to May 1998); Psyclit (January 1974 to May 1995); Scisearch (1981 to May 1998), and the Cochrane Library (Issue 2, 1998). We conducted the search using the search strategy of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group8 combined with the phrase: short or brief, or early, near discharge, near admission, or hospital. We also inspected references of all identified studies for more studies, and results from unpublished trials were sought from key authors.

Selection of trials

The search for trials was performed independently by us. We each read the abstract of all publications and discarded irrelevant publications, to create a pool of eligible studies. These two pools of studies were merged, and all original articles were obtained. We then each separately evaluated the studies in the pool, again selecting for inclusion. We resolved any disagreement on classification by discussion.

We categorised the quality of all included trials as described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook, including how random allocation was concealed and the inclusion of participants who had been randomised.9

All the trial participants were seriously mentally ill with primary psychiatric disorders requiring hospital stay (including schizophrenia, affective disorders, severe neuroses, and personality disorders). All the trials focused on adults, excluding children, adolescents, and elderly people (over 65 years) and those with learning disabilities, organic brain disease, and drug and alcohol misuse. We assessed the two interventions of planned short hospital stay versus long hospital stay or standard care.

Data extraction and analysis

We extracted data based on the original intention to treat analysis for each trial; those lost to follow up were rated as having a poor outcome. The data were entered onto RevMan software9 such that the area to the left of the line of no effect (in the meta-analysis) indicates favourable outcome for short hospital stay (experiment group). We considered qualitative data only if they were measured by instruments published in peer reviewed journals. Data from rating scales were only used if (a) self reported or completed by an independent rater or relative, and (b) more than 50% complete. We presented binary outcomes as Peto odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals around these estimates. We tested differences between the results for heterogeneity.

We agreed outcome measures a priori to review. Principal outcomes were: readmission; death (suicides and all causes); violent incidents (self, others, property); lost to follow up; premature discharge; and delayed discharge. Other outcomes of interest were: percentage improved; mental state; social functioning; patient satisfaction, quality of life, self esteem, and psychological wellbeing; family burden; imprisonment; employment status; independent living; total cost of care; and average length of hospital stay.

Results

Results of search

The initial electronic search identified 206 citations. Fourteen studies were identified for assessment, of which four were included because they fulfilled the above criteria.4,10–22 Three excluded studies were quasirandomised trials, which were analysed and discussed separately.23–27 Seven trials were excluded as they were not randomised trials.

Of the four included randomised controlled trials, three were from the United States,4 10–22 and one from the United Kingdom,18 19 spanning 15 years from 1969 (table). Blinding of raters was not mentioned in any trial. Short hospital stays were planned from 1 week13–17 to 21-28 days.4,10–12 The average length of stay of those patients allocated to short hospital stay ranged from 10.8 days13–17 to 25.0 days.4,10–12 Short stay care included discharge planning and training for crisis resolution.4,10–12 No specific community care was described, except for day care by Hirsch et al.18,19 The duration of long hospital stays before the trial were only clearly reported in one study (90 to 120 days, mean 94 days),4,10–12 otherwise professional carers determined length of stay.

Fourteen different outcome scales, some of unknown validity, were used without any reference to SDs, and therefore could not be summated. Only one paper presented data from a continuous measure that could be extracted in dichotomous form, and this was “percentage of people improved.”4,10–12 The main drug treatment was with neuroleptics, and all trials reported similar use in patients allocated both long and short hospital stay.

Results of review

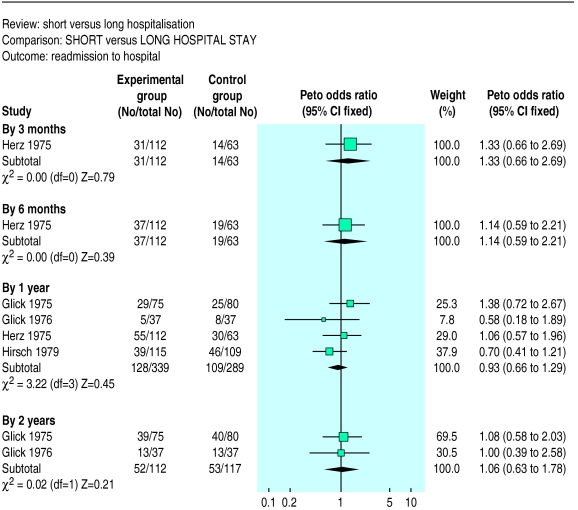

Readmissions (fig 1)

Figure 1.

Readmissions to hospital at 3 and 6 months and 1 and 2 years

—All trials reported readmission data (total of 628 patients). No difference was found between short and long hospital stay groups by 1 year (odds ratio 0.93, 95% confidence interval 0.66 to 1.29) and by 2 years (1.06, 0.63 to 1.29), with no heterogeneity between trials (χ2=3.22, df=3, P>0.25 at 1 year). Adding three quasirandomised trials to the sensitivity analysis introduced heterogeneity, due to Burhan's study27 which showed significantly fewer readmissions for those in the short hospital stay group throughout the 2 year period.

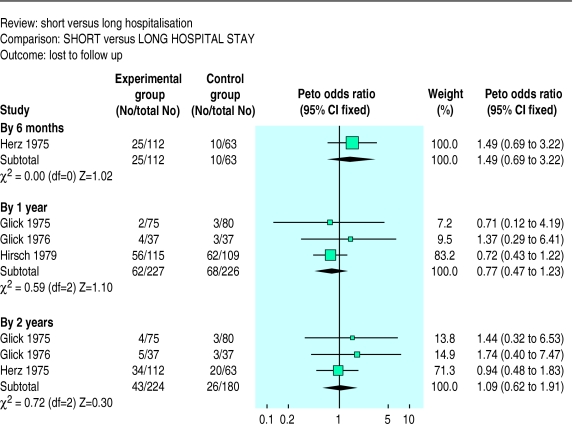

Loss to follow up (fig 2)

Figure 2.

Loss to follow up at 6 months and 1 and 2 years

—No differences were found in loss to follow up between short or long hospital stay groups at 1 and 2 years (three trials of 404 patients, 1.09, 0.62 to 1.91 with no heterogeneity at 2 years). At 1 year, just over 5% of people in both groups were lost to follow up and this rose to 14% by 2 years.

Leaving hospital prematurely

—Only two trials reported abrupt premature discharge against medical advice4 10–12 20–22; no differences were found between the groups for this outcome (0.76, 0.31 to 1.86).

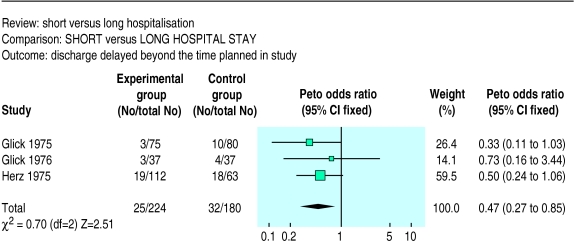

Discharge delayed beyond planned time (fig 3)

Figure 3.

Delayed discharge beyond time planned in study

—In three trials of 404 patients, significantly fewer delayed discharges were found in the short hospital stay groups compared with long hospital stay groups (0.47, 0.27 to 0.85), with no heterogeneity between trials (χ2=0.70, df=2, P> 0.5). Including data from quasirandomised trials, however, reduced this to no effect and introduced significant heterogeneity (χ2=27.45, df=4, P<0.001).

Not improved

—Only one trial reported percentages of people “not improved.”4 10–12 No differences were reported between short and long hospital stay groups as measured by two different scales. This outcome was reported in only the preliminary study, which was a subset of the larger trial.

Deaths (all causes)

—Herz et al reported three deaths in the short hospital stay group and four deaths in the long hospital stay group (0.39, 0.08 to 1.86).13–17

Employment status and independent living

—Patients from the short hospital stay groups were less likely to be unemployed at 2 years than those from the long hospital stay groups (0.34, 0.21 to 0.55, reported in two trials with 327 patients). There was, however, heterogeneity between the two trials (χ2=6.01 df=1, P<0.025).

Cost of care

—Glick et al reported costs for outpatient services only and suggested that short stay care was slightly more expensive.4,10–12

Average length of stay

—No SDs were reported for average lengths of hospital stays and therefore these could not be summated. For those allocated short hospital stays, the average length of stay ranged from 10.8 days13–17 to 25.0 days.4,10–12 The average length of long hospital stay ranged from 28 days18 19 to 94 days.4,10–12

Discussion

This review provides a timely evaluation of the evidence of effectiveness for hospital care and use of beds when many countries are reassessing their mental health policies. Although inpatient costs use about 80% of mental health resources, this review highlights a longstanding record of poor or inadequate evidence on the organisation and delivery of hospital care (in contrast with some aspects of community care).

Despite this, our review summarises important findings for new policies on modernising mental health services. Planned short hospital stays seemed to be as effective as long hospital stays for several important outcomes. Patients allocated short hospital stay experienced no more readmissions and no more losses to follow up and were more likely to be discharged on time than patients allocated long hospital stay. In addition, those allocated to short stay care had lower rates of unemployment, although these data should be interpreted with caution and warrant further investigation.

Why did short stay care seem as successful as longer stay care? Goffman's theories of institutionalisation may explain why patients allocated long hospital stay had negative results.4 He suggested that longer hospitalisation led to difficulties for patients in re-entering the “real world.” In addition, short stay care with discharge planning and a date for discharge may have provided an impetus for managed care that was both focused and coordinated compared with standard care (similar to the care provided in stroke units). Patients may also prefer short hospital stays (which may help improve engagement in treatment), although this should also be investigated.

Other important outcomes were not assessed in the original trials or could not be summated, including deaths, violence, criminal offence or imprisonment, and continuous data on mental state, social functioning, and family burden. No trial reported patient satisfaction as an outcome, possibly because these views were not considered important in the 1960s and 1970s. Economic information was also very poor and difficult to interpret. If the mean actual length of hospital stay was used as a measure of resources consumed, the average costs for short hospital stay were more than three times cheaper than those for long hospital stay, suggesting that short stay care offered the same or better outcomes for less resources.

We found that adding the three lower quality quasirandomised trials introduced heterogeneity to most outcomes, thus supporting the use of Cochrane criteria for inclusion of methodologically rigorous trials in reviews. One trial merits further discussion.27 We were concerned about the randomisation technique used, which could have led to unequal chances of being randomised into the short hospital stay group from a hospital cohort. The author, however, provided sole aftercare including counselling and continuous personal access via a telephone. Lessons could be learnt from this unusual trial, although it may not be easily replicated in practice.

Finally, planners usually assess the extent of inpatient provisions on the basis of national and international comparisons rather than on their effectiveness. Our review attempts to address this and, on the basis of limited data so far, commissioning short stay policies seem to be an appropriate use of resource irrespective of the quality and quantity of care after discharge and the provision of newer antipsychotics. Further pragmatic trials are needed to fill important gaps in knowledge, strengthen existing evidence, and allow greater generalisability to other care cultures.

Table.

Trials included in systematic review

| Trial | Method (duration) | No and description of participants (setting) | Intervention | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glick 19754 10-12 | “Random allocation,” not blind (2 years) | 155; all with schizophrenia (57% paranoid). Mean age 23, 84% single, 10% black, 85% social class 3-5 (San Francisco, USA) | Short admission: 21-28 days, early discharge plan, rapid assessment, crisis resolution, long term rehabilitation plan Standard admission: 90-120 days, assessment after 2 weeks, included psychotherapy Similar fixed drug regimens across both groups. Adjustment for higher education status, socioeconomic status, and premorbidity in long stay group reported | Readmission, days in hospital, premature discharge, mental state, health sickness rating scale, social function, patient satisfaction, family burden, employment status, economic data |

| Glick 197620-22 | “Randomly assigned,” not blind (26 months) | 74; “non-schizophrenic” including affective disorders, neuroses, and severe personality disorders (excluding drug and alcohol dependency). Mean age not known (San Francisco, USA) | Short admission: as above Standard admission: as above | As above |

| Herz 197513-17 | “Randomly assigned,” not blind (2 years) | 175; severe mental illness; 60% schizophrenic. Excluded: under 16 years, organic brain disease, concurrent medical illness, drug and alcohol misuse (New York, USA) | Short admission: 7 days’ planned discharge to day hospital or outpatient care Standard admission: length of stay determined by carers | Global function, mental state, family burden |

| Hirsch 197918 19 | “Randomly assigned,” not blind (1 year) | 224; with “functional psychiatric disorder.” Excluded: under 16 years, outside catchment, organic brain disease (London, United Kingdom) | Short admission: planned discharge less than 8 days Standard admission: discharged at carers’ discretion | Mental state, behaviour, discharge date, loss to follow up, re admission, costs |

Acknowledgments

We thank Berkshire Health Authority and Pathfinder Mental Health Services NHS Trust for permission to devote time to preparing this review.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Community care for mentally ill to be scrapped. The Times. 1998:Jul 30;4.

- 2.Department of Health. London: HMSO; 1994. Report of the inquiry into the care and treatment of Christopher Clunis. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Todd NA, Bennie EH, Carlisle JM. Some features of new long-stay male schizophrenics. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;129:424–427. doi: 10.1192/bjp.129.5.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glick ID, Hargreaves WA, Goldfield MD. Short versus long hospitalization. A prospective controlled study. I. The preliminary results of a one year follow-up of schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;30:363–369. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760090071012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goffman E. Asylums: essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. New York: Doubleday; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wing JF, Brown GW. Institutionalism and schizophrenia. London: Cambridge University Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck A, Croudace TJ, Singh S, Harrison G. The Nottingham acute bed study: alternative to acute psychiatric care. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:247–252. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams CE, Duggan L, de Jesus Mari J, White P, eds. The schizophrenia module of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. In: Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Library. Issue 2. Oxford: Update Software, 1998.

- 9.Sackett DL, editor. The Cochrane collaboration handbook. Oxford: Cochrane Collaboration; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glick ID, Hargreaves WA, Raskin M, Kutner SJ. Short vs long hospitalization. II. Results for schizophrenia in-patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1975;123:385–390. doi: 10.1176/ajp.132.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glick ID, Hargreaves WA, Drues JMA, Showstack JA. Short versus long hospitalization: a prospective controlled study. IV. One year follow-up results for schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1976;133:509–514. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hargreaves WA, Glick ID, Drues J, Showstack JA, Feigenbaum E. Short versus long hospitalisation: a prospective controlled study. VI. Two year follow-up results for schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34:305–311. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770150063007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herz MI, Endicott J, Spitzer RL. Brief hospitalization of patients with families: initial results. Am J Psychiatry. 1975;132:413–418. doi: 10.1176/ajp.132.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herz ML, Endicott J, Spitzer RL. Brief versus standard hospitalization: the families. Am J Psychiatry. 1976;133:795–801. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.7.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herz MI, Endicott J, Spitzer RL. Brief hospitalization: a two year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 1977;134:502–507. doi: 10.1176/ajp.134.5.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rebel S, Herz MI. Limitations of brief hospital treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 1976;133:518–521. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.5.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herz MI, Endicott J, Gibbon M. Brief hospitalization: two year follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:701–705. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780060091011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirsch SR, Platt S, Knights A, Weyman A. Shortening hospital stay for psychiatric care: effect on patients and their families. BMJ. 1979;1:442–446. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6161.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knights A, Hirsch SR, Platt SD. Clinical change as a function of brief admission to hospital in a controlled study using the present state examination. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;137:170–180. doi: 10.1192/bjp.137.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glick ID, Hargreaves WA, Drues JMA, Showstack JA. Short versus long hospitalization: a controlled study. III. Inpatient results for nonschizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:78–83. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770010046009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glick ID, Hargreaves WA, Drues JMA, Showstack JA. Short versus long hospitalization: a prospective controlled study. V. One year follow up for non-schizophrenics. Am J Psychiatry. 1976;133:515–517. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.5.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glick ID, Hargreaves WA, Drues JA, Showstack JA, Katzow JJ. Short versus long hospitalization: a prospective controlled study. VII. Two year follow-up results for non-schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34:314–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770150072008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caffey EM, Galbrecht CR, Klett CJ. Brief hospitalization and aftercare in the treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;24:81–86. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1971.01750070083012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosen B, Katzoff A, Carillo C, Klein DF. Clinical effectiveness of short vs long psychiatric hospitalisation. I. Inpatient results. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1316–1322. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770110044003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mattes JA, Rosen B, Klein DF. Comparison of the clinical effectivness of short versus long stay in tensive psychiatric hospitalization. II. Results of a 3-year post-hospital follow up. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1977;165:387–383. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197712000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mattes JA, Klein DF, Millan D, Rosen B. Comparison of the clinical effectiveness of ‘short’ versus ‘long’ stay psychiatric hospitalization. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1979;167:175–181. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197903000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burhan AS. Short term hospital treatment a study. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1969;20:369–370. doi: 10.1176/ps.20.12.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]