Abstract

Uniform T1-weighting is a major challenge for first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI at 3T. Previously proposed adiabatic B1-insensitive rotation (BIR-4) pulse and standard and tailored pulse trains of three non-selective pulses have been important developments but each pulse has limitations at 3T. As an extension of the tailored pulse train, we developed a hybrid pulse train by synergistically combining two non-selective rectangular RF pulses and an adiabatic half-passage pulse, in order to achieve effective saturation of magnetization within the heart, while remaining within clinically acceptable specific absorption rate (SAR) limits. The standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train were evaluated through numerical, phantom, and in vivo experiments. Among the four saturation pulses, only the hybrid pulse train yielded residual magnetization < 2% of equilibrium magnetization in the heart, while remaining within clinically acceptable SAR limits for multi-slice first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI at 3T.

Keywords: MRI, heart, cardiac perfusion, B1+ inhomogeneity, B0 inhomogeneity, T1, saturation, adiabatic pulse, SAR

Introduction

A recent study showed that the diagnostic performance of first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI is superior at 3T than at 1.5T, for the identification of both single and multiple vessel coronary artery disease (1). However, transmit radio-frequency (RF) field (B1+) variations and static magnetic field (B0) variations are comparatively higher at 3T than at 1.5T (2–6). Specifically, the peak-to-peak variation of B0 within the heart at 3T has been reported to be on the order of 130–260 Hz (3,5), and B1+ variation within the heart at 3T has been reported to be on the order of 50–80% (4,6). Increased B0 and B1 inhomogeneities make it more difficult to perform uniform T1-weighting at 3T using a conventional non-selective 90° pulse, which is known to be sensitive to both B0 and B1+ inhomogeneities (7–9).

Non-uniform T1-weighting can confound both the interpretation and quantitative analysis of first-pass cardiac perfusion MR images. Given the limitations of commercially available automated B0 shimming and RF calibration procedures for the heart, it is important to design robust saturation pulses that are insensitive to clinically relevant B0 and B1+ variations within the heart at 3T. Previously proposed adiabatic B1-insensitive rotation (BIR-4)(9,10) pulse, RF pulse train (11) of three non-selective 90° pulses (9,12), and RF pulse train of three non-selective pulses with different flip angles (e.g., 96°, 228°, 141°)(13) can be used to improve the efficacy compared with a conventional non-selective 90° pulse, but at the expense of relatively longer pulse duration and higher specific absorption rate (SAR). For convenience, the pulse train of three non-selective 90° pulses will be referred to as the standard pulse train, and the pulse train of three non-selective pulses with different flip angles will be referred to as the tailored pulse train. The longer pulse duration (10–12 ms) is inconsequential because a typical perfusion image acquisition time is on the order of 120–150 ms. While the higher SAR is not a problem for both the standard and tailored pulse trains, it is a major limitation for a BIR-4 pulse (9) that consequently reduces the slice coverage in first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI. These saturation pulses have been important developments but each has limitations for performing uniform T1-weighting in multi-slice first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI at 3T.

We have implemented these previously proposed saturation pulses on a 3T whole-body MRI system, evaluated their performances in the human heart, and discovered that these pulses do not consistently yield complete saturation of magnetization within the heart while remaining within clinically acceptable SAR limits. As an extension of the tailored pulse train (11,13), we propose to synergistically combine two non-selective rectangular RF pulses with relatively low RF energy and a non-selective adiabatic half-passage (AHP) pulse (14,15) with relatively high RF energy, in order to achieve effective saturation of magnetization within the heart, while remaining within clinically acceptable SAR limits for multi-slice (≥3), first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI at 3T. Therefore, the purposes of this study were to develop a hybrid adiabatic-rectangular pulse train that can achieve both of the aforementioned objectives at 3T and evaluate its efficacy and predicted SAR against those of the standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, and BIR-4 pulses.

Methods

Saturation Pulses

A hybrid adiabatic-rectangular RF pulse train was designed with the following three subpulses: non-selective rectangular 140° pulse, non-selective rectangular 90° pulse, and non-selective AHP pulse (Fig. 1). The two non-selective rectangular pulse angles were numerically optimized by minimizing the root-mean-square (RMS) MZR for B0 ranging from ± 130 Hz (1 Hz steps)(5) and B1+ scale ranging from 0.5 – 1.1 (0.01 steps)(6), with each non-selective rectangular pulse angle ranging from 80–200° (5° steps). The frequency sweep of the AHP pulse was ± 16.7 kHz, and its nominal B1+ calibrated by the transmit body coil was 667 Hz (14)(i.e., 49% larger than the 447 Hz frequency difference between the fat and water signal at 3T). The net effect of these subpulses is relatively strong immunity to clinically relevant B0 and B1+ variations within the heart at 3T (see Figure 2 and Figure 3 for the numerical and phantom MZR maps).

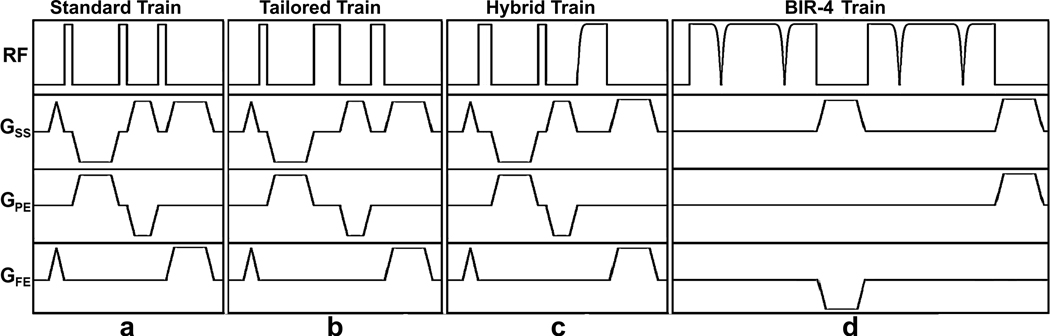

Figure 1.

Pulse sequence diagrams: (a) standard pulse train, (b) tailored pulse train, (c) hybrid pulse train, and (d) BIR-4 pulse train. The spoiler gradients are applied before and after each saturation pulse to dephase the transverse magnetization. The crusher gradients in between RF pulses are cycled to eliminate stimulated echoes. These diagrams are drawn to approximate proportions but not to exact scale. GSS: slice-select gradient; GPE: phase-encoding gradient; GFE: frequency-encoding gradient. The RF pulse characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

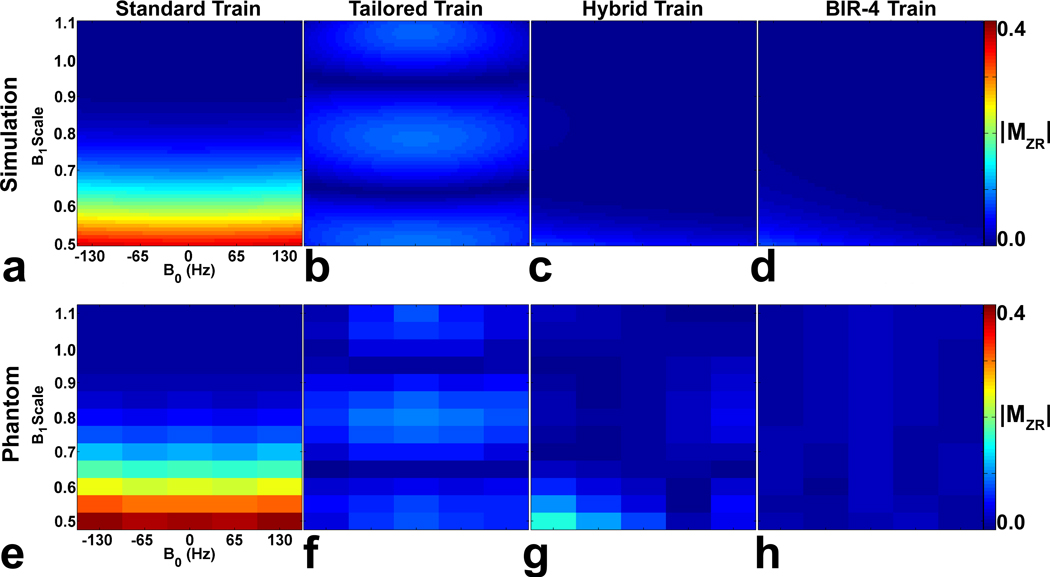

Figure 2.

(Top row) Simulated MZR maps as a function of B0 and B1+ scales. Compared with the (a) standard pulse train and (b) tailored pulse train, both the (c) hybrid pulse train and the (d) BIR-4 pulse train yielded considerably lower MZR maps. The resulting RMS MZR measurements were 0.136, 0.055, 0.013, and 0.012 for the standard train, tailored train, hybrid train, and BIR-4 pulse train, respectively. (Bottom row) MZR maps of the phantom as a function of B0 and B1+ scales. Consistent with the simulation results, the corresponding phantom MZR maps were in good agreement, and both the (g) hybrid pulse train and (h) BIR-4 pulse train produced considerably lower MZR maps than the (d) standard and (e) tailored pulse trains. The resulting RMS MZR measurements were 0.164, 0.053, 0.035, and 0.016 for the standard train, tailored train, hybrid train, and BIR-4 pulse train, respectively. The MZR maps are displayed with identically narrow grayscales (0 – 0.4 in dimensionless units) to bring out regional variations.

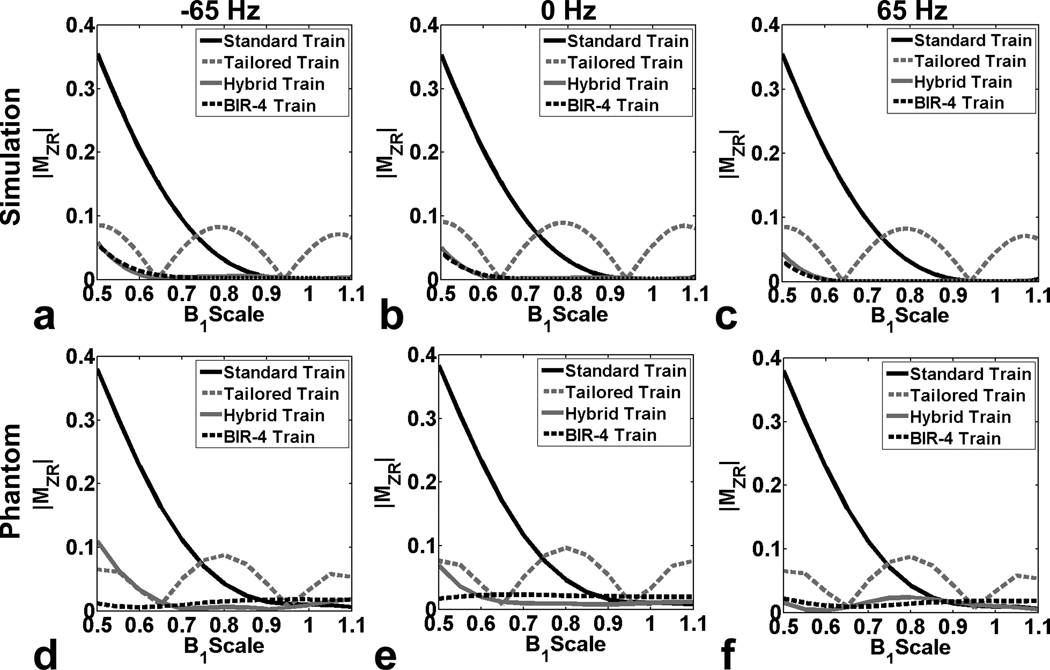

Figure 3.

(Top row) Numerically simulated profiles of MZR as a function of B1+ scale: (a) −65 Hz, (b) 0 Hz, and (c) 65 Hz off-resonance. (Bottom row) Corresponding profiles of MZR in the phantom as a function of B1+ scale: (d) −65 Hz, (e) 0 Hz, and (f) 65 Hz off-resonance. Note that the standard pulse train yielded lower MZR than the tailored pulse train for B1+ scales > 0.72, and vice versa for B1+ scales < 0.72. In contrast, the hybrid pulse train and BIR-4 pulse train yielded considerably lower MZR throughout the B1+ scale.

For comparison, we implemented previously proposed standard and tailored pulse trains on a 3T whole-body MR scanner (Tim Trio, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany), equipped with a gradient system capable of achieving a maximum gradient strength of 45 mT/m and a slew rate of 200 T/m/s. For reference, we implemented a train of two BIR-4 pulses (BIR-4 pulse train), as suggested by Cunningham et al. (16), in order to evaluate the efficacy of other saturation pulses. The frequency sweep of the BIR-4 pulse was ± 12.5 kHz, and its nominal B1+ calibrated by the transmit body coil was 500 Hz (14)(i.e., 12% larger than the 447 Hz frequency difference between the fat and water signal at 3T).

Using the pulse sequence simulator (IDEA, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany), we calculated the transmit RF energy for each pulse, assuming that the RF voltage needed for B1+ of 500 Hz is 600 V. This RF calibration assumption is based on our extensive experience with cardiac MRI at 3T. The theoretically calculated transmit RF energy of the standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train was 10.8, 17.8, 25.3, and 105.8 J, respectively. The RF excitation was performed using the transmit body coil, and 6-element anterior and 6-element posterior phased arrays were used for signal reception. The RF energy deposition depends on several variables, including: linearity of the RF power amplifier, efficacy of the transmit body coil, and patient body. Therefore, we also calculated the relative RF energy of each pulse as its RF energy divided by the RF energy of the corresponding standard RF pulse train, which is then by definition a "1." The relative RF energy of the tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train was 1.65, 2.34, and 9.80, respectively. Based on our previous experience with the standard pulse train and adiabatic pulses (9), we have empirically determined that the proposed hybrid pulse train, consisting of two non-selective rectangular pulses and one AHP pulse, does not exceed clinically acceptable SAR limits for multi-slice (≥6), first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI at 3T (see Table 3).

Table 3.

The mean predicted SAR and maximum allowable perfusion image acquisitions per cardiac cycle. For each saturation pulse, the SAR per slice was calculated by dividing the SAR measurements by the maximum permitted number of slices. The acquisition time per slice was 160 ms, and these measurements were recorded with a total acquisition window of 1000 ms (i.e., heart rate of 60 beats per minute). The reported values represent the mean ± SD.

| Standard Train | Tailored Train | Hybrid Train | BIR-4 pulse train | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total SAR (%) | 45.0 ± 3.2 | 64.4 ± 4.2 | 85.4 ± 8.0 | 72.0 ± 23.8 |

| Slices per cardiac cycle |

6 ± 0 | 6 ± 0 | 6 ± 0 | 1.4 ± 0.5 |

| Mean SAR per slice (%) |

7.5 ± 0.5 | 10.7 ± 0.7 | 14.2 ± 1.3 | 50.5 ± 4.0 |

All three pulse trains were comprised of the same following gradient pulses in succession: 1 ms long spoiler gradients (magnitude of net zeroth gradient moment = 15 mT/m·ms), 3 ms long crusher gradients (magnitude of net zeroth gradient moment = 75 mT/m·ms), 2 ms long crusher gradients (magnitude of net zeroth gradient moment = 45 mT/m·ms), and 3 ms long spoiler gradients (magnitude of net zeroth gradient moment = 75 mT/m·ms). The BIR-4 pulse train used the same spoiler and crusher gradients, except that it used only the first set of crusher gradients (magnitude of net zeroth gradient moment = 75 mT/m·ms). The spoiler gradients are applied before and after each saturation pulse to diphase the transverse magnetization, and the crusher gradients in between RF pulses are cycled to eliminate stimulated echoes. Table 1 summarizes the RF pulse characteristics of the four different pulses.

Table 1.

Summary of RF pulse characteristics of the standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train. Each pulse is preceded by 1 ms long spoiler gradient and followed by 3 ms long spoiler gradient. For each pulse train, the first and second crusher gradient durations are 3 and 2 ms, respectively. For the hybrid train, the last subpulse is an AHP pulse. For the BIR-4 pulse train, only the first set of crusher gradients is employed. Note that the B1+ represents the peak nominal value. The transmit RF energy was calculated assuming that the RF voltage needed for B1+ of 500 HZ is 600 V.

| Angle (°) | Duration (ms) | B1+ (Hz) | RF Energy (J) | Relative RF Energy | Duration (ms) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Train |

90 | 0.5 | 500 | 10.8 | 1 | 10.5 |

| 90 | 0.5 | 500 | ||||

| 90 | 0.5 | 500 | ||||

| Tailored Train |

96 | 0.6 | 444.44 | 17.8 | 1.65 | 11.7 |

| 228 | 1.3 | 487.18 | ||||

| 141 | 0.8 | 489.58 | ||||

| Hybrid Train |

140 | 0.8 | 486.11 | 25.3 | 2.34 | 11.8 |

| 90 | 0.5 | 500 | ||||

| 90 (AHP) | 1.54 | 666.67 | ||||

| BIR-4 pulse train |

90 | 8.1 | 500 | 105.8 | 9.80 | 23.2 |

| 90 | 8.1 | 500 |

Pulse Sequence

The MZR left behind by a saturation pulse can be measured by performing saturation-recovery (SR) ultra-fast gradient echo (i.e., TurboFLASH) imaging with "zero" recovery and centric k-space reordering, as previously described (9). Relevant imaging parameters include: field of view (FOV) = 340 × 276 mm, acquisition matrix = 64 × 52, slice thickness = 8 mm, TE/TR = 1.1/2.3ms, saturation recovery time delay (TD) = 3 ms, image acquisition time = 78 ms, flip angle = 10°, generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA)(17) with an acceleration factor = 1.5, and receiver bandwidth = 1002 Hz/pixel. Proton density (PD) image was acquired using 4° flip angle and without the saturation pulse, in order to perform image normalization (see the Image Analysis section for more details).

Numerical Simulation

The MZR left behind by each saturation pulse was simulated for B0 ranging from ± 130 Hz (3 Hz steps)(5) and B1+ scale ranging from 0.5 – 1.1 (0.5 steps)(6). The numerical simulation was performed by ignoring T1 relaxation between subpulses (i.e., during crusher gradient pulses), assuming complete dephasing of the transverse magnetization between subpulses, and with M0 scalar equal to 1. For each non-selective rectangular pulse, its MZR was calculated using the Bloch equations in the rotating frame. Specifically, the effective field and effective nutation angle were calculated, as previously described (7), using a customized code programmed in MATLAB® R2008a (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Another customized software programmed in visual C++® 6.0 (Microsoft Corporation©, Bellevue, WA) was used to calculate the MZR left behind by adiabatic pulses. Specifically, the actual RF pulse profiles (i.e., amplitude and phase) used by the MR scanner were used to calculate the generalized solutions of the Bloch equations using the Laplace transformation, as previously described (18). The simulation for the adiabatic pulses was performed by ignoring T1 relaxation between subpulses, assuming adiabaticity, and with T1 = 1000 ms, T2 = 40 ms, and M0 scalar equal to 1. For the standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train, their net MZR was calculated as the product of MZR of individual subpulses. For each saturation pulse, MZR was plotted as a function of B0 and B1+ scales, and the corresponding RMS MZR was calculated.

Phantom Imaging

Phantom experiments were performed to evaluate the performance of the four saturation pulses. A spherical oil phantom (T1 = 530 ms) was imaged to minimize the dielectric effects (19). The T1 of this phantom was calculated from a separate multi-point SR experiment. The image acquisition was performed in an axial plane at magnet isocenter, in order to achieve relatively homogeneous B1 excitation within the phantom using the body coil. The B0 offset was manually adjusted to produce −130, −65, 0, 65, and 130 Hz off-resonance, in order to mimic clinically relevant B0 variation within the heart at 3T (3,5). For each B0 offset, the image acquisition was repeated with B1+ scale of each saturation pulse manually adjusted from 0.5–1.1 (0.05 steps) of its nominally calibrated B1+ value, in order to determine the sensitivity of each saturation pulse to clinically relevant B0 and B1+ variations within the heart (3–6). For each saturation pulse, 60 MZR measurements were recorded using aforementioned B0 and B1 scales, with a repetition time of 4000 ms to allow for full recovery of magnetization between image acquisitions. For each saturation pulse, MZR was plotted as a function of B0 and B1+ scales, and the corresponding RMS MZR was calculated.

Cardiac Imaging

MZR Measurements

Nine healthy human subjects (6 males; 3 females; mean age = 29.0 ± 4.7 years; mean weight = 68.8 ± 8.9 kg) were imaged in 3 short-axis views (apical, mid-ventricular, and basal) of the LV and three long-axis views (2-chamber view of LV, 2-chamber view of RV, and 4-chamber). For imaging the 2-chamber view of the RV, with all other parameters being equal, the FOV was increased from 340 mm × 276 mm to 400 mm × 325 mm, in order to avoid aliasing artifacts. Human imaging was performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Human Investigation Committee at our institution; all subjects provided written informed consent.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) gating was used to acquire the images at mid diastole (trigger delay = 500 ms), in order to minimize the effects of cardiac motion. For each cardiac view per saturation pulse, PD (heart beat 1) and SR (heart beat 8) images were acquired with a breath-hold duration of approximately 8 s, with a wait time of 6 heart beats (~6 s) to allow for full recovery of magnetization [> 5 × T1; T1 of myocardium = 1150 ms at 3T (3)] between the two image acquisitions. This relatively short breath-hold duration ensured reliable registration of PD and SR images. For each subject, 24 separate breath-hold acquisitions were performed (i.e., 6 cardiac views × 4 saturation pulses) with the magnet isocenter positioned at the mid-ventricular, short-axis plane. To optimally utilize the dynamic range of the 12-bit analog-to-digital converter (ADC), for each subject, the receiver gains were adjusted so that the maximum intensity of the PD image is approximately 80–90% of the maximum value of the ADC (i.e., 4095). This ensured that the signal of the SR image will be well above the noise. For each subject, the RF calibration, B0 shimming, and receiver gains were kept unchanged between different SR image acquisitions, in order to permit MZR comparisons.

SAR Measurements

In the same set of nine subjects, a separate experiment was conducted to measure the predicted SAR for each saturation pulse, using a multi-slice first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI protocol without contrast agent. The saturation pulses were incorporated into a TurboFLASH pulse sequence with the following relevant imaging parameters: FOV = 350 × 285 mm, acquisition matrix = 144 × 118 (59 acquired phase-encoding lines), spatial resolution = 2.4 mm × 2.4 mm, slice thickness = 8 mm, TE/TR = 1.2/2.34ms, TD = 10 ms, time-adaptive sensitivity encoding (TSENSE)(20) with an acceleration factor = 2, image acquisition time = 138 ms, total scan time (including TD, saturation pulse duration) ~ 160 ms, flip angle = 10°, repetitions = 40, and receiver bandwidth = 990 Hz/pixel. This experiment was performed with a simulated heart rate of 60 beats per minute, in order to measure the predicted SAR and maximum allowable perfusion image acquisitions per cardiac cycle within clinically acceptable SAR limits, for all nine subjects using an identical total acquisition window of 1000 ms. In addition, SAR per slice was calculated by dividing the SAR measurement by the maximum permitted number of slices.

Preliminary Evaluation

A 27 years old female subject was imaged without contrast agent using the aforementioned first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI protocol (except repetitions = 9), in order to evaluate the efficacy of these saturation pulses in vivo. For each saturation pulse, a short-axis plane of the LV was imaged repeatedly for 9 heart beats. A PD image was acquired during the first heartbeat with 4° flip angle, no saturation pulse, and centric k-space trajectory to minimize T1-weighting. The RF calibration, shimming, and receiver settings were kept unchanged between acquisitions, to permit signal comparisons.

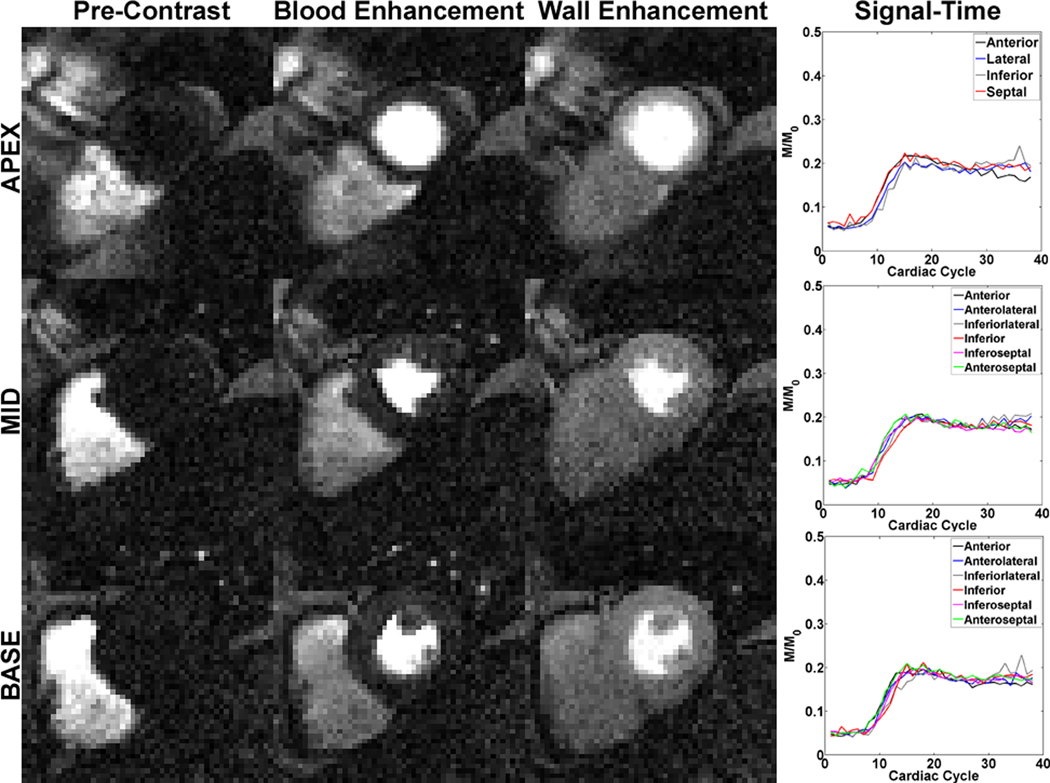

A 35 years old male subject was imaged during first-passage of contrast agent using the aforementioned cardiac perfusion protocol with the hybrid pulse train as the saturation pulse, in order to evaluate the uniformity of the myocardial T1-weighted signal in three short-axis planes of the LV (apex, mid, base). A single dose (0.1 mmol/kg) of Gd-DTPA (Magnevist, Bayer Healthcare) was injected at a flow rate of 6 ml/s by a power injector (MEDRAD, Warrendale, PA), followed by a 20 ml flush of saline. For signal normalization, pre-contrast PD image was acquired during the first heartbeat with 4° flip angle, no saturation pulse, and centric k-space trajectory to minimize T1-weighting.

Influence of the Saturation Pulse on the Accuracy of T1-Weighted Imaging

A numerical simulation was performed to assess the influence of each saturation pulse on the accuracy of dynamic T1-weighted imaging with the aforementioned TurboFLASH protocol. Specifically, for each pulse, the simulation was performed with three LV MZR measurements (Table 2): mean – standard deviation (SD), mean, and mean MZR + SD. For the Mz calculation, the initial Mz(0) after the saturation pulse and immediately prior to the TurboFLASH readout was defined as M z (0) = M 0 + (M ZR − M 0)e−TD/T1, where M0 scalar =1. This initial Mz was then inputted to solve an iterative multiplication of rotation matrices in the rotating frame as a function of phase-encoding line. The simulation was performed with 10° excitation of a single isochromat at on-resonance and assumed complete dephasing of the transverse magnetization before the next RF excitation.

Table 2.

Mean, maximum, and minimum MZR left behind after nominal saturation. Each ROI was considered to be an independent sample (n = 45). Statistically, the mean MZR within the LV and RV was different between all pulse groups (p< 0.001). Within each pair of groups, the mean MZR within the LV was significantly higher for the tailored pulse train than for the other three pulses (p < 0.001), and the mean MZR was not different for any pair between the standard pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train. Within the RV, the mean MZR was significantly higher for both the standard and tailored pulse trains than for either the hybrid pulse train or BIR-4 pulse train (p < 0.001), and not different between the standard and tailored pulse trains and between the hybrid pulse train and BIR-4 pulse train. The reported mean values represent the mean ± SD of averaged MZR over ROIs.

| Ventricle | Standard Train | Tailored Train | Hybrid Train | BIR-4 pulse train | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV | Mean | 0.018 ± 0.008 | 0.048 ± 0.007 | 0.015 ± 0.005 | 0.016 ± 0.004 |

| Max | 0.054 | 0.069 | 0.028 | 0.027 | |

| Min | 0.009 | 0.035 | 0.008 | 0.010 | |

| RV | Mean | 0.069 ± 0.043 | 0.057 ± 0.012 | 0.018 ± 0.006 | 0.015 ± 0.005 |

| Max | 0.195 | 0.079 | 0.042 | 0.032 | |

| Min | 0.013 | 0.026 | 0.009 | 0.007 | |

The T1-weighted signal (S) was defined as Mz at the center of k-space (21)(i.e., phase-encoding line = 30; effective recovery time = 80.2 ms), and this calculation was repeated for T1 ranging from 50 – 1150 ms (100 ms steps). The true T1-weighted signal (S0) was calculated with MZR = 0, and the corresponding normalized signal was calculated as S/S0 and plotted as a function of T1.

Image Analysis

For signal normalization, the SR image (nominally zero signal) was divided by the corresponding PD (nominally maximum signal) image on a pixel-by-pixel basis, in order to correct for signal variations due to the receiver coil sensitivity (i.e., B1−), T2* decay, B1+ variation of the excitation pulse, imperfect slice profile, and underlying M0, as previously described (8,9). The quotient image was multiplied by the factor sin(4°)/sin(10°) to account for the difference in the two excitation angles. The resulting normalized image intensity conveniently has a range of 0 (complete saturation) to 1 (no saturation).

For phantom image analysis, a region of interest (ROI) was manually drawn to cover the whole phantom, and the mean MZR was calculated for each ROI. For cardiac image analysis, an ROI was manually drawn for the whole LV and/or RV per cardiac view, and the mean MZR was calculated for each ROI. For statistical analysis, each ROI was considered to be an independent sample, and the reported values represent the mean ± SD of averaged MZR over ROIs. For in vivo SAR analysis, the reported values represent the mean ± SD of SAR measurement. A single-factor analysis of variance was used to compare the mean values between the four pulse groups (p < 0.05 was considered to be significant), and the Tukey’s honestly significant difference test was used to compare the mean values between each pair of two groups (p < 0.05 was considered to be significant). The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS© Inc, Chicago, IL).

For evaluation of the homogeneity of T1-weighted signal, an ROI was manually drawn for the whole myocardium. Care was taken to avoid partial volume effects. As described above, the T1-weighted images were divided by the PD image on a pixel-by-pixel basis. The three short-axis planes were subdivided into 16 segments according to the American Heart Association standardized model (22). For each segment, the normalized T1-weighted signal was plotted as a function of cardiac cycle.

Results

Figure 2 shows the magnitude of numerical MZR map as a function B0 and B1+ scales for each of four saturation pulses. Compared with the standard and tailored pulse trains, both the hybrid pulse train and the BIR-4 pulse train yielded considerably lower MZR maps. The resulting RMS MZR measurements were 0.136, 0.055, 0.013, and 0.012 for the standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train, respectively. Consistent with the simulated MZR maps, the corresponding phantom MZR maps were in good agreement, and both the hybrid pulse train and BIR-4 pulse train produced considerably lower MZR maps than the standard and tailored pulse trains. The resulting RMS MZR measurements were 0.164, 0.053, 0.035, and 0.016 for the standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train, respectively. Figure 3 shows the corresponding profiles of MZR as a function of B1+ scale, for −65 Hz, 0 Hz, and 65 Hz off-resonance. Note that the standard pulse train produced lower MZR than the tailored pulse train for B1+ scale > 0.72 and vice versa for B1+ scale < 0.72. In contrast, both the hybrid pulse train and BIR-4 pulse train yielded considerably lower MZR throughout the B1+ scale.

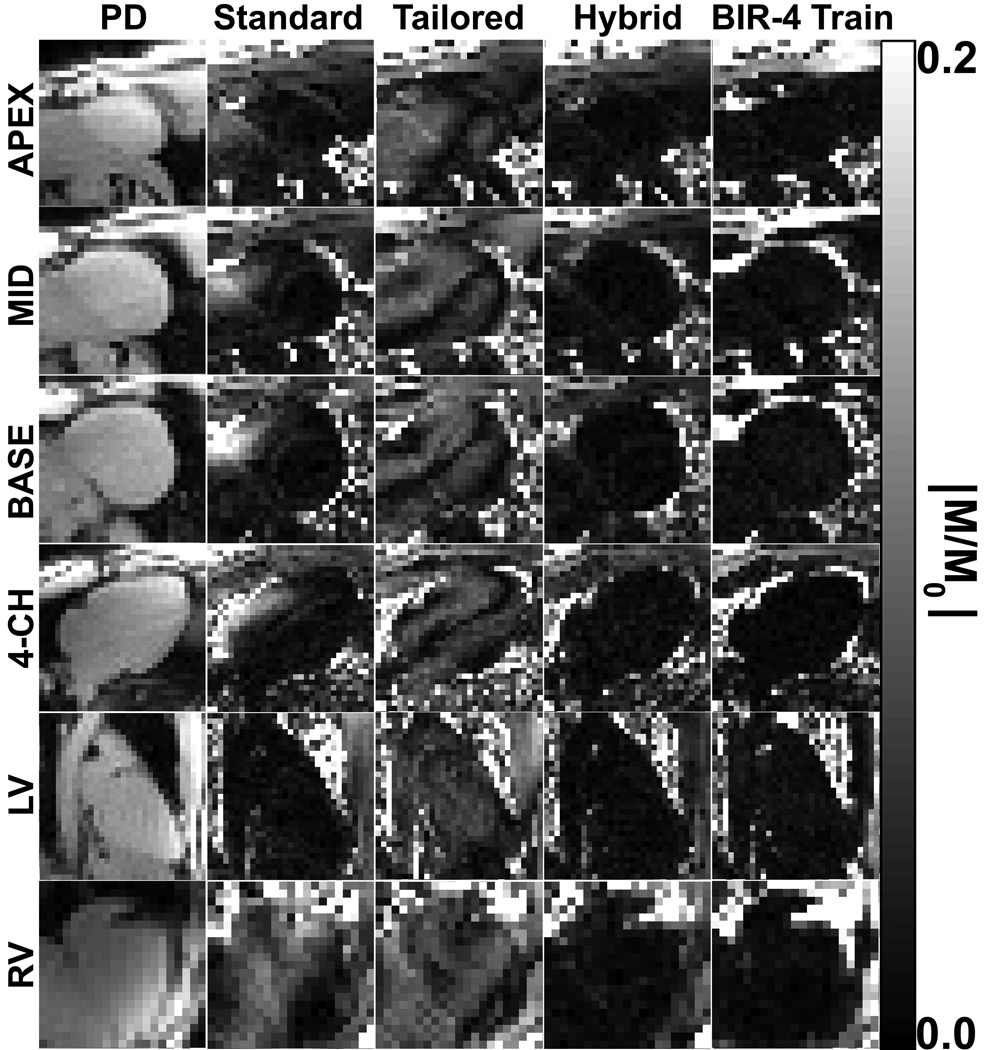

Figure 4 shows representative normalized SR images of one volunteer in all six cardiac views. The bright areas in the normalized images represent the (undesirable) non-zero MZR left behind from the effective flip angle variation due to B0 and B1+ inhomogeneities. Consistent with the previous studies (9,13), the standard pulse train performed well within the LV (dark regions) but poorly within the RV (bright regions). The tailored pulse train performed similarly within the whole heart, but at the expense of producing medium level of non-uniform MZR values (gray regions and dark bands) within both ventricles. In contrast, both the hybrid RF pulse train and BIR-4 pulse train yielded uniformly minimal MZR within both ventricles (dark regions). Statistically, the mean MZR within the LV (0.018 ± 0.008 vs. 0.048 ± 0.007 vs. 0.015 ± 0.005 vs. 0.016 ± 0.004; standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train, respectively; n= 45; p< 0.001) and RV (0.069 ± 0.043 vs. 0.057 ± 0.012 vs. 0.018 ± 0.006 vs. 0.015 ± 0.005; standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, BIR-4 pulse train, respectively; n= 45; p< 0.001) was different between all pulse groups (see Table 2). Within each pair of groups, the mean MZR within the LV was significantly higher for the tailored pulse train than for the other three pulses (p < 0.001), and the mean MZR was not different for any pair between the standard pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train. The corresponding range (min-max) of MZR was 0.009–0.054, 0.035–0.069, 0.008–0.028, and 0.010–0.027 for the standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train, respectively. Within the RV, the mean MZR was significantly higher for both the standard and tailored pulse trains than for either the hybrid pulse train or BIR-4 pulse train (p < 0.001), and not different between the standard and tailored pulse trains and between the hybrid pulse train and BIR-4 pulse train. The corresponding range (min-max) of MZR was 0.013–0.195, 0.026–0.079, 0.009–0.042, and 0.007–0.032 for the standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train, respectively. These in vivo cardiac MZR results demonstrate the superior efficacy of the hybrid pulse train and BIR-4 pulse train over the standard and tailored pulse trains.

Figure 4.

Representative set of normalized SR images from one volunteer that compares the performance of four saturation pulses. The standard pulse train performed well within the LV (dark regions) but poorly within the RV (bright regions). The tailored pulse train performed similarly within the whole heart, but at the expense of producing medium level of MZR values (gray regions and dark bands) within both ventricles. In contrast, both the hybrid RF pulse train and BIR-4 pulse train yielded uniformly minimal MZR within both ventricles (dark regions). The normalized images are displayed with identically narrow grayscales (0 – 0.2 in dimensionless units) to bring out regional variations.

In nine subjects studied, the standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, and hybrid pulse train were capable of acquiring six slices using the TurboFLASH protocol (i.e., total acquisition time = 960 ms; total acquisition window = 1000 ms), whereas the BIR-4 pulse train was capable of acquiring only 1.4 ± 0.5 slices within clinically acceptable SAR limits (see Table 3). The mean SAR per slice was 7.5 ± 0.5, 10.7 ± 0.7, 14.2 ± 1.3, and 50.5 ± 4.0 for the standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train, respectively. Statistically, the mean SAR per slice was significantly different between all pulse groups (p < 0.001) and between each pair of groups (p < 0.02). These in vivo results strongly suggest that the hybrid pulse train can be safely used for multi-slice (≥ 6), first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI at 3T.

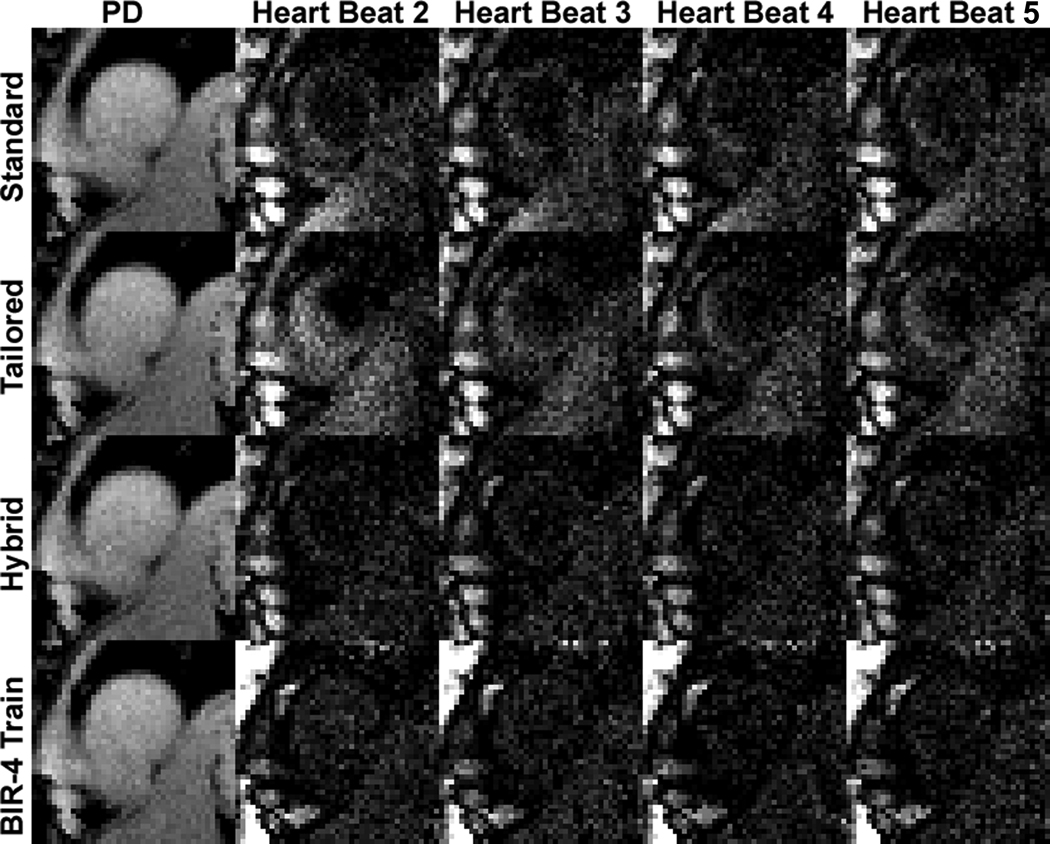

Figure 5 shows repeated acquisitions of non-contrast T1-weighted images over multiple heart beats. Both the standard and tailored pulse trains yielded residual signal compared with the hybrid and BIR-4 pulse trains. As can be seen in Figure 5, as well as in Figure 4, both the hybrid and BIR-4 pulse trains are also capable of performing effective saturation of magnetization beyond the heart (e.g., the liver) because of their insensitivity to B0 and B1 inhomogeneities. Figure 6 shows representative first-pass cardiac perfusion images at pre-contrast, peak blood enhancement, and peak myocardial wall enhancement, using the hybrid pulse train as the saturation pulse. Figure 6 also shows the corresponding plots of normalized T1-weighted signal for each of 16 segments as a function of cardiac cycle. These normalized signal-time curves show good agreement between segments, suggesting that the hybrid pulse train had produced uniform saturation of magnetization.

Figure 5.

Representative repeated acquisitions of non-contrast T1-weighted images over multiple heart beats: (first row) standard train, (second row) tailored train, (third row) hybrid train, and (fourth row) BIR-4 train. Both the standard and tailored pulse trains yielded residual signal compared with the hybrid and BIR-4 pulse trains. The T1-weighted images are displayed with identically grayscales (200 – 1000 in arbitrary units) to bring out regional variations.

Figure 6.

Representative first-pass cardiac perfusion images at (first column) pre-contrast, (second column) peak blood enhancement, and (third column) peak myocardial wall enhancement, using the hybrid pulse train as the saturation pulse: (first row) apex, (second row) mid-ventricular, and (third row) base. (Fourth column) The corresponding plots of normalized T1-weighted signal for each of 16 segments as a function of cardiac cycle. These normalized signal-time curves show good agreement between segments, suggesting that the hybrid pulse train had produced uniform T1-weighted signal. The T1-weighted images are displayed with identically grayscales (200 – 1500 in arbitrary units).

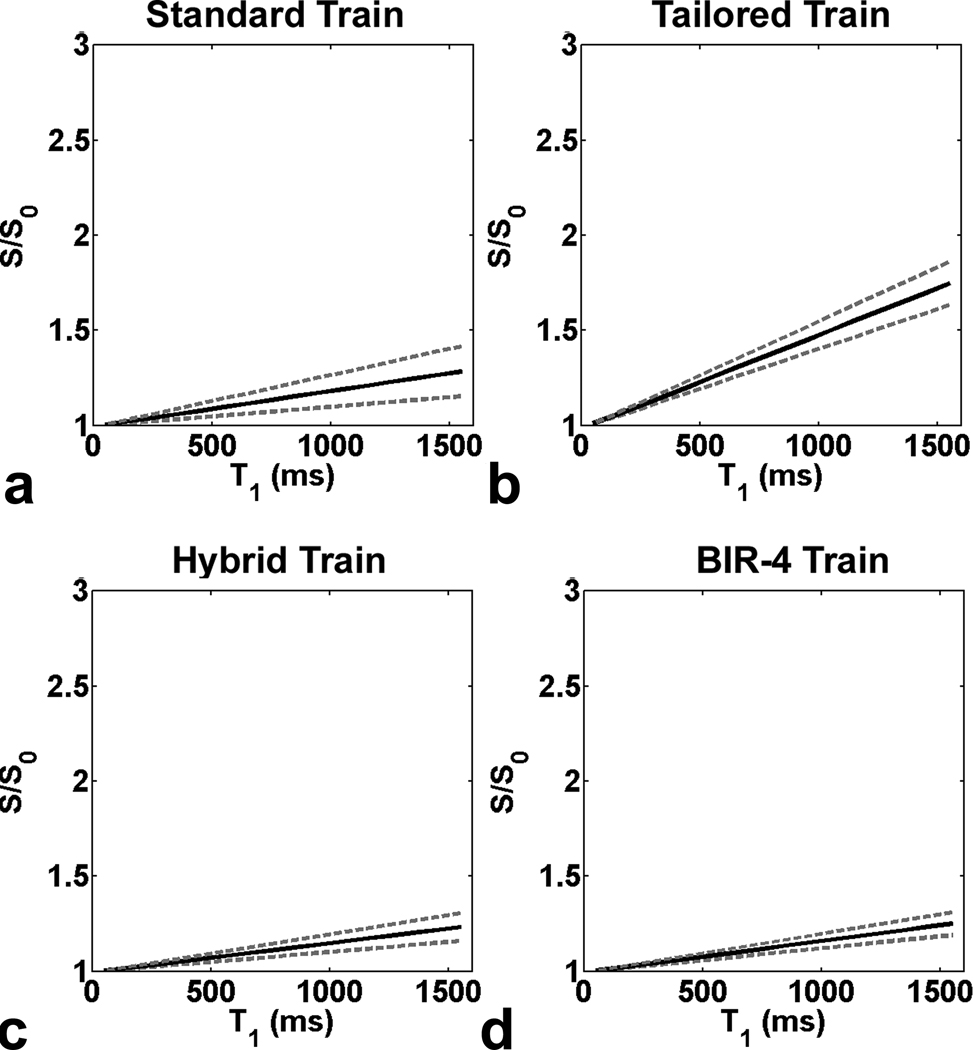

Figure 7 shows plots of S/S0 as a function of T1. The standard pulse train yielded relatively accurate S/S0, whereas the tailored pulse train yielded less accurate S/S0. Compared with the standard and tailored pulse trains, both the hybrid pulse train and BIR-4 pulse train produced more accurate S/S0. It should be noted that for MZR = 0.02, the normalized S ≥ 1.2 (i.e., 20% error) for T1 ≥ 1050 ms (data not shown). These numerical results highlight the importance of uniform T1-weighting in first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI, and that the examined first-pass perfusion protocol (acquisition time ~ 160 ms; TD = 10 ms, flip angle = 10°) is sensitive to MZR left behind by the nominal saturation pulse for large T1 values.

Figure 7.

Simulated plots of S/S0 as a function of T1 for the LV: (a) standard pulse train, (b) tailored pulse train, (c) hybrid pulse train, and (d) BIR-4 pulse train. The standard pulse train yielded relatively accurate S/S0, whereas the tailored pulse train yielded less accurate S/S0. Compared with the standard and tailored pulse trains, both the hybrid pulse train and BIR-4 pulse train produced more accurate S/S0. Solid line represents S/S0 calculated with mean in vivo MZR. Upper and lower dotted lines represent S/S0 calculated with mean+SD and mean−SD in vivo MZR, respectively.

Discussion

This study has compared the efficacy of four saturation pulses: standard pulse train, tailored pulse train, hybrid pulse train, and BIR-4 pulse train. Compared with the standard and tailored pulse trains, both the hybrid pulse train and BIR-4 pulse train yielded more uniform saturation of magnetization (MZR ≤ 0.02) within the whole heart (Table 2). These findings are significant because MZR as small as 5–7% of M0 can cause significant error in the dynamic T1-weighted signal (Fig. 7). The influence of the saturation pulse on the accuracy the T1-weighted signal was determined to be relativlely high, particularly for large T1 values (≥ 1000 ms). These findings confirm that it is critically important to perform uniform T1-weighting for accurate quantification of T1 from first-pass cardiac perfusion MR images.

The major advantage of the hybrid pulse train is that it is relatively insensitive to both B0 and B1+ variations within the whole heart at 3T, and, therefore, can be used in conjunction with commercially available automated B0 shimming and RF calibration procedures. Its efficacy is comparable to that of the BIR-4 pulse train, whereas its RF energy is 76% less than that of the BIR-4 pulse train. Our results show that the extra RF energy (134% more than that of the standard pulse train) needed to employ the hybrid pulse train does not exceed the clinically acceptable SAR limits for multi-slice (≥ 6) first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI (Table 3).

In our study, the standard pulse train produced lower MZR in the LV than the tailored pulse train, whereas vice versa was true in the study by Sung et al. (13). The conflicting comparative results between the standard and tailored pulse trains by our study and by Sung et al. (13) deserves an explanation. As shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3 and Figure 4 in (13), both the standard and tailored pulse trains are relatively insensitive to clinically relevant B0 variation, and the standard pulse train produces lower MZR than the tailored pulse train for B1+ scale > 0.72 and vice versa B1+ scale < 0.72. It should be noted that the commercially available automated RF calibration procedures and B1 homogeneity of the transmit body coil are likely to differ between different vendors (e.g., Siemens vs. GE). Therefore, the conflicting comparative results between the standard and tailored pulse trains by our study and by Sung et al. (13) are highly likely due to the differences in RF calibration and/or B1 homogeneity of the transmit body coil. Our in vivo results (Figure 4; Table 2) suggest that the mean B1+ scale in the heart examined by our study was greater than 0.72. In contrast, in the study by Sung et al. (13), the tailored pulse train yielded lower MZR than the standard pulse train (see Figure 4 and Table 2 in reference 13), suggesting that the mean B1+ scale in the heart was less than 0.72. Furthermore, it should be noted that Sung et al. (13) measured relative MZR, because they acquired both SR and PD images with two “shots” segmented over two heart beats, and with only one hearbeat for magnetization recovery between the SR and PD acquisitions. Therefore, this key difference needs to be considered when comparing their relative MZR measurements with our absolute MZR measurements.

This study had three limitations that warrant discussion. First, the tailored pulse train used in this study was optimized for a GE whole-body 3T system and may not represent the optimal tailored pulse train for our Siemens whole-body 3T system. To fully optimize the tailored pulse train for our Siemens 3T system, it is necessary to perform prior measurements of B0 and B1 variations within the heart. The conflicting results of the tailored pulse train by our study and by Sung et al. (13) suggest that a tailored pulse train needs to be calibrated for each scanner, using rapid cardiac B0 and B1 mapping pulse sequences. An optimized tailored pulse train, however, is likely to yield lower efficacy than a hybrid pulse train, because the latter utilizes an AHP which is more effective than a non-selective rectangular pulse. Second, the proposed hybrid pulse train design was based on B0 variation of 260 Hz, as reported by Schar et al. (5) using a Philips whole-body 3T system, and B1+ scale of 0.5 – 1.1, as reported by Sung et al. (6) using a GE whole-body 3T system. Despite the lack of direct cardiac B1+ scale and B0 offset measurements from our Siemens 3T system, the proposed hybrid pulse train performed remarkably well within the whole heart in all nine subjects, because the hybrid pulse train was designed to be highly insensitive to B0 and B1 inhomogeneites (Figure 2 and Figure 3). As such, our results suggest that the hybrid pulse train may perform effectively without calibration for different whole-body 3T systems. Third, the proposed hybrid pulse train was designed without SAR optimization. While it may be possible to perform joint optimization of effective saturation of magnetization and SAR, the optimization will require a complex theoretical SAR model that is beyond the scope of this study. We have shown the feasibility to acquire up to six slices using a typical first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI protocol with the hybrid pulse train as the saturation pulse. As such, the hybrid pulse train can be used safely for typical multi-slice, first-pass cardiac perfusion MRI.

The hybrid pulse train can also be used for other applications. In particular, the hybrid pulse can train be used for T1 mapping in the presence of B0 and B1 inhomogeneities. In particular, it can be used in an Look-Locker approach to measure myocardial T1 (23), where the benefit of a saturation pulse over an inversion pulse would be that the former is insensitive to heart rate variability (24). The hybrid pulse train can also be used in a SR double angle method for rapid B1 mapping (16).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Michael Garwood of the University of Minnesota for providing us with the AHP and BIR-4 pulse-generating software.

Grant Sponsor: American Heart Association: 0730143N

References

- 1.Cheng AS, Pegg TJ, Karamitsos TD, Searle N, Jerosch-Herold M, Choudhury RP, Banning AP, Neubauer S, Robson MD, Selvanayagam JB. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance perfusion imaging at 3-tesla for the detection of coronary artery disease: a comparison with 1.5-tesla. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49(25):2440–2449. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenman RL, Shirosky JE, Mulkern RV, Rofsky NM. Double inversion black-blood fast spin-echo imaging of the human heart: a comparison between 1.5T and 3.0T. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2003;17(6):648–655. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noeske R, Seifert F, Rhein KH, Rinneberg H. Human cardiac imaging at 3 T using phased array coils. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2000;44(6):978–982. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200012)44:6<978::aid-mrm22>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singerman RW, Denison TJ, Wen H, Balaban RS. Simulation of B1 field distribution and intrinsic signal-to-noise in cardiac MRI as a function of static magnetic field. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1997;125(1):72–83. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1996.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schar M, Kozerke S, Fischer SE, Boesiger P. Cardiac SSFP imaging at 3 Tesla. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2004;51(4):799–806. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sung K, Nayak KS. Measurement and characterization of RF nonuniformity over the heart at 3T using body coil transmission. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2008;27(3):643–648. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ernst RR, Bodenhausen G, Wokaun A. Principles of nuclear magnetic resonance in one and two dimensions. New York: Oxford University Press Inc.; 1987. Off-resonance effects due to finite pulse amplitude; pp. 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim D, Cernicanu A, Axel L. B(0) and B(1)-insensitive uniform T(1)-weighting for quantitative, first-pass myocardial perfusion magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2005;54(6):1423–1429. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim D, Gonen O, Oesingmann N, Axel L. Comparison of the effectiveness of saturation pulses in the heart at 3T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;59(1):209–215. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staewen RS, Johnson AJ, Ross BD, Parrish T, Merkle H, Garwood M. 3-D FLASH imaging using a single surface coil and a new adiabatic pulse, BIR-4. Investigative Radiology. 1990;25(5):559–567. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199005000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogg RJ, Kingsley PB, Taylor JS. WET, a T1- and B1-insensitive water-suppression method for in vivo localized 1H NMR spectroscopy. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Series B. 1994;104(1):1–10. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oesingmann N, Zhang Q, Simonetti O. Improved saturation RF pulse design for myocardial first-pass perfusion at 3T. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2004;6(1):373–374. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung K, Nayak KS. Design and use of tailored hard-pulse trains for uniform saturation of myocardium at 3 Tesla. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;60:997–1002. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garwood M, Ugurbil K. NMR Basic Principles and Progress. Volume 26. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1992. B1 insensitive adiabatic RF pulses; pp. 109–147. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bendall M, Pegg D. Uniform sample excitation with surface coils for in vivo spectroscopy by adiabatic rapid half passage. ournal of Magnetic Resonance. 1986;67:376–381. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunningham CH, Pauly JM, Nayak KS. Saturated double-angle method for rapid B1+ mapping. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006;55(6):1326–1333. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, Nittka M, Jellus V, Wang J, Kiefer B, Haase A. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2002;47(6):1202–1210. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris G, Chilvers P. General analytical solutions of the Bloch equations. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1994;107(1):236–238. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simmons A, Tofts PS, Barker GJ, Arridge SR. Sources of intensity nonuniformity in spin echo images at 1.5 T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1994;32(1):121–128. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kellman P, Epstein FH, McVeigh ER. Adaptive sensitivity encoding incorporating temporal filtering (TSENSE) Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2001;45(5):846–852. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cernicanu A, Axel L. Theory-based signal calibration with single-point T1 measurements for first-pass quantitative perfusion MRI studies. Academic Radiology. 2006;13(6):686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2006.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK, Pennell DJ, Rumberger JA, Ryan T, Verani MS. American Heart Association Writing Group on Myocardial S, Registration for Cardiac I. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;105(4):539–542. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Messroghli DR, Radjenovic A, Kozerke S, Higgins DM, Sivananthan MU, Ridgway JP. Modified Look-Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) for high-resolution T1 mapping of the heart. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2004;52(1):141–146. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsekos NV, Zhang Y, Merkle H, Wilke N, Jerosch-Herold M, Stillman A, Ugurbil K. Fast anatomical imaging of the heart and assessment of myocardial perfusion with arrhythmia insensitive magnetization preparation. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;34(4):530–536. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]