Abstract

Antibody microarrays are a critical tool for proteomics, requiring broad, highly sensitive detection of numerous low abundance biomarkers. Fluorescent polymerization-based amplification (FPBA) is presented as a novel, non-enzymatic signal amplification method that takes advantage of the chain-reaction nature of radical polymerization to achieve a highly amplified fluorescent response. A streptavidin-eosin conjugate localizes eosin photoinitiators for polymerization on the chip where biotinylated target protein is bound. The chip is contacted with acrylamide as a monomer, N-methyldiethanolamine as a coinitiator and yellow/green fluorescent nanoparticles (NPs) which, upon initiation, combine to form a macroscopically visible and highly fluorescent film. The rapid polymerization kinetics and the presence of cross-linker favor entrapment of the fluorescent NPs in the polymer, enabling highly sensitive fluorescent biodetection. This method is demonstrated as being appropriate for antibody microarrays and is compared to detection approaches which utilize streptavidin-FITC (SA-FITC) and streptavidin-labeled yellow/green NPs (SA-NPs). It is found that FPBA is able to detect 0.16 (+/− 0.01) biotin-antibody/µm2 (or 40 zeptomole surface-bound target molecules), while SA-FITC has a limit of detection of 31 (+/− 1) biotin-antibody/µm2 and SA-NPs fail to achieve any significant signal under the conditions evaluated here. Further, FPBA in conjunction with fluorescent stereomicroscopy yields equal or better sensitivity compared to fluorescent detection of SA-eosin using a much more costly microarray scanner. By facilitating highly sensitive detection, FPBA is expected to enable detection of low abundance antigens and also make possible a transition towards less expensive fluorescence detection instrumentation.

Keywords: Antibody microarrays, signal amplification, visible-light photopolymerization, fluorescent nanoparticles

Introduction

Antibody microarrays constitute a major proteomics platform for biomarker discovery in both basic research and clinical applications. Uses have focused on patient sample profiling to identify protein markers with diagnostic potential in cancer,1,2 Alzheimer’s disease,3 heart disease,4 and chronic kidney disease,5 but have also included multiplexed food-borne pathogen detection6 and investigation of the molecular basis of drug effectiveness7 and side effects8, among a variety of additional applications.9 Due to their popularity and utility, numerous antibody microarray tests are currently commercially available.1,10,11

One significant requirement for antibody microarrays is multiplex detection of low abundance proteins (pg/mL and lower concentrations).1,12,13 To address this concern, many signal amplification strategies have been pursued including approaches to immobilize more fluorophores per binding event using fluorescent nanoparticles (NPs)14,15 or fluorescent proteins,16,17 use of quantum dots,18 as well as enzymatic techniques such as tyramide signal amplification and rolling circle amplification.17 Although fluorescence is the most widely used detection method due to its ease of use and the availability of fluorophores with a wide variety of spectral characteristics,2,9,13 chemiluminescence (enzymatically generated) and resonance light scattering (using colloidal gold particles) have also been employed.17 In addition, label-free detection platforms such as surface plasmon resonance imaging (SPRI) have been developed which simplify detection by eliminating a labeling step and preclude any label-associated binding interferences; however, this technology is only starting to become high throughput and is often used in conjunction with enzymatic methods to improve sensitivity.1,10

In contrast to enzymatic approaches, FPBA is a non-enzymatic detection method that uses the chain-reaction nature of radical chain polymerizations to achieve a highly amplified response.19 The resulting signal comprises a macroscopically visible and highly fluorescent film that is detectable by eye without instrumentation and may be quantified by fluorescent microscopy, in lieu of a more expensive laser-based microarray scanner. Since FPBA generates an amplified fluorescent signal with a completely different strategy than methods utilizing either enzymes or probes attached to macromolecular fluorescent species, FPBA has the potential to enhance sensitivity relative to other currently employed approaches. Moreover, the unique capability of this fluorescence-based detection technique to generate a macroscopically visible, qualitative result facilitates novel testing formats, such as a gateway testing scheme for screening pathogens in which only tests with a qualitatively positive result would subsequently be quantified by fluorescence.

Previous reports have shown that polymerization-based amplification (PBA) is amenable to a microarray format and may be done rapidly, simply, and inexpensively with extremely high sensitivity.20,21 In this method, a protein or DNA probe is covalently coupled to a photoinitiator for polymerization which subsequently yields a macroscopically visible polymer film in the presence of monomer and light specifically in regions of the chip where the biomarker of interest is bound to the surface. Sikes et al. have employed PBA with a UV-sensitive photoinitiator on a commercially available biodetection platform yielding a rapid (less than 20 minutes) DNA-based test with extremely high sensitivity (on the order of 10 zeptomoles, or 1000 recognition events) and requiring no instrumentation.20 Quantitative results in which film thickness correlates to both biotinylated DNA and photoinitiator surface concentration were achieved in a visible light photoinitiator system using standard glass microarray substrates.19,21,22 To obtain quantitative results more easily, fluorescent moieties were incorporated into the polymer films, such that fluorescence is representative of film thicknesses, eliminating the need for profilometer- or interferometer-based thickness measurements. Hansen et al. have demonstrated the feasibility of generating fluorescent films in response to a biorecognition event by including fluorescent nanoparticles (NPs) in the monomer mixture which become trapped in the polymer film as it grows from the surface, thus enabling quantitative evaluation of biotinylated-DNA surface concentrations using fluorescent microscopy.19

Although feasibility of FPBA has been demonstrated with DNA microarrays, this approach has yet to be used for antibody microarrays or to be compared directly to use of more standard fluorescent labels. A direct comparison of FPBA to other fluorescent detection techniques is critical to ascertain the fluorescent gain afforded by this method, thereby benchmarking FPBA to other approaches. Additionally, since antibody microarrays rely on different materials, procedures, and principles than DNA microarrays, it is necessary to ascertain whether FPBA is suitable for an antibody microarray format and to determine independently the limit of detection and dynamic range associated with FPBA in this format. Moreover, the procedures employed here are expected to yield even higher sensitivity than was reported by Hansen et al. due to optimization of the polymerizing formulation by replacement of the PEGDA-based monomer formulation with one based on a more reactive acrylamide mixture, ultimately improving the reaction characteristics in surface-mediated eosin polymerizations.21,22

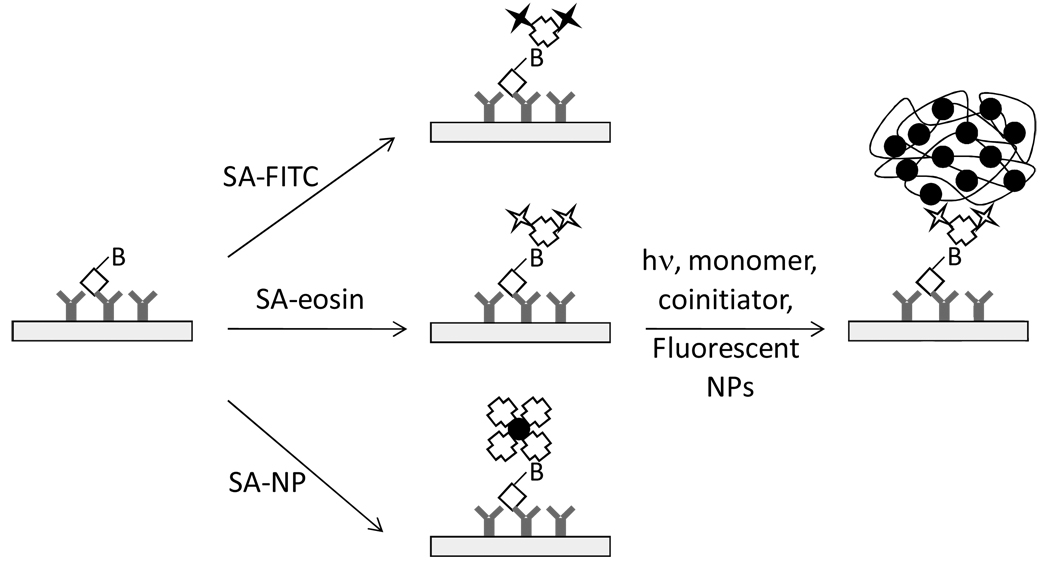

In this communication, FPBA is extended to an antibody array format and is compared directly to detection using other fluorescence methods. Antibody microarrays often employ either direct biotin-labeling of all proteins in a sample or indirect labeling strategies in which a biotinylated detector antibody is used.13 Here, sensitivity and dynamic range are assessed in two model systems; firstly, biotinylated antibody is printed in a dilution series to represent a chip with different concentrations of biotin-labeled target bound; secondly, chips are printed with goat antibody as a capture probe, and the slides are contacted with various concentrations of biotinylated anti-goat antibodies, representing a biotin-labeled analyte. For FPBA, a streptavidin-eosin conjugate is incubated with the test surface resulting in localization of eosin photoinitiator molecules specifically where streptavidin binds biotin. An aqueous acrylamide monomer formulation containing N-methyldiethanolamine (MDEA) as a coinitiator, 1,2-vinyl pyrrolidone as an accelerator and yellow/green fluorescent nanoparticles is contacted with the surface and forms a highly fluorescent polymer film upon polymerization associated with exposure to visible light. This method is compared to using streptavidin-FITC (SA-FITC) or streptavidin-functionalized yellow/green NPs (SA-NPs) to bind fluorescent moieties to surface-immobilized biotinylated molecules (Figure 1). Fluorescent intensities from each method are measured using a fluorescent stereomicroscope, and in the case of polymerization-based detection, film thicknesses are measured and the limit of detection yielding a film visible to the unaided eye is recorded.

Figure 1.

In FPBA (middle pathway), SA-eosin binds to biotin-functionalized biomolecules on the test surface. Then, in a subsequent reaction step, eosin initiates polymerization, generating a highly fluorescent polymer film. FPBA is compared to fluorescent detection using SA-FITC (top pathway) and SA-labeled fluorescent NPs (bottom pathway), neither of which employs a polymerization step.

Experimental Section

Materials

Epoxy-functionalized glass slides (SuperEpoxy 2), 2x Protein Printing Buffer and solid printing pins were purchased from Telechem International, Inc. Streptavidin (SA), biotin-labeled anti-goat IgG (biotin-α-goat IgG) produced in rabbit, Cy3-labeled anti-goat IgG (Cy3-α-goat IgG) produced in rabbit, anti-mouse IgG produced in goat (goat IgG), bovine serum albumin (BSA), 10x PBS, HABA/avidin reagent, pronase, 40% acrylamide/bis-acrylamide (19:1) in water, 1-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone (VP), N-methyldiethanolamine (MDEA), and hematoxylin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Eosin isothiocyanate, streptavidin-FITC (SA-FITC), streptavidin-functionalized yellow/green NPs (SA-NPs) (40 nm diameter) and non-functionalized yellow/green NPs (yellow NPs) (40 nm diameter) were purchased from Invitrogen. Streptavidin-eosin conjugate (SA-eosin) was prepared in-house as described previously21 by reacting eosin isothiocyanate with amines on the protein’s surface. A Cy3 Scanner Calibration slide was purchased from Full Moon BioSystems. Water was purified using a Milli-Q system. NP stock solutions were sonicated for 2 minutes immediately before use.

Preparation and characterization of microarray chips

Antibodies were printed onto epoxy-functionalized glass slides by a VersArray Chip Writer™ Pro (Bio-Rad) with a solid pin yielding spots of 435 (+/−5) µm diameter. The surface epoxy groups form a covalent linkage with amine and thiol groups present on the antibodies. Chips were prepared with a dilution series of biotin-α-goat IgG in a 9 × 5 array containing five replicate spots of 8 decreasing antibody concentrations, and a 9th row with no antibody that served as a negative control suitable for evaluating non-specific polymerization. The highest print concentration was 85 µg/mL biotin-α-goat IgG in 1× printing buffer and 0.5 mg/mL BSA. Lower print concentrations were prepared by serial 1:3 dilutions into 1× print buffer with 0.5 mg/mL BSA, and the 9th row contained only 0.5 mg/mL BSA. Slides were printed at approximately 45% humidity and stored unprocessed at room temperature. To estimate the surface concentration of bound antibodies achieved with each print concentration, identical procedures were followed to print Cy3-α-goat IgG. A Cy3 Scanner Calibration slide was used to convert fluorescence readings into surface density of Cy3 molecules, which was then converted into surface density of biotin-α-goat IgG (using the Cy3/antibody reported by Sigma). This approach assumes that biotin-α-goat IgG and Cy3-α-goat IgG bind the surface with similar affinities. A second set of chips was also prepared in the same manner as described above except with five replicate spots of unlabelled goat IgG at 100 µg/mL in 1X print buffer with 0.5 mg/mL BSA and five replicate spots containing only 1x print buffer and 0.5 mg/mL BSA as a negative control.

Binding reactions

The biotin-α-goat IgG dilution chips were rinsed to remove unbound antibody, then the slides were incubated with 10mg/mL BSA in 1X PBS for 1 hour, followed by rinsing. All rinsing steps comprise three 2 minute rinses in PBS with rapid rocking. The biotin-α-goat IgG dilution chips were then reacted 1 hour with either 1 µg/mL SA-eosin, 1 µg/mL SA-FITC, or 1.8 nM SA-NPs each in 1x PBS with 5mg/mL BSA, followed by rinsing, then dried with nitrogen. In addition, several concentrations of SA-NPs were tested ranging from 0.18 to 18 nM; however, none were found to yield significant positive signals, as defined by the criteria described below. All reagent incubations were done using Chip Clips from Whatman to form wells on the chips and gentle rocking was used. For the slides printed with goat-IgG, blocking was performed as described above, then the chips were contacted with varying concentrations of biotin-α-goat IgG (10−6, 10−7, 10−8, 10−9, 10−10, 10−11, 10−12, and 0 M) in 1x PBS and 5 mg/mL BSA for 1 hour, followed by rinsing. The chips were then reacted for 1 hour with either SA-eosin or SA-FITC at 1 µg/mL in 1x PBS and 5 mg/mL BSA, followed by rinsing and dried with nitrogen. The slides reacted with SA-eosin were then further processed as described later.

Fluorescence characterization of initiator surface density

Since eosin is a fluorophore in addition to a photoinitiator, eosin surface density was characterized prior to polymerization using an Agilent Technologies Microarray Scanner. A Cy3 Scanner Calibration slide was used to convert fluorescence readings into surface density of eosin fluorophores. Significant positive signals are defined as having a signal to noise (S/N) of at least 3, where [S/N = (signal-background signal)/(standard deviation of the background signal)], with background signal defined as the signal from spots printed with BSA alone.

Polymerization-based amplification

The Chip Clip System from Whatman was used to form wells around each of the 2 arrays per slide, and 400 µL of monomer was added to each well. The monomer formulation is 40 wt% acrylamide (5 mole% of that being N,N'-Methylenebisacrylamide), 210 mM MDEA, 35 mM VP, and 30 nM NPs in water. For five minutes prior to and throughout the entire 30 minute light exposure, the slides were placed in a plastic bag with argon flow to reduce oxygen in the atmosphere. The light source was an Acticure (Exfo) high pressure mercury lamp with an in-house internal bandpass filter (350 nm - 650 nm) and an external 490 nm longpass filter (Edmund Optics) positioned at the end of a light guide and a collimating lens. The light intensity was measured as 40 mW/cm2 using an International Light radiometer. After polymerization, unreacted monomer was removed with three five minute water rinses, followed by air drying. Each condition investigated was polymerized on at least three eosin arrays in three separate polymerization sessions. Polymer film thicknesses were measured using a Dektak 6M surface profilometer with 12.5 µm diameter tip and a stylus force of 1mg. Instrument specifications indicate accuracy down to 5 nm thickness, which is taken as the limit of detection for film measurements. Pictures of the microarray films were taken with a digital camera after hematoxylin staining of the films to improve contrast for the images. Hematoxylin staining did not make any additional films become visible that were not already visible prior to staining.

Fluorescence characterization of reacted chips

FITC and yellow/green NP fluorescence was measured using a Leica MZ FLIII stereomicroscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) with the blue filter set. Exposure times in the range of 5 seconds to 60 seconds were used, depending on the intensity of the fluorescent signal. A Cy3 Scanner Calibration slide was imaged at each exposure time to identify appropriate scaling factors for the different exposure times, such that all data could be plotted using the same arbitrary fluorescence scale. Significant positive signals are determined as described above.

Results and Discussion

Demonstration of PBA in an Antibody Array Format

Antibody arrays are a critical tool in protein biomarker identification, and as protein marker expression profiles are better understood, antibody microarrays will likely take an even more prominent role in disease diagnosis. Previous reports of PBA have focused on DNA microarrays, and to our knowledge no previous demonstration of this method has been shown for antibody arrays. Differences between DNA and antibody arrays are likely, considering the more complex nature of protein-antibody binding interactions compared to the relatively well understood and more easily manipulated DNA hybridization process.

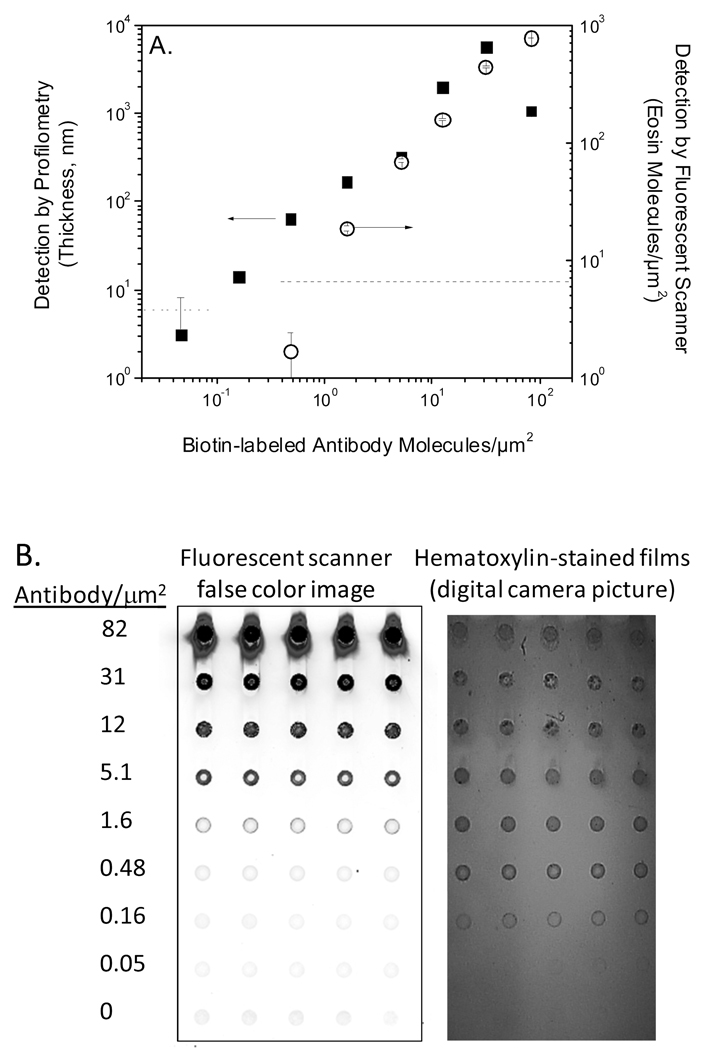

To demonstrate feasibility of PBA for antibody detection and to ascertain the sensitivity and dynamic range of PBA in this format, dilution chips were prepared with 9 × 5 arrays containing five replicate spots of 8 decreasing biotin-α-goat IgG (bi-antibody) concentrations, and a 9th row with BSA and no antibody that served as a negative control suitable for evaluating non-specific polymerization. Each print solution contained 0.5 mg/mL BSA to maintain a sufficient protein concentration for acceptable spot morphology. These chips were reacted with streptavidin-eosin, then scanned on a microarray scanner to measure the surface density of eosin bound to each spot, and finally exposed to monomer and light, yielding acrylamide films with thicknesses that correlate to the antibody-biotin surface density (Figure 2A). Polymer films were detected both by eye (Figure 2B) and by profilometry down to 0.16 (+/− 0.01) bi-antibody/µm2 (or 40 zeptomole target biomolecules). Additionally, since eosin has fluorescent properties (λexc = 524 nm) that are well matched to the Cy3 channel (532 nm laser) present on most microarray scanners, a comparison is readily made between PBA as evaluated by both profilometry and visual inspection versus biodetection with a fluorescently labeled streptavidin (SA-eosin) as measured by a microarray scanner. Detection of biotin-antibody using SA-eosin yielded a tenfold poorer detection limit of 1.6 (+/− 0.1) biotin-antibody/µm2 (Figure 2A) compared to PBA. Both methods displayed a dynamic range spanning approximately 2 orders of magnitude. These results indicate that PBA is well suited for antibody microarrays. Further, in this antibody microarray format, better sensitivities are achieved using PBA in the absence of instrumentation than using a fluorescent streptavidin and a microarray scanner costing on the order of $100,000.

Figure 2.

(A) Biodetection assessed by film thickness measurements of films generated by PBA (■) compared to fluorescence measurement of eosin surface density using a microarray scanner (○). The dashed lines represent the threshold for detection of significant signal on each instrument. (B) A representative slide from (A) is used to compare a scanner-generated false color image of eosin fluorescence to a digital camera image of stained polymer films.

These detection limits compare favorably with previous reports concerning PBA. The 0.16 (+/−0.01) bi-antibody/µm2 detection limit observed here constitutes a two to three order of magnitude improvement in sensitivity compared to the 10–60 targets/µm2 detection limit reported by Hansen et al. for visible light induced PBA biorecognition of biotin-labeled DNA oligos.19,21 Part of this improvement in sensitivity is likely due to the fact that each antibody is coupled to approximately 20 biotin molecules, whereas only one biotin is attached to each DNA oligo. However, due to steric hindrance, it is impossible for all 20 biotin molecules to be accessible for simultaneously binding streptavidin. An additional contribution to the improved sensitivity is associated with the choice of an acrylamide-based monomer formulation which has been shown to yield thicker films and generate films from fewer surface initiators compared to the PEGDA-based formulation employed by Hansen et al.21,22 Sikes et al. have also employed PBA to detect biotinylated oligos, and reported a detection limit of 10 zeptomoles when using a UV-sensitive photoinitiator, a hydroxyl-ethyl acrylate monomer formulation, and a specially coated biosensor surface.20 A limitation of the method presented by Sikes et al. is that the films are not mechanically stable, prohibiting any post-polymerization rinsing steps or profilometry measurements. The 40 zeptomole detection limit reported here is on the same order of magnitude as that reported by Sikes et al., yet with the advantages of visible light initiation, the ability to utilize a wide variety of substrates and the generation of mechanically stable polymer films.

Incorporation of Fluorescent Nanoparticles to Generate Fluorescent Films

Fluorescence detection has become the standard in microarray assays because of its ease of use and the availability of a wide variety of fluorophores with distinct emission wavelengths.2,9,13 Approaches that increase the fluorescence signal in response to a biorecognition event enable the detection of lower abundance antigens; or alternatively, may permit the use of less expensive and perhaps even field-portable fluorescence detectors, while maintaining high sensitivity. Initial efforts to incorporate fluorescence into PBA focused on growing polymer films from fluorescent monomers. Unfortunately, this tactic proved problematic due to side reactions in which the fluorescent monomer either initiates non-specific polymerization in the absence of eosin, or instead is quenched or bleached by the other components of the reaction. Hansen et al. have demonstrated that PBA may be used to encapsulate fluorescent nile red NPs in PEGDA films, yielding strongly fluorescent films whose fluorescence correlates with surface density of DNA-biotin molecules.19 Since the fluorophores embedded in the polystyrene nanoparticles are shielded from monomer and coinitiator, problematic side reactions are reduced.

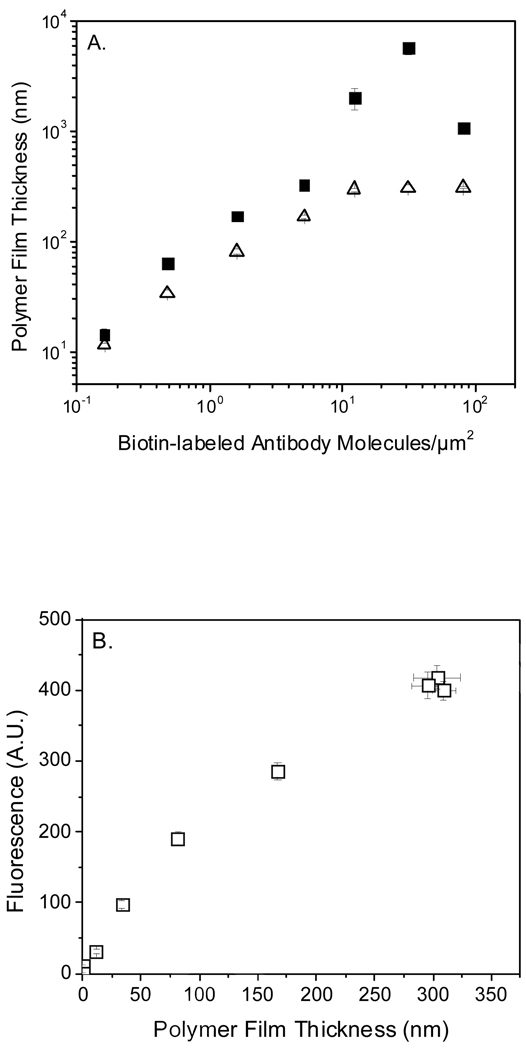

Here, a strategy for FPBA is investigated in which yellow NPs are incorporated into acrylamide films. Yellow NPs were used because they are available commercially with or without streptavidin attached. Adding yellow NPs to an acrylamide monomer formulation resulted in up to a 2-fold reduction in film thickness in the dynamic range of film growth and a larger reduction in film thickness at higher biotin surface densities, yet no decrease in the limit of detection was observed (Figure 3A). The decrease in thickness is likely due in part to attenuation of light from the NPs in the monomer, reducing the incident initiating light, resulting in lowered surface initiation efficiency. As expected, film fluorescence correlates well with film thickness across all biotin densities investigated (Figure 3B). The lowest surface bi-antibody concentration detected was 0.16 (+/− 0.01) bi-antibody/µm2 which yielded 11 (+/−1) nm fluorescent films that were detected on a fluorescent stereomicroscope with S/N greater than 6. Strikingly, FPBA in conjunction with a fluorescent stereomicroscope enables ten-fold better sensitivity than using fluorescent streptavidin (SA-eosin) and a much more costly microarray scanner (Figure 2), despite the fact that the fluorescent stereomicroscope is a much less sophisticated and considerably less expensive instrument.

Figure 3.

(A) Effect on film thickness of incorporating fluorescent NPs into the polymer films. Compare films polymerized in the presence (△) and absence (■) of NPs. (B) Correlation of film fluorescence with film thickness for the films polymerized with NPs in (A).

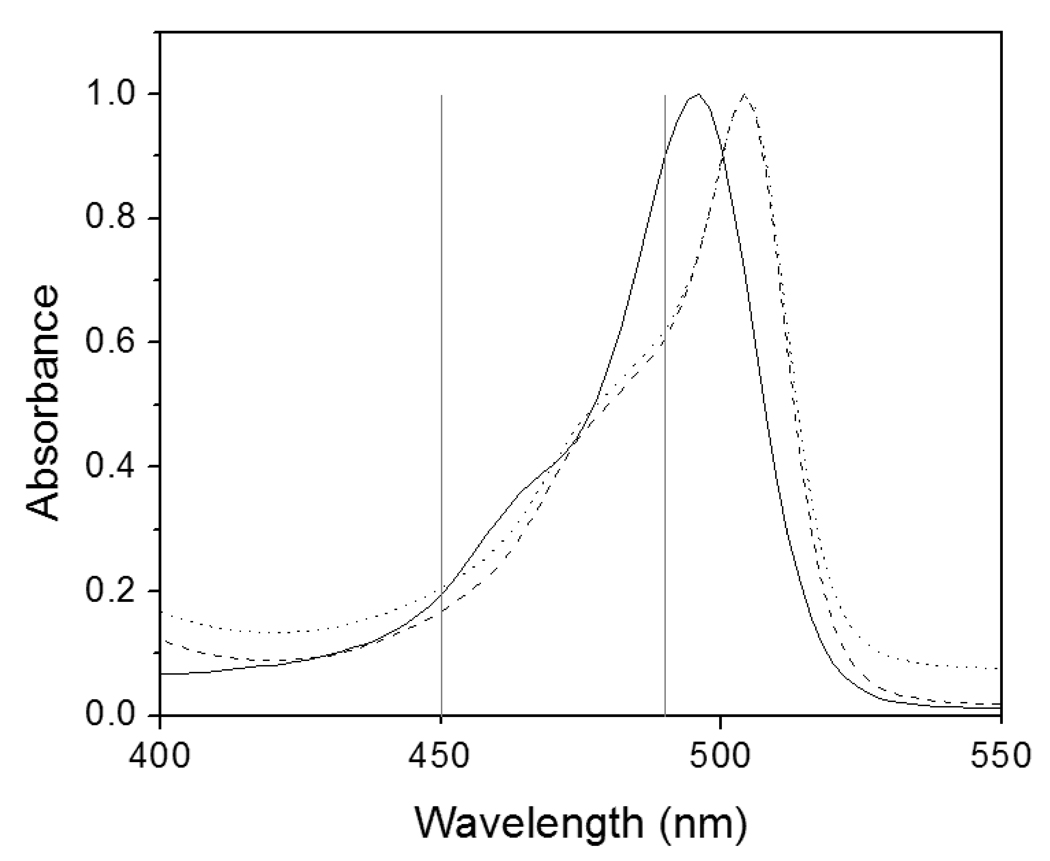

Comparison to Other Fluorescent Methods on a Biotin-Antibody Dilution Chip

Although feasibility of FPBA has been demonstrated previously,19 it has never been directly compared to other fluorescence detection methods. To ascertain the amount of fluorescent gains achieved using FPBA, this method was compared to detection using SA-FITC, a common fluorescent SA conjugate, as well as yellow SA-NPs that directly bind surface-immobilized biotin without requiring any polymerization reaction (Figure 1).14 All three fluorescent species have similar absorption spectra that are appropriate for excitation with a blue filter set on the stereomicroscope (Figure 4). Each method was used to generate a fluorescent response to a dilution of bi-antibody surface densities. FPBA shows an approximately 2-order dynamic range and detected down to 0.16 (+/− 0.01) bi-antibody/µm2, while SA-FITC had a detection limit of 31 (+/− 1) bi-antibody/µm2 and SA-NPs failed to achieve any significant positive signal under these conditions (Figure 5). Calculations of fluorescence/bi-antibody indicate that in the dynamic range of FPBA there is 33–190 fluorescence/bi-antibody and using SA-FITC there is only 1.4–2.0 fluorescence/bi-antibody, suggesting a 20–140 fold fluorescence gain.Direct binding of SA-NPs performed poorly due to both low signal and high background. This result was not entirely surprising, considering that to our knowledge, only two reports14,15 have indicated successful use of fluorescent polystyrene SA-NPs for microarray fluorescence detection during the many years that this product has been commercially available. More commonly, fluorescent SA-NPs are used in solution-based assays. A possible explanation for the better results of polymerization based amplification compared to SA-NPs is that unmodified NPs contain negatively charged surface carboxylate groups that help stabilize the NPs in suspension, while protein-modified NPs will likely be more prone to agglomeration since the surface contains fewer free carboxylate groups. Agglomerated NPs would likely have slower binding kinetics due to their large size and non-specifically bound agglomerates would be more difficult to remove from the surface. Dye-doped silica and gadolinium oxide particles have also been reported for use with microarrays.23,24 PBA may prove to be a method that allows all these types of fluorescent NPs to be surface-immobilized in response to a biodetection event, without direct protein-labeling of the NPs and the associated problems that may arise.

Figure 4.

Absorption spectra for NPs (- - -), SA-NPs (•••), and SA-FITC (—). In subsequent experiments, these fluorophores are measured by a stereomicroscope with a blue filter that has a 450–490 nm excitation band.

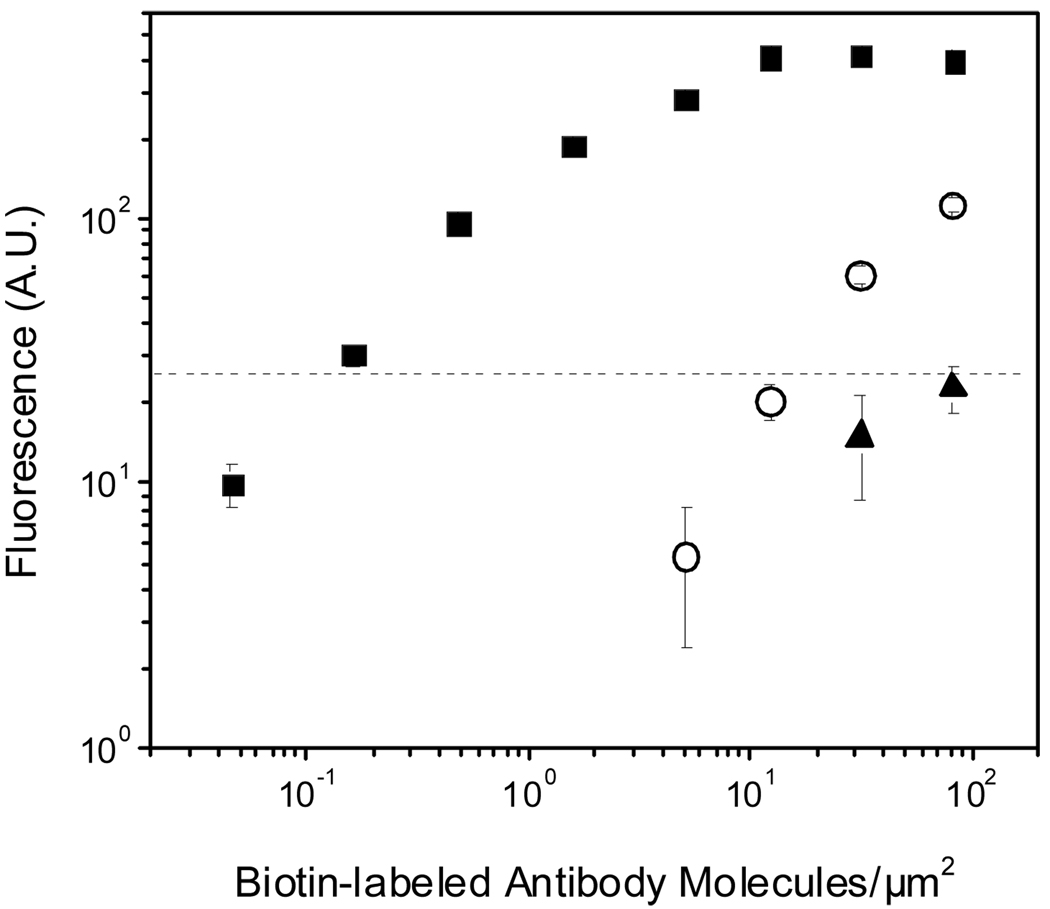

Figure 5.

Comparison of biodetection using FPBA (■), SA-FITC (○), and SA-NPs (▲) each measured using fluorescent microscopy. The dashed line represents the threshold for detection of significant signal (S/N > 3).

Comparison to SA-FITC Using Biotin-α-goat IgG as a Model Analyte

Antibody microarrays frequently employ either direct biotin-labeling of all proteins in a sample or indirect labeling strategies in which a biotinylated secondary antibody is used.13 To assess the ability of PBA to detect varying concentrations of a biotinylated target protein, goat antibody as a capture probe was printed on a chip and the surface was contacted with various concentrations of biotin-α-goat IgG (bi-antibody), which served as the analyte in this experiment. This model system represents a direct labeling approach, though the use of primary and secondary antibodies also provides some insight into application of this method in an indirect labeling approach. Detection limits and dynamic ranges using FPBA versus SA-FITC were compared. FPBA had a 100 pM limit of detection and a dynamic range of four orders of magnitude, compared to only 10 nM sensitivity and two orders of magnitude in dynamic range seen with SA-FITC (Figure 6). These results are consistent with the 100-fold improvement in sensitivity with FPBA compared to SA-FITC observed in Figure 5. Although a dynamic range spanning four orders of magnitude is suitable for most applications, if desired it is possible to shift the dynamic range of PBA by changing the polymerization time or the binding conditions, for example by adjusting the capture probe surface density.19 Additionally, it was found that 10 pM bi-antibody generated a film that was measurable by profilometry (Figure 7A) and was readily detected by eye (Figure 7B), though not yielding S/N greater than 3 on the stereomicroscope. Looking at the 10 nm and 100 nm bi-antibody conditions which are within the dynamic range of both methods, a 13–18 fold gain in fluorescence is observed in FPBA compared to SA-FITC. These results confirm that FPBA detects biotinylated target protein with better sensitivity than does fluor-labeled SA.

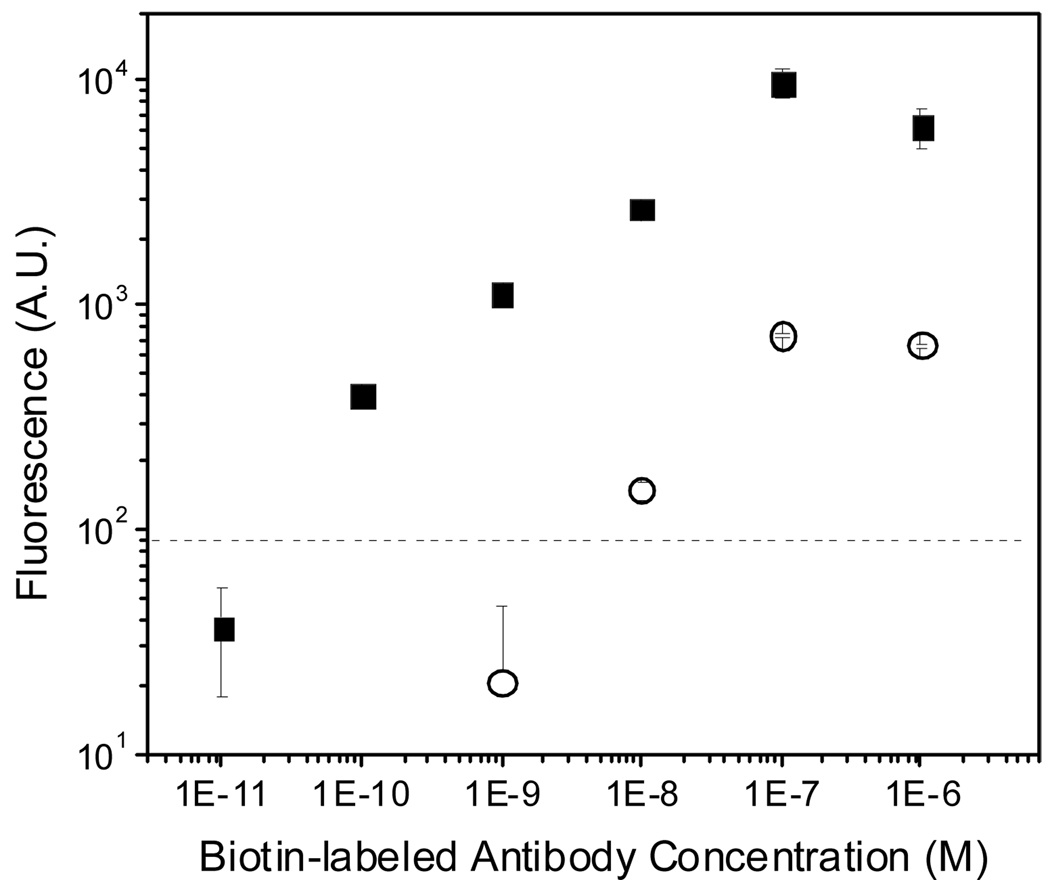

Figure 6.

Compare the use of FPBA (■) versus SA-FITC (○) for detection of biotinylated anti-goat IgG with a fluorescent stereomicroscope. The dashed line represents the threshold for detection of significant signal (S/N > 3).

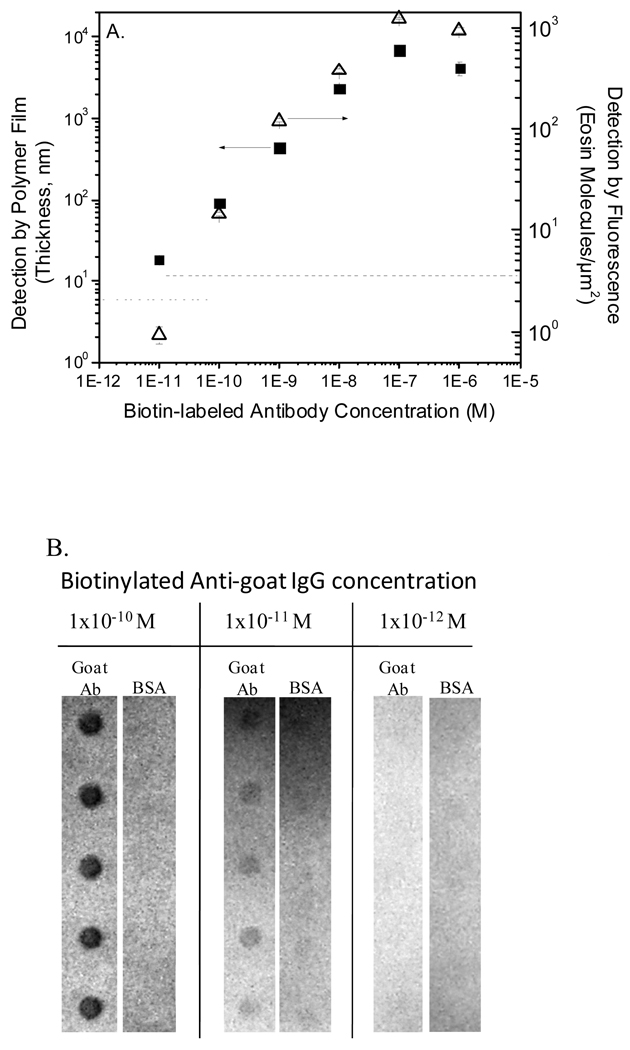

Figure 7.

(A) Detection of biotinylated anti-goat IgG assessed by film thickness measurements of films generated by FPBA (■) compared to fluorescence measurement of eosin using a microarray scanner (△). The dashed lines represent the threshold for detection of significant signal on each instrument. (B) Digital camera images of stained films generated by polymerization-based signal amplification on a representative slide from (A). Five replicate spots are shown for each condition. The visual limit of detection is 10 pM.

In addition to FPBA facilitating more sensitive detection, these experiments also reveal that FPBA enables use of less expensive fluorescence instrumentation. It is possible to make a comparison between detection with FPBA quantified by fluorescent stereomicroscope versus detection with fluorescent streptavidin measured with a microarray scanner. Although SA-FITC and yellow NPs are not well-matched for detection via either the Cy3 channel (532 nm laser) or the Cy5 channel (633 nm laser) present on most microarray scanners, SA-eosin (λexc = 524 nm) is well-matched for the Cy3 channel and therefore is used for this comparison. It is found that FPBA in conjunction with the stereomicroscope (Figure 6) and SA-eosin quantified by a microarray scanner (Figure 7A) yield the same detection limit (100 pM) for fluorescence detection, though FPBA is employing a much less expensive instrument. Further, it is expected that if one were using FPBA to generate films whose fluorescence was well matched to a laser on a microarray scanner, a detection limit on the order of 1pM (100-fold better than that seen with SA-eosin) would be achieved. Notably, films that are visible to the unaided eye are generated down to 10 pM, ten-fold more sensitive than detection with either fluorescence instrument.

Conclusions

FPBA allows for 100-fold better sensitivity than fluorescently labeled streptavidin, indicating that this approach is appropriate for the challenge of detecting low abundance antigens. Incorporation of the FPBA method into a detection assay adds only approximately 30 minutes to the assay time subsequent to the other blocking and antibody binding reactions, which are each themselves 30 minutes up to several hours, depending on the application. Moreover, due to its high sensitivity, FPBA enables a transition towards less expensive and perhaps even field portable fluorescence detection instrumentation, an advantage that is especially valuable as antibody microarrays take a more prominent role in diagnostics and pathogen screening. Uniquely, this method also generates a macroscopic film that allows instrument-free qualitative detection, which would facilitate a gateway testing approach in which only samples presenting a positive visual result would need to undergo quantification by fluorescence detection. This gateway testing strategy would be useful for screening tests for bacteria or toxin targets that are not expected to be present at any level in the sample. Additionally, based on FPBA’s suitability for both DNA and antibody arrays, it is anticipated that FPBA also may be amenable for sensitive detection in other array types including reverse phase protein arrays and carbohydrate arrays.

Acknowledgment

This material is based upon work supported by NIH R21 CA 127884 and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to HJA. Also, this work has been supported by the State of Colorado and the University of Colorado Technology Transfer Office.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pollard HB, et al. Protein microarray platforms for clinical proteomics. Proteomics: Clin. Appl. 2007;1:934–952. doi: 10.1002/prca.200700154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angenendt P. Progress in protein and antibody microarray technology. Drug Discov. Today. 2005;10:503–511. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray S, et al. Classification and prediction of clinical Alzheimer’s diagnosis based on plasma signaling proteins. Nat. Med. 2007;13:1359–1362. doi: 10.1038/nm1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown A, Lattimore J, McGrady M, Sullivan D, Dyer W, Braet F, dos Remedios C. Stable and unstable angina: Identifying novel markers on circulating leukocytes. Proteomics: Clin. Appl. 2008;2:90–98. doi: 10.1002/prca.200780090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lv L, Liu B. Clinical application of antibody microarray in chronic kidney disease: How far to go? Proteomics: Clin. Appl. 2008;2:989–996. doi: 10.1002/prca.200780134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gehring AG, Albin DM, Reed SA, Tu S, Brewster JD. An antibody microarray, in multiwell plate format, for multiplex screening of foodborne pathogenic bacteria and biomolecules. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008;391:497–506. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu JQ, Dyer WB, Chrisp J, Belov L, Wang B, Saksena NK. Longitudinal microarray analysis of cell surface antigens on peripheral blood mononuclear cells from HIV+ individuals on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Retrovirology. 2008;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamesdaniel S, Ding D, Kermany MH, Davidson BA, Knight PR, III, Salvi R, Coling DE. Proteomic analysis of the balance between survival and cell death responses in cisplatin-mediatedot otoxicity. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:3516–3524. doi: 10.1021/pr8002479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borrebaeck CAK, Wingren C. High-throughput proteomics using antibody microarrays: an update. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2007;7:673–686. doi: 10.1586/14737159.7.5.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kricka LJ, Master SR, Joos TO, Fortina P. Current perspectives in protein array technology. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2006;43:457–467. doi: 10.1258/000456306778904731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caiazzo RJ, Maher AJ, Drummond MP, Lander CI, Tassinari OW, Nelson BP, Liu BCS. Protein microarrays as an application for disease biomarkers. Proteomics: Clin. Appl. 2009;3:138–147. doi: 10.1002/prca.200800149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lv L, Liu B. High-throughput antibody microarrays for quantitative proteomic analysis. Expert Rev. Proteomic. 2007;4:505–513. doi: 10.1586/14789450.4.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wingren C, Borrebaeck CAK. Antibody microarray analysis of directly labeled complex proteomes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008;19:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiese R. Analysis of several fluorescent detector molecules for protein microarray use. Luminescence. 2003;18:25–30. doi: 10.1002/bio.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Järrås K, et al. ENSAM: Europium nanoparticles for signal enhancement of antibody microarrays on nanoporous silicon. Proteome Res. 2008;7:1308–1314. doi: 10.1021/pr700591j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haab BB. Methods and applications of antibody microarrays in cancer research. Proteomics. 2003;3:2116–2122. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen UB, Geierstanger BH. Multiplexed sandwich assays in microarray format. J. Immunol. Methods. 2004;290:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geho D, et al. Pegylated, streptavidin-conjugated quantum dots are effective detection elements for reverse-phase protein microarrays. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:559–566. doi: 10.1021/bc0497113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen RR, Avens HJ, Shenoy R, Bowman CN. Quantitative evaluation of oligonucleotide surface concentrations using polymerization-based amplification. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008;392:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2259-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sikes HD, Hansen RR, Johnson LM, Jenison R, Birks JW, Rowlen KL, Bowman CN. Using polymeric materials to generate an amplified response to molecular recognitionevents. Nat. Mater. 2008;7:52–56. doi: 10.1038/nmat2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen RR, Sikes HD, Bowman CN. Visual detection of labeled oligonucleotides using visible-light-polymerization-based amplification. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:355–362. doi: 10.1021/bm700672z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avens HJ, Randle TJ, Bowman CN. Polymerization behavior and polymer properties of eosin-mediated surface modification reactions. Polymer. 2008;49:4762–4768. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2008.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou X, Zhou J. Improving the signal sensitivity photostability of DNA hybridizations on microarrays by using dye-doped core-shell silica nanoparticles. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:5302–5312. doi: 10.1021/ac049472c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nichkova M, Dosev D, Gee SJ, Hammock BD, Kennedy IM. Microarray immunoassay for phenoxybenzoic acid using polymer encapsulated Eu:Gd2O3 nanoparticles as fluorescent labels. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:6864–6873. doi: 10.1021/ac050826p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]