Abstract

The brutal murder of James Byrd Jr. in June 1998 unleashed a storm of media, interest groups, high profile individuals and criticism on the Southeast Texas community of Jasper. The crime and subsequent response—from within the community as well as across the world—engulfed the entire town in a collective trauma. Using natural disaster literature/theory and employing an ecological approach, Jasper, Texas was investigated via an interrupted time series analysis to identify how the community changed as compared to a control community (Center, Texas) on crime, economic, health, educational, and social capital measures collected at multiple pre- and post-crime time points between 1995 and 2003. Differences-in-differences (DD) analysis revealed significant post-event changes in Jasper, as well as a surprising degree of resilience and lack of negative consequences. Interviews with residents conducted between March 2005 and 2007 identified how the community responded to the crisis and augmented quantitative findings with qualitative, field-informed interpretation. Interviews suggest the intervention of external organizations exacerbated the severity of the events. However, using strengths of specific local social institutions—including faith based, law enforcement, media, business sector and civic government organizations—the community effectively responded to the initial threat and to the potential negative ramifications of external entities.

Keywords: James Byrd murder, Collective trauma, Social capital, Ecological analysis

Introduction

Disasters, extreme events and collective traumas provide situations that demand a multi-disciplinary response. After such an experience, it is not difficult to imagine figurative and literal ripples spreading across the social landscape affecting communities at every level. Undoubtedly, these events impact the entire web of human endeavor including economics, health, education, social order, infrastructure, and the well-being of the individual, family and neighborhood. The impact is not only short-term but may linger into the future and have a profound effect on identity, social relationships, and future policies. Clearly, these phenomena require a sophisticated ecological analysis as we seek to understand, analyze and prepare for future negative events.

Further complicating research on disasters is a certain amount of ambiguity mixed with expansiveness of the term itself. Different kinds of natural disasters, such as earthquakes, floods and hurricanes, may be similarly destructive, but the latter two may offer forewarning that can lead to possible preparation and evacuation. Collective disasters may also include man-made events such as technological accidents and purposeful terrorist activities. Tierney (1989) has defined disasters as “collective stress situations that happen (or at least manifest themselves) relatively suddenly in a particular geographic area, involve some degree of loss, interfere with the ongoing social life of the community, and are subject to human management” (p. 12).

The present study examined an incident that largely qualifies as a disaster according to Tierney’s (1989) definition, but may most accurately be described as a “social trauma”. The June, 1998 murder of James Byrd Jr. in Jasper, Texas had the potential to destroy an entire community both from immediate civil unrest and longer-term racial and economic repercussions. While most disaster response research examines the individual as its stated or implied unit of analysis (see, e.g., Norris et al. 2002b), the present investigation of the impact of the Byrd murder sought to measure the effect on and the response of the community more broadly (cf. Wright et al. 1990).

The Community and the Trauma

Jasper, Texas is a rural city of over 8,000 people located approximately 130 miles northeast of Houston. This Deep South community is geographically isolated, fitting many regional cultural and demographic stereotypes: economically challenged, a manufacturing work force, high levels of religious observance, and based on 2000 Census figures, 44% Black, 48% white, 8% of Hispanic origin, with educational levels significantly below the state average (City-Data.com 2004).

On June 6, 1998, James Byrd Jr., a 49 year-old African-American, was walking home after attending a family event. Three white men offered to give him a ride but the cloaked gesture became apparent as they assaulted, savagely beat and chained him to their pick-up truck, eventually dragging him to his death. The trauma besetting the community grew intense in the days after the murder, as the severity of the crime quickly ignited a political, social and media storm that gripped Jasper. The world’s attention and condemnation focused on the town, as it was inundated by national and international media. The FBI investigated; interest groups representing racial fringes set up camp inside town limits. The Black Panthers arrived, armed and in combat fatigues, and high profile personalities (e.g., Jessie Jackson) descended on the community, intent on making Jasper and the heinous event a rallying point for their respective agendas. In the middle of this, the community struggled to control its own destiny, its identity, and the safety of its citizens. Normal life came to a halt as Jasper attempted to respond to the world’s reaction to the crime.

While individuals and organizations from outside descended on Jasper, most residents avoided the public rallies sponsored by external entities. Instead, residents displayed yellow ribbons in sympathy and in token of peace. Residents and relatives of the killers vocally decried the murder. More than 1,000 people joined in a prayer vigil of reconciliation. Commercial, social and political normalcy was disrupted as all activity centered on the crime and the storm that followed.

The Present Study

Our ecological analysis of the Byrd crime examined the community level response to a murder that escalated into a social crisis. Building on theories developed in natural disaster research and borrowing several core constructs as a starting point to comprehend this “social disaster”, we utilized a time series design and DD analysis to explore the ecology of Jasper’s response to this event by examining crime, economic, education, medical and social capital measures. While we desired the objectivity and statistical comparison provided by these quantitative measures, we also sought detail and insight that might not be available except through in-depth interviews and so semi-structured interviews supplemented the quantitative data collection. Thus, our study included both quantitative and qualitative methods, a convention particularly suited to understanding the complex and multi-faceted nature of community and disaster.

The natural disaster literature suggested that Jasper’s response would display an initial surge of cooperation, unity and altruism within the community (cf., Kaniasty and Norris 1993, 1995, 1999; Raphael 1986). Prior research indicates that victims serve as their own best responders and resources (Dynes and Drabek 1994; Gist et al. 1998), leading to a tendency to look within for “deliverance” as well as for a marshalling of resources (Wenger 1985). High levels of mutual helping often materialize, and previous community conflicts recede. Race, ethnic and social class barriers crumble, at least temporarily, during this stage of “post-disaster Utopia” (Bolin 1989; Drabek 1986; Eranen and Liebkind 1993). Scenarios of heightened communal cooperation are theorized to have “therapeutic features”, including the possibility of taking the community “beyond its pre-existing levels of integration, productivity and capacity for growth” (Fritz 1961, p. 692; Quarantelli 1985). Thus, we hypothesized an initial strengthening of social groups and a general strengthening of networks between formal and informal social groups. Research also indicates that short-term responses are frequently followed by a “second disaster” once the immediate threat passes and life returns to a sense of normalcy (Raphael 1986). This may include the reemergence of pre-crisis psychosocial tensions and fissures that had been hidden in the immediate post-disaster phase, as well as longer-term effects on the mental health of individuals (see, e.g., Norris et al. 2002a, b) that would play out in changes in the community over time. Thus, we anticipated that negative effects of the crime would ripple through the community and show up in both subtle and explicit ways in the subsequent years.

Methods

This study was designed in two distinct but cumulative phases. The first was a quantitative analysis employing a wide variety of community-level measures to ascertain the character of the community both before and after the crime. Surveying the community across a large number of social indicators was enlarged by the second, qualitative phase, using interviews conducted by the first author to explore the effects on and reaction by the community in a more open-ended fashion. Each phase is described below.

Quantitative Phase

We used an interrupted time series design to examine indications of the changes in the community resulting from the murder. This was accomplished by collecting a variety of community measures touching a breadth of sectors. Raudenbush and Sampson (1999) suggest the need to develop “ecometric measures” as community level parallels to “psychometrics” at the individual level. These measures can more accurately capture the ecological condition of the community as a unit in its own right, rather than constructs that are merely aggregates of individual ones. We pursued a methodological assessment of human ecological settings such as neighborhoods and communities. The variables examined conformed to several guiding principles: (a) the variables measured community (ecometric) behavior as much as possible, rather than being an aggregate of psychometrics, (b) the variables tapped several aspects of the community (e.g., crime, commerce, social), and (c) the variables are practical and generally obtainable in most communities. The goal was to secure a community-wide (by geography and sociologic segment) perspective of any potential changes. A smaller subset of similar measures was used by Golec (1980), Fowler (2001), and Pennebaker and Banasik (1997) after various social disasters. This phase of research followed the model and logic of the methodology utilized by Putnam (2000) in his study of social capital by examining trends in civic participation in organizations, leagues and other social groups. Our goal was to cast a wide net, including focusing on several of these concepts, to survey a range of community measures in an attempt to see what, if anything, had changed in the community in the aftermath of the Byrd murder.

The five quantitative constructs identified included “crime”, “economics”, “education”, “health” and “social capital”. When possible, several measures were used to evaluate each construct. Violent crime, domestic disputes and driving under the influence citations were collected as measures of “Crime”. The “Economic” effect was measured with number of houses sold, construction tax, retail tax and lodging tax revenues. School attendance was the sole reliable measure for ascertaining the effect on “Education”. Hospital admissions, births, suicides and mental health caseload comprised the “Medical” construct. “Social capital” was assessed in this study as the number of marriages and divorces.

Archival data were collected from an assortment of public records and from diverse sources, including formal public filings, real-estate figures, organization budgets, hospital records, crime data and economic reports. Community level data were collected at multiple pre- and post-crime time points surrounding June, 1998. Statistics from the years between 1995 and 2003 were recorded to capture trends both before and after the event (resulting in 108 observation points; 42 months before and 66 months after the murder). Data were obtained from local hospitals, county records, uniform crime reports, sheriff’s offices, school districts and Texas department of vital statistics. Local employees and record keepers were extremely helpful in aggregating the specific data from public records. Monthly data, as opposed to yearly, were collected whenever possible. This permitted more accurate, granular level capture of trends and effects that might otherwise have been lost through via aggregated annual data.

Observations were designed around a non-manipulated (i.e., unexpected and unplanned) treatment/event—the crime—and as such renders traditional experimental controls impossible. This fact, as well as the inability to control for changes in the independent variables (crime rates, tax revenues, hospital admissions, marriages, etc.) by experimental design, led to the selection of a control community to use as an analytic control. Criteria for the control community included similarity in terms of geographic region, population size, ethnic composition and economics. Center, Texas fit this logical and demographic similarity and served as the control community in the interrupted time series design. Table 1 provides a demographic comparison of Jasper and Center, but beyond these, the communities have comparable cultural, historical and economic qualities. Both are rural, relatively isolated communities that are heavily dependent on tourism and the logging industry. All variables collected for Jasper were also gathered in the control community.

Table 1.

Treatment and control community demographics

| City | Jasper, TX | Center, TX |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 8,247 | 5,678 |

| Median age (years) | 37.3 | 36.9 |

| Median household income | $30,902 | $29,112 |

| Per capita income | $15,636 | $15,186 |

| Racial demographics | ||

| Caucasian (%) | 45.7 | 46.7 |

| Hispanic (%) | 8.6 | 18.1 |

| Black (%) | 43.9 | 34.2 |

| Other (%) | 5.2 | 11.1 |

| University/college | No | No |

| County seat | Yes | Yes |

The DD approach is a useful analytic tool perfectly suited to estimate causal relationships when several years of pre- and post-event data are available (Meyer and Blanchflower 1994). DD estimation consists of identifying a specific intervention (or treatment) in time-series designs and has grown in popularity in econometric and policy evaluation scenarios (see Freeman 2007; Kreft and Epling 2007; Kuziemko 2006). The DD method is ideal for longitudinal analysis when isolating significant effects in interrupted time series and similar designs. This analytic approach compares the difference in outcomes after and before the intervention (or treatment) for groups affected by it to this difference for unaffected groups. Together with the use of a control community, the DD analysis controls for cyclical and regional variables that might confound the findings. Compared against a sufficiently similar control community, the DD analysis identifies whether trends changed, as well as the statistical significance of those changes. It is useful in identifying change only, not necessarily correlation or causation between the change and the treatment. The DD analysis was used to compare the difference between the change (difference) in pre-murder to post-murder (June 1998) rates for the various crime, economic, education, health and social capital measures in both Jasper and Center, Texas. This statistical method was applied to each of the dependent variables. With a community acting as a control and the methodological strengths of pre- and post-measures inherent in a time series design, this method is extremely robust.

Analytic Strategy

An Ordinary Least Squares regression of the change in average violent crime (or other crime, economic, health, education and social capital measures) regressed on a set of dummy variables were used to determine whether any of the pre- to post-crisis differences between Jasper (treatment community) and Center (control community) were significant. The following model is estimated for measures in the treatment community and the control community:

|

For the Jasper crime, y is the change in variable rates (violent crime, hospital admits, marriage licenses, etc.) for the “pre” (January 1995–June 1998) and “post” (July 1998–December 2003) time frame. The control community (Center), by definition, does not experience the community trauma/crisis. The dummy variable “jas” captures the violent crime rate between Jasper and Center (the control), regardless of the time period. “Post” captures changes in violent crime from pre- to post-crisis. “Jaspost” is the difference in time and place between the control and treatment and as such is the “Differences in Differences” effect.

Qualitative Phase

Personal, in-depth interviews were conducted to fill out the picture of the Jasper community’s response to this event. While quantitative data examined changes up to 5 years post-murder, the interviews were conducted approximately 7 years after the event, between March 2005 and 2007. This stage of the project involved interviewing 15 people representing a variety of segments of the community. These individuals were members of the community before, during, and after the event, and included the mayor, police chief and sheriff, religious and minority group leaders, businessmen, relatives and neighbors of the victim, among others. Interviewees were chosen because of their prominence and active participation in the community response. Participants were solicited for involvement in the research and given a straightforward explanation as to the intent of the interview (e.g., to identify how the community responded and reacted after the Byrd murder). Interviews were taped recorded.

The interviews were built on a series of semi-structured, open-ended questions, allowing for further elaboration or probes as the research unfolded. Questions were framed along a number of general categories including: general effect of the crime/trauma, community response, and individual reaction. The interviews provided insight to interviewees’ assessments of the community’s response to the event, what the community did to cope in response, assessments of the fairness of media coverage, confidence and trust in community institutions, including the police, city government, the media, church leaders, community organizers (both inside and outside groups), race relations and tolerance of minorities, and attributions for what accounted for the event and its aftermath.

Results

Quantitative Findings

Crime

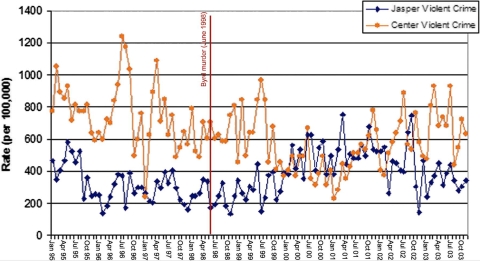

A combination of FBI uniform crime measures, in addition to locally obtained Driving under the Influence (DUI) infractions and jail population, were used to ascertain the change in crime in Jasper as compared to the control community, Center. The DD analysis is shown in Table 2. The rate of violent crime in Jasper after the Byrd murder was significantly different (p < .0001) than the rate of crime before. There is an increase in the slope of violent crimes after the event (compared to pre-event) in the magnitude of 254.52 violent crimes per 100,000 people. Figure 1 presents a visual representation of the DD statistical analysis, and shows the average monthly violent crime rates of both Jasper and Center before and after the event. While average monthly violent crime decreased in Center after the Byrd murder, it increased in Jasper. Examination of the first 12 months immediately following the murder (July 1998–June 1999, as illustrated in Fig. 2) revealed no increase or decrease from the previous trend in Jasper, nor compared, over the same time frame, to the control community. Jasper’s increase in violent crime took place during the five and a half years following the event. Moreover, the changing dynamics of post-event violent crime trends occurred after the first 12 months and, therefore, outside the immediate impact stage of the event, as would be expected after the “altruistic community” dissipated into a “second disaster”, as explained by Raphael (1986).

Table 2.

Differences-in-differences estimates for Jasper, Texas measures

| Coefficients | Differences-in-differences effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Place diff. | Time diff. | ||

| Crime measures | |||

| Violent crime | −429.35c | −169.03c | 254.52c |

| Domestic disputes | −38.55c | −5.53 | 7.65 |

| DUI | −37.95c | 45.42c | −26.02a |

| Jail population | −542.94c | −139.39c | 317.44c |

| Economic measures | |||

| Houses sold | 0.0081c | 0.0008 | −.0022b |

| Construction tax | −60.45 | −34.54 | 56.36 |

| Retail sales tax | 135.24 | 352.25 | 89.91 |

| Lodging tax | 7.59c | 1.69 | −0.71 |

| Education measure | |||

| School attendance | −0.2659 | 2.2387 | −0.1968 |

| Health measures | |||

| Hospital admissions | 0.0000585 | 0.0049357c | −0.003657c |

| Births | −0.0005854a | 0.0005923b | −0.000101 |

| Suicide | 0.0000122 | −0.00000808 | 0.0000027 |

| Mental health | −0.0127c | −0.00684c | 0.00409c |

| Social capital measures | |||

| Marriage | −0.0000293 | 0.0001497 | 0.0000203 |

| Divorce | 0.0004659b | −0.0008759c | 0.0011073c |

a p < .05, b p < .005, c p < .001

Fig. 1.

Pre- and post-event violent crime averages in Center and Jasper

Fig. 2.

Monthly violent crime incidents in Jasper and Center 1995–2003

Compared to Center, the rate of incarceration (i.e., “Jail Population”) in Jasper increased significantly (p < .0001) after the event. As with violent crime, the trend in the immediate 6 months following the event was down, indicating a reduction in this crime measure during the impact and immediate post-impact (the emergence of the “altruistic community”) stages. This temporary reduction was offset by increases in the jail population in the ensuing years.

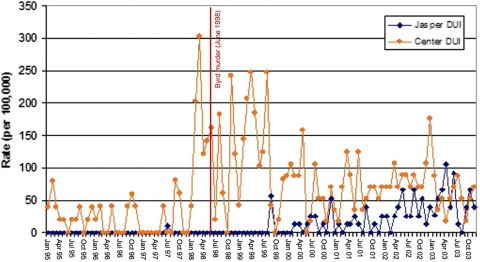

The slope in DUI citations changed from pre- to post-event. The coefficients manifest significant (p < .0001) slope differences in Jasper compared to Center (−37.95) and from pre-event and post-event (45.42). The rate of DUI citations changed after the murder in Jasper, but less than what was expected. As with the other crime constructs, the change in the slope of DUI citations did not occur until 12–18 months after the event (see Fig. 3). Furthermore, there is no corresponding increase in DUI citations in Jasper during a period of dramatically increased DUI citations in Center within the first year following (July 1998–July 1999) the Byrd murder.

Fig. 3.

Monthly DUI incidents in Jasper and Center 1995–2003

The most intimate measure of criminality used in this study, domestic disputes, showed no significant change before and after the event. While there was a difference in rates between Jasper and Center, the DD analysis did not manifest a significant change over time between the two towns. The p-value (p = .407) suggests that the difference was not significant—that is, that the pre-post difference in Jasper was not different from the pre-post difference in Center. The crime did not result in higher or lower domestic dispute rates.

The Economy

The Jasper economy was driven by tourism, retirement relocation and the timber industry. Two of these three had the potential to be negatively impacted due to the stigma (e.g., Jasper as a racist, red-neck place) associated with the crime. Economic reality was measured by number of houses sold, construction tax, retail sales tax and lodging tax revenues. DD analysis was used to examine the change, if any, in the economic performance of the community before versus after the Byrd murder. Table 2 lists the differences between Jasper and Center, before and after the murder and the DD effect.

Houses Sold

Jasper had a higher, per capita, number of houses sold than Center throughout the entire time of investigation (see Fig. 4). In fact, the rate of houses sold is not significantly different than zero from before to after the event. However, when comparing the difference between Jasper and Center from pre- to post-event, the rates of sales were slightly less than expected. This significant (p < .005) finding suggests a slight economic effect on the Jasper housing market.

Fig. 4.

Houses sold in Jasper and Center 1995–2003

Construction, Retail Sales and Lodging Tax Revenues

Each of these tax revenue measures displayed no significant DD effect. This means that the rates of tax revenues per capita were not different from before June 1998 than their levels after June 1998. The event had little measurable economic effect when measured by tax revenues.

Education Effects

Educational measures are generally very difficult to obtain since most are compiled only on an annual basis (standardized test scores, graduation rates, college enrollment, etc.). This proved problematic when looking for changes occurring on a monthly or quarterly basis. Fortunately, Center and Jasper maintained attendance records for public schools. This single measure became our quantitative indicator. When evaluating pre- to post-event change, the coefficients in the DD table (Table 2) revealed that the slight drop in attendance in Jasper was not significant. It appears that educational behavior—in terms of school attendance—was not negatively affected by the crime.

Health Effects

While not comprehensive, hospital admissions, births, suicides and mental health caseloads provided insight to help determine if the murder had some effect on the health of citizens. Table 2 presents the DD results for the health variables. The coefficients are stated in terms of per capita comparisons.

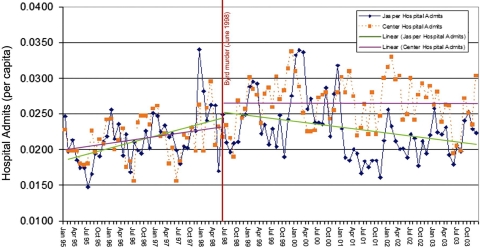

Hospital Admissions

A statistically significant DD coefficient of −.003657 (p < .001) indicates that hospital admissions in the months following the event decreased compared to before the event and compared to the control community. Figure 5 displays monthly rates with trend lines added for Jasper pre-event (R 2 = .215) and post-event (R 2 = .1067). Trend lines for Center are also displayed to illustrate Jasper’s differential trend from the control, as well as from its own pre-crisis rate. This is another way of visually demonstrating the DD effect.

Fig. 5.

Hospital admission rates in Jasper and Center 1995–2003

Births

Following the murder, birth rates did not show any increase or decrease relative to pre-event rates and the control community. While there were slight significant changes between communities, as well as an increase in post-event rates, the DD effect was not significantly different than zero. Figure 6 illustrates that births in both communities increased slightly from pre- to post-event time periods, but the relative change was nearly constant.

Fig. 6.

Pre- and post-event birth rate averages in Jasper and Center

Suicides

There was minimal change in suicide rates between time periods (pre- or post-event), and there were very few differences between communities. The DD effect (.0000273, p = .908) was not significant, reflecting the fact that this event did not correspond with either an increase or a decrease in suicides.

Mental Health

The data displays a trend of gradually declining number of mental health clients per capita over the period of study. This trend in Jasper is mirrored by the same trend in Center. The significant difference between Jasper and Center and between pre and post-event time periods are evident from the coefficients in Table 2, as well as in Fig. 7. The DD effect of .00409 (p < .001) is small but significant. These data indicate that the per capita number of mental health patients after the crime was higher than what would be expected by the control community and pre-event trends (see Fig. 8). While the number of mental health patients fell in both communities after the crime, the drop in Jasper was not as precipitous as in Center. In other words, the decrease in mental health patients was not as large as expected.

Fig. 7.

Mental health clients in Jasper and Center 1995–2003

Fig. 8.

Pre- and post-event mental health client averages in Jasper and Center

Social Capital Effects

Marriage and divorce tap into the fundamental unit of community (the family) and are ultimate measures of the trust, functionality, reciprocity and cohesion of that unit. Table 2 contains the DD analysis results for marriages and divorces, the two measures of social capital examined.

Marriage

The “Place Difference” coefficient (−.0000293) indicates Jasper’s lower marriage rate independent of pre- or post-event time periods. The “Time Difference” coefficient (.0001497) describes the increase in both communities’ post-event marriage rates. Neither of these was significant.

Divorce

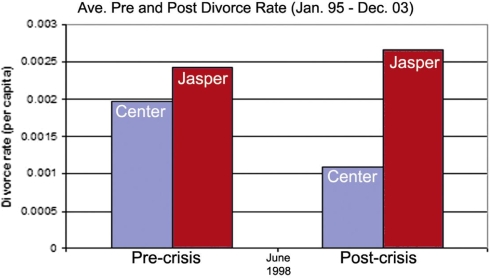

The post-event divorce rate in Jasper increased significantly (p < .001) beyond pre-event levels. This increase, as indicated by the DD Effect coefficient (.0011073), exceeded what the trend in the control community estimated. Figure 9 provides an illustration of this change. As can be seen, the divorce rate in Center decreased from the pre-event to post-event period. During the same periods, Jasper’s divorce rate increased.

Fig. 9.

Pre- and post-event divorce averages in Jasper and Center

Qualitative Findings

Interviews revealed several core themes as Jasper responded to the crisis following the Byrd murder. While some themes overlap with the quantitative findings, the interviews helped identify phenomena and trends that might otherwise have escaped notice. Interviewees identified the role of local social institutions, the importance of communication, the influence of the media, community self-reliance, economic challenges, and the importance of reserves of social capital in crisis. Each of these will be considered in turn.

Proximate Primary Social Institutions

The crime and community trauma commanded the concentrated attention of Jasper’s primary formal and informal social organizations. Not only did these groups perform their own function, but they also joined in unprecedented cooperation throughout the course of the recovery period. Community leaders developed a strategy and deflated the potential negative effects of outside interest groups. Specific responses were made on the fly, but the leaders and groups involved were established early on. Equally important, relationships between these groups took shape early, permitting venues to determine actions to specific challenges.

The group with the most ubiquitous presence in the lives of community members was the Ministerial Alliance—a group of ministers from the various churches who had, for years, created a network that crossed racial, economic and religious lines to serve as an informal social resource for this highly religious community. They possessed the trust of both the average citizens as well as other prominent institutions, including law enforcement and the business community. At the invitation of the Sheriff and the Mayor, the entire Ministerial Alliance was quickly tapped to take on a central role. One of the ministers recalled, “There was so much misinformation in our community that the Mayor and law enforcement came to our meeting and told us everything they knew—and it was amazing what they told us. And they wanted us to get out into the community (and communicate) the truth as they knew it at that time…. We were welcome to go to the Mayor’s and Sheriff’s office whenever we wanted. He shared with us everything he knew. He trusted us and, in return, we trusted him”.

The Minister’s Alliance jointly identified protective responses to the wave of outsiders who came into their community, and was brought completely into the circle of decision makers. The Ministerial Alliance thus assumed a central role in every aspect of the community response.

Communication

Clear, accurate, timely and ongoing communication to members of the community was a primary objective and required continual concerted effort. Community leaders in Jasper quickly recognized the importance of communication with residents. From the earliest stages of the event, miscommunication threatened to spread fear throughout the community.

Jasper leaders instituted a line of communication through the Ministerial Alliance, which became the mouthpiece to the community. Very little filtering took place from the police to members of the Ministerial Alliance, and this candid communication also extended to the media. The Sheriff’s office freely shared information in an effort to pre-empt speculation and false reporting. This strategy also won the favor of the media.

In the midst of the trauma, Jasper leaders were unified in the messages they sent. Messages, instructions and strategy employed by law enforcement, the city, and the Ministerial Alliance were communicated in coordination and alignment with one another. Residents did not receive competing messages. Instruction to close shops and to avoid downtown during rallies sponsored by the KKK or the Black Panthers, for example, was first issued by the Sheriff’s office, seconded by the Mayor and emphasized by personal visits by members of the Ministerial Alliance.

Information was transmitted to the general community through the traditional outlets, including press conferences, newspaper and local radio. Jasper also employed more intimate means, such as ministers communicating with church congregations. Non-traditional information outlets combined raw information with a level of personalization and trust by virtue of the recipient’s relationship with the communicator.

Media

The media descended upon Jasper and left a lasting impact on the town. The media was much more involved than an unbiased spectator. Evidence of sensationalism, disrespect for the community’s wishes, and incorrect and inaccurate representations, are easy to identify. The negative stigma associated with Jasper is a result, to some degree, of the media. Leaders and individuals obliged to interact with the media quickly learned to be cautious, if not to avoid the media outright. They also identified ways to manage the media and even employed strategies to win the media over.

Both black and white interviewees spoke of a common theme. “When the national media got here they were making us to be pop bellied, snuff dippin’, beer drinking red necks, east-Texas bigoted police. Ignorant, uneducated…Typical stereotypes”. This view of the media extended into every segment of society. A black minister evaluated their motives as well as their gradual evolution:

They came looking for a red-neck, prejudiced community. A community that was vilifying each other. A community that was for racism. A community that was not together. This was going to be their example, I guess, of what the whole South was like, of what east-Texas was like.

Citizens recognized that they were not entirely free of the cloud of racial inequality that was being cast over their town. Many recognized that the national media was creating an injury that would not easily be rectified, “The injury to the community was in the instant perception the rest of the world had about Jasper.… The headline all the way across the two pages in inch and a half type said ‘The Town that Shamed America’. The Austin American Statesman had a story about what a racist town this was, that it was a beehive or Klan activity. I had never seen evidence of any Klan activity”.

Jasper was ill equipped to handle the media immersion brought on by the heinous crime. This applied not only to their ability to mount a public relations campaign to answer the media portrayal as a racist, red-neck bastion but more simply to adjust to the quantity of news crews inundating their otherwise quiet town. In the small community of 5,000 people, the swarm of media was literally like an invasion. “We had never seen any of this before. There were news trucks taking up the whole courthouse square, double trucked with news trucks from all over the world”.

Jasper’s interaction with the media can be described as measured trepidation at best. The president of the Ministerial Alliance said ‘If you men don’t talk to these reporters someone’s going to talk to them.’ And there were lots of people coming from out of town who wanted some publicity who were making up all kinds of stories who did not know fact from fiction…. So we began doing them. As for those who were not spokespersons, the Mayor advised, “‘If you don’t know what to say, don’t talk.’ We finally got that message out to the people.”

Leaders involved in the response learned and adjusted positively to the reality of the situation. The Sheriff’s relationship with the media began on tenuous grounds but was flipped almost completely around by an ingenious but gutsy decision by the Sheriff. Going against established practices of all other law enforcement agencies, including consulting FBI representatives, he pursued a path of communication that changed the media dynamics by making allies out of initial adversaries:

In Texas the media has a right to have a copy (of the affidavit of probably cause) but they have to request it in writing and you have ten days to respond…we didn’t make them wait, they didn’t even have to ask for it…that was something very smart because the press went from stereotyping us as one way (to) setting down with us.

This course of action was in harmony with the Sheriff’s larger commitment to open communication that involved the Byrd Family, the Ministerial Alliance and now the media. This offering, demonstrating a willingness to work with the news media, began to win them away from their preconceived stance. “We found that the longer the people stayed in town the more honest they became in their reporting because they really saw who we were. We weren’t this phony community who was putting on a show while they were there. They really expected to find a town that was filled with hatred and we weren’t that way”. Unfortunately one of the characteristics of the news media is a short-term focus. News bites and surface level evaluations, both of which are limited by time or space, did not serve the sophisticated nature of Jasper’s culture.

Extra-Community Interest Groups

In Jasper, the national and international media firmly established themselves as an interest group pursuing, in the eyes of the community, an agenda as self-serving as any of the other political or racial based organizations. To a large degree their presence attracted other groups who sought a stage to proclaim their ideology. The mayor summed up the challenge, “Media kept coming in. Black Panthers, KKK, NAACP all came in. NAACP came in and had a meeting. Groups did not come in to help, (but) only because the media was there and provided coverage”.

As with the media, these groups came with their own ideas of how Jasper should respond and what the murder should represent. Jasper leaders recognized that these agendas frequently did not match their own, “Different agendas were coming in that were trying to over ride ours. We had to confront those. We had a differing opinion (from the outside groups) of what we should do as a community. That was our primary objective, to focus on keeping peace and harmony in the community. Speaking as one and not having any divisions between white and black”.

The Ministerial Alliance took center stage running interference and providing a buffer against these outside groups. They were clear and unified in their agenda, desiring peace and healing in their community. “You look at the outside influences that come into any community…we realized that this was our problem. We had to provide the solutions to it—the long term solutions after the media had packed their bags and trucks and the lights and cameras were gone, and after Al Sharpton and Jessie Jackson and Kueze Enfume and all those folks who showed up…the local community people realized that this was our community”. Jasper became host to the cadre of contemporary black leaders. The Ku Klux Klan and Black Panthers came quickly thereafter and the political environment became potentially explosive and violent.

As each group or individual arrived in Jasper, the Ministers, the Sheriff and the Mayor determined the individual or groups best equipped to confront the arriving group. Summing up this strategy a community leader explained, “When the Panthers came, the black leadership listened to them and met them and talked to them. And when the KKK came, the white leaders did exactly the same thing”. It was determined that black ministers were the best counter to influential personalities. “(They) confronted Jessie Jackson and Al Sharpton because as ministers we felt that the black ministers had to confront the black people and we (white ministers) had to confront the white people. That was very helpful”. The Sheriff, who had his own groups to keep in check, remarked about the effectiveness of this strategy, “That put Jessie Jackson and Al Sharpton’s fire out. It was a non-issue. They did not stay very long”.

The Economy

The gruesome murder and negative media spotlight posed a serious challenge for the already fragile economic climate. The events threatened to harm the entire community as explained, “We were injured, although it hit the Byrds, all of us were injured, both the white and black community. This is a place where tourists come. People from Houston and Dallas come to Jasper on the weekend. In 1999 we had that stigma on us…they just stayed away. It hurt us economically too. No one wants to locate a company in a racist state”. Economic conditions became a focal point for the response of the Mayor. He described the effect: “The community was hurt because we had a mark, a mark of hate. It hurt us for a while. We lost some business that was going to move here. At that time we were on the up rise with bringing business in. It did hurt”.

While difficult to measure quantitatively, especially in terms of opportunity costs, community leaders who were in a position to know explained: “there were some doctors who (had previously accepted positions) who chose not to come. There were some companies who were going to move-in and they chose not to come. Lots of houses went up for sale…people were ashamed to say they were from Jasper. No matter where we went, if you said you were from Jasper people would remember (the Byrd murder)”.

To respond to the stigma and try to counter the effects, the community and the state implemented several efforts directly aimed at the economic rehabilitation of the city. The Governor sent an economic development expert to the local Council of Governments office and unrolled “An Economic Development Strategic Plan for Jasper, Texas”. The economic development position remained in Jasper for more than 5 years after the trauma. The Mayor also organized a taskforce that focused on the economic challenges of the community. While Jasper residents identified negative ramifications of the murder, they engaged in previously unprecedented responses to address their economic status. The conscious addressing of economic disparities within the community and the establishment of an economic development office with a strategic plan customized for Jasper were viewed as positive outcomes of the event.

Preparation and Social Capital

As noted, the Ministerial Alliance represented the most trusted and most ubiquitous social institution in the community. Even prior to the crisis events, this institution permeated the lives of members of the community. It was locally based, locally led and shared the burden and benefits of the events. It was intimately familiar with the culture, needs, assets and potential consequences of the community. The Ministerial Alliance was a repository of social capital, generating strong connections between residents across segments of the community.

The single institution that provided the largest social tie to the majority of the citizenry is the church. The Ministerial Alliance was known to the community, was proximate enough to understand cultural specifics, possessed the trust of the community, and had essential communication, resource and support channels in place. Of particular importance was its inter-connection with many, if not all, of the other institutions and segments of the community. Central to an effective and health community response, it possessed sufficient clout to influence the entire community.

Pre-existing social networks and cross-institutional working relationships provided an essential foundation for effective responses. In Jasper, leaders had taken specific steps years before the Byrd murder and subsequent trauma to reach out and establish social ties with diverse groups that would, unknown at these early times, come together in a necessary congealed fashion to provide sufficient response to a dire crisis. For example, the Ministerial Alliance had frequently worked with the city and with schools on economic and social matters. Most importantly, the Ministerial Alliance crossed racial divisions. When a racially-based crime took place and the community was confronted with an opportunity to split along racial lines, the strength of the Ministerial Alliance networks between white and black ministers was stronger than racial affinity. Both black and white ministers viewed the collective health of the Jasper community more important than their respective racial groups. The trust built with these groups proved vital when the crisis struck unexpectedly and escalated. Instead of being split and adversarial, these groups worked together, often reciprocally sharing and building on the unique strengths each brought to the table to fashion a mutually beneficial response.

Strong social ties were especially important with regard to the immediate families of the victims. The relationship between the community and immediate relatives of the primary victims developed into a relatively amiable and mutually supportive manner. This was not simply a matter of chance but began with appropriate—in message, messenger and timeliness—efforts by the community. The Byrds developed strong friendships and trust with the larger community.

The relationship between the Byrds and the Jasper community (facilitated through the Sheriff’s office) is an excellent example of the benefits sometimes defined as “social capital”. Trust was established early on by the personal visit of the Sheriff. This relationship became the basis for the Black community’s assurance that justice would be carried out. The Byrds’ calming influence and refusal to allow retribution and hate take root along racial lines is a reciprocal measure that cannot be understated. If the Byrds had reacted otherwise, the nature of the trauma in Jasper could likely have resulted in violence and years of racial malice. Instead the Byrds supported the community and the community reciprocally supported the Byrds.

Discussion

Interviews revealed several specific responses as well as strategies employed by the community of Jasper, Texas to respond to the murder of James Byrd and its aftermath. These included building upon existing trust in the religious community—the most prominent local social institution, designing an effective response to external interest groups, and managing the media. The five quantitative constructs that were examined displayed some evidence of change and some evidence of post-event status quo. While the DD analysis could not establish a clear causal connection between the Byrd murder and the changes seen following the crime, it did help identify elements of the community where change occurred from pre-event levels as compared to the control community.

Specifically, our analysis identified several “negative” changes in Jasper in the months and years following the murder. The divorce rate increased and the housing market (as measured the number of houses sold) softened; both are negative indicators of community well-being. Jasper also experienced an increase in violent crime and in its jail population. While the results seem to indicate that Jasper changed for the worse after the Byrd murder, the larger picture presented by the data suggests a remarkable degree of resilience in the form of a lack of effect. More variables displayed no change (either increased or decreased) after the murder than displayed change. For example, lodging taxes, retail sales and construction tax revenues did not appear to suffer; only one of the three indicators used to measure economic health showed a decrease after the murder. General community well-being was also manifest in other segments as well: public school attendance did not change after the murder and domestic disputes showed no signs of change from earlier levels.

This study purposefully employed an ecological point of view for ascertaining the effect on the community. Not only did it tap into the various segments that make up “community”, but also within those constructs we attempted to obtain several variables. This provided a sense of context in which to examine findings. To illustrate this effect, we can review the crime results in Jasper. Two variables indicated an increase in post-event crime, one described a decrease and one described a condition of no change. It is difficult, therefore, to conclude that crime increased in Jasper after the Byrd murder (see also Pridemore et al. 2008, who found no change in monthly homicide rates after the Oklahoma City bombing and the September 11 terrorist attacks).

In addition to longitudinal changes in crime, economics, education, health and social capital measures, in-depth interviews revealed that the community recognized immediate ramifications of the crime and responded by employing deliberate and specific strategies to cope with it. The universal response from individuals involved at various levels included the confession, “It has affected me drastically”. One example of this effect, manifesting itself in both quantitative and qualitative examination, was the impact of the murder on the economy. DD statistical analysis revealed a significant change in pre- to post-crime housing sales. Interviews provided collaboration to the negative economic consequences for the city and provided additional detail about the nature of the effect (decisions of businesses and key professionals not to relocate to Jasper in light of the stigma associated with the crime). The contribution of multiple methods to a richer and more accurate understanding of the situation is further evidence for the need for an ecologically-oriented approach to this issue.

The Importance of Primary Social Institutions

The role of local primary social institutions cannot be understated in the response to a community crisis. The power of local institutions to mobilize, to calm, to direct their own communities, may provide a model and cause a reevaluation of the role of outside rescue agencies and current procedures during disasters and extreme events. Primary proximate social institutions pre-dated the crisis, shared a vested interest in the community, understood important cultural elements of the area, and will remain with the affected population long after the crisis has passed. Outside entities, including helping organizations, on the other hand, are transient, unknown and cannot appreciate the cultural intricacies of the community.

Perhaps it is Jasper’s rural isolation that led the community to be largely self-sufficient, but for whatever reason, a group of leaders from many sectors within the community rose up and reached out to each other after the murder. The result was something of an organic unification of purpose, centering on the well-being and autonomy of their community. One leader recalled this commitment, “There were a lot of people that stepped up to the plate that said this is not going to ruin our community. We will not let it ruin our community”. What is most impressive is the cooperative manner in which this was accomplished. Several social institutions formed something of a loose and informal committee, contributing their own unique strengths and functions toward this objective. Each acted at the request of the others, and all contributed their support toward the common goals. This coordination was purposeful and calculated, but this rarely came about through formal planning meetings or some pre-determined master plan.

While community institutions like the Jasper County Sheriff and other formal and informal organizations played significant roles during the crisis, one social agent evolved very quickly as the hub from which all other institutions, like spokes, connected. The Ministerial Alliance interacted very closely and became a consulting agent to law enforcement, the city, and business sectors. A critical element of these primary social institutions was their proximity to the community. Leaders from the church interacted on a personal basis with the community. While agencies and individuals from outside the community entered Jasper, the citizens took their cues for behavior from these local and trusted institutions. This may be why a Black resident of Jasper was more apt to respond in alignment with a white minister from his small local congregation than to join with the NAACP or Black Panthers. The Ministerial Alliance framed the issue, not as race against race, but as Jasper (citizens of both races) against forces from outside the community—literally Jasper against the world (special interest groups, the media, as well as non-animate elements such as racism, cultural norms, etc.). If not for strong leaders with purposeful efforts to maintain control of the debate, outside elements could have transformed the Byrd murder into a racial spectacle and embroiled the town in a clash of black citizen against white citizen. The ramifications of such would be significant in degree and duration. Instead, the opposite occurred. Citizens of both races joined together in response to concerted efforts by community leaders (also of both races) to oppose extra-community threats.

No one better understood the Jasper community than the local leaders, and Jasper determined that the community possessed the answers to its own crisis. Thus, the solutions were found from sources within the community rather than from sources outside. This comports with the experience following natural disasters where victims are frequently their own best rescuers (Dynes and Drabek 1994; Wenger 1985). Extreme events, disasters and traumas draw a host of experts, helpers and agencies with knowledge and good intentions (Gist et al. 1998). The community of Jasper received these with suspicion and firmly sent them away, relying instead on their own abilities.

The Role of Media

The effect of the media transformed what very likely would have been just another local tragedy affecting a few families into an international event that provided a stage for opposing interest groups. The media made the story and placed themselves squarely in the middle of the community trauma; they were active participants. The effect of the media cannot be overstated. Mass media coverage of major negative community events expands their impact geographically (Wright et al. 1990). As future communities face traumatic situations, they must account for the influence of and imposition of the media (Hawkins et al. 2004).

The media proved itself to be less of an unbiased, objective reporting institution and more like an interest group pursing a definite objective. Indeed, the media appeared to have an agenda to achieve ratings by means of sensationalism, focusing on the dramatic, the atypical and failing to discuss less “sexy” subtleties. This occurs partly from a need to highlight the extraordinary instead of the mundane and modal reality and partially from a lack of knowledge of the cultural specifics, the zeitgeist, history and sophisticated intricacies of the community. It is impossible for a media team to come into a community or situation foreign to them and digest all the relevant information necessary for a thoughtful analysis in the span of 2 days, much less 2 weeks or 2 months.

Crisis, extreme events and disasters are situations that inherently tend to draw out the weaknesses and shortcomings of the media. Communities finding themselves at the center of such circumstances are likely to be overwhelmed with the primary events and not equipped or knowledgeable to respond to the media effects, which can become a crisis of its own accord. In many ways a community may find itself involved in two disasters, one the original event and the second a creation by the media. Jasper quickly recognized the absurdity of controlling the media and sought instead a strategy of management or accommodation. This was not accomplished by surrender but by strategically establishing boundaries of appropriate time, place and topic. Communities must have a plan of action prior to the onset of a crisis on how to manage the media. This includes individuals or agencies that will act as information gatekeepers—individuals who are privy to the most accurate information and who are adept at speaking. These individuals must have the skills not only to convey information but also the emotive tone the community wishes to portray.

Blaming, division and anger are common responses by victims and victim’s families after social and natural crises, and social support often deteriorates over time (Kaniasty and Norris 1993, 1995). In Jasper, the opposite occurred. This was not a matter of chance; several factors apparently facilitated a more amiable and healthy relationship between victims’ families and community institutions. Responses from interviews identify several key factors to establishing quality and supportive relationships: frank, open and proactive communication, involvement of the highest level officials instead of messengers, personal visits made to the families, and an immediate response. Communication with and support for the families took place as soon as accurate information confirmed the victimization of their family member.

Whether speaking of large social institutions like the conglomerate of churches or the smallest and most fundamental like the Byrd family, the pre-existence of sufficient social ties, working experience, trust, and a sense of the common good are essential if a community is to successfully manage a disaster or crisis. If organizations are not familiar with the assets, the capacities and the values of each other, the confusion and natural out-group distrust will severely limit an effective response. It is noteworthy that this working level of social capital was possessed by organizations beyond the traditional public service providers (police, fire and city/government). These organizations had relationships with educational, faith based, business, local media and other prominent segments or local groups. Disasters and crises affect a community ecologically. Responses that simply target food, health and shelter are necessary but not sufficient for long-term social well-being.

Cultural Distinctiveness of Communities

Every community has something of a culture unique to itself. This includes its specific history, legacy, geography, racial and ethnic composition, as well as individual government, economics and demographic qualities. In Jasper, this unique community culture came into play during the unfolding of and reaction to the social disaster. When a disaster or trauma occurs in any locale, the threat is perceived from a culturally-specific lens and the response is informed by cultural, political and social specifics. Jasper’s response is categorically different than if the same event transpired in Detroit. As a Black Jasper resident explained, “You have to be a resident of Jasper to really understand why we didn’t respond with violence”.

Just as it is imperative to understand an individual’s unique psychological characteristics before prescribing a treatment, it is equally necessary to understand the unique qualities—the culture—of a community before prescribing a course of action. Communities have different leadership structures, social institutions, limitations and assets, and protocols for facing challenges. Each has its own future as well, a trajectory that will be affected by the manner in which it responds to a traumatic event.

This point is clearly illustrated by the primary social institution that took the lead in Jasper: the Ministerial Alliance emerged as the major organizer for the community response. Beyond Jasper, every community has its own primary social institution. In some communities this might be law enforcement or the military, while in other communities these institutions may be shrouded with distrust and scandal. The particular response to a community wide trauma in each of these communities will take a different course. As future disasters strike communities, a conscious understanding of their specific community culture must be considered as an important element of an effort in the process of community healing and well-being.

Policy Implications of the Present Analysis

Jasper experienced tremendous pressures and marshaled social assets when facing an unexpected and sudden crisis. It exhibited remarkable resilience and mobilized primary social organizations, sometimes in unique ways, to confront a multifaceted social disaster. Pre-existing intra-community relationships between individuals and organizations were vital for the community’s successful response. The community engaged in a process of self-analysis that eventuated in a strong declaration of community values, beliefs and self-definition.

The process, procedures and ultimate responses of Jasper provides several effective guidelines that can be applied to other communities that find themselves involved in a similar social crisis, whether that crisis is an element of a natural, technological or terrorist event, or is the result of unique social conditions. The following are recommendations for effective response to community trauma/social disaster:

Communication: Quickly establish open and frank communication with those within the effected populations. Dispel rumors and misinformation.

Local leadership and management of the event: The response to the event should be facilitated by the most natural, established and known leaders. These individuals and organizations are most familiar with the culture, unique needs and potential solutions to evolving problems. They also provide a sense of stability and have a level of trust with victims.

Clear and agreed objectives. Disasters are not times of opportunity for pursuing special agendas. All entities involved in the response, especially the leadership, should have a very specific agenda motivating their actions.

Handle the media—win the media: Recognize that the media will mischaracterize the event and the consequences due to their tendency towards sensationalism. Set clear boundaries for the media and provide accurate background information. It is better to have the media as allies rather than adversaries.

Future Directions

The study of disaster, crisis and extreme events has increased in number and importance due to the unique experiences of a post-September 11 reality, as well as the devastating experiences of Gulf Coast hurricanes. Other less traditional disasters, such as the massacres at Columbine High School and Virginia Polytechnic University, indicate a need to understand extreme events, especially their community effects, through a more ecological perspective. The present research, in trying to conceive of the community rather than the individual as the subject of study, uncovered a number of important issues worthy of future research.

Our findings illustrate the need to be sensitive to the important changes (relationships, self-analysis, mobilization of resources, interdependence of social organizations, etc.) taking place within the community—the social elements of the response—but not necessarily evident through usual indicators such as destroyed infrastructure, economic impact, and medical aid. Certainly the social elements have a direct relationship with the factors traditionally accounted for in a disaster scenario; surely these interact with one another, but the present research illustrates the need to consider these social elements in a more prominent way than usual by responders, researchers and policy makers.

The present study also underscores the value of employing both quantitative and qualitative methods in examining the impact of a disaster on a community and demonstrates how both findings can be used to provide greater explanatory value beyond the ability of one or the other individually. The results identified by each method aided in achieving the comprehensive, ecological objectives of the study. Even when statistical and interview analyses identified similar findings, the insight provided by each method benefited greatly from confirmation and elaboration of the other. For example, economic changes identified by DD statistical analysis were confirmed and elaborated upon by responses of community members. Interviewees identified, from personal experience, the impact, the timeline, the causes and the effect of these changes. This multi-disciplinary and multi-methodological approach is necessary in light of the complexity of the event and the sophistication of a community level analysis.

The present study also suggests a need to more fully understand the role of social capital preceding a community crisis, during the response, and as an outcome of the response. It asked an important question that could have important policy, as well as financial, ramifications: Is it possible to measure the impact of an extreme event on a community? If so, what are the appropriate measures to ensure proper evaluation? Finally, are those measures available in smaller communities, the majority of which do not participate in national, longitudinal surveys? Researchers are beginning to wrestle with these concepts and ecological analysis. Recently, Norris et al. (2008) argued that community resilience following a disaster should be conceptualized as a complex system resting on four networked “adaptive capacities”, including economic development, social capital, information and communication, and community competence.

Many important questions arise that were not within the parameters of this research. Are there differences between the effective responses of small communities like Jasper and larger communities like New Orleans? Are there some aspects of community that lead to a healthier or a maladaptive response? What effect does traditional disaster response have on the creation or severity of the “second disaster” stage identified in natural disaster research (e.g., Raphael 1986)? These questions become very relevant in a world where natural disasters are frequent and the technological advances and social dynamics of the world make extreme events more personal, even if geographically located hundreds of miles away. Future investigation will further explore how the advent and evolution of media itself transforms how disasters and extreme events affect us and how we respond to affected individuals and communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michael Ousdahl, Roy Taggueg and Alicia Tieman for their invaluable assistance in collecting archival data and to Daniel Stokols and George Tita for guidance, for assistance with data analysis and interpretation, and for thoughtful suggestions on an earlier version of this report. This article is based on the doctoral dissertation of Thomas Wicke submitted to the School of Social Ecology at the University of California, Irvine.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Bolin R. Natural disasters. In: Gist R, Lubin B, editors. Psychological aspects of disaster. New York: Wiley; 1989. pp. 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- City-Data.com. (2004). Jasper, Texas. Retrieved March 20, 2004 from http://www.city- data.com/city/Jasper-Texas.html.

- Drabek TE. Human systems responses to disaster. New York: Springer; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Dynes RR, Drabek TE. The structure of disaster research: Its policy and disciplinary implications. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters. 1994;12:5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Eranen L, Liebkind K. Coping with disaster: The helping behavior of communities and individuals. In: Wilson JP, Raphael B, editors. International handbook of traumatic stress syndromes. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 957–964. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, K. F. (2001). Community reaction to a social disaster: A newfoundland case study. Doctor Dissertation, Memorial University of Newfoundland (Doctor of Philosophy).

- Freeman DG. Drunk driving legislation and traffic fatalities: New evidence on BAC 08 Laws. Contemporary Economic Policy. 2007;25:293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz CE. Disasters. In: Merton R, Nisbett R, editors. Social problems. New York: Harcourt Brace; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Gist R, Lubin B, Redburn BG. Psychological, ecological and community perspectives on disaster response. Journal of Personal and Interpersonal Loss. 1998;3:25–51. [Google Scholar]

- Golec, J. A. (1980). Aftermath of disaster: The Teton Dam break. Doctoral Dissertation, the Ohio State University (Doctor of Philosophy).

- Hawkins NA, McIntosh DN, Silver RC, Holman EA. Early responses to school violence: A qualitative analysis of students’ and parents’ immediate reactions to the shootings at Columbine High School. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2004;4:197–223. doi: 10.1300/J135v04n03_12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K, Norris FH. A test of the social support deterioration model in the context of natural disaster. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;64:395–408. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K, Norris FH. Mobilization and deterioration of social support following natural disasters. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4:94–98. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K, Norris FH. The experience of disaster: Individuals and communities sharing trauma. In: Gist R, Lubin B, editors. Responses to disaster. Ann Arbor, MI: Braun-Brumfield; 1999. pp. 25–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kreft SF, Epling NM. Do border crossings contribute to underage motor-vehicle fatalities? An analysis of Michigan border crossings. Canadian Journal of Economics. 2007;40:765–781. [Google Scholar]

- Kuziemko I. Does the threat of the death penalty affect plea bargaining in murder cases? Evidence from New York’s 1995 reinstatement of capital punishment. American Law and Economics Review. 2006;8:116–142. doi: 10.1093/aler/ahj005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer BD, Blanchflower DG. A longitudinal analysis of young entrepreneurs in Australia and the United States. Small Business Economics. 1994;6:1–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01066108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ. 60, 000 disaster victims speak: Part II: Summary and implications of the disaster mental health research. Psychiatry. 2002;65:240–260. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.240.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60, 000 disaster victims speak: Part 1: An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–235. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Stevens SP, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche KF, Pfefferbaum RL. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:127–150. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Banasik BL. On the creation and maintenance of collective memories. In: Pennebaker JW, Paez D, Rime B, editors. Collective memories of political events. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1997. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pridemore WA, Chamlin MB, Trahan A. A test of competing hypothesis about homicide following terrorist attacks: An interrupted time series analysis of September 11 and Oklahoma City. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2008;24:381–396. doi: 10.1007/s10940-008-9052-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Quarantelli EL. An assessment of conflicting views on mental health: The consequences of traumatic events. In: Figley CR, editor. Trauma and its wake. New York: Brunner Mazel; 1985. pp. 173–215. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael B. When disaster strikes: How individuals and communities cope with catastrophe. New York: Basic Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Sampson R. ‘Ecometrics’: Toward a science of assessing ecological settings, with application to the systematic social observation of neighborhoods. Sociological Methodology. 1999;29:1–41. doi: 10.1111/0081-1750.00059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney KJ. The social and community contexts of disaster. In: Gist RM, Lubin B, editors. Psychosocial aspects of disaster. New York, NY: Wiley; 1989. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger D. Mass media and disasters. College Station, Texas: Hazard Reduction and Recovery Center; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wright KM, Ursano RJ, Bartone PT, Ingraham LH. The shared experience of catastrophe: An expanded classification of the disaster community. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1990;60:35–42. doi: 10.1037/h0079199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]