SYNOPSIS

Providing efficacious human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention services to HIV-positive individuals is an appropriate strategy to reduce new infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified interventions with evidence of efficacy for prevention with positives (PwP). Through its process of disseminating evidence-based interventions (EBIs), CDC has attempted to diffuse four of these interventions into practice. One of these interventions has been diffused to community-based organizations, whereas another has been diffused to medical clinics serving HIV-positive people. A third intervention was originally developed with HIV-positive individuals using methadone, but uptake by methadone clinics has not occurred. A fourth intervention for HIV-positive adolescents and young adults has had disappointing adoption levels. Unique implementation challenges have been encountered in various intervention settings. Lessons learned in the dissemination of the first four PwP interventions will facilitate implementation of three new PwP EBIs currently being packaged for dissemination.

Implementation of evidence-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention interventions can play a role in reducing HIV infections. Evidence-based approaches should be promoted and implemented, as such interventions can increase the effectiveness of prevention efforts as compared with locally developed interventions with no evidence of efficacy. Evidence-based interventions (EBIs) have demonstrated reductions in risk behaviors among a range of populations,1 including HIV-positive individuals.2 Yet, there remain few EBIs for HIV-positive people, as evidenced by a recent meta-analysis that identified only 11 randomized controlled trials with samples comprising HIV-positive people that demonstrated significant reduction of sexual risk behavior as gauged by condom use.2

Due to more effective biomedical treatments, increasing numbers of HIV-positive people are living longer and healthier lives.3 More than one million HIV-positive individuals currently live in the U.S.4 Thus, providing prevention services to such individuals is an appropriate strategy to reduce new infections.5 To further this strategy, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2003 launched an initiative called Advancing HIV Prevention: New Strategies for a Changing Epidemic, which encouraged HIV prevention for HIV-positive people through education and skills-building as well as integration of prevention into medical care.6

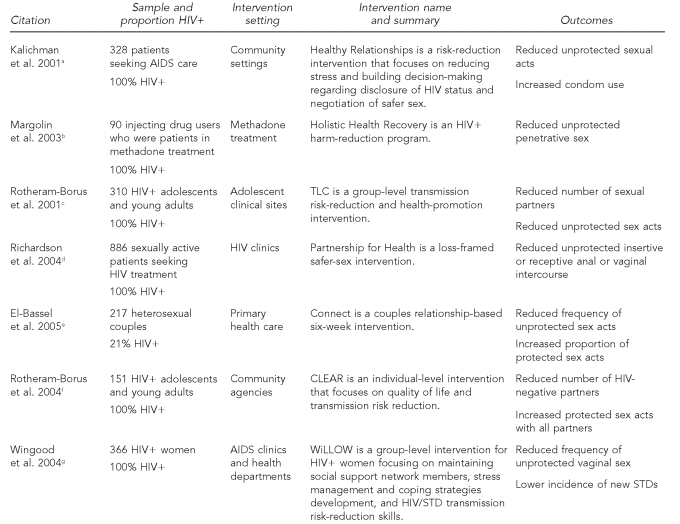

While most people who learn they are HIV-positive reduce their sexual and drug-use behaviors,7–9 some HIV-positive people have difficulty changing their behaviors.8,10,11 A meta-analysis of prevention-with-positives (PwP) interventions found that condom use improved in those interventions that focused on motivational enhancements and behavioral skills.2 CDC has since identified several interventions for HIV-positive people as having evidence of efficacy through the Research Synthesis Project1 and has packaged these interventions through the Replicating Effective Programs project.12 The intervention kits are then given to the Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions (DEBI) project for dissemination. The interventions for HIV-positive individuals now in the DEBI project include Healthy Relationships,13 Holistic Health Recovery,14 Together Learning Choices (TLC),15 and Partnership for Health.16 CDC is currently packaging three additional interventions found to be efficacious for HIV-positive individuals: Connect,17 Choosing Life: Empowerment, Action, Results' (CLEAR),18 and Women Involved in Life, Learning from Other Women (WiLLOW).19 The Figure lists the PwP interventions, along with select intervention characteristics, currently in dissemination or in development for dissemination.

Figure.

Prevention-with-positives interventions currently in dissemination or packaging stages

aKalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M, DiFonzo K, Simpson D, Austin J, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. Am J Prev Med 2001;21:84-92.

bMargolin A, Avants SK, Warburton LA, Hawkins KA, Shi J. A randomized clinical trial of a manual-guided risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive injection drug users. Health Psychol 2003;22:223-8.

cRotheram-Borus MJ, Lee MB, Murphy DA, Futterman D, Duan N, Birnbaum JN, et al. Efficacy of a prevention intervention for youths living with HIV. Am J Public Health 2001;91:400-5.

dRichardson JL, Milam J, McCutchan A, Stoyanoff S, Bolan R, Weiss J, et al. Effect of brief safer-sex counseling by medical providers to HIV-1 seropositive patients: a multi-clinic assessment. AIDS 2004;18:1179-86.

eEl-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, Wu E, Chang M, Hill J, et al. Long-term effects of an HIV/STI sexual risk reduction intervention for heterosexual couples. AIDS Behav 2005;9:1-13.

fRotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Comulada WS, Weiss RE, Lee M, Lightfoot M. Prevention for substance-using HIV-positive young people: telephone and in-person delivery. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;37(Suppl 2):S68-77.

gWingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mikhail I, Lang DL, McCree DH, Davies SL, et al. A randomized controlled trial to reduce HIV transmission risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases among women living with HIV: the WiLLOW Program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;37 (Suppl 2):S58-67.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

TLC = Together Learning Choices

CLEAR = Choosing Life: Empowerment, Action, Results'

WiLLOW = Women Involved in Life, Learning from Other Women

STD = sexually transmitted disease

METHOD OF DISSEMINATION

Through the DEBI process,20 CDC has attempted to disseminate four of these PwP interventions into prevention practice. All four of the interventions were packaged for dissemination within two years of publication in a peer-reviewed journal, to make the materials as timely and relevant as possible. The goal of the DEBI project is to provide intervention resources, training, technical assistance, and capacity-building activities on EBIs to health departments, community-based organizations (CBOs), and medical providers. DEBI is intended to enhance health department and CBO capacity to implement and appropriately adapt evidence-based prevention interventions. CDC accomplishes the DEBI goals in partnership with a broad range of training centers, capacity-building assistance providers, and health departments. CDC gave funding to the University of Texas (UT) Southwestern's Capacity Building Assistance Center (CBAC) to provide technical assistance to agencies and clinics that adopted EBIs for HIV-positive people.

Interventions in dissemination

Four interventions for HIV-positive people are currently in dissemination. Healthy Relationships has been diffused to CBOs, whereas Partnership for Health has been diffused to medical clinics serving HIV-positive individuals. Holistic Health Recovery was originally tested in methadone treatment facilities. TLC may be delivered in a CBO or a health-care setting. A description of each intervention follows.

Healthy Relationships.

Healthy Relationships13 is a group-level intervention for HIV-positive men and women. The five-session intervention is based on social cognitive theory that focuses on building self-efficacy for negotiation of safer sexual behavior; developing and enhancing decision-making skills for disclosure of HIV status to family, friends, and sex partners; and developing skills to maintain safer sex. Disclosure is addressed in four of the five sessions, as this is one of the concerns for HIV-positive people; they are concerned about how, when, where, and to whom they should disclose their HIV status. Disclosure to potential relationship partners is complex, as fear of rejection is not unfounded. The intervention is based on the assumption that building self-efficacy skills around HIV status disclosure potentiates building self-efficacy skills for safer-sex negotiation. The intervention was designed to be delivered by two group facilitators, one of whom should be a peer counselor and the other a mental health professional. One of the two should also be HIV-positive. Those who received the -intervention reported significantly less unprotected sex and increased condom use than did participants in the health-maintenance support comparison group. The intervention sample was primarily African American (74%) and primarily male (70%).

Holistic Health Recovery.

Holistic Health Recovery14 is an intervention for HIV-positive people who inject drugs and who were enrolled in methadone maintenance. The comparison condition in the original study included daily methadone, substance abuse counseling, and a six-session HIV risk-reduction intervention. The intervention included all elements of the comparison condition, with the addition of a manual-guided group session based on harm-reduction principles, which was provided twice a week. Intervention topics included skills training for harm reduction and relapse prevention, coping, medication adherence, and increased participation in medical care. Clients assigned to the intervention condition were significantly less likely to engage in high-risk sex and drug-related behaviors. The intervention sample was primarily male (70%).

TLC.

TLC15 is an intervention for HIV-positive adolescents and young adults. Participants were provided with three group-level modules (Staying Healthy, with 12 sessions; Acting Safe, with 11 sessions; and Being Together, with 12 sessions). The sessions were designed to enable clients to cope with an HIV diagnosis, adopt health-promoting behaviors, disclose serostatus appropriately, and become active in their health-care decisions. Those who participated in Staying Healthy demonstrated increased coping skills and positive lifestyle changes (e.g., balanced diet, exercise, and adequate sleep), while participants in Acting Safe demonstrated 82% fewer unprotected sex acts, 45% fewer sex partners, 50% fewer HIV-negative sex partners, and 31% less substance abuse. The intervention sample primarily comprised racial/ethnic minority groups (27% African American and 37% Latino) and was primarily male (72%). CDC decided to condense the modules so they would have eight sessions each. In addition, CDC encouraged agencies to implement Staying Healthy and Acting Safe and to consider Being Together as an optional module.

Partnership for Health.

Partnership for Health16 was an intervention tested in six public HIV clinics in California with HIV-positive individuals who had multiple sex partners at baseline. Medical providers at the clinic conducted the intervention after receiving a four-hour training course. Clinicians were taught to deliver a “loss-framed” message, which focused on the consequences of not reducing sexual risk to those who report risk behavior. The dialogue also included discussions of the importance of forming a health and prevention partnership, and creating safer-sex goals. Clinic staff distributed brochures that emphasize the importance of safer sex and gave examples of risk reduction, and posters were mounted in waiting and examination rooms to reinforce prevention messages. The prevalence of unprotected anal and vaginal intercourse was reduced 38% after brief, ongoing prevention counseling from primary care providers. There was no effect for patients who had one sexual partner at baseline, underscoring the need to tailor the intervention to various patient needs. The intervention sample was primarily men who have sex with men (MSM) (74%), with the majority of clients being either white (41%) or Latino (37%).

Interventions being packaged for dissemination

CDC is currently packaging three additional interventions for HIV-positive people for dissemination. Descriptions of these interventions are as follows.

Connect.

Connect17 is a couples-level intervention for heterosexuals at risk for HIV. The intervention teaches couples communication techniques and HIV risk-reduction awareness and skills. It also addresses the power dynamics of the relationship that may serve as barriers to safer sex behaviors. Findings from the efficacy study revealed a reduction in risky sexual behaviors and an increase in the proportion of protected sexual acts at both three months and 12 months post-intervention. Based on the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) Risk-Reduction Model and the Ecological Perspective,21,22 the intervention consists of six sessions: an orientation to assess the safety of a relationship, followed by five couples sessions. Because sexual risk behavior among HIV-positive people is often a shared decision within couples, this intervention is needed in the continuum of EBIs available to agencies working with HIV-positive individuals. In the research trial, a high proportion of the sample included HIV-positive people (21%), as well as primarily lower-income African American and Latino individuals.

CLEAR.

CLEAR18 is an HIV-prevention and health- promotion intervention for adolescents and young adults aged ≥16 years living with HIV. This individual-level intervention was developed based on lessons learned from implementing TLC. CDC restructured TLC's Staying Healthy and Acting Safe modules to be delivered as an individual-level intervention. CLEAR helps adolescents and young adults decrease risky sexual behavior. Based on social action theory, CLEAR consists of five required core skill sessions, 21 menu sessions, and one wrap-up session. Through the use of menu sessions in six domains (i.e., sexual risk, substance use risk, health care and self-care, medication adherence, disclosure, and HIV stigma), the counselor is able to tailor the intervention to fit each client's circumstances. In the original study, the researchers found that those individuals participating in the intervention condition had an increase in the proportion of protected sexual acts for all partners (and especially HIV-negative partners) and a decrease in the number of HIV-negative partners. The intervention sample consisted primarily of members of racial/ethnic minority groups (26% African American and 42% Latino) and MSM (69% gay males).

WiLLOW.

WiLLOW19 is an intervention for HIV-positive women. The intervention uses social cognitive theory and the theory of gender and power. A health educator and an HIV-positive female peer facilitate the four, four-hour sessions. The intervention content emphasizes gender pride; benefits of maintaining current and developing new social support network members; stress management and coping strategies development; HIV/sexually transmitted disease (STD) transmission risk-reduction skills; and assertive communication and condom-use skills. The majority of the original research sample was African American (84%). Women in the intervention had lower incidence of STDs and demonstrated reduced unprotected vaginal sex and increased condom use.

METHOD FOR IDENTIFICATION OF IMPLEMENTATION BARRIERS

Agencies that receive HIV-prevention funds from CDC access a Web-based technical assistance site to request help with intervention implementation. Behavioral scientists at CDC, as well as UT Southwestern's CBAC, provide technical assistance, which is funded by CDC specifically to assist agencies implementing prevention interventions for HIV-positive people. The implementation barriers identified in this article were extracted from these technical assistance requests.

RESULTS

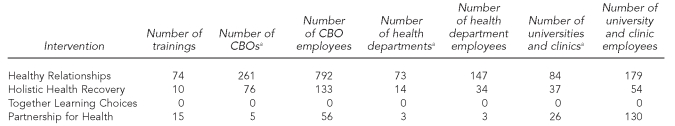

Dissemination efforts of four of the PwP interventions into prevention practice can be seen in the Table. Lessons learned through the dissemination process may be applicable to the three PwP interventions listed in the Figure that will be disseminated in the future. Unique implementation barriers have been encountered for each of these four interventions. During the period October 1, 2005, to March 31, 2009, CDC received a total of 37 requests for technical assistance around interventions for HIV-positive individuals. Of these requests for technical assistance, Healthy Relationships accounted for 29 of the 37 requests for technical assistance. Five clinics requested technical assistance around the Partnership for Health intervention. Only two requests were received around technical assistance for the Holistic Health Recovery intervention, and only one request was received for TLC.

Table.

Intervention trainings (January 1, 2003, to March 31, 2009) provided to CBOs, health departments, and others (including medical clinics)

aNote that a CBO, health department, or university/clinic may attend training on more than one intervention and thus may appear in the count for various interventions.

CBO = community-based organization

Implementation barriers for Healthy Relationships

Because four of the sessions of this intervention address skills to make healthy decisions around HIV status disclosure, sometimes providers misunderstand that the intervention's intent is status disclosure, particularly to sex partners. Training and technical assistance provision has focused on helping agencies understand that developing the decision-making skills and self-efficacy around status disclosure has a dual purpose of helping clients make better decisions about when, where, and to whom they should disclose their HIV status and also facilitating skills-building and self-efficacy around safer-sex negotiation.

Group facilitators with some mental health -background and training are recommended to deliver the intervention. One implementation challenge has been hiring mental health professionals to work in CBOs where salaries may not be competitive. Group facilitation skills appear to be essential for successful implementation of the intervention to manage group dynamics during the sessions, especially those sessions that can stir up strong emotions. Such skills also play a role in retention of clients, as poor facilitation can alienate clients and impact the intervention's efficacy.

When providing technical assistance, CDC behavioral scientists or UT Southwestern's CBAC staff began identifying those agency employees who were having problems and encouraging them to attend training on group facilitation. Further, some agencies report it is difficult to recruit an HIV-positive peer or HIV-positive mental health professional to co-lead the five intervention sessions. Some agencies have been successful in recruiting previous group participants who have successfully graduated from Healthy Relationships to be peer facilitators. Like the mental health facilitator, the peer facilitator should receive training in group facilitation. Because some agencies have limited funds to send peer facilitators to trainings, agencies may have to train these peer facilitators in-house. UT Southwestern's CBAC has made resource materials for the Healthy Relationships intervention available on its website. These materials were designed to help agencies with implementation.

A component of the intervention is the use of three- to five-minute segments of motion pictures and films to stimulate discussion. Many agencies report difficulty finding culturally appropriate film clips to use with their target population. UT Southwestern's CBAC staff is working to address this need by creating DVDs of clips for use with various populations (e.g., African American and Latino participants), which will be distributed to agencies that report challenges around clip selection. Shifting from VHS to DVD technology has helped facilitate implementation because the segments are easier to locate in DVD than they are in VHS format.Another implementation challenge is that CBOs that have not focused services on HIV-positive people may have difficulty recruiting HIV-positive individuals to the intervention. Building relationships with agencies that have a history of service to HIV-positive people is recommended. Agencies that have successfully established trust with HIV-positive clients have noted that in their experience, after the five sessions, clients wish to continue to meet. CDC behavioral scientists and UT Southwestern's CBAC staff suggest that Healthy Relationships be followed by support groups.

Implementation barriers for Holistic Health Recovery

Even though this intervention was originally implemented in methadone treatment, uptake by methadone programs has not occurred, perhaps because of the conflict of their organizational philosophy and the intervention's harm-reduction approach. CDC does not fund methadone treatment and, thus, leverage is low in encouraging the use of HIV-prevention interventions for HIV-positive injecting drug users. However, CBOs that serve drug users have adopted the intervention. Implementing agencies report three primary attractions of the intervention: (1) free implementation guidelines and slide presentations used during intervention delivery are available on the website of Yale University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, Division of Substance Abuse, Harm Reduction Unit; (2) the harm-reduction philosophy is similar to that of adopting agencies; and (3) the intervention acknowledges that spirituality is a topic that can be addressed in prevention sessions with HIV-positive individuals.

Implementation barriers for TLC

The 16 group sessions in the two modules of TLC appear to discourage agencies from implementing this intervention. Since 2004, CDC has advertised this intervention on multiple websites, yet only five agencies (the majority were urban children's hospitals) have asked to preview intervention materials. CDC included the TLC intervention in program announcements so as to convey the message that funding was available for implementation. Two themes emerged during community consultations where the intervention was discussed. The first theme is that the intervention is lengthy because the needs of HIV-positive adolescents and young adults are considerable; the intervention is described as “holistic” in that multiple needs are addressed during implementation. The second theme is that CDC would encourage adopting agencies to master one module, Acting Safe, before moving to the second module, Staying Healthy, thus breaking up the intervention into manageable segments for implementation mastery. Feedback from the health department AIDS directors has been that even with eight sessions, the Acting Safe module would be difficult to implement under real-world conditions. Only one of the 65 health department AIDS directors requested free implementation materials on the intervention.

Implementation barriers for Partnership for Health

This intervention requires a four-hour training for the entire clinic staff. Asking a clinic to close for four hours for intervention training has been difficult. Therefore, training is offered on two different days so that half of the clinic is trained at each time. Some clinicians are not convinced that brief HIV-transmission prevention counseling is effective when provided by the clinician to the HIV-positive patient.23 Medical clinics do not generally deliver behavioral prevention interventions; however, the increased efficacy of antiretroviral therapy with decreases in AIDS morbidity and mortality has changed the equation, making PwP in medical settings a higher priority. HIV-positive people are perhaps most readily accessed in medical care settings. Attitudinal and structural changes within medical practice are required to facilitate the integration of treatment and prevention. Partnership for Health encounters these barriers when being implemented.

Partnership for Health incorporates “loss- (or -consequences-) framed” prevention messaging delivered by the clinician to those with risk behavior. Clinicians have not generally been resistant to delivering loss-framed messages. During training, some clinicians commented that they speak to all patients who need to be warned about the consequences of continued risk behaviors. Other clinic staff members have shown some resistance to the loss-framed message approach, indicating that it is negative. Training and technical assistance are necessary to help clinicians understand that a loss-framed message delivered by a health-care provider may be essential to obtaining the patient's attention around the issue and to motivating the patient to engage in future protective behaviors.

Monitoring the delivery of the intervention remains a challenge because clinicians need to note in patient charts when they have provided the loss-framed message to their HIV-positive patients. Some charting forms do not allow space for this, or clinicians have concerns about the recording of possible illegal behaviors. There is no funding structure yet for Partnership for Health in HIV care clinics because CDC does not fund such clinics. Additionally, there is a definite lack of incentives that medical care providers generally receive for providing care (e.g., fee-for-service reimbursements), and there are increasingly constraints on physicians' time in medical care environments.

DISCUSSION

Barriers to implementation of the first four interventions for HIV-positive individuals diffused through the DEBI project included intervention-specific barriers that might be attributed to the intervention components and complexity, but also included agency capacity barriers that hindered implementation. To ensure maximum adoption of EBIs, those interventions that can best be implemented under real-world conditions should be selected for diffusion. Likewise, agency capacity-building activities must also be implemented so that potential adopters of the interventions possess the resources, skills, and motivation to successfully implement the interventions. The complexities of matching EBIs to agency capacity and client populations are a challenge in the dissemination of evidence-based prevention. For some HIV-positive people, a less intensive intervention will be sufficient to effect a significant change in behavior,16 whereas other HIV-positive individuals may need intensive prevention that includes support, risk-reduction strategies, and skills-building.15 HIV-positive individuals who require intensive interventions may be struggling with other psychosocial factors (e.g., mental illness or substance abuse) that affect risk behaviors. Implementing agencies should provide referrals for a range of psychosocial services.

Structural barriers may impede the implementation of prevention interventions into HIV care programs for HIV-positive people. In the U.S., prevention is the domain of public health, and treatment is provided through the medical care system. Implementing Partnership for Health requires that implementing agencies and clinics overcome this barrier through staff training and organizational change. HIV-prevention programs for HIV-positive people may also require organizational change for CBOs that wish to become more involved in a broader range of services for those who are HIV-positive. Both types of agencies will require training and technical assistance.

Adoption of the TLC15 intervention by clinics and CBOs has been disappointing. Rotheram-Borus et al. followed the TLC study with another study in which the intervention was delivered individually rather than in a group.18 Intervention content remained much the same, but because delivery was to individuals, the sessions required less time commitment. This intervention was CLEAR. CDC's Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention asked Dr. Rotheram-Borus to adapt CLEAR to the CDC Comprehensive Risk Counseling and Services guidelines to determine if adoption might be increased. At press time, CLEAR has been diffused to 10 HIV-prevention agencies so far, and adoption rates for CLEAR will be compared with those for TLC to determine if modification of the delivery strategy facilitates adoption and implementation.

Adoption of Holistic Health Recovery by methadone treatment facilities also has been disappointing. CDC does not fund methadone treatment services, and thus funding leverage is lacking to encourage evidence-based HIV prevention in these settings. Increased -dialogue and partnership between CDC and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration may facilitate adoption in the future.

Involving HIV-positive individuals in the implementation, adaptation, delivery, and evaluation of EBIs for HIV-positive people is essential for all stages of implementation, including input during the intervention selection/adoption phase, advising on client recruitment and retention strategies, providing input in the formative evaluation when the intervention is adapted for local prevention needs and agency capacity, and reflecting on evaluation findings to improve customer satisfaction and program performance. Adaptation of the EBIs to contextual influences may improve effectiveness by making the intervention most relevant to the target population, community, and implementing agency. In addition to involvement in the adoption and implementation of EBIs, HIV-positive individuals may be unique advocates for improvements in the HIV-prevention field.

Implementing agencies adapt interventions to suit client needs and agency capacity. EBIs for HIV-negative people could be adapted for HIV-positive populations.24 Agencies are encouraged to implement the EBIs as closely as possible, recognizing that adaptations will occur. Continued dialogue with CDC staff is encouraged so that interventions are not modified in a manner where fidelity is lost and, thus, intended outcomes are not expected to be achieved.

Serosorting, a strategy by which those who test positive for HIV avoid HIV-negative partners and prefer HIV-positive partners,25 has not yet been incorporated into the design of an EBI. Programs implementing EBIs may find that HIV-positive people recruited into interventions are already practicing serosorting. Outcome evaluation would require stratification of those clients that serosort from those that do not to determine the actual effects of the intervention.

Lessons learned in the dissemination of the first four PwP interventions will facilitate implementation of three new PwP EBIs currently being packaged for dissemination. These lessons will allow CDC to select efficacious interventions that have the highest potential for effectiveness in real-world settings, as well as provide insight into capacity-building strategies to facilitate successful implementation of EBIs. Risk-reduction needs of HIV-positive people vary across individuals, relationships, and time. Including HIV-positive individuals in the selection, adaptation, implementation, and evaluation of these programs increases the probability of success.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, et al. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:133–43. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson BT, Carey MP, Chaudoir SR, Reid AE. Sexual risk reduction for persons living with HIV: research synthesis of randomized controlled trials, 1993 to 2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:642–50. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000194495.15309.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Update: AIDS—United States, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(27):592–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen RS, Valdiserri RO. HIV prevention in the United States: increasing emphasis on working with those living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(Suppl 2):S119–21. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140610.82134.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Advancing HIV prevention: new strategies for a changing epidemic—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(15):329–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valleroy LA, MacKellar DA, Karon JM, Rosen DH, McFarland W, Shehan DA, et al. Young Men's Survey Study Group. HIV prevalence and associated risks in young men who have sex with men. JAMA. 2000;284:198–204. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinhardt LS, Kelly JA, Brondino MJ, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Kirshenbaum SB, Chesney MA, et al. HIV transmission risk behavior among men and women living with HIV in 4 cities in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:1057–66. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–53. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crepaz N, Marks G. Towards an understanding of sexual risk behavior in people living with HIV: a review of social, psychological, and medical findings. AIDS. 2002;16:135–49. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SY, Gibson S, Katz MH, Klausner JD, Dilley JW, Schwarcz SK, et al. Continuing increases in sexual risk behavior and sexually transmitted diseases among men who have sex with men: San Francisco, 1999–2001. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1387–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumann MS, Sogolow ED. Replicating effective programs: HIV/AIDS prevention technology transfer. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12(5 Suppl):35–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M, DiFonzo K, Simpson D, Austin J, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:84–92. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margolin A, Avants SK, Warburton LA, Hawkins KA, Shi J. A randomized clinical trial of a manual-guided risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive injection drug users. Health Psychol. 2003;22:223–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lee MB, Murphy DA, Futterman D, Duan N, Birnbaum JN, et al. Efficacy of a prevention intervention for youths living with HIV. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:400–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson JL, Milam J, McCutchan A, Stoyanoff S, Bolan R, Weiss J, et al. Effect of brief safer-sex counseling by medical providers to HIV-1 seropositive patients: a multi-clinic assessment. AIDS. 2004;18:1179–86. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200405210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, Wu E, Chang M, Hill J, et al. Long-term effects of an HIV/STI sexual risk reduction intervention for heterosexual couples. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1677-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Comulada WS, Weiss RE, Lee M, Lightfoot M. Prevention for substance-using HIV-positive young people: telephone and in-person delivery. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(Suppl 2):S68–77. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140604.57478.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Mikhail I, Lang DL, McCree DH, Davies SL, et al. A randomized controlled trial to reduce HIV transmission risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases among women living with HIV: the WiLLOW Program. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(Suppl 2):S58–67. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140603.57478.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins C, Harshbarger C, Sawyer R, Hamdallah M. The diffusion of effective behavioral interventions project: development, implementation, and lessons learned. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(4 Suppl A):5–20. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Catania JA, Kegeles SM, Coates TJ. Toward an understanding of risk behavior: an AIDS Risk Reduction Model (ARRM) Health Educ Q. 1990;17:53–72. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 1979;32:513–31. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duffus WA, Barragan M, Metsch L, Krawczyk CS, Loughlin AM, Gardner LI, et al. Effect of physician specialty on counseling practices and medical referral patterns among physicians caring for disadvantaged human immunodeficiency virus-infected populations. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1577–84. doi: 10.1086/375070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKleroy VS, Galbraith JS, Cummings B, Jones P, Harshbarger C, Collins C, et al. Adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions for new settings and target populations. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(4 Suppl A):59–73. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolitski RJ, Parsons JT, Gomez CA SUMS Study Team; SUMIT Study Team. Prevention with HIV-seropositive men who have sex with men: lessons from the Seropositive Urban Men's Study (SUMS) and the Seropositive Urban Men's Intervention Trial (SUMIT) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(Suppl 2):S101–9. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140608.36393.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]