SYNOPSIS

Objectives

Although many prisoners infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) initiate and adhere to treatment regimens while incarcerated, the benefits of in-prison therapy are frequently lost after community reentry. Little information is available on the percentage of released inmates who establish community-based HIV outpatient treatment in a timely fashion. We sought to determine the proportion of HIV-infected Texas prison inmates who enrolled in an HIV clinic within 90 days after release and to identify variables associated with timely linkage to clinical care.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of 1,750 HIV-infected inmates who were released from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) and returned to Harris County between January 2004 and December 2007. We obtained demographic and clinical data from centralized databases maintained by TDCJ and the Harris County Health District, and used logistic regression analysis to identify factors associated with linkage to post-release outpatient care.

Results

Only 20% of released inmates enrolled in an HIV clinic within 30 days of release, and only 28% did so within 90 days. Released inmates ≥30 years of age were more likely than their younger counterparts to have enrolled in care at the 30- and 90-day time points. Inmates diagnosed with schizophrenia were more likely to have initiated care within 30 days. Inmates who received antiretroviral therapy while incarcerated and those who received enhanced discharge planning were more likely to begin care at both time points.

Conclusions

A large proportion of HIV-infected inmates fail to establish outpatient care after their release from the Texas prison system. Implementation of intensive discharge planning programs may be necessary to ensure continuity of HIV care among newly released inmates.

The incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in the U.S. prison population is estimated to be more than three times that of the general population.1–3 For many HIV-infected inmates, incarceration provides opportunities for treatment, counseling, and education that were not available to them in the community.4,5 A substantial number of these individuals initiate HIV-related care for the first time during their incarceration and demonstrate high levels of adherence to their treatment regimens.6,7 Several studies have found that the provision of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the correctional setting is associated with highly positive immunologic and virologic outcomes.8,9 As an example, Springer et al. found that nearly 60% of 1,866 Connecticut prisoners who received ART had achieved an undetectable viral load by the end of their incarceration period.8

Preliminary evidence suggests that the benefits of receiving ART during incarceration are generally not sustained after release into the community. In two studies of state prisoners who received ART while incarcerated, release from prison was associated with deleterious changes in both HIV ribonucleic acid (RNA) levels and CD4 lymphocyte counts.8,9 The investigators were unable to establish whether these post-release outcomes were a result of suboptimal medication adherence vs. complete discontinuation of ART; however, a study of more than 2,000 inmates treated with ART while incarcerated found that only 30% filled an initial prescription for ART medications within 60 days of their release.10 Still, little information is available about the extent to which released inmates initiate community-based HIV-related outpatient care or the specific factors associated with successful linkage to such clinical care.11 Most of the available literature is limited primarily to descriptions of the components of continuity-of-care programs for soon-to-be-released HIV-positive inmates.12–14 To address this research deficit, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of 1,750 HIV-infected inmates released from the Texas prison system between 2004 and 2007. Our objectives were to determine the proportion of released inmates who enrolled in a community-based HIV outpatient clinic during the first 90 days after release and to identify variables associated with utilization of HIV-related care.

METHODS

Study cohort

This was a retrospective cohort study of all Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) inmates (n=1,750) with HIV infection who met the following criteria: (1) were released between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2007; (2) had previously established legal residence in Harris County, Texas; and (3) were referred to one of four HIV clinics in Harris County funded by the Ryan White CARE Act Title 1.15 The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at The University of Texas Medical Branch and Baylor College of Medicine. Because the study was confined to an analysis of retrospective electronic data, a waiver of informed consent was granted.

Medical and mental health screening

During their initial intake process, all inmates undergo medical and psychiatric assessments. This evaluation lasts approximately 60 minutes and consists of a detailed medical history and physical examination, a mental health screening, and a number of laboratory tests. All TDCJ inmates are offered serological screening for HIV infection at the time of their incarceration and before their release. Approximately 90% of the TDCJ population was screened for HIV during the study period.

HIV discharge planning

Less than 30 days before their scheduled release from prison, all HIV-infected inmates receive a minimum level of discharge planning, which includes general counseling by a prison health-care professional regarding continuity of HIV care upon reentry. Additionally, at the time of release, inmates are given a list of HIV providers in their home community, a copy of their HIV laboratory test results, and a 10-day supply of ART medication if they were receiving ART while incarcerated. Inmates who are not receiving ART at the time of release are advised to enroll in an HIV clinic as soon as possible for monitoring of their virologic and immunologic status and to access primary medical care.

A proportion of HIV-infected inmates also receive enhanced discharge planning, managed by a centralized coordinator. This program is funded by an extramural source and overseen by the director of TDCJ's HIV clinical care. In addition to the aforementioned components of minimum discharge planning, these individuals receive assistance from a chronic infectious disease nurse in completing and submitting the required consent forms for release of personal health information to HIV community clinics. Furthermore, a copy of the released inmate's medical record is sent to the referred community clinic and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) service organization. As the program was developed over the four-year study period, the percentage of inmates receiving enhanced services progressively increased (from 3% in 2004 to 50% in 2007). The distribution of demographic and clinical study variables was similar among the prisoners who received these enhanced services compared with those who did not (data not shown).

Data sources

The primary data sources for this study were the TDCJ electronic medical record (EMR) database and the Harris County Health District's Centralized Patient Care Data Management System (CPCDMS) database. The TDCJ EMR database contains demographic characteristics (gender, age, and race/ethnicity) and medical records of all TDCJ inmates. The CPCDMS database, funded by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration under the Ryan White CARE Act Title 1, holds records in a standardized format on all HIV-infected patients who received primary medical care from any Ryan White Act-funded HIV clinic in Harris County from 2000 to the present. During the study period (2004–2007), 8,640 adult patients recorded in the CPCDMS database received primary medical care at one or more of the four clinics under study.

Statistical analysis

We performed all statistical analyses using SAS® version 9.1.16 The primary dependent variable, enrollment in outpatient HIV care, was operationally defined as completion of a clinical appointment specifically for HIV medical care at any of the four aforementioned HIV clinics in Harris County. We used logistic regression analysis to examine differences between initiating HIV outpatient care at 30 days and 90 days after release from prison and to calculate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Covariates—including gender, age, race/ethnicity, calendar year of discharge, presence of a major psychiatric disorder, presence of diabetes, viral load, CD4 lymphocyte count, and parole status—were entered simultaneously in all regression models. Released inmates who were reincarcerated in the TDCJ before they had an opportunity to establish HIV outpatient care were excluded from the analyses. Specifically, two inmates who were reincarcerated within 30 days after their release were excluded from the analysis assessing enrollment in HIV care within 30 days. Likewise, 20 inmates who were reincarcerated within 90 days were excluded from the analysis assessing linkage to care within 90 days. Our exclusion of this small number of released inmates had no appreciable impact on any of the ORs in either of the multivariate models.

RESULTS

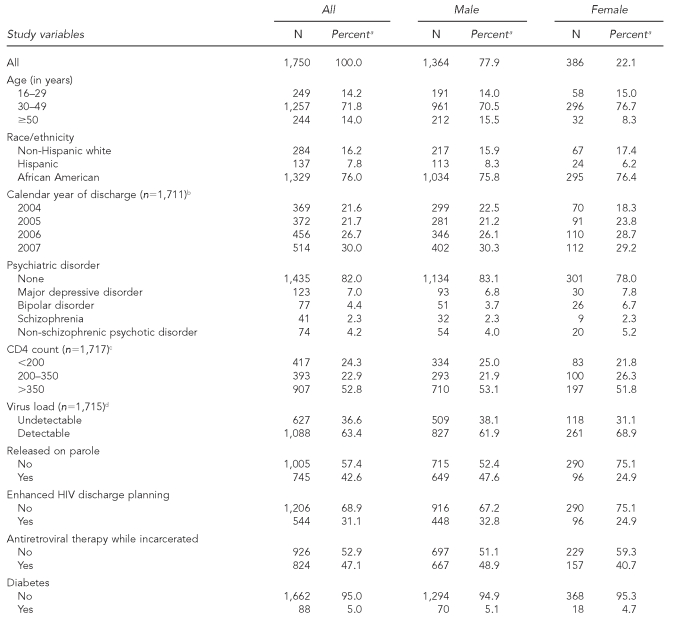

The distribution of the study population's demographic and clinical characteristics overall and stratified by gender is shown in Table 1. Of the 1,750 inmates under study, most were male (78%) and aged 30 to 49 years (72%). The race/ethnicity of the majority of the cohort was African American (76%), followed by non-Hispanic white (16%) and Hispanic (8%). In terms of clinical characteristics, 18% of the cohort had at least one major psychiatric disorder, 5% had diabetes, 53% had final CD4 lymphocyte counts of >350 lymphocytes/microliter (μL), 37% had an undetectable viral load at the time of release, and 47% were on ART while incarcerated. Overall, 43% of the inmates were released under parole supervision, and 31% received enhanced HIV discharge planning. Assessment of the distribution of each of these characteristics according to gender indicated that—with the exception of psychiatric disorders, parole status, and ART status—all study variables were distributed fairly evenly among male and female inmates.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of HIV-infected Texas prison inmates released between January 2004 and December 2007

aSome percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

bData not available for 39 inmates; percentage based on number for whom data were available

cData not available for 33 inmates; percentage based on number for whom data were available

dData not available for 35 inmates; percentage based on number for whom data were available

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

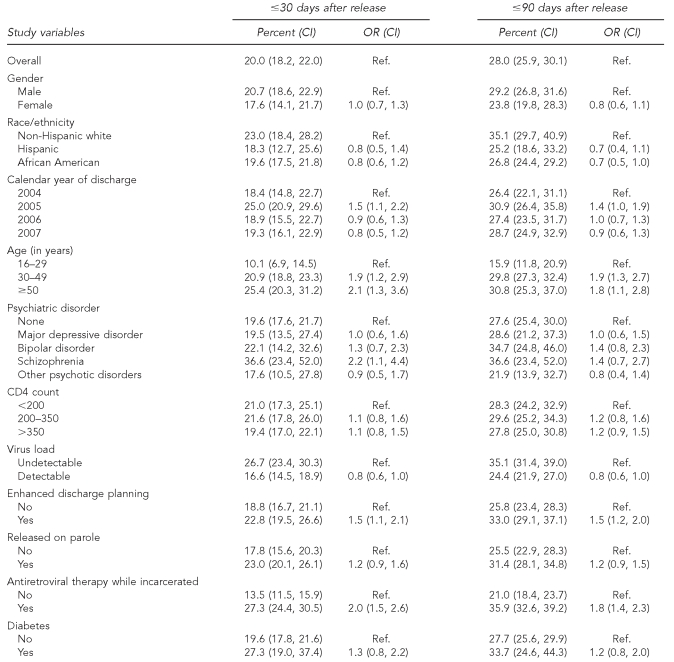

The association of demographic, clinical, and social characteristics with the initiation of HIV outpatient care at two time points (≤30 days and ≤90 days) was assessed using prevalence estimates and adjusted prevalence ORs (Table 2). Overall, 20% of released inmates initiated HIV outpatient care within 30 days, and 28% did so within 90 days. Released inmates ≥30 years of age were about twice as likely as their younger counterparts to have initiated care at the 30- and 90-day time points. Inmates with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were about twice as likely to have initiated care within 30 days as their counterparts. Inmates with a detectable viral load at the time of release were slightly less likely to have initiated care at 30 and 90 days; however, this association failed to reach statistical significance. Inmates who were on ART while incarcerated and those who received enhanced discharge planning were both more likely to have initiated HIV care at both the 30- and 90-day time points.

Table 2.

Factors associated with initiation of HIV outpatient care among HIV-infected Texas prison inmates released between January 2004 and December 2007

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

CI = confidence interval

OR = odds ratio

Ref. = Reference

DISCUSSION

In this investigation of 1,750 HIV-infected inmates released from the nation's largest prison system, we found that only 20% enrolled in outpatient care by 30 days, and only 28% did so by 90 days. Although descriptions of several programs developed to enhance linkage to medical care and other community services for recently released HIV-infected inmates have been published,12–14 our study is the first—with the exception of a small pilot study11—to examine the association between inmate characteristics and clinical factors with the likelihood of initiating HIV clinical care after release.

Recent reports indicate that while most HIV-infected prison inmates adhere to ART and have positive -treatment results during incarceration, these effects are generally not sustained when inmates are released into the general community.8,9,17 Several studies have found that a substantial proportion of released inmates who are subsequently reincarcerated exhibit higher viral loads and lower CD4 counts upon their return to prison compared with when they were released.8,9 In a retrospective study of 292 HIV-infected -prisoners who received ART during incarceration, Springer et al. reported that the mean CD4 lymphocyte count decreased by 80 lymphocytes/μL and the mean viral load increased by 1.14 log10 copies/milliliter (mL) (p<0.001) between the time of the prisoners' release and subsequent reincarceration.8 Stephenson et al. retrospectively matched 15 HIV-infected prisoners receiving ART who were released and then reincarcerated within a mean of nine months with 30 inmates receiving ART who remained incarcerated during that time period.9 At the conclusion of the study period, the median change in plasma HIV RNA level in the reincarcerated inmates was 1.29 log10 copies/mL compared with –0.03 log10 copies/mL in the group that remained incarcerated.

In an earlier study of 2,115 released inmates who received ART while in the Texas prison system, we found that only 18% of the cohort filled a prescription for ART medications within 30 days of release, and only 30% did so within 60 days of release.10 Although our previous study provided additional evidence that release from prison is associated with decreased adherence to ART regimens, it did not examine the proportion of released HIV-infected inmates—including those not receiving ART in prison—who established timely linkage with HIV-related clinical outpatient care or the specific factors associated with successful linkage to care. Our current investigation was designed to address both of these issues, which have important public health implications but have received little attention among investigators.

We found that inmates who were ≥30 years of age were twice as likely to enroll in a community-based HIV clinic at both 30 and 90 days after their release. This finding is generally consistent with studies that have shown positive associations between age and either linkage to18 or retention in19,20 HIV care. Several factors may underlie this finding. First, it is possible that the lifestyle adaptations for successful initiation of outpatient care may be more difficult for younger adults. In particular, adults younger than 30 years of age are reported to have higher rates of substance abuse than older adults, which may play a role in their failure to establish timely HIV-related care.21 Older age may also be associated with increased recognition of mortality and, therefore, greater motivation to adhere to treatment guidelines. Alternatively, better treatment adherence among older adults may be partly attributable to a survivor effect, whereby those who more thoroughly comply with HIV treatment recommendations may outlive those who are less adherent.22

Our study also showed that inmates who were on ART at the time of their release had higher rates of enrolling in post-release outpatient care at both time points. It is possible that these inmates had been in treatment longer and, as a result, were more knowledgeable about their condition. In this case, taking steps to increase patients' knowledge of their condition by providing HIV education and adherence counseling while they are incarcerated would improve the likelihood of continuity of HIV care following release from prison.

We also found that inmates with schizophrenia had a greater likelihood of enrolling in an HIV clinic within 30 days of their release; however, there was no association between this condition and enrollment at the 90-day time point. Moreover, none of the other psychiatric disorders we examined were associated with linkage to HIV care at either time point. Because optimal management of schizophrenia requires frequent follow-up care, it is possible that those inmates with this condition may have established a linkage to the medical community before their incarceration and thus had a greater likelihood of accessing HIV care shortly after their release. It is noteworthy, however, that inmates with diabetes—a condition that also requires frequent monitoring—did not exhibit a greater likelihood of enrollment in post-release care. In designing a study of 1,209 patients who presented to an HIV/AIDS clinic in Alabama, Krawczyk et al. also postulated that an existing connection to the medical community as a result of a preexisting condition would reduce delays in accessing HIV care;23 however, using bivariate analyses, the investigators found that a history of diabetes was associated with delayed access to HIV treatment. In contrast, multivariate regression analyses showed that a history of mental illness was associated with an increased likelihood of timely access to HIV care. Additional studies are needed to determine whether preexisting chronic disorders are useful, valid predictors of successful linkage to HIV care.

Notably, inmates who were released on parole were slightly more likely to enroll in HIV care at both time points, but this association did not reach statistical significance. A recent study showed that, after adjusting for potential confounders, inmates who were released on parole were more likely than those who had a standard, unsupervised release to fill an ART prescription within 30 and 60 days after release.10 Taken together, these findings suggest that the various requirements of parole (e.g., mandatory recurring visits with parole officers and participation in mental health or substance abuse treatment) may slightly improve adherence to HIV-related medical care and treatment; however, further studies are needed to determine the overall impact of parole supervision on adherence to HIV-related medical care and treatment.

The results of our study suggest that several relatively inexpensive (approximately $45,000 per year) and simple discharge-planning interventions may have a modest effect on improving linkage to health care after release from prison. We found that HIV-infected inmates who received assistance with completing consent forms for the release of personal health information to HIV community clinics and who had a copy of their medical records sent to the clinic before their first appointment were more likely to initiate HIV outpatient care, at both time points, compared with inmates who did not receive such services. Given the retrospective design of this study, however, this finding should be interpreted with some caution.

Limitations

Several potential limitations could have influenced our findings. First, it is possible that some members of the study cohort received outpatient care from a clinic not included in the CPCDMS database. However, because the majority of HIV-infected TDCJ inmates have no private or public health insurance at the time of their release from prison, and because almost all are from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds, it is highly unlikely that a significant number would have received care from a private clinic in Harris County. Additionally, all members of the study cohort were referred to one of the four Harris County-based Ryan White Act-funded clinics on the basis of their documented permanent address and at their own request after discussing referral options with the TDCJ HIV discharge planning coordinator. Because no more than 5% of former inmates released from TDCJ move from the county to which they were originally released during the first year, only a small proportion of our study cohort who sought HIV care would fail to be captured in the CPCDMS for the follow-up period.

Another potential limitation was that it was difficult to determine the extent to which underlying selection bias might have contributed to the higher rates of outpatient treatment initiation among inmates who received enhanced discharge planning. Although HIV discharge planning coordinators did not target specific clinical or demographic inmate subgroups to receive application assistance, it is possible that unmeasured behavioral characteristics may have resulted in inmates either seeking or being selected for such assistance; however, our analyses showed that all demographic and clinical characteristics were evenly distributed across the two subgroups. In particular, we observed no statistically significant differences in CD4 lymphocyte counts or viral loads across the two discharge planning subgroups. Additionally, our use of multivariate modeling permitted simultaneous adjustment for several potential confounding factors. Finally, our findings are highly dependent on accuracy of data entry into the TDCJ and CPCDMS databases. Although both TDCJ and the Harris County Health District utilize universal and standardized medical screening procedures as well as standardized and validated data entry procedures, it is possible that some patients were misclassified or that some data were entered incorrectly.

CONCLUSIONS

This investigation, which was conducted in the nation's largest state prison system,24 represents the first large-scale investigation of continuity of HIV outpatient care following release from prison. In view of the deleterious consequences of failing to maintain HIV treatment regimens,19,25 our findings highlight the importance of developing more effective post-release assistance programs to facilitate continuity of care for released inmates with HIV. Current post-release assistance programs in U.S. prison systems exhibit considerable diversity in the services they provide. More clearly identifying the specific components of effective HIV post-release assistance will require prospective investigations, particularly those that employ randomized intervention designs. Ultimately, the continued refinement and expansion of targeted post-release assistance programs will help ensure the timely continuity of HIV treatment among inmates returning to their home communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Leonard Pechacek for assistance in editing the manuscript and DeeAnn Novakosky for data management assistance.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse #R03-DA023870-02.

The research described herein was coordinated in part by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) research agreement #542-MR07. The contents of this article reflect the views of the authors and not necessarily those of the TDCJ.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maruschak LM Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. HIV in prisons, 2005. Washington: Department of Justice (US), Office of Justice Programs; 2007. NCJ Publication No. 218915. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foundation for AIDS Research. HIV in correctional settings: implications for prevention and treatment policy. Issue Brief No. 5. Washington: Foundation for AIDS Research; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) HIV/AIDS surveillance report, 2005. Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services (US); 2007. [cited 2009 Jul 2]. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2005report/default.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boutwell A, Rich JD. HIV infection behind bars. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1761–3. doi: 10.1086/421410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon PS, Flanigan TP, DeBuono BA, Laurie JJ, De Ciantis ML, Hoy J, et al. Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus in prisoners: meeting the health care challenge. Am J Med. 1993;95:629–35. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90359-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altice FL, Mostashari F, Friedland GH. Trust and the acceptance of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28:47–58. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200109010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mostashari F, Riley E, Selwyn PA, Altice FL. Acceptance and adherence with antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected women in a correctional facility. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;18:341–8. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199808010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Springer SA, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice FL. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1754–60. doi: 10.1086/421392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, Golin CE, Tien HC, Stewart P, Kaplan AH. Effect of release from prison and re-incarceration on the viral loads of HIV-infected individuals. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:84–8. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD, Wu ZH, Wells K, Pollock BH, et al. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA. 2009;301:848–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harzke AJ, Ross MW, Scott DP. Predictors of post-release primary care utilization among HIV-positive prison inmates: a pilot study. AIDS Care. 2006;18:290–301. doi: 10.1080/09540120500161892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conklin TJ, Lincoln T, Flanigan TP. A public health model to connect correctional health care with communities. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1249–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rich JD, Holmes L, Salas C, Macalino G, Davis D, Ryczek J, et al. Successful linkage of medical care and community services for HIV-positive offenders being released from prison. J Urban Health. 2001;78:279–89. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richie BE, Freudenberg N, Page J. Reintegrating women leaving jail into urban communities: a description of a model program. J Urban Health. 2001;78:290–303. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101-381, Stat. 576 (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. §§ 300ff through 300ff-121)

- 16. SAS Institute, Inc. SAS®: Version 9.1. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.;2003.

- 17.Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Chan K, Wood E, Montaner JS, Hogg RS. Initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy and continuity of HIV care: the impact of incarceration and prison release on adherence and HIV treatment outcomes. Antivir Ther. 2004;9:713–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, Loughlin AM, del Rio C, Strathdee S, et al. Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS. 2005;19:423–31. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000161772.51900.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, Jr, Suarez-Almazor ME, Rabeneck L, Hartman C, et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1493–9. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giordano TP, Visnegarwala F, White AC, Jr, Troisi CL, Frankowski RF, Hartman CM, et al. Patients referred to an urban HIV clinic frequently fail to establish care: factors predicting failure. AIDS Care. 2005;17:773–83. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331336652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White House Office of National Drug Control Policy Information Clearinghouse. Drug use trends. 2002. [cited 2009 Feb 24]. Available from: URL: http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/publications/factsht/druguse/index_3.html.

- 22.Barclay TR, Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Mason KI, Reinhard MJ, Marion SD, et al. Age-associated predictors of medication adherence in HIV-positive adults: health beliefs, self-efficacy, and neurocognitive status. Health Psychol. 2007;26:40–9. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krawczyk CS, Funkhouser E, Kilby JM, Kaslow RA, Bey AK, Vermund SH. Factors associated with delayed initiation of HIV medical care among infected persons attending a southern HIV/AIDS clinic. South Med J. 2006;99:472–81. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000215639.59563.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pew Center on the States. One in 100: behind bars in America 2008. [cited 2009 Feb 24]. Available from: URL: http://www.pewcenteronthestates.org/report_detail.aspx?id=35904.

- 25.Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) Study Group. El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, Gordin F, Abrams D, et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2283–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]