Abstract

Chemerin is a novel chemoattractant recognized by chemokine-like receptor 1 (CMKLR1), a serpentine receptor expressed primarily by plasmacytoid dendritic cells, natural killer cells, and macrophages. Human prochemerin circulates in plasma as an inactive precursor. Its chemotactic activity is expressed upon cleavage of the C-terminal amino acid residues by proteases of the coagulation, fibrinolytic, and inflammatory system. The C-terminal cleavage site of prochemerin is highly conservative, indicating that the proteolytic regulation of chemerin bioactivity is a common mechanism undertaken by different species. In this review, we summarized chemerin–proteases interactions, chemerin receptors, and their importance in normal and pathologic conditions.

Keywords: chemerin, proteolysis, chemotactic, inflammation

Introduction

Chemerin, also known as tazarotene-induced gene 2 (TIG2) or retinoic acid receptor responder 2 (RARRES2), is a potent chemoattractant for CMKLR1-expressing cells [1–4]. Chemerin circulates in blood as a prochemerin form at a concentration of ∼3 nM [5]. Platelets are a rich cellular source of chemerin which become released upon activation and may contribute to elevated blood chemerin level in some pathologic conditions [6]. Recently, it has been reported that adipocytes [7–9] and fibroblast cells [10] all produce chemerin. Chemerin is also measurable in a number of human inflammatory exudates, including ascitic fluids from human ovary cancer and liver cancer, as well as synovial fluids from arthritic patients [2]. Of note, chemerins identified from biofluids are chemotactic with a shorter C-terminal sequence compared with the full-length prochemerin. Growing evidence demonstrated that the bioactivity of chemerin is closely regulated by proteolytic cleavage in the C-terminal region to reach its maximal chemotactic or anti-inflammatory effects [5,11,12].

Chemerin is structurally distinct from CXC and CC chemokines based on primary amino acid sequences. On the other hand, it functions like a chemokine and induces leukocyte migration and intracellular calcium mobilization. In terms of the regulatory mechanism of its biological activity, chemerin is similar to a number of chemokines that undergo proteolytic processing, resulting in either a loss or gain of binding ability toward their receptors compared with the precursors. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26/DPPIV) and matrix proteinases (MMPs) have been recognized as major modulators of chemokine molecules. CD26/DPPIV is a serine-type protease that principally removes dipeptides from the N-terminal of a number of proteins. It removes the first two N-terminal amino acids from CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, three CXCR3 agonists, thereby impairing receptor signaling and inhibiting lymphocyte chemotaxis [13]. Although in most cases, CD26/DPPIV truncates chemokines and dampens their activity, it has been reported that CD26/DPPIV converts LD78beta (1–70) into LD78beta (3–70) to become a more potent monocyte chemoattractant [14]. Neutrophil granule protease MMP-9 and cathepsin G are able to cleave N-terminal sequences of some chemokines as well. In fact, MMP-9 and cathepsin G are not limited to cleave chemokine's N-terminal site because they have a broader substrate preference which enable them to cleave targets at different positions.

Carboxypeptidases modification represents a unique proteolytic regulatory mechanism for a number of effector proteins. Carboxypeptidase N (CPN) and plasma carboxypeptidase B [CPB, also named thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI)] modulate protein or peptide activity by removing the C-terminal arginine or lysine residue. They are the major inhibitors of the anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a [15,16]. Recently, we reported that the chemerin C-terminal lysine residue exposed by plasmin cleavage can be further removed by both CPN and CPB. As a result of C-terminus lysine removal, chemerin bioactivity is significantly up-regulated by this double-enzyme cleavage [6].

There is an increasing understanding that some chemokine molecules can be modified by multiple proteases, which obviously makes it difficult to evaluate the function of each chemokine both in vitro and in vivo. CXCL12, also known as stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1), belongs to the CXC chemokine family which binds to CXCR4, and probably CXCR7 as well [17]. Human SDF-1α is an 8.0 kDa protein containing 68 amino acid residues. It is strongly chemotactic for lymphocytes and plays an important role in recruiting progenitor cells from bone marrow [18,19]. Recently, SDF-1 receptor CXCR4 is found in several types of tumors, suggesting that SDF-1 may be involved in tumor metastasis [20,21]. CD26/DPPIV, elastase, MMP-9, and cathepsin G remove two, three, four, and five amino acid residues from the N-terminus of SDF-1α, respectively, and impair the above-mentioned functions [22–25]. In addition, CPN cleaves the C-terminal lysine residue of SDF-1α and dampens its functions, suggesting the importance of its C-terminal structure in binding receptors [26,27]. The purpose of this review is to summarize the recent advances in the proteolytic activation mechanism of chemerin and its potential implications in pathophysiology.

Structure of Chemerin

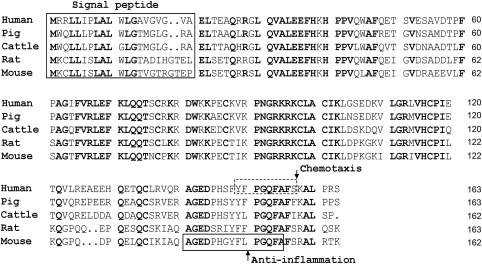

Human prochemerin is synthesized as a 163-aa protein with a 20-aa hydrophobic signal peptide which is removed by unknown proteases (Fig. 1). The secreted mature prochemerin contains 143 aa (chem21–163) with minimal chemotactic activity. Chemerin shares little homology in primary amino acid sequence with other known proteins. Instead, it has a folded structure similar to cystatins and cathelicidins [5]. The predicted structure of chemerin based on cystatins revealed a reversed orientation of chemokines, having a disordered C-terminus, a β-pleated sheet, and an N-terminal α-helix. Within the cystatin-fold domain of chemerin, there are three intra-chain disulfide bonds, whereas cystatin is stabilized by only two disulfide bridges. Primary structure of chemerin is highly conserved among different species, especially in the C-terminal region. Human chemerin shares an overall 84%, 76%, 66% and 63% amino acid sequence identity with pig, cattle, rat, and mouse chemerin, respectively (Fig. 1). Within the highly labile C-terminal domain is the sequence ‘AGEDxxxxxxPGQFAFxK(R)ALxxx' (Fig. 1). Wittamer et al. [28] found that the 9-mer peptide YFPGQFAFS derived from human chemerin is most active in chemotaxis of CMKLR1-positive cells. Recently, Cash et al. [29] demonstrated that the 15-mer peptide AGEDPHGYFLPGQFA derived from mouse chemerin possesses potent anti-inflammatory properties (Fig. 2). Chemerin also has several conservative domains in N-terminus, whether they undergo proteolytic processing to affect chemerin activity is not known.

Figure 1.

Alignment of amino acid sequences of chemerins from various species Domains of signal peptide, chemotaxis, and anti-inflammation were indicated.

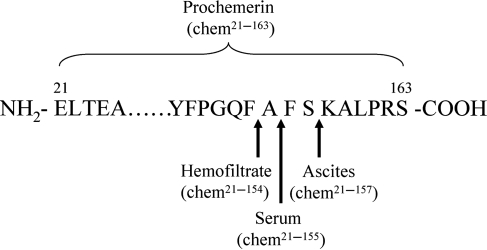

Figure 2.

Human chemerin precursor and its variants

Proteolytic Processing of Chemerin

Chemerin purified from hemofiltrate lacks nine amino acid residues in the C-terminal region, whereas serum-derived chemerin lacks only eight amino acid residues [11] and chemerin in human ovary cancer ascitic fluids lacks only six C-terminal amino acids in comparison to its precursor [2] (Fig. 2). These findings indicate that chemerin has multiple cleavage sites in the C-terminal domain. In the meantime, chemerin isoforms present in hemofiltrate, serum, or ascites have potent chemotactic activity, suggesting a proteolytic activation mechanism of chemerin bioactivity. With the discovery of chemerin variants from ascites and serum, many questions have been raised including which proteases give rise to the chemerin cleavage and which isoforms of chemerin are more bioactive. By mass spectrometry analysis, the isoforms of chemerin in hemofiltrate and ascites have been identified as chem21–154 and chem21–157, respectively; however, the proteases required for the generation of these isoforms remain to be identified. Wittamer et al. [30] reported that polymorphonuclear cells are involved in the maturation of prochemerin in vitro. Using specific protease inhibitors, serine proteases cathepsin G and elastase are identified to be responsible for prochemerin activation. Cathepsin G converts prochemerin21–163 to chem21–156 while elastase to chem21–157 [11,30]. Both chem21–156 and chem21–157 are potent chemoattractants in comparison to the precursor. In addition, Zabel et al. [11] reported that there are two other sites on prochemerin for elastase cleavage resulting in, chem21–155 and chem21–152. Furthermore, tryptase, the most abundant secretory granule-derived serine protease contained in mast cells, converts prochemerin to chem21–158 and chem21–155 [11].

The structure and activity of chemerin in serum is different from prochemerin present in normal plasma. Proteases of the coagulation cascades are investigated for their role in activating prochemerin. Zabel et al. screened a series of serine proteases from coagulation pathway for prochemerin cleavage. Factors VIIa and XIIa at 10 times higher than physiological blood zymogen levels, but not IXa, Xa, kallikrein, Xia, and thrombin, generate significant amount of activated chemerin, as determined by chemotactic activity [11]. The fibrinolytic proteases, including plasmin, urokinase plasminogen activator, and tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) which activate plasminogen to generate plasmin, are able to proteolytically activate prochemerin. Plasmin removes the last five amino acids of prochemerin and exposes lysine residue in the C-terminus (chem21–158) [11].

Carboxypeptidases CPN and CPB are able to alter target's activity by cleaving the basic C-terminal arginine or lysine residue. ProCPB (TAFI), the CPB precursor circulates in plasma at a concentration of ∼50 nM, is activated by thrombin in complex with thrombomodulin on endothelial cell surface. As a fibrinolysis inhibitor, CPB inhibits fibrin degradation by cleaving the C-terminal lysine from partially digested fibrin which prevents further incorporation of plasminogen and tPA. CPN is a constitutively active zinc metalloprotease present in plasma. CPN and CPB may play complementary roles, with the former being constitutively active and capable of regulating systemic anaphylatoxins, and the latter activated locally at sites of vascular injury to provide site-specific anti-inflammatory control. In addition to fibrin, bradykinin, complement C3a and C5a, and thrombin-cleaved osteopontin are all substrates for CPB and CPN [31]. We recently characterized that both CPB and CPN could remove the lysine residue from plasmin-cleaved chemerin. Plasmin-cleaved chemerin (chem21–158) has slightly higher chemotactic activity than prochemerin. The plasmin/CPN (or CPB) double-cleaved chemerin, chem21–157, has at least 40-fold higher bioactivity than plasmin alone-cleaved chem21–158, suggesting that the C-terminal lysine residue inhibits chemerin to fully exert its activity [6]. Using chemerin-derived C-terminal analogues in chemotaxis and receptor-binding assays toward the CMKLR1, Wittamer et al. [28] discovered that peptide YFPGQFAFS (chem149–157) retains the most activity of mature chemerin. An addition of one lysine in the C-terminal of this peptide greatly decreases the activity, whereas extension of its N-terminal sequence does not increase the activity. Another protease that has been described to mediate chem21–157 generation is staphopain B, a cysteine protease secreted by Staphylococcus aureus. Staphopain B is a potent activator of chemerin even in the presence of plasma inhibitors. Whether there are physiological cysteine proteases that play similar roles in regard of chemerin chemotactic activation is of great importance to explore [32].

Recently, neutrophil-derived serine protease proteinase 3 (PR3) is found to be a regulator of chemerin. This protease directly cleaves the precursor to become chem21–155, a less active chemerin variant [12]. Mast cell chymase, a serine protease, does not directly process prochemerin but converts active chem21–157 into the inactive chem21–154 form [12]. These results showed that neutrophils PR3 and mast cell chymase may contribute to local inactivation of chemotactic chemerin. Cash et al. [29] demonstrated that proteolytic processing of murine prochemerin by cysteine proteases such as calpains and cathepsin S results in chemerin with strong anti-inflammatory properties. Murine peptide chem140–154 exhibits most inhibitory effect on macrophage activation at picomolar concentrations. Murine peptide chem140–154 has a similar anti-inflammatory effect as proteolyzed chemerin (mchem23–154) but has reduced activity as a chemoattractant. In zymosan-induced mouse peritonitis model, mice treated with mouse chem140–154 (0.32 ng/kg) result in significantly less neutrophil and monocyte recruitment and lower pro-inflammatory mediator expression. More convincingly, chem140–154 is found not to alleviate zymosan-induced peritonitis in CMKLR1 knockout mice, demonstrating that its anti-inflammatory effects are entirely CMKLR1-dependent. In human, PR3-generated hchem21–155 (… YFPGQFA) is similar to the anti-inflammatory mchem23–154 (… FLPGQFA) in its C-terminal sequence [12]. Therefore, hchem21–155 may also have anti-inflammatory properties (Table 1).

Table 1.

Proteolytic cleavage of chemerin by proteases

| Protease | C-terminal sequence | Amino acid order | Chemotaxis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prochemerin | … YFPGQFAFSKALPRS | 21–163 | Inactive |

| Tryptase | … YFPGQFAFSK | 21–158 | Active |

| … YFPGQFA | 21–155 | ||

| Plasmin | … YFPGQFAFSK | 21–158 | Active |

| Plasmin/CPB | … YFPGQFAFS | 21–157 | Very active |

| Plasmin/CPN | … YFPGQFAFS | 21–157 | Very active |

| Staphopain B | … YFPGQFAFS | 21–157 | Very active |

| Elastase | … YFPGQFAFS | 21–157 | Active |

| … YFPGQFA | 21–155 | ||

| … YFPG | 21–152 | ||

| Cathepsin G | … YFPGQFAF | 21–156 | Active |

| PR3 | … YFPGQFA | 21–155 | Less active |

| Chymasina | … YFPGQF | 21–154 | Inactive |

| Cathepsin S | … FLPGQFA | 23–154b | Anti-inflammation |

| Calpainsc | … FLPGQFA | 23–154b | Anti-inflammation |

aCleaves chem21–157, but not chem21–163, bmouse chemerin sequence, and cspecific calpains not identified.

Taken together, the enzymatic proteolysis of chemerin precursor can generate either chemotactic chemerins or anti-inflammatory chemerins (Table 1). Serine proteases capable of producing chemotactic chemerins originate from either leukocytes or activated coagulation cascade, whereas cysteine proteases that possess anti-inflammatory effect originate from activated macrophages. Since neutrophils are typically the first cells to arrive at sites of inflammation, it is likely that generation of pro-inflammatory chemerins is in advance of anti-inflammatory chemerin production, which strongly implies that chemerin may be involved in both the initiation and resolution of inflammation.

G-protein-coupled Receptors of Chemerin

CMKLR1, also named as chemR23, is a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) expressed mainly by macrophages, natural killer cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), and myeloid dendritic cells [4,33,34]. CMKLR1 shares phylogenetic homology with some chemoattractant receptors including C5a-R, C3a-R, and formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) [5]. It is reported that eicosapentenoic acid-derived lipid known as resolvin E1 is a ligand for CMKLR1. Resolvin E1 is thought to exert anti-inflammatory effects through the activation of CMKLR1 [35]. CMKLR1 is also used as a co-receptor for immunodeficiency viruses SIV and some primary HIV-1 strains [36,37]. Independent studies from several laboratories all demonstrate that CMKLR1 is a leukocyte chemoattractant receptor for chemerin. CMKLR1 is responsible for directing the migration of dendritic cells to lymphoid organs and inflamed skin [34]. GPR1 with unknown biological function is an orphan GPCR. Recently, chemerin is identified as an endogenous ligand for GPR1. GPR1-transfected cells respond to chemerin stimulation with an elevated intracellular calcium release to a level 30% of that observed in cells expressing CMKLR1 [38]. An iodinated chemerin C-terminal fragment chem149–157 is used for radioligand-binding studies and confirms that chem149–157 binds to GPR1. The binding constant (Kd) of chem149–157 with GPR1-expressing cells is ∼5.3 nM, comparable to 4.9 nM for CMKLR1-transfected cells. With the identification of GPR1 as chemerin receptor, the new role of GPR1 other than as a co-receptor of HIV and SIV virus should be explored.

The third orphan GPCR identified as chemerin receptor is CCRL2. Zabel et al. [39] defined mouse mast cell-expressed CCRL2 as a silent chemokine receptor-like GPCRs which has a pro-inflammatory function by presenting bound attractants for signaling receptors expressed on neighboring cells [40]. CCRL2 itself does not trigger chemerin internalization or support chemerin-driven signal transduction. CCRL2 may facilitate CMKLR1 function by increasing local chemerin concentration, which is more accessible to cell-signaling receptor CMKLR1. Mast cell-expressed CCRL2 can enhance tissue swelling and leukocyte infiltration in an IgE-mediated mast cell-dependent mouse passive cutaneous anaphylaxis model, especially when low amounts of antigen-specific IgE are used.

Potential Pathophysiological Roles of Chemerin

Role in obesity and diabetes

Chemerin is a newly described adipokine with effects on adipocyte differentiation and metabolism in vitro [7–9]. Studies have shown that chemerin expression is increased during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells, murine pre-adipocytes into adipocytes. Genetic knockdown of chemerin or its receptor, CMKLR1, impairs differentiation of 3T3-L1. Expression of chemerin and CMKLR1 in mature adipocytes suggests an autocrine/paracrine mechanism. These data demonstrate that chemerin is a novel adipokine regulating adipocyte function. Incubation of 3T3-L1 cells with recombinant chemerin protein promoted insulin-stimulated glucose uptake with enhanced insulin signaling. This suggests that chemerin may play a role in insulin sensitivity and thus a potential therapeutic target for diabetes. Chemerin induces ERK1/2 phosphorylation in 3T3-L1 cells. ERK1/2 signaling is usually involved in adipogenesis and lipolysis. Gene expression of chemerin and CMKLR1 is significantly higher in adipose tissue of obese diabetes prone Psammomys obesus compared with lean and normal glycemic P. obesus. In human, plasma chemerin levels in healthy donors are not significantly different from type 2 diabetes patients. However, plasma chemerin levels in normal subjects are significantly associated with body mass index, circulating triglycerides, and blood pressure, suggesting a strong relationship of this protein with obesity-associated complications [7].

Role in psoriasis

Psoriasis is a type I interferon-driven T cell-mediated disease. It is characterized by the recruitment of pDCs into the skin. Immunohistochemistry analysis reveals that chemerin is detected in prepsoriatic skin adjacent to active lesions and early lesions, but not from chronic plaques. Neutrophils and CMKLR1-positive pDCs are also positively stained. Fibroblasts cultured from the skin of psoriatic lesions express higher levels of chemerin mRNA and protein than fibroblasts from unaffected psoriatic skin or healthy donors and promote pDC migration in vitro in a chemerin-dependent manner [10]. Skrzeczyńska-Moncznik et al. [41] reported that chemotactically active chemerin is present in lesional skin of psoriasis patients, which implicates the driven force of pDC accumulation in psoriatic skin. Therefore, chemerin/CMKLR1 axis plays an important role in psoriasis and may provide a therapeutic target for this disease.

Potential biomarker of tumors

Adrenocortical tumor (benign) is a common disease with an incidence of 4% in the US population. Using microarray analysis, chemerin is among the top five genes that have a positive correlation with tumor size. The other four genes are IL13RA2, HTR2B, CCNB2, and SLC16A [42]. Chemerin protein and transcript are also detected in skin squamous cell carcinoma (SSC). They are abundant in normal epidermis and adjacent skin to SSC lesions, but barely detectable around the keratin pearls of SCC, indicating a suppressed expression of chemerin in skin SSC [43]. In contrast, chemerin mRNA expression in mesothelioma is up-regulated compared with non-malignant mesothelial cells [44]. Taken together, chemerin may be a useful biomarker for tumor diagnostics.

Conclusions

Proteolytic processing of chemerin C-terminal domain represents a new model of protease–chemoattractant interactions. C-terminal-truncated chemerin variants display either more chemotactic or anti-inflammatory effects, which is determined by the cleavage at distinct sites by different classes of proteases. There are also interplays between proteases in modulating chemerin activities such as plasmin/CPN (or CPB) and chem21–157/chymase. Recent studies suggest that in addition to serving as a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity via chemotaxis of dendritic cells and macrophages, chemerin may also play a role in obesity, diabetes, psoriasis, and tumor biology.

Funding

This work is supported by NIH RO1 HL57530.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Derek Sim (Bayer Healthcare) for his critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Nagpal S, Patel S, Jacobe H, DiSepio D, Ghosn C, Malhotra M, Teng M, et al. Tazarotene-induced gene 2 (TIG2), a novel retinoid-responsive gene in skin. J Investig Dermatol. 1997;109:91–95. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12276660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittamer V, Franssen JD, Vulcano M, Mirjolet JF, Le Poul E, Migeotte I, Brézillon S, et al. Specific recruitment of antigen-presenting cells by chemerin, a novel processed ligand from human inflammatory fluids. J Exp Med. 2003;198:977–985. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meder W, Wendland M, Busmann A, Kutzleb C, Spodsberg N, John H, Richter R, et al. Characterization of human circulating TIG2 as a ligand for the orphan receptor ChemR23. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:495–499. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zabel BA, Silverio AM, Butcher EC. Chemokine-like receptor 1 expression and chemerin-directed chemotaxis distinguish plasmacytoid from myeloid dendritic cells in human blood. J Immunol. 2005;174:244–251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zabel BA, Zuniga L, Ohyama T, Allen SJ, Cichy J, Handel TM, Butcher EC. Chemoattractants, extracellular proteases, and the integrated host defense response. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:1021–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du XY, Zabel BA, Myles T, Allen SJ, Handel TM, Lee PP, Butcher EC, et al. Regulation of chemerin bioactivity by plasma carboxypeptidase N, carboxypeptidase B (activated thrombin-activable fibrinolysis inhibitor), and platelets. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:751–758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bozaoglu K, Bolton K, McMillan J, Zimmet P, Jowett J, Collier G, Walder K, et al. Chemerin is a novel adipokine associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4687–4694. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goralski KB, McCarthy TC, Hanniman EA, Zabel BA, Butcher EC, Parlee SD, Muruganandan S, et al. Chemerin, a novel adipokine that regulates adipogenesis and adipocyte metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28175–28188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roh SG, Song SH, Choi KC, Katoh K, Wittamer V, Parmentier M, Sasaki S. Chemerin—a new adipokine that modulates adipogenesis via its own receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:1013–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albanesi C, Scarponi C, Pallotta S, Daniele R, Bosisio D, Madonna S, Fortugno P, et al. Chemerin expression marks early psoriatic skin lesions and correlates with plasmacytoid dendritic cell recruitment. J Exp Med. 2009;206:249–258. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zabel BA, Allen SJ, Kulig P, Allen JA, Cichy J, Handel TM, Butcher EC. Chemerin activation by serine proteases of the coagulation, fibrinolytic, and inflammatory cascades. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34661–34666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guillabert A, Wittamer V, Bondue B, Godot V, Imbault V, Parmentier M, Communi D. Role of neutrophil proteinase 3 and mast cell chymase in chemerin proteolytic regulation. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:1530–1538. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0508322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Proost P, Mortier A, Loos T, Vandercappellen J, Gouwy M, Ronsse I, Schutyser E, et al. Amino-terminal truncation of CXCR3 agonists impairs receptor signaling and lymphocyte chemotaxis, while preserving antiangiogenic properties. Blood. 2001;98:3554–3561. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Proost P, Menten P, Struyf S, Schutyser E, De Meester I, Van Damme J. Cleavage by CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV converts the chemokine LD78beta into a most efficient monocyte attractant and CCR1 agonist. Blood. 2000;96:1674–1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthews KW, Mueller-Ortiz SL, Wetsel RA. Carboxypeptidase N: a pleiotropic regulator of inflammation. Mol Immunol. 2004;40:785–793. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung LL, Nishimura T, Myles T. Regulation of tissue inflammation by thrombin-activatable carboxypeptidase B (or TAFI) Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;632:61–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balabanian K, Lagane B, Infantino S, Chow KY, Harriague J, Moepps B, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, et al. The chemokine SDF-1/CXCL12 binds to and signals through the orphan receptor RDC1 in T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35760–35766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kucia M, Reca R, Miekus K, Wanzeck J, Wojakowski W, Janowska-Wieczorek A, Ratajczak J, et al. Trafficking of normal stem cells and metastasis of cancer stem cells involve similar mechanisms: pivotal role of the SDF-1-CXCR4 axis. Stem Cells. 2005;23:879–894. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broxmeyer HE. Regulation of hematopoiesis by chemokine family members. Int J Hematol. 2001;74:9–17. doi: 10.1007/BF02982544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burger JA, Peled A. CXCR4 antagonists: targeting the microenvironment in leukemia and other cancers. Leukemia. 2009;23:43–52. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zlotnik A. New insights on the role of CXCR4 in cancer metastasis. J Pathol. 2008;215:211–213. doi: 10.1002/path.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Proost P, Struyf S, Schols D, Durinx C, Wuyts A, Lenaerts JP, De Clercq E, et al. Processing by CD26/dipeptidyl-peptidase IV reduces the chemotactic and anti-HIV-1 activity of stromal-cell-derived factor-1alpha. FEBS Lett. 1998;432:73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00830-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valenzuela-Fernández A, Planchenault T, Baleux F, Staropoli I, Le-Barillec K, Leduc D, Delaunay T, et al. Leukocyte elastase negatively regulates stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 binding and functions by amino-terminal processing of SDF-1 and CXCR4. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15677–15689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111388200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McQuibban GA, Butler GS, Gong JH, Bendall L, Power C, Clark-Lewis I, Overall CM. Matrix metalloproteinase activity inactivates the CXC chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43503–43508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delgado MB, Clark-Lewis I, Loetscher P, Langen H, Thelen M, Baggiolini M, Wolf M. Rapid inactivation of stromal cell-derived factor-1 by cathepsin G associated with lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:699–707. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200103)31:3<699::aid-immu699>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis DA, Singer KE, De La Luz Sierra M, Narazaki M, Yang F, Fales HM, Yarchoan R, et al. Identification of carboxypeptidase N as an enzyme responsible for C-terminal cleavage of stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha in the circulation. Blood. 2005;105:4561–4568. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De La Luz Sierra M, Yang F, Narazaki M, Salvucci O, Davis D, Yarchoan R, Zhang HH, et al. Differential processing of stromal-derived factor-1alpha and stromal-derived factor-1beta explains functional diversity. Blood. 2004;103:2452–2459. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wittamer V, Grégoire F, Robberecht P, Vassart G, Communi D, Parmentier M. The C-terminal nonapeptide of mature chemerin activates the chemerin receptor with low nanomolar potency. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9956–9962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cash JL, Hart R, Russ A, Dixon JP, Colledge WH, Doran J, Hendrick AG, et al. Synthetic chemerin-derived peptides suppress inflammation through ChemR23. J Exp Med. 2008;205:767–775. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wittamer V, Bondue B, Guillabert A, Vassart G, Parmentier M, Communi D. Neutrophil-mediated maturation of chemerin: a link between innate and adaptive immunity. J Immunol. 2005;175:487–493. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myles T, Nishimura T, Yun TH, Nagashima M, Morser J, Patterson AJ, Pearl RG, et al. Thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor, a potential regulator of vascular inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:51059–51067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kulig P, Zabel BA, Dubin G, Allen SJ, Ohyama T, Potempa J, Handel TM, et al. Staphylococcus aureus-derived staphopain B, a potent cysteine protease activator of plasma chemerin. J Immunol. 2007;178:3713–3720. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parolini S, Santoro A, Marcenaro E, Luini W, Massardi L, Facchetti F, Communi D, et al. The role of chemerin in the colocalization of NK and dendritic cell subsets into inflamed tissues. Blood. 2007;109:3625–3632. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-038844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vermi W, Riboldi E, Wittamer V, Gentili F, Luini W, Marrelli S, Vecchi A, et al. Role of ChemR23 in directing the migration of myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells to lymphoid organs and inflamed skin. J Exp Med. 2005;201:509–515. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arita M, Bianchini F, Aliberti J, Sher A, Chiang N, Hong S, Yang R, et al. Stereochemical assignment, antiinflammatory properties, and receptor for the omega-3 lipid mediator resolvin E1. J Exp Med. 2005;201:713–722. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samson M, Edinger AL, Stordeur P, Rucker J, Verhasselt V, Sharron M, Govaerts C, et al. ChemR23, a putative chemoattractant receptor, is expressed in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and macrophages and is a coreceptor for SIV and some primary HIV-1 strains. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1689–1700. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1689::AID-IMMU1689>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martensson UE, Fenyö EM, Olde B, Owman C. Characterization of the human chemerin receptor—ChemR23/CMKLR1—as co-receptor for human and simian immunodeficiency virus infection, and identification of virus-binding receptor domains. Virology. 2006;355:6–17. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnea G, Strapps W, Herrada G, Berman Y, Ong J, Kloss B, Axel R, et al. The genetic design of signaling cascades to record receptor activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:64–69. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710487105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zabel BA, Nakae S, Zúniga L, Kim JY, Ohyama T, Alt C, Pan J, et al. Mast cell-expressed orphan receptor CCRL2 binds chemerin and is required for optimal induction of IgE-mediated passive cutaneous anaphylaxis. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2207–2220. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshimura T, Oppenheim JJ. Chemerin reveals its chimeric nature. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2187–2190. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skrzeczyńska-Moncznik J, Wawro K, Stefańska A, Oleszycka E, Kulig P, Zabel BA, Sułkowski M, et al. Potential role of chemerin in recruitment of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to diseased skin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;380:323–327. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernandez-Ranvier GG, Weng J, Yeh RF, Khanafshar E, Suh I, Barker C, Duh QY, et al. Identification of biomarkers of adrenocortical carcinoma using genomewide gene expression profiling. Arch Surg. 2008;143:841–846. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.9.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng Y, Luo S, Wang G, Peng Z, Zeng W, Tan S, Xi Y, et al. Downregulation of tazarotene induced gene-2 (TIG2) in skin squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:638–641. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mohr S, Bottin MC, Lannes B, Neuville A, Bellocq JP, Keith G, Rihn BH. Microdissection, mRNA amplification and microarray: a study of pleural mesothelial and malignant mesothelioma cells. Biochimie. 2004;86:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]