Abstract

Aim:

Pediatric lung resection is a relatively uncommon procedure that is usually performed for congenital lesions. In recent years, thoracoscopic resection has become increasingly popular, particularly for small peripheral lesions. The aim of this study was to review our experience with traditional open lung resection in order to evaluate the existing “gold standard.”

Materials and Methods:

We carried out a retrospective analysis of all children having lung resection for congenital lesions at our institution between 1997 and 2004. Data were collected from analysis of case notes, operative records and clinical consultation. The mean follow-up was 37.95 months. The data were analyzed using SPSS.

Results:

Forty-one children (13 F/28 M) underwent major lung resections during the study period. Their median age was 4.66 months (1 day–9 years). The resected lesions included 21 congenital cystic adenomatoid malformations, 14 congenital lobar emphysema, four sequestrations and one bronchogenic cyst. Fifty percent of the lesions were diagnosed antenatally. Twenty-six patients had a complete lobectomy while 15 patients had parenchymal sparing resection of the lesion alone. Mean postoperative stay was 5.7 days. There have been no complications in any of the patients. All patients are currently alive, asymptomatic and well. None of the patients have any significant chest deformity.

Conclusions:

We conclude that open lung resection enables parenchymal sparing surgery, is versatile, has few complications and produces very good long-term results. It remains the “gold standard” against which minimally invasive techniques may be judged.

Keywords: Pediatric lung resections, thoracotomy

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric lung resection is most commonly performed for congenital malformations, which include congenital cystic adenomatoid malformations (CCAMs), congenital lobar emphysema (CLE), sequestrations and bronchogenic cysts. The rate of resection has increased in recent years owing to improvements in antenatal detection, with the result that many asymptomatic lesions are being removed on the basis that they pose a future risk of infection or malignancy.[1] Traditionally, open resection and /or lobectomy has been the procedure of choice; however, a number of surgeons are now advocating the use of minimally invasive techniques on the grounds that this may lead to an improved outcome.[2] The purpose of this study was to review our experience with open resection in order to establish whether there might be a significant scope for improvement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective review. All patients with congenital lung lesions who had open resection by a single surgeon at our institution between August 1997 and November 2004 were included in the study. Patients undergoing thoracotomy for infective or malignant lesions were excluded. Data were collected from a review of case notes, operative records and patient examination. The data were analyzed using SPSS (SPSS version 12.0.1 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Forty-one patients (28 M/13 F) with a mean age of 4.7 months were included in the study. The final patient who is not on the list was a 16 year old who presented with a lung abscess. The histology of his lobectomy showed evidence of CCAM. This patient was excluded from the final analysis as this is atypical, and because we do not have definite evidence to suggest that the CCAM was the pathology behind his lung abscess at such a late age.

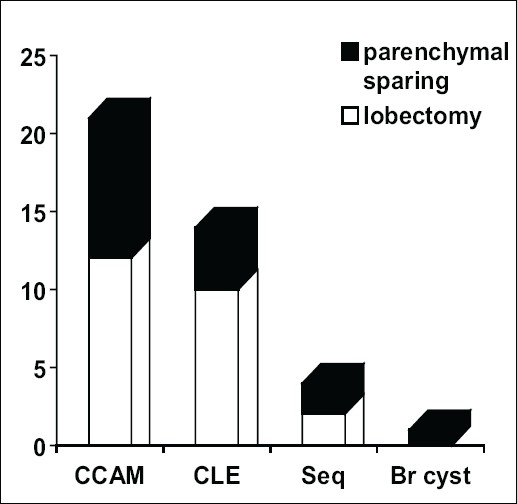

The lung lesions included 21 CCAMs (51.2%), 14 CLEs (34.1%), four sequestrations (9.8%) and one bronchogenic cyst (2.4%). Twenty-one (51.2%) of these lesions were diagnosed antenatally and 28 (70%) were symptomatic. Twenty-six (63%) lesions were removed by lobectomy and 15 (37%) by parenchymal sparing resection of the lesion alone [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Spectrum of malformations

There were no operative or perioperative complications. Blood loss was minimal and no patient required transfusion. Most infants were extubated at the end of the procedure and the mean ITU/HDU stay was 1.7 days (range 0–12 days). The mean inpatient stay was 5.7 days (range 3–13). These results are skewed by a single infant with a giant CCAM that was causing gross mediastinal shift, hydrops and extreme respiratory difficulties. An initial debulking procedure was performed to help ventilation, followed 3 days later by a definitive resection. Details of the patients in the major diagnostic groups are summarized in Tables 1 (CCAM), 2 (CLE) and 3 (intralobar sequestration).

Table 1.

Details of patients with histologically confirmed congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation

| No. | Age at surgery | Site | Preop symptom | AN diagnosis | PN diagnosis | Postop ITU days | Complications | FU (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6w | LLL | None | CCAM | CCAM | 5 | Pneumothorax + pleural effusion | 48 |

| 2 | 16w | RML | cough + dyspnoea with feeds | CCAM | CCAM | 1 | None | 32 |

| 3 | 11w | LLL | None | CCAM | CCAM | 0 | None | 19 |

| 4 | 1d | Lingula | Respiratory distress after birth | CCAM | CCAM | 0 | None | 19 |

| 5 | 3d | RLL | Respiratory distress after birth | CCAM | CCAM | 0 | None | 77 |

| 6 | 42w | LUL | Recurrent respiratory infections | None | CCAM | 1 | None | 57 |

| 7 | 12w | LUL + lingual | Cough | CCAM | CCAM | 1 | None | 42 |

| 8 | 18w | RLL | None | CCAM | CCAM | 1 | None | 35 |

| 9 | 60w | RLL | None | CCAM | CCAM | 1 | None | 23 |

| 10 | 60w | RML | Recurrent respiratory infections | CCAM | CCAM | 1 | None | 54 |

| 11 | 26w | RUL | None | Cystic lesion | CCAM | 2 | None | 67 |

| 12 | 112w | LLL | Respiratory infection | CCAM | CCAM | 1 | None | 26 |

| 13 | 100w | RLL | Respiratory infection | None | CCAM | 2 | None | 43 |

| 14 | 26w | RML | None | CCAM | CCAM | 1 | Consolidation in residual middle lobe | 50 |

| 15 | 2d | ?RLL | Respiratory distress | CCAM | CCAM | 12 | Tension hydropneumothorax | 6 |

| 16 | 60d | RLL | Respiratory distress | CCAM | CCAM | 2 | None | 49 |

| 17 | 55d | RLL | None | CCAM | CCAM | 1 | None | 36 |

| 18 | 32w | LLL | Cough | Sequestration | CCAM | 0 | None | 3 |

| 19 | 39m | RLL | None | CCAM | CCAM | 1 | None | 2 |

| 20 | 4w | RUL | Respiratory distress in newborn period | None | CCAM | 1 | None | 56 |

| 21 | 4d | RLL | None | CCAM | CCAM | 1 | None | 80 |

Table 2.

Details of patients with histologically confirmed congenital lobar emphysema

| No. | Age at surgery | Site | Preop symptom | AN diagnosis | PN diagnosis | Postop ITU days | Complications | FU (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20w | LUL | Recurrent respiratory infections | None | CLE | 0 | None | 18 |

| 2 | 68w | RUL | RUL pneumonia, respiratory failure | None | CLE | 1 | None | 32 |

| 3 | 2w | LUL | Respiratory distress after birth | None | CLE | 3 | None | 21 |

| 4 | 20w | RUL | Recurrent respiratory infections | None | CLE | 3 | None | 88 |

| 5 | 20w | LUL | Recurrent cough + dyspnoea | None | CLE | 1 | None | 66 |

| 6 | 7w | LUL | Respiratory distress after birth | None | CLE | 0 | None | 78 |

| 7 | 15w | RML | Recurrent respiratory infections | None | CLE | 5 | None | 24 |

| 8 | 60w | RLL | None | CCAM | CCAM | 0 | None | 2 |

| 9 | 8w | RUL + RML | Respiratory distress | None | CCAM | 2 | None | 80 |

| 10 | 9w | LUL | Tachypnoea at 6-week | None | CLE | 2 | None | 73 |

| 11 | 5w | LUL | Respiratory infection | None | CLE | 7 | None | 62 |

| 12 | 10w | RML | Recurrent respiratory infections | None | CLE | 3 | None | 17 |

| 13 | 20w | LUL | Recurrent respiratory infections | None | CLE | 0 | None | 22 |

| 14 | 16w | LUL | Respiratory infection | None | CLE | 0 | None | 28 |

Table 3.

Details of patients with histologically confirmed intralobar pulmonary sequestrations

| No. | Age at surgery | Site | Preop symptom | Antenatal diagnosis | Postnatal diagnosis | Postop ITU days | Complications | FU (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7y | RLL | Recurrent respiratory infections | None | Sequestration | 2 | None | 54 |

| 2 | 48w | LLL | None | CCAM | CCAM | 0 | None | 3 |

| 3 | 36w | LLL | None | CCAM | CCAM, no large vessel | 1 | None | 38 |

| 4 | 9yrs | LLL | X-ray changes persisting after resolved pneumonia | None | Sequestration | 0 | None | 11 |

Mean follow-up was for 39 months (range 2–88 months) and there were no complications. No patient had developed any chest deformity, although one child, who had two lobes resected, had a minor degree of chest asymmetry. All the patients were alive and well at the time of the study.

DISCUSSION

Lung resection is an infrequent procedure in the pediatric population. Although lung resection may be performed for infective or neoplastic lesions, the vast majority of resections are now performed for CCAMs, CLEs and sequestrations. While some of these lesions may present acutely, the majority are asymptomatic[3–5] and, traditionally, such patients would only ever have presented in the event of serious complications. In recent decades however improvements in antenatal sonography have led to a huge increase in the detection of asymptomatic lesions[1,6–9] and the exact role of surgery has become highly controversial.[10,11] In the absence of comprehensive data,[10] it is difficult to assess the relative risks of operative and nonoperative management. While it is clear that many lesions are completely innocent,[12–15] it has been suggested that others may pose a significant risk of future infection[10,16–19] or even malignancy.[20–25] At this present time, surgical strategies vary widely from the “very conservative”[6] to the “very aggressive.”[1,3,4,26] In our institution, we have adopted a pragmatic practice of removing lesions that are symptomatic, large or air filled.

In recent years, video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) has become increasingly popular in adult thoracic practice. The first recorded use of VATS in children was by Rodgers[27] in the late 1970s and, more recently, other authors have published series showing it to be a safe and effective technique in experienced hands.[2,28,29] By and large, such lung resections have either been nonanatomical resections of small peripheral lesions or complete anatomical lobectomies,[2,29] a choice of procedure that perhaps reflects the limitations of the technique. A recent small series[30] has reported the use of VATS for lung-sparing resection, and it would appear that such a technique is at least feasible, if not exactly easy.

The potential advantages of VATS are considerable, and these include better cosmesis, less discomfort, shorter hospital stay and reduced deformity.[2,30] However, these need to be balanced against the potential disadvantages, which include greater operative risk, longer operative time, increased operative cost and unnecessary loss of normal lung tissue.[2,28] In the final analysis, open thoracotomy will always be quicker, cheaper and safer in most surgeons’ hands and the potential advantage of VATS, therefore, rest upon there being a significant incidence of the problems that it claims to avoid.

We use as small a skin incision as possible followed by a muscle-sparing approach through the 5th or the 6th intercostal space, depending on the location of the lesion (i.e. upper lobe or lower lobe).We routinely use a thoracic epidural for optimal pain management and always leave a chest drain postoperatively. In our series, there were no operative, perioperative or postoperative problems. The vast majority of patients made a prompt recovery and were discharged within 6 days. There has not been a single case of scapular winging or chest deformity and in only one case is there a detectable degree of chest asymmetry. This child is quite interesting in that he had both the right middle and lower lobes resected and it seems likely that his asymmetry reflects the relative absence of underlying lung tissue. With this in mind, it would seem that the best way to avoid deformity might be to do an anatomically exact lung-sparing resection, a technique which has so far proved quite difficult with VATS.

We conclude that open resection of congenital lung lesions is a simple, safe and inexpensive technique, which produces excellent results both in the short and medium term. At the present time, we feel that this should remain the “gold standard” against which newer techniques must be judged.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Laberge JM, Puligandla P, Flageole H. Asymptomatic congenital lung malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2005;14:16–33. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothenberg SS. Experience with thoracoscopic lobectomy in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:102–4. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2003.50020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adzick NS. Management of fetal lung lesions. Clin Perinatol. 2003;30:481–92. doi: 10.1016/s0095-5108(03)00047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davenport M, Warne SA, Cacciaguerra S, Patel S, Greenough A, Nicolaides K. Current outcome of antenally diagnosed cystic lung disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:549–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes NA, Pilling DW. Bronchopulmonary foregut malformations: Embryology, radiology and quandary. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2659–73. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1812-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khakoo GA, Jawad MH, Bush A, Warner JO, Shirley IS, Buchdahl RM. Conservative management of foetal lung lesions. Early Hum Dev. 1993;35:55–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(93)90139-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallis C. Clinical outcomes of congenital lung abnormalities. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2000;1:328–35. doi: 10.1053/prrv.2000.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorpe-Beeston JG, Nicolaides KH. Cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung: Prenatal diagnosis and outcome. Prenat Diagn. 1994;14:677–88. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970140807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taguchi T, Suita S, Yamanouchi T, Nagano M, Satoh S, Koyanagi T, et al. Antenatal diagnosis and surgical management of congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1995;10:400–7. doi: 10.1159/000264265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aziz D, Langer JC, Tuuha SE, Ryan G, Ein SH, Kim PC. Perinatally diagnosed asymptomatic congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation: To resect or not? J Paediatr Surg. 2004;39:329–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Leeuwen K, Teitelbbaum DH, Hirschl RB, Austin E, Adelman SH, Polley TZ, et al. Perinatal diagnosis of congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation and its postnatal presentation, surgical indications, and natural history. J Paediatr Surg. 1999;34:794–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumez Y, Mandelbrot L, Radunovic N, Révillon Y, Dommergues M, Aubry MC, et al. Prenatal management of congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:36–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(05)80350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evrard V, Ceulemans J, Coosemans W, De Baere T, De Leyn P, Deneffe G, et al. Congenital parenchymatous malformations of the lung. World J Surg. 1999;23:1123–32. doi: 10.1007/s002689900635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacGillivray T, Harrison MR, Goldstein RB, Adzick NS. Disappearing fetal lung lesions. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:1321–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(05)80321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes MJ, Sorrells DL, Cofer BR. Spontaneous postnatal resolution of a cystic lung mass: A case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:916–8. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.32911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parikh D, Samuel M. Congenital cystic lung lesions: Is surgical resection essential? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40:533–7. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang HJ, Talbot AR, Liu KC, Chen CP, Fang HY. Infected cystic adenomatoid malformation in an adult. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:337–9. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01289-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laberge JM, Bratu I, Flageole H. The management of asymptomatic congenital lung malformations. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004;5:S305–12. doi: 10.1016/s1526-0542(04)90055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papagiannopoulos K, Hughes S, Nicholson AG, Goldstraw P. Cystic lung lesions in the pediatric and adult population: Surgical experience at the Brompton Hospital. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1594–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03469-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ueda K, Gruppo R, Unger F, Martin L, Bove K. Rhabdomyosarcoma of lung arising in congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation. Cancer. 1977;40:383–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197707)40:1<383::aid-cncr2820400154>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy JJ, Blair GK, Fraser GC, Ashmore PG, LeBlanc JG, Sett SS, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma arising within congenital pulmonary cysts: Report of three cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:1364–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(92)90299-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribet ME, Copin MC, Soots JG, Gosselin BH. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1126–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Agostino S, Bonoldi S, Dante S, Meli S, Cappellari F, Musi L. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the lung arising in cystic adenomatoid malformation: Case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1381–3. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granata C, Gambini C, Balducci T, Toma P, Michelazzi A, Conte M, et al. Bronchoalveolar carcinoma arising in congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation in a child: A case report and review of malignancies originating in congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1998;25:62–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199801)25:1<62::aid-ppul8>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozcan C, Celik A, Ural Z, Veral A, Kandiloğlu G, Balik E. Primary pulmonary rhabdomyosarcoma arising within cystic adenomatoid malformation: A case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1062–5. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.24747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azdick NS, Harrison MR, Crombleholme TM, Flake AW, Howell LJ. Fetal lung lesions-Management and outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:884–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodgers BM, Moazam F, Talbert JL. Thoracoscopy in children. Ann Surg. 1979;189:176–80. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197902000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koontz CS, Oliva V, Gow KW, Wulkan ML. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical excision of cystic lung disease in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:835–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albanese CT, Sydorak RM, Tsao KJ, Lee H. Thoracoscopic lobectomy for prenatally diagnosed lung lesions. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:553–5. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2003.50120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weatherford DA, Stephenson JE, Taylor SM, Blackhurst D. Thoracoscopy versus thoracotomy: indications and advantages. Am Surg. 1995;61:83–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]