Abstract

Pitavastatin is a potent HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor and efficient hepatocyte low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) receptor inducer, producing robust reduction of the serum LDL-C levels, even at a low dose. Pitavastatin and its lactone form are minimally metabolized by CYP enzymes, and are therefore associated with minimal drug–drug interactions (DDIs). Pitavastatin 2 to 4 mg has potent LDL-C-reducing activity, equivalent to that of atorvastatin 10 to 20 mg; several clinical trials have revealed consistently superior high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) elevating activity of pitavastatin than that of atorvastatin. Pitavastatin-induced HDL-C elevation has been shown to be sustained, even incremental, in long-term clinical trials. Pitavastatin was as well-tolerated as atorvastatin or simvastatin in double-blind randomized clinical trials. Two-year long-term safety and effectiveness of pitavastain has been confirmed in a large-scale, prospective post-marketing surveillance. The safety and efficacy profile of pitavastatin is favorable for the treatment of dyslipidemia, especially in metabolic syndrome patients. In addition to control of LDL-C, adequate control of triglyceride (TG) and HDL-C, hypertension and hyperglycemia is also necessary in metabolic syndrome patients. Pitavastatin produces adequate control of LDL-C and TG, along with potent and incremental HDL-C elevation, with a low frequency of DDIs.

Keywords: HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, pitavastatin, efficacy, safety, drug–drug interaction

Introduction

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is an established risk factor for atherosclerotic disease, especially coronary artery disease (CAD), therefore, management of serum LDL-C levels is evidently the most important goal in the treatment of dyslipidemia.1–3 Several large-scale studies on primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease (CHD) conducted using 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (statins) have reported that the LDL-C-lowering statin therapy markedly reduced the incidence of CAD.4 These results provide the rationale for wider use of statins in CHD treatment. A recent meta-analysis of 10 representative trials reported that treatment with statins for primary prevention reduced the risk of major coronary events by 30%, and that the treatment effect was noted even in clinical subgroups for which inconsistent results on efficacy have been reported, including older people, women, and patients with diabetes mellitus.5 While the statins have been proven to be definitely efficacious in CHD prevention, the percentage of patients in whom the LDL-C treatment goal recommended in the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP)-Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III in the US in 2003 is achieved by statin therapy alone is unsatisfactory: 55% in patients with diabetes mellitus, 40% in those with other CAD risk equivalents, and 62% in those with CHD.6 Similarly, the rate of achievement by risk category of the LDL-C treatment goals as reported in the 2002 report of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society guidelines in 2003, is also unsatisfactory: 51% in patients with category B3, 54% in those with B4, and 31% in those with C.7 Therefore, although strong statins such as atorvastatin, pitavastatin, and rosuvastatin are available for the treatment of dyslipidemia in routine clinical practice, use of these drugs at conventional doses may be unsatisfactory for LDL-C management in patients, including those with diabetes mellitus, other CHD risk equivalents, and CHD. For such patients, administration of statins at high doses or concomitant use of other agents for dyslipidemia should be considered. However, administration of statins at high doses may increase the risk of serious adverse drug reactions such as rhabdomyolysis. In addition, since concomitant therapy with a statin and ezemitibe has not provided sufficient evidence of the prevention of cardiovascular events, combined administration of lipid-lowering drugs has not been established for LDL-C management. From the above, combined therapy based on statins with other drugs, including those under development, is expected to be established.

Since even in patients with adequate reduction of the serum LDL-C levels, development of atherosclerotic disease, especially CAD, is not fully prevented, risk factors other than LDL-C should also be considered.8,9 For example, in the INTERHEART Study conducted on approximately 30000 patients in 52 countries, the association of various risk factors with the onset of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was determined. This study reported the 9 important risk factors of smoking, abnormal lipid balance (apolipoprotein [Apo] B/ApoA1 ratio), hypertension, diabetes, abdominal obesity, stress, decreased consumption of fruits and vegetables, alcohol intake, and decreased physical activity. Judging from the odds ratio, the impact of these risk factors were equivalent in men and women and also in all regions of the world.10 Because patients with these risk factors commonly have dyslipidemia, that is, hypertriglyceridemia and hypo-HDL cholestrolemia, management of serum triglyceride (TG) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels may also be as important as that of LDL-C for the prevention of atherosclerotic disease. Therefore, treatment of dyslipidemia requires management of the serum TG and HDL-C levels as well, as also of the complications of hypertension and diabetes, in addition to control of serum LDL-C levels, thus, combination therapy with a statin and other agents for dyslipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes should be considered. In particular, one of the recent major health issues emerging in developed countries is the metabolic syndrome, which has multiple risk factors other than LDL-C, and serves as a high risk factor for CHD. Patients with metabolic syndrome show high serum TG and low serum HDL-C levels, while the serum LDL-C levels may not be markedly elevated. Accordingly, statin monotherapy may not be efficient for comprehensive management of the lipid profile in these patients and concomitant therapy with other drugs for dyslipidemia, including fibrates and niacins, and cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitors, which are under development, may be indicated. However, since concurrent therapy with statins and fibrates has been reported to be associated with an elevated risk of occurrence of rhabdomyolysis,11 attention must be paid to drug–drug interactions when combined therapy with a statin and other drugs is considered. In addition, management of not only lipid parameters, but also of the blood pressure and glucose levels is important in patients with metabolic syndrome, and concurrent treatment of antihypertensive and antidiabetic drugs may be necessary. Nonetheless, there is little evidence regarding the efficacy of combination therapy with existing drugs for dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia and drugs under development. Results of further clinical studies on these issues are expected.

Taken together, for ideal dyslipidemia treatment, management of the serum TG, HDL-C levels and of complications such as hypertension and diabetes is also important in addition to strict LDL-C management. To achieve this goal satisfactorily, therapy based on conventional doses of statins with a minimum risk of drug interactions is required.

Pharmacological actions and mechanism of actions of pitavastatin

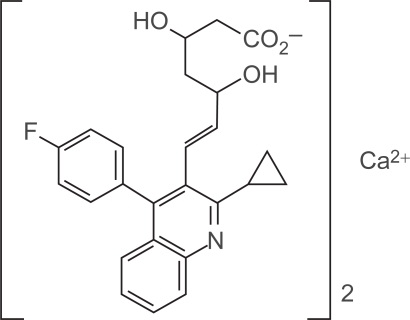

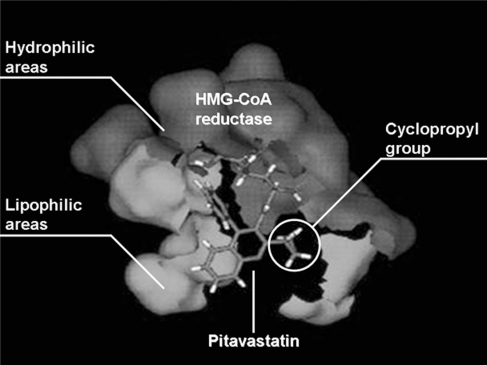

Pitavastatin has a characteristic structure, with heptenoate as the basic structure and a quinoline ring at the core. Its side chain has fluorophenyl and cyclopropyl moieties (Figure 1). Its structure provides improved pharmacokinetics, including optimal activity as a HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor and better drug absorption. Figure 2 shows simulation imaging of the binding mode with the active site (spliced out 5Å from the active center) on the reductase.12

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of pitavastatin.

Figure 2.

Binding image of pitavastatin and HMG-CoA reductase.12

In one study, the IC50 of pitavastatin for HMG-CoA reductase inhibition in rat liver microsomes was 6.8 nM, being 2.4-fold higher than that of simvastatin and 6.8-fold higher than that of pravastatin.13 Pitavastatin inhibits HMG-CoA reductase and synthesis of cholesterol in the liver like other statins, however, the IC50 for the inhibition of cholesterol synthesis from [14C] acetic acid in the cultured human hepatoma cell line HepG2 was found to be 5.8 nM, being 2.9-fold higher than that of simvastatin and 5.7-fold higher than that of atorvastatin.14 Since these results might simply indicate stronger inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase by pitavastatin, the effects of the drugs on induction of the LDL receptor was compared at the standardized concentration determined by the inhibitory action of the drugs on cholesterol synthesis. Pitavastatin showed more effective induction of LDL receptor expression than either atorvastatin or simvastatin.14 Pitavastatin induced expression of the LDL receptor more efficiently than the other statins and promoted the uptake of LDL from the blood to the liver to lower the serum LDL-C levels. The ED50 of oral pitavastatin for inhibition of sterol synthesis in the rat liver was 0.13 mg/kg, being 2.8-fold13 and 15.9-fold higher, respectively, than that of simvastatin in rats and guinea pigs. This result showed pitavastatin inhibited the secretion of VLDL, one of the TG-rich lipoproteins, from the liver.15 In addition, the effect on the secretion of ApoA1, a constituent of HDL, from the liver was evaluated using HepG2 cells. Pitavastatin was noted to have superior ApoA1 secretion-promoting effect as compared to atorvastatin and simvastatin. Pitavastatin was also found to promote ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) expression in HepG2 cells, and to possibly facilitate HDL neogenesis by ApoA1-dependent cholesterol efflux in hepatocytes.16

Pleiotropic effects of pitavastatin

Plaque rupture, the essential pathogenetic mechanism in acute coronary syndrome (ACS), is thought to be caused by structural changes, including thinning of the fibrous cap or increased lipid core, and provocation of a certain type of inflammation.17 In general, statins have multifaceted effects called pleiotropic effects in addition to their LDL-C-lowering effect.18 Table 1 shows the pleiotropic effects of pitavastatin.

Table 1.

Pleiotropic effects reported for pitavastatin

| Endothelial function | eNOS mRNA expression↑, ET-1 mRNA expression↓22 |

| Monocyte activation/endothelium-adhesion/migration | Monocyte adhesion on endothelium↓,21 MCP-1 mRNA expression↓,22 IL-8 production/mRNA expression↓,20,22 NF-κB transactivation↓,28 ICAM-1 mRNA expression↓29 |

| Foam cell formation/cholesterol accumulation | SMC proliferation↓,25,30 SMC migration↓,30 CD36 mRNA/protein expression↓,31 Cholesterol accumulation in macrophage↓, apoB48R expression↓32 |

| Plaque stabilization | Accumulation of macrophages↓, collagen↑, MMPs↓19 |

| Thrombosis formation | TF mRNA/protein expression↓,23 PAI-1 mRNA expression/antigen secretion/activity↓,22,23 t-PA mRNA expression/antigen secretion↑,23 TM mRNA expression/cellular antigen/transcription rate↑22,24 |

| Inflammatory markers | CRP↓,33 PTX3 mRNA expression↓22,26 |

| Anti-oxidation | ROS production↓,34 PON1 promoter activity↑35 |

Notes: ↑, enhance or increase; ↓, suppress or decrease

Abbreviations: eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; eT-1, endothelin 1; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; IL-8, interleukin 8; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; SMC, smooth muscle cell; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; TF, tissue factor; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; t-PA, tissue plasminogen activator; TM, thrombomodulin; CRP, C-reactive protein; PTX3, pentraxin 3; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PON1, paraoxonase 1.

After administration of pitavastatin (0.5 mg/kg/day) in drinking water to Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic (WHHL) rabbits for 16 weeks, the aortic arch of the animals was examined pathologically. Pitavastatin showed a tendency to improve the composition of vulnerable plaques, represented by increased collagen deposition and decreased macrophage infiltration (Table 2).19 Imaging analysis of the aorta revealed that the area occupied by collagen and the α-actin-positive area increased by about 66% and 92%, respectively, in the pitavastatin group; on the other hand, the macrophage-positive area was reduced by about 39%.19 Thus, pitavastatin may improve the composition of vulnerable plaques and help plaque stabilization.

Table 2.

Effect of pitavastatin on components of aortic plaque in wHHL rabits

| Plaque components | Control | Pitavastatin | Percent difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-SMA in the intima | |||

| Intimal area (mm2) | 8.47 ± 0.64 | 4.54 ± 0.62** | −46.4% |

| α-SMA positive area (mm2) | 0.68 ± 0.05 | 0.69 ± 0.08 | +1.5% |

| Percent area (%) | 8.45 ± 0.52 | 16.2 ± 0.94** | +91.7% |

| Collagen in the intima | |||

| Intimal area (mm2) | 9.54 ± 0.69 | 5.78 ± 0.88** | −39.4% |

| Collagen positive area (mm2) | 1.19 ± 0.15 | 1.28 ± 0.25 | +7.6% |

| Percent area (%) | 12.2 ± 1.2 | 20.3 ± 1.6** | +66.4% |

| Macrophage in the intima | |||

| Intimal area (mm2) | 9.13 ± 0.66 | 5.27 ± 0.79** | −42.3% |

| Macrophage positive area (mm2) | 2.95 ± 0.18 | 1.00 ± 0.16** | −66.1% |

| Percent area (%) | 33.5 ± 2.1 | 20.3 ± 2.5** | −39.4% |

Notes: N = 11. Mean ± Se.

P < 0.01 versus the control group.

Abbreviation: α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin.

Modified from Suzuki et al.19

Additionally, in vitro experiments have shown that pitavastatin has an inhibitory effect on the C-reactive-protein-induced interleukin-8 (IL-8) production by endothelial cells, and also on monocyte adhesion to the endothelial cells, via monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) stimulation,20,21 confirming the anti-inflammatory effects of the drug. Moreover, pitavastatin is reported to have an inhibitory effect on plasminogen activator inihibitor-1 (PAI-1)22,23 and tissue factor (TF)23 which are important factors in thrombosis formation, and to induce tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA)23 and thrombomodulin (TM) expression.22,24 Therefore, pitavastatin is expected to exert its anti-atherosclerotic effect via various mechanisms.

These pleiotropic effects of pitavastatin were compared with those of other statins using the inhibitory effects on the proliferation of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) derived from the human coronary arteries as an indicator. Even at low concentrations, pitavastatin was found to inhibit the proliferation of SMCs derived from human coronary arteries more strongly than atorvastatin, simvastatin, fluvastatin, rosuvastatin, or pravastatin.25

To evaluate a new effect of pitavastatin on the blood vessels, the changes in the gene expression profiles brought about by statins were investigated in cultured normal human umbilical vein endothelial cells and normal human coronary artery SMCs by DNA microarray analysis. Pitavastatin inhibited the expression of pentraxin 3 (PTX3) related to acute inflammation.26 PTX3 is found to be elevated especially in arterial inflammation in patients with unstable angina pectoris, and increased expression of PTX3 has attracted attention as a new effect of pitavastatin.27

Pharmacokinetics of pitavastatin

Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion

In pharmacokinetic studies, pitavastatin has been demonstrated to show a high bioavailablity of 80% in rats and 88% in canines after administration at the dose of 1 mg/kg. It is distributed selectively to the target organ, the liver, and pharmacokinetic studies in rats conducted using 14C-pitavastatin have confirmed approximately 54 times higher radioactivity in the liver than that in the serum.36

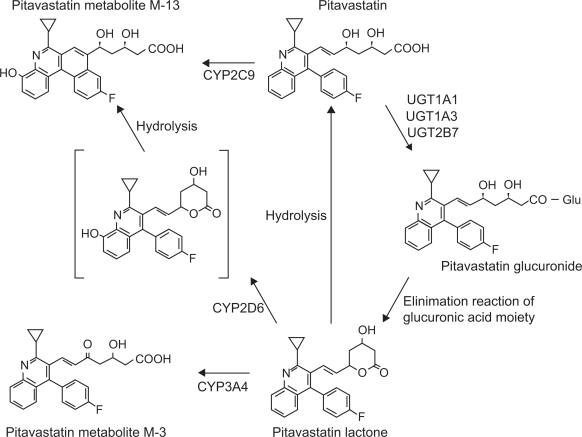

Figure 3 shows the metabolic pathway of pitavastatin. Many lipophillic drugs are metabolized in the liver by the drug-metabolizing enzyme, cytochrome P450 (CYP).37,38 Statins are also metabolized by CYPs, for example, lipophilic statins such as simvastatin and atorvastatin are metabolized by CYP3A4, and fluvastatin by CYP2C9.39 Pitavastatin is lipophilic, but is scarcely metabolized by CYPs. It is rapidly glucuronized by uridine diphosphate-glucuronyltransferase (UGT) 1A1, UGT1A3, and UGT2B7, and is then converted to pitavastatin lactone, an inactive form, by elimination reaction of the glucuronic acid.37 Pitavastatin is minimally metabolized by CYP2C9 to the M-13 form,40 which is not detected clinically.41 The CYP metabolic properties of pitavastatin are similar to those of the hydrophilic pravastatin and rosuvastatin, and pitavastatin is classified into a non-CYP metabolizable type (Table 3).39 All statins but pitavastatin are metabolized by CYP3A4 after being transformed to the lactone form through glucuronidation, however, pitavastatin lactone is not metabolized by CYPs.38

Figure 3.

Metabolic pathway of pitavastatin. Adapted with permission from Fujino H, Yamada I, Shimada S, et al. Metabolic fate of pitavastatin, a new inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase: human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes involved in lactonization. Xenobiotica. 2003;33(1):27–41;37 Fujino H, Saito T, Tsunenari Y, et al. Metabolic properties of the acid and lactone forms of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Xenobiotica. 2004;34(11–12):961–971.38 Copyright © 2003, 2004 Taylor & Francis.

Abbreviation: Glu-, monoglucuronic acid conjugate.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of statins

| Statin | Pitavastatin | Atorvastatin | Fluvastatin | Lovastatin | Pravastatin | Rosuvastatin | Simvastatin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight | 881 | 1209 | 433.5 | 405 | 446.5 | 1001 | 418.15 |

| Origin | Synthetic | Synthetic | Synthetic | Microbial | Semi-synthetic (microbial origin) | Synthetic | Semi-synthetic (microbial origin) |

| Racemic | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Prodrug | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Log P | 1.49 | 1.11 | 1.27 | 1.70 | −0.84 | −0.33 | 1.60 |

| Absorption (%) | 80 | 30 | 98 | 31 | 37 | 50 | 65–85 |

| Hepatic excretion (%) | NA | >70 | 68 | >70 | 66 | 90 | 78–87 |

| Bioavailability (%) | >60 | 12 | 10–35 | <5 | 17 | 20 | <5 |

| Effect of food on bioavailability (%) | No | Yes (↓13) | Yes (↓15–25) | Yes (↑50) | Yes (↓30) | No | No |

| Protein binding (%) | 96 | >98 | >98 | 96–98.5 | 43–54 | 88 | >95 |

| Tmax | 0.5–0.8 | 2.0–4.0 | 0.5–1.5 | 2.8 | 0.9–1.6 | 3 | 1.3–2.4 |

| T1/2 | 11 | 11–30 | 0.5–2.3 | 2.5–3.0 | 0.8–3.0 | 20 | 1.9–3.0 |

| Renal excretion | <2 | 2 | 6 | 30 | 60 | 10 | 13 |

| 50% inhibitory concentration (nmol/L) | 6.8 | 15.2 | 17.9 | 2.7–11.1 | 55.1 | 12 | 18.1 |

| Lipid-lowering Metabolites | No | Yes, active | Yes, mainly inactive | Yes | Yes, mainly inactive | No | Yes |

| Range of dose (mg) | 1–4 | 10–80 | 20–80 | 10–80 | 5–40 | 5–80 | 5–80 |

| CYP isoforms primarily involving with metabolic pathway | CYP2C9 Minimally | CYP3A4 | CYP2C9 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 Minimally | CYP2C9 Minimally | CYP3A4 |

Notes: Log P, logarithm of base 10 of the n-octanol/water partition coefficient of active hydroxy forms of statins.

Abbreviation: CYP, cytochrome P450.

Modified from Fujino et al.37

To evaluate the effects of grapefruit juice (GFJ), a CYP3A4 inhibitor, on the pharmacokinetics of pitavastatin and atorvastatin, 8 healthy adults were administered either GFJ or water 3 times daily for 4 days, followed by a single dose of 4 mg pitavastatin or 20 mg atorvastatin. GFJ increased the area under the curve (AUC) 0–24 of atorvastatin by 83% (95% confidence interval [CI] 23% to 144%) and that of pitavastatin by only 13% (–3% to 29%).42 Pitavastatin appears to be scarcely affected by CYP3A4-mediated drug–drug interaction.

The in vitro inhibitory effects of each type of statin on CYP metabolism were evaluated using model substrates. Simvastatin, simvastatin acid, and atorvastatin lactone inhibited CYP metabolism of the model substrates, while pitavastatin scarcely inhibited it.43 This result suggests that pitavastatin is scarcely involved in drug–drug interactions mediated by CYPs.

As for the distribution of pitavastatin, it is reported to be taken up into the liver through organic anion transporter protein 2 (OATP2),44 and the AUC0–24 of pitavastatin was increased by 4.6-fold by concurrent administration of cyclosporine, an OATP2 inhibitor.45 Other statins are also reported to be taken up into the liver, mainly by OATP2, and combined therapy with cyclosporine increases their plasma concentrations.46 On the other hand, multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1), a P glycoprotein, is not involved in pitavastatin pharmacokinetics.47

Combined therapy may cause an increase in the blood concentration of either drug to increase the incidence of adverse drug reactions and enhance the effects. Pitavastatin is non-CYP metabolizable and rarely causes drug–drug interactions through CYP isoforms. Therefore, pitavastatin is expected to be easily applied for the treatment of patients with metabolic syndrome, which may require multidrug therapy, including drugs for dyslipidemia, hypertension and diabetes.

Pharmacokinetic study in patients with liver dysfunction

After administration of a single 2 mg dose pitavastatin, the plasma concentrations of 12 male patients with liver cirrhosis (6 patients with Child–Pugh grade A, 6 with Child–Pugh grade B disease) were compared with those of 6 healthy male volunteers without liver disease. 1.19-and 2.47-fold increase of the Cmax, and 1.27-and 3.64-fold increase of the AUCt were observed in patients with Child–Pugh grade A and Child–Pugh grade B, respectively, as compared with the values in healthy adults without liver disease.48

Pharmacokinetic study in the elderly

The pharmacokinetics of plasma pitavastatin and pitavastatin lactone were compared between 6 elderly subjects aged 65 to 71 years and 5 non-elderly subjects aged 22 to 24 years who received repeated oral administration of pitavastatin 2 mg for 5 days. Pharmacokinetic parameters of pitavastatin and pitavastatin lactone did not significantly differ between the elderly and the non-elderly. Aging is considered to cause little change in the pharmacokinetics of pitavastatin.49

Studies on efficacy

Studies of the LDL-C-lowering effect of pitavastatin

The LDL-C-lowering effect of statins increases in a dose-dependent manner, and the safety risk increases with dose escalation.50 Therefore, the LDL-C-lowering effect at the initial dose is important, and the statins are classified into strong statins, which have a strong LDL-C-lowering action at the initial doses, including atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, and others.51 Pitavastatin belongs to the category of strong statins due to the similar LDL-C-lowering action of this drug to that of atorvastatin at the initial dose.

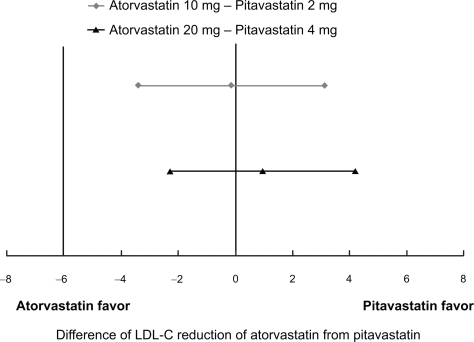

In a dose-finding study in patients with hypercholesterolemia conducted in Japan, where pitavastatin was first developed, the LDL-C-lowering effect of pitavastatin after 12-week administration was 34% (n = 81) at the dose of 1 mg, 42% (n = 75) at the dose of 2 mg, and 47% (n = 76) at the dose of 4 mg.52 In a Phase III study, the effect of 12-week treatment with pitavastatin 2 mg was compared with that of pravastatin 10 mg. The mean percent reduction in LDL-C following pitavastatin treatment was 38% (n = 120) and that following pravastatin treatment was 18% (n = 105).53 LDL-C reduction by pitavastatin 4 mg was observed by 46% (n = 25) after 8-week administration in another Phase II study similar to the dose finding study.54 Almost similar results were obtained in the development studies conducted in Korea and Europe. In a Phase III study conducted in Korea, mean percent reduction in LDL-C after 8-week administration of pitavastatin 2 mg (n = 49) was 38%, similar to that in the control simvastatin 20 mg group (n = 46).55 In a Phase III study conducted in Europe, mean percent reduction in LDL-C following 12-week administration of pitavastatin 2 mg (n = 315) and 4 mg (n = 298) were 38% and 45%, respectively, being comparable to that observed following administration of the control drug atorvastatin at 10 mg (n = 102) and 20 mg (n = 102) (Figure 4).56 In another Phase III study in Europe compared pitavastatin and simvastatin with the same design, pitavastatin 2 mg demonstrated significantly superior reduction in LDL-C by 39% (n = 307) to that of simvastatin 20 mg by 35% (n = 107) (p = 0.014) while pitavastatin 4 mg and simvastatin 40 mg demonstrated similar reduction in LDL-C by 44% (n = 319) and 43% (n = 110), respectively.57

Figure 4.

95% confidence interval on treatment difference in adjusted mean percentage change in LDL-C observed in phase III double-blind clinical trial of pitavastatin vs atorvastatin.56

Note: Non-inferiority margin of LDL-C reduction by pitavastatin to that by atorvastatin was set to −6%.

The efficacy of pitavastatin was evaluated in 30 heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia patients. Decrease of the serum LDL-C levels by 40% was observed after 8-week administration of pitavastatin 2 mg, and by 48% after another 8-week administration at the dose of 4 mg.58

From the above-mentioned clinical results on the LDL-C-lowering efficacy of statins, the LDL-C-lowering action of pitavastatin at doses of 2 to 4 mg was as strong as that of atorvastatin at doses of 10 to 20 mg; also, pitavastatin 2 mg was efficacious equivalent or more than simvastatin 20 mg.

Studies of the efficacy of pitavastatin on lipid parameters other than LDL-C

Since even in patients with sufficiently reduced serum LDL-C levels, development of atherosclerotic disease, especially CHD, is not fully prevented, other risk factors than LDL-C also should be considered. The clinical effects of pitavastatin on various lipid parameters other than LDL-C have been reported. In particular, pitavastatin has been demonstrated to show superior HDL-C-elevating effect as compared to atorvastatin.

In a Phase III study conducted in Japan, administration of pitavastatin 2 mg produced a statistically significant increase of the serum HDL-C level by 8.9%.54 In a Phase III study conducted in Europe, significant increases of the serum HDL-C level by 4.0% and 5.0% were observed following administration of pitavastatin at the doses of 2 mg and 4 mg, respectively. In the same study, increases of the serum HDL-C level by 3.0% and 2.5% were observed following administration of atorvastatin at the doses of 10 mg and 20 mg, respectively, there being no significant difference in effect from that of pitavastatin.56

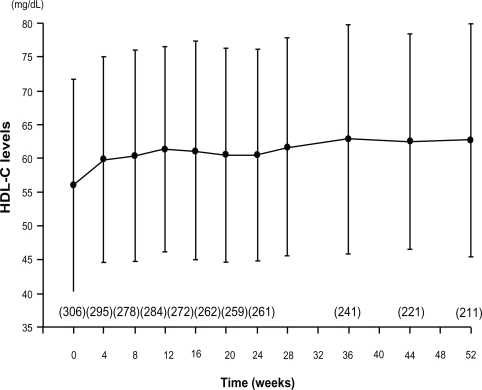

The HDL-C-elevating effect of some statins has been reported to diminish with long-term treatment.59 A phase III long-term administration study of pitavastatin 1 to 4 mg for 52 weeks was conducted in 317 patients. The serum HDL-C level, which was 56.0 ± 15.7 mg/dL at the baseline, showed significant and sustained increase from 4 weeks of treatment, to rise by 6.0 mg/dL after 52 weeks (Figure 5).60 A total of 43 hypercholesterolemic patients with low serum HDL-C levels were examined to determine the effect of pitavastatin on the serum HDL-C levels. Administration of pitavastatin produced a significant and sustained increase of the serum HDL-C levels (from 36.0 ± 5.9 mg/dL at baseline to 40.5 ± 9.1 mg/dL at 12 months, P < 0.001) and Apo A-I levels (from 108.4 ± 18.0 mg/dL to 118.7 ± 19.3 mg/dL, P < 0.01).61 In a clinical study conducted to confirm the effect of pitavastatin on the HDL metabolism,30 29 patients with hypercholesterolemia were treated with pitavastatin 2 mg for 4 weeks. In this study, pitavastatin administration produced a decrease of the serum total cholesterol by 26.9% and of the serum LDL-C levels by 39.8%, with increase of the serum HDL-C and HDL2-C levels by 6.0% and 9.0%, respectively. On the other hand, there was no change of the serum HDL3-C level and significant decrease of the serum preβ1-HDL level.62 In a randomized study comparing the HDL-C-elevating effect of pitavastatin 2 mg with that of atorvastatin 10 mg for 52 weeks, pitavastatin (n = 88) was significantly superior to atorvastatin (n = 85) in increasing the serum HDL-C levels (8.2% vs 2.9%, P = 0.031). The percent change in the serum Apo A-1 level in the pitavastatin group was significantly higher (5.1%) than that in the atorvastatin group (0.6%) (P = 0.019).63 In a comparative study of pitavastatin and atorvastatin in Japanese hypercholesterolemic patients (Collaborative Study on Hypercholesterolemia Drug Intervention and Their Benefits for Atherosclerosis Prevention [CHIBA study]), the efficacy of pitavastatin 2 mg on the serum non-HDL-C levels was compared with that of atorvastatin 10 mg after 12-week treatment. The results revealed similar reduction of the serum non-HDL-C levels with pitavastatin treatment (39.0%, n = 93) and atorvastatin treatment (40.3%, n = 98), but a significant increase of the serum HDL-C levels only with pitavastatin treatment. In the CHIBA study, the waist circumference, body weight, and body mass index (BMI) were correlated with the percent reduction of the serum non-HDL-C only in the atorvastatin group. Improvement of the lipid parameters in the subgroup of patients with metabolic syndrome was more favorable in the pitavastatin group (n = 28) than in the atorvastatin group (n = 25). The pitavastatin group showed a significant increase of the serum HDL-C levels and decrease of the serum TG levels.64

Figure 5.

Time course of mean HDL-C over 52 weeks in a long-term study of pitavastatin.60

Note: Parentheses, number of patients.

As for the TG-lowering effect of pitavastatin in patients with pretreatment TG levels of 150 mg/dL or more, in a phase III study, pitavastatin 2 mg administration for 12 weeks (n = 50) produced a significant decrease of the serum TG levels by 23%, and in a phase II study, treatment with 4 mg of the drug for 8 weeks (n = 25) produced a significant decrease of the serum TG levels by 42%.52,54 In a double-blind placebo controlled cross-over study, pitavastatin 2 mg produced a significant decrease of the serum TG levels by 20% compared with placebo.65

The effects of pitavastatin on the serum levels of other atherogenic lipoproteins, including remnant-like particle cholesterol (RLP-C) and small, dense LDL, have also been investigated. A total of 34 hypercholesterolemic patients with type 2 diabetes were treated with pitavastatin 2 mg for 8 weeks. With the treatment, significant decrease of the serum RLP-C levels and the proportion of small, dense LDL, and significant increase of the peak particle diameter, an indicator of the LDL particle size, were observed.66 In the Kansai Investigation of Statin for Hyperlipidemic Intervention in Metabolism and Endocrinology (KISHIMEN), pitavastatin at the dose of 1 or 2 mg was administered to 178 patients with hypercholesterolemia for 6 to 12 months. Significant decreases of the serum LDL-C and RLP-C levels by 30.3% (n = 139) and 22.8% (n = 47), respectively, were observed. Serum TG levels decreased by 15.9% in 64 patients with basal TG levels of 150 mg/dL or more, and the serum HDL-C levels significantly increased.67 The effects of pitavastatin 2 mg on the serum RLP-C and small, dense LDL-cholesterol levels were compared with those of atorvastatin 10 mg in heterozygous patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. A total of 17 heterozygous patients with familial hypercholesterolemia received pitavastatin 2 mg or atorvastatin 10 mg. After 12 weeks, the serum levels of RLP-C and small, dense LDL-C were significantly reduced in both groups, with no differences noted between the groups.68

From the above clinical results on the effects of pitavastatin on lipid parameters other than LDL-C, pitavastatin exhibits TG-reducing and HDL-C-elevating effects, and the HDL-C elevating effect of pitavastatin is superior to that of atorvastatin. Pitavastatin also improves other atherogenic lipid parameters, including non-HDL-C, small, dense LDL, and RLP-C, as efficiently as atorvastatin. These comprehensive effects of pitavastatin on the lipid profile is expected to exert favorable effects on abnormal atherogenic lipoproteins and dysfunction of anti-atherosclerotic lipoproteins, which are typically noted in patients with metabolic syndrome, who need sufficient LDL-C-lowering treatment for reducing the risk of CHD, and frequently have hypertriglyceridemia and hypo-HDL-cholesterolemia.

Studies of the efficacy of pitavastatin on factors other than the lipid parameters

Since pitavastatin 2 to 4 mg has been demonstrated to show potent LDL-C reducing effects equivalent to atorvastatin 10 to 20 mg, it was expected that this drug would also reduce the risk of cardiovascular events, like atorvastatin. Several clinical studies have consistently demonstrated the efficacy of pitavastatin on plaques in the coronary arteries and in the carotid arteries while the usefulness of this effect as a surrogate marker is controversial.

Eighty-two patients matched for age and gender from among 870 patients undergoing intravascular ultrasound (IVUS)-guided percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were retrospectively assigned to either lipid-lowering therapy (n = 41, pitavastatin 2 mg) or a control group (n = 41, diet only). Significant reduction of the plaque volume index (PVI) was observed in the pitavastatin group (10.6% ± 9.4% decrease) as compared with that in the control group (8.1% ± 14.0% increase, P < 0.001). There were significant correlations between the percent change in the PVI and the follow-up serum LDL-C levels (r = 0.500, P < 0.001) and percent change of the serum LDL-C levels (r = 0.479, P < 0.001).69 A prospective study to determine the effects on carotid plaques was conducted in patients treated with pitavastatin 4 mg (n = 33) or placebo (n = 32) within 3 days of onset of the acute coronary syndrome (ACS). In the pitavastatin group, greater improvement of the vulnerable carotid plaques at 1 month, as analyzed by carotid ultrasound integrated backscatter (IBS), was observed in the pitavastatin group as compared with that in the placebo group. Significantly greater improvement of the levels of inflammatory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), vascular endotherial growth factor (VEGF), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), at 1 month was observed in the pitavastatin group as compared with that in the placebo group.70 To evaluate the effect on coronary plaques prospectively, the Japan Assessment of Pitavastatin and Atorvastatin in Acute Coronary Syndrome (JAPAN-ACS) Study was conducted in 252 patients with ACS who underwent IVUS-guided PCI. The effects of 8-month treatment with pitavastatin 4 mg and atorvastatin 20 mg were compared. The mean percent change in the plaque volume (PV) was −16.9% ± 13.9% in the pitavastain group and −18.1% ± 14.2% in the atorvastatin group, indicating a significant decrease in both groups. Administration of pitavastatin in patients with ACS is thus supposed to cause regression of coronary plaques (Table 4).71 A similar study using pravastatin as control is ongoing.72

Table 4.

Percent changes of parameters for coronary plaque observed in JAPAN-ACS study

| Both groups (n = 252) | Pvalue compared with baseline | Pitavastatin (n = 125) | Pvalue compared with baseline | Atorvastatin (n = 127) | Pvalue compared with baseline | Pvalue between groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque volume (mm3) | −17.5 ± 14.0 | <0.001 | −16.9 ± 13.9 | <0.001 | −18.1 ± 14.2 | <0.001 | 0.5 |

| Vessel volume (mm3) | −6.0 ± 11.4 | <0.001 | −5.9 ± 11.8 | <0.001 | −6.2 ± 11.1 | <0.001 | 0.8 |

| Lumen volume (mm3) | 6.5 ± 20.4 | <0.001 | 6.4 ± 21.5 | 0.0012 | 6.6 ± 19.4 | <0.001 | 0.9 |

Adapted with permission from Hiro T, Kimura T, Morimoto T, et al. Effect of intensive statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a multi-center randomized trial evaluated by volumetric intravascular ultrasound using pitavastatin versus atorvastatin (JAPAN-ACS Study). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:293–302.71 Copyright © 2009 Elsevier.

In addition, administration of pitavastatin has been reported to induce a decrease in the serum level of high-sensitivity CRP associated with atherosclerosis, and increase in the serum level of adiponectin.67,73 The short-and intermediate-term effects of pitavastatin and atorvastatin on the endothelial functions have been evaluated. The short-term effects of pitavastatin on the endothelial functions were superior to those of atorvastatin.74 Moreover, beneficial effects of pitavastatin on the cardiac and renal functions, as well as on bone metabolism, have been reported.75–77 A clinical study is ongoing to evaluate the effect of pitavastatin for prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus.78

Safety and tolerability

According to the clinical findings obtained to date, the safety of pitavastatin at the initial dose is equivalent to that of the statins already on the market, and the tolerability at the initial dose is equivalent to that of atorvastatin. Pitavastatin is supposed to rarely cause adverse drug reactions (ADRs) related to glucose metabolism and the kidneys, notable new ADRs of strong statins.

Integrated safety analysis of clinical studies

In the clinical studies conducted in Japan prior to the drug approval, ADRs, as defined by signs and symptoms, occurred in 50 (5.6%) out of 886 patients. ADRs, as defined by laboratory abnormalities, occurred in 167 patients (18.8%), and included increase of the serum γ-glutamyl-transferase (GTP), creatine phosphokinase (CK [CPK]), serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT [glutamic pyruvic transaminase, GPT]), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST [glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, GOT]) values, not specific to pitavastatin, and their frequency and severity were similar to those noted for the existing statins.51 The incidence of ADRs by the dose of pitavastatin, as defined by signs, symptoms and laboratory abnormalities, for each dose was 20.3% (26/128 patients) for 1 mg, 23.3% (121/519) for 2 mg, and 20.9% (50/239) for 4 mg, demonstrating the absence of a dose relationship. There was no increase in the incidence or severity of ADRs due to long-term administration, and no development of new ADRs.79

Comparative studies with other statins

In the Phase III double-blind comparative studies conducted in Japan, Korea and Europe, the safety profile of pitavastatin 2 mg was similar to that of pravastatin 10 mg, simvastatin 20 mg, and atorvastatin 10 mg. Thus, the safety of pitavastatin at the initial dose is considered to be equivalent to that of the other existing statins. Pitavastatin showed similar tolerability to atorvastatin 10 mg, and the safety of pitavastatin at an initial dose appeared to be same as that of atorvastatin.53,55,56

ADRs due to high-dose statins are reported to be associated with a decrease in coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10). An open, randomized, cross-over study using pitavastatin 4 mg and atorvastatin 20 mg was conducted to compare their efficacy, safety, and effect to decrease the CoQ10 levels at an increased dose of them in 19 Japanese patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Plasma levels of CoQ10 were reduced by atorvastatin (–26.1%, P = 0.0007), but not by pitavastatin (–7.7%, P = 0.39).80

Effects on glucose metabolism

Several studies have reported deterioration of the glucose metabolism following administration of statins.81–84 The effects of pitavastatin on glucose metabolism have been reported by several clinical studies.

Pitavastatin 1 mg or 2 mg was administered for 8 weeks to 79 type 2 diabetic patients with hypercholesterolemia who had never been treated with statins, and the effects on the fasting plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), AST, ALT, γ-GTP, and CK levels were evaluated. No statistically significant changes in the fasting plasma glucose levels (from 8.2 ± 2.7 to 8.3 ± 2.1 mmol/L) or HbA1c levels (from 7.3% ± 1.6% to 7.3% ± 1.5%) were observed following administration of pitavastatin. Changes in other clinical laboratories were also not statistically significant. None of the subjects withdrew from the study because of ADRs.85

Glycemic control was retrospectively evaluated in type 2 diabetic patients receiving atorvastatin 10 mg (n = 99), pravastatin 10 mg (n = 85), or pitavastatin 2 mg (n = 95) for 3 months. The random blood glucose and HbA1c levels deteriorated only in the atorvastatin group.86

A basic research was conducted to examine glucose uptake by insulin under administration of atorvastatin, simvastatin, pravastatin, or pitavastatin using 3T3-L1 cells. Glucose uptake was reduced in the atorvastatin and simvastatin groups, while no change was observed in the pravastatin or pitavastatin group. Reduction of solute carrier family 2, member 4 (SLC2A4) and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) α expressions, involved in glucose uptake by cells, may occur, leading to a decrease of the glucose uptake following administration of atorvastatin.87

Patient-focused outcomes

To detect 99% or more of unknown ADRs with an incidence of 0.05% or more, the LIVALO Effectiveness and Safety (LIVES) study was conducted in about 20000 patients with hypercholesterolemia or familial hypercholesterolemia for up to 2 years. A total of 20,279 patients were enrolled from 2811 facilities. The Treatment Outcome Study reported the analyzed results for 3 months after the initiation of pitavastatin administration. According to the results of 3-month treatment, the incidence of ADRs was 6.1% (1206/19921 patients).88 As for the treatment outcome studies of other strong statins, the incidence of ADRs was 12.0% (576/4805 patients) for Lipitor® (atorvastatin) and 11.1% (978/8795 patients) for Crestor® (rosvastatin). The incidence of ADRs to pitavastatin was about a half compared with the above incidences.89,90

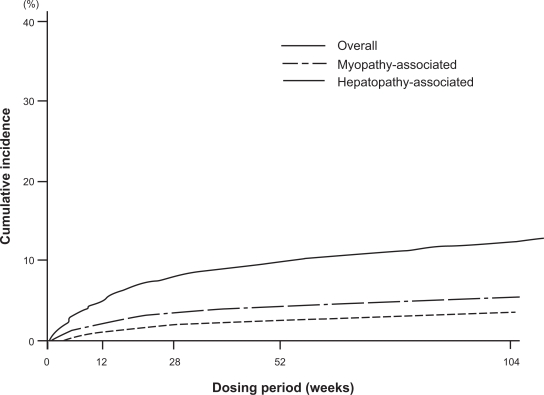

According to the analyzed results after 2 years of pitavastatin administration, the incidence of ADRs was 10.4%. Regarding the main ADRs of statins, the incidence of ADRs related to the musculoskeletal system was 2.1%, and that related to liver dysfunction was 1.0%. According to the severity, mild ADRs occurred in 1045 patients, moderate in 155, and severe in 6 patients. Almost all of the ADRs were classified as mild. Table 2 shows the major ADRs. The major ADRs, CK increased and transaminase increased, occurred less frequently than that noted with other strong statins. The ADRs related to glucose metabolism or the kidneys, notable new ADRs of strong statins, scarcely occurred. In the stratified analysis on the occurrence of ADRs by the concomitantly administered drugs, no significant increase in the incidence of ADRs was observed even when azole antifungals, macrolide antibiotics, or coumarin anticoagulants, which should be given with care due to drug–drug interactions though CYPs for other statins, were administered concomitantly. In addition, concomitant administration of various antiplatelet, antihypertensive and/or antidiabetic drugs did not significantly increase the incidence of ADRs. These results suggest the absence of any special problems related to drug-drug interactions for pitavastatin. Figure 6 shows the presumed cumulative incidence of ADRs using the Kaplan-Meier method over 2 years after the initiation of pitavastatin treatment. The incidence rose gradually from 12 weeks to 52 weeks, with no abrupt increase in the incidence of ADRs.91

Figure 6.

Cumulative incidence of adverse drug reactions by Kaplan-Meier method in LIVES study.91

Modified from Kurihara et al.91

The results at 104 weeks have been analyzed until date, and the LIVES-Extension study is ongoing; it is expected to be carried out for another 3 years, with total follow-up duration of 5 years.

Conclusion

Cerivastatin was withdrawn from the market due to reports of fatal rhabdomyolysis induced by high-doses of cerivastatin or drug–drug interactions caused by coadministration of gemfibrozil. Recently, strong statins such as atorvastatin and rosuvastatin have been widely used for their potent LDL-C-lowering effect at the initial dose, and combinations of these drugs with ezetimibe have been more frequently applied than increase in the dose of the statins. However, serum LDL-C treatment goal have not been achieved in high-risk patients, particularly those with multiple risk factors for CHD in routine clinical settings in Europe, the US, or Japan. Therefore, since high-dose statin administration should be avoided, it is anticipated that a new drug to be coadministered with statins will appear as an alternative to ezemitibe in the future.

Pitavastatin is a strong statin with the same LDL-C-lowering effect as that of atorvastatin at the initial dose and associated with minimal drug–drug interactions. Although various LDL-C-lowering drugs under development are expected to become available for clinical use in the future, the use of statins as the mainstay for the treatment of dyslipidemias appears to remain unchanged. Therefore, pitavastatin may have the potential to become the standard drug for dyslipidemia treatment because of its potent LDL-C-lowering effect, equivalent to that of atorvastatin at the initial dose, and association with minimal drug–drug interactions.

Moreover, pitavastatin has TG-lowering and HDL-elevating effects, and is anticipated to be useful in improving the overall lipid profile. In particular, serum HDL-C elevation by pitavastatin is superior to that observed for atorvastatin. These pitavastatin profiles are favorable for the treatment of metabolic syndrome patients, which is a major concern in developed countries because of its association with a high risk of CHD. The reasons why pitavastatin would be favored for the treatment of metabolic syndrome are as follows. First, the serum LDL-C levels are not markedly elevated in most patients with metabolic syndrome, however, these patients also require sufficient decrease of the serum LDL-C because of the associated high risk of CHD. Second, patients with metabolic syndrome frequently show elevated serum TG and reduced serum HDL-C levels, and statin monotherapy is often inadequate for satisfactory overall control of the lipid profile. Since pitavastatin is a strong statin associated with a low risk of drug–drug interactions, there is little concern about drug–drug interactions when it is administered to patients with metabolic syndrome in combination with antihypertensive and/or antidiabetic agents. Therefore, pitavastatin may have the potential to become the standard drug for the treatment of metabolic syndrome, because it is suitable for improving the overall lipid profile in patients with metabolic syndrome, the incidence of which appears to continue to increase throughout the world, and the drug is associated with a low risk of drug–drug interactions.

In conclusion, pitavastatin is strongly expected to become a standard agent for the treatment of dyslipidemia, especially for the treatment of dyslipidemia in patients with metabolic syndrome.

Acknowledgments/disclosures

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ueshima H, et al. Executive summary of Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) guideline for diagnosis and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases for Japanese. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2007;14(2):45–50. doi: 10.5551/jat.14.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines Circulation 20041102227–239.Erratum in: Circulation 2004;110(6):763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: full text. Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14(Suppl 2):S1–S113. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000277983.23934.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brugts JJ, Yetgin T, Hoeks SE, et al. The benefits of statins in people without established cardiovascular disease but with cardiovascular risk factors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2009;338:b2376. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson MH, Maki KC, Pearson TA, et al. Results of the National Cholesterol Education (NCEP) Program Evaluation ProjecT Utilizing Novel E-Technology (NEPTUNE) II survey and implications for treatment under the recent NCEP Writing Group recommendations. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(4):556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teramoto T, Kashiwagi A, Mabuchi H. Status of lipid-lowering therapy prescribed based on recommendations in the 2002 report of the Japan atherosclerosis society guideline for diagnosis and Treatment of Hyperlipidemia in Japanese Adults: A study of the Japan lipid assessment program (J-LAP) Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2005;66(2):80–95. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barter P, Gotto AM, LaRosa JC, et al. Treating to New Targets Investigators. HDL cholesterol, very low levels of LDL cholesterol, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(13):1301–1310. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dembowski E, Davidson MH. A review of lipid management in primary and secondary prevention. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2009;29(1):2–12. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e318192754e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. INTERHEART Study Investigators Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClure DL, Valuck RJ, Glanz M, et al. Statin and statinfibrate use was significantly associated with increased myositis risk in a managed care population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(8):812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamazaki H, Fujino H, Kanazawa M, et al. Pharmacological and pharmacokinetic features and clinical effects of pitavastatin (Livalo Tablet®). [In Japanese] Folia Pharmacol Jpn. 2004;123:349–362. doi: 10.1254/fpj.123.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aoki T, Nishimura H, Nakagawa S, et al. Pharmacological profile of a novel synthetic inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase. Arzneimittelforschung. 1997;47(8):904–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morikawa S, Umetani M, Nakagawa S, et al. Relative induction of mRNA for HMG CoA reductase and LDL receptor by five different HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors in cultured human cells. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2000;7(3):138–144. doi: 10.5551/jat1994.7.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki H, Aoki T, Tamaki T, et al. Hypolipidemic effect of NK-104, a potent HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, in guinea pigs. Atherosclerosis. 1999;146(2):259–270. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00146-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maejima T, Yamazaki H, Aoki T, et al. Effect of pitavastatin on apolipoprotein A-I production in HepG2 cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324(2):835–839. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross R. Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takemoto M, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21(11):1712–1719. doi: 10.1161/hq1101.098486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki H, Kobayashi H, Sato F, et al. Plaque-stabilizing effect of pitavastatin in Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic (WHHL) rabbits. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2003;10(2):109–116. doi: 10.5551/jat.10.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kibayashi E, Urakaze M, Kobashi C, et al. Inhibitory effect of pitavastatin (NK-104) on the C-reactive-protein-induced interleukin-8 production in human aortic endothelial cells. Clin Sci (Lond) 2005;108(6):515–521. doi: 10.1042/CS20040315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiraoka M, Nitta N, Nagai M, et al. MCP-1-induced enhancement of THP-1 adhesion to vascular endothelium was modulated by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor through RhoA GTPase-, but not ERK1/2-dependent pathway. Life Sci. 2004;75(11):1333–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morikawa S, Takabe W, Mataki C, et al. The effect of statins on mRNA levels of genes related to inflammation, coagulation, and vascular constriction in HUVEC. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2002;9(4):178–183. doi: 10.5551/jat.9.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markle RA, Han J, Summers BD, et al. Pitavastatin alters the expression of thrombotic and fibrinolytic proteins in human vascular cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003;90(1):23–32. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masamura K, Oida K, Kanehara H, et al. Pitavastatin-induced thrombomodulin expression by endothelial cells acts via inhibition of small G proteins of the Rho family. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(3):512–517. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000060461.64771.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakano K, Egashira K.Pitavastatin has most potent pro-healing effects on endothelial cells and inhibitory effects on proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells-a potential treatment strategy for drug-eluting stentsThe 41st Annual Scientific Meeting of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society (July, 2009) general presentation No. 21.

- 26.Morikawa S, Takabe W, Mataki C, et al. Global analysis of RNA expression profile in human vascular cells treated with statins. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2004;11(2):62–72. doi: 10.5551/jat.11.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoue K, Sugiyama A, Reid PC, et al. Establishment of a high sensitivity plasma assay for human pentraxin3 as a marker for unstable angina pectoris. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(1):161–167. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000252126.48375.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoue I, Itoh F, Aoyagi S, et al. Fibrate and statin synergistically increase the transcriptional activities of PPARalpha/RXRalpha and decrease the transactivation of NFkappaB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290(1):131–139. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sagara N, Kawaji T, Takano A, et al. Effect of pitavastatin on experimental choroidal neovascularization in rats. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84(6):1074–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohno M, Shinomiya K, Abe S, et al. Inhibition of migration and proliferation of rat vascular smooth muscle cells by a new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, pitavastatin. Hypertens Res. 2002;25(2):279–285. doi: 10.1291/hypres.25.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han J, Zhou X, Yokoyama T, et al. Pitavastatin downregulates expression of the macrophage type B scavenger receptor, CD36. Circulation. 2004;109:790–796. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112576.40815.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawakami A, Tani M, Chiba T, et al. Pitavastatin inhibits remnant lipoprotein-induced macrophage foam cell formation through ApoB48 receptor-dependent mechanism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(2):424–429. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000152632.48937.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hiraoka M, Yoshida M. A novel HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, pitavastatin inhibits IL-6-induced CRP in liver cells via ERK1/2-dependent but not STAT3-dependent signaling transduction. Circ J. 2003;67(Suppl 1):271. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chinen I, Shimabukuro M, Yamakawa K, et al. Vascular lipotoxicity: endothelial dysfunction via fatty-acid-induced reactive oxygen species overproduction in obese Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Endocrinology. 2007;148(1):160–165. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ota K, Suehiro T, Arii K, et al. Effect of pitavastatin on transactivation of human serum paraoxonase 1 gene. Metabolism. 2005;54(2):142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimata H, Fujino H, Koide T, et al. Studies on the metabolic fate of NK-104, a new Inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase (1): Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion in rats. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1998;13(5):484–498. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujino H, Yamada I, Shimada S, et al. Metabolic fate of pitavastatin, a new inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase: human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes involved in lactonization. Xenobiotica. 2003;33(1):27–41. doi: 10.1080/0049825021000017957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujino H, Saito T, Tsunenari Y, et al. Metabolic properties of the acid and lactone forms of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Xenobiotica. 2004;34(11–12):961–971. doi: 10.1080/00498250400015319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukhtar RY, Reid J, Reckless JP. Pitavastatin. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(2):239–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujino H, Yamada I, Kojima J, et al. Studies on the metabolic fate of NK-104, a new inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase. (5). In vitro metabolism and plasma protein binding in animals and humans. Xenobio Metabol Dispos. 1999;14(6):415–424. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakaya N, Tateno M, Nakamura T, et al. Pharmacokinetics of reported dose NK-104 (pitavastatin) in healthy elderly and non-elderly volunteers [in Japanese] J Clin Therap Med. 2001;17(6):957–970. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ando H, Tsuruoka S, Yanagihara H, et al. Effects of grapefruit juice on the pharmacokinetics of pitavastatin and atorvastatin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60(5):494–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02462.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakaeda T, Fujino H, Komoto C, et al. Effects of acid and lactone forms of eight HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on CYP-mediated metabolism and MDR1-mediated transport. Pharm Res. 2006;23(3):506–512. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-9371-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirano M, Maeda K, Shitara Y, et al. Contribution of OATP2 (OATP1B1) and OATP8 (OATP1B3) to the hepatic uptake of pitavastatin in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311(1):139–146. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.068056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hasunuma T, Nakamura M, Yaji T, et al. The drug-drug interactions of pitavastatin (NK-104), a novel HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor and cyclosporine [in Japanese] J Clin Therap Med. 2003;19(4):381–389. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neuvonen PJ, Niemi M, Backman JT. Drug interactions with lipid-lowering drugs: mechanisms and clinical relevance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80(6):565–581. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fujino H, Yamada I, Shimada S, et al. Metabolic fate of pitavastatin, a new inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase–effect of cMOAT deficiency on hepatobiliary excretion in rats and of mdr1a/b gene disruption on tissue distribution in mice. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2002;17(5):449–456. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.17.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hui CK, Cheung BM, Lau GK. Pharmacokinetics of pitavastatin in subjects with Child-Pugh A and B cirrhosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59(3):291–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakaya N, Tateno M, Nakamura T, et al. Pharmacokinetics of repeated dose NK-104 (pitavastatin) in healthy elderly and non-elderly volunteers [in Japanese] J Clin Therap Med. 2001;17(6):957–970. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jacobson TA. The safety of aggressive statin therapy: how much can low-density lipoprotein cholesterol be lowered? Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(9):1225–1231. doi: 10.4065/81.9.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hayashi T, Yokote K, Saito Y, et al. Pitavastatin: efficacy and safety in intensive lipid lowering. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007 Oct;8(14):2315–2327. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.14.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saito Y, Teramoto T, Yamada N, et al. Clinical Efficacy of NK-104 (Pitavastatin), a New Synthetic HMG-CoA Reductase inhibitor, in the Dose Finding, Double Blind, Three-group Comparative Study [in Japanese] J Clin Therap Med. 2001;17(6):829–855. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saito Y, Yamada N, Teramoto T, et al. A randomized, double-blind trial comparing the efficacy and safety of pitavastatin versus pravastatin in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis. 2002;162(2):373–379. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00712-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakaya N, Saito Y, Morisaki N, et al. Phase II Clinical Study of NK-104 (Pitavastatin) in Patients with Hyperlipidemia [in Japanese] J Clin Therap Med. 2001;17(6):789–806. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park S, Kang HJ, Rim SJ, et al. A randomized, open-label study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pitavastatin compared with simvastatin in Korean patients with hypercholesterolemia. Clin Ther. 2005;27(7):1074–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Budinski D, Arneson V, Hounslow N, et al. Pitavastatin compared with atorvastatin in primary hypercholesterolemia or combined dyslipidemia. Clinical Lipidology. 2009;4(3):291–302. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ose L, Budinski D, Hounslow N, et al. Comparison of Pitavastatin to Simvastatin in Primary Hypercholesterolemia or Combined Dyslipidemia Curr Med Res Opin 2009. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kajinami K, Koizumi J, Ueda K, et al. Effects of NK-104, a new hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme reductase inhibitor, on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Hokuriku NK-104 Study Group. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85(2):178–183. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olsson AG, Istad H, Luurila O, et al. Rosuvastatin Investigators Group Effects of rosuvastatin and atorvastatin compared over 52 weeks of treatment in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Am Heart J. 2002;144(6):1044–1051. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.128049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teramoto T, Saito Y, Yamada N, et al. Clinical safety and efficacy of NK-104 (pitavastatin), a new synthetic HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, in the long-term treatment of hyperlipidemia – results of a multicenter long-term study. [in Japanese] J Clin Therap Med. 2001;17(6):885–913. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fukutomi T, Takeda Y, Suzuki S, et al. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and apolipoprotein A-I are persistently elevated during long-term treatment with pitavastatin, a new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor Int J Cardiol 200910[Epub Jan 12 2009]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kawano M, Nagasaka S, Yagyu H, et al. Pitavastatin decreases plasma prebeta1-HDL concentration and might promote its disappearance rate in hypercholesterolemic patients. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2008;15(1):41–46. doi: 10.5551/jat.e532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sasaki J, Ikeda Y, Kuribayashi T, et al. A 52-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group comparison of the tolerability and effects of pitavastatin and atorvastatin on high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and glucose metabolism in Japanese patients with elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and glucose intolerance. Clin Ther. 2008;30(6):1089–10101. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yokote K, Bujo H, Hanaoka H, et al. Multicenter collaborative randomized parallel group comparative study of pitavastatin and atorvastatin in Japanese hypercholesterolemic patients: collaborative study on hyper-cholesterolemia drug intervention and their benefits for atherosclerosis prevention (CHIBA study) Atherosclerosis. 2008;201(2):345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sasaki J, Ikeda Y, Yamamoto K, et al. Effect of NK-104 (Pitavastatin) on Serum Lipids in Patients with Hypertriglyceridemia – Double-Blind, Cross-Over Placebo Controlled Study – [in Japanese] J Clin Therap Med. 2001;17(6):807–827. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sone H, Takahashi A, Shimano H, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor decreases small dense low-density lipoprotein and remnant-like particle cholesterol in patients with type-2 diabetes. Life Sci. 2002;71(20):2403–2412. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)02038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koshiyama H, Taniguchi A, Tanaka K, et al. Kansai Investigation of Statin for Hyperlipidemic Intervention in Metabolism and Endocrinology Investigators. Effects of pitavastatin on lipid profiles and high-sensitivity CRP in Japanese subjects with hypercholesterolemia: Kansai Investigation of Statin for Hyperlipidemic Intervention in Metabolism and Endocrinology (KISHIMEN) investigatars. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2008;15(6):345–350. doi: 10.5551/jat.e581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nozue T, Michishita I, Ito Y, et al. Effects of statin on small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and remnant-like particle cholesterol in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2008;15(3):146–153. doi: 10.5551/jat.e552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takashima H, Ozaki Y, Yasukawa T, et al. Impact of lipid-lowering therapy with pitavastatin, a new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, on regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque. Circ J. 2007;71(11):1678–1684. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nakamura T, Obata JE, Kitta Y, et al. Rapid stabilization of vulnerable carotid plaque within 1 month of pitavastatin treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;51(4):365–371. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318165dcad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hiro T, Kimura T, Morimoto T, et al. Effect of intensive statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a multi-center randomized trial evaluated by volumetric intravascular ultrasound using pitavastatin versus atorvastatin (JAPAN-ACS Study) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nozue T, Yamamoto S, Tohyama S. Treatment with statin on atheroma regression evaluated by intravascular ultrasound with Virtual Histology (TRUTH Study): rationale and design. Circ J. 2009;73(2):352–355. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Inami N, Nomura S, Shouzu A, et al. Effects of pitavastatin on adiponectin in patients with hyperlipidemia. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2007;36(1):1–8. doi: 10.1159/000112633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sakabe K, Fukuda N, Fukuda Y, et al. Comparisons of short-and intermediate-term effects of pitavastatin versus atorvastatin on lipid profiles, fibrinolytic parameter, and endothelial function. Int J Cardiol. 2008;125(1):136–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aoyagi T, Nakamura F, Tomaru T, et al. Beneficial effects of pitavastatin, a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitor, on cardiac function in ischemic and nonischemic heart failure. Int Heart J. 2008;49(1):49–58. doi: 10.1536/ihj.49.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nakamura T, Sugaya T, Kawagoe, et al. Effect of pitavastatin on urinary liver-type fatty-acid-binding protein in patients with nondiabetic mild chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2006;26(1):82–86. doi: 10.1159/000091956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Majima T, Shimatsu A, Komatsu Y, et al. Short-term effects of pitavastatin on biochemical markers of bone turnover in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Intern Med. 2007;46(24):1967–1973. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.ClinicalTrialsgov [web site on the Internet] United States: the US National Institute of Health; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00301392: Japan Prevention Trial of Diabetes by Pitavastatin in Patients With Impaired Glucose Tolerance (J-PREDICT) [updated on 2007 Jan 19; cited on 2006 Mar 5] Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/

- 79.Tajima S. HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitor LIVALO Tablet [in Japanese] In: Hosoda S, Sasayama S, Kitamura S, editors. The series of advanced medicine, No 28 Cardiac Diseases “The frontier of diagnosis and treatment of cardiac diseases”. Tokyo: Research Center for Advanced Medical Technology; 2004. pp. 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kawashiri MA, Nohara A, Tada H, et al. Comparison of effects of pitavastatin and atorvastatin on plasma coenzyme Q10 in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: results from a crossover study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83(5):731–739. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sever PS, Dahlöf B, Poulter NR, et al. ASCOT investigators Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial – Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9364):1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12948-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sabatine MS, Wiviott SD, Morrow DA, et al. Highi-Dose Atorvastatin Associated with Glycemic Control: A PROVE-IT TIMI 22 Substudy. Circulation. 2004;110(Suppl I):S834. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Colhoun HM, Betteridge DJ, Durrington PN, et al. CARDS investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9435):685–696. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. JUPITER Study Group Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2195–2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kawai T, Tokui M, Funae O, et al. Efficacy of pitavastatin, a new HMG-CoA reductase Inhibitor, on lipid and glucose metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(12):2980–2981. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.12.2980-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yamakawa T, Takano T, Tanaka S, et al. Influence of pitavastatin on glucose tolerance in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2008;15(5):269–275. doi: 10.5551/jat.e562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakata M, Nagasaka S, Kusaka I, et al. Effects of statins on the adipocyte maturation and expression of glucose transporter 4 (SLC2A4): implications in glycaemic control. Diabetologia. 2006;49(8):1881–1892. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kurihara Y, Douzono T, Kawakita K, et al. A large-scale, prospective post-marketing surveillance of pitavastatin (LIVALO® Tablet) – drug use investigation. [in Japanese] Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 2007;5(1):9–40. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Komano N, Masaki M, Kawai H, et al. The safety and efficacy in post-marketing surveys of atorvastatin. [in Japanese] Prog Med. 2005;25(1):131–142. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yoshida S. Crestor: Safety and efficacy in clinical esperience investigation. [in Japanese] Prog Med. 2007;27(5):1159–1189. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kurihara Y, Douzono T, Kawakita K, et al. A large-scale, long-term, prospective post-marketing surveillance of pitavastatin (LIVALO® Tablet) – LIVALO Effectiveness and Safety (LIVES) Study. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 2008;36(8):709–731. [Google Scholar]