Abstract

Objectives

Advanced care planning (ACP) is a process that includes discrete steps of contemplation, discussions, and documentation. Whereas prior studies have assessed barriers to single ACP steps, this study explored barriers to multiple ACP steps and identified common barrier themes that impede older adults from engaging in the process as a whole.

Design

Descriptive study

Setting

San Francisco County, General Medicine clinic

Participants

143 English/Spanish-speakers, aged ≥50 years (mean 61), enrolled in an advance directive preference study.

Measurement

Six months after reviewing two advance directives, self-reported ACP engagement and barriers to each ACP step were measured with both open- and closed-ended questions using quantitative and qualitative (thematic content) analyses.

Results

Forty percent of participants did not contemplate ACP, 46% did not discuss with family/friends, 80% did not discuss with their doctor, and 90% did not document ACP wishes. Six barrier themes emerged: perceiving ACP as irrelevant (84%); personal barriers (53%); relationship concerns (46%); information needs (36%); health encounter time constraints (29%), and problems with advance directives (29%). Some barriers were endorsed at all steps (e.g., perceiving ACP as irrelevant). Others were endorsed at individual steps (e.g., relationship concerns for family/friend discussions, time constraints for doctor discussions, and problems with advance directives for documentation).

Discussion

Perceiving ACP to be irrelevant was the barrier theme most often endorsed at every ACP step. Other barriers were endorsed at specific steps. Understanding ACP barriers may help clinicians prioritize and address them and may also provide a framework for tailoring interventions to improve ACP engagement.

Keywords: advance care planning, communication, decision-making, health disparities

INTRODUCTION

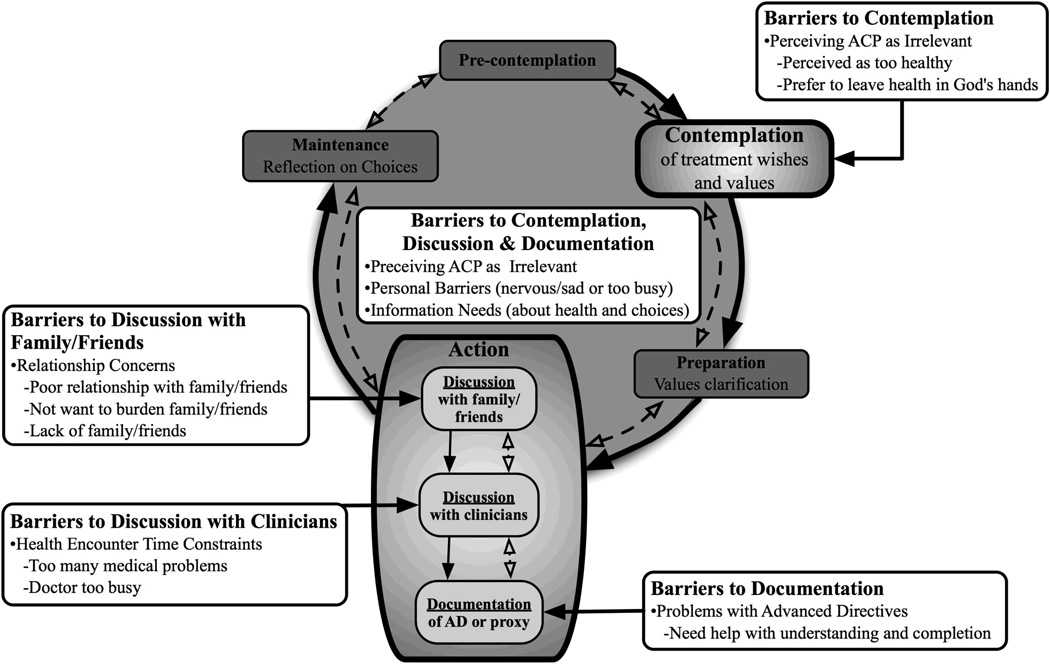

A conceptual model of the advance care planning (ACP) process based on the transtheoretical behavior change model was recently described in JAGS, 2008.1 (Figure 1) This model describes the ACP process in terms of a set of discrete steps including contemplation of one’s values and future treatment wishes, discussions with family and friends, discussions with clinicians, and documentation.1, 2

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model Demonstrating Barriers to 4 Steps of the Advance Care Planning Process* †

Identifying barriers to each step of the ACP process can guide clinicians in their efforts to help patients engage in the process and advance to the next appropriate ACP step. Many prior studies have focused solely on barriers to documentation of an advance directive (e.g., having difficulty completing the forms and wanting to delay the decision),3 while often ignoring other important steps in the ACP process such as contemplation and discussions.3–10 Also, most prior barrier studies have only included homogeneous groups in terms of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.8–11 Some studies have identified immutable predictors of poor engagement in contemplation and discussion of ACP (e.g., female gender, years of education).7, 12–14 However; little is know about patient-identified barriers to multiple steps of the ACP process, which may be more clinically amenable to intervention than demographic predictors.15

To our knowledge, no prior study has explored the self-identified barriers that impede diverse older adults from engaging in multiple, discrete steps of the ACP process after exposure to an advance directive intervention. Exposure to an intervention, such as advance directives which are available in most clinical settings, may help to standardize patients’ experiences about advance care planning. Therefore, barriers to multiple steps of the ACP process were assessed among diverse older adults from an urban, county general medicine clinic. Four steps of the ACP process were assessed: contemplation of one’s treatment wishes; discussion of ACP with family or friends; discussion of ACP with one’s doctor; and documentation of one’s treatment wishes in an advance directive.1 Patient-identified barriers to each ACP step were then elicited and common barrier themes to the ACP process were identified. Assessing barriers to multiple steps of the ACP process could provide a clinical framework to guide clinicians in their efforts to help patients engage in ACP and advance to the next appropriate ACP step.1

METHODS

Participants and Study Design

For this descriptive study, telephone interviews were conducted between February and July of 2005, six months after a sample of 205 general medicine patients from San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH) enrolled in an advance directive preference study.16 Participants were included if they were 50 years or older and reported fluency in English or Spanish. Primary physicians had to grant permission before study staff could invite their patients for participation. Participants were not eligible if their physicians determined them to be deaf, delirious, demented, or too ill to participate. At six months, six of the 205 participants refused further participation and 26 could not be reached, resulting in a response rate of 84%. The 32 participants lost to follow-up did not differ from the remaining sample except they were more likely to have limited versus adequate literacy (65% vs. 35%, P=.001). Because we were interested in assessing barriers to ACP as a result of exposure to an advance directive, 26 participants who had completed an advance directive prior to enrolling in the preference study were excluded from the analysis. Four participants who had engaged in every ACP step were also excluded because, per the barriers study protocol, these participants were not asked about barriers to ACP. Therefore, 143 participants were available for this analysis. The 30 participants who were excluded did not differ from the remaining sample except that they were more likely to be white versus non-white (57% vs. 43%, P=.02). The University of California, San Francisco and SFGH institutional review board approved this study.

During the advance directive preference study, participants reviewed two advance directive forms in English or Spanish– a standard form written at a 12th grade reading level and a redesigned form containing graphics and written at a 5th grade reading level. The details of the preference study have been described previously.16 No additional follow-up or educational interventions were given to participants beyond the information contained in the advance directives. Patients were told that in six-months we would call to ask more questions about the forms, but not about advance care planning. Six-month telephone interviews were conducted in English or Spanish by bilingual research assistants who followed an extensively pilot-tested interview script.

Outcomes

Based on our prior work,1 the degree of engagement in the ACP steps of contemplation, discussions with family and friends, discussions with clinicians, and documentation were assessed.(Figure 1) Each ACP step could have been completed independently; therefore, engagement in each ACP step was assessed separately. To assess engagement in the ACP steps participants were asked, “Since the day you finished the study, have you thought about [or “talked with your family or friends about” or “talked with your doctor about”] the type of medical care you might want if you were sick or near the end of your life?” To assess engagement in the ACP step of documentation, participants were asked “Since the day you finished the study, have you tried to or have you filled out an advance directive for yourself?” For these analyses, the percentage of participants who did not engage in each ACP step was reported.

For participants who did not engage in ACP, the barriers experienced for each individual ACP step were assessed by asking both open and closed-ended questions in structured interviews. Participants were asked to complete the statements “You haven’t thought about [or “talked to your family and friends about” or “talked to your doctor about”] the type of medical care you might want because…,” and “You haven’t filled out an advance directive form because…” Participants ended these statements by first endorsing closed-ended barriers read to them from a list pre-defined by previous literature (Table 1).4, 17, 18 To ensure all barriers were elicited, for each ACP step participants were also asked the open-ended question “Are there any other reasons?” Participants could endorse multiple open- and closed-ended barriers at each ACP step. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Barriers to 4 Advance Care Planning Steps According to Whether They Were Elicited Through Closed-ended or Open-ended Questions*

| BARRIERS IDENTIFIED BY CLOSED-ENDED QUESTIONS “yes/no” | BARRIERS IDENTIFIED BY THE OPEN-ENDED QUESTION “Are there any other reasons?” |

|---|---|

| Contemplation | |

| You think that you are too healthy | I have not given it much thought |

| You are too busy† | I don’t want to think about death, |

| You don’t have enough information about your health or healthcare choices | I’d rather leave the choice to others |

| Thinking about it makes you nervous, sad or depressed | My wishes are already known |

| You prefer to leave your health in God’s hands | I need help understanding the forms |

| Discussion with family and friends | |

| You don’t have any family or friends† | I am too busy |

| You think that you are too healthy | My family and friends already know my wishes |

| You don’t have enough information about your health or choices for care | I prefer to leave my health to fate |

| It makes you nervous, sad, or depressed | |

| You don’t want to worry your family or friends† | |

| You don’t feel comfortable bringing it up† | |

| Your family or friends don’t want to talk about it with you† | |

| You don’t trust your family or friends† | |

| This is your choice and you don’t want family or friends involved† | |

| You feel bad things will happen to your health if you do talk about it | |

| You prefer to leave your health in God’s hands | |

| Discussion with doctor | |

| You think that you are too healthy | I am too busy |

| You don’t have enough information about your health or choices for care | I have not given it much thought |

| It makes you nervous, sad, or depressed | I need help understanding the forms |

| You don’t trust your doctor† | I don’t want to think about death, I’d rather leave the |

| You don’t feel comfortable bringing it up to your doctor† | choice to others |

| You haven’t seen your doctor† | My doctor already knows my wishes |

| Your doctor is too busy† | |

| You have too many medical problems to talk to your doctor about† | |

| Your doctor does not want to talk about it with you† | |

| You feel bad things will happen to your health if you do talk about it | |

| You prefer to leave your health in God’s hands | |

| Documentation | |

| You think you are too healthy | I need help understanding the forms |

| You don’t have enough information about your health or choices for care | I have not given it much thought |

| Filling it out would make you nervous, sad, or depressed | I lost the form |

| You don’t like to fill out forms that have to do with your medical care† | I am busy |

| The forms are too hard to fill out† | I don’t want to think about death, I’d rather leave the |

| You don’t know what an advance directive form is for† | choice to others |

| You feel that bad things will happen to your health if you fill out the form | My wishes are already known |

| You prefer to leave your health in God’s hands | I have poor relationships with family, friends |

We inquired about barriers to four ACP steps; contemplation, discussions with family and friends, discussions with physicians, and documentation.

When assessing barriers to specific steps, such as barriers to discussions with family/friends, discussions with clinicians, and documentation, some of the close-ended barriers only pertained to those individual steps. The barriers only asked at specific steps are labeled with a † symbol. Based on prior literature, some of the closed-ended barriers were thought to be relevant and potentially universal to all four ACP steps (e.g., thinking “You are too healthy” for ACP), and, therefore, were asked about at every ACP step. 4, 17, 18 The barriers asked at every ACP step are not labeled.

Other measures

At baseline, participants’ age, race/ethnicity, gender, income (<$10,000/yr vs. ≥$10,000/yr), educational attainment, language, self-rated health status (fair to poor vs. good to excellent), religiosity (very to extremely vs. not very to somewhat), and previous end-of-life experiences (prior admission to the ICU, having family or friends admitted to the ICU, and having helped someone fill out an advance directive) were obtained. Literacy was assessed with the Short Form Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (s-TOFHLA), a 36-item, timed reading comprehension test.19 Scores ≤ 22 were defined as limited literacy (≤ an 8th grade level).20 The s-TOFHLA has a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97), high correlation with other literacy and health literacy assessments (Spearman’s correlation coefficients >.80), and has consistently measured the limited literacy rate at the SFGH to be approximately 40%.19, 21, 22

Data Analysis

Participant characteristics, the extent of non-engagement in each step of the ACP process, and the individual participant-identified barriers to ACP were described with percentages.

Ninety percent (129/143) of participants gave at least one answer to the open-ended questions about why they had not engaged in the four ACP steps. The open-ended responses were transcribed verbatim during the barriers study interview and re-read to participants to ensure accuracy. Two investigators (AS and RS) independently reviewed the transcripts of responses to the open-ended questions using grounded theory.23 Using these results, a thematic content coding schema was developed and transcripts were coded into discrete individual barrier concepts.24 The barriers concepts were compared between the independent coders, and the coding schema was revised by re-reading the transcripts until the reviewers reached >95% agreement. A third investigator read over the coding scheme (SK) to ensure validity and to help resolve discrepancies.

If the open-ended barriers identified by participants were the same or similar to the closed-ended list of barriers, then the open-ended barriers concepts were combined with the close-ended barrier concepts. If the open-ended barriers constituted new information not available in the closed-ended barrier list, the open-ended responses were created as new individual barrier concepts. Then, both the close-ended and new open-ended barrier concepts were assessed together and grouped into overarching barrier themes. The overarching barriers themes were first developed by two investigators (AS and RS) using thematic content analysis.24 A series of groups were then conducted to further refine and identify clinical relevancy of the barrier themes. The barrier themes were first presented to, and further refined by, the full investigative team of geriatricians, palliative care physicians, internists and psychologists. The barrier themes were then further refined after presentation to an additional expert panel of geriatricians and palliative care physicians. When reviewing the overarching barrier themes, the multidisciplinary investigative team and expert panel were asked to discuss the barrier themes in terms of what would be clinically important and amenable to possible future intervention.

The goal of the study was not only to assess barrier themes that occur at each individual ACP step (contemplation, discussions with family/friends, discussions with clinicians, and documentation), but also to assess barriers themes that are important to the ACP process as a whole. Therefore, for each barrier theme, the proportion of participants who endorsed that theme at any of the four ACP steps was calculated.(Table 3)

Table 3.

Barriers, Grouped by Theme, to the Advance Care Planning (ACP) Steps of Contemplation, Discussions, and Documentation*

| Barrier Theme | Individual Participant-Identified Barriers | Overallc† | Not Contemplated ACP Wishes |

Not Discussed ACP with Family |

Not Discussed ACP with Doctor |

Not Documented ACP Wishes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=143 % |

n=59 % |

n=67 % |

n=98 % |

n=131 % |

||

| ACP Perceived to be | I am too healthy c‡ | 41 | 33 | 36 | 32 | |

| Irrelevant | I prefer to leave my health in God’s hands C | 43 | 35 | 28 | 29 | |

| I have not given it much thought O | 21 | - | 21 | 35 | ||

| I prefer to leave my health to fate O | - | 15 | - | - | ||

| My doctor, family and friends already know my decisions O | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Any perceived as irrelevant barriers | 84 | 75 | 64 | 67 | 77 | |

| Personal Barriers | It makes me nervous or sad C | 28 | 19 | 19 | 13 | |

| I don’t want to think about death, I’d rather leave the choice to others O | 16 | - | 4 | - | ||

| I am too busy with work and family O | 40 | 7 | 4 | 18 | ||

| Any personal barriers | 53 | 59 | 27 | 27 | 28 | |

| Relationship Concerns | I have a poor relationship with my family, friends C | - | 36 | - | 2 | |

| I have poor a relationship with my doctor C | - | - | 29 | |||

| I don’t want my family involved C | - | 25 | - | - | ||

| I don’t have family or friends C | - | 22 | - | - | ||

| I don’t want to worry or burden my family, friends C | - | 43 | - | - | ||

| Any relationship barriers | 46 | - | 76 | 30 | 2 | |

| Information Needs | I need more information about my health and/or health care choices C | 29 | 18 | 26 | 22 | |

| I don’t know what an advance directive is C | - | - | - | 15 | ||

| Any informational barriers | 36 | 29 | 18 | 26 | 31 | |

| Health Encounter | I have too many other medical problems C | - | - | 30 | - | |

| Time Constraints | ||||||

| My doctor is too busy C | - | - | 18 | - | ||

| Any time constraint barrier | 29 | - | - | 39 | - | |

| Problems with | I need help understanding the forms O | 5 | - | 5 | 28 | |

| Advance Directive | I do not like to fill out forms in general O | - | - | - | 2 | |

| Form | The advance directive form was not helpful O | - | - | - | 2 | |

| Any problems with advance directives | 29 | 5 | - | 5 | 30 | |

The barrier domains are presented in descending order of prevalence across all of the ACP steps. The total n for each step differs as varying numbers of participants reported not completing individual ACP steps. Participants could endorse multiple barriers for each ACP step.

The Overall column represents all participants (n=143). For each barrier theme, the proportion of participants who endorsed any of the individual barriers at any of the four ACP steps is presented.

“C” represents closed-ended responses participants could choose from a pre-defined list, and “O” represents responses to the open-ended question, “Are there any other reasons?”

Because minorities and participants with lower socioeconomic status have low rates of ACP engagement,25–31 associations between participant characteristics and the barriers themes were measured with χ2 tests and t-tests. Intercooled STATA version 8 software was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

The mean (±SD) age of participants (n=143) was 61 (±9) years. Most were non-white, 52% had yearly incomes less than $10,000, 35% had not completed high school, 38% had limited literacy, and 31% were Spanish-speaking (Table 2). Over two thirds reported fair to poor health and many had prior ICU experiences.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics, n=143

| Characteristic | n (%) or mean (±SD) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (±SD) | 61 years (±9) |

| Women | 77 (54) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 33 (23) |

| White, Hispanic (Latino) | 48 (34) |

| African American, Non-Hispanic | 33 (23) |

| Asian | 11 ( 8) |

| Multi-racial/ethnic, Other | 18 (12) |

| Income <$10,000/yr* | 60 (52) |

| Education: < high school education | 50 (35) |

| Literacy†: Limited literacy | 54 (38) |

| Language: Spanish-speaking | 44 (31) |

| Religiosity: Very to extremely religious | 70 (51) |

| Health Status: Fair to poor self-rated health | 97 (68) |

| Personal End-of-Life Experience | |

| Previously admitted to intensive care unit | 50 (35) |

| Had friends/family admitted to intensive care unit | 87 (61) |

| Helped others fill out advance directive | 20 (14) |

Income data was only available for 116 participants (81%). The 27 participants missing income data did not differ from the remaining sample except they were more likely to be non-White vs. White, specifically, White, Hispanic vs. White, Non-Hispanic (96% vs. 4%, P=.008).

Literacy was assessed using the Short Form test of Functional Literacy in Adults (s-TOFHLA), a 36-item, timed reading comprehension test. Participants with scores ≤ 22 (possible range of 0–36) were considered “limited literacy”.

Advance Care Planning Non-Engagement

Fifty-nine participants (40%) had not contemplated their ACP wishes, 67 (46%) had not discussed ACP with family or friends, 117 (80%) had not discussed ACP with their doctor, and 131 (90%) had not documented their ACP wishes.

Participant-Identified Barriers

Across all four ACP steps, 20 individual barriers to ACP engagement were identified; 12 were from the closed-ended list and 8 were identified from participants’ open-ended responses (Table 3). The individual barriers fell into six overarching barrier themes (Table 3). ACP was perceived to be irrelevant by 84% of all participants; 53% endorsed personal barriers such as emotional issues or work/family responsibilities; 46% had relationship concerns; 36% endorsed information needs such as not having enough information about one’s health or healthcare choices; 29% endorsed health encounter time constraints, and 29% endorsed problems with advance directives (see Table 3 for the individual barriers that comprise these barrier themes). The theme of perceiving ACP to be irrelevant was strongly endorsed by participants at every ACP step, as were personal barriers and information needs.

Specific barrier themes were more commonly endorsed at certain ACP steps (Table 3 and Figure 1). For contemplation, perceiving ACP as irrelevant was frequently endorsed with 75% of all participants who had not contemplated ACP (n=59) endorsing at least one barrier within this theme. Specifically, 43% of participants endorsed that they “preferred to leave their health in God’s hands” and 41% endorsed feeling “too healthy.” Fifty nine percent of all participants who had not contemplated ACP also endorsed personal barriers such as “I am too busy with work and family” (40%) and “thinking about it makes me nervous or sad” (28%).

For the ACP step of discussions with family and friends, relationship concerns were frequently endorsed with 76% of participants who had not spoken to their family or friends about ACP (n=67) endorsing at least one barrier within this theme. Specifically, 43% of participants endorsed the statement “I don’t want to worry or burden my family or friends”, 36% endorsed “I have a poor relationship with my family, friends”, 25% endorsed “I don’t want my family involved”, and 22% endorsed “I don’t have any family or friends”.

For the ACP step of discussions with one’s doctor, health encounter time constraints were frequently endorsed with 39% of all participants who had not spoken to their doctor about ACP (n=98) endorsing at least one barrier within this theme. Specifically, 30% of participants endorsed the statement “I have too many other medical problems to talk to my doctor about” and 18% endorsed “my doctor is too busy.”

For documentation, problems with advance directive forms were frequently endorsed, with 30% of all participants who had not completed an advance directive (n=131) endorsing at least one barrier within this theme. Specifically 28% stated “I need help understanding the forms.”

Only race/ethnicity and education were associated with the barrier themes (table not shown). Latinos were less likely than other groups to endorse personal barriers at all ACP steps (Latinos 29% versus whites 67%, African Americans 63%, Asian/Pacific Islanders 58%, and multi-racial/ethnic persons 72%; P=.001), relationship concerns (Latinos 22% versus whites 61%, African Americans 54%, Asian/Pacific Islanders 50%, and multi-racial/ethnic persons 61%; P=.002), or health encounter time constraints (Latinos 12% versus whites 42%, African Americans 31%, Asian/Pacific Islanders 33%, and multi-racial/ethnic persons 39%; P=.02). Participants with less than a high school education were less likely to endorse personal barriers at all ACP steps compared to those with higher education (40% versus 59%; P=.03) or health encounter time constraints (14% versus 36%; P=.004).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to simultaneously explore the barriers that impede diverse older outpatients from engaging in multiple, discrete steps of the advance care planning process (contemplation, discussions with family/friends, discussions with clinicians, and documentation) six-months after exposure to two advance directives. It is also the first study to identify common barrier themes to the ACP process as a whole. Many participants had not engaged in ACP, and all endorsed barriers to at least one ACP step. Six barrier themes emerged: perceiving ACP to be irrelevant, personal barriers, relationship concerns, information needs, health encounter time constraints, and problems with advance directives. Perceiving ACP as irrelevant was the most common barrier theme endorsed at all ACP steps assessed, as were personal barriers and information needs. The barrier theme of perceiving ACP to be irrelevant was frequently endorsed for the contemplation step, relationship concerns were endorsed for discussions with family and friends, health encounter time constraints were endorsed for discussions with clinicians, and problems with advance directives were endorsed for documentation.

These results build on our prior work which describes ACP in terms of the transtheoretical behavioral change model (pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action such as discussions and documentation, and maintenance) (Figure 1).1 This prior study demonstrated that patients are in varying stages of the ACP process and may only complete those ACP steps that are either the most comfortable or the most appropriate for them (e.g., discussing with family but not completing an advance directive).1 Unfortunately, there is no consensus as to the best method to help patients engage in ACP. Approaches that may help patients engage in individual ACP steps other than documentation (i.e., contemplation and discussions) include exposure to easy-to-understand ACP materials,16 exposure to video images that describe ACP,32, 33 having clinicians initiate discussions with patients,1, 3, 34 and extensive clinician-led discussions about patients values.35–37 Yet, there is no empirical data as to how to empower patients to move to the next appropriate step in the ACP process (e.g., from contemplation to discussions with family and friends). However, understanding patient-perceived barriers at each step of the ACP process can help to provide a framework for tailoring interventions that can assess and target which ACP step patients are ready and willing to engage. Understanding these barriers is also crucial to designing tailored, step-specific interventions to help patients overcome their barriers, engage in ACP, and to move from one ACP step to the next.

Clinical Implications

Our findings may assist clinicians in counseling their patients about ACP and helping them to advance them from one ACP step to the next. When counseling patients, it may be important to first address those barriers that patients experience at every ACP step, namely perceiving ACP as irrelevant, experiencing personal barriers, or having information needs.(Figure 1) Perceiving ACP as irrelevant was the most common barrier and was endorsed at every ACP step, particularly at the contemplation step. Many participants perceived ACP as irrelevant because they perceived themselves as “too healthy,” even though close to 70% reported having fair to poor health and more than a third reported a previous admission to the ICU. Given these results, clinicians may first need to assess where patients are in the ACP process (Figure 1) and whether the are ready to engage in ACP (e.g., Is the patient in the pre-contemplative stage, have they begun to start contemplating their wishes, have they spoken to their family?, etc). Clinicians may then need to elicit patients’ understanding of and discuss the prognoses for their disease processes to help place ACP within the context of their own health circumstances. This may also help with information needs by educating patients about their health and their health care choices. Many participants also perceived ACP as irrelevant because they preferred to leave their health “in God’s hands.” It may, therefore, be important for clinicians to acknowledge patients’ religious beliefs and include patients’ faith within ACP discussions.38, 39 For personal barriers, understanding patients’ work and life stresses, as well as anxiety concerning ACP, can help clinicians individualize their efforts in helping patients engage in ACP. For those patients who experience anxiety, it may lessen if ACP were to become a part of routine outpatient care.40 It may also be beneficial to initiate ACP conversations in a depersonalized manner, such as discussing patients’ reactions to examples from the media (e.g., Terri Schiavo) or discussing patients’ friends’ and family’s previous end-of-life experiences.32 It is important to note, that even after employing the aforementioned strategies, some patients may not be ready to contemplate ACP or be ready to move to the next step. This must be respected. However, maintaining an open dialogue may allow patients to engage if and when they are ready or when circumstances warrant.

In addition to those barriers endorsed at all ACP steps, clinicians may also need to address barriers specific to each individual ACP step to help their patients engage in the next appropriate step in the process.(Figure 1) For discussions with family and friends, clinicians may need to reassure patients that ACP can decrease the stress experienced by their surrogate decision makers41 and to mobilize resources for patients who lack surrogates. For discussions with physicians, lengthy, in-depth ACP discussions are often unrealistic. However, broaching the topic briefly over multiple outpatient visits, scheduling a dedicated ACP visit, or utilizing nurses and social workers can be helpful.40 37, 42 For the documentation step, using literacy and language-appropriate advance directives may be helpful, however, many patients will likely need further one-on-one assistance.16

Research Implications

When designing ACP interventions it may be important to address and target the patient-perceived barriers described in this study in order to help patients engage in ACP and advance to the next ACP step. It may also be important to include a range of outcomes (including contemplation, discussions and documentation) that demonstrate where patients are in the ACP process and whether the intervention helped to advance them to the next appropriate step in the process.1

Prior Research

Prior studies assessing barriers to ACP have either not simultaneously assessed barriers to multiple, discrete steps of the ACP process after exposure to an advance directive, not identified barrier themes to the ACP process as a whole, or not included diverse populations. In the absence of an advance directive intervention, Canadian outpatients reported similar barriers to contemplation, discussions and documentation including a wish to leave the decisions to others, not having a surrogate, and an inability to complete an advance directive.18 However, these barriers were not described in detail, discussed in terms of the ACP process, or grouped by barrier theme. Other ACP barriers studies, most of which either included homogenous populations or focused solely on the documentation step, also found similar barriers such as: religious beliefs, 3, 6–9, 43 and the perception of being “too healthy”4, 5, 11, 17, 44, 45 (perceiving ACP to be irrelevant); preferring to leave the choice to others or discomfort discussing ACP 3, 6–10, 17, 43, 45 (personal barriers); not having an available surrogate decision maker18, 46(relationship concerns); poor knowledge of healthcare options4, 5, 11, 43 (information needs); health encounter time constraints11, 17, 47, 48; and problems with advance directives.3, 6–10, 18 Barriers that did not emerge in this diverse, county population, contrary to other studies, were concerns about mistrust,29 that harm will come by discussing ACP,17, 45and lack of knowledge about ACP.44 This may be due to the unmeasured quality of the doctor-patient relationship or having been exposed to a literacy and language appropriate advance directive.

Although other studies have shown poor engagement in ACP among minority populations and patients with lower education,25–31 this study showed that Latinos and patients with lower education reported fewer personal, relationship, and health encounter time constraint barriers. This may reflect cultural variation, such as the importance Latinos place on family decision making,5, 29specific-doctor patient relationships, or having been exposed to a literacy and language appropriate advance directive.16 Nonetheless, many barriers in this study were endorsed by all patient subgroups such as perceiving ACP to be irrelevant, having informational needs, and needing help with advance directives. These and other barriers should be elicited by clinicians and addressed for all patients.

LIMITATIONS

Because all participants had previously participated in an advance directive intervention with only modest effects on advance care planning,16 these results may only be generalizable to outpatients who have been introduced to the concept of ACP through advance directives. Generalizability may be limited because the study was conducted at one urban medical clinic, however; the sample was quite diverse. The small sample size may have prevented us from eliciting a broader array of barriers from participants and may have led to inadequate power to detect significant associations between barrier themes and other participant socio-demographic characteristics. Presenting patients a predefined list of individual barriers prior to asking the open-ended question may have biased participants’ answers and narrowed the array of barriers elicited. Study information was also obtained by self-report, which may have introduced recall or social desirability bias. In addition, social support, the quality of the participants’ doctor-patient relationships, and patient-physician language concordance were not assessed; characteristics which may have been associated with barriers to discussions with family, friends, and clinicians. We were also unable to explore barriers to pre-contemplation, preparation, or maintenance; ACP steps which should be assessed in future studies.

CONCLUSION

Six barrier themes were found to impede diverse older outpatients from engaging in multiple, discrete steps of the advance care planning process (contemplation, discussions with family/friends, discussions with clinicians, and documentation) six-months after exposure to two advance directives. Perceiving ACP to be irrelevant was the most common barrier theme endorsed at every ACP step as were personal barriers and information needs. Relationship concerns, health encounter time constraints, and problems with advance directives were endorsed at specific ACP steps. Understanding the most prevalent barriers that prevent older adults from engaging in ACP, and in each individual step of the ACP process, may help clinicians anticipate, prioritize, and address these barriers to help their patients engage in the ACP process and advance to the next appropriate ACP step. Understanding these barriers can also help to provide a framework for tailoring interventions to improve ACP, for example: addressing ACP in the context of patients’ prognoses and patients’ religious beliefs for the contemplation step; discussing the concern of burdening surrogate decision makers for discussions with friends and family; finding creative solutions for the lack of time to discuss ACP with clinicians by scheduling dedicated ACP appointments or eliciting help from ancillary services; and using literacy- and language-appropriate advance directives for the documentation step.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding sources and related paper presentations: The abstract of this paper was presented at the American Geriatrics Society conference, Seattle, WA, May 2007. Adam Schickedanz was supported by the NIA funded Medical Student Training in Aging Research. Dr. Sudore was supported by the American Medical Association Foundation; the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging K07 AG000912; the Pfizer Fellowship in Clear Health Communication; the NIH Diversity Investigator Supplement 5R01AG023626-02; and an NIA Mentored Clinical Scientist Award K-23 AG030344-01.

Dr. Sudore is funded in part by the Pfizer Foundation through the Clear Health Communication Fellowship. This Foundation has no financial incentives associated with the results of this study, nor does Dr. Sudore.

Sponsor’s Role: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

The gray boxes demonstrate the advance care planning process based on the transtheoretical behavior model of change described in our prior work.1 In this study, we were able to assess barriers to the contemplation step and the action steps of discussions with family and friends, discussions with clinicians, and documentation.

The black and white boxes depict the barrier themes associated with the advance care planning process. The black and white box in the center of the circle depicts those barrier themes that were identified at all of the advance care planning steps assessed in this study (contemplation, discussion and documentation). Additional black and white boxes depict those barrier themes identified at specific steps in the advance care planning process.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sudore RL, Schickedanz AD, Landefeld CS, et al. Engagement in Multiple Steps of the Advance Care Planning Process: A Descriptive Study of Diverse Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearlman RA, Cole WG, Patrick DL, et al. Advance care planning: eliciting patient preferences for life-sustaining treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 1995;26:353–361. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00739-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramsaroop SD, Reid MC, Adelman RD. Completing an advance directive in the primary care setting: What do we need for success? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:277–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison RS, Zayas LH, Mulvihill M, et al. Barriers to completion of health care proxies: an examination of ethnic differences. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2493–2497. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.22.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrison RS, Meier DE. High rates of advance care planning in New York City's elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2421–2426. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.22.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sachs GA, Stocking CB, Miles SH. Empowerment of the older patient? A randomized, controlled trial to increase discussion and use of advance directives. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:269–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meier DE, Gold G, Mertz K, et al. Enhancement of proxy appointment for older persons: physician counselling in the ambulatory setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb05635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.High DM. Advance directives and the elderly: A study of intervention strategies to increase use. Gerontologist. 1993;33:342–349. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luptak MK, Boult C. A method for increasing elders' use of advance directives. Gerontologist. 1994;34:409–412. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marchand L, Cloutier VM, Gjerde C, et al. Factors influencing rural Wisconsin elders in completing advance directives. WMJ. 2001;100:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knauft E, Nielsen EL, Engelberg RA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to end-of-life care communication for patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;127:2188–2196. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrett DD, Tuokko H, Stajduhar KI, et al. Planning for End-of-Life Care: Findings from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Can J Aging. 2008;27:11–21. doi: 10.3138/cja.27.1.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levin JR, Wenger NS, Ouslander JG, et al. Life-sustaining treatment decisions for nursing home residents: Who discusses, who decides and what is decided? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:82–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahana B, Dan A, Kahana E, et al. The personal and social context of planning for endof-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1163–1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inui TS. The virtue of qualitative and quantitative research. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:770–771. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-9-199611010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Barnes DE, et al. An advance directive redesigned to meet the literacy level of most adults: A randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69:165–195. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis JR, Patrick DL. Barriers to communication about end-of-life care in AIDS patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:736–741. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.07158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sam M, Singer PA. Canadian outpatients and advance directives: Poor knowledge and little experience but positive attitudes. CMAJ. 1993;148:1497–1502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, et al. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seligman HK, Wang FF, Palacios JL, et al. Physician notification of their diabetes patients' limited health literacy. A randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1001–1007. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, et al. The test of functional health literacy in adults: A new instrument for measuring patients' literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:537–541. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA. 2002;288:475–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research. Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flick U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. 2nd Edition. London, England: Sage Publication, Ltd; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V. End-of-life care in black and white: race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1145–1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emanuel LL, Barry MJ, Stoeckle JD, et al. Advance directives for medical care--a case for greater use. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:889–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103283241305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hofmann JC, Wenger NS, Davis RB, et al. Patient preferences for communication with physicians about end-of-life decisions. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preference for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:1–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-1-199707010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanson LC, Rodgman E. The use of living wills at the end of life. A national study. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1018–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krakauer EL, Crenner C, Fox K. Barriers to optimum end-of-life care for minority patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:182–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKinley ED, Garrett JM, Evans AT, et al. Differences in end-of-life decision making among black and white ambulatory cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:651–656. doi: 10.1007/BF02600155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hopp FP. Preferences for surrogate decision makers, informal communication, and advance directives among community-dwelling elders: Results from a national study. Gerontologist. 2000;40:449–457. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Pantilat SZ, et al. Using the Medial to Initiate Advance Care Planning. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;54(4 Suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volandes AE, Lehmann LS, Cook EF, et al. Using video images of dementia in advance care planning. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:828–833. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duffield P, Podzamsky JE. The completion of advance directives in primary care. J Fam Pract. 1996;42:378–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammes BJ. What does it take to help adults successfully plan for future medical decisions? J Palliat Med. 2001;4:453–456. doi: 10.1089/109662101753381584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz CE, Wheeler HB, Hammes B, et al. Early intervention in planning end-of-life care with ambulatory geriatric patients: Results of a pilot trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1611–1618. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.14.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Briggs LA, Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, et al. Patient-centered advance care planning in special patient populations: A pilot study. J Prof Nurs. 2004;20:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puchalski C, Romer AL. Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:129–137. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lo B, Ruston D, Kates LW, et al. Discussing religious and spiritual issues at the end of life: a practical guide for physicians. JAMA. 2002;287:749–754. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipkin KM. Brief report: identifying a proxy for health care as part of routine medical inquiry. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1188–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00570.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baker R, Wu AW, Teno JM, et al. Family satisfaction with end-of-life care in seriously ill hospitalized adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S61–S69. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morrison RS, Chichin E, Carter J, et al. The effect of a social work intervention to enhance advance care planning documentation in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:290–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glass AP, Nahapetyan L. Discussions by elders and adult children about end-of-life preparation and preferences. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A08. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freer JP, Eubanks M, Parker B, et al. Advance directives: Ambulatory patients' knowledge and perspectives. Am J Med. 2006;119(1088) doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.028. e1089-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell ES, et al. Why don't patients and physicians talk about end-of-life care? Barriers to communication for patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and their primary care clinicians. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1690–1696. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kushel MB, Miaskowski C. End-of-life care for homeless patients: "she says she is there to help me in any situation". JAMA. 2006;296:2959–2966. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wissow LS, Belote A, Kramer W, et al. Promoting advance directives among elderly primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:944–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrison RS, Morrison EW, Glickman DF. Physician reluctance to discuss advance directives. An empiric investigation of potential barriers. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2311–2318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]