Abstract

Objective

The effect of risperidone augmentation of citalopram for relapse prevention in older patients with antidepressant-resistant depression was evaluated.

Methods

Patients with major depression aged ≥55 years who had failed at least one adequate trial of an antidepressant received citalopram monotherapy (20–40 mg) for 4 to 6 weeks to confirm nonresponse (<50% reduction in Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAM-D] scores). Those who achieved remission (HAM-D score ≤7or Clinical Global Impressions severity score 1 or 2) after 4 to 6 weeks of open-label risperidone augmentation (0.25–1 mg) then entered a 24-week double-blind maintenance phase during which they received citalopram augmented with risperidone or placebo.

Results

The patients’ mean age was 63.4 ± 7.9 years; 58% were women; 61% had received two or more antidepressants during the current episode; 93 met the criterion for citalopram nonresponse and entered open-label risperidone augmentation. Of the 89 patients who completed risperidone augmentation, 63 achieved symptom resolution and entered the 6-month double-blind maintenance phase: 32 received risperidone augmentation and 31 received placebo augmentation. The median time to relapse (Kaplan-Meier estimates) was 105 days in the risperidone group and 57 days in the placebo group (Wilcoxon χ2: 3.2, df=1, p=0.069). Overall, 18 of 32 (56%) from the risperidone group and 20 of 31 (65%) from the placebo group relapsed. Treatment was well tolerated.

Conclusion

In older patients with resistant depression and poor response to standard treatments, risperidone augmentation resulted in symptom resolution in a substantial number of patients and a nonsignificant delay in time to relapse.

Keywords: Resistant depression, relapse, treatment, risperidone

A recent consensus statement identified mood disorders as a significant health care issue in the elderly that are associated with suffering, functional decline, compromised quality of life, caregiver burden, and increased rates of suicide and service utilization.1 Persistent depression worsens the outcomes of many comorbid medical disorders prevalent in the elderly and increases nonsuicide-related mortality.2,3

Despite recent advances in pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, only one-third of depressed older adults achieve remission and another 20% have partial improvement.4 Drug-resistant depression remains a significant public health problem with profound effects on health care costs.5

A combination of an atypical antipsychotic and an antidepressant appears to be one of the alternatives in the acute treatment of severely depressed patients who have failed to respond to pharmacotherapy.6 Once a patient improves, the clinician is left with the task of determining whether and for how long to continue the antipsychotic agent during continuation and maintenance treatment. In the case of older adults who are at high risk for tardive dyskinesia and other side effects, this decision depends on the advantage that combined treatment offers compared with continuing an antidepressant alone.

To inform this decision, we compared the efficacy and safety of continuation treatment with combined citalopram and risperidone with those of citalopram alone in older depressed patients with drug-resistant depression who improved after acute treatment with the combination of citalopram and risperidone. We focused on risperidone because there is evidence that risperidone augmentation of antidepressants may be an effective acute treatment in unipolar and bipolar major depression resistant to antidepressant drugs.7–9 Furthermore, a nine-month study of mixed-age adults suggests that risperidone may be more effective in relapse prevention than citalopram alone.10 The present analysis uses data from the study of a mixed-age population and focused on patients aged 55 years and older.

METHODS

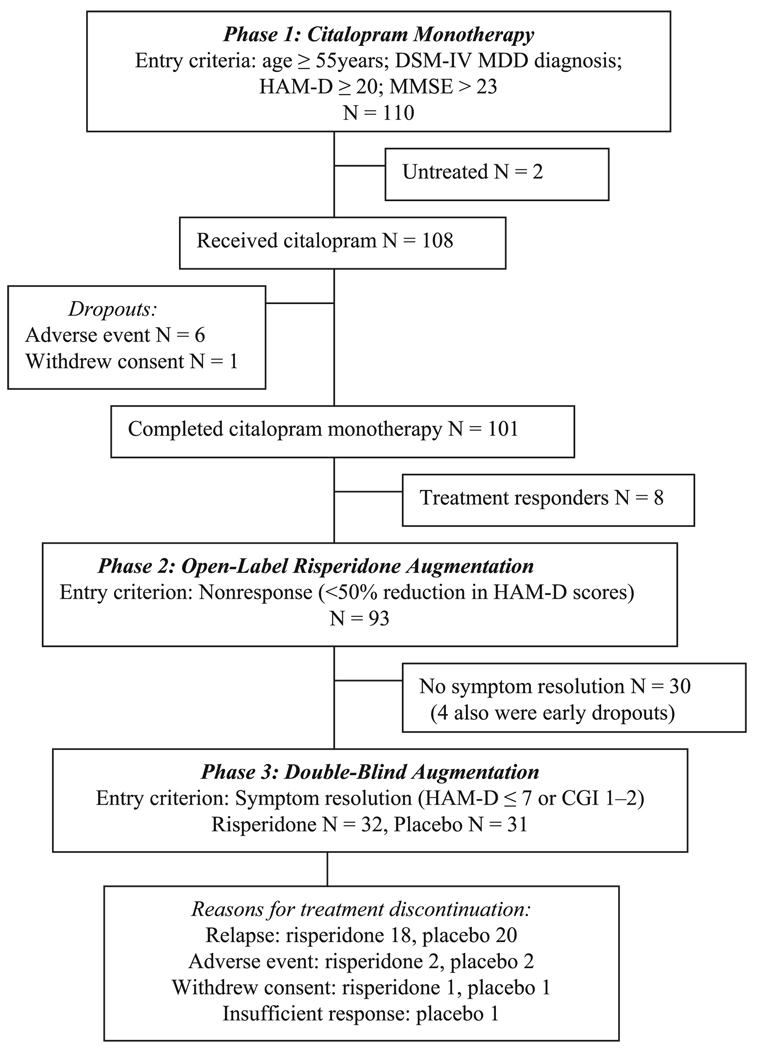

A prospective study of risperidone augmentation in 489 patients aged 18–85 years with treatment-resistant depression was conducted at 57 centers in four countries (Canada, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States) from June 2002 through January 2004. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of each center and all subjects gave written informed consent. The subjects of the present subgroup analyses were the 110 patients aged ≥55 years. The study had three phases: 1) open-label citalopram monotherapy for 4 to 6 weeks to confirm treatment nonresponse; 2) open-label risperidone augmentation of citalopram for 4 to 6 weeks to identify responders to this treatment (i.e., those with symptom resolution) and thus eligible for continuation treatment during the double-blind phase; and 3) double-blind continuation treatment with the combination of risperidone and citalopram or citalopram alone for 24 weeks to assess its efficacy on relapse prevention and safety (Fig. 1). A detailed description of the study has been published elsewhere.10

FIGURE 1.

Study Design and Patient Flow

Patient Selection

The subjects selected for this analysis were inpatients or outpatients, aged ≥55 years, meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder, single or multiple episode, with or without psychotic features, and with a 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) total score ≥20 and a Mini-Mental State Examination score >23. The diagnoses were made at each site by experienced clinicians based on a comprehensive assessment of the patient. Subjects were required to have a history of resistance to standard antidepressant treatment, defined as failure to respond to at least one but no more than three antidepressants during the current episode, administered at adequate doses for a minimum of 6 consecutive weeks (doses of the antide-pressive medication within ranges approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of depression). Patients with comorbid medical illnesses were included except for those with severe and unstable cardiovascular, kidney, liver, or neurological diseases. Patients with dementia and all other DSM-IV axis 1 diagnoses, except generalized anxiety disorder and phobias, were excluded from the study. A complete medical history was obtained from each subject and each received a physical examination and laboratory evaluation. Subjects who were medically healthy and those who had stable medical conditions were eligible to participate in the study.

Phase 1: Acute Citalopram Treatment

The purpose of this open-label phase was to establish resistance to an selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor in patients with a prior history of drug treatment failure during the index episode. Citalopram was started at 20 mg/day and targeted to 40 mg/day. The treatment lasted six weeks or four weeks for patients who were unchanged or worse after four weeks of treatment. Patients nonresponsive to citalopram in phase 1 (<50% reduction in HAM-D scores at endpoint) were included in phase 2. Relapse rates were also identified in patients who were fully nonresponsive to citalopram (<25% reduction in HAM-D scores at endpoint).

Phase 2: Acute Treatment With Citalopram Augmented With Risperidone

Phase 2 consisted of open-label combination treatment of citalopram and risperidone for patients who failed to respond to citalopram during phase 1. Citalopram was kept at the dose received at the endpoint of phase 1. The risperidone augmentation dose was started at 0.25 mg/day and targeted to 0.5 mg/day (0.25–1 mg/day permitted). Its goal was to identify patients who achieved remission (HAM-D score ≤7 or a Clinical Global Impressions [CGI] severity score of 1 or 2) during combination treatment and thus became candidates for continuation treatment offered in phase 3. The duration of phase 2 was four weeks or, at the discretion of the investigator, six weeks for patients who showed clinical improvement but had not yet achieved remission.

Phase 3: Continuation Treatment With a Combination of Citalopram and Risperidone or Citalopram and Placebo

Patients who met criteria for remission after acute combination treatment with citalopram and risperidone during phase 2 were randomly assigned to continue treatment with the same combination or citalopram combined with placebo for 24 weeks. Patients either continued to receive the fixed dose of citalopram and risperidone of phase 2 or citalopram at the dose of phase 2 and placebo (risperidone was discontinued).

Relapse was defined as any of the following occurring at any single time point: 1) substantial clinical deterioration as indicated by a CGI-change score of 6 (much worse) or 7 (very much worse); 2) HAM-D score ≥16; 3) discontinuation due to lack of therapeutic effect; or 4) deliberate self-injury or suicidal intent.

OUTCOME MEASURES

The primary measure of efficacy during the double-blind maintenance study was the time to relapse. Safety evaluations included assessments of movement disorders (Simpson-Angus Scale, Barnes Akathisia Scale, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale) and reports of adverse events. Efficacy measures during the open-label phases included the HAM-D and Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). Assessments were performed at regular intervals throughout all study phases. Details on the schedule of assessments are reported elsewhere.10

RANDOMIZATION AND BLINDING

Randomization sequences were generated by an independent statistician. The randomization for the overall study was noncentralized and stratified by site, age (18–54 and 55–85 years), and presence of psychotic features. Blinded treatment codes were assigned using an automated interactive voice response system. The double-blind integrity was maintained through database lock.

DATA ANALYSIS

The primary analysis of the overall study that included both the older and younger adults was powered to detect between-treatment differences in the entire study sample. The present subanalysis was planned to investigate outcomes in the older group of patients. While age was included as a stratification factor in the randomization scheme for the double-blind phase, the study was not powered to detect between-treatment differences in this subgroup. A post-hoc power calculation was performed for the Kaplan-Meier estimates of the time-to-event (relapse) in the two treatment groups.

Subjects of the efficacy analyses for each phase consisted of all enrolled patients who had received at least one postbaseline efficacy assessment. Subjects of the safety analyses consisted of all enrolled patients who had received at least one dose of any study medication. The last available evaluation for each patient defined the endpoint analyses (last observation carried forward). The baseline for each subsequent phase was the last observation of the preceding phase. Analysis of covariance, with treatment and country as independent factors and respective baseline scores of each scale as covariate, was used to compare treatments on continuous variables. Categorical variables were evaluated using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratifying by country. Time to relapse was compared between groups using Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Two post-hoc analyses were performed: 1) analysis of patients considered fully nonresponsive (<25% improvement) to open-label citalopram monotherapy; and 2) a linear regression model comparing the slopes (improvement rates) in MADRS scores during the open-label citalopram monotherapy and risperidone augmentation phases. In the regression model, the MADRS total score was used as the dependent variable and time (e.g., days 0, 14, 28, 42) was the independent variable for each subject. The slope from this regression was considered an estimate of the subject’s “average” rate of change in MADRS total score per day. Paired t-tests were used to determine the difference in slopes (improvement rates) between two open-label phases and the mean changes from baseline in each phase.

RESULTS

A total of 108 patients entered phase 1 and received at least one dose of open-label citalopram and had one efficacy evaluation (Fig. 1). Phase 1 was completed by 101 patients and 93 met the nonresponse criterion (<50% reduction in HAM-D scores) and received risperidone and citalopram for four to six weeks in phase 2. Of the 93 patients who entered phase 2, 68% (63 of 93) met the criterion for remission. All 63 patients elected to enter the 24-week double-blind maintenance study (phase 3).

The baseline characteristics of the patients who entered phase 3 were similar to those of the 108 patients who entered phase 1 (Table 1). A comorbid disease was identified in 62 of the 63 patients who entered the double-blind maintenance study. These included a musculoskeletal disorder in 53%, cardiovascular in 52%, neurologic in 45%, and gastrointestinal in 40%. Concomitant medications that five or more of these patients were receiving included benzodiazepines and related drugs by 24, acetaminophen by 17, acetylsalicylic acid by 13, ibuprofen or naproxen by 11, ace inhibitors by 10, sulfonamides by 10, statins by 9, proton pump inhibitors by 9, estrogens by 8, antihistamines by 7, thyroid hormones by 7, corticosteroids by 6, and glucocorticoids by 5.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Patient Characteristics

| Phases 1 and 2: Open-Label |

Phase 3: Double-Blind |

p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram Monotherapy |

Risperidone Augmentation |

Risperidone Augmentation |

Placebo Augmentation |

||

| N | 108 | 93 | 32 | 31 | |

| Women (%) | 58 | 56 | 69a | 42 | 0.0320 (CMH = 4.60, df = 1) |

| White (%) | 92 | 95 | 91 | 97 | 0.2469 (CMH = 1.34, df = 1) |

| Age, mean years ± SD | 63.4 ± 7.9 | 63.4 ± 8.0 | 62.3 ± 7.2 | 62.9 ± 7.3 | 0.9649 (F = 0.0, df = 1,58) |

| ≥65 years (%) | 31 | 30 | 28 | 26 | |

| Age at first depressive episode, mean years ± SD |

41.8 ± 17.4 | 41.5 ± 16.9 | 38.1 ± 13.6 | 40.0 ± 17.3 | 0.7236 (F = 0.13, df = 1,58) |

| Duration of current episode, mean years ± SD |

2.1 ± 5.0 | 1.8 ± 3.6 | 1.4 ± 1.9 | 2.4 ± 5.7 | 0.3511 (F = 0.88, df = 1,58) |

| Previous antidepressant use (%) | 0.4511 (CMH = 0.57, df = 1) | ||||

| One drug | 36 | 32 | 31 | 26 | |

| ≥Two drugs | 61 | 65 | 66 | 74 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| Hospitalizations for depression (%) | 0.3477 (CMH = 2.11, df = 2) | ||||

| None | 72 | 71 | 63 | 81 | |

| One | 10 | 12 | 12 | 6 | |

| >One | 18 | 17 | 25 | 13 | |

| Without psychotic features (%) | 96 | 96 | 97 | 90 | 0.1682 (CMH = 1.90, df = 1) |

Notes: Continuous variables were tested in F statistics for differences between treatment groups using a two-way analysis of variance model with treatment and country as factors. Categorical variables were tested for differences between the two treatment groups using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) test in general association statistics adjusting for country.

p <0.05 versus placebo.

Antidepressants received for ≥6 weeks prior to study entry by 5% or more of the 108 patients who entered phase 1 were venlafaxine by 36%, sertraline by 21%, mirtazapine by 20%, fluoxetine by 19%, paroxetine by 19%, bupropion by 10%, amitriptyline by 7%, citalopram by 7%, and trazodone by 5%.

Phases 1 and 2

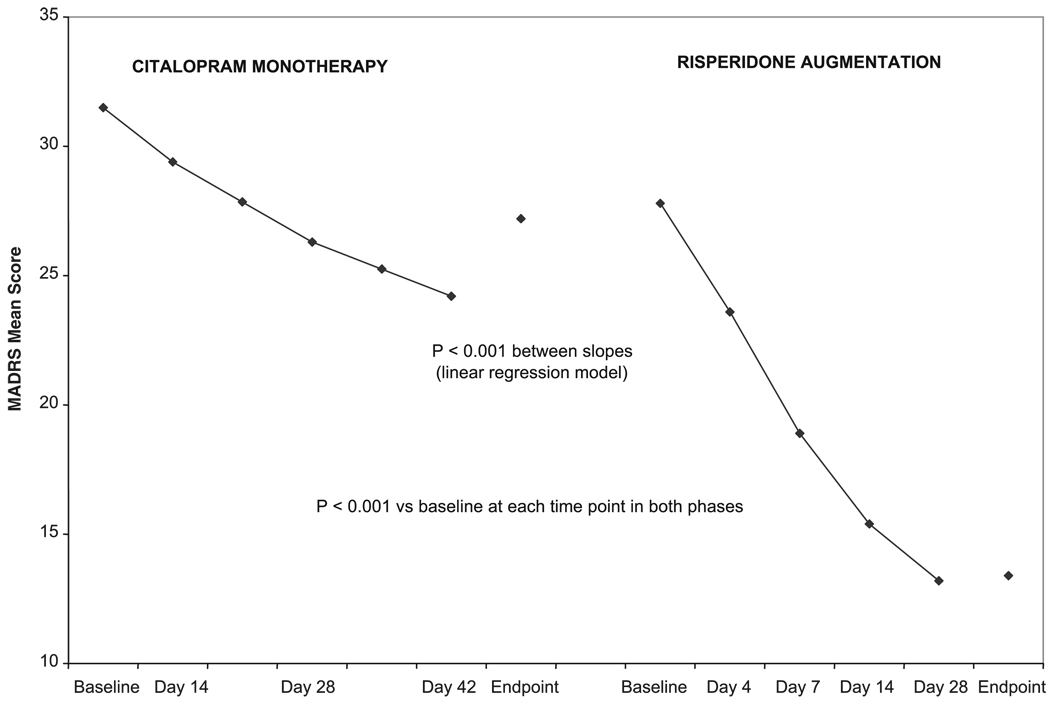

During open-label citalopram monotherapy (phase 1), the mean (±SD) modal dose of citalopram was 34.6 ± 11.5 mg/day. During risperidone augmentation of citalopram (phase 2), the mean modal doses were 0.7 ± 0.3 mg/day of risperidone and 39.3 ± 7.5 mg/day of citalopram. MADRS scores were significantly reduced from baseline at each time point during citalopram monotherapy and risperidone augmentation (Fig. 2). The difference in improvement rates (as measured by the slopes in Fig. 2) observed during the two open-label phases was significant (t = 8.1, df=92, p <0.001). In phase 1, the improvement in MADRS total score was at a mean (±SD) rate of approximately 0.07 ± 0.41 points per day (i.e., 2.9 points over the entire 6 weeks), whereas in phase 2 the improvement was approximately 0.43 ± 0.31 points per day (i.e., 18.1 over the entire 6 weeks).

FIGURE 2.

MADRS Total Scores During Citalopram Monotherapy (N = 108) and Risperidone Augmentation (N=63)

Mean HAM-D and MADRS scores in all study phases are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

HAM-D and MADRS Scores at Baseline and Changes at Endpoint in Phases 1, 2, and 3

| Phases 1 and 2: Open-Label |

Phase 3: Double-Blind |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram Monotherapy |

Risperidone Augmentation |

Risperidone Augmentation |

Placebo Augmentation |

|

| HAM-D | ||||

| Baseline | 25.0 ± 3.4 | 21.6 ± 5.7 | 7.9 ± 3.3 | 7.2 ± 3.1 |

| Endpoint | −4.0 ± 6.5 | −10.7 ± 7.1 | +8.3 ± 7.9 | +6.5 ± 7.5 |

| t value (df) | −6.45 (107) | −14.32 (91) | 5.80 (30) | 4.90 (31) |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| MADRS | ||||

| Baseline | 31.5 ± 5.3 | 27.8 ± 7.0 | 9.2 ± 5.0 | 8.7 ± 5.2 |

| Endpoint | −4.3 ± 8.5 | −14.4 ± 91 | + 12.3 ± 11.4 | +9.8 ± 11.5 |

| t value (df) | −5.23 (107) | −15.19 (91) | 6.00 (30) | 4.78 (31) |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Notes: Data are means ± SD. p Values were calculated from a paired t-test to determine whether the mean change from baseline differs from zero.

Double-Blind Maintenance Study

Of the 63 patients who achieved remission while receiving risperidone and citalopram (phase 2), 32 were randomized to continuation treatment with risperidone and citalopram and 31 to placebo and citalopram. Mean (±SD) modal doses were 0.8 ± 0.3 mg/day of risperidone and 40.0 ± 8.8 mg/day of citalopram in the risperidone/citalopram group and 40.5 ± 6.3 mg/day of citalopram in the placebo/citalopram group.

Attrition

Three patients in the risperidone group and four in the placebo group discontinued treatment for reasons other than relapse. Reasons were adverse events in two patients of each group, consent withdrawal in one patient of each group, and insufficient response in one placebo patient.

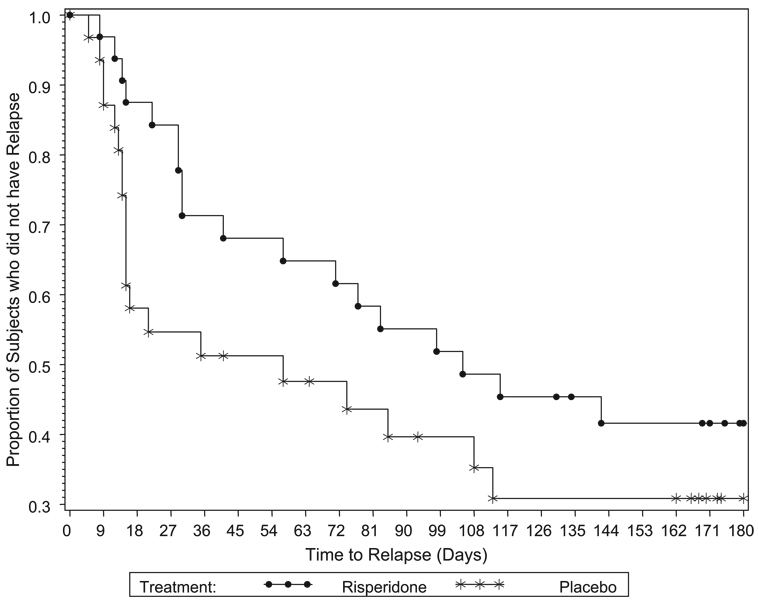

Relapse

The median time to relapse was 105 days in the 32 patients receiving risperidone augmentation and 57 days in the 31 patients receiving placebo augmentation (Wilcoxon χ2:3.2, df=1, p=0.069; Fig. 3). The power to detect between-group differences was only 46%, assuming patients were followed for 180 days and a constant proportion of patients at risk would discontinue at each time point. The relapse rate was 56% (18 of 32) in the risperidone plus citalopram group and 65% (20 of 31) in the placebo plus citalopram group. An analysis of the numbers needed to treat to prevent relapse indicates that, over three to six months, risperidone augmentation would result in one less relapse for approximately every seven to nine patients treated.

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier Analysis of Time to Relapse in Patients Receiving Risperidone or Placebo Augmentation (Wilcoxon P=0.069)

In the 40 patients who were fully nonresponsive to citalopram in phase 1 (<25% reduction in HAM-D scores at endpoint), the median time to relapse was 142 days in the risperidone plus citalopram group and 35 days in the placebo plus citalopram group (Wilcoxon χ2:3.3, df=1, p=0.068). The relapse rate was 53% (8 of 15) in the risperidone plus citalopram group and 68% (17 of 25) in the placebo plus citalopram group.

Adverse Events

The most common adverse events reported in the open-label phases were headache, insomnia, and diarrhea during citalopram monotherapy and dizziness and dry mouth during risperidone augmentation (Table 3). In the double-blind maintenance study, the only adverse event reported in more than two patients of either group was headache (in three risperidone patients). No deaths or cerebrovascular events were reported in these patients.

TABLE 3.

Adverse Events Reported in ≥5% of Patients in Any Group

| Adverse Event | Phases 1 and 2: Open-Label (%) |

Phase 3: Double-Blind (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram Monotherapy |

Risperidone Augmentation |

Placebo Augmentation |

Risperidone Augmentation |

|

| N | 110 | 93 | 31 | 32 |

| Headache | 18.2 | 5.4 | 0 | 9.4 |

| Insomnia | 10.0 | 5.4 | 3.2 | 3.1 |

| Diarrhea | 10.0 | 4.3 | 6.5 | 0 |

| Nausea | 9.1 | 5.4 | 3.2 | 3.1 |

| Somnolence | 8.2 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 3.1 |

| Dizziness | 6.4 | 9.7 | 6.5 | 6.3 |

| Dry mouth | 5.5 | 9.7 | 6.5 | 3.1 |

| URTI | 4.5 | 1.1 | 6.5 | 6.3 |

| Constipation | 2.7 | 5.4 | 6.5 | 3.1 |

| Fatigue | 2.7 | 1.1 | 6.5 | 3.1 |

| Weight increase | 2.7 | 2.2 | 6.5 | 6.3 |

| Pruritus | 2.7 | 2.2 | 0 | 6.3 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 1.8 | 5.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Fall | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 6.3 |

| Anxiety | 0.9 | 5.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Lethargy | 0.9 | 0 | 6.5 | 0 |

| Seasonal allergy | 0.9 | 0 | 6.5 | 0 |

| Appetite increase | 0 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 6.3 |

| Dyspepsia | 0 | 2.2 | 0 | 6.3 |

| Joint stiffness | 0 | 5.4 | ||

| Peripheral swelling | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.3 |

| Sensation of heaviness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.3 |

Mean scores on the Simpson-Angus Scale, Barnes Akathisia Scale, and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale were low at baseline and tended to be further reduced during all three phases (Table 4). There was a mean (±SD) reduction in body weight of 0.3 ± 2.3 kg during citalopram monotherapy (phase 1), an increase in body weight of 0.9 ± 2.1 kg during risperidone augmentation (phase 2), and mean changes of +0.8 ± 3.5 kg in the risperidone group and ‒0.3 ± 2.8 in the placebo group in the maintenance study.

TABLE 4.

Simpson-Angus Scale (SAS), Barnes Akathisia Scale (BAS), and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) Scores at Baseline and Endpoint in Phases 1, 2, and 3

| Phases 1 and 2: Open-Label (%) |

Phase 3: Double-Blind (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram Monotherapy |

Risperidone Augmentation |

Risperidone Augmentation |

Placebo Augmentation |

|

| N | 110 | 93 | 31 | 32 |

| SAS | ||||

| Baseline | 1.2 ± 2.7 | 0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.7 ± 1.4 | 0.1 ± 0.4 |

| Endpoint | 0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.6 ± 1.3 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| t value (df) | −2.36 (df = 106) | −1.40 (df = 92) | −0.57 (df = 28) | −0.70 (df = 28) |

| p value | 0.0201 | 0.1649 | 0.5728 | 0.4892 |

| BAS | ||||

| Baseline | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| Endpoint | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.4 |

| t value (df) | −1.27 (df = 106) | 0.33 (df = 92) | −0.33 (df = 28) | −0.57 (df = 28) |

| p value | 0.2074 | 0.7439 | 0.7452 | 0.5728 |

| AIMS | ||||

| Baseline | 0.7 ± 2.4 | 0.7 ± 2.8 | 0.6 ± 2.0 | 0.4 ± 1.8 |

| Endpoint | 0.7 ± 2.6 | 0.5 ± 1.8 | 0.3 ± 1.3 | 0.1 ± 0.4 |

| t value (df) | 0.19 (df = 106) | −1.37 (df = 92) | −1.00 (df = 28) | −0.87 (df = 28) |

| p value | 0.8520 | 0.1737 | 0.3259 | 0.3892 |

Notes: Data are means ± SD. p Values were calculated from a paired t-test to determine whether the mean change from baseline differs from zero.

DISCUSSION

Older patients with a history of antidepressant-resistant major depression who received continuation treatment with risperidone and citalopram had a median time to relapse of 105 days, compared with 57 days in patients treated with placebo and citalopram. Although the difference was not statistically significant, it may be suggestive. This finding is consistent with the between-treatment difference in time to relapse in the total sample of the original study which comprised 241 adults aged 18 to 87 years.10

Approximately 40% of patients who received continuation treatment with risperidone and citalopram and approximately 30% of the patients who received placebo augmentation remained relapse-free for six months. These may be underestimates since the single time-point criterion for relapse is perhaps too stringent for an illness with a chronically fluctuating course. Additionally, the lack of a stabilization phase in patients who met criteria for remission may have permitted entry into the double-blind phase of patients with an unstable remission. In any event, keeping 40% of depressed older patients with a history of antidepressant resistance relapse-free for 24 weeks (compared with 30% with placebo) may be an improvement over other treatment strategies. The relapse rate in the present study compares favorably with the 76% recurrence rate in 38 elderly patients who received paroxetine or placebo augmented with bupropion, nortriptyline, or lithium reported by Reynolds et al.11

During the acute treatment phase, the severity of depression was reduced during both citalopram monotherapy and the subsequent augmentation of citalopram with risperidone. Symptom resolution was attained by 68% of patients during risperidone augmentation. The citalopram monotherapy phase was too short to establish whether improvement in depression during risperidone augmentation was in response to the addition of risperidone or further exposure to citalopram. However, the mean rate of improvement was approximately 6 times greater during risperidone augmentation than during citalopram monotherapy (Fig. 2), suggesting that the response during risperidone augmentation may not have been simply due to continued citalopram treatment or regression to the mean. These post-hoc findings require prospective confirmation in a controlled study.

The efficacy of risperidone augmentation in the acute and the continuation treatment phases is consistent with clinical studies suggesting that addition of atypical antipsychotics to antidepressants can be beneficial in major depression.12,13 Preclinical reports indicate that risperidone and other atypical antipsychotics modulate the monoaminergic neurotransmitter systems thought to be involved in antidepressant mechanisms.14–16 Thus a potential mechanism of risperidone’s augmentation of citalopram may be increases in norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine activity. The present findings indicate a possible role for risperidone in the large older population of patients with drug-resistant nonpsychotic depression.

A limitation of this subgroup analysis is that only about one-third of the patients were aged ≥65 years. Their characteristics, however, are similar to those of previous studies of older patients with treatment-resistant depression.11,17 The mean duration of illness (2 years) in these patients coupled with the retrospective and prospective history of treatment failure point to the chronic nature of their illness.

Treatment augmentation with risperidone was safe and well tolerated and was not accompanied by movement disorders or significant extrapyramidal signs or changes in body weight. However, the continuation phase of this study was short and cannot establish the long-term safety of risperidone augmentation of antidepressants in older patients. At best, the findings of this study suggest that risperidone added to citalopram is a therapeutic alternative in attempting to stabilize treatment-resistant depression in older adults who are in remission after risperidone augmentation.

CONCLUSION

In this population of older patients with resistant depression and poor response to antidepressants, risperidone augmentation resulted in remission in 68% of patients and a statistically nonsignificant but perhaps clinically meaningful delay in time to relapse. The findings in the older subgroup of patients are consistent with those in the total study sample.10 Risperidone augmentation was well tolerated in these older patients, many of whom had comorbid illnesses and were receiving co-medications. The results suggest that risperidone augmentation is one of the treatment alternatives for these very difficult to treat patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Janssen, LLP.

References

- 1.Charney DS, Reynolds CF, Lewis L, et al. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in late life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:664–672. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F. Talajic: depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;91:999–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keller MB, Boland RJ. Implications of failing to achieve successful long-term maintenance treatment of recurrent unipolar major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:348–360. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fava M, Davidson KG. Definition and epidemiology of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19:179–200. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russell JM, Hawkins K, Ozminkowski RJ, et al. The cost consequences of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:341–347. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thase ME. What role do atypical antipsychotic drugs have in treatment-resistant depression? J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:95–103. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostroff RB, Nelson JC. Risperidone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:256–259. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viner MW, Chen Y, Bakshi I, Kamper P. Low-dose risperidone augmentation of antidepressants in nonpsychotic depressive disorders with suicidal ideation. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:104–106. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200302000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shelton RC, Stahl SM. Risperidone and paroxetine given singly and in combination for bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1715–1719. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rapaport MH, Gharabawi GM, Canuso CM, Mahmoud RA, et al. Effects of risperidone augmentation with treatment-resistant depression inpatients results of open-label treatment followed by double-blind continuation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2505–2513. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reynolds CF, 3d, Dew MA, Pollock BC, et al. Maintenance treatment of major depression in old age. N Engl J Med. 2006;345:1130–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothschild AJ, Williamson DJ, Tohen MF, et al. A double-blind, randomized study of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for major depression with psychotic features. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:363–373. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000130557.08996.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papakostas GI, Petersen TJ, Nierenberg AA, et al. Ziprasidone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for SSRI-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:217–221. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hertel P, Nomikos GG, Svensson TH. Risperidone inhibits 5-hy-droxytryptaminergic neuronal activity in the dorsal raphe nucleus by local release of 5-hydroxyryptamine. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:1639–1646. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blier P, Szabo ST. Potential mechanisms of action of atypical antipsychotic medications in treatment-resistant depression and anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:30–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tremblay P, Blier P. Catecholaminergic strategies for the treatment of major depression. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:149–158. doi: 10.2174/138945006775515464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whyte EM, Basinski J, Mulsant BH, et al. Geriatric depression treatment in nonresponders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1634–1641. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]