Abstract

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), the major cytokine regulator of neutrophilic granulopoiesis, stimulates both the proliferation and differentiation of myeloid precursors. A variety of signaling proteins have been identified as mediators of G-CSF signaling, but understanding of their specific interactions and organization into signaling pathways for particular cellular effects is incomplete. The present study examined the role of the scaffolding protein Grb2-associated binding protein-2 (Gab2) in G-CSF signaling. We found that a chemical inhibitor of Janus kinases inhibited G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation. Transfection with Jak2 antisense and dominant negative constructs also inhibited Gab2 phosphorylation in response to G-CSF. In addition, G-CSF enhanced the association of Jak2 with Gab2. In vitro, activated Jak2 directly phosphorylated specific Gab2 tyrosine residues. Mutagenesis studies revealed that Gab2 tyrosine 643 (Y643) was a major target of Jak2 in vitro, and a key residue for Jak2-dependent phosphorylation in intact cells. Mutation of Gab2 Y643 inhibited G-CSF-stimulated Erk1/2 activation and Shp2 binding to Gab2. Loss of Y643 also inhibited Gab2-mediated G-CSF-stimulated cell proliferation. Together, these results identify a novel signaling pathway involving Jak2-dependent Gab2 phosphorylation leading to Erk1/2 activation and cell proliferation in response to G-CSF.

Keywords: Jak2, Gab2, cytokine signaling, myeloproliferative disorders, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

INTRODUCTION

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is the major cytokine involved in neutrophil production. It has pleiotropic effects on myeloid cells at all stages of granulopoiesis, both stimulating proliferation and promoting differentiation [reviewed in 1,2]. The earliest biochemical changes following ligand binding to the G-CSF receptor (G-CSFR) involve protein tyrosine kinase activation, with rapid phosphorylation of the receptor and several downstream signaling intermediates [1,3]. Because G-CSFR lacks an intrinsic kinase domain, phosphorylation requires activation of non-receptor tyrosine kinases. Members of Src, Syk, Tec, and Janus kinase (Jak) protein tyrosine kinase families have been implicated in G-CSFR signal transduction [4–10]. The role of Jaks in the phosphorylation of signal transduction and activation of transcription proteins (Stats) in particular is well defined [1,5,8,11–14], but the pathways leading to other downstream signaling mediators, potentially including other targets of Jaks, are less clear.

Identifying the molecular interactions of scaffolding proteins involved in G-CSF signaling may help delineate complex downstream signaling pathways and their links to specific cellular responses. Scaffolding proteins, by binding to other signaling intermediates and regulating their localization and protein interactions, can organize and promote specific signaling pathways. Recently, Gab2, a member of the Gab/Dos family of scaffolding proteins was found to participate in G-CSF signaling [15,16].

The interactions of scaffolding proteins with other signaling intermediates are often dependent on phosphorylation status. By activating specific kinases that phosphorylate particular protein binding sites, extracellular signals can regulate Gab2 function [17–19]. Phosphorylation of Gab2 permits recruitment of such key signaling molecules as Shp2 and PI3Kinase [17–20]. Through its various phosphorylation-dependent protein interactions, Gab2 is involved in the regulation of multiple cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, and survival [15,17,21–23]. Identification of the tyrosine kinases responsible for Gab2 phosphorylation is therefore of critical importance in understanding its role in specific signaling systems.

We investigated the possibility of Jak-mediated Gab2 phosphorylation in response to G-CSF. Using mechanistically diverse methods to inhibit Jak activity, we identified G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation that was Jak2-dependent. This phosphorylation required the presence of Gab2 tyrosine 643 (Y643). Disruption of Jak2-dependent, G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation by mutation of Y643 inhibited the interaction of Gab2 with Shp2, the activation of Erk1/2, and the proliferation of cells in response to G-CSF. Our results thus identify a novel G-CSF signaling pathway through Jak2, Gab2 and Erk1/2, that can mediate G-CSF-induced cell proliferation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Glutathione, glutathione agarose and isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Purified recombinant Jak2 bound to agarose and myelin basic protein were from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY), and the Jak2 inhibitor AG490 from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). For Western blotting and immunoprecipitation, we used antibodies to: Jak1, Jak2, and Shp2 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); phosphotyrosine (4G10), phospho-Jak2 and Gab2 from Upstate Biotechnology; phospho-Gab2, phospho-Erk1/2 and Erk2 from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA); Flag epitope tag (Sigma); HA epitope tag (Roche, Indianapolis, IN); and glutathione-S-transferase (GST) from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ).

Cell culture and transfection

The 293 cell line (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was grown in DMEM (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) with 10% fetal calf serum (Gemini Bioproducts, Woodland, CA) and penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen); Fugene6 (Roche) was used for transient transfection. AML-193 cells, gift of Dr. Giovanni Rovera, were maintained in RPMI1640 (Mediatech) with 10% fetal calf serum and penicillin/streptomycin, supplemented with 5 μg/ml insulin (Invitrogen), 5 μg/ml transferrin (Sigma) and 5 ng/ml granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ). Previously characterized DT40GR cells, which express the human G-CSF receptor, were the gift of Dr. Seth Corey [24,25]. DT40GR cells were grown in RPMI1640 with 10% fetal calf serum and penicillin/streptomycin, 5 μM β-mercaptoethanol and 2% chicken serum (Sigma), and transfected by electroporation (Gene Pulser II, Biorad, Hercules, CA) [25]. After 48 hours, stable transfectants were selected with 1 mg/ml G418 for constructs in pcDNA3, or 100 μg/ml Zeocin for constructs in pcDNA3.1Zeo (all from Invitrogen) [25].

Plasmid Constructs and Site-directed Mutagenesis

Antisense (AS) constructs for Jak1 and Jak2, corresponding to nucleotides 172–720 and 1–333 respectively, were prepared by PCR amplification from DT40 cDNA using oligonucleotide primers (forward/reverse): Jak1: 5′-GAGCTGTGCATTGAAGCTG-3′/5′-TCCGAATCCTGGTTAGGAAA-3′, and Jak2 5′-TTGGAATGGCTGTTCTGGAT-3′/5′-CTGCTCTGCCAGTGTCTC-3′. The PCR products were inserted into pcDNA3.1Zeo in reverse orientation. In addition to pooled clones obtained by transfection and antibiotic selection, previously characterized individual clones, gift of Dr. Seth Corey [26], were used in some experiments as noted. Antisense inhibition of Jak expression was confirmed by Western blotting.

Constructs containing point mutations were created using the Quickchange XL mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, LaJolla, CA). The Jak2KE mutant, in which glutamate replaces lysine 882 of human Jak2, was prepared with primers (forward/reverse) 5′-GAGGTGGTCGCTGTGGAAAAACTCCAGCCAGCAC-3′/5′-GTGCTGTGCTGGAGTTTTTCCACAGCGACACCTC-3′. The Jak2KE mutant has been shown to act as a dominant negative inhibitor of Jak2 [27,28]; we confirmed inhibition in cells transduced with our Jak2KE construct by Western blotting for phospho-Jak2. Flag-tagged human Gab2 in pcDNA3.1Zeo and the HA-tagged human G-CSF receptor (G-CSFR) constructs have previously been described [16]. Tyrosine mutants of Flag-tagged human Gab2 cDNA were prepared by site directed mutagenesis with primers (forward/reverse): 5′-CTTCCTGTGAGACCTTCGAGTACCCACAGCG-3′/5′-CGCTGTGGGTACTCGAAGGTCTCACAGGAAG-3′ (Y409F); 5′-ACCAATTCTGAAGACAA CTTTGTGCCCATGAATCCAG-3′/5′-CTGGATTCATGGGCACAAAGTTGTCTTCAGAATTGGT-3′ (Y452F); 5′-TCCCAGAGCGTCTTCATCCCAATGAGCCC-3′/5′-GGGCTCATTGGGATGAAGACG CTCTGGGA-3′ (Y476F); 5′-CGGCAGCGTTGATTTTCTGGCCCTGGACT-3′/5′-AGTCCAGGGCCA GAAAATCAACGCTGC CG-3′ (Y614F); 5′-GATGAGAAGGTGGACTTCGTTCAGGTGGACAAG-3′/5′-CTTGTCCACCTGAACGAAGTCCACCTTCTCATC-3′ (Y643F). To create the GST-Gab2 fusion protein, we amplified a segment of human Gab2 cDNA using primers: 5′-GCTTCTTCCTGTGAGACC-3′/5′-CACTGCTTGGCACCCTT-3′. The product, encoding the C-terminus of Gab2 (amino acids 403–676), was inserted at the EcoRI site in the pGex2T plasmid (Amersham). Tyrosine mutants of GST-Gab2 were prepared as described for full-length Gab2. All constructs were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing.

Cell Stimulation, Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Prior to G-CSF treatment, cells were transferred to serum-free medium to induce quiescence. Unless otherwise specified, cells were stimulated with 50 ng/ml G-CSF (Peprotech) for 5 minutes, then lysed on ice in lysis buffer containing 1% Igepal, 137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate and protease inhibitors (Sigma). Samples were assayed for protein concentration using the Biorad DC Protein assay (Biorad). For analysis by SDS-PAGE, cell lysates were boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. For immunoprecipitation, lysates were incubated overnight with indicated antibodies, then adsorbed with Protein A/G agarose (Santa Cruz). Following four washes with lysis buffer, immunoprecipitates for SDS-PAGE were eluted by boiling 5 minutes in sample buffer. After SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (Millipore, Bedford, MA) for Western blotting. Antibody binding was visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham).

Preparation and Phosphorylation of GST fusion proteins

BL21 bacteria (Amersham) were transformed with GST or GST-Gab2 plasmids. Production of the GST-fusion proteins was induced by treatment with 0.1 mM IPTG for 3 hours at 37°C in a shaking incubator. Cells were lysed by sonication, the fusion protein isolated on glutathione agarose, washed, and eluted with 10 mM glutathione. Protein concentrations in eluates were assayed as described above. GST-Gab2 fusion proteins were phosphorylated in vitro using either active, recombinant, agarose-bound Jak2 (Upstate Biotechnology) or immunoprecipitated Jak2. Jak2 immunoprecipitates, bound to Protein A/G agarose, were washed twice with kinase buffer (50mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10mM MgCl2, 10mM MnCl2), then incubated at 30°C with 5 μg of GST or GST fusion protein in kinase buffer plus 100μM ATP. The reaction was stopped by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The samples were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. For phosphorylation by recombinant Jak2, we used 2.5μl of Jak2-agarose per reaction with addition of 10μCi of [γ-32P]ATP for detection of phosphorylation by autoradiography after SDS-PAGE [29]. A Linotype-Hell TA-3 scanner was used to obtain 24 bit scans of autoradiography films. NIH Image 1.47 software was used for densitometric analysis of the scans at 300 dpi.

In Vitro Assay of Erk Kinase Activity

Erk1/2 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates as described above but not eluted. Immunoprecipitated Erk1/2, bound to Protein A/G agarose, were washed twice in MAP kinase buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol) and then assayed in 20μl of MAP kinase buffer with 0.375 mg/ml myelin basic protein (MBP), 10 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate, and 40 mM ATP including 10μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (6000Ci/mmol, DuPont NEN). After 10 minutes at 30°C (unless otherwise specified), the reaction was terminated by addition of 2x sample buffer and boiling 5 minutes. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and phosphorylated MBP was detected by autoradiography.

Cell Proliferation and Statistical Analysis

Cell proliferation was evaluated by tritiated thymidine incorporation [30,31]. For each condition, triplicate samples at 106 cells/ml were grown in 24-well plates. After 20 hours in test conditions, [3H]thymidine (TRK758, Amersham) was added (5μCi/well). Cells were harvested after a further 6 hours, and thymidine incorporation measured by scintillation counting. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test.

RESULTS

G-CSF stimulates Gab2 phosphorylation dependent on Jak activity in human myeloid cells

We investigated the role of Gab2 in G-CSF signaling in the human myeloid cell line AML-193. G-CSF stimulates proliferation of AML-193 cells and, when combined with retinoic acid, promotes their granulocytic differentiation [32,33]. Treatment of AML-193 cells with G-CSF increased Gab2 tyrosine phosphorylation: Gab2 immunoprecipitated from lysates of G-CSF-treated cells showed strong positivity in anti-phosphotyrosine Western blots (Fig. 1a). Repeat Western blotting with anti-Gab2 confirmed equivalent recovery of Gab2 protein in all samples, while blotting with anti-Shp2 antibodies revealed co-immunoprecipitation of Shp2 with Gab2 in G-CSF-treated cells (Fig. 1a).

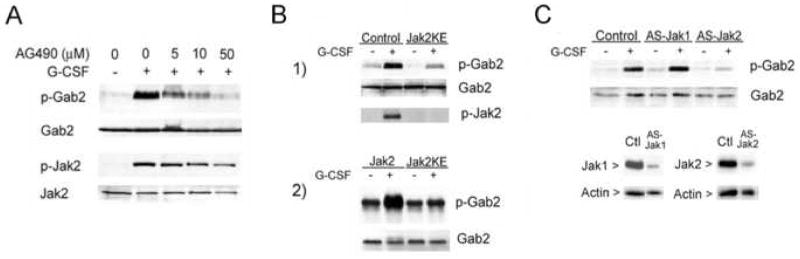

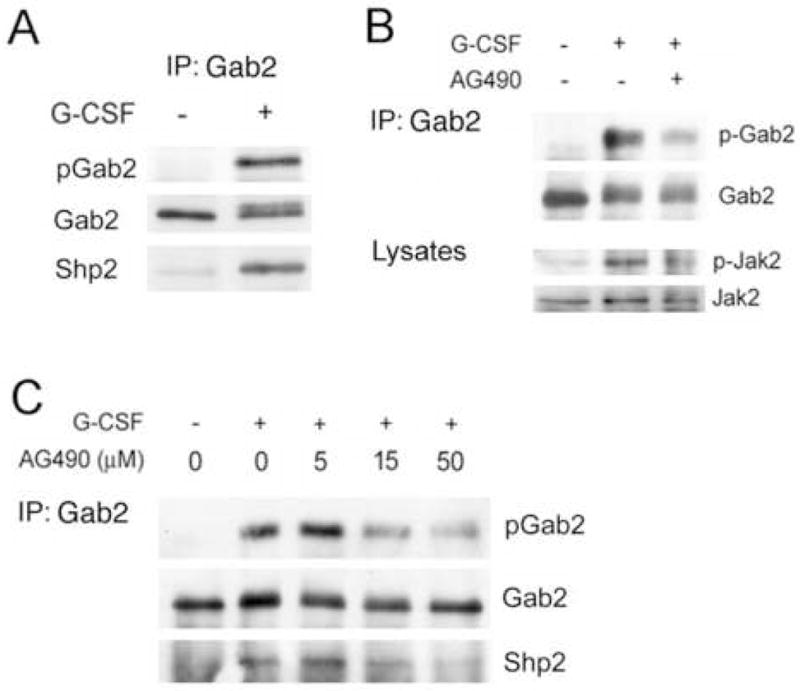

Figure 1. Effect of Jak inhibition on G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 tyrosine phosphorylation and Shp2 binding.

A. G-CSF stimulated the phosphorylation of Gab2 and its association with Shp2 in human myeloid cells. AML-193 cells, after serum deprivation for 15 hours, were treated (+) or not (−) with G-CSF (50 ng/ml) for 5 minutes and lysed. Anti-Gab2 immunoprecipitates from lysates were evaluated by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-phosphotyrosine (top) to identify phosphorylated Gab2 (pGab2). The membranes were then stripped and re-probed with antibodies to Gab2 (middle) and to Shp2 (bottom), to identify total Gab2 protein and co-immunoprecipitated Shp2.

B. AML-193 cells were serum starved for 15 hours, treated (+) or not (−) with AG490 (15 μM), and then stimulated (+) or not (−) with G-CSF (50 ng/ml) for 5 minutes. Anti-Gab2 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phosphotyrosine to detect phospho-Gab2 (p-Gab2). The membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-Gab2 to identify total Gab2 (Gab2). Samples of total lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies to phospho-Jak2 (pJak2) and total Jak2 (Jak2), confirming Jak2 inhibition by AG490. The results indicate that the Jak kinase inhibitor AG490 inhibits G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation.

C. The Jak inhibitor AG490 produced a concentration-dependent reduction in G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation and Shp2 association in human myeloid cells. AML-193 cells were serum starved for 15 hours, treated with the indicated concentration of AG490, and then stimulated (+) or not (−) with 50 ng/ml G-CSF for 5 minutes. Cells were then lysed and half of the lysate used for anti-Gab2 immunoprecipitation. Samples of total lysates were analyzed by Western blotting, as in part B, to confirm Jak2 kinase inhibition (not shown). Anti-Gab2 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with antibodies to phosphotyrosine (top) to identify phosphorylated Gab2 (pGab2), with antibodies to Gab2 (middle) to identify total Gab2 protein, and with antibodies to Shp2 (bottom) to identify co-immunoprecipitated Shp2.

We next investigated the identity of the kinase(s) involved in G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation. Because of the central role of Janus kinases in G-CSF signaling, we examined the effects of the Jak inhibitor AG490. Although not evident in previous studies of Gab2 phosphorylation in murine Ba/F3 cells with a transfected G-CSF receptor, AG490 inhibited G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation in AML-193 human myeloid cells (Fig. 1b). Amongst Janus Kinases, Jak2 shows the greatest sensitivity to AG490 [34–36]. Concurrent inhibition of Jak2 activity was confirmed by Western blots of the cell lysates (Fig. 1b) using antibodies specific for active, phosphorylated Jak2 (anti-phospho-Jak2). AG490 inhibition of G-CSF-dependent Gab2 phosphorylation was concentration dependent (Fig. 1c). Inhibition of Jak2 activity was confirmed by Western blot (data not shown). AG490 also inhibited G-CSF-stimulated Gab2-Shp2 co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1c), suggesting that site(s) of Jak-dependent phosphorylation might include tyrosines 614 and/or 643, the residues in Gab2 previously implicated in Shp2 binding [37–39].

Inhibition of G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation by AG490 pointed to the involvement of Janus kinases, in particular Jak2. But because of possible AG490 effects on other Jaks [34–36], more selective methods of Jak2 inhibition were needed. Unfortunately, targeted disruption of the Jak2 gene in mice is lethal in utero [40,41]. Instead, cells were transfected with selective dominant negative and antisense Jak2 constructs. For these studies, we used DT40GR cells, an established model for analysis of G-CSF-receptor signaling [24,25] more amenable to transfection than AML-193 cells.

G-CSF stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation depends on Jak2 kinase activity

We analyzed the role of Jak2 in G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation in DT40GR cells using three mechanistically distinct approaches to block kinase activity. We first confirmed the effects of AG490: as in AML193 cells, AG490 produced a concentration-dependent inhibition of both Jak2 activation and Gab2 tyrosine phosphorylation in G-CSF-stimulated cells (Fig. 2a). There were minor cell-type-specific differences in sensitivity to AG490, but the overall profile was similar. Such differences are common and may relate to differences in intracellular concentration.

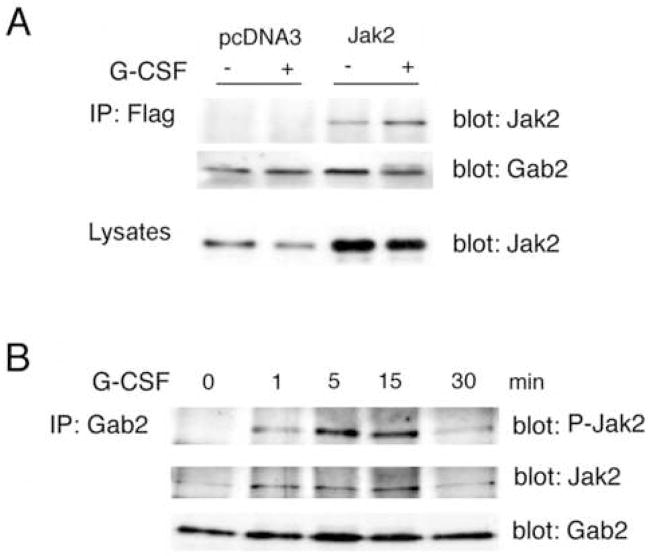

Figure 2. Effect of Jak2 inhibition on G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 tyrosine phosphorylation.

A. Treatment with the Jak inhibitor AG490 resulted in a concentration-dependent reduction in G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation. DT40GR cells were serum starved 15 hours, treated with indicated concentrations of AG490 and stimulated (+) or not (−) with G-CSF. Cell lysates were evaluated by sequential Western blotting with antibodies to phosphoGab2 (p-Gab2), total Gab2 protein, phosphoJak2 (p-Jak2), and total Jak2 protein.

B. G-CSF strongly stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation in cells transfected with wild-type Jak2, but not in cells transfected with the kinase-inactive, dominant negative Jak2KE mutant. Gab2 phosphorylation was evaluated in cells transfected with a kinase-inactive, dominant negative mutant of Jak2 (Jak2KE). (1) DT40GR cells transfected with vector alone (control) or the dominant negative Jak2 mutant (Jak2KE) were stimulated (+) or not (−) with G-CSF. Following SDS-PAGE, cell lysates were evaluated by sequential Western blotting using antibodies to detect phosphorylated Gab2 (p-Gab2, upper panel), total Gab2 protein (middle panel), and phosphorylated Jak2 (p-Jak2, bottom panel). Cells transfected with Jak2KE showed inhibition of both Jak2 and Gab2 phosphorylation in response to G-CSF. (2) Human 293 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding Flag-tagged Gab2, HA-tagged G-CSF receptor, and either wild-type Jak2 or the Jak2KE mutant. Approximately 48 hours after transfection, cells were serum-starved for four hours, stimulated (+) or not (−) with G-CSF for 5 minutes, and lysed. An aliquot of each lysate was analyzed by blotting for the HA epitope tag; this confirmed equivalent G-CSF receptor expression (not shown). Transfected Gab2 was precipitated from the lysates using antibody to the Flag epitope tag. The anti-Flag immunoprecipitates were evaluated by blotting, using antibodies to phosphotyrosine to detect phosphorylated Gab2 (p-Gab2) and anti-Gab2 to evaluate total Gab2 protein.

C. DT40GR cells stably transfected with vector alone (control), antisense Jak1 (ASJak1), or antisense Jak2 (ASJak2) were treated (+) or not (−) with G-CSF for 5 min. Following SDS-PAGE, cell lysates were evaluated by sequential Western blotting for detection of phosphorylated Gab2 (p-Gab2) and then total Gab2 protein (Gab2). G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation was selectively inhibited by inhibition of Jak2 expression. Below are shown results of Western blots for Jak1 (left) or Jak2 (right) in lysates from vector transfected control DT40GR cells (Ctl), Jak1 antisense-transfected DT40GR cells (AS-Jak1), and Jak2 antisense-transfected DT40GR cells (AS-Jak2). These demonstrate the decrease in Jak1 and Jak2 expression by cells transfected with their respective antisense constructs. The results for control and ASJak1 samples are from the same gel, but were separated by additional lanes; only the relevant lanes are shown in order to facilitate comparison. The membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-Actin antibodies as indicated.

We then examined the effects of Jak2KE, a kinase-inactive mutant with a glutamate replacing the conserved lysine 882 in the tyrosine kinase domain; Jak2KE has been shown to act as a specific dominant negative inhibitor of Jak2 [27,28]. Unlike vector-transfected controls, cells transfected with Jak2KE showed inhibition of G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2b). Western blotting with anti-phospho-Jak2 confirmed the absence of activated Jak2 in cells transduced with Jak2KE (Fig. 2b). Similar results were obtained when the putative pathway was reconstituted in 293 cells by transient transfection of HA-tagged G-CSF receptor, Flag-tagged Gab2 and wild-type or mutant Jak2 constructs. Transfected Gab2, immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag epitope tag antibodies, showed G-CSF-stimulated phosphorylation in cells with wild-type Jak2; however, Gab2 from cells co-transfected with the dominant negative mutant showed minimal G-CSF-stimulated phosphorylation (Fig. 2b). Equivalent expression of transfected plasmids in each sample was confirmed by Western blotting of cell lysates, and absence of Jak2 activity by blotting with anti-phospho-Jak2 (data not shown).

DT40GR cells were also tested after transfection with vector (control), antisense Jak1 (AS Jak1) or antisense Jak2 (AS Jak2) plasmid constructs that were previously shown to inhibit expression of the respective kinases [26]. Effective reduction of the relevant Jak protein was confirmed by Western blot (Fig. 2c). In cells with antisense inhibition of Jak2, G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation was markedly diminished (Fig. 2c). No inhibition was evident in cells transfected with Jak1 antisense (Fig. 2c). Although involvement of additional kinases is possible, the consistent inhibition of G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation by mechanistically distinct Jak2 inhibitors strongly supports the involvement of Jak2 in G-CSF-Gab2 signaling.

G-CSF regulates the association of Jak2 and Gab2

Although inhibition of Jak2 reduced G-CSF stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation, whether Jak2 interacted directly with Gab2 was unknown. We tested whether Jak2 binds to Gab2 using co-immunoprecipitation. Gab2 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of transfected 293 cells (prepared as described above) using antibody to its Flag epitope tag. Western blotting of the immunoprecipitates with anti-Jak2 antibodies demonstrated co-immunoprecipitation of Jak2, which appeared to be enhanced by G-CSF (Fig. 3a). Repeat Western blotting with anti-Gab2 confirmed equivalent recovery of Gab2 in the immunoprecipitates (Fig. 3a), and Western blotting of the whole cell lysates confirmed equivalent expression of Jak2 in treated and untreated cells (Fig. 3a). To exclude the possibility that the association seen in 293 cells was an artifact of heterologous expression, we investigated whether endogenous Jak2 and Gab2 associate in DT40GR cells. An anti-Jak2 Western blot of anti-Gab2 immunoprecipitates revealed a weak basal interaction between Jak2 and Gab2 that increased upon treatment with G-CSF (Fig. 3b). G-CSF-stimulated association of Jak2 with Gab2 may provide the propinquity necessary for Jak2 phosphorylation of Gab2.

Figure 3. Role of G-CSF in the association of Jak2 with Gab2.

A. Human 293 cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding Flag-tagged Gab2, the HA-tagged G-CSF receptor, and either vector alone (pcDNA3) or wild-type Jak2 (Jak2). After 48 hours, cells were serum-starved 4 hours, stimulated (+) or not (−) with 50 ng/ml G-CSF and lysed. Equivalent expression of the G-CSF receptor was confirmed by blotting of lysates for the HA epitope tag (not shown). Gab2 was immunoprecipitated from the lysates using anti-Flag antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-Gab2 to demonstrate equivalent expression and recovery of Gab2 (middle), and with anti-Jak2 (top), which revealed co-immunoprecipitation of Jak2 with Gab2 that was enhanced by G-CSF treatment. Equivalent expression of Jak2 in the transfected cells +/− G-CSF was confirmed by blotting whole cell lysates with anti-Jak2 (bottom panel).

B. Serum starved DT40GR cells were treated (+) or not (−) with 50 ng/ml G-CSF for the times indicated, then lysed. Anti-Gab2 immunoprecipitates from cell lysates were evaluated by Western blotting after SDS-PAGE. Equivalent recovery and sample loading was confirmed using anti-Gab2 (bottom panel). Antibodies to Jak2 and phosphorylated Jak2 (middle and upper panels, respectively) revealed co-immunoprecipitation of Jak2 with Gab2. The association between Jak2 with Gab2, minimal under basal conditions, transiently increased after addition of G-CSF.

Jak2 directly phosphorylates Gab2 tyrosine residues in vitro

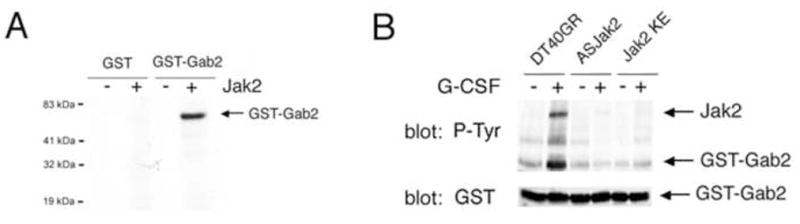

To determine whether specific Gab2 tyrosines could be direct targets for Jak2, we prepared glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins incorporating the distal portion of human Gab2 (amino acids 403–676). This approach circumvents problems with full-length Gab2-GST fusion protein solubility, while retaining tyrosine residues previously implicated in Gab2 interactions with PI3kinase and Shp2 [18,19,37–39]. The resulting fusion protein, GST-Gab2, was used as a substrate for Jak2 in vitro phosphorylation. When incubated with purified, active Jak2 (Upstate Biotechnologies), GST-Gab2 showed strong phosphorylation; Jak2 phosphorylation of GST was not detected (Fig 4a). We also investigated whether GST-Gab2 could be phosphorylated by Jak2 from G-CSF stimulated cells, and whether this phosphorylation was inhibited when cells were co-transfected with antisense or dominant negative Jak2. In vitro phosphorylation was evaluated by Western blotting for phosphotyrosine. As expected, phosphorylation of Jak2 from G-CSF-stimulated control cells was detected (Fig. 4b, upper panel, lane 2). In the same sample, anti-phosphotyrosine Western blotting revealed a phosphoprotein of ~60 kDa, the expected size of the GST-Gab2 fusion protein. However, the in vitro phosphorylation of this protein was not increased by immunoprecipitates from G-CSF-treated cells that were transfected with Jak2 antisense or dominant negative Jak2KE (Fig. 4b). The blot was reprobed with anti-GST to confirm the identity of the ~60 kDa phosphoprotein as GST-Gab2 (Fig. 4b, lower panel). While these studies cannot exclude the involvement of an intervening kinase between Jak2 and Gab2 in vivo, they demonstrate that Jak2 can phosphorylate Gab2 tyrosine residues and therefore may act directly on Gab2.

Figure 4. Activated Jak2 phosphorylates Gab2 tyrosine residues in vitro.

A. GST or GST-Gab2 fusion protein were incubated with (+) or without (−) purified activated Jak2, 15 minutes at 30°C in kinase buffer containing labeled ATP. The proteins in the reactions were separated by SDS-PAGE, and phosphorylated proteins detected by autoradiography. Phosphorylation of GST was not detected with or without Jak2, but incubation of the fusion protein with activated Jak2 resulted in prominent phosphorylation of the ~60 kDa GST-Gab2 protein.

B. Jak2 was immunoprecipitated from G-CSF-stimulated (+) or unstimulated (−) DT40GR cells, and stimulated or unstimulated stable transfectants: antisense Jak2-DT40GR (ASJak2) or dominant negative Jak2-DT40GR (Jak2KE). The anti-Jak2 precipitates were suspended in kinase buffer and Gab2-GST fusion protein added. After 15 minutes at 30°C, phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies to phosphotyrosine (above), and GST (below). Anti-phosphotyrosine showed two major phosphoproteins in samples with Jak2 from G-CSF-treated control cells: Phospho-Jak2 and a ~60 kDa phosphoprotein. The ~60 kDa phosphoprotein was also recognized by anti-GST antibodies, confirming its identity as GST-Gab2. G-CSF-stimulated phosphorylation of Jak2 and the fusion protein was not evident in samples containing anti-Jak2 immunoprecipitates from cells transfected with ASJak2 (lanes 3,4) or Jak2KE (lanes 5,6), which lack active Jak2.

Jak2-mediated G-CSF stimulation of Erk1/2

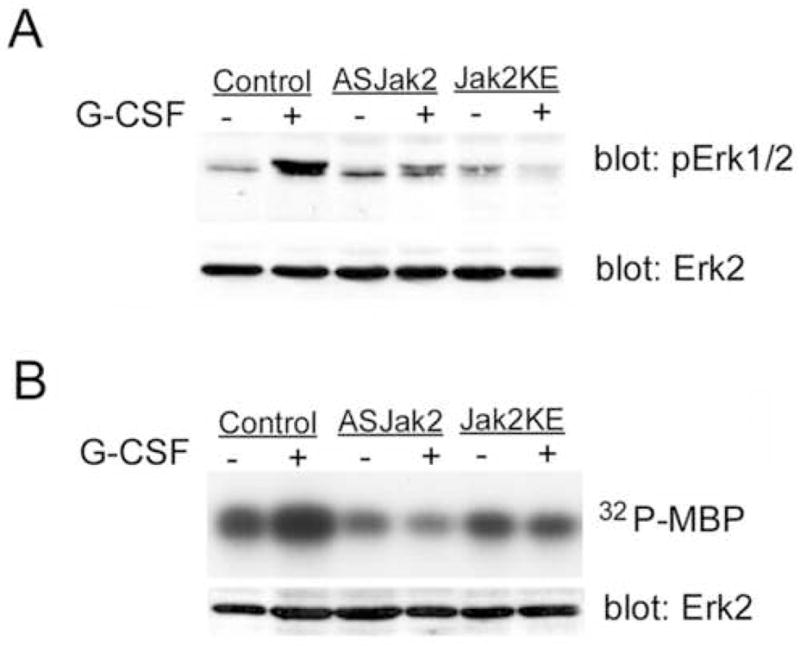

We also examined whether G-CSF-stimulated Erk activation showed dependence on Jak2 activity. Cells were transfected with vector (control), antisense Jak2 (AS Jak2), or the Jak2KE mutant. After treatment with G-CSF, lysates were probed with anti-phosphoErk1/2 antibodies that recognize only activated, phosphorylated Erk1/2 (anti-phosphoErk1/2). Erk1/2 phosphorylation was stimulated by G-CSF in vector-transfected cells, but not in cells transfected with antisense or dominant negative Jak2 (Fig. 5a), implying that G-CSF-stimulated Erk1/2 phosphorylation depended on active Jak2. To confirm that stimulation of Erk catalytic activity by G-CSF involved Jak2, Erk2 was immunoprecipitated from cells transfected with vector, dominant negative or antisense Jak2, each treated or not with G-CSF. Erk activity was then assayed in vitro using radiolabeled ATP and the Erk substrate, myelin basic protein (MBP). Equivalent Erk protein recovery in immunoprecipitates was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 5b, lower panel). G-CSF-stimulated Erk activity was reflected by the increase in MBP phosphorylation with Erk from vector-transduced cells treated with G-CSF (Fig. 5b). In cells lacking active Jak2 because of transfection with antisense Jak2 or Jak2KE, however, G-CSF did not increase Erk phosphorylation of MBP. These results suggest a major role for Jak2 in G-CSF activation of Erk1/2.

Figure 5. G-CSF activation of Erk1/2 requires Jak2 kinase activity.

A. DT40GR cells (control) or DT40GR cells stably transfected with either antisense Jak2 (ASJak2) or dominant negative Jak2KE, were treated (+) or not (−) with G-CSF. Lysates were evaluated by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using antibodies to dually phosphorylated, activated Erk1/2 (pErk1/2) and antibodies to Erk2 protein. The latter (lower panel) demonstrates equivalent amounts of Erk2 in all samples. The upper panel shows the expected phosphorylation of Erk1/2 in response to G-CSF (lane 2) but also reveals (lanes 4 and 6) that G-CSF-dependent phosphorylation was inhibited in cells transduced with Jak2 antisense or the dominant negative Jak2 KE mutant.

B. In vitro kinase activity of Erk from DT40GR cells (control) or from DT40GR cells stably transfected with antisense Jak2 (ASJak2) or dominant negative Jak2 (Jak2KE), treated (+) or not (−) with G-CSF. The Erk substrate myelin basic protein (MBP) and [γ-32P]ATP were added to anti-Erk immunoprecipitates in kinase buffer. After 10 minutes at 30°C, reactions were stopped by boiling in sample buffer. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography to detect phosphorylated MBP (upper panel). Samples from the Erk1/2 immunoprecipitates were also evaluated by Western blotting to confirm equivalent recovery of Erk2 protein in all immunoprecipitates. While Erk from G-CSF-stimulated, wild-type DT40GR cells strongly phosphorylated MBP, G-CSF-stimulation of Erk phosphorylation of MBP was not evident when Erk was immunoprecipitated from cells lacking active Jak2 (ASJak2 and Jak2KE cells).

Jak2-dependent Gab2 phosphorylation and Erk1/2 activation require specific Gab2 tyrosine residues

Gab2 tyrosines 409, 452, 476, 614, and 643 were separately replaced by phenylalanine by site directed mutagenesis yielding epitope-tagged Gab2 tyrosine mutants: Gab2 Y409F, Gab2 Y452F, Gab2 Y476F, Gab2 Y614F, Gab2 Y643F. Tyrosines 452 and 476 are implicated in Gab2 interactions with PI3kinase, and tyrosines 614 and 643 with Gab2 binding of Shp2 [18,19,37–39]; Y409 was mutated as a control. We transfected 293 cells with epitope-tagged wild-type Gab2 (control) or tyrosine mutants of Gab2, with Jak2 and the G-CSF receptor as before. After G-CSF treatment and lysis, half of each lysate was used for Western blots, including confirmation of equivalent expression of transfected proteins (not shown). From the remaining lysate, transfected Gab2 was immunoprecipitated with antibodies to the Flag epitope tag, and phosphorylation evaluated by Western blotting for phosphotyrosine (Fig. 6a). Mutations of Gab2 Y409, Y452, Y476 and Y614 had minimal effects on G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation. However, phosphorylation was substantially inhibited by mutation of Y643, suggesting that Y643 is the major site of G-CSF-dependent Gab2 phosphorylation. To determine whether Gab2 tyrosine mutations affected Erk1/2 activation by G-CSF, cell lysates were re-evaluated by Western blotting with anti-phosphoErk1/2 (Fig. 6a). Again, only mutation of Y643 had a prominent effect: G-CSF failed to stimulate Erk1/2 activation when Y643 was mutated. Re-blotting with anti-Erk2 confirmed uniform protein loading, with equivalent total Erk2 protein in all samples. These results imply that Erk1/2 activation is downstream from G-CSF-stimulated phosphorylation of Gab2 Y643.

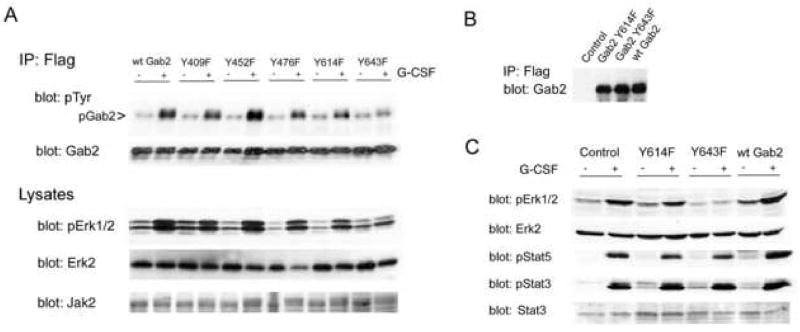

Figure 6. G-CSF-stimulated Jak2-dependent activation of Erk1/2 requires Gab2 tyrosine 643.

A. Human 293 cells were transfected with wild type Gab2 (wtGab2) or a Gab2 tyrosine mutant (identified by the number of the mutated tyrosine: Y409F, Y452F, Y476F, Y614F, Y643F), and with Jak2 and the HA-tagged G-CSF receptor. Cells were stimulated (+) or not (−) with G-CSF for 5 minutes then lysed. Half of each lysate was used for immunoprecipitation of transfected Gab2 with antibodies to its Flag epitope tag. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting for phosphotyrosine and Gab2 (upper panels). G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation appeared to be blocked by mutation of Y643. Samples of each lysate were evaluated by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-Jak2 (bottom) and sequential Western blotting with anti-Erk2 and anti-phosphoErk1/2 antibodies (middle panels), and antibodies to the HA-tag (not shown), with equivalent expression found in all transfectants. G-CSF-stimulated Erk1/2 phosphorylation was found in cells expressing wild-type Gab2 or any of the Gab2 tyrosine mutants except for the Gab2 Y643F mutant. Thus, mutation of Y643 inhibited not only G-CSF stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation but also G-CSF activation of Erk1/2.

B. DT40GR cells were stably transfected with vector alone (control), the Flag-tagged Y614 Gab2 mutant (Gab2 Y614F), the Flag-tagged Y643 Gab2 mutant (Gab2 Y643F) or the Flag-tagged but otherwise unmutated Gab2 (wt Gab2). For each of these cell lines, the transfected protein was immunoprecipitated from lysates using antibody to the Flag epitope tag. The immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-Gab2 antibody; results demonstrate equivalent expression of wild-type and mutant Gab2 proteins by the transduced cell lines, and an absence of signal from the vector-transfected control cells.

C. The DT40GR cells stably transduced with vector (control), the Gab2 Y614 mutant (Y614F), the Gab2 Y643 mutant (Y643F), or epitope-tagged wild-type Gab2 (wt Gab2) were stimulated (+) or not (−) with G-CSF for 5 minutes then lysed. Cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and sequential Western blotting using antibodies to phosphoErk1/2 (pErk1/2) and Erk2 protein (upper panels), phosphoStat5 (pStat5) and phosphoStat3 (pStat3) (lower panels) and Stat3 (data not shown). Mutation of Gab2 Y643 blocked G-CSF-stimulated Erk phosphorylation but had no effect on G-CSF stimulated phosphorylation of Stat3 (pStat3) or Stat5 (pStat5). Equivalent protein loading of all samples is confirmed by the anti-Erk2 immunoblot, which shows equal amounts of Erk2 protein in all samples.

To confirm these results, we evaluated the effects of Gab2 tyrosine mutations on Erk1/2 activation in DT40GR cells. Stable transfectants expressing epitope-tagged Gab2Y643F, Gab2Y614F, or wild-type Gab2 (wtGab2) were selected, and equivalent expression of transfected wild-type and mutant Gab2 confirmed by immunoprecipitation of the transfected proteins using anti-Flag antibodies and then blotting for Gab2 (Fig. 6b). After G-CSF-stimulation, Erk1/2 activation was evaluated by blotting with anti-phosphoErk1/2 (Fig. 6c). Reblotting with anti-Erk2 showed that differences in phosphoErk1/2 signals did not reflect differences in protein loading or total Erk2 protein in treated and untreated samples (Fig. 6c). Consistent with our results from 293 cells, mutation of Gab2 Y643 inhibited G-CSF activation of Erk1/2. These studies also revealed that the increase in Gab2 protein resulting from transfection with wild-type Gab2, itself enhanced G-CSF activation of Erk1/2 in DT40GR cells (Fig. 6c). A similar phenomenon was noted for gp130-dependent Erk1/2 activation with overexpression of Gab1 or Gab2 [15,42]. As expected from the findings in 293 cells, Gab2 Y614F did not block G-CSF stimulated Erk1/2 activation; however, it also failed to reproduce the increase in activity produced by overexpression of wild-type Gab2 (Fig. 6c). This observation suggested that mutation of Y614 might have a partial inhibitory effect on Gab2-mediated, G-CSF-stimulated Erk1/2 activation.

To evaluate the specificity of Erk1/2 inhibition due to mutation of Gab2 Y643, other G-CSF signaling intermediates downstream from Jak2 were tested. Several Stat proteins are phosphorylated, and thereby activated, by Jak kinases in response to G-CSF. There is abundant evidence that this involves a direct interaction between Jaks and Stats that should be unaffected by Gab2 mutations. The lysates examined for Erk1/2 activation were re-probed with antibodies to phospho-Stat3 and phospho-Stat5 (Fig. 6c). G-CSF-stimulated Stat3 and Stat5 phosphorylation were unaffected by the mutation of Gab2 Y643. Equal protein loading was demonstrated by the Western blot for total Erk2 protein (Fig. 6c), and blotting with anti-Stat3 showed no differences in Stat protein between treated and untreated cells (not shown). G-CSF-stimulated Stat3 and Stat5 phosphorylation also differed from Erk1/2 activation in being unaffected by Gab2 overexpression (Fig. 6c). In combination, our results suggest a G-CSF signaling pathway in which Jak2 phosphorylates Gab2 at Y643 thereby permitting interactions with signaling proteins that lead to Erk1/2 activation.

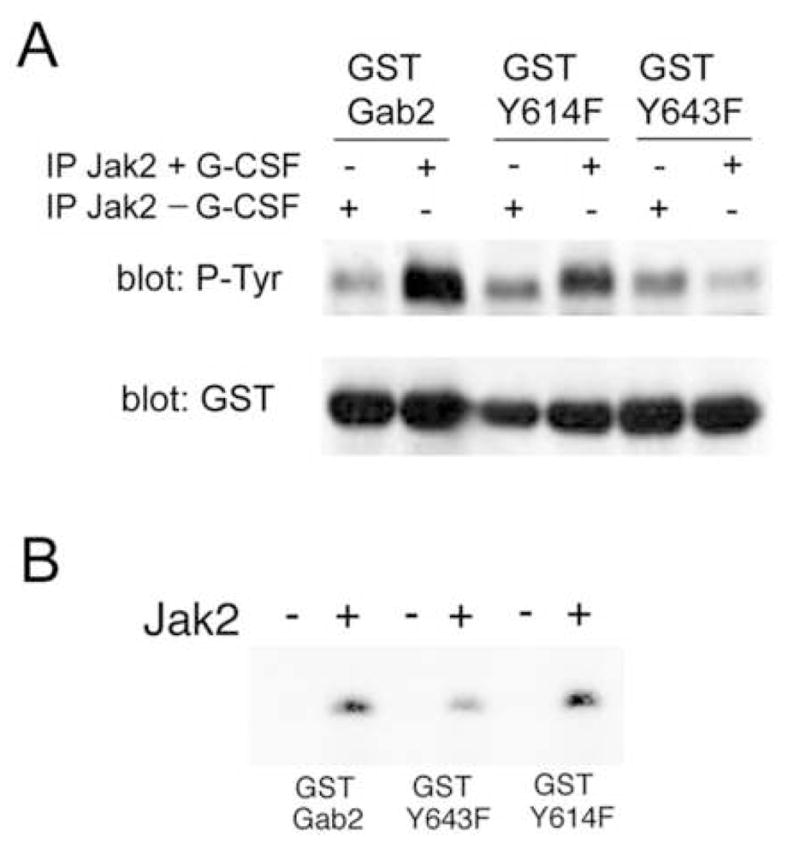

Mutation of Gab2 tyrosine 643 inhibits in vitro phosphorylation by Jak2

We next investigated whether direct in vitro phosphorylation of Gab2 by Jak2 was affected by mutation of Y643. GST-Y614F was created by mutating the tyrosine in GST-Gab2 that corresponds to Y614 in full-length Gab2, and Gab2 Y643F by mutation of the tyrosine corresponding to Y643 in full-length Gab2. GST-Gab2, GST-Y614F and GST-Y643F were incubated with Jak2 that was immunoprecipitated from cells treated or not with G-CSF. Western blotting with anti-phosphotyrosine showed prominent phosphorylation of GST-Gab2 by Jak2 from G-CSF-stimulated cells, but not by Jak2 from unstimulated cells (Fig. 7a, lanes 1 and 2). Mutation of Y643 markedly inhibited in vitro phosphorylation by G-CSF-stimulated Jak2 (Fig. 7a). Mutation of Y614 resulted in a weak, partial reduction of in vitro phosphorylation of the fusion protein by G-CSF-stimulated Jak2 (Fig. 7a). These results implied that Y643 was the major site of GST-Gab2 phosphorylation by Jak2, while Y614 might be a minor site. We further evaluated the phosphorylation of GST fusion proteins using purified active Jak2. Fusion proteins were incubated with Jak2 for 30 minutes to obtain maximal phosphorylation. Under these conditions, additional, non-physiological sites may be phosphorylated. Nevertheless, mutation of Gab2 Y643 significantly decreased phosphorylation by Jak2 (Fig. 7b). Phosphorylation was not abolished, implying that, at least under these conditions in vitro, the fusion protein contains more than one Jak2 phosphorylation site. Densitometry showed that mutation of Y643 decreased phosphorylation by approximately 50% (p < 0.01) after prolonged incubation with active Jak2. With these assay conditions, mutation of Y614 did not significantly decrease phosphorylation.

Figure 7. Mutation of Gab2 tyrosine 643 inhibits its in vitro phosphorylation by Jak2.

A. Jak2 immunoprecipitated from cells stimulated (+) or not (−) with G-CSF was resuspended in kinase buffer, and aliquots were incubated with GST-Gab2 and GST-Gab2 tyrosine mutants with substitution of phenylalanine at residues corresponding to tyrosines 614 (GST Y614F) and 643 (GST Y643F) in full-length Gab2. After incubation at 30°C for 10 minutes, proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies (upper panel) and anti-GST antibodies (lower panel). Anti-phosphotyrosine revealed strong phosphorylation of the unmutated GST-Gab2 by Jak2 from G-CSF-stimulated cells. Phosphorylation of GST Y614F was also increased over background by Jak2 from stimulated cells, though the increase was less marked. GST Y643F, however, showed no increase in phosphorylation when incubated with G-CSF-stimulated Jak2, supporting the identification of Y643 as a major site of Jak2 phosphorylation. The presence of equal amounts of fusion proteins in each lane was confirmed by the anti-GST immunoblot.

B. GST-Gab2, GST Y643F and GST Y614F were incubated for 30 minutes without (−) or with (+) purified, activated Jak2 in kinase buffer containing radiolabeled ATP. Kinase reactions were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. These studies revealed that tyrosine phosphorylation by Jak2 was significantly decreased by mutation of Y643, even after prolonged incubation with active Jak2, suggesting that Gab2 Y643 is a major site of direct phosphorylation by Jak2 in vitro.

Role of Tyrosine 643 in Gab2 protein interactions

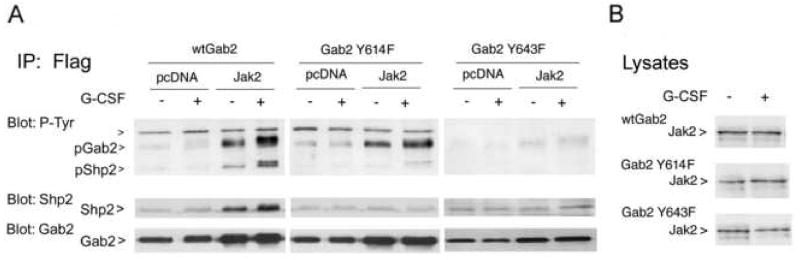

Gab2 Y643 has been implicated in Gab2 binding of Shp2, upstream from Erk1/2 activation [37–39,43–45]. This suggested that Jak2-dependent Gab2 phosphorylation at Y643 might serve to create a Shp2 binding site, thereby linking Jak2 to the activation of Erk1/2. We investigated whether, in G-CSF signaling, mutation of Gab2 Y643 affected interactions with Shp2. Cells were transfected with epitope-tagged wild-type Gab2, Gab2 Y614F, or Gab2 Y643F; with G-CSF receptor and either Jak2 or empty vector. For each condition, cells were tested with and without G-CSF. Transfected Gab2 was immunoprecipitated using antibodies to its Flag epitope tag, and phosphorylation assessed by anti-phosphotyrosine blotting. In the presence of Jak2, Gab2 showed phosphorylation and Shp2 co-immunoprecipitation stimulated by G-CSF (Fig. 8a). Mutation of Gab2 Y643, however, blocked both Gab2 phosphorylation and Shp2 co-immunoprecipitation. Re-blotting with anti-Gab2 showed that these differences were not attributable to variation in total Gab2 protein. There appeared to be at most a mild decrease in G-CSF-stimulation of Gab2 phosphorylation when Y614 was mutated, but Shp2 binding was blocked. The differences in Gab2 phosphorylation did not reflect variation in Jak2 transfection and expression: equivalent Jak2 protein in cells treated or not with G-CSF was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 8b).

Figure 8. G-CSF stimulated association of Shp2 with Gab2 requires Gab2 tyrosines 614 and 643.

A. Cells were cotransfected with vector (pcDNA3) or Jak2, and with Flag-tagged- Gab2 (wtGab2), Gab2 Y614F or Gab2 Y643F. Approximately 48 hours after transfection, the cells were treated (+) or not (−) with G-CSF, then lysed. Anti-Flag antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation of Gab2 from aliquots of lysates, and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by sequential Western blotting with antibodies to phosphotyrosine (P-Tyr, top panel), Shp2 (middle panel) and Gab2 (bottom panel). The positions of Gab2 and Shp2 are indicated, and a co-immunoprecipitated ~110kDa phosphoprotein is marked with an arrowhead. G-CSF stimulated the co-immunoprecipitation of Shp2 with Gab2 in the presence of Jak2. Shp2 association with Gab2 was inhibited by mutation of either Y614 or Y643; G-CSF stimulated phosphorylation of Gab2 was strongly inhibited by mutation of Y643.

B. Lysates from the cells transfected with Jak2 and Gab2 constructs were further analyzed by Western blotting using anti-Jak2, to confirm equivalent Jak2 expression in stimulated and unstimulated cells.

Gab2-dependent G-CSF effects on cell proliferation are inhibited by mutation of Gab2 Y643

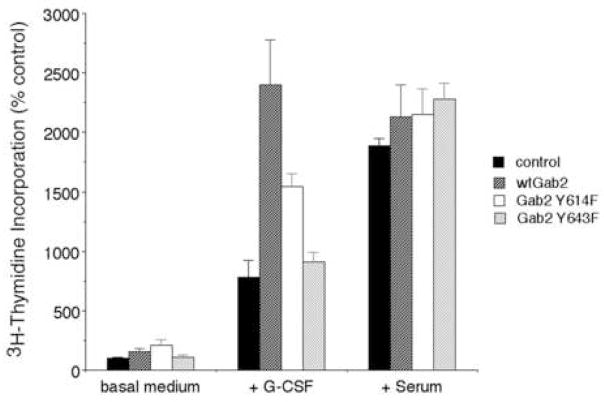

Both Jak2 and Erk1/2 have been implicated in G-CSF effects on cell proliferation [7,12,46–49]. To evaluate the potential function of the proposed G-CSFR–Jak2–Gab2–Erk1/2 pathway, we tested whether disrupting this pathway by mutating Gab2 tyrosine residues altered cell proliferation. We measured tritiated thymidine incorporation by DT40GR cells stably transfected wild-type Gab2, Gab2 Y614F or Gab2 Y643F, showing equivalent expression of transfected protein (Fig. 6b), and by a vector-transfected control. In basal medium, there was minimal proliferation of any of the cells (Fig. 9). Addition of G-CSF increased the proliferation of the vector-transfected controls, although the increase in their proliferation was less than that produced by serum. In contrast, cells transfected with wild-type Gab2 showed G-CSF-stimulated proliferation comparable to that of serum stimulation (Fig. 9). The greater proliferation of cells when transfected wild-type Gab2 parallels the increase in G-CSF-stimulated Erk1/2 activation (Fig. 6c). Mutation of Gab2 Y643 inhibited the Gab2-dependent increase in G-CSF-stimulated cell proliferation (Fig. 9). Residual G-CSF-stimulated proliferation in cells expressing Gab2 Y643 may reflect signaling through endogenous wild type Gab2, as it is equivalent to the proliferation of vector-transfected controls, or it may be due to activation of parallel pathways, independent of Gab2, that have previously been implicated in G-CSF-stimulated proliferation [1–3]. Mutation of Y614 produced an intermediate effect: compared to controls, cells expressing Gab2 Y614F showed increased proliferation, but the increase was significantly less than that produced by transfected wild-type Gab2 (Fig. 9), possibly reflecting the partial inhibition of Erk1/2 activation observed with Gab2 Y614F.

Figure 9. Gab2-dependent G-CSF-stimulated cell proliferation is inhibited by mutation of Gab2 tyrosine 643.

DT40GR cells stably transfected with vector alone (control), Flag-tagged Gab2 (wtGab2), the Y614F mutant (Gab2 Y614F), or the Y643F mutant (Gab2 Y643F), were cultured in triplicate in basal medium, or basal medium plus either G-CSF (+ G-CSF) or added serum (+ serum). The cells were pulsed with tritiated thymidine to assess new DNA synthesis; incorporation of radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Compared to cells transfected with wild-type Gab2, G-CSF stimulated proliferation of cells expressing Gab2 Y643F was markedly inhibited (p < 0.01). Cells expressing Gab2 Y614F showed a smaller decrease in G-CSF-stimulated tritiated thymidine incorporation (p = 0.04). The presence of wild-type Gab2, or either of the Gab2 mutants, had no significant effect on serum-stimulated proliferation.

DISCUSSION

Ligand binding to the G-CSF receptor initiates an intricate network of signaling protein interactions that culminate in complex cellular responses. One of the earliest events in G-CSF signal transduction is the activation of Janus kinases [1]. But apart from the Stat proteins, the identities and roles of Jak substrates in G-CSF signaling remain unclear. We now report a novel mechanism for Jak-mediated signaling from the G-CSF receptor, a pathway linking Jak2 through Gab2 to Erk1/2, transmitting a signal for cell proliferation.

Although multiple kinases are known to phosphorylate Gab2 [17–19], few studies have examined the role of Jaks. In experiments with a truncated gp130 receptor mutant that could activate only Jaks, Gab1 phosphorylation was identified [42]. Furthermore, IL-2 can stimulate Jak-dependent Gab2 phosphorylation, but the kinase involved, Jak3, is not a known component of G-CSF signaling pathways [1,14,50]. The signaling mechanisms of two leukemic fusion proteins, however, provide precedents for a specific link between Jak2 and Gab2. The Tel-Jak2 fusion protein binds Gab2 [51]; this might represent a direct interaction between Jak2 and Gab2 like that suggested by our co-immunoprecipitation results. In addition, Jak2-dependent Gab2 phosphorylation is detected in studies of signaling events downstream from the Bcr-Abl fusion protein, though whether Jak2 directly phosphorylated Gab2 was not determined [52].

In our studies of G-CSF signaling in human myeloid AML-193 cells, we found that G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation was inhibited by AG490. AG490 was originally identified as a Jak2-inhibitor, but, in common with many chemical inhibitors, its specificity is imperfect with some inhibition of other Janus kinases detected [34–36]. To confirm the specific involvement of Jak2 in G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation, we examined the effects of dominant negative Jak2 and Jak2 antisense constructs; these also inhibited G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation. While it remains possible that one of these Jak2 inhibitors might alter Gab2 phosphorylation through a non-specific mechanism, in combination our results imply that it is their common effect - inhibition of Jak2 activity - that reduces Gab2 phosphorylation.

While our results implicate Jak2 in G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation they do not exclude the involvement of other kinases. For example, it remains possible that Jak2-dependent Gab2 phosphorylation is indirect, with Jak2 activating another kinase that in turn phosphorylates Gab2. However, the evidence of Jak2 binding to Gab2, as well as the phosphorylation of Gab2 tyrosines by purified Jak2 in vitro, supports direct phosphorylation of Gab2 by Jak2 in response to G-CSF.

In some experiments, however, we did detect residual, partial, Gab2 phosphorylation despite the presence of Jak inhibitors. While this might merely reflect incomplete suppression of Jak2 activity, it is also compatible with the existence of more than one Gab2 kinase downstream from G-CSF. In studies using the murine Ba/F3 cell line, Zhu et al. identified G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation that was inhibited by treatment with Src-family kinase (SFK) inhibitors [16]. This phosphorylation appeared to be mediated by Lyn, but whether Lyn acted directly on Gab2 was not determined, and the sites of Lyn-dependent G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation were not identified. It is possible that Jak2 and Lyn act in series. (Indeed, the respective roles and possible interdependence of Jaks and Lyn in G-CSF signaling have yet to be fully clarified.) Alternatively, Jak2 and SFK may act in parallel to phosphorylate distinct sites in Gab2 in response to G-CSF. There are precedents for the phosphorylation of Gab2 by more than one kinase in a single signaling system; for example, both Fms tyrosine kinase and Src family kinases phosphorylate Gab2 in response to CSF-1 [53,54].

The differing downstream effects we observed for Jak2- versus Lyn-dependent Gab2 phosphorylation favor a model in which Jak2 and Lyn act in parallel, in distinct signaling pathways. We identified G-CSF-stimulated Erk1/2 activation and cell proliferation dependent on Jak2-mediated Gab2 phosphorylation. In contrast, in Ba/F3 cells with SFK-dependent Gab2 phosphorylation, G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation was associated with Akt activation and differentiation [16]. Whether the predominant Gab2 kinase is a Jak or Src family member may be cell type specific, reflecting characteristic differences in kinase expression. In G-CSF signaling, the balance between alternative Gab2 kinases may vary with the maturation status of the cell, with Jak2 predominating in early precursors -increasing their proliferation - and Src family kinases predominating later, during differentiation. This formulation is consistent with the known downregulation of G-CSF-stimulated Jak2 activity during granulocytic differentiation [13,55]. Gab2 may thus be a common substrate for several G-CSF-activated kinases that target Gab2 to different signaling protein interactions with different functional consequences.

Our results identify Gab2 Y643 as a probable site of G-CSF-activated Jak2 phosphorylation: Jak2-dependent G-CSF-stimulated Gab2 phosphorylation was inhibited when Gab2 Y643 was replaced by phenylalanine. Mutation of Y643 also reduced in vitro phosphorylation by purified Jak2. Consistent with direct Jak2 phosphorylation at this site, Gab2 Y643 lies within a consensus sequence (YXX[L/V/I]) for phosphorylation by Jak2 [56]. Though not definitive, the sequence at Y643 also argues against phosphorylation of this residue by other kinases with different substrate specificities. In addition, it remains possible that mutation of Gab2 Y643 causes conformational changes that indirectly inhibit phosphorylation at other tyrosine residue(s).

Gab2 Y643 is critical for the binding and activation of Shp2 by Gab2 [37–39]. Consistent with previous reports, we found that mutation of Gab2 Y643 blocked co-immunoprecipitation of Shp2 with Gab2 [37,39]. The Y643 mutation also inhibited Erk activation by G-CSF. Since Shp2 activates the Ras-Erk1/2 pathway in other signaling systems [15,42,57–59], our results suggest a pathway from G-CSFR to Erk1/2 through Jak2, Gab2 and Shp2.

Previous studies of G-CSF signaling identified a pathway from G-CSFR to Erk1/2 requiring G-CSFR Y764 [3,47,60,61]: when phosphorylated, G-CSFR Y764 binds adaptor proteins (e.g. Shc, Grb2) through which the Ras-Erk1/2 pathway is activated [62–66]. But unlike the related kinase Erk5, which shows an absolute requirement for the tyrosine-containing C-terminal domain of G-CSFR [67], Erk1/2 activation by G-CSF, though diminished, does still occur in the absence of G-CSFR Y764, and even in the absence of all of the C-terminal tyrosines of G-CSFR [7,46,47,49,60,66–69]. The mechanism for G-CSFR tyrosine-independent Erk1/2 activation is not clear. Involvement of Jak2 is plausible, since G-CSF can activate Jak2 in the absence of the receptor’s C-terminal tyrosine-containing domain [7,12,49]. The pathway from Jak2 to Erk1/2 through Gab2, suggested by our results, might represent the mechanism for receptor tyrosine- independent activation of Erk1/2 by G-CSF.

Our results further suggest that the pathway from G-CSFR through Gab2 mediates a proliferation signal: G-CSF-stimulated proliferation was inhibited when the Jak2-Gab2-Shp2-Erk pathway was disrupted by mutation of the putative Jak2 phosphorylation site in Gab2. Jak2 and Erk have both been implicated in proliferation stimulated not only by wild-type G-CSFR but also by the truncated G-CSFR mutants found in some leukemias [1,3,7,11,46,49,65,69]. Gab2, which appears to link Jak2 with Erk and proliferation, might thus be involved in transmitting the proliferation signal from leukemia-associated G-CSF receptor mutants [1,70,71]. Jak2 phosphorylation of Gab2 may also be involved in the pathogenesis of chronic myeloproliferative disorders resulting from activating mutations of Jak2 that lead to excessive cell proliferation [72].

Mutation of Gab2 Y614 and Y643 produced similar inhibition of Shp2 binding, but their effects on G-CSF-stimulated Erk1/2 activation differed: depending on cell type, mutation of Gab2 Y614 produced moderate or no inhibition of Erk1/2, but mutation of Y643 resulted in marked inhibition. The results for cell proliferation paralleled the findings for Erk1/2 activation: mutation of Gab2 Y614 had a partial effect, whereas mutation of Y643 produced marked inhibition. While our results support the hypothesis that activation of Erk1/2 mediates Gab2-dependent G-CSF-stimulated proliferation, the difference between the inhibition of Shp2 binding and Erk1/2 activation suggests that Gab2 may modulate Erk1/2 activation through additional mechanisms, independent of Shp2 but requiring Gab2 Y643. These might involve Gab2 interactions with proteins of other Erk1/2 activation pathways, such as Grb2. Moreover, our co-immunoprecipitation studies (Fig. 7) revealed that mutations of Y643 also blocked a constitutive association between Gab2 and an unknown ~110kDa phosphoprotein. Future studies will examine this and other possible intermediates in G-CSF-Gab2 signaling.

In summary, our findings suggest that the transduction of G-CSF proliferative signals involves Jak2-dependent Gab2 phosphorylation resulting in Shp2-mediated Erk1/2 activation. This observation is consistent with the established roles of Jaks and Erks in G-CSF stimulated proliferation, including that mediated by G-CSF receptors lacking cytoplasmic domain tyrosines. Our results now place Gab2 and Jak2 upstream from Erk1/2 in this G-CSF signaling pathway.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant K08 AR053566. We thank Dr. Harry Blair for reading the manuscript, Dr. Seth Corey for DT40GR cells and antisense constructs, and Dr. Giovanni Rovera for AML-193 cells.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Touw IP, van de Geijn GJ. Front Biosci. 2007;12:800–815. doi: 10.2741/2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward AC, Loeb DM, Soede-Bobok AA, Touw IP, Friedman AD. Leukemia. 2000;14:973–990. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kendrick TS, Bogoyevitch MA. Front Biosci. 2007;12:591–607. doi: 10.2741/2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corey SJ, Burkhardt AL, Bolen JB, Geahlen RL, Tkatch LS, Tweardy DJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4683–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholson SE, Oates AC, Harpur AG, Ziemiecki A, Wilks AF, Layton JE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2985–2988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuda T, Takahashi-Tezuka M, Fukada T, Okuyama Y, Fujitani Y, Tsukada S, Mano H, Hirai H, Witte ON, Hirano T. Blood. 1995;85:627–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicholson SE, Novak U, Ziegler SF, Layton JE. Blood. 1995;86:3698–3704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimoda K, Feng J, Murakami H, Nagata S, Watling D, Rogers NC, Stark GR, Kerr IM, Ihle JN. Blood. 1997;90:597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward AC, Monkhouse JL, Csar XF, Touw IP, Bello PA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:117–123. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ekman N, Arighi E, Rajantie I, Saharinen P, Ristimaki A, Silvennoinen O, Alitalo K. Oncogene. 2000;19:4151–4158. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barge RM, de Koning JP, Pouwels K, Dong F, Lowerberg B, Touw IP. Blood. 1996;87:2148–2153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian SS, Tapley P, Sincich C, Stein RB, Rosen J, Lamb P. Blood. 1996;88:4435–4444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avalos BR, Parker JM, Ware DA, Hunter MG, Sibert KA, Druker BJ. Exp Hematol. 1997;25:160–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward AC, Touw I, Yoshimura A. Blood. 2000;95:19–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishida K, Yoshida Y, Itoh M, Fukada T, Ohtani T, Shirogane T, Atsumi T, Takahashi-Tezuka M, Ishihara K, Hibi M, Hirano T. Blood. 1999;93:1809–1816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu QS, Robinson LJ, Roginskaya V, Corey SJ. Blood. 2004;103:3305–3312. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu H, Neel BG. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:122–130. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chakraborty A, Dyer KF, Cascio M, Mietzner TA, Tweardy DJ. Blood. 1999;93:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishida K, Hirano T. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:1029–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu H, Pratt JC, Burakoff SJ, Neel BJ. Molec Cell. 1998;2:729–740. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80288-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wada T, Najashima T, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Gasser J, Hara H, Schett G, Penninger JM. Nature Med. 2005;11:394–399. doi: 10.1038/nm1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baychelier F, Nardeux PC, Cajean-Feroldi C, Ermonval M, Guymarho J, Tovey MG, Eid P. Cell Signal. 2007;19:2080–2087. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu WM, Hawley TS, Hawley RG, Qu CK. Blood. 2002:2351–2359. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corey SJ, Dombrosky-Ferlan PM, Zuo S, Krohn E, Donnenberg AD, Zorich P, Romero G, Takata M, Kurosaki T. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3230–3235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Rudert WA, Loutaev I, Roginskaya V, Corey SJ. Oncogene. 2002;21:5346–5355. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Kurosaki T, Corey SJ. Oncogene. 2007;26:2851–2859. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Briscoe J, Rogers NC, Witthuhn BA, Watling D, Harpur AG, Wilks AF, Stark GR, Ihle JN, Kerr IM. EMBO J. 1996;15:799–809. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohlhuber F, Rogers NC, Watling D, Feng J, Guschin D, Briscoe J, Witthuhn BA, Kotenko SV, Pestka S, Stark GR, Ihle JN, Kerr IM. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;17:695–706. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanke JH, Gardner JP, Dow RL, Changelian PS, Brissette WH, Weringer EJ, Pollok BA, Connelly PA. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:695–701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu T, Lobie PE. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2103–2114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson LJ, Xue J, Corey SJ. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lange B, Valtieri M, Santoli D, Caracciolo D, Mavilio F, Gemperlein I, Griffin C, Emanuel B, Finan J, Nowell P, Rovera G. Blood. 1987;70:192–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valtieri M, Boccoli G, Testa U, Barletta C, Peschle C. Blood. 1991;77:1804–1812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meydan N, Grunberger T, Dadi H, Shahar M, Arpaia E, Lapidot Z, Leeder JS, Freedman M, Cohen A, Gazit A, Levitzki A, Roifman CM. Nature. 1996;379:645–648. doi: 10.1038/379645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang LH, Kirken RA, Erwin RA, Yu CR, Farrar WL. J Immunol. 1999;162:3897–3904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Turkson J, Carter-Su C, Smithgall T, Levitzki A, Kraker A, Krolewski JJ, Medveczky P, Jove PR. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24935–24944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnaud M, Mzali R, Gesbert F, Crouin C, Guenzi C, Vermot-Desroches C, Wijdenes J, Courtois G, Bernard O, Bertoglio J. Biochem J. 2004;382:545–556. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crouin C, Arnaud M, Gesbert F, Camonis J, Bertoglio J. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:148–153. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamasaki S, Nishida K, Hibi M, Sakuma M, Shiina R, Takeuchi A, Ohnishi H, Hirano T, Saito T. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45175–45183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neubauer H, Cumano A, Mueller M, Wu H, Huffstadt U, Pfeffer K. Cell. 1998;93:397–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parganas E, Wang D, Stravopodis D, Topham DJ, Marine JC, Teglund S, Vanin EF, Bodner S, Colamonici OR, van Deursen JM, Grosveld G, Ihle JN. Cell. 1998;93:385–395. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi-Tezuka M, Yoshida Y, Fukada T, Ohtani T, Yamanaka Y, Nishida K, Nakajima K, Hibi M, Hirano T. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4109–4117. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi ZQ, Yu DH, Park M, Marshall M, Feng GS. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1526–1536. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1526-1536.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montagner A, Yart A, Dance M, Perret B, Salles JP, Raynal P. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5350–5360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang W, Klaman LD, Chen B, Araki T, Harada H, Thomas SM, George EL, Neel BG. Dev Cell. 2006;10:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bashey A, Healy L, Marshall CJ. Blood. 1994;83:949–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rausch O, Marshall CJ. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4096–4105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baumann MA, Paul CC, Lemley-Gillespie S, Oyster M, Gomez-Cambronero J. Am J Hematol. 2001;68:99–105. doi: 10.1002/ajh.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koay DC, Nguyen T, Sartorelli AC. Cell Signal. 2002;14:239–247. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gadina M, Sudarshan C, Visconti R, Zhou YJ, Gu H, Neel BG, O’Shea JJ. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26959–26966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nguyen MHH, Ho JMY, Beattie BK, Barber DL. J Biol Chem. 2001;35:32704–32713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Samanta AK, Lin H, Sun T, Kantarjian H, Arlinghaus RB. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6468–6472. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee AWM, States DJ. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6779–6798. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6779-6798.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Y, Jenkins B, Shin JL, Rohrschneider LR. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3047–3056. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.9.3047-3056.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shimoda K, Iwasaki H, Okamura S, Ohno Y, Kubota A, Arima F, Otsuka T, Niho Y. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:922–928. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Argetsinger LS, Kouadio J-LK, Steen H, Stensballe HA, Jensen ON, Carter-Su C. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4955–4967. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.4955-4967.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neel BG, Gu H, Pao L. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:284–293. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salmond RJ, Alexander DR. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dance M, Montagner A, Salles JP, Yart A, Raynal P. Cell Signal. 2008;20:453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akbarzedah S, Ward AC, McPhee DO, Alexander WS, Lieschke GJ, Layton JE. Blood. 2002;99:879–887. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hermans MH, van de Geijn GJ, Antonissen C, Gits J, van Leeuwen D, Ward AC, Touw IP. Blood. 2003;101:2584–2590. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Koning JP, Schelen AM, Dong F, van Buitenen C, Burgering BM, Bos JL, Lowenberg B, Touw IP. Blood. 1996;87:132–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de Koning JP, Soede-Bobok AA, Schelen AM, Smith L, van Leeuwen D, Santini V, Burgering BM, Bos JL, Lowenberg B, Touw IP. Blood. 1998;91:1924–1933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ward AC, Monkhouse JL, Hamilton JA, Csar XF. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1448:70–76. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ward AC, Smith L, de Koning JP, van Aesch Y, Touw IP. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14956–14962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kendrick TS, Lipscombe RJ, Rausch O, Nicholson SE, Layton JE, Goldie-Cregan LC, Bogoyevitch MA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:326–340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dong F, Gutkind JS, Larner AC. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10811–10816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rausch O, Marshall CJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1170–1179. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gits J, van Leeuwen D, Carroll HP, Touw IP, Ward AC. Leukemia. 2006;20:2111–2118. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dong F, Brynes RK, Tidow N, Welte K, Lowenberg B, Touw IP. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:487–493. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508243330804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ward AC. Front Biosci. 2007;12:606–618. doi: 10.2741/2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Levine RL, Pardanani A, Tefferi A, Gilliland DG. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:673–83. doi: 10.1038/nrc2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]