Abstract

Objective

To examine the acceptance of repeat population-based voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) for HIV in rural Malawi.

Methods

Behavioural and biomarker data were collected in 2004 and 2006 from approximately 3000 adult respondents. In 2004, oral swab specimens were collected and analysed using ELISA and confirmatory Western blot tests, while finger-prick rapid testing was done in 2006. We used cross-tabulations with χ2 tests and significance tests of proportions to determine the statistical significance of differences in acceptance of VCT by year, individual characteristics and HIV risk.

Results

First, over 90% of respondents in each round accepted the HIV test, despite variations in testing protocols. Second, the percentage of individuals who obtained their test results significantly increased from 67% in 2004, when the results were provided in randomly selected locations several weeks after the specimens were collected, to 98% in 2006 when they were made available immediately within the home. Third, whereas there were significant variations in the sociodemographic and behavioural profiles of those who were successfully contacted for a second HIV test, this was not the case for those who accepted repeat VCT. This suggests that variations in the success of repeat testing might come from contacting the individuals rather than from accepting the test or knowing the results.

Conclusions

Repeat HIV testing at home by trained healthcare workers from outside the local area, and with either saliva or blood, is almost universally acceptable in rural Malawi and, thus, likely to be acceptable in similar contexts.

Comprehensive and regular voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) for HIV has been promoted as one strategy to curb the spread of HIV and as an essential element for antiretroviral treatment programmes.1–3 In sub-Saharan Africa—the region most affected by the AIDS epidemic—most of those who wish to be tested have to travel to a VCT or health facility, which may be a barrier to testing.4 There has, however, been an increase in the number of population-based surveys that have conducted door-to-door HIV testing in the region, including the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) that have conducted population-based HIV testing in more than a dozen countries in sub-Saharan Africa since 2001. Randomised trials and other community-based studies have documented greater acceptance of door-to-door VCT than when the services are provided in clinics.4–8

Although regular testing is a potentially promising prevention strategy in high HIV prevalence areas, few studies2 of door-to-door testing in population-based samples have examined whether those who have received their results once will agree to be tested and receive their results again. This paper examines differentials in the acceptance of testing, test results and repeat VCT for HIV among a population-based sample of adult respondents in rural Malawi.

METHODS

Data

The data come from the Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project (MDICP)—a longitudinal study conducted in three rural sites in Malawi: Rumphi in the Northern region, Mchinji in the Central region and Balaka in the Southern region. The project has conducted five waves of data collection: 1998, 2001, 2004, 2006 and 2008; in 2008, the project’s name was changed to Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH) to reflect the diverse research interests of the project team members.

The project introduced HIV testing in the third wave of the study in 2004; a total of 3284 respondents were contacted in their homes and 2983 (91%) provided samples for HIV testing. The samples were collected by trained nurses from outside the study sites using OraSure Oral swabs (OraSure Technologies, Philadelphia, USA). In addition, men were tested for gonorrhoea and chlamydia using urine samples while women were tested for gonorrhoea, chlamydia and trichomonas using vaginal swabs. Consent for both tests (HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs)) was sought separately so that respondents could provide samples for either, both or none of the tests. The percentage of contacted respondents that provided samples for the other STI tests was slightly lower than that for the HIV test (89% vs 91%). Whereas equal proportions of men and women provided samples for the HIV test (91%), a slightly lower proportion of women (88%) than men (91%) provided samples for the other STI tests, perhaps reflecting discomfort with vaginal swabs among some of the women. The specimens were analysed at the University of North Carolina Project’s Laboratory in Lilongwe (Malawi) using ELISA and confirmatory Western blot tests for HIV and Roche PCR (Roche Diagnostics, USA) for STIs.9

Test results were available 2–4 months after collecting the specimens. To preserve confidentiality, each specimen was labelled with unique biomarker identification (ID) number and respondents were given a Polaroid picture with their ID number to present when returning for test results. Team nurses provided the results and post-test counselling to respondents in mobile VCT clinics (small tents that served as private quarters) that were put up near the study villages once the results were available. To allow the investigation of the effect of distance on the uptake of HIV test results, the tents were placed at randomly selected locations within zones comprising villages grouped on the basis of the geo-spatial (GPS) coordinates of respondent households. The average linear distance to a tent was approximately 2 km; 95% of those tested lived within 5 km of the tents.10

The project also examined whether motivation to receive test results could be increased by a small monetary incentive. The VCT nurses offered those who provided specimens the opportunity to participate in an incentive lottery in which they drew bottle caps marked with amounts ranging from 0–300 Malawi Kwacha (approximately US $0–3) out of a bag. The amount drawn was recorded on a voucher bearing the respondent ID, which was to be redeemed upon returning for the test results.10 The average voucher amount was approximately US $1, worth slightly less than a day’s wage.11 The zero incentive was intended to gauge the demand for learning HIV results among those receiving no financial incentives. The distribution of zero and non-zero incentives was closely monitored to ensure that rules of randomisation were adhered to.10

In 2006, the project offered HIV testing again; certified VCT counsellors (also from outside the study sites) conducted rapid HIV tests (using parallel Determine (Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, USA) and UniGold (Trinity Biotech, Bray, Ireland) tests) in respondents’ homes. Respondents were given the option of receiving their test results in their homes or at mobile clinics (tents), which were to be set up at the end of the survey; virtually all of them chose the former. In order to preserve confidentiality, the respondent and the VCT counsellor together disposed of the test kit in a pit latrine after the VCT counsellor showed the respondent the test results and offered post-test counselling. A total of 2987 respondents were successfully contacted and offered a HIV test; 2758 (92%) were tested. There was no incentive lottery in 2006 due to the use of rapid testing.

Of those sample members who were successfully contacted in 2006, 26% had not been tested in 2004 because they refused (5%), were away at the time of the survey (4%) or were included in 2006 as new sample members—that is, new spouses to those already in the sample (17%). In addition, about a third (32%) of those who accepted a HIV test in 2004 were not tested in 2006 primarily due to mobility (12%), refusal (4%), death (1%) and inability to trace the respondent (15%). Loss to follow-up was somewhat higher in the South compared with the other two sites due to higher mobility and frequent name changes among respondents. However, this is unlikely to introduce bias.12–14

This paper presents data from the 2004 and 2006 waves.

Analysis

The analytic strategy in this paper is based on simple descriptive statistics—primarily cross-tabulations with χ2 tests as well as tests of proportions to determine the statistical significance of the observed associations and differences in acceptance of testing, test results, and repeat VCT for HIV by year, individual characteristics and HIV risk. Acceptance of repeat VCT in this analysis refers to accepting testing, obtaining the test results and receiving post-test counselling in 2006, conditional on being tested and obtaining the test results in 2004.

RESULTS

HIV/STI prevalence and HIV incidence

HIV prevalence in the MDICP sample remained stable at 7% between 2004 and 2006. The 2006 prevalence, however, is likely to be a slight overestimate since it includes those who were HIV positive in 2004 but refused the test in 2006 or were temporarily away in 2006 (non-respondents), and excludes those who were negative in 2004 but were not tested in 2006, for similar reasons. The rationale for this approach (of obtaining the 2006 prevalence), which in our opinion yields a more accurate estimate, was the higher loss to follow-up in that year (conditional on survival) and the higher likelihood of refusal among those who were HIV positive in 2004 compared with those who were HIV negative (see below) combined with the known HIV status of surviving non-respondents of the former (HIV positive) but not of the latter (HIV negative) group.

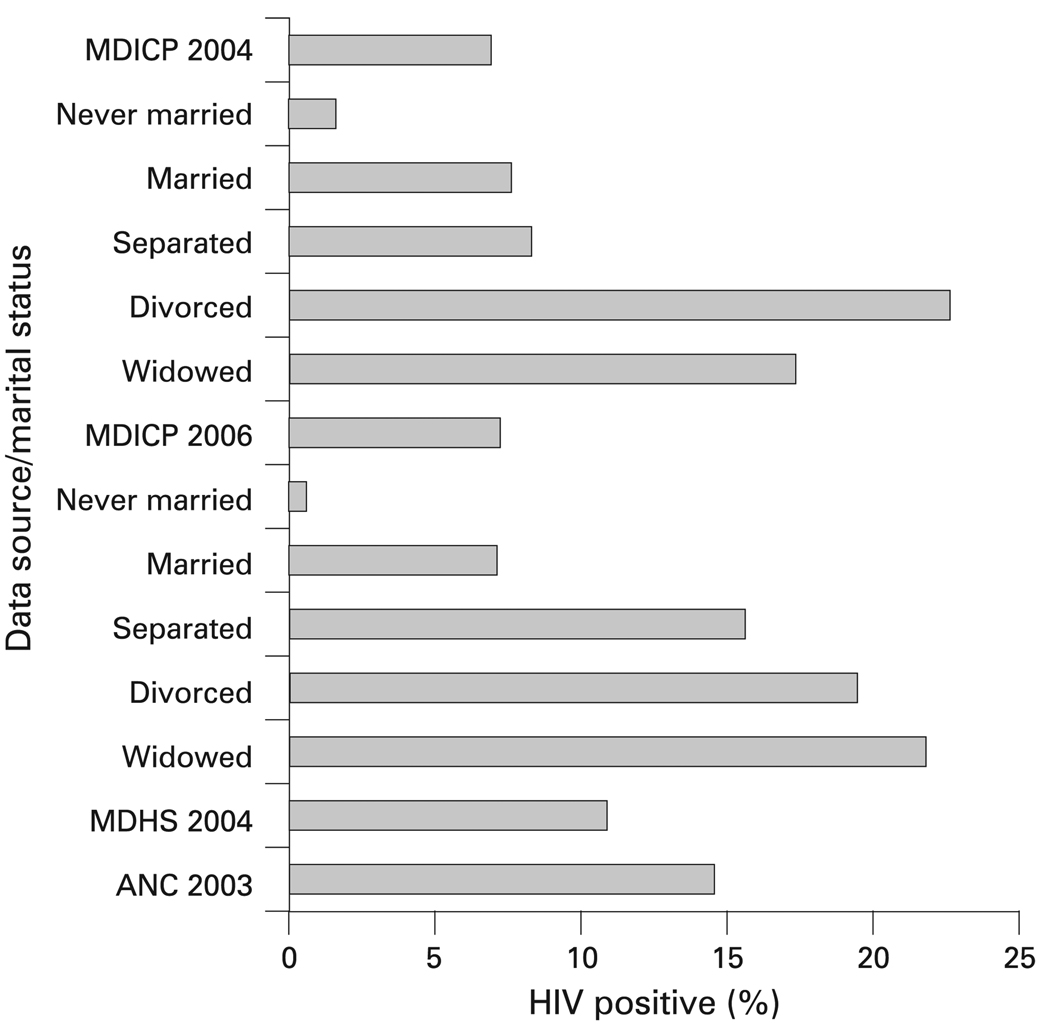

Both the 2004 and the 2006 MDICP estimates of HIV prevalence are considerably lower than the estimates for rural Malawi based on data collected in 2003 from all the rural antenatal clinics (ANCs) in the national HIV surveillance system (15%).15 They are also lower than the estimates based on the 2004 Malawi Demographic and Health Survey (MDHS 2004), which tested a representative sample of the national population and found rural prevalence to be 11% (fig 1).16 Age standardisation, using the MDHS 2004 age distribution as the standard, did not significantly change the MDICP estimates. A potential explanation for the variations in the HIV prevalence estimates between the MDICP and the MDHS is sampling variability coupled with the geographic variation in HIV prevalence. HIV prevalence has, for instance, been found to be higher near the market centres than in the rural villages.17 The MDICP sample probably consists of a larger proportion of individuals from the rural villages than the MDHS or ANCs; hence, the lower prevalence. Differentials and trends in prevalence are unlikely to be significantly affected by variations in the availability of antiretroviral treatment since rural Malawians had limited access to treatment before 2004.18

Figure 1.

HIV prevalence in rural Malawi by data source and by marital status (for Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project (MDICP) data only). ANC, antenatal clinic; MDHS, Malawi Demographic and Health Survey.

The prevalence of the other STIs was also low. Only 3% of the respondents who accepted STI testing tested positive for gonorrhoea. The prevalence of gonorrhoea was significantly higher among women (5%) than among men (0.3%; p<0.01) and in the South (5%) than in the Centre (2%) or the North (1%; p<0.01 in each case). The prevalence of chlamydia (0.3%) was substantially lower than that of gonorrhoea but reflects similar differentials: higher among women (0.5%) than among men (0.1%), and in the South (0.5%) than in the Centre (0.2%) or the North (0.1%). However, unlike gonorrhoea or chlamydia, the prevalence of trichomonas among women who accepted STI testing (2%) was higher in the Centre (4%) than in the South (3%) or the North (1%). The low STI prevalence in the MDICP sites is consistent with the low national prevalence of syphilis (3%).15 With the exception of trichomonas, the differentials in the prevalence of the other STIs in the MDICP sites largely mirror HIV prevalence: highest among women, and highest in the South followed by the Centre and then the North.

The estimated HIV incidence for the sample is 0.7 (95% CI 0.4 to 1.0) per 100 person-years (PY). Similar to differentials in the prevalence of HIV and other STIs, incidence was higher among women (0.8 per 100 PY) than among men (0.5 per 100 PY), although the difference was not statistically significant. It was also significantly higher in the South than in the other regions (1.3 per 100 PY vs 0.3 per 100 PY in the Centre and 0.4 per 100 PY in the North; p<0.01 in each case). These estimates are, however, based on the sample of individuals who participated in HIV testing in both 2004 and 2006. It is worth noting that the loss to follow-up (about 30% of those who were tested in 2004) may introduce an upward bias in the estimates if those who were HIV negative in 2004 but who did not participate in the test in 2006 had a lower risk of infection than their counterparts who accepted the subsequent test; a downward bias would result if they had a higher risk of infection than those who accepted the second test.

Acceptance of HIV testing

The acceptance of HIV testing among those successfully contacted for the test remained high (over 90%) and stable over the two survey years. There was also no significant difference in the proportion of individuals accepting the test by respondents’ background characteristics such as age, gender or study site (table 1). The high acceptance contrasts with our expectation of high likelihood of refusal, which was based on various factors, such as ambivalence about the value of a HIV test, the potential fear of stigma and the limited availability of treatment prior to 2004.19–22

Table 1.

Percentage of individuals who accepted the HIV test among those contacted for the test and percentage that obtained the test results among those who accepted the test by selected background characteristics, Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project (MDICP) 2004–2006

| MDICP 2004 | MDICP 2006 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accepted HIV test | Obtained test results* | Accepted HIV test | Obtained test results | |||||

| Characteristics | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n |

| Age group | ||||||||

| Adolescents (15–24 y) | 90.1 | 1124 | 63.0 | 1009 | 92.6 | 769 | 98.6 | 712 |

| Adults (25+ y) | 91.3 | 2153 | 69.5 | 1960 | 92.3 | 2218 | 98.3 | 2047 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 90.7 | 1517 | 66.6 | 1373 | 92.2 | 1326 | 98.5 | 1222 |

| Female | 91.0 | 1767 | 67.8 | 1600 | 92.5 | 1661 | 98.4 | 1573 |

| Study site | ||||||||

| South | 90.2 | 1189 | 71.6 | 1072 | 87.4 | 955 | 98.0 | 836 |

| Centre | 90.1 | 1000 | 72.9 | 893 | 91.9 | 1041 | 99.1 | 957 |

| North | 92.2 | 1095 | 57.6 | 1008 | 97.5 | 991 | 98.1 | 966 |

| Highest education level | ||||||||

| No formal schooling | 91.7 | 506 | 76.3 | 464 | 90.2 | 755 | 98.4 | 682 |

| Primary education | 91.0 | 2244 | 68.2 | 2036 | 92.9 | 1810 | 98.7 | 1681 |

| Secondary and above | 91.4 | 443 | 54.7 | 402 | 94.1 | 406 | 97.1 | 382 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Never married | 92.7 | 558 | 64.3 | 516 | 94.5 | 329 | 99.0 | 311 |

| Currently married | 90.7 | 2455 | 68.5 | 2217 | 92.1 | 2479 | 98.3 | 2283 |

| Formerly married† | 94.6 | 129 | 71.3 | 122 | 92.1 | 178 | 98.8 | 164 |

| HIV status | ||||||||

| Negative | NA | NA | 67.6 | 2755 | NA | NA | 98.7 | 2610 |

| Positive | NA | NA | 62.8 | 204 | NA | NA | 94.4 | 142 |

| Indeterminate‡ | NA | NA | 64.3 | 14 | NA | NA | 83.3 | 6 |

| Total | 90.8 | 3284 | 67.2 | 2973 | 92.3 | 2987 | 98.4 | 2758 |

Specimens for 10 individuals who accepted a HIV test in 2004 were spoilt;

formerly married refers to separated, divorced and widowed;

these were results that remained ambiguous: all the indeterminate cases in 2004 turned out to be HIV negative in 2006 when a different testing protocol was used; n, total number of respondents: under each category, this may differ from the grand total due to missing data; NA, not applicable because HIV status is only determined for those who accepted the test.

An obvious advantage of being tested at home is that it reduces the cost incurred in terms of distance and time to obtain the services. For instance, at the time of the 2004 testing, the nearest clinic where respondents from the study site in the South could obtain HIV tests was in Blantyre, about a 2-hour drive, with bus fare costing on average the equivalent of US $4. In the Northern site, the nearest HIV testing facility was in Mzuzu, about a 1-hour drive, with bus fare costing on average the equivalent of US $2. In addition, home-based testing might also have reduced the psychosocial costs of coping with an unfamiliar urban health facility, perhaps amplified by the widespread perception of health facility personnel as unfriendly. Our explanation cannot be complete, however, since the MDHS also conducted door-to-door HIV testing in 2004 and a high proportion of individuals (22% of rural respondents) refused the test.16 The MDHS took blood samples, which may have accounted, at least in part, for the high percentage of individuals refusing the test. In addition, perhaps the MDICP was advantaged by being known in the community, since respondents had already been surveyed twice before 2004.

Obtaining the test results

In 2004, HIV test results were available for 99.7% of those who provided the saliva specimens. Of these, about two-thirds (67%) obtained them. In contrast, nearly all respondents (98%) who accepted a HIV test in 2006 obtained the results (table 1). There were significant differences in the proportion of individuals who obtained their test results in 2004 by age group (χ2=12.6; p<0.01), study site (χ2=64.2; p<0.01) and educational attainment (χ2=46.8; p<0.01). However, in 2006 these differences were not significant. These changes (in the proportion obtaining test results and in the significance of variations by socio-demographic characteristics) could partly be attributed to the introduction of rapid testing in 2006. Nonetheless, some of the concerns for HIV testing, such as distance, treatment availability and ambivalence, might also be relevant for obtaining the test results.

To begin with, distance from the respondent’s home to the VCT tent was found to have a strong negative effect on whether an individual obtained the test results in 2004: those who lived within 1.5 km were 4.4 percentage points more likely to obtain their test results than those who lived more than 1.5 km but within 5 km from the tents.10 Second, the significantly larger fraction of respondents who obtained their HIV test results in 2006 as compared with 2004 is also likely to be related to the differential time lag in the availability of results. Rapid testing in 2006 provided the results within 20–30 minutes; in 2004, the requirement for lab testing and establishing mobile VCT clinics caused a delay of 2–4 months. The time lag in 2004 may have reduced the uptake of HIV test results as some people might have changed their mind while others might have moved, died or were temporarily away or bed-ridden by the time the test results were available. Third, in contrast to 2004, by 2006 treatment was more available and free, which might have motivated more people to learn their HIV status during the second testing. In addition, Malawi held its first National Testing Week in July 2006, which may have increased the motivation to learn the results.

The incentive experiment was also significantly associated with the likelihood of obtaining the test results in 2004. In particular, drawing a non-zero incentive and the amount of the non-zero incentive was found to be significantly associated with higher likelihood of obtaining the test results in 2004 compared with drawing a zero or small incentive amount.10

The overwhelming majority of those who received their results in 2004 were, as expected given the local prevalence, HIV negative. In communities (such as the study sample) where individuals overestimate the prevalence of HIV and their likelihood of being HIV positive,23 disclosure of negative HIV test results to others could motivate them to learn whether they also were negative. For instance, the likelihood that an individual obtained test results in 2004 was found to be significantly associated with nearby neighbours also obtaining theirs.24 In addition, the 2006 survey round asked respondents to whom they disclosed their results and who disclosed their results to them. A high proportion told someone: 85% of HIV-negative women reported telling their results to their spouses (with 95% of the spouses of these women confirming that they were told the results), 47% told a relative and 33% told a friend. A lower but nonetheless substantial proportion of those who were HIV positive (79%) disclosed their results to someone.

Acceptance of repeat VCT

Slightly more than three-quarters (77%) of those who were tested for HIV and who obtained their test results in 2004 were successfully contacted for a second test (table 2). The probability of successful contact for repeat HIV testing in 2006 was higher for those who tested negative in 2004 than for those who tested positive (p<0.01)—a pattern that is most likely related to the differential morbidity and mortality by HIV status (that is, some of those who were HIV positive in 2004 might have died or they might have been admitted to hospital with complications from HIV infection).

Table 2.

Conditional on accepting testing and obtaining the test results in 2004, percentage of respondents who were successfully contacted for HIV test in 2006, percentage of those who were contacted that accepted testing and percentage of those who accepted testing that obtained the test results by HIV status in 2004 and by background characteristics, Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project (MDICP) 2004–2006

| Successfully contacted in 2006 by HIV status in 2004 (%) |

Accepted testing by HIV status in 2004 (%) | Obtained test results by HIV status in 2004 (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics† | HIV negative | HIV positive | All respondents | HIV negative | HIV positive | All respondents | HIV negative | HIV positive | All respondents |

| Age group | ** | NS | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Adolescents (15–24 y) | 64.5 | 28.6 | 64.1 | 96.5 | 100.0 | 96.5 | 99.1 | 100.0 | 99.1 |

| Adults (25+ y) | 84.2 | 53.7 | 81.7 | 96.0 | 81.5 | 95.2 | 99.5 | 98.1 | 99.5 |

| Gender | * | ** | * | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Male | 76.3 | 38.0 | 74.3 | 96.2 | 94.7 | 96.2 | 99.2 | 94.4 | 99.1 |

| Female | 80.4 | 61.5 | 79.1 | 96.0 | 77.1 | 95.0 | 99.6 | 100.0 | 99.6 |

| Study site | NS | NS | * | ** | * | ** | NS | NS | NS |

| South | 76.9 | 50.0 | 74.8 | 93.0 | 67.9 | 91.8 | 99.4 | 100.0 | 99.4 |

| Centre | 77.5 | 53.2 | 76.0 | 95.9 | 88.0 | 95.6 | 99.6 | 100.0 | 99.6 |

| North | 81.7 | 56.0 | 80.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 99.3 | 92.9 | 99.2 |

| Highest education level | ** | NS | ** | NS | NS | NS | ** | NS | * |

| No formal schooling | 85.6 | 62.5 | 83.8 | 95.3 | 84.0 | 94.7 | 99.5 | 100.0 | 99.5 |

| Primary education | 77.0 | 50.7 | 75.4 | 96.2 | 79.0 | 95.5 | 99.8 | 96.7 | 99.7 |

| Secondary and above | 74.3 | 30.8 | 72.0 | 97.7 | 100.0 | 97.8 | 97.7 | 100.0 | 97.7 |

| Marital status | ** | NS | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Never married | 61.5 | 14.3 | 60.3 | 96.5 | 100.0 | 96.5 | 98.8 | 100.0 | 98.8 |

| Currently married | 82.7 | 55.2 | 80.9 | 96.0 | 82.8 | 95.5 | 99.5 | 97.9 | 99.4 |

| Formerly married‡ | 78.6 | 50.0 | 74.8 | 96.3 | 75.0 | 94.4 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Total | 78.5 | 52.3 | 76.9 | 96.1 | 82.1 | 95.5 | 99.4 | 98.2 | 99.4 |

| n | 1862 | 128 | 1999 | 1462 | 67 | 1537 | 1405 | 55 | 1468 |

χ2 tests: * p<0.05;

p<0.01;

NS, not significant;

all characteristics pertain to 2006;

formerly married refers to separated, divorced and widowed.

It is notable that whereas there were significant variations in the sociodemographic and behavioural profiles of those who were re-contacted for a second HIV test, there was little significant variation in the profiles of those who accepted the second test or those who obtained the test results (table 2 and table 3). Multivariate logit models of the probability of being successfully contacted in 2006 and of accepting testing conditional on being contacted result in similar conclusions (see table A1 of supplementary material). In addition, nearly all those who obtained a negative HIV test result and were re-contacted accepted a second test and virtually all those who accepted the test obtained the results. Of those who learned in 2004 that they were HIV positive, slightly more than half (52%) were re-contacted. Of these, 82% accepted a second test and nearly all those who accepted the second test obtained their test results.

Table 3.

Conditional on accepting testing and obtaining the test results in 2004, percentage of respondents who were successfully contacted for the HIV test in 2006, percentage of those who were contacted that accepted testing and percentage of those who accepted testing that obtained the test results by HIV status in 2004 and by HIV-risk characteristics, Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project (MIDCP) 2004–2006

| Contacted in 2006 by HIV status in 2004 (%) |

Accepted testing by HIV status in 2004 (%) | Obtained test results by HIV status in 2004 (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics† | HIV negative | HIV positive | All respondents | HIV negative | HIV positive | All respondents | HIV negative | HIV positive | All respondents |

| Number of unions | ** | NS | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Never married/married once |

76.7 | 45.0 | 75.3 | 96.1 | 81.5 | 95.8 | 99.5 | 100.0 | 99.5 |

| Multiple unions | 84.8 | 58.8 | 81.9 | 96.2 | 82.5 | 95.1 | 99.8 | 97.0 | 99.6 |

| Number of life-time sexual partners |

NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| No partner/one | 79.2 | 48.2 | 78.0 | 95.6 | 84.6 | 95.3 | 99.2 | 100.0 | 99.2 |

| Multiple partners | 82.3 | 56.8 | 80.3 | 96.4 | 81.5 | 95.7 | 99.6 | 97.7 | 99.5 |

| Suspects spouse/partner of infidelity |

** | NS | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| No/no partner/don’t know | 81.7 | 55.7 | 80.5 | 96.3 | 84.1 | 95.9 | 99.3 | 97.3 | 99.3 |

| Suspects/knows | 73.3 | 48.9 | 70.3 | 95.1 | 78.3 | 93.7 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Worried about getting AIDS | ** | NS | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| No/don’t know | 82.4 | 53.6 | 81.0 | 96.5 | 86.7 | 96.2 | 99.4 | 96.2 | 99.3 |

| Worried a little/a lot | 74.1 | 51.4 | 72.3 | 95.5 | 78.4 | 94.6 | 99.5 | 100.0 | 99.5 |

| Perceived risk of current infection |

* | NS | * | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| No/low risk/don’t know | 79.1 | 49.0 | 77.5 | 95.9 | 81.6 | 95.4 | 99.4 | 97.5 | 99.3 |

| Medium/high risk | 72.1 | 64.3 | 70.9 | 99.1 | 83.3 | 96.8 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Knows someone with/died of AIDS |

** | * | ** | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| No/don’t know | 59.3 | 88.9 | 62.0 | 98.2 | 75.0 | 95.2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 81.2 | 50.4 | 79.3 | 96.0 | 83.1 | 95.5 | 99.4 | 98.0 | 99.4 |

| Total | 78.5 | 52.3 | 76.9 | 96.1 | 82.1 | 95.5 | 99.4 | 98.2 | 99.4 |

| n | 1862 | 128 | 1999 | 1462 | 67 | 1537 | 1405 | 55 | 1468 |

χ2 tests: *p<0.05;

p<0.01;

NS, not significant;

all characteristics pertain to 2006.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study expand the available evidence on repeat HIV testing among population-based samples. First, the proportion of respondents accepting HIV testing was high and stable over time despite the obstacles (real or perceived) to testing and regardless of the testing protocol. There are a number of possible explanations for the apparent preference for at-home testing, including the cost of travelling to health facilities and what appears to be a greater trust that the testing procedure will be confidential. Qualitative evidence from the MDICP as well as from a similar study in Uganda that provided rapid testing at home shows that individuals expressed preference for home-based to clinic-based VCT because of confidentiality concerns at the clinic.4 25 26 This is a useful result for policy-makers, given the recommendations of WHO and UNAIDS regarding regular testing for all to curb the spread of HIV/AIDS.3

Second, both distance and a delay between testing and the availability of results are important barriers to receiving results. Distance is associated with costs in transport and time; delay means that the circumstances or motivation of some of those who would have obtained their results may have changed—they may have moved, died or changed their mind.27 The role of distance and delay are likely to be amplified in contexts where people overestimate the transmission probabilities of HIV and, thus, their likelihood of being HIV positive, as in rural Malawi.23

Third, our study documented significant variations in the sociodemographic and behavioural characteristics of those who were successfully contacted for the second HIV test. In contrast, there was little significant variation in the profiles of those who accepted repeat VCT (accepted testing and obtained the test results for the second time conditional on having done so during the first testing). This suggests that significant variations in the success of repeat population-based testing arise due to the differential probabilities of finding individuals for repeat VCT rather than from the differential probabilities of accepting the test conditional on successful re-contact or of learning the results of the test. We can, however, only speculate as to why individuals accepted repeat VCT. Perhaps those who learned they were HIV positive in 2004 hoped that a test in 2006 would disprove those results; perhaps those who learned they were HIV negative in 2004 but had subsequently engaged in risky behaviour hoped that a test in 2006 would show that they were still negative. In addition, it is likely that having been tested once would reduce the psychosocial costs of testing. We also speculate that in a context where many overestimate their likelihood of being HIV positive, as well as the prevalence of HIV in their community,23 the disclosure of negative test results to relatives, friends and neighbours may increase the acceptability of testing, as would dissemination of accurate information about HIV prevalence in the area.

Key messages.

Repeat door-to-door HIV testing is almost universally acceptable in rural Malawi and is likely to be so in similar contexts.

Distance is an important barrier to receiving results and so may be a delay in the availability of results as well as treatment availability.

Significant variations in the success of repeat population-based HIV testing are likely to result from the differential probabilities of locating individuals for repeat voluntary counselling and testing.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions to the collection of the biomarker data by volunteer student members of the research team: N Angotti, S Bignami-Van Assche, J Browning, L Gaydosh, E Kimchi, A Allen, G Reniers and K Smith. Other team members whose contributions were crucial to data collection are listed at http://www.malawi.pop.upenn.edu. We further acknowledge the valuable comments from anonymous reviewers of the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grants: NICHD-RO1 HD044228-01 and NICHD-RO1HD/MH41713-0.

Footnotes

To order reprints of this article go to: http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Approved by the institutional review boards at the College of Medicine Research Ethics Committee (COMREC) in Malawi and the University of Pennsylvania in the United States.

Contributors: FO worked as a Graduate Student Assistant in the 2004 and 2006 MDICP surveys and prepared the manuscript and carried out the relevant analyses. PF served as the Research Director in the two surveys and worked closely with FO in preparing the manuscript. PA coordinated the biomarker collection in 2004, served as Fieldwork Director in 2006 and prepared the data for the paper. RT was responsible for the incentive experiment and the provision of VCT in 2004, and contributed towards the preparation of the manuscript, especially the sections on incentives and obtaining of the test results in 2004. FM was responsible for managing the laboratory analysis of HIV and STI samples and for reviewing the HIV testing protocol in 2004. AK was responsible for training the nurses and VCT counsellors in 2004 and 2006, respectively. MP served as Fieldwork Director in 2004 and contributed towards the preparation of the manuscript. SW and H-PK were the Principal Investigators in 2004 and 2006, and contributed to the analytic design and the writing of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Family Health International. [accessed 17 November 2008];Counseling and Testing for HIV. 2006 http://www.fhi. org/en/hivaids/pub/fact/vctforhiv.ht.

- 2.Matovu JKB, Gray RH, Kiwanuka N, et al. Repeat voluntary HIV counseling and testing (VCT), sexual risk behavior and HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9170-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO and UNAIDS. Guidance on provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in health facilities. Geneva: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoder PS, Katahoire AR, Kyaddondo D, et al. Home-Based HIV Testing and Counselling in a Survey Context in Uganda. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ORC Macro; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bateganya MH, Abdulwadud OA, Kiene SM. Home-based HIV voluntary counseling and testing in developing countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007;(Issue 4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006493.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolff B, Nyanzi B, Katongole G, et al. Evaluation of a home-based voluntary counselling and testing intervention in rural Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20:109–116. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Were W, Mermin J, Bunnell R, et al. Home-based model for HIV voluntary counselling and testing. Lancet. 2003;361:1569. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fylkesnes K, Siziya S. A randomised trial on acceptability of voluntary HIV counselling and testing. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:566–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bignami-Van Assche S, Chao LW, Hoffman I, et al. Protocol for biomarker testing in the 2004 Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania; SNP Working Paper No.7. 2004

- 10.Thornton R. The demand for learning HIV status and the impact on sexual behavior: Evidence from a field experiment. Am Econ Rev. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Food Policy Research Institute. Malawi: An atlas of social statistics. Malawi: National Statistical Office [Malawi] and the International Food Policy Research Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bignami-Van Assche S, Reniers G, Weinreb AA. An assessment of the KDICP and MDICP data quality: Interviewer effects, question reliability and sample attrition. Demog Res. 2003 S1:31–76. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anglewicz P, Adams J, Obare F, et al. The Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project 2004–06: Data collection, data quality and analyses of attrition. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania; SNP Working Paper No.12. 2006 doi: 10.4054/demres.2009.20.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Obare F. The Effect of non-response on population-based HIV prevalence estimates: The case of rural Malawi. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America; Los Angeles. 30 March to 1 April, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National AIDS Commission [Malawi]. HIV Sentinel Surveillance Report 2003. Ministry of Health and Population; National AIDS Commission: Republic of Malawi. 2003

- 16.National Statistics Office (NSO) [Malawi] and ORC Macro. Calverton, Maryland: NSO and ORC Macro; Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2004. 2005

- 17.Boerma JT, Urassa M, Nnko S, et al. Sociodemographic context of the AIDS epidemic in a rural area in Tanzania with a focus on people’s mobility and marriage. Sex Trans Inf. 2002;78:97–105. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harries A, Makombe S, Libamba E, et al. 5-year plan for antiretroviral therapy scale-up in Malawi: 2006-2010 [abstract]. Paper presented at The XVI International AIDS Conference; 13–18 August 2006; Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoder PS, Matinga P. Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT) for HIV in Malawi: Public Perspectives and Recent VCT Experiences. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ORC Macro; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nyblade L, Field-Nguer M. Women, communities, and the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: issues and findings from community research in Botswana and Zambia. The Population Council and the International Center for Research onWomen. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanduza AM. Tackling HIV/AIDS and related stigma in Swaziland through education. EASSRR. 2003;XIX:75–87. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skinner D, Mfecane S. Stigma, discrimination and its implications for people living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Sahara J. 2004;1:157–164. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2004.9724838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anglewicz P, Kohler H-P. Overestimating HIV Infection: The Construction and Accuracy of Subjective Probabilities of HIV Infection in Rural Malawi. Paper presented at the Meeting of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (IUSSP); 18–24 July 2005; Tours, France. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Godlonton S, Thornton R. Neighbors, Social Interactions and Learning HIV Results. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America; 17–19 April 2008; New Orleans. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimchi E. Reactions to At-Home Voluntary Counseling and Rapid HIV Testing in Rural Malawi. Unpublished working paper. Philadelphia: Jefferson Medical College; 2006. [(accessed 17 November 2008)]. http://www.malawi.pop.upenn.edu/Level%203/Papers/PDF-files/kimchi_2006.doc. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angotti N, Bula A, Gaydosh L, et al. The fear factor in HIV testing: local reactions to door-to-door rapid blood testing for HIV in rural Malawi; Paper presented at the American Sociological Association Annual Conference; 11–14 August 2007; New York. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matovu JKB, Gray RH, Makumbi F, et al. Voluntary HIV counseling and testing acceptance, sexual risk behavior and HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2005;19:503–511. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000162339.43310.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]