Abstract

The human copper transporter hCTR1 is a homotrimer composed of a plasma membrane protein of 190 amino acids that contains three transmembrane segments. The extracellular 65-amino acid amino terminus of hCTR1 contains both N-linked (at Asn15) and O-linked (at Thr27) sites of glycosylation. If O-glycosylation at Thr27 is prevented, hCTR1 is efficiently cleaved, removing ∼30 amino acids from the amino terminus. We have now investigated (i) the site of this cleavage, determining which peptide bonds are cleaved, (ii) the mechanism by which glycosylation prevents cleavage, and (iii) where in the cell the proteolytic cleavage takes place. Cleavage occurs in the sequence Ala-Ser-His-Ser-His (residues 29–33), which does not contain previously recognized protease cleavage sites. Using a series of hCTR1 mutants, we show that cleavage occurs preferentially between residues Ala29–Ser30–His31. We also show that the O-linked polysaccharide at Thr27 blocks proteolysis due to its proximity to the cleavage site. Moving the cleavage site away from the Thr27 polysaccharide by insertion of as few as 5 amino acids allows cleavage to occur in the presence of glycosylation. Imaging studies using immunofluorescence in fixed cells and a functional green fluorescent protein-tagged hCTR1 transporter in live cells showed that the cleaved peptide accumulates in punctate structures in the cytoplasm. These puncta overlap compartments were stained by Rab9, indicating that hCTR1 cleavage occurs in a late endosomal compartment prior to delivery of the transporter to the plasma membrane.

Copper is acquired by eukaryotic cells through transporters in the plasma membrane known as CTR proteins (1). Copper is an essential enzymatic cofactor in numerous proteins, many of which perform electron transfer reactions in which the metal cycles (2, 3) between the redox states (Cu+ and Cu2+) (4). This readily occurring redox reaction can make copper ions toxic to cells through the generation of reactive oxygen species. The free copper concentration in cells is extremely low (less than 1 fmol), and there is essentially no free copper in serum. Hence, copper transporters receive copper from copper-binding substrates in the serum, translocate it across the membrane, and transfer it to intracellular chaperones for delivery to target proteins (5).

Human copper transporter 1 (hCTR1)2 and orthologous proteins throughout eukaryotes have three transmembrane segments (6, 7) and form homotrimeric, membrane complexes (8, 9) that carry out the high affinity transport of monovalent copper (see Fig. 1, inset). The human hCTR1 gene was discovered by its ability to complement Saccharomyces cerevisiae yCtr mutants, demonstrating that high affinity copper transport is a conserved function among the CTR1 proteins (10). The CTR1 proteins range in size from 200 to 400 amino acids (1, 11), but share methionine- and histidine-rich motifs in the extracellular amino terminus, as well as conserved sequences in transmembrane segments (1, 12).

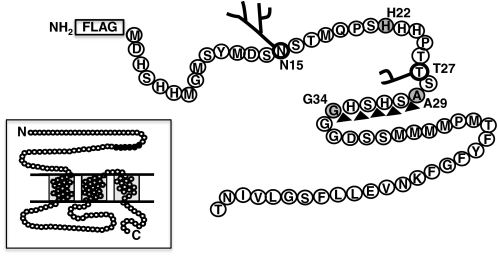

FIGURE 1.

Extracellular amino terminus of hCTR1. Location of N- and O-linked glycosylation at Asn15 and Thr27, and the end points of 3 truncation mutants in gray: H22, A29, and G34. In the absence of O-glycosylation at Thr27, hCTR1 is efficiently cleaved between A29 and G34 (black triangles). Location of the FLAG epitope tag is shown. Inset shows the complete 190-amino acid hCTR1 protein, with extracellular NH2 terminus, three membrane spanning domains, intracellular loop, and COOH-terminal tail. The 5 amino acids in which cleavage occurs are shown in black. Three hCTR1 polypeptides form a symmetrical trimer in the copper transporter (8, 9).

Little is known about the details of the copper transport mechanism in CTR1 proteins. Mutational studies of hCTR1 have identified a number of residues important for copper transport (12–14), such as methionine residues within the extracellular amino terminus, and two transmembrane segments that were important for 64Cu uptake in cultured cells (12). A study of hCTR1 mutants expressed in insect cells identified residues in or near the transmembrane domains that affect Km and or Vmax of 64Cu uptake (14). These results and recent structural studies suggest that copper transits a pore lined by transmembrane segments two and three in the homotrimeric complex (8, 9). Another mechanism based on endocytosis and degradation of hCTR1 has also been proposed (15).

Vertebrate CTR1 proteins are widely expressed, and may play other roles in addition to copper transport. Mice homozygous for mCtr1 knock-out alleles die during midgestation, which was thought to reflect an early requirement for copper transport during development. However, a recent study showed that xCTR1 was part of a fibroblast growth factor signaling complex in Xenopus embryos active in Ras/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling. The signaling role, which affects embryonic development in Xenopus and ES cell differentiation in mammalian cells, appears to be independent of the copper transport activity of CTR1 (16).

In previous structure/function studies of hCTR1 we found that the extracellular amino terminus of ∼65 amino acids is modified by N- and O-linked glycosylation at Asn15 and Thr27, respectively (6, 17) (see Fig. 1). N-Linked glycans at Asn15 increase the predicted mass of the hCTR1 polypeptide by about 9 kDa. Removing N-linked polysaccharides by a N15Q mutation does not significantly affect the expression or function of the transporter (6, 17). O-Linked polysaccharides at Thr27 that terminate in sialic acid residues increase the mass of the polypeptide by 1–2 kDa, (17). In the absence of O-linked glycosylation, the polypeptide undergoes very efficient cleavage near Thr27, leaving a 17-kDa hCTR1 protein lacking about 30 amino acids from the extracellular amino terminus (Fig. 1). The truncated (17 kDa) hCTR1 protein was efficiently delivered to the plasma membrane, but exhibited only 50–60% of the copper transport activity of wild-type hCTR1 (17).

In recent years, an impressive variety of proteases have been characterized in the secretory pathway and plasma membrane (18–22). Many of these proteases perform some kind of regulatory cleavage, from maturation of pre-proteins, (including proteases), to membrane proteases involved in shedding of ectodomains. Presumably, cleavage of hCTR1 lacking O-linked glycosylation must occur after the addition of the O-linked sugars would have occurred in the golgi (23). Cleavage of the unglycosylated hCTR1 protein could thus occur while the transporter is en route to the plasma membrane (23, 24), after delivery to the surface, or, as in the case of some receptors, during recycling between the plasma membrane and interior compartments (25–28).

In this report, we show that inhibition of cleavage by O-linked glycosylation at Thr27 requires close proximity of the polysaccharide to the site of cleavage. Moving the cleavage site away from Thr27 polysaccharides allowed cleavage. In mutants lacking O-glycosylation, hCTR1 is cleaved within amino acids 29–33 (ASHSH), preferentially between Ala29–Ser30–His31. Live cell imaging of GFP-tagged mutant hCTR1 and staining of fixed cells overexpressing FLAG-tagged hCTR1 shows that the cleaved amino-terminal peptides accumulate in punctate structures that partially overlap Rab9, a late endosome marker, suggesting that cleavage occurs after transit through the golgi, but prior to delivery to the plasma membrane.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

HEK-293 FLp-InTM T-RexTM and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) FLp-In T-Rex cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco's minimal essential media (DMEM, Invitrogen), 25 mm Hepes buffer, and 10% fetal calf serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA). All cells were grown at 37 °C in 5% CO2. HEK-293 FLp-In T-Rex cells were purchased from Invitrogen, and maintained with selective antibiotics as suggested by the manufacturer.

Cell lines containing tetracycline-regulated hCTR1 genes were created in HEK-293 FLp-In T-Rex cells using the Invitrogen FLp-In T-Rex core kit. Briefly, the cells were transfected with various hCTR1 constructs (see below) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Transfected cells were selected in 12 μg/ml of (HEK-293) blastocidin S (RPI Corp., Mt. Prospect, IL) and 400 μg/ml of hygromycin (Invitrogen). For induction, cells were cultured in media containing 1 μg/ml tetracycline for 48 h prior to harvesting, imaging, or fixing for microscopy.

hCTR1 Expression Constructs and Mutants

The wild-type hCTR1 cDNA clone used here was obtained from Dr. J. Gitschier, University of California, San Francisco (GenBankTM accession number U83460, HGNC). An AgeI site was added 5′ of the initiating methionine codon by ligation of annealed oligos (17) between the 5′ BamHI site and the NdeI site at nucleotide +16 in the hCTR1 coding sequence. A FLAG epitope tag was added to the amino terminus by ligation of annealed oligos between BamHI and AgeI to produce clone pEM79. This NH2-terminal FLAG-tagged hCTR1 cDNA was ligated into the FLp-In vector pcDNA5/FRT/TO® (Invitrogen) as a BamHI-ApaI fragment to produce pEM83 (17).

This same BamHI-ApaI fragment was subcloned into the pBSIIKS− vector (Stratagene) to produce pEM94, which was used as a template for insertion mutants having 1, 3, or 5 amino acids placed between the site of O-glycosylation and the ASHSH (Ala29–His33) cleavage site in the hCTR1 protein. A triple alanine substitution at Thr26–Thr27–Ser28 designated pEM98 was derived from pEM94 (17). pEM98 was used to generate various substitution, insertion, and deletion mutants described in this article, using overlapping PCR mutagenesis or the QuikChange® II Site-directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). BamHI-ApaI or BamHI-ClaI fragments from the various mutants were cloned into FLp-In vector pcDNA5/FRT/TO (Invitrogen) to make expression constructs. FLAG-tagged amino-terminal hCTR1 truncations at H22 (pEM85) and A29 (pEM86) were previously described (17).

To construct an amino-terminal GFP-tagged hCTR1, we obtained an enhanced green fluorescent protein clone fused to the signal cleavage sequence from calreticulin as a generous gift from Dr. Sojin Shikano (University of Illinois, Chicago). The initiating methionine, signal cleavage sequence, and GFP coding sequence were excised with BamHI and AgeI sites in the oligo, and inserted into equivalent sites in pEM83 (WT hCTR1) and pEM106 (AAA substitution at Thr26–Thr27–Ser28 in hCTR1). Specific oligonucleotide sequences used to make the mutants described in this article, or small amounts of mutant plasmid DNA are available on request.

Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase was purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA) Pfu Turbo® polymerase for PCR was purchased from Stratagene. Oligos were purchased from Invitrogen, and DNA sequencing was performed by the Research Resources Center at the University of Illinois, Chicago.

Anti-hCTR1 Antibodies and Affinity Purification

The affinity purified rabbit anti-hCTR1 antibody raised against the carboxyl terminus or cytoplasmic loop of hCTR1 was described previously (17). The anti-hCTR1 antibodies described in this work were raised against a 16-amino acid peptide corresponding to the amino terminus (MDHSHHMGMSYMDSC purchased from GeneScript, Piscataway, NJ). This peptide was used to immunize rabbits (Cocalico Biologicals, Reamstown, PA). Pre-immune and immune sera were tested for reactivity against hCTR1.

hCTR1 amino-terminal peptide was coupled to Actigel ALD resin matrix using the manufacturer's instructions (Sterogene, Carlsbad, CA). Post-coupled resin was packed into columns and used to affinity purify anti-hCTR1 antibody from IgG. Bound antibody was eluted with Actisep elution medium (Sterogene), which was subsequently removed by desalting into PBS. The antibody was concentrated in spin concentrators (Vivascience AG, Hanover, Germany). IgG was purified from anti-hCTR1 whole serum using the Melon GelTM system (Pierce).

Membrane Preparation

Cells were washed twice in PBS on 10- or 15-cm plates and harvested by scraping. Cells were homogenized in a mixture of protease inhibitors (Roche, Mannheim Germany). Homogenization was done in a tight-fitting Dounce homogenizer, followed by passing the lysate 3 times through a 28-gauge needle. Large debris was cleared by centrifugation at 1,200 × g. The resulting microsomal supernatant was centrifuged at ≥90,000 × g to pellet total membranes, or layered in 5 step gradients to recover fractions enriched for membranes from the endoplasmic reticulum, golgi complex membranes, or plasma membranes as described (17). The method of Bradford (29) was used to determine membrane protein concentration.

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitations (IP) were performed using membranes solubilized in n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (RPI Corp., Mt. Prospect, IL). Membranes were resuspended in 0.1 m phosphate, pH 7.2, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm dithiothreitol, and 1% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside for 45–60 min at room temperature. Samples were spun at ≥90,000 × g for 25 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were diluted into IP buffer (50 mm phosphate, pH 7.2, 200 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm dithiothreitol, and 0.5% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside). IP reactions were performed exactly as described (17).

Cell Surface Biotinylation (Cysteine Labeling)

HEK-293 cells were surface biotinylated with a reversible (thiol-cleavable) sulfhydryl labeling reagent (Biotin-HPDP, Pierce) as described for labeling of amine groups (17). The cells were washed from 10-cm plates with DMEM without fetal calf serum and spun 10 min at 800 × g at 4 °C. Pellets were washed twice in PBS, and the cells were divided in half. Half of the cells were biotinylated while rotating for 25 min at 4 °C and quenched in buffers as described (17). Washed cells were then solubilized in 1% Triton X-100 for 60 min, then insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g. Supernatants were incubated overnight at 4 °C with 100 μl of streptavidin beads (Pierce) that were equilibrated in solubilization buffer. The beads were collected and washed as described (17), after which the proteins bound to the beads were cleaved with 50 mm dithiothreitol in 2× SDS electrophoresis sample buffer at 30 °C for at least 5 h prior to SDS-PAGE. The remaining un-biotinylated cells were prepared and fractionated on 5 ml of 5 step gradients (17), and plasma membrane fractions were collected.

PAGE and Western Blots

12 or 15% SDS-PAGE was performed using the method of Laemmli (30). Gels were transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford MA) in 0.1 m CAPS buffer, pH 11, dried, and blocked with 5% powdered milk and 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS. Membranes were incubated with primary and secondary antibodies in the same solution, and washed after incubations in PBS, 0.1% Tween. Western blot signals were obtained using SuperSignal® West reagents (Pierce) and collected with a Chemi-Doc XRS system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Relative band intensity was determined using Quantity One® software (Bio-Rad). In some cases, images were taken on film.

64Cu Uptake Assays

64Cu uptake assays were similar to those described previously (17). Two days prior to the assays, tetracycline was added to cells receiving the drug at 1 μg/ml. 1 day prior to the assays, 12-well tissue culture plates were seeded with 1.5 × 106 cells/well in DMEM, 10%, +/− tet. The following day the cells were washed once with DMEM, 10% (without antibiotics), then incubated in DMEM, 10%, containing 2.0 μm CuCl2 and trace amounts of 64Cu (0.5–2.0 × 106 cpm/well) for 5 min at room temperature or 30 min at 37 °C. Copper uptake was stopped by removing 64Cu and adding ice-cold buffer, then washed and prepared as described for scintillation counting and protein determination (17). 64Cu uptakes from 5-min incubations were subtracted from 30-min incubations to correct for nonspecific binding.

To normalize expression between tet-induced cell lines, portions of cells used in 64Cu uptake experiments were saved and membranes were fractionated. 10 μg of plasma membrane protein from each line was analyzed on Western blots as described (17). Copper uptake rates were normalized for differences in expression of hCTR1, setting overexpressed wild-type, FLAG-tagged hCTR1 to a value of 1.0 in each experiment.

Confocal Microscopy

Cells for imaging were grown on collagen-coated coverslips. The cells were fixed for 15 min at 4 °C in PBS containing 4% formaldehyde and 30 mm sucrose, then washed four times in PBS/sucrose. The cells were then permeabilized by incubating for 5 min in 0.5% saponin in PBS, then washed 4 times in PBS. The cells were then blocked overnight at 4 °C with a solution of PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin, 1% normal goat serum, and 1% normal donkey serum (AbA), then incubated with primary antibodies for 1–2 h at room temperature in AbA. After washing 4 times in AbA diluted 5-fold in PBS (AbB), the cells were incubated 1 h with secondary antibodies in AbA. After washing 4 times in AbB, the coverslips were mounted on slides with Vectashield® and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Labs Inc., Burlingame, CA).

Fixed and live cell images were collected with a Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal laser scanning microscope using a plan Apochromat ×63/1.4 oil objective. For live cell imaging, three markers were used: Cell MaskTM Orange, Transferrin-Alexa Fluor 555 conjugate, and Lysotracker® Red DND-99 (Invitrogen). For double labeling studies on fixed cells, antibodies against various proteins or secondary antibodies were obtained from Invitrogen (golgin97, PMP70, Alexa 488 anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies), Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO (Rab9, EEA1), Cell Signaling, Beverly MA (Rab5), abcam, Cambridge, MA (Rab7), and Jackson Labs, West Grove, PA (Dylight 488 and 549 anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies).

Chemicals and Protease Inhibitors

Standard reagent chemicals were from Fisher (Pittsburgh, PA) or Sigma. Protease inhibitors were from EMD/Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA), except pepstatin, which was from Sigma. 64Cu was produced at Washington University, St. Louis, MO.

RESULTS

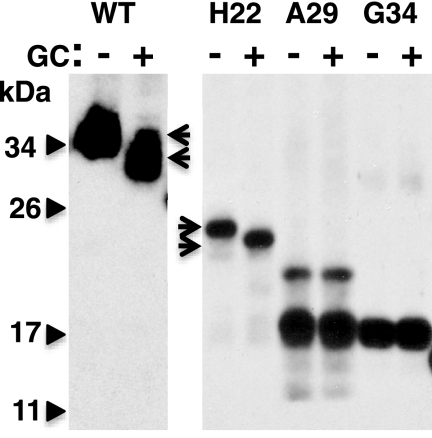

We narrowed the position in which hCTR1 cleavage occurs in the absence of O-glycosylation to a 5-amino acid peptide. We had previously mapped the location of O-linked sugars using a series of amino-terminal truncations (see Fig. 1 for location of truncations). Wild-type hCTR1 was O-glycosylated, as shown in Fig. 2, by a shift in mobility following treatment with a mixture of glycosidases (GC) specific for O-linked polysaccacharides (WT lanes, see arrows). H22, a truncation that lacked the first 21 amino acids of wild-type hCTR1, but included Thr26–Thr27–Ser28 was also shifted by glycosidase treatment (Fig. 2, H22 lanes, see arrows). The next truncation in the series, A29, which lacked the first 28 amino acids, was not O-glycosylated, and was not shifted by glycosidase treatment (Fig. 2, A29 lanes). However, this mutant underwent a very efficient cleavage that removed the amino-terminal FLAG tag, leaving the major 17-kDa product (Fig. 2, A29 lanes). The 17-kDa fragment migrated in PAGE slightly slower than a truncation that lacked the first 33 amino acids (with the addition of a Met residue) of hCTR1 (Fig. 2, G34 lanes). The site of cleavage in hCTR1 polypeptides lacking O-glycosylation was therefore contained within amino acids 29–33 (Ala-Ser-His-Ser-His or ASHSH).

FIGURE 2.

O-Glycosidase treatment of hCTR1 proteins. Wild-type, H22, A29, and G34 proteins were overexpressed in HEK-293 cells and recovered in plasma membrane fractions. Arrows show the shift of wild-type and H22 after treatment with a mixture of glycosylases specific for O-linked polysaccharides (GC, see Ref. 17). The A29 mutant, which is not O-glycosylated, is mostly cleaved to yield a 17-kDa fragment migrating close to the G34 truncation. The uncleaved A29 mutant contains a FLAG tag. G34 has an initiator methionine at the amino terminus. All lanes were taken from the same gel.

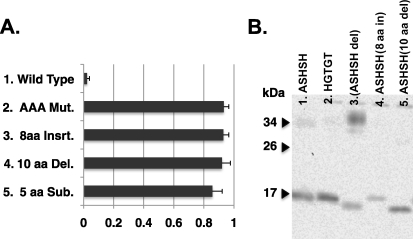

Proximity of O-Linked Sugars Protects against Cleavage

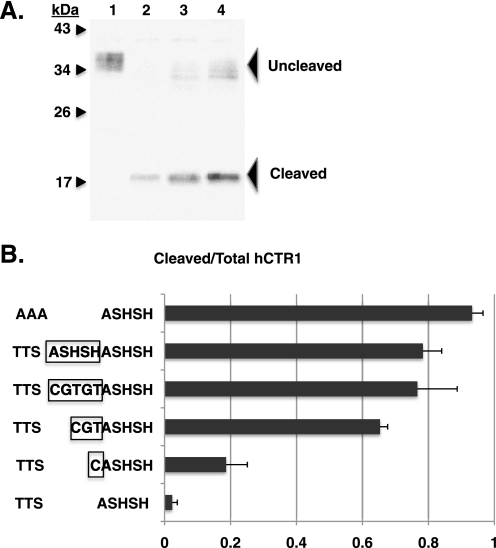

We tested the hypothesis that the proximity of the O-linked polysaccharide protects the ASHSH site from cleavage by blocking access of the protease to the cleavage site. If close proximity of the O-linked polysaccharide is required for protection against cleavage, then moving the site of cleavage by insertion of amino acids between the site of glycosylation and ASHSH would enable cleavage at ASHSH. We expressed a series of mutant hCTR1 proteins in tet-regulated HEK-293 FLp-In T-Rex cells, then purified plasma membranes from each cell line and measured the fraction of each mutant that was cleaved (the 17-kDa fragment) using Western blots as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Fig. 3A shows an example of a Western blot used for quantitation of cleavage in this experiment.

FIGURE 3.

Effect on cleavage of hCTR1 of inserting amino acids between Thr27 and the ASHSH cleavage site. A, example Western blot used to determine the extent of cleavage. The blot was probed with anti-COOH-terminal hCTR1 antibody (6). Plasma membranes (10 μg of protein) from cells expressing: lane 1, wild-type hCTR1; lane 2, AAA mutant hCTR1; lane 3, hCTR1 mutant having a 3-amino acid insertion (CGT) between the O-glycosylation site and ASHSH cleavage site; and lane 4, hCTR1 mutant with a 5-amino acid insertion (CGTGT). B, extent of cleavage of the hCTR1 proteins. The AAA mutant lacking O-glycosylation is shown at top. Wild-type hCTR1 is shown at the bottom. Between are mutants with insertions between Thr27 and the ASHSH cleavage site. Inserted amino acids are boxed in 4 mutants. Error bars represent the S.D. of three to five determinations for each mutant.

We measured cleavage in mutants in which 1, 3, or 5 amino acids were inserted between Thr27 and ASHSH in wild-type hCTR1. In Fig. 3B, the top mutant lacks O-glycosylation (AAA mutant), and is ≈95% cleaved. In contrast, the wild-type protein shown at the bottom is essentially uncleaved. Insertion of amino acids (see boxed residues in Fig. 3B) led to progressively more cleavage at ASHSH. This is consistent with the idea that O-glycosylation prevents proteolytic cleavage at the ASHSH site by virtue of its proximity to the site. However, it was also possible that insertion of amino acids might lower the efficiency of O-glycosylation if the glycosylases responsible required a specific sequence context. In this case, cleavage of the insertion mutants in Fig. 3B might be due to inefficient O-glycosylation. To test this possibility we expressed a mutant having duplication of ASHSH, which maintained the wild-type sequence adjacent to the site of O-glycoslyation, but introduced a new cleavage site away from the site of glycosylation. The ASHSH duplication was cleaved to the same extent as the CGTGT insertion between Thr27 and ASHSH (Fig. 3B). Together, these results supported the hypothesis that the close proximity of O-linked polysaccharides at Thr27 protects ASHSH from cleavage.

Reduction of Cleavage by Deletion and Substitution within ASHSH

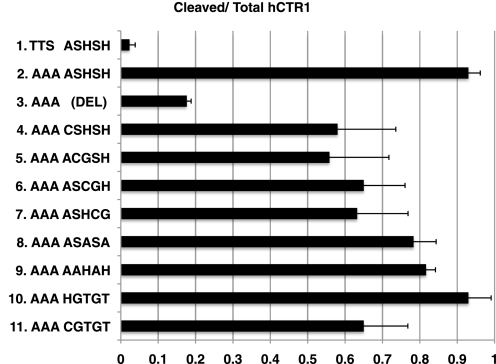

We made a series of mutations within the ASHSH cleavage site to determine which, if any, specific residues are necessary for cleavage (Fig. 4). In each case, the triple alanine substitution at Thr26–Thr27–Ser29 (AAA) was also included, which is ∼95% cleaved when the wild-type ASHSH sequence is present (Fig. 4, mutant 2). A deletion of ASHSH had the greatest effect, reducing the fraction of hCTR1 protein cleaved to 15–20% (Fig. 4, mutant 3, DEL).

FIGURE 4.

Extent of cleavage of hCTR1 mutants within the ASHSH cleavage site. Each mutation in ASHSH has in addition an AAA substitution for the TTS tripeptide that contains the site of O-linked glycosylation in wild-type. Wild-type is shown at the top. Below the wild-type is the AAA mutant with ASHSH (mutant 2). Mutant 3 is a deletion of ASHSH. Mutants 4–11 are various substitutions within the ASHSH cleavage site, as shown, in addition to the AAA mutation. Error bars represent the S.D. of three to six determinations for each mutant.

Other mutants were constructed in which elements of the ASHSH sequence were sequentially substituted with Cys or CG residues (Fig. 4, mutants 4–7). Each substitution resulted in only a modest reduction in cleavage, but no substitution reduced cleavage to the same extent as did deletion of ASHSH. Further substitutions included (in place of ASHSH) ASASA, AAHAH, CGTGT, and HGTGT (Fig. 4, mutants 8–11). Of these substitutions, the most efficiently cleaved was HGTGT (>90%), whereas the least efficiently cleaved was CGTGT (58%). In the deletion mutant lacking ASHSH (mutant 3), the new sequence brought into the position of ASHSH was GGGSS (see Fig. 1). We concluded from these studies that the protease responsible for cleavage does not recognize a discrete amino acid sequence, but cleaves the hCTR1 polypeptide in a specific place with varying efficiency.

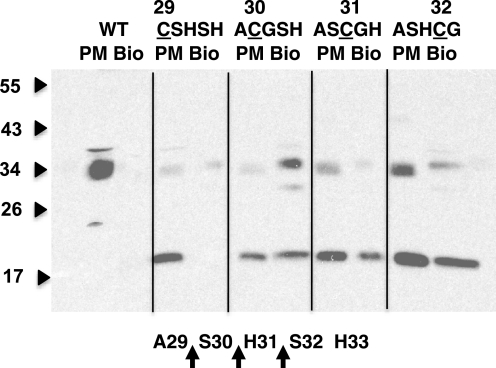

Single Cysteine Labeling Identifies Cleaved Peptide Bonds

We showed previously that the cleaved hCTR1 protein is efficiently delivered to the plasma membrane (17). Because hCTR1 has no surface-exposed cysteines, we used cell surface labeling of cysteine residues to probe the peptide bonds that are cleaved in four single cysteine substitution mutants shown in Fig. 4. Wild-type hCTR1 was a control, because it has no cysteines in the extracellular amino terminus. We labeled HEK-293 cells expressing wild-type or hCTR1 mutants that contained single cysteine residues at positions 29–32 with a cell-impermeant biotin reagent. The cells were lysed and biotinylated proteins were recovered with streptavidin beads. Portions of the same cells expressing mutant or wild-type hCTR1 that were biotinylated were homogenized and fractionated to recover plasma membranes. Plasma membrane and biotinylated samples were run side by side in PAGE for Western blot analysis using anti-hCTR1 COOH terminus antibodies (Fig. 5). Both full-length and 17-kDa hCTR1 polypeptides are recognized by anti-COOH-terminal antibody.

FIGURE 5.

Determination of cleaved peptide bonds. Cells expressing each hCTR1 Cys substitution mutant were biotinylated with a sulfhydryl reagent, lysed, and supernatants were mixed with avidin beads to recover labeled proteins (lanes marked Bio). 10 μg of plasma membrane protein from the same cells was run to the left of each biotinylated sample (PM). The presence of the 17-kDa band in lanes marked Bio indicates cleavage of hCTR1 to the left of the single cysteine in each mutant, as shown below in the diagram. Lines were drawn on the gel image for clarity.

If the truncated hCTR1 17-kDa fragment from a mutant is biotinylated, cleavage must have occurred on the amino-terminal side of the cysteine in that mutant. Cleavage to the carboxyl side of cysteine would separate the cysteine containing peptide from the 17-kDa fragment. The amino-terminal fragment would not be recognized by the COOH-terminal antibody. As shown in Fig. 5, wild-type hCTR1 was not pulled down by streptavidin after biotinylation, as expected (Fig. 5, lanes marked WT). Of four mutants shown in Fig. 5 (Fig. 3, mutants 4–7), all contain some 35-kDa full-length hCTR1 in the streptavidin pull-down lanes, as expected if the introduced cysteines were biotinylated. In addition, the three mutants with Cys at positions 30, 31, and 32 (ACGSH, ASCGH, and ASHCG, respectively) have 17-kDa products in the pull-down lanes (Fig. 5, Bio), showing that cleavage occurred on the amino-terminal side of cysteine at positions 30, 31, and 32. In contrast, no 17-kDa fragment was biotinylated in the mutant CSHSH (Fig. 5, CSHSH lanes), showing that cleavage on the amino-terminal side of the cysteine at position 29 did not occur.

Disrupting the Context of the ASHSH Cleavage Site Does Not Diminish Cleavage

A truncation mutant lacking the first 28 amino acids from hCTR1 (A29) is not O-glycosylated (lacking Thr27), and ∼90% of the mutant hCTR1 protein was cleaved to leave the 17-kDa fragment identical to mutants lacking O-glycosylation (see Fig. 2). The efficient cleavage of this mutant showed that proteolytic cleavage of hCTR1 did not require protease recognition of specific sequences on the amino-terminal side of the cleavage site. To determine whether sequences on the carboxyl side of the ASHSH cleavage site(s) are required for recognition, we expressed mutants having: an 8-amino acid insertion (APARPNAG) between residues Gly34 and Gly35, a 10-amino acid deletion (of SSMMMMPMTF, Ser38–Phe47), or 5 amino acid substitution (AAAAPA for MMMMPM, Met40–Met45), near the ASHSH cleavage site (Fig. 6A, mutants 3–5). Analysis of hCTR1 in plasma membranes showed that all three of these mutants were cleaved to the same extent as the AAA mutant from which they were derived (Fig. 6A, mutant 2 versus mutants 3–5). Fig. 6B shows “17-kDa” fragments from these insertion and deletion mutants (lanes 4 and 5) run alongside the parent AAA mutant, a substitution of ASHSH, and the deletion mutant removing ASHSH (lanes 1–3). The mobility of the mutant fragments in lanes 3–5 reflects the amino acids deleted or inserted. Thus, despite alteration of adjacent sequences on the carboxyl side of the cleavage site, the hCTR1 protein is still efficiently cleaved.

FIGURE 6.

A, cleavage of mutants on the carboxyl side of the ASHSH cleavage site. Rows 1 and 2, wild-type and AAA mutant hCTR1 proteins, respectively; row 3, 8 Ins., the peptide APARPNAG was inserted between G35 and G36 (see Fig. 1); row 4, 10-amino acid del, the peptide SSMMMMPMTF, amino acids 38–47, were deleted in this mutant; row 5, 5-amino acids sub, the methionine cluster MMMMPM (amino acids 40–45) was changed to AAAAPA. Error bars represent the S.D. of three determinations for each mutant. B, the 17-kDa cleavage products of deletion and insertion mutants. Migration of these fragments is altered based on the insertion or loss of amino acids compared with fragments from substitution mutants shown in lanes 1 or 2.

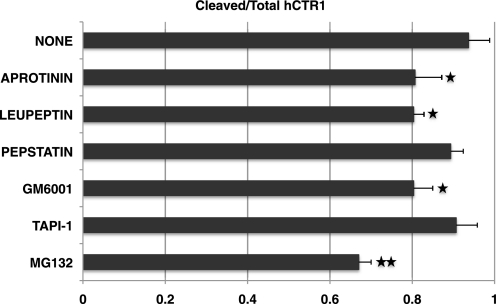

Treatment of Cells Expressing Cleaved hCTR1 with Protease Inhibitors Has Small Effect

We treated cells expressing the hCTR1 AAA mutant with protease inhibitors that have been used to inhibit protease activities in cultured cells (31–35). Six protease inhibitors with various specificities were tested: pepstatin (aspartic protease), leupeptin (serine and cysteine proteases), aprotinin (serine protease), TAPI-1 (matrix metalloprotease inhibitor), GM6001 (broad-spectrum matrix metalloprotease inhibitor), and MG132 (proteasome inhibitor). As shown in Fig. 7, none of the protease inhibitors prevented cleavage, although the serine protease inhibitors somewhat lowered the extent of cleavage, by about 20%, as did GM6001. MG132 at 2 μm reduced cleavage by 33% but killed cells at concentrations of 5 μm or above (35). Inhibition would presumably be most effective on a surface membrane protease, which would be directly accessible to the drugs (19, 36). In addition to the protease inhibitors, we also attempted to inhibit cleavage with a small peptide, Ala-Ser-His-Ser-His-Gly, that matched the protease cleavage site. Cells were incubated with the peptide prior to induction of the mutant hCTR1. The peptide had no inhibitory effect at the concentrations tested (up to 50 μm), nor was it effective when transfected prior to tet induction (5 and 50 μm, data not shown).

FIGURE 7.

Protease inhibitors and hCTR1 cleavage. Cleavage of hCTR1 AAA mutant protein expressed in HEK-293 cells that were exposed to the indicated protease inhibitors during a 48-h tet induction. Concentration of inhibitors used are shown: aprotinin, 100 units/ml; leupeptin, 20 μm; pepstatin, 10 μm; GM6001, 20 μm; TAPI-1, 10 μm; MG132, 2 μm. Higher concentrations of MG132 caused cell death. Error bars represent the S.D. of three to six determinations for each mutant (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, t test).

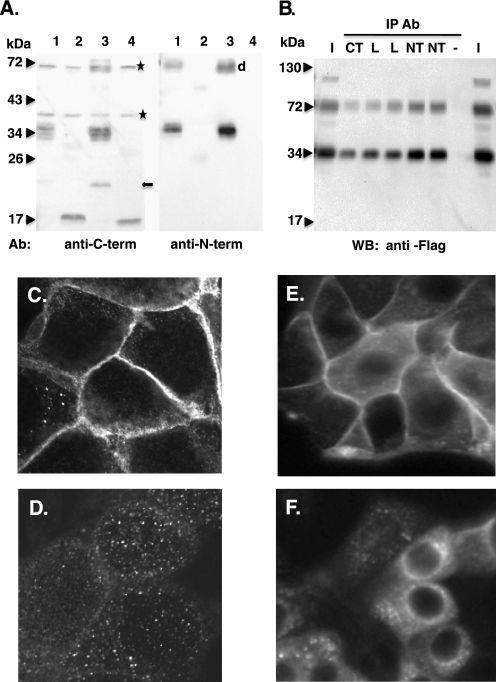

hCTR1 Cleavage Occurs Inside the Cell

Because the wild-type hCTR1 is protected from cleavage protein by O-glycosylation, we assume that when cleavage of hCTR1 occurs, it is after O-glycosylation would normally have taken place in the cis-to-trans golgi stack. This leaves many compartments in which hCTR1 cleavage might occur in the secretory or endocytic pathways. In addition, cleavage could also occur within the plasma membrane.

Using fixed cell and live cell imaging, we sought the hCTR1 amino-terminal peptide in cells expressing wild-type or cleaved hCTR1. Accumulation of signal from the cleaved peptide that differed from wild type would indicate where in the cell cleavage occurred. We developed two new reagents to monitor the amino terminus of hCTR1, in fixed and live cells. We raised an anti-hCTR1 antibody against the amino terminus. As shown in Fig. 8A this antibody (anti-N-term) recognizes proteins in cells expressing overexpressed (full-length) hCTR1 (lanes 1 and 3), but not in cells expressing the 17-kDa cleavage product from hCTR1 lacking O-glycosylation (lane 2) or an amino-terminal truncation of hCTR1 (G34, lane 4). Antibodies against the carboxyl terminus (anti-C-term) recognized all four hCTR1 proteins (Fig. 8A). Immunoprecipitation of solubilized, overexpressed FLAG-tagged hCTR1 with the anti-N-terminal antibodies pulled down the (full-length) hCTR1 protein that was also immunoprecipitated with antibodies raised against the hCTR1 carboxyl terminus or intracellular loop (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Anti-hCTR1 amino-terminal antibody. A, Western blots using anti-hCTR1 antibodies raised against either the amino or carboxyl terminus of hCTR1, as indicated below each blot. 10 μg of plasma membrane protein from cells overexpressing hCTR1 variants were run in each lane. Lane 1, FLAG-tagged WT hCTR1; lane 2, AAA mutant hCTR1 (mostly cleaved); lane 3, WT hCTR1; lane 4, G34, a truncated hCTR1 lacking the first 33 amino acids of hCTR1. *, nonspecific cross-reactive bands. Arrow, proteolytic fragment sometimes observed in wild-type hCTR1 preparations. d, position of dimer form of wild-type. Faint bands in lane 2 are monomer and dimer forms of unglycosylated AAA mutant. B, IP of monomer and dimer forms of FLAG-tagged, overexpressed hCTR1. hCTR1 membrane proteins were precipitated with hCTR1 antibodies raised against the carboxyl terminus (CT), the intracellular loop (L), or the amino terminus (NT). −, no antibody control. Lanes marked I are 50% of input protein amount for each IP. C–F, immunostaining with anti-hCTR1 amino-terminal antibody. MDCK cells expressing wild-type hCTR1 (C) or AAA mutant hCTR1 (D) and HEK-293 cells expressing wild-type (E) or AAA mutant hCTR1 (F) are shown.

The anti amino-terminal hCTR1 antibody was used for immunofluorescence in HEK-293 and MDCK cells expressing either wild-type or a cleaved AAA mutant (e.g. Fig. 8A, lane 2). Two distinct patterns were observed. In cells expressing wild-type protein, most of the signal was confined to the plasma membrane (Fig. 8, C and D). In contrast, in cells expressing the hCTR1 AAA mutant lacking any glycosylation, the signal appeared punctate, and was primarily in the cytoplasm (Fig. 8, E and F). These puncta appeared somewhat larger in HEK-293 cells than in MDCK cells, but in either cell type, they were observed in the cytoplasm of the cell, often localized to one side of the nucleus (Fig. 8, C–F).

Live Cell Imaging of hCTR1-GFP Confirms the Intracellular Site of Cleavage

We also constructed GFP-hCTR1 fusion proteins for live cell imaging. Initial attempts to fuse GFP directly to the amino terminus of hCTR1 failed, possibly because the addition of the 27-kDa GFP moiety prevented insertion of the fusion protein into the endoplasmic reticulum. To overcome this problem, we fused an enhanced green fluorescent protein having the signal cleavage sequence from calreticulin (kindly provided by Dr. S. Shikano, University of Illinois) to the amino termini of wild-type hCTR1 and AAA mutant hCTR1 proteins. This modification allowed the expression of the two GFP-hCTR1 fusion proteins, and did not prevent their delivery to the cell surface.

HEK-293 cells expressing wild-type and AAA mutant GFP-hCTR1 fusion proteins were homogenized and fractionated on 5 step sucrose gradients. Fractions enriched for membranes from the endoplasmic reticulum (E), golgi (G), or plasma membrane (PM) were analyzed using anti-GFP antibodies (Fig. 9A). The apparent mass of the wild-type (O-glycosylated) fusion protein was 50–52 kDa, slightly larger than the non-O-glycosylated AAA mutant, which was 48–49 kDa. Anti-hCTR1-COOH terminus antibodies also detected the same size proteins in plasma membranes recognized by anti-GFP antibodies, as well as 17-kDa fragments resulting from cleavage of the GFP-AAA mutant fusion (Fig. 9A). The cleaved GFP-containing fragment would (presumably) be soluble, and was not recovered in these membrane fractions.

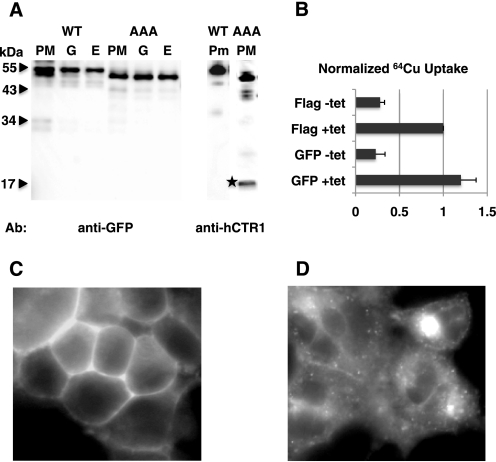

FIGURE 9.

GFP-hCTR1 fusion proteins. A, Western blot analysis of overexpressed GFP-hCTR1 fusion proteins. Cells expressing either GFP-WT hCTR1 fusion protein or AAA mutant fusion were fractionated, and membranes enriched for endoplasmic reticulum (E), golgi (G), or plasma membranes (PM) were probed with anti-GFP antibodies (left panel). Plasma membrane fractions were also probed with anti-COOH-terminal hCTR1 antibody on the right. The two lanes shown are from the same gel. The star shows the 17-kDa cleavage product. B, 64Cu uptake in cells expressing tet-regulated FLAG-tagged wild-type hCTR1 or GFP-tagged hCTR1. Values are normalized to tet-induced FLAG-tagged hCTR1 to correct for differences in expression. Shown are the averages of three uptake experiments, with error bars showing S.D. C, live cell image of HEK-293 cells expressing a GFP-hCTR1 wild-type fusion protein; D, live cell image of HEK-293 cells expressing a GFP-hCTR1 AAA mutant fusion protein.

To ensure that the GFP-hCTR1 fusion was folded correctly and functioned normally, we tested the ability of the GFP-hCTR1 to transport copper in 64Cu uptake assays. Cells expressing the GFP-hCTR1 fusion (wild type hCTR1 protein) had slightly higher levels of copper uptake than did FLAG-tagged hCTR1 (Fig. 9B), showing that the wild-type GFP-hCTR1 fusion protein can still function in copper transport, and that, despite the doubling of the mass of the protein by the addition of GFP, it is still appropriately folded.

HEK-293 cells expressing the GFP fusion proteins were imaged after tet induction. Cells expressing wild-type GFP-hCTR1 contained strong plasma membrane-associated staining (Fig. 9C), similar to what we observed in formaldehyde-fixed cells expressing wild-type hCTR1. In contrast to the wild-type fusion, cells expressing the (cleaved) AAA mutant GFP-hCTR1 fusion protein had little membrane fluorescence, but predominantly intracellular staining of membranes and puncta (Fig. 9D). These results provided clear evidence that the cleaved hCTR1 amino terminus is retained in a compartment inside the cell.

Double Labeling Shows Localization of hCTR1 Cleavage in the Late Endosome

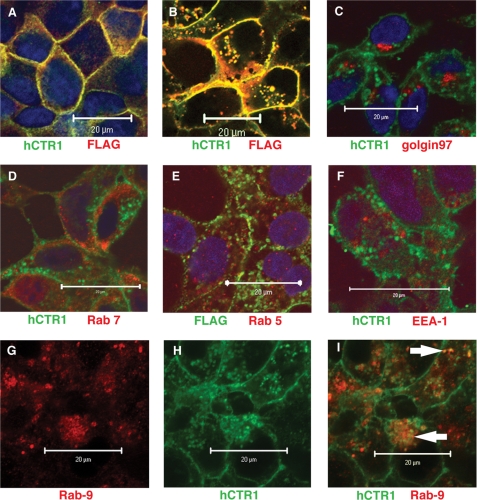

The AAA hCTR1 mutant that is 95% cleaved contains a FLAG tag at the amino terminus, adjacent to the sequence used to raise the anti-amino-terminal antibody (Fig. 1). We used a mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody in conjunction with the (rabbit) anti-amino-terminal antibody to compare the overlap of the signals from the two antibodies, which should be very similar. As expected, the two antibodies showed near complete overlap (yellow staining) in cells expressing either wild-type hCTR1 (Fig. 10A) or hCTR1 AAA mutants (Fig. 10B). These results validated that the puncta seen in AAA mutant cells represented the location of the cleaved amino terminus, as well as a control for the specificity of the hCTR1 antibody.

FIGURE 10.

Double labeling immunofluorescence with anti-hCTR1 (or anti-FLAG) and organelle marker antibodies. A, HEK-293 and MDCK cells expressing wild-type hCTR1 and B, HEK-293 cells expressing AAA mutant hCTR1 co-stained with anti-amino-terminal hCTR1 antibody and anti-FLAG antibody. C–F, HEK-293 cells expressing AAA mutant hCTR1. In each panel, anti-hCTR1 (or anti-FLAG in E) is in green, whereas organelle-specific antibodies are in red. Organelle-specific antibodies are: C, golgin97 (cis, medial golgi); D, Rab7, (early, late endosome); E, Rab5 (early endosome, recycling endosome, plasma membrane); and F, EEA-1 (early endosome). G–I, HEK-293 cells expressing AAA mutant hCTR1 stained with: Rab9 (G) (late endosome, in red), anti-hCTR1 (H) in green, and merged images (I). White arrows in I show the overlap in yellow. Scale bars, 20 μm.

To identify the cellular compartment(s) that were stained by the anti-hCTR1 amino-terminal antibody or anti-FLAG antibody in HEK-293 cells expressing the AAA mutant, we used one or the other in combination with antibodies specific for a number of compartments/organelles between the golgi and plasma membrane. As shown in Fig. 10, C–F, we did not see significant overlap in staining from the hCTR1 puncta and various marker antibodies (specificity in parentheses): C was golgin 97 (cis-medial golgi stack), D was Rab7 (early-late endosome), E was Rab5 (early endosome, recycling endosome, plasma membrane), and F was EEA-1 (early endosome). We did observe overlap with Rab9, a marker of the late endosome (Fig. 10, G–I). The Rab9 overlap with hCTR1 was incomplete, but consistently observed (Fig. 10I, white arrows). Some overlay with Rab5 was also observed, but it was confined to the plasma membrane, presumably overlapping with uncleaved hCTR1.

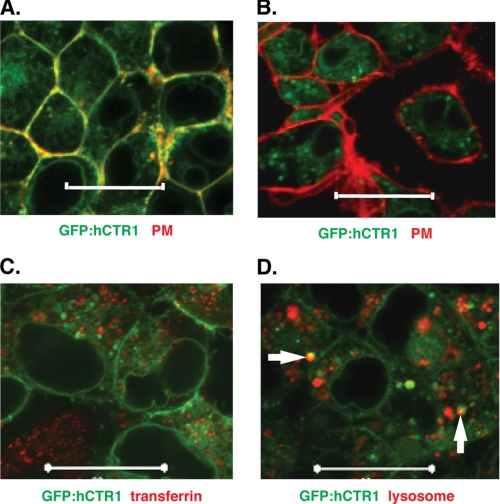

We also labeled HEK-293 cells expressing GFP-hCTR1 wild-type or AAA mutant proteins with compounds that specifically labeled the plasma membrane, the early (recycling) endosome, and lysosomes. As shown in Fig. 11, A and B, the plasma membrane dye colocalized strongly with the wild-type hCTR1 protein (yellow color), but not with the (cleaved) AAA mutant protein. When cells expressing the AAA mutant GFP-hCTR1 fusion were co-labeled with a lysosome-specific dye, some overlap was observed (Fig 11D, white arows). In contrast, no overlap in staining was seen with labeled, endocytosed transferring, a marker for early endosomes (Fig. 11C).

FIGURE 11.

Live cell imaging of GFP-hCTR1 fusion proteins with cell markers. A, GFP-hCTR1 wild-type fusion expressed in HEK-293 cells stained with plasma membrane dye, in red; B, GFP-hCTR1 AAA mutant fusion protein with plasma membrane dye; C, GFP-hCTR1 AAA mutant fusion protein in cells labeled with (endocytosed) fluorescent transferrin; D, GFP-hCTR1 AAA mutant fusion protein in cells labeled with a lysosome-specific stain. White arrows indicate overlap between the GFP and lysosome, stained in yellow. Scale bars, 20 μm.

These studies showed that the cleaved glycoprotein accumulates in punctate structures having some overlap with Rab9. The cleaved GFP-hCTR1 amino-terminal protein showed partial overlap with lysosomes in living cells. It thus appears that proteolytic cleavage of the hCTR1 protein occurs in the late golgi or late endosome, after which the cleaved portion may be targeted to lysosomes for degradation.

DISCUSSION

We have investigated the proteolytic cleavage of hCTR1 that occurs in the absence of O-glycosylation at Thr27. Cleavage takes place within amino acids 29–33 (the peptide ASHSH), preferentially between Ala29, Ser30, and His31. The proximity of the O-linked polysaccharide at Thr27 protects this site from cleavage in wild-type hCTR1. The cleavage takes place when hCTR1 is en route to the plasma membrane in the in puncate structures that have overlap with Rab9, a marker for the late endosome (39).

Glycosylation Prevents Protease Access

We found that the proximity of the O-linked polysaccharide at Thr27 prevents cleavage within the ASHSH peptide (hCTR1 amino acids 29–33). Insertion of amino acids between (O-glycosylated) Thr27 and ASHSH allowed cleavage of hCTR1. Furthermore, a duplication of ASHSH also led to cleavage, ruling out the possibility that the 3 insertion mutants simply inhibited glycosylation by changing the sequence adjacent to the Thr27 residue. We conclude that O-glycosylation at Thr27 inhibits proteolysis by blocking protease access to the cleavage site.

Protease Site Specificity and Specific Peptide Bonds Cleaved in hCTR1

We examined the consequences of disrupting the ASHSH site. Deletion of the site had the greatest effect, reducing cleavage from 95 to about 20% (Fig. 3, mutant 3). Various substitutions reduced the level of cleavage, but none eliminated cleavage. Removing both serines or both histidines had only a modest effect. Thus, neither the ASHSH sequence itself nor the exact position of the sequence are essential to allow cleavage. In the deletion of ASHSH, for example, the 15–20% of hCTR1 protein that is cleaved migrates faster than 17-kDa fragments from the AAA mutant hCTR1, because it has 5 amino acids deleted (see Fig. 6B). This protein must be cleaved in the sequence adjacent to ASHSH, which changes both the sequence cleaved (to GGGDS) and its relative position in the hCTR1 polypeptide.

We used single cysteine substitution mutants in the ASHSH sequence to determine which peptide bonds were cleaved. We labeled cells expressing mutant hCTR1 proteins with single cysteine substitutions in the ASHSH sequence using a cell-impermeable biotin reagent (hCTR1 has no accessible extracellular cysteines). 17-kDa fragments from mutants with cysteine in positions 30–32 were labeled efficiently, whereas a cysteine in position 29 was not (Fig. 5). This showed that cleavage could take place on the amino-terminal sides of Ser30, His31, and Ser32 but not on the amino-terminal side of A29 (see Fig. 5, bottom).

The G34 truncation mutant lacks the first 33 amino acids of hCTR1, and it contains an initiator methionine. G34 migrates slightly faster than do the 17-kDa fragments that result from proteolytic cleavage of intact hCTR1 (Fig. 8A, lane 2 versus 4). This implies that the 17 kDa contains 1 or 2 more amino acids than does G34, which lacks 32 amino acids compared with wild-type hCTR1. Thus, based on the relative migration of the two proteins, the likely cleavage site(s) are between residues 29 and 30, or 30 and 31.

The protective polysaccharide linked to Thr27 is likely to have only short-range steric effects. O-Glycosylation of hCTR1 adds only 1–2 kDa (Fig. 2). Because “mucin-type” O-linked polysaccharides generally have only 5 or 6 monomer sugars and a single branch point (23), it seems likely that the protective shielding from the glycan would only extend for a few amino acids in the polypeptide. Together, the cysteine labeling pattern of cleaved fragments, the size of the polysaccharide, and the relative migration of the G34 truncation mutant versus the 17-kDa fragment place the site of cleavage in vivo between residues 30 and 32, very close to the site of O-glycosylation. This protection against cleavage is similar to a protective role played by O-glycosylated Thr104 in the transferrin receptor (37).

The lack of specificity of the amino acids that can be cleaved in positions 29–33 (Fig. 4) suggests that the relative position of the cleavage site within the structure of hCTR1 is the key determinant for the protease. We imagine that a protease would recognize and interact with hCTR1, then cleave at a peptide bond or bonds based on their geometry relative to the protease active site, unless the site(s) were shielded by O-linked glycosylation. Because truncation A29 is efficiently cleaved to yield the same 17-kDa fragment seen in unglycosylated mutants (Fig. 1) it seems that the hCTR1 polypeptide on the amino-terminal side of the ASHSH cleavage site is not necessary for recognition by the putative protease. We also disrupted the polypeptide on the carboxyl side of ASHSH with insertion, deletion, and substitution mutants (see Fig. 6, mutants 3–5). Surprisingly, none of these mutations affected cleavage. Thus, within the context of the changes we tested, which affected amino acids up to position 45, neither deleting nor changing amino acid sequences on either side of the cleavage site reduced the efficiency of cleavage, nor did most changes to the cleavage site itself.

The Mechanism of and Protease Responsible for hCTR1 Cleavage

Given the efficiency of cleavage of hCTR1 lacking O-linked sugars at Thr27, it seems likely that there is a specific interaction between a protease and the homotrimeric hCTR1 copper transporter. Specific interaction between hCTR1 and the protease could be achieved by recognition of the membrane spanning domains, which would not be affected by changes in the amino terminus that we made in various mutants. Alternatively, an intermediary protein might interact with hCTR1 and position a protease near the cleavage site, such as a protein involved in sorting of vesicular membrane “cargo” proteins during transit to the plasma membrane (38, 39).

The sequence ASHSH within the hCTR1 amino terminus does not contain currently recognized protease cleavage sites as judged using available algorithms (40). It could be that the geometry of the cleavage site creates a susceptible conformation for a protease (41). We considered the possibility that hCTR1 might undergo some form of autoproteolysis involving a catalytic triad (42), given the abundance of serine, histidine residues, and a nearby aspartic acid residue close to the cleavage site. A substitution mutant was made in which the only nearby Asp residue (Asp37) was changed to Ala in the AAA fully cleaved hCTR1 mutant. This double mutant was cleaved to the same extent as the AAA mutant alone (data not shown). The two other Asp residues (Asp2 and Asp13) in the amino terminus are deleted in the A29 truncation mutant protein that is largely cleaved (Fig. 2), making the suggestion of a Ser-His-Asp catalytic triad unlikely to be correct.

It is worth noting that MG132, an inhibitor of the proteasome, had the only notable effect in inhibiting hCTR1 cleavage among the six protease inhibitors (see Fig. 7). In addition, the only algorithm that identified the ASHSH cleavage sequence as a possible protease cleavage site was developed to predict proteasome cleavage susceptibility (46). However, given the multiplicity of proteins that may themselves be regulated by proteasome activity, the modest effect on hCTR1 cleavage by proteasome inhibition could well be indirect.

Cellular Location of Cleavage

Our imaging studies show that cleavage occurs prior to the delivery of the hCTR1 transporter to the plasma membrane. Immunofluorescence studies show that in fixed cells, the cleaved peptide accumulates in punctate structures with some overlap with puncta stained by Rab9, a marker known to stain late endosome compartments (39, 47) (see Fig. 10, G–I). Similar punctate staining was also seen in living cells expressing a mutant GFP-hCTR1 fusion protein that was susceptible to cleavage. In living cells, the puncta are not co-localized with recently endocytosed transferrin, but overlap to some extent with lysosomal compartments (Fig. 11).

From our previous work, we know that the truncated, 17-kDa hCTR1 complex is efficiently delivered to the plasma membrane (17). In contrast, the cleaved amino-terminal glycopeptides are most likely sent to lysosomes for degradation, given the partial overlap we see in living cells between stained lysosomes and the cleaved GFP-hCTR1 fusion protein (Fig. 11D). Although protease cleavage of plasma membrane proteins involving recycling pathways between the plasma membrane and interior compartments have been described (25, 27, 28), our experiments strongly suggest that cleavage of hCTR1 lacking O-linked glycosylation occurs in a late endosomal compartment by an unidentified protease, prior to delivery to the plasma membrane. Numerous candidate proteases exist in the secretory pathway (43–45).

Role of hCTR1 Amino Terminus

The function of the 31–33 amino acids removed from the hCTR1 copper transporter by cleavage is not yet clear. We showed that the overexpressed, cleaved (truncated) transporter had about 50% of the 64Cu uptake activity of the wild-type overexpressed hCTR1. We also observed a similar, reduced level of uptake in the G34 truncation mutant that lacks the first 33 amino acids of hCTR1.3 Although the reduction in 64Cu uptake in tissue culture cells is significant, the loss of the amino terminus in vivo may be a more severe defect (18). In vivo, copper in the bloodstream is bound to various proteins (2, 48), which may require intact amino termini in the homotrimeric hCTR1 complex for efficient copper delivery to the complex prior to transport.

Alternatively, the amino terminus may play some role in maintaining or stabilizing a complex, such as that discovered in Xenopus embryos that contain xCTR1, a kinase, and fibroblast growth factor (16). This study showed that the roles of xCTR1 in Xenopus development and mCtr1 in −/− mouse ES cells appear to be separate from copper transport. Preventing the loss of the amino terminus, by cleavage, might thus be important in functions other than copper transport. Regulated loss of O-glycosylation, (regulated cleavage), could also be used to modify the function of hCTR1 in certain tissues or times during development.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sojin Shikano for the gift of enhanced green fluorescent protein fused to the calreticulin signal sequence, and members of the Kaplan Lab for helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 GM 067166 (to J. H. K.).

E. B. Maryon and J. H. Kaplan, unpublished result.

- hCTR1

- human copper transporter 1

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- HEK-293

- human embryonic kidney 293

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- MDCK

- Madin-Darby canine kidney

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified essential medium

- CAPS

- 3-(cyclohexylamino)propanesulfonic acid

- WT

- wild-type

REFERENCES

- 1.Petris M. J. (2004) Pflugers Arch. 447, 752–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linder M. C., Wooten L., Cerveza P., Cotton S., Shulze R., Lomeli N. (1998) Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 67, Suppl. 5, 965S–971S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maryon E. B., Molloy S. A., Zimnicka A. M., Kaplan J. H. (2007) Biometals 20, 355–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim B. E., Nevitt T., Thiele D. J. (2008) Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 176–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huffman D. L., O'Halloran T. V. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 677–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisses J. F., Kaplan J. H. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29162–29171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J., Peña M. M., Nose Y., Thiele D. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4380–4387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aller S. G., Unger V. M. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3627–3632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Feo C. J., Aller S. G., Siluvai G. S., Blackburn N. J., Unger V. M. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4237–4242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou B., Gitschier J. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 7481–7486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J., Prohaska J. R., Thiele D. J. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 6842–6847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puig S., Lee J., Lau M., Thiele D. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 26021–26030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aller S. G., Eng E. T., De Feo C. J., Unger V. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 53435–53441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisses J. F., Kaplan J. H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 37159–37168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petris M. J., Smith K., Lee J., Thiele D. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9639–9646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haremaki T., Fraser S. T., Kuo Y. M., Baron M. H., Weinstein D. C. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 12029–12034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maryon E. B., Molloy S. A., Kaplan J. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20376–20387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou A., Webb G., Zhu X., Steiner D. F. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 20745–20748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koo B. H., Longpré J. M., Somerville R. P., Alexander J. P., Leduc R., Apte S. S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12485–12494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seidah N. G., Khatib A. M., Prat A. (2006) Biol. Chem. 387, 871–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikolajczyk J., Drag M., Békés M., Cao J. T., Ronai Z., Salvesen G. S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26217–26224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puente X. S., Sánchez L. M., Gutiérrez-Fernández A., Velasco G., López-Otín C. (2005) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33, 331–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van den Steen P., Rudd P. M., Dwek R. A., Opdenakker G. (1998) Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 33, 151–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vey M., Schäfer W., Berghöfer S., Klenk H. D., Garten W. (1994) J. Cell Biol. 127, 1829–1842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rutledge E. A., Green F. A., Enns C. A. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 31864–31868 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown C. L., Meise K. S., Plowman G. D., Coffey R. J., Dempsey P. J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 17258–17268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kambe T., Andrews G. K. (2009) Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 129–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maxson J. E., Enns C. A., Zhang A. S. (2009) Blood 113, 1786–1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradford M. M. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuo M., Sakurai H., Ueno Y., Ohtani O., Saiki I. (2006) Cancer Sci. 97, 155–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamada T., Liepnieks J., Benson M. D., Kluve-Beckerman B. (1996) J. Immunol. 157, 901–907 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taub M. E., Shen W. C. (1993) J. Cell Sci. 106, 1313–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Momiyama J., Hashimoto T., Matsubara A., Futai K., Namba A., Shinkawa H. (2006) Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 209, 89–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin K. I., Baraban J. M., Ratan R. R. (1998) Cell Death Differ. 5, 577–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iijima R., Yamaguchi S., Homma K., Natori S. (1999) J. Biochem. 126, 912–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutledge E. A., Root B. J., Lucas J. J., Enns C. A. (1994) Blood 83, 580–586 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNiven M. A., Thompson H. M. (2006) Science 313, 1591–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seabra M. C., Mules E. H., Hume A. N. (2002) Trends Mol. Med. 8, 23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M. R., Appel R. D., Bairoch A. (2005) in The Proteomics Protocols Handbook ( Walker J. M. ed) pp. 571–698, Humana Press Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lauer-Fields J. L., Minond D., Sritharan T., Kashiwagi M., Nagase H., Fields G. B. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 142–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dodson G., Wlodawer A. (1998) Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 347–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bass J., Turck C., Rouard M., Steiner D. F. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 11905–11909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Springman E. B., Angleton E. L., Birkedal-Hansen H., Van Wart H. E. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 364–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bergin D. A., Greene C. M., Sterchi E. E., Kenna C., Geraghty P., Belaaouaj A., Taggart C. C., O'Neill S. J., McElvaney N. G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31736–31744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keşmir C., Nussbaum A. K., Schild H., Detours V., Brunak S. (2002) Protein Eng. 15, 287–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ganley I. G., Carroll K., Bittova L., Pfeffer S. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 5420–5430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cabrera A., Alonzo E., Sauble E., Chu Y. L., Nguyen D., Linder M. C., Sato D. S., Mason A. Z. (2008) Biometals 21, 525–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]