Abstract

The sarco-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a (SERCA2a) is critical for sequestering cytosolic calcium into the sarco-endoplasmic reticulum (SR) and regulating cardiac muscle relaxation. Protein-protein interactions indicated that it exists in complex with Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) and its anchoring protein αKAP. Confocal imaging of isolated cardiomyocytes revealed the colocalization of CAMKII and αKAP with SERCA2a at the SR. Deletion analysis indicated that SERCA2a and CaMKII bind to different regions in the association domain of αKAP but not with each other. Although deletion of the putative N-terminal hydrophobic amino acid stretch in αKAP prevented its membrane targeting, it did not influence binding to SERCA2a or CaMKII. Both CaMKIIδC and the novel CaMKIIβ4 isoforms were found to exist in complex with αKAP and SERCA2a at the SR and were able to phosphorylate Thr-17 on phospholamban (PLN), an accessory subunit and known regulator of SERCA2a activity. Interestingly, the presence of αKAP was also found to significantly modulate the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation of Thr-17 on PLN. These data demonstrate that αKAP exhibits a novel interaction with SERCA2a and may serve to spatially position CaMKII isoforms at the SR and to uniquely modulate the phosphorylation of PLN.

The phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycle is critical for controlling a diverse series of signaling processes in cell biology (1, 2). Specificity of the phosphorylation/dephosphorylation event is in part achieved by selective employment of a protein kinase/phosphatase cascade and subcellular targeting (1, 2). Both spatial and temporal specificity of signaling events is achieved by the compartmentalization of the signaling complexes through adaptor or anchoring proteins (1, 2). Recent studies have highlighted novel aspects of integrating spatially and temporally the cAMP signaling cascades via a diverse family of protein kinase A anchoring proteins (AKAPs)2 (3). The AKAPs are responsible for positioning the signaling complex via protein-protein interactions for effective and time-sensitive compartmentalization of the cAMP signal (4).

Although the intracellular targeting of protein kinase A to the effectors is being unraveled, little is known about the targeting of CaMKII activity, which is ubiquitously expressed and serves important roles in calcium signaling to guide synaptic transmission (2, 5, 6), gene transcription (7), cell growth (8), and excitation-contraction coupling (9–11). Although four different isoforms of CaMKII (α, β, δ, and γ) are expressed in a tissue-specific manner, cardiac tissue is shown to have predominance of CaMKIIδC (cytosolic) and CaMKIIδB (nuclear) isoforms, which serve roles in excitation-contraction coupling and cell growth, respectively (7, 12). Studies have also revealed a significant level of a muscle-specific CaMKII β isoform (CaMKIIβ4) in skeletal and cardiac muscle (11, 13–15). In addition, the CAMK2A gene that encodes CaMKIIα kinase in brain expresses an alternatively spliced non-kinase polypeptide designated αKAP in cardiac and skeletal muscle (14–16). The αKAP has a unique amino acid stretch at the N terminus, which encodes a putative transmembrane domain, followed by the association domain of CaMKIIα. The association domain in the CaMKII gene family is a common feature important for oligomerization (15–17).

αKAP is believed to be targeted to the SR membrane in skeletal muscle via the N-terminal hydrophobic sequence and has been proposed to recruit the muscle-specific CaMKIIβ4 through dimerization with the association domain and regulate calcium transport (15). Data also suggest that αKAP along with the novel CaMKIIβ4 are enriched in cardiac SR membranes implying a common regulatory role for these molecules in these two muscle types (13–15). Further, studies suggest a significant level of a muscle-specific CaMKII β isoform (CaMKIIβ4) in cardiac and skeletal muscle (14–16). In addition, the CAMK2A gene that encodes CaMKIIα kinase in the brain expresses an alternatively spliced non-kinase polypeptide designated αKAP in cardiac and skeletal muscle (14–16). The αKAP has a unique amino acid stretch at the N terminus, which encodes a putative transmembrane domain, followed by the association domain of CaMKIIα. The association domain in the CaMKII gene family is a common feature important for oligomerization (15–17).

αKAP is believed to be targeted to the SR membrane in skeletal muscle via the N-terminal hydrophobic sequence and has been proposed to recruit the muscle-specific CaMKIIβ4 through dimerization with the association domain and regulate SR function (15). Data also suggest that αKAP along with the novel CaMKIIβ4 are enriched in cardiac SR membranes, implying a common regulatory role for these molecules in these two muscle types (13–15). Further, studies suggest that CaMKIIβ4 can recruit the glycolytic machinery to the SR membrane in cardiac and skeletal muscle and potentially serve to spatially modulate the supply of ATP for the calcium transport process (13, 14). In view of the emerging concept of spatial and temporal control of signal transduction through kinase-anchoring proteins, we investigated further the role of αKAP at the SR membrane and found that it directly interacts with the calcium ATPase and serves to recruit CaMKII isoforms and modulate the phosphorylation of PLN at Thr-17, which is known to critically regulate calcium uptake and muscle relaxation (18). We propose a model in which αKAP would serve to modulate PLN phosphorylation and integrate the spatial and temporal control on calcium transport through direct binding to the calcium ATPase on the one hand and recruitment of CaMKII activity on the other.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression Constructs of CaMKIIδC, CaMKIIβC, αKAP, SERCA2a, and Phospholamban

The cloning of CaMKIIβ4 and αKAP from myocardium has been described previously (14). These constructs were subcloned in frame either into pcDNA3-six-Myc, pcDNA3-GFP, or pGEX-2TK. SERCA2a, CaMKIIδC, and PLN were cloned by reverse transcription-PCR. In brief, total RNA was extracted from a mouse heart using the Tripure isolation kit (Roche Applied Science). First strand cDNA was obtained using oligo(dT) primer and reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Specific primers were designed for SERCA2a, CaMKIIδC, and phospholamban. PCR was performed using cDNA as a template and Platinum PCR SuperMix (Invitrogen). The PCR products were cloned into either pcDNA3-six-Myc, pcDNA3-GFP, or pGEX-2TK and sequenced by an automated ABI sequencer using M13 and T7 sequencing primers, and sequences were analyzed with Seqaid II (University of Kansas) and BLAST.

Cell Culture and Transfection

HeLa cells were maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transfection was performed with FuGENE-HD (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primary culture of mouse cardiomyocytes was carried out following the isolation procedure described (19). Hearts from neonatal mice were washed with suspension minimum essential medium (Invitrogen), sliced into small pieces with scissors, and transferred into a cell dispenser containing 0.1% trypsin at 37 °C. Enzymatic treatment was allowed for 30 min, and the yielded cells were spun down and collected in Hanks minimum essential medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum. Enzymatic digestion was repeated three more times, and isolated cells were cultured on dishes. After 50 min of plating, the non-adherent cells, mostly consisting of cardiomyocytes, were transferred onto new dishes, and this procedure was repeated three more times to enrich for cardiomyocytes.

GST Fusion Protein Expression

Escherichia coli BL21 containing recombinant proteins were shaken in a special medium (Peptone 20, yeast extract 10, and NaCl, 7 g/liter) at 37 °C. When the A595 reached 0.5, the temperature was cooled to 28 °C, and cells were induced by 0.1 mm 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside and maintained at 28 °C for 4 h. Then cells were pelleted by centrifugation and lysed by sonication in phosphate-buffered saline buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40. Debris was removed by centrifugation, and supernatant was saved. The fusion proteins were isolated on glutathione-Sepharose beads 4B (GE Healthcare) by incubating the lysate for 60 min and then washed four times with the same buffer.

GST Pull-down and Calmodulin Binding

Mouse hearts were homogenized with TBS buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm EDTA). The homogenate was centrifuged at 7500 × g for 20 min, and supernatant was transferred to new tubes and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C and considered as the crude SR fraction. The latter was solubilized with 0.5% Nonidet P-40 and 0.8% CHAPS for 2 h at 4 °C and centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 × g, and the supernatant was retained as solubilized SR. For GST pull-down assays, GST alone and GST-αKAP fusion proteins (10 μg) were incubated with solubilized SR fraction (500 μg) in 1 ml of TBS buffer for 2 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed four times in TBS buffer, 2× gel loading buffer was added, and bound proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. For isolation of CaM-binding proteins, detergent-solubilized SR fraction (500 μg) was applied to a CaM-Sepharose column in the presence of 2 mm CaCl2 and then washed with four volumes of buffer before elution with 5 mm EGTA in the same buffer but without CaCl2 (20). Protein samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and immunoblotted with different antibodies or stained with Coomassie Blue or silver stain to visualize protein bands that were further sequenced by liquid chromatography-MS/MS analysis (LTQ) at the Proteomics Resource Centre at the University of Ottawa. Protein samples were also analyzed by MALDI-TOF techniques at the proteomics facility at Queens University.

Immunofluorescence

Cells transfected with different cDNA expression constructs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and then washed four times with phosphate-buffered saline. These were incubated with anti-Myc antibody (Sigma) for 2 h, washed four times, and then incubated with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 594; Invitrogen) for 40 min, washed four times, and mounted in Vectashield mounting medium. The cells were observed under a Zeiss LSM 500 confocal laser-scanning system attached to a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss). Cardiomyocytes were fixed in a similar manner as above; immunostained with anti-CaMKIIβ, anti-αKAP, and anti-SERCA2a antibodies; and analyzed by confocal microscopy.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) Assays

IP assay was carried out using c-Myc-agarose (catalog number A7470; Sigma) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells transfected in a 10-cm culture dish were scraped and lysed in TBS buffer. The resulting lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, and protein was measured by a Bradford kit (Bio-Rad). Myc-agarose and IgG-agarose beads (control) were washed four times with TBS buffer, and 250 μg of cell lysate was incubated with 50 μl of washed Myc-agarose beads. The mixture was centrifuged at 4 °C for 60 min, and beads were collected and washed (four times) with 1 ml of cold TBS buffer for 10 min each time. The precipitated proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and immunoblotted with different antibodies as described above.

Deletion Mutations

Deletion constructs of αKAP were constructed with PCR using selected primers in which a stop codon (TGA) was introduced at the desired locations of the αKAP sequence. The PCR products generated were inserted into pcDNA3-six-Myc or pcDNA3-GFP and sequenced as described above to confirm identity.

Phosphorylation Assays

Phosphorylation of SERCA2a was carried out by co-transfecting SERCA2a-GFP and αKAP-Myc with either CaMKIIδC-Myc or CaMKIIβ4-Myc. IP reactions were performed with Myc-agarose as described above, and precipitated proteins were incubated in assay buffer (20 mm MOPS, pH 7.2, 25 mm β-glycerol phosphate, 1 mm sodium orthovandate, 1 mm dithiothreitol, either 1 mm CaCl2 plus 100 nm calmodulin or 5 mm EGTA, and [γ-32P]ATP (0.4 × 10−5 cpm)) for 2 min at room temperature; the reaction was terminated with 50 μl of SDS gel loading buffer; proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE and gel-dried; and phosphoproteins were detected on x-ray films.

Phosphorylation of PLN was studied in the presence or absence of purified αKAP-GST (10 μg). In brief, purified GST-PLN (20 μg) was incubated with either GST-CaMKIIδC or GST-CMKIIβ4 (10 μg). The control reactions include GST alone (20 μg) instead of GST-PLN. The mixture of proteins was incubated in the phosphorylation assay buffer (as above except that hot ATP was replaced with cold ATP) for 2 min at 30 °C and then terminated with 50 μl of SDS gel loading buffer. Proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and immunoblotted with anti-CaMKII polyclonal antibody or phospho-PLN antibody (Badrilla, UK) or anti-PLN antibody (Affinity Bioreagent).

RESULTS

αKAP Exists in a Complex with SERCA2a

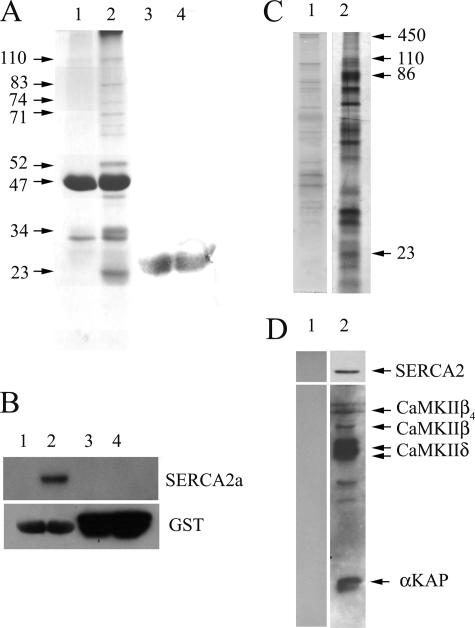

Previous data have shown that αKAP is a component of the SR membrane in skeletal and cardiac muscle (13–15). In order to define interacting components of αKAP, GST pull-down assays were performed with a detergent-solubilized SR fraction from cardiac muscle. The potential interacting proteins were revealed with Coomassie Blue staining. Characterization of the interacting proteins with respect to molecular mass revealed that αKAP specifically binds polypeptides of ∼110, 86, 83, 74, 71, 52, 34, and 23 kDa (Fig. 1A, lane 2). The presence of these polypeptides was not detected in the pull down with GST alone (Fig. 1A, lane 4). Further, recombinant GST-αKAP (Fig. 1A, lane 1) or GST alone (Fig. 1A, lane 3) in TBS buffer also lacked the presence of these polypeptides. The recombinant GST-αKAP appeared as a 47-kDa form (mature form) and a 32-kDa truncated product (lanes 1 and 2), and GST alone appeared as 25 kDa on SDS gels (lanes 3 and 4).

FIGURE 1.

SERCA2a, αKAP, CaM, and CaMKII complex in SR. A, GST alone or GST-αKAP fusion proteins (10 μg) were incubated with solubilized cardiac SR fraction (500 μg). Bound proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. A, lane 1, GST-αKAP in TBS buffer; lane 2, GST-αKAP pull-down of solubilized SR; lane 3, GST alone in TBS buffer; lane 4, GST alone pull-down of solubilized SR. B, pull-down assay of GST alone and GST-αKAP was obtained as described in A. Bound proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and immunostained with anti-SERCA2a antibody (top) or anti-GST antibodies (bottom). B, lane 1, GST-αKAP in TBS buffer; lane 2, GST-αKAP-bound proteins; lane 3, GST alone in TBS buffer; lane 4, GST alone-bound proteins. C, solubilized SR fraction (500 μg) was applied on both Sepharose (lane 1) and CaM-Sepharose (lane 2) columns, and proteins were eluted with 5 mm EGTA, resolved on SDS-PAGE, and silver-stained. D, Sepharose- and CaM-Sepharose-bound proteins as described in C were resolved on SDS-PAGE, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and immunostained with anti-SERCA2a antibody (top) or anti-CaM kinase II antibodies (bottom). The data are typical of five experiments.

In order to identify the specifically bound polypeptides, gel bands were excised and sequenced and analyzed by liquid chromatography-MS/MS. This revealed that αKAP exists in complex with a diverse array of proteins (Table 1), including aralar, aconitase 2, acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase, hydroxyacyl-Coenzyme A dehydrogenase, SERCA2a, CaMKII, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Since CaMKII, αKAP, and SERCA2a are enriched in the SR, we further investigated their potential interactions. The GST pull-down experiments noted above were repeated, and the polypeptides present were probed in immunoblots with an anti-SERCA2a monoclonal antibody, which clearly identified a 110-kDa polypeptide in the GST-αKAP pull-down (Fig. 1B, top, lane 2) and not in the GST-alone pull-down (Fig. 1B, top, lane 4). GST-αKAP (Fig. 1B, top, lane 1) and GST-alone (Fig. 1B, top, lane 3) incubated in TBS buffer showed no reactivity. The immunoblot was stripped and immunostained with anti-GST antibody to define the protein loading (Fig. 1B, bottom).

TABLE 1.

Identity of the αKAP-associated complex in cardiac microsomes

| Protein | Mass | Peptide match | Score | Expectation score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kDa | ||||

| SERCA2a | 110 | 19 | 693 | 4.1 × 10−7 |

| Aconitase 2 | 86 | 30 | 1181 | 1.0 × 10−7 |

| Hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase | 83 | 27 | 792 | 9.2 × 10−8 |

| Aralar | 74 | 17 | 669 | 3.1 × 10−8 |

| Acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase | 71 | 51 | 1088 | 4.2 × 10−8 |

| CaM kinase | 52 | 13 | 423 | 3.1 × 10−8 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 34 | 64 | 834 | 3.9 × 10−7 |

| αKAP | 23 | 12 | 392 | 1.1 × 10−7 |

The SERCA2a, αKAP, CaMKII, and CaM complex in SR

The CaMKII activity of the SR can be isolated on calmodulin affinity columns (20). We reasoned that if SERCA2a, αKAP, and CaMKII exist in a complex, these proteins would co-purify together on CaM-Sepharose. CaM-Sepharose 4B was incubated with detergent-solublized SR and CaM-binding proteins eluted with EGTA, resolved in SDS-PAGE, and silver-stained (20). CaM-Sepharose specifically binds to a multitude of polypeptides of different molecular mass (Fig. 1C, lane 2), and analysis with either MALDI-TOF or liquid chromatography-MS/MS revealed that the ∼450 kDa band was the ryanodine receptor, the 110 kDa band was SERCA2a, the 86 kDa band was 6-phosphofructose kinase, and the 23 kDa band was αKAP (Table 2). Further, immunoblotting of the EGTA-eluted proteins with a polyclonal anti-CaMKII antibody (Fig. 1D, bottom, lane 2) recognized ∼70-, 60-, 52-, 54-, and 23-kDa polypeptides, which we have previously shown to represent the CaMKIIβ4, CaMKIIβ, CaMKIIδ, and αKAP, respectively (13, 14, 20). The anti-SERCA2a antibody recognized a 110-kDa polypeptide (Fig. 1D, top, lane 2), further confirming the specific retention of the calcium ATPase on the CaM affinity column. Since both SERCA2a and αKAP lack calmodulin binding motifs (14, 16, 21), their retention on the CaM affinity column could only be due to an association with other CaM-binding proteins, such as CaMKII or the ryanodine receptor (20, 22). The Sepharose 4B exhibited some nonspecific binding of polypeptides (Fig. 1C, lane 1), but these appeared mostly distinct in terms of molecular mass from those retained specifically on the CaM-Sepharose 4B column and did not exhibit any cross-reactivity with anti-CaMKII or anti-SERCA2a antibodies (Fig. 1D, lane 1).

TABLE 2.

Identity of the calmodulin-associated complex in cardiac SR

| Protein | Mass | Peptide match | MOWSE Score | Expectation score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kDa | ||||

| MALDI-TOF analysis | ||||

| Ryanodine receptor | 450 | 34 | 2.6 × 107 | |

| SERCA2a | 110 | 9 | 7.3 × 104 | |

| Liquid chromatography-MS/MS analysis | ||||

| SERCA2a | 110 | 50 | 5.5 × 10−8 | |

| 6-Phosphofructose kinase | 86 | 30 | 0.1 × 10−7 | |

| αKAP | 23 | 49 | 1.7 × 10−8 | |

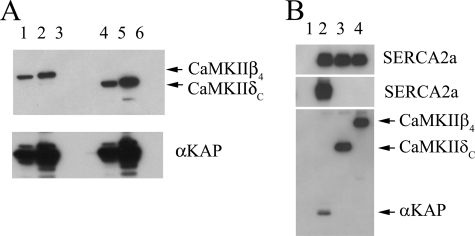

αKAP Is a Common Binding Partner of SERCA2a and CaMKIIβ4

We further studied the interaction of αKAP with SERCA2a and CaMKIIβ4 by transfection of expression constructs in mammalian cells. In a series of experiments, cDNA of mouse SERCA2a fused to GFP was co-expressed with six-Myc-tagged αKAP in HeLa cells, and IP was carried out on cell lysates with anti-Myc. Western blot analysis with anti-SERCA2a monoclonal antibody revealed that SERCA2a-GFP was detected in the IP reactions of cell lysates containing αKAP-Myc (Fig. 2A, middle, lane 1) and not in the reactions of cell lysates containing control pcDNA3-six-Myc vector (Fig. 2A, middle, lane 2). The top panel in the same figure shows staining with anti-SERCA2a antibody and confirms the relative level of expression of SERCA2a protein in test and control cell lysates (Fig. 2A, top, lanes 1 and 2). Similarly, the bottom panel in the figure shows staining with anti-Myc, which identified the presence of αKAP-Myc in cell lysates (Fig. 2A, bottom, lane 1). The control experiment consisting of pcDNA3-Myc alone (Fig. 2A, bottom, lane 2) does not show any protein band, because of the very small size of the six-Myc tag.

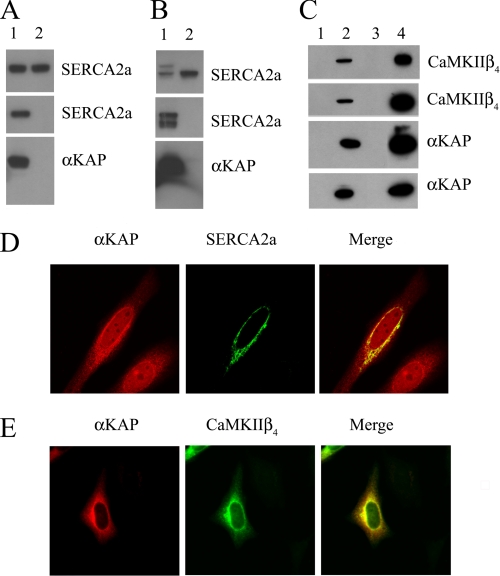

FIGURE 2.

αKAP binds SERCA2a and CaMKIIβ4. A, HeLa cells were transfected with SERCA2a-GFP and co-transfected with αKAP-Myc (lane 1) or pcDNA3-Myc vector (lane 2); an IP reaction was performed on cell lysates with anti-Myc; and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted. Top, cell lysate blotted with anti-SERCA2a; middle, IP with anti-Myc and blotted with anti-SERCA2a; bottom, cell lysate blotted with anti-Myc. B, the blots from A were stripped and reprobed with anti-GFP (top and middle) and anti-αKAP (bottom). C, HeLa cells co-transfected with CaMKIIβ4-GFP and either αKAP-Myc (lanes 2 and 4) or pcDNA3-Myc (lanes 1 and 3). The cell lysates (lanes 1 and 2) or proteins immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc (lanes 3 and 4) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-CaMKIIβ4, anti-GFP, anti-αKAP, and anti-Myc. D, HeLa cells co-transfected with αKAP-Myc and SERCA2a-GFP were immunostained with anti-Myc (red) and visualized with a confocal microscope. E, cells co-transfected with αKAP-Myc and CaMKIIβ4-GFP (green) were immunostained with anti-Myc (red) and examined with a confocal microscope. The merged image shows the co-localization (yellow).

The samples from the IP reactions noted above were also immunoblotted with anti-GFP monoclonal antibody (Fig. 2B), which identified the expression of SERCA2a protein and confirmed the data obtained with the anti-SERCA2a antibody. In these sets of experiments, SERCA2a-GFP was only detected in the IP reactions with αKAP-Myc (Fig. 2B, middle, lane 1) and not in control pcDNA3-Myc vector (Fig. 2B, middle, lane 2). The top panel in the figure shows the expression of SERCA2a-GFP in test (Fig. 2B, top, lane 1) and control (Fig. 2B, top, lane 2) cell lysates, as identified with anti-GFP staining. In the bottom panel, anti-CaMKIIα antibodies confirm the expression of αKAP in the cell lysates (Fig. 2B, bottom, lane 1). Notably, SERCA2a-GFP appeared as a doublet in this experiment. The presence of two protein bands for SERCA2a from expression constructs have been previously noted as well (23, 24).

We then examined the interactions between αKAP and CaMKII by co-transfection studies of HeLa cells with αKAP-Myc and CaMKIIβ4-GFP expression constructs. Cell lysates from mock (Fig. 2C, lane 1) and CaMKIIβ4-GFP plus αKAP-Myc-transfected (Fig. 2C, lane 2) cells were examined for the expression of these proteins. The IP reactions were carried out with anti-Myc antibodies and detected with anti-CaMKIIβ antibody. This showed the presence of CaMKIIβ4 in the immunoprecipitates of αKAP-transfected cell lysates only (Fig. 2C, top, lane 4) and not in mock-transfected cell lysates (Fig. 2C, top, lane 3). The IP reactions were also stained with anti-GFP antibodies, which confirmed the interaction between αKAP and CaMKIIβ4 (Fig. 2C, second panel, lane 4). The third and fourth panel in same figure show staining with anti-αKAP and anti-Myc antibodies, respectively, which identified an αKAP band in test lysates (Fig. 2C, lane 2) and in the IP reactions of test lysates (Fig. 2C, lane 4) but not in control lanes (Fig. 2C, lanes 1 and 3).

We further visualized any co-localization of αKAP with SERCA2a and CaMKIIβ4 by immunocytochemical staining of expressed proteins in HeLa cells as well as their endogenous distribution in primary cultures of cardiomyocytes. Confocal microscopy of HeLa cells transiently transfected with αKAP-Myc (red) and SERCA2a-GFP (green) shows that αKAP and SERCA2a appear on intracellular structures with a perinuclear staining, which is a characteristic feature of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane (Fig. 2D). Additionally, some αKAP staining also appeared on other intracellular structures. The SERCA2a staining appears to completely overlap with αKAP, although αKAP was also noted in additional locations. Immunocytochemical staining of cells transfected with αKAP-Myc and CaMKIIβ4-GFP showed a similar pattern of co-localization (Fig. 2E). Both αKAP-Myc (red) and CaMKIIβ4-GFP (green) staining were mostly concentrated in reticular structures around the nucleus, although the staining was also noted to spread through out the cell.

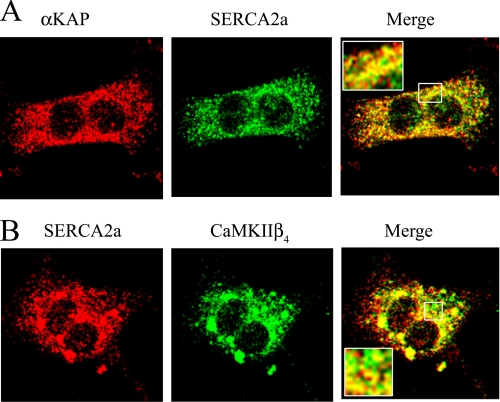

The subcellular localization of endogenous αKAP, SERCA2a, and CaMKIIβ4 was also examined in mouse cardiomyocytes with confocal imaging (Fig. 3). The cardiomyocytes appeared as binucleated cells with a typical rectangular shape, and immunostaining with anti-αKAP (red) and anti-SERCA2a (green) showed that these proteins are distributed in a punctuate fashion on reticular structures that most probably represent subcellular membranes in these cells. Although in a merged image, a significant overlap of the two signals (yellow) indicates colocalization, some regions with distinct distribution for αKAP (red) and SERCA2a were also evident (Fig. 3A). Immunostaining with anti-SERCA2a (red) and anti-CaMKIIβ4 (green) shows the presence of the two proteins on reticular structures throughout the cell and concentrated in the perinuclear region (Fig. 3B). A merge of the images indicates some co-localization of SERCA2a and CaMKIIβ4 in cardiomyocytes, but there are clear regions of distinct distribution for the two molecules as well.

FIGURE 3.

Confocal imaging of αKAP, SERCA2a and CaMKIIβ4 in cardiomyocytes. Isolated mouse cardiomyocytes were visualized with a confocal microscope and stained with anti-αKAP (red) and anti-SERCA2a (green) (A). The inset in the merged image shows an enlarged area to show more detail. B, anti-SERCA2a (red) and anti-CaMKIIβ4 (green). The inset in the merged image shows an enlarged section for greater detail. The data are typical of six experiments.

Distinct Regions in αKAP Interact with SERCA2a and CaMKIIβ4

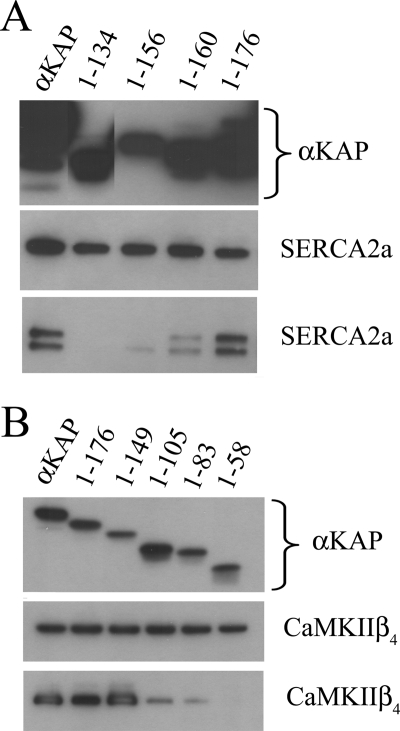

To assess any direct interactions between αKAP and SERCA2a or CaMKIIβ4, we made a series of deletion mutants of αKAP in pcDNA3-six-Myc (Fig. 4, A and B, top). Full-length αKAP, which encodes 200 amino acids, or its different deletion constructs were co-expressed with SERCA2a-GFP (Fig. 4A) or CaMKIIβ4-GFP (Fig. 4B). IP assays were performed on cell lysates with anti-Myc, and the precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blots using anti-GFP. The αKAP-Myc could immunoprecipitate either SERCA2a (Fig. 4A) or CaMKII (Fig. 4B), and this implies a direct association of the two proteins with αKAP. The minimal sequence of αKAP that is required for the interaction with SERCA2a resides in amino acids 1–156 (Fig. 4A, bottom), since binding with SERCA2a is restored with additional c-terminal sequences in αKAP. The middle panel in Fig. 4A shows the expression level of SERCA2a in the different transfected cell lysates.

FIGURE 4.

Distinct regions in αKAP bind SERCA2a and CaMKIIβ4. Deletion constructs of αKAP-Myc were co-transfected with SERCA2a-GFP in HeLa cells, and IP reactions were performed with anti-Myc. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted. A, top, cell lysate blotted with anti-Myc. Middle, cell lysates blotted with anti-GFP antibody. Bottom, proteins immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc and blotted with anti-GFP. B, HeLa cells were co-transfected with CaMKIIβ4-GFP and αKAP-Myc constructs or various deletions and IP reactions performed with anti-Myc. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted. Top, cell lysate blotted with anti-Myc; middle, cell lysate blotted with anti-GFP staining; bottom, proteins immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc and blotted with anti-GFP. The data are typical of three experiments.

The interaction of αKAP with CaMKIIβ4 is mediated by N-terminal sequences of αKAP as well (Fig. 4B). The mutant with amino acids 1–149 showed full interaction with CaMKIIβ4, but deleting additional amino acids substantially reduced the interaction between the two proteins, and the mutant with fewer than amino acids 1–83 did not interact with CaMKIIβ4 (Fig. 4B, bottom). The middle panel in Fig. 4B shows expression of CaMKIIβ4 in different deletion mutant cell lysates.

αKAP Interacts with CaMKIIδC and CaMKIIβ4

Since CaMKIIδ is the most studied CaMKII isoform in cardiac tissues, we sought to determine if αKAP can bind CaMKIIδ as well. We co-expressed full-length αKAP-six-Myc and either CaMKIIβ4-GFP or CaMKIIδC-GFP in HeLa cells. An IP reaction was performed with anti-Myc, and the analysis of the immunoprecipitated protein with anti-GFP showed that αKAP can interact with both CaMKIIβ4 (Fig. 5A, top, lane 2) and CaMKIIδC (Fig. 5A, top, lane 5). The control reaction involving mock-transfected cells did not show any polypeptide in those size ranges (Fig. 5A, top, lane 6). Lysates were also loaded on the gel to check the level of expressed proteins (5A, top) in cell lysates for CaMKIIβ4 (lane 1), CaMKIIδC (lane 4), and mock-transfected cells (lane 3).

FIGURE 5.

CaMKIIδC and CaMKIIβ4 bind αKAP but not SERCA2a. A, HeLa cells were transfected with αKAP-Myc and either CaMKIIδC-GFP (lanes 1 and 2) or CaMKIIβ4-GFP (lanes 4 and 5) or mock control (lanes 3 and 6). IP reactions were performed with anti-Myc, and protein composition was analyzed by Western blotting. Top, cell lysate blotted with anti-GFP. Bottom, proteins immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc and immunostained with anti-Myc. B, HeLa cells were transfected with SERCA2a-GFP (lanes 2–4) and either αKAP-Myc (lane 2) or CaMKIIδC-Myc (lane 3) or CaMKIIβC-Myc (lane 4) and mock-transfected control (lane 1). IP reactions were performed with anti-Myc and analyzed with immunoblotting. Top, total cell lysate blotted with anti-GFP. Middle, proteins immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc and blotted with anti-GFP. Bottom, proteins immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc and blotted with anti-Myc. The data are typical of three experiments.

The association domains of CaMKIIα and αKAP are identical and share a high degree of homology with other CaMKII isoforms. Since αKAP interacts with SERCA2a through a part of its association domain, we examined if other CaMKII isoforms can also directly interact with SERCA2a. HeLa cells were transfected with SERCA2a-GFP and co-transfected with either αKAP-Myc or CaMKII-Myc isoforms (δC or β4). IP assays on cell lysates were performed with anti-Myc antibody and subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed on Western blots with anti-GFP. Data revealed that only αKAP can immunoprecipitate SERCA2a (Fig. 5B, middle, lane 2), whereas CaMKIIδC (Fig. 5B, middle, lane 3), CaMKIIβ4 (Fig. 5B, middle, lane 4), or control reactions with mock-transfected cell lysates (Fig. 5B, middle, lane 1) were unable to do so. The bottom panel in the same figure shows the expression of αKAP (lane 2), CaMKIIδC (lane 3), and CaMKIIβc (lane 4) in different cell lysates. The top panel in the same figure shows expression of SERCA2a in different cell lysates used.

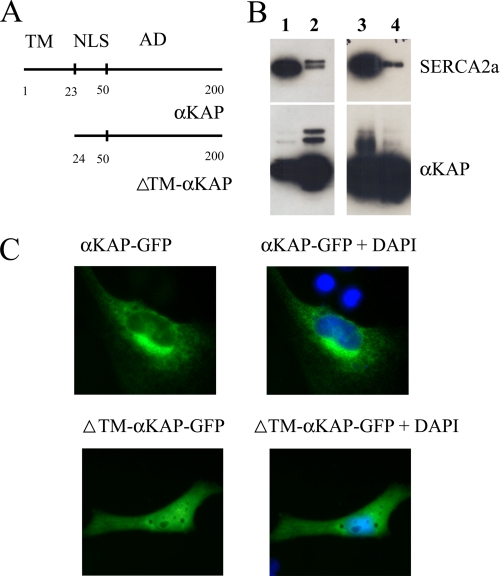

Transmembrane Domain in αKAP Is Critical for Membrane Targeting but Not SERCA2a Binding

αKAP is thought to consist of an N-terminal transmembrane (TM) domain, followed by a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and the association domain (AD) of CaMKIIα (Fig. 6A) (16). We examined the possible roles of the putative transmembrane domain to target αKAP to intracellular membranes and in the interaction with SERCA2a. A deletion mutant of αKAP that lacked the N-terminal 23 amino acids that are predicted to constitute the TM domain of αKAP (Fig. 6A) tagged with Myc (αKAPΔTM-Myc) and wild type αKAP-Myc were transfected into HeLa cells along with SERCA2a-GFP. IP assays were performed on the cell lysates with anti-Myc, and SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting with anti-GFP, revealed that the αKAPΔTM has no significant effect on its SERCA2a binding ability (Fig. 6B, lane 4) compared with the ability of wild type αKAP to bind SERCA2a (lane 2). Fig. 6B also shows the expression of SERCA2a-GFP and wild type αKAP-Myc (lane 1) and SERCA2a-GFP and αKAPΔTM-Myc (lane 3) in cell lysates.

FIGURE 6.

Transmembrane domain in αKAP targets membranes but not SERCA2a binding. A, αKAP comprises 200 amino acids, where the N-terminal 23 amino acids are thought to constitute a TM domain and amino acids 23–50 are thought to constitute the nuclear localization signal (NLS), followed by the association domain (AD). A deletion mutant (αKAPΔTM) lacking the putative transmembrane domain was constructed and tagged with the six-Myc epitope. B, HeLa cells were co-transfected with SERCA2a-GFP and either six-Myc-tagged αKAP or αKAPΔTM. IP reactions were performed with anti-Myc (lanes 2 and 4) and analyzed in Western blots. The top panel shows an immunoblot with anti-GFP antibody of cell lysates co-transfected with αKAP (lane 1) or αKAPΔTM (lane 3); it also shows immunoprecipitated proteins from lysates co-expressing SERCA2a with either αKAP (lane 2) or αKAPΔTM (lane 4). The bottom panel shows staining with anti-Myc antibody and identifies αKAP (lane 1) and αKAPΔTM (lane 3) in input lysates and immunoprecipitates of these cell lysates (lane 2) and αKAPΔTM (lane 4). C, αKAP was also fused to GFP, and HeLa cells transfected with either αKAP-GFP (top) or αKAPΔTM-GFP (bottom) were visualized under a confocal microscope. The nucleus is identified with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (blue). The data are typical of three experiments.

In a series of experiments to study targeting, αKAP was fused to GFP, and cells transfected with αKAP-GFP and αKAPΔTM-GFP were visualized by confocal microscopy. Cells transfected with αKAP-GFP showed reticular membranous type association, as evident from the punctate appearance without any nuclear localization (Fig. 6C, top panels). On the other hand, the deletion mutant αKAPΔTM-GFP exhibited a smooth non-reticular appearance throughout the cell, including localization in the nuclei that were identified with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue) staining (Fig. 6C, bottom panels).

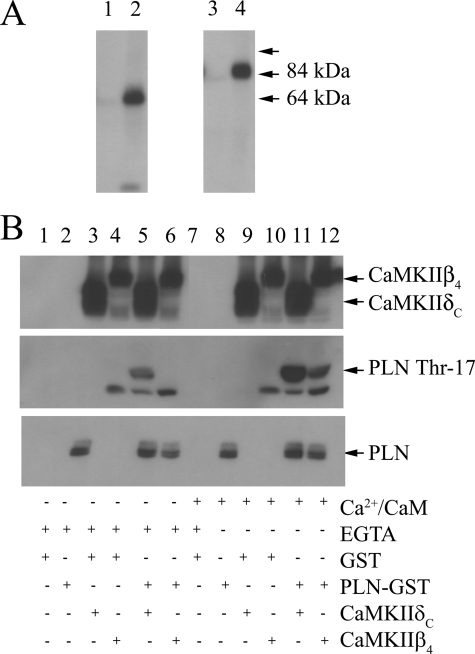

CaMKIIβ4 Phosphorylates Phospholamban

It is apparent from the findings described above that CaMKIIβ4 is a novel cardiac isoform of CAMKII that is targeted to the SR and SERCA2a through αKAP. We sought to determine the ability of CaMKIIβ4 to phosphorylate phospholamban, which is a known regulator of SERCA2a activity and muscle relaxation (18, 25–28). The ability of CaMKII (δC or β4) to phosphorylate SERCA2a or its subunit phospholamban was examined in HeLa cells that were co-transfected with SERCA2a-GFP, αKAP-Myc, and CaMKII-Myc isoforms (δC or β4). IP assays were performed with anti-Myc, and the precipitated proteins were subjected to calcium/CaM-dependent phosphorylation, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The phosphoproteins were separated in SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography, which showed the presence of autophosphorylated polypeptides of ∼64 kDa (CaMKIIδC-Myc) and ∼84 kDa (CaMKIIβ4-Myc) when phosphorylation assays were conducted in the presence of Ca2+/CaM (Fig. 7A, lanes 2 and 4) but not when phosphorylation was carried out in 5 mm EGTA in the absence of Ca2+/CaM (Fig. 7A, lanes 1 and 3). It is notable that no phosphorylation of the SERCA2a-GFP (∼140-kDa polypeptide), which was co-expressed in these cells, was detected due to CaMKIIδC or CaMKIIβ4 activity under these conditions.

FIGURE 7.

Both CaMKIIδC and CaMKIIβ4 phosphorylate phospholamban. A, HeLa cells were co-transfected with SERCA2a-GFP, αKAP-Myc, and either CaMKIIδC-Myc or CaMKIIβ4-Myc. IP reactions were performed on lysates, and precipitated proteins were subjected to phosphorylation with [γ-32P]ATP in the presence of either EGTA or Ca2+/CaM and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The radiograph shows autophosphorylation of CaMKIIδC in the presence of EGTA (lane 1) or Ca2+/CaM (lane 2) and autophosphorylation of CaMKIIβ4 in the presence of EGTA (lane 3) or Ca2+/CaM (lane 4). An arrow indicates the position of the ∼140 kDa band of SERCA2a, which is not phosphorylated. B, GST-purified CaMKIIδC, CaMKIIβ4, and PLN and GST (control) were incubated in a phosphorylation assay with EGTA or Ca2+/CaM (see “Experimental Procedures”). Phosphoproteins were analyzed with anti-PLN phospho-Thr-17 antibody. Top, immunostaining with anti-CaMKII antibody of CaMKIIδC (lanes 3, 5, 9, and 11) and CaMKIIβ4 (lanes 4, 6, 10, and 12). Middle, immunoblotting with anti-PLN phospho-Thr-17 antibody. The antibody shows some phosphorylation activity in the presence of EGTA with CaMKIIδC (lane 5) but not with CaMKIIβ4 (lane 6). Bottom, immunoblotting with anti-PLN. Various buffer controls were also analyzed for any immunoreactivity (lanes 1, 2, 7, and 8). The data are typical of four experiments.

The CaMKIIδC is known to phosphorylate Thr-17 on phospholamban and stimulate SERCA2a (18). We examined whether CaMKIIβ4 can also serve to phosphorylate phospholamban by co-expressing PLN together with CaMKIIδC or CaMKIIβ4 as GST fusion proteins and assaying for the Ca2+/CaM-dependent phosphorylation of PLN as described above. Western blot analysis of phosphorylated proteins with anti-PLN phospho-Thr-17 revealed that both CaMKIIδC and CaMKIIβ4 are able to stimulate phosphorylation of PLN in a Ca2+/CaM-dependent manner (Fig. 7B, middle, lanes 11 and 12, respectively) compared with the EGTA control containing CaMKIIδC (Fig. 7B, middle, lane 5) and CaMKIIβ4 (Fig. 7B, middle, lane 6). Phosphorylation of PLN by CaMKIIδC in the presence of EGTA (lane 5) may be due to the high level of expression of this fusion protein. A lower molecular size band was also evident and most likely represents a nonspecific reactivity of anti-PLN-phospho-Thr-17, since it was present in the GST control (lanes 4 and 10) as well. The immunoblot was stripped and stained with a PLN antibody to identify total PLN in the reactions (Fig. 7B, bottom). The top panel shows the immunoblot with anti-CaMKII to define the expression level of CaMKIIδC and CaMKIIβ4. Buffer controls for any potential background or nonspecific immunostaining with various antibodies are also shown (lanes 1, 2, 7, and 8).

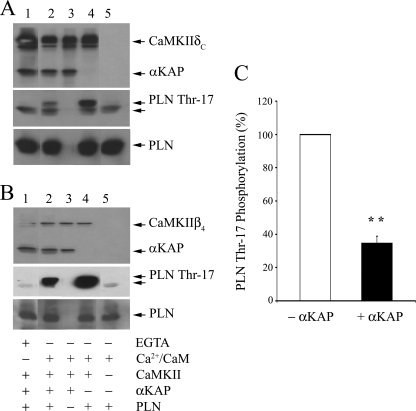

αKAP Modulates Phospholamban Phosphorylation

In order to assess whether αKAP can modulate PLN phosphorylation, PLN, CaMKIIδC, and CaMKIIβ4 were expressed as GST fusion proteins and subjected to phosphorylation in the presence and absence of purified αKAP. Western blot analysis of phosphoproteins with anti-PLN phospho-Thr-17 was used to determine any effects on phospholamban phosphorylation. Fig. 8 shows purified CaMKIIδC, PLN, and αKAP incubated in a phosphorylation assay with EGTA (lane 1) or Ca2+/CaM (lanes 2–4). The top panel (Fig. 8A) shows the expression of CaMKIIδC (lanes 1–4), as assessed by immunoblotting with anti- CaMKIIδC, and αKAP expression (lanes 1–3), as assessed by immunoblotting with anti-αKAP. The middle panel (Fig. 8A) shows immunoblotting with anti-PLN phospho-Thr-17, and the bottom panel (Fig. 8A) shows the immunoblot with anti-PLN for loading control. Ca2+/CaM clearly activated CaMKIIδC to stimulate phosphorylation of PLN (lane 4) compared with that in the presence of EGTA (lane 1). However, Ca2+/CaM-dependent PLN phosphorylation (lane 4) was markedly inhibited by the presence of αKAP (lane 2). The bottom panel (Fig. 8B) shows the expression of CaMKIIβ4 (lanes 1–4), as assessed by immunoblotting with anti-CaMKIIβ, and αKAP expression (lanes 1–3), as assessed by immunoblotting with anti-αKAP. The middle panel (Fig. 8B) shows immunoblotting with anti-PLN phospho-Thr-17, and the bottom panel (Fig. 8B) shows the immunoblot with anti-PLN. Ca2+/CaM clearly activated CaMKIIβ4 to stimulate phosphorylation of PLN (lane 4) compared with EGTA control (lane 1). The Ca2+/CaM phosphorylation of PLN was markedly inhibited by the presence of αKAP (lane 2). Although the anti-phospho-PLN antibody recognized phosphorylated PLN, it also reacted nonspecifically with a polypeptide of smaller molecular mass (arrow) in the PLN control (lane 5). Quantification using densitometry of the phosphoprotein bands detected by anti-phospho-Thr-17 antibody showed that in the presence of αKAP there was a 65.37 ± 4.18% reduction in the phosphorylation of PLN due to CaMKII activity (bar graph).

FIGURE 8.

αKAP modulates the phosphorylation of phospholamban. GST-purified CaMKIIδC (A) or GST-purified CaMKIIβ4 (B) together with PLN and αKAP were incubated in a phosphorylation assay with EGTA (lane 1) or Ca2+/CaM (lanes 2–4). Phosphoproteins were analyzed with anti-PLN phospho-Thr-17. A, top, immunostaining of CaMKIIδC (lanes 1–5) and αKAP (lanes 1–4) with anti-CaMKII/anti-αKAP. Middle, immunoblotting with anti-phospho-PLN antibody. Lane 2 shows PLN phosphorylation in the presence of αKAP compared with lane 4 (without αKAP). The anti-PLN phospho-Thr-17 antibody reacts with PLN as well as nonspecifically with a polypeptide of smaller molecular mass (arrow). Bottom, immunoblot with anti-PLN. B, top, immunoblotting of CaMKIIβ4 (lanes 1–5) and αKAP (lanes 1–5) with anti-CaMKII/anti-αKAP. Middle, immunoblotting with anti-PLN phospho-Thr-17 antibody identified the phosphorylated PLN as well as reacted nonspecifically with a polypeptide of smaller molecular mass (arrow) as seen in the PBL control (lane 5); bottom, immunoblot with anti-PLN for total PLN protein. The data are representative of five different experiments. C, inhibitory effect of αKAP (+αKAP) on PLN phospho-Thr-17 phosphorylation due to Ca2+/CaM-dependent CaMKII activity was quantified by densitometry and is shown as percentage of phosphorylation of that in the absence (−αKAP) of any αKAP (control). Values presented are mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. The asterisks denote statistical significance with respect to control; **, p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The data here show that αKAP can exist in a complex with CaMKII isoforms, SERCA2a, and CaM at the cardiac SR. αKAP directly binds SERCA2a as well as recruits CaMKIIδC and CaMKIIβ4 isoforms, which are prominent in cardiac tissue. Furthermore, αKAP can modulate PLN phosphorylation at Thr-17, which is known to regulate SERCA2a activity and SR function (18, 25–28). SERCA2a binds directly to regions in the association domain of αKAP that are distinct from those that associate with CaMKII. Although the removal of the putative transmembrane domain of αKAP disengaged it from the SR membrane, as reported (15, 30), it did not effect its interaction with SERCA2a or CAMKII, since the association domain of αKAP containing the binding sites is extramembranous. Further more, the CaMKII isoforms did not exhibit direct interactions with SERCA2a, indicating a central role for the αKAP interactions in positioning these enzymes at the SR membrane.

The CaMKIIδC and CaMKIIβ4 were both effective in phosphorylating PLN on Thr-17, and the presence of αKAP was found to down-regulate this phosphorylation event. The phosphorylation of PLN on Thr-17 due to CaMKIIδC or at Ser-16 by protein kinase A has been positively correlated with an increase in SERCA2a activity, calcium uptake, and the rate of cardiac muscle relaxation (25–28). The ability of CaMKIIβ4 isoform to exist in a complex with αKAP and SERCA2a and phosphorylate Thr-17 on PLN suggests that this kinase would serve a physiological role in cardiac muscle function as well. In this regard, recent studies indicate that mice that lack CaMKIIδC in the myocardium exhibit normal physiological function and pathological response to pressure overload (29). In view of our data on the expression and targeting of CaMKIIβ4 activity to cardiac SR, we suggest that this CaMKII isoform could substitute for CaMKIIδC and potentially contribute to normal cardiac biology and the acute response to stress in the CaMKIIδC null mice (29). Further, CaMKIIβ4 can bind glycolytic enzymes and regulate glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase at the SR and has been implicated in the control of local ATP production to support calcium uptake (13, 14). Thus, the data here on CaMKIIβ4 and its associations at the SR membrane suggest an important and underappreciated role for this CaMKII isoform in cardiac function. It is noted that the CaMKIIδC isoform has been studied in detail, and its involvement in excitation-contraction coupling, cardiac growth, and dysfunction has been clearly implicated (28). Although our data show that αKAP can target both CaMKIIδC and CaMKIIβ4 isoforms to the SR to modulate PLN phosphorylation, it is apparent that neither of these bind directly to SERCA2a; nor was SERCA2a a substrate of these protein kinases. Thus, the direct association of αKAP with SERCA2a described here may be critical for positioning CaMKII activity for the modulation of calcium uptake via phosphorylation of PLN.

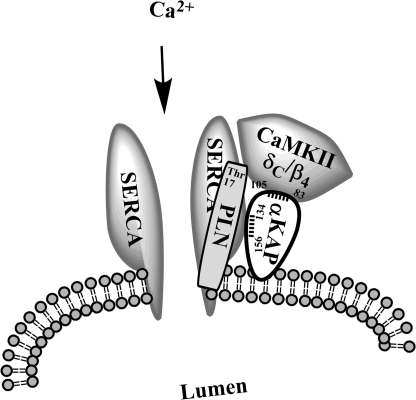

Collectively, these findings position αKAP as a membrane protein that interacts with SERCA2a on the one hand and CaMKII on the other. In this sense, αKAP acts as a scaffold and an adaptor to promote the spatial positioning of these proteins to facilitate the modulation of SERCA2a function through PLN phosphorylation by CaMKII activity at the SR. Based upon these observations, we propose a model of a CaMKII-αKAP-SERCA2a-PLN complex at the SR membrane, which will convey calcium and CaM sensitivity to the calcium transport mechanism in a localized and temporal manner (Fig. 9). Thus, when the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration rises due to calcium release from the SR, it would bind CaM and activate anchored CaMKII activity to phosphorylate PLN and relieve the inhibition on SERCA2a and stimulate calcium sequestration into the SR and muscle relaxation (25–28). Additionally, αKAP can itself modulate the level of PLN phosphorylation on Thr-17 and further fine tune SR function (Fig. 9). Although αKAP has been shown to assemble with and support α-CaMKII activity (15), how it can modulate CaMKIIδC and CaMKIIβ4 and the level of PLN phosphorylation on Thr-17 at the SR membrane remains to be defined.

FIGURE 9.

Modeling the assembly of αKAP with SERCA2a, PLN and CaMKII at the cardiac SR. αKAP is targeted to the SR membrane via its N-terminal transmembrane domain and directly interacts with SERCA2a as well as CaMKIIδC or -β4 isoforms. In addition, αKAP can modulate the Ca2+/CaM dependent phosphorylation of PLN at threonine 17, which is known to regulate calcium uptake into the SR and muscle relaxation in response to calcium signals. Thus, αKAP serves a dual role of targeting and modulating the calcium transport process.

It is notable that AKAP is critical for the spatial and temporal control of cAMP signaling, and a large repertoire of AKAPs have been described that function as scaffolds for targeting cAMP signaling enzymes to distinct subcellular sites (3, 4). Cardiac and skeletal muscle tissue have been reported to express many distinct AKAPs, some of which are critical in the anchoring of protein kinase A to the effectors, such as the ryanodine receptor (31), L-type calcium channel (32), or PLN (33) and regulate contraction and relaxation (34, 35). We noted that αKAP can associate with membrane proteins of the mitochondria and peroxisomes in myocardium, and confocal imaging demonstrated that αKAP exhibits distinct subcellular locations within the cardiomyocyte. αKAP may therefore be a part of different intracellular membrane complexes that tether unique CaMKII isoforms to effectors to influence a variety of cellular events and support the multifunctional nature of CaMKII activity (2). Given the diverse emerging role of the AKAPs in cAMP signaling cascades (36), it is conceivable that αKAP may provide an analogous scaffold/adaptor for the spatial and temporal control of Ca2+ signaling at distinct subcellular locations. In this regard, the calcium release channel is also a substrate for CaMKII (29), and the potential role of αKAP in its targeting and regulation is also under investigation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. J. Byers and M. Nader for constructive discussions and input.

This work was supported by Canadian Institute of Health Research Grant 9596 (to B. S. T.).

- AKAP

- protein kinase A anchoring protein

- αKAP

- α kinase anchoring protein

- CaM

- calmodulin

- CaMKII

- calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- MALDI-TOF

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight

- PLN

- phospholamban

- SERCA2a

- sarco-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2a

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- TBS

- Tris-buffered saline

- CHAPS

- 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid

- MOPS

- 4- morpholinepropanesulfonic acid

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- TM

- transmembrane.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alto N., Carlisle Michel J. J., Dodge K. L., Langeberg L. K., Scott J. D. (2002) Diabetes 51, S385–S388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudmon A., Schulman H. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 473–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McConnachie G., Langeberg L. K., Scott J. D. (2006) Trends Mol. Med. 12, 317–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith F. D., Langeberg L. K., Scott J. D. (2006) Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 316–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitt G. S. (2007) Cardiovasc. Res. 73, 641–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wayman G. A., Lee Y. S., Tokumitsu H., Silva A., Soderling T. R. (2008) Neuron 59, 914–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang T., Kohlhaas M., Backs J., Mishra S., Phillips W., Dybkova N., Chang S., Ling H., Bers D. M., Maier L. S., Olson E. N., Brown J. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 35078–35087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahl C. R., Means A. R. (2003) Endocr. Rev. 24, 719–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamaguchi N., Meissner G. (2007) Circ. Res. 100, 293–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stange M., Xu L., Balshaw D., Yamaguchi N., Meissner G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51693–51702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacLennan D. H., Campbell K. P., Takisawa H., Tuana B. S. (1984) Adv. Cyclic Nucleotide Protein Phosphorylation Res. 17, 393–401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srinivasan M., Edman C. F., Schulman H. (1994) J. Cell Biol. 126, 839–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh P., Salih M., Leddy J. J., Tuana B. S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35176–35182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh P., Leddy J. J., Chatzis G. J., Salih M., Tuana B. S. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 270, 215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bayer K. U., Harbers K., Schulman H. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 5598–5605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayer K. U., Löhler J., Harbers K. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 29–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolb S. J., Hudmon A., Ginsberg T. R., Waxham M. N. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31555–31564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattiazzi A., Mundiña-Weilenmann C., Guoxiang C., Vittone L., Kranias E. (2005) Cardiovasc. Res. 68, 366–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bkaily G., Pothier P., D'Orléans-Juste P., Simaan M., Jacques D., Jaalouk D., Belzile F., Hassan G., Boutin C., Haddad G., Neugebauer W. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 172, 171–194 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuana B. S., MacLennan D. H. (1988) FEBS Lett. 235, 219–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandl C. J., Green N. M., Korczak B., MacLennan D. H. (1986) Cell 44, 597–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi N., Takahashi N., Xu L., Smithies O., Meissner G. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1344–1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim Y. K., Kim S. J., Yatani A., Huang Y., Castelli G., Vatner D. E., Liu J., Zhang Q., Diaz G., Zieba R., Thaisz J., Drusco A., Croce C., Sadoshima J., Condorelli G., Vatner S. F. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47622–47628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennedy D. J., Vetteth S., Xie M., Periyasamy S. M., Xie Z., Han C, Basrur V., Mutgi K., Fedorov V., Malhotra D., Shapiro J. I. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 291, H3003–H3011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacLennan D. H., Kranias E. G. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 566–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wegener A. D., Simmerman H. K., Lindemann J. P., Jones L. R. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 11468–11474 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Z., Akin B. L., Jones L. R. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20968–20976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maier L. S., Zhang T., Chen L., DeSantiago J., Brown J. H., Bers D. M. (2003) Circ. Res. 92, 904–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ling H., Zhang T., Pereira L., Means C. K., Cheng H., Gu Y., Dalton N. D., Peterson K. L., Chen J., Bers D., Heller Brown J. (2009) J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1230–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nori A., Lin P. J., Cassetti A., Villa A., Bayer K. U., Volpe P. (2003) Biochem. J. 370, 873–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kapiloff M. S., Jackson N., Airhart N. (2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 3167–3176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hulme J. T., Lin T. W., Westenbroek R. E., Scheuer T., Catterall W. A. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 13093–13098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lygren B., Carlson C. R., Santamaria K., Lissandron V., McSorley T., Litzenberg J., Lorenz D., Wiesner B., Rosenthal W., Zaccolo M., Taskén K., Klussmann E. (2007) EMBO Rep. 8, 1061–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Catterall W. A., Hulme J. T., Jiang X., Few W. P. (2006) J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 26, 577–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manni S., Mauban J. H., Ward C. W., Bond M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24145–24154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoshi N., Langeberg L. K., Scott J. D. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 1066–1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]