Abstract

Summary: The CRISPR genomic structures (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) form a family of repeats that is largely present in archaea and frequent in bacteria. On the basis of a formal model of CRISPR using very few parameters, a systematic study of all their occurrences in all available genomes of Archaea and Bacteria has been carried out. This has resulted in a relational database, CRISPI, which also includes a complete repertory of associated CRISPR-associated genes (CAS). A user-friendly web interface with many graphical tools and functions allows users to extract results, find CRISPR in personal sequences or calculate sequence similarity with spacers.

Availability: CRISPI free access at http://crispi.genouest.org

Contact: croussea@irisa.fr; jnicolas@irisa.fr;

1 INTRODUCTION

A notable regular structure made up of a skeleton of repeats alternating with a set of highly variable short sequences has been recognized on numerous occasions in prokaryotic genomes under different names in the literature (TREP, SPIDR, SRSR, etc.), and since 2002 has come to be known as CRISPR Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; Barrangou et al., 2007; Sorek et al., 2008). The structure generally contains 4–10 direct repeats ranging in size from 25 to 45 nt, separated by spacers of similar length containing specific genomic material that is not present elsewhere in the genome and that has probably been imported from plasmids or viruses. CRISPR are present in all but six archaeal species and half of bacteria. Since they are expected to play an important role in prokaryotic adaptive immunity and may serve as specific markers, it is highly desirable to have dedicated identification tools and regularly updated databases available. Several computational methods have been developed to predict CRISPR using a more or less explicit model introducing many parameters filtering the permitted number of elements, sizes and distances between elements of the structure, mismatches between units (Bland et al., 2007; Edgar, 2007; Grissa et al., 2007b), etc. One of the most complete source of data on CRISPR was designed in 2007 by Grissa et al. (2007a) and most recently released in June 2009. We have tried to improve on this, with a simpler CRISPR model and several new functions.

2 IMPLEMENTATION

2.1 Identification of CRISPR

The usual specification of CRISPR, based on limited empirical data instead of biological functional constraints, remains too informal to be helpful in systematic studies: CRISPR are repeated structures composed of exact repeat sequences 24–48 bases long separated by unique spacers of similar length (Kunin et al., 2007).

In actual fact, most CRISPR include altered repeats and spacers are occasionally repeated inside the same structure and sometimes even in different CRISPR on the same chromosome. Some authors give more details on the structure: repeats were thought to exhibit a kind of dyadic symmetry, but as more data becomes available this characterization is being questioned. A leader sequence before the train of repeats is often mentioned, but it is only defined as an A/T rich region and does not appear to be present in all CRISPR. Since the existence of a skeleton seems the only tangible indicator for CRISPR and since we try to minimize a priori assumptions, we have chosen to base the search only on the existence of a periodic spaced suite of units (at least four units) that is not a tandem repeat. Maximal repeats have largely been used for the detection of relevant repeats and applied to the search for units (Grissa et al., 2007b). But short words such as those that appear in CRISPR can occur at a frequency comparable with random words of similar size. We have introduced locality restrictions on the notion of maximal repeats reflecting the kind of repeats that are found in CRISPR: first, each cluster of occurrences has a limited size; second, only maximal repeats with at least one occurrence that is not covered by a larger repeat are retained (Nicolas et al., 2008). We have produced putative units by clustering such overlapping local maximal repeats. Actually, we do not fix any value for the size of units or spacers, and we do not require units to be identical inside a given CRISPR (the minimal required percentage of identity with the consensus is, however, fixed at 60% in order to avoid spurious structures).

Bacterial and archaeal genomes have been downloaded from the NCBI FTP Server (ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/Bacteria/). The detection method we have just outlined has been implemented in C and Java 1.5.0 12. The presence of CRISPR has been checked in all available genomes and results have been stored into a MySQL 4.1.12 database. All web pages are implemented using PHP 4.3.9.

2.2 Access to the CRISPI database

The main page of CRISPI offers three search forms that give access to the database content or allow to analyse personal sequences.

2.2.1 Database searches

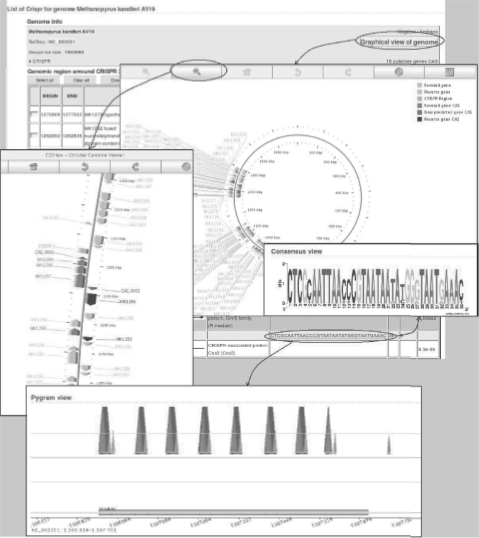

CRISPI allows users to view all CRISPR found in Archaea and Bacteria genomes. Microbial genomes can be easily selected by accession number, by entering the genome name (or a part of it) or by selecting a genome from the genome list (alphabetical order) or in the taxonomy browser. Once a genome has been selected, results are summarized in tables. Each CRISPR is highlighted and CRISPR-associated genes (CAS genes) found in its vicinity are displayed. These are identified by dedicated Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profiles that have been constructed from available genes. If new putative CAS genes were found, they are highlighted in red. Annotations contain various elements such as positions, sequence of the consensus unit, links to related NCBI information, links to graphical circular views of the genome [thanks to CGView, see (Stothard and Wishart, 2005)]. Clicking on the consensus takes the user to the CRISPR's details and gives information such as units and spacer coordinates, units and spacer sequences, Pygram image (Durand et al., 2006) and consensus WebLogo image (Fig. 1). Spacers, Units, CRISPR, flanking sequences and CAS genes may be downloaded in Fasta format.

Fig. 1.

Typical graphical views in CRISPI.

2.2.2 Run BLAST on user-provided sequence against CRISPI

Virologists or microbiologists can run BLAST on user-provided sequences to find out if a virus or plasmid sequence matches with one or more spacers in the database. The query sequence must be in Fasta format (DNA or protein). The query sequence can either be pasted into the input field or uploaded from a file on the local machine (files with multiple sequences are allowed). Users have access to BLAST parameters for precise comparisons. Moreover, it can be run against units instead of spacers for studies on the origin of such structures. The BLAST results pages are cross-linked with the CRISPI database so that it is easy to return to the database by clicking on hyperlinks.

2.2.3 Identify CRISPR repeats in user-provided sequence

Users may wish to check their own microbial sequences for annotation purposes. The query sequence must be in Fasta format (only DNA sequences are allowed). The query sequence can either be pasted into the input field or uploaded from a file on the local machine (files with multiple sequences are not allowed). Results are summarized in a table, and users have the option of requesting an email notification once the results are available. These user-submitted genomes remain available on confidential web pages that can be accessed for 10 days before deletion.

3 CONCLUSIONS

CRISPI is a dedicated environment on CRISPR in prokaryotic genomes that offers for the first time an up-to-date view of existing CRISPR (71 archaea totalling 291 CRISPR, and 987 bacteria totalling 2103 CRISPR) including a complete repertory of CRISPR-associated genes CASgenes. The current version contains 1173 archeal CAS genes and 4396 bacterial CAS genes. We have not attempted to retain very small structures (1 or 2 spacers), as in Grissa et al. (2007a), as it is not clear if they have any relevance or activity. In contrast, we have included a richer environment for practical work on CRISPR: access to extended queries via BLAST parameters, multiple graphical views, etc.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The necessary environment for all computations has been provided by the bioinformatics platform Biogenouest (http://biogenouest.org)

Funding: ANR (Agence Nationale de la Recherche) through its MODULOME project.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Barrangou R, et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science. 2007;315:1709–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1138140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland C, et al. CRISPR recognition tool (CRT): a tool for automatic detection of clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:209. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand P, et al. Browsing repeats in genomes: Pygram and an application to non-coding region analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:477. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. Piler-cr: fast and accurate identification of crispr repeats. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissa I, et al. The crisprdb database and tools to display crisprs and to generate dictionaries of spacers and repeats. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007a;8:172. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissa I, et al. CRISPRfinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007b;35:W52–W57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin V, et al. Evolutionary conservation of sequence and secondary structures in crispr repeats. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R61. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas J, et al. Research report 6802. France, HAL - CCSD: INRIA Rennes; 2008. Modeling local repeats on genomic sequences. [Google Scholar]

- Sorek R, et al. CRISPR - a widespread system that provides acquired resistance against phages in bacteria and archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:181–186. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard P, Wishart DS. Circular genome visualization and exploration using cgview. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:537–539. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]